David Pilling's Blog, page 16

October 21, 2021

People in strange clothes

In 1275 the first Statute of Westminster was passed into law in England. It was drafted by a team of professional legists, headed by Robert Burnell, and then discussed and approved by the king and royal council.

In 1275 the first Statute of Westminster was passed into law in England. It was drafted by a team of professional legists, headed by Robert Burnell, and then discussed and approved by the king and royal council.The statute consists of 51 clauses or chapters. Some were only repealed in the 19th century, while at least one is still in force in the UK. This is the Freedom of Elections Act (repealed in Ireland under the Electoral Act of 1963). The text in the original medieval statute, written in Norman-French, translates simply as:

“There shall be no disturbance of Free Elections. Elections shall be free. AND because Elections ought to be free, the King Commands upon Great Forfeiture, that no man by Force of Arms, Nor by Malice, Or Menacing, shall disturb any to make Free Election.”

The context of the statute was the accession of Edward I, and his need to strengthen the power of the crown after a decade of intermittent civil war. To that end the statutes were calculated to increase his popularity among the commons. They may have also, to an extent, reflected his personal convictions. In a private letter to his bailiff of Chester in 1260, Edward remarked:

“If common justice is denied to any one of our subjects by our bailiffs, we lose the favour of God and man, and our lordship is belittled.”

The king's motives don't matter, any more than Simon de Montfort's motive for summoning representatives to parliament in 1265. What matters is the long-term effect of legislation, whether or not it derived from the selfish policy of medieval warlords. The Freedom of Elections Act is one of the bedrocks of modern democracy, and still quoted in current arguments over the nature of law and government all over the world.

For instance, during a legal case in Australia in 1926, an elector challenged compulsory voting in State elections on the grounds that voting should be a voluntary act. This argument was rejected by the court, on the grounds that:

“A method of choosing which involves compulsory voting, so long as it preserves freedom of choice of possible candidates, does not offend against the freedom of elections, as established and recognised by the Statute of Westminster the First 1275 (3 Edward I), UK.”

And so on, and so forth. I noticed a comment the other day that the study of medieval history is essentially pointless; silly, indulgent chat about irrelevant dead people in strange clothes, and we should really be arguing about contemporary issues. No – he says, getting on his pulpit - the legacy of the Middle Ages is not dead. It is all around us; it is the fabric we stand on.

In short: vote for me, for a better tomorrow. And I'll have a large salary and grace and favour mansion to go with that, please.

Published on October 21, 2021 03:38

October 19, 2021

Try, try and try again

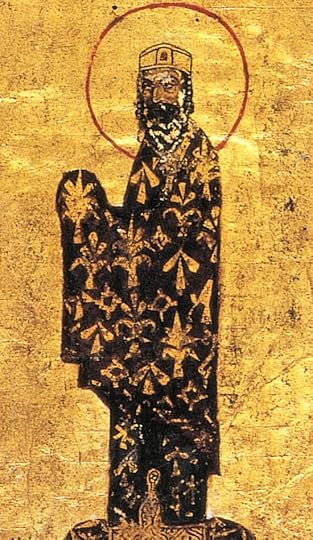

Yesterday – my usual pinpoint timing – was the anniversary of the battle of Dyrrhachium in 1081, where the Romans under Alexios I were defeated by Robert Guiscard's Normans. The battle swung on the massacre of the Varangian Guard, mainly composed of English exiles.

Yesterday – my usual pinpoint timing – was the anniversary of the battle of Dyrrhachium in 1081, where the Romans under Alexios I were defeated by Robert Guiscard's Normans. The battle swung on the massacre of the Varangian Guard, mainly composed of English exiles.Much of our information on the battle comes from the pen of Anna Comnemna, Alexios's daughter. There is a suspicion that she hung the English out to dry, and blamed them for the defeat to excuse her father's failure. According to Anna, the Guard rushed forward too eagerly to get at the Normans – perhaps to avenge Hastings – and ended up isolated:

“Meanwhile the axe-bearing barbarians and their leader Nabites had in their ignorance and in their ardour of battle advanced too quickly and were now a long way from the Roman lines...”

