David Pilling's Blog, page 59

June 4, 2019

The battle of Llandeilo Fawr

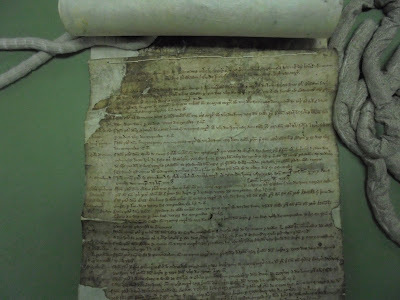

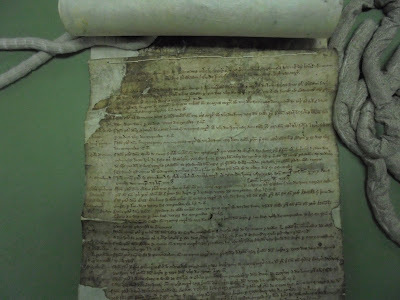

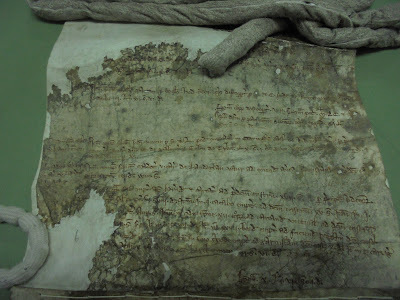

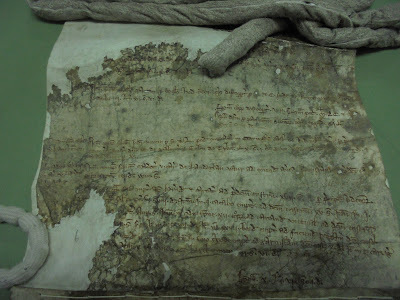

Membrane 2 of the 1282 payroll for the royal army in West Wales. This covers the period of the Battle of Llandeilo Fawr, fought on 16 June, and ought to give some useful insight away from chronicle accounts.

The relevant section of the membrane is as follows:

"[m. 2][ It is unclear whether the present m 2 originally followed the present m 1, but the damage pattern across the join would suggest that it probably did.] [Payments made by] Walter de Notingham, clerk, to bannerets, knights, esquires and foot-soldiers staying in the lord king’s garrisons at Carmarthen, Dinefwr, [...] [and Card]igan from [Monday], the morrow of the translation of St Wulfstan, namely 8 June in the [tenth] year of the reign of king Edward, with covered and uncovered horses [...][ This and the following missing headings were presumably just the names of the recipients.] [The same] Walter accounts for payment to lord John de Bello Campo, himself the third knight, with 13 covered horses, from Monday on the morrow of St Wulfstan, namely 8 June, until Tuesday in the vigil of St John the Baptist, for 16 days, each day counted, £14 8s. And know that a banneret takes 4s per day, a knight 2s, and each of the other covered horses 12d. [...] Item, payment to lord Hugh de Corten’, himself the fourth knight, with 12 covered horses, from 8 June until Tuesday in the vigil of St John the Baptist, for 16 days, each day counted, £14 8s. [...] Item, payment to H. de Monte Forti, himself the other knight, with 8 covered horses, from 8 June until Saturday next after the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed John the Baptist, namely 27 June, for 20 days, each day counted, £10. [Si]mon de Monte Acuto Item, payment to lord Simon de Monte Acuto, with 4 covered horses, from 8 June until Saturday next after the feast of the Nativity of St John the Baptist, namely for 20 days, each day counted, 100s. Hugh Poinz Item, payment to lord Hugh Poinz, with 4 covered horses, from 8 June until Saturday next after the feast of the Nativity of St John the Baptist, for 20 days, each day counted, 100s. William de Moun Item, payment to lord William de Moun, himself the other knight, with 8 covered horses, who came from England on Thursday next after the feast of St Augustine, namely 28 May, until Thursday in the feast of St Botulph, 17 June, for 21 days, each day counted, £10 10s. And therefore he received payment for the 11 days of the time for which the said knights received payment from the king’s wardrobe because the same lord William received no payment in the same wardrobe. And know that all the said bannerets and knights at that time were in the army which lord G. de Clare led into ‘Estratewy’.”

Much of our understanding of the battle comes from John Morris and his book The Welsh Wars of Edward I, published in 1901. Unfortunately Morris made mistakes. Of the aftermath of the battle, he wrote:

“The English in the south seem to have been completely paralyzed for the next six weeks. The paid cavalry, suspiciously reduced in number since the battle of Llandeilo, were divided into two bodies of about thirty-five lances each, one sent to garrison Cardigan under Philip Daubeney, the other remaining under Alan Plukenet to hold Dynevor, while John de Beauchamp and his troops were probably at Carmarthen”.

Morris failed to notice the header of the membrane, which shows the English were already in garrison at these places from 8 June, eight days before the battle. Wages were paid out as normal, with no sign of panic or disruption or a break in accounting, which one might expect after a heavy defeat. There is, in fact, no sign of an engagement at all.

