David Pilling's Blog, page 44

October 26, 2019

Back to the border (6)

Two notable records exist of the English army that rumbled into the Scottish west march in the summer of 1300. One is the Galloway Roll, the earliest armorial of its type that records the names of 251 knights bachelor and men-at-arms and the retinues they served in. The other is The Siege of Caerlaverock, a lengthy rhyme, probably composed by a herald of the royal army, that describes the siege of Caerlaverock Castle near Dumfries.

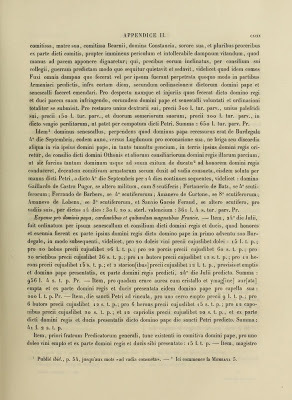

A single copy of the Galloway Roll survives and is held at the College of Arms (pictured). The original is long gone, and the copy was made by Thomas Wriothesley, garter king of arms, in the early sixteenth century. The copy is still a remarkable document, a facsimile of an original roll that was drawn up just three weeks after the siege at Caerlaverock had ended. The herald probably drew up the roll by sight, and the timing suggests he witnessed the English army draw up for battle on the banks of the river Cree in August.

The arms on the rolls are blazoned (described) rather than drawn, which suggests that he quickly jotted down the arms he saw in each division before compiling a complete list later. Such visual identification would have come naturally to a practiced herald or minstrel. Many of the individuals named on the roll can be cross-referenced with other sources. John de Merk, for instance, had served as a centenar (mounted officer) of a thousand Cheshire infantry in the war in Wales in 1294-5. He served in Flanders in 1297 and at the battle of Falkirk in 1298, where his horse was killed under him when the English cavalry charged the Scottish schiltrons. John de Fulbourne had served at the head of a company of Anglo-Welsh infantry in Ireland, and been captured by the O’Connors; he was ransomed by the king just in time to be thrown into the Scottish wars.

The Galloway roll also gives a snapshot of the state of the English military ‘community’ at this time. By 1300 England had been at war, on and off, for almost thirty years. The survivors formed the nucleus of the English cavalry force; of the 251 named knights whose armes were blazoned, 78 were veterans whose record of service went all the way back to the first Welsh war of 1276. They were outnumbered two to one by relative newbies who had first served in the invasion of Scotland in 1296. Yet the latter could hardly be described as novices: between 1296-1300 the English were constantly at war in Scotland, Flanders and Gascony, so these boys had to grow up very quickly.

A single copy of the Galloway Roll survives and is held at the College of Arms (pictured). The original is long gone, and the copy was made by Thomas Wriothesley, garter king of arms, in the early sixteenth century. The copy is still a remarkable document, a facsimile of an original roll that was drawn up just three weeks after the siege at Caerlaverock had ended. The herald probably drew up the roll by sight, and the timing suggests he witnessed the English army draw up for battle on the banks of the river Cree in August.

The arms on the rolls are blazoned (described) rather than drawn, which suggests that he quickly jotted down the arms he saw in each division before compiling a complete list later. Such visual identification would have come naturally to a practiced herald or minstrel. Many of the individuals named on the roll can be cross-referenced with other sources. John de Merk, for instance, had served as a centenar (mounted officer) of a thousand Cheshire infantry in the war in Wales in 1294-5. He served in Flanders in 1297 and at the battle of Falkirk in 1298, where his horse was killed under him when the English cavalry charged the Scottish schiltrons. John de Fulbourne had served at the head of a company of Anglo-Welsh infantry in Ireland, and been captured by the O’Connors; he was ransomed by the king just in time to be thrown into the Scottish wars.

The Galloway roll also gives a snapshot of the state of the English military ‘community’ at this time. By 1300 England had been at war, on and off, for almost thirty years. The survivors formed the nucleus of the English cavalry force; of the 251 named knights whose armes were blazoned, 78 were veterans whose record of service went all the way back to the first Welsh war of 1276. They were outnumbered two to one by relative newbies who had first served in the invasion of Scotland in 1296. Yet the latter could hardly be described as novices: between 1296-1300 the English were constantly at war in Scotland, Flanders and Gascony, so these boys had to grow up very quickly.

Published on October 26, 2019 05:01

October 24, 2019

Back to the border (5)

Over the winter of 1299-1300, the English continued to lose ground in the western marches of Scotland. Their main problem was the Scottish garrison at Caerlaverock, which launched a series of attacks on the rival English garrison at Lochmaben, about seventeen miles to the north.

Caerlaverock

Caerlaverock

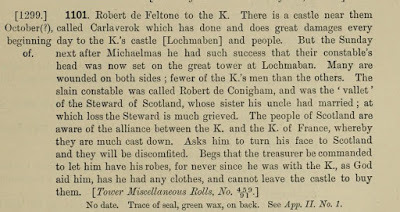

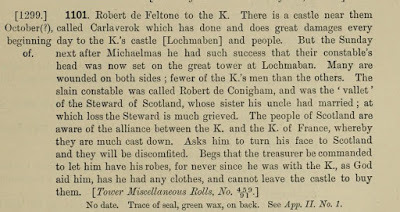

On 4 October 1299 the Scots sallied out of Caerlaverock and attempted to storm Lochmaben. Robert Felton, the English constable of Lochmaben, reported to Edward I that he had repelled the Scots and killed the constable of Caerlaverock, Robert Cunningham. As a symbol of his ‘great success’, Felton stuck Cunningham’s head on the great tower of Lochmaben.

