David Pilling's Blog, page 48

September 13, 2019

Meanwhile in Outremer...

In mid-November 1271 the Lord Edward rode out from Acre into the Plain of Sharon at the head of some 7000 men, including the Hospitallers and Templars and a large contingent of Cypriots. Edward’s strategy is fairly clear. In recent years the Mamluks had encircled the remnant of the Kingdom of Jerusalem by strengthening the three fortresses of Safad, Beaufort and Qaqun. While the sultan and his field army were in northern Syria, to deal with Edward’s Mongol allies, there was an opportunity to attack one of these forts. Christian and Islamic sources give very different accounts of what followed.

According to the Chronicle of Melrose Abbey in Scotland, Edward acted on the advice of a local hermit, a member of a sect called the Sulian, who lived in the wilderness and worshipped John the Baptist. The Sulian came to Acre and told Edward that the people of Caconia (Qaqun) had gone out to feed their flocks and herds, and were enjoying themselves in the open air. Edward and his men advanced by night marches, to deceive the infidel, and ambushed the holiday-makers early in the morning. The Saracens were massacred, down to the last woman and child, ‘for they were the enemies of the faith of Christ’.

The Melrose annalist does not express disapproval of the slaughter of defenceless innocents. Instead it is presented as a noble act, since they were all pagans and deserved to die.

A different version is supplied by Al-Makrizi, himself a Sunni Muslim and a Mamluk-era historian. According to him, Edward and his crusaders attacked the fortified town of Qaqun. They did not wipe out a bunch of hippy nomads: rather, the crusaders ambushed an armoured convoy on its way to supply the fort. The Mamluks suffered heavy casualties. Over fifteen hundred Turcopoles, native light cavalry, were slaughtered. One of the sultan’s chief cavalry officers, Hosam-eddin, was killed, and another emir, Rokn-eddin-Djalik, badly wounded. The provincial governor, Bedjka-Alai, was forced to evacuate the town. This implies the crusaders destroyed the convoy and then decided to have a slap at storming Qaqun itself.

Qaqun

Qaqun

Rather than a smash-and-grab raid, the crusaders appear to have occupied the town. A messenger raced to inform Baibars, who was at Damascus. The sultan sent an emir, Akousch-Schemsi, with troops hurriedly raised from Ain-Djalout, to recover Qaqun. Upon seeing their approach, the outnumbered crusaders decided to get out of Dodge and retreat to Acre.

The remains of Qaqun can still be seen, and is used by the locals as a goatshed during the winter.

According to the Chronicle of Melrose Abbey in Scotland, Edward acted on the advice of a local hermit, a member of a sect called the Sulian, who lived in the wilderness and worshipped John the Baptist. The Sulian came to Acre and told Edward that the people of Caconia (Qaqun) had gone out to feed their flocks and herds, and were enjoying themselves in the open air. Edward and his men advanced by night marches, to deceive the infidel, and ambushed the holiday-makers early in the morning. The Saracens were massacred, down to the last woman and child, ‘for they were the enemies of the faith of Christ’.

The Melrose annalist does not express disapproval of the slaughter of defenceless innocents. Instead it is presented as a noble act, since they were all pagans and deserved to die.

A different version is supplied by Al-Makrizi, himself a Sunni Muslim and a Mamluk-era historian. According to him, Edward and his crusaders attacked the fortified town of Qaqun. They did not wipe out a bunch of hippy nomads: rather, the crusaders ambushed an armoured convoy on its way to supply the fort. The Mamluks suffered heavy casualties. Over fifteen hundred Turcopoles, native light cavalry, were slaughtered. One of the sultan’s chief cavalry officers, Hosam-eddin, was killed, and another emir, Rokn-eddin-Djalik, badly wounded. The provincial governor, Bedjka-Alai, was forced to evacuate the town. This implies the crusaders destroyed the convoy and then decided to have a slap at storming Qaqun itself.

Qaqun

QaqunRather than a smash-and-grab raid, the crusaders appear to have occupied the town. A messenger raced to inform Baibars, who was at Damascus. The sultan sent an emir, Akousch-Schemsi, with troops hurriedly raised from Ain-Djalout, to recover Qaqun. Upon seeing their approach, the outnumbered crusaders decided to get out of Dodge and retreat to Acre.

The remains of Qaqun can still be seen, and is used by the locals as a goatshed during the winter.

Published on September 13, 2019 07:13

September 12, 2019

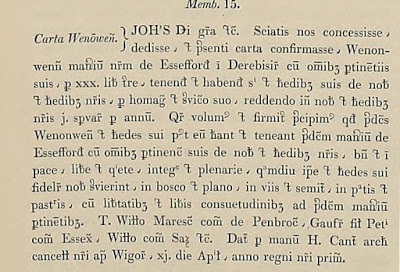

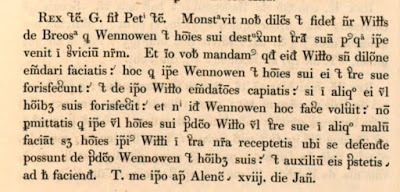

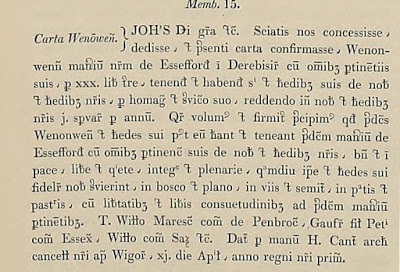

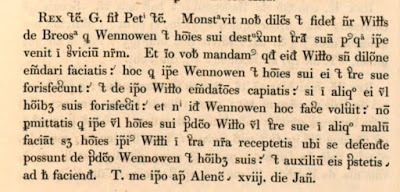

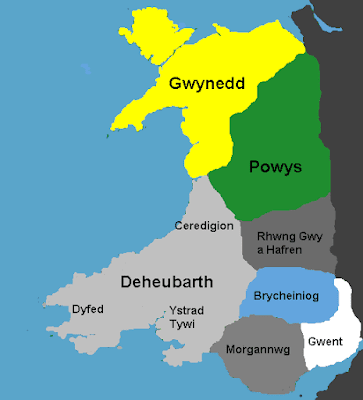

The wars of Gwenwynwyn (6)

