David Pilling's Blog, page 57

June 14, 2019

Power and kingship

More on power and titles from RR Davies:

“Never had the presence of English power, be it in the person of the king himself or that of his appointed representatives…been so ubiquitously and awesomely present in the outer zones of the British Isles as in the last fifteen years or so of Edward I’s reign.

It was, of course, the triumph of power; contemporaries were not short of saying so. Sometimes they said it crudely: the magnates had bragged that England could exterminate Scotland without any external help. ‘What matter if both the Welsh and Scots are our foes?’ so Edward I is alleged to have boasted. ‘Let them join forces if they please. We shall beat them both in a single day.’ These statements may have been made, as we would say, off the record, but even on the record Edward I’s language made no bones of the fact that in this instance might was right. Power and proprietorship were the twin bases of his authority in Britain. The land of Wales had come ‘into the lordship of our possession’ and had been ‘annexed and united to the crown of the said kingdom as part of the said body’. As for Scotland, it was ‘subjected by right of ownership to our power’ and to his ‘right and full dominion…by reason of property and possession.’

In the process the latent high kingship of earlier days - be it the stage-managed submissions of Henry II’s day or the apparently genial ceremonies of 1278 - was being transformed into a more direct authority. Terminology and titles made the point crisply. Wales and Scotland in succession lost their princely and kingly status; both now came to be described simply and pointedly as ‘lands’. The title of prince of Wales was adopted, or usurped, for the English king’s eldest son as heir apparent to the crown of England. Though Edward I was occasionally referred to as ‘king of England and Scotland’, in reality the kingship of the Scots was in suspense for rebellion, subsumed in effect within the crown of England as that of its sovereign lord. If to that we added the title lord of Ireland, then Edward I was now in 1305 in truth, if not in name, king of the British Isles, ‘our realm’, as he occasionally referred to it, if only implicitly, in the singular.”

“Never had the presence of English power, be it in the person of the king himself or that of his appointed representatives…been so ubiquitously and awesomely present in the outer zones of the British Isles as in the last fifteen years or so of Edward I’s reign.

It was, of course, the triumph of power; contemporaries were not short of saying so. Sometimes they said it crudely: the magnates had bragged that England could exterminate Scotland without any external help. ‘What matter if both the Welsh and Scots are our foes?’ so Edward I is alleged to have boasted. ‘Let them join forces if they please. We shall beat them both in a single day.’ These statements may have been made, as we would say, off the record, but even on the record Edward I’s language made no bones of the fact that in this instance might was right. Power and proprietorship were the twin bases of his authority in Britain. The land of Wales had come ‘into the lordship of our possession’ and had been ‘annexed and united to the crown of the said kingdom as part of the said body’. As for Scotland, it was ‘subjected by right of ownership to our power’ and to his ‘right and full dominion…by reason of property and possession.’

In the process the latent high kingship of earlier days - be it the stage-managed submissions of Henry II’s day or the apparently genial ceremonies of 1278 - was being transformed into a more direct authority. Terminology and titles made the point crisply. Wales and Scotland in succession lost their princely and kingly status; both now came to be described simply and pointedly as ‘lands’. The title of prince of Wales was adopted, or usurped, for the English king’s eldest son as heir apparent to the crown of England. Though Edward I was occasionally referred to as ‘king of England and Scotland’, in reality the kingship of the Scots was in suspense for rebellion, subsumed in effect within the crown of England as that of its sovereign lord. If to that we added the title lord of Ireland, then Edward I was now in 1305 in truth, if not in name, king of the British Isles, ‘our realm’, as he occasionally referred to it, if only implicitly, in the singular.”

Published on June 14, 2019 00:27

June 13, 2019

Author interview

Today I am interviewed by Dan Moorhouse on his website, SchoolsHistory.Org. I talk about my new novella, Longsword (IV) The Hooded Men as well as my thoughts on history and life as a writer in general. My piercing shafts of insight and stupendous witty brilliance are not to be missed, along with my humility.

Interview with David Pilling

Interview with David Pilling

Published on June 13, 2019 01:22

June 12, 2019

Adam's last stand

In the summer of 1301 Edward I embarked on another grand attempt to move his drinks cabinet six inches closer to Stirling. His plans for the campaign were much more ambitious than previous efforts. Rather than one army marching into Scotland, two would invade at once. The king himself would advance from Berwick, while a second host under the nominal command of Prince Edward (but in practice the Earl of Lincoln) marched from Carlisle. The idea was to crush the Scottish field army in a pincer movement.

