David Pilling's Blog, page 50

August 14, 2019

Hawarden Wood

The Battle of Hawarden Wood, 1157 (Part One) In August 1157, three months after the defeat of his navy on Mon, Henry II set out to bring North Wales back under royal control. In 1093 the English crown had controlled all of Mon and Gwynedd, but now its authority stopped at Ewloe Castle, just seven miles from Chester.

On 17 July Henry held a great council at Northampton, where he summoned his Welsh vassals. These included Cadwaladr, Owain Gwynedd’s brother, who was living in Shropshire on a royal pension of £7 per annum. Another was King Madog ap Maredudd of Powys who received £8 10 shillings from the king in this year. In 1150 Madog had been defeated by Owain at Coleshill, and he hoped to recover the western part of the Perfeddwlad. Madog was accompanied by his brother Iorwerth, also on royal wages and captain of the Powysian penteulu (bodyguard). Madog brought his under-king, King Hywel ap Ieuaf of Arwystli. Therefore this was not a straight Anglo-Welsh conflict, but a battle between Owain Gwynedd and the Crown, the latter supported by Welsh kings, princes and nobles as well as his English subjects.

There were also a number of Scots in the royal army. The Chronicle of Melrose reports that Malcolm IV of Scotland came to Henry at Chester and ‘became his man’:

There were also a number of Scots in the royal army. The Chronicle of Melrose reports that Malcolm IV of Scotland came to Henry at Chester and ‘became his man’:

‘King Malcolm of Scotland came to King Henry at Chester where he became his man in the same manner as his grandfather had to the old king Henry, saving all his dignities.’

Henry’s enemy, Owain Gwynedd, raised an army with his sons Hywel, Cynan and Dafydd. They built a ‘great entrenchment’ at Basingwerk, and most of the accounts lay great emphasis on the huge ditches constructed by the Venedotians. The site can probably be identified with the ancient motte at Coleshill Castle, near Holywell and Basingwerk Abbey, where the ravine has been visibly steepened to make a fortified site. The ditches around the castle to the west and south are formidable obstacles, being between 50-60 feet deep. To the west are the main artificial defences, consisting of a ditch 15 feet deep and 35 across, protecting the inner ward.

On 17 July Henry held a great council at Northampton, where he summoned his Welsh vassals. These included Cadwaladr, Owain Gwynedd’s brother, who was living in Shropshire on a royal pension of £7 per annum. Another was King Madog ap Maredudd of Powys who received £8 10 shillings from the king in this year. In 1150 Madog had been defeated by Owain at Coleshill, and he hoped to recover the western part of the Perfeddwlad. Madog was accompanied by his brother Iorwerth, also on royal wages and captain of the Powysian penteulu (bodyguard). Madog brought his under-king, King Hywel ap Ieuaf of Arwystli. Therefore this was not a straight Anglo-Welsh conflict, but a battle between Owain Gwynedd and the Crown, the latter supported by Welsh kings, princes and nobles as well as his English subjects.

There were also a number of Scots in the royal army. The Chronicle of Melrose reports that Malcolm IV of Scotland came to Henry at Chester and ‘became his man’:

There were also a number of Scots in the royal army. The Chronicle of Melrose reports that Malcolm IV of Scotland came to Henry at Chester and ‘became his man’:‘King Malcolm of Scotland came to King Henry at Chester where he became his man in the same manner as his grandfather had to the old king Henry, saving all his dignities.’

Henry’s enemy, Owain Gwynedd, raised an army with his sons Hywel, Cynan and Dafydd. They built a ‘great entrenchment’ at Basingwerk, and most of the accounts lay great emphasis on the huge ditches constructed by the Venedotians. The site can probably be identified with the ancient motte at Coleshill Castle, near Holywell and Basingwerk Abbey, where the ravine has been visibly steepened to make a fortified site. The ditches around the castle to the west and south are formidable obstacles, being between 50-60 feet deep. To the west are the main artificial defences, consisting of a ditch 15 feet deep and 35 across, protecting the inner ward.

Published on August 14, 2019 00:37

August 13, 2019

Ravaging Galloway

The Bruces ravage Scotland.

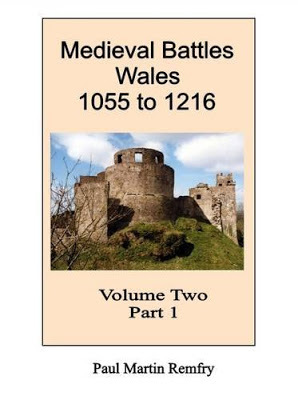

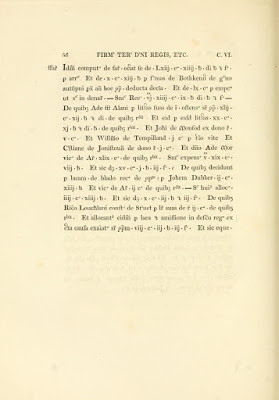

Attached are pages of the accounts of the Great Chamberlain of Scotland for the year 1286. After the death of Alexander III and the birth of a stillborn child to his widow, Queen Yolande, there was an inevitable scramble for the vacant Scottish throne.