After the massacre of his allies at Painscastle, Prince Gwenwynwyn went from strength to strength. In December 1199, alarmed at the rise of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth in the north, King John confirmed Gwenwynwyn in all his lands in north and south Wales and Powys. This was followed by a grant of the manor of Ashford in Derbyshire, and a visit to Powys by a high-powered royal delegation led by Hubert Walter, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Hugh Bardolf, one of John’s intimates. The purpose of the visit was to explain to Gwenwynwyn the king’s reasons for a truce with Llywelyn, and to obtain his approval. Having used the English to wipe out his local rivals, Gwenwynwyn was now the supreme power in south Wales and perceived as a counterweight to Prince Llywelyn.

In the next year Gwenwynwyn married Margaret Corbet of the Corbets of Caus, a powerful family of the central Shropshire March, who held a significant network of castles in the region. At the same time he forged a partnership with Earl Ranulf of Chester, thus extending Powysian influence into the northeast marches. These alliances meant the Marchers would not combine against Gwenwynwyn when he went on the offensive.

Secure on his northern flank, he was now free to attack his principal enemies, Roger Mortimer and William Braose. Gwenwynwyn was almost certainly behind the Welsh attack on the Mortimer castle of Gwrtheyrnion in Maelienydd. Smart as ever, he took steps to avoid blame: on the very day the castle fell, 7 July 1202, Gwenwynwyn was at Strata Marcella confirming the foundation charter of his father, Owain Cyfeiliog. Two regular members of his teulu, Dafydd Goch and Cadwgan ap Griffri, were absent and probably overseeing the siege operations.

The fall of Gwrtherynion allowed the Powysians to attack the Braose lordships of Elfael, Builth, Radnor and Brecon. It isn’t certain which of these were targeted, but the Rotuli Litterarum record that Gwenwynwyn attacked Braose lands in 1204 and 1205. Again, all this vigorous and sustained military action suggests the disaster at Painscastle had little effect on Powys.

‘When we consider his expansion of the bounds of southern Powys, his power and influence in Deheubarth, the March and even parts of Gwynedd, and his apparent alliance with Ranulf of Chester, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that in the years around the turn of the century Gwenwynwyn enjoyed a primacy within Wales that had few parallels in the twelfth century’. - David Stephenson

In the next year Gwenwynwyn married Margaret Corbet of the Corbets of Caus, a powerful family of the central Shropshire March, who held a significant network of castles in the region. At the same time he forged a partnership with Earl Ranulf of Chester, thus extending Powysian influence into the northeast marches. These alliances meant the Marchers would not combine against Gwenwynwyn when he went on the offensive.

Secure on his northern flank, he was now free to attack his principal enemies, Roger Mortimer and William Braose. Gwenwynwyn was almost certainly behind the Welsh attack on the Mortimer castle of Gwrtheyrnion in Maelienydd. Smart as ever, he took steps to avoid blame: on the very day the castle fell, 7 July 1202, Gwenwynwyn was at Strata Marcella confirming the foundation charter of his father, Owain Cyfeiliog. Two regular members of his teulu, Dafydd Goch and Cadwgan ap Griffri, were absent and probably overseeing the siege operations.

The fall of Gwrtherynion allowed the Powysians to attack the Braose lordships of Elfael, Builth, Radnor and Brecon. It isn’t certain which of these were targeted, but the Rotuli Litterarum record that Gwenwynwyn attacked Braose lands in 1204 and 1205. Again, all this vigorous and sustained military action suggests the disaster at Painscastle had little effect on Powys.

‘When we consider his expansion of the bounds of southern Powys, his power and influence in Deheubarth, the March and even parts of Gwynedd, and his apparent alliance with Ranulf of Chester, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that in the years around the turn of the century Gwenwynwyn enjoyed a primacy within Wales that had few parallels in the twelfth century’. - David Stephenson

Published on September 12, 2019 07:39

September 11, 2019

The wars of Gwenwynwyn (5)

In August 1198 Hubert Walter, Archbishop of Canterbury, sent envoys to negotiate with the Welsh army camped outside Painscastle. According to the Brutiau, the Welsh leaders responded thus:

And the Welsh said that they would burn their cities for the Saxons once they had taken the castle, and that they would carry off their spoils and destroy them too (Peniarth).

This attitude is confirmed by Hubert’s letters to Gerald of Wales, in which he wrote of ‘those proud Welshmen who would take no warning’.

Perhaps the Welsh were confident in their numbers or trusted in Prince Gwenwynwyn. He was probably laying siege to Welshpool, and his allies might have hoped Gwenwynwyn would march to their aid. He did not.

