David Pilling's Blog, page 41

November 29, 2019

Mortimer's end

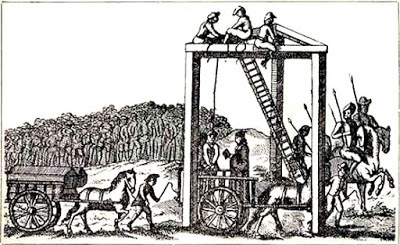

Today is the anniversary of the execution of Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, at Tyburn in 1330. At his trial Mortimer was gagged and thus unable to respond to the various charges of treason laid against him. Tellingly, this included the charge that he had 'accroached the royal power'. In the days before his execution Mortimer and two of his sons were walled up inside a chamber with no doors or windows next to the bedroom of the young Edward III, who had led the coup to overthrow his mother's ally and (possible) lover.

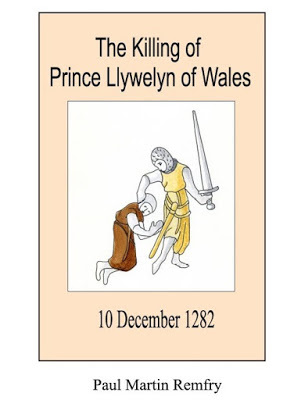

It is my belief - not necessarily shared by everyone - that Mortimer's failed bid for power was all part of his family's desire to seize the crowns of England and Wales in the past two generations: his father Edmund and uncle Roger had connived to murder Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales in 1282, an action clouded by the stubborn popular belief that Edward I organised the killing. It is clear from the private correspondence between the king, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Chancellor in the immediate aftermath of Llywelyn's death that they knew nothing of the affair, and were themselves threatened by it. Or at least that is what I glean from the surviving letters.

Edmund spent the rest of his days under a cloud of royal displeasure, but his son would murder two of Edward I's children - Edward II and the Earl of Kent - and come within an ace of toppling the grandson. In the event he failed and ended his days with a suitably dramatic flourish, leaping from the high scaffold at Tyburn in the black tunic he had worn at Edward II's funeral: a final 'up yours' to everyone. The snapping of his neck spelled the end of Mortimer power-grabs, at least for a generation or two.

It is my belief - not necessarily shared by everyone - that Mortimer's failed bid for power was all part of his family's desire to seize the crowns of England and Wales in the past two generations: his father Edmund and uncle Roger had connived to murder Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales in 1282, an action clouded by the stubborn popular belief that Edward I organised the killing. It is clear from the private correspondence between the king, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Chancellor in the immediate aftermath of Llywelyn's death that they knew nothing of the affair, and were themselves threatened by it. Or at least that is what I glean from the surviving letters.

Edmund spent the rest of his days under a cloud of royal displeasure, but his son would murder two of Edward I's children - Edward II and the Earl of Kent - and come within an ace of toppling the grandson. In the event he failed and ended his days with a suitably dramatic flourish, leaping from the high scaffold at Tyburn in the black tunic he had worn at Edward II's funeral: a final 'up yours' to everyone. The snapping of his neck spelled the end of Mortimer power-grabs, at least for a generation or two.

Published on November 29, 2019 06:34

Lacy's war

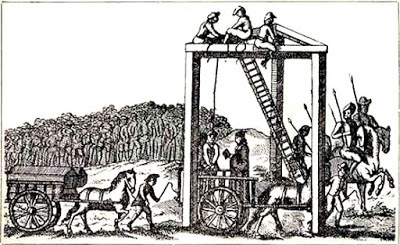

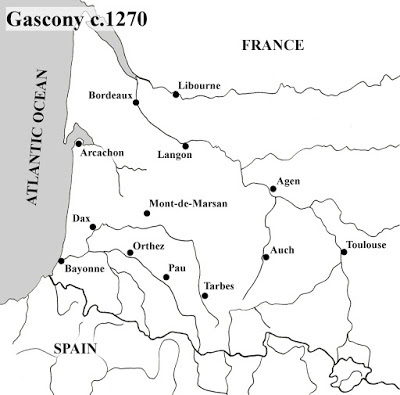

In January 1296 the English expeditionary force to Gascony finally got underway, seventeen months over schedule. This was originally supposed to be the second of a tripartite expedition in autumn 1294, planned to hit the French army of occupation with three successive waves of attack in the space of just nine weeks. The war of Prince Madog in Wales obliged Edward I to turn his resources against the Welsh instead, which meant the French in Gascony had time to prepare.

The leaders of the expedition were the king’s brother, Edmund of Lancaster, and Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. Edmund was in poor health but may have felt obliged to go: it was thanks to his botched diplomacy that the French had seized Gascony in the first place. The surrender on his orders to the constable of France, Raoul de Nesle, in March 1294 had included the handing over of most of the military strongholds in the duchy and the capital city, Bordeaux. Twenty ducal officers were also given up as hostages.

This meant that the English had voluntarily removed their own shield against French aggression, while the arrest of key members of the ducal administration left scarcely anyone to organise local resistance. The only bright spot was the enduring loyalty of the Gascons to the Plantagenet king-duke: of the 100 Gascon nobles summoned to arms by Edward I, about 80 answered the call. Those who defected to the French, lured by bribes or coercion, were mostly from the Agenais. This was a strip of territory located to the north of Gascony, only acquired by the English in 1279. Thus the inhabitants may have felt they owed their homage to the Capets instead of the Plantagenets.

Apart from the nobles, about 500 of the lesser Gascon gentry also stayed loyal to the English. Many of these chose exile in England rather than submission to the French, which meant they had to be provided for. Refugees from all over the duchy flocked to England, and the king was hard-put to find money and employment for them all. Gascon nobles queued up at the exchequer at York and Westminster to recieve funds. Edward paid them when he could, though usually in arrears: in June 1302, for instance, a cart loaded with the massive sum of £1000 was sent down from York to Westminster to pay Gascon creditors still not fully satisfied for their wages.

