David Pilling's Blog, page 22

July 9, 2021

The might of Clare

In summer 1257 Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd marched into Glamorgan and attacked the Clare stronghold of Llangynwyd. This was part of the 'great war' described in the Annales Cambriae, whereby Llywelyn and his allies made a determined effort to achieve hegemony over Wales.

In summer 1257 Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd marched into Glamorgan and attacked the Clare stronghold of Llangynwyd. This was part of the 'great war' described in the Annales Cambriae, whereby Llywelyn and his allies made a determined effort to achieve hegemony over Wales.The destruction of Llangynwyd is recorded in a Latin chronicle in the British Library (BL Royal 6B xi f. 108 v), noticed by Professor J Beverley Smith. It translates as:

“Lord Richard, Earl of Gloucester, came to Cardiff with a multitude of armed men. And Llywelyn was near Margam abbey with a strong force. On the 13 July Llywelyn advanced upon Llangynwyd and burnt the castle of the lord earl, killing twenty-four of the earl's men, the lord earl then being with a strong force at Llanblethian.”

It appears Llywelyn stormed and razed the castle and slaughtered the garrison. A later charter of 1262 notes that eighty houses in the adjoining vill were also destroyed. This was after Llywelyn's invasion of the lordship of Gower, recorded in the Peniarth Brut:

“In Lent he came with a great army to Kidwelly and Carnwyllion and Gower and he completely burned the part belonging to the English in those lands, along with Swansea, and he subjugated to himself all the Welsh of those lands.”

Llywelyn had caused much destruction, but he had not affected a permanent conquest or subjugation. In the following year, 1258, another Venedotian army marched into the lordship and attacked Neath. The castle held out, but the mill was destroyed along with 150 houses of the town. Llantrisant may have been attacked at the same time. All of this may have prompted Earl Richard to build Morgraig Castle to protect his territory from the uplands Welsh of Senghenydd.

At his death in 1262, it is clear that the earl had not subdued the Welsh of Blaenau on the fringes of his land. This is shown by the appointment of Humphrey Bohun to keep strong garrisons at Cardiff, Llantrisant, Neath and Tal-y-Fan. He was also given Llangynwyd, which had been hurriedly rebuilt; during his brief custodianship (1262-3), payments are recorded for repairs along with 28 men and 8 horses maintained at the castle.

Earl Richard was succeeded by Gilbert de Clare, 'the red dog', who would play a major role in the wars of England and Wales. As lord of the mighty Honour of Clare, able to call upon the military service of 456 knights, with extensive manors and rights in both countries, Gilbert was almost a king in his own right. Which was seriously bad news for everyone, not least the Welshry of Senghenydd.

Published on July 09, 2021 05:28

July 8, 2021

Siward's injustice

On 5 July 1245, at the shire court of Glamorgan held at Stalling Down near Cowbridge, Earl Richard de Clare brought charges against Richard Siward. The latter was accused of sedition and felony against the good faith which he owed the earl, since he had broken a truce made between Clare and Hywel ap Maredudd, lord of Mysgyn.

On 5 July 1245, at the shire court of Glamorgan held at Stalling Down near Cowbridge, Earl Richard de Clare brought charges against Richard Siward. The latter was accused of sedition and felony against the good faith which he owed the earl, since he had broken a truce made between Clare and Hywel ap Maredudd, lord of Mysgyn.The charges describe how Siward attacked Hywel on 27 December 1244, in breach of a truce made in November. He had allegedly invaded Hywel's lands and captured a number of prominent local Welsh freemen. Hywel retaliated in kind and seized Thomas of Hodnet, one of Siward's knights, and demanded a ransom of 200 marks for his release.

When reproached by the Sheriff of Glamorgan, Hywel cited Siward's original breach of the peace, and the result was a conference held at 'the mill of Sogod', on the borders of Hywel's territory. Six men of the earl, and six of the earl, agreed to meet to smooth out problems and re-establish the peace. Siward, who was present, swore to abide by an arrangement the twelve reached. He then changed his mind when they ordered him to surrender his Welsh captives. In response he declared that “the earl's truce was none of his business, and he had no desire whatever to keep it.”

There was something shifty going on. After the meeting broke up, Siward secretly met with Hywel and came to a private agreement. They joined forces and turned on Siward's lord, Earl Richard, who was taken completely by surprise. The allies ravaged his estates at will, causing over £1000 worth of damage and forcing Clare and his knights to take refuge inside their castles, 'so closely that they dared not put their noses outside the gates'.

All these charges were laid against Siward at the shire court on 5 July. Siward was offered trial by battle against Stephen Bauzan, who would later die at the Battle of Cymerau, but refused on the grounds that Bauzan was neither from Glamorgan nor one of the peers of the court. Earl Richard, by now very cross indeed, demanded the court to judge whether Bauzan was a fit opponent. This required an adjournment, and Siward was asked to provide sureties that he would turn up at the next court. Nobody would stand up for him, so he had to surrender his castle of Tal-y-fan as a pledge. Siward did not obey the court summons, and was formally outlawed on 30 October 1245.

Or at least that was Clare's version of events. When he came before Henry III in April 1247, Siward told a different story. He alleged that Clare's bailiffs had seized him and forced him to hand over his nephew, Payn de St Philebert, as a hostage. Afterwards they seized the constable of Tal-y-fan and made Siward pay a ransom of sixty marks to have him back. For good measure Clare's men also confiscated Siward's livestock and goods.

On a close reading of the evidence, it appears history has done Siward a disservice. The surviving records of the court show that Earl Richard manipulated the legal process: Siward was not formally summoned to answer the charge of sedition, and it was illegal to force a man to argue his case on a charge for which he not been summoned. The earl had in fact cheated Siward and stolen his lands.

The same can be said for Siward's relationship with Hywel ap Maredudd. The two men were allies, not enemies, and both suffered at Clare's hands. In 1246 it was recorded that Hywel had fled to the court of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth in Gwynedd, 'having been completely dispossessed by the earl of Clare'.

The dispossession of Hywel followed shortly after the outlawry and dispossession of Siward. After he had appropriated Siward's manors of Llanblethian and Tal-y-fan, Earl Richard annexed the commote of Mysgyn and the contiguous commote of Glynrhondda, which he had earlier taken from one of Hywel's kinsmen. Henceforth, these lands were held by the Clares as chief lords in demesne, which left only the two Welsh-held upland commotes of Senghenydd to resist their encroaching power.

Published on July 08, 2021 03:51

July 7, 2021

Death of Longshanks

On this day in 1307 Edward I kicked the bucket in a desolate Cumbrian marsh at Burgh-on-Sands, within sight of the Scottish border.

On this day in 1307 Edward I kicked the bucket in a desolate Cumbrian marsh at Burgh-on-Sands, within sight of the Scottish border.Edward is possibly the most divisive ruler in English history, with the exception of Oliver Cromwell. By our standards he was cruel and devious and unpleasant, with a coarse sense of humour and none of the vulnerable qualities that make other members of his dynasty so attractive. In context he was not much different in moral terms to anyone else; Philippe le Bel and Robert de Bruce - to name just two - did equally terrible things in the pursuit of power.

In terms of his achievements, Edward will forever be judged - rightly - by his dishonest and ruthless intervention in Scottish affairs. Prior to 1294, he had failed at virtually nothing and presided over a long list of achievements: these included the recovery of lands in France, the complete overhaul of law and administration in England, and the conquest of Wales.

Edward's victory in Wales is sometimes rationalised as a mere 'occupation', or the inevitable result of vast resources hurled at a tiny country; as if Wales was a weak little land that had not defended itself against endless invasions for the previous two hundred years, and the Welsh a feeble and defenceless people. Such arguments are usually fuelled by revisionism or emotion, but ultimately there is no escape: the Edwardian conquest of Wales was thorough and entire, and it is impossible to wish it away.

On the debit side, Edward's decision to get involved in Scotland proved a total disaster: despite temporary successes, Edward could not impose a permanent settlement on the Scots and the war sucked away his money and resources. That is all hindsight of course, and it would have been a strange medieval king who did not try to exploit what appeared to be an opportunity.

His heir, Edward II, proved so incompetent it is difficult to know if a more able man could have redeemed his father's mistake. However it took decades for the English in general to realise that Scotland could not be conquered, and Edward I's contemporary reputation did not suffer for it: or at least it didn't south of the border, where he was remembered fondly in warlike jingles such as:

"He was lord of England,

And a king who well knew war;

None could read in any book

Of a king who better upheld his land.

All those things he wished to accomplish,

He wisely brought to an end."

- (Lament on the death of Edward I, translated from Norman-French by Thomas Wright)

Published on July 07, 2021 07:12

Set a thief to...

Attached is the seal of Gilbert de Clare (1180-1230), 5th Earl of Gloucester, 7th lord of Clare and 1st Earl of Glamorgan.

Attached is the seal of Gilbert de Clare (1180-1230), 5th Earl of Gloucester, 7th lord of Clare and 1st Earl of Glamorgan.Clare succeeded to the lordship of Glamorgan in 1217, at a time when the lordship or honour was effectively split between English control of the lowlands and Welsh control of the upland region of Blaenau. The Welsh lords of Blaenau were being gradually drawn to the allegiance of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, thanks in part to English inheritance policy. One bone of contention was the manor of Newcastle, which had been held by a Welsh lord, Leision ap Caradog. Upon his death the manor did not pass to his brother, Morgan Gam, but reverted to King John's former wife, Countess Isabel. This affront enraged Morgan, who was soon leading a revolt against Earl Gilbert.

Welsh incursions disturbed the lowlands in 1224, when the abbey of Neath was plundered. More widespread raids followed two years later, when the vills of Newcastle, Laleston and St Nicholas were attacked. These were probably led by Morgan Gam, who was captured and imprisoned by Clare in 1228. His kinsman Hywel ap Maredudd, lord of Misgyn, continued the fight and took a large war-band to Kenfig, where they sacked the town. Morgan was released in 1229, and the lowlands were still threatened when Clare died in 1230.

Morgan now joined hands with Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, who in 1231 brought his host into Glamorgan and destroyed Neath Castle. Kenfig was attacked and plundered a second time, although the castle managed to hold out. In 1232 the unpopular custodian of Glamorgan, Hubert de Burgh, was sacked by Henry III and replaced by Peter des Rivaux. This in turn – for various complex reasons, mostly involving money – triggered the revolt of Richard Marshal, Earl of Pembroke.

Marshal's rebellion was supported by most of the English knights of Glamorgan as well as Llywelyn ab Iorwerth and the Welsh lords of Blaenau. The handful of royalist knights, such as John de St Quintin of Llanblethian, were soon overrun. One of Marshal's chief supporters, Richard Siward, seized the St Quintin manors of Llanblethian and Talyfan, while Marshal granted lands to his Welsh followers. These included unspecified grants to Morgan Gam, Hywel ap Maredudd and Rhys ap Gruffudd of Senghenydd.

When peace was struck with the king in 1234, most of these lands were returned to their original owners. Siward, however, held onto his hands and 'persuaded' St Quintin to exchange them for lands in Wiltshire. Following the settlement, Siward was appointed royal custodian of Glamorgan: set a thief to catch a thief.

An uneasy peace reigned in Glamorgan until the death of Morgan Gam in 1241. His kinsman Hywel assumed leadership of the Welsh uplands, while the grasping Siward remained unsatisfied with his lot.

Published on July 07, 2021 01:50

July 5, 2021

Douglas the Hardy

Faside Castle today On 5 July 1291 Sir William Douglas, called the Hardy, swore homage and fealty to Edward I at the chapel of Thurston manor, near Innerwick in East Lothian. He is one of a long list of named Scottish prelates and nobles who did homage to the English king throughout July.

Faside Castle today On 5 July 1291 Sir William Douglas, called the Hardy, swore homage and fealty to Edward I at the chapel of Thurston manor, near Innerwick in East Lothian. He is one of a long list of named Scottish prelates and nobles who did homage to the English king throughout July.Douglas was the son of William Longleg, lord of Douglas and the manor of Fawdon in Northumberland. In 1268 the younger William was almost killed in a violent feud between his father and Gilbert Umfraville, Earl of Angus. While the future Edward I was besieging Montfortian rebels at Alnwick castle, Angus came to the English prince and accused Longleg of being a traitor.

Edward insisted on enquiry before judgement, but Angus wasn't prepared to wait. He hired a gang of 'free lances' from Redesdale – ancestors of the Border Reivers – and sent them to attack Longleg and his family at Fawdon. The manor was pillaged and the entire family kidnapped and taken to Angus's castle at Harbottle. During the fight William the Hardy suffered a near-fatal injury to his neck: Ita quod fere amputaverunt caput ejus – So as to nearly cut off his head. His survival was a miracle, and may well have inspired his nickname of 'the Hardy'.

Douglas pursued a violent career. In 1288 he was called upon by Sir Andrew Moray to imprison his uncle, Sir Hugh Abernethy, at Douglas castle. Abernethy had been party to the murder of Donnchadh III, Earl of Fife and one of the six Guardians of Scotland after the untimely death of Alexander III. He died in custody despite the efforts of Edward I to have him released.

About the same time Douglas's first wife, Elizabeth Stewart, died in childbirth. In need of a second wife, Douglas set his eye on Eleanor de Louvaine, recently widowed wife of William Ferrers of Groby. Eleanor's late husband had held five manors in Scotland, and Eleanor came north to collect the rents. While staying at the castle of Fa'side near Tranent, she was ambushed and abducted by Douglas, who spirited her away to Douglas castle.

The kidnapping of rich noblewomen was not uncommon. English barons such as John Giffard and his kinsman Osbert were guilty of it, while Simon de Montfort the younger had actually pursued Isabella de Forz, a wealthy heiress, all the way into Wales. The idea was to capture these women, take them off to some strong castle and force them to marry their abductors.

Before he could induce Eleanor up the aisle, Douglas was captured and imprisoned by the Guardians. To the fury of King Edward, he was then released and permitted to wed his captive. In response Edward ordered the Sheriff of Northumberland to seize all Douglas lands and goods in England and the Guardians of Scotland to arrest Douglas and deliver him and Eleanor to the king. The Guardians did not respond, but by early 1290 Douglas had fallen into Edward's hands and was held prisoner at Knaresborough.

It seems Eleanor had no objection to her new husband. She and four other sureties or manucaptors posted bail to have him released; the sureties were her English cousins, including the Baron Hastings and Baron Segrave. Afterwards Douglas had his lands restored by the king, though Edward was still not happy about the affair and fined Eleanor £100. By way of payment some of her lands in Essex and Hertfordshire were briefly seized by the crown in 1296.

Published on July 05, 2021 01:28

July 4, 2021

Royal justice (or not...)

Click here On 4 July 1300 thirty-one valets of the garrison at Roxburgh were summoned to join the main English army at Carlisle. Six days later one hundred and three archers were also withdrawn from Roxburgh and sent west to join the king's host. These archers would suffer a bit on the ensuing Scottish campaign: between 10 July and their last payment date on 25 August, their number would reduce from 103 to 93. As usual we have no idea if these losses were due to death or desertion.

Click here On 4 July 1300 thirty-one valets of the garrison at Roxburgh were summoned to join the main English army at Carlisle. Six days later one hundred and three archers were also withdrawn from Roxburgh and sent west to join the king's host. These archers would suffer a bit on the ensuing Scottish campaign: between 10 July and their last payment date on 25 August, their number would reduce from 103 to 93. As usual we have no idea if these losses were due to death or desertion. Back in May 1296, when Edward I's original invasion was still underway, he had appointed Sir Walter Touk as keeper and sheriff of Roxburgh. On 8 September, for no stated reason, Touk was ordered to surrender his post and hand over to Sir Richard Waldegrave. Possibly the king was unwilling to place too much faith in Touk. Like so many of Edward's followers, he was a reformed Montfortian who had spent his youth in revolt against the old king, Henry III. When royal commissioners came to Newark in 1276, they found that Touk was the ringleader of a gang that levied blackmail on people travelling through the northern part of Sherwood Forest, between Kelum and Newark. Touk's particular speciality was to hijack royal carts passing along the highway and ransom them.

Medieval justice was slow, and Touk might have committed these offences during the civil war of the previous decade: he and several others were officially pardoned at Westminster on 26 October 1268. Alternatively, perhaps he wiped his backside on the king's pardon and carried on robbing for another eight years. Even as he moved into middle age, Touk remained a scoundrel. In the early 1280s he was accused before King's Bench of robbing several of his neighbours at Kelum, but apparently escaped punishment.

