David Pilling's Blog, page 51

July 29, 2019

Templars and Mamluks

Back to Eddie One's crusade.

The prince enjoyed a close relationship with the leaders of the Military Orders: the knights of the Temple, the Hospitallers and the Teutonic Knights. Edward’s need for men and materials in the Holy Land played a major role in this, as did his reliance on established communication networks and the political influence of the Orders.

His dependence on them was also dictated by finance. Edward and his followers borrowed about £15,000 from the Hospitallers and Templars, for example. He also enjoyed a long correspondence through the 1270s with the Masters of the Hospital and the Temple. Joseph Chauncy, treasurer of the Hospital since 1248, returned to England and became Edward’s own treasurer until 1281. Edward also gave custody of a tower he built in Acre, the Tower of the English, over to the lesser Order of St Edward of Acre.

The Military Orders were not the power of old. In 1268 the Hospitallers may have been able to field 300 knights in the whole of the Latin East, with a similar commitment from the Temple. It is unlikely that these men were ever gathered in force in one place. Nor were they particularly aggressive. Knights such as Oliver de Termes (a former Cathar) frequently advised caution against the Mamluks, and avoided direct confrontation when possible. This helped to preserve what was left of Christian forces in the East, but did nothing to recover lost territory. The Latin field forces in the East were simply no match for Baibars and the Mamluk army.

Acre

Acre

The prince enjoyed a close relationship with the leaders of the Military Orders: the knights of the Temple, the Hospitallers and the Teutonic Knights. Edward’s need for men and materials in the Holy Land played a major role in this, as did his reliance on established communication networks and the political influence of the Orders.

His dependence on them was also dictated by finance. Edward and his followers borrowed about £15,000 from the Hospitallers and Templars, for example. He also enjoyed a long correspondence through the 1270s with the Masters of the Hospital and the Temple. Joseph Chauncy, treasurer of the Hospital since 1248, returned to England and became Edward’s own treasurer until 1281. Edward also gave custody of a tower he built in Acre, the Tower of the English, over to the lesser Order of St Edward of Acre.

The Military Orders were not the power of old. In 1268 the Hospitallers may have been able to field 300 knights in the whole of the Latin East, with a similar commitment from the Temple. It is unlikely that these men were ever gathered in force in one place. Nor were they particularly aggressive. Knights such as Oliver de Termes (a former Cathar) frequently advised caution against the Mamluks, and avoided direct confrontation when possible. This helped to preserve what was left of Christian forces in the East, but did nothing to recover lost territory. The Latin field forces in the East were simply no match for Baibars and the Mamluk army.

Acre

Acre

Published on July 29, 2019 00:55

July 28, 2019

Treaties and broken oaths

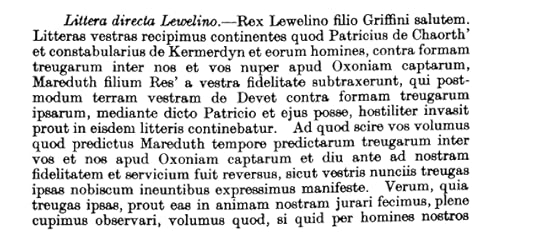

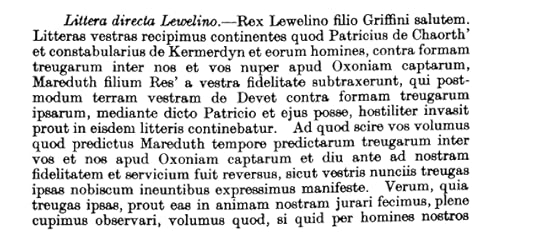

More on the tensions between the houses of Aberffraw and Dinefwr. Letter patent concerning Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg, 26 April 1258.

