David Pilling's Blog, page 55

June 23, 2019

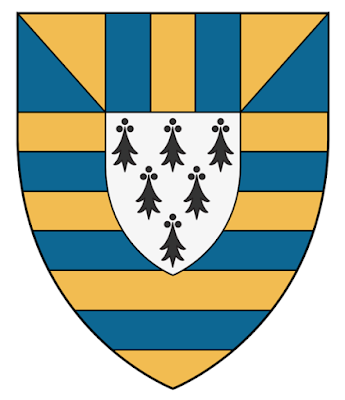

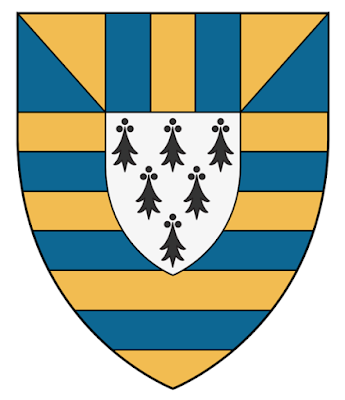

Marmaduke of the parrots

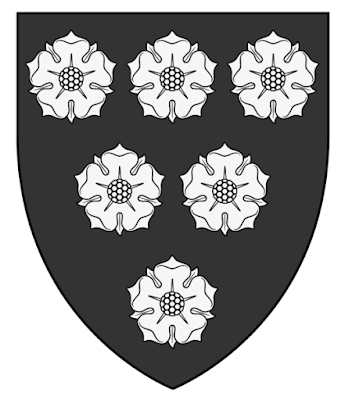

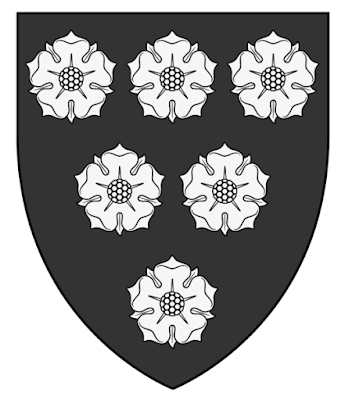

The arms of Marmaduke de Thweng, 1st Baron Thweng, an English knight of Yorkshire. Apart from his wonderful name, Marmaduke also sported three green parrots on his shield, making him an even more wonderful.

Marmaduke was a kinsman of the Bruces and an example of cross-border links among the English and Scottish nobility. His mother was Lucy de Bruce of Kilton, a descendent of Adam de Brus, lord of Skelton and brother to Robert de Bruce, 1st lord of Annandale. Marmaduke was a vassal of his kinsman Robert de Bruce, father of the victor of Bannockburn, by virtue of the latter's fiefdom in the North Riding.

Marmaduke fought at the Battle of Stirling Bridge, where his heroic behaviour was the only bright spot in a day of shame and disaster for the English. He rode with the vanguard across the bridge, where the English cavalry were trapped and slaughtered as they tried to deploy in boggy ground. Marmaduke's son was killed in the fight. His father threw the young man's body over his saddle, cut his way out of the mess and swam his horse across the river. Once on the other side, he advised Earl Warenne to break down the bridge and withdraw, which was done. After the rout, Marmaduke was appointed one of the two English castellans of Stirling Castle. The English were quickly starved out and Marmaduke taken off to captivity at Dumbarton, though he was released in time to serve at Falkirk. At the battle he fought in the Bishop of Durham's bataille and would have been involved in the initial charge against the Scottish schiltrons.

In 1314 Marmaduke had the misfortune to fight for the English at Bannockburn. After the destruction of Edward II's army he spent the night in a hedge, and the following morning wandered about the battlefield in his nightshirt, looking for someone to surrender to. He and Ralph de Monthermer, another English baron, were entertained to breakfast by Bruce before being released without ransom. Marmaduke was clearly a competent and chivalrous character, well-respected by the leading lights on both sides of the border.

Not being an effeminate, cackling psychopath with a taste for legalised rape, he doesn't appear among the English characters in Braveheart.

