David Pilling's Blog, page 39

December 16, 2019

Kissing cousins (2)

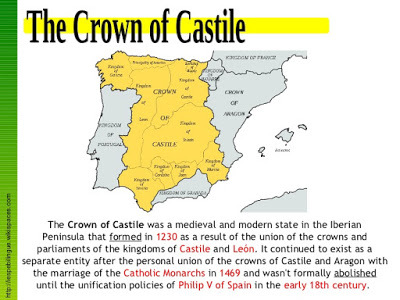

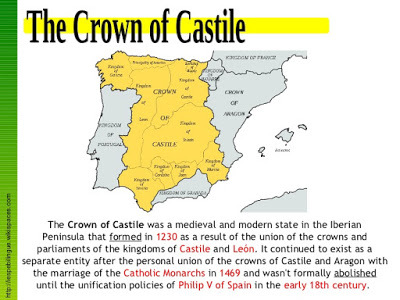

In the mid-1270s the contest for control of Navarre intensified. Technically the French had grabbed it, but the kings of Aragon and Castile weren’t about to roll over to have their tummies tickled.

Alfonso of Castile

Alfonso of Castile

King Alfonso of Castile moved first, and asked his brother-in-law Edward I of England for military aid against the French. Edward replied that any help he might give must be subject to his feudal obligations and fealty to the king of France; he also took the opportunity to remind Alfonso of his own hereditary rights to certain castles and towns in Navarre. The king of England appeared to imply that he would not risk anything for nothing, and any military aid for Castle would come with a large price tag attached.

The situation changed in May 1275, when Alfonso’s eldest son Ferdinand de la Cerda - Ferdinand ‘of the bristle’, named after his full head of hair - died unexpectedly. His younger brother Sancho was hailed by the cortes of Castile as Alfonso’s heir, even though the king wanted his grandsons by Ferdinand to succeed him. These grandsons were also the nephews of Philip III of France, who took up their cause. Philip collected a great army at Sauveterre in southern Gascony, a development Edward must have regarded with some alarm: he was the king-duke of Gascony, after all, and it was indelicate of Philip to raise an army on English territory without asking some form of permission, even if Edward was his vassal. Edward was also faced with the unpleasant prospect of being summoned to do military service by the French against his own in-laws of Castile: King Alfonso was brother to Edward’s wife, Eleanor.

The necessity of military service overseas explains why Edward fixed his campaign against Prince Llywelyn in Wales for the summer of 1277 instead of autumn 1276. On 7 November 1276, five days before he formally denounced Llywelyn as a rebel, Edward wrote to Philip expressing his regret that peace with Castile was impossible. He also declared that, in view of the danger to Christendom, he had entrusted military operations in Wales and Ireland to others so he could join Philip for the invasion of Castile.

Thus, if the Franco-Castilian war had gone ahead, Llywelyn might have been spared a crushing defeat. Unfortunately Philip III was not a great organiser, and forgot to arrange any food or supplies for the army gathered at Sauveterre. As a result the army had to be immediately disbanded and Philip scuttled back to Paris, followed by howls of laughter from the direction of Castile.

Alfonso of Castile

Alfonso of CastileKing Alfonso of Castile moved first, and asked his brother-in-law Edward I of England for military aid against the French. Edward replied that any help he might give must be subject to his feudal obligations and fealty to the king of France; he also took the opportunity to remind Alfonso of his own hereditary rights to certain castles and towns in Navarre. The king of England appeared to imply that he would not risk anything for nothing, and any military aid for Castle would come with a large price tag attached.

The situation changed in May 1275, when Alfonso’s eldest son Ferdinand de la Cerda - Ferdinand ‘of the bristle’, named after his full head of hair - died unexpectedly. His younger brother Sancho was hailed by the cortes of Castile as Alfonso’s heir, even though the king wanted his grandsons by Ferdinand to succeed him. These grandsons were also the nephews of Philip III of France, who took up their cause. Philip collected a great army at Sauveterre in southern Gascony, a development Edward must have regarded with some alarm: he was the king-duke of Gascony, after all, and it was indelicate of Philip to raise an army on English territory without asking some form of permission, even if Edward was his vassal. Edward was also faced with the unpleasant prospect of being summoned to do military service by the French against his own in-laws of Castile: King Alfonso was brother to Edward’s wife, Eleanor.

The necessity of military service overseas explains why Edward fixed his campaign against Prince Llywelyn in Wales for the summer of 1277 instead of autumn 1276. On 7 November 1276, five days before he formally denounced Llywelyn as a rebel, Edward wrote to Philip expressing his regret that peace with Castile was impossible. He also declared that, in view of the danger to Christendom, he had entrusted military operations in Wales and Ireland to others so he could join Philip for the invasion of Castile.

Thus, if the Franco-Castilian war had gone ahead, Llywelyn might have been spared a crushing defeat. Unfortunately Philip III was not a great organiser, and forgot to arrange any food or supplies for the army gathered at Sauveterre. As a result the army had to be immediately disbanded and Philip scuttled back to Paris, followed by howls of laughter from the direction of Castile.

Published on December 16, 2019 08:28

Whose right is it anyway?

The full text of the Treaty of Paris in 1259, typed out by me over the course of three days. The treaty is very long, complicated and dull, and I should imagine few of us will have the time or inclination to read through it all, and no wonder.

Even so, this is an extremely important document and key to understanding the root of the Hundred Years War. Like most medieval treaties of this type - the Treaty of Montgomery would be an obvious comparison - the terms are often vague and shifty, and leave room for all manner of interpretation. Even if it was originally drawn up in good faith, the lawyers of the French court spent the following decades shamelessly exploiting gaps and vagaries in the text.

For instance, one clause states that ‘let what is right be done’ concerning the county of Bigorre. Technically this land was ceded to the king of England and his heirs, but it is no coincidence that Bigorre was the first territory to be effectively confiscated by Philip le Bel in the 1280s; any protests from Edward I foundered on the ambivalence of the clause in the original treaty. What did ‘right’ mean in this context, and whose right was it? That was for lawyers to decide, and while they spent years stroking their chins over the matter - and drawing massive salaries - the land of Bigorre remained a French possession.