Felton then gave the game away by admitting that he was unable to venture out of Lochmaben to buy a new robe for himself. If he had won such a great victory, why was he stranded inside his outpost, begging the king to come and rescue him? The payrolls for the English garrison paint an equally bleak picture. Between 28 September and 19 October, their numbers were cut from a total strength of 303 to 141, including the loss of several officers. Between 20 October and 19 November this number was reduced again to 101.

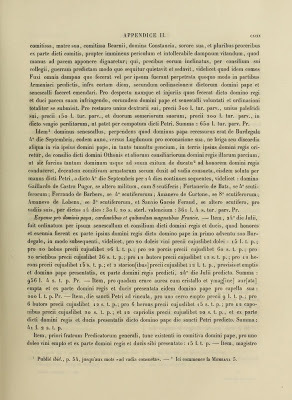

The letter from Felton

The letter from Felton

It is always difficult to account for decrease in garrison numbers, but the likelihood is that most of these men were casualties. The slightly desperate tone of Felton’s letter, pleading with the king ‘to turn his face towards Scotland’, implies that Lochmaben was in serious danger.

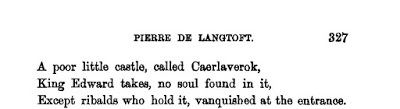

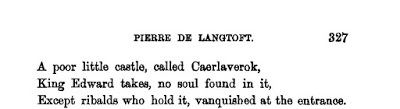

Peter Langtoft, a rabidly pro-English chronicler, poured scorn on the garrison at Caerlaverock. He claimed it was a ‘poor little castle’ occupied by a few insignificant ‘ribalds’. On the contrary, it was an important Scottish strongpoint and a major thorn in the side of the English in the west.

Edward was certainly under no illusions. As early as late August 1299 - even before he received Felton’s report - the king placed Sir John Dolive in charge of the construction of siege engines at Carlisle. These were intended for the assault on Caerlaverock in the summer and named Belfry, Multon and the Cat. Belfry was an enormous siege tower and, along with War-Wolf, would become one of Edward’s favourite toys. When in doubt, build a really big siege tower.

Caerlaverock

CaerlaverockOn 4 October 1299 the Scots sallied out of Caerlaverock and attempted to storm Lochmaben. Robert Felton, the English constable of Lochmaben, reported to Edward I that he had repelled the Scots and killed the constable of Caerlaverock, Robert Cunningham. As a symbol of his ‘great success’, Felton stuck Cunningham’s head on the great tower of Lochmaben.

Felton then gave the game away by admitting that he was unable to venture out of Lochmaben to buy a new robe for himself. If he had won such a great victory, why was he stranded inside his outpost, begging the king to come and rescue him? The payrolls for the English garrison paint an equally bleak picture. Between 28 September and 19 October, their numbers were cut from a total strength of 303 to 141, including the loss of several officers. Between 20 October and 19 November this number was reduced again to 101.

The letter from Felton

The letter from FeltonIt is always difficult to account for decrease in garrison numbers, but the likelihood is that most of these men were casualties. The slightly desperate tone of Felton’s letter, pleading with the king ‘to turn his face towards Scotland’, implies that Lochmaben was in serious danger.

Peter Langtoft, a rabidly pro-English chronicler, poured scorn on the garrison at Caerlaverock. He claimed it was a ‘poor little castle’ occupied by a few insignificant ‘ribalds’. On the contrary, it was an important Scottish strongpoint and a major thorn in the side of the English in the west.

Edward was certainly under no illusions. As early as late August 1299 - even before he received Felton’s report - the king placed Sir John Dolive in charge of the construction of siege engines at Carlisle. These were intended for the assault on Caerlaverock in the summer and named Belfry, Multon and the Cat. Belfry was an enormous siege tower and, along with War-Wolf, would become one of Edward’s favourite toys. When in doubt, build a really big siege tower.

Published on October 24, 2019 04:58

October 23, 2019

Longsword 5!

The fifth instalment in my Longsword series - Longsword (V): The King’s Rebels - is now available on Kindle!

1277 AD. England prepares for war. Prince Llywelyn of Wales refuses to swear loyalty to the king, Edward I, and dreams of independence for his country. To defy the might of the English crown, Llywelyn will need allies. He looks to the west, to Ireland, where the rebellious Clan MacMurrough plan to set up their chieftain as High King. Together, the Welsh and Irish leaders plan to drive Edward’s forces from their land.

Sir Hugh Longsword is summoned by the king to deal with the crisis. With enemies at home thirsting for his blood, he is only too grateful to be sent to Ireland. There he encounters the galloglass, ferocious Gaelic warriors who will fight to the last man on the battlefield. Hugh has survived civil war in England, but will need all his skill and experience to survive the hell of Irish warfare.

Meanwhile an old friend is at work in Wales. Emma, the girl Hugh once rescued, is also working as a spy for the crown. As he fights in Ireland, she is ordered to break up the confederacy of Welsh princes. United, the king’s rebels may well be strong enough to overcome the English. Divided, King Edward can pick them off one by one. Yet, even as the clouds of war gather on every front, an old threat lurks in the background…

Longsword V: The King’s Rebels is the latest historical adventure novel by David Pilling, author of Reiver, Soldier of Fortune, The Half-Hanged Man, Caesar’s Sword and many more novels and short stories.