Tired out, the Guard were surrounded and massacred by Norman cavalry. The survivors fled to take refuge in a nearby chapel, but the Normans set it on fire and burnt them alive. Some must have survived; their leader, Nabites, turned up later fighting the Pechenegs. Nabites is not an Anglo-Saxon or Greek name, though he might have been Scandinavian. One suggestion is that it is formed from a nickname such as 'Near-Biter'.

Guiscard then unleashed his knights on the rest of the Roman army. It seems Alexios was ignorant of the sheer power of the Norman charge, which smashed his divisions all to pieces. Anna describes him fighting 'like an impregnable tower', but admits he was forced to run away. She puts a gloss on this by claiming he ran away like a hero, cutting down any Norman who got in his way.

In reality the emperor had suffered a terrible beating. But, much like Robert de Bruce and his pet spider, Alexios would try, try, try again. Almost twenty years later he got his revenge when Guiscard's son, Bohemund, came to attack Dyrrhachium with another horde of Normans. This time Alexios avoided battle and blockaded the invaders until plague and famine forced them to submit.

.

Published on October 19, 2021 07:46

King's knight

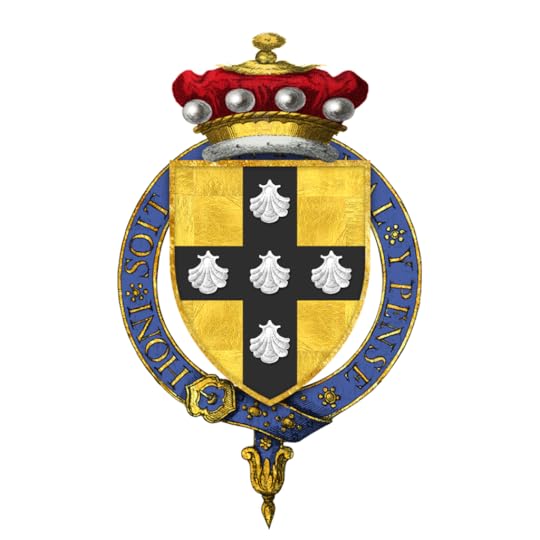

In spring 1287 Jean de Grailly, seneschal of Gascony, was put on trial on charges of corruption and embezzlement. He had been removed from office the previous summer, but the enquiry only went ahead when Edward I and Eleanor of Castile arrived in the duchy.

In spring 1287 Jean de Grailly, seneschal of Gascony, was put on trial on charges of corruption and embezzlement. He had been removed from office the previous summer, but the enquiry only went ahead when Edward I and Eleanor of Castile arrived in the duchy.This was an ignoble end to Jean's long and distinguished career in English service. He was one of the many Savoyards employed by Edward, who first picked him out in the early 1260s. In May 1262 he was described as 'knight of Edward the king's son' and received his first grant in Gascony. A year later he was described as 'counsellor of Prince Edward'.

Jean's rise in royal service closely paralleled that of his countryman, Othon Grandson. Thus, there was a sad irony in Othon's appointment as one of the justices presiding over the trial of 1287.

In many ways Jean was a bit of a hero. In 1266 he had pushed back the Navarrese invasion of Gascony, and held the invaders until Saint Louis brokered a truce. Afterwards he and Othon accompanied Edward to the Holy Land, where Jean acted as president of the High Court of Jerusalem at Acre. Upon his return, he was re-appointed seneschal of Gascony. In 1282 he served in North Wales at the head of 40 mounted crossbows, and in 1284 crushed the revolt of Constance de Béarn.

Jean's problem was a lack of discretion. Although he was on a high salary of £2000 a year, his expenses had to be approved and his wages paid by the Exchequer in London. This meant his pay was often late, so he made up the shortfall by misappropriating funds. The enquiry convicted him of abusing the rights and revenues of high and low justice in several Gascon towns, and ordered him to repay the money. Then he was sacked.

Perhaps in recognition of past service, Jean suffered no further punishment. He was allowed to go and take up service with the king of France, Philip the Fair. In 1290 he returned to the Holy Land, at the head of French troops, and barely escaped from the fall of the last Christian cities of Tripoli and Acre: he was badly wounded at the fall of Acre, and had to carried onto a ship by his old comrade, Othon.