Leading the charge was Robert de Bruce, called the Competitor and grandfather of the victor of Bannockburn. Over the winter of 1286-7 Bruce and his kinsmen laid waste to Galloway. Their first target was Dumfries, held by Sir William Sinclair, a close ally of the Comyns. They followed up by taking the Balliol castle of Buittle, fifteen miles to the southwest. Bruce’s son, another Robert, took a separate force to storm Wigtown, which was probably held by Alexander Comyn, Earl of Buchan.

The aim of the Bruces was to block any attempt by the Guardians to set up Alexander’s daughter, the Maid of Norway, as Queen of Scotland, or put the crown on John Balliol. Everyone was playing for high stakes, and the accounts of the Bruce campaign in Galloway show this: lands and manors burnt, fields left uncultivated, flocks scattered, and a crippling loss of revenue for the next two years. The response of the Guardians was to strengthen the defence of royal castles from Edinburgh to Ayr, ‘to defend the peace and tranquillity of the realm’.

Attached are pages of the accounts of the Great Chamberlain of Scotland for the year 1286. After the death of Alexander III and the birth of a stillborn child to his widow, Queen Yolande, there was an inevitable scramble for the vacant Scottish throne.

Leading the charge was Robert de Bruce, called the Competitor and grandfather of the victor of Bannockburn. Over the winter of 1286-7 Bruce and his kinsmen laid waste to Galloway. Their first target was Dumfries, held by Sir William Sinclair, a close ally of the Comyns. They followed up by taking the Balliol castle of Buittle, fifteen miles to the southwest. Bruce’s son, another Robert, took a separate force to storm Wigtown, which was probably held by Alexander Comyn, Earl of Buchan.

The aim of the Bruces was to block any attempt by the Guardians to set up Alexander’s daughter, the Maid of Norway, as Queen of Scotland, or put the crown on John Balliol. Everyone was playing for high stakes, and the accounts of the Bruce campaign in Galloway show this: lands and manors burnt, fields left uncultivated, flocks scattered, and a crippling loss of revenue for the next two years. The response of the Guardians was to strengthen the defence of royal castles from Edinburgh to Ayr, ‘to defend the peace and tranquillity of the realm’.

Published on August 13, 2019 01:11

August 9, 2019

Widowed, childless, landless...

In 1282 Margaret of Bromfield, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s sister, fell from royal favour. The cause of her downfall is unknown, though she may have incurred the wrath of Edward I by insisting on her rights. In an undated petition she asked the king for justice because Earl Warenne had ‘wrongfully’ seized the manor of Eyton and three vills which Margaret held of her brother-in-law, Gruffydd Fychan.

The king’s response was unequivocal. ‘This woman,’ the answer reads, ‘offended against the king to such an extent that the king is not held to do her favour.’ Margaret was thus deprived of her lands, which along with the rest of Bromfield and Yale was granted to Earl Warenne on 7 October 1282. She also lost her sons. Her two children, Gruffydd and Llywelyn, were probably dead by October, when Warenne was granted all the land of Bromfield, ‘which Griffith and Llewelyn, sons of Madoc Vaughan, held at the beginning of the said war’.

Historians from the 16th, 18th and early 20th centuries claim the boys were murdered by their guardians, Earl Warenne and Roger Mortimer, who drowned them in the Dee at Holt Bridge. The story was cited by T. Pennant in 1784, who quoted an MS by the Reverend Price, Keeper of the Bodleian Library. Another source, JYW Lloyd, claimed in the 1880s that the story came from a continuation of the Peniarth MS 20 version Brut y Tywysogion. The Brut, however, contains no such account. The story can be traced back no further than David Powel’s Historie of Cambria in 1584, a deeply problematic work.

Even so, if the boys weren’t drowned they were certainly made to disappear. Their age in 1282 is unknown, so possibly they were killed in battle. Margaret was thus left widowed, childless and landless. A few weeks later her brother Prince Llywelyn, and brother-in-law Llywelyn Fychan, were both slain at Cilmeri.

Margaret presumably spent the next year and a half living on charity. On 11 May 1284 she came into Chancery at Aberconwy and demanded her dower lands from Earl Warrenne and Gruffydd Fychan. King Edward responded by issuing her with two grants. On 30 May he ordered Margaret to be given five marks a year (about £3) out of charity, to be paid from the Exchequer at Caernarfon. In the second, dated 22 October, he restored to Margaret the vills of Boduan and Hydref for life, which gave her an extra annual income of £1 and £5 respectively. Margaret did not get her dower, but the king permitted her some land and income. Her troubles were not over. In 1297 the king ordered the chamberlain at Caernarfon to pay over the full amount of five marks ‘without delay’: it seems Margaret was being cheated of half the annual payment.

