David Pilling's Blog, page 56

June 19, 2019

A multi-cultural mugging

A tale of multi-cultural wonderfulness on the March, in which men of all nations and tongues came together to stage a massive robbery.

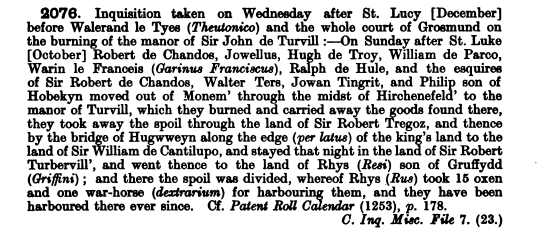

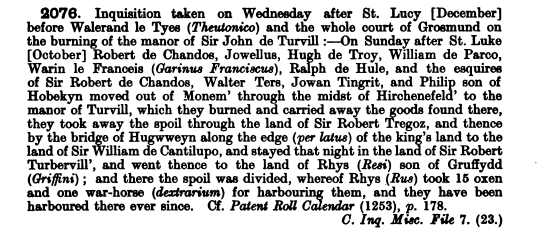

“Other, more dramatic forms of acculturation were taking place. This is evidenced by events in the south-east in October 1252, when Robert de Chandos, lord of Wilmaston in the Golden Valley, and a following that included some of his esquires, men with ‘French’ names and at least one Welsh accomplice, gathered in Monmouth, travelled through Archenfield to the manor of Sir John de Turvill, which they burned and from which they took considerable spoil. They moved on through the land of Sir Robert Tregoz (Ewias Harold) along the edge of the land of the king, into the territory of Sir William de Cantilupe (Abergavenny). They stayed a night in the land of Sir Robert Turberville (Crickhowell) and went finally to the land of Rhys ap Gruffudd. He can be identified as the lord of Senghenydd. There the spoil was divided, with Rhys taking fifteen oxen and one warhorse, as his share in return for harbouring the raiders. They were still living under his protection in December of the year.”

- David Stephenson, Centuries of Ambiguity.

Robert Chandos was an ancestor of Sir John Chandos, the famous warrior of the French wars and one of the original Knights of the Garter. Attached is a pic of the remains of Snodhill Castle, a Chandos stronghold, in Herefordshire’s Golden Valley.

Sir John Chandos

Sir John Chandos

“Other, more dramatic forms of acculturation were taking place. This is evidenced by events in the south-east in October 1252, when Robert de Chandos, lord of Wilmaston in the Golden Valley, and a following that included some of his esquires, men with ‘French’ names and at least one Welsh accomplice, gathered in Monmouth, travelled through Archenfield to the manor of Sir John de Turvill, which they burned and from which they took considerable spoil. They moved on through the land of Sir Robert Tregoz (Ewias Harold) along the edge of the land of the king, into the territory of Sir William de Cantilupe (Abergavenny). They stayed a night in the land of Sir Robert Turberville (Crickhowell) and went finally to the land of Rhys ap Gruffudd. He can be identified as the lord of Senghenydd. There the spoil was divided, with Rhys taking fifteen oxen and one warhorse, as his share in return for harbouring the raiders. They were still living under his protection in December of the year.”

- David Stephenson, Centuries of Ambiguity.

Robert Chandos was an ancestor of Sir John Chandos, the famous warrior of the French wars and one of the original Knights of the Garter. Attached is a pic of the remains of Snodhill Castle, a Chandos stronghold, in Herefordshire’s Golden Valley.