With much of Gascony in French hands, and so many loyal Gascons in England, Edmund and Lacy’s task was not an enviable one. They sailed for the north of the duchy, to try and re-establish a northern bridgehead against the French.

The map of Gascony is drawn by a friend of mine, Martin Bolton.

The leaders of the expedition were the king’s brother, Edmund of Lancaster, and Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. Edmund was in poor health but may have felt obliged to go: it was thanks to his botched diplomacy that the French had seized Gascony in the first place. The surrender on his orders to the constable of France, Raoul de Nesle, in March 1294 had included the handing over of most of the military strongholds in the duchy and the capital city, Bordeaux. Twenty ducal officers were also given up as hostages.

This meant that the English had voluntarily removed their own shield against French aggression, while the arrest of key members of the ducal administration left scarcely anyone to organise local resistance. The only bright spot was the enduring loyalty of the Gascons to the Plantagenet king-duke: of the 100 Gascon nobles summoned to arms by Edward I, about 80 answered the call. Those who defected to the French, lured by bribes or coercion, were mostly from the Agenais. This was a strip of territory located to the north of Gascony, only acquired by the English in 1279. Thus the inhabitants may have felt they owed their homage to the Capets instead of the Plantagenets.

Apart from the nobles, about 500 of the lesser Gascon gentry also stayed loyal to the English. Many of these chose exile in England rather than submission to the French, which meant they had to be provided for. Refugees from all over the duchy flocked to England, and the king was hard-put to find money and employment for them all. Gascon nobles queued up at the exchequer at York and Westminster to recieve funds. Edward paid them when he could, though usually in arrears: in June 1302, for instance, a cart loaded with the massive sum of £1000 was sent down from York to Westminster to pay Gascon creditors still not fully satisfied for their wages.

With much of Gascony in French hands, and so many loyal Gascons in England, Edmund and Lacy’s task was not an enviable one. They sailed for the north of the duchy, to try and re-establish a northern bridgehead against the French.

The map of Gascony is drawn by a friend of mine, Martin Bolton.

Published on November 29, 2019 04:19

November 27, 2019

Murky Mortimers

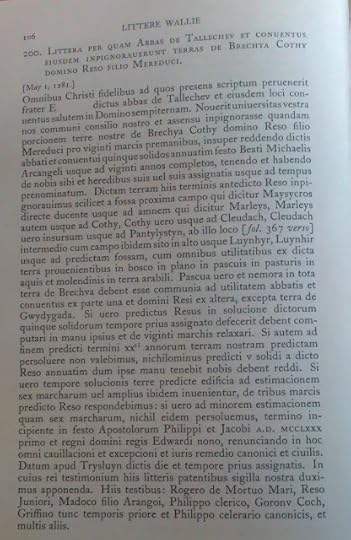

A charter dated 1 May 1281, in which the abbot of Tal-y-Llychau pledged the abbey’s lands of Brechfa in Gothi and and the land of Brechfa except for Llanegwad to Rhys ap Maredudd for eighteen years.

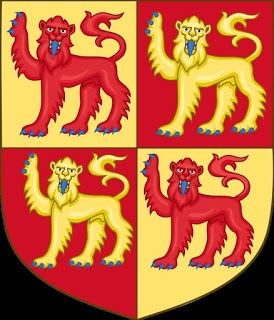

The first name on the witness list to the charter is Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, the only ‘Englishman’ among the otherwise Welsh names. The Anglicised form of Mortimer’s name is deceptive: he was a grandson of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth and a nephew of Dafydd ap Llywelyn, as well as third cousin to Rhys ap Maredudd and first cousin to Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.

Mortimer involved himself deeply in the affairs of Pura Wallia at this time. A few months later, on 9 October, he met Prince Llywelyn at Mortimer’s castle at Radnor and entered into a ‘peace treaty and unbreakable agreement’ with his kinsman and old rival. This was probably on Llywelyn’s instigation and meant to secure Mortimer’s support against Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn. Or was there more to it?

Llywelyn was the son of Gruffydd, whom Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth had barred from the succession to Gwynedd on the grounds that he was the son of a ‘slave girl’; this was so Prince Llywelyn could put aside his first wife and marry Joan Plantagenet, daughter of King John. Roger Mortimer, on the other hand, was the grandson of the illegitimate but legitimised Princess Joan, which meant he had the blood of the English and Welsh royal families in his veins.

Roger was also the eldest surviving direct heir of his uncle, Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn. Llywelyn ab Iorwerth had deliberately excluded Grufydd and his brothers from the succession while Prince Dafydd and his bodily heirs lived. Dafydd had died in 1246 without an heir, but he left six uterine sisters. All but one of these had male heirs, of which Mortimer was the eldest. Under Welsh law it was technically impossible for a female to inherit land, but it was not impossible for a member of a royal family to stake a claim through the female line.

There is also the question of how Llywelyn ap Gruffudd rose to power in Gwynedd in the first place. There was no ‘coronation ceremony’ in 1246: instead Llywelyn and his brother Owain Goch seized power after the death of Prince Dafydd. Since they were both sons of a man who had been declared a bastard by Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, neither had any automatic right to inherit.

This may explain why Llywelyn had no male heirs of his body, and made efforts to mend fences with Mortimer in 1281. Did Llywelyn intend to hand the crown of Wales over to his cousin Mortimer? His brother Dafydd was an outcast at this point, while Owain was in prison and Rhodri had sold off his rights to the principality.

Prince Rosser ap Ralf ap Llywelyn of Wales?

The first name on the witness list to the charter is Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, the only ‘Englishman’ among the otherwise Welsh names. The Anglicised form of Mortimer’s name is deceptive: he was a grandson of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth and a nephew of Dafydd ap Llywelyn, as well as third cousin to Rhys ap Maredudd and first cousin to Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.

