David Pilling's Blog, page 25

June 30, 2020

The old seed of malice (3)

At the end of 1275, Eleanor and Amaury de Montfort were captured at sea by privateers in the service of Edward I, on their way to join Prince Llywelyn of Wales. Among those captured with them were two Dominican friars, said to be noblemen of Welsh birth. The king ordered Robert Kildwardby, Archbishop of Canterbury, to carefully question these men since the 'stratagems and schemes ' of the Montforts were said to have been due to their planning and ingenuity.

One of the Dominicans was Friar Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, a grandson of Ednyfed Fychan, once the distain or seneschal to Prince Llywelyn ap Iorwerth. This much is revealed by a letter (pictured above) sent by Roger Mortimer of Wigmore to the king in May 1277. Roger reported that the Welsh position in the Marches, as well as Powys Wenwynwyn and Powys Fadog, had collapsed under severe pressure from English forces. He also informed the king that several important Welsh noblemen were ready to desert Prince Llywelyn's cause.

These men were Rhys ap Gruffudd and his kinsmen Gruffydd ab Iorwerth and Hywel ap Goronwy. Rhys was one of Friar Llywelyn's brothers, and the friar was acting as intermediary to secure the defection of his kinsmen. After initially supporting the Montforts, it appears that Friar Llywelyn had been persuaded to switch his allegiance and help to undermine the position of the Prince of Wales on Edward's behalf. This was presumably after he and his fellow Dominican had been questioned by the Archbishop of Canterbury on their involvement in the plot against the king.

This glut of defections was particularly concerning to Prince Llywelyn, since these men had once been his closest confidants. Rhys ap Gruffudd had served as one of the prince's ministers, and they were all of the illustrious lineage of Ednyfed Fychan. Such men were expected to stick by their prince until the bitter end: this was their customary function. Instead they chose to abandon him.

Exactly why they abandoned Llywelyn, at such a moment of crisis, is unclear. They may have expected more rewards from the prince, though Rhys had been granted the land of Dinsylwy Rys to add to his estates in North Wales. The defection of such powerful and respected men had serious repercussions: if men from the upper echelons of society abandoned the prince, the communities under their lordship were likely to follow suit. In this context the defection of Friar Llywelyn and the lineage of Ednyfed Fychan in the crux years of 1276-77 provide an insight into problems facing Prince Llywelyn, and how he could not rely on the loyalty of his chief servants.

Published on June 30, 2020 06:23

June 29, 2020

The old seed of malice (2)

Corfe Castle In 1275 Prince Llywelyn of Wales decided to honour his commitment to marry Eleanor de Montfort, daughter of Earl Simon. They had been probably been betrothed in 1265, when Eleanor's father agreed terms with Llywelyn at Pipton. Simon was killed shortly afterwards at Evesham, but Eleanor's mother, the Countess Eleanor, stayed in touch with Llywelyn from her exile in France.

Corfe Castle In 1275 Prince Llywelyn of Wales decided to honour his commitment to marry Eleanor de Montfort, daughter of Earl Simon. They had been probably been betrothed in 1265, when Eleanor's father agreed terms with Llywelyn at Pipton. Simon was killed shortly afterwards at Evesham, but Eleanor's mother, the Countess Eleanor, stayed in touch with Llywelyn from her exile in France. King Edward was perfectly aware of their communication, and did his best to stop it. On 11 September Llywelyn wrote to Pope Gregory, informing him that he found it difficult to contact the papal court, since Edward's fleet kept watch on the seas. In spite of the danger, at the end of 1275 Eleanor and her brother Amaury set sail from France for North Wales.

Their ship was intercepted in the Bristol Channel by a Cornish knight, Thomas Larchdeacon, a privateer in royal service. According to a letter Edward sent to the pope, the Montfort banner was discovered under the boards of the ship, along with a cache of weapons. Edward didn't need to use this as an excuse to seize the Montfort siblings: he had specifically forbidden Amaury from entering the kingdom in 1273, along with the exiled Montfortian bishop of Chichester.

The king suspected the Montforts of wishing to ally with Llywelyn so they could begin another civil war in England. Edward made these suspicions clear in a furious letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury in early 1276:

'We do not believe that you have forgotten how Simon de Montfort and all his family fought with all their strength against King Henry, our father, and ourselves and our men...Eleanor, his daughter, following the counsel of her relatives and friends, of whom there are many in our kingdom, arranged to marry the prince of Wales, believing, though wrongly, that through a marriage to the prince she could, by his power, spread abroad against us in the fullness of time the old seed of malice which her father had conceived, and which she could not spread about on her own.

But divine providence, which is infallible in its disposition, returned her to us unexpectedly, confounded by her own error...we are justly angered against her and her fellow conspirators, and no less against two brothers of the Dominican order, noblemen of Welsh birth, found and held in her company, since the said stratagems and schemes are said to have been due to their planning and ingenuity...since we do not believe that this marriage was contracted without the convenience and consultation of many people, we ask as a particular favour that you in your wisdom carefully question the said brothers about this.'

Eleanor was held in captivity at Windsor for the next three years, while Amaury was imprisoned at the royal stronghold of Corfe Castle in Dorset. The king's treatment of Amaury was in direct contravention of clause 39 of the Great Charter, which stated that no man could be held in prison without trial:

"No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land."

So far as Edward was concerned, clause 39 of the Great Charter could take a running jump. He loathed the charter anyway and wasn't about to observe niceties towards people he regarded as enemies and traitors. Amaury had defended the murderers of Henry of Almaine; he had defied a royal mandate (twice) and tried to enter the realm; he had conspired with Edward's enemies; he had joined forces with an exiled prelate. The man was extremely lucky to be alive: if not for Edward's desire to end the blood-feud with the Montforts, he might have gone the same way as Prince Dafydd and William Wallace.