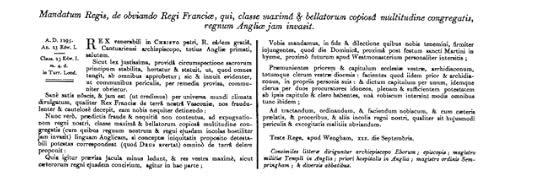

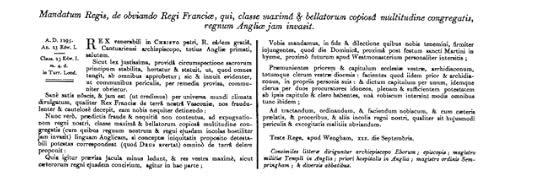

The military summonses were issued in February and March and the musters fixed for 24 June. It seems barely credible that Adam Gurdun would be called up yet again: after the siege of Caerlaverock in the previous year he had returned to Hampshire, where he might have expected to enjoy his few remaining years in peace. But there he is on the writ, summoned to join the muster of the king’s army at Berwick on the Nativity of St John the Baptist (24 June). The writ insists that Adam must serve in person, which is intriguing. A knight of his advanced years - he was probably about 85 at this point - could hardly be expected to do very much. No doubt his experience was useful, or perhaps King Edward simply liked the company of old friends. Along with Earl Warenne and the Earl of Lincoln, Adam was one of a dwindling band of survivors from the Montfortian era.

The campaign itself was not very eventful. The king’s army marched from Berwick along the line of the Tweed and reached Coldstream on 21 July. From there Edward advanced to Peebles via Kelso and Traquair. By the end of August he had reached Glasgow, where preparations were made for an attack on Bothwell Castle. He wanted the ‘chief honour of taming the pride of the Scots’ to go to his son, advancing from Carlisle, but the Scots refused battle. Instead the main Scottish army withdrew beyond the Forth, though there was some skirmishing around Ayr and Turnberry. On 2 September the king received the good news that his son had taken Turnberry Castle, and oblations were given in thanks at Glasgow Cathedral.

Adam performed his final military service at the siege of Bothwell in September 1301. This was one of the greatest of Scottish castles, with a large circular donjon, possibly modelled on that at Coucy in Picardy. A great movable siege tower, called Belfry, was dragged up a corduroy road from Glasgow and covered with thick hides as a protection against fire. The assault led to Bothwell’s surrender on 21 September and the English army disbanded at Dunipace on 29 September. The siege tower was then dragged up to Stirling, but no assault took place as King Edward, due to French pressure, agreed to a truce in January 1302.

The truce was only temporary, but it marked the end of Adam’s military career. After fifty-nine years of service, a period of outlawry and eight major campaigns, he was finally allowed to go home and rest.

The military summonses were issued in February and March and the musters fixed for 24 June. It seems barely credible that Adam Gurdun would be called up yet again: after the siege of Caerlaverock in the previous year he had returned to Hampshire, where he might have expected to enjoy his few remaining years in peace. But there he is on the writ, summoned to join the muster of the king’s army at Berwick on the Nativity of St John the Baptist (24 June). The writ insists that Adam must serve in person, which is intriguing. A knight of his advanced years - he was probably about 85 at this point - could hardly be expected to do very much. No doubt his experience was useful, or perhaps King Edward simply liked the company of old friends. Along with Earl Warenne and the Earl of Lincoln, Adam was one of a dwindling band of survivors from the Montfortian era.

The campaign itself was not very eventful. The king’s army marched from Berwick along the line of the Tweed and reached Coldstream on 21 July. From there Edward advanced to Peebles via Kelso and Traquair. By the end of August he had reached Glasgow, where preparations were made for an attack on Bothwell Castle. He wanted the ‘chief honour of taming the pride of the Scots’ to go to his son, advancing from Carlisle, but the Scots refused battle. Instead the main Scottish army withdrew beyond the Forth, though there was some skirmishing around Ayr and Turnberry. On 2 September the king received the good news that his son had taken Turnberry Castle, and oblations were given in thanks at Glasgow Cathedral.

Adam performed his final military service at the siege of Bothwell in September 1301. This was one of the greatest of Scottish castles, with a large circular donjon, possibly modelled on that at Coucy in Picardy. A great movable siege tower, called Belfry, was dragged up a corduroy road from Glasgow and covered with thick hides as a protection against fire. The assault led to Bothwell’s surrender on 21 September and the English army disbanded at Dunipace on 29 September. The siege tower was then dragged up to Stirling, but no assault took place as King Edward, due to French pressure, agreed to a truce in January 1302.

The truce was only temporary, but it marked the end of Adam’s military career. After fifty-nine years of service, a period of outlawry and eight major campaigns, he was finally allowed to go home and rest.