There is one last reference to her in 1299, when the king granted land worth £15 to Morgan ap Maredudd. The land had come into the king’s hands because of the recent death of Margaret, ‘sister of Llewellin, then prince of Wales’.

The king’s response was unequivocal. ‘This woman,’ the answer reads, ‘offended against the king to such an extent that the king is not held to do her favour.’ Margaret was thus deprived of her lands, which along with the rest of Bromfield and Yale was granted to Earl Warenne on 7 October 1282. She also lost her sons. Her two children, Gruffydd and Llywelyn, were probably dead by October, when Warenne was granted all the land of Bromfield, ‘which Griffith and Llewelyn, sons of Madoc Vaughan, held at the beginning of the said war’.

Historians from the 16th, 18th and early 20th centuries claim the boys were murdered by their guardians, Earl Warenne and Roger Mortimer, who drowned them in the Dee at Holt Bridge. The story was cited by T. Pennant in 1784, who quoted an MS by the Reverend Price, Keeper of the Bodleian Library. Another source, JYW Lloyd, claimed in the 1880s that the story came from a continuation of the Peniarth MS 20 version Brut y Tywysogion. The Brut, however, contains no such account. The story can be traced back no further than David Powel’s Historie of Cambria in 1584, a deeply problematic work.

Even so, if the boys weren’t drowned they were certainly made to disappear. Their age in 1282 is unknown, so possibly they were killed in battle. Margaret was thus left widowed, childless and landless. A few weeks later her brother Prince Llywelyn, and brother-in-law Llywelyn Fychan, were both slain at Cilmeri.

Margaret presumably spent the next year and a half living on charity. On 11 May 1284 she came into Chancery at Aberconwy and demanded her dower lands from Earl Warrenne and Gruffydd Fychan. King Edward responded by issuing her with two grants. On 30 May he ordered Margaret to be given five marks a year (about £3) out of charity, to be paid from the Exchequer at Caernarfon. In the second, dated 22 October, he restored to Margaret the vills of Boduan and Hydref for life, which gave her an extra annual income of £1 and £5 respectively. Margaret did not get her dower, but the king permitted her some land and income. Her troubles were not over. In 1297 the king ordered the chamberlain at Caernarfon to pay over the full amount of five marks ‘without delay’: it seems Margaret was being cheated of half the annual payment.

There is one last reference to her in 1299, when the king granted land worth £15 to Morgan ap Maredudd. The land had come into the king’s hands because of the recent death of Margaret, ‘sister of Llewellin, then prince of Wales’.

Published on August 09, 2019 08:19

August 8, 2019

Margaret at law

At the time she answered the claim against her mother-in-law, Emma Audley, Margaret of Bromfield was also at law against her brother-in-law, Gruffudd Fychan. Grufuddd, an ancestor of Owain Glyn Dwr, held the manor of Glyndyfrdwy, which Margaret claimed he held unjustly against her. Her claim was based on dower rights in Edeyrnion and Glyndyrfdwy, which is confusing as these lands were in Wales and there was no right of dower under Welsh law. We can only assume that once again the law of Cyfraith Hywel had once again been set aside in favour of common law.

Margaret asserted that she was in possession of the land until the death of her husband, Madog ap Gruffudd. Afterwards she was driven out by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in time of war between England and Wales, just as Llywelyn had driven Emma from Maelor Saesneg and Eyton. The prince then gave the land to Gruffudd. This is curious as Llywelyn was said to have given Emma’s lands to Margaret’s husband, Madog. If he was favouring Madog, why would he have driven Madog’s wife - and his own sister - from her lands? Someone was being economical with the truth, and it was probably one of the female plaintiffs.

Unsurprisingly, Gruffudd was confused and wrote to Edward I, asking if the case should be heard before the king’s justices or before Prince Llywelyn. Gruffudd added that he ‘held the land by the king’s permission, in chief of the said prince’. He also made the interesting comment that ‘he fears lest the said Margaret may influence the king against him’. This implies Margaret had enough influence at the English court to worry her rivals. The king’s response was to transfer the case to Llywelyn. On 10 October 1279 Llywelyn wrote to thank the king and report on the hearing. It had been a disaster. Margaret and Gruffudd both appeared before the prince on 28 September, where Margaret produced her charters for the land. She appears to have conducted her own defence without attorneys. Margaret refused to part with the charters or have copies made of them, as urged by Gruffudd, even though Llywelyn warned her three times that this was a requirement of Welsh law.

Llywelyn claimed that Margaret was ‘minus instructa’ - too little instructed - to argue her case, and set another date for the hearing. This was even worse. In his second report to the king, dated 15 December 1279, Llywelyn claimed Margaret still refused to obey court procedure. He also claimed that Margaret had ‘procured’ certain ‘false statements’ to use against him i.e. bogus evidence. As so often with this family, there was little love lost.