‘Notification that Llywelyn has promised Maredudd ap Rhys and his heirs, in return for his homage, to protect him together with his heirs, men, lands and castles from the attacks and damage inflicted by his enemies, when requested to do so by Maredudd or his heirs. He has also promised and sworn that he will never capture Maredudd or have him captured, nor imprison his son or accept him as a hostage, nor take Maredudd’s castles into his possession or custody. Further, he grants this letter of safe conduct in perpetuity, allowing no injury to be inflicted upon him or his men whenever they should visit Llywelyn. If Llywelyn should break the terms of this letter, he wishes that he and everyone consenting to it shall be excommunicated and denounced through all the churches of Wales, renouncing all benefit of both ecclesiastical and civil law. The present letter patent has been sealed with the seals of [specified] bishops, abbots and priors and of Llywelyn and drawn up in the form of a chirograph’.

Much awkwardness arose from this agreement. The only reason Maredudd consented to it was to get his son, Rhys, out of Llywelyn’s prison: Rhys had been held hostage since October 1257. However, on 17 June 1258 Henry III informed Llywelyn that Maredudd had sworn homage to the crown. This was only a few weeks after the agreement of 26 April, and it appears Maredudd had played Llywelyn false. According to the Annales Cambriae, Llywelyn held a council with his nobles at Arwysli and there convicted Maredudd of faithlessness. Llywelyn then captured Maredudd and threw him into prison at Criccieth. Maredudd was only freed at Christmas after agreeing to give up Rhys as a hostage and his castles of Dinefwr and Newcastle Emlyn.

Much awkwardness arose from this agreement. The only reason Maredudd consented to it was to get his son, Rhys, out of Llywelyn’s prison: Rhys had been held hostage since October 1257. However, on 17 June 1258 Henry III informed Llywelyn that Maredudd had sworn homage to the crown. This was only a few weeks after the agreement of 26 April, and it appears Maredudd had played Llywelyn false. According to the Annales Cambriae, Llywelyn held a council with his nobles at Arwysli and there convicted Maredudd of faithlessness. Llywelyn then captured Maredudd and threw him into prison at Criccieth. Maredudd was only freed at Christmas after agreeing to give up Rhys as a hostage and his castles of Dinefwr and Newcastle Emlyn.

Dinefwr CastleThis was all very dodgy, on both sides. Maredudd had broken his oath to Llywelyn, but there’s nothing in the treaty of April that says Llywelyn was entitled to break his own promises. The prince could claim that he was punishing a rebellious vassal, just as Edward I later claimed he was punishing Llywelyn. When a new agreement was drawn up between Llywelyn and Maredudd in 1261, the terms were very different. This time Maredudd was obliged to swear that if he broke faith again, his entire inheritance would be forfeited:

Dinefwr CastleThis was all very dodgy, on both sides. Maredudd had broken his oath to Llywelyn, but there’s nothing in the treaty of April that says Llywelyn was entitled to break his own promises. The prince could claim that he was punishing a rebellious vassal, just as Edward I later claimed he was punishing Llywelyn. When a new agreement was drawn up between Llywelyn and Maredudd in 1261, the terms were very different. This time Maredudd was obliged to swear that if he broke faith again, his entire inheritance would be forfeited:

“There was no longer any doubt that the lords of the Principality of Wales were subject to the prince’s jurisdiction, no question that any serious breach of faith on the part of any one of them would result in forfeiture and excommunication. They were no longer allies responding to the prince’s leadership, but tenants who acknowledged his lordship.”

- J Beverley-Smith

‘Notification that Llywelyn has promised Maredudd ap Rhys and his heirs, in return for his homage, to protect him together with his heirs, men, lands and castles from the attacks and damage inflicted by his enemies, when requested to do so by Maredudd or his heirs. He has also promised and sworn that he will never capture Maredudd or have him captured, nor imprison his son or accept him as a hostage, nor take Maredudd’s castles into his possession or custody. Further, he grants this letter of safe conduct in perpetuity, allowing no injury to be inflicted upon him or his men whenever they should visit Llywelyn. If Llywelyn should break the terms of this letter, he wishes that he and everyone consenting to it shall be excommunicated and denounced through all the churches of Wales, renouncing all benefit of both ecclesiastical and civil law. The present letter patent has been sealed with the seals of [specified] bishops, abbots and priors and of Llywelyn and drawn up in the form of a chirograph’.