Published on June 12, 2019 05:39

The Hooded Men are here!

My new book, Longsword (IV) The Hooded Men, is now available on Amazon Kindle. This is the latest adventure of Hugh Longsword - soldier, agent, spy and loyal King's Man in the reign of Edward I.

"England, 1273 AD. Henry III is dead. The new king, Edward I, is thousands of miles away in the Holy Land. In his absence, old enemies plan to shatter the fragile peace and plunge England into another civil war. Robert Ferrers, the outlawed Earl of Derby and Edward’s bitter enemy, raises the standard of revolt. He gathers an army of outlaws and secretly dreams of seizing the crown itself.

Hugh Longsword arrives home in disgrace after his failure to protect Edward from an assassin’s blade. He is given one chance to redeem himself and sent to investigate disturbances in northern England. The scale of the conspiracy soon becomes apparent as Hugh encounters enemies old and new: Sir John d’Eyvill, the outlaws of Sherwood, and a mysterious knight who calls himself the King of the North Wind.

Longsword IV: The Hooded Men is the latest historical adventure novel by David Pilling, author of Reiver, Soldier of Fortune, The Half-Hanged Man, Caesar’s Sword and many more novels and short stories."

The Hooded Men on Amazon US

The Hooded Men on Amazon UK

"England, 1273 AD. Henry III is dead. The new king, Edward I, is thousands of miles away in the Holy Land. In his absence, old enemies plan to shatter the fragile peace and plunge England into another civil war. Robert Ferrers, the outlawed Earl of Derby and Edward’s bitter enemy, raises the standard of revolt. He gathers an army of outlaws and secretly dreams of seizing the crown itself.

Hugh Longsword arrives home in disgrace after his failure to protect Edward from an assassin’s blade. He is given one chance to redeem himself and sent to investigate disturbances in northern England. The scale of the conspiracy soon becomes apparent as Hugh encounters enemies old and new: Sir John d’Eyvill, the outlaws of Sherwood, and a mysterious knight who calls himself the King of the North Wind.

Longsword IV: The Hooded Men is the latest historical adventure novel by David Pilling, author of Reiver, Soldier of Fortune, The Half-Hanged Man, Caesar’s Sword and many more novels and short stories."

The Hooded Men on Amazon US

The Hooded Men on Amazon UK

Published on June 12, 2019 01:10

June 11, 2019

Adam does Galloway

At the end of December 1299 Edward I issued a summons for the feudal service to muster at Carlisle in the summer of the following year. The roll recording the response to this request shows that the unpaid service of forty knights and 366 sergeants was provided. Among them was - you guessed it - that man Sir Adam Gurdun, summoned under the general writ to perform military service against the Scots.

Adam had never served in Scotland before. It probably didn’t bother him very much: he was well into his eighties, and fifty-eight years had passed since he first saw action in Poitou. In 1255 Henry III had granted him exemption from military service, on condition he sent a sergeant to fight in his stead. Not once, in over half a century of campaigning, had Adam taken the easy option. Now this old, old man - certainly by the standards of the day - once again heaved his guts into the saddle, took spear in fist and went plodding off to fight the enemies of the lord king.

Adam had never served in Scotland before. It probably didn’t bother him very much: he was well into his eighties, and fifty-eight years had passed since he first saw action in Poitou. In 1255 Henry III had granted him exemption from military service, on condition he sent a sergeant to fight in his stead. Not once, in over half a century of campaigning, had Adam taken the easy option. Now this old, old man - certainly by the standards of the day - once again heaved his guts into the saddle, took spear in fist and went plodding off to fight the enemies of the lord king.

He was ordered to attend the general muster at Carlisle on 24th June 1300. There the cavalry forces were divided into four batailles or squadrons. Those performing feudal service, including Adam, either formed their own bataille or were integrated into the army as a whole. Within each bataille there were fifteen or twenty bannerets, each in command of a retinue of knights or squires. A total of 16,000 infantry were requested, but only 9000 turned up.

The main objective of the campaign was to march into Galloway and take Caerlaverock Castle, to ease the pressure on the English garrison at Lochmaben. Thus the army lumbered into southwest Scotland, in heavy rains, and sat down before Caerlaverock. An unknown herald or jongleur composed a long poem about the siege, praising the splendid appearance and brave deeds of Edward’s knights. He also supplied a vivid description of the castle:

“Shield-shaped, was it. corner-towered, gate and draw-bridge barbican’d. strongly walled, and girt with ditches filled with water brimmingly. Ne’er was castle lovelier sited : westward lay the Irish Sea, north a countryside of beauty by an arm of sea embraced. On two sides, whoe’er approached it danger from the waters faced; nor was easier the southward — sea-girt land of marsh and wood: therefore from the east we neared it, up the slope on which it stood.”

