David Pilling's Blog, page 26

June 18, 2020

Each and every thing...

New blog...

The ruins of Castell y Bere in the heart of Meirionydd, North Wales On 25 April 1283 the defenders of Castell y Bere in the heart of North Wales surrendered to the armies of Edward I. In exchange for handing over the castle, they received about two-thirds of a promised bribe of £80 in silver: the shortfall might have rankled, but they were probably just relieved to get away with life and limb.

The ruins of Castell y Bere in the heart of Meirionydd, North Wales On 25 April 1283 the defenders of Castell y Bere in the heart of North Wales surrendered to the armies of Edward I. In exchange for handing over the castle, they received about two-thirds of a promised bribe of £80 in silver: the shortfall might have rankled, but they were probably just relieved to get away with life and limb.The fall of Bere was an important step in the Edwardian conquest of Wales. Seen from other perspectives, it was one of the final acts in a very long-running drama. Among the royal commanders were Rhys ap Maredudd, lord of Ystrad Tywi in south Wales, and several of the sons of Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys. These men chose to fight for the King of England against the Prince of Wales because the latter, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, was their hereditary enemy.

The conflict between the lords of southern Powys (Powys Gwenwynwyn) and Prince Llywelyn's family went back over two hundred years. Their ancestor, Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, had once ruled Gwynedd and Powys in the mid-eleventh century, including the site of Castell y Bere inside Meirionydd. Bleddyn lost Gwynedd to the ancestors of Llywelyn, and a feud had rumbled on ever since. At times the lords of Powys joined with their ancestral foes against the English, but they were uneasy allies. Gruffudd had been Llywelyn's ally for a time, only to conspire with his brother Dafydd to murder the prince in his bed.

That plot had failed, but in December 1282 Llywelyn fell victim to another. The Chronicle of Peterborough Abbey claims that Gruffudd and his sons were present at the death, and it is difficult to believe they were not complicit in luring Llywelyn to his doom. After his death, the crown of Wales passed to his treacherous brother Dafydd, who continued to resist Edward's invasion. This meant that the former conspirators, Gruffudd and Dafydd, were now on opposite sides.

It seems Edward was well aware of the feuds between rival dynasties in Wales, and the value of symbolism. When Bere fell, the castle was handed over to one of Gruffudd's sons – ironically named Llywelyn – and a force of Powysian soldiers. The lions of Gwynedd were torn down from the battlements and replaced with the red lion rampant of Powys Gwenwynwyn:

The symbolic significance, and the irony, of his custody of the castle built by his grandfather's great enemy, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, in the heart of the land that had long ago been held by members of his dynasty, cannot have been lost on Llywelyn or his father. The revenge of the house of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn was complete. (David Stephenson)

In the spring and summer months of 1283 the war devolved into a man-hunt. After the loss of his castles, Dafydd and his remaining followers scattered and went on the run. The payroll for this campaign shows the men of Powys were heavily involved in hunting down the fugitive prince. For instance:

Item, payment to William de Felton and David ap Griffin ap Wenonwin, with 2 covered horses, for themselves and 140 foot-soldiers returning with them to Cymer from the parts of Powys, seeking David ap Griffin, for Saturday 22 May, for 1 day, 26s 6d.

And:

Item, to the same William and David ap Griff’ ap Wenonwin, with 2 covered horses, for themselves and 200 foot-soldiers going towards the parts of Powys, for Tuesday 18 May, the Wednesday, Thursday and Friday following, for 4 days, each day counted, £7 8s, to pursue David ap Griffin.

These payments indicate Dafydd was thought to be hiding somewhere in Powys, perhaps on the lands of one of his late brother's followers, Llywelyn Fychan of Bromfield. He was eventually caught on 22 June on the Bera mountain in Gwynedd, by 'men of his own tongue'; possibly men of Gwynedd, or perhaps of Powys and Ystrad Tywi.

In the final days of the war, on 28 June, Gruffudd and his Marcher ally Edmund Mortimer were ordered to clear all the passes under their control of trees. This was because one of Dafydd's sons, Llywelyn, was lurking with 'certain thieves' inside the woods; the last dregs of resistance. Gruffudd and Edmund's men soon flushed them out and delivered Llywelyn into royal custody. His fate was to spend the rest of his days as a prisoner at Bristol Castle with his younger brother, Owain.

A few years later Gruffudd died in his bed at Welshpool, aged about 65. He had been entirely successful:

It was thus, with the territorial extent of his lordship largely restored and in one region extended significantly beyond the territories that he had entered in 1242, with his principal rivals eliminated and his erstwhile persecutor, Prince Llywelyn, dead and his house all but destroyed, that Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn died in 1286. (David Stephenson)

June 17, 2020

Men of his own tongue

On 25 April 1283 the defenders of Castell y Bere in the heart of North Wales surrendered to the armies of Edward I. In exchange for handing over the castle, they received about two-thirds of a promised bribe of £80 in silver: the shortfall might have rankled, but they were probably just relieved to get away with life and limb.

Castell y Bere

Castell y BereThe fall of Bere was an important step in the Edwardian conquest of Wales. Seen from other perspectives, it was one of the final acts in a very long-running drama. Among the royal commanders were Rhys ap Maredudd, lord of Ystrad Tywi in south Wales, and several of the sons of Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys. These men chose to fight for the King of England against the Prince of Wales because the latter, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, was their hereditary enemy.