Sir John Chandos

Sir John Chandos

Published on June 19, 2019 04:31

June 18, 2019

More pre-Falkirk foreplay

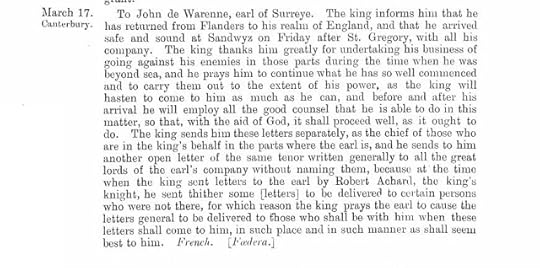

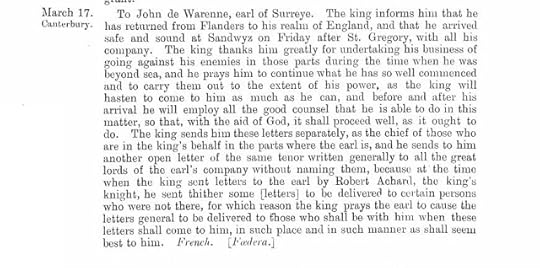

On 17 March (my birthday, as it goes) 1298, soon after his return from Flanders, Edward I sent a letter to Earl Warenne. He thanked the earl for his services in the north while Edward was abroad, and asked him to continue fighting the good fight until the king could join him.

In truth, Earl Warenne had made a ghastly cock of everything. The previous September he was thrashed at Stirling Bridge by William Wallace and Andrew Murray, and then fled south to York after the king had explicitly ordered him to stay in Scotland. Warenne, a perfectly adequate military commander before and after the time of Stirling Bridge, appears to have been taking incompetence pills. Over the winter of 1297-8 he did manage to break the siege of Roxburgh and recapture Berwick, but even these limited successes were owed to others.

In truth, Earl Warenne had made a ghastly cock of everything. The previous September he was thrashed at Stirling Bridge by William Wallace and Andrew Murray, and then fled south to York after the king had explicitly ordered him to stay in Scotland. Warenne, a perfectly adequate military commander before and after the time of Stirling Bridge, appears to have been taking incompetence pills. Over the winter of 1297-8 he did manage to break the siege of Roxburgh and recapture Berwick, but even these limited successes were owed to others.

Robert, the lord of Warkworth, along with John Fitz Marmaduke, gathered their levies and rode quickly at night to ambush the Scottish army outside Roxburgh. They slaughtered the crewmen handling the Scottish siege engines and then drove off the rest of the Scots. This was the sort of feat the Black Douglas would later specialise in, but on this occasion it was the English who stole a march. After hearing of this reverse, Henry de Haliburton abandoned Berwick and withdrew into Scotland.

In truth, Earl Warenne had made a ghastly cock of everything. The previous September he was thrashed at Stirling Bridge by William Wallace and Andrew Murray, and then fled south to York after the king had explicitly ordered him to stay in Scotland. Warenne, a perfectly adequate military commander before and after the time of Stirling Bridge, appears to have been taking incompetence pills. Over the winter of 1297-8 he did manage to break the siege of Roxburgh and recapture Berwick, but even these limited successes were owed to others.

In truth, Earl Warenne had made a ghastly cock of everything. The previous September he was thrashed at Stirling Bridge by William Wallace and Andrew Murray, and then fled south to York after the king had explicitly ordered him to stay in Scotland. Warenne, a perfectly adequate military commander before and after the time of Stirling Bridge, appears to have been taking incompetence pills. Over the winter of 1297-8 he did manage to break the siege of Roxburgh and recapture Berwick, but even these limited successes were owed to others.

Robert, the lord of Warkworth, along with John Fitz Marmaduke, gathered their levies and rode quickly at night to ambush the Scottish army outside Roxburgh. They slaughtered the crewmen handling the Scottish siege engines and then drove off the rest of the Scots. This was the sort of feat the Black Douglas would later specialise in, but on this occasion it was the English who stole a march. After hearing of this reverse, Henry de Haliburton abandoned Berwick and withdrew into Scotland.

