David Pilling's Blog, page 28

May 11, 2020

The League of Franche-Comté (1)

Described as of weak character, spendthrift and debauched (sounds like fun), Otto had little interest in being a count and in 1295 sold Burgundy to Philip IV for a lump sum of 100,000 livres tournois and an annual fee of 10,000 livres in rents. This enabled him to live as Philip's pensioner at the French court, and be as debauched as he pleased with zero responsibility.

When the nobles of Franche-Comté (eastern Burgundy) learned that Otto had flogged his inheritance - and hence their independence - to the king of France, they formed a solemn league and covenant and declared they would never swear homage to Philip or his heirs, or give up their rights to the French crown.

May 10, 2020

A minor and pathetic figure

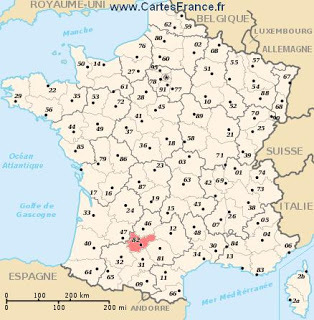

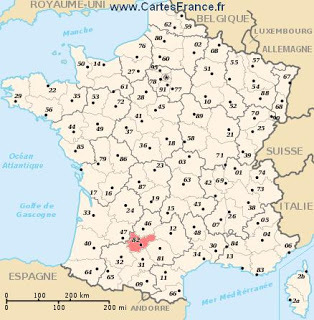

The town hall of Molières, a commune in the Tarn-et-Garrone department in the Occitanie region in southern France.

Between 1286-94 Molières was held by Bertrand de Panissau, a knight of Périgord who also served the Plantagenet king-duke of Gascony as bailiff of Monpazier. When war with France broke out in 1294, Bernard and his family were taken prisoner by the French, only to escape and join the hundreds of Gascon exiles who fled to England.

Bernard, unkindly described as a ‘minor and rather pathetic figure’ by Charles Bémont, petitioned Edward I for compensation in May 1297. To boost his plea, he claimed to have mustered 4000 sergeants in English service service at Roquepine, Molières, Lalinde and Monpazier. He begged the king-duke for the writing-office of the provost of Ste Foy-la-Grande in the Agenais to be granted for life to one of his two sons, both unbeneficed clerks.

Edward declared himself ‘well content’ with Bernard’s service, and waived the need for proof of his claims. He was provided with compensation for his losses and eventually re-granted the bailliwick of Molières until he could recover his lands. Even then, the war had left Bernard so impoverished he would have sunk into destitution without an extra royal grant of 50 livres tournois. This sorely-tried individual vanished from the record in 1308; one of the many middling and lesser Gascon gentry who fell victim to the French occupation of 1294-1303.

The town hall of Molières, a commune in the Tarn-et-Garro...

The town hall of Molières, a commune in the Tarn-et-Garrone department in the Occitanie region in southern France.

Between 1286-94 Molières was held by Bertrand de Panissau, a knight of Périgord who also served the Plantagenet king-duke of Gascony as bailiff of Monpazier. When war with France broke out in 1294, Bernard and his family were taken prisoner by the French, only to escape and join the hundreds of Gascon exiles who fled to England.

Bernard, unkindly described as a ‘minor and rather pathetic figure’ by Charles Bémont, petitioned Edward I for compensation in May 1297. To boost his plea, he claimed to have mustered 4000 sergeants in English service service at Roquepine, Molières, Lalinde and Monpazier. He begged the king-duke for the writing-office of the provost of Ste Foy-la-Grande in the Agenais to be granted for life to one of his two sons, both unbeneficed clerks.

Edward declared himself ‘well content’ with Bernard’s service, and waived the need for proof of his claims. He was provided with compensation for his losses and eventually re-granted the bailliwick of Molières until he could recover his lands. Even then, the war had left Bernard so impoverished he would have sunk into destitution without an extra royal grant of 50 livres tournois. This sorely-tried individual vanished from the record in 1308; one of the many middling and lesser Gascon gentry who fell victim to the French occupation of 1294-1303.

May 1, 2020

No French please, we're Gascons

The news of the battle quickly reached Gascony, where much of the duchy had been under French occupation for eight years. At Bordeaux, the chief city and centre of the wine trade, it inspired the citizens to rise up and drive out the French garrison. Their ringleader was one Arnaud Caillau, who hated the French with a pathological intensity. When his fellow citizens tried to appeal to the king of France, he said to them:

“Why do you appeal from us to the French? We will kill you, and the king of France has so many things to do with the Flemings that he will not help you, and if a war begins and you are appellants, the English king will conquer Normandy and you will gain nothing unless you give up your appeal”.