The conflict between the lords of southern Powys (Powys Gwenwynwyn) and Prince Llywelyn's family went back over two hundred years. Their ancestor, Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, had once ruled Gwynedd and Powys in the mid-eleventh century, including the site of Castell y Bere inside Meirionydd. Bleddyn lost Gwynedd to the ancestors of Llywelyn, and a feud had rumbled on ever since. At times the lords of Powys joined with their ancestral foes against the English, but they were uneasy allies. Gruffudd had been Llywelyn's ally for a time, only to conspire with his brother Dafydd to murder the prince in his bed.

That plot had failed, but in December 1282 Llywelyn fell victim to another. The Chronicle of Peterborough Abbey claims that Gruffudd and his sons were present at the death, and it is difficult to believe they were not complicit in luring Llywelyn to his doom. After his death, the crown of Wales passed to his treacherous brother Dafydd, who continued to resist Edward's invasion. This meant that the former conspirators, Gruffudd and Dafydd, were now on opposite sides.

It seems Edward was well aware of the feuds between rival dynasties in Wales, and the value of symbolism. When Bere fell, the castle was handed over to one of Gruffudd's sons – ironically named Llywelyn – and a force of Powysian soldiers. The lions of Gwynedd were torn down from the battlements and replaced with the red lion rampant of Powys Gwenwynwyn:

The symbolic significance, and the irony, of his custody of the castle built by his grandfather's great enemy, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, in the heart of the land that had long ago been held by members of his dynasty, cannot have been lost on Llywelyn or his father. The revenge of the house of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn was complete. (David Stephenson)

In the spring and summer months of 1283 the war devolved into a man-hunt. After the loss of his castles, Dafydd and his remaining followers scattered and went on the run. The payroll for this campaign shows the men of Powys were heavily involved in hunting down the fugitive prince. For instance:

Item, payment to William de Felton and David ap Griffin ap Wenonwin, with 2 covered horses, for themselves and 140 foot-soldiers returning with them to Cymer from the parts of Powys, seeking David ap Griffin, for Saturday 22 May, for 1 day, 26s 6d.

And:

Item, to the same William and David ap Griff’ ap Wenonwin, with 2 covered horses, for themselves and 200 foot-soldiers going towards the parts of Powys, for Tuesday 18 May, the Wednesday, Thursday and Friday following, for 4 days, each day counted, £7 8s, to pursue David ap Griffin.

These payments indicate Dafydd was thought to be hiding somewhere in Powys, perhaps on the lands of one of his late brother's followers, Llywelyn Fychan of Bromfield. He was eventually caught on 22 June on the Bera mountain in Gwynedd, by 'men of his own tongue'; possibly men of Gwynedd, or perhaps of Powys and Ystrad Tywi.

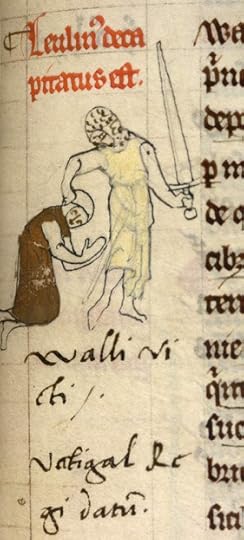

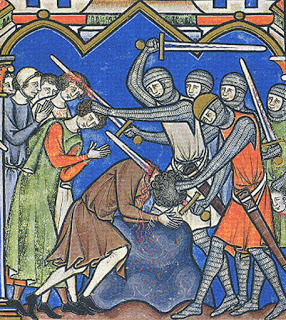

The killing of Prince Llywelyn

The killing of Prince LlywelynIn the final days of the war, on 28 June, Gruffudd and his Marcher ally Edmund Mortimer were ordered to clear all the passes under their control of trees. This was because one of Dafydd's sons, Llywelyn, was lurking with 'certain thieves' inside the woods; the last dregs of resistance. Gruffudd and Edmund's men soon flushed them out and delivered Llywelyn into royal custody. His fate was to spend the rest of his days as a prisoner at Bristol Castle with his younger brother, Owain.

A few years later Gruffudd died in his bed at Welshpool, aged about 65. He had been entirely successful:

It was thus, with the territorial extent of his lordship largely restored and in one region extended significantly beyond the territories that he had entered in 1242, with his principal rivals eliminated and his erstwhile persecutor, Prince Llywelyn, dead and his house all but destroyed, that Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn died in 1286. (David Stephenson)

June 12, 2020

Split open to the teeth

In the summer of 1296, while Edward I launched his invasion of Scotland, a number of similar conflicts raged in the Iberian kingdoms south of the Pyrenees. One particular war, the invasion of Murcia by Jaume II of Aragon, shows how monarchs of this era would seize upon the weakness of their neighbours to seize power and territory.

At first King Jaume (reigned 1291-1327) was on friendly terms with the kingdom of Castile, but later intrigued to depose the boy-king, Fernando IV, and to divide Castile-Léon among Fernando's kinsman. The civil war that ensued left Jaume with a free hand to invade the province of Murcia in south-east Spain.

Jaume II presiding over his court

Jaume II presiding over his court

Murcia had once been part of the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba , only to be captured during the Reconquista in the 1240s. In the early years of his reign, Jaume had agreed to a division of Murcia with Aragon, but in 1296 he tore up the agreement and launched a full-scale invasion. Distracted by their internal divisions, the Castilians could do nothing to stop him.

The progress of Jaume's invasion is vividly recorded by Roman Muntáner, a Catalan mercenary and writer who would later lead a 'Free Company' to help the Eastern Romans fight the Turks (before promptly changing sides and helping the Turks fight the Eastern Romans). In July 1296, even while John Balliol was being stripped of his empty coat in Scotland, the armies of Aragon swept over the borders into Murcia and laid siege to the town and castle of Alicante.