Edward eventually took Jean back. In 1296 he appeared with the king at the Whitsun court at Roxburgh along with Othon and their countryman, Count Amadeus of Savoy. There Jean and Othon told Edward of the disaster at Acre, where “the terrible sound of the horns penetrated almost to the depths of Hell.” Jean afterwards returned to his lands in Savoy, where he died in 1302. His descendent, Jean III, was made Count of Bigorre by Edward III and fought on the English side at Poitiers.

Published on October 19, 2021 03:36

October 18, 2021

The law of Jerusalem

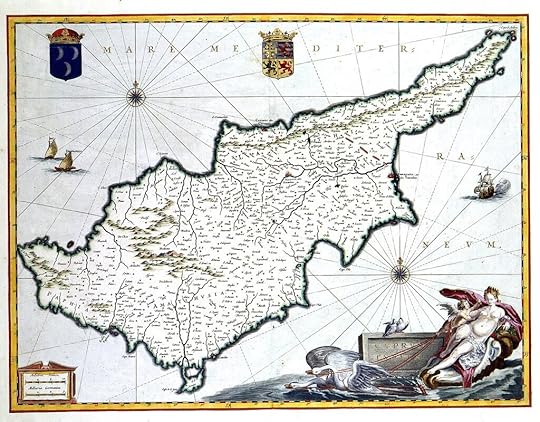

In Autumn 1270 Lord Edward was called upon to arbitrate between King Hugh Lusignan of Cyprus and James of Ibelin. The issue at stake was the law of the kingdom of Jerusalem, specifically whether the barons of Cyprus could be summoned to do military service in the Holy Land.

In Autumn 1270 Lord Edward was called upon to arbitrate between King Hugh Lusignan of Cyprus and James of Ibelin. The issue at stake was the law of the kingdom of Jerusalem, specifically whether the barons of Cyprus could be summoned to do military service in the Holy Land.The legal terminology involved is complex. Edward was invited to offer his interpretation of the laws of Jerusalem; this interpretation was called a 'reconnoissance' and the laws in question known as 'coutoume' and 'usage'.

This courtroom stuff may not be very sexy, compared to battles and castles and whatnot, but this was the subtle, highly litigious world that Edward and his peers moved in. If you really want a migraine, try delving into the detail of the Great Cause in Scotland, or the legal status of Gascony.

It was agreed that Edward's interpretation would be binding for all parties, pending a final decision by the High Court of Jerusalem at Acre. So, the English prince would not actually make the decision, but his 'reconnoissance' would carry weight with the judges of the court.

The dialogue in court between Edward, King Hugh and James was recorded by the clerk. It can still be read today, in the original Norman-French, printed in a French volume in the 19th century. If a language expert chose to translate, we would have a lengthy example of recorded speech between the three men; the closest we can get to actually listening to them talk.

Hugh argued that the laws of Cyprus and Jerusalem required the barons to serve on the mainland at the king's expense. James, speaking for the barons, replied that any such service was purely voluntary.

From Edward's perspective, it was vital he secured military support from Cyprus. He had arrived in the Holy Land to find the once-mighty Kingdom of Outremer no longer had a standing army. All that remained were the Military Orders – reduced to a few hundred knights– some scattered garrisons and Turkish mercenaries or 'Turcopoles'. Unless the barons of Cyprus agreed to cross to the mainland, Edward could not scrape together any sort of army to challenge the Mamluks.

Unfortunately the record of Edward's final judgement in court has not survived. The English chronicler, Walter of Guisborough, claimed the barons agreed to serve Edward on the basis that they had served his ancestors, specifically Richard the Lionheart. This seems most unlikely, since it would have undercut the status of King Hugh.

Edward's decision may, however, be inferred by the final sentence of the High Court at Acre. With one of his knights, Jean de Grailly, installed as president, the court ordered the barons to serve for a fixed term of four months, at the expense of King Hugh. This was an awkward fudge or compromise, but it led to some kind of result. While some Cypriot barons continued to hesitate, others agreed to cross and had joined Edward and Hugh at Acre by the start of November.

Published on October 18, 2021 04:58

October 17, 2021

King-cum-spymaster

Charles-Victor Langlois, a French medievalist, translated and published some of the correspondence between the seneschals of Gascony and kings of England in the mid to late-13th century. Langlois was especially concerned with secret correspondence, for the king's eyes only, in which the seneschals warned of French encroachment.