“Henry, by God’s grace king of England, lord of Ireland and duke of Aquitaine. We make known to all and to all who are to come that we by God’s will have made peace with our dear cousin, the noble king Louis of France in this manner: namely that he give us and our heirs and our successors all the right that he has and holds in these three bishoprics and in the cities, namely, of Limoges, Cathors and Périgueux, in fief and domain, saving the homage of his brothers and if they hold anything there for which they are his man, and saving the things that he cannot alienate owing to letters granted by him or his ancestors, which things he must take steps to acquire in good faith from those who hold these things so that we may have them within a year next All Saints day or give us a suitable exchange, in the opinion of men standing nominated by either side the most suitable for the interests of both parties.- The aforesaid king of France shall also give us in money each year the value of the land of the Agenais according to the assessment to be made of it on the proper value of the land by men of standing nominated on either side, and payment shall be made at Paris at the Temple each year, half on the quinzaine of the Ascension and the other half of the quinzaine of All Saints. And should it happen that this land escheats from the countess Joan of Poitiers to the king of France or his heirs, he or his heirs shall be bound to surrender it to us or our heirs and when the land has been surrendered they shall be relieved of the payment. And if it comes in domain to us, the king of France shall not be bound to render this payment. And if it is decided by the court of the king of France that, to have the land of the Agenais, we ought to put down or hand over some money as security, the king of France shall return this money or we shall hold and have the payment until we have had what we have put down for this security.- Again, it shall be enquired in good faith and without impediment, at our request, by men of standing of either side chosen for the purpose, whether the land that the count of Poitiers holds in Quercy on behalf of his wife was given or granted by the king of England with the land of the Agenais as marriage portion or as security, either wholly or in part, to his sister, who was the mother of the last count Raymond of Toulouse. And if it is found that it had so been and this land escheats to him or his heirs on the death of the countess of Poitiers, he shall give it to us or our heirs, and if it escheats to another and it be found by this inquest however that it had been given or granted in the way said above, after the death of the countess of Poitiers, he shall give the fief to us and our heirs, saving the homage of his brothers, if they hold anything there, while they live.- Again, after the death of the count of Poitiers, the king of France or his heirs, kings of France, shall give to us and our heirs the land that the count of Poitiers holds then in Saintonge beyond the R.Charente in fief and in domain that are beyond the Charente, if it escheats to him or his heirs. And if it does not escheat to him, he shall take steps in good fashion to acquire it, by exchange or otherwise, so that we or our heirs shall have it, or he shall give us, in the opinion of men of standing who shall be nominated by either side, a suitable exchange. And for what he shall give us and our heirs in fief and in domain, we and our heirs will do him and his heirs, kings of France, liege homage, and also for Bordeaux, for Bayonne and for Gascony, and for all the land that we hold beyond the English Channel in fief and in domain, and for the islands, if there are any, that we hold that are of the kingdom of France, and we will hold of him as of a peer of France and as duke of Aquitaine. And for all these things aforesaid we will do him our appropriate services until it be found what services are due for these things and then we shall be bound to do them just as they have been found. About homage for the county of Bigorre, for Armagnac and for Fezensac let what is right be done about them. And the king of France absolves us if we or our ancestor ever wronged him by holding his fief without doing him homage and without doing his service, and all arrears.- Again, the king of France shall give us what, in the opinion of men of standing who shall be nominated by either side, 500 knights ought to cost to maintain reasonably for two years and shall be bound to pay this money at Paris at the Temple in six payments over the period of two years, namely the first payment, that is to say a sixth, on the quinzaine of next Candlemas, another payment on the quinzaine of the Ascension following and another on the quinzaine of All Saints and likewise with the remaining payments on the following year. And for this the king of France shall give the Temple or the Hospital or both of them together as surety. And we ought not to spend this money except in the service of God or of the church, or for the benefit of the kingdom of England, and this by view of men of standing of the land chosen by the king of England and by the magnates of this land.- And in making this peace we and our two sons have renounced and do renounce completely all claim upon the king of France and his ancestors and his heirs and successors, and his brothers and their heirs and successors, for us and our heirs and successors if we or our ancestors have or ever had any right in things which the king of France holds or ever held, or his ancestors held or hold, namely in the duchy and the whole land of Normandy, in the county and the whole land of Anjou, or Touraine and of Maine, and in the county and the whole land of Poitiers, or elsewhere in any part of the kingdom of France or in the islands, if the king of France or his brothers, or others from them, hold anything of them, and all arrears.- And likewise we have renounced and do renounce, we and our two sons, all claim upon all those who hold anything, by gift, exchange, sale, purchase, elevation or other similar way, from the king of France or from his ancestors or his brothers in the duchy and the whole land of Normandy, in the county and the whole land of Anjou, or Touraine and of Maine, and in the county and the whole land of Poitiers, or elsewhere in any part of the kingdom of France or in the islands aforesaid, saving to us and our heirs our right in the lands for which we ought to have by this peace, as set out above, to do liege homage to the king of France, and saving that we can ask for our right if we believe we have it in the Agenais, and have it there if the court of the king of France decides it, and likewise in respect of Quercy.- And we have pardoned and renounced all claim upon one another and we pardon and renounce all animosity over disputes and wars, all arrears, and all issues which have been had or which could have been had in all the aforesaid things, and all losses and expenses incurred on either side in war or in any other ways.- And so that this peace may be kept firmly and stably, without any infringement, forever, the king of France has had an oath sworn on his soul by his proxies specially appointed for this and his two sons have sworn to keep these things as long as it concerns each of them, and they have bound themselves and their heirs to keep it by their letters pendant. And that we will keep these things we are bound to give the king of France such surety from the knights of the aforesaid lands that he gives us and from the towns as he will require of us.- And the form of the surety for us from the men and towns shall be this: they shall swear that they will give neither counsel nor support nor aid whereby we or our heir may contravene the peace, and if it should happen, which God forbid, that we or our heir should contravene it and be unwilling to make amends on being requested to do so by the king of France or his heir, the king of France, those who have gone surety shall, within three months of being required by him to do so, be bound to help the king of France and his heirs against us and our heirs until this thing is sufficiently amended in the opinion of the court of the king of France. And this surety shall be renewed every ten years at the request of the king of France or his heirs, the kings of France.- And we promise in good faith for ourselves and for our heirs and successors, to the aforesaid king of France and his heirs and successors, loyally and firmly to keep this peace and this composition established between us and the aforesaid king of France and every one of the things aforesaid just as they are contained above, and we promise that we will not contravene them in any way either personally or through another, and that we have not and will not do anything whereby any or all of the aforesaid things, in whole or part, may be less firm. And so that this peace may be kept firmly and stably, without any infringement, forever, we have bounds ourselves and our heirs to this and have had an oath sworn on our soul in our presence by our proxies to keep the peace, just as it is set out and written above, in good faith as long as it concerns us, and not to contravene it either personally or through another.- And in witness of all these things we have made for the king of France these letters pendant, sealed with our seal. - And by special commandment our sons Edward and Edmund have in our presence sworn to keep and hold firmly this peace and all the things which are contained above and not to contravene them either personally and through others.- This was given at London, the Monday before the feast of St Luke the Evangelist in the year of our Lord’s incarnation one thousand two hundred and fifty nine, in the month of October.”

Even so, this is an extremely important document and key to understanding the root of the Hundred Years War. Like most medieval treaties of this type - the Treaty of Montgomery would be an obvious comparison - the terms are often vague and shifty, and leave room for all manner of interpretation. Even if it was originally drawn up in good faith, the lawyers of the French court spent the following decades shamelessly exploiting gaps and vagaries in the text.

For instance, one clause states that ‘let what is right be done’ concerning the county of Bigorre. Technically this land was ceded to the king of England and his heirs, but it is no coincidence that Bigorre was the first territory to be effectively confiscated by Philip le Bel in the 1280s; any protests from Edward I foundered on the ambivalence of the clause in the original treaty. What did ‘right’ mean in this context, and whose right was it? That was for lawyers to decide, and while they spent years stroking their chins over the matter - and drawing massive salaries - the land of Bigorre remained a French possession.