The castle should have been a tough nut to crack. The Castillo de Santa Bárbara (pictured) was a mighty fortress perched on the heights of Mount Benacantil. Originally a Moorish stronghold, it had been captured by Castilian forces in 1248, who named it after the feast day of St Bárbara.

Fortunately for Jaume, it was in poor repair. According to Muntáner, the king led his knights on foot up the slopes of the mountain to attack the castle gates. They found part of the wall had fallen in, and attempted to storm the breach. Jaume was almost killed when one of the defenders, a 'big and brave' knight, hurled a hunting spear at him. It penetrated the first quarter of the king's shield, more than half a palm's length, but stopped short. Jaume rushed at his attacker and gave him such a blow the king's sword carved through the cap of mail and split him open to the teeth. Jaume then pulled his blade free, attacked another knight and lopped off his entire arm and shoulder. It seems Jaume was no less fearsome in a fight than the likes of Richard Marshal, Saint Louis et al.

The knights of Aragon poured through the breach and made short work of the defenders. Jaume himself killed five more men, and no mercy was shown to the 'alcaide' or Christian constable of the garrison. This man, En Nicholas Peris, defended himself stoutly with sword in one hand and a bunch of keys in the other. Muntáner remarks that his defence was of little use, since he was cut to pieces. Afterwards Jaume ordered that the corpse was not to be given Christian burial, but instead thrown to the dogs as a traitor.

Muntáner uses the alcaide's dire fate as a lesson to other men who wish to betray their lords:

“Wherefore, Lords, you who shall hear this book, be careful when you hold a castle for a lord. The first thing he who is holding a castle for a lord should have at heart, should be to save the castle for his lord; the other, to leave it only with honour for himself and his descendants...for in one day and one night that happens which no man imagined could happen.”

The rest of Jaume's campaign was little more than a military promenade, as one town and castle after another fell without offering much resistance. After the city of Murcia itself had fallen, Jaume installed garrisons and appointed his brother, En Jaime Pedro, as governor or procurator of the newly conquered territory.

Jaume's lightning campaign and apparently easy victory were as deceptive as Edward's triumph in Scotland. His success relied on the turmoil in Castile, and when Fernando gained his majority Jaume's position was weakened. In 1304 he entered into renewed negotiations with Castile over the division of Murcia, which ended in the agreement of Torrellas on 8 August. Most of Murcia was restored to the Castilians, with the exception of Alicante, Eliche and Orihuela, and the territory north of the river Segura. Jaume's allies in Castile were also forced to renounce their claims to the throne.

Not to worry, though. Once the matter of Murcia was settled, Jaume and Fernando joined forces to carve up the Islamic kingdom of Granada. And so it went on.

June 9, 2020

'For the glory of your cause...'

The Anglo-French war between Edward I and Philip IV was a mightily confusing affair. After several years of bloody stalemate in Aquitaine (south-west France) both kings decided to widen the conflict into northern Europe. They set about spending vast reservoirs of cash on recruiting allies in the Low Countries, Scotland, Norway and the Holy Roman Empire: both kings intended to use these alliances as part of a strategy of encirclement to stretch each other’s military capacity to breaking point. In practice they simply cancelled each other out.

It didn’t help that many of their allies took the money on offer and ran, or used it for their own purposes. Adolf of Nassau, one of Edward’s allies and King of the Romans, used his English funds to wage two private wars in Thuringia in east-central Germany. By doing so he earned Edward’s undying wrath and the hatred of his own people, which ended very badly for him (perhaps the subject of another blog post).

Edward got better service from another set of allies in Adolf’s territory. These were a league of nobles in Franche-Comté, now eastern Burgundy in France. Edward had some bitter memories of this region. In 1274, on his way back from the Holy Land, he was invited to take part in a tournament in Franche-Comté. The local bigwig, the Comte d’Auxerre, had really lured Edward into a trap with the intention of capturing the English king and holding him to ransom. The plan backfired when Edward threw the count from his horse and ordered his infantry to slaughter the Burgundian knights:

“He said to his men, "Spare no-one you set eyes on now, and do the same to them as they are doing to us." So they began killing the other side, savagely attacking them everywhere with the sword. The men on foot had retreated from the slaughter of their fellows when they saw many of their people fall, but boldly joined the combat of the mounted men; they gutted many of the horses and cut their girths, so that their riders fell to the ground.” (Henry of Knighton)

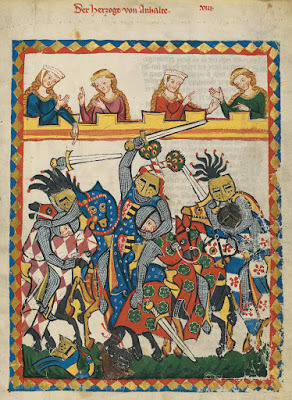

A contemporary German depiction of a tournament

A contemporary German depiction of a tournamentOver twenty years later, in 1297, Edward hired these same nobles to fight for him against Philip. Led by Jean de Arlay, a kinsman of the man humiliated by Edward in 1274, they agreed to serve for a payment of 60,000 livres tournois for the first year of the alliance, with 30,000 in each subsequent year

Unlike many of the so-called Grand Alliance, the Burgundians actually went into action. Jean and his followers had vested interests in doing so. At this time Franche-Comté was still part of the empire, which made them vassals of King Adolf. Philip wanted to conquer the region, and to that end had bought out Count Othon IV of Burgundy, a feckless character who was quite happy to sell his inheritance for a comfortable life at the French court. When the barons of Franche-Comté heard of the deal, they swore an oath never to surrender their lands and ancient rights to the French king.