Much awkwardness arose from this agreement. The only reason Maredudd consented to it was to get his son, Rhys, out of Llywelyn’s prison: Rhys had been held hostage since October 1257. However, on 17 June 1258 Henry III informed Llywelyn that Maredudd had sworn homage to the crown. This was only a few weeks after the agreement of 26 April, and it appears Maredudd had played Llywelyn false. According to the Annales Cambriae, Llywelyn held a council with his nobles at Arwysli and there convicted Maredudd of faithlessness. Llywelyn then captured Maredudd and threw him into prison at Criccieth. Maredudd was only freed at Christmas after agreeing to give up Rhys as a hostage and his castles of Dinefwr and Newcastle Emlyn.

Much awkwardness arose from this agreement. The only reason Maredudd consented to it was to get his son, Rhys, out of Llywelyn’s prison: Rhys had been held hostage since October 1257. However, on 17 June 1258 Henry III informed Llywelyn that Maredudd had sworn homage to the crown. This was only a few weeks after the agreement of 26 April, and it appears Maredudd had played Llywelyn false. According to the Annales Cambriae, Llywelyn held a council with his nobles at Arwysli and there convicted Maredudd of faithlessness. Llywelyn then captured Maredudd and threw him into prison at Criccieth. Maredudd was only freed at Christmas after agreeing to give up Rhys as a hostage and his castles of Dinefwr and Newcastle Emlyn. Dinefwr CastleThis was all very dodgy, on both sides. Maredudd had broken his oath to Llywelyn, but there’s nothing in the treaty of April that says Llywelyn was entitled to break his own promises. The prince could claim that he was punishing a rebellious vassal, just as Edward I later claimed he was punishing Llywelyn. When a new agreement was drawn up between Llywelyn and Maredudd in 1261, the terms were very different. This time Maredudd was obliged to swear that if he broke faith again, his entire inheritance would be forfeited:

Dinefwr CastleThis was all very dodgy, on both sides. Maredudd had broken his oath to Llywelyn, but there’s nothing in the treaty of April that says Llywelyn was entitled to break his own promises. The prince could claim that he was punishing a rebellious vassal, just as Edward I later claimed he was punishing Llywelyn. When a new agreement was drawn up between Llywelyn and Maredudd in 1261, the terms were very different. This time Maredudd was obliged to swear that if he broke faith again, his entire inheritance would be forfeited:“There was no longer any doubt that the lords of the Principality of Wales were subject to the prince’s jurisdiction, no question that any serious breach of faith on the part of any one of them would result in forfeiture and excommunication. They were no longer allies responding to the prince’s leadership, but tenants who acknowledged his lordship.”

- J Beverley-Smith

Published on July 28, 2019 02:11

July 27, 2019

The Pope and Lord Edward

Pope Boniface VIII on Edward I and his father, Henry III.

"The king of England we listen to readily and more readily grant what he asks, and we readily receive and readily listen to his envoys, because we have a special affection for him and have had for a long time; and his father (God bless his soul) was greatly loved. They did us great honour. And we recall when we were in England with the lord Ottobon and were besieged in the Tower of London by the Earl of Gloucester, this king, then a young man, came to deliver us from this siege and he did us many a service, and his father did too. And it was then that we gave this king our particular affection, and formed the opinion from his appearance that with him it was bound to happen that he would be the finest prince in the world, and we believe without a doubt that we did not err in this judgement, for we firmly believe that there is not now living a better prince. True enough, he has some faults, for no man is faultless, but comparing his shortcomings with his advantages, he is of all princes of the world the best, and this we would say out boldly before all the world."

Boniface said this as part of a series of private conversations held with the French chancellor, Pierre Flote, held at Sculcula near Anagni on 21, 22 and 24 August 1300. He refers to the siege of London in 1267, when Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester, held the capital for a few weeks against Henry III and the Lord Edward.

During their talks Boniface asked Pierre if it was the policy of the French to drive the English from their territories on the continent? At which the Frenchman smiled and replied:

"Certainly, sir, what you say is very true."

Which might cast the origins of the Hundred Years War in a slightly different light.