Mortimer involved himself deeply in the affairs of Pura Wallia at this time. A few months later, on 9 October, he met Prince Llywelyn at Mortimer’s castle at Radnor and entered into a ‘peace treaty and unbreakable agreement’ with his kinsman and old rival. This was probably on Llywelyn’s instigation and meant to secure Mortimer’s support against Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn. Or was there more to it?

Llywelyn was the son of Gruffydd, whom Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth had barred from the succession to Gwynedd on the grounds that he was the son of a ‘slave girl’; this was so Prince Llywelyn could put aside his first wife and marry Joan Plantagenet, daughter of King John. Roger Mortimer, on the other hand, was the grandson of the illegitimate but legitimised Princess Joan, which meant he had the blood of the English and Welsh royal families in his veins.

Roger was also the eldest surviving direct heir of his uncle, Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn. Llywelyn ab Iorwerth had deliberately excluded Grufydd and his brothers from the succession while Prince Dafydd and his bodily heirs lived. Dafydd had died in 1246 without an heir, but he left six uterine sisters. All but one of these had male heirs, of which Mortimer was the eldest. Under Welsh law it was technically impossible for a female to inherit land, but it was not impossible for a member of a royal family to stake a claim through the female line.

There is also the question of how Llywelyn ap Gruffudd rose to power in Gwynedd in the first place. There was no ‘coronation ceremony’ in 1246: instead Llywelyn and his brother Owain Goch seized power after the death of Prince Dafydd. Since they were both sons of a man who had been declared a bastard by Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, neither had any automatic right to inherit.

This may explain why Llywelyn had no male heirs of his body, and made efforts to mend fences with Mortimer in 1281. Did Llywelyn intend to hand the crown of Wales over to his cousin Mortimer? His brother Dafydd was an outcast at this point, while Owain was in prison and Rhodri had sold off his rights to the principality.

Prince Rosser ap Ralf ap Llywelyn of Wales?

Published on November 27, 2019 01:43

November 25, 2019

Statute of Wales (first draft)

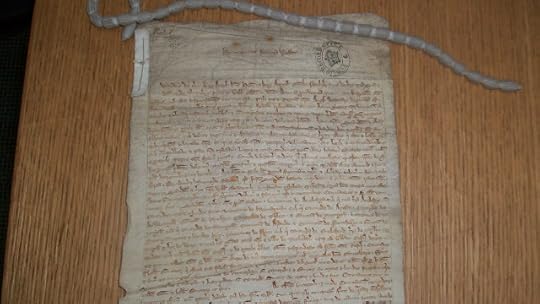

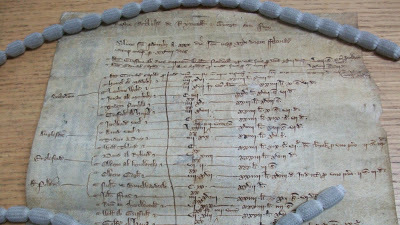

The first draft of the Statute of Wales, photographed by me at the National Archives last week. This is an earlier, separate document to the official version of the statute that was declared at Rhuddlan in 1284. The burnt edges suggest it suffered during a great fire that destroyed many documents in 1731, and the content is different in some respects to the final version of Rhuddlan.

First, the draft shows that Edward I originally contemplated forming four shires in Gwynedd (‘in Snowdon’), with a sheriff of Aberconwy to administer the cantreds of Arllechwedd and Arfon and the commote of Creuddyn; a sheriff of Criccieth to superintend the cantreds of Lleyn and Dunoding; a sheriff of Merioneth, under whom would be the cantred of Merioneth and the commotes of Penllyn and Edeirnion; and a sheriff of Anglesey, who had the whole island under his charge. This arrangement was never carried out in practice.

Second, this early version is almost entirely concerned with the legal aspects of the new administration in Wales, but has not a word to say about the central administrative machinery or how the finances were to operate. According to RR Davies in his book ‘Age of Conquest’, this first draft also refers to the civil aspects of Welsh law being retained at the request of the people of Wales; the allusions to consent, however, were struck out from the final version. I personally could see none of this when I took a squint at the document, and it isn’t mentioned in other academic studies of the draft.

First, the draft shows that Edward I originally contemplated forming four shires in Gwynedd (‘in Snowdon’), with a sheriff of Aberconwy to administer the cantreds of Arllechwedd and Arfon and the commote of Creuddyn; a sheriff of Criccieth to superintend the cantreds of Lleyn and Dunoding; a sheriff of Merioneth, under whom would be the cantred of Merioneth and the commotes of Penllyn and Edeirnion; and a sheriff of Anglesey, who had the whole island under his charge. This arrangement was never carried out in practice.

Second, this early version is almost entirely concerned with the legal aspects of the new administration in Wales, but has not a word to say about the central administrative machinery or how the finances were to operate. According to RR Davies in his book ‘Age of Conquest’, this first draft also refers to the civil aspects of Welsh law being retained at the request of the people of Wales; the allusions to consent, however, were struck out from the final version. I personally could see none of this when I took a squint at the document, and it isn’t mentioned in other academic studies of the draft.

Published on November 25, 2019 05:27

November 24, 2019

The saga of Iorwerth Foel (2)

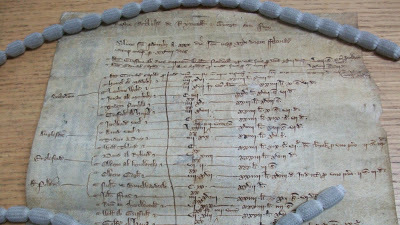

After his desertion of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1278, Iorwerth drops out of sight for the next twenty years. He re-emerges in 1298 as a centenar (mounted officer) in charge of the footsoldiers of Anglesey between November 1297-November 1298. Iorwerth shared his command with three other centenars: Dafydd Foel (possibly a relative), Tudur Ddu - “Black Tudor” - and William Thloyt or Lloyd. The relevant muster roll is attached below.