Charles-Victor Langlois, a French medievalist, translated and published some of the correspondence between the seneschals of Gascony and kings of England in the mid to late-13th century. Langlois was especially concerned with secret correspondence, for the king's eyes only, in which the seneschals warned of French encroachment. For instance, there is this dated c.1275, from Luke de Tany to Edward I:

"Know you, that Inquisitors of the faith want to force me, and your bailiffs of Gascony, to lead to Toulouse certain Jews from your domains that they know to be relapsed. I explained to them that I am not held to lead anyone out of your duchy, being ready to carry out their sentences there. One of them warned me he would abstain from very coercive justice until you are warned, but I do not know nevertheless if they will want to await your answer. The business is extremely serious and I beg you to treat with the aforementioned brothers, or even, if need be, with the Pope."

Unfortunately Langlois does not provide Edward's response. He does provide the king's answers to similar pleas, showing that Edward was required to play spymaster as well as justice, lawyer, steward, commander-in-chief and all the other grinding duties of medieval kingship.

The letter also shows that Philip III, king of France, was using the Inquisition to try and enforce direct French authority within Gascony. This was a consistent French policy from 1259 onward, until the inevitable war broke out in 1294.

The French made no attempt to hide their intentions. When Pope Boniface VIII asked Pierre Flotte, the French chancellor, if his master Philip IV intended to drive the English from their last holdings on the continent, Flotte replied bluntly:

"Certainly, sir, what you say is true."

Published on October 17, 2021 06:09

October 16, 2021

Survive or perish?

In 1068 three of the sons of Harold Godwinson, led by the eldest, Godwin, landed in Somerset. Their army consisted of Harold's surviving huscarls and a force of Irish/Vikings provided by King Diarmait of Leinster.

In 1068 three of the sons of Harold Godwinson, led by the eldest, Godwin, landed in Somerset. Their army consisted of Harold's surviving huscarls and a force of Irish/Vikings provided by King Diarmait of Leinster.The brothers hoped to gain local support and challenge William of Normandy. Instead they were confronted by local English levies led by Eadnoth the Staller ('Constable'), a powerful Anglo-Saxon landowner who had served as steward to Edward the Confessor and Harold.

Eadnoth was one Englishman who regarded William as a legitimate king: a man he was prepared to serve, and die for. And die he did. The armies clashed in a bloody battle at Bleadon. Eadnoth was killed, but the invaders suffered heavy casualties and retreated to their ships.

Few talk of the battle of Bleadon. An English army fighting on behalf of William the Bastard against fellow Englishmen? Quick, stuff that under the carpet. We like our history in shades of black and white, thank you very much.

Eadnoth's son, Heardinge, was treated shabbily at first. Instead of being allowed to inherit his father's lands, they were snatched away and granted to Hugh d'Avranches, earl of Chester. Heardinge was tenacious, however, and spent the rest of his life fighting to recover his inheritance in the law courts. William of Malmesbury described him thus:

“One more accustomed to sharpen his tongue for litigious ends than to make steel clash on steel in battle.”

This judgement is unfair. If Heardinge was litigious, it was because he had little choice. Resorting to force – 'steel on steel' – would have achieved nothing.

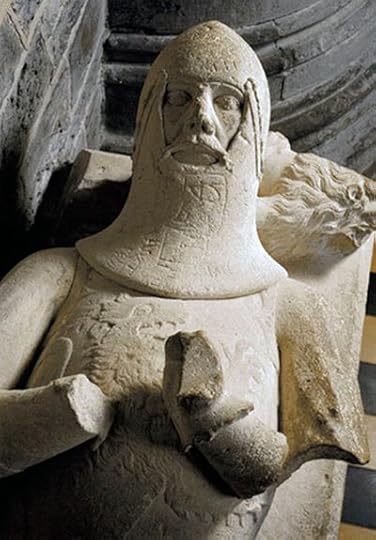

Despite being landless, Heardinge rose in favour at the Norman court. He was particularly favoured by Henry I, and witnessed several of the king's charters. Although he never recovered his inheritance, Heardinge made up for the losses elsewhere. He became the King's Reeve in Bristol and his son, Robert FitzHarding – note the Norman styling – was a wealthy Bristol merchant and financier to the English crown.