Longsword (V): The King's Rebels on Amazon US

Longsword (V): The King's Rebels on Amazon UK

1277 AD. England prepares for war. Prince Llywelyn of Wales refuses to swear loyalty to the king, Edward I, and dreams of independence for his country. To defy the might of the English crown, Llywelyn will need allies. He looks to the west, to Ireland, where the rebellious Clan MacMurrough plan to set up their chieftain as High King. Together, the Welsh and Irish leaders plan to drive Edward’s forces from their land.

Sir Hugh Longsword is summoned by the king to deal with the crisis. With enemies at home thirsting for his blood, he is only too grateful to be sent to Ireland. There he encounters the galloglass, ferocious Gaelic warriors who will fight to the last man on the battlefield. Hugh has survived civil war in England, but will need all his skill and experience to survive the hell of Irish warfare.

Meanwhile an old friend is at work in Wales. Emma, the girl Hugh once rescued, is also working as a spy for the crown. As he fights in Ireland, she is ordered to break up the confederacy of Welsh princes. United, the king’s rebels may well be strong enough to overcome the English. Divided, King Edward can pick them off one by one. Yet, even as the clouds of war gather on every front, an old threat lurks in the background…

Longsword V: The King’s Rebels is the latest historical adventure novel by David Pilling, author of Reiver, Soldier of Fortune, The Half-Hanged Man, Caesar’s Sword and many more novels and short stories.

Longsword (V): The King's Rebels on Amazon US

Longsword (V): The King's Rebels on Amazon UK

Published on October 23, 2019 00:35

October 22, 2019

Back to the border (4)

On 10 May 1300 the Scottish parliament held at Rutherglen broke up due to the non-appearance of the Earl of Buchan, because he was “away in Galloway to treat with the Gallovidians”. Without his presence and other “great men of Scotland”, there was no point in the assembly going ahead, so it was adjourned until December.

Caerlaverock

Caerlaverock

This was all contained in a report from Sir John Kingston, the English constable of Edinburgh castle, to Edward I. Buchan was trying to win the loyalty of the Gallovidians, who had always resisted attempts by the kings of Scots to do away with their separate laws and customs: it wasn’t just the Plantagenets and the Capets who sought to stamp their authority on neighbouring regions in this era.

In 1296 Edward had tried to exploit this separatism by wheeling out Thomas of Galloway, bastard son of the last ‘Celtic’ lord of Galloway, who had been in prison for sixty years. The poor old sod was eighty-eight years old. Edward sent him home to Galloway with a charter of liberties on offer to the men of Galloway, calculated to win their support for the English crown. The ploy succeeded to an extent as the most important families in Galloway, the MacCanns and the MacDoualls, fought for Edward in the next decade. That said, many other Gallovidians joined William Wallace.

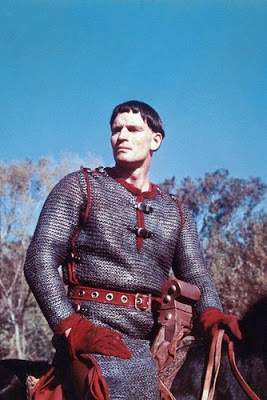

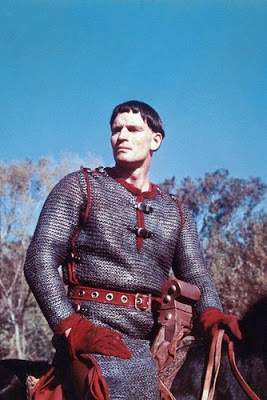

Chuck Heston

Chuck Heston

The charter of liberties was one of Edward’s favourite strategems. After the second conquest of Wales in 1295 he undermined the Marcher lords by issuing similar charters to Welsh communities; it was an easy way to win the popular vote while making his political opponents look like petty tyrants.

Sir William Wallace

Sir William Wallace

In this context, the king must have been alarmed to hear of Buchan sowing seeds in Galloway. Control of the western marches of Scotland was already in flux, with two competing wardens and rival garrisons at Lochmaben and Dumfries (English) and Caerlaverock (Scottish). Edward had been aware of the threat of Caerlaverock since 1299, when he ordered siege engines to be constructed to reduce the castle.

With all the above at stake, there was nothing else for it: the sixty-one year old king had to strap on that damned dirty armour yet again and haul his ageing guts up to the border.*

*The ‘damned dirty armour’ is a quote from Charlton Heston in The War Lord, hence the pic.

Caerlaverock

CaerlaverockThis was all contained in a report from Sir John Kingston, the English constable of Edinburgh castle, to Edward I. Buchan was trying to win the loyalty of the Gallovidians, who had always resisted attempts by the kings of Scots to do away with their separate laws and customs: it wasn’t just the Plantagenets and the Capets who sought to stamp their authority on neighbouring regions in this era.

In 1296 Edward had tried to exploit this separatism by wheeling out Thomas of Galloway, bastard son of the last ‘Celtic’ lord of Galloway, who had been in prison for sixty years. The poor old sod was eighty-eight years old. Edward sent him home to Galloway with a charter of liberties on offer to the men of Galloway, calculated to win their support for the English crown. The ploy succeeded to an extent as the most important families in Galloway, the MacCanns and the MacDoualls, fought for Edward in the next decade. That said, many other Gallovidians joined William Wallace.