"The king of England we listen to readily and more readily grant what he asks, and we readily receive and readily listen to his envoys, because we have a special affection for him and have had for a long time; and his father (God bless his soul) was greatly loved. They did us great honour. And we recall when we were in England with the lord Ottobon and were besieged in the Tower of London by the Earl of Gloucester, this king, then a young man, came to deliver us from this siege and he did us many a service, and his father did too. And it was then that we gave this king our particular affection, and formed the opinion from his appearance that with him it was bound to happen that he would be the finest prince in the world, and we believe without a doubt that we did not err in this judgement, for we firmly believe that there is not now living a better prince. True enough, he has some faults, for no man is faultless, but comparing his shortcomings with his advantages, he is of all princes of the world the best, and this we would say out boldly before all the world."

Boniface said this as part of a series of private conversations held with the French chancellor, Pierre Flote, held at Sculcula near Anagni on 21, 22 and 24 August 1300. He refers to the siege of London in 1267, when Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester, held the capital for a few weeks against Henry III and the Lord Edward.

During their talks Boniface asked Pierre if it was the policy of the French to drive the English from their territories on the continent? At which the Frenchman smiled and replied:

"Certainly, sir, what you say is very true."

Which might cast the origins of the Hundred Years War in a slightly different light.

Published on July 27, 2019 00:49

July 26, 2019

Angry old cats

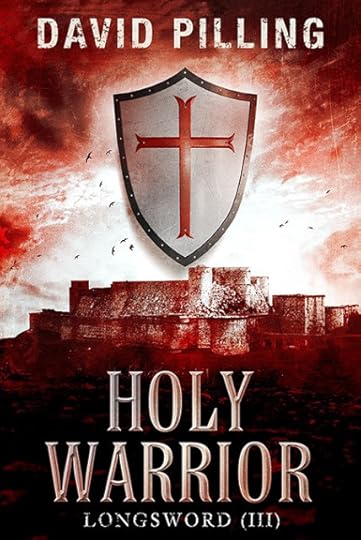

On September 1298 Edward I rejoined his men at Carlisle. Here, according to Guisborough, he got embroiled in yet another row with the earls of Norfolk and Hereford. The earls were allegedly annoyed that Edward had granted the Isle of Arran to Hugh Bisset of Antrim, an Irish pirate, after promising not to make any grants without their advice.

It may be the earls were really aggrieved at Edward’s failure to reward them while dishing out sweet land pie to others. Apart from the grant to Bisset, he granted forfeit Scottish land to Adam Swimburne, the Earl of Lincoln, the Earl of Warwick and Sir Robert Tony. Norfolk and Hereford, meanwhile, were left out in the cold. This was probably due to their behaviour in 1297, when their opposition to Edward’s policies scuppered the Flanders campaign and nearly triggered a civil war in England. Having been snubbed, they flounced off with their noses in the air and left Edward with the remnant of his army at Carlisle.

The king was not yet finished with Scotland. In late September he re-crossed the border with whatever was left of his infantry, and on 1 October laid siege to Jedburgh. Robert Low, a novelist, has described Edward randomly attacking Jedburgh ‘like a graceless old cat’. The king’s lack of grace notwithstanding, the siege was anything but random. Jedburgh was the only Scottish garrison in the southeast, so if Edward took it he would regain control of the area. The army was at Jedburgh until 18 October. Supplies of coal, iron and steel were ordered up for siege engines, and the Scots may have tried to break the siege: on 3 October one of the company of Sir Simon Fraser, at this point wearing his English hat, lost a horse in the king’s service in Selkirk Forest.

Finally Edward lost patience and offered the constable of Jedburgh, John Pencaitland, a bribe of 100 shillings to surrender. John accepted and would serve his new master faithfully in the Berwick garrison. The new constable, Sir Richard Hastangs, was installed at Jedburgh with twelve men-at-arms, forty crossbowmen, twenty archers, four miners, two masons, four diggers and one engineer.

But no cats.

It may be the earls were really aggrieved at Edward’s failure to reward them while dishing out sweet land pie to others. Apart from the grant to Bisset, he granted forfeit Scottish land to Adam Swimburne, the Earl of Lincoln, the Earl of Warwick and Sir Robert Tony. Norfolk and Hereford, meanwhile, were left out in the cold. This was probably due to their behaviour in 1297, when their opposition to Edward’s policies scuppered the Flanders campaign and nearly triggered a civil war in England. Having been snubbed, they flounced off with their noses in the air and left Edward with the remnant of his army at Carlisle.