The outcome is uncertain, though it seems Margaret came to an amicable settlement with Gruffudd. In a later petition Margaret said she had obtained good charters from Gruffudd for her claims of dower in Corwen and Edeirnion. She also had the income from two bond vills in Caernarfon and the income from the lands of her children. Between 1277-82, therefore, Margaret was living high on the hog. It wouldn’t last.

[Yes, I'm aware that is not a medieval train...]

Margaret asserted that she was in possession of the land until the death of her husband, Madog ap Gruffudd. Afterwards she was driven out by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in time of war between England and Wales, just as Llywelyn had driven Emma from Maelor Saesneg and Eyton. The prince then gave the land to Gruffudd. This is curious as Llywelyn was said to have given Emma’s lands to Margaret’s husband, Madog. If he was favouring Madog, why would he have driven Madog’s wife - and his own sister - from her lands? Someone was being economical with the truth, and it was probably one of the female plaintiffs.

Unsurprisingly, Gruffudd was confused and wrote to Edward I, asking if the case should be heard before the king’s justices or before Prince Llywelyn. Gruffudd added that he ‘held the land by the king’s permission, in chief of the said prince’. He also made the interesting comment that ‘he fears lest the said Margaret may influence the king against him’. This implies Margaret had enough influence at the English court to worry her rivals. The king’s response was to transfer the case to Llywelyn. On 10 October 1279 Llywelyn wrote to thank the king and report on the hearing. It had been a disaster. Margaret and Gruffudd both appeared before the prince on 28 September, where Margaret produced her charters for the land. She appears to have conducted her own defence without attorneys. Margaret refused to part with the charters or have copies made of them, as urged by Gruffudd, even though Llywelyn warned her three times that this was a requirement of Welsh law.

Llywelyn claimed that Margaret was ‘minus instructa’ - too little instructed - to argue her case, and set another date for the hearing. This was even worse. In his second report to the king, dated 15 December 1279, Llywelyn claimed Margaret still refused to obey court procedure. He also claimed that Margaret had ‘procured’ certain ‘false statements’ to use against him i.e. bogus evidence. As so often with this family, there was little love lost.

The outcome is uncertain, though it seems Margaret came to an amicable settlement with Gruffudd. In a later petition Margaret said she had obtained good charters from Gruffudd for her claims of dower in Corwen and Edeirnion. She also had the income from two bond vills in Caernarfon and the income from the lands of her children. Between 1277-82, therefore, Margaret was living high on the hog. It wouldn’t last.

[Yes, I'm aware that is not a medieval train...]

Published on August 08, 2019 01:25

August 6, 2019

The case of Maud Clifford

The (alleged) rape of Maud Clifford.

Maud was the daughter of Margaret Clifford, herself the daughter of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. She lived most of her life in or near Wales, and tried (without success) to arrange a Christian burial for Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Her father was Walter Clifford of Llandovery, who allied with his father-in-law and Richard de Clare against Henry III. Famously, Walter is said to have forced one of Henry’s envoys to eat his letters, wax seal and all.

Henry III

Henry III

Maud was married to William Longespée and widowed young when her husband died in 1257, from injuries received in a tournament. As her father’s sole heir, Maud received the whole of the Clifford inheritance. She was now extremely rich and thus a desirable commodity.

In September 1270 Maud was forcibly abducted from her manor of Canford in Dorset by John Giffard of Brimpsfield. On 5 October King Henry ordered Giffard to respond to the charge of abduction, and also informed Maud she could also appear in court if she wished. Henry’s outrage at the incident is a bit rich: he had himself connived in the abduction of Joan of Bayeux and Margaret of Bromfield, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s sister.

Giffard repeatedly ignored the summons and held Maud in custody until she agreed to marry him. When Henry sent two of his officers to check on her condition, it was reported she was ‘too infirm’ to make the journey to appear before the king. Two more officials were sent in March 1271, to discover her wishes concerning the marriage. There was no longer any talk of punishing Giffard: he had successfully defied the king whilst abusing the woman in his power. Henry had threatened Giffard in the strongest possible terms, but in the end did nothing.

The question of Maud’s rape depends on interpretation. Henry used the terms ‘rapuistis’ and ‘rapuerat’ on the two occasions he wrote to her. The word ‘rapta’ or ‘raptus’ could mean seizure/abduction as well as rape, and it is often difficult to tell if the offence involved a sexual element. However, Maud’s eldest daughter by Giffard, Katherine, was born in 1272. She was not married until some time after March 1271, and it is entirely possible that Giffard raped Maud to get her pregnant and secure the marriage. The sinister references to her infirmity may (or may not) support this.

Maud was the daughter of Margaret Clifford, herself the daughter of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. She lived most of her life in or near Wales, and tried (without success) to arrange a Christian burial for Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Her father was Walter Clifford of Llandovery, who allied with his father-in-law and Richard de Clare against Henry III. Famously, Walter is said to have forced one of Henry’s envoys to eat his letters, wax seal and all.