Chuck Heston

Chuck HestonThe charter of liberties was one of Edward’s favourite strategems. After the second conquest of Wales in 1295 he undermined the Marcher lords by issuing similar charters to Welsh communities; it was an easy way to win the popular vote while making his political opponents look like petty tyrants.

Sir William Wallace

Sir William WallaceIn this context, the king must have been alarmed to hear of Buchan sowing seeds in Galloway. Control of the western marches of Scotland was already in flux, with two competing wardens and rival garrisons at Lochmaben and Dumfries (English) and Caerlaverock (Scottish). Edward had been aware of the threat of Caerlaverock since 1299, when he ordered siege engines to be constructed to reduce the castle.

With all the above at stake, there was nothing else for it: the sixty-one year old king had to strap on that damned dirty armour yet again and haul his ageing guts up to the border.*

*The ‘damned dirty armour’ is a quote from Charlton Heston in The War Lord, hence the pic.

Published on October 22, 2019 04:08

October 21, 2019

Back to the border (3)

One of the problems with maintaining garrisons in Scotland - or anywhere a long way from one’s economic base - was lack of supplies. In medieval England food was raised for soldiers in wartime via the laws of purveyance and prise. What were these? In brief:

Purveyance: the king’s agents take all your food and goods and promise to pay for it later.

Prise: they take all your food and goods and don’t pay for it at all. Hence the term to ‘prise’ or exact.

In 1300 the English garrisons in the Scottish west march were suffering from a lack of victuals. On 2 May Edward I wrote to his treasurer, expressing concern that the supplies at Carlisle were nearly all used up. Therefore the treasurer was to order purveyance in Ireland, to be sent to Carlisle by 24 June. In the last decade of the reign Edward turned increasingly to Ireland to shore up his position in Scotland, milking the country of men, money and food.

The Scots did their best to make the situation worse (or better from their point of view), attacking the already overstretched English supply lines. For instance, they ambushed a supply train on its way from Silloth, on the west coast of Carlisle, to the English garrison at Lochmaben castle (pictured). Two carts and seven horses were taken, along with a consignment of wine.

At the same time there were supply problems in the east. Edward’s position was technically strongest here, since he had garrisons at Berwick and Edinburgh. Yet in March the warden of the east march, Sir Robert Fitz Roger, reported his need of ‘a great store of victuals’ to support his men at Berwick and elsewhere.

There was more bad news for the king. Skirmishes were fought against the Scots up and down the border line: one engagement at Hawick saw the English lose five horses. Outside of their fortified strongpoints, the English garrisons enjoyed little security. In May Sir John Kingston, the constable of Edinburgh castle, reported that the Scots had held a parliament at Rutherglen, south of Glasgow. This was deeply worrying for Edward: if his enemies could hold parliaments so far south, his control of the land really was slipping.

The bright spot for Edward was that the Guardians had fallen out with each other (again). This was probably another outbreak of the Bruce/Comyn feud, in which Sir John Comyn declared he would no longer serve as Guardian alongside Robert de Bruce and his supporters. The other Guardians agreed, and Bruce was ousted in favour of Ingram de Umfraville, a strong Balliol-Comyn supporter.

Even so, it was clear that Edward was going to have come north yet again to re-impose his authority. Like his cousin Philip le Bel in Flanders, he was finding out the hard way that it was one thing to occupy another country, quite another to hold it.

Purveyance: the king’s agents take all your food and goods and promise to pay for it later.

Prise: they take all your food and goods and don’t pay for it at all. Hence the term to ‘prise’ or exact.

In 1300 the English garrisons in the Scottish west march were suffering from a lack of victuals. On 2 May Edward I wrote to his treasurer, expressing concern that the supplies at Carlisle were nearly all used up. Therefore the treasurer was to order purveyance in Ireland, to be sent to Carlisle by 24 June. In the last decade of the reign Edward turned increasingly to Ireland to shore up his position in Scotland, milking the country of men, money and food.

The Scots did their best to make the situation worse (or better from their point of view), attacking the already overstretched English supply lines. For instance, they ambushed a supply train on its way from Silloth, on the west coast of Carlisle, to the English garrison at Lochmaben castle (pictured). Two carts and seven horses were taken, along with a consignment of wine.

At the same time there were supply problems in the east. Edward’s position was technically strongest here, since he had garrisons at Berwick and Edinburgh. Yet in March the warden of the east march, Sir Robert Fitz Roger, reported his need of ‘a great store of victuals’ to support his men at Berwick and elsewhere.

There was more bad news for the king. Skirmishes were fought against the Scots up and down the border line: one engagement at Hawick saw the English lose five horses. Outside of their fortified strongpoints, the English garrisons enjoyed little security. In May Sir John Kingston, the constable of Edinburgh castle, reported that the Scots had held a parliament at Rutherglen, south of Glasgow. This was deeply worrying for Edward: if his enemies could hold parliaments so far south, his control of the land really was slipping.

The bright spot for Edward was that the Guardians had fallen out with each other (again). This was probably another outbreak of the Bruce/Comyn feud, in which Sir John Comyn declared he would no longer serve as Guardian alongside Robert de Bruce and his supporters. The other Guardians agreed, and Bruce was ousted in favour of Ingram de Umfraville, a strong Balliol-Comyn supporter.