The king was not yet finished with Scotland. In late September he re-crossed the border with whatever was left of his infantry, and on 1 October laid siege to Jedburgh. Robert Low, a novelist, has described Edward randomly attacking Jedburgh ‘like a graceless old cat’. The king’s lack of grace notwithstanding, the siege was anything but random. Jedburgh was the only Scottish garrison in the southeast, so if Edward took it he would regain control of the area. The army was at Jedburgh until 18 October. Supplies of coal, iron and steel were ordered up for siege engines, and the Scots may have tried to break the siege: on 3 October one of the company of Sir Simon Fraser, at this point wearing his English hat, lost a horse in the king’s service in Selkirk Forest.

Finally Edward lost patience and offered the constable of Jedburgh, John Pencaitland, a bribe of 100 shillings to surrender. John accepted and would serve his new master faithfully in the Berwick garrison. The new constable, Sir Richard Hastangs, was installed at Jedburgh with twelve men-at-arms, forty crossbowmen, twenty archers, four miners, two masons, four diggers and one engineer.

But no cats.

Published on July 26, 2019 06:24

July 25, 2019

Holy Warrior!

W.F. Howes have just released the audio version of LONGSWORD III: (HOLY WARRIOR), narrated by Marston York. If any kind person feels like sharing this glad news, I would be much obliged. Cheers!

LONGSWORD (III): HOLY WARRIOR ON AUDIBLE

LONGSWORD (III): HOLY WARRIOR ON AUDIBLE

Published on July 25, 2019 03:59

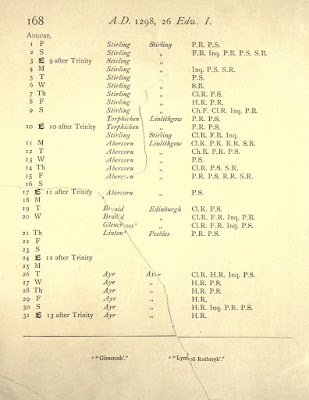

To catch a Bruce

On his return from Stirling, Edward I crossed the scene of his victory at Falkirk en route to Edinburgh and Berwick. Then, on 21 August, he made a sudden about-turn and dashed over to Ayr in the west. According to Guisborough, the king deviated from his intended route after reaching Selkirk Forest.

The king had presumably been alerted to trouble in the west. Robert de Bruce, who submitted to the English in 1297, had swung back to the Scottish cause; a curious decision, in light of the recent battle. Edward arrived too late to catch Bruce, who took to the hills and left the town of Ayr in flames. He had to content himself with seizing Bruce’s castle of Lochmaben (pictured), which fell to the English on 3 September.

Edward had already split his army. The infantry were in Carlisle, while a company of men-at-arms had been sent off under Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, to ravage Perth and St Andrews. Lacy also took Cupar castle: it was later noted that William Ramsay, a Scot admitted to royal wages, had been ‘one of the keepers of Cupar Castle in Fife, at the time when the castle surrendered to the earl of Lincoln at the end of July 1298’.

The king had presumably been alerted to trouble in the west. Robert de Bruce, who submitted to the English in 1297, had swung back to the Scottish cause; a curious decision, in light of the recent battle. Edward arrived too late to catch Bruce, who took to the hills and left the town of Ayr in flames. He had to content himself with seizing Bruce’s castle of Lochmaben (pictured), which fell to the English on 3 September.

Edward had already split his army. The infantry were in Carlisle, while a company of men-at-arms had been sent off under Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, to ravage Perth and St Andrews. Lacy also took Cupar castle: it was later noted that William Ramsay, a Scot admitted to royal wages, had been ‘one of the keepers of Cupar Castle in Fife, at the time when the castle surrendered to the earl of Lincoln at the end of July 1298’.