Both armies advanced for battle. They were arranged in the standard three lines, one behind the other; this was the typical pattern for set-piece battles in medieval Wales. The Welsh put their foot soldiers in the front line, cavalry and infantry in the second, cavalry only in the third. The English put infantry in the front, knights in the second, and a big mixed reserve in the third.

The location of the battle is uncertain. Painscastle stands at the meeting of several routes in the valley of the Bach Howey, and the river itself runs a twisting course before the hill on which the castle motte stands. The Welsh probably advanced to block any approach from the old Roman road to the south via Hay on Wye. West of Painscastle was the Welsh-held cantref of Buellt, east an impassable marsh.

The rejection of peace terms enraged the English. A lowly sergeant, Walter Ham of Trumpington in Cambridge, stood up and declared he wished to die, since he was unimportant and the Welsh could not gloat over the death of a nobody. He mounted his horse and charged into the first line of Welsh infantry. Walter rode down two men, seized a third and broke his neck. He then turned and shouted “King’s men, king’s men - come with me, strike, strike, we will triumph!”

The first line or ‘battle’ of English infantry threw discipline to the winds and charged. What followed was Crug Mawr in reverse: it seems the Welsh were caught advancing up the sloping ground of the Begwns, south of the river. The unexpected ferocity of the English assault threw them backwards, into the second line, which rapidly disintegrated and plunged back down to the river. The English commander, Geoffrey Fitz Peter, threw his knights forward to complete the rout and drive away the mounted Welsh reserve.

Local tradition speaks of bones and ancient swords discovered in the trout pool discovered in the south side of the brook. If true, this would suggest many of the Welsh drowned as they tried to escape. The chronicles supply a horrific casualty list:

And so this unheard of massacre and unaccustomed killing occurred, with the rest Anarawd ab Einion, Owain Cascob ap Cadwallon, Rhiryd ab Iestyn and Robert ap Hywel were killed and Maredudd ap Cynan was imprisoned (Annales Cambriae)

The slaughter of so many princes suggests they were killed in the first rush of fighting, as they tried to prevent the rout. Welsh and English sources agree that between three to four thousand Welsh soldiers were slain. The Annals of Chester state that many nobles of Gwynedd were killed, and the men of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. Only one Englishman died, and he was accidentally shot by a comrade. Walter Ham was slightly injured and suffered from a limp for eight days afterwards.

Paincastle was an utter catastrophe, arguably the worst military defeat ever suffered by the Welsh. There is a distinct whiff of conspiracy over Gwenwynwyn’s involvement. He was in English pay, and no Powysians appear on the list of killed or captured. His actions in the following years suggest the Powysian army was intact, while his local rivals rotted in the Bach Howey.

And the Welsh said that they would burn their cities for the Saxons once they had taken the castle, and that they would carry off their spoils and destroy them too (Peniarth).

This attitude is confirmed by Hubert’s letters to Gerald of Wales, in which he wrote of ‘those proud Welshmen who would take no warning’.

Perhaps the Welsh were confident in their numbers or trusted in Prince Gwenwynwyn. He was probably laying siege to Welshpool, and his allies might have hoped Gwenwynwyn would march to their aid. He did not.

Both armies advanced for battle. They were arranged in the standard three lines, one behind the other; this was the typical pattern for set-piece battles in medieval Wales. The Welsh put their foot soldiers in the front line, cavalry and infantry in the second, cavalry only in the third. The English put infantry in the front, knights in the second, and a big mixed reserve in the third.

The location of the battle is uncertain. Painscastle stands at the meeting of several routes in the valley of the Bach Howey, and the river itself runs a twisting course before the hill on which the castle motte stands. The Welsh probably advanced to block any approach from the old Roman road to the south via Hay on Wye. West of Painscastle was the Welsh-held cantref of Buellt, east an impassable marsh.

The rejection of peace terms enraged the English. A lowly sergeant, Walter Ham of Trumpington in Cambridge, stood up and declared he wished to die, since he was unimportant and the Welsh could not gloat over the death of a nobody. He mounted his horse and charged into the first line of Welsh infantry. Walter rode down two men, seized a third and broke his neck. He then turned and shouted “King’s men, king’s men - come with me, strike, strike, we will triumph!”

The first line or ‘battle’ of English infantry threw discipline to the winds and charged. What followed was Crug Mawr in reverse: it seems the Welsh were caught advancing up the sloping ground of the Begwns, south of the river. The unexpected ferocity of the English assault threw them backwards, into the second line, which rapidly disintegrated and plunged back down to the river. The English commander, Geoffrey Fitz Peter, threw his knights forward to complete the rout and drive away the mounted Welsh reserve.

Local tradition speaks of bones and ancient swords discovered in the trout pool discovered in the south side of the brook. If true, this would suggest many of the Welsh drowned as they tried to escape. The chronicles supply a horrific casualty list:

And so this unheard of massacre and unaccustomed killing occurred, with the rest Anarawd ab Einion, Owain Cascob ap Cadwallon, Rhiryd ab Iestyn and Robert ap Hywel were killed and Maredudd ap Cynan was imprisoned (Annales Cambriae)

The slaughter of so many princes suggests they were killed in the first rush of fighting, as they tried to prevent the rout. Welsh and English sources agree that between three to four thousand Welsh soldiers were slain. The Annals of Chester state that many nobles of Gwynedd were killed, and the men of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. Only one Englishman died, and he was accidentally shot by a comrade. Walter Ham was slightly injured and suffered from a limp for eight days afterwards.