Marmaduke was a kinsman of the Bruces and an example of cross-border links among the English and Scottish nobility. His mother was Lucy de Bruce of Kilton, a descendent of Adam de Brus, lord of Skelton and brother to Robert de Bruce, 1st lord of Annandale. Marmaduke was a vassal of his kinsman Robert de Bruce, father of the victor of Bannockburn, by virtue of the latter's fiefdom in the North Riding.

Marmaduke fought at the Battle of Stirling Bridge, where his heroic behaviour was the only bright spot in a day of shame and disaster for the English. He rode with the vanguard across the bridge, where the English cavalry were trapped and slaughtered as they tried to deploy in boggy ground. Marmaduke's son was killed in the fight. His father threw the young man's body over his saddle, cut his way out of the mess and swam his horse across the river. Once on the other side, he advised Earl Warenne to break down the bridge and withdraw, which was done. After the rout, Marmaduke was appointed one of the two English castellans of Stirling Castle. The English were quickly starved out and Marmaduke taken off to captivity at Dumbarton, though he was released in time to serve at Falkirk. At the battle he fought in the Bishop of Durham's bataille and would have been involved in the initial charge against the Scottish schiltrons.

In 1314 Marmaduke had the misfortune to fight for the English at Bannockburn. After the destruction of Edward II's army he spent the night in a hedge, and the following morning wandered about the battlefield in his nightshirt, looking for someone to surrender to. He and Ralph de Monthermer, another English baron, were entertained to breakfast by Bruce before being released without ransom. Marmaduke was clearly a competent and chivalrous character, well-respected by the leading lights on both sides of the border.

Not being an effeminate, cackling psychopath with a taste for legalised rape, he doesn't appear among the English characters in Braveheart.

Published on June 23, 2019 10:44

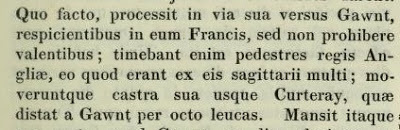

Longbows strongbows

“For they feared the English king's infantry because amongst them were many archers.” Walter of Heminburgh, describing Edward I’s march from Bruges to Ghent in 1297. The flanks of the king’s little army were allegedly ‘bare of troops’, but the French refused to attack due to their fear of his archers.

This might be an early reference to Welsh archers armed with the longbow or war bow (or mega-bow, whatever). All of Edward’s infantry at this stage of the Flanders campaign were Welsh, recruited largely from Gwynedd and Glamorgan. Contemporary sketches of Welsh soldiers (see below) show them armed with short bows, though it is difficult to see why armoured French knights should have baulked at charging men armed with ordinary missile weapons. It would seem Gerald of Wales’s description of 12th Welsh archers armed with bows of dwarf elm, rough and unpolished, yet capable of pinning knights to their saddles, has some foundation after all.

There is also the evidence from the siege of Dryslwyn in 1287. One contemporary account of the siege describes an arrow from a Welsh archer shot with such force that it drilled clean through the head of an English soldier. Modern excavations at Dryslwyn and elsewhere have found plenty of arrowheads that would have been launched from ‘true longbows’. Dr Chris Caple, in charge of the digs, answered my query thus:

“Yes these arrowhead were from longbows, the longest arrowhead with socket being over 16cm in length – the bows launching these arrowheads were effectively true longbows. Olly Jessop (who wrote the typology of medieval arrowheads) wrote the specialist report for us (reference below). There is plenty of evidence for similar arrowheads from other castles such as Criccieth in Wales. Our examples are perhaps a little better dated than other given the modern excavation standards at Dryslwyn. The problems are always to do with words – terms such as war bow, longbow etc mean different things to different authors. The best and most telling evidence is from archaeology.”

None of the above, however, supports the popular view of Wallace’s spearmen being shot to bits by longbows at the battle of Falkirk. Most chronicle accounts agree the Welsh refused to fight at Falkirk until the closing stages. Therefore the schiltrons must have been broken up by other means, and there is no evidence of English troops using longbows at this stage.