Once the French were gone, Arnaud turned over Bordeaux to the English. A grateful Edward I made him Mayor of Bordeaux and receiver of the customs of the wine trade. This meant that all the profits passed through his hands, and probably stayed there. Arnaud showed his hatred of the French on other occasions. When confronted by a French lawyer, he tore out the man’s tongue and murdered him on the spot. When a French envoy came to Bordeaux, he made the man stand on a table and then tipped him out of a window, breaking both limbs. This particular Gascon clearly did not see himself as a part of a greater France.

As an aside, the quote above implies that Gascons such as Arnaud thought the English could still reconquer Normandy. This was never on the cards - Henry III, Edward I and Edward II had no ambitions in this vein - but their subjects in Gascony seem to have regarded it as a possibility.

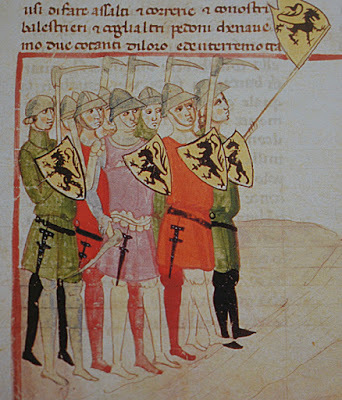

The pic is of Flemish infantry, taken from the Florentine ‘Nuova Cronica’ and uploaded to Wikicommons, public domain.

April 29, 2020

Valour and courage

Arms of Enrique of CastileIn his youth, after a failed plot against Alfonso, Enrique was obliged to seek refuge in England. He arrived in 1256 and was welcomed by Henry III; in return Enrique offered to lead troops to conquer Sicily on Henry’s behalf, but this plan fell through. In 1259 Enrique left England and ended up in Africa, where he took service with the Hafsid Emir of Tunisia, Muhammad al-Mustansir. To the shock of his Christian comrades, Enrique adopted the customs and dress of the Hafsid court. A sort of medieval Laurence of Arabia.

Arms of Enrique of CastileIn his youth, after a failed plot against Alfonso, Enrique was obliged to seek refuge in England. He arrived in 1256 and was welcomed by Henry III; in return Enrique offered to lead troops to conquer Sicily on Henry’s behalf, but this plan fell through. In 1259 Enrique left England and ended up in Africa, where he took service with the Hafsid Emir of Tunisia, Muhammad al-Mustansir. To the shock of his Christian comrades, Enrique adopted the customs and dress of the Hafsid court. A sort of medieval Laurence of Arabia.

Enrique then made his way to Italy, where he fought against Charles of Anjou at the Battle of Tagliacozzo in 1268. He was captured and taken to Apulia in Sicily, where Charles had him exhibited to the public in a cage, loaded down with iron fetters. Outraged Castilian troubadors urged Edward I to secure Charles’s release. One of them, Austorc de Segret, warned the English king that if he failed, he would forfeit the respect of the French:

“Now Edward will need valour and courage if he wants to avenge Henry, who was unparalleled in wisdom and knowledge, and he was the very best of his kin. But if he now stays shamed in this matter, the French over here will leave him neither root nor branch nor well-armed forces, if his worth is stripped of merit”.

The Battle of Tagliacozzo

The Battle of TagliacozzoAnother, Cerverí de Girona, called upon Edward to avenge Don Enrique and make war on his captors. The king preferred diplomacy, and spent the next 23 years lobbying for Charles’s release. At last, in 1291, Charles II of Sicily agreed to let his elderly prisoner go. The charter of release, which is held at the archives of Napoli, states that Charles explicitly agreed to do this at Edward’s request. Enrique’s release came too late for Eleanor, who had died the previous year.

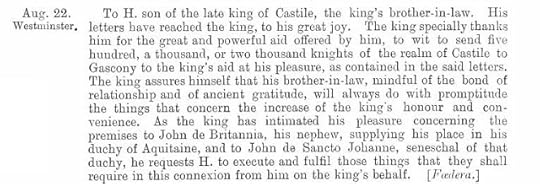

Enrique must have been tough. He had survived decades of brutal imprisonment, and went home to serve as regent of Castile. The old man was suitably appreciative of his rescuer’s efforts: when the Anglo-French war broke out in 1294, he dispatched hundreds of knights of Castile to aid the English.