All the accounts, English and Welsh, agree the most important casualty of the battle was William de Valence junior, heir to the earldom of Pembroke. The only other named casualty is Richard Argentine, an English knight. Neither of these men are mentioned anywhere on Clare’s payroll. Therefore the assumption must be that Valence was in charge of a separate division of the army, for which a payroll has not survived. This division was ambushed and mauled by the Welsh in a narrow wooded pass somewhere near Llandeilo. The main host under Clare was untouched.

Since Clare was in overall command, this can only mean he had split his forces in the middle of enemy territory: an apt comparison would be Lord Chelmsford before Isandlwana, with similar results. He paid for his incompetence and was stripped of command by King Edward, who replaced him with William de Valence senior as ‘captain of the army of West Wales’.

The relevant section of the membrane is as follows:

"[m. 2][ It is unclear whether the present m 2 originally followed the present m 1, but the damage pattern across the join would suggest that it probably did.] [Payments made by] Walter de Notingham, clerk, to bannerets, knights, esquires and foot-soldiers staying in the lord king’s garrisons at Carmarthen, Dinefwr, [...] [and Card]igan from [Monday], the morrow of the translation of St Wulfstan, namely 8 June in the [tenth] year of the reign of king Edward, with covered and uncovered horses [...][ This and the following missing headings were presumably just the names of the recipients.] [The same] Walter accounts for payment to lord John de Bello Campo, himself the third knight, with 13 covered horses, from Monday on the morrow of St Wulfstan, namely 8 June, until Tuesday in the vigil of St John the Baptist, for 16 days, each day counted, £14 8s. And know that a banneret takes 4s per day, a knight 2s, and each of the other covered horses 12d. [...] Item, payment to lord Hugh de Corten’, himself the fourth knight, with 12 covered horses, from 8 June until Tuesday in the vigil of St John the Baptist, for 16 days, each day counted, £14 8s. [...] Item, payment to H. de Monte Forti, himself the other knight, with 8 covered horses, from 8 June until Saturday next after the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed John the Baptist, namely 27 June, for 20 days, each day counted, £10. [Si]mon de Monte Acuto Item, payment to lord Simon de Monte Acuto, with 4 covered horses, from 8 June until Saturday next after the feast of the Nativity of St John the Baptist, namely for 20 days, each day counted, 100s. Hugh Poinz Item, payment to lord Hugh Poinz, with 4 covered horses, from 8 June until Saturday next after the feast of the Nativity of St John the Baptist, for 20 days, each day counted, 100s. William de Moun Item, payment to lord William de Moun, himself the other knight, with 8 covered horses, who came from England on Thursday next after the feast of St Augustine, namely 28 May, until Thursday in the feast of St Botulph, 17 June, for 21 days, each day counted, £10 10s. And therefore he received payment for the 11 days of the time for which the said knights received payment from the king’s wardrobe because the same lord William received no payment in the same wardrobe. And know that all the said bannerets and knights at that time were in the army which lord G. de Clare led into ‘Estratewy’.”

Much of our understanding of the battle comes from John Morris and his book The Welsh Wars of Edward I, published in 1901. Unfortunately Morris made mistakes. Of the aftermath of the battle, he wrote:

“The English in the south seem to have been completely paralyzed for the next six weeks. The paid cavalry, suspiciously reduced in number since the battle of Llandeilo, were divided into two bodies of about thirty-five lances each, one sent to garrison Cardigan under Philip Daubeney, the other remaining under Alan Plukenet to hold Dynevor, while John de Beauchamp and his troops were probably at Carmarthen”.

Morris failed to notice the header of the membrane, which shows the English were already in garrison at these places from 8 June, eight days before the battle. Wages were paid out as normal, with no sign of panic or disruption or a break in accounting, which one might expect after a heavy defeat. There is, in fact, no sign of an engagement at all.

All the accounts, English and Welsh, agree the most important casualty of the battle was William de Valence junior, heir to the earldom of Pembroke. The only other named casualty is Richard Argentine, an English knight. Neither of these men are mentioned anywhere on Clare’s payroll. Therefore the assumption must be that Valence was in charge of a separate division of the army, for which a payroll has not survived. This division was ambushed and mauled by the Welsh in a narrow wooded pass somewhere near Llandeilo. The main host under Clare was untouched.

Since Clare was in overall command, this can only mean he had split his forces in the middle of enemy territory: an apt comparison would be Lord Chelmsford before Isandlwana, with similar results. He paid for his incompetence and was stripped of command by King Edward, who replaced him with William de Valence senior as ‘captain of the army of West Wales’.

Published on June 04, 2019 03:45

The fall of Adam

Adam’s downfall.

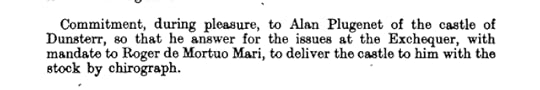

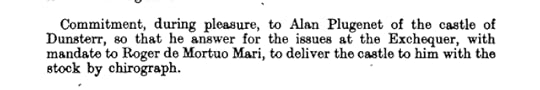

Adam Gurdun’s time in the sun was very brief. After the battle of Evesham the Montfortian regime crumbled into dust, and the late earl’s garrisons went down like ninepins. Soon after the battle Roger Mortimer, Adam’s former captain, stormed into the southwest to crush the rebels in Somerset before rejoining Henry III at Winchester. By 22 August he was in possession of Adam’s stronghold at Dunster. There is no hint of a siege or assault, and it seems Adam simply abandoned the castle and fled. This was standard tactics: nobody with any sense wanted to be bottled up inside four walls with no hope of relief. It may be that Adam struck a deal with Mortimer, since they were old mates, and was allowed to depart unmolested.