Published on July 25, 2019 00:17

July 24, 2019

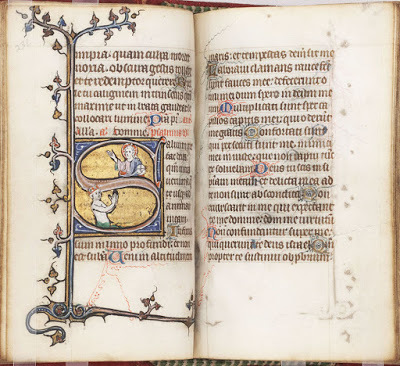

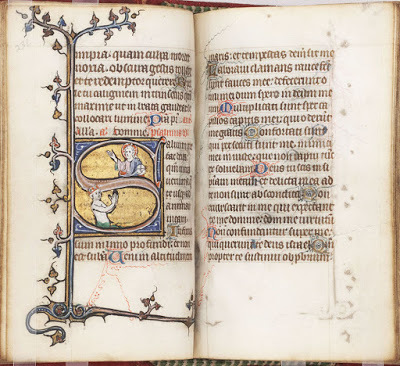

Antiphoners and cruets

Four days after Falkirk, 26 July, Edward I was at Stirling on the Forth. The castle had been held by the Scots since 1297, but surrendered soon after the king and his cavalry appeared before the walls. Edward left on 8 August, when the castle was supplied with food, weapons and furnishings for the chapel. The fifty-eight year old king, still nursing two broken ribs, had more riding ahead of him.

The inventory for Stirling survives, and shows an interesting concern with the refurbishment of the chapel: God came first. John Sampson, the new constable of Stirling, received a silver chalice, a vestment, two towels, a missal, a portoise, an antiphoner, a troper, and two pewter cruets.

I had to Google some of the above. A ‘portoise’ was a breviary, an antiphoner a liturgical book, and a troper a book containing tropes or sequences for the sung parts of the Mass. For their earthly needs the garrison were supplied with 67 quarters of wheat flour, 46 quarters of wheat, 51 quarters of beans, 81 quarters of barley, 143 quarters of malt, 100 large cattle and 217 sheep. For a treat, they also received a box of almonds.

The inventory for Stirling survives, and shows an interesting concern with the refurbishment of the chapel: God came first. John Sampson, the new constable of Stirling, received a silver chalice, a vestment, two towels, a missal, a portoise, an antiphoner, a troper, and two pewter cruets.

I had to Google some of the above. A ‘portoise’ was a breviary, an antiphoner a liturgical book, and a troper a book containing tropes or sequences for the sung parts of the Mass. For their earthly needs the garrison were supplied with 67 quarters of wheat flour, 46 quarters of wheat, 51 quarters of beans, 81 quarters of barley, 143 quarters of malt, 100 large cattle and 217 sheep. For a treat, they also received a box of almonds.

Published on July 24, 2019 00:38

July 23, 2019

After the battle

The aftermath of Falkirk. After the rout of the Scottish army, Sir William Wallace escaped the field and probably took refuge in the Torwood, north-west of Falkirk. He presumably got away on the back of a horse, just like John Comyn: ever since his murder in 1306, the Red Comyn has suffered from a bad press in Scotland, and even today stands accused of betraying Wallace on the battlefield. In reality there was little he and his small band of men-at-arms could do against four massive batailles of English cavalry, and there was no sense in hanging around to be slaughtered.

The English were jubilant, their military prestige restored after the humiliation of Stirling Bridge. A popular rhyme was composed in northern England to celebrate Edward’s victory, recorded in the Chronicle of Lanercost:

Berwick, Dunbar and Falkirk too

Show all that traitor Scots can do.

England exult! Your Prince is peerless.

Where he leads us, follow fearless.

Edward himself was probably under no illusions. The king had broken Wallace’s reputation and his army, but that didn’t restore his previous hegemony over Scotland. His infantry, who were deserting in droves and suffered heavy casualties at Falkirk, were now surplus to requirements. Edward packed off the brawling, starving rabble to Carlisle and remained in Scotland with his cavalry, to try and re-establish control of Galloway and victual his castles.

The English were jubilant, their military prestige restored after the humiliation of Stirling Bridge. A popular rhyme was composed in northern England to celebrate Edward’s victory, recorded in the Chronicle of Lanercost:

Berwick, Dunbar and Falkirk too

Show all that traitor Scots can do.