“Henry, by God’s grace king of England, lord of Ireland and duke of Aquitaine. We make known to all and to all who are to come that we by God’s will have made peace with our dear cousin, the noble king Louis of France in this manner: namely that he give us and our heirs and our successors all the right that he has and holds in these three bishoprics and in the cities, namely, of Limoges, Cathors and Périgueux, in fief and domain, saving the homage of his brothers and if they hold anything there for which they are his man, and saving the things that he cannot alienate owing to letters granted by him or his ancestors, which things he must take steps to acquire in good faith from those who hold these things so that we may have them within a year next All Saints day or give us a suitable exchange, in the opinion of men standing nominated by either side the most suitable for the interests of both parties.- The aforesaid king of France shall also give us in money each year the value of the land of the Agenais according to the assessment to be made of it on the proper value of the land by men of standing nominated on either side, and payment shall be made at Paris at the Temple each year, half on the quinzaine of the Ascension and the other half of the quinzaine of All Saints. And should it happen that this land escheats from the countess Joan of Poitiers to the king of France or his heirs, he or his heirs shall be bound to surrender it to us or our heirs and when the land has been surrendered they shall be relieved of the payment. And if it comes in domain to us, the king of France shall not be bound to render this payment. And if it is decided by the court of the king of France that, to have the land of the Agenais, we ought to put down or hand over some money as security, the king of France shall return this money or we shall hold and have the payment until we have had what we have put down for this security.- Again, it shall be enquired in good faith and without impediment, at our request, by men of standing of either side chosen for the purpose, whether the land that the count of Poitiers holds in Quercy on behalf of his wife was given or granted by the king of England with the land of the Agenais as marriage portion or as security, either wholly or in part, to his sister, who was the mother of the last count Raymond of Toulouse. And if it is found that it had so been and this land escheats to him or his heirs on the death of the countess of Poitiers, he shall give it to us or our heirs, and if it escheats to another and it be found by this inquest however that it had been given or granted in the way said above, after the death of the countess of Poitiers, he shall give the fief to us and our heirs, saving the homage of his brothers, if they hold anything there, while they live.- Again, after the death of the count of Poitiers, the king of France or his heirs, kings of France, shall give to us and our heirs the land that the count of Poitiers holds then in Saintonge beyond the R.Charente in fief and in domain that are beyond the Charente, if it escheats to him or his heirs. And if it does not escheat to him, he shall take steps in good fashion to acquire it, by exchange or otherwise, so that we or our heirs shall have it, or he shall give us, in the opinion of men of standing who shall be nominated by either side, a suitable exchange. And for what he shall give us and our heirs in fief and in domain, we and our heirs will do him and his heirs, kings of France, liege homage, and also for Bordeaux, for Bayonne and for Gascony, and for all the land that we hold beyond the English Channel in fief and in domain, and for the islands, if there are any, that we hold that are of the kingdom of France, and we will hold of him as of a peer of France and as duke of Aquitaine. And for all these things aforesaid we will do him our appropriate services until it be found what services are due for these things and then we shall be bound to do them just as they have been found. About homage for the county of Bigorre, for Armagnac and for Fezensac let what is right be done about them. And the king of France absolves us if we or our ancestor ever wronged him by holding his fief without doing him homage and without doing his service, and all arrears.- Again, the king of France shall give us what, in the opinion of men of standing who shall be nominated by either side, 500 knights ought to cost to maintain reasonably for two years and shall be bound to pay this money at Paris at the Temple in six payments over the period of two years, namely the first payment, that is to say a sixth, on the quinzaine of next Candlemas, another payment on the quinzaine of the Ascension following and another on the quinzaine of All Saints and likewise with the remaining payments on the following year. And for this the king of France shall give the Temple or the Hospital or both of them together as surety. And we ought not to spend this money except in the service of God or of the church, or for the benefit of the kingdom of England, and this by view of men of standing of the land chosen by the king of England and by the magnates of this land.- And in making this peace we and our two sons have renounced and do renounce completely all claim upon the king of France and his ancestors and his heirs and successors, and his brothers and their heirs and successors, for us and our heirs and successors if we or our ancestors have or ever had any right in things which the king of France holds or ever held, or his ancestors held or hold, namely in the duchy and the whole land of Normandy, in the county and the whole land of Anjou, or Touraine and of Maine, and in the county and the whole land of Poitiers, or elsewhere in any part of the kingdom of France or in the islands, if the king of France or his brothers, or others from them, hold anything of them, and all arrears.- And likewise we have renounced and do renounce, we and our two sons, all claim upon all those who hold anything, by gift, exchange, sale, purchase, elevation or other similar way, from the king of France or from his ancestors or his brothers in the duchy and the whole land of Normandy, in the county and the whole land of Anjou, or Touraine and of Maine, and in the county and the whole land of Poitiers, or elsewhere in any part of the kingdom of France or in the islands aforesaid, saving to us and our heirs our right in the lands for which we ought to have by this peace, as set out above, to do liege homage to the king of France, and saving that we can ask for our right if we believe we have it in the Agenais, and have it there if the court of the king of France decides it, and likewise in respect of Quercy.- And we have pardoned and renounced all claim upon one another and we pardon and renounce all animosity over disputes and wars, all arrears, and all issues which have been had or which could have been had in all the aforesaid things, and all losses and expenses incurred on either side in war or in any other ways.- And so that this peace may be kept firmly and stably, without any infringement, forever, the king of France has had an oath sworn on his soul by his proxies specially appointed for this and his two sons have sworn to keep these things as long as it concerns each of them, and they have bound themselves and their heirs to keep it by their letters pendant. And that we will keep these things we are bound to give the king of France such surety from the knights of the aforesaid lands that he gives us and from the towns as he will require of us.- And the form of the surety for us from the men and towns shall be this: they shall swear that they will give neither counsel nor support nor aid whereby we or our heir may contravene the peace, and if it should happen, which God forbid, that we or our heir should contravene it and be unwilling to make amends on being requested to do so by the king of France or his heir, the king of France, those who have gone surety shall, within three months of being required by him to do so, be bound to help the king of France and his heirs against us and our heirs until this thing is sufficiently amended in the opinion of the court of the king of France. And this surety shall be renewed every ten years at the request of the king of France or his heirs, the kings of France.- And we promise in good faith for ourselves and for our heirs and successors, to the aforesaid king of France and his heirs and successors, loyally and firmly to keep this peace and this composition established between us and the aforesaid king of France and every one of the things aforesaid just as they are contained above, and we promise that we will not contravene them in any way either personally or through another, and that we have not and will not do anything whereby any or all of the aforesaid things, in whole or part, may be less firm. And so that this peace may be kept firmly and stably, without any infringement, forever, we have bounds ourselves and our heirs to this and have had an oath sworn on our soul in our presence by our proxies to keep the peace, just as it is set out and written above, in good faith as long as it concerns us, and not to contravene it either personally or through another.- And in witness of all these things we have made for the king of France these letters pendant, sealed with our seal. - And by special commandment our sons Edward and Edmund have in our presence sworn to keep and hold firmly this peace and all the things which are contained above and not to contravene them either personally and through others.- This was given at London, the Monday before the feast of St Luke the Evangelist in the year of our Lord’s incarnation one thousand two hundred and fifty nine, in the month of October.”

