David Pilling's Blog, page 58

June 9, 2019

Adam Gurdun: He Just Will Not Stop

In 1287, ten years after his last Welsh adventure, Adam Gurdun was once again summoned to fight in Wales. This time the enemy was Rhys ap Maredudd, lord of Dryslwyn and once a staunch ally of the English. Rhys had fallen out with King Edward's administrators in West Wales and gone into revolt, slaughtering the garrisons at Carreg Cennen and Llandovery and ravaging up to the gates of Carmarthen.

Adam, now in his sixth decade, once again strapped on that damned dirty armour and clambered aboard his war-horse. The king was in Gascony, so the Welsh campaign was organised by the regent, Edmund of Cornwall. Cornwall summoned Adam to appear 'with horses and arms' at the great military council held at Gloucester on 15 July. The council at Gloucester resolved to raise a single 'great army' to converge on Carmarthen before marching on Rhys's fortress of Dryslwyn in the Tywi valley. It was assembled in four divisions, at Llanbadarn Fawr under John Havering, at Monmouth under Earl Edmund, Brecon under Gilbert de Clare and local forces under the justiciar, Robert Tibetot.

Adam was presumably at Monmouth with Edmund, who raised 11,000 men: two-thirds of these came from the counties of Carmarthen and Cardigan and the Marches, the rest were English. Had he known of it, the king might have been alarmed at the excessive scale of the regent's preparations. The army at Llanbadarn consisted of 4640 men, half Welsh and half English; these included 1000 men of Powys under Owain de le Pole, and 2000 men from North Wales raised by the Sheriff of Meirionydd. More men came from Cheshire and North Wales, swelling the army to 6660. Not to be outdone, the Earl of Gloucester raised a staggering 12,500 men from his lordship of Brecon.

In all, the regent's army was well in excess of 22,000 men. This was the largest host seen in the British Isles since 1066, largely composed of Welsh infantry, and all to lay siege to a single castle. To put these baffling numbers into context, the last royal army to campaign in West Wales in 1283 never exceeded 3000 men. If nothing else, Cornwall's panic attack does at least show the sheer number of fighting men that could be raised in Wales at this time.

Adam, now in his sixth decade, once again strapped on that damned dirty armour and clambered aboard his war-horse. The king was in Gascony, so the Welsh campaign was organised by the regent, Edmund of Cornwall. Cornwall summoned Adam to appear 'with horses and arms' at the great military council held at Gloucester on 15 July. The council at Gloucester resolved to raise a single 'great army' to converge on Carmarthen before marching on Rhys's fortress of Dryslwyn in the Tywi valley. It was assembled in four divisions, at Llanbadarn Fawr under John Havering, at Monmouth under Earl Edmund, Brecon under Gilbert de Clare and local forces under the justiciar, Robert Tibetot.

Adam was presumably at Monmouth with Edmund, who raised 11,000 men: two-thirds of these came from the counties of Carmarthen and Cardigan and the Marches, the rest were English. Had he known of it, the king might have been alarmed at the excessive scale of the regent's preparations. The army at Llanbadarn consisted of 4640 men, half Welsh and half English; these included 1000 men of Powys under Owain de le Pole, and 2000 men from North Wales raised by the Sheriff of Meirionydd. More men came from Cheshire and North Wales, swelling the army to 6660. Not to be outdone, the Earl of Gloucester raised a staggering 12,500 men from his lordship of Brecon.

In all, the regent's army was well in excess of 22,000 men. This was the largest host seen in the British Isles since 1066, largely composed of Welsh infantry, and all to lay siege to a single castle. To put these baffling numbers into context, the last royal army to campaign in West Wales in 1283 never exceeded 3000 men. If nothing else, Cornwall's panic attack does at least show the sheer number of fighting men that could be raised in Wales at this time.

Published on June 09, 2019 01:36

Announcement...announcement...announcement...

So to preen and swagger and boast for a moment, I've been offered a contract to write a biography of Dafydd ap Gruffudd. There hasn't been one, so far as I know: he tends to appear as an important supporting player, but has never had a bio of his own.