These men were among the infantry of North Wales raised over the winter of 1297-8 to defend the northern counties of England against Sir William Wallace. Of the 30,000 men of Wales and England summoned to defend the north, only those raised from Anglesey and Snowdon came near to filling their quota: 2000 were summoned and 1939 actually showed up, which was extremely unusual for this campaign.

This meant that Edward I had two Welsh armies in the field at the same time: 6213 archers under his personal command in Flanders, and a total of 5157 in northern England under the command of Earl Warenne. The captain of the Welsh contingent, Gruffudd Llwyd, served under Warenne from 8 December 1297 to 29 January 1298, and was then sent to Flanders from January to March.

Gruffudd was not present at the Battle of Falkirk, fought on 22 August 1298. Iorwerth’s term of service covers the time of the battle, so he may have been present on the killing fields:

“And so the Welsh were held back from attacking the Scots, until the King triumphed and the Scots fell everywhere, like the flowers of the forest as the fruit grows. Then said the King, "If the Lord be with us, who shall be against us?" The Welsh straightway fell upon the Scots and laid them low, so greatly that their corpses covered the field, like the snow in winter.” -

William of Rishanger, Chronica et Annales

These men were among the infantry of North Wales raised over the winter of 1297-8 to defend the northern counties of England against Sir William Wallace. Of the 30,000 men of Wales and England summoned to defend the north, only those raised from Anglesey and Snowdon came near to filling their quota: 2000 were summoned and 1939 actually showed up, which was extremely unusual for this campaign.

This meant that Edward I had two Welsh armies in the field at the same time: 6213 archers under his personal command in Flanders, and a total of 5157 in northern England under the command of Earl Warenne. The captain of the Welsh contingent, Gruffudd Llwyd, served under Warenne from 8 December 1297 to 29 January 1298, and was then sent to Flanders from January to March.

Gruffudd was not present at the Battle of Falkirk, fought on 22 August 1298. Iorwerth’s term of service covers the time of the battle, so he may have been present on the killing fields:

“And so the Welsh were held back from attacking the Scots, until the King triumphed and the Scots fell everywhere, like the flowers of the forest as the fruit grows. Then said the King, "If the Lord be with us, who shall be against us?" The Welsh straightway fell upon the Scots and laid them low, so greatly that their corpses covered the field, like the snow in winter.” -

William of Rishanger, Chronica et Annales

Published on November 24, 2019 06:32

The saga of Iorwerth Foel (1)

Iorwerth Foel was a landholder of Anglesey in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century. His great-great granddaughter was Margaret Hanmer, wife of Owain Glyn Dwr.

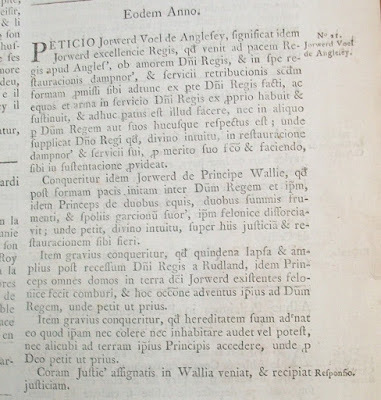

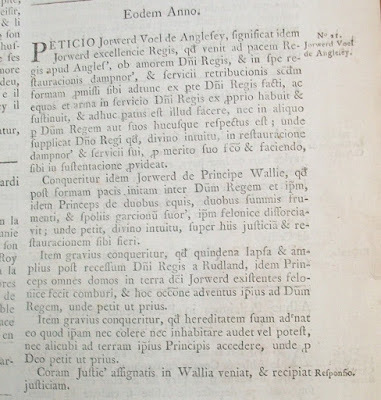

In 1278 Iorwerth presented a petition to parliament (above), complaining that when he had come to the King’s peace and then served the King in war, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd had taken his horses and corn, and the plunder of his men, and therefore Iorwerth claimed justice and restitution. Llywelyn had done these things after the peace of Aberconwy, and hence was guilty of felony. Iorwerth also complained that a fortnight or more after the departure of the King from Rhuddlan, Prince Llywelyn had feloniously burnt all the houses on his land, on account of Iorwerth joining the King’s army. Lastly, he complained that he dared not and could not cultivate nor inhabit his hereditary lands nor approach any part of the land of the Prince. On these complaints he was told to go before the Justices assigned in Wales and receive justice. The final outcome of the plea is unknown.

Prince Llywelyn’s treatment of Iorwerth either suggests he had a short way with dissenters, or was particularly outraged at the defection of one of his closest supporters at a crucial time:

“This case was just one of many which showed that Llywelyn could no longer rely on the support of his own subjects, let alone on that of leading Welshmen outside Gwynedd.” - AD Carr, Medieval Anglesey

In 1278 Iorwerth presented a petition to parliament (above), complaining that when he had come to the King’s peace and then served the King in war, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd had taken his horses and corn, and the plunder of his men, and therefore Iorwerth claimed justice and restitution. Llywelyn had done these things after the peace of Aberconwy, and hence was guilty of felony. Iorwerth also complained that a fortnight or more after the departure of the King from Rhuddlan, Prince Llywelyn had feloniously burnt all the houses on his land, on account of Iorwerth joining the King’s army. Lastly, he complained that he dared not and could not cultivate nor inhabit his hereditary lands nor approach any part of the land of the Prince. On these complaints he was told to go before the Justices assigned in Wales and receive justice. The final outcome of the plea is unknown.