Paincastle was an utter catastrophe, arguably the worst military defeat ever suffered by the Welsh. There is a distinct whiff of conspiracy over Gwenwynwyn’s involvement. He was in English pay, and no Powysians appear on the list of killed or captured. His actions in the following years suggest the Powysian army was intact, while his local rivals rotted in the Bach Howey.

Published on September 11, 2019 05:23

September 10, 2019

The wars of Gwenwynwyn (4)

In June 1198 Gwenwynwyn gathered most of the princes of Wales under his banner and marched on Painscastle. Inside were the retainers of William Braose, installed there by Maud de St Valery after her victory in 1195.

The plot then thickens, like day-old porridge. The Welsh chronicles do not emphasise Gwenwynwyn’s presence at Painscastle, and it is possible he split his army in two. Pipe Roll evidence suggests John Lestrange still held Welshpool in 1198, and Gwenwynwyn may have taken his Powysian troops to besiege the castle; it was, after all, his ancestral stronghold.

His allies, meanwhile, laid siege to Painscastle. They included Anarawd ab Einion of the house of Elfael and Owain ap Cadwallon of Maelienydd. The house of Elfael had been effectively dispossessed by William Braose in 1195, while Maelienydd was overrun by Roger Mortimer in the same year. Both these princes, therefore, were exiles who may have taken shelter with Gwenwynwyn. The army at Painscastle included a large number of Venedotians, probably sent by Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. The presence of his cousin, Maredudd ap Cynan, would suggest as much. Maredudd was also the younger brother of Prince Gruffydd ap Cynan, the chief lord of Gwynedd at this time.

Gwenwynwyn’s allies sat outside Painscastle for three weeks, unable to bombard the castle since they had no artillery. The Brutiau mention this fact but don’t explain it. Why did they have no siege engines? Were the Powysians supposed to supply them?

The new justiciar, Geoffrey Fitz Peter, gathered an army in England and the Marches and advanced towards Painscastle. One of his first acts was to release Gruffydd ap Rhys, the Lord Rhys’s eldest son, whom Gwenwynwyn had sold to the English the previous year. Gruffydd was granted four marks (£2 14s 4d), which suggests he accompanied the army. Further payments were made to Caswallon, Gwenwynwyn’s brother, and Llywelyn ab Owain Fychan. They, too, were probably serving in the army of Fitz Peter.

Incredibly, Gwenwynwyn received a payment of £2 1s 8d from the English. Officially this was to compensate him for damages done to him by Caswallon in time of peace. Or was it a backhander? If so, what happened next suggests he came very cheap.

The plot then thickens, like day-old porridge. The Welsh chronicles do not emphasise Gwenwynwyn’s presence at Painscastle, and it is possible he split his army in two. Pipe Roll evidence suggests John Lestrange still held Welshpool in 1198, and Gwenwynwyn may have taken his Powysian troops to besiege the castle; it was, after all, his ancestral stronghold.

His allies, meanwhile, laid siege to Painscastle. They included Anarawd ab Einion of the house of Elfael and Owain ap Cadwallon of Maelienydd. The house of Elfael had been effectively dispossessed by William Braose in 1195, while Maelienydd was overrun by Roger Mortimer in the same year. Both these princes, therefore, were exiles who may have taken shelter with Gwenwynwyn. The army at Painscastle included a large number of Venedotians, probably sent by Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. The presence of his cousin, Maredudd ap Cynan, would suggest as much. Maredudd was also the younger brother of Prince Gruffydd ap Cynan, the chief lord of Gwynedd at this time.

Gwenwynwyn’s allies sat outside Painscastle for three weeks, unable to bombard the castle since they had no artillery. The Brutiau mention this fact but don’t explain it. Why did they have no siege engines? Were the Powysians supposed to supply them?

The new justiciar, Geoffrey Fitz Peter, gathered an army in England and the Marches and advanced towards Painscastle. One of his first acts was to release Gruffydd ap Rhys, the Lord Rhys’s eldest son, whom Gwenwynwyn had sold to the English the previous year. Gruffydd was granted four marks (£2 14s 4d), which suggests he accompanied the army. Further payments were made to Caswallon, Gwenwynwyn’s brother, and Llywelyn ab Owain Fychan. They, too, were probably serving in the army of Fitz Peter.

Incredibly, Gwenwynwyn received a payment of £2 1s 8d from the English. Officially this was to compensate him for damages done to him by Caswallon in time of peace. Or was it a backhander? If so, what happened next suggests he came very cheap.

Published on September 10, 2019 09:18

September 9, 2019

The wars of Gwenwynwyn (3)

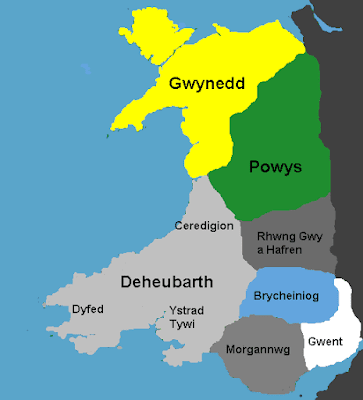

In 1197 the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth - ‘the unconquerable leader of all Wales - died and left a brood of quarrelsome sons to fight over their inheritance. One of them, Maelgwn, had fled Deheubarth while his father was still alive and taken refuge with Prince Gwenwynwyn in southern Powys.

