David Pilling's Blog, page 32

February 10, 2020

Lies and hostility

The sons of Belial (1)

In March 1270 Archbishop Walter Giffard of York cited the dire state of the realm - “turbatio regni” - as the reason for his inability to visit the pope. In August of the same year, the ageing Henry III declared that his fears for the kingdom’s safety prevented him from accompanying his son, Edward, to the Holy Land.

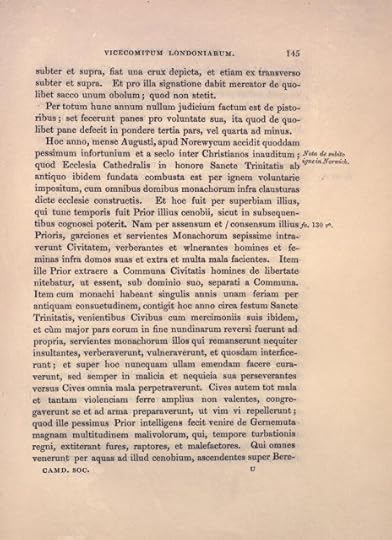

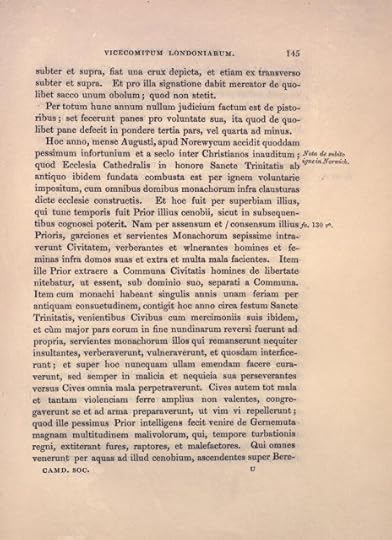

There is plenty of evidence for the disturbed state of England. The chronicle of the sheriffs of London records a projected uprising by the commons, the “populares”, against the aldermen. This was supposed to coincide with the death of Henry III. Shortly before the king’s demise in November 1272, the prior of Norwich quarreled with the men of the city and summoned to his aid “a great multidude of malivoli who, when the kingdom was disturbed, had been thieves and malefactors”. From this it appears the prior hired ex-Montfortians, bands of old soldiers wandering the land with nothing better to do than cause mayhem.

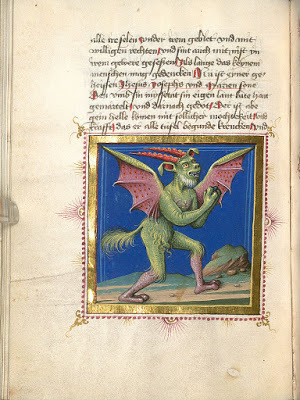

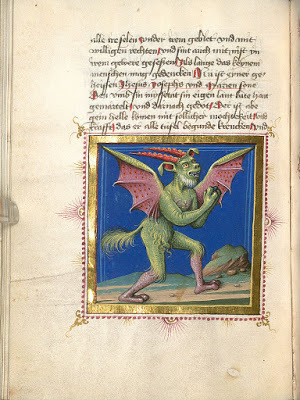

The midlands and northern counties were especially afflicted by these “malivoli”, called the Sons of Belial or sons of wickedness by the London chronicler. In scripture Belial is a demon of lies and guilt, the king of hostility. In Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, it was reported that nobody dared to travel the Great North Road because the counties were overrun by an army of outlaws. Their leader was Roger Godberd, a former tenant of Earl Ferrers who went back into revolt after his master was disinherited.

After Henry’s death, the regency government was especially fearful of old seats of rebellion. In August 1273 Walter Merton, the chancellor, spoke of bands of malivoli gathering together and conspiring to break the peace in Essex and Leicestershire. This was worrying since Leicestershire had been a Montfortian heartland; it was the county of the villagers of Great Peatling, who had attacked the king’s men after the battle of Evesham for “going against the commonalty of the realm and against the barons”. Here, if anywhere, trouble would arise.

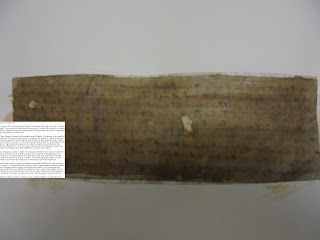

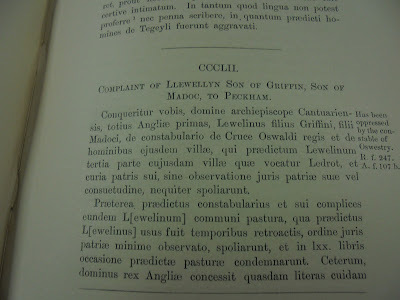

Merton’s letter has survived (see third pic) but is virtually illegible even under ultraviolet.

In March 1270 Archbishop Walter Giffard of York cited the dire state of the realm - “turbatio regni” - as the reason for his inability to visit the pope. In August of the same year, the ageing Henry III declared that his fears for the kingdom’s safety prevented him from accompanying his son, Edward, to the Holy Land.

There is plenty of evidence for the disturbed state of England. The chronicle of the sheriffs of London records a projected uprising by the commons, the “populares”, against the aldermen. This was supposed to coincide with the death of Henry III. Shortly before the king’s demise in November 1272, the prior of Norwich quarreled with the men of the city and summoned to his aid “a great multidude of malivoli who, when the kingdom was disturbed, had been thieves and malefactors”. From this it appears the prior hired ex-Montfortians, bands of old soldiers wandering the land with nothing better to do than cause mayhem.