Published on June 18, 2019 07:29

Roger Godberd

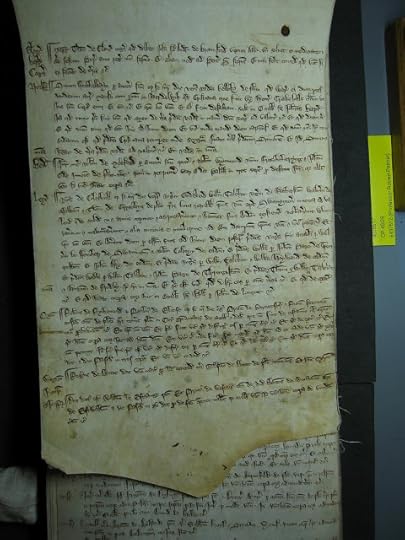

Below is a membrane of a court roll of 1278, in which one Richard Coleshill accused a gang of thieves of taking his goods and chattels from the manor of Swannington in Leicestershire.

The gang was led by Roger Godberd, one of the most remarkable gangsters or mob bosses of the thirteenth century. Roger was a prominent Montfortian outlaw during the 1260s and led a gang of robbers in the forests of Charnwood and Sherwood. Finally, after several years of plaguing the Midlands, he was hunted down and captured by Reynold Grey, High Sheriff of Nottingham.

Unsurprisingly, Roger the Dodger has been suggested as the inspiration for the later Robin Hood ballads. He appears as a supporting player in my new novella, Longsword (IV) The Hooded Men, and I will post more on him in the near future.

The Hooded Men on Amazon US

The Hooded Men on Amazon UK

The gang was led by Roger Godberd, one of the most remarkable gangsters or mob bosses of the thirteenth century. Roger was a prominent Montfortian outlaw during the 1260s and led a gang of robbers in the forests of Charnwood and Sherwood. Finally, after several years of plaguing the Midlands, he was hunted down and captured by Reynold Grey, High Sheriff of Nottingham.

Unsurprisingly, Roger the Dodger has been suggested as the inspiration for the later Robin Hood ballads. He appears as a supporting player in my new novella, Longsword (IV) The Hooded Men, and I will post more on him in the near future.

The Hooded Men on Amazon US

The Hooded Men on Amazon UK

Published on June 18, 2019 01:20

June 17, 2019

Most dear sire

More pre-battle of Falkirk stuff, but with a twist.

Pictured is the Chateau d’Ornans, perched upon a rocky ledge above the Loue valley in Burgundy-Franche-Comté (eastern France). In the summer of 1297 Ornans was briefly the centre of the war of the Grand Alliance; a spectacular extravaganza of treachery and incompetence in which almost every ruler of Western Europe stabbed his neighbour in the back.

One of the few exceptions was Jean de Chalon-Arlay, a lord of Franche-Comté in eastern Burgundy. Jean had been at war with Philip le Bel since 1294, but he and his allies couldn’t hope to defeat the might of France on their own. They were only too pleased to accept cash from Edward of England to help fight the French, and to enter into an alliance with Adolf of Nassau, King of Germany. Adolf promptly broke his word to both Edward and the lords of Franché-Comte, and used the English king’s money to fight a private war in Germany. Clever Adolf! Only not really, since the following year he was butchered at Gollheim by a platoon of Welsh archers. The Plantagenets send their regards, mein herr.

Jean kept his word to the English king and in autumn 1297 went into action against the French. On 8 October the League of Franché-Comte climbed the rock of Ornans - shades of the Scots at Edinburgh in 1314 - and broke into the castle. Taken by surprise, most of the French defenders were either killed or captured, save a few miserable wretches who chose to hurl themselves off the rock.

Proud of his exploit, Jean wrote the following letter to Edward on the same day. Unfortunately the letter is in poor condition and only partially legible:

“Most dear sire, this is to inform you, that on Tuesday, the eve of the feast of Saint Denis, myself and my companions of Burgundy captured and razed the castle of Ornans, which was held by Burgundy of the King of France and was the strongest castle in the whole of Burgundy. And know that, I and my other comrades broke down the walls of the castle and forced our way inside, and secured the castle, and took nine prisoners and put a large number to the sword, apart from those who threw themselves down below the rock. And know, my very dear Sire, that we are committed to the business of…of Burgundy, I will come to join your company, if you desire it…that I think…took. May God guard you sire…and grant you victory against your enemies, which is our dearest desire.”