Dafydd is obviously a 'controversial' figure, and digging into his psyche will be an interesting exercise. This morning I read the following snippet by the late Tony Carr:

"Dafydd's role has also given rise to debate; the fact that he changed sides in 1263 and again in 1274 may suggest a lack of loyalty but it is also possible that these changes of allegiance were the result of a fundamental disagreement of an able man with policies which he saw as putting the principality and his inheritance in jeopardy. It is certainly simplistic to see Dafydd as Llywelyn's evil genius."

So has Dafydd been misunderstood? Was he no 'traitor' after all, but a man of long-term vision who saw that Llywelyn was leading Wales straight over a cliff? Interestingly, I also picked up a copy of Martin Johnes' recent book, Wales: England's Colony, and that is pretty much the criticism he aims at Llywelyn.

Dafydd is obviously a 'controversial' figure, and digging into his psyche will be an interesting exercise. This morning I read the following snippet by the late Tony Carr:

"Dafydd's role has also given rise to debate; the fact that he changed sides in 1263 and again in 1274 may suggest a lack of loyalty but it is also possible that these changes of allegiance were the result of a fundamental disagreement of an able man with policies which he saw as putting the principality and his inheritance in jeopardy. It is certainly simplistic to see Dafydd as Llywelyn's evil genius."

So has Dafydd been misunderstood? Was he no 'traitor' after all, but a man of long-term vision who saw that Llywelyn was leading Wales straight over a cliff? Interestingly, I also picked up a copy of Martin Johnes' recent book, Wales: England's Colony, and that is pretty much the criticism he aims at Llywelyn.

Published on June 09, 2019 00:49

June 8, 2019

Fair pleading

Word of the day: beau pleader or a writ, whereby it is provided that no fine shall be taken of anyone in any court for fair pleading, i.e. for not pleading aptly, and to the purpose.

The act of beaupleader was passed in the First Statute of Westminster (1275) and meant to prevent sheriffs imposing arbitrary fines on advocates in court who spoke badly. The act was revoked in England and Wales in 1863 and Ireland in 1872.

The act of beaupleader was passed in the First Statute of Westminster (1275) and meant to prevent sheriffs imposing arbitrary fines on advocates in court who spoke badly. The act was revoked in England and Wales in 1863 and Ireland in 1872.

Published on June 08, 2019 01:00

June 7, 2019

Seeds of the Hundred Years War

Deep in the bowels of the Archives Nationales in Paris is a document dating from 1294. It is written in Old French and has holes for sealing cords, long since rotted away. The document bears the endorsement ‘Non est ibi sigillum’ and the words (in a later hand):

“Certain conventions which the king of England’s men requested before the war, but the lord king [Philip le Bel] refused to consent to them.”

This is the original secret treaty implemented by Edmund of Lancaster, Edward I’s younger brother, in an effort to avoid war with France. The terms offered by Edmund are clearly laid out:

1) In exchange for peace, King Edward would marry Philip’s sister, Margaret of France.

2)The firstborn son of this union and his heirs would hold Gascony in perpetuity.

3) Edward’s subjects in Gascony would no longer be allowed to appeal to the French king in Paris if they rejected the justice of the English king-duke.