That was not the end. Adam now turned outlaw and charged off into Buckinghamshire at the head of a company of ‘free lances’. The sheriff of Bucks, Geoffrey le Rus, later complained that Adam’s men had prevented him from holding tourns (a bi-annual inspection of the hundreds of the shire) and collecting rents. Rus alleged he was:

“Impeded by Adam Gurdon, David de Uffington, John Russell, and others of the island [Ely]. Could not hold tourns in the two magni comitatus in Bucks. Damages estimated at 10 marks”.

This shows that Adam was now in cahoots with the rebels of Ely, who came down from the north and garrisoned Hereward the Wake’s old stronghold in the spring of 1266. In proper tragic style, Adam was about to be shafted by one of his own. Shortly before Ascension Day (30 May) one of his men, Robert Chadd, stole away from the outlaw camp and told the Lord Edward where he might find Adam’s hideout. The sneak.

Adam Gurdun’s time in the sun was very brief. After the battle of Evesham the Montfortian regime crumbled into dust, and the late earl’s garrisons went down like ninepins. Soon after the battle Roger Mortimer, Adam’s former captain, stormed into the southwest to crush the rebels in Somerset before rejoining Henry III at Winchester. By 22 August he was in possession of Adam’s stronghold at Dunster. There is no hint of a siege or assault, and it seems Adam simply abandoned the castle and fled. This was standard tactics: nobody with any sense wanted to be bottled up inside four walls with no hope of relief. It may be that Adam struck a deal with Mortimer, since they were old mates, and was allowed to depart unmolested.

That was not the end. Adam now turned outlaw and charged off into Buckinghamshire at the head of a company of ‘free lances’. The sheriff of Bucks, Geoffrey le Rus, later complained that Adam’s men had prevented him from holding tourns (a bi-annual inspection of the hundreds of the shire) and collecting rents. Rus alleged he was:

“Impeded by Adam Gurdon, David de Uffington, John Russell, and others of the island [Ely]. Could not hold tourns in the two magni comitatus in Bucks. Damages estimated at 10 marks”.

This shows that Adam was now in cahoots with the rebels of Ely, who came down from the north and garrisoned Hereward the Wake’s old stronghold in the spring of 1266. In proper tragic style, Adam was about to be shafted by one of his own. Shortly before Ascension Day (30 May) one of his men, Robert Chadd, stole away from the outlaw camp and told the Lord Edward where he might find Adam’s hideout. The sneak.

Published on June 04, 2019 01:08

June 3, 2019

Adam's time in the sun

In July 1265, as his short-lived government crumbled about his ears, Simon de Montfort finally turned to Adam Gurdun. On 16 June, at Hereford, Simon made Adam keeper of the Isle of Lundy, with the promise that he would be enfeoffed with Lundy and its castle if he ‘kept it safe’. This appointment was made in the hope that Adam would prevent William de Valence, recently landed in Pembroke, from raising ships to sail across the Bristol Channel and link up with the Lord Edward.

Adam had no time to worry about Valence. On 1 August, even as Edward’s forces closed in on Simon, a royalist army landed at Minehead on the coast of north Somerset. They were composed of Welshmen, probably raised in Glamorgan, and led by a knight of ‘evil reputation’ named Sir William Berkeley. This was probably part of a wider royalist strategy to outflank Montfort and pin down his supporters in the West Country.

The raiders set about pillaging the countryside. They were surprised and driven back into the sea by Adam and his men, who had ridden out from Dunster to face the threat:

“Of the slaughter of the Welsh. In this year, on the Sunday before the battle of Evesham, a host of Welshmen, under the command of William Berkeley, a noble knight, though notorious for his evil deeds, landed at Minehead, near the castle of Dunster, for the purpose of pillaging Somersetshire. They were, however, met by the governor of that castle, Adam Gordon, who slew great numbers of them, and put the rest of them to flight, together with their chief, a great many being drowned in their flight.” - William Rishanger

This battle was an interesting example of Welshmen fighting on both sides: Earl Simon also had large numbers of Welsh troops in his army. Adam had won a pyrrhic victory. Three days later Simon’s host was exterminated at Evesham.

Adam had no time to worry about Valence. On 1 August, even as Edward’s forces closed in on Simon, a royalist army landed at Minehead on the coast of north Somerset. They were composed of Welshmen, probably raised in Glamorgan, and led by a knight of ‘evil reputation’ named Sir William Berkeley. This was probably part of a wider royalist strategy to outflank Montfort and pin down his supporters in the West Country.

