David Pilling's Blog, page 49

August 25, 2019

Powys and FitzEmpress (4)

n 1165 Henry II gathered a massive army from all across his empire to invade Wales. His aim, according to the Welsh chronicles, was to ‘annihilate all Welshmen’.

This splendid bit of hyperbole has obscured the king’s actual strategic aims. He chose to enter Wales via the Ceiriog valley and the Berwyn mountains, only to come unstuck when the heavens opened as his army marched across the high crests of the Berwyns. The foul weather forced him to call off the campaign and retreat into Shropshire.

In the context of Henry’s relationship with the Powysians, his strategy becomes clear. The king had spent the past decade paying lavish subsidies to the princes of Powys, but in 1165 many of them chose to join Owain Gwynedd: Truly after that all the Welsh of North Wales, South Wales and Powys unanimously threw off the French yoke (Annales Cambriae). Not all the Powysians deserted Henry. Payments in the Pipe Roll accounts show that Owain Brogyntyn, one of the many sons of Madog ap Maredudd, continued to take the king’s money. Two other ‘sons of Madog’, possibly twins, were in receipt of 40 shillings. The ‘French yoke’ consisted of a steady flow of English cash, and not everyone was prepared to abandon the gravy train. Roger of Powys, a Welsh castellan, served in Henry’s retinue. The most important of those who joined the Venedotian alliance were Owain Cyfeiliog and Iorwerth Goch, explicitly named in the Brut.

Thus it appears that Henry’s intention was to drive a wedge between Owain Gwynedd and his allies in northern Powys, followed by an invasion of Gwynedd. The king may have also hoped that his massive show of force would draw the Powysians back to his side. If so, then the campaign was more successful than Welsh chroniclers were prepared to admit. The Pipe Roll for 1165 shows that Owain Cyfeiliog and Iorwerth Goch were back on Henry’s payroll a few months after the war ended. The king’s justiciar paid out 100 shillings for messages carried between Owain and the king, while Iorwerth Goch was paid for bringing horses to the English court for Henry’s own use. Owain and Iorwerth may have required little persuasion.

The show of determined unity reported in the chronicles does not reflect the history, which was one of bitter hatred. In the years leading up to 1165 Owain Gwynedd had butchered a Powysian army at Coleshill, murdered the heir to the Powysian throne and repeatedly invaded and ravaged Powysian territory.

This splendid bit of hyperbole has obscured the king’s actual strategic aims. He chose to enter Wales via the Ceiriog valley and the Berwyn mountains, only to come unstuck when the heavens opened as his army marched across the high crests of the Berwyns. The foul weather forced him to call off the campaign and retreat into Shropshire.

In the context of Henry’s relationship with the Powysians, his strategy becomes clear. The king had spent the past decade paying lavish subsidies to the princes of Powys, but in 1165 many of them chose to join Owain Gwynedd: Truly after that all the Welsh of North Wales, South Wales and Powys unanimously threw off the French yoke (Annales Cambriae). Not all the Powysians deserted Henry. Payments in the Pipe Roll accounts show that Owain Brogyntyn, one of the many sons of Madog ap Maredudd, continued to take the king’s money. Two other ‘sons of Madog’, possibly twins, were in receipt of 40 shillings. The ‘French yoke’ consisted of a steady flow of English cash, and not everyone was prepared to abandon the gravy train. Roger of Powys, a Welsh castellan, served in Henry’s retinue. The most important of those who joined the Venedotian alliance were Owain Cyfeiliog and Iorwerth Goch, explicitly named in the Brut.

Thus it appears that Henry’s intention was to drive a wedge between Owain Gwynedd and his allies in northern Powys, followed by an invasion of Gwynedd. The king may have also hoped that his massive show of force would draw the Powysians back to his side. If so, then the campaign was more successful than Welsh chroniclers were prepared to admit. The Pipe Roll for 1165 shows that Owain Cyfeiliog and Iorwerth Goch were back on Henry’s payroll a few months after the war ended. The king’s justiciar paid out 100 shillings for messages carried between Owain and the king, while Iorwerth Goch was paid for bringing horses to the English court for Henry’s own use. Owain and Iorwerth may have required little persuasion.

The show of determined unity reported in the chronicles does not reflect the history, which was one of bitter hatred. In the years leading up to 1165 Owain Gwynedd had butchered a Powysian army at Coleshill, murdered the heir to the Powysian throne and repeatedly invaded and ravaged Powysian territory.

Published on August 25, 2019 09:55

August 24, 2019

Powys and FitzEmpress (3)

In 1160 Madog ap Maredudd died at Whittingdon Castle in Shropshire. The poet Cynddylan records how Powysian forces, the teulu of Madog and his son Llywelyn, had been called to Cynwyd Gadfor in Edeirnion in January to give advice on a crisis that was brewing.

Whittingdon was one of a group of castles held for the king, which also included Overton and Chirk. All three were held by Welsh castellans of considerable reputation: the brothers Roger and Jonas de Powis and Madog’s own brother Iorwerth Goch.

Madog’s death at Whittingdon was followed immediately by that of his son, Llywelyn. He had many sons, but it seems Llywelyn was regarded as the best of them: the shield of Powys, the one man who could keep the kingdom intact after Madog was gone.

The Brut says this of him:

Y gwr a oed unic obeith y holl wyr Powys (The only hope for all the men of Powys)

Cynddelw wrote: Marw Madawg, mawr ei eilyw/Lladd Llywelyn, llwyr ddilyw! (The death of Madog, a cause for grief/the death of Llywelyn, utter catastrophe!)

Another poet, Gwalchmai, hints at foul play:

Gwelais frad a chad a chamawn Cyfrwng llew a llyw Merfyniawn (I saw treachery and strife between a lion [warrior] and the leader of the descendants of Merfyn [the dynasty of Gwynedd]

Gwalchmai’s precise meaning is unclear, but he implies Llywelyn died at the hands of the rival dynasty of Gwynedd. Immediately after his death, the forces of Owain Gwynedd invaded Edeirnion. Cynddelw laments that if Llywelyn was still alive, the Venedotians would not have set foot on Powysian territory. As it was, the Powysians turned to the bank of Henry again. Entries in the Pipe Roll for Michaelmas 1160 show royal payments to Roger de Powis for the garrison at Edeirnion, implying he had regained control of the sector.