Powis Castle

Powis Castle

As soon as the old man was dead, Gwenwynwn gave Maelgwn an army and sent him to attack his brother and Rhys’s heir-designate, Gruffudd. Maelgwn blazed through Ceredigion, capturing Aberystwyth and all the other castles in the region. Finally he seized Gruffudd and handed him over to Gwenwynwyn, a fairly clear indication that he regarded the latter as his overlord. Gwenwynwyn sold his prisoner to the English in exchange for the castle of Carreg Hofa.

The lord of Powys was playing a blinder: he had expanded his territory, got rid of an enemy, reduced the English presence without provoking a response, and conquered Ceredigion without lifting a finger. He was now well on his way to challenging the rulers of Gwynedd and Deheubarth for supremacy in Wales.

Some evidence of his aspirations is found in surviving charters. In one he styles himself ‘prince’ and in another three ‘prince of Powys’. In another he uses the style ‘Prince of Powys and Lord of Arwystli’: Arwystli was a cantref and kingdom sometimes associated with Powys, but not integrated with it. In another charter, an agreement between Gwenwynwyn and the monks of Strata Marcella, he is ‘princeps W’. This looks like an abbreviation of Princeps Walliae or Prince of Wales (although, strictly speaking it should be Principem or Principis). If this was an announcement of Gwenwynwyn’s claim to the principality, it was a very muted one. Being a canny sort of chap, perhaps he chose to keep his powder dry until he could properly enforce the claim.

Powis Castle

Powis CastleAs soon as the old man was dead, Gwenwynwn gave Maelgwn an army and sent him to attack his brother and Rhys’s heir-designate, Gruffudd. Maelgwn blazed through Ceredigion, capturing Aberystwyth and all the other castles in the region. Finally he seized Gruffudd and handed him over to Gwenwynwyn, a fairly clear indication that he regarded the latter as his overlord. Gwenwynwyn sold his prisoner to the English in exchange for the castle of Carreg Hofa.

The lord of Powys was playing a blinder: he had expanded his territory, got rid of an enemy, reduced the English presence without provoking a response, and conquered Ceredigion without lifting a finger. He was now well on his way to challenging the rulers of Gwynedd and Deheubarth for supremacy in Wales.

Some evidence of his aspirations is found in surviving charters. In one he styles himself ‘prince’ and in another three ‘prince of Powys’. In another he uses the style ‘Prince of Powys and Lord of Arwystli’: Arwystli was a cantref and kingdom sometimes associated with Powys, but not integrated with it. In another charter, an agreement between Gwenwynwyn and the monks of Strata Marcella, he is ‘princeps W’. This looks like an abbreviation of Princeps Walliae or Prince of Wales (although, strictly speaking it should be Principem or Principis). If this was an announcement of Gwenwynwyn’s claim to the principality, it was a very muted one. Being a canny sort of chap, perhaps he chose to keep his powder dry until he could properly enforce the claim.

Published on September 09, 2019 01:08

September 8, 2019

The wars of Gwenwynwyn (2)

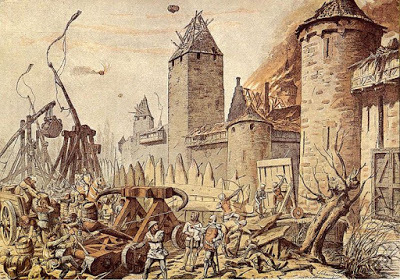

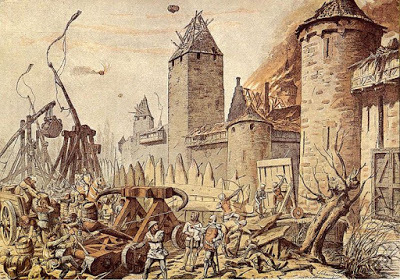

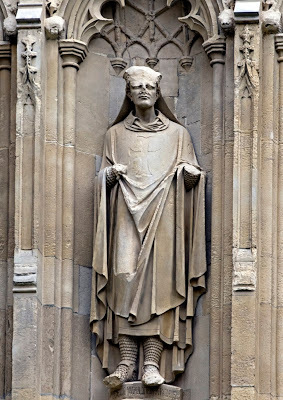

In 1196 the Archbishop of Canterbury, Hubert Walter, gathered a large army to attack Gwenwynwyn’s castle at Welshpool in Powys. Hubert’s army included many of the earls and barons of England as well as ‘all the princes of Gwynedd’; the latter is probably an exaggeration, but he did have Venedotian troops in his host. Which of the princes of Gwynedd sent them is a moot point. Llywelyn ab Iorwerth had yet to establish his supremacy, and the chief lord of Gwynedd at this time was Prince Gruffudd ap Cynan. There was also Dafydd ab Owain, recently expelled from the Perfeddwlad by his nephew Llywelyn.

Thus, within a year of taking over from his father, Gwenwynwyn had united the English crown and elements in Gwynedd against him. The government of Richard I was already funding his half-brother, Caswallon, to launch attacks upon Powys from Shropshire. Hubert led his combined army in person to Welshpool, and the ensuing siege is graphically described in the Brutiau. Attempts to storm the castle were hurled back, with many of the besiegers thrown from the walls or drowned in the moat. At last the castle was undermined by ‘wonderful science’, compelling the garrison to surrender. The presence of miners at Welshpool is confirmed by entries in the Pipe Roll for Michaelmas 1196.

Only one member of the garrison was killed in the siege, and his comrades were allowed to depart in safety and with their weapons. Later in the year, after Hubert withdrew to England, Gwenwywnyn launched an attack upon Welshpool and forced the English garrison to submit. He returned the earlier compliment by allowing them to march away unharmed.