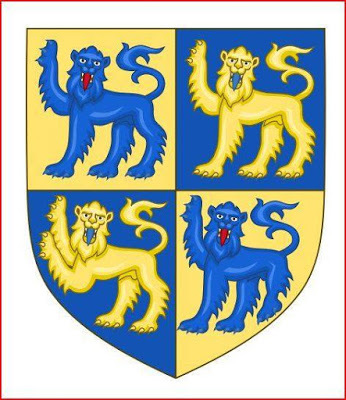

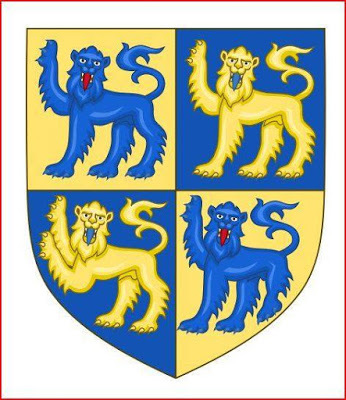

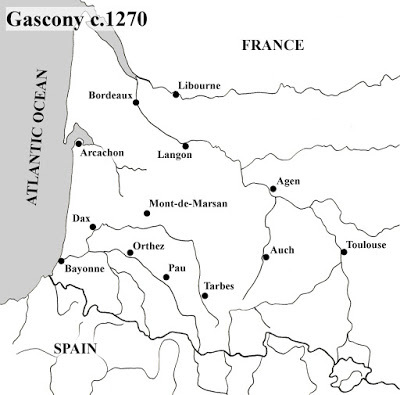

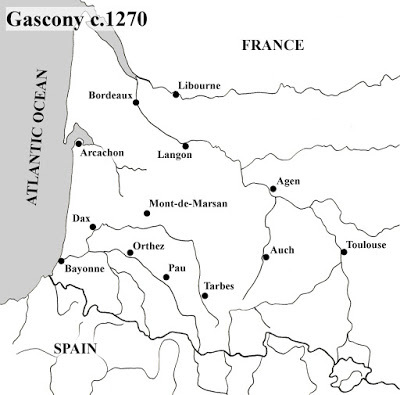

The treaty reveals the extent to which the Plantagenets were prepared to go to hold onto the remnants of the Angevin empire. In return for peace with France, Edward offered to take Gascony out of the direct line of succession. Instead the duchy would be held by a younger half-brother of his heir, the future Edward II. This meant that future kings of England would no longer have to perform the humiliating ritual of homage and fealty to the kings of France in Paris. It also meant the Capetian kings would not be able to cook up any excuses for invading Gascony: the child of Edward and Margaret would be of mixed Plantagenet and Capetian blood, and thus acceptable to all parties. Philip himself could hardly object to his own nephew as Duke of Gascony.

In return for this concession, Edward sought to take Gascony out of the legal orbit of Paris. The French royal pennonceaux, symbolic of Capetian protection and safeguard, would no longer fly over the castles, town-houses or maison-fortes in Gascony. Edward’s policy failed thanks to the duplicity of Phillip, who privately promised to abide by the terms of the treaty and then broke them in public.

The English king was perfectly aware of what would happen in the future: unless legal ties with Paris were severed, the French would seize upon one pretext after another to invade Gascony and drive the English from their last land holdings in France. And so it proved: the duchy was invaded repeatedly over the next 150 years, until the French finally conquered it in the reign of Henry VI.

“Certain conventions which the king of England’s men requested before the war, but the lord king [Philip le Bel] refused to consent to them.”

This is the original secret treaty implemented by Edmund of Lancaster, Edward I’s younger brother, in an effort to avoid war with France. The terms offered by Edmund are clearly laid out:

1) In exchange for peace, King Edward would marry Philip’s sister, Margaret of France.

2)The firstborn son of this union and his heirs would hold Gascony in perpetuity.

3) Edward’s subjects in Gascony would no longer be allowed to appeal to the French king in Paris if they rejected the justice of the English king-duke.

The treaty reveals the extent to which the Plantagenets were prepared to go to hold onto the remnants of the Angevin empire. In return for peace with France, Edward offered to take Gascony out of the direct line of succession. Instead the duchy would be held by a younger half-brother of his heir, the future Edward II. This meant that future kings of England would no longer have to perform the humiliating ritual of homage and fealty to the kings of France in Paris. It also meant the Capetian kings would not be able to cook up any excuses for invading Gascony: the child of Edward and Margaret would be of mixed Plantagenet and Capetian blood, and thus acceptable to all parties. Philip himself could hardly object to his own nephew as Duke of Gascony.

In return for this concession, Edward sought to take Gascony out of the legal orbit of Paris. The French royal pennonceaux, symbolic of Capetian protection and safeguard, would no longer fly over the castles, town-houses or maison-fortes in Gascony. Edward’s policy failed thanks to the duplicity of Phillip, who privately promised to abide by the terms of the treaty and then broke them in public.

The English king was perfectly aware of what would happen in the future: unless legal ties with Paris were severed, the French would seize upon one pretext after another to invade Gascony and drive the English from their last land holdings in France. And so it proved: the duchy was invaded repeatedly over the next 150 years, until the French finally conquered it in the reign of Henry VI.