April 28, 2020

More bribes required

In June 1298 the diplomats of England and France laid their competing claims to Gascony before the pope, Boniface VIII. Philip IV brought against his vassal, Edward I, a charge of treason for having waged open war against him, his liege lord. As a result he demanded Gascony, his vassal’s fief, as a forfeit. The English lawyers responded that Gascony had always been held of the French crown as allod (freehold), not a fief, and that Philip had failed to uphold his side of the feudal contract, as set out by the Treaty of Paris. Therefore he had forfeited his lordship.

Both arguments were bogus. Philip had deliberately provoked war by denying Edward a safe-conduct and breaking his sworn word in council. Equally, there is no proof that Gascony had ever been held as freehold of the French crown. But this was war and politics, and the lawyers on both sides happily lied through their teeth.

Count Guy of Flanders, Edward’s ally, sent a warning to his sons in Rome:

“You should know that the Roman court is very grasping, and that anyone who wants to do business there must make many gifts and promises and pledges.”

In other words, the papacy was corrupt as hell, and if you wanted anything from the pope it was best to turn up loaded with bribes.

Boniface VIIIIt didn’t help that Pope Boniface VIII was one of the most eccentric characters to sit on St Peter’s Chair. At first he welcomed the Flemings, but then changed his attitude. Boniface wanted peace between England and France, and to that end was prepared to sacrifice Flanders.

Boniface VIIIIt didn’t help that Pope Boniface VIII was one of the most eccentric characters to sit on St Peter’s Chair. At first he welcomed the Flemings, but then changed his attitude. Boniface wanted peace between England and France, and to that end was prepared to sacrifice Flanders. Count Guy of Flanders

Count Guy of FlandersThe Flemish envoys went to their English colleagues and asked for help. Edward I’s agents made it clear the English would send no more troops or money to Flanders, but were prepared to try and put diplomatic pressure on Boniface. On 25 June 1298 Guy’s sons and the English envoys had an audience with the pope, in which the head of the English deputation asked for Flanders to be included in the peace. Boniface erupted and declared that he would not risk anything for the sake of Flanders, and that if Count Guy regretted entrusting his affairs to the papacy, he could go take a running jump.

Clearly, more bribes were needed.

April 24, 2020

Two kings, two masters

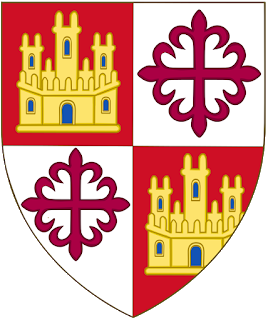

The arms of Armagnac (pre-1304)

The arms of Armagnac (pre-1304)The barons of Navarre appealed to Philip for help, and he sent a French army under Eustace de Beaumarchais to defend Pamplona. Unfortunately the French made themselves unpopular, and in 1276 violence exploded in the city between pro and anti-French factions. This was why Armagnac and his comrades were dispatched to deal with the situation. They laid siege to Pamplona, only for the Navarrese barons to escape at night. This was allegedly due to treachery on the past of Gaston de Béarn, a Gascon nobleman who had previously fought against Henry III and Edward I of England. Gaston was a kinsman to Don Almovarist, one of the barons of Navarre, and so conspired to help the rebels get away. Shortly afterwards Pamplona fell to the French and was sacked with terrible brutality.

An aerial view of PamplonaSix years later, Armagnac was summoned to arms again. This time he was part of the Gascony expeditionary force to North Wales, raised by Edward I to spearhead the invasion of Gwynedd. Armagnac and the other lords of the South were ‘Montagnards’, warlike mountain people, and Snowdonia held no terrors for them:

An aerial view of PamplonaSix years later, Armagnac was summoned to arms again. This time he was part of the Gascony expeditionary force to North Wales, raised by Edward I to spearhead the invasion of Gwynedd. Armagnac and the other lords of the South were ‘Montagnards’, warlike mountain people, and Snowdonia held no terrors for them:“They [the Gascons] remain with the king, receive his gifts,

In moors and mountains they clamber like lions.

They go with the English, burn down the houses,

Throw down the castles, slay the wretches;

They have passed the Marches, and entered into Snowdon”.

Armagnac’s service in Navarre and Wales was a consequence of the Treaty of Paris in 1259. This made the Gascon nobility subject to two masters: the king of England as their immediate lord, and the king of France as overlord. This arrangement enabled both kings to exploit the military resources of Gascony, and meant the likes of Armagnac was a soldier of England and France. His son, Bernard, fought for Philip le Bel in Flanders.

April 20, 2020

Longsword unleashed!