In the spring of 1297 the Burgundians met Adolf at Koblenz, where he gave them money and promised to send German troops to aid them before 22 July. Despite his thunderous public denouncements of Philip, Adolf failed to deliver on any of his promises. The French didn’t take him seriously at all. Charles of Valois, Philip’s brother, is said to have sent Adolf a letter containing just two words - ‘Troupe Almande’, which translates as ‘Too German’ or even ‘Stupid German’.

King Edward finally landed in Flanders on 23 August. The campaign that followed was a mess and a muddle, if not quite the total fiasco often depicted. After several weeks of farcical manoeuvres and vicious brawling between Flemish and Welsh infantry, the allies started to get themselves in gear. On 6 October they stormed Damme, the port town of Bruges and the most direct route to the Channel. Two days later Edward received a triumphant message from Jean de Arlay:

“Most dear sire, this is to inform you, that on Tuesday, the eve of the feast of Saint Denis, myself and my companions of Burgundy captured and razed the castle of Ornans, which was held by Burgundy of the King of France and was the strongest castle in the whole of Burgundy. And know that, I and my other comrades broke down the walls of the castle and forced our way inside, and secured the castle, and took nine prisoners and a great quantity…put a large number to the sword, apart from those who threw themselves down below the rock…”

The remains of the castle of Ornans

The remains of the castle of OrnansOrnans, a dramatic fortress perched upon an outcrop, was the birthplace of Jean’s bitter enemy, Count Othon. Some of the defenders, poor souls, hurled themselves off the high precipice overlooking the valley. Afterwards the town and castle were looted and burnt, and Jean wrote a second letter promising to join Edward in Flanders, ‘for the glory of your cause’.

The English king had also received a note from two more of his allies, the counts of Bar and Savoy. They were gathering troops on the eastern borders of France and would also ride to join him. At this point Edward might have been tempted to continue the war. His chief ally, Count Guy of Flanders, begged him to carry on. The rains would soon come, Guy pointed out, and force the French to retreat.

Edward had a difficult choice to make. By now he had received word of the revolt in Scotland, where his northern army under Earl Warenne had been smashed at Stirling Bridge. The Scots under William Wallace had invaded and ravaged the northern counties. Edward did not trust his lieutenants to deal with the mess, but neither did he wish to completely abandon the war against France.

He compromised. In March 1298, from his new base at Aardenburg near the Zeeland border, Edward renewed his contract with the Burgundians. The said nobles agreed to ‘make and continue lively and open war’ against the French until a final peace was made. In return they would be paid another 30,000 livres tournois on top of the 60,000 they had already been paid, to be handed over in two instalments in June and December.

A few days later Edward set sail for home. While he mounted an enormous military operation to defeat Wallace, the Burgundians continued to harry the French. They destroyed more castles in Franche-Comté, including Clairvaux and the ‘hall’ or palace of Pontarlier. At one point they captured the bailiff of Mâcon, Count Othon’s lieutenant, and locked him up with other French prisoners in the castle of Roulans. The Burgundians were still active in September 1299, when Philip engaged a local knight, Geoffrey d’Aucelles, to defend his town of Gray against the rebels and deliver them to the king if they fell into his hands. Philip’s particular enemy, Jean de Arlay, was named as one of the targets.

A final peace was struck in 1301. By this point the Grand Alliance had collapsed into dust, and the rival kings had buried the hatchet. This left Jean de Arlay and his associates with little choice but to sue for peace. Philip was merciful. Instead of destroying the Burgundians he offered to pardon them all, if they swore homage and agreed to pay for the damage they had committed during the war. This was a bitter deal, since it meant Franche-Comté would become part of a greater France. Philip sugared the pill by offering to make Jean constable of the Franche-Comté. Jean accepted, and another piece of the tottering German empire was swallowed up.

June 7, 2020

Bruce and the king

On the anniversary of the death of Robert de Bruce, King of Scots, in 1329, I thought it would be interesting to look at his relationship with Edward I of England.

What was Bruce’s attitude towards the would-be conqueror of Scotland? Bruce’s private opinion is a mystery, of course, but circumstances dictated his behaviour. There were many other factors at work. Bruce was not too proud - or too patriotic either - to make use of the English king when it suited him. Edward in turn appreciated Bruce’s value as an ally, and the shock of the latter’s final revolt may well have hastened the old king’s death.

To begin with, the Bruce faction were thoroughly on board with Edward’s Scottish project. They rode with the king when he invaded Scotland in 1296, which led to accusations of treachery from Scottish writers. As Walter Bower later put it:

"All the supporters of Bruce’s party were generally considered traitors to the king and kingdom…”

Just like anyone else, the Bruces were out for themselves. They supported Edward in the hope that he would depose John Balliol and put a Bruce on the Scottish throne: Bruce’s father, the sixth earl of Carrick. Balliol was duly dethroned and sent off to captivity in England, but Bruce senior’s tentative reminder met with a stern brush-off from the king:

“Have we nothing else to do than win kingdoms for you?”