Published on June 07, 2019 07:44

Sir Adam Gurdun: the sequel

Adam Gurdun: the sequel. In the summer of 1277, eleven years after he crossed swords with the Lord Edward in Alton Wood, Adam was summoned to fight in Wales. He was ordered to join the muster at Worcester on 1 July to serve once again under Roger Mortimer, captain of the army of the Middle March (Adam had served with Mortimer in the same theatre back in 1257).

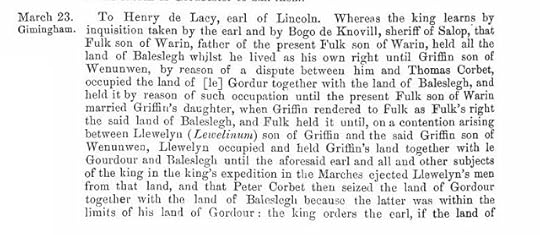

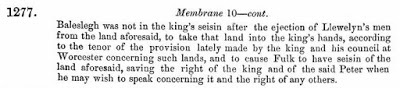

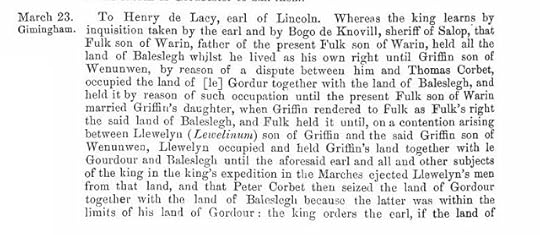

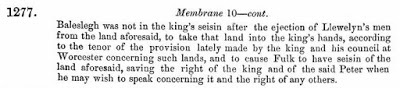

The campaign of 1276-77 against Prince Llywelyn was a far more efficient undertaking than the dismal effort of twenty years earlier. This time the king’s armies were properly supplied and the Marchers and royal captains behaved with greater unity of purpose. Along with Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, Mortimer led a series of determined drives into the marchlands of Bausley and Y Gorddwr (the ‘upper water’ ). Adam, now well into his 50s, joined the army just after Lacy and Mortimer had driven Llywelyn’s men from this region ‘by the strong hand’.

The land-hungry Marchers now turned on each other: unity of purpose only lasted until these boys got their sweaty mailed mittens on some lovely green acres. Fulk Fitzwarin, lord of Whittingdon, claimed he should have Bausley. His father had held the manor until Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn seized it, and then Fulk recovered it by marrying Gruffudd’s daughter. Llywelyn had then seized the manor from Gruffudd, until the king’s army ejected Llywelyn and the land was taken by Peter Corbet, another Marcher. Simple.

Adam had no landed interests in the March, and it was probably a relief when King Edward ordered his service to be transferred to Edmund of Lancaster, the king’s brother. As a result Adam left the middle March and went to serve the standard forty days in Edmund’s army in West Wales.

The campaign of 1276-77 against Prince Llywelyn was a far more efficient undertaking than the dismal effort of twenty years earlier. This time the king’s armies were properly supplied and the Marchers and royal captains behaved with greater unity of purpose. Along with Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, Mortimer led a series of determined drives into the marchlands of Bausley and Y Gorddwr (the ‘upper water’ ). Adam, now well into his 50s, joined the army just after Lacy and Mortimer had driven Llywelyn’s men from this region ‘by the strong hand’.

The land-hungry Marchers now turned on each other: unity of purpose only lasted until these boys got their sweaty mailed mittens on some lovely green acres. Fulk Fitzwarin, lord of Whittingdon, claimed he should have Bausley. His father had held the manor until Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn seized it, and then Fulk recovered it by marrying Gruffudd’s daughter. Llywelyn had then seized the manor from Gruffudd, until the king’s army ejected Llywelyn and the land was taken by Peter Corbet, another Marcher. Simple.

Adam had no landed interests in the March, and it was probably a relief when King Edward ordered his service to be transferred to Edmund of Lancaster, the king’s brother. As a result Adam left the middle March and went to serve the standard forty days in Edmund’s army in West Wales.