Adam had never served in Scotland before. It probably didn’t bother him very much: he was well into his eighties, and fifty-eight years had passed since he first saw action in Poitou. In 1255 Henry III had granted him exemption from military service, on condition he sent a sergeant to fight in his stead. Not once, in over half a century of campaigning, had Adam taken the easy option. Now this old, old man - certainly by the standards of the day - once again heaved his guts into the saddle, took spear in fist and went plodding off to fight the enemies of the lord king.

Adam had never served in Scotland before. It probably didn’t bother him very much: he was well into his eighties, and fifty-eight years had passed since he first saw action in Poitou. In 1255 Henry III had granted him exemption from military service, on condition he sent a sergeant to fight in his stead. Not once, in over half a century of campaigning, had Adam taken the easy option. Now this old, old man - certainly by the standards of the day - once again heaved his guts into the saddle, took spear in fist and went plodding off to fight the enemies of the lord king.He was ordered to attend the general muster at Carlisle on 24th June 1300. There the cavalry forces were divided into four batailles or squadrons. Those performing feudal service, including Adam, either formed their own bataille or were integrated into the army as a whole. Within each bataille there were fifteen or twenty bannerets, each in command of a retinue of knights or squires. A total of 16,000 infantry were requested, but only 9000 turned up.

The main objective of the campaign was to march into Galloway and take Caerlaverock Castle, to ease the pressure on the English garrison at Lochmaben. Thus the army lumbered into southwest Scotland, in heavy rains, and sat down before Caerlaverock. An unknown herald or jongleur composed a long poem about the siege, praising the splendid appearance and brave deeds of Edward’s knights. He also supplied a vivid description of the castle:

“Shield-shaped, was it. corner-towered, gate and draw-bridge barbican’d. strongly walled, and girt with ditches filled with water brimmingly. Ne’er was castle lovelier sited : westward lay the Irish Sea, north a countryside of beauty by an arm of sea embraced. On two sides, whoe’er approached it danger from the waters faced; nor was easier the southward — sea-girt land of marsh and wood: therefore from the east we neared it, up the slope on which it stood.”

Published on June 11, 2019 09:51

Adam Gurdun: Like a Rolling Stone

And he just keeps a-rollin’. In 1297, two years after his appointment as custos of the Hampshire coast, Adam was once again summoned to his duty. The threat of French invasion had faded, but now civil war was in the air: a band of disgruntled Marcher barons had held their own unofficial ‘parliament’ in the Wyre Forest, in protest against Edward I’s grinding war taxes, and there were rumours of a rebel army gathering in the west.

With King Edward in Flanders, an emergency royal council was summoned to meet at Rochester. Adam Gurdun was among 220 knights ordered to attend the council with horses and arms on 8 September. These men were chosen for their loyalty to the king, and included many veterans of the Welsh wars. Eight days later Adam was back in Hampshire as a commissioner of array, raising troops to fight against fellow Englishmen. Presumably he knew nothing of the Battle of Stirling Bridge, fought on 11 September, where Andrew Murray and William Wallace won their famous victory over Earl Warenne. On 28 October the rebel earls appeared before the gates of London at the head of 1500 cavalry, nearly as many as fought at Falkirk the following year. They demanded entrance to the city and confirmation of the charters. In response the council summoned more knights from Kent and dared the earls to do their worst. For a few days England hovered on the brink.

With King Edward in Flanders, an emergency royal council was summoned to meet at Rochester. Adam Gurdun was among 220 knights ordered to attend the council with horses and arms on 8 September. These men were chosen for their loyalty to the king, and included many veterans of the Welsh wars. Eight days later Adam was back in Hampshire as a commissioner of array, raising troops to fight against fellow Englishmen. Presumably he knew nothing of the Battle of Stirling Bridge, fought on 11 September, where Andrew Murray and William Wallace won their famous victory over Earl Warenne. On 28 October the rebel earls appeared before the gates of London at the head of 1500 cavalry, nearly as many as fought at Falkirk the following year. They demanded entrance to the city and confirmation of the charters. In response the council summoned more knights from Kent and dared the earls to do their worst. For a few days England hovered on the brink.