Henry III

Henry IIIMaud was married to William Longespée and widowed young when her husband died in 1257, from injuries received in a tournament. As her father’s sole heir, Maud received the whole of the Clifford inheritance. She was now extremely rich and thus a desirable commodity.

In September 1270 Maud was forcibly abducted from her manor of Canford in Dorset by John Giffard of Brimpsfield. On 5 October King Henry ordered Giffard to respond to the charge of abduction, and also informed Maud she could also appear in court if she wished. Henry’s outrage at the incident is a bit rich: he had himself connived in the abduction of Joan of Bayeux and Margaret of Bromfield, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s sister.

Giffard repeatedly ignored the summons and held Maud in custody until she agreed to marry him. When Henry sent two of his officers to check on her condition, it was reported she was ‘too infirm’ to make the journey to appear before the king. Two more officials were sent in March 1271, to discover her wishes concerning the marriage. There was no longer any talk of punishing Giffard: he had successfully defied the king whilst abusing the woman in his power. Henry had threatened Giffard in the strongest possible terms, but in the end did nothing.

The question of Maud’s rape depends on interpretation. Henry used the terms ‘rapuistis’ and ‘rapuerat’ on the two occasions he wrote to her. The word ‘rapta’ or ‘raptus’ could mean seizure/abduction as well as rape, and it is often difficult to tell if the offence involved a sexual element. However, Maud’s eldest daughter by Giffard, Katherine, was born in 1272. She was not married until some time after March 1271, and it is entirely possible that Giffard raped Maud to get her pregnant and secure the marriage. The sinister references to her infirmity may (or may not) support this.

Published on August 06, 2019 01:42

The (alleged) rape of Maud Clifford.Maud was the daughter...

The (alleged) rape of Maud Clifford.

Maud was the daughter of Margaret Clifford, herself the daughter of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. She lived most of her life in or near Wales, and tried (without success) to arrange a Christian burial for Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Her father was Walter Clifford of Llandovery, who allied with his father-in-law and Richard de Clare against Henry III. Famously, Walter is said to have forced one of Henry’s envoys to eat his letters, wax seal and all.

Henry III

Henry III

Maud was married to William Longespée and widowed young when her husband died in 1257, from injuries received in a tournament. As her father’s sole heir, Maud received the whole of the Clifford inheritance. She was now extremely rich and thus a desirable commodity.

In September 1270 Maud was forcibly abducted from her manor of Canford in Dorset by John Giffard of Brimpsfield. On 5 October King Henry ordered Giffard to respond to the charge of abduction, and also informed Maud she could also appear in court if she wished. Henry’s outrage at the incident is a bit rich: he had himself connived in the abduction of Joan of Bayeux and Margaret of Bromfield, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s sister.

Giffard repeatedly ignored the summons and held Maud in custody until she agreed to marry him. When Henry sent two of his officers to check on her condition, it was reported she was ‘too infirm’ to make the journey to appear before the king. Two more officials were sent in March 1271, to discover her wishes concerning the marriage. There was no longer any talk of punishing Giffard: he had successfully defied the king whilst abusing the woman in his power. Henry had threatened Giffard in the strongest possible terms, but in the end did nothing.

The question of Maud’s rape depends on interpretation. Henry used the terms ‘rapuistis’ and ‘rapuerat’ on the two occasions he wrote to her. The word ‘rapta’ or ‘raptus’ could mean seizure/abduction as well as rape, and it is often difficult to tell if the offence involved a sexual element. However, Maud’s eldest daughter by Giffard, Katherine, was born in 1272. She was not married until some time after March 1271, and it is entirely possible that Giffard raped Maud to get her pregnant and secure the marriage. The sinister references to her infirmity may (or may not) support this.

Maud was the daughter of Margaret Clifford, herself the daughter of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. She lived most of her life in or near Wales, and tried (without success) to arrange a Christian burial for Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Her father was Walter Clifford of Llandovery, who allied with his father-in-law and Richard de Clare against Henry III. Famously, Walter is said to have forced one of Henry’s envoys to eat his letters, wax seal and all.

Henry III

Henry IIIMaud was married to William Longespée and widowed young when her husband died in 1257, from injuries received in a tournament. As her father’s sole heir, Maud received the whole of the Clifford inheritance. She was now extremely rich and thus a desirable commodity.

In September 1270 Maud was forcibly abducted from her manor of Canford in Dorset by John Giffard of Brimpsfield. On 5 October King Henry ordered Giffard to respond to the charge of abduction, and also informed Maud she could also appear in court if she wished. Henry’s outrage at the incident is a bit rich: he had himself connived in the abduction of Joan of Bayeux and Margaret of Bromfield, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s sister.