As it was, Amaury languished at Corfe, where he composed verses complaining bitterly of his ill-treatment. There was much sympathy for him, and both the English papacy and the papacy tried to persuade the king to let Amaury go. The bishops asked for him to be released into their custody, but Edward refused unless they could guarantee that Amaury would pose no threat to the kingdom or the church.

Amaury's lot was eased in 1277 thanks to Edward's defeat of Prince Llywelyn. The king now felt secure enough to hand Amaury over to the bishops, though he was still a captive. In 1278 Edward relented further and allowed Eleanor's marriage to Llywelyn to go ahead. The happy couple sent frequent letters to the king, begging him in eloquent terms to release Amaury. Llywelyn privately contacted the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Pecham, and asked if he might send a servant to speak with Amaury. Pecham agreed in principle, but expressed his concern with the danger involved and the king's attitude if he found out. Amaury's fate was discussed in stormy Parliament sessions and church assemblies at the New Temple.

Ironically, Edward finally agree to release Amaury in April 1282, a few weeks after Prince Dafydd's attack on Hawarden on Palm Sunday triggered another war in Wales. The king's decision might seem odd, but it could be that Amaury's presence in England threatened to complicate matters. He was required to swear an oath never to set foot in the kingdom, and then permitted to depart. We may be certain that Edward's servants accompanied him every step on the way to the coast.

Published on June 29, 2020 03:13

June 28, 2020

The old seed of malice (1)

The murder of Henry of Almaine On 13 March 1272 Henry of Almaine, nephew of Henry III and cousin to Edward I, was murdered in a church at Orvieto and Italy by Simon and Guy de Montfort. This was a revenge killing for the gruesome fate of their father, the famous Earl Simon, at the slaughter of Evesham in 1265. It was also the latest episode in the bloody feud between the Montforts and the ruling Plantagenet dynasty of England.

The murder of Henry of Almaine On 13 March 1272 Henry of Almaine, nephew of Henry III and cousin to Edward I, was murdered in a church at Orvieto and Italy by Simon and Guy de Montfort. This was a revenge killing for the gruesome fate of their father, the famous Earl Simon, at the slaughter of Evesham in 1265. It was also the latest episode in the bloody feud between the Montforts and the ruling Plantagenet dynasty of England. A few months later King Henry died, worn out by a lifetime of attempting to govern the ungovernable, and was succeeded by Edward. The new king was in the Holy Land and would not set foot on English soil again until August 1274. He had previously attempted to extend an olive branch to the Montfort clan, but after the murder of his cousin any such efforts at rapprochement were forgotten.

Edward's sights were fixed on Amaury de Montfort, the third of Earl Simon's sons, and his sister Eleanor. Amaury, a clerk in holy orders, had played no role in the killing of Edward's cousin, but had attempted to defend his brothers before Pope Gregory at Orvieto. Gregory firmly rejected his arguments, so Amaury changed tactics and joined forces with Stephen Bersted, the Montfortian bishop of Chichester, who had been exiled to France. In 1273, while in Gascony, Edward was informed that these two were trying to get into England. His angry response was to strictly forbid the bishop's entry and confiscate his lands in England. A royal galley was fitted out to patrol the Channel and prevent Amaury and Bersted crossing into England.

The king went even further, and paid one Richard Spaniel, a sergeant of the Dover garrison, 20 shillings to go to Paris and 'lay a snare' for Amaury and the bishop. They avoided the trap, but from now on their movements were closely watched. Edward's specific fear was that the Montforts would make an ally of Prince Llywelyn of Wales, who had sworn to marry Earl Simon's daughter Eleanor. This was not mere paranoia: England was still in a dismal state after years of civil war, and fresh conflicts threatened to erupt at any time. In the summer of 1274, shortly before Edward's return, a conspiracy was hatched against him in the northern counties. It was only suppressed by the prompt action of his brother Edmund, and Roger Mortimer of Wigmore:

"In the meantime, some persons in England, kindling with envy and rage, thirsting for money which did not belong them, and prophesying of their own hearts, affirmed that Edward would never return to England. These men, wishing to make sure of future events, collected in the northern provinces three hundred armed men, without counting infantry and light-armed cavalry; but they were pursued by some noble and powerful knights, namely Edmund, brother of the King of England, and Roger de Mortimer, with a large company of armed men. And when the confederate rebels heard this, their league was dissolved, and they returned to their own homes, without attempting further achievement." (Flores Historiarum)

It is unclear who exactly lay behind this short-lived northern revolt. Edward's old enemy Robert de Ferrers might have been involved, but his actions were confined to Staffordshire. The reasons for Amaury's desire to get into England in 1273 have never been properly explored, and it may well be that he had entered into a secret plot with disgruntled Montfortians in England. The regency goverment was on red alert: rumours of fresh rebellions in Leicestershire and Cambridge swirled about Westminster, and orders went out to set watch on the Isle of Ely and sink all the boats in the district.

The new king's first task, when he finally came home in August 1274, was to settle all these disturbances. Amaury, for his part, was determined to ignore Edward's mandate and get into the British Isles. Tensions continued to rise, in England and along the Marches of Wales. At last, in late 1275, Amaury took the plunge.