Whittingdon CastleThere is something deeply sinister about the way Madog and Llywelyn were lured into Edeirnion to give ‘advice’, and then done to death. Over a century later Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Owain Gwynedd’s descendant, would be lured onto enemy territory and killed in the same way. Among those he found waiting for him was Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, a descendant of Llywelyn ap Madog’s cousin, Owain Cyfeiliog. What goes round comes round.

Whittingdon CastleThere is something deeply sinister about the way Madog and Llywelyn were lured into Edeirnion to give ‘advice’, and then done to death. Over a century later Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Owain Gwynedd’s descendant, would be lured onto enemy territory and killed in the same way. Among those he found waiting for him was Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, a descendant of Llywelyn ap Madog’s cousin, Owain Cyfeiliog. What goes round comes round.

Whittingdon was one of a group of castles held for the king, which also included Overton and Chirk. All three were held by Welsh castellans of considerable reputation: the brothers Roger and Jonas de Powis and Madog’s own brother Iorwerth Goch.

Madog’s death at Whittingdon was followed immediately by that of his son, Llywelyn. He had many sons, but it seems Llywelyn was regarded as the best of them: the shield of Powys, the one man who could keep the kingdom intact after Madog was gone.

The Brut says this of him:

Y gwr a oed unic obeith y holl wyr Powys (The only hope for all the men of Powys)

Cynddelw wrote: Marw Madawg, mawr ei eilyw/Lladd Llywelyn, llwyr ddilyw! (The death of Madog, a cause for grief/the death of Llywelyn, utter catastrophe!)

Another poet, Gwalchmai, hints at foul play:

Gwelais frad a chad a chamawn Cyfrwng llew a llyw Merfyniawn (I saw treachery and strife between a lion [warrior] and the leader of the descendants of Merfyn [the dynasty of Gwynedd]

Gwalchmai’s precise meaning is unclear, but he implies Llywelyn died at the hands of the rival dynasty of Gwynedd. Immediately after his death, the forces of Owain Gwynedd invaded Edeirnion. Cynddelw laments that if Llywelyn was still alive, the Venedotians would not have set foot on Powysian territory. As it was, the Powysians turned to the bank of Henry again. Entries in the Pipe Roll for Michaelmas 1160 show royal payments to Roger de Powis for the garrison at Edeirnion, implying he had regained control of the sector.

Whittingdon CastleThere is something deeply sinister about the way Madog and Llywelyn were lured into Edeirnion to give ‘advice’, and then done to death. Over a century later Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Owain Gwynedd’s descendant, would be lured onto enemy territory and killed in the same way. Among those he found waiting for him was Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, a descendant of Llywelyn ap Madog’s cousin, Owain Cyfeiliog. What goes round comes round.

Whittingdon CastleThere is something deeply sinister about the way Madog and Llywelyn were lured into Edeirnion to give ‘advice’, and then done to death. Over a century later Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Owain Gwynedd’s descendant, would be lured onto enemy territory and killed in the same way. Among those he found waiting for him was Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, a descendant of Llywelyn ap Madog’s cousin, Owain Cyfeiliog. What goes round comes round.

Published on August 24, 2019 01:46

August 23, 2019

Powys and FitzEmpress (2)

In the years that followed the campaign of 1157, Henry II continued to show favour to the lineage of Madog ap Maredudd, lord of Powys. In 1158, while Madog was in receipt of English subsidies, the king staged a grand ceremony at Worcester. Here he knighted one of Madog’s sons, as well as the King of the Isles of western Scotland. In the same year Henry forced the submission of Rhys ap Gruffudd of Deheubarth, who was obliged to abandon Ceredigion and Cantref Bychan. Henry’s policy was to create a new order in Wales; an extended Anglo-Norman presence in Deheubarth and friendly relations with Powys and its dependencies.

Madog himself wanted to be friends with everyone. As well as accepting Henry’s overtures, he married one of his daughters to King Cadwallon of Maelienydd, another to Owain Gwynedd’s son Iorwerth, and his son to Owain’s daughter Angharad. He also arranged the marriage of yet another daughter to Rhys ap Gruffudd.

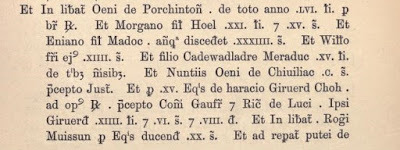

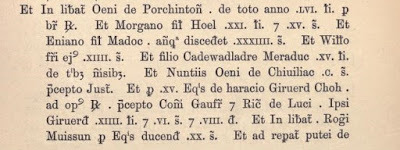

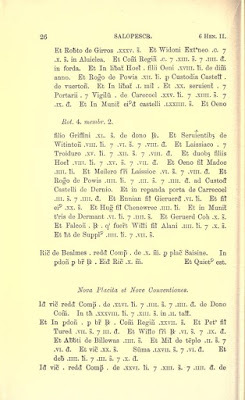

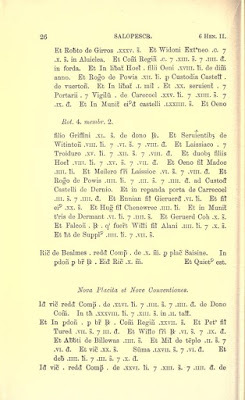

This shrewd man used his relatives in other ways to secure Henry’s friendship. His brother, Iorwerth Goch, was employed as a supplier of horses to the English court, and as a very well-paid castellan of Chirk. He would found a dynasty in Shropshire as well as extensive territories in eastern Powys. One of Madog’s sons, Gruffudd, was subsidised by the king to hold northern Powys against Gwynedd. Another, Owain, also received English subsidies and was later confirmed by royal charter in his lands of Mechain and western Oswestry. The most impressively rewarded of Madog’s sons was Owain of Porkington, who received a constant flow of English cash throughout the 1160s. Finally Madog’s nephew, Owain Cyfeiliog, was noted by Gerald of Wales as being on especially friendly terms with King Henry.

