David Pilling's Blog, page 52

July 20, 2019

Burn those castles

Between 15-20 July 1298, shortly before the battle of Falkirk, the English army encamped at Kirkliston, just south of the River Forth. This was in order to receive provisions coming upriver from Berwick. At the same time Edward I sent Antony Bek, the fighting Bishop of Durham, and Sir John FitzMarmaduke to destroy the castles of Dirleton, Yester and Hailes in east Lothian.

Dirleton Castle

Dirleton Castle

Contrary winds prevented the arrival of supply ships, which mean Bek's men at Dirleton were reduced to scratching about in nearby beanfields. FitzMarmaduke was sent back to the king to explain the difficulty. What followed is one of the more entertaining exchanges of dialogue from the era.

FitzM: How are we to do this thing, lord king, since it is so very difficult?

Edward: You will do it because I say you will do it. You are an unpleasant man. I have often had to rebuke you for being too cruel, and taking too much pleasure in the destruction of your enemies. Now I say, be off, work all your dreadfulness, and I shall not blame but praise you. Take care I don't see your face again until those castles are burnt.

Sadly, it is quite possible that this convo was invented by the Yorkshire-based chronicler, Walter of Guisborough. What is certain is that the supply ships eventually arrived and the English were able to take the three castles.

Dirleton Castle

Dirleton CastleContrary winds prevented the arrival of supply ships, which mean Bek's men at Dirleton were reduced to scratching about in nearby beanfields. FitzMarmaduke was sent back to the king to explain the difficulty. What followed is one of the more entertaining exchanges of dialogue from the era.

FitzM: How are we to do this thing, lord king, since it is so very difficult?

Edward: You will do it because I say you will do it. You are an unpleasant man. I have often had to rebuke you for being too cruel, and taking too much pleasure in the destruction of your enemies. Now I say, be off, work all your dreadfulness, and I shall not blame but praise you. Take care I don't see your face again until those castles are burnt.

Sadly, it is quite possible that this convo was invented by the Yorkshire-based chronicler, Walter of Guisborough. What is certain is that the supply ships eventually arrived and the English were able to take the three castles.

Published on July 20, 2019 10:34

July 19, 2019

A glass of Champagne

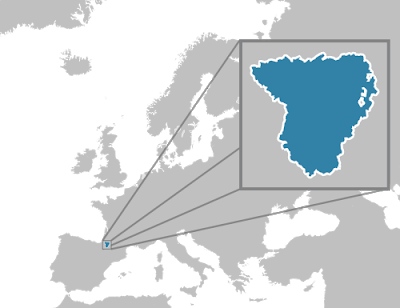

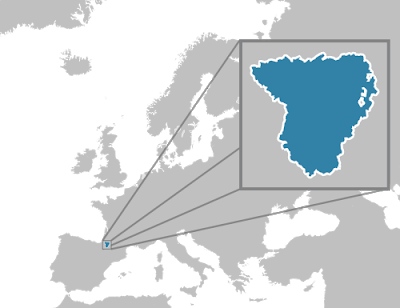

The castles of Andelot and Wassy in Champagne, north-east France. In Easter 1297 Henri III, Count of Bar, invaded Champagne on behalf of his father-in-law, Edward I of England. Henri was a member of the English king’s grand alliance against Philip le Bel, and one of the few to actually go into action against the French.

Henri did his best to make up for the failures of others. He split his army in two, the other led by his vassal, the Sire de Blémont. The count then plundered and destroyed the abbey of Beaulieu, burning the abbey, treasury and archives and carrying off sacred relics. Meanwhile his lieutenant ravaged Champagne, destroying villages and storming the aforesaid castles. Philip le Bel was busy in Flanders, so he sent his senesechal, Gercher de Cressy, at the head of an army of Champenois to counter-attack. Gercher invaded the Barrois, on the western frontier of Lorraine, and burnt the villages of Rosne, Belrain, Naives, Erize, Salmagne, Lavincourt and Culey.

This was the normal way of war, with both sides wasting the land and avoiding direct confrontation. Unusually, a battle was fought on this occasion as Gercher and Blémont’s armies clashed at Vaubécourt. Blémont was defeated and captured, and the battle remembered in French legend as the Battle of Louppy-le-Château. An engagement was fought at the same place in World War 1. A later French tradition, dating no earlier than 1579, claimed Henri himself was captured at Vaubécourt. In fact he remained at large, and ransomed his lieutenant for 2000 livres. Oddly, he borrowed the money from the Count of Hainault, who was supposed to be on the French side.

The bogus tradition has served to obscure Edward’s own military operations, since the king later gave Henri command of Welsh infantry in Flanders. Henri led the Welsh on frequent destructive raids into French territory, heaping pressure on Philip le Bel in the days leading up to the truce of Vyve-st-Baron.