Edward had no reason to fear the earl: he had always obeyed the king, and served him faithfully in Wales and Ireland. Bruce junior was made of sterner stuff, even if he took a while to show it. When Andrew Moray and William Wallace raised their standard in 1297, Bruce and other nobles threw in their lot with the ‘rebels’. In July they promptly threw in the towel before Edward’s captains, only to be shown up by Moray and Wallace’s stunning victory at Stirling Bridge in September.

The news of Stirling Bridge inspired Bruce to go back into revolt. When Edward came north again in 1298 - ‘a great black storm of rage’- as one writer put it - Bruce remained a Scottish loyalist. After his victory at Falkirk, Edward turned west and rushed over to Ayr to try and catch Bruce in his stronghold. He found his quarry long gone, vanished into the hills, and the town and castle in flames.

Bruce’s eyes were firmly fixed on the empty throne. He knew that Wallace would not survive as Guardian much longer, and that the rival Comyn faction was planning to take over. Bruce could not allow that to happen, but ended up sharing power with his chief rival, John ‘the red’ Comyn of Badenoch. This uneasy alliance ended in a fight, in which Comyn is said to have seized Bruce warmly by the throat. More bad news arrived from France, where John Balliol was now in papal custody. For a few awful months it looked as though Balliol might return to Scotland at the head of a French army.

This was an equally horrifying prospect for Edward, which meant he and Bruce now had shared interests. In early 1302 Bruce turned himself in at Lochmaben and surrendered to the king’s keeper of Galloway, John de St John. For the next four years he was Edward’s man, at least on the surface. We can only speculate, but it would seem that Bruce meant to use Edward to crush the opposition in Scotland, before breaking loose to claim the throne. Therefore his aim was to achieve a free and independent Scotland, but only with himself as king.

This, at any rate, is what happened. In 1304, when Edward launched his final all-out effort at conquest, Bruce played a key role. He was with the Irish when they landed on the western seaboard, and supplied the king with artillery for the siege of Stirling. Edward seems to have regarded Bruce as his best boy at this point, and sent him a letter applauding his efforts:

“For if you complete that there which you have begun, we shall hold the war ended by your deed, and all the land of Scotland gained. So we pray you again, as much as we can, that whereas the robe is well made, you will be pleased to make the hood.”

Contemporary MS illustration of Edward I

Contemporary MS illustration of Edward IBruce’s long-term goal was in sight. Edward was an old man in poor health, albeit with an irritating tendency to rally. Even as English war-machines pounded the walls of Stirling, Bruce was arranging his future. On 11 June he met secretly with the Bishop of St Andrews at the abbey of Cambuskenneth, where they finalised a treaty of mutual aid. The treaty did not state as much, but the implication is that Scotland’s most senior churchman had agreed to support Bruce’s bid for the throne.

Yet the time was not ripe. Edward was not ready to keel over just yet, and in February 1305 Bruce attended parliament at Westminster to advise on the Ordinance for Scotland’s new government. This was a surprisingly conciliatory effort on Edward’s part to include the Scottish magnates in his administration: Bruce, now thirty years old and in the prime of life, was rewarded with the revenues of the earldom of Mar.

No amount of gifts and compromise would conceal the hard fact that Edward was once again overlord - ‘Lord Paramount’ - of Scotland, and that he called the shots. Bruce bided his time, perhaps encouraged by the increasing frailty of England’s king. Of more concern was the growing power and influence of the Comyns in Scotland. Since he gave up the guardianship, the Comyns had come to dominate affairs north of the border, which presented Bruce with another problem. Edward had defeated John Comyn, or at least persuaded him to submit, but (most annoyingly) allowed the man to live. Indeed, the Comyns had flourished since: most of the Scottish delegates to London, chosen at Perth or Scone in May 1305, were of their faction.

This was no good at all. Bruce had to change tack, and the result was the famous meeting at a church in Dumfries on 10 February 1306. Here, John Comyn and his uncle were done to death by Bruce and his followers in an almost certainly pre-meditated double homicide. After the bloody deed was done, Bruce went into open revolt.

The news of the crime, when it reached Edward, was almost too shocking to believe. At first Edward had no idea who was responsible. When he found out, according to John Barbour, the king temporarily lost his reason:

“And when King Edward was told how the Bruce, who was so bold, had ended the life of the Comyn, and then had made himself King, he nearly went out of his mind.”

The rest is well-known. Edward spent the remaining months of his life attempting to catch ‘King Hobbe’ (as he termed Bruce) from a sickbed. At first Bruce suffered a string of defeats, but emerged from hiding in the spring of 1307 to harry Edward’s forces. The dying king executed every male Bruce he could lay his hands on, and shut up the women in solitary confinement, but his chief quarry always remained beyond reach. In the end Edward was striking at a mirror of himself:

“A crowned warrior, careless of men’s lives, who meant to have his way at any price.”

The mirror finally crack’d for Edward on 7 July 1307, at a bleak outpost in the Cumbrian marshes. King Hobbe still had a long war ahead of him, with no guarantee of success, but the first hurdle was overcome.

The magic foot of Saint Simon

In late 1266, while Henry III was struggling to put down rebels in East Anglia, a fresh revolt blew up in distant Northumbria. Unable to go himself, Henry sent his heir the Lord Edward to deal with the rising.

Alnwick Castle

Alnwick CastleThe ringleader was John de Vescy, lord of Alnwick. Vescy had been one of Simon de Montfort’s phalanx of bachelor knights, who followed him about like a latter-day Praetorian Guard. At the bloodbath of Evesham in 1265, where Montfort was hacked to pieces, Vescy managed to escape with one of his beloved master’s severed feet. He returned to his northern fastness and donated the foot to a local priory. The grisly object was placed inside a silver shoe, of all things, and worshipped as a relic with magic healing properties. It was noted that this ‘foot of incorruption’ exhibited a wound, either made by a hatchet or a sword.