The raiders set about pillaging the countryside. They were surprised and driven back into the sea by Adam and his men, who had ridden out from Dunster to face the threat:

“Of the slaughter of the Welsh. In this year, on the Sunday before the battle of Evesham, a host of Welshmen, under the command of William Berkeley, a noble knight, though notorious for his evil deeds, landed at Minehead, near the castle of Dunster, for the purpose of pillaging Somersetshire. They were, however, met by the governor of that castle, Adam Gordon, who slew great numbers of them, and put the rest of them to flight, together with their chief, a great many being drowned in their flight.” - William Rishanger

This battle was an interesting example of Welshmen fighting on both sides: Earl Simon also had large numbers of Welsh troops in his army. Adam had won a pyrrhic victory. Three days later Simon’s host was exterminated at Evesham.

Published on June 03, 2019 01:06

June 2, 2019

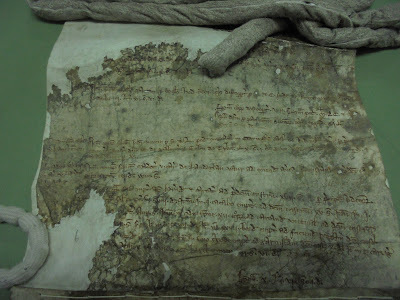

More sheepskin

Membrane two of the payroll. Some of you may notice this looks rather like membrane one: this is because I forgot to take photos of the detached fragments of the first two membranes, so I'm using membrane three of the main roll as a substitute. Clear? Clear as a bell.

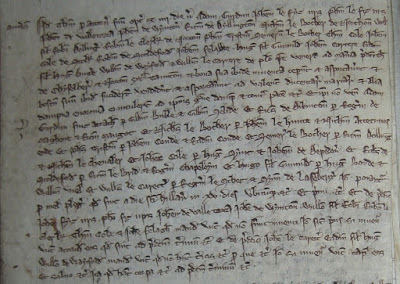

The below includes Professor Mackman's notes.

C 47/2/1/15

[The top of this fragment is also badly damaged, and only fragments survive of the first few lines of text. The fragment actually comprises the foot of one membrane and the head of the next, stitched together, and there is a gap of 2-3cm of blank parchment across the join.]

[m.1] [...] covered horses [...] days, £11 12s 4d. [...] for the said [...] days, £10 [...]s 4d. [...] foot-soldiers of W[...], for 3 days, £14 ?10s. [...] covered horse and 100 foot-soldiers and charcoal-burners from the forest of Dean, for 2 days, 51s. And each of the said charcoal-burners took 3d per day. [...] constables with 2 covered horses and ?12 uncovered horses, 2 standard-bearers and 1200 foot-soldiers from Brecon, for payment for the aforesaid Saturday, who then came [...] Landenf[...] 4s 8d. Sum of the covered horses – 29. Sum of the uncovered horses – 43. Sum of the foot-soldiers, [...], standard-bearers and other foot – 8,026 foot coming with the earl [...]. Payment of the aforesaid for the said 4 days - £250 [...]. [m. 2] [...] constables [...] uncovered horses and foot-soldiers for the aforesaid earl, in the presence of [...] days of Sunday, Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday next following the feast of St Barnabas the Apostle in the abovesaid year. [...] accounts for payment to David ?ap Adam, constable, with 1 covered horse, for himself with 1 standard-bearer and 240 foot-soldiers from ‘Machen’, for the aforesaid 4 days,£8 13s 4d, as appears above by the particulars. [..] accounts for payment to Howel ap Ivor, constable, with 1 uncovered horse, and Ihewan ap Dun, with 1 covered horse, and Dun Vachan, constable, with [...] covered horse, and 1 standard-bearer and 606 foot-soldiers from ‘Meynghenith’, for the aforesaid 4 days, £21 13s 4s, as appears above by the particulars. [...] accounts for payment to Meurik G[och?], constable, with 1 uncovered horse and 161 foot-soldiers from Kibbor, for the aforesaid 4 days, 114s 8d. [...] accounts for payment to Adam Berkerol, constable, with [?1] uncovered [horse], and Adam ap Walter, constable, with 1 uncovered horse, and 105 foot-soldiers from ‘?Dempn’’,[ Initial capital unclear – could be D, B, K or another letter. Abbreviated ending may be ‘-er’?] for the aforesaid 4 days, [...] 2d. [...] [...]ynon ap [...]enew[...], constable, with 1 uncovered horse, and Adam Vachan, constable, with 1 uncovered horse, and the bailiff of the same place [...] 283 foot-soldiers of Wentloog, for the said 4 days, [...].

The below includes Professor Mackman's notes.

C 47/2/1/15

[The top of this fragment is also badly damaged, and only fragments survive of the first few lines of text. The fragment actually comprises the foot of one membrane and the head of the next, stitched together, and there is a gap of 2-3cm of blank parchment across the join.]