Published on December 16, 2019 04:17

December 15, 2019

Kissing cousins (1)

Much of Western Europe in the thirteenth century was governed by one big family: the royal houses of France, England, Castile, Aragon, Navarre, Sicily and Provence were closely related to each other. When a quarrel broke out between individual members of the clan, everyone tended to get dragged in.

PamplonaIn July 1274 the king of Navarre, Enrique el Gordo - Henry the Fat - died with no male heir. His baby son had died tragically when his nurse accidentally dropped him over the battlements of the Navarrese castle at Estella. Enrique left a daughter, Jeanne, just eighteen months old. The ensuing scramble for power resembled the Maid of Norway situation in Scotland sixteen years later. To protect his daughter, Enrique had agreed to marry her to Edward I of England’s heir, Prince Henry. In the marriage treaty it was explained that both kings wished to suppress disorder in Navarre, which had been so frequent. The two kings also promised to give each other aid against all other men save their overlord, the king of France: this clause is exactly the same as other treaties of the period, such as the Turnberry Band or the Treaty of Radnor between Roger Mortimer and Prince Llywelyn of Wales.

PamplonaIn July 1274 the king of Navarre, Enrique el Gordo - Henry the Fat - died with no male heir. His baby son had died tragically when his nurse accidentally dropped him over the battlements of the Navarrese castle at Estella. Enrique left a daughter, Jeanne, just eighteen months old. The ensuing scramble for power resembled the Maid of Norway situation in Scotland sixteen years later. To protect his daughter, Enrique had agreed to marry her to Edward I of England’s heir, Prince Henry. In the marriage treaty it was explained that both kings wished to suppress disorder in Navarre, which had been so frequent. The two kings also promised to give each other aid against all other men save their overlord, the king of France: this clause is exactly the same as other treaties of the period, such as the Turnberry Band or the Treaty of Radnor between Roger Mortimer and Prince Llywelyn of Wales.

Philip III

Philip III

The treaty was soon rendered null and void. At the time of Enrique’s death, Edward had just crossed the English Channel on his way to be crowned at Westminster. Soon afterwards his heir, Henry, died unexpectedly, and Navarre was threatened by civil war. Enrique’s widow, Queen Blanche, was also threatened by the pretensions of the kings of Castile and Aragon, who wanted to grab the kingless realm of Navarre for themselves; again there are distinct similarities between Edward’s opportunistic behaviour in Scotland.

Blanche fled with her daughter for protection to the court of Philip III in Paris. The girl was betrothed to Philip’s second son, and as her guardian the king took possession of Blanche’s lands of Champagne and Brie. He also sent the seneschal of Toulouse, Eustace de Beaumarchais, to take the homage of the Navarrese. Eustace installed a French garrison in the citadel of Pamplona, and set about abusing the rights and privileges of the Navarrese people. The result was a full-scale revolt in favour of the king of Castile. Eustace soon found himself besieged inside the citadel by an army of Navarrese nobles.

He sent a messenger to King Philip, who ordered the Comte d’Artois to raise an army in the seneschalries of Toulouse, Carcassone, Beaucaire and Périgeux, and march to the relief of Pamplona. Artois and his men dashed across the Pyrenees and laid siege to the Navarrese who had laid siege to the French. At this point the Navarrese nobles decided it was all far too confusing, and ran away under cover of darkness. The citizens of Pamplona and the rest of Navarre then submitted to the French.

PamplonaIn July 1274 the king of Navarre, Enrique el Gordo - Henry the Fat - died with no male heir. His baby son had died tragically when his nurse accidentally dropped him over the battlements of the Navarrese castle at Estella. Enrique left a daughter, Jeanne, just eighteen months old. The ensuing scramble for power resembled the Maid of Norway situation in Scotland sixteen years later. To protect his daughter, Enrique had agreed to marry her to Edward I of England’s heir, Prince Henry. In the marriage treaty it was explained that both kings wished to suppress disorder in Navarre, which had been so frequent. The two kings also promised to give each other aid against all other men save their overlord, the king of France: this clause is exactly the same as other treaties of the period, such as the Turnberry Band or the Treaty of Radnor between Roger Mortimer and Prince Llywelyn of Wales.

PamplonaIn July 1274 the king of Navarre, Enrique el Gordo - Henry the Fat - died with no male heir. His baby son had died tragically when his nurse accidentally dropped him over the battlements of the Navarrese castle at Estella. Enrique left a daughter, Jeanne, just eighteen months old. The ensuing scramble for power resembled the Maid of Norway situation in Scotland sixteen years later. To protect his daughter, Enrique had agreed to marry her to Edward I of England’s heir, Prince Henry. In the marriage treaty it was explained that both kings wished to suppress disorder in Navarre, which had been so frequent. The two kings also promised to give each other aid against all other men save their overlord, the king of France: this clause is exactly the same as other treaties of the period, such as the Turnberry Band or the Treaty of Radnor between Roger Mortimer and Prince Llywelyn of Wales. Philip III

Philip IIIThe treaty was soon rendered null and void. At the time of Enrique’s death, Edward had just crossed the English Channel on his way to be crowned at Westminster. Soon afterwards his heir, Henry, died unexpectedly, and Navarre was threatened by civil war. Enrique’s widow, Queen Blanche, was also threatened by the pretensions of the kings of Castile and Aragon, who wanted to grab the kingless realm of Navarre for themselves; again there are distinct similarities between Edward’s opportunistic behaviour in Scotland.

Blanche fled with her daughter for protection to the court of Philip III in Paris. The girl was betrothed to Philip’s second son, and as her guardian the king took possession of Blanche’s lands of Champagne and Brie. He also sent the seneschal of Toulouse, Eustace de Beaumarchais, to take the homage of the Navarrese. Eustace installed a French garrison in the citadel of Pamplona, and set about abusing the rights and privileges of the Navarrese people. The result was a full-scale revolt in favour of the king of Castile. Eustace soon found himself besieged inside the citadel by an army of Navarrese nobles.

He sent a messenger to King Philip, who ordered the Comte d’Artois to raise an army in the seneschalries of Toulouse, Carcassone, Beaucaire and Périgeux, and march to the relief of Pamplona. Artois and his men dashed across the Pyrenees and laid siege to the Navarrese who had laid siege to the French. At this point the Navarrese nobles decided it was all far too confusing, and ran away under cover of darkness. The citizens of Pamplona and the rest of Navarre then submitted to the French.