Pictured is the Chateau d’Ornans, perched upon a rocky ledge above the Loue valley in Burgundy-Franche-Comté (eastern France). In the summer of 1297 Ornans was briefly the centre of the war of the Grand Alliance; a spectacular extravaganza of treachery and incompetence in which almost every ruler of Western Europe stabbed his neighbour in the back.

One of the few exceptions was Jean de Chalon-Arlay, a lord of Franche-Comté in eastern Burgundy. Jean had been at war with Philip le Bel since 1294, but he and his allies couldn’t hope to defeat the might of France on their own. They were only too pleased to accept cash from Edward of England to help fight the French, and to enter into an alliance with Adolf of Nassau, King of Germany. Adolf promptly broke his word to both Edward and the lords of Franché-Comte, and used the English king’s money to fight a private war in Germany. Clever Adolf! Only not really, since the following year he was butchered at Gollheim by a platoon of Welsh archers. The Plantagenets send their regards, mein herr.

Jean kept his word to the English king and in autumn 1297 went into action against the French. On 8 October the League of Franché-Comte climbed the rock of Ornans - shades of the Scots at Edinburgh in 1314 - and broke into the castle. Taken by surprise, most of the French defenders were either killed or captured, save a few miserable wretches who chose to hurl themselves off the rock.

Proud of his exploit, Jean wrote the following letter to Edward on the same day. Unfortunately the letter is in poor condition and only partially legible:

“Most dear sire, this is to inform you, that on Tuesday, the eve of the feast of Saint Denis, myself and my companions of Burgundy captured and razed the castle of Ornans, which was held by Burgundy of the King of France and was the strongest castle in the whole of Burgundy. And know that, I and my other comrades broke down the walls of the castle and forced our way inside, and secured the castle, and took nine prisoners and put a large number to the sword, apart from those who threw themselves down below the rock. And know, my very dear Sire, that we are committed to the business of…of Burgundy, I will come to join your company, if you desire it…that I think…took. May God guard you sire…and grant you victory against your enemies, which is our dearest desire.”

Published on June 17, 2019 07:45

June 16, 2019

Ferrers a la carte

As part of some shameless promo for my new slice of pulp fiction, here’s a potted bio of one of the chief protagonists, Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby.

Robert was born in 1239, the eldest son and heir of the 5th earl, William. The Ferrers were not particularly strong stock and suffered from a hereditary strain of gout, which usually killed off the menfolk in early middle age. They often had to be carried about in a litter, a terrible disgrace for medieval noblemen: condemned criminals were carried in carts to the gallows, so for an aristocrat to travel in the same way was considered shameful. The 12th century poem by Chrétien de Troyes, Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart, lampoons this aspect of chivalric culture.

To add to his shame, Robert’s father was accidentally thrown from his litter while crossing a bridge at St Neots in Huntingdonshire. He survived, but never fully recovered and died in 1254. His heir Robert was still a minor, so his wardship was granted to the Lord Edward, who promptly flogged it to Italian financiers for 6000 marks. This was probably the source of Robert’s later deadly feud with his royal kinsman.

Robert came of age in 1260. His estate was crippled by charges arising from his father’s death, which might explain why the young earl immediately embarked on a career of violence and wayward, sometimes baffling behaviour. He spent the early part of the decade attacking his neighbours in Derbyshire, stealing livestock and goods like a common brigand, at the head of a vast gang of followers. The ‘wild and flighty’ earl even attacked his own family priory at Tutbury. In the process he damaged some of the tombs of his ancestors, extremely odd behaviour for a medieval magnate. Robert certainly inherited a lot of problems, but there was an undeniably savage and unpredictable element to his character.