Published on June 28, 2020 01:52

June 26, 2020

The great jigsaw

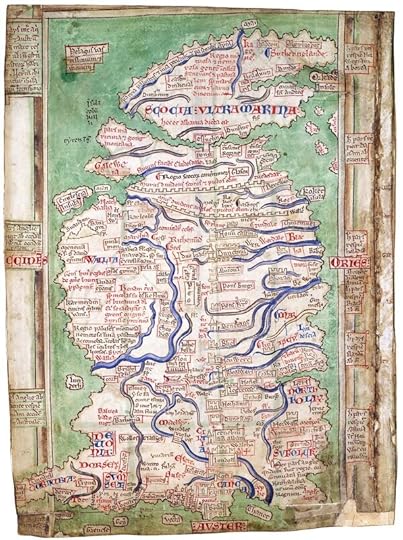

A map of medieval Britain by Matthew Paris In June 1296 Edward I was roving about north-east Scotland beyond the Forth, securing castles and taking the submissions of Scottish lords. A lengthy journal entry, drawn up by one of his clerks, describes the king's movements in mid-June:

A map of medieval Britain by Matthew Paris In June 1296 Edward I was roving about north-east Scotland beyond the Forth, securing castles and taking the submissions of Scottish lords. A lengthy journal entry, drawn up by one of his clerks, describes the king's movements in mid-June:"On the Monday he went to Kincleven castle, on the Tuesday to Cluny castle, and there abode five days; the Monday after to Inverqueich castle; on the Tuesday to Forfar, a castle and a good town, on the Friday after to Fernwell..."

Etcetera. This journal, written by a man with the prose style of wet cement, gives the impression that Edward sauntered about Scotland with a cigar in his mouth, meeting virtually no resistance: more of a holiday excursion than a campaign. This impression has been reinforced by certain historians, both to downgrade Edward's military skill and emphasise the feebleness of the Scottish defence in 1296. The typical narrative then rushes on to the hero-tale of William Wallace and Andrew Moray.

Everyone likes a good narrative (it's so much easier), but few wars in this era were straightforward military promenades. The task of any commander was to shatter enemy morale via terror tactics and attrition: destroy the enemy's subsistence, waste the land, decimate the peasantry. So it was in 1296, when Edward unleashed his Welsh and Irish levies to cow the Scots into surrender:

"The Irish and Welsh were summoned and came in great numbers to help the king. They poured over the face like locusts. They bound tightly with thongs or killed anyone who resisted them."

- the Bury Chronicler

Admittedly, this image of 'locust'-like efficiency is somewhat undermined by surviving plea rolls. These suggest that Edward's infantry were more interested in fighting each other than conquering and enslaving the foe. There were savage brawls between Welsh and English soldiers at Edinburgh, Roxburgh and elsewhere, most probably driven by racial animosity. There had been a major revolt in Wales in 1294-5, which Edward had raised large numbers of men in England to suppress. Grudges were bound to linger: indeed, many of the Welshmen who served the king in Scotland and Flanders must have been in arms against him only a few years earlier.

If Edward struck hard, it was not merely due to his personal savagery. He had been trying to enforce his lordship over Scotland for years, but the game had altered by 1296. After shunting aside his puppet king, John Balliol, the Scottish council had forged an alliance with Edward's chief enemy, Philippe le Bel. This made Scotland a part of the great jigsaw of alliances and counter-alliances both kings were constructing against each other. When the Scots ratified the treaty with France, on 23 February 1296, the gloves came off.

The English king was under pressure. Philippe was attempting to lure away his expensive allies, with some success. In January 1296 the Count of Holland deserted Edward and walked into the French camp; another ally, Count Guy of Flanders, was forced to beg for peace after Philippe kidnapped his daughter. The politics of the era were dirty and lethal, and both kings were quite prepared to stoop to low tactics to undermine each other. The count of Holland was murdered later in the year, stabbed to death by Edward's Dutch confederates. Guy's daughter Philippine was incarcerated for the rest of her days to prevent her marrying Edward's son, the future Edward II.

The Scottish war of 1296 should be set in the context of this febrile atmosphere, with much of Western Europe drawn into a conflict between the two greatest powers. Edward's concern was to knock out the Balliol Scots as quickly as possible, then turn about and rush over to the Continent to lead his allies against the French. This, I suggest, is the explanation for his contemptous dismissal of Scotland to Earl Warenne:

"Bon besoigne fait qy merde se delivrer."

(A man does good business when he rids himself of a turd)

Had he been inclined to think about it, Edward might have redefined Philippe and the French as the real turd in his lunchbox. The Scots, by contrast, were simply getting in the way. Edward didn't know it, but they would continue to do so for the next 250 years until the two kingdoms were finally united under a share Protestantism.

Published on June 26, 2020 00:28

June 25, 2020

Rolling in feathers

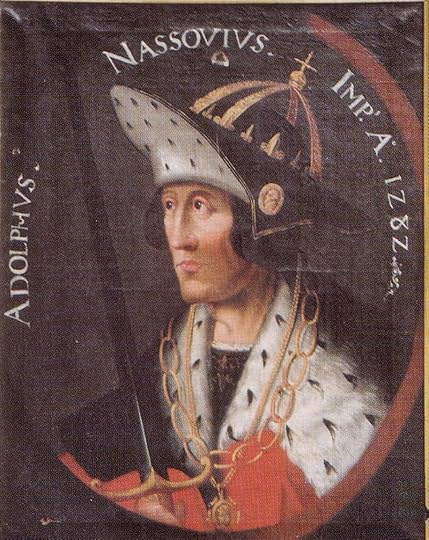

Adolf of Nassau, King of the Romans In the mid-1290s a series of wars raged all over Western Europe. Edward I's invasion of Scotland tends to hog the headlines - at least in the British Isles - but it was really part of a much wider interrelated conflict.