At this point Adam did something remarkable. He was pushing 80, a respected soldier and county knight, but not in the top tier of magnates; he didn’t even hold any castles. Yet, on 10 October, he appeared before the council in London and offered to act as mediator between King Edward and the rebel barons: the writ states he engaged to ‘induce the King to remit his displeasure against the Earls of Hereford and Norfolk and John de Ferrers’. From this it appears Adam had some moderating influence over the king, implying a personal relationship between the old Montfortian and the prince he fought to a standstill in the Hampshire forests, thirty years past.

Whether Adam travelled to Flanders, or met Edward at Winchelsea when he returned to England in March the following year, is unknown. Ironically, the threat of civil war in England was averted by the Scottish victory at Stirling Bridge, which united the baronage behind their king. Adam is not listed among the great muster of English knight-service for the Falkirk campaign, but his fighting days were not done.

With King Edward in Flanders, an emergency royal council was summoned to meet at Rochester. Adam Gurdun was among 220 knights ordered to attend the council with horses and arms on 8 September. These men were chosen for their loyalty to the king, and included many veterans of the Welsh wars. Eight days later Adam was back in Hampshire as a commissioner of array, raising troops to fight against fellow Englishmen. Presumably he knew nothing of the Battle of Stirling Bridge, fought on 11 September, where Andrew Murray and William Wallace won their famous victory over Earl Warenne. On 28 October the rebel earls appeared before the gates of London at the head of 1500 cavalry, nearly as many as fought at Falkirk the following year. They demanded entrance to the city and confirmation of the charters. In response the council summoned more knights from Kent and dared the earls to do their worst. For a few days England hovered on the brink.

With King Edward in Flanders, an emergency royal council was summoned to meet at Rochester. Adam Gurdun was among 220 knights ordered to attend the council with horses and arms on 8 September. These men were chosen for their loyalty to the king, and included many veterans of the Welsh wars. Eight days later Adam was back in Hampshire as a commissioner of array, raising troops to fight against fellow Englishmen. Presumably he knew nothing of the Battle of Stirling Bridge, fought on 11 September, where Andrew Murray and William Wallace won their famous victory over Earl Warenne. On 28 October the rebel earls appeared before the gates of London at the head of 1500 cavalry, nearly as many as fought at Falkirk the following year. They demanded entrance to the city and confirmation of the charters. In response the council summoned more knights from Kent and dared the earls to do their worst. For a few days England hovered on the brink.

At this point Adam did something remarkable. He was pushing 80, a respected soldier and county knight, but not in the top tier of magnates; he didn’t even hold any castles. Yet, on 10 October, he appeared before the council in London and offered to act as mediator between King Edward and the rebel barons: the writ states he engaged to ‘induce the King to remit his displeasure against the Earls of Hereford and Norfolk and John de Ferrers’. From this it appears Adam had some moderating influence over the king, implying a personal relationship between the old Montfortian and the prince he fought to a standstill in the Hampshire forests, thirty years past.

Whether Adam travelled to Flanders, or met Edward at Winchelsea when he returned to England in March the following year, is unknown. Ironically, the threat of civil war in England was averted by the Scottish victory at Stirling Bridge, which united the baronage behind their king. Adam is not listed among the great muster of English knight-service for the Falkirk campaign, but his fighting days were not done.

Published on June 11, 2019 05:22

June 10, 2019

And now for something...

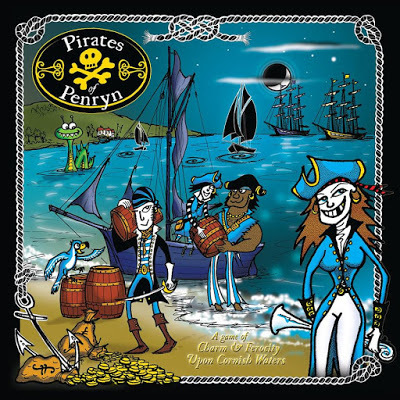

…completely different. Let’s fast-forward a few hundred years and row west to Cornwall, a notorious den of smugglers and pirates.

For centuries any British ship coming back from Spain to the Downs had to pass the rugged coast of Cornwall, immortalised in the old naval tune, Spanish Ladies:

“We’ll rant and we’ll roar like true British sailors,

We’ll rant and we’ll roar all along the salt sea,

Until we strike soundings in the Channel of Old England,

From Ushant to Scilly is thirty five leagues.”

Now you can recreate the golden age of piracy west of the Tamar, complete with parrots, doubloons, galleons, barrels of creatively imported contraband and robbery on the high seas. Oh, and sea monsters. The Pirates of Penryn, the debut project of SeaGriffin Games Ltd, has sailed onto the market courtesy of the creative duo, Cait and Matt.

Exercise your charm - or lack of it - and ferocity in Cornish waters; whet those cutlasses, prime your muskets, spit the Devil in the eye and teach that parrot to dance.