Giffard repeatedly ignored the summons and held Maud in custody until she agreed to marry him. When Henry sent two of his officers to check on her condition, it was reported she was ‘too infirm’ to make the journey to appear before the king. Two more officials were sent in March 1271, to discover her wishes concerning the marriage. There was no longer any talk of punishing Giffard: he had successfully defied the king whilst abusing the woman in his power. Henry had threatened Giffard in the strongest possible terms, but in the end did nothing.

The question of Maud’s rape depends on interpretation. Henry used the terms ‘rapuistis’ and ‘rapuerat’ on the two occasions he wrote to her. The word ‘rapta’ or ‘raptus’ could mean seizure/abduction as well as rape, and it is often difficult to tell if the offence involved a sexual element. However, Maud’s eldest daughter by Giffard, Katherine, was born in 1272. She was not married until some time after March 1271, and it is entirely possible that Giffard raped Maud to get her pregnant and secure the marriage. The sinister references to her infirmity may (or may not) support this.

Published on August 06, 2019 01:42

August 5, 2019

The Ogre and Cadwallon

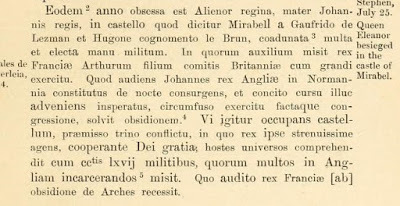

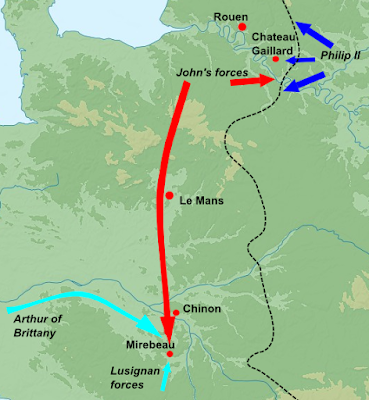

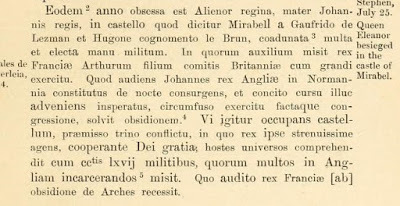

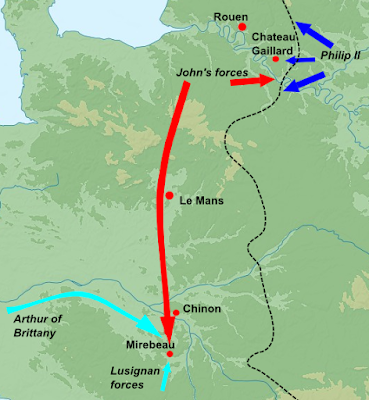

The Welsh at Mirabeau. The Battle of Mirabeau, fought in Normandy on 1 August 1202, was King John’s only major victory over his enemies in France. He quickly threw away his political gains - quite literally, in the case of his nephew Arthur of Brittany - but the victory was still notable. Like his predecessors and successors, John made good use of Welsh troops.

One of John’s captains at Mirabeau was William Braose, lord of Brecon and Radnor, who would be remembered as the Ogre of Abergavenny. He probably brought Welshmen with him, raised from his lands on the March. Another was Cadwallon ab Ifor Bach of Senghennydd, who served on this campaign at the head of 200 Welsh infantry. Another 540 Welsh foot and twenty horse sergeants are known to have been present.

Cadwallon had served in royal armies in France since 1187, when he survived Henry II’s final defeat at Le Mans. Afterwards he fought for Richard I against Philip Augustus, and then for John. Between these stints of royal service in France, he went home and fought the English in his native Powys. The contradiction doesn’t seem to have bothered him very much. In 1204 he was back in Normandy with one Lleision ap Morgan and 200 Welsh foot, possibly the veterans of Mirabeau. A few years later he was fighting for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth against John, and the king’s accounts for 1212 record a bounty of six shillings for the heads of the men of Cadwallon ab Ifor.

As an aside, Cadwallon was a kinsman of Gerald of Wales, who records meeting his cousin in Rouen in 1204. Attached are the Braose arms, or at least those attributed to the Ogre by Matthew Paris.

One of John’s captains at Mirabeau was William Braose, lord of Brecon and Radnor, who would be remembered as the Ogre of Abergavenny. He probably brought Welshmen with him, raised from his lands on the March. Another was Cadwallon ab Ifor Bach of Senghennydd, who served on this campaign at the head of 200 Welsh infantry. Another 540 Welsh foot and twenty horse sergeants are known to have been present.

Cadwallon had served in royal armies in France since 1187, when he survived Henry II’s final defeat at Le Mans. Afterwards he fought for Richard I against Philip Augustus, and then for John. Between these stints of royal service in France, he went home and fought the English in his native Powys. The contradiction doesn’t seem to have bothered him very much. In 1204 he was back in Normandy with one Lleision ap Morgan and 200 Welsh foot, possibly the veterans of Mirabeau. A few years later he was fighting for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth against John, and the king’s accounts for 1212 record a bounty of six shillings for the heads of the men of Cadwallon ab Ifor.