Vescy entered into a pact with certain other northern barons. According to the chronicler Thomas Wykes, they swore that each would adhere to the other and thus, being reliant on mutual aid, restore their lands seized by the king. In reality Vescy’s followers may have not had much choice in the matter. It is possible to trace at least two of them, Henry de Bilton and William de Lisle, both tenants on the Vescy estates. As such they were obliged to obey their lord and offer him ‘mutual aid’, whether or not they wanted to.

He may have recruited some allies from north of the border. The Meaux Chronicler in East Yorkshire mentions Scots among the Alnwick garrison. This seems inexplicable, as England and Scotland were not at war at this time. Perhaps Vescy hired a few wandering Scottish mercenaries; alternatively, the Yorkshire-based chronicler was unable to tell the difference between Northumbrians and Scotsmen!

Edward raced north to contain the revolt. A true son of the Devil’s Brood, he marched with the same breathless speed as Henry FitzEmpress or the Lionheart: one of his followers, Richard Clifford, recalled in later years the prince’s army marching ‘day and night continuously with horses and arms’. On the way he raised the militia of the northern counties, a ‘large multitude of fighters’, and then pressed on towards Alnwick.

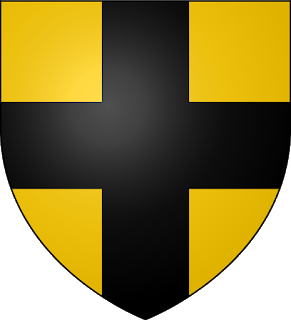

The arms of John de Vescy

The arms of John de VescyVescy chose to retreat inside his stronghold. The usual tactic was to throw a garrison inside a castle and remain outside with a flying column to try and break the siege lines, but Vescy found himself bottled up inside four walls. Perhaps Edward moved too quickly for him. Few details survive of the siege that followed, except for the curious tale of William Douglas and Gilbert Umfraville, Earl of Angus.

While the siege was in progress, Edward was approached by Angus. The earl accused Sir William Douglas, known as Longleg for his height, of being a traitor. Angus asked Edward to confiscate Douglas’s manor at Fawdon and give it to him: it just so happened that Douglas was one of the earl’s tenants.

Edward agreed, provided Douglas was convicted by a jury. At the trial, held at Boulton in Northumberland, the accused was cleared of all charges. The enraged earl sent his retainers to seize Douglas’s goods at Fawdon. When the court ordered him to give them back, Angus went a step further. He and his lieutenant, John Hirlawe, raised a hundred riders of Redesdale, for centuries a notorious den of thieves, and set them on Douglas and his family. William and his wife and children were dragged about from place to place, tortured with fire, and his son William junior sliced through the neck with a sword. He survived and was known afterwards, appropriately enough, as William le Hardi (the Hardy).

A Border Reiver in silhouette

A Border Reiver in silhouetteA second trial was held in October, where Angus denied all the above. He seemed in remarkably good humour, and asked the jurors when all of this was supposed to have taken place. When they gave him a date - 19 July - he smiled and pointed out ‘there were many days in a week’. The jurors lost their bottle and acquitted Angus of his misdeeds. Poor old Douglas was found guilty of false accusation and sentenced to a brief term in prison.

None of this was any help to John de Vescy. In the summer of 1267 he surrendered to Edward, who pardoned the lord of Alnwick and his followers. How the castle fell is something of a mystery. John Fordun, writing decades later, states that Edward took it by stealth. Perhaps he had a spy among the garrison, as he did in Hampshire and other rebel headquarters. The northerners expected to be punished, and the prince’s mercy took them by surprise. Edward took the sting out of the revolt by permitting the rebels to recover their lands, though for a price. John de Vescy later had to find 3700 marks, borrowed from an Italian creditor, to redeem his lordship.

This brief northern revolt is a footnote in the story of the Montfortian wars, but contains much of interest. Students of the Border Reivers may be intrigued to find the lancers of Redesdale, a notorious ‘riding surname’ of the Tudor era, very much alive and kicking several hundred years earlier. It seems you can’t keep good men down, or bad ones either.

June 6, 2020

Blood on the palace floor

Most people - history bods, anyway - have heard of Robert de Bruce’s murderous assault upon his rival John Comyn in a church at Dumfries in 1306. Not so many know of a (roughly) similar incident that occured several decades earlier, in the very presence of the King of England at Westminster.

The link between the two incidents is John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey. Warenne is best-known as the defeated English general at Stirling Bridge in 1297, although he had a long and eventful career before that date. In the 1260s he played an important role in the suppression of the Disinherited rebels in England; his brutal efficiency in this respect inspired one historian to dub Earl Warenne the ‘big stick’ of royal policy, employed to crush naysayers.

In a world of violent and grasping magnates, Warenne was unusually belligerent. The Hundred Rolls, a monumental record of local government corruption, record the oppressive treatment of the tenants on his vast estates. He terrorized the people on his manors in Yorkshire, and in Sussex indulged in a vicious private war against Sir Robert Aguillon, who had risen high in the favour of Henry III. Much of this was run-of-the mill baronial nastiness, but in 1268 Warenne went a step too far.