England exult! Your Prince is peerless.

Where he leads us, follow fearless.

Edward himself was probably under no illusions. The king had broken Wallace’s reputation and his army, but that didn’t restore his previous hegemony over Scotland. His infantry, who were deserting in droves and suffered heavy casualties at Falkirk, were now surplus to requirements. Edward packed off the brawling, starving rabble to Carlisle and remained in Scotland with his cavalry, to try and re-establish control of Galloway and victual his castles.

Published on July 23, 2019 01:46

July 22, 2019

Dancing in the ring

The Battle of Falkirk, 22 July 1298. Instead of dancing in the ring with Edward and Wallace again, I thought it more interesting to focus on a far more obscure individual.

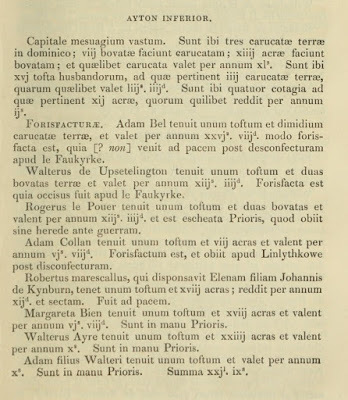

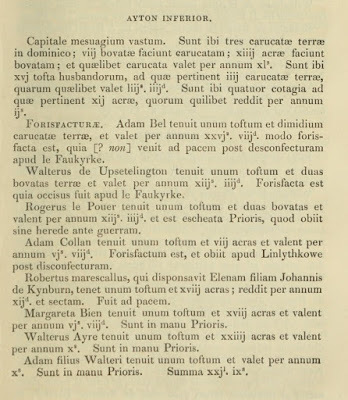

In 1306 the Prior of Durham wrote to King Edward, reminding him that many of the tenants of the barony of Coldingham had forfeited their property during the Scottish wars. Coldingham is a parish of Berwickshire on the Scottish Borders, near the southeast coastline, and home to the ruins of a medieval priory. A separate rental roll exists, which shows that as many as sixty tenants of Coldingham bore arms against the English between the submission of 1296 and August 1298. Three of them fought for Wallace at Falkirk. One, Roger le Pouer, was killed in the battle. Another, Adam Collan, survived but died shortly afterwards at Lilithgow, possibly of his wounds.

The third was Adam Bell. He held one toft and half a carucate. A toft was a house with a narrow strip of land, and a caracute a medieval unit approximating the amount of land a team of oxen could till in a single annual season. Adam, therefore, was a small landholder. He appears on the Ragman Roll of 1296, when the gentry of Scotland swore allegiance to Edward.

Coldingham Priory

Coldingham Priory

It seems Adam was still alive when his land was seized after Falkrik, and afterwards vanished. He had the same name as a famous north country outlaw, Adam Bell, who was said to haunt Inglewood Forest in Cumbria with two accomplices, William of Cloudeslee and Clym O’Clough. The oldest printed copy of this ballad dates from 1505 and the tale is probably much older. Perhaps the story was inspired by the survivor of Falkirk. Coldingham is in southeast Scotland and Inglewood Forest in Cumbria, but this isn’t a problem. In the Tudor era plenty of ‘Border Reivers’, as they were called, escaped justice by flitting back and forth across the border line. There is no reason to think their ancestors didn’t do the same. Adam may well have fled down to the English West March, and drifted into the company of a small band of thieves in Inglewood Forest.

In 1306 the Prior of Durham wrote to King Edward, reminding him that many of the tenants of the barony of Coldingham had forfeited their property during the Scottish wars. Coldingham is a parish of Berwickshire on the Scottish Borders, near the southeast coastline, and home to the ruins of a medieval priory. A separate rental roll exists, which shows that as many as sixty tenants of Coldingham bore arms against the English between the submission of 1296 and August 1298. Three of them fought for Wallace at Falkirk. One, Roger le Pouer, was killed in the battle. Another, Adam Collan, survived but died shortly afterwards at Lilithgow, possibly of his wounds.