Published on June 07, 2019 05:33

Conroi!

Word of the day:

Conroi (oblique plural conrois, nominative singular conrois, nominative plural conroi) In the Middle Ages, a group of five to ten knights who trained and fought together.

Conroi (oblique plural conrois, nominative singular conrois, nominative plural conroi) In the Middle Ages, a group of five to ten knights who trained and fought together.

Published on June 07, 2019 01:22

June 6, 2019

The Jewish diet

Some comments by Mundill on the diet of Anglo-Jews in 13th century England, as opposed to Jews in France. Ten glasses of beer a day!

"In France, meat was commonly eaten in the form of a pastide; whilst in England, the annual gift from Richard Foliot to Hagin of Lincoln (found in the Lincoln areha) of a beast of the chase and other references to Jews enjoying hunting must have meant that hunting and eating the spoils was within the kosher laws.

Wine was of great importance to the Jews. The Eiddush after every meal was always recited over wine. It is clear that the London Jews and in particular Rabbi Elijah Menahem imported his wine from Gascony. There were Jewish vintners in Oxford and Isaac of Colchester had his awn vineyard. It seems that in France cider and liquor made from berries and cherries was not regarded as wine and could be purchased from a Gentile.Alcohol was not forbidden and the Tosafists give as an example of the partial abstinence enjoined on the Feast of the Ninth of Ab the advice that if a Jew was accustomed to drink ten glasses of beer a day, on this day he should drink only five.

Two continental Rabbis had noted with disapproval that 'It is surprising that in the land of the Isle they are lenient in the matter of drinking strong drinks of the Gentiles and along with them'. They claimed that this could lead to intermarriage but went on to add, 'But perhaps as there would be great ill-feeling if they were to refrain from this one must not be severe upon them.' Thus, the Jews' diet set them apart from their host society."

"In France, meat was commonly eaten in the form of a pastide; whilst in England, the annual gift from Richard Foliot to Hagin of Lincoln (found in the Lincoln areha) of a beast of the chase and other references to Jews enjoying hunting must have meant that hunting and eating the spoils was within the kosher laws.

Wine was of great importance to the Jews. The Eiddush after every meal was always recited over wine. It is clear that the London Jews and in particular Rabbi Elijah Menahem imported his wine from Gascony. There were Jewish vintners in Oxford and Isaac of Colchester had his awn vineyard. It seems that in France cider and liquor made from berries and cherries was not regarded as wine and could be purchased from a Gentile.Alcohol was not forbidden and the Tosafists give as an example of the partial abstinence enjoined on the Feast of the Ninth of Ab the advice that if a Jew was accustomed to drink ten glasses of beer a day, on this day he should drink only five.

Two continental Rabbis had noted with disapproval that 'It is surprising that in the land of the Isle they are lenient in the matter of drinking strong drinks of the Gentiles and along with them'. They claimed that this could lead to intermarriage but went on to add, 'But perhaps as there would be great ill-feeling if they were to refrain from this one must not be severe upon them.' Thus, the Jews' diet set them apart from their host society."

Published on June 06, 2019 13:39

Jewish history

Some posts on Jews in Edward I's reign. I'm not too familiar with the subject, and will mostly be quoting from the late Robin Mundill's thesis on the Jewish community in England 1272-1290 (unless stated otherwise).

Some of Mundill's (edited) thoughts on contemporary attitudes towards Jews: "Joshua Trachtenberg observed in 1943 that 'the most vivid impression to be gained from a reading of medieval allusions to the Jews is of a hatred so vast and abysmal, so intense that it leaves one gasping for comprehension. What has been correctly termed 'Jew hatred' rather than anti-semitism had many aspects. In the records of chroniclers, deep odium was reflected by constant references to Jews as 'perfidious'.

The Jew was also commonly referred to as the 'Devil's disciple' and this association had not died out by Shakespeare's day. Was not Mephistophiles the Jew's master and the destruction of Christianity his mission? News of Joseph Cartaphilus, the Wandering Jew, and of strange happenings inthe East reached England in 1228 when an Armenian archbishop visited St Albans. Such news only confirmed the worst suspicions of Gentiles.