Earl Warenne's home of Lewes Castle

Earl Warenne's home of Lewes CastleAt this point Henry’s heir, the Lord Edward, was trying to recruit nobles to accompany him to the Holy Land. Many of the English barons preferred to concentrate on their private feuds than embark on the risky voyage. This was especially true of Warenne and Henry de Lacy, the young Earl of Lincoln. These two entered into a petty row over some pasture land, which threatened to flare up into civil war when both men started to raise troops. The crisis fizzled out, but the restless Warenne got into another row with Alan de la Zouche.

It was the usual scuffle over competing land rights, but this time Warenne decided to settle the affair personally. When the two men appeared before the king, in the crowded hall of Westminster, Warenne ripped out his sword and attacked Alan and his son. He then cut his way out of the hall, seized a horse from the royal stables and galloped off to his castle at Reigate. The injured men were left lying in a pool of blood, no doubt while shocked gasps echoed among the ancient rafters and Henry had apoplexy. Or perhaps he didn’t. He had been forty years in this game, after all, and men of violence doing awful things in front of him was nothing new.

Even so, Warenne could not be allowed to simply get away with it. The king dispatched Edward in hot pursuit, and the prince quickly surrounded Reigate with an army. Edward took the initiative in negotiating the terms of Warenne’s surrender, which was considered an offence to the royal dignity. Hardly surprising, since it had taken place in the presence of the king and his sons.

Stirling Bridge

Stirling BridgeThe earl’s punishment was severe. He was ordered to pay a fine of 10,000 marks and a barefoot walk of penance from Temple to Westminster. The fine was eventually relaxed: he only paid 1850 marks of it before his death in 1304, with 6800 still outstanding. He was helped by his friends in high places, including Henry of Almaine and Gilbert de Clare, who closed ranks and swore the assault on Zouche was not premeditated. Warenne’s victim lasted long enough for Warenne to make his peace with the crown on 4 August, only to die six days later. His son Roger, who had also suffered Warenne’s murderous wrath, survived and inherited his father’s estates.

The blow to Warenne’s prestige and future freedom of action was severe, however. He remained under a cloud during the reign of Edward I, who made regular use of financial penalties as a ‘carrot and stick’ tactic of controlling his nobility. His grandfather King John had adopted a similar policy, except John used it as a means of destroying his nobles: Edward preferred to re-assimilate them, on the understanding that he could release the Sword of Damocles at any time.

June 1, 2020

She-bears

On 15 May 1266 (I’m late, as usual), the Disinherited barons under Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby, suffered a bad defeat at Chesterfield in Derbyshire. It was more of an ambush than a pitched battle, in which the rebels were attacked as they lay in camp outside the town. Some of them were even confident enough to go off hunting in the woods, and were thus taken completely by surprise.

The royalist army was led by Henry of Almaine, Henry III’s nephew, and his lieutenants Earl Warenne and Warin of Basingbourne. Warin was the chap who raised his helm at the battle of Evesham and delivered a speech to the royalist knights, just as they were on the point of breaking:

“Again, traitors again,

And remember how vilely ye were brought to the

ground at Lewes,

Turn again,

And think that the power is now all ours,

And we shall,

As if they were nought,

Overcome them to a certainty.”

Earl Ferrers was a sickly fellow. He had inherited the family curse of gout, and on the day of battle was lying flat on his back in his pavilion, having his blood let. This was a common remedy for gout, though one imagines the treatment was worse than the malady. His comrades Sir John de Eyvill, Henry Hastings and Baldwin Wake had led the hunting party into the forest, to chase after deer with spear and bow.

A pleasant time was being had by all, then, but not for long. As soon as word of the northern conspiracy reached London, Henry of Almaine had raced north to deal with the threat. Whatever their faults, all the Angevins could move at speed when they wanted to, and his army arrived near Chesterfield at dusk after a forced march.

The royalists attacked at once. Ferrers’s men scattered, while the earl himself fled into Chesterfield - trailing blood and stained bandages - and took refuge in a church. The only serious resistance came from John de Eyvill and his fellows, who stormed back from the woods and hurled themselves at the enemy. John was knocked off his horse by a royalist knight, Gilbert Haunsard, but climbed aboard a spare:

“With a lance he brought a knight at the first onset down;

Yet he broke through the host, and wounded many a one.”

John and his comrades saw the battle was lost, and fled back into the forest. They made their way back to the Isle of Axholme, an impregnable hideout deep inside the dreary fens of Lincolnshire:

“The Deyvill escaped, bold and valiant,

Into the Isle of Axholme, where he was before.”

There was no such escape for Earl Ferrers. Not exactly a born hero, he was eventually found hiding under a pile of woolsacks in the church. His position was given away by a young woman of Chesterfield, whose lover Ferrers had allegedly hanged outside the town gates. He was packed off to prison at Windsor, where he spent the next three years cooling his heels in (probably quite comfortable) captivity. His men weren’t so lucky. At least one of the earl’s knights, Henry Ireton, was killed in the fight outside Chesterfield. Another, Robert de Wollerton, was taken and hanged on Sheene hillside. The rest scattered into the wilds of Sherwood and the High Peak, where they gathered in sullen bands and plotted revenge:

“They collected in bands in the woods, which were suitable hiding-places, and made hide-outs in various places. They were more dangerous to meet than she-bears robbed of their cubs and seized everything they wanted from anywhere.”

- the Bury chronicler

Thus England continued to slide into ruin and chaos. As the Scottish chronicler, Walter Bower, put it - nowhere was there peace, nowhere security.