This shrewd man used his relatives in other ways to secure Henry’s friendship. His brother, Iorwerth Goch, was employed as a supplier of horses to the English court, and as a very well-paid castellan of Chirk. He would found a dynasty in Shropshire as well as extensive territories in eastern Powys. One of Madog’s sons, Gruffudd, was subsidised by the king to hold northern Powys against Gwynedd. Another, Owain, also received English subsidies and was later confirmed by royal charter in his lands of Mechain and western Oswestry. The most impressively rewarded of Madog’s sons was Owain of Porkington, who received a constant flow of English cash throughout the 1160s. Finally Madog’s nephew, Owain Cyfeiliog, was noted by Gerald of Wales as being on especially friendly terms with King Henry.

The poet Cynddelw praised Madog as ysgwyd pedeiriaith, which roughly translated as ‘shield/protector of four peoples/cultures/languages’. He and his family had asserted their lordship over Welsh, Anglo-Normans and English, and - via domination of local clergy - those who used Latin. Madog was also celebrated in the opening lines of The Dream of Rhonawby:

‘Madog ap Maredudd ruled Powys from end to end, that is from Porfordd [Pulford near Chester], to Gwanan in the furthest uplands of Arwystli’.

Now this guy was a player.

Madog himself wanted to be friends with everyone. As well as accepting Henry’s overtures, he married one of his daughters to King Cadwallon of Maelienydd, another to Owain Gwynedd’s son Iorwerth, and his son to Owain’s daughter Angharad. He also arranged the marriage of yet another daughter to Rhys ap Gruffudd.

This shrewd man used his relatives in other ways to secure Henry’s friendship. His brother, Iorwerth Goch, was employed as a supplier of horses to the English court, and as a very well-paid castellan of Chirk. He would found a dynasty in Shropshire as well as extensive territories in eastern Powys. One of Madog’s sons, Gruffudd, was subsidised by the king to hold northern Powys against Gwynedd. Another, Owain, also received English subsidies and was later confirmed by royal charter in his lands of Mechain and western Oswestry. The most impressively rewarded of Madog’s sons was Owain of Porkington, who received a constant flow of English cash throughout the 1160s. Finally Madog’s nephew, Owain Cyfeiliog, was noted by Gerald of Wales as being on especially friendly terms with King Henry.

This shrewd man used his relatives in other ways to secure Henry’s friendship. His brother, Iorwerth Goch, was employed as a supplier of horses to the English court, and as a very well-paid castellan of Chirk. He would found a dynasty in Shropshire as well as extensive territories in eastern Powys. One of Madog’s sons, Gruffudd, was subsidised by the king to hold northern Powys against Gwynedd. Another, Owain, also received English subsidies and was later confirmed by royal charter in his lands of Mechain and western Oswestry. The most impressively rewarded of Madog’s sons was Owain of Porkington, who received a constant flow of English cash throughout the 1160s. Finally Madog’s nephew, Owain Cyfeiliog, was noted by Gerald of Wales as being on especially friendly terms with King Henry.

The poet Cynddelw praised Madog as ysgwyd pedeiriaith, which roughly translated as ‘shield/protector of four peoples/cultures/languages’. He and his family had asserted their lordship over Welsh, Anglo-Normans and English, and - via domination of local clergy - those who used Latin. Madog was also celebrated in the opening lines of The Dream of Rhonawby:

‘Madog ap Maredudd ruled Powys from end to end, that is from Porfordd [Pulford near Chester], to Gwanan in the furthest uplands of Arwystli’.

Now this guy was a player.

Published on August 23, 2019 05:19

Powys and FitzEmpress (1)

In 1157, after the conclusion of Henry II’s campaign in North Wales, his Powysian allies continued to fight against Owain Gwynedd. After Henry and Owain had made peace, the Brut records that Iorwerth Goch destroyed the castle Owain had constructed in Iâl:

Then Iorwerth the Red, son of Maredudd, returned to the castle of Yale, and burned it.

Iorwerth was the brother of Madog ap Maredudd, lord of Powys, who had fought with Henry against Owain. The attack on Iâl, after the king had gone home, shows the Powysians had their own interests to pursue and were not mere royal auxiliaries.

Even so, Henry was happy to subsidise their war against Owain. Some interesting evidence is provided in a poem composed by Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr, perhaps the greatest Welsh bard of the era, who served all the major princely houses of Gwynedd, Powys and Deheubarth. In about 1187 he composed a work praising the deeds of Owain Cyfeiliog, a prince of southern Powys. The crucial lines are:

Gwaed ar wallt rhag

Allt Cadwallawn

Yn Llanerch, yn lleudir Merfyniawn

Yn llew glew, yn llyw rhag Lleisiawn

(Hair stained with blood before Allt Cadwallon In Llanerch, in the open land of the Merfynion [the descendants of Merfyn, the dynasty of Gwynedd]

A valiant lion, a leader before the Lleision [descendants of Lles, the dynasty of Powys]