Then, as news of Mongol invasions reached the west, panic broke out and the belief that the Jewish legions were at hand was rife. Was not Antichrist to be born of Jewish parents and Armageddon ushered in by the Jews? The ritual murder allegations that first manifested themselves in medieval England are symptomatic of the vast, abysmal and intense hatred that the host majority had for the Jewish minority. As well as unpopular moneylender, the Jew was sorcerer, murderer, cannibal, poisoner, blasphemer, international conspirator and Devil's disciple."

Some of Mundill's (edited) thoughts on contemporary attitudes towards Jews: "Joshua Trachtenberg observed in 1943 that 'the most vivid impression to be gained from a reading of medieval allusions to the Jews is of a hatred so vast and abysmal, so intense that it leaves one gasping for comprehension. What has been correctly termed 'Jew hatred' rather than anti-semitism had many aspects. In the records of chroniclers, deep odium was reflected by constant references to Jews as 'perfidious'.

The Jew was also commonly referred to as the 'Devil's disciple' and this association had not died out by Shakespeare's day. Was not Mephistophiles the Jew's master and the destruction of Christianity his mission? News of Joseph Cartaphilus, the Wandering Jew, and of strange happenings inthe East reached England in 1228 when an Armenian archbishop visited St Albans. Such news only confirmed the worst suspicions of Gentiles.

Then, as news of Mongol invasions reached the west, panic broke out and the belief that the Jewish legions were at hand was rife. Was not Antichrist to be born of Jewish parents and Armageddon ushered in by the Jews? The ritual murder allegations that first manifested themselves in medieval England are symptomatic of the vast, abysmal and intense hatred that the host majority had for the Jewish minority. As well as unpopular moneylender, the Jew was sorcerer, murderer, cannibal, poisoner, blasphemer, international conspirator and Devil's disciple."

Published on June 06, 2019 08:26

Cavalry manoeuvres from John Vernon's The Young Horse-man...

Cavalry manoeuvres from John Vernon's The Young Horse-man (1644):

"The Motions for the Cavalrie are of foure kinds, as Facings, Doublings, Countermarchings, and Wheelings: the use of Facings is to make the Troop perfect, to be sodainly prepared for a Charge on either Flank or Reare, Doublings of Ranks or by half Files, or by Bringers up, serveth to strengthen the Front, Doubling the Files serveth to strengthen the Flanks, Countermarching serving to reduce the File-leaders into the place of the bringers up, that so the best men may be ready to receive the charge of the Enemy in the Reare."

First, however, you must get on your horse.

"The Motions for the Cavalrie are of foure kinds, as Facings, Doublings, Countermarchings, and Wheelings: the use of Facings is to make the Troop perfect, to be sodainly prepared for a Charge on either Flank or Reare, Doublings of Ranks or by half Files, or by Bringers up, serveth to strengthen the Front, Doubling the Files serveth to strengthen the Flanks, Countermarching serving to reduce the File-leaders into the place of the bringers up, that so the best men may be ready to receive the charge of the Enemy in the Reare."

First, however, you must get on your horse.

Published on June 06, 2019 01:17

June 5, 2019

Adam and the prince

On Ascension Day (30 May) 1266, Adam Gurdun and his gang descended upon Shortgrave, a grange in Bedfordshire belonging to Dunstable priory. They stayed all day, looting the manor and eating up the stores, and then rode off taking all they could carry.

The outlaws rode back to their hideout in the forests of Alton in Hampshire, via Kimble and the Chiltern Hills. Adam’s men were in the habit of lying in wait for travellers between the town of Alton and Farnham Castle:

“Which was then in a valley rendered tortuous by well-wooded promontories, and because of this advantageous for robbers…” (William Rishanger)