Fatally, Robert also lacked political judgement, which meant he got screwed by everyone. During the civil wars in England he initially supported Simon de Montfort, only to quit in disgust when Simon’s sons allowed Edward to escape from Gloucester. Simon wanted to get his hands on Robert’s assets in the lordship of Chester, and threw the hapless earl into prison after luring him to London on a false pretext. While Robert was banged up, his tenants in Derbyshire continued to resist and attacked royal officials acting in Simon’s name. Whatever Robert’s flaws, he had a peculiar gift for inspiring loyalty among the ‘men of Ferrers’, as they were called.

Ferrers armsAfter Simon and his army were blown to bits at Evesham, Robert was given a chance to walk away and start again. Henry III gave him a royal pardon, sealed by the gift of a golden cup studded with precious jewels. Even Edward showed he was willing to bury the hatchet. Robert stupidly chose to throw away his shot at redemption and joined the baronial rebels in northern England. In May 1266 the rebel army was ambushed and defeated at Chesterfield while Robert was flat on his back, having his blood let for gout. He then suffered the humiliation of being captured in a church while hiding under a pile of woolsacks. The captive earl was sent south, stuck inside a cage on the back of a wagon, and imprisoned for three years at Windsor.

Ferrers armsAfter Simon and his army were blown to bits at Evesham, Robert was given a chance to walk away and start again. Henry III gave him a royal pardon, sealed by the gift of a golden cup studded with precious jewels. Even Edward showed he was willing to bury the hatchet. Robert stupidly chose to throw away his shot at redemption and joined the baronial rebels in northern England. In May 1266 the rebel army was ambushed and defeated at Chesterfield while Robert was flat on his back, having his blood let for gout. He then suffered the humiliation of being captured in a church while hiding under a pile of woolsacks. The captive earl was sent south, stuck inside a cage on the back of a wagon, and imprisoned for three years at Windsor.

Despite all his naughty doings, Robert's life was spared. As yet there was no precedent for the execution of an earl in England, and nobody wanted to take that final step: it wouldn’t happen until the execution of Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, in 1322. Instead the royal family conspired with the leading magnates of the realm to swindle Robert out of his inheritance, and forced him (probably under threat of torture) to sign away all his lands. Afterwards he was released, landless and penniless, to do as he pleased.

This proved a mistake. Robert gathered the men of Ferrers about him and spent five years waging a guerilla campaign to seize back his lost estates. In 1273 he stormed Chartley Castle, his family seat in Staffordshire, and was only evicted after a year-long siege. After this defeat and the return of his old enemy, Edward - now Edward I - in 1274, it might be expected that Robert had truly had his chips. Once again his head was permitted to remain on its shoulders. Edward allowed Robert to recover two of his lost manors, Chartley and Holbrook in Derbyshire, and live quietly until his death, aged forty, in 1279.

Robert left a son, John, who spent his youth lobbying in vain to recover the rest of his once-vast patrimony. This was impossible since the earldom of Derby was now in the hands of Prince Edmund, King Edward’s younger brother, and would form the basis of the great Honour of Lancaster. John was eventually appointed seneschal of Gascony, where he was poisoned by the Gascons after proving every bit as violent and unstable as his father.

Robert de Ferrers, a crashing failure in life, has the magnificent posthumous honour of appearing in my book Longsword (IV) The Hooded Men, now available on Kindle. The lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky…(etc)…

Longsword IV (The Hooded Men) on Amazon US

Longsword IV (The Hooded Men) on Amazon UK

Robert was born in 1239, the eldest son and heir of the 5th earl, William. The Ferrers were not particularly strong stock and suffered from a hereditary strain of gout, which usually killed off the menfolk in early middle age. They often had to be carried about in a litter, a terrible disgrace for medieval noblemen: condemned criminals were carried in carts to the gallows, so for an aristocrat to travel in the same way was considered shameful. The 12th century poem by Chrétien de Troyes, Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart, lampoons this aspect of chivalric culture.