This might be an early reference to Welsh archers armed with the longbow or war bow (or mega-bow, whatever). All of Edward’s infantry at this stage of the Flanders campaign were Welsh, recruited largely from Gwynedd and Glamorgan. Contemporary sketches of Welsh soldiers (see below) show them armed with short bows, though it is difficult to see why armoured French knights should have baulked at charging men armed with ordinary missile weapons. It would seem Gerald of Wales’s description of 12th Welsh archers armed with bows of dwarf elm, rough and unpolished, yet capable of pinning knights to their saddles, has some foundation after all.

There is also the evidence from the siege of Dryslwyn in 1287. One contemporary account of the siege describes an arrow from a Welsh archer shot with such force that it drilled clean through the head of an English soldier. Modern excavations at Dryslwyn and elsewhere have found plenty of arrowheads that would have been launched from ‘true longbows’. Dr Chris Caple, in charge of the digs, answered my query thus:

“Yes these arrowhead were from longbows, the longest arrowhead with socket being over 16cm in length – the bows launching these arrowheads were effectively true longbows. Olly Jessop (who wrote the typology of medieval arrowheads) wrote the specialist report for us (reference below). There is plenty of evidence for similar arrowheads from other castles such as Criccieth in Wales. Our examples are perhaps a little better dated than other given the modern excavation standards at Dryslwyn. The problems are always to do with words – terms such as war bow, longbow etc mean different things to different authors. The best and most telling evidence is from archaeology.”

None of the above, however, supports the popular view of Wallace’s spearmen being shot to bits by longbows at the battle of Falkirk. Most chronicle accounts agree the Welsh refused to fight at Falkirk until the closing stages. Therefore the schiltrons must have been broken up by other means, and there is no evidence of English troops using longbows at this stage.

Published on June 23, 2019 04:26

June 22, 2019

Horsey and Brucey

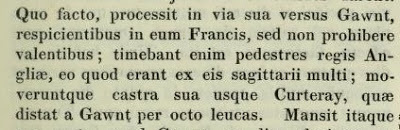

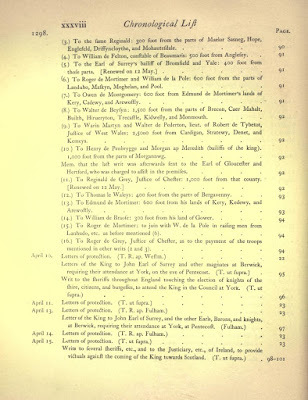

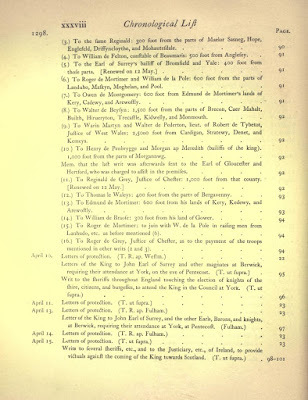

Two letters, just a few days before the disagreement at Falkirk. On the first, dated 29 June 1298, Edward I orders the sheriff of Northumberland to receive the king's horse from Adam Riston, who served a dual role as captain of the royal bodyguard and master of horse.

Horsey was to be kept in the castle of Newcastle-upon-Tyne and fed daily on oats, bran and 'other things needful'. In the second, dated 3 July, Robert de Bruce earl of Carrick and lord of Annadale informs the chancellor of England that he will do 'anything' the chancellor requires of him. In addition he has despatched three of his knights to join King Edward in Galloway. This is Bruce senior, father of the future victor of Bannockburn.

Horsey was to be kept in the castle of Newcastle-upon-Tyne and fed daily on oats, bran and 'other things needful'. In the second, dated 3 July, Robert de Bruce earl of Carrick and lord of Annadale informs the chancellor of England that he will do 'anything' the chancellor requires of him. In addition he has despatched three of his knights to join King Edward in Galloway. This is Bruce senior, father of the future victor of Bannockburn.