Published on December 15, 2019 09:36

December 14, 2019

Fate is inexorable

Maurice Powicke on the last years of Edward I of England:

“His good fortune, once praised by the poets of the Midi, deserted him. He was dogged by mischance: dark forces which no judgements in parliaments, no rapid campaigns followed by conciliatory measures could overcome, gradually beset him. At one time he was driven to fall back on the law of necessity, at another to turn to the pope for sworn absolution from his own undertakings. He had no comprehension of what we call nationalism, but thought in terms of law and rights and obligation to maintain the ‘state’ of crown and realm. The French, in his view, had tricked him, the Scottish lords and prelates betrayed him, the archbishop and earls deserted him. His mood hardened. He coped with the English recalcitrants, came to terms with Philip the Fair, crushed William Wallace, and drove Archbishop Winchelsey into exile, but in Robert Bruce, whose grandfather had fought on his side at Lewes, he found a new kind of enemy. He faced him and his followers, men and women alike, in a spirit of savage and ruthless exaltation”.

Or, to quote Uhtred of Bebbanburg - Wyrd bið ful āræd (Fate is inexorable). Another historian described Bruce as Edward’s mirror image, so in the end the king struck at a version of himself: “A crowned warrior, careless of men’s lives, who meant to have his way at any price”.

“His good fortune, once praised by the poets of the Midi, deserted him. He was dogged by mischance: dark forces which no judgements in parliaments, no rapid campaigns followed by conciliatory measures could overcome, gradually beset him. At one time he was driven to fall back on the law of necessity, at another to turn to the pope for sworn absolution from his own undertakings. He had no comprehension of what we call nationalism, but thought in terms of law and rights and obligation to maintain the ‘state’ of crown and realm. The French, in his view, had tricked him, the Scottish lords and prelates betrayed him, the archbishop and earls deserted him. His mood hardened. He coped with the English recalcitrants, came to terms with Philip the Fair, crushed William Wallace, and drove Archbishop Winchelsey into exile, but in Robert Bruce, whose grandfather had fought on his side at Lewes, he found a new kind of enemy. He faced him and his followers, men and women alike, in a spirit of savage and ruthless exaltation”.

Or, to quote Uhtred of Bebbanburg - Wyrd bið ful āræd (Fate is inexorable). Another historian described Bruce as Edward’s mirror image, so in the end the king struck at a version of himself: “A crowned warrior, careless of men’s lives, who meant to have his way at any price”.

Published on December 14, 2019 05:07

Royaux! Royaux!

“The Battle of Taillebourg won by Saint Louis” is a painting by Eugene Delacroix, first exhibited in 1837 at the Galeries des Batailles at the Palace of Versailles. It is now in the Louvre and commemorates the victory of Saint Louis of France over Henry III of England at the bridge of Taillebourg on 21 July 1242. Louis himself is shown leading the charge against the hapless rosbifs.

It is also a good example of political spin; or gilding the lily, as it were. There was no battle at Taillebourg, and French historians have not been slow to admit it: Charles Bémont, writing in 1893, remarked:

“Les chroniqueurs français sont aussi muets sur une bataille au pont de Taillebourg”

My execrable French translates this as: “French chroniclers are also silent on a battle at the bridge of Taillebourg”.

A contemporary French writer, Philippe Mousket, had this to say:

“When the king [Louis] was on the Charente, he made a bridge to allow his people to pass. There were a large number of horsemen and footsoldiers; they were eager but tired. On the other side were the English. Their boasting and cunning availed them little, for they were chased away in confusion to the gates of Saintes”.

This fits with other accounts, which state the English withdrew from Taillebourg because they didn’t have enough men to guard all the passes over the river Charente. Guillaume Guiart, a French soldier-poet active in about 1300, wrote:

“The terrified English turn their backs and ran away; with tears, sighs and complaints, they returned together to Saintes”.

An anonymous French poet, whose work was discovered in a collection of 16th century papers, wrote:

“The Poitevin, the Gascon, and the Englishman badly guarded the bridge of Taillebourg, and despite of them the French passed over.”

French writers were clearly amused at the flight of the English from Taillebourg, but there is no suggestion of any combat. Rather, Henry and his Poitevin and Gascon allies retreated in haste to Saintes. They were hotly pursed by five hundred mounted French sergeants, who galloped across a wooden bridge to cut the line of retreat to Saintes. They had to be stopped, and Bémont suggests it was at this point that Richard of Cornwall, Henry III’s brother, intervened to negotiate with Saint Louis. Matthew Paris, an English chronicler, credits Richard with persuading the French king to stay his hand. Guillaume Nangis, a French chronicler, claims Louis ignored him. Take your pick.

There was a battle at Saintes, where the English had retired. On 22 July the Comte de la Marche, one of Henry’s allies, was alerted to the presence of French scouts. He gathered up a band of English, Irish and Gascons and attacked the foragers, driving them away. The Count of Boulogne brought up his French troops in support and a general engagement broke out in the lanes and vineyards. The French cried ‘Montjoie!’ while the English cried “Royaux! Royaux!’ Eventually Henry’s army was scattered, his baggage train captured and the king himself forced to flee into the town, accompanied by a guard of 120 sergeants. Many of his men were killed or captured in the flight; those taken prisoner included John Mansel, Henry’s clerk. The following day, after an argument with the Comte de la Marche, Henry quit Saintes and retreated into Gascony.

One has to wonder why Delacroix based his painting on the non-combat at Taillebourg, instead of the French victory at Saintes the following day. He was possibly inspired by Joinville, a French chronicler writing sixty years after the event, who mixed up the events at Taillebourg and Saintes. Or he chose to apply a bit of artistic licence.

It is also a good example of political spin; or gilding the lily, as it were. There was no battle at Taillebourg, and French historians have not been slow to admit it: Charles Bémont, writing in 1893, remarked:

“Les chroniqueurs français sont aussi muets sur une bataille au pont de Taillebourg”

My execrable French translates this as: “French chroniclers are also silent on a battle at the bridge of Taillebourg”.

A contemporary French writer, Philippe Mousket, had this to say:

“When the king [Louis] was on the Charente, he made a bridge to allow his people to pass. There were a large number of horsemen and footsoldiers; they were eager but tired. On the other side were the English. Their boasting and cunning availed them little, for they were chased away in confusion to the gates of Saintes”.

This fits with other accounts, which state the English withdrew from Taillebourg because they didn’t have enough men to guard all the passes over the river Charente. Guillaume Guiart, a French soldier-poet active in about 1300, wrote:

“The terrified English turn their backs and ran away; with tears, sighs and complaints, they returned together to Saintes”.

An anonymous French poet, whose work was discovered in a collection of 16th century papers, wrote:

“The Poitevin, the Gascon, and the Englishman badly guarded the bridge of Taillebourg, and despite of them the French passed over.”

French writers were clearly amused at the flight of the English from Taillebourg, but there is no suggestion of any combat. Rather, Henry and his Poitevin and Gascon allies retreated in haste to Saintes. They were hotly pursed by five hundred mounted French sergeants, who galloped across a wooden bridge to cut the line of retreat to Saintes. They had to be stopped, and Bémont suggests it was at this point that Richard of Cornwall, Henry III’s brother, intervened to negotiate with Saint Louis. Matthew Paris, an English chronicler, credits Richard with persuading the French king to stay his hand. Guillaume Nangis, a French chronicler, claims Louis ignored him. Take your pick.