You heard me, sea-dogs. Switch the telly off, crush your phone under your heel, exorcise all those boiling inner hatreds and resentments by blowing your entire family to hell with a 64-cannon broadside! Failing that, set a slavering sea-beast upon them and laugh and clap as hubby or daddy - whoever is irritating you most - vanishes down a slimy reptilian gullet. After all, you’re never too old to play pirates.

Below is a link to the Pirates of Penryn online store, where you can learn more about the game and its creators, as well as order the game via Ye Old Shoppe.

Welcome Aboard - the Pirates of Penryn.com

For centuries any British ship coming back from Spain to the Downs had to pass the rugged coast of Cornwall, immortalised in the old naval tune, Spanish Ladies:

“We’ll rant and we’ll roar like true British sailors,

We’ll rant and we’ll roar all along the salt sea,

Until we strike soundings in the Channel of Old England,

From Ushant to Scilly is thirty five leagues.”

Now you can recreate the golden age of piracy west of the Tamar, complete with parrots, doubloons, galleons, barrels of creatively imported contraband and robbery on the high seas. Oh, and sea monsters. The Pirates of Penryn, the debut project of SeaGriffin Games Ltd, has sailed onto the market courtesy of the creative duo, Cait and Matt.

Exercise your charm - or lack of it - and ferocity in Cornish waters; whet those cutlasses, prime your muskets, spit the Devil in the eye and teach that parrot to dance.

You heard me, sea-dogs. Switch the telly off, crush your phone under your heel, exorcise all those boiling inner hatreds and resentments by blowing your entire family to hell with a 64-cannon broadside! Failing that, set a slavering sea-beast upon them and laugh and clap as hubby or daddy - whoever is irritating you most - vanishes down a slimy reptilian gullet. After all, you’re never too old to play pirates.

Below is a link to the Pirates of Penryn online store, where you can learn more about the game and its creators, as well as order the game via Ye Old Shoppe.

Welcome Aboard - the Pirates of Penryn.com

Published on June 10, 2019 06:03

Adam Gurdun: Quite Possibly Indestructible

In October 1295, eight years after his last military service in Wales, Adam Gurdun was summoned once again to serve his king.

This time he was placed in charge of the defence of Hampshire, part of the chain of coastal defences hurriedly set up against the threat of a French invasion. Adam was appointed ‘custos’ of the Hampshire coast, while similar power was given to Henry of Cobham for Kent and William Stoke for the rapes of Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings.

The threat of invasion was very real. Philip le Bel had brought ship-builders from Genoa to build galleys in Marseille and in Normandy, and in 1295 a squadron sailed from the Mediterranean to invade England. In August a French raiding party landed at Dover and set fire to the town, killing two monks of the priory. An assault on Winchelsea was beaten off, and a French galley foundered on some rocks when it tried to attack Hythe. All along the southern coast, alarm bells were ringing. From his base at Wingham in Kent, King Edward declared the French intended to wipe the English language from the face of the earth. His emphasis on the language - English, not Norman-French or domestic variants - suggests the upper classes in England no longer despised the native tongue.

Adam, now in his 70s, was given total responsibility for mustering soldiers and organising the defence of Hampshire. From his headquarters at Portsmouth, he was in command of a licensed private army. The old knight went about his task with relish: within days he had organised a general mobilisation of all able-bodied men, and come up with a detailed plan for the defence of his section of coastline.

The coastal defence scheme for Hampshire survives in its entirety. Adam’s defences consisted of a strong garrison on the Isle of Wight, with the mainland beaches along the Solent and Spithead and the Southampton Water guarded by infantry. These men were drawn from seaside villages and inland hundreds as a first line of defense. Behind them was a mobile reserve of cavalry. If the French attempted to land on the mainland, they would be outflanked by the garrison on the Isle. If they tried to attack the Isle, they would be bottled up by Adam’s forces on the mainland and ships from the Cinque Ports.

Adam also set about raising the landholders of the region. Everyone in Hampshire who could afford to raise men was summoned in Hampshire, to be ‘assessed for horses and arms’. The Bishop of Winchester was assessed for one hundred covered horsemen, the Prior of St Swithin for ten, the Abbot of Waverley at four, the Abbot of Hyde for six, and so on. More cavalry were distributed among Hurst Castle, Portsmouth, and the Isle of Wight. All told, some 246 mounted men were named and tapped for service with horses and arms in defence of Hampshire.

This time he was placed in charge of the defence of Hampshire, part of the chain of coastal defences hurriedly set up against the threat of a French invasion. Adam was appointed ‘custos’ of the Hampshire coast, while similar power was given to Henry of Cobham for Kent and William Stoke for the rapes of Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings.