Published on June 22, 2019 00:46

June 21, 2019

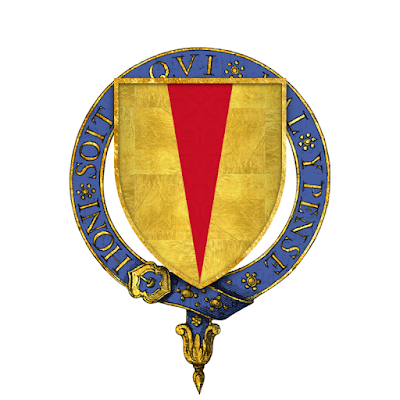

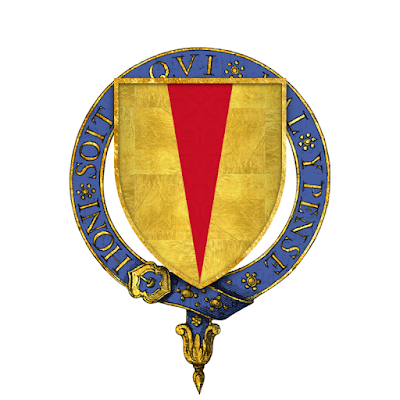

Plain red bunting

The not very flamboyant arms of Amanieu VII d'Albret, another Gascon exile in English service at Falkirk.

Amanieu was the head of the Albret, one of the oldest families of Plantagenet Aquitaine. Stemming from the poor and insignificant lordship of Labrit, they steadily built up their holdings via marriage and purchase. Both Henry III and Edward I were careful to cultivate the loyalty of the Albret, now one of the most powerful Gascon lineages in the northern part of the duchy. The Albret in turn held true to the Plantagenets: Amanieu VII was especially loyal and served Edward in France and Scotland. He is briefly mentioned in the Song of Caerlaverock, otherwise a praise piece for English knights.

The loyalty of the Albret, so painstakingly built up over decades, was thrown to the winds by Edward II. Edward chose to favour the Gaveston faction, Amanieu VII's hereditary enemies. In 1310 Amanieu was expelled from his lordship of Nérac by Piers Gaveston's older brother, and appealed to Philip le Bel for justice. In his appeal Amanieu complained the Gavestons were conspiring to compromise Edward II's honour by giving away Gascon lands and offices to unsuitable candidates. Edward's response was to appoint John de Ferrers as seneschal of Gascony: John murdered several of Amanieu's kinsmen and had others arrested and mutilated. Amanieu raised an army against the seneschal and was probably responsible for his poisoning in 1312. This once-loyal supporter of the Plantagenet regime then defected to the French.

At Falkirk Amanieu seems to have fought all on his lonesome, holding his plain red flag.

Amanieu was the head of the Albret, one of the oldest families of Plantagenet Aquitaine. Stemming from the poor and insignificant lordship of Labrit, they steadily built up their holdings via marriage and purchase. Both Henry III and Edward I were careful to cultivate the loyalty of the Albret, now one of the most powerful Gascon lineages in the northern part of the duchy. The Albret in turn held true to the Plantagenets: Amanieu VII was especially loyal and served Edward in France and Scotland. He is briefly mentioned in the Song of Caerlaverock, otherwise a praise piece for English knights.

The loyalty of the Albret, so painstakingly built up over decades, was thrown to the winds by Edward II. Edward chose to favour the Gaveston faction, Amanieu VII's hereditary enemies. In 1310 Amanieu was expelled from his lordship of Nérac by Piers Gaveston's older brother, and appealed to Philip le Bel for justice. In his appeal Amanieu complained the Gavestons were conspiring to compromise Edward II's honour by giving away Gascon lands and offices to unsuitable candidates. Edward's response was to appoint John de Ferrers as seneschal of Gascony: John murdered several of Amanieu's kinsmen and had others arrested and mutilated. Amanieu raised an army against the seneschal and was probably responsible for his poisoning in 1312. This once-loyal supporter of the Plantagenet regime then defected to the French.

At Falkirk Amanieu seems to have fought all on his lonesome, holding his plain red flag.

Published on June 21, 2019 08:26

Pons de Castillon

The arms of Pons de Castillon. Pons was one of the many lords of Gascony who fled into exile in England when the French invaded the duchy in 1294. This lent King Edward a handy pool of extra fighting men, who were then thrown into service in Flanders and Scotland.

At the battle of Falkirk Pons led a conroi of seventeen Gascon knights and sergeants and one rather incongruous Welshman, John de Galeys. Of these, twelve lost their horses in the battle. Since Pons served in the king's bataille, this can only mean the king's own battalion had to go into action, implying Falkirk was an even more desperately fought action that previously thought.