[m.1] [...] covered horses [...] days, £11 12s 4d. [...] for the said [...] days, £10 [...]s 4d. [...] foot-soldiers of W[...], for 3 days, £14 ?10s. [...] covered horse and 100 foot-soldiers and charcoal-burners from the forest of Dean, for 2 days, 51s. And each of the said charcoal-burners took 3d per day. [...] constables with 2 covered horses and ?12 uncovered horses, 2 standard-bearers and 1200 foot-soldiers from Brecon, for payment for the aforesaid Saturday, who then came [...] Landenf[...] 4s 8d. Sum of the covered horses – 29. Sum of the uncovered horses – 43. Sum of the foot-soldiers, [...], standard-bearers and other foot – 8,026 foot coming with the earl [...]. Payment of the aforesaid for the said 4 days - £250 [...]. [m. 2] [...] constables [...] uncovered horses and foot-soldiers for the aforesaid earl, in the presence of [...] days of Sunday, Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday next following the feast of St Barnabas the Apostle in the abovesaid year. [...] accounts for payment to David ?ap Adam, constable, with 1 covered horse, for himself with 1 standard-bearer and 240 foot-soldiers from ‘Machen’, for the aforesaid 4 days,£8 13s 4d, as appears above by the particulars. [..] accounts for payment to Howel ap Ivor, constable, with 1 uncovered horse, and Ihewan ap Dun, with 1 covered horse, and Dun Vachan, constable, with [...] covered horse, and 1 standard-bearer and 606 foot-soldiers from ‘Meynghenith’, for the aforesaid 4 days, £21 13s 4s, as appears above by the particulars. [...] accounts for payment to Meurik G[och?], constable, with 1 uncovered horse and 161 foot-soldiers from Kibbor, for the aforesaid 4 days, 114s 8d. [...] accounts for payment to Adam Berkerol, constable, with [?1] uncovered [horse], and Adam ap Walter, constable, with 1 uncovered horse, and 105 foot-soldiers from ‘?Dempn’’,[ Initial capital unclear – could be D, B, K or another letter. Abbreviated ending may be ‘-er’?] for the aforesaid 4 days, [...] 2d. [...] [...]ynon ap [...]enew[...], constable, with 1 uncovered horse, and Adam Vachan, constable, with 1 uncovered horse, and the bailiff of the same place [...] 283 foot-soldiers of Wentloog, for the said 4 days, [...].

Published on June 02, 2019 10:58

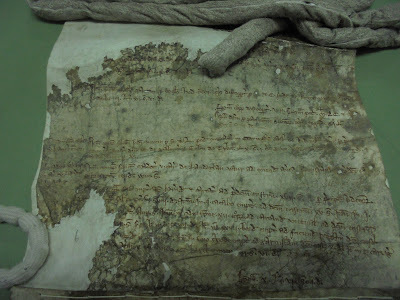

Bits of old sheepskin

Part one of a potentially very dull series, in which I post a membrane from a surviving medieval document and the accompanying translation.

The document is C 47/2/4, the payroll for the royal army of West Wales in 1282/3. Parts of it are in very bad condition, but the translator (Professor Jonathan Mackman) did what he could by placing the fragments under ultraviolet. It may look like a mouldy bit of old sheepskin, and indeed it is, but this is primary source material; the closest we can possibly get to actual events.

The first two fragments are separated from the bulk of the roll. Membrane 1 is below. The text is an account roll for wages of troops raised by the Earl of Gloucester, Gilbert de Clare, to campaign against the supporters of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in the west.

[The top of this fragment is badly damaged, and only small sections of the text remain there.]

[...] [...] for himself, 2 standard-bearers and ?672 foot-soldiers of [...]sk for the said 3 days. [...] days, £14 5s. [...] of ‘Mach’, for the said 3 days, £6 10s. [...] foot-soldiers of [...]ntloogh[ Possibly Wentloog?] for the said 3 days, £7 12s [...][ Large gap, possibly room for two or three lines of text. One may have been a heading?] [...] covered and 2 uncovered horses, and 220 foot-soldiers of ‘Tha[...]’, [...] £6 18d. [...] covered horse and 3 uncovered horses, for himself, 1 standard-bearer and 360 foot-soldiers of ‘Lang[...], for the aforesaid 3 days, £9 17s 6d. Item, for one constable with ?1 uncovered horse, for himself, 1 standard-bearer and 282 foot-soldiers from Neath, for the said 3 days, £7 10s 6d. [...]th. Item, 10 ?covered horses and 20 foot-soldiers of ‘Th’, 40s 6d. Ruthin Item, 1 constable with 1 un-armoured (‘nudo’) horse, for himself and 77 foot-soldiers from Ruthin, for the said 3 days, 42s. ‘Landevoddoc’ Item, 2 constables with 2 un-armoured horses, for themselves and 76 foot-soldiers from ‘Landevoddi’, for the said 3 days, 43s. Kibbor Item, 1 constable with 1 uncovered horse, for himself, 1 standard-bearer and 157 foot-soldiers from Kibbor, for the said 3 days, £4 4s 6d. Caldicot Item, 1 constable with 1 uncovered horse, for himself and 20 foot-soldiers from Caldicot, for the said 3 days, 12s. Forest of Dean Item, 12 men from the forest, for 5 days, 15s, namely for each 3d per day. ‘Aven’’ Item, 2 standard-bearers and 160 foot-soldiers from ‘Aven’’ for the said 3 days, £4 6s. ‘Koytif’ Item, 1 constable with 1 un-armoured (‘nudo’) horse, for himself, 1 standard-bearer and 369 foot-soldiers from ‘Coytif’, for the said 3 days, £9 16s.

The document is C 47/2/4, the payroll for the royal army of West Wales in 1282/3. Parts of it are in very bad condition, but the translator (Professor Jonathan Mackman) did what he could by placing the fragments under ultraviolet. It may look like a mouldy bit of old sheepskin, and indeed it is, but this is primary source material; the closest we can possibly get to actual events.