Thus, within a year of taking over from his father, Gwenwynwyn had united the English crown and elements in Gwynedd against him. The government of Richard I was already funding his half-brother, Caswallon, to launch attacks upon Powys from Shropshire. Hubert led his combined army in person to Welshpool, and the ensuing siege is graphically described in the Brutiau. Attempts to storm the castle were hurled back, with many of the besiegers thrown from the walls or drowned in the moat. At last the castle was undermined by ‘wonderful science’, compelling the garrison to surrender. The presence of miners at Welshpool is confirmed by entries in the Pipe Roll for Michaelmas 1196.

Only one member of the garrison was killed in the siege, and his comrades were allowed to depart in safety and with their weapons. Later in the year, after Hubert withdrew to England, Gwenwywnyn launched an attack upon Welshpool and forced the English garrison to submit. He returned the earlier compliment by allowing them to march away unharmed.

Published on September 08, 2019 09:22

The wars of Gwenwynwyn (1)

In 1195 Owain Cyfeiliog entered the monastery of Strata Marcell which he had founded over two decades previously. His eldest son, Gwenwynyn, set about establishing himself as the sole ruler of southern Powys. This process had started back in 1187 when Gwenwynwyn and his brother, Caswallon, lured Owain Fychan to Carreg Hofa and murdered him at night. This allowed their father to seize Owain’s lordship of Mechain.

After their father’s retirement, it seems a rivalry developed between Gwenwynwyn and Caswallon. The Pipe Rolls of the English Exchequer for 1195 record payments for an escort of twenty footsoldiers and eleven cavalry to take Caswallon from Carreg Hofa to Lincoln and back. The castle was in English hands at this time, and at Lincoln Caswallon met with Hubert Walter, Archbishop of Canterbury and justiciar of England in the absence of Richard I. Details of their little talk have not survived, though it seems likely Walter offered Caswallon a heap of gold to make life difficult for Gwenwynwyn.

From all this it appears Caswallon had fled southern Powys and taken refuge in English-held territory. For the next decade he was in receipt of regular payments from the Exchequer, many of them substantial, to keep him in royal service; the old bribe-and-rule strategy of Henry II. Caswallon was also given custody of of the castle and lands of Stretton near the Long Mynd in Shropshire.

From his new castle, Caswallon rode out to plunder the lands of Gwenwynwyn in southern Powys. The Pipe Roll for the year ending at Michaelmas 1198 record a payment from the Exchequer to Gwenwynwyn, to compensate him for damage inflicted by Caswallon.

After their father’s retirement, it seems a rivalry developed between Gwenwynwyn and Caswallon. The Pipe Rolls of the English Exchequer for 1195 record payments for an escort of twenty footsoldiers and eleven cavalry to take Caswallon from Carreg Hofa to Lincoln and back. The castle was in English hands at this time, and at Lincoln Caswallon met with Hubert Walter, Archbishop of Canterbury and justiciar of England in the absence of Richard I. Details of their little talk have not survived, though it seems likely Walter offered Caswallon a heap of gold to make life difficult for Gwenwynwyn.

From all this it appears Caswallon had fled southern Powys and taken refuge in English-held territory. For the next decade he was in receipt of regular payments from the Exchequer, many of them substantial, to keep him in royal service; the old bribe-and-rule strategy of Henry II. Caswallon was also given custody of of the castle and lands of Stretton near the Long Mynd in Shropshire.

From his new castle, Caswallon rode out to plunder the lands of Gwenwynwyn in southern Powys. The Pipe Roll for the year ending at Michaelmas 1198 record a payment from the Exchequer to Gwenwynwyn, to compensate him for damage inflicted by Caswallon.

Published on September 08, 2019 03:53

August 29, 2019

Powys and FitzEmpress (7, and last)

In 1177 virtually every prince of Wales holding effective rule in the country met Henry II for two conferences. The first was held at Geddington, in Rockingham Forest, where a number of them swore fealty to the king in May. The second was held at Oxford, where a far greater assembly turned up to swear the oath to their king.

It is these meetings that should define Henry’s relationship with the rulers of Wales, not his military campaigns or mythical battles. An earlier meeting had been held at Gloucester in 1175, but that only consisted of representatives from South Wales. The absentees at Oxford were Rhodri, one of the sons of Owain Gwynedd, and his grandsons by another son, Cynan. Owain Fychan, lord of Mechain in Powys, was also absent and possibly uninvited.

Otherwise anyone who was anyone turned up. This was the fruit of Henry’s policy of conciliation since 1165. The first name on the list was the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, now the king’s justiciar for South Wales. From Powys came Owain Cyfeiliog, a regular at the English court and known for his manners and ready wit. Northern Powys was represented by Gruffudd of Bromfield, another of the sons of Madog ap Maredudd. Cadwallon of Maelienydd, destined to be brutally murdered by the Mortimers, was also present. From Gwynedd came Dafydd ab Owain, who married Henry’s sister and persuaded the king to grant him the lordship of Ellesmere in Shropshire. In 1165 Henry had blinded and castrated two of Dafydd’s brothers, but he didn’t seem to mind; indeed, it removed some potential opposition.

Afterwards Dafydd was confident enough to help the Earl of Chester invade Maelor. Owain Fychan was now left isolated. Out of favour with the king, he had no protection against the vengeance of his enemies in Powys. In 1187 he was ambushed by Gwenwynwyn and Cadwallon, two of the sons of Owain Cyfeiliog, and put to death. The death was brought about by ‘nocturnal treachery and plot’, suggesting a knife in the back. The killers went unpunished, and it is doubtful the king gave two hoots.