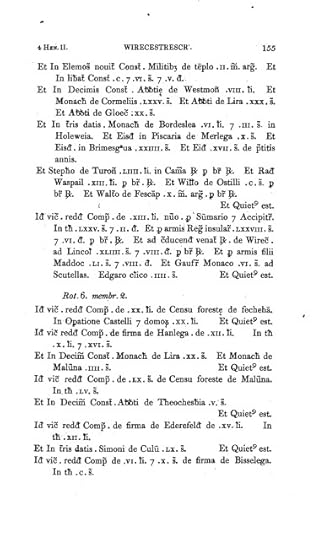

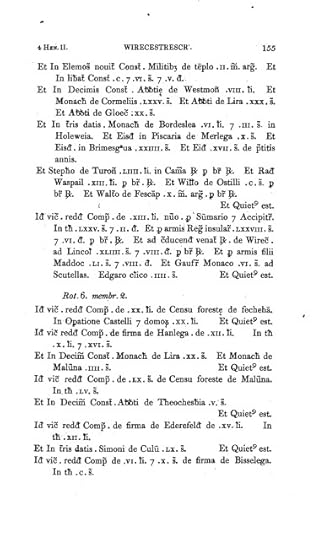

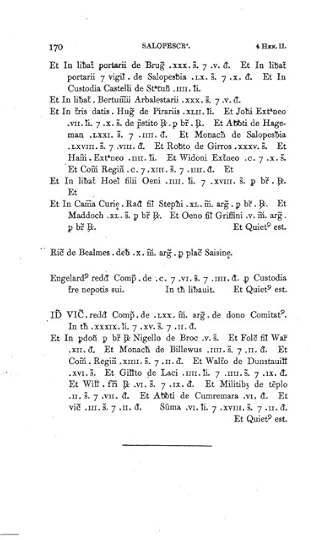

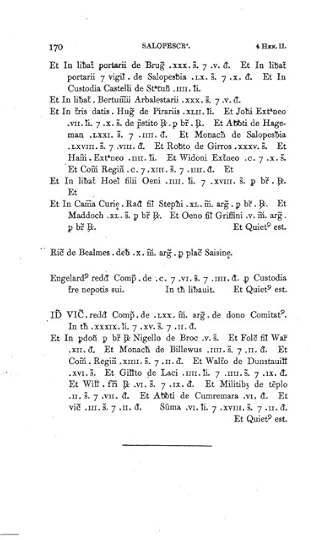

Cynddelw refers to a battle in Gwynedd, and Llanerch has been plausibly identified as the commote of that name in Dyffryn Clwyd. Cynddelw provides no date, but the Pipe Roll for 4 Henry II (1158) records two payments to Owain Cyfeiliog and Madog ap Maredudd. Owain was paid five marks or £3 3s 8d, while Madog received the much smaller sum of 40 shillings.

Thus it appears Owain had done some great service for Henry, and both he and Madog continued to receive English royal subsidies in 1157-8. A successful raid into Gwynedd, coming at the tail-end of the royal campaign, would make sense. While Owain Cyfeiliog kept the Venedotians busy in their homeland, Madog and Iorwerth Goch drove Owain’s men from Powys. Thus the chronicle, poetry and account evidence are in persuasive symmetry.

Thus it appears Owain had done some great service for Henry, and both he and Madog continued to receive English royal subsidies in 1157-8. A successful raid into Gwynedd, coming at the tail-end of the royal campaign, would make sense. While Owain Cyfeiliog kept the Venedotians busy in their homeland, Madog and Iorwerth Goch drove Owain’s men from Powys. Thus the chronicle, poetry and account evidence are in persuasive symmetry.

Then Iorwerth the Red, son of Maredudd, returned to the castle of Yale, and burned it.

Iorwerth was the brother of Madog ap Maredudd, lord of Powys, who had fought with Henry against Owain. The attack on Iâl, after the king had gone home, shows the Powysians had their own interests to pursue and were not mere royal auxiliaries.

Even so, Henry was happy to subsidise their war against Owain. Some interesting evidence is provided in a poem composed by Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr, perhaps the greatest Welsh bard of the era, who served all the major princely houses of Gwynedd, Powys and Deheubarth. In about 1187 he composed a work praising the deeds of Owain Cyfeiliog, a prince of southern Powys. The crucial lines are:

Gwaed ar wallt rhag

Allt Cadwallawn

Yn Llanerch, yn lleudir Merfyniawn

Yn llew glew, yn llyw rhag Lleisiawn

(Hair stained with blood before Allt Cadwallon In Llanerch, in the open land of the Merfynion [the descendants of Merfyn, the dynasty of Gwynedd]

A valiant lion, a leader before the Lleision [descendants of Lles, the dynasty of Powys]

Cynddelw refers to a battle in Gwynedd, and Llanerch has been plausibly identified as the commote of that name in Dyffryn Clwyd. Cynddelw provides no date, but the Pipe Roll for 4 Henry II (1158) records two payments to Owain Cyfeiliog and Madog ap Maredudd. Owain was paid five marks or £3 3s 8d, while Madog received the much smaller sum of 40 shillings.

Thus it appears Owain had done some great service for Henry, and both he and Madog continued to receive English royal subsidies in 1157-8. A successful raid into Gwynedd, coming at the tail-end of the royal campaign, would make sense. While Owain Cyfeiliog kept the Venedotians busy in their homeland, Madog and Iorwerth Goch drove Owain’s men from Powys. Thus the chronicle, poetry and account evidence are in persuasive symmetry.

Thus it appears Owain had done some great service for Henry, and both he and Madog continued to receive English royal subsidies in 1157-8. A successful raid into Gwynedd, coming at the tail-end of the royal campaign, would make sense. While Owain Cyfeiliog kept the Venedotians busy in their homeland, Madog and Iorwerth Goch drove Owain’s men from Powys. Thus the chronicle, poetry and account evidence are in persuasive symmetry.

Published on August 23, 2019 02:20

August 22, 2019

Origins of conflict

Some shrewd remarks from Dr Malcolm Vale on the early stages of the Hundred Years War:

‘To describe a conflict as ‘futile’ or ‘useless’ may be to place too high a value upon the efficacy of war as a solvent to political problems. Medieval wars were not fought solely for political, economic or material gain. A society which set a high value upon lavish gift-giving and exchange, and upon what later generations have seen as a ‘conspicuous waste’ and conscious dissipation of resources, was unlikely to have much room for more recent notions of political and diplomatic gain. Warfare commenced when diplomacy failed. Diplomacy was conducted in a highly legalistic manner, and the points at issue in this extended lawsuit tended to focus upon rights and status as well as income and revenues. We should not underestimate the defence of honour or the realization of claims to certain titles, rights and privileges as motivating factors leading to the outbreak of open and public war during this period. Warfare was both a demonstration of right and a gesture, symptomatic of more general tendencies within later medieval society. However misguided and deluded we may believe the rulers of this period and their advisors to have been in seeking to resolve conflicts by force of arms, the relative weakness of diplomatic alternatives must always be borne in mind. Princes were conditioned to believe in the justificatory, and even cathartic nature of war as a positive force in human affairs.’

Vale was speaking of the Anglo-French war of 1294-98, but his comments can equally well be applied to later stages of the HYW. There is a recent argument that the war was a complete waste of time from an English view, and a shocking dissipation of manpower and resources. That is to apply some very convenient hindsight, and to judge the conflict via modern perceptions of ‘gain’.

It certainly wasn’t the view of the inhabitants of Gascony, the last major English possession in France. The Gascons went through hell and high water on behalf of the Plantagenets; to suggest they ought to have been abandoned to their fate, simply to avoid ‘waste’, is a rather Anglocentric perspective:

‘The war effort did not collapse and financial stringency apparently had little effect upon the determination of many Gascons to support the Plantagenets to the bitter end. Many of them - the dispossessed and disinherited nobles, had nothing more to lose. England certainly spent large sums of money on Gascony, but many of the duchy’s inhabitants abandoned their lands and possessions, endured imprisonment and underwent exile in return’.