To add to his shame, Robert’s father was accidentally thrown from his litter while crossing a bridge at St Neots in Huntingdonshire. He survived, but never fully recovered and died in 1254. His heir Robert was still a minor, so his wardship was granted to the Lord Edward, who promptly flogged it to Italian financiers for 6000 marks. This was probably the source of Robert’s later deadly feud with his royal kinsman.

Robert came of age in 1260. His estate was crippled by charges arising from his father’s death, which might explain why the young earl immediately embarked on a career of violence and wayward, sometimes baffling behaviour. He spent the early part of the decade attacking his neighbours in Derbyshire, stealing livestock and goods like a common brigand, at the head of a vast gang of followers. The ‘wild and flighty’ earl even attacked his own family priory at Tutbury. In the process he damaged some of the tombs of his ancestors, extremely odd behaviour for a medieval magnate. Robert certainly inherited a lot of problems, but there was an undeniably savage and unpredictable element to his character.

Fatally, Robert also lacked political judgement, which meant he got screwed by everyone. During the civil wars in England he initially supported Simon de Montfort, only to quit in disgust when Simon’s sons allowed Edward to escape from Gloucester. Simon wanted to get his hands on Robert’s assets in the lordship of Chester, and threw the hapless earl into prison after luring him to London on a false pretext. While Robert was banged up, his tenants in Derbyshire continued to resist and attacked royal officials acting in Simon’s name. Whatever Robert’s flaws, he had a peculiar gift for inspiring loyalty among the ‘men of Ferrers’, as they were called.

Ferrers armsAfter Simon and his army were blown to bits at Evesham, Robert was given a chance to walk away and start again. Henry III gave him a royal pardon, sealed by the gift of a golden cup studded with precious jewels. Even Edward showed he was willing to bury the hatchet. Robert stupidly chose to throw away his shot at redemption and joined the baronial rebels in northern England. In May 1266 the rebel army was ambushed and defeated at Chesterfield while Robert was flat on his back, having his blood let for gout. He then suffered the humiliation of being captured in a church while hiding under a pile of woolsacks. The captive earl was sent south, stuck inside a cage on the back of a wagon, and imprisoned for three years at Windsor.

Ferrers armsAfter Simon and his army were blown to bits at Evesham, Robert was given a chance to walk away and start again. Henry III gave him a royal pardon, sealed by the gift of a golden cup studded with precious jewels. Even Edward showed he was willing to bury the hatchet. Robert stupidly chose to throw away his shot at redemption and joined the baronial rebels in northern England. In May 1266 the rebel army was ambushed and defeated at Chesterfield while Robert was flat on his back, having his blood let for gout. He then suffered the humiliation of being captured in a church while hiding under a pile of woolsacks. The captive earl was sent south, stuck inside a cage on the back of a wagon, and imprisoned for three years at Windsor.Despite all his naughty doings, Robert's life was spared. As yet there was no precedent for the execution of an earl in England, and nobody wanted to take that final step: it wouldn’t happen until the execution of Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, in 1322. Instead the royal family conspired with the leading magnates of the realm to swindle Robert out of his inheritance, and forced him (probably under threat of torture) to sign away all his lands. Afterwards he was released, landless and penniless, to do as he pleased.

This proved a mistake. Robert gathered the men of Ferrers about him and spent five years waging a guerilla campaign to seize back his lost estates. In 1273 he stormed Chartley Castle, his family seat in Staffordshire, and was only evicted after a year-long siege. After this defeat and the return of his old enemy, Edward - now Edward I - in 1274, it might be expected that Robert had truly had his chips. Once again his head was permitted to remain on its shoulders. Edward allowed Robert to recover two of his lost manors, Chartley and Holbrook in Derbyshire, and live quietly until his death, aged forty, in 1279.