Adolf of Nassau, King of the Romans In the mid-1290s a series of wars raged all over Western Europe. Edward I's invasion of Scotland tends to hog the headlines - at least in the British Isles - but it was really part of a much wider interrelated conflict. The match that lit the powder that blew the keg was Philippe le Bel's invasion of Edward's duchy of Aquitaine two years previously: in the aftermath both kings began to feverishly recruit allies, apparently in an effort to encircle each other at the same time. Edward copied the strategy of his grandfather, King John, and focused on building up a confederation among the princes of the Low Countries and the Holy Roman Empire. In response Philip worked on enlisting allies in Burgundy, Norway and Scotland.

One of Edward's most important allies was Adolf of Nassau, King of the Romans and technically the Holy Roman Emperor (though he was never formally crowned by the pope). Adolf already had a grudge against Philippe, who had designs on certain outlying districts of the empire. A desultory war had been raging in eastern Burgundy, and in 1294 Adolf was all too happy to take Edward's money to fight the French.

The English paid over enormous sums. By October 1294 Adolf had received £20,000 of English sterling, with another instalment of the same amount paid over by Christmas. Edward was supposed to sail to the Continent in September, but was distracted by a major revolt in Wales. While his paymaster suppressed the Welsh, Adolf used Edward's money to launch an invasion of Thuringia in east-central Germany.

Adolf's aim was to expand his power base inside the empire. He had only been elected because he was relatively poor and weak, and could not prevent the powerful Electors from doing as he wished. By using English money to bring a significant chunk of the empire under his direct control, Adolf could aspire to be king in deed as well as in name.

His invasion of Thuringia over the winter of 1294/5 was bloody and brutal, and did nothing to endear Adolf's subjects to their ruler. One German chronicle describes it in vivid terms:

"In the same year Adolf, king of the Romans, by mainforce entered into Thuringia in the month of September, carrying out there many evils, defiling virgins, laying waste to churches, robbing, oppressing and killing innocent and just men, and perpetrating several other things contrary to the rule of justice..."

Adolf's solders behaved with eccentric cruelty: apart from the atrocities listed above, they were said to have seized a couple of defenceless widows, smeared them in pitch mixed with grease, then rolled them in feathers. When informed of this, Adolf remarked that the women were guilty of no crime, but otherwise was indifferent to their fate. They returned home, the chronicler says, having 'gained no grace'.

When the campaign was over, Adolf spent more of Edward's money on hiring support in Germany: a sum of £1000, for instance, was paid to Count Johann von Sponheim for his 'welcome services'. The German king then had the insouciance to write to Edward and inform him of his truimph in Thuringia, achieved thanks to English gold:

"...see now how we may bring joy to you, because, in entire fulfilment of our vows, and by the strength of the victorious army which we recently created, with the Lord of Hosts our helper, we have added the provinces of Thuringia, Osterland and Meissen to our dominion and empire..."

These glad tidings were unlikely to have brought Edward much joy, and Adolf had exaggerated his success. The people of Thuringia were not conquered, and in the autumn of 1295 Adolf was obliged to launch a second invasion of the province. Once again he used English money to do so, and by now Adolf's subjects were tired of his antics. One German chronicler, Ellenhard, accused the king of keeping the money to himself instead of distributing it among his nobles. Another, Mattias of Nuremburg, complained that Adolf did not use English money to buy armaments to fight the French, but to purchase Meissen.

Adolf was on dangerous ground. Not only had he knifed Edward in the back - not a good idea, as Prince Dafydd of Wales could have warned him - but his wars in Germany had alienated his subjects. A reckoning was on the horizon, in the shape of a Welsh assassin and a one-eyed Austrian duke.

Published on June 25, 2020 03:58

June 22, 2020

June 22nd, 2020

Today is the anniversary of the capture of Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales, on the Bera mountain inside Gwynedd in 1283. This post takes a look at events in the months leading up to his final defeat at the hands of Edward I.

Today is the anniversary of the capture of Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales, on the Bera mountain inside Gwynedd in 1283. This post takes a look at events in the months leading up to his final defeat at the hands of Edward I.

Dafydd became prince in December 1282, after his predecessor Prince Llywelyn was lured into an ambush and killed by the Marcher lords. There is no proof that Edward was involved in the killing, and his closest advisers briefly feared the Marchers would come after the king next. In the dark confusion of the days after Llywelyn's death, the newly crowned Prince Dafydd sent his wife Eleanor to the king. Her task was to plead for mercy and bring an end to the war.

Eleanor was an unfortunate choice of envoy. She was the sister of Robert de Ferrers, Edward's old enemy, and the king was in no mood to compromise. Threatened by the Marchers, sunk deep in debt to Italian financiers, he was determined to crush the House of Gwynedd once and for all. The barons of his council had made Dafydd an offer of peace back in November 1282, on condition he went to the Holy Land. Dafydd gave the following proud rebuttal:

"When he wishes to visit the Holy Land, he will do so voluntarily and by pledge to God, not to man. He is therefore reluctant to give pilgrimage to God, because he knows forced service is displeasing to God."

The proud defiance of November had shrivelled away by January, but events were already in motion. In the west, Edward's uncle William de Valence summoned his knights once more to ‘ride afresh upon the enemies of the lord king’. On 9 January he and Robert Tibetot set out at the head of some forty heavy cavalry and over sixteen hundred infantry to face the Welsh gathered in force at Llanbadarn on the coastline of northern Ceredigion. They were led by the diehards Gruffudd and Cynan ap Maredudd and their neighbour Rhys Maelgwn. These men had fought and squabbled with each other in the past, but were now united in a futile last stand.