Henri did his best to make up for the failures of others. He split his army in two, the other led by his vassal, the Sire de Blémont. The count then plundered and destroyed the abbey of Beaulieu, burning the abbey, treasury and archives and carrying off sacred relics. Meanwhile his lieutenant ravaged Champagne, destroying villages and storming the aforesaid castles. Philip le Bel was busy in Flanders, so he sent his senesechal, Gercher de Cressy, at the head of an army of Champenois to counter-attack. Gercher invaded the Barrois, on the western frontier of Lorraine, and burnt the villages of Rosne, Belrain, Naives, Erize, Salmagne, Lavincourt and Culey.

This was the normal way of war, with both sides wasting the land and avoiding direct confrontation. Unusually, a battle was fought on this occasion as Gercher and Blémont’s armies clashed at Vaubécourt. Blémont was defeated and captured, and the battle remembered in French legend as the Battle of Louppy-le-Château. An engagement was fought at the same place in World War 1. A later French tradition, dating no earlier than 1579, claimed Henri himself was captured at Vaubécourt. In fact he remained at large, and ransomed his lieutenant for 2000 livres. Oddly, he borrowed the money from the Count of Hainault, who was supposed to be on the French side.

The bogus tradition has served to obscure Edward’s own military operations, since the king later gave Henri command of Welsh infantry in Flanders. Henri led the Welsh on frequent destructive raids into French territory, heaping pressure on Philip le Bel in the days leading up to the truce of Vyve-st-Baron.

Published on July 19, 2019 00:54

July 18, 2019

Count Floris the unlucky

Count Floris V of Holland (1254-96). Floris’s career might be taken as a classic example of the brutal and amoral politics of this era.

Floris was just two years old when his father, Count William, was killed by the Frisians. In 1282 he defeated the Frisians in battle and succeeded in recovering his father’s body. He was supported by the Count of Hainault, an arch-enemy of the Count of Flanders of the House of Dampierre. This feud sowed the seeds of Floris’s downfall.

In 1290 Floris was lured to a meeting by Count Guy of Flanders, and imprisoned at Biervliet in Zeeland until he agreed to abandon his claims to land on the Scheldt estuary. After he was released, Floris declared war on Flanders and invaded Zeeland, but was persuaded to relent by Edward I of England. Edward wanted to recruit both Guy and Floris as allies against Philip le Bel of France, and so brokered peace between them.

In 1292 Floris got involved in the succession dispute over the vacant throne of Scotland. Via his great-great-grandmother Ada, a sister of William the Lion, he had a weak claim to the throne. Floris succeeded in delaying the proceedings for almost a year while he looked for some missing paperwork. In reality he had no interest in becoming King of Scots. He colluded with Robert de Bruce, the Competitor, who supplied Floris with two forged documents ‘proving’ the count’s claim to the throne. These were judged to be insufficient and Bruce was unable to supply originals, because there were none. The whole thing was a fraud, designed to enable Bruce to purchase the crown of Scotland from Floris in the unlikely event that Edward would support his claim. Floris simply wanted money.

The gambit failed, and Edward put John Balliol on the throne instead. Floris now played a dangerous game. In 1295 he took a bribe from the King of France to desert King Edward: his price was 4000 livres annually for life and a lump sum of 25,000 livres. He left the English camp on 9 January 1296, a fatal decision. Floris’s defection angered Edward, Count Guy, and his domestic enemies in Holland. A plot was hatched, whereby Floris would be kidnapped and smuggled over to England, where he would be given an ultimatum: return to Edward’s allegiance or surrender his title to his anglophile son, John. The kidnappers seized Floris while he was out hunting, but then panicked when some of his followers tried to rescue him. Floris was thrown into a ditch and stabbed thirty-six times. Most of his killers got away, but one was captured and tortured to death in public over a period of five hours.

The dead man’s son, John, was then married to Edward’s daughter Elizabeth of Rhuddlan. This renewed the Anglo-Dutch alliance. John, described as an ‘imbecilic runt’, appeared at the wedding at Ipswich in the company of John of Renesse, one of his father’s murderers. The new Count of Holland died in 1299, aged just fifteen, probably murdered by the Count of Hainault.

Floris was just two years old when his father, Count William, was killed by the Frisians. In 1282 he defeated the Frisians in battle and succeeded in recovering his father’s body. He was supported by the Count of Hainault, an arch-enemy of the Count of Flanders of the House of Dampierre. This feud sowed the seeds of Floris’s downfall.