There was a battle at Saintes, where the English had retired. On 22 July the Comte de la Marche, one of Henry’s allies, was alerted to the presence of French scouts. He gathered up a band of English, Irish and Gascons and attacked the foragers, driving them away. The Count of Boulogne brought up his French troops in support and a general engagement broke out in the lanes and vineyards. The French cried ‘Montjoie!’ while the English cried “Royaux! Royaux!’ Eventually Henry’s army was scattered, his baggage train captured and the king himself forced to flee into the town, accompanied by a guard of 120 sergeants. Many of his men were killed or captured in the flight; those taken prisoner included John Mansel, Henry’s clerk. The following day, after an argument with the Comte de la Marche, Henry quit Saintes and retreated into Gascony.

One has to wonder why Delacroix based his painting on the non-combat at Taillebourg, instead of the French victory at Saintes the following day. He was possibly inspired by Joinville, a French chronicler writing sixty years after the event, who mixed up the events at Taillebourg and Saintes. Or he chose to apply a bit of artistic licence.

Published on December 14, 2019 03:05

December 13, 2019

Fire and sword

Lacy’s war. At the end of the campaign season of summer 1296, Henry de Lacy led his troops out from the ducal citadels in Gascony on a large-scale raid - or chevauchée - into the Toulousaine in southeast France. It was the usual grim work: destruction of villages and slaughter of non-combatants, meant to destroy the enemy’s economic base and terrorize his peasantry into submission.

Robert Wace, writing in the twelfth century, described the way of war:

“Go through this country with fire,

destroying houses and towns,

take all booty and food,

pigs and sheep and cattle.

Let Normans find no food

Nor any thing on which to live.”

Lacy also needed to restore the morale of his soldiers after the defeats and failures earlier in the year. The season ended for the English on a relative high, since they had lost no more ground to the French and showed they still had teeth. The French, meanwhile, despite their numerical and strategic superiority, had proved incapable of wiping out the last English enclaves in the duchy.

Toulouse

Toulouse

In September, once the campaign season was over for the year, a number of soldiers were repatriated or ‘demobbed’ back to England. Only two knights were sent home; one was Sir William Vescy, who was sick, and the other Sir William Martin. The rest were infantry, some of them criminals on a strictly-limited service obligation in return for a royal pardon. One of the felons was William le Fevre, outlawed for robbery in Southampton, another John Semot, outlawed for robbery in Devon, and a third Roger de Penteney, outlawed for homicide.

Robert Wace, writing in the twelfth century, described the way of war:

“Go through this country with fire,

destroying houses and towns,

take all booty and food,

pigs and sheep and cattle.

Let Normans find no food

Nor any thing on which to live.”

Lacy also needed to restore the morale of his soldiers after the defeats and failures earlier in the year. The season ended for the English on a relative high, since they had lost no more ground to the French and showed they still had teeth. The French, meanwhile, despite their numerical and strategic superiority, had proved incapable of wiping out the last English enclaves in the duchy.

Toulouse

ToulouseIn September, once the campaign season was over for the year, a number of soldiers were repatriated or ‘demobbed’ back to England. Only two knights were sent home; one was Sir William Vescy, who was sick, and the other Sir William Martin. The rest were infantry, some of them criminals on a strictly-limited service obligation in return for a royal pardon. One of the felons was William le Fevre, outlawed for robbery in Southampton, another John Semot, outlawed for robbery in Devon, and a third Roger de Penteney, outlawed for homicide.

Published on December 13, 2019 09:26

December 12, 2019

What to do with Amaury

Part of a letter from John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Pope Martin IV. This is dated April 1282 and concerns the release of Amaury de Montfort from prison.

Amaury was the youngest son of Simon de Monfort. He was the brother of Guy, the murderer of Henry of Almaine, and a papal chaplain and graduate of the Schools of Padua in Italy. Described as ‘a litigious man with a vitriolic tongue’, he accompanied his sister Eleanor in 1275 on their ill-fated voyage to North Wales. Amaury had been forbidden by Edward I from setting foot anywhere in the British Isles; in his defence Prince Llywelyn wrote to the king and claimed that Amaury had not intended to get off the ship.

Unsurprisingly, this argument cut no ice. Amaury was imprisoned at Corfe Castle for seven years, where he wrote a poem complaining of his unjust treatment. He cannot have been comforted by the knowledge that Corfe was the scene of the murder of Maud de Braose and her son, starved to death by Edward’s grandfather, King John. Later Archbishop Peckham was allowed to be Amaury’s warden, responsible for his safe-keeping. One pope after another begged Edward to release him. At last the archbishop, in a personal interview with the king at the castle of Devizes, in April 1282, got Edward’s consent to Amaury’s departure form the country.

As the archbishop observed in the report to Pope Martin IV, the timing was awkward. War in Wales had begun again, news which, in the common opinion, suggested the detention rather than the release of Amaury. The king decided to let him go against the counsel of the magnates of the realm, even though ‘the wishes and counsel of no few had been to the contrary’.

It seems the king simply wanted to be rid of the Montforts. Amaury was required to swear a solemn oath that he would never return to England. Amaury immediately went to France and on 22 May wrote to the king from Arras, thanking him for his grace, promising fidelity, and asking for liberty ‘to recover his rights’. The demand was either refused or ignored, so in December 1284 he began a suit in the court of Rome against Edmund, the king’s brother, for restitution of his inheritance. Amaury made little progress with his claim. He is known to have been in Paris in June 1286, and upon the death of his brother Guy renounced holy orders and took up knighthood. Amaury is thought to have retired to Italy and died in 1292, unmarried and childless.

Amaury was the youngest son of Simon de Monfort. He was the brother of Guy, the murderer of Henry of Almaine, and a papal chaplain and graduate of the Schools of Padua in Italy. Described as ‘a litigious man with a vitriolic tongue’, he accompanied his sister Eleanor in 1275 on their ill-fated voyage to North Wales. Amaury had been forbidden by Edward I from setting foot anywhere in the British Isles; in his defence Prince Llywelyn wrote to the king and claimed that Amaury had not intended to get off the ship.

Unsurprisingly, this argument cut no ice. Amaury was imprisoned at Corfe Castle for seven years, where he wrote a poem complaining of his unjust treatment. He cannot have been comforted by the knowledge that Corfe was the scene of the murder of Maud de Braose and her son, starved to death by Edward’s grandfather, King John. Later Archbishop Peckham was allowed to be Amaury’s warden, responsible for his safe-keeping. One pope after another begged Edward to release him. At last the archbishop, in a personal interview with the king at the castle of Devizes, in April 1282, got Edward’s consent to Amaury’s departure form the country.

As the archbishop observed in the report to Pope Martin IV, the timing was awkward. War in Wales had begun again, news which, in the common opinion, suggested the detention rather than the release of Amaury. The king decided to let him go against the counsel of the magnates of the realm, even though ‘the wishes and counsel of no few had been to the contrary’.