Whatever took place at Llanbadarn - a battle, negotiation or surrender - the result was clear enough. By 26 January Cynan and Rhys had been captured and were on their way to the king at Rhuddlan, guarded by a strong escort. Gruffydd escaped and made his way to Snowdonia to join Dafydd. Edward must have had some choice words for the prisoners when they were brought before him, but Cynan and Rhys were not killed or imprisoned. Instead they were put on royal wages and sent back west to serve in Valence’s army. They spent the remainder of the war patrolling Llanbadarn at the head of small bands of horse and foot.

This marked the end of the campaign in the west. In March, after a break in operations, King Edward was ready to move again.

In early March the noose tightened further around Prince Dafydd. The king himself led one army to occupy Conwy and begin the construction of the massive new castle between 11 and 13 March. On the 14 he ordered those forces serving under William Valence in West Wales to be ready to set out for Meirionydd by 2 May. Simultaneously the army at Bangor under Othon Grandson and John Vescy began to push southwards, supported by the navy of the Cinque Ports.

The Welsh stronghold at Criccieth, where Prince Llywelyn had once imprisoned the lords of Ystrad Tywi, had already fallen by 14 March. It was probably taken by a division of the royal army sent on from Dolwyddelan by the old road through the mountains, and from the 14 one of the king’s officers, Henry Greenford, started to draw wages as constable. There is no evidence of a siege, and it seems the Welsh garrison fired the castle and withdrew. A sum of £200 was spent on repairs at Criccieth in the following months. The castle was also home to a large store of wine, possibly Llywelyn’s private stash, which was sent on to the king.

William Valence worked quickly to bring up his army up from the west. By 13 April he had gathered a force of 688 infantry and 9 constables at Aberystwyth, drawn mainly from Kidwelly, Cemais and Cilgerran. Just two days later Valence arrived before the walls of Castell y Bere, Dafydd’s stronghold in Meirionydd. Valence had been joined by Rhys ap Maredudd, and their combined army swelled to 961 infantry, 15 constables and some light horse.

Castell y Bere lies near Afon Dysinni, south of the massive range of Cader Idris mountains. Today it lies in ruin, but in 1282 the castle presented a formidable obstacle, surrounded by marshes and only approachable via narrow pathways. Prince Dafydd himself refused to be trapped in the castle and was somewhere in the hills nearby at the head of his horsemen. This was standard tactics for the day. There was no point allowing oneself to be bottled up inside a castle, so a commander would usually leave the garrison to defend the stronghold while he remained outside the walls at the head of a flying column of cavalry.

Against the numerical might of Edward’s war machine, Prince Dafydd could only retreat further into his mountains. His garrison at Castell y Bere was left isolated, surrounded by the king’s forces. Valence and Rhys were soon joined by another army led by Roger Lestrange, lord of Knockin on the Welsh March, at the head of 2000 infantry. These were raised from his and John Lestrange’s lands at Knockin and Montgomery, and the lands of Peter Corbet of Caus and Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys. Their reinforcements brought the army up to over 3000 strong. Lestrange had been present at the death of Llywelyn in December, and now brought his men north to stamp on the last embers of resistance.

There was no dramatic last stand at Bere. On 22 April, after a week’s siege, the garrison agreed to surrender on terms. Valence and Lestrange promised to pay over the sum of £80 in silver, in return for which Kenewreg ap Madog, the constable, and his associates delivered up the castle. It was duly surrendered on 25 April, and Kenewerg and his men allowed to go free. Only two-thirds of their promised bribe was paid over.

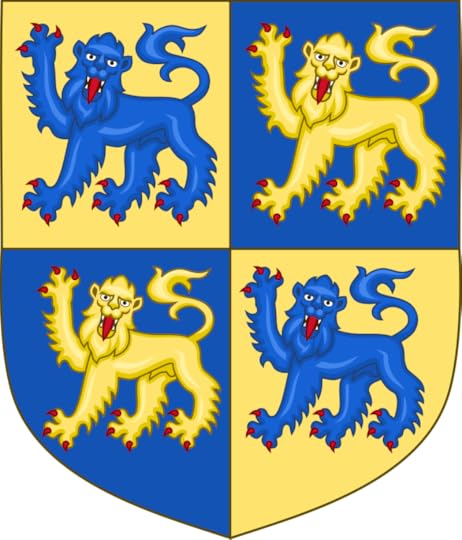

Bere was given into the custody of Lewis de la Pole, one of the sons of Gruffudd ap Gwenwynyn. Like Rhys ap Maredudd, Gruffudd and his family probably viewed this war as the final chapter in an ancient dynastic struggle against Gwynedd. Now the houses of Dinefwr and Mathrafal had finally truimphed over the House of Aberffraw. The real victor was Edward Plantagenet.

It was only a matter of time before Dafydd was taken. On 2 May he was at Llanberis, deep inside Snowdonia, where he made a last-ditch attempt to summon men to fight for him. Dafydd issued a charter granting the cantref of Penwedding in northern Ceredigion to Rhys Maelgwn if he would raise troops against the king. Penweddig was in the hands of Gruffudd ap Maredudd, who graciously yielded possession. Apart from Gruffudd, Dafydd’s council at Llanberis consisted of Hywel ap Rhys Gryg, Rhys Wyndod, Llywelyn ap Rhys, Morgan ap Maredudd and the prince’s steward, Goronwy ap Heilyn.

None of these men were aware that Rhys Maelgwn had joined the king’s army. There is something tragic and farcical about Dafydd’s last days as Prince of Wales, sat in his half-empty stronghold in the mountains, surrounded by a handful of diehard councillors issuing futile charters to men who had already deserted him. On 14 May the king was at Dolwyddelan, which meant the royal army was just ten miles (as the crow flies) from Dafydd’s last redoubt at Dolbadarn.