Robert was granted the barony of Berkeley in Gloucestershire. He rebuilt the castle and founded the Berkeley family, who still occupy it today. Robert FitzHarding was also the founder of St Augustine's abbey – which became Bristol Cathedral after the Reformation – and became an immensely rich landowner under Henry II. He became a canon of the abbey shortly before his death in 1170. There is a stained glass image of him at the cathedral (attached).

Here, then, was one family of Anglo-Saxon landowners who did well out of the Norman Conquest. They might be compared to certain Welsh gentry who found a place for themselves in the new regime of postconquest Wales after 1282; men such as Gruffudd Llwyd, Morgan ap Maredudd etc. What are you going to do – survive or perish?

Published on October 16, 2021 01:08

October 14, 2021

Glorified grave-diggers

On 28 December 1278, at Windsor, Edward I appointed a new provost and confraternity of the Brotherhood of St Edward the Confessor, one of the lesser-known Military Orders in the Holy Land. They were specifically instructed to take custody of the tower at Acre, which Edward had built while he was in the Holy Land.

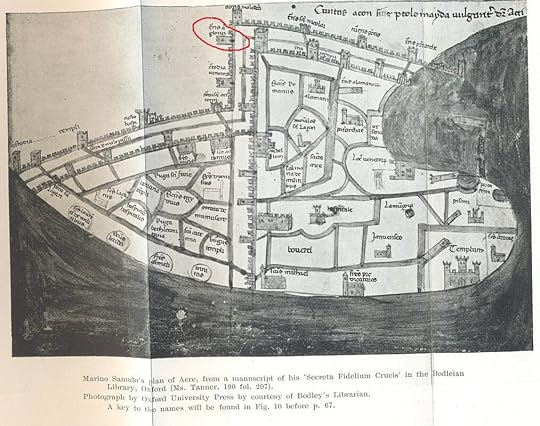

On 28 December 1278, at Windsor, Edward I appointed a new provost and confraternity of the Brotherhood of St Edward the Confessor, one of the lesser-known Military Orders in the Holy Land. They were specifically instructed to take custody of the tower at Acre, which Edward had built while he was in the Holy Land.This tower, called the English tower or 'turres Anglorum', was apparently part of the outer defences of Acre. It seems to appear on a map of Acre (attached, ringed in red) executed by Marino Saduno in the fourteenth century, although I can't make out the tiny caption. An earlier map by Paulinus Puteoli, dated 1285, shows the English tower on a section of wall defended by Cypriot and Teutonic knights in 1290-91. Unfortunately I cannot find a version of Puteoli's map on the net.

Edward supported two particular Military Orders in the Holy Land, the aforesaid Confraternity of St Edward, and the Order of St Thomas. Both had strong English connections: the Order of St Thomas was founded in 1191, and established largely as a result of English participation in the Third Crusade. They established a church and hospital at Acre, where the Master's duties included:

“To attend the poor, and especially the burial of the bodies of those who had perished from disease, as well as those slain in battle.”

These Orders weren't just glorified doctors and grave-diggers, of course. Their chief purpose was to guard the holy places, and the knights of St Thomas did just that. A 14th century account, the Chronicon equites Teutonici, records that Edward paid for the maintenance of the soldiers of St Thomas until the fall of Acre in 1291, when they were virtually wiped out. Some of the brethren survived, however, and found refuge in England.

The king's support for the English order of St Thomas seems to have gone further. In a debate in parliament in 1314, the order claimed that Edward I had appointed one Henry Dunholm as their master in 1292. For some reason this appointment was challenged by the Knights Templar, but the king 'set his hand against the Templars' in the dispute.