May 30, 2020

Mercy and ferocity

The future Edward I of England had an unpromising start to his career. He was surprisingly malleable, torn between loyalty to his father, Henry III, and the rebel barons led by Simon de Montfort. At one point he was suspected of conspiring to depose the king, and his habit of oath-breaking was satirised in a Montfortian ballad, The Song of Lewes:

“He is a lion by his pride and ferocity; by his inconstantly and changeableness he is a pard, not holding steadily his word or his promise, and excusing himself with fair words.”

The nadir of the young Edward’s fortunes came at the Battle of Lewes in 1264, when his undisciplined pursuit of the Londoners lost the battle for his father. He spent a year in humiliating captivity, which gave Edward much time to ponder his mistakes. In the summer of 1265 he broke free and staged a dramatic coup that ended in the bloody slaughter of Evesham. The massacre of Earl Simon and his followers saddled Edward with fresh problems, as he was now the target of a blood-feud.

When the revolt of the Disinherited broke out, Edward was among the first to seize forfeit land and money. He wasn’t quite as rapacious as his colleague Earl Gilbert de Clare, the ‘red dog’ of Gloucester, but certainly grabbed his share. Among other lands, Edward seized the manor of Luton, once in the possession of Henry de Montfort. Henry had been cut in half by a broadsword at Evesham, and Edward wept at his funeral. He managed to wipe away his tears before taking possession of Luton just four days later.

Over the winter months of 1265, Edward came to realise two things. First, the sheer folly of the policy of disinheritance, which left half the landed class of England destitute and with no option except to fight. Second, the pressing need to reconstruct his reputation in the public eye. A prince who was perceived as faithless, one who waged war on his own people, was never going to enjoy popular support.

The first sign of his changed attitude was at Axholme in Lincolnshire, where Edward laid siege to a nest of rebel barons holed up in the dreary fens. When they eventually surrendered, he spared their lives on condition they stood trial at London. Predictably, every one of the barons broke their oath and went back into rebellion.

Edward showed the same clemency in further military operations. After he stormed the rebel-held town of Winchelsea, he spared the townsfolk on condition they abandoned their lives of piracy. As a result of his mercy, ‘great tranquillity was spread over that sea’. Nor was there any question of disinheritance. Instead the barons of the port towns were permitted to have their lands, houses and chattels, as well as ancient liberties guaranteed by the king and his predecessors.

A few months later Edward defeated the outlaw knight, Adam Gurdon, and let him live: this clemency was not extended to Adam’s peasant followers, who were hanged on the trees of Alton forest. In 1267 Edward raced north to crush the revolt of John de Vescy in Northumbria, and spared the ringleaders after he stormed their base at Alnwick Castle. John had carried the severed foot of Simon de Montfort back to Alnwick and kept it inside a silver shoe; it was said to have magic healing properties, but proved unable to repel swords and arrows.

This policy had the desired effect. Edward’s reputation soared among English chroniclers. In place of the devious ‘Leopard’ of earlier years, he was now ‘a gallant knight who should be king hereafter’; the king’s ‘renowned first-born son’; one ‘whose mercy is always inestimable and universal’.

Edward arguably took mercy too far. He pardoned a dangerous pirate, Henry Pethun, and an outlaw named Walter Devyas. These men showed their gratitude by immediately reverting to lives of crime. Henry Pethun vanished on the high seas, never to be seen again, but Walter was finally caught on the Scottish border and beheaded for his many arsons, robberies and murders.

All of this is virtually unrecognisable from the Longshanks of popular imagination: the ruthless tyrant who brutally executed William Wallace and harried the Welsh and the Scots without mercy. The truth is that the gallant knight and the brutal conqueror existed in the same man. Much of the success of Edward’s reign was due to the calculated mercy he showed after Evesham. Men who had surrendered to him, such as Adam Gurdon and John de Vescy, served him loyally in the Welsh and Scottish wars. The king’s peculiar mixture of ferocity and mercifulness was expressed in The Song of Caerlaverock, composed in 1300:

“For none experience his bite

Who are not envenomed by it.

But he is soon revised

With sweet good-naturedness

If they seek his friendship

And wish to come to his peace”.

The castle of Sauveterre-la-Lemánce in the Agenais, a region of Aquitaine

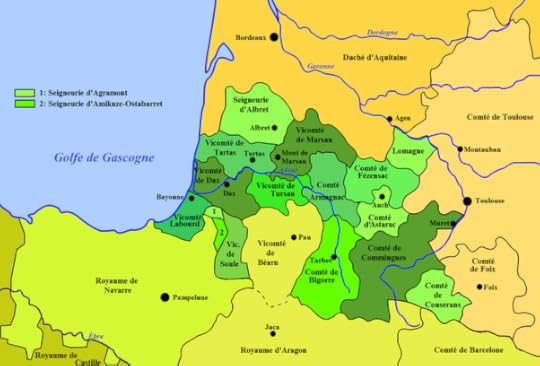

The castle of Sauveterre-la-Lemánce in the Agenais, a region of Aquitaine  The duchy of Aquitaine/Gascony The period of Edward I of England's personal rule of Aquitaine (also known as Gascony or Guienne) from 1273-94 was the most effective and forceful the duchy had ever known under an Angevin king, or would know again. Edward's actions in Aquitaine have been largely forgotten:

The duchy of Aquitaine/Gascony The period of Edward I of England's personal rule of Aquitaine (also known as Gascony or Guienne) from 1273-94 was the most effective and forceful the duchy had ever known under an Angevin king, or would know again. Edward's actions in Aquitaine have been largely forgotten: