David Pilling's Blog, page 36

January 9, 2020

The pass of Aberconwy

“Therefore the king sent for the Irish, who came and in that part of Wales called Anglesey, depopulated the land by the sword and devastated everything with fire. The Irish have an old hatred of the Welsh and were eager to take vengeance on their enemies.”

- Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora

In autumn 1245 about 3000 Irish troops landed on Anglesey, destroyed the harvest and exterminated the population. They were summoned by Henry III, who ordered the treasurer of Dublin to pay them the standard wage of tuppence a day from 18-29 October. A few days later the king withdrew from Deganwy. He had achieved his primary aim of strengthening the castle - “like a thorn in Dafydd’s eye” - though the material and human cost was obscene. English and Welsh chroniclers describe corpses piled on the banks of the Conwy, or else rotting on the riverbed.

Henry was showing a brutal determination he had not previously displayed in Wales. He gave orders for the economic blockade to continue, and for the Marchers to continue to attack Dafydd’s allies. He had previously refused an offer of peace from Dafydd’s distain or seneschal, Ednyfed Fychan, and made it plain he intended to break his nephew at any price. Dafydd had been ill for two years. As early as 1244 the prince informed his uncle he could not come to court, since he was suffering from a strange malady. This was a combination of alopecia and onycholysis, which caused his hair and fingernails to fall out. There is a suspicion Dafydd was poisoned, but if so it was a very slow poisoning.

The extreme stress of the war proved too much for Dafydd’s fragile health. He died at his winter court at Aber in Arllechwedd on 25 February 1246, worn out by the effort of keeping “the pass of Aberconwy”. He was forty-five. Dafydd Benfras composed the prince’s elegy (translated and slightly modified by Sir John Lloyd):

“He was a man who sowed the seed of joy for his people,

Of the right royal lineage of kings.

So lordly his gifts, ‘twas strange

He gave not the moon in Heaven!

Ashen of hue this day is the hand of bounty,

The hand that last year kept the pass of Aberconwy.”

Shortly before Dafydd died, a man named Nicholas de Molis arrived in Wales. Nicholas is virtually lost to modern historiography, but his presence sent a ripple of dread through the Welsh chronicles. He had recently smashed the Basques under Thibaut the Troubadour, King of Navarre, and now King Henry unleashed him on Gwynedd.

- Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora

In autumn 1245 about 3000 Irish troops landed on Anglesey, destroyed the harvest and exterminated the population. They were summoned by Henry III, who ordered the treasurer of Dublin to pay them the standard wage of tuppence a day from 18-29 October. A few days later the king withdrew from Deganwy. He had achieved his primary aim of strengthening the castle - “like a thorn in Dafydd’s eye” - though the material and human cost was obscene. English and Welsh chroniclers describe corpses piled on the banks of the Conwy, or else rotting on the riverbed.

Henry was showing a brutal determination he had not previously displayed in Wales. He gave orders for the economic blockade to continue, and for the Marchers to continue to attack Dafydd’s allies. He had previously refused an offer of peace from Dafydd’s distain or seneschal, Ednyfed Fychan, and made it plain he intended to break his nephew at any price. Dafydd had been ill for two years. As early as 1244 the prince informed his uncle he could not come to court, since he was suffering from a strange malady. This was a combination of alopecia and onycholysis, which caused his hair and fingernails to fall out. There is a suspicion Dafydd was poisoned, but if so it was a very slow poisoning.

The extreme stress of the war proved too much for Dafydd’s fragile health. He died at his winter court at Aber in Arllechwedd on 25 February 1246, worn out by the effort of keeping “the pass of Aberconwy”. He was forty-five. Dafydd Benfras composed the prince’s elegy (translated and slightly modified by Sir John Lloyd):

“He was a man who sowed the seed of joy for his people,

Of the right royal lineage of kings.

So lordly his gifts, ‘twas strange

He gave not the moon in Heaven!

Ashen of hue this day is the hand of bounty,

The hand that last year kept the pass of Aberconwy.”

Shortly before Dafydd died, a man named Nicholas de Molis arrived in Wales. Nicholas is virtually lost to modern historiography, but his presence sent a ripple of dread through the Welsh chronicles. He had recently smashed the Basques under Thibaut the Troubadour, King of Navarre, and now King Henry unleashed him on Gwynedd.

Published on January 09, 2020 04:13

January 8, 2020

Eight pence equals one hen

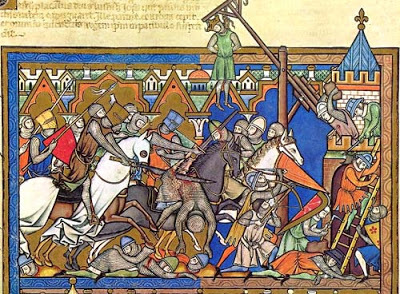

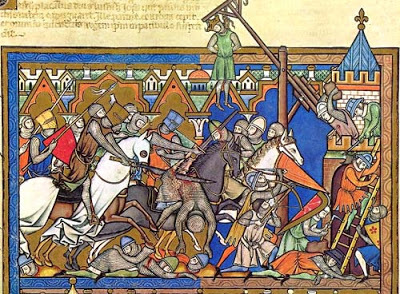

On 23 September 1245 a pitched battle took place - we might call it a mass brawl - over a stranded supply ship from Ireland on the banks of the River Conwy. The ship was loaded with provisions for sale to the army of Henry III, camped at Deganwy, but it had run aground on the Welsh side of the river.

Seeing this, the Welsh rushed down from the heights to grab the supplies as the boat lay on dry ground. Henry sent three hundred Welsh borderers, some crossbowmen and a band of knights to stop them. The Welsh retreated to the mountains and woods, pursued by the king’s men. Some of the fugitives were killed, but then the pursuers stopped to plunder the Cistercian abbey of Aberconwy.

This gave the Welsh time to rally. They ‘rushed with noisy shouts’ upon the king’s men, who were laden with goodies taken from the abbey. Now it was their turn to flee in panic; many were slaughtered in the rout or drowned in the river. Among the casualties were four knights, Alan Bucel, Adam Moia, Geoffrey Sturmy and a Gascon crossbowman named Raymond, who had evidently risen from low birth only to be struck down in North Wales. Raymond was a favourite of Henry’s, who used to make ‘great sport’ of him.

At this point the war got really nasty. Some of the English knights were taken prisoner, and soon afterwards the Welsh learned that Henry’s men had killed some Welsh captives, including a nobleman named Naveth son of Odo. In revenge they dragged their prisoners to the banks of the Conwy, tore them to pieces and threw the body parts into the river, in full sight of the English army on the other side.

The Welsh launched a second attack on the stranded boat, now defended by Walter Bisset and his men. Fighting raged on until midnight, until the sea rose and caused the ship to roll. At this the Welsh withdrew again, only to come back in the morning to find the English had abandoned ship. They promptly seized the sixty casks of wine aboard and made off with them.

Starving and desperate, King Henry’s men were reduced to a state of feral savagery. They threw themselves upon the Welsh, slaughtered and decapitated a hundred of them, and brought the reeking heads back into camp to claim the customary bounty of twopence per head. Thanks to the lack of supplies, one chicken inside the English camp now cost eightpence: thus, four Welsh lives bought one hen. Food supplies continued to dwindle, and men and horses died in droves.

Seeing this, the Welsh rushed down from the heights to grab the supplies as the boat lay on dry ground. Henry sent three hundred Welsh borderers, some crossbowmen and a band of knights to stop them. The Welsh retreated to the mountains and woods, pursued by the king’s men. Some of the fugitives were killed, but then the pursuers stopped to plunder the Cistercian abbey of Aberconwy.

This gave the Welsh time to rally. They ‘rushed with noisy shouts’ upon the king’s men, who were laden with goodies taken from the abbey. Now it was their turn to flee in panic; many were slaughtered in the rout or drowned in the river. Among the casualties were four knights, Alan Bucel, Adam Moia, Geoffrey Sturmy and a Gascon crossbowman named Raymond, who had evidently risen from low birth only to be struck down in North Wales. Raymond was a favourite of Henry’s, who used to make ‘great sport’ of him.

At this point the war got really nasty. Some of the English knights were taken prisoner, and soon afterwards the Welsh learned that Henry’s men had killed some Welsh captives, including a nobleman named Naveth son of Odo. In revenge they dragged their prisoners to the banks of the Conwy, tore them to pieces and threw the body parts into the river, in full sight of the English army on the other side.

The Welsh launched a second attack on the stranded boat, now defended by Walter Bisset and his men. Fighting raged on until midnight, until the sea rose and caused the ship to roll. At this the Welsh withdrew again, only to come back in the morning to find the English had abandoned ship. They promptly seized the sixty casks of wine aboard and made off with them.

Starving and desperate, King Henry’s men were reduced to a state of feral savagery. They threw themselves upon the Welsh, slaughtered and decapitated a hundred of them, and brought the reeking heads back into camp to claim the customary bounty of twopence per head. Thanks to the lack of supplies, one chicken inside the English camp now cost eightpence: thus, four Welsh lives bought one hen. Food supplies continued to dwindle, and men and horses died in droves.

Published on January 08, 2020 12:05

In cold and nakedness

In late August 1245 Henry III arrived at Deganwy after a slow march from Chester, hampered by Welsh guerilla attacks and a large supply train. While his engineers set about refortifying the castle, the king’s soldiers camped on the exposed heights.

On 24 September one of Henry’s nobles (which one isn’t stated) sent a letter to his friends in England. Matthew Paris happened to include a copy of the letter in his Chronica Majora, and the text supplies an extremely rare first-hand account of warfare in medieval Wales. The correspondent makes it sound like a thirteenth century version of the Eastern front in World War II. He describes the wretched state of the army, devoid of supplies and winter gear:

“We are dwelling around it [Deganwy] in tents, employed in watchings, fastings, and prayers, and admidst cold and nakedness. In watchings, through fear of the Welsh attacking us by night; in fastings, on account of a deficiency of provisions, for a farthing loaf now costs five pence; in prayers, that we may soon return home safe and uninjured; and we are oppressed by cold and nakedness, because our houses are of canvas, and we are without winter clothing.”

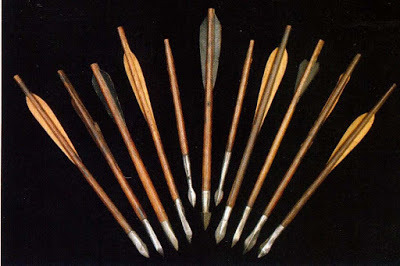

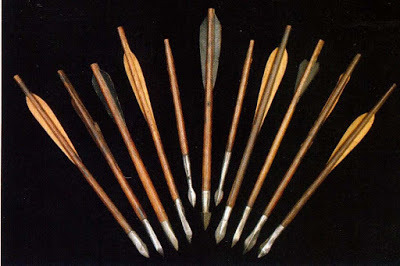

Henry’s commissariat had started to break down early in the month. On 6 September he ordered that supplies were to be sent from Chester even on a Sunday, and that he would pay for them as soon as he could. On the following day he ordered John Lestrange at Chester to buy fifteen wagonloads of iron and steel and send them by the first available ships to Deganwy. Another 15,000 crossbow bolts were to be sent from St Briavels to Chester and then shipped to Deganwy. On 20 September compensation was paid out to to drivers who had lost their carts and horses in the king’s service, and six days later Henry ordered another massive supply of 30,000 crossbow bolts to be sent to Deganwy “with all possible speed, by day and by night”.

Increasing Welsh pressure meant that supplies could no longer be sent to the army by land. The king had predicted this emergency in June, when he ordered the justiciar of Ireland to prepare all the galleys he had for the king’s expedition into Wales. The Irish navigators were not up to the task: it seems just one vessel made it through, only to ground on a sandbank on the Welsh side of the River Conwy. The stranded vessel became the focal point of the only pitched battle of the war.

On 24 September one of Henry’s nobles (which one isn’t stated) sent a letter to his friends in England. Matthew Paris happened to include a copy of the letter in his Chronica Majora, and the text supplies an extremely rare first-hand account of warfare in medieval Wales. The correspondent makes it sound like a thirteenth century version of the Eastern front in World War II. He describes the wretched state of the army, devoid of supplies and winter gear:

“We are dwelling around it [Deganwy] in tents, employed in watchings, fastings, and prayers, and admidst cold and nakedness. In watchings, through fear of the Welsh attacking us by night; in fastings, on account of a deficiency of provisions, for a farthing loaf now costs five pence; in prayers, that we may soon return home safe and uninjured; and we are oppressed by cold and nakedness, because our houses are of canvas, and we are without winter clothing.”

Henry’s commissariat had started to break down early in the month. On 6 September he ordered that supplies were to be sent from Chester even on a Sunday, and that he would pay for them as soon as he could. On the following day he ordered John Lestrange at Chester to buy fifteen wagonloads of iron and steel and send them by the first available ships to Deganwy. Another 15,000 crossbow bolts were to be sent from St Briavels to Chester and then shipped to Deganwy. On 20 September compensation was paid out to to drivers who had lost their carts and horses in the king’s service, and six days later Henry ordered another massive supply of 30,000 crossbow bolts to be sent to Deganwy “with all possible speed, by day and by night”.

Increasing Welsh pressure meant that supplies could no longer be sent to the army by land. The king had predicted this emergency in June, when he ordered the justiciar of Ireland to prepare all the galleys he had for the king’s expedition into Wales. The Irish navigators were not up to the task: it seems just one vessel made it through, only to ground on a sandbank on the Welsh side of the River Conwy. The stranded vessel became the focal point of the only pitched battle of the war.

Published on January 08, 2020 08:02

January 7, 2020

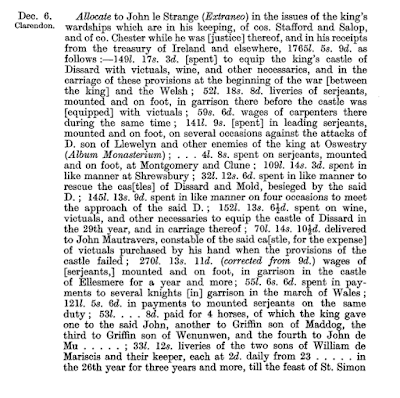

A great hosting against the Welsh

In the spring and summer of 1245, while Henry III prepared to invade North Wales, a string of payments was made to his garrisons in the Marches. On 12 May the sheriff of Hereford was ordered to transport 6000 crossbow bolts from St Briavels to Monmouth to help supply the army based at Buellt. Later in the months arrears of wages were paid out at Montgomery and other places. These included money for loss of horses, implying the Marchers were under orders to mount constant forays against the allies of Prince Dafydd.

Montgomery castle

Montgomery castle

For instance, at the end of February 1245 a pitched battle was fought near Montgomery, in which three hundred of Dafydd’s men were killed. This engagement is reflected in the payment of fifty marks (£33 6s 8d) sent from Deganwy to the garrison at Montgomery for ‘the horses lately lost on service at Montgomery’. Thus, in this case, it is possible to tally the chronicle accounts of a battle with the records of the administration. If only it was possible in all cases.

Not that the administration was perfect. On 18 June 1245 the king ordered a payment of four marks to a squad of royal sergeants for guarding Gruffydd ap Llywelyn and other Welsh prisoners in the Tower of London for forty days. This was an unfortunate hiccup, since Gruffydd had died the previous March when he fell off the Tower trying to escape from prison. Presumably his guards were happy to take the cash for a job they hadn’t been doing.

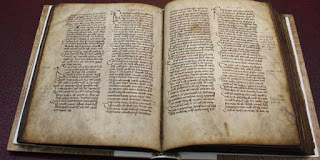

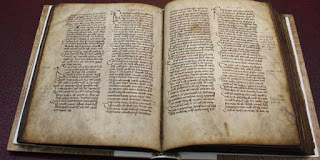

The annals of Connacht

The annals of Connacht

For his great effort in Wales, Henry also turned to the resources of Ireland. An Irish lord of Connacht, Fedlimid mac Cathail Chrobdeirg, was summoned to join the king’s host at Deganwy. This was recorded in the Annals of Connacht (translated from the Gaelic):

“The King of the English made a great hosting against the Welsh. They encamped at Cannock Castle, and the King sent legates bearing letters to the Irish Galls and to Fedlimid mac Cathail Chrobdeirg, bidding them to attend him, to conquer the Welsh. Then the Justiciar and the Irish Galls repaired to the King, and Fedlimid O Conchobair with a great army went to the help of the King in Wales.”

Montgomery castle

Montgomery castleFor instance, at the end of February 1245 a pitched battle was fought near Montgomery, in which three hundred of Dafydd’s men were killed. This engagement is reflected in the payment of fifty marks (£33 6s 8d) sent from Deganwy to the garrison at Montgomery for ‘the horses lately lost on service at Montgomery’. Thus, in this case, it is possible to tally the chronicle accounts of a battle with the records of the administration. If only it was possible in all cases.

Not that the administration was perfect. On 18 June 1245 the king ordered a payment of four marks to a squad of royal sergeants for guarding Gruffydd ap Llywelyn and other Welsh prisoners in the Tower of London for forty days. This was an unfortunate hiccup, since Gruffydd had died the previous March when he fell off the Tower trying to escape from prison. Presumably his guards were happy to take the cash for a job they hadn’t been doing.

The annals of Connacht

The annals of ConnachtFor his great effort in Wales, Henry also turned to the resources of Ireland. An Irish lord of Connacht, Fedlimid mac Cathail Chrobdeirg, was summoned to join the king’s host at Deganwy. This was recorded in the Annals of Connacht (translated from the Gaelic):

“The King of the English made a great hosting against the Welsh. They encamped at Cannock Castle, and the King sent legates bearing letters to the Irish Galls and to Fedlimid mac Cathail Chrobdeirg, bidding them to attend him, to conquer the Welsh. Then the Justiciar and the Irish Galls repaired to the King, and Fedlimid O Conchobair with a great army went to the help of the King in Wales.”

Published on January 07, 2020 02:27

January 6, 2020

More grain and oats

In 1245, after the defeat of the Marchers, Henry III was obliged to come to Wales again. His first measure was to release Owain Goch, eldest son of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, and send him to North Wales in the hope he might draw away some of the supporters of Owain’s uncle, Prince Dafydd.

A reconstruction of Deganwy castle

A reconstruction of Deganwy castle

Away from chronicles, most of the detail of these wars come from the records of the English state; from about 1200 onwards the government in England started to generate enormous amounts of documentation, much of which has survived. This allows us to piece together the details of supply and logistics and the movements of the king’s army (etcetera), but very little from the Welsh side of things.

Dafydd’s plan, to judge from the difficulties Henry encountered, was to cut English supply lines and harry the invaders as they pushed deeper into Welsh territory. Henry’s plan was to march to Deganwy and refortify the castle there, to help protect the royal castle at Dyserth and shield the northern coast from Welsh attacks.

Robin Hood

Robin Hood

Things went awry for Henry from the start. When he arrived at Chester, where the army was due to muster, he realised not enough food was coming in. On the 12 he wrote to the Sheriff of Nottingham, demanding more grain and oats to be sent to the army, along with as much wine as possible. The sheriff - possibly too busy chasing Robin Hood - apparently ignored the king, for on 25 August Henry wrote to him again in no uncertain terms:

“Know that although the expedition was happily begun by us, much is now lacking in the supplies sent to our army in Wales and we may have to shamefully abandon our army if assistance in supplies does not come to us, because you and our other sheriffs have failed us in this.”

Henry threatened to disinherit all the sheriffs in England unless they got their backsides into gear. He also tried to ease the supply situation by staggering the deployment of his forces: one army was sent to Deheubarth and Glamorgan, another from Brecon to Shrewsbury. Yet another was paid at Buellt, suggesting there were four royal armies operating independently of each other in Wales.

A reconstruction of Deganwy castle

A reconstruction of Deganwy castleAway from chronicles, most of the detail of these wars come from the records of the English state; from about 1200 onwards the government in England started to generate enormous amounts of documentation, much of which has survived. This allows us to piece together the details of supply and logistics and the movements of the king’s army (etcetera), but very little from the Welsh side of things.

Dafydd’s plan, to judge from the difficulties Henry encountered, was to cut English supply lines and harry the invaders as they pushed deeper into Welsh territory. Henry’s plan was to march to Deganwy and refortify the castle there, to help protect the royal castle at Dyserth and shield the northern coast from Welsh attacks.

Robin Hood

Robin HoodThings went awry for Henry from the start. When he arrived at Chester, where the army was due to muster, he realised not enough food was coming in. On the 12 he wrote to the Sheriff of Nottingham, demanding more grain and oats to be sent to the army, along with as much wine as possible. The sheriff - possibly too busy chasing Robin Hood - apparently ignored the king, for on 25 August Henry wrote to him again in no uncertain terms:

“Know that although the expedition was happily begun by us, much is now lacking in the supplies sent to our army in Wales and we may have to shamefully abandon our army if assistance in supplies does not come to us, because you and our other sheriffs have failed us in this.”

Henry threatened to disinherit all the sheriffs in England unless they got their backsides into gear. He also tried to ease the supply situation by staggering the deployment of his forces: one army was sent to Deheubarth and Glamorgan, another from Brecon to Shrewsbury. Yet another was paid at Buellt, suggesting there were four royal armies operating independently of each other in Wales.

Published on January 06, 2020 08:47

Faith and Peace...or not

The Order of the Faith and Peace or Order of the Sword was a military order founded in Gascony in the mid-thirteenth century. It is first mentioned by Pope Gregory IX in 1231 in a letter to the master of the order:

“magistro militiae ordinis sancti Jacobi ejusque fratribus tam presentibus quam futuris ad defensionem fidei et pacis in Guasconia constitutis.”

(the master of the military order of Saint James and his brothers present and future constituted for the defence of the faith and of the peace in Gascony.)

The order was founded by the Archbishop of the province of Auch. Its stated purpose was not to fight heresy, but keep the peace. Somewhat ironically, the order’s first major patron was Gaston VII de Montcada (1225-1290) Viscount de Béarn, one of the most belligerent and grasping noblemen in the duchy.

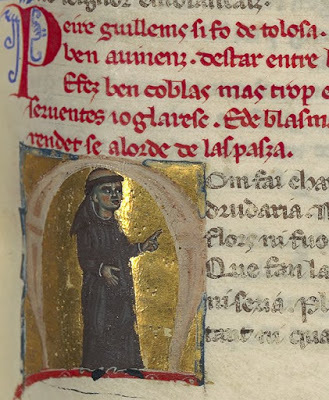

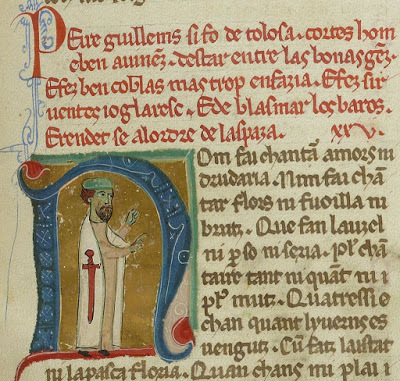

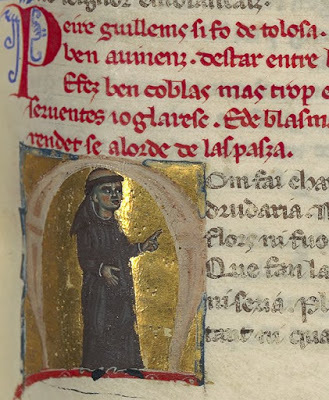

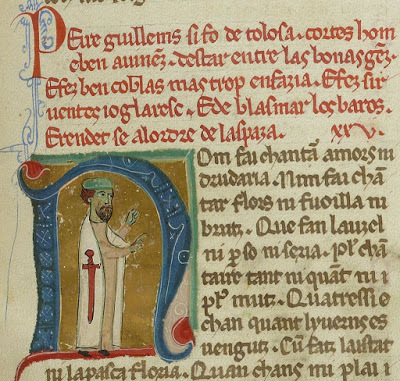

The idea behind a military order that acted as a police force was a good one, but doomed to fail since the Gascon gentry had no interest in peace. If they weren’t fighting the French or the English, they were predating on each other. The order is mentioned in the only surviving ‘sirventes’ - Occitan lyric poetry - composed by Peire Guillem de Tolosa. This took the form of a duet between Peire and his co-writer, the contemporary Italian poet, Sordello de Goito.

Peire apparently started out as a monk in Toulouse, but according to the poem he chose to leave his monastery and enter the “Order of Spaza” or Order of the Sword. Peire is depicted twice in an illustrated manuscript; once in his early life as a monk, and then in later life as a Knight of Santiago. The Order of Santiago in Spain was the parent house of the Order of the Sword, and it appears the knights of both wore the same “uniform”.

“magistro militiae ordinis sancti Jacobi ejusque fratribus tam presentibus quam futuris ad defensionem fidei et pacis in Guasconia constitutis.”

(the master of the military order of Saint James and his brothers present and future constituted for the defence of the faith and of the peace in Gascony.)

The order was founded by the Archbishop of the province of Auch. Its stated purpose was not to fight heresy, but keep the peace. Somewhat ironically, the order’s first major patron was Gaston VII de Montcada (1225-1290) Viscount de Béarn, one of the most belligerent and grasping noblemen in the duchy.

The idea behind a military order that acted as a police force was a good one, but doomed to fail since the Gascon gentry had no interest in peace. If they weren’t fighting the French or the English, they were predating on each other. The order is mentioned in the only surviving ‘sirventes’ - Occitan lyric poetry - composed by Peire Guillem de Tolosa. This took the form of a duet between Peire and his co-writer, the contemporary Italian poet, Sordello de Goito.

Peire apparently started out as a monk in Toulouse, but according to the poem he chose to leave his monastery and enter the “Order of Spaza” or Order of the Sword. Peire is depicted twice in an illustrated manuscript; once in his early life as a monk, and then in later life as a Knight of Santiago. The Order of Santiago in Spain was the parent house of the Order of the Sword, and it appears the knights of both wore the same “uniform”.

Published on January 06, 2020 04:22

January 5, 2020

Whoever chooses may take him...

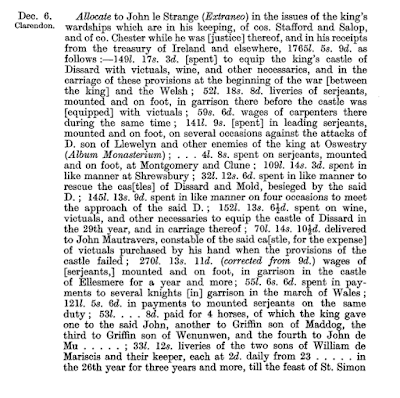

Over the winter of 1244-45 warfare continued to rage in Wales. A remarkably complete account survives of the expenses of John Lestrange, justice of Chester, in his efforts against Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn. The account lists the payments made to mounted and foot serjeants in rescuing the castles of Dyserth and Mold from Dafydd, implying the prince focused his efforts on these two strongholds. He had hoped to gain Mold via arbitration with Henry III in 1241, but was disappointed.

Henry managed to keep his garrisons in Wales supplied over the winter, and the conflict started to drift into stalemate. Then, on 5 February 1245, the Welsh gained a victory over the southern Marcher army, led by Herbert Fitz Matthew. On the night before the battle, Herbert is said to have experienced a premonition of his death, and in the morning said to his comrades:

“Many times have I indulged in the use of arms, and exposed myself to the dangers of war, but today, as I sincerely believe, my oft-repeated feats of arms will be brought to a final close.”

After this less than inspiring speech, Herbert led his men into a narrow pass between Margam and Aberafan near Baglan castle. The local Welsh were lying in wait, and from the crags hurled stones and javelins down at the English as they struggled through the pass. Herbert was buried under a mass of rock, and his men halted to bury him on the spot.

Another version of the tale says that Herbert was only knocked off his horse, and the Welsh came down to capture him. They fell to arguing over who should take him prisoner, until one of them stabbed him from behind and declared:

“Now, whoever chooses may take him.”

His body was stripped naked and only recognised the next day by an emerald ring. Shortly afterwards the fortunes of war swung the other way, and three hundred of Prince Dafydd’s men were slaughtered in an ambush near Montgomery. Dafydd stuck to his task and finally captured Mold castle on 28 March 1245. The constable, Roger Monthaut, had escaped before the castle fell, and both sides now took to butchering innocents, with neither party showing any respect to age, sex or rank.

Henry managed to keep his garrisons in Wales supplied over the winter, and the conflict started to drift into stalemate. Then, on 5 February 1245, the Welsh gained a victory over the southern Marcher army, led by Herbert Fitz Matthew. On the night before the battle, Herbert is said to have experienced a premonition of his death, and in the morning said to his comrades:

“Many times have I indulged in the use of arms, and exposed myself to the dangers of war, but today, as I sincerely believe, my oft-repeated feats of arms will be brought to a final close.”

After this less than inspiring speech, Herbert led his men into a narrow pass between Margam and Aberafan near Baglan castle. The local Welsh were lying in wait, and from the crags hurled stones and javelins down at the English as they struggled through the pass. Herbert was buried under a mass of rock, and his men halted to bury him on the spot.

Another version of the tale says that Herbert was only knocked off his horse, and the Welsh came down to capture him. They fell to arguing over who should take him prisoner, until one of them stabbed him from behind and declared:

“Now, whoever chooses may take him.”

His body was stripped naked and only recognised the next day by an emerald ring. Shortly afterwards the fortunes of war swung the other way, and three hundred of Prince Dafydd’s men were slaughtered in an ambush near Montgomery. Dafydd stuck to his task and finally captured Mold castle on 28 March 1245. The constable, Roger Monthaut, had escaped before the castle fell, and both sides now took to butchering innocents, with neither party showing any respect to age, sex or rank.

Published on January 05, 2020 06:04

January 4, 2020

To control the Welsh

“It is not easy to control the Welsh except through one of their own race.” This is from a letter addressed to John Monmouth, Justiciar of South Wales, from Nichola Fitz Martin of Cemais and other Marcher lords in September 1244.

The context of the letter is the war between Henry III and Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn. Over the summer the Marchers invaded the lands of Maredudd ab Owain in Cardiganshire, only to find there was nothing to plunder. This implies that Maredudd had stripped his lands of goods and livestock etc to induce the Marchers to parley.

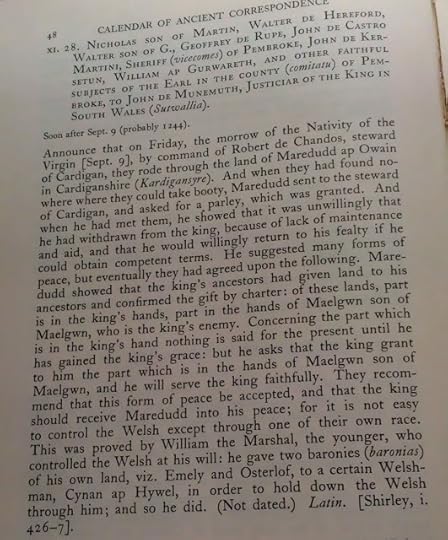

The Marshal arms

The Marshal arms

They agreed to talk. Maredudd stated that he had only left the king’s fealty and joined Dafydd because of lack of ‘maintenance and aid’ i.e. the crown wasn’t sending him enough money. After some haggling, it was agreed that Maredudd would come back to the king in exchange for land originally granted to him by Henry’s ancestors; these included the lands of Maelgwn ap Maelgwn, the king’s enemy, who would be disinherited in favour of Maredudd.

Pembroke Castle

Pembroke Castle

The Marchers recommended this form of peace, since it was easier to control the Welsh via a friendly Welsh prince: we could call this a divide and rule policy. They cited as an example the career of William Marshal junior, son of the famous Earl of Pembroke, who had ‘controlled the Welsh at his will’. Marshal did this by granting two manors to one Cynan ap Hywel, a Welsh noble, in order to hold down the Welsh through him. And, the letter concludes, ‘so he did’.

The context of the letter is the war between Henry III and Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn. Over the summer the Marchers invaded the lands of Maredudd ab Owain in Cardiganshire, only to find there was nothing to plunder. This implies that Maredudd had stripped his lands of goods and livestock etc to induce the Marchers to parley.

The Marshal arms

The Marshal armsThey agreed to talk. Maredudd stated that he had only left the king’s fealty and joined Dafydd because of lack of ‘maintenance and aid’ i.e. the crown wasn’t sending him enough money. After some haggling, it was agreed that Maredudd would come back to the king in exchange for land originally granted to him by Henry’s ancestors; these included the lands of Maelgwn ap Maelgwn, the king’s enemy, who would be disinherited in favour of Maredudd.

Pembroke Castle

Pembroke CastleThe Marchers recommended this form of peace, since it was easier to control the Welsh via a friendly Welsh prince: we could call this a divide and rule policy. They cited as an example the career of William Marshal junior, son of the famous Earl of Pembroke, who had ‘controlled the Welsh at his will’. Marshal did this by granting two manors to one Cynan ap Hywel, a Welsh noble, in order to hold down the Welsh through him. And, the letter concludes, ‘so he did’.

Published on January 04, 2020 07:42

Prince Dafydd and Henry III

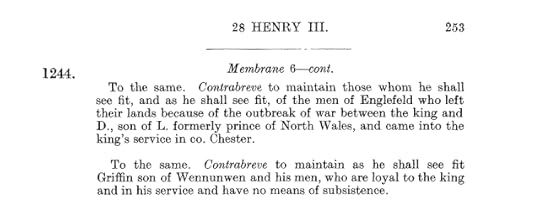

Away from the tabloid waffle of Matthew Paris, Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn’s war against Henry III in 1245 is quite well-documented. In June John Lestrange, justice of Chester, wrote to the king:

“If you cannot send an army to Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn’s district in the March, send forty or fifty knights with sergeants thither, so that the Welsh who are loyal may see that help is forthcoming, and lest they should cease to be loyal. Prince Dafydd has a strong force between Chester and Diserth castle, and Lestrange cannot without a great force approach the castle to stock it with supplies. He has sufficient money for the moment, but there are not in the three counties thirty men who have horses for use in necessity.”

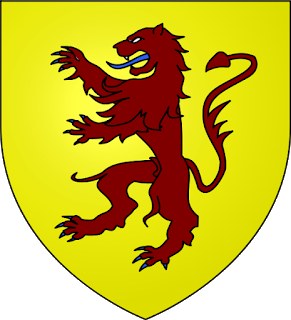

The arms of Powys Wenwynwyn

The arms of Powys Wenwynwyn

Henry’s response was to purchase one horse each for his captains in Wales. These were named as John Lestrange himself, John Monmouth, Gruffydd ap Madog of Bromfield and Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn. The two Gruffydds, therefore, continued in their bitter opposition towards Dafydd. In the south another Marcher army under Robert Chandos and Nicholas Fitz Martin invaded the lands of Maredudd ab Owain of Ceredigion. Maredudd, who would later win the battle of Cymerau, opened talks with the Marchers. He stated his willingness to come to the king’s peace, provided he was given the lands of Maelgwn Fychan, one of his neighbours. This was granted.

In the meantime, Henry took steps to ensure the security of the sons of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, who were in his custody. On 16 July he ordered the sheriff of London to send Owain Goch and his fellows, prisoners in the Tower, to the custody of John Lestrange. Lestrange was then ordered to provide food and clothing for Rhodri, Gruffydd’s third son, held in Chester prison for safe keeping.

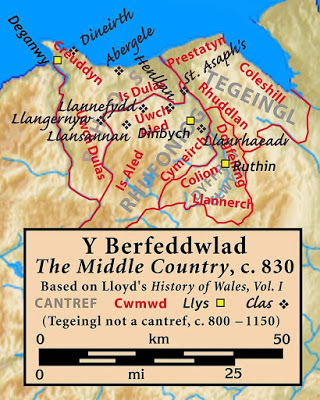

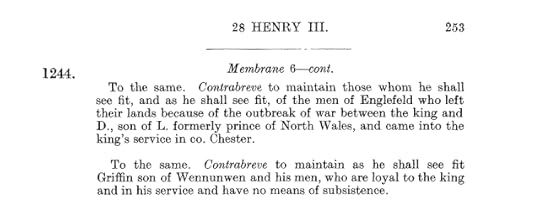

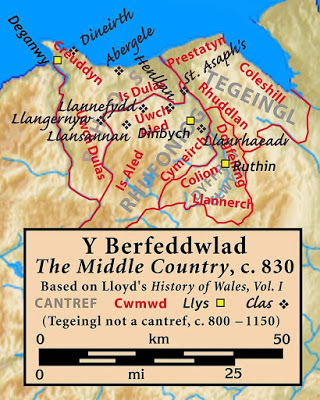

Further orders reveal the split loyalties in Wales. Again on 16 July, Henry ordered provison to be made for the men of Englefield or Tegeingl in northeast Wales, who had abandoned Prince Dafydd and crossed the border to join the king’s army. He also told Lestrange to maintain Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn and his men, who had nothing for their subsistence.

“If you cannot send an army to Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn’s district in the March, send forty or fifty knights with sergeants thither, so that the Welsh who are loyal may see that help is forthcoming, and lest they should cease to be loyal. Prince Dafydd has a strong force between Chester and Diserth castle, and Lestrange cannot without a great force approach the castle to stock it with supplies. He has sufficient money for the moment, but there are not in the three counties thirty men who have horses for use in necessity.”

The arms of Powys Wenwynwyn

The arms of Powys WenwynwynHenry’s response was to purchase one horse each for his captains in Wales. These were named as John Lestrange himself, John Monmouth, Gruffydd ap Madog of Bromfield and Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn. The two Gruffydds, therefore, continued in their bitter opposition towards Dafydd. In the south another Marcher army under Robert Chandos and Nicholas Fitz Martin invaded the lands of Maredudd ab Owain of Ceredigion. Maredudd, who would later win the battle of Cymerau, opened talks with the Marchers. He stated his willingness to come to the king’s peace, provided he was given the lands of Maelgwn Fychan, one of his neighbours. This was granted.

In the meantime, Henry took steps to ensure the security of the sons of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, who were in his custody. On 16 July he ordered the sheriff of London to send Owain Goch and his fellows, prisoners in the Tower, to the custody of John Lestrange. Lestrange was then ordered to provide food and clothing for Rhodri, Gruffydd’s third son, held in Chester prison for safe keeping.

Further orders reveal the split loyalties in Wales. Again on 16 July, Henry ordered provison to be made for the men of Englefield or Tegeingl in northeast Wales, who had abandoned Prince Dafydd and crossed the border to join the king’s army. He also told Lestrange to maintain Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn and his men, who had nothing for their subsistence.

Published on January 04, 2020 01:02

January 3, 2020

Longsword review

A nice review of the latest Longsword tale from a fellow author, Joe Corso:

"I have made it a practice to read David Pilling's books concerning historical fiction. The King's Rebels was as good as his other books, full of intrigue and spycraft. If you enjoy ancient books on the Roman Legions, or action books written about ancient European history you will enjoy this book. Another great job by Pilling."

Joe Corso author of Lafitte's Treasure

Longsword (V): The King's rebels on Amazon US

"I have made it a practice to read David Pilling's books concerning historical fiction. The King's Rebels was as good as his other books, full of intrigue and spycraft. If you enjoy ancient books on the Roman Legions, or action books written about ancient European history you will enjoy this book. Another great job by Pilling."

Joe Corso author of Lafitte's Treasure

Longsword (V): The King's rebels on Amazon US

Published on January 03, 2020 03:40