David Pilling's Blog, page 45

October 15, 2019

Moved by pity

A petition dated c.1307-9:

IORWERTH AP LLYWELYN AND OTHERS TO THE KING AND COUNCIL:

Iorwerth ap Llywelyn and Gruffith ap Adam and Howel ap Adam, heirs of Adam ap David of the County of Meryonneth, that their fathers, in the time of Llywelyn, formerly Prince of Wales, and before the conquest, and in this time of war deceased; whence their lands were extended at the extent and true value; afterwards the King, moved by pity, with regard to the lands of any who were killed or died by any other death against the King in his wars of Wales, by his grace pardoned [gap in letter] granting their lands to men of this sort on better conditions than their fathers and ancestors held them before. Now, however, in spite of the King’s grace, the heirs are constrained by the King’s bailiffs and ministers further to pay that heavy extent, and also the usual extent to which their fathers in their time were wont to pay. Wherefore they pray the King to provide suitable remedy for this.

This relates to the war of Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294-5. According to the Record of Caernarvon, Edward I twice issued a general amnesty towards the heirs of those Welshmen who had died fighting against him: once in 1283, after the capture of Prince Dafydd, and once in 1295, after the defeat of Madog. Whether the king was ‘moved by pity’, or a practical desire to settle Wales as quickly as possible, is a moot point. There was certainly no large-scale expropriation of land from the gentry or uchelwyr class.

Interestingly, this petition and others state that the heirs were granted their lands on more favourable terms than their ancestors had held them under the native princes. This meant reducing the initial rate of payment initially assessed after the conquest. The ‘extent’ referred to is the rent money. However, the king’s ministers then ignored the royal mandate and started demanding the initial rent, and on top of that the rent paid while Prince Llywelyn was still alive. This was fairly typical of English royal government in Wales, in which the administration at local level tended to treat the king's instructions as interesting suggestions.

Interestingly, this petition and others state that the heirs were granted their lands on more favourable terms than their ancestors had held them under the native princes. This meant reducing the initial rate of payment initially assessed after the conquest. The ‘extent’ referred to is the rent money. However, the king’s ministers then ignored the royal mandate and started demanding the initial rent, and on top of that the rent paid while Prince Llywelyn was still alive. This was fairly typical of English royal government in Wales, in which the administration at local level tended to treat the king's instructions as interesting suggestions.

The petitioners were told to bring their complaints before the Chamberlain, but then the trail runs cold.

IORWERTH AP LLYWELYN AND OTHERS TO THE KING AND COUNCIL:

Iorwerth ap Llywelyn and Gruffith ap Adam and Howel ap Adam, heirs of Adam ap David of the County of Meryonneth, that their fathers, in the time of Llywelyn, formerly Prince of Wales, and before the conquest, and in this time of war deceased; whence their lands were extended at the extent and true value; afterwards the King, moved by pity, with regard to the lands of any who were killed or died by any other death against the King in his wars of Wales, by his grace pardoned [gap in letter] granting their lands to men of this sort on better conditions than their fathers and ancestors held them before. Now, however, in spite of the King’s grace, the heirs are constrained by the King’s bailiffs and ministers further to pay that heavy extent, and also the usual extent to which their fathers in their time were wont to pay. Wherefore they pray the King to provide suitable remedy for this.

This relates to the war of Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294-5. According to the Record of Caernarvon, Edward I twice issued a general amnesty towards the heirs of those Welshmen who had died fighting against him: once in 1283, after the capture of Prince Dafydd, and once in 1295, after the defeat of Madog. Whether the king was ‘moved by pity’, or a practical desire to settle Wales as quickly as possible, is a moot point. There was certainly no large-scale expropriation of land from the gentry or uchelwyr class.

Interestingly, this petition and others state that the heirs were granted their lands on more favourable terms than their ancestors had held them under the native princes. This meant reducing the initial rate of payment initially assessed after the conquest. The ‘extent’ referred to is the rent money. However, the king’s ministers then ignored the royal mandate and started demanding the initial rent, and on top of that the rent paid while Prince Llywelyn was still alive. This was fairly typical of English royal government in Wales, in which the administration at local level tended to treat the king's instructions as interesting suggestions.

Interestingly, this petition and others state that the heirs were granted their lands on more favourable terms than their ancestors had held them under the native princes. This meant reducing the initial rate of payment initially assessed after the conquest. The ‘extent’ referred to is the rent money. However, the king’s ministers then ignored the royal mandate and started demanding the initial rent, and on top of that the rent paid while Prince Llywelyn was still alive. This was fairly typical of English royal government in Wales, in which the administration at local level tended to treat the king's instructions as interesting suggestions.The petitioners were told to bring their complaints before the Chamberlain, but then the trail runs cold.

Published on October 15, 2019 05:08

October 14, 2019

Another old soldier

Another petition from an old Welsh soldier, c.1322-34:

RIRID AP CARWET TO THE KING AND COUNCIL:

He served King Edward I in Aragon, Gascony and other places and lands loyally all his days. The said King, after his conquest in the parts of North Wales, ordained and granted to all freemen of those parts to hold from that time forward their lands and tenements of which they were then seised in the same manner as they held them before, as is contained in the Statute of Rhuddlan. Ririd, a free tenant of the King, by this grant, this statute and his ancient seisin, held peaceably after the conquest a fishery near Aberglaslyn in the commote of Eifionydd, as his father and ancestors held it all their times, which fishery is situated in a fresh water river running there, lying between the lands of Ririd on the one part and the other. Notwithstanding this statute, Sir William Trumwyn, formerly sheriff of Caernarvon, came and, without any trespass or forfeit of Ririd, wrongfully and voluntarily deprived and diseissed him of his fishery and took it into the King’s hands; so that from that time, from year to year, the King had received all the issues of the fishery and Riris has been entirely deprived of the same. For which wrong Ririd seeks a remedy.