Bands of soldiers were sent out in all directions to hunt down Dafydd and his followers, who led them a merry chase for several weeks. A number of Welshmen laid down their arms and joined in the hunt; the prince was sought not only in Gwynedd but much further afield, in Powys and the marches, the lands of Gruffudd ap Maredudd in Ceredigion and Rhys Wyndod in Ystrad Tywi. The search was gradually narrowed down to the lands of North Wales, Ardudwy and Penllyn and the mountains of Snowdonia.

Finally, on about 22 June, Dafydd was brought to bay at Llanberis, at the very foot of Snowdon. He was captured by ‘men of his own tongue’ and there is talk of two clerics of Llanfaes, Gregory and Gervaise, who allegedly betrayed the prince. Dafydd was severely wounded in the struggle and the younger of his sons, Owain, captured with him. They were sent to the king at Rhuddlan on the same night.

On 28 June King Edward publically announced the capture of Dafydd, ‘the last survivor of the family of traitors’, and summoned his magnates to Shrewsbury. There they would debate with the king in parliament on what should be done with Dafydd, "whom the king received as an exile, nourished as an orphan, and endowed with lands and cherished with clothing under his protection, placing him among the greater ones of the palace."

Three days earlier the king had been presented at Rhuddlan with a holy relic, Y Groes Naid or The Cross of Neath. This was believed to contain a fragment of the True Cross, kept at Aberconwy by the kings and princes of Gwynedd. Now, with the principality falling to bits and the last prince a fugitive in his own land, a band of Welsh clerics chose to give up their most sacred possession to King Edward. He carried the cross about with him for the rest of his life, and it was listed on an inventory of his personal possessions after the king’s death in 1307.

Published on June 22, 2020 03:48

Caesar's Sword

All three books of my Caesar's Sword series, a mixture of Arthurian legend and Roman history, is now available on pre-order as an ebook! Release date Friday 25 June...

All three books of my Caesar's Sword series, a mixture of Arthurian legend and Roman history, is now available on pre-order as an ebook! Release date Friday 25 June...It is the year 568 AD. From his monastic refuge in Brittany, King Arthur’s aged grandson, Coel, writes the incredible story of his life. Now a monk, he is determined to complete his chronicle before death overtakes him. His tale begins shortly after the death of his famous grandfather at the Battle of Camlann. Britain is plunged into chaos, and Coel and his mother are forced to flee their homeland. They take with them Arthur’s famous sword, Caledfwlch, once possessed by Julius Caesar. Known to the Romans as The Red Death, it is said to possess unearthly powers

Included in The White Hawk Saga are all three novels from the series:

The Red Death

Siege of Rome

Flame of the West

The Caesar's Sword Saga follows the adventures of a British warrior of famous descent in the glittering, lethal world of the Late Roman Empire. From the riotous streets of Constantinople, to the racetrack of the Hippodrome and the bloodstained deserts of North Africa, he must fight to recover his birthright and his pride

More than 200,000 words of action-packed historical fiction, ideal for fans of Bernard Cornwell, Conn Iggulden, David Gemmell and Simon Scarrow.

Published on June 22, 2020 01:12

June 21, 2020

He conquered Scotland, I tell you with certainty...

On 15 May 1307, at Forfar in Scotland, an unknown supporter of Edward I wrote to 'some high official', reporting on events in his neighbourhood. It was a bleak message: the revolt of Robert de Bruce was gaining momentum, and he had destroyed King Edward's power among Scots and English both. Scottish preachers were wandering the land, predicting the death of the old king:

"For these preachers have told the people that they have found a prophecy of Merlin, that after the death of 'le Roy Coveytous' the people of Scotland and the Welsh shall band together and have full lordship and live in peace together until the end of the world."

This report of Edward's pending demise was not greatly exaggerated - he expired only a few weeks later - but how was his position in Scotland perceived at this time? For obvious reasons Bruce's tame propagandists, armed with their prophecy of Merlin (an exceptionally busy prophet, not to mention a convenient one) were keen to broadcast the total destruction of English power in Scotland.

Pro-English chroniclers were keen to present a different view. Peter Langtoft wrote a eulogy for Edward in which the late king is presented as the flower of chivalry. He also admitted that Edward's work in Scotland was unfinished: now the great king was dead, who would provide justice for John Comyn of Badenoch, murdered by Bruce the previous year? Langtoft had his answer ready: it fell to Edward fitz Edward - Edward II - who had vowed to end the reign of Robert de Bruce.

Langtoft's hatred of Bruce is expressed in a variant MS of his chronicle. In this he describes Bruce as a deceiver, who came to Westminster pretending to be the king's friend:

"Never since Judas, I believe, has there been greater deception..."

Robert Mannyng, another English chronicler, wrote a continuation of Langtoft's work. He seems to have found Langtoft's rabid hatred of the Scots distasteful, and struck out the more abusive passages. Mannyng never questions Edward I's right to conquer Scotland, though he also regards Bruce's reign as a relatively stable and prosperous time. He once met Bruce in person at Cambridge, and expressed sorrow when two of the Scottish king's brothers were captured and executed:

"That grieves me sorely, that both were disgraced for the deeds they committed there..."

Thomas Castleford was a lesser-known English chronicler writing in the 1320s. Like Langtoft and Mannyng, he had no doubts of Edward I's rights in Scotland. He also conveyed the impression that Edward had thoroughly defeated the Scots:

"All Scotland, from the moment he began, he won and held entirely in his hand; all Scotland was won in this way by the sword, subjected learned and unlearned alike. All the magnates of Scottish descent did homage to Edward - homage and fealty forever they swore to England's king."