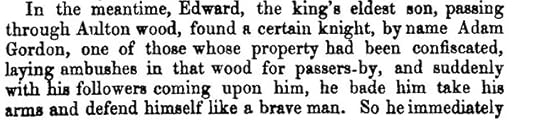

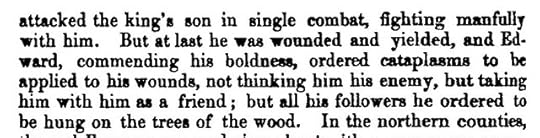

The outlaws didn’t know it, but they were being tracked. Robert Chadd, a deserter, had told the Lord Edward of the location of Adam’s hideout. Guided by Chadd, the prince set off with his knights and discovered the outlaw camp at dusk, ‘about the setting of the sun’. There are several versions of what happened next. One account says that Edward challenged Adam to ‘take his arms and defend himself like a brave man’, after which the two engaged in single combat. Another says that Edward went berserk and charged at Adam without waiting for his men; the prince ended up stranded on the wrong side of a ditch and had to fight the outlaws all by himself until help arrived.

This might sound unlikely, but armoured princes with all the best gear and training were capable of doing some serious damage. Take the account of King Louis VII of France, when he found himself in a tight spot in Asia Minor:

“During the fighting the king lost his small and famous royal guard, but he remained in good heart and nimbly and courageously scaled the side of the mountain by gripping the tree roots that God had provided for his safety. The enemy climbed after him, hoping to capture him, and the archers in the distance continued to shoot arrows at him. But God willed that his cuirass should protect him from the arrows, and to prevent himself from being captured he defended the crag with his bloody sword, cutting off many heads and hands.”

It seems Edward and the outlaw knight fought for a while, until Adam suffered a ‘savage wound’ and had to yield. His life was spared, but Edward ordered all his followers to be hanged on the trees of the wood. This was the fate of penniless thieves, who could not afford to pay ransoms. One later account says that Edward promised Adam life and fortune if he surrendered.

The harsher reality was that Adam was sent off to Windsor as a prisoner. Edward cheerfully quipped he could provide company for Robert Ferrers, Earl of Derby, recently captured by royalist forces at Chesterfield. Adam was given to the queen, Eleanor of Provence, but was later able to buy back his estates at a stiff price. Meanwhile his men rotted on the trees of Alton wood.

The outlaws rode back to their hideout in the forests of Alton in Hampshire, via Kimble and the Chiltern Hills. Adam’s men were in the habit of lying in wait for travellers between the town of Alton and Farnham Castle:

“Which was then in a valley rendered tortuous by well-wooded promontories, and because of this advantageous for robbers…” (William Rishanger)

The outlaws didn’t know it, but they were being tracked. Robert Chadd, a deserter, had told the Lord Edward of the location of Adam’s hideout. Guided by Chadd, the prince set off with his knights and discovered the outlaw camp at dusk, ‘about the setting of the sun’. There are several versions of what happened next. One account says that Edward challenged Adam to ‘take his arms and defend himself like a brave man’, after which the two engaged in single combat. Another says that Edward went berserk and charged at Adam without waiting for his men; the prince ended up stranded on the wrong side of a ditch and had to fight the outlaws all by himself until help arrived.

This might sound unlikely, but armoured princes with all the best gear and training were capable of doing some serious damage. Take the account of King Louis VII of France, when he found himself in a tight spot in Asia Minor:

“During the fighting the king lost his small and famous royal guard, but he remained in good heart and nimbly and courageously scaled the side of the mountain by gripping the tree roots that God had provided for his safety. The enemy climbed after him, hoping to capture him, and the archers in the distance continued to shoot arrows at him. But God willed that his cuirass should protect him from the arrows, and to prevent himself from being captured he defended the crag with his bloody sword, cutting off many heads and hands.”

It seems Edward and the outlaw knight fought for a while, until Adam suffered a ‘savage wound’ and had to yield. His life was spared, but Edward ordered all his followers to be hanged on the trees of the wood. This was the fate of penniless thieves, who could not afford to pay ransoms. One later account says that Edward promised Adam life and fortune if he surrendered.

The harsher reality was that Adam was sent off to Windsor as a prisoner. Edward cheerfully quipped he could provide company for Robert Ferrers, Earl of Derby, recently captured by royalist forces at Chesterfield. Adam was given to the queen, Eleanor of Provence, but was later able to buy back his estates at a stiff price. Meanwhile his men rotted on the trees of Alton wood.

Published on June 05, 2019 07:45