The third was Adam Bell. He held one toft and half a carucate. A toft was a house with a narrow strip of land, and a caracute a medieval unit approximating the amount of land a team of oxen could till in a single annual season. Adam, therefore, was a small landholder. He appears on the Ragman Roll of 1296, when the gentry of Scotland swore allegiance to Edward.

Coldingham Priory

Coldingham PrioryIt seems Adam was still alive when his land was seized after Falkrik, and afterwards vanished. He had the same name as a famous north country outlaw, Adam Bell, who was said to haunt Inglewood Forest in Cumbria with two accomplices, William of Cloudeslee and Clym O’Clough. The oldest printed copy of this ballad dates from 1505 and the tale is probably much older. Perhaps the story was inspired by the survivor of Falkirk. Coldingham is in southeast Scotland and Inglewood Forest in Cumbria, but this isn’t a problem. In the Tudor era plenty of ‘Border Reivers’, as they were called, escaped justice by flitting back and forth across the border line. There is no reason to think their ancestors didn’t do the same. Adam may well have fled down to the English West March, and drifted into the company of a small band of thieves in Inglewood Forest.

Published on July 22, 2019 00:47

July 21, 2019

Wine to the infantry...or not

One of the most notorious episodes in the Falkirk campaign of 1298 was the revolt of Welsh infantry in the army of Edward I. The story goes that the army was starving at Kirkliston, west of Edinburgh, thanks to the non-arrival of supply ships from Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. When a few ships did get through, they were only carrying two hundred barrels of wine, which were then issued to Welsh soldiers. The Welsh got drunk and rioted, so Edward sent in his household knights to restore order. Eighty Welshmen were killed, along with eighteen priests who had tried to mediate.

This story comes from the quill of Walter of Guisborough, a notable fantasist when it came to Welsh affairs. The actual evidence tells a different story. In July 1298 seventeen supply ships from Yorkshire arrived at Berwick. Only five of these reached the army at Kirkliston before the battle, fought on the 22. The inventory survives for the victuals aboard these ships, and reads as follows:

63 quarters of malt, 7 meat carcasses, 250 quarters of oats, 725 quarters of wheat.

As you can see, there was no wine; certainly not 200 barrels of the stuff, to the exclusion of all else. It also doubtful that anyone would have been stupid enough to issue wine to the infantry on empty stomachs. The above supplies have been calculated as enough to feed 20,000 men for a week. The payrolls for the army present a confused picture. A comparison of numbers for the Welsh contingents in July show an overall increase from 10,260 men to 10,584, but six of these contingents lost a total of 195 men in the same period.

By the usual standards of desertion and ‘natural wastage’ in medieval armies, this wasn’t too alarming. Far more serious was the decrease in numbers among the English infantry. For the period up to 20 July infantry numbers reached a peak of 25,781. In the next 24 hours - before the battle - there was a drop of over 3000 to 22,497. It seems desertion was reaching chronic levels, and the battle occurred just in time to prevent the army falling apart.

This story comes from the quill of Walter of Guisborough, a notable fantasist when it came to Welsh affairs. The actual evidence tells a different story. In July 1298 seventeen supply ships from Yorkshire arrived at Berwick. Only five of these reached the army at Kirkliston before the battle, fought on the 22. The inventory survives for the victuals aboard these ships, and reads as follows:

63 quarters of malt, 7 meat carcasses, 250 quarters of oats, 725 quarters of wheat.

As you can see, there was no wine; certainly not 200 barrels of the stuff, to the exclusion of all else. It also doubtful that anyone would have been stupid enough to issue wine to the infantry on empty stomachs. The above supplies have been calculated as enough to feed 20,000 men for a week. The payrolls for the army present a confused picture. A comparison of numbers for the Welsh contingents in July show an overall increase from 10,260 men to 10,584, but six of these contingents lost a total of 195 men in the same period.

By the usual standards of desertion and ‘natural wastage’ in medieval armies, this wasn’t too alarming. Far more serious was the decrease in numbers among the English infantry. For the period up to 20 July infantry numbers reached a peak of 25,781. In the next 24 hours - before the battle - there was a drop of over 3000 to 22,497. It seems desertion was reaching chronic levels, and the battle occurred just in time to prevent the army falling apart.

Published on July 21, 2019 00:43