Castleford was right to state that the Scottish magnates did homage to Edward, yet by the 1320s it should have been obvious that Scotland was anything but conquered. The English, of course, were unwilling to admit defeat north of the border, so Castleford may have been simply projecting the common opinion of the time.

Very similar sentiments are expressed in the Brute d'Engletere Abregé, an anonymous Anglo-Norman tract from the early fourteenth century. The writer also praises Edward I for his successful conquest of Scotland:

"He conquered Scotland, I tell you with certainty, with blows of his sword in battle. There was no knight among them so strong, that he did not make them bow to his hand..."

One might be tempted to accuse English chroniclers of living in a state of denial, but this impression was not confined to England. The Flemish chronicler Lodewijk van Velthem, who had met Edward I and witnessed his Flanders campaign in 1297 at first hand, was not an admirer of the Bruces. Writing in 1315-17 in the duchy of Brabant, he lamented ruefully that as soon as Edward died ('Edeward...des conincs vader), all the old upstarts started making trouble again. He names these upstarts as Robert and Edward de Bruce, and states that Edward was the greatest king since Arthur.

Edward received many other admiring eulogies from writers in western Europe, though Scotland received scant attention. He was often credited with bringing the whole of Britain under his sway, and it may be that in 1307 the revolt of Bruce was regarded as a minor affair: Italian writers such as Dante and Giovanni Vialli, who lamented Edward's passing, don't even mention it. Whatever the reality 'on the ground' in Scotland in 1307, few outside Bruce's immediate circle were laying confident bets on victory.

Published on June 21, 2020 03:57

June 20, 2020

A private and special man

At the Oxfordshire eyre of 1285, a clerk stood up and read out an extraordinary list of charges against one Nicholas of Wantham, a canon of Lincoln. The clerk had been advised by one Robert le Eyr, a servant of the king, who showed to the justices the allegations against Nicholas. It was said that he had:

"...seditiously as a traitor has confederated himself to Guy de Montfort and Amaury his brother, and Llywelyn, formerly prince of Wales, enemy of the lord king; and he has come to the court of the lord king and made a stay in the same court as a private and special man of the aforesaid court; and by plotting and seeking to discover the secrets of the lord king and those things, which he could seek or discover in the same court from the council and secrets of the king..."

Furthermore, Nicholas had sent letters to the king's enemies, namely the Montfort brothers and Prince Llywelyn of Wales. These letters were full to bursting with 'the secrets of the lord king'. Nicholas had allegedly done all these things because he was a confederate of the aforesaid men, and a 'traitor and betrayer of the lord king'.

This was obviously no run-of-the-mill case, and perhaps a welcome change to the justices after the usual round of robberies, assaults and petty crime. Unfortunately they never got to question Nicholas in person, because he failed to obey the three customary summons to court. He was thus declared an outlaw, whom any man could slay without fear of punishment.

Who was this remarkable spy, who had burrowed his way into the heart of the royal court? We know a little more about him. In 1275 he had represented Countess Eleanor, Simon de Montfort's widow, at the court a few months before her death. On 6 January 1265, at Marlborough, King Edward granted that Nicholas could act as Eleanor's attorney in England in all pleas for and against her. The countess died on 13 April and on 6 June Nicholas was at Westmineter, tidying up his late mistress's affairs.

Nicholas therefore had close ties to the Montfort family, and was well-placed to spy on affairs at the king's court. This was a dangerous time: England had still not recovered from the scars of civil war, and conflict was brewing between King Edward and Prince Llywelyn. The king suspected the Montforts of seeking to ally with Llywelyn in order to trigger another war in England, while Llywelyn was undermined by enemies in his own realm. This paranoid, hostile atmosphere, with knives glinting in the dark and armies massing on the borders of England and Wales, was fertile ground for spies and double agents.

It seems Nicholas spent several years at the English court, but he eventually aroused suspicion. In October 1279 Eleanor de Montfort, Prince Llywelyn's wife, complained to Edward that he had not allowed Nicholas to execute her mother's will. This implies a lack of trust, though several more years passed before any action was taken against the spy in Edward's midst.

Nicholas is not known to have been captured, and like any clever agent he would have had a bolt-hole prepared in case the worst befell. His eventual fate is unknown. Perhaps he got over to France to join Guy de Montfort in exile, or vanished into the mists of Wales. Alternatively, he was tracked down by one of Edward's own 'insidiores' - spys/agents - and had his throat cut.

Published on June 20, 2020 06:35

June 19, 2020

A welter of parchment

In November 1277 Prince Llywelyn of Wales met the envoys of Edward I at Aberconwy, where the bones of Llywelyn's illustrious ancestors rested in the abbey. Here, at this site of special significance for his dynasty, Llywelyn formally surrendered to the king after a disastrous campaign. He didn't literally throw down his arms, Vercingetorix-style, but there was no need for such crude symbolism. Everyone present appreciated the enormity of Llywelyn's submission: all of his military and political gains of the past twenty years had been wiped out, and his subordinate status to the English crown rammed home with brutal finality.