This is essentially another complaint against Roger Mortimer of Chirk, who held the office of Justice in Wales from 1308-15 and then again from 1316-22. Trumwyn was sheriff of Caernarvon from 1309-14, and would have deprived Ririd of his land under Mortimer’s auspice. Edward II’s response to Ririd’s plea was vague, and it may be the king wished to avoid offending Mortimer. For all his apparent popularity in Wales, Edward had no qualms about re-appointing a notoriously corrupt and oppressive nobleman to govern the Welsh.

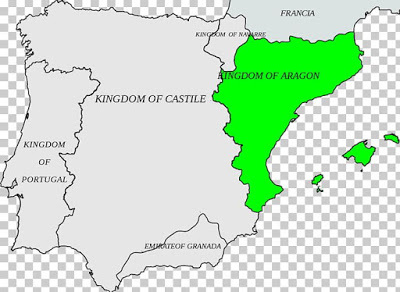

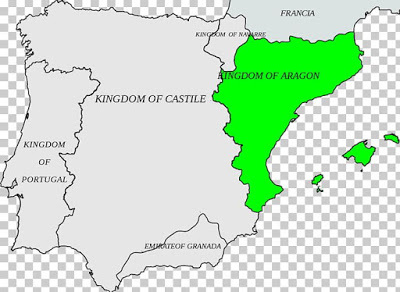

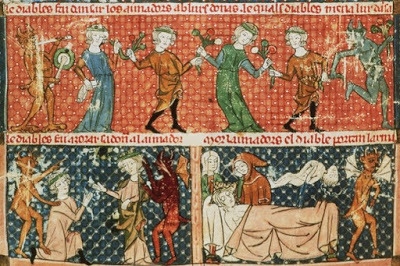

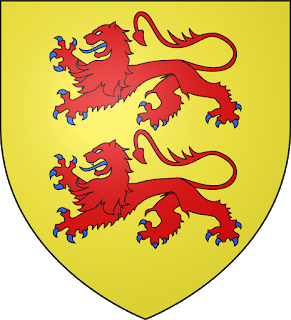

Ririd must have been getting on in years. His claim to have served in Aragon can only relate to 1282-3, when Philip III of France summoned Edward I as his vassal to do military service against the king of Aragon. In 1283 troops were raised in Bordeaux for the campaign, though it isn’t clear whether any were actually sent to Aragon. If Ririd’s petition is correct, at least one Welshman made his way over the Pyrenees (pictured above).

RIRID AP CARWET TO THE KING AND COUNCIL:

He served King Edward I in Aragon, Gascony and other places and lands loyally all his days. The said King, after his conquest in the parts of North Wales, ordained and granted to all freemen of those parts to hold from that time forward their lands and tenements of which they were then seised in the same manner as they held them before, as is contained in the Statute of Rhuddlan. Ririd, a free tenant of the King, by this grant, this statute and his ancient seisin, held peaceably after the conquest a fishery near Aberglaslyn in the commote of Eifionydd, as his father and ancestors held it all their times, which fishery is situated in a fresh water river running there, lying between the lands of Ririd on the one part and the other. Notwithstanding this statute, Sir William Trumwyn, formerly sheriff of Caernarvon, came and, without any trespass or forfeit of Ririd, wrongfully and voluntarily deprived and diseissed him of his fishery and took it into the King’s hands; so that from that time, from year to year, the King had received all the issues of the fishery and Riris has been entirely deprived of the same. For which wrong Ririd seeks a remedy.

This is essentially another complaint against Roger Mortimer of Chirk, who held the office of Justice in Wales from 1308-15 and then again from 1316-22. Trumwyn was sheriff of Caernarvon from 1309-14, and would have deprived Ririd of his land under Mortimer’s auspice. Edward II’s response to Ririd’s plea was vague, and it may be the king wished to avoid offending Mortimer. For all his apparent popularity in Wales, Edward had no qualms about re-appointing a notoriously corrupt and oppressive nobleman to govern the Welsh.

Ririd must have been getting on in years. His claim to have served in Aragon can only relate to 1282-3, when Philip III of France summoned Edward I as his vassal to do military service against the king of Aragon. In 1283 troops were raised in Bordeaux for the campaign, though it isn’t clear whether any were actually sent to Aragon. If Ririd’s petition is correct, at least one Welshman made his way over the Pyrenees (pictured above).

Published on October 14, 2019 11:18

Petitions, petitions

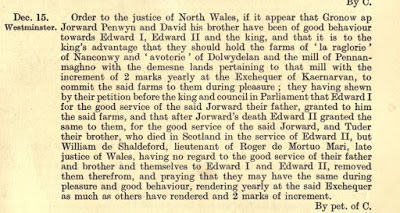

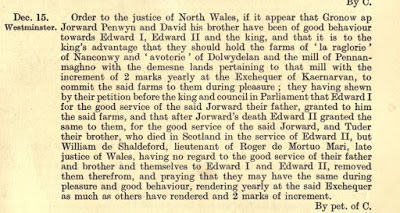

The Calendar of Ancient Petitions relating to Wales contains - as the title suggests - lots of petitions from Welsh individuals and communities to the crown dating from the mid-1200s to the end of the 15th century. They give an insight into the concerns of people a bit lower down the social ladder than the usual lords and princes. They contain some epic family sagas. For instance:

‘Gronow Loit ap y Penwyn to the King and Council: His father served the dead King in the conquest of Wales, and afterwards Thudur, petitioner’s brother, the present King’s esquire, was killed in the battle of Stirling in his service, and also Gronow himself was twice in his expeditions of war and will always be ready, as a faithful and loyal man, for all his commands; wherefore he prays the King to grant him, before all others and for whatever term he shall please, the manor and the mill of Tryverew (Trefriw) in Nantconwy with their appurtenances, at the farm extended in the Exchequer of Caernarvon’.

It is useful to cross-reference these petitions with other records. The Calendar of Fine Rolls states that Gronow’s father, Iorwerth Penwyn, worked as a labourer on Edward I’s castles in North Wales for 86 weeks from November 1285-July 1287, at a wage of 16d (pence) per week. He held the rhaglawry (bailiff) and havotry (cattle farm) of Nantconwy, but after his death these were re-granted to William Schaldeford of Anglesey.

Why did Gronow’s sons not inherit? The Fine Rolls record that William Schaldeford was the lieutenant of Roger Mortimer - he of Mortimer and Isabella fame - and that Gronow and his brothers were robbed of their land by the dastardly Mortimer and his accomplice. This is one of many complaints levied by Welsh communities against Mortimer, a grasping individual even by the standards of his family.

In 1330, after Mortimer fell from power, Gronow came before Edward III and submitted the petition above. It was found that his family had done good service to all three Edwards, and that his brother Thudur had been killed at Bannockburn, or the battle of Stirling as it was known. Gronow was re-granted the rhaglawry of Nantconwy, as well as the havotry at Dolwyddelan, and the mill and demesne lands at Penmachno. He was still farming six acres at Penmachno in 1352.

‘Gronow Loit ap y Penwyn to the King and Council: His father served the dead King in the conquest of Wales, and afterwards Thudur, petitioner’s brother, the present King’s esquire, was killed in the battle of Stirling in his service, and also Gronow himself was twice in his expeditions of war and will always be ready, as a faithful and loyal man, for all his commands; wherefore he prays the King to grant him, before all others and for whatever term he shall please, the manor and the mill of Tryverew (Trefriw) in Nantconwy with their appurtenances, at the farm extended in the Exchequer of Caernarvon’.

It is useful to cross-reference these petitions with other records. The Calendar of Fine Rolls states that Gronow’s father, Iorwerth Penwyn, worked as a labourer on Edward I’s castles in North Wales for 86 weeks from November 1285-July 1287, at a wage of 16d (pence) per week. He held the rhaglawry (bailiff) and havotry (cattle farm) of Nantconwy, but after his death these were re-granted to William Schaldeford of Anglesey.

Why did Gronow’s sons not inherit? The Fine Rolls record that William Schaldeford was the lieutenant of Roger Mortimer - he of Mortimer and Isabella fame - and that Gronow and his brothers were robbed of their land by the dastardly Mortimer and his accomplice. This is one of many complaints levied by Welsh communities against Mortimer, a grasping individual even by the standards of his family.

In 1330, after Mortimer fell from power, Gronow came before Edward III and submitted the petition above. It was found that his family had done good service to all three Edwards, and that his brother Thudur had been killed at Bannockburn, or the battle of Stirling as it was known. Gronow was re-granted the rhaglawry of Nantconwy, as well as the havotry at Dolwyddelan, and the mill and demesne lands at Penmachno. He was still farming six acres at Penmachno in 1352.

Published on October 14, 2019 01:11

October 13, 2019

Little wars

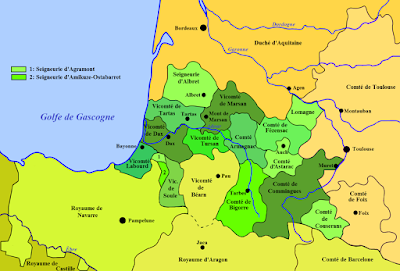

In the summer of 1305 the seneschal of Gascony, John de Havering, was engaged in suppressing a private war between Amanieu d’Albret and the Sire de Caumont. Full details survive for this little campaign, which gives us an insight into how ducal armies were raised and maintained in this era. The war was ignored by chroniclers, possibly because it was an internal affair and shed no particular glory on anyone.

Havering was a no-bullshit government hatchet man who had captured Madog ap Llywelyn in Wales and engineered the recapture of Bordeaux. He raised an army made up of reliable loyalists, most of whom had spent years in exile in England during the Anglo-French war. Such men were unlikely to accept bribes or stab Havering in the back.

The soldiers these men brought are styled in the rolls as ‘militibus’ (knights), ‘scutiferis’ (esquires) and ‘servientibus’ (foot-sergeants). The details of each lord and the strength of his retinue are provided, such as:

Bernard Trencaléon, twenty-three esquires and thirty sergeants

Auger de Pouillon, thirty-four foot-sergeants

Assieu de Galard, eighteen esquires and twenty-five foot-sergeants

Etcetera. Havering gave command of the army to Pons de Castillon, who brought two knights and twelve esquires in his company. The terms of payment are also listed. A baron who served with horses and arms got 4 shillings a day; the knights 2 shillings; the esquires 12 pence; the foot-sergeants 2 pence. Twopence a day was roughly the same earned by a common labourer in this era, so the ordinary soldier wouldn’t expect to get very fat on his wages alone. Hence all the pillaging.

Once he was suited and booted, Pons set off on his mission. First he marched to La Réole on the bank of the Garonne, southeast of Bordeaux. This was always a nest of potential rebels, and Pons saw fit to grab it before the citizens went into revolt. He then marched to the Albret and Caumont strongholds of Casteljaloux and Le Mas, arrested both lords and seized their castles. Albret was imprisoned at Bordeaux and Caumont at La Réole. Meanwhile other ‘malefactors, rebels and disturbers of the peace’ were mopped up and detained in other strongholds held by the king-duke.

The entire operation took twenty-six days and cost a total of £486 and 13 shillings. Much of this expense was taken up by the loss of a single war-horse, which cost £300. A palfrey was also killed, valued at 70 livres tournois. Otherwise the ducal force suffered no casualties.

Job done.

Havering was a no-bullshit government hatchet man who had captured Madog ap Llywelyn in Wales and engineered the recapture of Bordeaux. He raised an army made up of reliable loyalists, most of whom had spent years in exile in England during the Anglo-French war. Such men were unlikely to accept bribes or stab Havering in the back.

The soldiers these men brought are styled in the rolls as ‘militibus’ (knights), ‘scutiferis’ (esquires) and ‘servientibus’ (foot-sergeants). The details of each lord and the strength of his retinue are provided, such as:

Bernard Trencaléon, twenty-three esquires and thirty sergeants

Auger de Pouillon, thirty-four foot-sergeants

Assieu de Galard, eighteen esquires and twenty-five foot-sergeants

Etcetera. Havering gave command of the army to Pons de Castillon, who brought two knights and twelve esquires in his company. The terms of payment are also listed. A baron who served with horses and arms got 4 shillings a day; the knights 2 shillings; the esquires 12 pence; the foot-sergeants 2 pence. Twopence a day was roughly the same earned by a common labourer in this era, so the ordinary soldier wouldn’t expect to get very fat on his wages alone. Hence all the pillaging.

Once he was suited and booted, Pons set off on his mission. First he marched to La Réole on the bank of the Garonne, southeast of Bordeaux. This was always a nest of potential rebels, and Pons saw fit to grab it before the citizens went into revolt. He then marched to the Albret and Caumont strongholds of Casteljaloux and Le Mas, arrested both lords and seized their castles. Albret was imprisoned at Bordeaux and Caumont at La Réole. Meanwhile other ‘malefactors, rebels and disturbers of the peace’ were mopped up and detained in other strongholds held by the king-duke.

The entire operation took twenty-six days and cost a total of £486 and 13 shillings. Much of this expense was taken up by the loss of a single war-horse, which cost £300. A palfrey was also killed, valued at 70 livres tournois. Otherwise the ducal force suffered no casualties.

Job done.

Published on October 13, 2019 01:59

October 12, 2019

Robber knights

In May 1305 a private war erupted in Gascony between the lords of Albret and Caumont. John de Havering, Edward I’s seneschal, reported that ‘the whole duchy was thrown into disorder’ and set about raising an army to quell the disturbance.

The trouble quickly spread to Poitou, Saintonge, Périgord, the Toulousain and Commines. Other families got involved, jumping in one side or another, until Havering was forced to send messengers to the French seneschals of neighbouring areas. They were asked to prevent men-at-arms from those regions from converging on Gascony ‘by reason of the aforesaid wars’.

This was nothing new. Gascony had always been a troublesome, war-torn place. In March 1250 Simon de Montfort, then seneschal, wrote to warn Henry III of the antics of Gascon gentry:

‘...for they will do nothing but rob the lands, and burn and plunder, and put the people to ransom, and ride by night like thieves by thirty or forty in different parts’.

Part of the problem was the slackening of the crusading effort against the infidel. Members of the Gascon nobility had been prominent in the Reconquista in Spain, and the decline of military action on the Iberian peninsula after 1264 left them at a loose end. A few chose to go to Outremer, even after the fall of the last Christian strongholds. As late as 1319 the countess of Foix, Margaret, paid a Béarnais noble of her family to serve in the Holy Land.

The other problem was the proliferation of younger sons among the lesser Gascon gentry. Inheritance laws in the duchy were complex, and cadet or bastard sons often had little to do except fight, booze and screw. Since they were all gentry, these robber knights were often protected by their kinsmen. In 1311, for instance, an outlaw nicknamed ‘Burd’, bastard son of Amanieu de Fossat, was spared the gallows because his father was lieutenant to the seneschal.

The over-population of young gentry folk in Gascony was a serious issue. Castles and manor houses were often shared, which led to some awkward living arrangements. A notarial instrument of April 1288 records that one Raymond-Guillaume was to inherit the hall and living quarters of his father’s castle, while his brother Guillaume was to have the tower. Both were forbidden from making windows, apparently so they didn’t have to look at each other. This custom of shared accommodation, called ‘Condominium’, often led to disputes and yet more private wars.

The trouble quickly spread to Poitou, Saintonge, Périgord, the Toulousain and Commines. Other families got involved, jumping in one side or another, until Havering was forced to send messengers to the French seneschals of neighbouring areas. They were asked to prevent men-at-arms from those regions from converging on Gascony ‘by reason of the aforesaid wars’.

This was nothing new. Gascony had always been a troublesome, war-torn place. In March 1250 Simon de Montfort, then seneschal, wrote to warn Henry III of the antics of Gascon gentry:

‘...for they will do nothing but rob the lands, and burn and plunder, and put the people to ransom, and ride by night like thieves by thirty or forty in different parts’.

Part of the problem was the slackening of the crusading effort against the infidel. Members of the Gascon nobility had been prominent in the Reconquista in Spain, and the decline of military action on the Iberian peninsula after 1264 left them at a loose end. A few chose to go to Outremer, even after the fall of the last Christian strongholds. As late as 1319 the countess of Foix, Margaret, paid a Béarnais noble of her family to serve in the Holy Land.

The other problem was the proliferation of younger sons among the lesser Gascon gentry. Inheritance laws in the duchy were complex, and cadet or bastard sons often had little to do except fight, booze and screw. Since they were all gentry, these robber knights were often protected by their kinsmen. In 1311, for instance, an outlaw nicknamed ‘Burd’, bastard son of Amanieu de Fossat, was spared the gallows because his father was lieutenant to the seneschal.

The over-population of young gentry folk in Gascony was a serious issue. Castles and manor houses were often shared, which led to some awkward living arrangements. A notarial instrument of April 1288 records that one Raymond-Guillaume was to inherit the hall and living quarters of his father’s castle, while his brother Guillaume was to have the tower. Both were forbidden from making windows, apparently so they didn’t have to look at each other. This custom of shared accommodation, called ‘Condominium’, often led to disputes and yet more private wars.

Published on October 12, 2019 04:35

Foix and friends

After the truce of Vives-St Bavon in 1297, whereby England and France agreed to stop fighting for a bit, the Gascons were free to return to their private wars. Count Roger-Bernard had led French troops in Gascony, but now he started to build up alliances against his nephew and enemy, Bertrard of Armagnac.

Philip le Bel, once an enemy of the English, now joined forces with them to put an end to the Foix-Armagnac feud. Three of Edward I’s councillors were invited to the great French parliament at Toulouse in 1304, where the rival families were summoned to explain themselves. There was some serious bling on display:

‘Toulouse, glowing red-rose in the southern winter sunlight, provided a setting worthy of the magnificent assemblage; the king was robed in cloth of gold over purple and gold brocade, sprinkled with the fleur-de-lus, the princes of the blood wore purple cloth of gold, and the constable of France, who bore the king’s sword before him, outshone them all, in his robe of state, divided by strips of gold into blue and red squares with the fleur-de-lis in the center of each one’. -

Esther Rose Clifford, A Knight of Great Renown

All of this show and glitter produced, in Clifford’s words, ‘a very small mouse’: all Philip could do was force the rival parties to exchange the kiss of peace and swear to obey his new law against private warfare. Like hell.

The trigger for the next round of bloodshed was a genuine act of chivalric generosity. Constance of Béarn, a Gascon noblewoman, had defected to the French in the recent war and lost all her lands in England, which were confiscated and given to a Gascon loyalist, Amanieu d’Albret. In September 1304, at the explicit request of Amanieu, Constance was taken back into Edward I’s favour. This meant her lands were taken away from him and restored to her.

Just in case anyone thought Amanieu was going soft, he decided to start a war.

Philip le Bel, once an enemy of the English, now joined forces with them to put an end to the Foix-Armagnac feud. Three of Edward I’s councillors were invited to the great French parliament at Toulouse in 1304, where the rival families were summoned to explain themselves. There was some serious bling on display:

‘Toulouse, glowing red-rose in the southern winter sunlight, provided a setting worthy of the magnificent assemblage; the king was robed in cloth of gold over purple and gold brocade, sprinkled with the fleur-de-lus, the princes of the blood wore purple cloth of gold, and the constable of France, who bore the king’s sword before him, outshone them all, in his robe of state, divided by strips of gold into blue and red squares with the fleur-de-lis in the center of each one’. -

Esther Rose Clifford, A Knight of Great Renown

All of this show and glitter produced, in Clifford’s words, ‘a very small mouse’: all Philip could do was force the rival parties to exchange the kiss of peace and swear to obey his new law against private warfare. Like hell.

The trigger for the next round of bloodshed was a genuine act of chivalric generosity. Constance of Béarn, a Gascon noblewoman, had defected to the French in the recent war and lost all her lands in England, which were confiscated and given to a Gascon loyalist, Amanieu d’Albret. In September 1304, at the explicit request of Amanieu, Constance was taken back into Edward I’s favour. This meant her lands were taken away from him and restored to her.

Just in case anyone thought Amanieu was going soft, he decided to start a war.

Published on October 12, 2019 01:19

October 10, 2019

Foix the fox (4)

On 30 January 1297 Count Roger-Bernard of Foix-Béarn served in the French army at the Battle of Bellegarde or Bonnegarde, where the English under Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, suffered a bad defeat. Bellegarde is usually overshadowed by Stirling Bridge, the other English military disaster in this year, but it was another terrible setback for Edward I. Lacy was in command of the only loyalist field army in Gascony, and his defeat meant there was nothing to stop the French rolling up the last English garrisons in the duchy. Only Edward’s landing in Flanders later in the year, after hurriedly scraping up an army in Wales and nearly causing a civil war in England, saved the handful of remaining loyalist enclaves.

The English king must have had some choice words for Roger-Bernard. In July 1294, shortly after the outbreak of war with France, he had sent his lieutenant and seneschal of Gascony, John de St John, together with John of Brittany to treat with the count. They practically begged him, as the most powerful of the Gascon nobles, to remain loyal to the English crown. Instead he chose the French side after Philip dangled all kinds of treats before his eyes: jurisdiction of Carcassone, various ‘ducal rights’, the constableship of four dioceses and five castles.

At Bellegarde the count personally led the French vanguard against the English, roaring the battle-cry ‘Montjoie!’ and routing the Gascony infantry. He had previously negotiated the surrender of St Sever, an important English stronghold in the middle of the duchy. A whiff of conspiracy hangs over this affair: as soon as the French army withdrew from the siege, the English were allowed to walk straight back in and retake possession. Roger-Bernard apparently stood aside and did nothing, possibly in exchange for a sweet backhander or two.

Some murky details came to light in 1301, when Bernard Saisset, Bishop of Pamiers, was brought to trial before Philip le Bel. During the trial Roger-Bernard turned king’s evidence and claimed that Saisset had tried to persude him to enter into a conspiracy: in return for his help, the Bishop would make him Count of Toulouse and together they would drive the French from south-west France. Coincidentally - or not - the Toulousain was an area repeatedly targeted by the English, implying some kind of secret three-way alliance. At the same time Roger-Bernard was shameless enough to submit a bill of 50,000 livres tournois in unpaid wages to King Philip.

Philip presided over the case in person, and we might imagine him listening to all this in a state of mounting rage and paranoia. Should a king dare to trust anyone in this sinful world? In the end Philip decided he needed Roger-Bernard’s castles and troops more than the bishop’s prayers. The count was acquitted, while Saisset was packed off to prison.

The English king must have had some choice words for Roger-Bernard. In July 1294, shortly after the outbreak of war with France, he had sent his lieutenant and seneschal of Gascony, John de St John, together with John of Brittany to treat with the count. They practically begged him, as the most powerful of the Gascon nobles, to remain loyal to the English crown. Instead he chose the French side after Philip dangled all kinds of treats before his eyes: jurisdiction of Carcassone, various ‘ducal rights’, the constableship of four dioceses and five castles.

At Bellegarde the count personally led the French vanguard against the English, roaring the battle-cry ‘Montjoie!’ and routing the Gascony infantry. He had previously negotiated the surrender of St Sever, an important English stronghold in the middle of the duchy. A whiff of conspiracy hangs over this affair: as soon as the French army withdrew from the siege, the English were allowed to walk straight back in and retake possession. Roger-Bernard apparently stood aside and did nothing, possibly in exchange for a sweet backhander or two.

Some murky details came to light in 1301, when Bernard Saisset, Bishop of Pamiers, was brought to trial before Philip le Bel. During the trial Roger-Bernard turned king’s evidence and claimed that Saisset had tried to persude him to enter into a conspiracy: in return for his help, the Bishop would make him Count of Toulouse and together they would drive the French from south-west France. Coincidentally - or not - the Toulousain was an area repeatedly targeted by the English, implying some kind of secret three-way alliance. At the same time Roger-Bernard was shameless enough to submit a bill of 50,000 livres tournois in unpaid wages to King Philip.

Philip presided over the case in person, and we might imagine him listening to all this in a state of mounting rage and paranoia. Should a king dare to trust anyone in this sinful world? In the end Philip decided he needed Roger-Bernard’s castles and troops more than the bishop’s prayers. The count was acquitted, while Saisset was packed off to prison.

Published on October 10, 2019 06:03

October 9, 2019

Foix the fox (3)

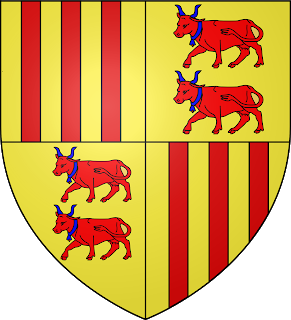

One of the sources of tension between England and France was the comté of Bigorre, on the northern slopes of the Pyrenees and part of the duchy of Gascony. Today it is part of the département of Hautes-Pyrénées, with two small enclaves in the neighbouring Pyrénées Atlantiques.

Philip IV’s intentions towards Gascony were becoming clear as early as 1284. In that year his lawyers challenged Edward I’s right to hold Bigorre free of subjection to the French crown. The English king was technically in the right, since the bishop and chapter of Le Puy in Velay had sold their rights to homage in Bigorre to Henry III in 1253.

The French king’s lawyers thought otherwise. After much nodding and frowning and pursing of lips, the Paris parlement gave Bigorre back to Le Puy. This was in the teeth of Edward’s protests and those of Count Roger-Bernard, who claimed to be acting on behalf of his sister-in-law Constance, daughter of Gaston of Béarn.

(Yes I know this is complicated. Keep up at the back)

Roger-Bernard decided to make a stand and occupied the castle of Vic-de-Bigorre, in defiance of the Paris judgement. At this point the true intentions of the French were revealed. When the dean of Le Puy came to take possession, he brought with him the lieutenant of King Philip’s seneschal of Toulouse. These men seized Roger-Bernard by his clothing and physically threw him out of the castle. The banners of the King of France were then set up over the barbican, signifying that Bigorre was now a fiefdom of the Capets.

The whole thing was a set-up: Edward had been robbed, Roger-Bernard humiliated, and the canons of Le Puy no doubt compensated for their loss with a hefty casket of French gold. Despite this, when war finally broke out in 1294, Roger-Bernard chose to fight for the French. He had to choose one or the other, and the French were a lot closer. They were also prepared to pay through the nose for his services.

Unfortunately for Dodgy Roger, his own chickens now came home to roost. He had build up his power by forced marriages, alliances and sheer brute force, bullying the lesser lords of Béarn into becoming his vassals. These nobles now took their revenge by serving Edward against the French, and the majority of the Béarnais gentry would remain loyal to the Plantagenets throughout the Hundred Years War.

Philip IV’s intentions towards Gascony were becoming clear as early as 1284. In that year his lawyers challenged Edward I’s right to hold Bigorre free of subjection to the French crown. The English king was technically in the right, since the bishop and chapter of Le Puy in Velay had sold their rights to homage in Bigorre to Henry III in 1253.

The French king’s lawyers thought otherwise. After much nodding and frowning and pursing of lips, the Paris parlement gave Bigorre back to Le Puy. This was in the teeth of Edward’s protests and those of Count Roger-Bernard, who claimed to be acting on behalf of his sister-in-law Constance, daughter of Gaston of Béarn.

(Yes I know this is complicated. Keep up at the back)

Roger-Bernard decided to make a stand and occupied the castle of Vic-de-Bigorre, in defiance of the Paris judgement. At this point the true intentions of the French were revealed. When the dean of Le Puy came to take possession, he brought with him the lieutenant of King Philip’s seneschal of Toulouse. These men seized Roger-Bernard by his clothing and physically threw him out of the castle. The banners of the King of France were then set up over the barbican, signifying that Bigorre was now a fiefdom of the Capets.

The whole thing was a set-up: Edward had been robbed, Roger-Bernard humiliated, and the canons of Le Puy no doubt compensated for their loss with a hefty casket of French gold. Despite this, when war finally broke out in 1294, Roger-Bernard chose to fight for the French. He had to choose one or the other, and the French were a lot closer. They were also prepared to pay through the nose for his services.

Unfortunately for Dodgy Roger, his own chickens now came home to roost. He had build up his power by forced marriages, alliances and sheer brute force, bullying the lesser lords of Béarn into becoming his vassals. These nobles now took their revenge by serving Edward against the French, and the majority of the Béarnais gentry would remain loyal to the Plantagenets throughout the Hundred Years War.

Published on October 09, 2019 02:56

October 8, 2019

Foix the fox (2)

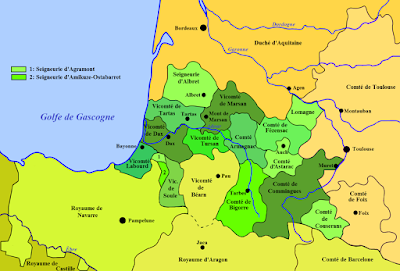

Shortly before his death in 1290, Gaston de Béarn’s final act of spite was to deny his eldest daughter, Mathe, her inheritance. Instead he left Béarn to his younger daughter, Marguerite, and her husband Count Roger-Bernard of Foix. The lordships of Foix-Bearn thus became a single unit.

Mathe’s husband was Géraud V, Count of Armagnac. Gaston chose to pass them over because Géraud and his wife had not assisted him against his enemies. This rejection caused a long-running conflict between the houses of Foix and Armagnac, one of the great dynastic feuds of the medieval era. Philippe de Mézieres, a fourteenth century French soldier and poet, compared it to the Anglo-French wars, the Guelf-Ghibelline conflict, and the rivalry between Castile and Portugal. It might also be compared to the feud between Percy and Neville in northern England.

At first the rival counts decided to settle the affair by invoking the Southern custom of ‘gages de bataille’ or single combat. Both men were vassals of the kings of England and France, but Edward I made a habit of refusing to allow duels in his realm. Philip IV was more accommodating. In 1293 Géraud asserted in Philip’s presence that his rival had falsified Gaston’s last will and testament, and a judicial duel was set to take place before the king at Gisors.

What followed was very similar to the later abortive duel between Henry of Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray in England. Before the fight began, Philip threw down his gage as a sign that he would not allow it to continue. This was a bit of good luck for Armagnac, who had already managed to fall off his horse.

Philip hoped to settle the succession crisis by judicial rather than violent means. He failed to prevent the quarrel blowing up into full-scale private war, but then enjoyed his own slice of good fortune when war erupted between France and England in 1294. There was, of course, nothing fortunate about it: the war was engineered from the start by Philip and his councillors. The Foix-Armagnac feud was put on hold while the conflict lasted, and Count Roger-Bernard accepted a massive bribe to desert Edward and join Philip.