'The spirit of concession shown by the crown at the Council of Oxford marks a definite stage in the long struggle between Wales and the English power. A period of truce has been reached, during which England abandons all attempts upon the independence of its ancient foe and is content to see Rhys ap Gruffudd and his lesser companions in arms grow strong and rich and influential.'

- Sir John Lloyd

It is these meetings that should define Henry’s relationship with the rulers of Wales, not his military campaigns or mythical battles. An earlier meeting had been held at Gloucester in 1175, but that only consisted of representatives from South Wales. The absentees at Oxford were Rhodri, one of the sons of Owain Gwynedd, and his grandsons by another son, Cynan. Owain Fychan, lord of Mechain in Powys, was also absent and possibly uninvited.

Otherwise anyone who was anyone turned up. This was the fruit of Henry’s policy of conciliation since 1165. The first name on the list was the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, now the king’s justiciar for South Wales. From Powys came Owain Cyfeiliog, a regular at the English court and known for his manners and ready wit. Northern Powys was represented by Gruffudd of Bromfield, another of the sons of Madog ap Maredudd. Cadwallon of Maelienydd, destined to be brutally murdered by the Mortimers, was also present. From Gwynedd came Dafydd ab Owain, who married Henry’s sister and persuaded the king to grant him the lordship of Ellesmere in Shropshire. In 1165 Henry had blinded and castrated two of Dafydd’s brothers, but he didn’t seem to mind; indeed, it removed some potential opposition.

Afterwards Dafydd was confident enough to help the Earl of Chester invade Maelor. Owain Fychan was now left isolated. Out of favour with the king, he had no protection against the vengeance of his enemies in Powys. In 1187 he was ambushed by Gwenwynwyn and Cadwallon, two of the sons of Owain Cyfeiliog, and put to death. The death was brought about by ‘nocturnal treachery and plot’, suggesting a knife in the back. The killers went unpunished, and it is doubtful the king gave two hoots.

'The spirit of concession shown by the crown at the Council of Oxford marks a definite stage in the long struggle between Wales and the English power. A period of truce has been reached, during which England abandons all attempts upon the independence of its ancient foe and is content to see Rhys ap Gruffudd and his lesser companions in arms grow strong and rich and influential.'

- Sir John Lloyd

Published on August 29, 2019 07:49

August 28, 2019

Powys and FitzEmpress (6)

In 1171, after a decade of war, there was another war. Owain Cyfeiliog’s foundation of the abbey of Strata Marcella was regarded as a direct challenge by his father-in-law Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, who had himself refounded Strata Florida in the 1160s.

While King Henry was busy in Ireland, Rhys invaded Cyfeiliog to attack Owain. The main result of the conflict was the death of Iorwerth Goch, whom the poet Cynddelw describes as slain in the fighting. This is confirmed by the Exchequer subsidy payments to Iorwerth, which suddenly cease after 47 weeks of the financial year for 1170-1. The killing of Iorwerth, one of the mainstays of Henry’s Welsh policy, seems to have caused a change of attitude in the king.

Owain Cyfeiliog lost the war and had to give over seven hostages to Rhys. When the king returned from Ireland, he summoned to Rhys to what must have been an awkward interview in the Forest of Dean. Instead of being punished, Rhys ‘entered into friendship’ with Henry, and gave over horses and oxen to the king as well as hostages. As a result of royal favour, Rhys never again interfered in the politics of Cyfeiliog.

Henry’s handling of the Welsh princes was thus more adroit than is sometimes acknowledged. When it became clear that Rhys and Owain could no longer be played off against each other, the king cultivated personal friendships with them. He became so close to Owain Cyfeiliog the Welshman was not afraid to mock Henry to his face, as in the following anecdote from Gerald of Wales:

‘One day when he [Owain] was sitting at table with the King in Shrewsbury, Henry passed to him one of his own loaves, to do him honour, as the custom is, and to show a mark of his affection. With the King’s eyes on him, Owain immediately broke the loaf into portions, as if it were Communion bread. He spread the pieces out in a row, again as if he were at Holy Communion, picked them up one at a time and went on eating until they were all finished. Henry asked him what he thought he was doing. ‘I am imitating you, my lord’, answered Owain. In this subtle and witty way, he was alluding to the well-known avariciousness of the King, who had the habit of keeping church benefices vacant for as long as possible so that he could enjoy the revenues’.

While King Henry was busy in Ireland, Rhys invaded Cyfeiliog to attack Owain. The main result of the conflict was the death of Iorwerth Goch, whom the poet Cynddelw describes as slain in the fighting. This is confirmed by the Exchequer subsidy payments to Iorwerth, which suddenly cease after 47 weeks of the financial year for 1170-1. The killing of Iorwerth, one of the mainstays of Henry’s Welsh policy, seems to have caused a change of attitude in the king.

Owain Cyfeiliog lost the war and had to give over seven hostages to Rhys. When the king returned from Ireland, he summoned to Rhys to what must have been an awkward interview in the Forest of Dean. Instead of being punished, Rhys ‘entered into friendship’ with Henry, and gave over horses and oxen to the king as well as hostages. As a result of royal favour, Rhys never again interfered in the politics of Cyfeiliog.