Even so, it was clear that Edward was going to have come north yet again to re-impose his authority. Like his cousin Philip le Bel in Flanders, he was finding out the hard way that it was one thing to occupy another country, quite another to hold it.

Published on October 21, 2019 02:29

October 20, 2019

Back to the border (2)

John de St John’s appointment as warden of the Scottish west march in 1300 seems to have put his predecessor’s nose out of joint. This was Sir Robert Clifford, who had served as warden from 25 November 1298 until August 1299. Clifford was ordered to remain in service with thirty men-at-arms under St John, but had to be persuaded to stick around. He was paid a considerable sum of 500 marks for his service from January-June 1300, and allowed to lodge at the new houses he had built in the pele at Lochmaben.

Clifford was also permitted to leave if he had business elsewhere, but only with St John’s permission, and if he left enough men behind to guard the pele. This was no good from Edward I’s perspective: he needed men in Scotland who wanted to serve, not those who had to be forced.

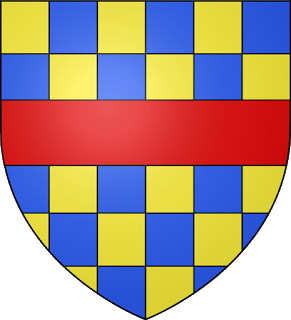

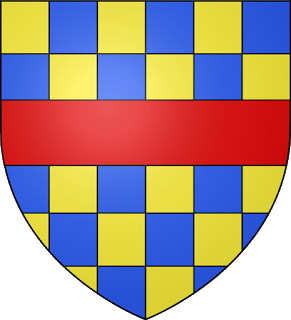

Arms of Clifford

Arms of Clifford

Thus, on 5 January, St John’s men were ordered to muster at Carlisle and “hold themselves in readiness”. What happened next has to be picked out of some very obscure accounts. On 14 February, at Westminster, the king gave offerings in his chapel “because of good rumours in Scotland”. This presumably relates to the actions of St John; the very next day he was ordered to keep at the king’s wages twenty or thirty men-at-arms and as many Irish hobelars as he needed.

On 1 March the new English offensive in Galloway was officially launched. Again a certain lack of enthusiasm can be detected. St John was ordered to “distrain, punish and amerce [fine] all persons who do not obey the summons of the said John to come to the defence of the marches and go against the enemy”. Despite his problems, St John got some results. On 11 March offerings were made in the chapel at Berwick for more “good rumours heard from Scotland”. This probably relates to the capture of Dumfries castle, which on 24 March was granted by the king to Sir John Dolive.

On 1 March the new English offensive in Galloway was officially launched. Again a certain lack of enthusiasm can be detected. St John was ordered to “distrain, punish and amerce [fine] all persons who do not obey the summons of the said John to come to the defence of the marches and go against the enemy”. Despite his problems, St John got some results. On 11 March offerings were made in the chapel at Berwick for more “good rumours heard from Scotland”. This probably relates to the capture of Dumfries castle, which on 24 March was granted by the king to Sir John Dolive.

Otherwise it is difficult to know what St John got up to. On 22 April one of his messengers arrived at Westminster “hastily from parts of Scotland”. Perhaps he brought not-so-good rumours, but then a week later another messenger arrived “to reassure the king of the state of the march”.

Clifford was also permitted to leave if he had business elsewhere, but only with St John’s permission, and if he left enough men behind to guard the pele. This was no good from Edward I’s perspective: he needed men in Scotland who wanted to serve, not those who had to be forced.

Arms of Clifford

Arms of CliffordThus, on 5 January, St John’s men were ordered to muster at Carlisle and “hold themselves in readiness”. What happened next has to be picked out of some very obscure accounts. On 14 February, at Westminster, the king gave offerings in his chapel “because of good rumours in Scotland”. This presumably relates to the actions of St John; the very next day he was ordered to keep at the king’s wages twenty or thirty men-at-arms and as many Irish hobelars as he needed.

On 1 March the new English offensive in Galloway was officially launched. Again a certain lack of enthusiasm can be detected. St John was ordered to “distrain, punish and amerce [fine] all persons who do not obey the summons of the said John to come to the defence of the marches and go against the enemy”. Despite his problems, St John got some results. On 11 March offerings were made in the chapel at Berwick for more “good rumours heard from Scotland”. This probably relates to the capture of Dumfries castle, which on 24 March was granted by the king to Sir John Dolive.

On 1 March the new English offensive in Galloway was officially launched. Again a certain lack of enthusiasm can be detected. St John was ordered to “distrain, punish and amerce [fine] all persons who do not obey the summons of the said John to come to the defence of the marches and go against the enemy”. Despite his problems, St John got some results. On 11 March offerings were made in the chapel at Berwick for more “good rumours heard from Scotland”. This probably relates to the capture of Dumfries castle, which on 24 March was granted by the king to Sir John Dolive.Otherwise it is difficult to know what St John got up to. On 22 April one of his messengers arrived at Westminster “hastily from parts of Scotland”. Perhaps he brought not-so-good rumours, but then a week later another messenger arrived “to reassure the king of the state of the march”.

Published on October 20, 2019 02:12

Back to the border (1)

Shortly after the end of the war in Scotland in 1304, Stephen Brampton, the English constable of Bothwell, sought recompense from Edward I for his ‘painful’ service. Brampton claimed that he had defended Bothwell against the Scots for a year and nine weeks, until all the garrison were dead except himself and a few companions. These were kept in ‘dure prison’ in Scotland for three years.