‘To describe a conflict as ‘futile’ or ‘useless’ may be to place too high a value upon the efficacy of war as a solvent to political problems. Medieval wars were not fought solely for political, economic or material gain. A society which set a high value upon lavish gift-giving and exchange, and upon what later generations have seen as a ‘conspicuous waste’ and conscious dissipation of resources, was unlikely to have much room for more recent notions of political and diplomatic gain. Warfare commenced when diplomacy failed. Diplomacy was conducted in a highly legalistic manner, and the points at issue in this extended lawsuit tended to focus upon rights and status as well as income and revenues. We should not underestimate the defence of honour or the realization of claims to certain titles, rights and privileges as motivating factors leading to the outbreak of open and public war during this period. Warfare was both a demonstration of right and a gesture, symptomatic of more general tendencies within later medieval society. However misguided and deluded we may believe the rulers of this period and their advisors to have been in seeking to resolve conflicts by force of arms, the relative weakness of diplomatic alternatives must always be borne in mind. Princes were conditioned to believe in the justificatory, and even cathartic nature of war as a positive force in human affairs.’

Vale was speaking of the Anglo-French war of 1294-98, but his comments can equally well be applied to later stages of the HYW. There is a recent argument that the war was a complete waste of time from an English view, and a shocking dissipation of manpower and resources. That is to apply some very convenient hindsight, and to judge the conflict via modern perceptions of ‘gain’.

It certainly wasn’t the view of the inhabitants of Gascony, the last major English possession in France. The Gascons went through hell and high water on behalf of the Plantagenets; to suggest they ought to have been abandoned to their fate, simply to avoid ‘waste’, is a rather Anglocentric perspective:

‘The war effort did not collapse and financial stringency apparently had little effect upon the determination of many Gascons to support the Plantagenets to the bitter end. Many of them - the dispossessed and disinherited nobles, had nothing more to lose. England certainly spent large sums of money on Gascony, but many of the duchy’s inhabitants abandoned their lands and possessions, endured imprisonment and underwent exile in return’.

Published on August 22, 2019 05:51

August 21, 2019

Church matters

June 25 1284, from the Littere Wallie. This is the advice of John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury, to the king concerning damages suffered by religious houses in Wales during the war of 1282-3.

In November 1282, when Peckham went into Gwynedd to hold talks with Prince Llywelyn, the prince accused English troops of ravaging churches in Wales. Peckham’s response, including among the rambling notes in his register, was thus:

“In addition you strike against the king, saying that the royal churches and church people are cruelly ravaged and killed by tyranny, to which we reply that the lord king was attacked by evils not that he made then, certainly neither has he considered making them; conversely he has voluntarily offered to us, of which I will urge him on when opportune, he intends to repair the churches at his own cost, though he puts this off until he can forever calm this period of warfare, as if he did this earlier they might again be destroyed by brigands.”

John Peckham

John Peckham

Whatever might be said about Peckham and his prejudices against the Welsh and the Jews, he was as good as his word. In June 1284 he reminded King Edward of his obligation, and in October-November payments were issued to repair 107 Welsh churches. They included larger houses such as Valle Crucis (£160) and the Dominicans at Bangor (£100), to small churches at Abergele (6 marks) and Henllan (50 shillings).

There is also an intriguing payment to a certain Gwenhwyfar, widow of Hywel ap Gruffudd, who received 10 marks for damages due to the war. This payment was made at Castell y Bere, so possibly Hywel had died in the fighting in Meirionydd.

In November 1282, when Peckham went into Gwynedd to hold talks with Prince Llywelyn, the prince accused English troops of ravaging churches in Wales. Peckham’s response, including among the rambling notes in his register, was thus:

“In addition you strike against the king, saying that the royal churches and church people are cruelly ravaged and killed by tyranny, to which we reply that the lord king was attacked by evils not that he made then, certainly neither has he considered making them; conversely he has voluntarily offered to us, of which I will urge him on when opportune, he intends to repair the churches at his own cost, though he puts this off until he can forever calm this period of warfare, as if he did this earlier they might again be destroyed by brigands.”

John Peckham

John PeckhamWhatever might be said about Peckham and his prejudices against the Welsh and the Jews, he was as good as his word. In June 1284 he reminded King Edward of his obligation, and in October-November payments were issued to repair 107 Welsh churches. They included larger houses such as Valle Crucis (£160) and the Dominicans at Bangor (£100), to small churches at Abergele (6 marks) and Henllan (50 shillings).

There is also an intriguing payment to a certain Gwenhwyfar, widow of Hywel ap Gruffudd, who received 10 marks for damages due to the war. This payment was made at Castell y Bere, so possibly Hywel had died in the fighting in Meirionydd.

Published on August 21, 2019 08:08

August 20, 2019

Checking the small print

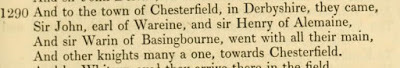

In November 1297 Lord Robert de Scales, a Knight Templar in the English army in Flanders, was paid his wages for service to date:

To lord Robert de Scales, knight, for his wages from the sixth day of October when he first raised his standard before Damme and for his one knight made a knight on the same day and six of his squires, until the eleventh day of November, each of whom are credited for 37 days; with the aforesaid Robert at 4 shillings per day, his knight at 2 shillings per day, and for all the squires 12 pence per day by his own hand.

Robert had 'raised his standard' before the walls of Damme, a port town that controlled direct access to the Channel, on 6 October. This contradicts the chronicle account of the Minorite of Flanders, a Flemish annalist who loathed the English. The Minorite claims the English marched to attack Damme on 10 October.

So what of it? Edward I had signed a truce with his enemy, Philip le Bel, on 9 October. By pushing forward the allied assault on Damme by four days, the Minorite made Edward and the English look like oath-breakers. In reality the attack began on the 6, three days before the truce was signed.

The moral of this lesson hath been: always check the small print, forsooth.

*Thanks to Rich Price for checking my translation.