As an aside, Cadwallon was a kinsman of Gerald of Wales, who records meeting his cousin in Rouen in 1204. Attached are the Braose arms, or at least those attributed to the Ogre by Matthew Paris.

Published on August 05, 2019 04:12

August 4, 2019

Climbing the walls

Vilnius, capital of Lithuania. At the start of September 1390 the city was besieged by Anglo-Prussian forces under Henry of Bolingbroke (later Henry IV), Konrad von Wallenrode and Marshal Engelhardt Rabe of the Teutonic Order. Also among the ‘crusaders’ was Prince Vitold of Lithuania, and the joint campaign or reyse was in fact part of a Lithuanian dynastic dispute; ironically against Vitold’s cousin, King Jogailo, who had just converted Lithuania to Christianity.

This left the Teutonic Order and their allies with no reason to attack Lithuania. Fortunately for them, the wilderness of Samogitia north of the River Neman remained fiercely pagan, so the bloodshed could continue. Bolingbroke’s participation was a family tradition: both his grandfather, Henry of Grosmont, and his father-in-law Humprey de Bohun had campaigned alongside the Knights of Prussia.

The story of the siege grew in the telling on its way back to England. It was reported that Vilnius had been taken due to the daring of Henry and his men, and one English chronicler reported that Henry himself climbed the walls and placed his standard there. Meanwhile his Prussian and Livonian allies stood by and watched in awe. In reality it was an Englishman of Henry’s company, a valet of Lord Bourchier, who raised the standard. He did not scale the walls of the city itself, but one of the outlying forts. Vilnius did not fall to the allies, who were forced to withdraw when their supplies of power and provisions ran low. King Jogailo wrote to his commander at Vilnius, Clemens of Mostorzow, vice-chancellor of Poland, congratulating him on the successful resistance.

This left the Teutonic Order and their allies with no reason to attack Lithuania. Fortunately for them, the wilderness of Samogitia north of the River Neman remained fiercely pagan, so the bloodshed could continue. Bolingbroke’s participation was a family tradition: both his grandfather, Henry of Grosmont, and his father-in-law Humprey de Bohun had campaigned alongside the Knights of Prussia.

The story of the siege grew in the telling on its way back to England. It was reported that Vilnius had been taken due to the daring of Henry and his men, and one English chronicler reported that Henry himself climbed the walls and placed his standard there. Meanwhile his Prussian and Livonian allies stood by and watched in awe. In reality it was an Englishman of Henry’s company, a valet of Lord Bourchier, who raised the standard. He did not scale the walls of the city itself, but one of the outlying forts. Vilnius did not fall to the allies, who were forced to withdraw when their supplies of power and provisions ran low. King Jogailo wrote to his commander at Vilnius, Clemens of Mostorzow, vice-chancellor of Poland, congratulating him on the successful resistance.

Published on August 04, 2019 01:29

August 3, 2019

Bonds and sureties

A letter from Cynan ap Maredudd ab Owain, a lord of Ceredigion, to Llywelyn ap Gruffudd:

“Letter, informing the prince that he has bound himself as surety to him for Cadwgan, Cynan’s foster-son, with respect to the latter’s paying £27 sterling in the prince’s mercy of suitable terms fixed by the prince; Cynan is also surety for Cynan’s constancy and fealty to the prince. He therefore prays the prince to end all anger which he has against Cadwgan. He sends this letter to ratify the above, and attests that he is a surety to all who see and read it.”

As Llywelyn used the title ‘Prince of Wales and Lord of Snowdon’ from 1262, this letter is datable to the period between the death of Maredudd in March 1265 and Cynan’s submission to Edward I on 2 May 1277.

This is another example of Llywelyn’s methods of control in Wales. Cadwgan, Cynan’s foster-son, had evidently offended against Llywelyn in some way. The prince’s standard tactic was to oblige a kinsman or neighbour of the offender to stand surety for the latter’s good behaviour. No previous ruler in Wales had used bonds and sureties on such a massive scale, and it appears to have caused outrage among the Welsh polity. The upshot was 1276, when the majority of those Llywelyn had extracted money from defected to the English crown.

“Letter, informing the prince that he has bound himself as surety to him for Cadwgan, Cynan’s foster-son, with respect to the latter’s paying £27 sterling in the prince’s mercy of suitable terms fixed by the prince; Cynan is also surety for Cynan’s constancy and fealty to the prince. He therefore prays the prince to end all anger which he has against Cadwgan. He sends this letter to ratify the above, and attests that he is a surety to all who see and read it.”

As Llywelyn used the title ‘Prince of Wales and Lord of Snowdon’ from 1262, this letter is datable to the period between the death of Maredudd in March 1265 and Cynan’s submission to Edward I on 2 May 1277.