After the shattering French defeat at Courtrai in 1302, Pons was one of 112 Gascon exiles who sailed home from Portsmouth at the head of an army. He afterwards helped the seneschal, John de Havering, to put down private wars in the duchy.

At the battle of Falkirk Pons led a conroi of seventeen Gascon knights and sergeants and one rather incongruous Welshman, John de Galeys. Of these, twelve lost their horses in the battle. Since Pons served in the king's bataille, this can only mean the king's own battalion had to go into action, implying Falkirk was an even more desperately fought action that previously thought.

After the shattering French defeat at Courtrai in 1302, Pons was one of 112 Gascon exiles who sailed home from Portsmouth at the head of an army. He afterwards helped the seneschal, John de Havering, to put down private wars in the duchy.

Published on June 21, 2019 06:11

King of the North Wind

One of the supporting players in The Hooded Men is Sir James Chandos, an outlaw knight who calls himself the King of the North Wind or the Green Knight. James has made a base for himself in the ruined castle of Tickhill in West Yorkshire, from where he and his men ride out to plunder the surrounding countryside. His nicknames are meant to overawe the peasantry, duped into believing that Chandos is no man at all, but an avenging spirit of the greenwood.

James is based on a mixture of fact and legend. The Chandos family were real enough, and held lands in Herefordshire and Derbyshire. In the late thirteenth century a Sir John Chandos was pardoned by Edward I for holding Chartley Castle, in Staffordshire, against a royal army led by the king’s brother, Prince Edmund. This John was a knight of Derbyshire and as such a follower of the Earl of Derby, Robert de Ferrers, who was in revolt against the crown. I took part of the inspiration for James from John’s real-life rebellion.

The image of the Green Knight is taken from Gawaine and the Green Knight, a popular medieval tale set in the days of King Arthur. In the story Sir Gawaine, a knight of the Round Table, is forced to play ‘the beheading game’ with the mysterious knight, itself based on much older folklore motifs. Gawaine eventually tracks down his enemy at the Green Chapel, a lair inside the forest, where his life is spared as a reward for his honesty.

The King of the North Wind was another real-life outlaw, though we don’t know much about him. In 1336 a man calling himself ‘Lionel, King of the Rout Raveners’ wrote a threatening letter to the parson of Huntington, Yorkshire, addressed thus:

“Given at our Castle of the North Wind, in the Green Tower, in the first year of our reign.”

It seems Lionel saw himself as a forest lord or king, ruling from his greenwood palace of the Green Tower.

James is based on a mixture of fact and legend. The Chandos family were real enough, and held lands in Herefordshire and Derbyshire. In the late thirteenth century a Sir John Chandos was pardoned by Edward I for holding Chartley Castle, in Staffordshire, against a royal army led by the king’s brother, Prince Edmund. This John was a knight of Derbyshire and as such a follower of the Earl of Derby, Robert de Ferrers, who was in revolt against the crown. I took part of the inspiration for James from John’s real-life rebellion.

The image of the Green Knight is taken from Gawaine and the Green Knight, a popular medieval tale set in the days of King Arthur. In the story Sir Gawaine, a knight of the Round Table, is forced to play ‘the beheading game’ with the mysterious knight, itself based on much older folklore motifs. Gawaine eventually tracks down his enemy at the Green Chapel, a lair inside the forest, where his life is spared as a reward for his honesty.

The King of the North Wind was another real-life outlaw, though we don’t know much about him. In 1336 a man calling himself ‘Lionel, King of the Rout Raveners’ wrote a threatening letter to the parson of Huntington, Yorkshire, addressed thus:

“Given at our Castle of the North Wind, in the Green Tower, in the first year of our reign.”

It seems Lionel saw himself as a forest lord or king, ruling from his greenwood palace of the Green Tower.

Published on June 21, 2019 00:58

June 20, 2019

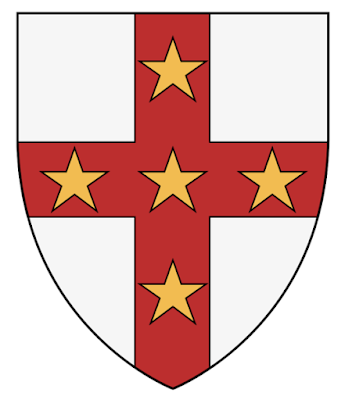

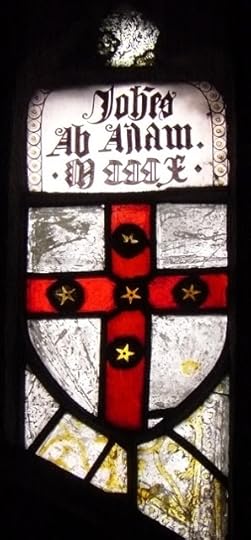

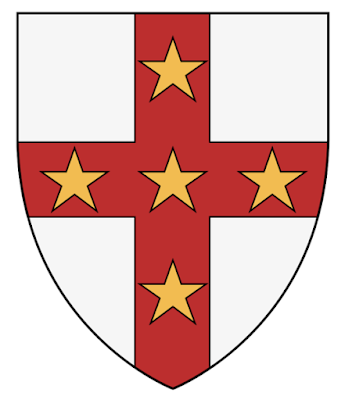

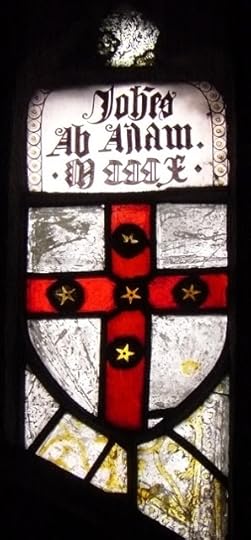

John ap Adam

The arms of John ap Adam, 1st Baron Ap-Adam. The first is from the Falkirk Roll, the second from the window of the south aisle of St Mary's church at Tidenham in Gloucestershire.

John Morris, in his Welsh Wars of Edward I, describes John as 'one of the very few Welsh adherents of England of whom we have knowledge'. The statement is dubious, since there were plenty of well-known Welsh adherents of the English crown and John was born in Charlton Adam, Gloucestershire.

That said, John must have had some Welsh connections. The form of his name - ap Adam instead of the Norman fitz - implies as much, and the parish of Tidenham used to be part of the Bigod lordship of Striguil based on Chepstow. John was unique among English nobles of this era in taking a Welsh form of his surname. At Falkirk he fought in the king's bataille, and was afterwards frequently summoned to the Scottish wars.

John Morris, in his Welsh Wars of Edward I, describes John as 'one of the very few Welsh adherents of England of whom we have knowledge'. The statement is dubious, since there were plenty of well-known Welsh adherents of the English crown and John was born in Charlton Adam, Gloucestershire.

That said, John must have had some Welsh connections. The form of his name - ap Adam instead of the Norman fitz - implies as much, and the parish of Tidenham used to be part of the Bigod lordship of Striguil based on Chepstow. John was unique among English nobles of this era in taking a Welsh form of his surname. At Falkirk he fought in the king's bataille, and was afterwards frequently summoned to the Scottish wars.

Published on June 20, 2019 11:47

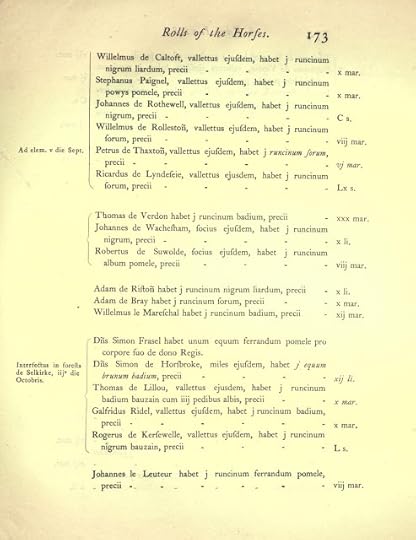

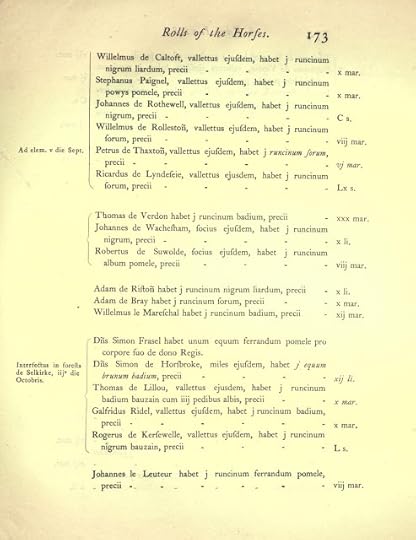

Simon Fraser

The arms of Simon Fraser of Oliver and Neidpath. Simon was captured at the Battle of Dunbar in 1296 and afterwards released in exchange for military service in Flanders. He swore fealty to Edward I on 13 October of that year, and on 28 May 1297 swore a solemn oath to serve the king in Scotland against the King of France. This oath was made at Bramber in Essex, and was a very serious affair. Both Simon and the king laid their hands on the altar as the oath was sworn. Simon’s kinsman, Richard, was present to stand surety.

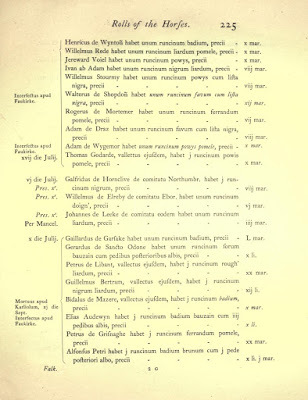

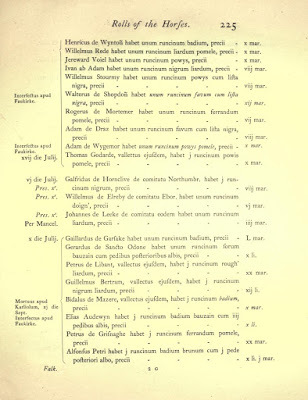

Simon served in the English army in Flanders, to King Edward’s great pleasure: the king wrote that the Scotsman’s service had ‘pleased him much’, and commanded that the lands of Simon’s valet, Geoffrey Ridell, should be restored to him. Edward then made Simon a household knight, a mix of soldier-diplomat-administrator, fed daily in the king’s hall and given new robes twice a year. Before the Battle of Falkirk he was gifted a ‘ferrand pomele’ horse by the king, another mark of favour. At the battle Simon was in the king’s bataille and led a small conroi of four valets.

Simon served in the English army in Flanders, to King Edward’s great pleasure: the king wrote that the Scotsman’s service had ‘pleased him much’, and commanded that the lands of Simon’s valet, Geoffrey Ridell, should be restored to him. Edward then made Simon a household knight, a mix of soldier-diplomat-administrator, fed daily in the king’s hall and given new robes twice a year. Before the Battle of Falkirk he was gifted a ‘ferrand pomele’ horse by the king, another mark of favour. At the battle Simon was in the king’s bataille and led a small conroi of four valets.

Published on June 20, 2019 08:03

Mortimer of Chirk

The arms of Roger Mortimer of Chirk, taken from a modern version of the Falkirk Roll.

Mortimer, a tough lord of the Welsh March, was a busy man. In the winter of 1294 he served in the first expeditionary force sent to recover Gascony from the French, and was present at the storming of St-Macaire. He was then appointed captain of Blaye, one of two remaining ducal citadels in the northern part of the duchy. Mortimer was still in Gascony the following August, where he obtained quittance for his service. In July 1297 he was summoned again to serve overseas, this time in Flanders.

As one of Edward I’s most experienced captains, Mortimer naturally served on the Falkirk campaign. In April 1298 he and William de la Pole were ordered to raise 600 Welsh foot from the lands of ‘Lanhudo’, Maskyn and Moghelan, and lead them to the King at Chester. Mortimer and his retinue were placed in the king’s own battalion, ‘Le batayle de Roy’, among such big nobs as Thomas of Lancaster, Hugh Despenser, the Earl of Warwick and John of Brittany. His kinsman, Hugh Mortimer of Richard’s Castle, served in the same bataille.

The horse-rolls for the English army at Falkirk show that Mortimer’s own troop or conroi consisted of twenty men and included three more Mortimers, Henry, John and another Roger. There were also two Welshmen, Jereward Voiel and Ivan ab Adam, and an Adam de Wygemore, doubtless raised from Mortimer’s own lordship of Wigmore on the March.

Mortimer, a tough lord of the Welsh March, was a busy man. In the winter of 1294 he served in the first expeditionary force sent to recover Gascony from the French, and was present at the storming of St-Macaire. He was then appointed captain of Blaye, one of two remaining ducal citadels in the northern part of the duchy. Mortimer was still in Gascony the following August, where he obtained quittance for his service. In July 1297 he was summoned again to serve overseas, this time in Flanders.

As one of Edward I’s most experienced captains, Mortimer naturally served on the Falkirk campaign. In April 1298 he and William de la Pole were ordered to raise 600 Welsh foot from the lands of ‘Lanhudo’, Maskyn and Moghelan, and lead them to the King at Chester. Mortimer and his retinue were placed in the king’s own battalion, ‘Le batayle de Roy’, among such big nobs as Thomas of Lancaster, Hugh Despenser, the Earl of Warwick and John of Brittany. His kinsman, Hugh Mortimer of Richard’s Castle, served in the same bataille.

The horse-rolls for the English army at Falkirk show that Mortimer’s own troop or conroi consisted of twenty men and included three more Mortimers, Henry, John and another Roger. There were also two Welshmen, Jereward Voiel and Ivan ab Adam, and an Adam de Wygemore, doubtless raised from Mortimer’s own lordship of Wigmore on the March.

Published on June 20, 2019 02:14

June 19, 2019

Mean and mild

Two starkly contrasting views on Edward I's actions in Scotland.

"By a piece of cold-blooded cruelty which shows Edward in a singularly unattractive light, he had refused to accept the garrison's surrender, even after it surrendered unconditionally, until the castle had been bombarded for a day by one of his new engines, the 'Warwolf'...the king's meanness of spirit and implacable, almost paranoiac hostility were not shared by his subjects."

"It would be wrong to think of him [Edward] acting in Scotland as a mere tyrant, if by tyrant we mean a ruler whose arbitrary whims are law, who pays no regard to local feeling and opinion, or for whom cruelty towards his subjects had become settled policy. If we look at the situation in 1304 as it appeared to Edward, we must in fairness admit that his attempted settlement was fair and statesmanlike. How many kings or governments emerging as the victors of long and bloody wars in the seventeeth, eighteenth or nineteenth centuries treated their vanquished foes as prudently and leniently as Edward treated the Scots in 1304 and 1305?"

What seems odd about the above is that both judgements come from the pages of the same book, and from the same author, GWS Barrow. One minute Edward is a mean, paranoid loony tune, the next he's a mild and statesmanlike ruler who could have taught Bismarck a thing or two. Now that's what you call dividing opinion.

"By a piece of cold-blooded cruelty which shows Edward in a singularly unattractive light, he had refused to accept the garrison's surrender, even after it surrendered unconditionally, until the castle had been bombarded for a day by one of his new engines, the 'Warwolf'...the king's meanness of spirit and implacable, almost paranoiac hostility were not shared by his subjects."

"It would be wrong to think of him [Edward] acting in Scotland as a mere tyrant, if by tyrant we mean a ruler whose arbitrary whims are law, who pays no regard to local feeling and opinion, or for whom cruelty towards his subjects had become settled policy. If we look at the situation in 1304 as it appeared to Edward, we must in fairness admit that his attempted settlement was fair and statesmanlike. How many kings or governments emerging as the victors of long and bloody wars in the seventeeth, eighteenth or nineteenth centuries treated their vanquished foes as prudently and leniently as Edward treated the Scots in 1304 and 1305?"

What seems odd about the above is that both judgements come from the pages of the same book, and from the same author, GWS Barrow. One minute Edward is a mean, paranoid loony tune, the next he's a mild and statesmanlike ruler who could have taught Bismarck a thing or two. Now that's what you call dividing opinion.

Published on June 19, 2019 07:49