Prince Llywelyn’s treatment of Iorwerth either suggests he had a short way with dissenters, or was particularly outraged at the defection of one of his closest supporters at a crucial time:

“This case was just one of many which showed that Llywelyn could no longer rely on the support of his own subjects, let alone on that of leading Welshmen outside Gwynedd.” - AD Carr, Medieval Anglesey

Published on November 24, 2019 02:11

November 16, 2019

Legal fictions

Serving two masters (6, and last)

The death of the brothers Rhys and Hywel ap Gruffudd in the war of 1282, fighting on opposite sides, left their heirs vulnerable to rival claimants. In about 1307 Rhys’s son, Gruffudd Llwyd, moved to secure his inheritance from Thomas Bek, the predatory Bishop of St David’s. Gruffydd wrote to the council in London and reminded them that:

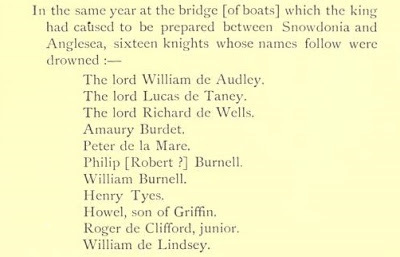

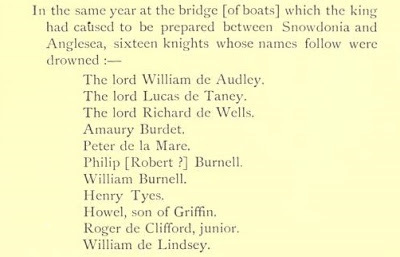

“His uncle, Hywel ap Gruffudd, knight…died in the service of the king, the father of our king, at the bridge of Anglesey, in the company of Sir Otto Grandison in the war of Llywelyn and Dafydd.”

This was true enough, but Gruffudd went further and claimed that: “After the conquest, the said Rhys ap Gruffydd, his brother and father of this Gruffudd [meaning himself], was assigned by the king as guardian of the county of Caernarfon and sworn to his council and in this state he died, as the earl of Lincoln, the said Sir Otto and other great lords of the king’s council can testify.”

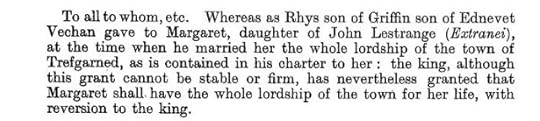

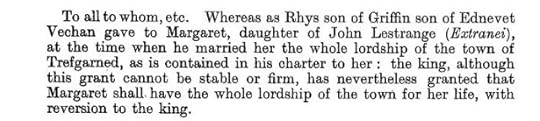

Thus Gruffudd claimed that his father was not killed with Prince Llywelyn at Cilmeri, as the Peterborough chronicler claimed, but survived and was taken back into royal service. Gruffudd’s statement is flatly contradicted by the records. On 20 April 1284 the king allowed Margaret, the wife of Rhys ap Gruffudd, her lordship of Tregarnedd in Anglesey for life. Edward was not happy about the grant, which he regarded as neither “stable or firm”, but it was made over anyway. A few days later, on 4 May, the earl of Lincoln was ordered to deliver Rhys’s lands in the cantref of Rhos over to his son, Gruffudd.

If Rhys was still alive, than neither of the above grants make any sense. He was dead by 20 May 1284 at the latest and almost certainly died at Cilmeri in December 1282. Gruffudd’s claim that his father was made ‘guardian of the county of Caernarfon’ is also bogus, for the shire was not even formed until 3 March 1284, fourteen months after the last possible date his father may have been alive. The only other possibility is that Edward I made Rhys guardian for Caernarfonshire and then forgot to tell anyone, which doesn’t seem likely.

Therefore Gruffudd Llwyd - later Sir Gruffudd Llwyd - tried to persuade Edward II that his father, Rhys, was loyal to Edward I until the end. This legal subterfuge was probably employed to protect Gruffudd’s standing in the edgy conditions of postconquest Wales. With regard to the actual petition, Gruffudd sold his advowson to the church of Llanrhystyd to the Bishop of St David’s in 1309, but held onto the rest of his lands. These were inherited by his son, Ieuan, Justice of South Wales, on 28 August 1335.

The death of the brothers Rhys and Hywel ap Gruffudd in the war of 1282, fighting on opposite sides, left their heirs vulnerable to rival claimants. In about 1307 Rhys’s son, Gruffudd Llwyd, moved to secure his inheritance from Thomas Bek, the predatory Bishop of St David’s. Gruffydd wrote to the council in London and reminded them that:

“His uncle, Hywel ap Gruffudd, knight…died in the service of the king, the father of our king, at the bridge of Anglesey, in the company of Sir Otto Grandison in the war of Llywelyn and Dafydd.”

This was true enough, but Gruffudd went further and claimed that: “After the conquest, the said Rhys ap Gruffydd, his brother and father of this Gruffudd [meaning himself], was assigned by the king as guardian of the county of Caernarfon and sworn to his council and in this state he died, as the earl of Lincoln, the said Sir Otto and other great lords of the king’s council can testify.”

Thus Gruffudd claimed that his father was not killed with Prince Llywelyn at Cilmeri, as the Peterborough chronicler claimed, but survived and was taken back into royal service. Gruffudd’s statement is flatly contradicted by the records. On 20 April 1284 the king allowed Margaret, the wife of Rhys ap Gruffudd, her lordship of Tregarnedd in Anglesey for life. Edward was not happy about the grant, which he regarded as neither “stable or firm”, but it was made over anyway. A few days later, on 4 May, the earl of Lincoln was ordered to deliver Rhys’s lands in the cantref of Rhos over to his son, Gruffudd.

If Rhys was still alive, than neither of the above grants make any sense. He was dead by 20 May 1284 at the latest and almost certainly died at Cilmeri in December 1282. Gruffudd’s claim that his father was made ‘guardian of the county of Caernarfon’ is also bogus, for the shire was not even formed until 3 March 1284, fourteen months after the last possible date his father may have been alive. The only other possibility is that Edward I made Rhys guardian for Caernarfonshire and then forgot to tell anyone, which doesn’t seem likely.

Therefore Gruffudd Llwyd - later Sir Gruffudd Llwyd - tried to persuade Edward II that his father, Rhys, was loyal to Edward I until the end. This legal subterfuge was probably employed to protect Gruffudd’s standing in the edgy conditions of postconquest Wales. With regard to the actual petition, Gruffudd sold his advowson to the church of Llanrhystyd to the Bishop of St David’s in 1309, but held onto the rest of his lands. These were inherited by his son, Ieuan, Justice of South Wales, on 28 August 1335.

Published on November 16, 2019 02:59

November 15, 2019

Brothers in death

Serving two masters (5)

On 8 December 1281, at Aberffraw, Rhys ap Gruffudd was fined £100 by Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd as a punishment for his ‘disobedience and contempt’. No further details are supplied, so we are left to speculate as to the nature of Rhys’s offence.

On 30 December, at Beddgelert, a new arrangement was made between Prince Llywelyn and Rhys. This would suggest tempers had cooled, and the two men settled their disagreement. Rhys, once Llywelyn’s bailiff, had been in English service since 1276. Now he went back to his former master.

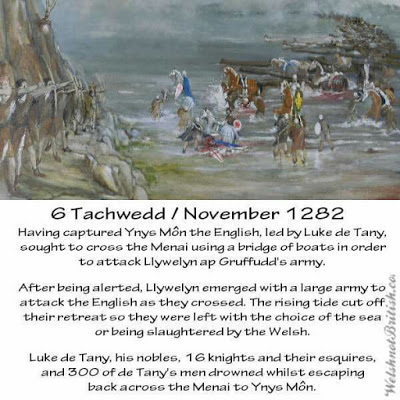

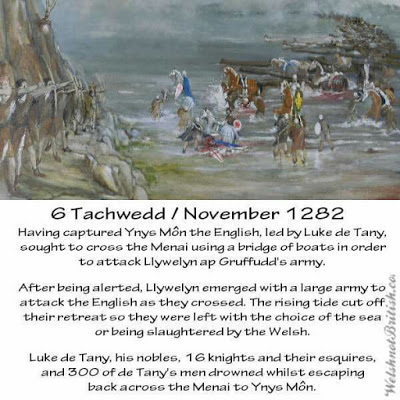

The next winter, 6 November 1282, Rhys’s brother Hywel was drowned at the Battle of the Bridge of Boats on the Menai strait. Hywel had remained a crown loyalist and was put in command of the English fleet on Anglesey:

“And King Edward of England sent a fleet of ships to Anglesey, with Hywel ap Gruffudd ab Ednyfed as leader at their head; and they gained possession of Anglesey. And they desired to gain possession of Arfon. And then was made the bridge over the Menai; but the bridge broke under an excessive load, and countless numbers of the English were drowned, and others were slain”.

- Brut y Tywysogion

Rhys’s feelings, on hearing this news, can only be imagined. Over a month later he joined his brother in death. On 10/11 December, near Cilmeri, Rhys fell beside Prince Llywelyn:

“Furthermore, not one of the prince’s cavalry escaped death, but they were killed with 3000 of the foot and also the three magnates of his land who died with him; namely ‘Almafan’ who was lord of Llanbadarn Fawr, Rhys ap Gruffydd, who was seneschal of all the land of the prince, and thirdly, it is thought, Llywelyn Fychan, who was lord of Bromfield.”

- Chronicle of Peterborough

On 8 December 1281, at Aberffraw, Rhys ap Gruffudd was fined £100 by Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd as a punishment for his ‘disobedience and contempt’. No further details are supplied, so we are left to speculate as to the nature of Rhys’s offence.

On 30 December, at Beddgelert, a new arrangement was made between Prince Llywelyn and Rhys. This would suggest tempers had cooled, and the two men settled their disagreement. Rhys, once Llywelyn’s bailiff, had been in English service since 1276. Now he went back to his former master.

The next winter, 6 November 1282, Rhys’s brother Hywel was drowned at the Battle of the Bridge of Boats on the Menai strait. Hywel had remained a crown loyalist and was put in command of the English fleet on Anglesey:

“And King Edward of England sent a fleet of ships to Anglesey, with Hywel ap Gruffudd ab Ednyfed as leader at their head; and they gained possession of Anglesey. And they desired to gain possession of Arfon. And then was made the bridge over the Menai; but the bridge broke under an excessive load, and countless numbers of the English were drowned, and others were slain”.

- Brut y Tywysogion

Rhys’s feelings, on hearing this news, can only be imagined. Over a month later he joined his brother in death. On 10/11 December, near Cilmeri, Rhys fell beside Prince Llywelyn:

“Furthermore, not one of the prince’s cavalry escaped death, but they were killed with 3000 of the foot and also the three magnates of his land who died with him; namely ‘Almafan’ who was lord of Llanbadarn Fawr, Rhys ap Gruffydd, who was seneschal of all the land of the prince, and thirdly, it is thought, Llywelyn Fychan, who was lord of Bromfield.”

- Chronicle of Peterborough

Published on November 15, 2019 11:48

Paying suit

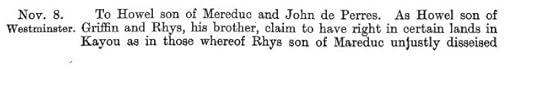

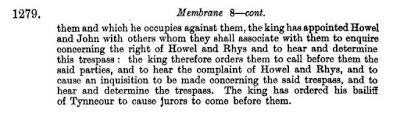

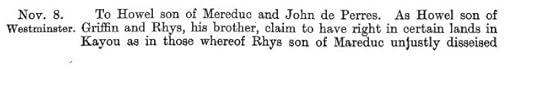

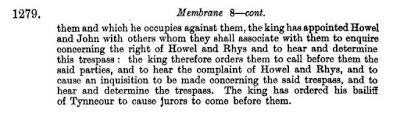

Serving two masters (4) In 1279 the brothers Rhys and Hywel ap Gruffudd lost their lands in Wales. On 8 November the king ordered Hywel ap Maredudd (one of Rhys’s colleagues on the commission to govern Wales) and John Perres to inquire into the rights of the brothers in Caeo, a commote of Cantref Mawr, which they had been unjustly ‘diseissed’ (deprived) of by Rhys ap Maredudd.