In 1290 Floris was lured to a meeting by Count Guy of Flanders, and imprisoned at Biervliet in Zeeland until he agreed to abandon his claims to land on the Scheldt estuary. After he was released, Floris declared war on Flanders and invaded Zeeland, but was persuaded to relent by Edward I of England. Edward wanted to recruit both Guy and Floris as allies against Philip le Bel of France, and so brokered peace between them.

In 1292 Floris got involved in the succession dispute over the vacant throne of Scotland. Via his great-great-grandmother Ada, a sister of William the Lion, he had a weak claim to the throne. Floris succeeded in delaying the proceedings for almost a year while he looked for some missing paperwork. In reality he had no interest in becoming King of Scots. He colluded with Robert de Bruce, the Competitor, who supplied Floris with two forged documents ‘proving’ the count’s claim to the throne. These were judged to be insufficient and Bruce was unable to supply originals, because there were none. The whole thing was a fraud, designed to enable Bruce to purchase the crown of Scotland from Floris in the unlikely event that Edward would support his claim. Floris simply wanted money.

The gambit failed, and Edward put John Balliol on the throne instead. Floris now played a dangerous game. In 1295 he took a bribe from the King of France to desert King Edward: his price was 4000 livres annually for life and a lump sum of 25,000 livres. He left the English camp on 9 January 1296, a fatal decision. Floris’s defection angered Edward, Count Guy, and his domestic enemies in Holland. A plot was hatched, whereby Floris would be kidnapped and smuggled over to England, where he would be given an ultimatum: return to Edward’s allegiance or surrender his title to his anglophile son, John. The kidnappers seized Floris while he was out hunting, but then panicked when some of his followers tried to rescue him. Floris was thrown into a ditch and stabbed thirty-six times. Most of his killers got away, but one was captured and tortured to death in public over a period of five hours.

The dead man’s son, John, was then married to Edward’s daughter Elizabeth of Rhuddlan. This renewed the Anglo-Dutch alliance. John, described as an ‘imbecilic runt’, appeared at the wedding at Ipswich in the company of John of Renesse, one of his father’s murderers. The new Count of Holland died in 1299, aged just fifteen, probably murdered by the Count of Hainault.

Published on July 18, 2019 04:16

July 16, 2019

Gerald and Wales

Gerald of Wales provides a blueprint on how to conquer Wales, followed almost to the letter by Edward I a few decades later.

“How the Welsh can be conquered.

Any prince who is really determined to conquer the Welsh and to govern them in peace must proceed as follows. He should first of all understand that for a whole year at least he must devote his every effort and give his undivided attention to the task which he has undertaken. He can never hope to conquer in one single battle a people which will never draw up its forces to engage an enemy army in the field, and will never allow itself to be besieged inside fortified strong-points. He can beat them only be patient and unremitting pressure applied over a strong period. Knowing the spirit of hatred and jealousy which prevails among them, he must sow dissension in their ranks and do all he can by promises and bribes to stir them up against each other. In autumn not only the marches but certain carefully chosen localities in the interior must be fortified with castles, and these he must supply with ample provisions and garrison with families favourable to his cause. In the meantime he must make every effort to stop the Welsh buying the stocks of cloth, salt and corn which they usually import from England. Ships manned with picked troops must patrol the coast, to make sure that these goods are not brought by water across the Irish Sea or the Severn Sea, to ward off enemy attacks and to secure his own supply-lines. Later on, when wintry conditions have really set in, or perhaps towards the end of winter, in February and March, by which time the trees have lost their leaves, and there is no more pasturage to be had in the mountains, a strong force of infantry must have the courage to invade their secret strongholds, which lie deep in the woods and are buried in the forests. They must be cut off from all opportunity of foraging, and harassed, both individual families and larger assemblies of troops, by frequent attacks from those encamped around. The assault troops must be lightly armed and not weighed down with a lot of equipment. They must be strengthened with frequent reinforcements, who have been following close behind to give them support and to provide a base. Fresh troops must keep on replacing those who are tired out, and maybe those have been killed in battle. If he constantly moves up new men, there need be no break in the assault. Without them this belligerent people will never be conquered, and even so the danger will be great and many casualties must be expected.”

All of this has a remarkable similarity to Edward’s strategy in Wales, with one key difference. The policy of the Llywelyns, after Gerald’s day, was to try and ‘modernise’ the Welsh state. This involved building castles. The Welsh could now be bottled up inside conventional strong-points, which was the kind of warfare the Anglo-Normans understood. The sieges of Dolforwyn (1277) and Castell y Bere (1283) fatally undermined Welsh resistance.

“How the Welsh can be conquered.

Any prince who is really determined to conquer the Welsh and to govern them in peace must proceed as follows. He should first of all understand that for a whole year at least he must devote his every effort and give his undivided attention to the task which he has undertaken. He can never hope to conquer in one single battle a people which will never draw up its forces to engage an enemy army in the field, and will never allow itself to be besieged inside fortified strong-points. He can beat them only be patient and unremitting pressure applied over a strong period. Knowing the spirit of hatred and jealousy which prevails among them, he must sow dissension in their ranks and do all he can by promises and bribes to stir them up against each other. In autumn not only the marches but certain carefully chosen localities in the interior must be fortified with castles, and these he must supply with ample provisions and garrison with families favourable to his cause. In the meantime he must make every effort to stop the Welsh buying the stocks of cloth, salt and corn which they usually import from England. Ships manned with picked troops must patrol the coast, to make sure that these goods are not brought by water across the Irish Sea or the Severn Sea, to ward off enemy attacks and to secure his own supply-lines. Later on, when wintry conditions have really set in, or perhaps towards the end of winter, in February and March, by which time the trees have lost their leaves, and there is no more pasturage to be had in the mountains, a strong force of infantry must have the courage to invade their secret strongholds, which lie deep in the woods and are buried in the forests. They must be cut off from all opportunity of foraging, and harassed, both individual families and larger assemblies of troops, by frequent attacks from those encamped around. The assault troops must be lightly armed and not weighed down with a lot of equipment. They must be strengthened with frequent reinforcements, who have been following close behind to give them support and to provide a base. Fresh troops must keep on replacing those who are tired out, and maybe those have been killed in battle. If he constantly moves up new men, there need be no break in the assault. Without them this belligerent people will never be conquered, and even so the danger will be great and many casualties must be expected.”

All of this has a remarkable similarity to Edward’s strategy in Wales, with one key difference. The policy of the Llywelyns, after Gerald’s day, was to try and ‘modernise’ the Welsh state. This involved building castles. The Welsh could now be bottled up inside conventional strong-points, which was the kind of warfare the Anglo-Normans understood. The sieges of Dolforwyn (1277) and Castell y Bere (1283) fatally undermined Welsh resistance.

Published on July 16, 2019 01:38

July 15, 2019

Crusader contracts

By the time he sailed for the Holy Land in 1270, the Lord Edward had secured the promise of at least seventeen barons of England and Brittany to “go with him to the Holy Land, and to remain in his service for a whole year to commence at the coming voyage.”

The prince agreed in return to provide them with water and transport as far as the theatre of military operations. The barons were accompanied by their knights. To judge from surviving contracts, the total number of men committed was 105, though some contracts may have been lost or destroyed. One of these agreements, for a baron of Northumberland named Adam Gesemue, reads:

“Know that I have agreed with the Lord Edward, to go with him to the Holy Land, accompanied by five knights, and to remain in his service for a whole year to commence at the coming voyage in September. And in return he has given me, to cover all expenses, 600 marks and money and transport - that is to say the hire of a ship and water for as many persons and horses as are appropriate for knights.”

Edward in turn was obliged to serve under the King of France, Saint Louis, “in the same way as any of other barons”. He retained full jurisdiction over his own followers. Any offences committed by English or Breton crusaders travelling through the lands of Christian princes or against other crusaders in North Africa were to be tried by Edward, who was also responsible for punishment.

The prince agreed in return to provide them with water and transport as far as the theatre of military operations. The barons were accompanied by their knights. To judge from surviving contracts, the total number of men committed was 105, though some contracts may have been lost or destroyed. One of these agreements, for a baron of Northumberland named Adam Gesemue, reads:

“Know that I have agreed with the Lord Edward, to go with him to the Holy Land, accompanied by five knights, and to remain in his service for a whole year to commence at the coming voyage in September. And in return he has given me, to cover all expenses, 600 marks and money and transport - that is to say the hire of a ship and water for as many persons and horses as are appropriate for knights.”

Edward in turn was obliged to serve under the King of France, Saint Louis, “in the same way as any of other barons”. He retained full jurisdiction over his own followers. Any offences committed by English or Breton crusaders travelling through the lands of Christian princes or against other crusaders in North Africa were to be tried by Edward, who was also responsible for punishment.

Published on July 15, 2019 04:08

July 14, 2019

Edward and Llywelyn

“Nor did they [the Welsh] wish to obey Lord Edward, the son of the king, but they laughed boisterously and heaped scorn upon him. And so consequently Edward put forward the idea that he should give up these Welshmen as unconquerable.”

- Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora [v]

Edward allegedly said this in 1257, after the destruction of his army at Cymerau and the failure of his father’s campaign in North Wales. Paris despised Edward, so you can’t take his word as gospel, but the entry may reflect something of the prince’s attitude towards the Welsh. In 1265 he deliberately abandoned some of his land interests in Wales and granted the lordships of Carmarthen and Cardigan to his brother, Edmund, who also received the Three Castles. Two years later, via the Treaty of Montgomery, the Four Cantreds in the north were formally conceded to Prince Llywelyn. Edward’s vast appanage in Wales, granted to him in 1254, was wiped out. Edward probably had little say in the treaty, but must have known what was coming.

He went further. The Treaty of Montgomery had conceded to Llywelyn the homage and fealty of all the lords of Wales except Maredudd ap Rhys, lord of Ystrad Tywi and grandson of the Lord Rhys. Edward repeatedly asked his father, Henry III, to permit Llywelyn to buy Maredudd’s homage, which had been granted to Edmund. At last Henry gave way and allowed Llywelyn to purchase Maredudd for the sum of 5000 marks. This sum was never paid over and added to Llywelyn’s growing mountain of debts. Edward also went to the Marches in person to grant Llywelyn the homage and fealty of Maredudd ap Gruffudd, a lord of Glamorgan. This further strengthened Llywelyn’s grip on the principality, and at the expense of the Earl of Gloucester, the greatest of Marcher lords.

Paris’s claim that Edward wished to give up Wales to the Welsh was in fact an understatement. In these years Edward not only surrendered his own land interests in the principality, but actively worked to bolster the power of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. No wonder the Welsh prince wrote to Henry III, expressing ‘delight’ at his negotiations with Edward in the summer of 1269.

- Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora [v]

Edward allegedly said this in 1257, after the destruction of his army at Cymerau and the failure of his father’s campaign in North Wales. Paris despised Edward, so you can’t take his word as gospel, but the entry may reflect something of the prince’s attitude towards the Welsh. In 1265 he deliberately abandoned some of his land interests in Wales and granted the lordships of Carmarthen and Cardigan to his brother, Edmund, who also received the Three Castles. Two years later, via the Treaty of Montgomery, the Four Cantreds in the north were formally conceded to Prince Llywelyn. Edward’s vast appanage in Wales, granted to him in 1254, was wiped out. Edward probably had little say in the treaty, but must have known what was coming.

He went further. The Treaty of Montgomery had conceded to Llywelyn the homage and fealty of all the lords of Wales except Maredudd ap Rhys, lord of Ystrad Tywi and grandson of the Lord Rhys. Edward repeatedly asked his father, Henry III, to permit Llywelyn to buy Maredudd’s homage, which had been granted to Edmund. At last Henry gave way and allowed Llywelyn to purchase Maredudd for the sum of 5000 marks. This sum was never paid over and added to Llywelyn’s growing mountain of debts. Edward also went to the Marches in person to grant Llywelyn the homage and fealty of Maredudd ap Gruffudd, a lord of Glamorgan. This further strengthened Llywelyn’s grip on the principality, and at the expense of the Earl of Gloucester, the greatest of Marcher lords.

Paris’s claim that Edward wished to give up Wales to the Welsh was in fact an understatement. In these years Edward not only surrendered his own land interests in the principality, but actively worked to bolster the power of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. No wonder the Welsh prince wrote to Henry III, expressing ‘delight’ at his negotiations with Edward in the summer of 1269.

Published on July 14, 2019 01:42

July 13, 2019

Gaston the unreliable

Apart from recruitment in England, the Lord Edward was also keen to enlist Gascons for his crusade. He also wanted to ensure the security of the duchy while he was away: since his appanage in Wales had been wiped out, Gascony was at this point his most prized possession. Perhaps it always was, even though England had to come first.

Thanks to the help of King Louis, Edward managed to persuade Gaston, viscomte of Béarn, to join the expedition in August for the fee of 25,000 livres tournois. Gaston, lord of Béarn on the Pyrenean frontier, was a pain in the butt: he had torn up Gascony while Simon de Montfort was seneschal of the duchy, and never ceased raiding, plundering and complaining. Having him along on the crusade was a way of ensuring he didn’t set fire to Gascony while Edward was in the Holy Land. Edward attempted to strengthen Gaston’s future allegiance by arranging a marriage for the viscomte’s daughter, Constance, and Edward’s cousin Henry of Almaine. Henry was the heir of Richard of Cornwall, Henry III’s brother and King of the Romans as well as Earl of Cornwall. This was quite a match for Gaston, who was a big noise in Gascony but a mere squeak outside it.

Gaston was happy to profit from a political marriage, but thought better of risking his neck in Outremer. Despite French influence and financial incentives, in the end he decided to stay at home and make himself useful by arguing with Edward’s officers. This meant he lost his share of the 75,000 livres granted by Louis to Edward and Gaston, so the English prince kept the cash and carried on alone to the Holy Land.

Above are the arms of Gaston IV, Gaston’s ancestor, who did go to the Holy Land in 1096 and made a great name for himself killing some people in the desert he had never met.

Thanks to the help of King Louis, Edward managed to persuade Gaston, viscomte of Béarn, to join the expedition in August for the fee of 25,000 livres tournois. Gaston, lord of Béarn on the Pyrenean frontier, was a pain in the butt: he had torn up Gascony while Simon de Montfort was seneschal of the duchy, and never ceased raiding, plundering and complaining. Having him along on the crusade was a way of ensuring he didn’t set fire to Gascony while Edward was in the Holy Land. Edward attempted to strengthen Gaston’s future allegiance by arranging a marriage for the viscomte’s daughter, Constance, and Edward’s cousin Henry of Almaine. Henry was the heir of Richard of Cornwall, Henry III’s brother and King of the Romans as well as Earl of Cornwall. This was quite a match for Gaston, who was a big noise in Gascony but a mere squeak outside it.

Gaston was happy to profit from a political marriage, but thought better of risking his neck in Outremer. Despite French influence and financial incentives, in the end he decided to stay at home and make himself useful by arguing with Edward’s officers. This meant he lost his share of the 75,000 livres granted by Louis to Edward and Gaston, so the English prince kept the cash and carried on alone to the Holy Land.

Above are the arms of Gaston IV, Gaston’s ancestor, who did go to the Holy Land in 1096 and made a great name for himself killing some people in the desert he had never met.

Published on July 13, 2019 06:39

July 11, 2019

Edward and Gilbert

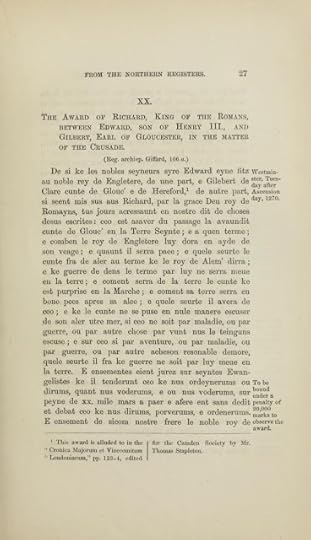

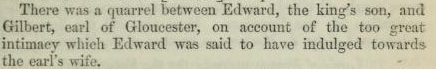

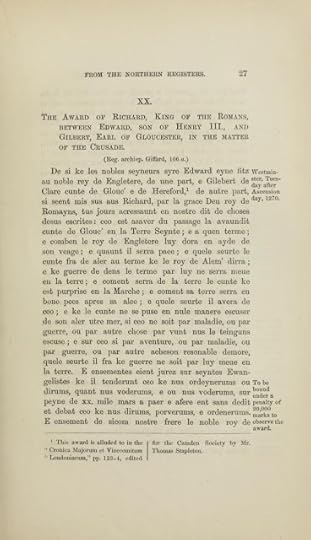

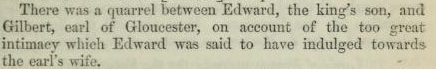

The most important English leader whom the Lord Edward tried to enlist for his crusade was Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester. How much Edward really wanted him along, despite Clare’s power and importance, is a moot point. Clare had taken the cross at Northampton in 1268, but afterwards his personal relations with the heir to the throne soured again. They had worked together to destroy Simon de Montfort, but it seems fairly clear the two struggled to get along.

Gilbert de Clare

Gilbert de Clare

Instead of courting the earl’s support, Edward went out of his way to antagonise him. In the summer of 1268 rumours swirled about the March, Clare’s power base, that Edward was paying too much attention to Clare’s wife, Alice de Lusignan. This was probably just gossip, but the prince took more serious steps to undermine Clare’s power.

In 1269, at the request of Prince Llywelyn, Edward came in person to the Marches and granted Llywelyn the homage and fealty of Maredudd ap Gruffudd, lord of Gwynllwg and Caerleon and one of Clare’s tenants. Maredudd was a descendant of the ancient princes of Deheuabarth, but his ancestors had lost most of their territories. Shortly before 1269, Llywelyn granted Maredudd the commote of Hirfryn in Ystrad Tywi. Llywelyn then claimed that Maredudd was a Welsh baron and ought to hold his lands as tenant-in-chief of the Prince of Wales. This was granted by Edward at the ford of Montgomery. Llywelyn was poised to attack Clare’s lands in Glamorgan and Gwent, so at this point Edward and Llywelyn formed a tag-team against the earl.

Clare went into a sulk and refused to attend a council in London, saying Edward ‘wished him ill’. He also refused to attend a conference in Paris to discuss the crusade in August, though it isn’t clear whether he was even invited. In February 1270 he went to Paris under his steam to meet with King Louis, only to return having rejected all of the French king’s proposals. He then refused to attend yet another parliament, and said he wouldn’t turn up unless letters of safe-conduct were granted to him and his men.

At last Edward’s uncle, Richard of Cornwall, intervened to heal the breach between his nephew and Clare. He brokered a remarkable agreement, whereby Clare was promised 2000 marks upon his departure from England to the Holy Land. This sum would be increased to 8000 marks if he personally accompanied Edward instead of going independently. The prince’s obligation was to pay the sums described and leave before September 1270. As extra insurance, both parties were to pay the massive sum of 20,000 marks if they broke the agreement, and Clare would have to surrender his castles of Tonbridge and Henley. These would be returned to him when it was known ‘he was on the Greek Sea’. In his absence the earl’s lands would have royal protection, and a threat of excommunication was added by the bishops in a separate document. It seems nobody had much confidence in this deal.

For good reason. After more rejections and arguments, Clare finally accepted the agreement on 127 June. In August he returned to the March to make preparations for departure - that, however, was the closest Clare ever got to the Holy Land. He refused to shift from his lands, and when the expedition finally left he wasn’t part of it. Richard of Cornwall’s contract proved so much worthless parchment, as Clare was never penalised for his failure to go East.

Gilbert de Clare

Gilbert de ClareInstead of courting the earl’s support, Edward went out of his way to antagonise him. In the summer of 1268 rumours swirled about the March, Clare’s power base, that Edward was paying too much attention to Clare’s wife, Alice de Lusignan. This was probably just gossip, but the prince took more serious steps to undermine Clare’s power.

In 1269, at the request of Prince Llywelyn, Edward came in person to the Marches and granted Llywelyn the homage and fealty of Maredudd ap Gruffudd, lord of Gwynllwg and Caerleon and one of Clare’s tenants. Maredudd was a descendant of the ancient princes of Deheuabarth, but his ancestors had lost most of their territories. Shortly before 1269, Llywelyn granted Maredudd the commote of Hirfryn in Ystrad Tywi. Llywelyn then claimed that Maredudd was a Welsh baron and ought to hold his lands as tenant-in-chief of the Prince of Wales. This was granted by Edward at the ford of Montgomery. Llywelyn was poised to attack Clare’s lands in Glamorgan and Gwent, so at this point Edward and Llywelyn formed a tag-team against the earl.

Clare went into a sulk and refused to attend a council in London, saying Edward ‘wished him ill’. He also refused to attend a conference in Paris to discuss the crusade in August, though it isn’t clear whether he was even invited. In February 1270 he went to Paris under his steam to meet with King Louis, only to return having rejected all of the French king’s proposals. He then refused to attend yet another parliament, and said he wouldn’t turn up unless letters of safe-conduct were granted to him and his men.

At last Edward’s uncle, Richard of Cornwall, intervened to heal the breach between his nephew and Clare. He brokered a remarkable agreement, whereby Clare was promised 2000 marks upon his departure from England to the Holy Land. This sum would be increased to 8000 marks if he personally accompanied Edward instead of going independently. The prince’s obligation was to pay the sums described and leave before September 1270. As extra insurance, both parties were to pay the massive sum of 20,000 marks if they broke the agreement, and Clare would have to surrender his castles of Tonbridge and Henley. These would be returned to him when it was known ‘he was on the Greek Sea’. In his absence the earl’s lands would have royal protection, and a threat of excommunication was added by the bishops in a separate document. It seems nobody had much confidence in this deal.

For good reason. After more rejections and arguments, Clare finally accepted the agreement on 127 June. In August he returned to the March to make preparations for departure - that, however, was the closest Clare ever got to the Holy Land. He refused to shift from his lands, and when the expedition finally left he wasn’t part of it. Richard of Cornwall’s contract proved so much worthless parchment, as Clare was never penalised for his failure to go East.

Published on July 11, 2019 06:45

July 10, 2019

Thomas the traitor

Some proper history-meat. Attached is an entry from the second continuum of the Chronicle of Florence of Worcester. Florence died in 1118 but his work was completed by two successive scribes. The second continuum is the work of an anonymous monk of the abbey of Bury St Edmunds.

The entry concerns Thomas de Turberville, once a household knight of Edward I. In 1295 he was captured by the French at Rions, and agreed to defect to Philip IV. He returned to England and set about trying to arrange a simultaneous uprising against Edward in Wales and Scotland, which would coincide with a French invasion of England. As a reward, Philip allegedly promised Turberville the principality of Wales for himself and his heirs.

The entry doesn’t actually say that Turberville claimed the principality, rather he was offered it by the French. The question is whether Turberville had some kind of blood link to the Welsh princes. He was probably a member of the Turbervilles of Crickhowell, a Marcher family. There may have been some mixed ancestry, since by the thirteenth century that was the norm on the March. Exactly what, I don’t know.

In his letters to the French, intercepted by Edward’s agents, Turberville claimed to have a contact in Glamorgan named Morgan. Morgan, he wrote, had promised to raise the Welsh against Edward when the French landed. This must have been Morgan ap Maredudd, the only Welsh landholder in Glamorgan with the power and status to raise an army of Welshmen. The exact words of the letter are:

“And know that we think that we have enough to do against those of Scotland; and if those of Scotland rise against the King of England, the Welsh will rise also. And this I have well contrived, and Morgan has fully covenanted with me to that effect.”

It seems Turberville was duped: accounts in the British Library show that Morgan was on the English king’s payroll as a spy and agent provocateur. He may have been employed in this role for decades. Morgan was among the last of Dafydd ap Gruffudd’s supporters in 1283, and unlike the rest escaped any form of punishment. In September 1295, after Thomas was arrested and delivered up to Edward’s inquisitors, Morgan again got off scot-free.

The entry concerns Thomas de Turberville, once a household knight of Edward I. In 1295 he was captured by the French at Rions, and agreed to defect to Philip IV. He returned to England and set about trying to arrange a simultaneous uprising against Edward in Wales and Scotland, which would coincide with a French invasion of England. As a reward, Philip allegedly promised Turberville the principality of Wales for himself and his heirs.

The entry doesn’t actually say that Turberville claimed the principality, rather he was offered it by the French. The question is whether Turberville had some kind of blood link to the Welsh princes. He was probably a member of the Turbervilles of Crickhowell, a Marcher family. There may have been some mixed ancestry, since by the thirteenth century that was the norm on the March. Exactly what, I don’t know.

In his letters to the French, intercepted by Edward’s agents, Turberville claimed to have a contact in Glamorgan named Morgan. Morgan, he wrote, had promised to raise the Welsh against Edward when the French landed. This must have been Morgan ap Maredudd, the only Welsh landholder in Glamorgan with the power and status to raise an army of Welshmen. The exact words of the letter are:

“And know that we think that we have enough to do against those of Scotland; and if those of Scotland rise against the King of England, the Welsh will rise also. And this I have well contrived, and Morgan has fully covenanted with me to that effect.”

It seems Turberville was duped: accounts in the British Library show that Morgan was on the English king’s payroll as a spy and agent provocateur. He may have been employed in this role for decades. Morgan was among the last of Dafydd ap Gruffudd’s supporters in 1283, and unlike the rest escaped any form of punishment. In September 1295, after Thomas was arrested and delivered up to Edward’s inquisitors, Morgan again got off scot-free.

Published on July 10, 2019 04:48

July 8, 2019

The woes of Henry IV

The start of Henry IV of England's malady, unpleasant details taken from Chris Given-Wilson's biography.

In April 1405 the king's health suddenly collapsed. Early on the morning of the 28, he wrote from his lodge in Windsor Great Park that 'an illness has suddenly affected us in our leg'. He was in such pain that his physicians told him not to ride, and a few days later the condition worsened.

According to a medical treatise by John Arderne, Treatise of Fistula in Ano, Henry suffered from a prolapsed rectum. The remedy advocated by Arderne recommended first bleeding the leg before applying an ointment called 'the green ointment of the Twelve Apostles'. The principal ingredients were white wax, pine resin, aristolochia, incense, mastic, opoponax, myrrh, galbanum and litharge. When this was heated and applied to the prolapsed area, 'it schal entre agayn', whereupon it was dressed to prevent it protruding once more. If necessary, the procedure could be repeated several times.

Arderne had died in 1376, shortly after writing his treatise, but a post-1413 translator of the work added in the margin 'With this medicine was King Henry of England cured of the going out of the lure' (prolapsed rectum).

In April 1405 the king's health suddenly collapsed. Early on the morning of the 28, he wrote from his lodge in Windsor Great Park that 'an illness has suddenly affected us in our leg'. He was in such pain that his physicians told him not to ride, and a few days later the condition worsened.

According to a medical treatise by John Arderne, Treatise of Fistula in Ano, Henry suffered from a prolapsed rectum. The remedy advocated by Arderne recommended first bleeding the leg before applying an ointment called 'the green ointment of the Twelve Apostles'. The principal ingredients were white wax, pine resin, aristolochia, incense, mastic, opoponax, myrrh, galbanum and litharge. When this was heated and applied to the prolapsed area, 'it schal entre agayn', whereupon it was dressed to prevent it protruding once more. If necessary, the procedure could be repeated several times.

Arderne had died in 1376, shortly after writing his treatise, but a post-1413 translator of the work added in the margin 'With this medicine was King Henry of England cured of the going out of the lure' (prolapsed rectum).

Published on July 08, 2019 03:25