To lord Robert de Scales, knight, for his wages from the sixth day of October when he first raised his standard before Damme and for his one knight made a knight on the same day and six of his squires, until the eleventh day of November, each of whom are credited for 37 days; with the aforesaid Robert at 4 shillings per day, his knight at 2 shillings per day, and for all the squires 12 pence per day by his own hand.

Robert had 'raised his standard' before the walls of Damme, a port town that controlled direct access to the Channel, on 6 October. This contradicts the chronicle account of the Minorite of Flanders, a Flemish annalist who loathed the English. The Minorite claims the English marched to attack Damme on 10 October.

So what of it? Edward I had signed a truce with his enemy, Philip le Bel, on 9 October. By pushing forward the allied assault on Damme by four days, the Minorite made Edward and the English look like oath-breakers. In reality the attack began on the 6, three days before the truce was signed.

The moral of this lesson hath been: always check the small print, forsooth.

*Thanks to Rich Price for checking my translation.

Published on August 20, 2019 00:53

August 17, 2019

Butchery at Bulskamp

The Battle of Veurne, 20 August 1297 (three days early, but the hell with it).

On 15 June 1297 the French invaded Flanders, six months after Count Guy of Flanders had formally renounced his homage to Philip le Bel. Philip advanced towards Lille and summoned Charles d’Artois to bring the French field army from Gascony to help in the siege. The departure of Charles lifted the pressure on English garrisons in the duchy, but it seems Philip had decided he could not fight a war on two fronts.

There was little to prevent the French invasion. Edward I had spent lavishly on constructing a ‘grand alliance’ of most of the princes of Western Europe, in the hope they would surround the French and attack them from all sides. The plan misfired as some of Edward’s expensive allies went into action at different times, while others failed to move. Only the Count of Bar attempted to halt the invasion of Flanders, and might have succeeded if the King of Germany, Adolf of Nassau, had responded to Edward’s request to move up in support. Adolf contented himself with sending a paltry sum of six hundred livres to help the war effort.

Outnumbered, Count Guy was forced onto the defensive. He had managed to hire some German mercenaries, and was also supported by two of the German princes on Edward’s payroll, the Count of Katzenelenbogen (try saying that quickly) and Waleran of Valkenburg. Waleran had previously distinguished himself at the Siege of Vendôme, where he picked up the Duke of Vendôme and threw him into a canal, where he drowned.

A number of skirmishes were fought on the outskirts of Lille, and on 16 June a Flemish-German force was defeated by the French at the bridge of Commines. Meanwhile Edward was frantically trying to scrape together an army in England. After years of war and taxation, the English were fed up and had no interest in a campaign in Flanders. When Edward summoned the men of three English counties to muster at Winchelsea on 28 June, only a certain Miles Pichard turned up, and he was a household knight. In desperation, Edward was forced to turn to recruitment in Wales.

Four days after Commines, there was a much larger engagement at Veurne; also called the Battle of Bulskamp, since it was fought on the plain of Bulskamp south of Veurne. It appears the outcome was decided by treachery. As soon as the armies were engaged, the Viscount of Veurne and the Sire de Ghistelles defected to the French.

Upon seeing this, Jean de Gavre turned to the allied commander, William of Julich, and advised him to flee:

“Dear friend, we will all be torn to pieces here; those men betrayed us, we’d better retreat and avoid a disaster.”

To which William responded: “I will never flee! None shall ever say I escaped out of fear! It would be a shame for me and my race. I like fighting better.”

Having put his personal honour before the safety of the army, William led the charge. A straight fight raged on the plain of Bulskamp, with both sides suffering heavy casualties. At last the allies were forced to flee, after five Flemish nobles were killed and eighteen knights and squires taken prisoner. Among the dead were Jean de Gavre and the valiant but misguided William of Julich. The survivors burnt Veurne and then retreated to Lille. Three days later, Edward set sail from Winchelsea with five thousand Welsh archers.

On 15 June 1297 the French invaded Flanders, six months after Count Guy of Flanders had formally renounced his homage to Philip le Bel. Philip advanced towards Lille and summoned Charles d’Artois to bring the French field army from Gascony to help in the siege. The departure of Charles lifted the pressure on English garrisons in the duchy, but it seems Philip had decided he could not fight a war on two fronts.

There was little to prevent the French invasion. Edward I had spent lavishly on constructing a ‘grand alliance’ of most of the princes of Western Europe, in the hope they would surround the French and attack them from all sides. The plan misfired as some of Edward’s expensive allies went into action at different times, while others failed to move. Only the Count of Bar attempted to halt the invasion of Flanders, and might have succeeded if the King of Germany, Adolf of Nassau, had responded to Edward’s request to move up in support. Adolf contented himself with sending a paltry sum of six hundred livres to help the war effort.

Outnumbered, Count Guy was forced onto the defensive. He had managed to hire some German mercenaries, and was also supported by two of the German princes on Edward’s payroll, the Count of Katzenelenbogen (try saying that quickly) and Waleran of Valkenburg. Waleran had previously distinguished himself at the Siege of Vendôme, where he picked up the Duke of Vendôme and threw him into a canal, where he drowned.

A number of skirmishes were fought on the outskirts of Lille, and on 16 June a Flemish-German force was defeated by the French at the bridge of Commines. Meanwhile Edward was frantically trying to scrape together an army in England. After years of war and taxation, the English were fed up and had no interest in a campaign in Flanders. When Edward summoned the men of three English counties to muster at Winchelsea on 28 June, only a certain Miles Pichard turned up, and he was a household knight. In desperation, Edward was forced to turn to recruitment in Wales.

Four days after Commines, there was a much larger engagement at Veurne; also called the Battle of Bulskamp, since it was fought on the plain of Bulskamp south of Veurne. It appears the outcome was decided by treachery. As soon as the armies were engaged, the Viscount of Veurne and the Sire de Ghistelles defected to the French.

Upon seeing this, Jean de Gavre turned to the allied commander, William of Julich, and advised him to flee:

“Dear friend, we will all be torn to pieces here; those men betrayed us, we’d better retreat and avoid a disaster.”

To which William responded: “I will never flee! None shall ever say I escaped out of fear! It would be a shame for me and my race. I like fighting better.”