This is another example of Llywelyn’s methods of control in Wales. Cadwgan, Cynan’s foster-son, had evidently offended against Llywelyn in some way. The prince’s standard tactic was to oblige a kinsman or neighbour of the offender to stand surety for the latter’s good behaviour. No previous ruler in Wales had used bonds and sureties on such a massive scale, and it appears to have caused outrage among the Welsh polity. The upshot was 1276, when the majority of those Llywelyn had extracted money from defected to the English crown.

Published on August 03, 2019 01:47

July 31, 2019

Godfathers in Wales

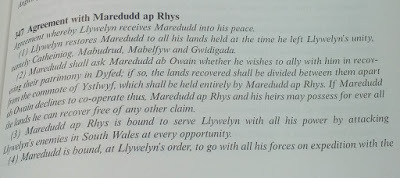

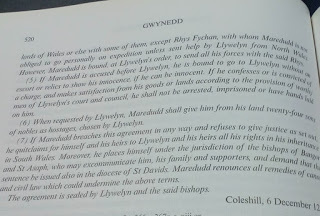

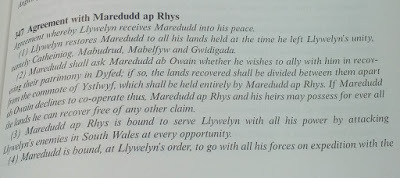

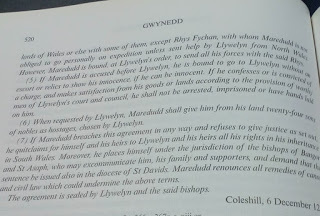

The agreement between Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg, drawn up at Coleshill, 6 December 1261. Via this treaty Llywelyn received Maredudd back into his peace and restored his lands: the lord of Ystrad Tywi had previously broken with the Prince of Wales and reverted to the allegiance of Henry III of England.

J Beverley-Smith remarked that this treaty showed the difficulty in forging a united polity in Wales. Maredudd was bound to serve Llywelyn with all his power in time of war, but was not obliged to serve in person alongside his kinsman Rhys Fychan. Maredudd and Rhys loathed each other, and Llywelyn was trying to avoid conflict by keeping them apart. However, if he didn’t go in person Maredudd was obliged to send his troops to serve under Rhys.

The other problem was that Llywelyn did not trust Maredudd, and arguably made that distrust all too plain. If anyone accused Maredudd, he was ordered to go before Llywelyn and swear to his innocence on holy relics. When requested by Llywelyn, Maredudd had to give up twenty-four hostages from among his nobles. If he ever breached the agreement, he would be excommunicated and forfeit his inheritance. This was quite a comedown for a descendant of the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, who had called himself the Prince of Wales.

A fourth party in the agreement was Maredudd ab Owain of Ceredigion. In 1257 the two Maredudds had won a great victory over the English at Cymerau, but it seems they didn’t get along either. Maredudd was to ask Maredudd ab Owain if he wanted to help him recover his patrimony in Dyfed; if so, the lands would be divided between them. If not, Maredudd ap Rhys would have everything. The very definition of an offer one dare not refuse.

Reading these treaties, it always strikes me that these people - Welsh, English, French or whoever - were the spiritual (and in some cases, lineal) forebears of the Mafia. Now I love me some Godfather, but I wouldn’t like to base an ideology on Michael Corleone and his methods.

J Beverley-Smith remarked that this treaty showed the difficulty in forging a united polity in Wales. Maredudd was bound to serve Llywelyn with all his power in time of war, but was not obliged to serve in person alongside his kinsman Rhys Fychan. Maredudd and Rhys loathed each other, and Llywelyn was trying to avoid conflict by keeping them apart. However, if he didn’t go in person Maredudd was obliged to send his troops to serve under Rhys.

The other problem was that Llywelyn did not trust Maredudd, and arguably made that distrust all too plain. If anyone accused Maredudd, he was ordered to go before Llywelyn and swear to his innocence on holy relics. When requested by Llywelyn, Maredudd had to give up twenty-four hostages from among his nobles. If he ever breached the agreement, he would be excommunicated and forfeit his inheritance. This was quite a comedown for a descendant of the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, who had called himself the Prince of Wales.

A fourth party in the agreement was Maredudd ab Owain of Ceredigion. In 1257 the two Maredudds had won a great victory over the English at Cymerau, but it seems they didn’t get along either. Maredudd was to ask Maredudd ab Owain if he wanted to help him recover his patrimony in Dyfed; if so, the lands would be divided between them. If not, Maredudd ap Rhys would have everything. The very definition of an offer one dare not refuse.

Reading these treaties, it always strikes me that these people - Welsh, English, French or whoever - were the spiritual (and in some cases, lineal) forebears of the Mafia. Now I love me some Godfather, but I wouldn’t like to base an ideology on Michael Corleone and his methods.

Published on July 31, 2019 01:17