The midlands and northern counties were especially afflicted by these “malivoli”, called the Sons of Belial or sons of wickedness by the London chronicler. In scripture Belial is a demon of lies and guilt, the king of hostility. In Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, it was reported that nobody dared to travel the Great North Road because the counties were overrun by an army of outlaws. Their leader was Roger Godberd, a former tenant of Earl Ferrers who went back into revolt after his master was disinherited.

After Henry’s death, the regency government was especially fearful of old seats of rebellion. In August 1273 Walter Merton, the chancellor, spoke of bands of malivoli gathering together and conspiring to break the peace in Essex and Leicestershire. This was worrying since Leicestershire had been a Montfortian heartland; it was the county of the villagers of Great Peatling, who had attacked the king’s men after the battle of Evesham for “going against the commonalty of the realm and against the barons”. Here, if anywhere, trouble would arise.

Merton’s letter has survived (see third pic) but is virtually illegible even under ultraviolet.

Published on February 10, 2020 04:13

February 9, 2020

Stitching things together

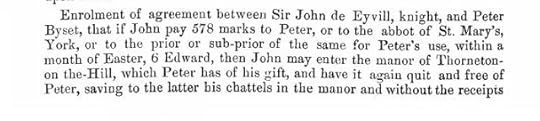

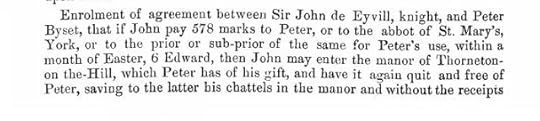

On 10 December 1276 Sir John Deyville paid 578 marks (roughly £400) to 'Peter Byset or to the abbot of St Mary's York', thus gaining the right to re-occupy his Yorkshire manor of Thornton-on-the-Hill on 20 September. This appears to have been the final redemption fine he owed to the queen, Eleanor of Provence, as the price for his rebellion in the previous decade.

This redemption fine is a quite striking parallel to an episode in the Geste of Robyn Hode, in which the outlaw entertains an impoverished military knight. Robyn takes pity on the knights and lends him the £400 he needs to redeem pledged lands from the abbot of St Mary's, York. Such a contract was unlikely after 1279, after which restrictions on lending were imposed on religious houses by the Statute of Mortmain.

This redemption fine is a quite striking parallel to an episode in the Geste of Robyn Hode, in which the outlaw entertains an impoverished military knight. Robyn takes pity on the knights and lends him the £400 he needs to redeem pledged lands from the abbot of St Mary's, York. Such a contract was unlikely after 1279, after which restrictions on lending were imposed on religious houses by the Statute of Mortmain.

In later versions of the legend the 'poor knyghte' acquires a name, Sir Richard Atte Lee or Sir Richard of the Lea. This was because two separate manuscripts, recording the deeds of Robin Hood, were literally stitched together to form a single narrative.

This redemption fine is a quite striking parallel to an episode in the Geste of Robyn Hode, in which the outlaw entertains an impoverished military knight. Robyn takes pity on the knights and lends him the £400 he needs to redeem pledged lands from the abbot of St Mary's, York. Such a contract was unlikely after 1279, after which restrictions on lending were imposed on religious houses by the Statute of Mortmain.

This redemption fine is a quite striking parallel to an episode in the Geste of Robyn Hode, in which the outlaw entertains an impoverished military knight. Robyn takes pity on the knights and lends him the £400 he needs to redeem pledged lands from the abbot of St Mary's, York. Such a contract was unlikely after 1279, after which restrictions on lending were imposed on religious houses by the Statute of Mortmain.

In later versions of the legend the 'poor knyghte' acquires a name, Sir Richard Atte Lee or Sir Richard of the Lea. This was because two separate manuscripts, recording the deeds of Robin Hood, were literally stitched together to form a single narrative.

Published on February 09, 2020 09:52

Double ditched

"There was there a fair castle,

A little within the wood;

Double-ditched it was about, And walléd, by the rood."

- The Geste of Robyn Hode (mid-15th century)

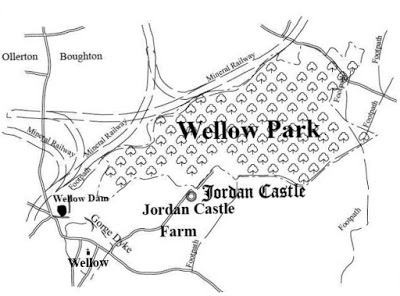

This verse describes the castle of Sir Richard Atte Lee, who gives Robin Hood and his men sanctuary from the wicked High Sheriff of Nottingham. This tale was possibly inspired by Wellow or Jordan Castle near Rufford Abbey in the heart of Sherwood Forest. Wellow was a ringwork castle of the motte and bailey type, updated in 1252 with the addition of a fortified manor house on the motte. It was protected by a moat and the nearby village was surrounded by a ditch, so Wellow was 'double ditched', just like the ballad.

In 1272 Sir Richard Foliot, a former Montfortian-cum-royalist who could never quite make up his mind, was accused of harbouring outlaws on his estates. This was the band led by Roger Godberd, one of the legion of real-life Robin Hoods. Foliot probably sheltered them at Jordan, since it lay midway between his other manors at Fenwick and Grimston.

In the ballad Sir Richard Atte Lee takes the outlaws into his castle and proudly defies the sheriff to do his worst. In the real world Sir Richard Foliot went grovelling to Henry III, who rolled his eyes a bit and pardoned him. Godberd and the lads made themselves scarce.

A little within the wood;

Double-ditched it was about, And walléd, by the rood."

- The Geste of Robyn Hode (mid-15th century)

This verse describes the castle of Sir Richard Atte Lee, who gives Robin Hood and his men sanctuary from the wicked High Sheriff of Nottingham. This tale was possibly inspired by Wellow or Jordan Castle near Rufford Abbey in the heart of Sherwood Forest. Wellow was a ringwork castle of the motte and bailey type, updated in 1252 with the addition of a fortified manor house on the motte. It was protected by a moat and the nearby village was surrounded by a ditch, so Wellow was 'double ditched', just like the ballad.

In 1272 Sir Richard Foliot, a former Montfortian-cum-royalist who could never quite make up his mind, was accused of harbouring outlaws on his estates. This was the band led by Roger Godberd, one of the legion of real-life Robin Hoods. Foliot probably sheltered them at Jordan, since it lay midway between his other manors at Fenwick and Grimston.

In the ballad Sir Richard Atte Lee takes the outlaws into his castle and proudly defies the sheriff to do his worst. In the real world Sir Richard Foliot went grovelling to Henry III, who rolled his eyes a bit and pardoned him. Godberd and the lads made themselves scarce.

Published on February 09, 2020 04:28

February 7, 2020

Old and New

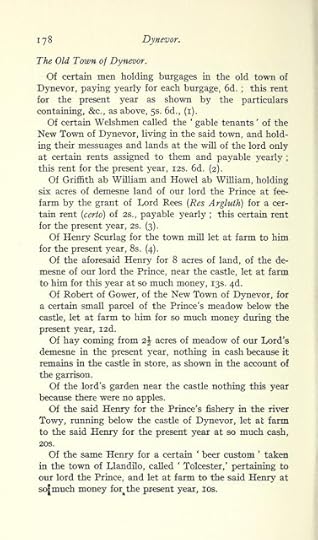

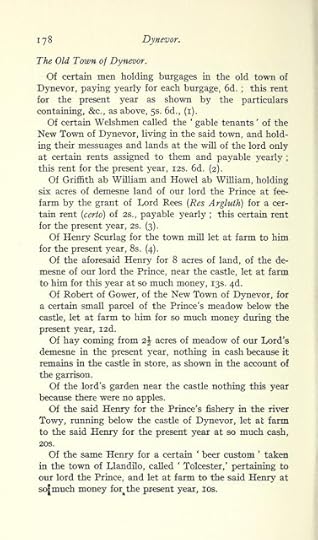

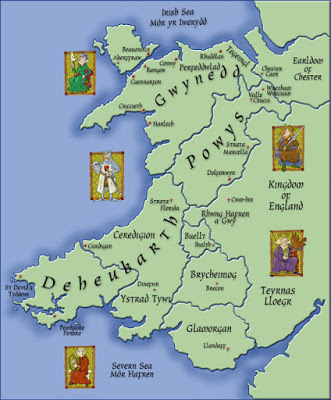

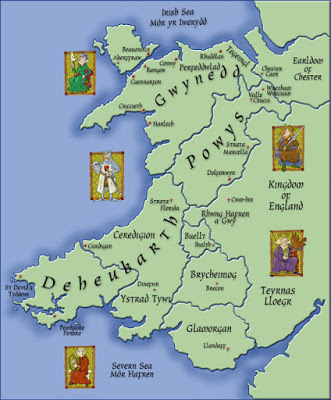

The hilltop castle-borough of Dinefwr in the Tywi valley, West Wales, was the ancestral seat of the ancient princes of Deheubarth. Rhys ap Maredudd, the last of these princes, was executed in 1291, but the old borough continued to exist. This was of Welsh origin and populated almost exclusively by Welsh tenants.

A new borough was planted on the old in about 1298. This was supposed to be an English colony, like others at Beaumaris and elsewhere, and at first the commercial privileges granted to the old Welsh cottagers were appropriated by English settlers. The number of settlers or burgesses was at first 35, subsequently increased to 44.

Unlike other towns in postconquest Wales, the old borough was not demolished. A complete set of rentals and surveys survive from the period, showing how the old and new boroughs co-existed. Certain Welsh families who continued to live in the old town had evidently been there for generations. For instance, in 1300 Griffith ab William and Howel ab William held six acres by the grant of Lord Rees or “Res Argluth” i.e. the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, who died in 1197.

Some Welsh tradesmen moved from the old borough to the new. These were called “gable tenants”, apparently capitalizing on the availability of new burgage property. Everyone in Dinefwr at this time held their land and property of Edward of Caernarfon, referred to as “our lord the Prince.” The king had farmed out Wales to his son, along with the lordship of Chester, the county of Ponthieu and the duchy of Gascony. This was supposed to instil a sense of responsiblity in the future Edward II: some hope.

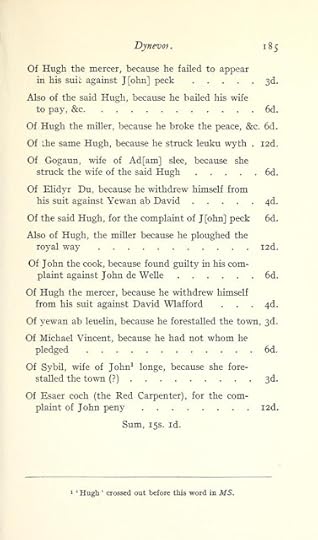

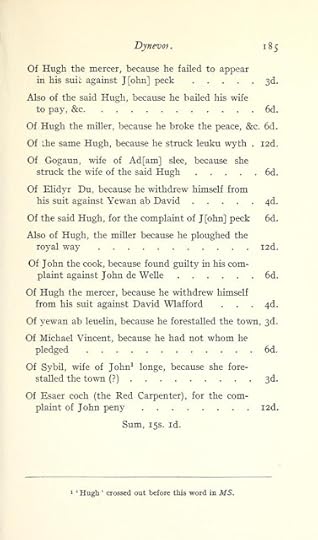

Part of a rental for the new town shows ten English burgesses living next door to seven Welsh. Given the climate of the time, the atmosphere in this mixed community must have been tense. A court roll for Dinefwr in 1300 lists various assaults and arguments in court, though it is difficult to tell if this was the result of Anglo-Welsh rivalry, or just the usual run of petty crime found in any township.

A new borough was planted on the old in about 1298. This was supposed to be an English colony, like others at Beaumaris and elsewhere, and at first the commercial privileges granted to the old Welsh cottagers were appropriated by English settlers. The number of settlers or burgesses was at first 35, subsequently increased to 44.

Unlike other towns in postconquest Wales, the old borough was not demolished. A complete set of rentals and surveys survive from the period, showing how the old and new boroughs co-existed. Certain Welsh families who continued to live in the old town had evidently been there for generations. For instance, in 1300 Griffith ab William and Howel ab William held six acres by the grant of Lord Rees or “Res Argluth” i.e. the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, who died in 1197.

Some Welsh tradesmen moved from the old borough to the new. These were called “gable tenants”, apparently capitalizing on the availability of new burgage property. Everyone in Dinefwr at this time held their land and property of Edward of Caernarfon, referred to as “our lord the Prince.” The king had farmed out Wales to his son, along with the lordship of Chester, the county of Ponthieu and the duchy of Gascony. This was supposed to instil a sense of responsiblity in the future Edward II: some hope.

Part of a rental for the new town shows ten English burgesses living next door to seven Welsh. Given the climate of the time, the atmosphere in this mixed community must have been tense. A court roll for Dinefwr in 1300 lists various assaults and arguments in court, though it is difficult to tell if this was the result of Anglo-Welsh rivalry, or just the usual run of petty crime found in any township.

Published on February 07, 2020 07:55

February 3, 2020

The end of the dragon

The Dragon of Chirk (6, and last)

In 1282 Llywelyn Fychan of Bromfield chose to join Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in his final war against Edward I. Five years earlier the lord of Bromfield had fought for Edward against Llywelyn, probably because he was unhappy at the prince’s division of Powys Fadog and efforts to take direct control of the lordship. Now he returned to his former allegiance.

Shortly before he broke with the king, Llywelyn Fychan submitted a petition that listed his complains. This is a separate protest to the one in Archbishop Peckham’s register. Among other things, Llywelyn refused to accept the authority of the judges appointed by the king to enquire into the native law of Wales. One of these judges was Hywel ap Meurig, a royal justice and bailiff to the Mortimers of Wigmore. Llywelyn named Hywel as one of his enemies along with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys.

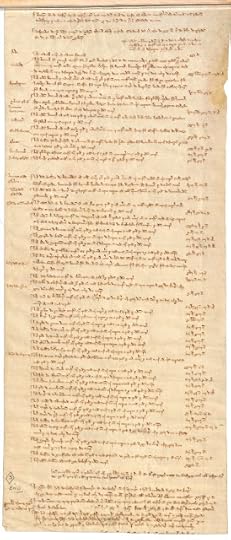

In the previous war of 1277, Hywel had led the men of Powys, Radnor and Builth against Prince Llywelyn and invaded southern Snowdonia on behalf of the king: attached (above) is the first membrane of the payroll for this army. He remained a crown loyalist and his sons rose to high office under Edward I and Edward II. Thus Wales was split between Prince Llywelyn and his supporters on the one hand, and crown loyalists such as Hywel and Gwenwynwyn on the other.

Llywelyn Fychan’s fate was to die with his prince near Cilmeri in December 1282, slaughtered along with all the cavalry and part of the infantry. He was probably slain by Andrew Astley, a Marcher lord who seems to have boasted of his exploit by taking Llywelyn’s arms, the lion of Powys Fadog, and adding it to the Astley cinquefoil. Sixteen years later Astley fought under these converted arms at the Battle of Falkirk.

The arms of Andrew Astley

The arms of Andrew Astley

And that was the end of the dragon of Chirk:

“Hail thou of great and high discretion,

From God the foremost leader of forces;

Prosperous elder of the excelling spear,

Inexorable is your wrath, thou wall in battle.”

- Llygad Gwr

In 1282 Llywelyn Fychan of Bromfield chose to join Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in his final war against Edward I. Five years earlier the lord of Bromfield had fought for Edward against Llywelyn, probably because he was unhappy at the prince’s division of Powys Fadog and efforts to take direct control of the lordship. Now he returned to his former allegiance.

Shortly before he broke with the king, Llywelyn Fychan submitted a petition that listed his complains. This is a separate protest to the one in Archbishop Peckham’s register. Among other things, Llywelyn refused to accept the authority of the judges appointed by the king to enquire into the native law of Wales. One of these judges was Hywel ap Meurig, a royal justice and bailiff to the Mortimers of Wigmore. Llywelyn named Hywel as one of his enemies along with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys.

In the previous war of 1277, Hywel had led the men of Powys, Radnor and Builth against Prince Llywelyn and invaded southern Snowdonia on behalf of the king: attached (above) is the first membrane of the payroll for this army. He remained a crown loyalist and his sons rose to high office under Edward I and Edward II. Thus Wales was split between Prince Llywelyn and his supporters on the one hand, and crown loyalists such as Hywel and Gwenwynwyn on the other.

Llywelyn Fychan’s fate was to die with his prince near Cilmeri in December 1282, slaughtered along with all the cavalry and part of the infantry. He was probably slain by Andrew Astley, a Marcher lord who seems to have boasted of his exploit by taking Llywelyn’s arms, the lion of Powys Fadog, and adding it to the Astley cinquefoil. Sixteen years later Astley fought under these converted arms at the Battle of Falkirk.

The arms of Andrew Astley

The arms of Andrew AstleyAnd that was the end of the dragon of Chirk:

“Hail thou of great and high discretion,

From God the foremost leader of forces;

Prosperous elder of the excelling spear,

Inexorable is your wrath, thou wall in battle.”

- Llygad Gwr

Published on February 03, 2020 12:29

Peckham's register

The Dragon of Chirk (5)

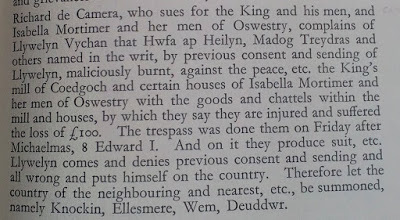

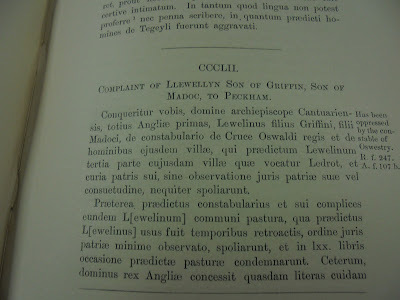

The printed register of John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury, contains all of the complaints submitted by Welsh lords and communities against royal government between 1277-82. It is an invaluable record of events leading up to the war of 1282 and the conquest of Wales. To gain any kind of proper understanding, each complaint needs to be considered on its own merits.

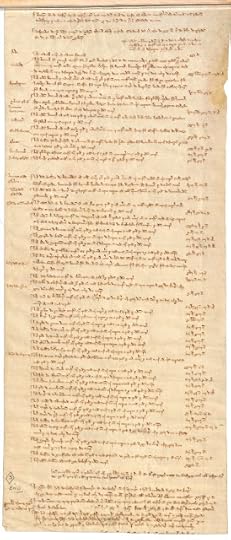

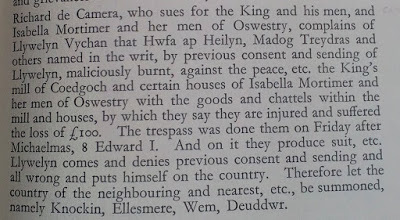

One such is the protest of Llywelyn Fychan of Bromfield. He was engaged in a private war against the men of Oswestry and Ellesmere, and at the same time at loggerheads with fellow Marcher lords. His principal enemies were Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn and the Lestranges of Knockin.

Llywelyn claimed the constable of Oswestry had plundered a third part of the vill of Lledrod, a township of Llansilin, and his father’s court, which lay nearby. They had also stolen his pastureland, along with £70 of Llywelyn’s money. The same constable allegedly hanged two of Llywelyn’s officers and imprisoned sixty others, only releasing them on a payment of 10 shillings per head. He also seized cattle when the beasts were brought to market and detained them at Oswestry castle, refusing to return or pay for them. The same constable stole pack-horses as well as Llywelyn’s own horse.

Worst of all (he claimed), Llywelyn himself, when on the road to Chester carrying letters from the king, had been ambushed and kidnapped by the soldiers of Gwenwynwyn and Roger Lestrange. He and his men were held in prison until they bought themselves out. This protest should be cross-referenced with a separate entry in the Welsh assize roll. The latter reveals that Llywelyn had sent his men to burnt the mill at Coedgoch and houses belonging to Isabella Mortimer and the men of Oswestry, to the value of £100. Or so they alleged.

The truth of all this is impossible to sift, but it is clear that the situation in Wales was steadily darkening. Once again the Mortimers of Wigmore were at the heart of it.

[The first pic is of Peckham’s effigy]

The printed register of John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury, contains all of the complaints submitted by Welsh lords and communities against royal government between 1277-82. It is an invaluable record of events leading up to the war of 1282 and the conquest of Wales. To gain any kind of proper understanding, each complaint needs to be considered on its own merits.

One such is the protest of Llywelyn Fychan of Bromfield. He was engaged in a private war against the men of Oswestry and Ellesmere, and at the same time at loggerheads with fellow Marcher lords. His principal enemies were Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn and the Lestranges of Knockin.

Llywelyn claimed the constable of Oswestry had plundered a third part of the vill of Lledrod, a township of Llansilin, and his father’s court, which lay nearby. They had also stolen his pastureland, along with £70 of Llywelyn’s money. The same constable allegedly hanged two of Llywelyn’s officers and imprisoned sixty others, only releasing them on a payment of 10 shillings per head. He also seized cattle when the beasts were brought to market and detained them at Oswestry castle, refusing to return or pay for them. The same constable stole pack-horses as well as Llywelyn’s own horse.

Worst of all (he claimed), Llywelyn himself, when on the road to Chester carrying letters from the king, had been ambushed and kidnapped by the soldiers of Gwenwynwyn and Roger Lestrange. He and his men were held in prison until they bought themselves out. This protest should be cross-referenced with a separate entry in the Welsh assize roll. The latter reveals that Llywelyn had sent his men to burnt the mill at Coedgoch and houses belonging to Isabella Mortimer and the men of Oswestry, to the value of £100. Or so they alleged.

The truth of all this is impossible to sift, but it is clear that the situation in Wales was steadily darkening. Once again the Mortimers of Wigmore were at the heart of it.

[The first pic is of Peckham’s effigy]

Published on February 03, 2020 04:20

February 1, 2020

The obstinate spear

The Dragon of Chirk (4)

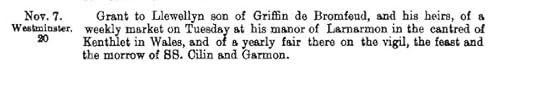

In the years after 1277, Llywelyn found that his defection to the English crown was not a passport to joy. He did not go without rewards: in November 1279 the king granted him and his heirs a weekly market and annual fair at Llanarmon Dyffryn Ceiriog in Cynllaith. This promised to create new wealth in the lordship, but also caused friction with the rival market at Oswestry.

Llywelyn had a bitter ongoing feud with the men of Ellesmere and Oswestry. Ellesmere had only been part of England for about thirty years, since Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn surrendered it to Henry III. The town was previously part of the marriage portion of King Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd and Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, when they took English royal wives. By the reign of Edward I, though located in the east of the north Shropshire borderland, Ellesmere still supported a significant Welsh population.

Llywelyn had a bitter ongoing feud with the men of Ellesmere and Oswestry. Ellesmere had only been part of England for about thirty years, since Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn surrendered it to Henry III. The town was previously part of the marriage portion of King Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd and Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, when they took English royal wives. By the reign of Edward I, though located in the east of the north Shropshire borderland, Ellesmere still supported a significant Welsh population.

A (possible) bust of Llywelyn the Great

A (possible) bust of Llywelyn the Great

Shortly after the war ended, Llywelyn complained to the king that certain of “the Welsh” were rejoicing at his difficulties. These Welsh can probably be identified with the men of Ellesmere, whom the poet Llygad Gwr encouraged Llywelyn to attack:

“Llywelyn, may there be a host of armed steeds,

And fame and the conquest of the vale of Ceiriog.

Thou brave one of the claim of content and of the long wrathful charge,

Who makes commotion with your men, may they be submissive

To you, the dragon of Chirk, with the obstinate spear;

And burning Whittingdon be yours, overshadowing lord.

And may Ellesmere bear your wounds, thou of the honoured following.

Fleet eagle of spears, of subduing vehemence,

In the front of battle almighty prince…”

To add to his problems, Ellesmere and Oswestry were under the jurisdiction of Roger and John Lestrange of Knockin, whom Llywelyn hated. When Roger gave shelter to the men of Whittingdon, Llywelyn informed the king in no uncertain terms that the Lestranges were:

“...our enemies and challenge us for other lands of our right and to whom we do not propose in the least to show faith nor ought we.”

In the years after 1277, Llywelyn found that his defection to the English crown was not a passport to joy. He did not go without rewards: in November 1279 the king granted him and his heirs a weekly market and annual fair at Llanarmon Dyffryn Ceiriog in Cynllaith. This promised to create new wealth in the lordship, but also caused friction with the rival market at Oswestry.

Llywelyn had a bitter ongoing feud with the men of Ellesmere and Oswestry. Ellesmere had only been part of England for about thirty years, since Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn surrendered it to Henry III. The town was previously part of the marriage portion of King Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd and Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, when they took English royal wives. By the reign of Edward I, though located in the east of the north Shropshire borderland, Ellesmere still supported a significant Welsh population.

Llywelyn had a bitter ongoing feud with the men of Ellesmere and Oswestry. Ellesmere had only been part of England for about thirty years, since Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn surrendered it to Henry III. The town was previously part of the marriage portion of King Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd and Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, when they took English royal wives. By the reign of Edward I, though located in the east of the north Shropshire borderland, Ellesmere still supported a significant Welsh population. A (possible) bust of Llywelyn the Great

A (possible) bust of Llywelyn the GreatShortly after the war ended, Llywelyn complained to the king that certain of “the Welsh” were rejoicing at his difficulties. These Welsh can probably be identified with the men of Ellesmere, whom the poet Llygad Gwr encouraged Llywelyn to attack:

“Llywelyn, may there be a host of armed steeds,

And fame and the conquest of the vale of Ceiriog.

Thou brave one of the claim of content and of the long wrathful charge,

Who makes commotion with your men, may they be submissive

To you, the dragon of Chirk, with the obstinate spear;

And burning Whittingdon be yours, overshadowing lord.

And may Ellesmere bear your wounds, thou of the honoured following.

Fleet eagle of spears, of subduing vehemence,

In the front of battle almighty prince…”

To add to his problems, Ellesmere and Oswestry were under the jurisdiction of Roger and John Lestrange of Knockin, whom Llywelyn hated. When Roger gave shelter to the men of Whittingdon, Llywelyn informed the king in no uncertain terms that the Lestranges were:

“...our enemies and challenge us for other lands of our right and to whom we do not propose in the least to show faith nor ought we.”

Published on February 01, 2020 07:15

Of land and lordship

The Dragon of Chirk (3) The war of 1277 ended with mixed fortunes for the sons of Gruffudd ap Madog. They all survived it, though not for very long in the case of Madog, the eldest. He died a month after the Treaty of Aberconwy in November, leaving two young sons and a widow.

Of the others, Gruffydd Fychan was the only one to stand by Prince Llywelyn during the war. He was pardoned by the king and permitted to hold part of Edeirnion and Ial as a tenant-in-chief. Llywelyn Fychan and Owain retained their lands.

A fresh disaster then swept over Powys Fadog. The territory had been subdivided twice in six years, first by Prince Llywelyn and then by King Edward, exposing the weakness of Gruffudd’s dynasty. Suddenly a glut of long-lost heirs popped out of the woodwork, all claiming to be descendants of ancient Powysian princes. These men had long since been deprived of land and lordship, but now they smelled blood.

The claimants included the four sons of Einion ap Gruffudd of Bromfield, who demanded part of Cynllaith; Gruffudd ap Gruffudd of Kinnerton, his three brothers and a certain Iorwerth Fychan, all descendants of Iorwerth Goch ap Maredudd (died 1171), who demanded the lands of Nanheudwy, Mochnant Is Rhaeadr and Cynllaith; and a certain Roger ap Gruffudd of Bromfield, who demanded one-fifth part of Bromfield, Nanheudwy, Ial and Mochnant Is Rhaeadr.

Roger claimed to be another son of Gruffudd ap Madog. If true, this is very odd: he was the only one to have an English name and doesn’t appear on any previous documents or charters. Possibly he was a bastard, fathered by Gruffudd on an unknown Englishwoman. Llywelyn Fychan and his brother Owain denied Roger’s right in court at Montgomery, held at Michaelmas in 1281.

A Welsh judge or ynaid

A Welsh judge or ynaid

Llywelyn and his brothers refused to surrender an inch of ground to these upstarts. The sons of Einion ap Gruffudd won their case in respect of the vill of Nancennin, and the king’s bailiff of Dinas Bran was ordered to put them in possession. He reported he could not so because of the power of Llywelyn Fychan, who refused a direct order from royal justices to give up the vill.

Of the others, Gruffydd Fychan was the only one to stand by Prince Llywelyn during the war. He was pardoned by the king and permitted to hold part of Edeirnion and Ial as a tenant-in-chief. Llywelyn Fychan and Owain retained their lands.

A fresh disaster then swept over Powys Fadog. The territory had been subdivided twice in six years, first by Prince Llywelyn and then by King Edward, exposing the weakness of Gruffudd’s dynasty. Suddenly a glut of long-lost heirs popped out of the woodwork, all claiming to be descendants of ancient Powysian princes. These men had long since been deprived of land and lordship, but now they smelled blood.

The claimants included the four sons of Einion ap Gruffudd of Bromfield, who demanded part of Cynllaith; Gruffudd ap Gruffudd of Kinnerton, his three brothers and a certain Iorwerth Fychan, all descendants of Iorwerth Goch ap Maredudd (died 1171), who demanded the lands of Nanheudwy, Mochnant Is Rhaeadr and Cynllaith; and a certain Roger ap Gruffudd of Bromfield, who demanded one-fifth part of Bromfield, Nanheudwy, Ial and Mochnant Is Rhaeadr.

Roger claimed to be another son of Gruffudd ap Madog. If true, this is very odd: he was the only one to have an English name and doesn’t appear on any previous documents or charters. Possibly he was a bastard, fathered by Gruffudd on an unknown Englishwoman. Llywelyn Fychan and his brother Owain denied Roger’s right in court at Montgomery, held at Michaelmas in 1281.

A Welsh judge or ynaid

A Welsh judge or ynaidLlywelyn and his brothers refused to surrender an inch of ground to these upstarts. The sons of Einion ap Gruffudd won their case in respect of the vill of Nancennin, and the king’s bailiff of Dinas Bran was ordered to put them in possession. He reported he could not so because of the power of Llywelyn Fychan, who refused a direct order from royal justices to give up the vill.

Published on February 01, 2020 07:11

January 31, 2020

A lesson to us all...sort of...

The Dragon of Chirk (2)

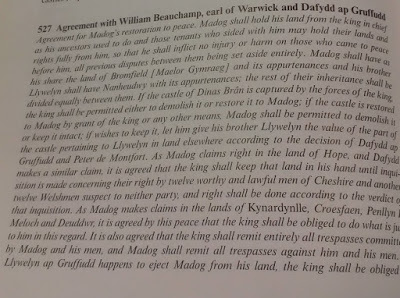

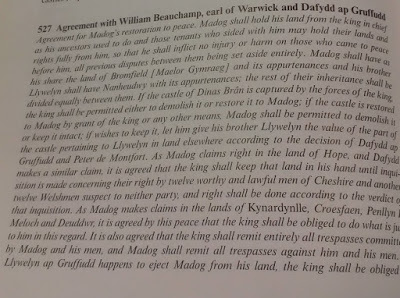

On 12 April 1277 Madog ap Gruffudd, eldest son of Gruffudd of Bromfield, defected to the king of England. His brother Llywelyn Fychan had done so back in December 1276, and now he followed suit. Madog was pressured into this decision by Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and William Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, who marched an army down from Chester into Powys Fadog.

Professor J Beverly-Smith states that Dafydd and his English ally ‘tore apart’ the unity of northern Powys. This is a rare mistake by Prof B-Smith, since the lordship had already been divided by Prince Llywelyn in 1270.

The terms of Madog’s submission hint at pre-existing internal divisions inside Powys. Madog was not to reproach or harm those of his tenants who had already gone over to the king. He would in future hold his lands as a tenant-in-chief of the crown, just as his brother Llywelyn had agreed to separate his lands from the principality of Wales. It was further provided that if Prince Llywelyn drove Madog from his lands, the king was obliged to find houses for Madog and his men to live in.

This agreement undermined Prince Llywelyn’s efforts to take direct control of Powys Fadog at the start of the war. In 1278 Madog’s mother, Emma Audley, claimed that Llywelyn had invaded her lands of Overton and Maelor Saesneg “in time of war” and given them to Madog. Llywelyn’s sister Margaret claimed that Llywelyn had invaded her land in Glyndyfrdwy and given it to Gruffydd Fychan, one of Madog’s brothers.

In summary: the Prince of Wales took his sister’s land and gave it to her brother-in-law and took his sister’s mother-in-law’s land and gave it to her son who was also his sister’s brother-in-law and then the two brothers surrendered to the king who divided the lands all over again and gave them to separate people who were all the same people. Sort of. Probably.

Let that be a lesson to you all.

On 12 April 1277 Madog ap Gruffudd, eldest son of Gruffudd of Bromfield, defected to the king of England. His brother Llywelyn Fychan had done so back in December 1276, and now he followed suit. Madog was pressured into this decision by Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and William Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, who marched an army down from Chester into Powys Fadog.

Professor J Beverly-Smith states that Dafydd and his English ally ‘tore apart’ the unity of northern Powys. This is a rare mistake by Prof B-Smith, since the lordship had already been divided by Prince Llywelyn in 1270.

The terms of Madog’s submission hint at pre-existing internal divisions inside Powys. Madog was not to reproach or harm those of his tenants who had already gone over to the king. He would in future hold his lands as a tenant-in-chief of the crown, just as his brother Llywelyn had agreed to separate his lands from the principality of Wales. It was further provided that if Prince Llywelyn drove Madog from his lands, the king was obliged to find houses for Madog and his men to live in.

This agreement undermined Prince Llywelyn’s efforts to take direct control of Powys Fadog at the start of the war. In 1278 Madog’s mother, Emma Audley, claimed that Llywelyn had invaded her lands of Overton and Maelor Saesneg “in time of war” and given them to Madog. Llywelyn’s sister Margaret claimed that Llywelyn had invaded her land in Glyndyfrdwy and given it to Gruffydd Fychan, one of Madog’s brothers.

In summary: the Prince of Wales took his sister’s land and gave it to her brother-in-law and took his sister’s mother-in-law’s land and gave it to her son who was also his sister’s brother-in-law and then the two brothers surrendered to the king who divided the lands all over again and gave them to separate people who were all the same people. Sort of. Probably.

Let that be a lesson to you all.

Published on January 31, 2020 07:12

Awkward arrangements

The Dragon of Chirk (1)

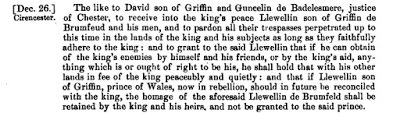

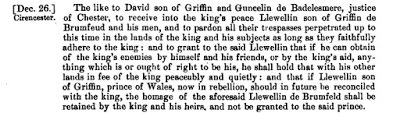

Llywelyn Fychan ap Gruffudd, called the Dragon of Chirk by the poet Llygad Gwr, was one of the sons of Gruffudd ap Madog of Bromfield. When crisis engulfed Wales in 1276, Llywelyn was the first of his brothers to reach an accomodation with Edward I.

The terms of his submission (above) were brokered by Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and Guncelin Badlesmere, justice of Chester. It stipulated that should Llywelyn be reconciled with his namesake, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, his homage would not revert to the Prince of Wales. Instead it would be retained by the king and his heirs, so that Llywelyn’s lands would no longer be part of the principality of Wales.

These unusual terms indicate the depth of Llywelyn’s anger against his prince. It probably stemmed from the division of Powys Fadog in 1270, when Llywelyn’s brother Madog was granted a bigger slice of the territory than himself. Madog was the prince’s brother-in-law and hence more important, so it was unsurprising that he should come first.

The arms of Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd

The arms of Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd

There was also the thorny issue of Castell Dinas Bran. After their father’s death, Llywelyn and Madog had come to an awkward arrangement over possession of the castle. The castle stood inside the northern border of Nanheuwdwy, inside the lands of Llywelyn Fychan. However, it had somehow passed into the hands of Madog, though Llywelyn was allowed to occupy a part of it. This unsatisfactory agreement mirrored conditions in Gascony, where the existence of so many gentry obliged them to share their castles.

Finally, Madog agreed to give his brother Llywelyn the value of the castle in land. This was according to the decision of Prince Dafydd and Peter de Montfort; at this point Dafydd appears to have acted as Prince Llywelyn’s ‘viceroy’ in northern Powys, with jurisdiction over the local princes.

Llywelyn Fychan ap Gruffudd, called the Dragon of Chirk by the poet Llygad Gwr, was one of the sons of Gruffudd ap Madog of Bromfield. When crisis engulfed Wales in 1276, Llywelyn was the first of his brothers to reach an accomodation with Edward I.

The terms of his submission (above) were brokered by Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and Guncelin Badlesmere, justice of Chester. It stipulated that should Llywelyn be reconciled with his namesake, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, his homage would not revert to the Prince of Wales. Instead it would be retained by the king and his heirs, so that Llywelyn’s lands would no longer be part of the principality of Wales.

These unusual terms indicate the depth of Llywelyn’s anger against his prince. It probably stemmed from the division of Powys Fadog in 1270, when Llywelyn’s brother Madog was granted a bigger slice of the territory than himself. Madog was the prince’s brother-in-law and hence more important, so it was unsurprising that he should come first.

The arms of Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd

The arms of Prince Dafydd ap GruffuddThere was also the thorny issue of Castell Dinas Bran. After their father’s death, Llywelyn and Madog had come to an awkward arrangement over possession of the castle. The castle stood inside the northern border of Nanheuwdwy, inside the lands of Llywelyn Fychan. However, it had somehow passed into the hands of Madog, though Llywelyn was allowed to occupy a part of it. This unsatisfactory agreement mirrored conditions in Gascony, where the existence of so many gentry obliged them to share their castles.

Finally, Madog agreed to give his brother Llywelyn the value of the castle in land. This was according to the decision of Prince Dafydd and Peter de Montfort; at this point Dafydd appears to have acted as Prince Llywelyn’s ‘viceroy’ in northern Powys, with jurisdiction over the local princes.

Published on January 31, 2020 01:07