The threat of invasion was very real. Philip le Bel had brought ship-builders from Genoa to build galleys in Marseille and in Normandy, and in 1295 a squadron sailed from the Mediterranean to invade England. In August a French raiding party landed at Dover and set fire to the town, killing two monks of the priory. An assault on Winchelsea was beaten off, and a French galley foundered on some rocks when it tried to attack Hythe. All along the southern coast, alarm bells were ringing. From his base at Wingham in Kent, King Edward declared the French intended to wipe the English language from the face of the earth. His emphasis on the language - English, not Norman-French or domestic variants - suggests the upper classes in England no longer despised the native tongue.

Adam, now in his 70s, was given total responsibility for mustering soldiers and organising the defence of Hampshire. From his headquarters at Portsmouth, he was in command of a licensed private army. The old knight went about his task with relish: within days he had organised a general mobilisation of all able-bodied men, and come up with a detailed plan for the defence of his section of coastline.

The coastal defence scheme for Hampshire survives in its entirety. Adam’s defences consisted of a strong garrison on the Isle of Wight, with the mainland beaches along the Solent and Spithead and the Southampton Water guarded by infantry. These men were drawn from seaside villages and inland hundreds as a first line of defense. Behind them was a mobile reserve of cavalry. If the French attempted to land on the mainland, they would be outflanked by the garrison on the Isle. If they tried to attack the Isle, they would be bottled up by Adam’s forces on the mainland and ships from the Cinque Ports.

Adam also set about raising the landholders of the region. Everyone in Hampshire who could afford to raise men was summoned in Hampshire, to be ‘assessed for horses and arms’. The Bishop of Winchester was assessed for one hundred covered horsemen, the Prior of St Swithin for ten, the Abbot of Waverley at four, the Abbot of Hyde for six, and so on. More cavalry were distributed among Hurst Castle, Portsmouth, and the Isle of Wight. All told, some 246 mounted men were named and tapped for service with horses and arms in defence of Hampshire.

Published on June 10, 2019 03:47

June 9, 2019

Bang!

Captain Richard Atkyns shoots Sir Arthur Haselrigge in the head at the battle of Roundway Down, 13 July 1643. Atkyns wrote about the incident in his journal:

"He discharged his carbine first, but at a distance not to hurt us, and afterwards one of his pistols, before I came up to him and missed with both: I then immediately struck into him, and touched him before I discharged mine; and I'm sure I hit him, for he staggered, and presently wheeled off from his party and ran. I came up to him, and discharged the other pistol at him, and I'm sure I hit his head, for I touched it before I gave fire."

Fortunately for Sir Arthur, his armour was so thick all the bullets and swords bounced off. After Atkyns shot his horse Arthur tried to surrender, but was rescued while fumbling with his sword, which was tied to his wrist. When he heard of the incident Charles I cracked one of his few recorded jokes: the king remarked that if Haselrig had been as well supplied as he was fortified he could have withstood a siege.

Boom! Boom!

Published on June 09, 2019 10:01

Miracles of Dryslwyn

The siege of Dryslwyn Castle in the summer of 1287 was notable for the sheer mass of soldiery gathered under its walls: upward of thirty thousand men, English and Welsh, in a camp that must have resembled a small city. God knows how they were all fed.

God was present in other forms. From an English perspective, the siege gives us an interesting - and rare - insight into the thoughts of ordinary soldiers. By the end of July 1800 English infantry were mustered at Hereford, prior to marching on Dryslwyn. At this point strange things started to happen. Hereford Cathedral contained the tomb of Thomas de Cantilupe, bishop of Hereford (1275-82), one of the most popular saints in medieval England. Between 1287-1404, no less than 460 miracles were attested at his shrine.

The stress of the campaign ahead seems to have affected the minds of Earl Edmund’s soldiers. One of his knights, Ralph Abecoft, discovered his falcon lying dead outside his lodgings. He followed the English custom of bending a penny over the dead bird’s head, as a votive offering to the saint, and commended it to Cantilupe and God. The falcon suddenly revived and was taken to Cantilupe’s shrine in the north transept of the cathedral. There it attracted an awestruck crowd, including Earl Edmund himself and a great number of lords and knights. Another miracle was experienced by Roger, a cleric of Cirencester. He claimed that his hands were crippled by God after he publicly slandered Cantilupe’s memory; then he came to the Hereford shrine in penitence, placed his hands on the tomb and - lo! - they were instantly healed.