The first two fragments are separated from the bulk of the roll. Membrane 1 is below. The text is an account roll for wages of troops raised by the Earl of Gloucester, Gilbert de Clare, to campaign against the supporters of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in the west.

[The top of this fragment is badly damaged, and only small sections of the text remain there.]

[...] [...] for himself, 2 standard-bearers and ?672 foot-soldiers of [...]sk for the said 3 days. [...] days, £14 5s. [...] of ‘Mach’, for the said 3 days, £6 10s. [...] foot-soldiers of [...]ntloogh[ Possibly Wentloog?] for the said 3 days, £7 12s [...][ Large gap, possibly room for two or three lines of text. One may have been a heading?] [...] covered and 2 uncovered horses, and 220 foot-soldiers of ‘Tha[...]’, [...] £6 18d. [...] covered horse and 3 uncovered horses, for himself, 1 standard-bearer and 360 foot-soldiers of ‘Lang[...], for the aforesaid 3 days, £9 17s 6d. Item, for one constable with ?1 uncovered horse, for himself, 1 standard-bearer and 282 foot-soldiers from Neath, for the said 3 days, £7 10s 6d. [...]th. Item, 10 ?covered horses and 20 foot-soldiers of ‘Th’, 40s 6d. Ruthin Item, 1 constable with 1 un-armoured (‘nudo’) horse, for himself and 77 foot-soldiers from Ruthin, for the said 3 days, 42s. ‘Landevoddoc’ Item, 2 constables with 2 un-armoured horses, for themselves and 76 foot-soldiers from ‘Landevoddi’, for the said 3 days, 43s. Kibbor Item, 1 constable with 1 uncovered horse, for himself, 1 standard-bearer and 157 foot-soldiers from Kibbor, for the said 3 days, £4 4s 6d. Caldicot Item, 1 constable with 1 uncovered horse, for himself and 20 foot-soldiers from Caldicot, for the said 3 days, 12s. Forest of Dean Item, 12 men from the forest, for 5 days, 15s, namely for each 3d per day. ‘Aven’’ Item, 2 standard-bearers and 160 foot-soldiers from ‘Aven’’ for the said 3 days, £4 6s. ‘Koytif’ Item, 1 constable with 1 un-armoured (‘nudo’) horse, for himself, 1 standard-bearer and 369 foot-soldiers from ‘Coytif’, for the said 3 days, £9 16s.

Published on June 02, 2019 06:17

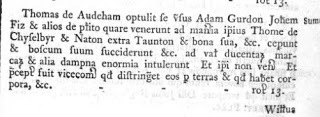

Adam's merry men

Throughout 1263-4 Adam Gurdun continues his rampage across Dorset. The royalists can do nothing with him: he pops up all over the place, seizes some loot and vanishes into the forests. He raids Crewkerne to steal weapons, and then embarks on a string of large-scale robberies aimed at royalist knights. At Cheddar he breaks into the manor of Sir Ralph Bakepuz, battering down the door and smashing windows, and steals £100 for his war-chest; he attacks the lands of another wealthy royalist, Thomas Audenham, at Chiselborough and Norton, cuts down the woods and takes goods to the value of 200 marks.

Adam’s followers hail from all over Dorset and Somerset, and include a great crowd of peasants as well as local gentry. There is something remarkable about these men. Other Montfortian captains in Dorset, such as Sir John de la Warr and Sir Robert Verdun, were later accused of forcing men into their service. No charges of coercion were ever laid against Adam, and the peasants who joined him appear to have been volunteers, drawn by Adam’s charisma and (perhaps) their own political convictions. His company included two priests who were accused of ‘abetting him’; they probably acted as preachers, making a form of crusade out of Adam’s revolt and the reform movement in England. At Chiselborough and Norton his band also included ‘Robert le Clerc of Norton’, the local priest.

Published on June 02, 2019 04:13

June 1, 2019

Adam Gurdun, part the next

Back to the bold Sir Adam.

In 1251 the Sheriff of Dorset, Henry of Earley, was replaced by Elias de Rabayn. Elias was a Poitevin and had only arrived at the English court in 1248, probably in the entourage of Henry III’s Lusignan half-brothers. He soon made his presence felt in Dorset.

The king granted Elias the wardship of the lands and two daughters of Stephen of Bayeux, an old man who had just inherited a barony in Lincolnshire and two manors in Dorset. Just before he died, Stephen was ‘persuaded’ by the king to marry one of his daughters, Maud, to Elias. The entire estate was then settled on the couple and the other daughter, Joan, disinherited. Joan was sent to Sixhills convent in Lincolnshire, a favourite dumping ground for unwanted female gentlefolk. In 1253 she was abducted by Elias and smuggled off abroad, to be married to a Poitevin nobleman. She never saw England again, though her son later returned to try and claim his inheritance.

It may be that Henry appointed Elias as Sheriff of Dorset to stifle local opposition to his marriage. The new sheriff didn’t help matters by screwing down hard on the locals: he and his deputy, Walter Burges, were accused of extortion. In February 1253 Walter was violently assaulted by the people of Shaftesbury, a rare experience for Henry III’s sheriffs and unprecedented in Dorset. Elias and Walter also engaged in a power struggle with the Earl of Gloucester, and began to stockpile weapons at Corfe Castle.