Published on October 14, 2021 04:27

October 13, 2021

Fake news

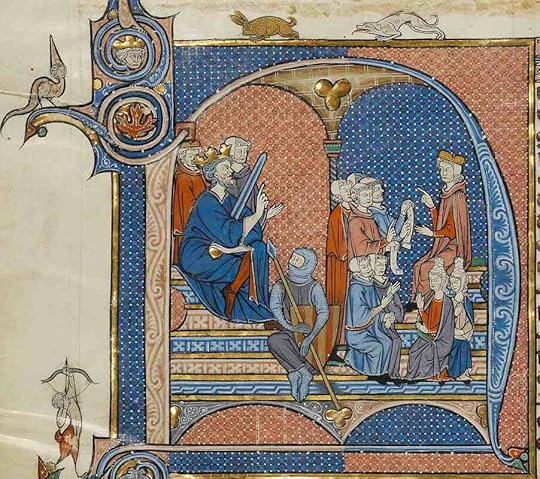

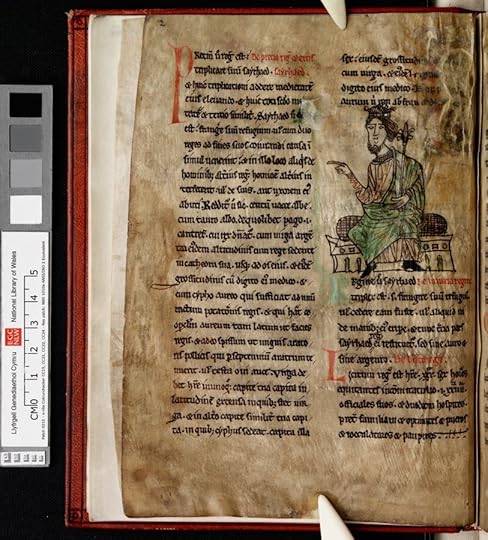

An image of the law-book of Hywel Dda, a 10th century king of Wales whose name is usually linked with the codification of Welsh law.

An image of the law-book of Hywel Dda, a 10th century king of Wales whose name is usually linked with the codification of Welsh law. I've just started reading an essay on the subject of medieval Welsh jurisprudence by Huw Pryce. He refers to a 13th century text I've never heard of before. Quote: "...a Welsh legal text which sought to provide pseudo-historical justification for the supremacy of the prince of Gwynedd over other native Welsh rulers, claiming that the sixth-century king, Maelgwn Gwynedd, with his court at Aberffraw, had been given superiority over the 'earls' of Mathrafal, Dinefwr and Caerleon."

This text is apparently one of several false histories cooked up by Venedotian jurists, particularly in the time of Llywelyn the Great, to justify the supremacy of Gwynedd over the whole of Wales. They were probably connected with Llywelyn's adoption of the title 'prince of Aberffraw and lord of Snowdon' in 1230, which has been interpreted as an assertion of overlordship over other Welsh rulers.

The revelation that the princes of Gwynedd were dealing in fake history is not surprising. This was a standard tactic of the era: perhaps the most notorious within the British Isles is Edward I's bogus attempts to enforce his overlordship over Scotland, using the same methods as Llywelyn. Edward's sometime allies/sometime enemies, the Bruces, also dealt in pseudo-history and - on at least two occasions - forged documents to press their claim to the Scottish throne.

Devious buggers, all of 'em. But very clever.

Published on October 13, 2021 06:44

October 12, 2021

The battle of Aberduhonw

In October 1208 the battle of Aberduhonw took place near Builth Wells. This was a consequence of the failed revolt of the Braose family against King John. After the Braoses had fled to Ireland, John sent Gerard Athée, sheriff of Gloucester, to march through the semi-pacified land of Brecon to conquer the Braose lordship of Builth.

In October 1208 the battle of Aberduhonw took place near Builth Wells. This was a consequence of the failed revolt of the Braose family against King John. After the Braoses had fled to Ireland, John sent Gerard Athée, sheriff of Gloucester, to march through the semi-pacified land of Brecon to conquer the Braose lordship of Builth.A few years earlier William Braose had granted the land of Buellt and castle of Caer Beris to his grandsons, Rhys Ieuanc and Owain ap Gruffudd. They were the sons of William's daughter, Matilda, and her husband King Gruffudd ap Rhys of South Wales. Thus, they were also the grandsons of the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth.

King Gruffudd had fought in the victorious 'English' army at Painscastle in 1198, and attended King John at Lincoln in November 1200. After his death in 1201, his sons continued to support their exiled Braose kin and so incurred John's enmity.