Henry’s handling of the Welsh princes was thus more adroit than is sometimes acknowledged. When it became clear that Rhys and Owain could no longer be played off against each other, the king cultivated personal friendships with them. He became so close to Owain Cyfeiliog the Welshman was not afraid to mock Henry to his face, as in the following anecdote from Gerald of Wales:

‘One day when he [Owain] was sitting at table with the King in Shrewsbury, Henry passed to him one of his own loaves, to do him honour, as the custom is, and to show a mark of his affection. With the King’s eyes on him, Owain immediately broke the loaf into portions, as if it were Communion bread. He spread the pieces out in a row, again as if he were at Holy Communion, picked them up one at a time and went on eating until they were all finished. Henry asked him what he thought he was doing. ‘I am imitating you, my lord’, answered Owain. In this subtle and witty way, he was alluding to the well-known avariciousness of the King, who had the habit of keeping church benefices vacant for as long as possible so that he could enjoy the revenues’.

Published on August 28, 2019 00:41

August 26, 2019

Powys and FitzEmpress (5)

In 1166, the coalition of Welsh princes that had defied Henry II turned on each other. Iorwerth Goch was driven from Mochnant in Powys by his kinsman and former ally, Owain Cyfeiliog, assisted by his cousin, Owain Fychan. Iorwerth Goch was a half-brother of Madog ap Maredudd, uncle to Owain Cyfeiliog and father of Owain Fychan, so this was very much a family affair.

The two Owains shared their conquest between them. Owain Fychan took the northern part, Mochnant Is Rhaedr, while Owain Cyfeiliog took Mochnant Uwch Rhaedr. Their victory was short-lived. Now Powys had fallen into a state of civil war, Owain Gwynedd seized the opportunity to launch yet another invasion. Along with Rhys ap Gruffudd of Deheubath, he attacked Owain Cyfeiliog and drove him into exile. Two years previously these three had presented a united front against the King of England; now they were at each other’s throats.

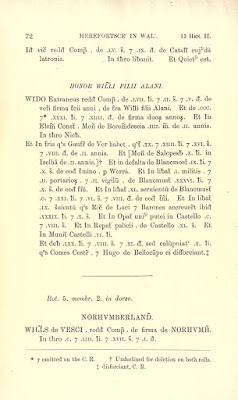

Owain Fychan appears to have colluded with the invaders. Their price was much of northern Powys, claimed by Rhys ap Gruffudd. In return Owain held sway over southern Powys as a dependency of Gwynedd. The poet Llywelyn Fardd describes Owain defeating an English force at the Stiperstones in Shropshire, possibly troops sent by King Henry to restore Owain Cyfeiliog. Owain Cyfeiliog and his uncle Iorwerth Goch were now in exile in England. They joined forces once again and recruited more soldiers from the king. Some details of this army are contained in the Pipe Roll for 1167, which records wages for sixty sergeants gathered at Oswestry by order of Richard de Lucy, co-justiciar of England.

The reconquest began in Caereinion, where the combined Franco-Welsh army destroyed Owain Fychan’s castle of Mathrafal and slaughtered the garrison. Owain Gwynedd and Rhys were busy conquering the king’s castles in Tegeingl, so the counter-attack in Powys was part of a wider conflict. King Henry now appointed Iorwerth Goch as the leading member of a group of Welsh castellans who controlled royal estates on the northern March. This included the castle of Chirk (pictured) and a large fee of over £90 a year. He was also granted the lordship of the vale of Ceiriog. Owain Cyfeiliog had restored his position in southern Powys by 1170, when he founded the Cistercian abbey of Strata Marcella. In the same year he had the satisfaction of learning of the death of his old rival, Owain Gwynedd.

The two Owains shared their conquest between them. Owain Fychan took the northern part, Mochnant Is Rhaedr, while Owain Cyfeiliog took Mochnant Uwch Rhaedr. Their victory was short-lived. Now Powys had fallen into a state of civil war, Owain Gwynedd seized the opportunity to launch yet another invasion. Along with Rhys ap Gruffudd of Deheubath, he attacked Owain Cyfeiliog and drove him into exile. Two years previously these three had presented a united front against the King of England; now they were at each other’s throats.

Owain Fychan appears to have colluded with the invaders. Their price was much of northern Powys, claimed by Rhys ap Gruffudd. In return Owain held sway over southern Powys as a dependency of Gwynedd. The poet Llywelyn Fardd describes Owain defeating an English force at the Stiperstones in Shropshire, possibly troops sent by King Henry to restore Owain Cyfeiliog. Owain Cyfeiliog and his uncle Iorwerth Goch were now in exile in England. They joined forces once again and recruited more soldiers from the king. Some details of this army are contained in the Pipe Roll for 1167, which records wages for sixty sergeants gathered at Oswestry by order of Richard de Lucy, co-justiciar of England.

The reconquest began in Caereinion, where the combined Franco-Welsh army destroyed Owain Fychan’s castle of Mathrafal and slaughtered the garrison. Owain Gwynedd and Rhys were busy conquering the king’s castles in Tegeingl, so the counter-attack in Powys was part of a wider conflict. King Henry now appointed Iorwerth Goch as the leading member of a group of Welsh castellans who controlled royal estates on the northern March. This included the castle of Chirk (pictured) and a large fee of over £90 a year. He was also granted the lordship of the vale of Ceiriog. Owain Cyfeiliog had restored his position in southern Powys by 1170, when he founded the Cistercian abbey of Strata Marcella. In the same year he had the satisfaction of learning of the death of his old rival, Owain Gwynedd.

Published on August 26, 2019 09:39