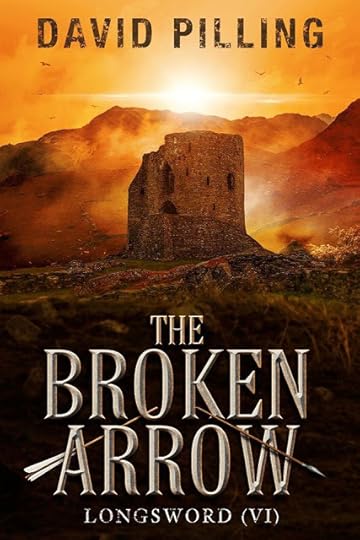

1282 AD.

The fragile peace is about to be shattered. King Edward’s victory over the Welsh and Irish five years earlier was only temporary, and now hostile forces gather again. In Wales the defeated prince, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, plans to claw back his lost power. His turncoat brother, Dafydd, seeks to break free of the king and help the Welsh to recover their liberty. At the same time a fresh revolt breaks out in Ireland.

England itself is threatened. In the northern countries, deep inside Sherwood Forest, the outlaw Robyn Hode conspires to raise the northern barons against the king. He is inspired by the enduring memory of Simon de Montfort, Edward’s old enemy. The northern rebels hope to destroy the king and replace him with Guy, one of Simon’s exiled sons. Robyn sends the broken arrow, a signal of rebellion, to all corners of the kingdom.

Sir Hugh Longsword, the king’s faithful servant, stands between the king and this host of enemies. After sixteen years in royal service, he is determined to finally bring peace to a war-weary land. Yet he must also face the enemy within: Hugh’s rise to royal favour has made him unpopular, and his own master, Robert Burnell, conspires against him. While he fights off the enemies of the state, Hugh must guard against knives in the back.

Longsword VI: The Broken Arrow is the latest historical adventure novel by David Pilling, author of Reiver, Soldier of Fortune, The Half-Hanged Man, Caesar’s Sword and many more novels and short stories. He is also the author of Rebellion Against Henry III: The Disinherited Montfortians 1265-1274, a nonfiction book published by Pen & Sword.

Longsword (VI): The Broken Arrow on Amazon US

Longsword (VI): The Broken Arrow on Amazon UK

April 14, 2020

New Longsword!

1282 AD. The fragile peace is about to be shattered. King Edward’s victory over the Welsh and Irish five years earlier was only temporary, and now hostile forces gather again. In Wales the defeated prince, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, plans to claw back his lost power. His turncoat brother, Dafydd, seeks to break free of the king and help the Welsh to recover their liberty. At the same time a fresh revolt breaks out in Ireland. England itself is threatened.

In the northern countries, deep inside Sherwood Forest, the outlaw Robyn Hode conspires to raise the northern barons against the king. He is inspired by the enduring memory of Simon de Montfort, Edward’s old enemy. The northern rebels hope to destroy the king and replace him with Guy, one of Simon’s exiled sons. Robyn sends the broken arrow, a signal of rebellion, to all corners of the kingdom.

Sir Hugh Longsword, the king’s faithful servant, stands between the king and this host of enemies. After sixteen years in royal service, he is determined to finally bring peace to a war-weary land. Yet he must also face the enemy within: Hugh’s rise to royal favour has made him unpopular, and his own master, Robert Burnell, conspires against him. While he fights off the enemies of the state, Hugh must guard against knives in the back.

Longsword VI: The Broken Arrow is the latest historical adventure novel by David Pilling, author of Reiver, Soldier of Fortune, The Half-Hanged Man, Caesar’s Sword and many more novels and short stories. He is also the author of Rebellion Against Henry III: The Disinherited Montfortians 1265-1274, a nonfiction book published by Pen & Sword.

Longsword (VI): The Broken Arrow on Amazon US

Longsword (VI): The Broken Arrow on Amazon UK

April 13, 2020

Half and half

The bastide was founded by Henry III in 1260, shortly after the Treaty of Paris (1259) which established the duchy of Aquitaine - otherwise known as Guienne or Gascony - as a fiefdom held by the Angevin kings as vassals of the Capetian kings of France. This awkward arrangement gave rise to a host of problems, not least tenurial rights. Castillones was shared between the Angevins and the Capets, and the frontier of the border district of the Agenais ran right through the middle of the town: effectively this meant that subjects of the English crown lived in one half, subjects of the French in the other.

The problem was finally resolved in the peace of 1303, whereby Philip IV restored Gascony to Edward I and permitted the Anglo-Gascons to have Castillones all to themselves.