This was the context of the battle. Only one source, the Cronica Wallia, describes it. This chronicle has a political subtext: it was commissioned by the princes of Deheubarth in the reign of Edward I to justify their claims to land ownership before the Hopton Commission of 1278-82. The content was thus geared towards the restoration of the lineage of the Lord Rhys, albeit under the auspice of the English crown.

The chronicle states that after 29 September Gerard Athée invaded the lands of the sons of King Gruffudd of Buellet to lay them waste and build castles. He spent the first night at the grange of Aberduhonw. The following day he advanced to the site where the Normans wished to build a castle. He found himself opposed by a combined Welsh army led by Rhys Ieuanc and Owain ap Gruffudd and their ally, 'J ab Einion'.

The Welsh had taken up position on the other side of a bend in the river Wye. Gerard's men tried to dislodge them, but failed and withdrew to the grange. The chronicler then states that the 'English' offered to surrender, and retreated after handing over money and hostages.

Interestingly, the chronicle had earlier called Gerard and his men 'French'. This may imply that the sheriff and his Norman cavalry abandoned the grange and fled, leaving the English levies to their fate. Or, the annalist was simply using interchangeable terms to describe the enemy.

Either way, it was a victory for Rhys and Owain and an embarrassment for King John. The king had his revenge the next year, 1209, when he sent the sheriff of Hereford, Thomas Herdington, to expel the two Welsh princes. He was more successful, and the brothers were forced to flee. They were remarkably dogged, however, and would return to fight for their inheritance. By 1213 they were back in King John's good books and fighting on his behalf against their kinsman, Rhys Gryg.

Published on October 12, 2021 05:53

King Panther

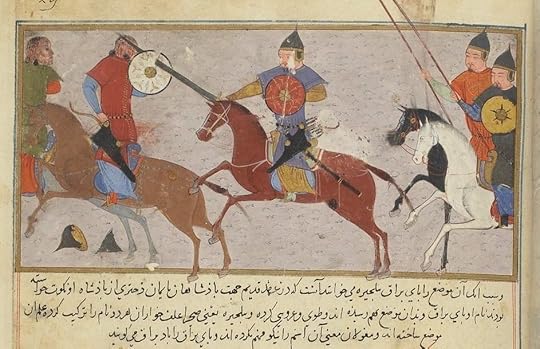

In October 1271 a force of Mongol cavalry invaded northern Syria. This was in response to a plea from Lord Edward to the il-khan, Abaqa. The latter's response to the English envoys, dated 4 September, was encouraging:

In October 1271 a force of Mongol cavalry invaded northern Syria. This was in response to a plea from Lord Edward to the il-khan, Abaqa. The latter's response to the English envoys, dated 4 September, was encouraging:“After talking over the matter, we have on our account resolved to send to your aid Samaghar at the head of a mighty force; thus, when you discuss among yourselves the other plans involving the aforementioned Samaghar be sure to make explicit arrangements as to the exact month and day on which you will engage the enemy.”

The cavalry under Abaqa's lieutenant consisted of about 10,000 Mongol lancers and Rumis, or Turkish soldiers in the service of the Mongol khanate. They rapidly pushed up the Orontes valley, past Hamah, and concentrated around the city of Damascus. Samaghar sent an advance guard of 1500 lancers on a raid. Somewhere between Antioch and Harem, they fell upon a force of Turcomen (Turkish mercenaries) and cut them to pieces.

This was part of Edward's plan to forge a Frankish-Mongol alliance. While the Mongols attacked the Mamluk sultan, Baybars, from the north, he would march south from Acre and attack the outposts guarding the approach to Jerusalem.

Baybars was not so easily humbugged. The King Panther or Father of Conquest, as his terrified enemies called him, was a soldier of genius. He knew Samaghar had no siege equipment, and so left him to raid the countryside around Damascus. Meanwhile the sultan split his field army north and east into Aleppo and towards Edessa, Marash, and the borders of Armenia.

These moves threatened to block the Mongol line of retreat. Samaghar was forced to abandon his expedition and hurriedly withdraw northeast. By the end of November, the Mongols were in full retreat back to the Euphrates, leaving Baybars free to deal with the Franks.

Published on October 12, 2021 03:42