Another of the king’s half-brothers, Aymer de Lusignan, also threw his weight around in Dorset. As bishop-elect of Winchester, Aymer grabbed the port of Weymouth, the manor of Wyke and the island of Portland, in the teeth of protests from local landowners. Aymer also got permission to fortify Portland by a royal licence obtained from a council packed with his friends, while his bailiff squeezed tolls from local shipping. His activities were condemned in the Petition of the Barons:

“No-one shall be allowed to fortify a castle upon a harbour, or upon an island within a harbour, unless by the consent of the council of the whole realm of England.”

By the early 1260s Dorset was ready to boil over. All the protesters lacked was a leader. Step forward Adam Gurdun. In June 1263 the justices in eyre at Sherborne in Dorset reported they dared not leave the town, for “the enemies of the lord king were going with flags flying through the country plundering loyal subjects”.

The ‘loyal subjects’ were the king’s supporters in the region. Adam’s revolt had begun.

In 1251 the Sheriff of Dorset, Henry of Earley, was replaced by Elias de Rabayn. Elias was a Poitevin and had only arrived at the English court in 1248, probably in the entourage of Henry III’s Lusignan half-brothers. He soon made his presence felt in Dorset.

The king granted Elias the wardship of the lands and two daughters of Stephen of Bayeux, an old man who had just inherited a barony in Lincolnshire and two manors in Dorset. Just before he died, Stephen was ‘persuaded’ by the king to marry one of his daughters, Maud, to Elias. The entire estate was then settled on the couple and the other daughter, Joan, disinherited. Joan was sent to Sixhills convent in Lincolnshire, a favourite dumping ground for unwanted female gentlefolk. In 1253 she was abducted by Elias and smuggled off abroad, to be married to a Poitevin nobleman. She never saw England again, though her son later returned to try and claim his inheritance.

It may be that Henry appointed Elias as Sheriff of Dorset to stifle local opposition to his marriage. The new sheriff didn’t help matters by screwing down hard on the locals: he and his deputy, Walter Burges, were accused of extortion. In February 1253 Walter was violently assaulted by the people of Shaftesbury, a rare experience for Henry III’s sheriffs and unprecedented in Dorset. Elias and Walter also engaged in a power struggle with the Earl of Gloucester, and began to stockpile weapons at Corfe Castle.

Another of the king’s half-brothers, Aymer de Lusignan, also threw his weight around in Dorset. As bishop-elect of Winchester, Aymer grabbed the port of Weymouth, the manor of Wyke and the island of Portland, in the teeth of protests from local landowners. Aymer also got permission to fortify Portland by a royal licence obtained from a council packed with his friends, while his bailiff squeezed tolls from local shipping. His activities were condemned in the Petition of the Barons:

“No-one shall be allowed to fortify a castle upon a harbour, or upon an island within a harbour, unless by the consent of the council of the whole realm of England.”

By the early 1260s Dorset was ready to boil over. All the protesters lacked was a leader. Step forward Adam Gurdun. In June 1263 the justices in eyre at Sherborne in Dorset reported they dared not leave the town, for “the enemies of the lord king were going with flags flying through the country plundering loyal subjects”.

The ‘loyal subjects’ were the king’s supporters in the region. Adam’s revolt had begun.

Published on June 01, 2019 07:12

Private thoughts

One of the pleasures of researching the Civil War era is the amount of surviving information: private and public correspondence, charters, manuals, satirical pamphlets etc etc. Great heaps of the stuff. The more intimate material, which rarely survives for the medieval era, gives an insight into the private thoughts of individuals.

The below was written in 1638 by Bevil Grenville, a royalist commander and nobleman of Devon and Cornwall, on the eve of war with Scotland: "I cannot contain myself within my doors when the King of England's standard waves in the field upon so just occasions, the cause being such as must make all those that die in it little inferior to Martyrs. And for mine own part I desire to acquire an honest name in an honourable grave. I never loved my life or ease so much as to shun an occasion which if I should I were unworthy of the profession I have held, or to succeed those ancestors of mine, who have so many of them in several ages sacrificed their lives for their country."

Bevil seems to have been well aware he would not survive. In 1643 he led the charge of Cornish infantry at the Battle of Lansdowne near Bath in Somerset. As the fight raged, his skull was broken by a pole-axe and he was carried off the field to a nearby rectory, where he died the same day. His Cornishmen refused to serve under any other leader and returned home.

Above is a pic of Bevil's monument, which stands on Lansdowne Hill near Bath.

The below was written in 1638 by Bevil Grenville, a royalist commander and nobleman of Devon and Cornwall, on the eve of war with Scotland: "I cannot contain myself within my doors when the King of England's standard waves in the field upon so just occasions, the cause being such as must make all those that die in it little inferior to Martyrs. And for mine own part I desire to acquire an honest name in an honourable grave. I never loved my life or ease so much as to shun an occasion which if I should I were unworthy of the profession I have held, or to succeed those ancestors of mine, who have so many of them in several ages sacrificed their lives for their country."