In 1295, only a year before his brief appointment at Roxburgh, Touk was involved in the most notorious crime of all. On 13 October of that year one Beatrice widow of Richard of Kelham came before King's Bench and accused seventeen men of murdering her husband. Her appeal went into considerable detail, and describes how Richard died in her arms at a spot forty feet from the boundary of the town of Staythorpe at the ninth hour of the day on Monday 16 May 1295. Beatrice claimed her husband died in a secluded spot called the 'Wro', which derives from Old Norse 'vra' for nook, corner or secluded spot, and was well known in the Newark area. The name of 'Le Wro' in Staythorpe survived until at least 1838, when it appeared on an OS map. At the time of the killing it was described as a field.

In court Beatrice alleged that her husband had been ambushed and killed in the field in a pre-meditated ambush organised by three local men, one of whom was Walter Touk. The man who delivered the fatal blow was one John Cutte, who hit Richard with a Danish axe, made of iron and steel, with a shaft of ash one yard in length and five inches in circumference. The blade cut Richard between the crown and right ear, opening a wound six inches long, two inches wide, and three inches deep as far as the brain. In her own words, Beatrice said that this alone was enough to kill him:

"Such that even if he had not received any wound from any of the other assailants he would have died in her arms."

After Richard's death, Beatrice ran for help and raised the hue and cry in the nearest four villages. Seven of the alleged killers were summoned to court and the roll contains a detailed description of their weapons: interestingly, one man was armed with what sounds like a longbow, 'a bow made of yew a yard and a half long and four inches in circumference'. To defend themselves, Touk and his accomplices quibbled over the form of the writs brought against them by Beatrice. The royal justices clearly took the affair seriously and commited Touk and nine other men to prison until a sentence could be reached.

At this point some friends in high places intervened. As was standard practice, the ten men men committed to gaol found sureties or 'mainpernors' for their bail. Of these, five were officers of the Bench at Westminster, expert lawyers who later went on to become royal justices. These officers or sergeants constructed an elaborate appeal against Beatrice's allegation.

The case was still in progress in spring 1296, when Walter Touk was on military service in Scotland. On 27 March he received a writ of the king's special grace, excusing him from appearing in court to answer Beatrice for as long as the war lasted. Touk's writ was copied into the roll in a different hand, in a large gap following the main list of accused. The case against his accomplices rumbled on until 13 October 1299, after which it drops out of the rolls and is never seen again.

What appears to have happened is that three local knights, including Touke, arranged the killing of a lesser status individual in Nottinghamshire. Very little is known of their victim, and there is no hint in the records of their motive for killing him. Richard had no previous criminal record, but it seems likely that he had threatened the social and economic dominance of the three knights in some way. Touke and his companions were men of some local importance, with important links to other local gentry and to Westminster.

Ironically, Touke had been appointed to enforce the Statute of Westminster (1285) to enforce the peace in England, and would serve on a similar commission in 1300. After his service in Scotland, he was made a justice of gaol delivery in Lincolnshire and would repeatedly serve on commissions of the peace until his death in 1314.

There is absolutely nothing unusual about Touke's career: one could pick out any number of violent, homicidal, corrupted local gentry who also served as judges and commissioners of the peace in medieval England. Another example is Sir James Coterel, leader of the notorious Coterel Gang in the reign of Edward II, who went on to serve Edward III in France and ended his days as a justice and royal bailiff.

Published on July 04, 2021 03:54

June 19, 2021

Edward I and Wales

So my book on Edward I and Wales is finally available now, or so the publishers (Pen & Sword) assure me. Please click on the image above to see the book on Amazon.

So my book on Edward I and Wales is finally available now, or so the publishers (Pen & Sword) assure me. Please click on the image above to see the book on Amazon."The late 13th century witnessed the conquest of Wales after two hundred years of conflict between Welsh princes and the English crown. In 1282 Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the only native Prince of Wales to be formally acknowledged by a King of England, was slain by English forces. His brother Dafydd continued the fight, but was eventually captured and executed. Further revolts followed under Rhys ap Maredudd, a former crown ally, and Madog ap Llywelyn, a kinsman of the defeated lords of Gwynedd.

The Welsh wars were a massive undertaking for the crown, and required the mobilisation of all resources. Edward's willingness to direct the combined power of the English state and church against the Prince of Wales, to an unprecedented degree, resulted in a victory that had eluded all of his predecessors. This latest study of the Welsh wars of Edward I will draw upon previously untranslated archive material, allowing a fresh insight into military and political events. Edward I's personal relationship with Welsh leaders is also reconsidered.

Traditionally, the conquest is dated to the fall of Llywelyn in December 1282, but this book will argue that Edward was not truly the master of Wales until 1294. In the years between those two dates he broke the power of the great Marcher lords and crushed two further large-scale revolts against crown authority. After 1294 he was able to exploit Welsh manpower on a massive scale. His successors followed the same policy during the Scottish wars and the Hundred Years War.

Edward enjoyed considerable support among the ‘uchelwyr' or Welsh gentry class, many of whom served him as diplomats and spies as well as military captains. This aspect of the king's complex relationship with the Welsh will also feature."

Published on June 19, 2021 01:22

June 2, 2021

Blood and Gold

My new ebook, THE CHAMPION (II): BLOOD AND GOLD is now available. This is the second episode of the adventures of En Pascal de Valencia - knight, mercenary, unwilling hero, frustrated lover, abysmal spy - an Aragonese soldier of fortune in the days of Edward Longshanks and Robert de Bruce.

My new ebook, THE CHAMPION (II): BLOOD AND GOLD is now available. This is the second episode of the adventures of En Pascal de Valencia - knight, mercenary, unwilling hero, frustrated lover, abysmal spy - an Aragonese soldier of fortune in the days of Edward Longshanks and Robert de Bruce. These tales are drawn from the “Life of En Pascal”, a mid-fourteenth century manuscript discovered in the former Royal Archive of Barcelona, now the Archive of the Crown of Aragon. Any historical errors, unlikely claims and wild boasts are the fault of the original author.*

*Some of this may not be true either.

The book is currently on Kindle only, audio and hard copy versions may follow.

Published on June 02, 2021 00:34

May 13, 2021

Rock me, Amadeus

On Palm Sunday 1282 the Welsh rose in revolt under Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and attacked the royal castles of Hawarden, Flint and Rhuddlan. Hawarden was captured and the township of Flint plundered, but the garrisons of the latter two castles held out.

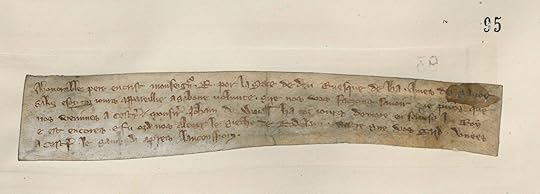

On Palm Sunday 1282 the Welsh rose in revolt under Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and attacked the royal castles of Hawarden, Flint and Rhuddlan. Hawarden was captured and the township of Flint plundered, but the garrisons of the latter two castles held out.According to the Annals of Chester, the siege of Rhuddlan was broken by Reynold Grey, justice of Chester. A surviving letter (attached) shows that it was really Amadeus of Savoy, the future Count Amadeus the Great, who raised the siege.

The letter itself is unremarkable, and merely confirms that a certain John Wuall of Odell in Bedfordshire was serving in the English army. Amadeus informs Robert Burnell, the chancellor, that Wuall was in the service of the king 'with us at the raising of the siege of Rhuddlan'. Pay records confirm that Amadeus was in command of fifteen knights with thirty-one troopers in attendance, and sixty troopers paid separately.

Amadeus was the second son of Thomas III of Piedmont, who had a rival claim to Savoy against his uncle, Count Philip. The two kinsmen spent their lives in dispute over the inheritance, but Thomas never made good his claim. Perhaps in an effort to curry favour, Amadeus attached himself to the household of Edward I. He was with the king at St-Georgés-d'Ésperanche in Savoy in 1273, and in North Wales during the first war against Prince Llywelyn in 1277.

Amadeus appears to have been a sickly sort, or perhaps he struggled with the Welsh climate; in December 1277 he was obliged to stay at Montgomery due to illness. At about the same time he was knighted by Edward, and received £40 as a gift. In February 1278 he went to compete in a tournament in Germany, but fell sick again when he returned to England. In June Master Simon the surgeon was paid by the king to attend Amadeus at Marlborough, and shortly afterwards Edward travelled via Millbank to visit the patient at the Savoy palace.

Whatever ailed him, Amadeus was fully recovered by the spring of 1282. Between 8-30 April he was paid to take command of the king's cavalry at Chester, along with another Savoyard, Othon Grandson. It was most likely these two, with or without Reynold Grey, who rode to break Dafydd's siege of Rhuddlan.

As usual, nothing happened in isolation. Amadeus did not do military service for Edward I as a favour: he wanted to be the next Count of Savoy, and earn the king's support for his claim. Then the succession crisis took an unexpected twist. In May 1282, just as things were heating up in Wales, Amadeus's father Thomas was killed in battle in France.

Published on May 13, 2021 04:22

May 12, 2021

Not for dancing

[image error] On 5 November 1281 Count Philip of Savoy wrote to Edward I, asking for military aid against the German emperor, Rudolph of Hapsburg. The emperor had, Philip wrote, invaded his lands and devastated his castles – 'depredat et incendio devastat et castra nostra obsidere intendat'. Unless the King of England sent help, Philip lived in terror of his fate.

This war was the direct consequence of Edward's uncle, Richard of Cornwall, granting three towns inside the empire to Philip's predecessor, Peter II. These towns were Payerne, Morat and Gumminen, granted by Richard during his term as King of Germany (1256-72).

Rudolph was determined to claw back the lost lands, and seized on any opportunity to attack Philip. He also waged war against Count Robert of Burgundy and Count Reynold of Montbelliard, who wished to transfer their lands from the empire to France. When the king of France, Philip III, threatened to bring an army against Rudolph, the emperor sneered:

“Let your king come if he has a mind, we will prepare a reception, and show that we are not here for dancing.”

Count Philip's request for aid threw Edward into a quandary. He had already been asked to supply troops by his aunt, Margaret of Provence, to join her anti-Angevin league against Charles of Anjou. Margaret and her sister, Eleanor, had cleverly arranged to have Edward's brother Edmund made Count of Brie and Champagne in France. This was done solely to give Edmund the necessary prestige and resources to join the coalition against Charles.

Edward's response was to send Othon Grandson, a trusted Savoyard emissary, to the German court to try and broker peace. Count Philip informed Edward that Rudolph refused to even grant the English envoys an audience, although Othon was allowed to talk with the emperor's representatives. This had some effect, as a truce was drawn up in the summer of 1283. The terms of the truce expressly mention Edward along with his aunt, Margaret, as two of those by whose request the agreement was reached. It seems that Margaret, one of the ablest politicians of her day, had her fingers in a great many pies.

There remained the issue of the war against Charles in Provence. This would prove much more difficult to untangle.

This war was the direct consequence of Edward's uncle, Richard of Cornwall, granting three towns inside the empire to Philip's predecessor, Peter II. These towns were Payerne, Morat and Gumminen, granted by Richard during his term as King of Germany (1256-72).

Rudolph was determined to claw back the lost lands, and seized on any opportunity to attack Philip. He also waged war against Count Robert of Burgundy and Count Reynold of Montbelliard, who wished to transfer their lands from the empire to France. When the king of France, Philip III, threatened to bring an army against Rudolph, the emperor sneered:

“Let your king come if he has a mind, we will prepare a reception, and show that we are not here for dancing.”

Count Philip's request for aid threw Edward into a quandary. He had already been asked to supply troops by his aunt, Margaret of Provence, to join her anti-Angevin league against Charles of Anjou. Margaret and her sister, Eleanor, had cleverly arranged to have Edward's brother Edmund made Count of Brie and Champagne in France. This was done solely to give Edmund the necessary prestige and resources to join the coalition against Charles.

Edward's response was to send Othon Grandson, a trusted Savoyard emissary, to the German court to try and broker peace. Count Philip informed Edward that Rudolph refused to even grant the English envoys an audience, although Othon was allowed to talk with the emperor's representatives. This had some effect, as a truce was drawn up in the summer of 1283. The terms of the truce expressly mention Edward along with his aunt, Margaret, as two of those by whose request the agreement was reached. It seems that Margaret, one of the ablest politicians of her day, had her fingers in a great many pies.

There remained the issue of the war against Charles in Provence. This would prove much more difficult to untangle.

Published on May 12, 2021 01:13