Having put his personal honour before the safety of the army, William led the charge. A straight fight raged on the plain of Bulskamp, with both sides suffering heavy casualties. At last the allies were forced to flee, after five Flemish nobles were killed and eighteen knights and squires taken prisoner. Among the dead were Jean de Gavre and the valiant but misguided William of Julich. The survivors burnt Veurne and then retreated to Lille. Three days later, Edward set sail from Winchelsea with five thousand Welsh archers.

Published on August 17, 2019 01:50

August 16, 2019

The big stick of Earl Warenne

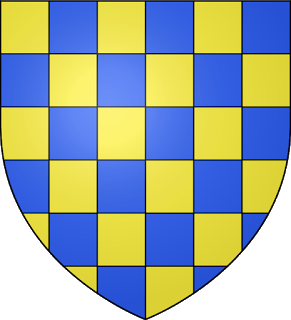

The big stick of Earl Warenne. John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey (1231-1304) is chiefly remembered for his defeat at Stirling Bridge in 1297. His personal performance on the day was catastrophic: he overslept, dithered, listened to bad advice, ignored good advice, and finally ran away very fast. His final humiliation came in Braveheart, when Warenne was deprived of his own defeat and left out of the film in favour of an entirely fictional ‘Lord Bottoms’.

Does one bad day mean Warenne was a blithering incompetent? Far from it. His military career got off to a poor start in 1264, when he and William de Valence ran like hares from the royalist defeat at Lewes. Lewes, however, was a day of shame and disaster for everyone on the royalist side, Edward included. Warenne and Valence got away safely to France and returned the following year. Like Henry Tudor in 1485, they landed on the coast of Pembrokeshire with a small band of soldiers and marched east, to link up with Edward before the battle of Evesham.

After the battle, Warenne was used as a ‘big stick’ against surviving pockets of rebels. He was given military command to crush resistance at Bury St Edmunds in 1266, and fought at Chesterfield in May of the same year. He was also present at the capture of Dover Castle, and consulted by Edward over defence operations on the Isle of Wight. Warenne was clearly trusted in military affairs, though he blotted his copy book a wee bit by committing murder in Henry III’s presence at Westminster.

The earl was no less trusted in Wales. He doesn’t appear to have served in 1277, but in 1282 was given independent command and advanced up the River Dee to capture Castell Dinas Bran. In 1287 he served at the siege of Dryslwyn, and in 1293-4 led part of the royal army in North Wales. In 1296 he routed the Scottish feudal host at Dunbar, apparently after luring them into a fatal charge by means of a feigned retreat.

By the time of Stirling Bridge, Warenne was a veteran of over thirty years of largely successful warfare. Despite his ghastly defeat at the hands of Moray and Wallace, the earl was not disgraced or stripped of command. Edward put him in charge of counter-operations, and in the following months Warenne recaptured Berwick and led the fourth battalion at Falkirk. Despite claiming he was too old and ill, he continued to serve in Scotland: in August 1300, at the River Cree, he rode beside King Edward in a massed cavalry charge that swept the army of Buchan, Comyn of Badenoch and d’Umfraville from the field.

By the time of Stirling Bridge, Warenne was a veteran of over thirty years of largely successful warfare. Despite his ghastly defeat at the hands of Moray and Wallace, the earl was not disgraced or stripped of command. Edward put him in charge of counter-operations, and in the following months Warenne recaptured Berwick and led the fourth battalion at Falkirk. Despite claiming he was too old and ill, he continued to serve in Scotland: in August 1300, at the River Cree, he rode beside King Edward in a massed cavalry charge that swept the army of Buchan, Comyn of Badenoch and d’Umfraville from the field.

John de Warenne, then. Not a very nice man, probably, and will always be remembered for Stirling Bridge. But he deserves better than Lord Bottoms.

Does one bad day mean Warenne was a blithering incompetent? Far from it. His military career got off to a poor start in 1264, when he and William de Valence ran like hares from the royalist defeat at Lewes. Lewes, however, was a day of shame and disaster for everyone on the royalist side, Edward included. Warenne and Valence got away safely to France and returned the following year. Like Henry Tudor in 1485, they landed on the coast of Pembrokeshire with a small band of soldiers and marched east, to link up with Edward before the battle of Evesham.

After the battle, Warenne was used as a ‘big stick’ against surviving pockets of rebels. He was given military command to crush resistance at Bury St Edmunds in 1266, and fought at Chesterfield in May of the same year. He was also present at the capture of Dover Castle, and consulted by Edward over defence operations on the Isle of Wight. Warenne was clearly trusted in military affairs, though he blotted his copy book a wee bit by committing murder in Henry III’s presence at Westminster.

The earl was no less trusted in Wales. He doesn’t appear to have served in 1277, but in 1282 was given independent command and advanced up the River Dee to capture Castell Dinas Bran. In 1287 he served at the siege of Dryslwyn, and in 1293-4 led part of the royal army in North Wales. In 1296 he routed the Scottish feudal host at Dunbar, apparently after luring them into a fatal charge by means of a feigned retreat.

By the time of Stirling Bridge, Warenne was a veteran of over thirty years of largely successful warfare. Despite his ghastly defeat at the hands of Moray and Wallace, the earl was not disgraced or stripped of command. Edward put him in charge of counter-operations, and in the following months Warenne recaptured Berwick and led the fourth battalion at Falkirk. Despite claiming he was too old and ill, he continued to serve in Scotland: in August 1300, at the River Cree, he rode beside King Edward in a massed cavalry charge that swept the army of Buchan, Comyn of Badenoch and d’Umfraville from the field.

By the time of Stirling Bridge, Warenne was a veteran of over thirty years of largely successful warfare. Despite his ghastly defeat at the hands of Moray and Wallace, the earl was not disgraced or stripped of command. Edward put him in charge of counter-operations, and in the following months Warenne recaptured Berwick and led the fourth battalion at Falkirk. Despite claiming he was too old and ill, he continued to serve in Scotland: in August 1300, at the River Cree, he rode beside King Edward in a massed cavalry charge that swept the army of Buchan, Comyn of Badenoch and d’Umfraville from the field. John de Warenne, then. Not a very nice man, probably, and will always be remembered for Stirling Bridge. But he deserves better than Lord Bottoms.