It seems the king simply wanted to be rid of the Montforts. Amaury was required to swear a solemn oath that he would never return to England. Amaury immediately went to France and on 22 May wrote to the king from Arras, thanking him for his grace, promising fidelity, and asking for liberty ‘to recover his rights’. The demand was either refused or ignored, so in December 1284 he began a suit in the court of Rome against Edmund, the king’s brother, for restitution of his inheritance. Amaury made little progress with his claim. He is known to have been in Paris in June 1286, and upon the death of his brother Guy renounced holy orders and took up knighthood. Amaury is thought to have retired to Italy and died in 1292, unmarried and childless.

Published on December 12, 2019 03:36

December 11, 2019

Lacy's war

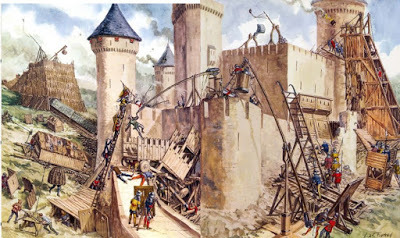

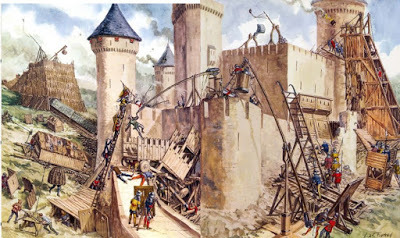

On the Feast of St John the Baptist (24 June) 1296, Henry de Lacy set out to besiege Dax, a fortified town just forty kilometres northeast of Bayonne, the main English stronghold in Gascony. Dax had fallen to the French in 1294, and its garrison threatened the ducal enclave in the south of the duchy.

Dax

Dax

Lacy chose to attack Dax while the French field army was concentrated on Bourg in the north. First he had to recreate the ducal army that had disintegrated after the death of his predecessor, Edmund of Lancaster. He was short of funds and could only hire one knight, Sir Montasivus de Noillan, who received £40 to serve with horses and arms for eight weeks. Montasivus had presumably completed his feudal term of service and now continued on mercenary pay.

Somehow Lacy scraped together enough men, and laid siege to Dax from about 24 June to 12 August. The Anglo-Gascons threw everything they had at the town, with daily assaults for almost seven weeks; the scale of the effort is reflected in financial accounts, which show the besiegers consumed almost £100 worth of wheat, while labourers were hired to press the attack by land and river.

The siege failed due to lack of food, and the build-up of another French army at nearby Mont-de-Marsan. Lacy was not prepared to risk the only English field army in Gascony in a pitched battle, so withdrew to Bayonne.

Lacy’s failure at Dax could also be attributed to the attitude of the citizens. Unlike many towns in southern Gascony, the people of Dax were not uniformly loyal to the king-duke of England: as early as 1278 Edward I had pardoned them for their ‘disobedience’. Immediately after the siege in 1296, on 25 August, Robert of Artois granted the citizens a privileged exemption from tolls. In context this looks like either a reward or a bribe. In addition, Dax does not appear on the lists of towns in Gascony that advanced loans to the English cause.

The war was rapidly drifting into stalemate: neither side made any ground in the roasting summer of 1296, and the English and French commanders had failed dismally in their siege operations.

Dax

DaxLacy chose to attack Dax while the French field army was concentrated on Bourg in the north. First he had to recreate the ducal army that had disintegrated after the death of his predecessor, Edmund of Lancaster. He was short of funds and could only hire one knight, Sir Montasivus de Noillan, who received £40 to serve with horses and arms for eight weeks. Montasivus had presumably completed his feudal term of service and now continued on mercenary pay.

Somehow Lacy scraped together enough men, and laid siege to Dax from about 24 June to 12 August. The Anglo-Gascons threw everything they had at the town, with daily assaults for almost seven weeks; the scale of the effort is reflected in financial accounts, which show the besiegers consumed almost £100 worth of wheat, while labourers were hired to press the attack by land and river.

The siege failed due to lack of food, and the build-up of another French army at nearby Mont-de-Marsan. Lacy was not prepared to risk the only English field army in Gascony in a pitched battle, so withdrew to Bayonne.

Lacy’s failure at Dax could also be attributed to the attitude of the citizens. Unlike many towns in southern Gascony, the people of Dax were not uniformly loyal to the king-duke of England: as early as 1278 Edward I had pardoned them for their ‘disobedience’. Immediately after the siege in 1296, on 25 August, Robert of Artois granted the citizens a privileged exemption from tolls. In context this looks like either a reward or a bribe. In addition, Dax does not appear on the lists of towns in Gascony that advanced loans to the English cause.

The war was rapidly drifting into stalemate: neither side made any ground in the roasting summer of 1296, and the English and French commanders had failed dismally in their siege operations.

Published on December 11, 2019 05:09

December 10, 2019

Slave girls

Today is the (probable) anniversary of the death of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in December 1282. Rather than go through the murky deed all over again, it might be worth rewinding a couple of generations.

In 1222 Llywelyn ab Iorwerth - Llywelyn the Great - asked Pope Honorius III to abolish the custom in Wales that illegitimate children could inherit just as if they were legitimate. Further, the prince asked that the pope would confirm Llywelyn’s statute that his son Dafydd, ‘by his legitimate wife Joan, daughter of the late king of England’, would succeed him in all his possessions.

Llywelyn’s original petition is lost, but several responses from the pope survive. The archives at Vatican City contain the pope’s final judgement:

“To the nobleman Lord Llywelyn of North Wales. Bringing about from us the attached petition. Certainly your petition showed that since some detestable custom or rather corruption has developed in the land subject to your authority - as evidently the son of the slave girl could be the heir together with the son of the free woman and illegitimate sons could obtain the inheritance just as the legitimate - you [Llywelyn] and your Lord Henry, illustrious king of the English, beloved sons of Christ, have agreed in harmony and also further with the intervening authority of our beloved sons, our venerable brother Archbishop Stephen of Canterbury…that Dafydd your son, who from Joan the daughter of Clementia and the king of England, your legal wife, should succeed in receiving your inheritance by right in all your possessions.”

Llywelyn’s elder son, Gruffudd, was thus condemned as ‘the son of the slave girl’ and barred from inheritance. Far from being a slave, his mother was in fact the daughter of King Reginald of Man. This was all swept aside by Llywelyn the Great, in his desire to get rid of his first wife and marry into the Plantagenets: one might draw comparisons with the behaviour of his eighth great-grandson, Henry VIII.

Gruffudd’s son was the aforesaid Prince Llywelyn, killed near Builth in 1282 by his kinsmen, the Mortimers. The decision of his grandfather Llywelyn the Great to change the inheritance laws in Wales meant that Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was the son of a legally declared bastard and the grandson of a woman condemned as a slave by the Holy See. The Mortimers, on the other hand, were legitimate heirs via the female line of Llywelyn the Great’s son, Dafydd, who died without issue in 1246.

Whether or not the rules of succession influenced the rules of engagement near Builth in December 1282 is speculation, but it’s something else to throw in the mix.