This case gives an idea of the chaotic rivalry that existed between the descendants of the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth. Rhys and Hywel were both descended from Lord Rhys via their grandfather’s marriage to his daughter, Gwenllian. Caeo itself was held by Rhys Wyndod, lord of Dinefwr and another descendant. The commote was claimed by Rhys ap Maredudd, lord of Dryslwyn and yet another descendant. Presumably this means that the brothers held their part of Caeo from Rhys Wyndod as chief lord.

Rhys ap Maredudd’s specific complaint was that Hywel ap Maredudd refused to pay suit at Rhys’s court of Llansadwrn. To owe suit required a man to attend a specific court and pay a fee to have his cases heard; Rhys was thus concerned with the loss of prestige and revenue if Hywel was allowed to detach himself from the lord of Dryslwyn’s jurisdiction.

To pay suit was a part of English common law, and Rhys asked the king to have a writ to the royal bailiffs at Dinefwr to distrain Hywel and force him to pay suit, ‘as he was accustomed to do in the time of the father of Rhys’. This all gave rise to an awkward situation in which one of the team of four Welsh justices appointed to govern Wales and the Marches was himself a sub-tenant of a regional lord of Cantref Mawr. This man and his brother also apparently owed legal services to a neighbouring lord of Cantref Mawr, who refused to acknowledge his cousin’s authority in Caeo and did his best to muscle in on the territory. Unfortunately the outcome of the case is unknown.

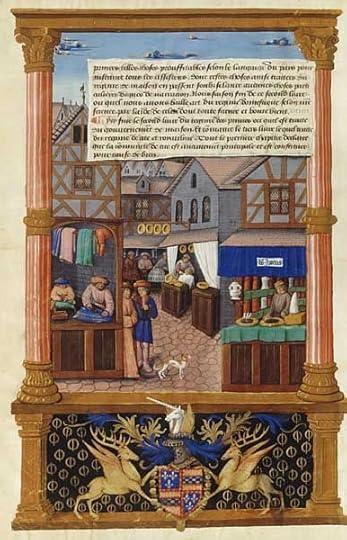

Caeo itself was a fairly important trading centre. A survey of 1303-4 discovered that the hamlet of Cynwil inside Caeo was home to eight ‘chensers’ or censarii, who paid for the privilege of buying and selling freely within the town in weekly markets and annual fairs. The presence of a market at Cynwil is indicated by the collection of petty tolls from people passing through the hamlet. A percentage of these fees and tolls would have been creamed off by the local bigwigs, which might explain why they were all squabbling over possession of the commote.

This case gives an idea of the chaotic rivalry that existed between the descendants of the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth. Rhys and Hywel were both descended from Lord Rhys via their grandfather’s marriage to his daughter, Gwenllian. Caeo itself was held by Rhys Wyndod, lord of Dinefwr and another descendant. The commote was claimed by Rhys ap Maredudd, lord of Dryslwyn and yet another descendant. Presumably this means that the brothers held their part of Caeo from Rhys Wyndod as chief lord.

Rhys ap Maredudd’s specific complaint was that Hywel ap Maredudd refused to pay suit at Rhys’s court of Llansadwrn. To owe suit required a man to attend a specific court and pay a fee to have his cases heard; Rhys was thus concerned with the loss of prestige and revenue if Hywel was allowed to detach himself from the lord of Dryslwyn’s jurisdiction.

To pay suit was a part of English common law, and Rhys asked the king to have a writ to the royal bailiffs at Dinefwr to distrain Hywel and force him to pay suit, ‘as he was accustomed to do in the time of the father of Rhys’. This all gave rise to an awkward situation in which one of the team of four Welsh justices appointed to govern Wales and the Marches was himself a sub-tenant of a regional lord of Cantref Mawr. This man and his brother also apparently owed legal services to a neighbouring lord of Cantref Mawr, who refused to acknowledge his cousin’s authority in Caeo and did his best to muscle in on the territory. Unfortunately the outcome of the case is unknown.

Caeo itself was a fairly important trading centre. A survey of 1303-4 discovered that the hamlet of Cynwil inside Caeo was home to eight ‘chensers’ or censarii, who paid for the privilege of buying and selling freely within the town in weekly markets and annual fairs. The presence of a market at Cynwil is indicated by the collection of petty tolls from people passing through the hamlet. A percentage of these fees and tolls would have been creamed off by the local bigwigs, which might explain why they were all squabbling over possession of the commote.

Published on November 15, 2019 01:13

November 14, 2019

Divide and rule

Serving two masters (3) Via the Treaty of Aberconwy, 9 November 1277, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was required to release his vassal Rhys ap Gruffudd from prison:

“That Llywelyn should free Rhys ap Gruffudd and restore him to the state he occupied when he first came to the lord king and was brought into his peace.”

The clauses of the treaty also required Llywelyn to release Owain ap Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, Dafydd ap Gruffudd ab Owain and his cousin Elise ab Iorwerth, as well as Madog ap Einion. In the next year Rhys ap Gruffudd was serving in the king’s household at a knight’s wage of two shillings a day up until Michaelmas. A month before this, on 18 January 1278, he had been appointed the last member of the judicial branch of three Englishmen and four Welshmen on the Hopton Commission, set up to deal with land claims in Wales.