News of these miracles spread among the troops. On the vigil of St Margaret the Virgin (20 July) John de Havering sent one of his men, a youth named John, to the shrine in the hope that he would be cured of deafness. John was cured in front of all present that day. At the end of July Edmund’s army had marched through Usk into Newport. In mid-August the forces of Edmund and Havering converged and laid siege to Dryslwyn. During the three weeks of siege more miracles were reported. At one point a soldier of Herefordshire, Ralph Boteler, was shot under the eye by a Welsh archer; the arrow hit him with such force ‘the arrowhead became horribly fixed deep inside his head’. Ralph signed himself with the cross, and he and his friends invoked the power of the saint. Ralph not only survived but kept his eye as well. St Thomas was called upon again when a mine collapsed under the wall, burying many men alive, including several knights. As the survivors fled, the Welsh fell upon them. Two knights only escaped through the ‘invocation and aid of Saint Thomas’. Another was buried so deep under the heap of mortar and soil only his foot stuck out. One of his men called upon the saint and was suddenly gifted superhuman strength; he dragged his master clear of the rubble ‘with wonderful ease’.

One final miracle was reported at Dryslwyn. After the castle fell in the autumn it was granted to Alan Plukenet. The following year his son, Alan junior, was rearing a goat as a pet. The animal fell from the battlements and was broken all to pieces: “With one of its legs having been broken, even its innards spewed out. The blood of its body spurted through various courses”. A crowd of local people gathered to mourn the goat, and promised to make offerings to God and Cantilupe if the animal could be restored to life. Since the locals were Welsh, this suggests the saint had become popular with them as well. “And behold! The little creature at once got up, alive and healthy, and immediately took food with many looking on amazed and praising the Lord”.

God was present in other forms. From an English perspective, the siege gives us an interesting - and rare - insight into the thoughts of ordinary soldiers. By the end of July 1800 English infantry were mustered at Hereford, prior to marching on Dryslwyn. At this point strange things started to happen. Hereford Cathedral contained the tomb of Thomas de Cantilupe, bishop of Hereford (1275-82), one of the most popular saints in medieval England. Between 1287-1404, no less than 460 miracles were attested at his shrine.

The stress of the campaign ahead seems to have affected the minds of Earl Edmund’s soldiers. One of his knights, Ralph Abecoft, discovered his falcon lying dead outside his lodgings. He followed the English custom of bending a penny over the dead bird’s head, as a votive offering to the saint, and commended it to Cantilupe and God. The falcon suddenly revived and was taken to Cantilupe’s shrine in the north transept of the cathedral. There it attracted an awestruck crowd, including Earl Edmund himself and a great number of lords and knights. Another miracle was experienced by Roger, a cleric of Cirencester. He claimed that his hands were crippled by God after he publicly slandered Cantilupe’s memory; then he came to the Hereford shrine in penitence, placed his hands on the tomb and - lo! - they were instantly healed.

News of these miracles spread among the troops. On the vigil of St Margaret the Virgin (20 July) John de Havering sent one of his men, a youth named John, to the shrine in the hope that he would be cured of deafness. John was cured in front of all present that day. At the end of July Edmund’s army had marched through Usk into Newport. In mid-August the forces of Edmund and Havering converged and laid siege to Dryslwyn. During the three weeks of siege more miracles were reported. At one point a soldier of Herefordshire, Ralph Boteler, was shot under the eye by a Welsh archer; the arrow hit him with such force ‘the arrowhead became horribly fixed deep inside his head’. Ralph signed himself with the cross, and he and his friends invoked the power of the saint. Ralph not only survived but kept his eye as well. St Thomas was called upon again when a mine collapsed under the wall, burying many men alive, including several knights. As the survivors fled, the Welsh fell upon them. Two knights only escaped through the ‘invocation and aid of Saint Thomas’. Another was buried so deep under the heap of mortar and soil only his foot stuck out. One of his men called upon the saint and was suddenly gifted superhuman strength; he dragged his master clear of the rubble ‘with wonderful ease’.

One final miracle was reported at Dryslwyn. After the castle fell in the autumn it was granted to Alan Plukenet. The following year his son, Alan junior, was rearing a goat as a pet. The animal fell from the battlements and was broken all to pieces: “With one of its legs having been broken, even its innards spewed out. The blood of its body spurted through various courses”. A crowd of local people gathered to mourn the goat, and promised to make offerings to God and Cantilupe if the animal could be restored to life. Since the locals were Welsh, this suggests the saint had become popular with them as well. “And behold! The little creature at once got up, alive and healthy, and immediately took food with many looking on amazed and praising the Lord”.

Published on June 09, 2019 04:44