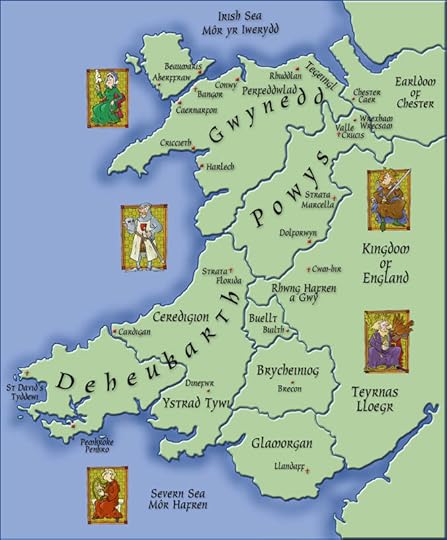

In November 1277 Prince Llywelyn of Wales met the envoys of Edward I at Aberconwy, where the bones of Llywelyn's illustrious ancestors rested in the abbey. Here, at this site of special significance for his dynasty, Llywelyn formally surrendered to the king after a disastrous campaign. He didn't literally throw down his arms, Vercingetorix-style, but there was no need for such crude symbolism. Everyone present appreciated the enormity of Llywelyn's submission: all of his military and political gains of the past twenty years had been wiped out, and his subordinate status to the English crown rammed home with brutal finality.Edward's defeat of Llywelyn in 1277 is sometimes taken as proof of the king's military skill (as opposed to the ineptitude of Henry III) and unusually aggressive policy towards Wales. In reality it was the culmination of a royal policy that his forebears had been pursuing against the lords of Gwynedd for generations, and in many respects similar to previous English campaigns. The difference lay in a few key aspects of strategy, and the resources Edward could bring to bear.

The question of homage went all the way back to the reign of Henry II (1154-89). After earlier setbacks in Wales, Henry finally achieved success when he married his half-sister Emma to Dafydd, self-styled King of North Wales and a son of Owain Gwynedd. In partnership with Lord Roger Powys of Whittingdon, Dafydd imposed his power on the king's behalf by marching into Gwynedd as far as Deganwy. From there he launched an invasion of Mon (Anglesey) and brought the entire region under his control.

Dafydd was eventually defeated and driven out, but a crucial precedent had been set. The lord of Gwynedd, head of the house of Aberffraw, had done homage to the English king for his lands in North Wales. Moreover, he had married into the king's family: this was, according to one chronicle, so Dafydd could instil fear in his Welsh enemies and take pride in having sons from royal stock.

These precedents set the tone for the next century and more. Dafydd's successor, his nephew Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (styled 'the Great') would continue the policy of marrying into the English royal family. He also swore homage to the kings of England on several occasions, the last being at Worcester in 1218. Via this agreement Llywelyn's power in Wales was recognised by the young Henry III, and it was agreed he would act as royal lieutenant in Wales during the latter's minority.

By the time Edward came on the scene, in the latter thirteenth century, there was a long history of homage and intermarriage between the ruling dynasty of England and the chief dynasty of Wales. Llywelyn's heir, Dafydd, attempted to sever feudal links with England by offering to make Wales a fiefdom of the papacy: Henry managed to foil this plan, and in 1241 the two rulers fell into dispute over certain lands in Wales.

This is where the similarities start to get eerie. Dafydd ignored several royal summons to meet Henry and discuss the matter: over twenty years later his successor, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, would repeatedly refuse to meet Edward to swear the oath of homage. When their patience ran out, Henry and Edward responded with military force. Dafydd and Llywelyn fatally overestimated the extent of their support in Wales: in 1241 and 1276 most of the other princes of Wales defected to the English. In 1241, thanks to his support among the Welsh and an unusually dry summer, Henry met with almost no resistance:

"The summer was one of remarkable drought; marshes were dried up, rivers became fordable, lakes shrank into shallow pools, and the ordinary natural obstacles to a Welsh expedition almost entirely disappeared." Sir John Lloyd, History of Wales (Volume 2)

The settlement Henry imposed proved temporary. He was obliged to campaign twice more in Wales, in 1246 and 1257, and on both occasions followed the well-worn route to Deganwy before attempting to seize Anglesey. This was the same strategy deployed by King Dafydd and Roger Powys almost a century before, and by Edward I in 1277. Indeed, it was the exact same route tramped by the Roman legions under Agricola, many centuries gone.

Henry achieved results in 1246, but his expedition of 1257 was a dismal failure. His heir's greater success in 1277 was based squarely upon the dry details of administration and logistics. In 1257 Henry was undermined by lack of finances and intrigue at his court. This was all a distant memory in 1277, when the Wardrobe (a government department) started to expand into a more efficient bureaucracy and what amounted to a private royal army. Edward also made use of the financial resources of Italian merchant-bankers, principally the Riccardi: from 1277-94, the Riccardi provided a smooth and apparently endless flow of credit to the crown, which in turn enabled the king to pump enormous resources into Wales. As one Welsh historian, Ifor Roberts, put it:

"Welsh independence did not as much perish in a clash of arms as suffocate in a welter of parchment."

At this point, however, Edward did not have it in mind to destroy Llywelyn or bring about the direct conquest of Wales. In 1277 his policy was to restore the arrangement imposed on the prince of Gwynedd by Henry III: just as in 1241 and 1246, the lands east of the River Conwy (the Perdeffwlad or Four Cantreds) were taken into royal hands, while the power of the prince was restricted to his heartlands of Snowdonia in the west. Llywelyn accompanied the king to London, where at Christmas he performed the ritual act of homage and fealty: just as Edward did himself before his overlord, the King of France.

So far as Edward was concerned, this was an end of the matter. In 1278 he wrote a cheerful letter to his officers in Gascony, informing them that Llywelyn was doing all the king asked of him. After decades of conflict and bitterness, it seemed the lords of Wales had been brought to heel at last. Edward was in for a rude awakening, but we should always place context over hindsight. To begin with at least, he attempted nothing revolutionary in Wales, and followed the policy and methods of his ancestors.

Published on June 19, 2020 01:47