Published on August 16, 2019 06:14

August 15, 2019

Hawarden Wood (2)

The Battle of Hawarden Wood, 1157 (Two) Henry II obviously did not expect an easy time of it in north Wales: the knights he summoned were ordered to serve for ninety days, triple the usual length of feudal service. His chancellor, the ill-fated Thomas Becket, consulted a soothsayer and palm reader before agreeing to accompany the king.

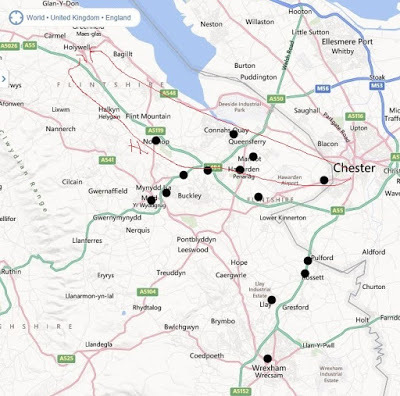

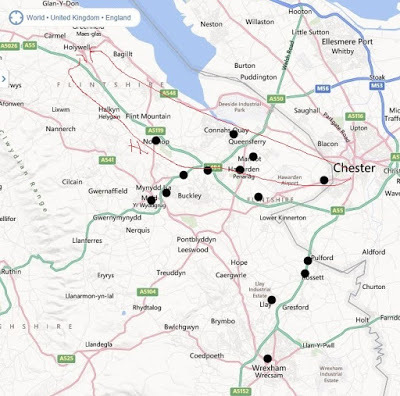

The king split his army in two. The main body marched up the estuary route to attack Owain’s entrenched position, while a flanking force was sent up past Hawarden, Ewloe and Northop to attack Owain on the landward side (see my utterly wonderful map). This was probably a smaller force of mounted knights and included the retinues of Henry of Essex, Eustace Fitz John and Earl Roger Clare.

Owain had predicted the flank attack and placed two of his sons, Cynan and Dafydd, inside the woods of Hawarden with some young Welsh warriors or ‘juveniles’. The English were ambushed and a ‘hard battle’ ensued. Eustace was killed and the standard bearer, Henry of Essex, fled for his life. The Welsh chronicles generally give the impression that the English were routed and slaughtered as they fled back to the plain:

‘And against them came Dafydd ab Owain and he pursued them as far as the strand of Chester, slaughtering them murderously’.

This version of events does not tally with other sources, including the personal testimony of Henry of Essex; a very rare eyewitness account for a battle in this period. After the standard fell, Earl Roger Clare picked it up and rallied the army:

‘Earl Roger Clare, a man renowned in birth and more renowned for his deeds of arms, quickly ran forward with his men of Clare, and raised the standard of the lord king, which revived the strength and courage of the whole army’.

The English flanking force, though badly mauled, broke through the ambush into open country. Henry had thus succeeded in flanking Owain’s position, which forced the latter to abandon his trenches:

‘And when Owain heard that the king was coming against him from the rear side, and he saw the knights approaching from the other side, and with them a mighty host under arms, he left that place and retreated as far as the place that was called Cil Owain.’

Cil Owain is otherwise called Tal Llyn Pennant. Owain’s enemy, King Madog ap Maredudd of Powys, pursued the Venedotians and put his army between the king and Owain, ‘where he might have the first encounter’. The casualties suffered by both sides in the wood are implied by a curious tale reported by Gerald of Wales, who mourns a dead dog:

‘In the wood of Coleshill, a Welsh juvenile was killed when the said king’s army was advancing through; the greyhound who accompanied him did not desert his master’s corpse for eight days, though without food; but with a wonderful attachment lovingly defended it from the attacks of dogs, wolves and birds of prey. What son of his father what Nisus to Euryales, what Polynices to Tydeus, what Orestes to Pylades, would have shown such loving regard? Therefore, as a mark of approval to the dog, who was almost starved to death, the people of England, although hostile to the Welsh, ordered that the now stinking dog was buried with the kindness of human nature.’

The king split his army in two. The main body marched up the estuary route to attack Owain’s entrenched position, while a flanking force was sent up past Hawarden, Ewloe and Northop to attack Owain on the landward side (see my utterly wonderful map). This was probably a smaller force of mounted knights and included the retinues of Henry of Essex, Eustace Fitz John and Earl Roger Clare.

Owain had predicted the flank attack and placed two of his sons, Cynan and Dafydd, inside the woods of Hawarden with some young Welsh warriors or ‘juveniles’. The English were ambushed and a ‘hard battle’ ensued. Eustace was killed and the standard bearer, Henry of Essex, fled for his life. The Welsh chronicles generally give the impression that the English were routed and slaughtered as they fled back to the plain:

‘And against them came Dafydd ab Owain and he pursued them as far as the strand of Chester, slaughtering them murderously’.

This version of events does not tally with other sources, including the personal testimony of Henry of Essex; a very rare eyewitness account for a battle in this period. After the standard fell, Earl Roger Clare picked it up and rallied the army:

‘Earl Roger Clare, a man renowned in birth and more renowned for his deeds of arms, quickly ran forward with his men of Clare, and raised the standard of the lord king, which revived the strength and courage of the whole army’.

The English flanking force, though badly mauled, broke through the ambush into open country. Henry had thus succeeded in flanking Owain’s position, which forced the latter to abandon his trenches:

‘And when Owain heard that the king was coming against him from the rear side, and he saw the knights approaching from the other side, and with them a mighty host under arms, he left that place and retreated as far as the place that was called Cil Owain.’

Cil Owain is otherwise called Tal Llyn Pennant. Owain’s enemy, King Madog ap Maredudd of Powys, pursued the Venedotians and put his army between the king and Owain, ‘where he might have the first encounter’. The casualties suffered by both sides in the wood are implied by a curious tale reported by Gerald of Wales, who mourns a dead dog:

‘In the wood of Coleshill, a Welsh juvenile was killed when the said king’s army was advancing through; the greyhound who accompanied him did not desert his master’s corpse for eight days, though without food; but with a wonderful attachment lovingly defended it from the attacks of dogs, wolves and birds of prey. What son of his father what Nisus to Euryales, what Polynices to Tydeus, what Orestes to Pylades, would have shown such loving regard? Therefore, as a mark of approval to the dog, who was almost starved to death, the people of England, although hostile to the Welsh, ordered that the now stinking dog was buried with the kindness of human nature.’

Published on August 15, 2019 09:36