A welter of parchment

In November 1277 Prince Llywelyn of Wales met the envoys of Edward I at Aberconwy, where the bones of Llywelyn's illustrious ancestors rested in the abbey. Here, at this site of special significance for his dynasty, Llywelyn formally surrendered to the king after a disastrous campaign. He didn't literally throw down his arms, Vercingetorix-style, but there was no need for such crude symbolism. Everyone present appreciated the enormity of Llywelyn's submission: all of his military and political gains of the past twenty years had been wiped out, and his subordinate status to the English crown rammed home with brutal finality.

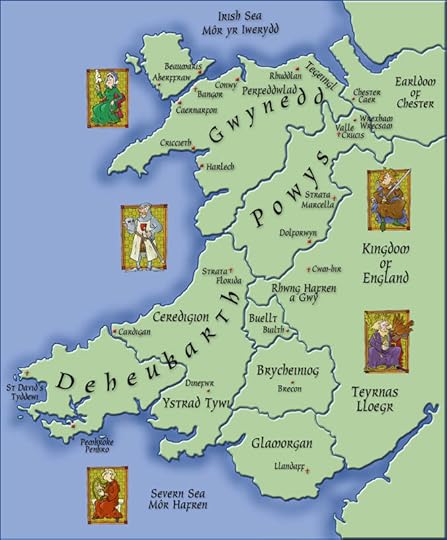

In November 1277 Prince Llywelyn of Wales met the envoys of Edward I at Aberconwy, where the bones of Llywelyn's illustrious ancestors rested in the abbey. Here, at this site of special significance for his dynasty, Llywelyn formally surrendered to the king after a disastrous campaign. He didn't literally throw down his arms, Vercingetorix-style, but there was no need for such crude symbolism. Everyone present appreciated the enormity of Llywelyn's submission: all of his military and political gains of the past twenty years had been wiped out, and his subordinate status to the English crown rammed home with brutal finality.Edward's defeat of Llywelyn in 1277 is sometimes taken as proof of the king's military skill (as opposed to the ineptitude of Henry III) and unusually aggressive policy towards Wales. In reality it was the culmination of a royal policy that his forebears had been pursuing against the lords of Gwynedd for generations, and in many respects similar to previous English campaigns. The difference lay in a few key aspects of strategy, and the resources Edward could bring to bear.

The question of homage went all the way back to the reign of Henry II (1154-89). After earlier setbacks in Wales, Henry finally achieved success when he married his half-sister Emma to Dafydd, self-styled King of North Wales and a son of Owain Gwynedd. In partnership with Lord Roger Powys of Whittingdon, Dafydd imposed his power on the king's behalf by marching into Gwynedd as far as Deganwy. From there he launched an invasion of Mon (Anglesey) and brought the entire region under his control.

Dafydd was eventually defeated and driven out, but a crucial precedent had been set. The lord of Gwynedd, head of the house of Aberffraw, had done homage to the English king for his lands in North Wales. Moreover, he had married into the king's family: this was, according to one chronicle, so Dafydd could instil fear in his Welsh enemies and take pride in having sons from royal stock.

These precedents set the tone for the next century and more. Dafydd's successor, his nephew Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (styled 'the Great') would continue the policy of marrying into the English royal family. He also swore homage to the kings of England on several occasions, the last being at Worcester in 1218. Via this agreement Llywelyn's power in Wales was recognised by the young Henry III, and it was agreed he would act as royal lieutenant in Wales during the latter's minority.

By the time Edward came on the scene, in the latter thirteenth century, there was a long history of homage and intermarriage between the ruling dynasty of England and the chief dynasty of Wales. Llywelyn's heir, Dafydd, attempted to sever feudal links with England by offering to make Wales a fiefdom of the papacy: Henry managed to foil this plan, and in 1241 the two rulers fell into dispute over certain lands in Wales.

This is where the similarities start to get eerie. Dafydd ignored several royal summons to meet Henry and discuss the matter: over twenty years later his successor, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, would repeatedly refuse to meet Edward to swear the oath of homage. When their patience ran out, Henry and Edward responded with military force. Dafydd and Llywelyn fatally overestimated the extent of their support in Wales: in 1241 and 1276 most of the other princes of Wales defected to the English. In 1241, thanks to his support among the Welsh and an unusually dry summer, Henry met with almost no resistance:

"The summer was one of remarkable drought; marshes were dried up, rivers became fordable, lakes shrank into shallow pools, and the ordinary natural obstacles to a Welsh expedition almost entirely disappeared." Sir John Lloyd, History of Wales (Volume 2)

The settlement Henry imposed proved temporary. He was obliged to campaign twice more in Wales, in 1246 and 1257, and on both occasions followed the well-worn route to Deganwy before attempting to seize Anglesey. This was the same strategy deployed by King Dafydd and Roger Powys almost a century before, and by Edward I in 1277. Indeed, it was the exact same route tramped by the Roman legions under Agricola, many centuries gone.

Henry achieved results in 1246, but his expedition of 1257 was a dismal failure. His heir's greater success in 1277 was based squarely upon the dry details of administration and logistics. In 1257 Henry was undermined by lack of finances and intrigue at his court. This was all a distant memory in 1277, when the Wardrobe (a government department) started to expand into a more efficient bureaucracy and what amounted to a private royal army. Edward also made use of the financial resources of Italian merchant-bankers, principally the Riccardi: from 1277-94, the Riccardi provided a smooth and apparently endless flow of credit to the crown, which in turn enabled the king to pump enormous resources into Wales. As one Welsh historian, Ifor Roberts, put it:

"Welsh independence did not as much perish in a clash of arms as suffocate in a welter of parchment."

At this point, however, Edward did not have it in mind to destroy Llywelyn or bring about the direct conquest of Wales. In 1277 his policy was to restore the arrangement imposed on the prince of Gwynedd by Henry III: just as in 1241 and 1246, the lands east of the River Conwy (the Perdeffwlad or Four Cantreds) were taken into royal hands, while the power of the prince was restricted to his heartlands of Snowdonia in the west. Llywelyn accompanied the king to London, where at Christmas he performed the ritual act of homage and fealty: just as Edward did himself before his overlord, the King of France.

So far as Edward was concerned, this was an end of the matter. In 1278 he wrote a cheerful letter to his officers in Gascony, informing them that Llywelyn was doing all the king asked of him. After decades of conflict and bitterness, it seemed the lords of Wales had been brought to heel at last. Edward was in for a rude awakening, but we should always place context over hindsight. To begin with at least, he attempted nothing revolutionary in Wales, and followed the policy and methods of his ancestors.

Published on June 19, 2020 01:47

No comments have been added yet.