The clauses of the treaty also required Llywelyn to release Owain ap Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, Dafydd ap Gruffudd ab Owain and his cousin Elise ab Iorwerth, as well as Madog ap Einion. In the next year Rhys ap Gruffudd was serving in the king’s household at a knight’s wage of two shillings a day up until Michaelmas. A month before this, on 18 January 1278, he had been appointed the last member of the judicial branch of three Englishmen and four Welshmen on the Hopton Commission, set up to deal with land claims in Wales.

The make-up of the commission reveals Edward I’s notions of how Wales would be governed post-Aberconwy. His idea was to build up a ministerial elite of loyalist Welshmen who would work alongside a roughly equal number of English officials to administer Wales on the king’s behalf. He would later attempt to do something very similar in Scotland, with an equal number of Scots and Englishmen appointed as councillors and sheriffs.

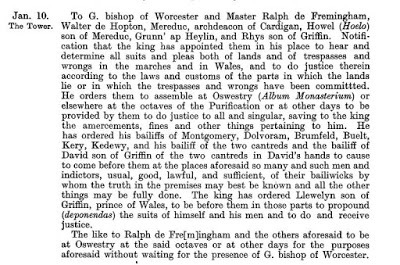

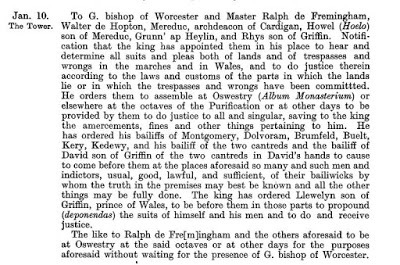

In Wales these ministers were drawn from the uchelwyr - the landholding class below the rank of prince - and the Welsh church. This was at the expense of the princes, not least Llywelyn himself. There was an element of divide and rule here: by promoting the uchelwyr over the princes, the king created a base of native support in Wales while ensuring that the two classes were opposed to each other. In a move that would have shocked Prince Llywelyn, on 10 January 1278 Edward ordered him to appear before the new commission:

“The king has ordered Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd of Wales to be before them in those parts to propound the suits of himself and his men and to do and receive jusice”.

The members of this commission were Rhys ap Gruffudd, Archdeacon Maredudd of Cardigan, Hywel ap Maredudd and Goronwy ap Heilyn. All four had once been Llywelyn’s vassals, and now he was required to appear before them as his judges. Perhaps to reconcile Llywelyn, in June the king ordered that the remit of the commission should be widened to cover the English counties of Herefordshire, Staffordshire and Shropshire. Thus a team of Welsh justices were given effective jurisdiction over Wales and a big chunk of western England.

On 20 June 1278 Edward went further, and ordered that the four Welshmen on the team of seven should be given exclusive rights to hear and determine all pleas in Wales and the Marches. The English head of the commission, Walter of Hopton, was required to take their oath in his place. This act shows the extraordinary faith Edward placed in the Welshmen on the commission, two of which had been in rebellion against him within the past year.

“That Llywelyn should free Rhys ap Gruffudd and restore him to the state he occupied when he first came to the lord king and was brought into his peace.”

The clauses of the treaty also required Llywelyn to release Owain ap Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, Dafydd ap Gruffudd ab Owain and his cousin Elise ab Iorwerth, as well as Madog ap Einion. In the next year Rhys ap Gruffudd was serving in the king’s household at a knight’s wage of two shillings a day up until Michaelmas. A month before this, on 18 January 1278, he had been appointed the last member of the judicial branch of three Englishmen and four Welshmen on the Hopton Commission, set up to deal with land claims in Wales.

The clauses of the treaty also required Llywelyn to release Owain ap Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, Dafydd ap Gruffudd ab Owain and his cousin Elise ab Iorwerth, as well as Madog ap Einion. In the next year Rhys ap Gruffudd was serving in the king’s household at a knight’s wage of two shillings a day up until Michaelmas. A month before this, on 18 January 1278, he had been appointed the last member of the judicial branch of three Englishmen and four Welshmen on the Hopton Commission, set up to deal with land claims in Wales. The make-up of the commission reveals Edward I’s notions of how Wales would be governed post-Aberconwy. His idea was to build up a ministerial elite of loyalist Welshmen who would work alongside a roughly equal number of English officials to administer Wales on the king’s behalf. He would later attempt to do something very similar in Scotland, with an equal number of Scots and Englishmen appointed as councillors and sheriffs.

In Wales these ministers were drawn from the uchelwyr - the landholding class below the rank of prince - and the Welsh church. This was at the expense of the princes, not least Llywelyn himself. There was an element of divide and rule here: by promoting the uchelwyr over the princes, the king created a base of native support in Wales while ensuring that the two classes were opposed to each other. In a move that would have shocked Prince Llywelyn, on 10 January 1278 Edward ordered him to appear before the new commission:

“The king has ordered Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd of Wales to be before them in those parts to propound the suits of himself and his men and to do and receive jusice”.

The members of this commission were Rhys ap Gruffudd, Archdeacon Maredudd of Cardigan, Hywel ap Maredudd and Goronwy ap Heilyn. All four had once been Llywelyn’s vassals, and now he was required to appear before them as his judges. Perhaps to reconcile Llywelyn, in June the king ordered that the remit of the commission should be widened to cover the English counties of Herefordshire, Staffordshire and Shropshire. Thus a team of Welsh justices were given effective jurisdiction over Wales and a big chunk of western England.

On 20 June 1278 Edward went further, and ordered that the four Welshmen on the team of seven should be given exclusive rights to hear and determine all pleas in Wales and the Marches. The English head of the commission, Walter of Hopton, was required to take their oath in his place. This act shows the extraordinary faith Edward placed in the Welshmen on the commission, two of which had been in rebellion against him within the past year.

Published on November 14, 2019 05:10