Bevil seems to have been well aware he would not survive. In 1643 he led the charge of Cornish infantry at the Battle of Lansdowne near Bath in Somerset. As the fight raged, his skull was broken by a pole-axe and he was carried off the field to a nearby rectory, where he died the same day. His Cornishmen refused to serve under any other leader and returned home.

Above is a pic of Bevil's monument, which stands on Lansdowne Hill near Bath.

Published on June 01, 2019 04:12

The best kisser in the kingdom...

Christopher Hibbert's description of Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Charles I's nephew and dashing cavalry officer. Woof, woof!

"Yet Rupert was far more than a rough, handsome soldier of fortune with a taste for fancy clothes, fringed boots, feathered hats, scarlet sashes and long curled hair; he was more than a cavalry leader of undeniable skill and courage. He was highly intelligent, a remarkable linguist, an artist of uncommon merit, a man with an inventive skill and curiosity of mind that was to give as much pleasure to his later years of sickness and premature old age as the several mistresses who visited him in his rooms at Windsor Castle."

"Yet Rupert was far more than a rough, handsome soldier of fortune with a taste for fancy clothes, fringed boots, feathered hats, scarlet sashes and long curled hair; he was more than a cavalry leader of undeniable skill and courage. He was highly intelligent, a remarkable linguist, an artist of uncommon merit, a man with an inventive skill and curiosity of mind that was to give as much pleasure to his later years of sickness and premature old age as the several mistresses who visited him in his rooms at Windsor Castle."

Published on June 01, 2019 01:29

May 31, 2019

God save the King!

Let's take a break from the medieval era for a moment, and move forward in time to a blustery summer's day in Nottingham on 22 August 1642. On that day Charles I unfurled his standard of war on the summit of the highest tower of Nottingham Castle, heralding the start of the English Civil War - or the War of the Three Kingdoms, or the British & Irish Civil Wars (delete or add to taste).

Charles I

Charles I

From the evidence given by eye-witnesses at the trial of the King in 1649, we learn the following particulars concerning the raising of his standard:—

"Robert Large, painter, of the town and county of Nottingham, deposed upon oath that in the summer of 1642 he painted, by command of my Lord Beaumont, the great standard of war that was placed upon the high tower of the Castle of Nottingham, and that he often saw the King thereabouts, at the same time that his standard was erected and displayed.”

"Samuel Lawson, of Nottingham, maltster, aged 30 years or thereabouts, sworn and examined, saith: That about August, 1642, he this deponent saw the King’s standard brought forth of Nottingham Castle, borne upon divers gentlemen’s shoulders, who (as the report was) were noblemen; and he saw the same carried by them on the Hill close adjoining the Castle, with a herald before it; and there the said standard was erected, with great shouting, acclamations, and sound of drums and trumpets; and that when the said standard was so erected there was a proclamation made; and that he, this deponent, saw the King present at the erecting thereof.”

We are told the standard was “a large red streamer, pennon shaped, cloven at the end, attached to a long red staff having about twenty supporters, and bore next the staff a St. George’s Cross, then an escutcheon of the Royal Arms, with a hand pointing to the crown above it, and the legend:

"GIVE UNTO CAESAR HIS DUE,"

together with two other crowns, each surmounted by a lion passant."

Three days later the royal standard was unfurled again, this time on an open field on the north side of the castle wall (now marked by a tablet). It took twenty men to carry the banner into the field, and they had to hold it upright after digging an insufficiently deep hole with daggers and knives. The royal herald made a mess of his speech, and then a strong gust of wind blew the standard down. Not a very auspicious start for the royalists.

Charles I

Charles IFrom the evidence given by eye-witnesses at the trial of the King in 1649, we learn the following particulars concerning the raising of his standard:—

"Robert Large, painter, of the town and county of Nottingham, deposed upon oath that in the summer of 1642 he painted, by command of my Lord Beaumont, the great standard of war that was placed upon the high tower of the Castle of Nottingham, and that he often saw the King thereabouts, at the same time that his standard was erected and displayed.”

"Samuel Lawson, of Nottingham, maltster, aged 30 years or thereabouts, sworn and examined, saith: That about August, 1642, he this deponent saw the King’s standard brought forth of Nottingham Castle, borne upon divers gentlemen’s shoulders, who (as the report was) were noblemen; and he saw the same carried by them on the Hill close adjoining the Castle, with a herald before it; and there the said standard was erected, with great shouting, acclamations, and sound of drums and trumpets; and that when the said standard was so erected there was a proclamation made; and that he, this deponent, saw the King present at the erecting thereof.”

We are told the standard was “a large red streamer, pennon shaped, cloven at the end, attached to a long red staff having about twenty supporters, and bore next the staff a St. George’s Cross, then an escutcheon of the Royal Arms, with a hand pointing to the crown above it, and the legend:

"GIVE UNTO CAESAR HIS DUE,"

together with two other crowns, each surmounted by a lion passant."

Three days later the royal standard was unfurled again, this time on an open field on the north side of the castle wall (now marked by a tablet). It took twenty men to carry the banner into the field, and they had to hold it upright after digging an insufficiently deep hole with daggers and knives. The royal herald made a mess of his speech, and then a strong gust of wind blew the standard down. Not a very auspicious start for the royalists.

Published on May 31, 2019 06:46