Mathe’s husband was Géraud V, Count of Armagnac. Gaston chose to pass them over because Géraud and his wife had not assisted him against his enemies. This rejection caused a long-running conflict between the houses of Foix and Armagnac, one of the great dynastic feuds of the medieval era. Philippe de Mézieres, a fourteenth century French soldier and poet, compared it to the Anglo-French wars, the Guelf-Ghibelline conflict, and the rivalry between Castile and Portugal. It might also be compared to the feud between Percy and Neville in northern England.

At first the rival counts decided to settle the affair by invoking the Southern custom of ‘gages de bataille’ or single combat. Both men were vassals of the kings of England and France, but Edward I made a habit of refusing to allow duels in his realm. Philip IV was more accommodating. In 1293 Géraud asserted in Philip’s presence that his rival had falsified Gaston’s last will and testament, and a judicial duel was set to take place before the king at Gisors.

What followed was very similar to the later abortive duel between Henry of Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray in England. Before the fight began, Philip threw down his gage as a sign that he would not allow it to continue. This was a bit of good luck for Armagnac, who had already managed to fall off his horse.

Philip hoped to settle the succession crisis by judicial rather than violent means. He failed to prevent the quarrel blowing up into full-scale private war, but then enjoyed his own slice of good fortune when war erupted between France and England in 1294. There was, of course, nothing fortunate about it: the war was engineered from the start by Philip and his councillors. The Foix-Armagnac feud was put on hold while the conflict lasted, and Count Roger-Bernard accepted a massive bribe to desert Edward and join Philip.

Published on October 08, 2019 05:24

October 7, 2019

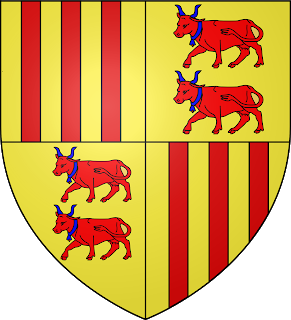

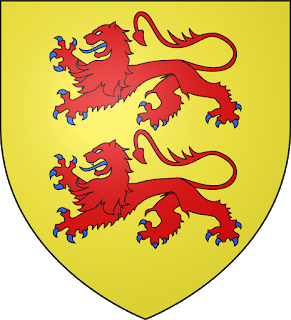

Foix the fox (1)

In 1289 Gaston VII, Vicomte of Béarn in southern Gascony, was made an offer he couldn’t refuse. He was a titled brigand who had spent the past forty years playing off his feudal overlords against each other; Gaston’s standard tactic was to go into revolt against his direct overlord, the King of England, and then run squealing for help to his indirect overlord, the King of France. He used the ensuing chaos to run riot and burn and pillage at will: in 1274 it was estimated that he had caused 100,000 livres tournois worth of damage during his ‘cavalgade’ and plundering raids.

He finally overplayed his hand by arranging a marriage between his daughter Margaret to Roger-Bernard III, count of Foix in southwest France. Gaston had no son, so his inheritance would fall to his son-in-law. The marriage was sanctioned by Edward I, but neither the English king or his cousin, Philip III of France, were overjoyed at the prospect between Foix and Béarn. This created a power bloc on the edge of the Pyrenees that threatened the local hegemony of both kingdoms.

The kings decided to get rid of Gaston before he came up with any more bright ideas. As part of their plans for a joint crusade, Gaston was obliged to agree to go with them to the Holy Land. He had backed out of Edward’s previous crusade in 1270, but this time there was no escape clause. The agreement stipulated that Edward would confiscate Gaston’s lands for debts owed to the English crown, while all of his castles would either be destroyed or taken into the king’s hands. He would, in effect, be disinherited and exiled.

This was precisely the same ‘offer’ made to Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd in November 1282. Dafydd had refused, but Gaston had no choice: if he said no, Edward and Philip would crush him like a bug. He took the cross in 1290 and - as if to cheat his enemies - promptly died a few days later, leaving five knights of Béarn to redeem his vow.

Enter Foix the fox alias Count Roger-Bernard III. This guy was a player and a half.

He finally overplayed his hand by arranging a marriage between his daughter Margaret to Roger-Bernard III, count of Foix in southwest France. Gaston had no son, so his inheritance would fall to his son-in-law. The marriage was sanctioned by Edward I, but neither the English king or his cousin, Philip III of France, were overjoyed at the prospect between Foix and Béarn. This created a power bloc on the edge of the Pyrenees that threatened the local hegemony of both kingdoms.

The kings decided to get rid of Gaston before he came up with any more bright ideas. As part of their plans for a joint crusade, Gaston was obliged to agree to go with them to the Holy Land. He had backed out of Edward’s previous crusade in 1270, but this time there was no escape clause. The agreement stipulated that Edward would confiscate Gaston’s lands for debts owed to the English crown, while all of his castles would either be destroyed or taken into the king’s hands. He would, in effect, be disinherited and exiled.

This was precisely the same ‘offer’ made to Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd in November 1282. Dafydd had refused, but Gaston had no choice: if he said no, Edward and Philip would crush him like a bug. He took the cross in 1290 and - as if to cheat his enemies - promptly died a few days later, leaving five knights of Béarn to redeem his vow.

Enter Foix the fox alias Count Roger-Bernard III. This guy was a player and a half.

Published on October 07, 2019 01:54