This probably relates to the year 1300, when the Scots took Stirling, the key to the Forth. It would make sense for them to march onto Bothwell afterwards, and the siege may have begun sometime between January-April 1300. Edward’s intention to campaign in Scotland in 1299, aborted because most of his infantry deserted, gave the Scots a breathing space.

From January 1300 the gears of the English war-machine started to grind again. On 5 January the king wisely appointed John de St John as constable of the troubled West March, where English control was fragile: there was also a competing Scottish constable in the shape of Sir Adam Gordon (no relation to the famous outlaw Adam Gurdon of Hampshire). St John was one of Edward’s most competent lieutenants, and the king had paid an eye-watering ransom of £5000 to get him back from a French prison. St John and his colleague John of Brittany returned from Gascony in time to fight at Falkirk.

St John was given some intriguing private instructions. On 25 September he was paid over £413 in ‘secret expenses’ for performing some mysterious task, probably involving cloaks and daggers. Both English and Scots made effective use of spies, including women and children: one particularly enterprising ‘boy’ seems to have taken money from both sides.

St John also possessed a degree of charm, sorely lacking in most of Edward’s officials in Scotland. The gentry of Gascony had fond memories of his time as seneschal, and flocked to his banner when St John arrived in the duchy to repel the French: they even named a town after him on the edge of the Pyrenees. After the excesses of the vile Cressingham, Edward may have hoped St John would perform a similar trick north of the border.

This probably relates to the year 1300, when the Scots took Stirling, the key to the Forth. It would make sense for them to march onto Bothwell afterwards, and the siege may have begun sometime between January-April 1300. Edward’s intention to campaign in Scotland in 1299, aborted because most of his infantry deserted, gave the Scots a breathing space.

From January 1300 the gears of the English war-machine started to grind again. On 5 January the king wisely appointed John de St John as constable of the troubled West March, where English control was fragile: there was also a competing Scottish constable in the shape of Sir Adam Gordon (no relation to the famous outlaw Adam Gurdon of Hampshire). St John was one of Edward’s most competent lieutenants, and the king had paid an eye-watering ransom of £5000 to get him back from a French prison. St John and his colleague John of Brittany returned from Gascony in time to fight at Falkirk.

St John was given some intriguing private instructions. On 25 September he was paid over £413 in ‘secret expenses’ for performing some mysterious task, probably involving cloaks and daggers. Both English and Scots made effective use of spies, including women and children: one particularly enterprising ‘boy’ seems to have taken money from both sides.

St John also possessed a degree of charm, sorely lacking in most of Edward’s officials in Scotland. The gentry of Gascony had fond memories of his time as seneschal, and flocked to his banner when St John arrived in the duchy to repel the French: they even named a town after him on the edge of the Pyrenees. After the excesses of the vile Cressingham, Edward may have hoped St John would perform a similar trick north of the border.

Published on October 20, 2019 01:40

October 18, 2019

Foix the fail

Gaston I of Foix-Béarn was the 9th Count of Foix and 22nd Viscount of Béarn as well as Co-Prince of Andorra, a landlocked microstate in the Pyrenees sandwiched between France and Spain. His father was Roger the Dodger alias Count Roger-Bernard III of Foix-Béarn, and his mother Marguerite, daughter of the notorious Gaston de Béarn who gave Henry III, Simon de Montfort, Edward I and Philip III so much trouble before he was finally ‘persuaded’ to go to the Holy Land.

Gaston’s namesake and grandson was a chip off the old rotten block. After the final peace was declared between England and France in 1303, he chose to revive his dynastic feud against the house of Armagnac, which had gone into abeyance during the Anglo-French war. He bided his time and finally took up arms in August 1305, just when it looked as though Gascony might recover from the years of conflict. The seneschal, John de Havering, was entertaining the pope at Bordeaux when news reached him of the invasion of Armagnac. A memorandum survives in the form of a medieval ‘newsletter’, describing the outbreak of war:

Item: the lord seneschal, in the city of Bordeaux, received reliable reports that on the 16th day of August the count of Foix had entered the territory of the count of Armagnac with a very great host of armed men, ravaging the said count's homeland and holdings with murder, plundering, and the burning of castles, towns and churches within the realm of the said lord king and duke, in contempt of his kingly honour.

Havering summoned his council. This included the Savoyard knight Othon de Grandson, Edward I’s long-term friend and one of the few survivors of the Bridge of Boats in North Wales in 1282. The Foix-Armagnac war was a far more serious affair than the recent Albert-Caumont affair, and so Havering decided to lead the police operation in person. He raised an army of at least 370 Gascon nobles and their retinues, probably the largest field army seen in Gascony since Henry III’s expedition in 1253.

The seneschal marched against Gaston, ‘to defeat the rebels, to rout these enemies and to set right the aforesaid outrages’. Gaston quickly realised his mistake: his father had profited while England and France were at war, but in time of peace there was no way of playing off one kingdom against another. To save himself he adopted his grandfather’s policy of squealing to a higher authority. As the memorandum states:

When the lord seneschal of Gascony came on with the above-mentioned army in pursuit of the count of Foix and his accomplices, the count foresaw that he could not well escape it, and that he would be taken prisoner and destroyed because of his crimes and outrages. To avoid imminent danger and irresistible ruin, he requested the lord pope, through the mediation of the countess his mother, the countess of Bearn, the lady Constance, his sister, and many nobles on behalf of the said count, to deign to intervene to make peace; he, favouring their supplications, and with the advice of his college, stilled and checked the aforesaid war by the means he proposed, to wit that the count of Foix would, before a set date, cause all the harm which had been done by him or carried out in whatever way by his order in the aforesaid region of Armagnac, to be compensated.

Thus Gaston threw himself on the mercy of Pope Clement, who agreed to protect him from Havering’s wrath so long as he paid war damages. And so all was quiet again. For a while.

Gaston’s namesake and grandson was a chip off the old rotten block. After the final peace was declared between England and France in 1303, he chose to revive his dynastic feud against the house of Armagnac, which had gone into abeyance during the Anglo-French war. He bided his time and finally took up arms in August 1305, just when it looked as though Gascony might recover from the years of conflict. The seneschal, John de Havering, was entertaining the pope at Bordeaux when news reached him of the invasion of Armagnac. A memorandum survives in the form of a medieval ‘newsletter’, describing the outbreak of war:

Item: the lord seneschal, in the city of Bordeaux, received reliable reports that on the 16th day of August the count of Foix had entered the territory of the count of Armagnac with a very great host of armed men, ravaging the said count's homeland and holdings with murder, plundering, and the burning of castles, towns and churches within the realm of the said lord king and duke, in contempt of his kingly honour.

Havering summoned his council. This included the Savoyard knight Othon de Grandson, Edward I’s long-term friend and one of the few survivors of the Bridge of Boats in North Wales in 1282. The Foix-Armagnac war was a far more serious affair than the recent Albert-Caumont affair, and so Havering decided to lead the police operation in person. He raised an army of at least 370 Gascon nobles and their retinues, probably the largest field army seen in Gascony since Henry III’s expedition in 1253.

The seneschal marched against Gaston, ‘to defeat the rebels, to rout these enemies and to set right the aforesaid outrages’. Gaston quickly realised his mistake: his father had profited while England and France were at war, but in time of peace there was no way of playing off one kingdom against another. To save himself he adopted his grandfather’s policy of squealing to a higher authority. As the memorandum states:

When the lord seneschal of Gascony came on with the above-mentioned army in pursuit of the count of Foix and his accomplices, the count foresaw that he could not well escape it, and that he would be taken prisoner and destroyed because of his crimes and outrages. To avoid imminent danger and irresistible ruin, he requested the lord pope, through the mediation of the countess his mother, the countess of Bearn, the lady Constance, his sister, and many nobles on behalf of the said count, to deign to intervene to make peace; he, favouring their supplications, and with the advice of his college, stilled and checked the aforesaid war by the means he proposed, to wit that the count of Foix would, before a set date, cause all the harm which had been done by him or carried out in whatever way by his order in the aforesaid region of Armagnac, to be compensated.

Thus Gaston threw himself on the mercy of Pope Clement, who agreed to protect him from Havering’s wrath so long as he paid war damages. And so all was quiet again. For a while.

Published on October 18, 2019 01:57

October 17, 2019

Clement attitudes

In June 1305 the cardinals at Rome finally agreed to the election of Cardinal Bertand de Got as Pope Clement V. The conclave had been torn apart (again) by rows between French and Italians, Black Guelphs and White, Colonna and Caetani, so the election of Bertrand was a necessary compromise. As a Gascon, he stood aloof from Italian quarrels, and his French sympathies were neatly divided: he was both a subject of Edward I, in the latter’s capacity as Duke of Gascony, and on very friendly terms with Philip le Bel. A mild, clubbable, tea-with-vicar sort of chap.

His first act as pope was to visit his old see at Bordeaux, the capital of Gascony. The seneschal, John de Havering, who had only just crushed a private war in the duchy, tore off his helmet and quickly donned the hat marked ‘diplomacy’ instead. He decided to send a team of envoys to meet Clement at the frontier, presumably to stall him while the English scrambled to make Bordeaux fit for a pope. His expenses included four pieces of rich cloth, two of “cameline’” and two striped, and two lengths of green “sindon” for linings. These were to make robes for himself, his escort of eight knights, and the mayor of Bordeaux.

When the English met the new pope at Saintes, it became clear an even larger armed guard was necessary. Among Clement’s retinue were several French nobles. These included Charles of Valois, who had conquered much of Gascony for the French in 1294 and was hated by the people of Bordeaux for the cruelties he had inflicted on them - the old story of conquerors and oppressed. To save these men from having their throats cut, Havering had to guard them all the way from Saintes to Bordeaux, “benignly, honourably and in quiet”. Throughout their stay at the capital the streets were policed day and night, in case the Bordelais rose up and tried to kill Havering’s French guests. Then word arrived that another private war had erupted in southern Gascony.

Charles of Valois

Charles of Valois

His first act as pope was to visit his old see at Bordeaux, the capital of Gascony. The seneschal, John de Havering, who had only just crushed a private war in the duchy, tore off his helmet and quickly donned the hat marked ‘diplomacy’ instead. He decided to send a team of envoys to meet Clement at the frontier, presumably to stall him while the English scrambled to make Bordeaux fit for a pope. His expenses included four pieces of rich cloth, two of “cameline’” and two striped, and two lengths of green “sindon” for linings. These were to make robes for himself, his escort of eight knights, and the mayor of Bordeaux.

When the English met the new pope at Saintes, it became clear an even larger armed guard was necessary. Among Clement’s retinue were several French nobles. These included Charles of Valois, who had conquered much of Gascony for the French in 1294 and was hated by the people of Bordeaux for the cruelties he had inflicted on them - the old story of conquerors and oppressed. To save these men from having their throats cut, Havering had to guard them all the way from Saintes to Bordeaux, “benignly, honourably and in quiet”. Throughout their stay at the capital the streets were policed day and night, in case the Bordelais rose up and tried to kill Havering’s French guests. Then word arrived that another private war had erupted in southern Gascony.

Charles of Valois

Charles of Valois

Published on October 17, 2019 06:56

October 16, 2019

Mortimer antics

A petition from 1322:

THE WELSH LIEGEMEN OF THE COMMUNITY OF WEST WALES TO THE KING AND COUNCIL:

The lord the King, father of the present King, after the conquest of Wales granted them their laws and customs which they had before the conquest, which are called Cyfraith Hywel, and which they and their ancestors have used in all particulars until the thirteenth year of the present King [1319-20] when Roger de Mortimer, former Justice of Wales, had before him in his Sessions at Llanbadarn, Cardigan, Carmarthen, and Emlyn, introduced the law of England which is unfamiliar to your liege people and entirely contrary to their laws and usages, to the great loss and disinheritance of the same. And the present Justice and Rees ap Gruffydd introduced them in the same manner, as did Sir Roger de Mortimer; wherefore all the people of those parts feel themselves seriously aggrieved, and pray the King that they may have their laws and customs in all particulars as he had granted them after the conquest and that the Justice be commanded to do thus, otherwise they cannot live in those parts.

The petition goes on to list more specific grievances, such as the constables of royal castles in Wales taking beasts without warrant, Welsh people being forced to perform labour services etc.

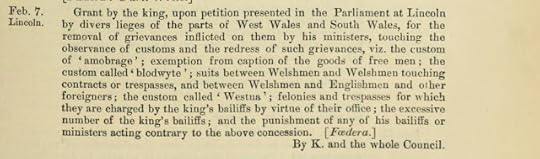

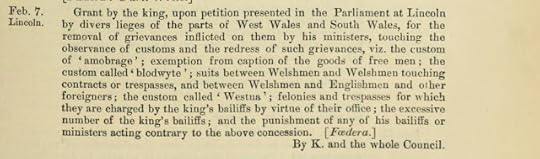

This is one of a stream of complaints from Wales submitted to the parliament of 1321-22. They were all aimed at the abuses committed by Roger Mortimer of Chirk, Justice of Wales, and his nephew Roger Mortimer (the more famous one, executed in 1330). Edward II had previously granted relief from these oppressions in the parliament of 1316 (attached), but it seems the Mortimers chose to ignore the mandate. This is another example of royal ministers doing as they liked in Wales, regardless of what the king said.

The 1316 instruction contains details of the native laws that the Mortimers had repealed in favour of English law. They were:

Amobr: payment due to the lord when a maiden was married or otherwise lose her maidenhood.

Blodwyte: a fine for shedding blood, derived from Anglo-Saxon law.

Gwestfa: a food render supplied to the princely court.

Surprisingly, one of the ministers accused of abuses and removing Welsh law was Rhys ap Gruffudd, a Welsh knight. Overall it seems the Mortimers attempted to govern Wales as a semi-independent state, which fits with their ambitions and antics in this era.

THE WELSH LIEGEMEN OF THE COMMUNITY OF WEST WALES TO THE KING AND COUNCIL:

The lord the King, father of the present King, after the conquest of Wales granted them their laws and customs which they had before the conquest, which are called Cyfraith Hywel, and which they and their ancestors have used in all particulars until the thirteenth year of the present King [1319-20] when Roger de Mortimer, former Justice of Wales, had before him in his Sessions at Llanbadarn, Cardigan, Carmarthen, and Emlyn, introduced the law of England which is unfamiliar to your liege people and entirely contrary to their laws and usages, to the great loss and disinheritance of the same. And the present Justice and Rees ap Gruffydd introduced them in the same manner, as did Sir Roger de Mortimer; wherefore all the people of those parts feel themselves seriously aggrieved, and pray the King that they may have their laws and customs in all particulars as he had granted them after the conquest and that the Justice be commanded to do thus, otherwise they cannot live in those parts.

The petition goes on to list more specific grievances, such as the constables of royal castles in Wales taking beasts without warrant, Welsh people being forced to perform labour services etc.

This is one of a stream of complaints from Wales submitted to the parliament of 1321-22. They were all aimed at the abuses committed by Roger Mortimer of Chirk, Justice of Wales, and his nephew Roger Mortimer (the more famous one, executed in 1330). Edward II had previously granted relief from these oppressions in the parliament of 1316 (attached), but it seems the Mortimers chose to ignore the mandate. This is another example of royal ministers doing as they liked in Wales, regardless of what the king said.

The 1316 instruction contains details of the native laws that the Mortimers had repealed in favour of English law. They were:

Amobr: payment due to the lord when a maiden was married or otherwise lose her maidenhood.

Blodwyte: a fine for shedding blood, derived from Anglo-Saxon law.

Gwestfa: a food render supplied to the princely court.

Surprisingly, one of the ministers accused of abuses and removing Welsh law was Rhys ap Gruffudd, a Welsh knight. Overall it seems the Mortimers attempted to govern Wales as a semi-independent state, which fits with their ambitions and antics in this era.

Published on October 16, 2019 01:34