In 1222 Llywelyn ab Iorwerth - Llywelyn the Great - asked Pope Honorius III to abolish the custom in Wales that illegitimate children could inherit just as if they were legitimate. Further, the prince asked that the pope would confirm Llywelyn’s statute that his son Dafydd, ‘by his legitimate wife Joan, daughter of the late king of England’, would succeed him in all his possessions.

Llywelyn’s original petition is lost, but several responses from the pope survive. The archives at Vatican City contain the pope’s final judgement:

“To the nobleman Lord Llywelyn of North Wales. Bringing about from us the attached petition. Certainly your petition showed that since some detestable custom or rather corruption has developed in the land subject to your authority - as evidently the son of the slave girl could be the heir together with the son of the free woman and illegitimate sons could obtain the inheritance just as the legitimate - you [Llywelyn] and your Lord Henry, illustrious king of the English, beloved sons of Christ, have agreed in harmony and also further with the intervening authority of our beloved sons, our venerable brother Archbishop Stephen of Canterbury…that Dafydd your son, who from Joan the daughter of Clementia and the king of England, your legal wife, should succeed in receiving your inheritance by right in all your possessions.”

Llywelyn’s elder son, Gruffudd, was thus condemned as ‘the son of the slave girl’ and barred from inheritance. Far from being a slave, his mother was in fact the daughter of King Reginald of Man. This was all swept aside by Llywelyn the Great, in his desire to get rid of his first wife and marry into the Plantagenets: one might draw comparisons with the behaviour of his eighth great-grandson, Henry VIII.

Gruffudd’s son was the aforesaid Prince Llywelyn, killed near Builth in 1282 by his kinsmen, the Mortimers. The decision of his grandfather Llywelyn the Great to change the inheritance laws in Wales meant that Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was the son of a legally declared bastard and the grandson of a woman condemned as a slave by the Holy See. The Mortimers, on the other hand, were legitimate heirs via the female line of Llywelyn the Great’s son, Dafydd, who died without issue in 1246.

Whether or not the rules of succession influenced the rules of engagement near Builth in December 1282 is speculation, but it’s something else to throw in the mix.

Published on December 10, 2019 02:42

December 9, 2019

The army that didn't vanish

It’s almost that time of year again - no, not Christmas. I refer to the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales, on 10 or 11 December 1282.

The usual populist stuff is doing the rounds at the moment. One particular conspiracy theory refuses to go away. In his book ‘Ghosts on the Fairway: the Army that Vanished’ the late Anthony Edwards suggested that Llywelyn and his men were all murdered, after being lured to a peace conference in which they were persuaded to put down their weapons. After this act of remarkable stupidity, they were all slaughtered and dumped under a nearby field, which is now a golf course. Edwards challenged his critics to dig up the golf course. Nobody took him up on that, so - the theory goes - it must be true.

Edwards based his suggestion on the following line from the Chronicle of Peterborough:

“Furthermore, not one of the prince’s cavalry escaped death, but they were killed with 3000 of the foot and also the three magnates of the land who died with him; namely, Almafar, who was lord of Llanbadarn Fawr, Rhys ap Gruffudd, who was seneschal of all the land of the prince, and thirdly, it is thought, Llywelyn Fychan, who was lord of Bromfield; of the English, truly it is said, none in that place were killed or wounded”.

Because the chronicler states that no English were harmed, Edwards came up with his truce theory. To be fair to the author, it was only a suggestion on his part. It is now accepted and aggressively marketed as fact in certain quarters.

The Peterborough chronicler also states that Llywelyn’s army consisted of 160 cavalry and 7000 footsoldiers. If only 3000 of the foot were killed, that means the rest got away. If the Welsh had laid down their arms, it is difficult to see how over half the army could have escaped. This point is seldom acknowledged or discussed, because it is inconvenient to the narrative. You either use the source in full, or you don't. You don't get to pick and choose what you like and dump the rest.

Peterborough aside, there are over thirty chronicle, poetry and letter sources for the death of Llywelyn, English and Welsh, contemporary or near-contemporary. Many conflict with each other, a few make no sense at all, virtually all of them have some kind of spin or political bias. The one reasonable certainty is that Llywelyn was lured to an ambush by his cousins, Edmund and Roger Mortimer, and executed by their retainers. His army had either already been put to flight, or was ambushed and routed shortly afterwards. The context and motive for the killing is complicated, and can be traced all the way back to the time of Llywelyn the Great.

But people don’t like complicated. It gets in the way. It makes them think, and question, and engage with unpleasant realities they would rather ignore or avoid. People don’t like that sort of thing. I know I don’t.

Too bad. I doubt Llywelyn liked having his head cut off, but that’s what he got.

The usual populist stuff is doing the rounds at the moment. One particular conspiracy theory refuses to go away. In his book ‘Ghosts on the Fairway: the Army that Vanished’ the late Anthony Edwards suggested that Llywelyn and his men were all murdered, after being lured to a peace conference in which they were persuaded to put down their weapons. After this act of remarkable stupidity, they were all slaughtered and dumped under a nearby field, which is now a golf course. Edwards challenged his critics to dig up the golf course. Nobody took him up on that, so - the theory goes - it must be true.

Edwards based his suggestion on the following line from the Chronicle of Peterborough:

“Furthermore, not one of the prince’s cavalry escaped death, but they were killed with 3000 of the foot and also the three magnates of the land who died with him; namely, Almafar, who was lord of Llanbadarn Fawr, Rhys ap Gruffudd, who was seneschal of all the land of the prince, and thirdly, it is thought, Llywelyn Fychan, who was lord of Bromfield; of the English, truly it is said, none in that place were killed or wounded”.

Because the chronicler states that no English were harmed, Edwards came up with his truce theory. To be fair to the author, it was only a suggestion on his part. It is now accepted and aggressively marketed as fact in certain quarters.

The Peterborough chronicler also states that Llywelyn’s army consisted of 160 cavalry and 7000 footsoldiers. If only 3000 of the foot were killed, that means the rest got away. If the Welsh had laid down their arms, it is difficult to see how over half the army could have escaped. This point is seldom acknowledged or discussed, because it is inconvenient to the narrative. You either use the source in full, or you don't. You don't get to pick and choose what you like and dump the rest.

Peterborough aside, there are over thirty chronicle, poetry and letter sources for the death of Llywelyn, English and Welsh, contemporary or near-contemporary. Many conflict with each other, a few make no sense at all, virtually all of them have some kind of spin or political bias. The one reasonable certainty is that Llywelyn was lured to an ambush by his cousins, Edmund and Roger Mortimer, and executed by their retainers. His army had either already been put to flight, or was ambushed and routed shortly afterwards. The context and motive for the killing is complicated, and can be traced all the way back to the time of Llywelyn the Great.

But people don’t like complicated. It gets in the way. It makes them think, and question, and engage with unpleasant realities they would rather ignore or avoid. People don’t like that sort of thing. I know I don’t.

Too bad. I doubt Llywelyn liked having his head cut off, but that’s what he got.

Published on December 09, 2019 04:31