Robert left a son, John, who spent his youth lobbying in vain to recover the rest of his once-vast patrimony. This was impossible since the earldom of Derby was now in the hands of Prince Edmund, King Edward’s younger brother, and would form the basis of the great Honour of Lancaster. John was eventually appointed seneschal of Gascony, where he was poisoned by the Gascons after proving every bit as violent and unstable as his father.

Robert de Ferrers, a crashing failure in life, has the magnificent posthumous honour of appearing in my book Longsword (IV) The Hooded Men, now available on Kindle. The lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky…(etc)…

Longsword IV (The Hooded Men) on Amazon US

Longsword IV (The Hooded Men) on Amazon UK

Published on June 16, 2019 05:09

Filthy lucre

Keith Williams-Jones on the motives of the conquest of Wales. Amazingly, it was all about money. What. A. Shock.

“The conquest was certainly not a benevolent act of state. Edward I and his armies, like the Normans before them, conquered for their own profit. All potential assets were to be exploited to the full - even German miners were specially recruited to explore the possibilities of working the copper mines at Diserth. It is true that the issues of the archbishoprics of York and Dublin and those of the king’s lands in Ireland had to be diverted to help finance the construction of the castles, but that applied for the most part to extraordinary expenditure. It is also true that the principality’s accounts were heavily in arrears in the early years after 1282-3. But the aim of making the principality self-supporting was soon achieved: by 1300 it had ‘ceased to be a financial burden to the king’ and more than half the proceeds of the principality’s revenue found its way to the royal coffers.

Further, it was only to be expected that a strong, calculating monarch would, sooner or later, seize the opportunity his vast new power in Wales gave him of exacting some kind of payment from the Marcher lords in return for removing the threat which Llywelyn II had once posed for them. The subsidy of 1292-3 was one way of discharging the debt and proved fairly lucrative from the point of view of the crown - far more so, in sum and proportionately, than the ‘new’ subsidy demanded in 1543 immediately after the ‘Union’. If we are correct in assuming that Wales’s contribution to the subsidy of 1292-3 amounted to about £10,000, it follows that as much as one-twelfth of the total raised by the corresponding subsidy in England came from Wales. The amount Wales was expected to furnish in 1543, however, was only £4,291 out of a total of £74,070 - or about one-eighteenth of the whole. In one particular field, at least, Edward got a better bargain out of his conquest that Henry VIII did in forging the ‘Tudor Union’.”

Those who did get a nasty shock were the Marcher lords, who in 1292 were presented with a massive bill by the king as the price of getting rid of their chief enemy.

“The conquest was certainly not a benevolent act of state. Edward I and his armies, like the Normans before them, conquered for their own profit. All potential assets were to be exploited to the full - even German miners were specially recruited to explore the possibilities of working the copper mines at Diserth. It is true that the issues of the archbishoprics of York and Dublin and those of the king’s lands in Ireland had to be diverted to help finance the construction of the castles, but that applied for the most part to extraordinary expenditure. It is also true that the principality’s accounts were heavily in arrears in the early years after 1282-3. But the aim of making the principality self-supporting was soon achieved: by 1300 it had ‘ceased to be a financial burden to the king’ and more than half the proceeds of the principality’s revenue found its way to the royal coffers.

Further, it was only to be expected that a strong, calculating monarch would, sooner or later, seize the opportunity his vast new power in Wales gave him of exacting some kind of payment from the Marcher lords in return for removing the threat which Llywelyn II had once posed for them. The subsidy of 1292-3 was one way of discharging the debt and proved fairly lucrative from the point of view of the crown - far more so, in sum and proportionately, than the ‘new’ subsidy demanded in 1543 immediately after the ‘Union’. If we are correct in assuming that Wales’s contribution to the subsidy of 1292-3 amounted to about £10,000, it follows that as much as one-twelfth of the total raised by the corresponding subsidy in England came from Wales. The amount Wales was expected to furnish in 1543, however, was only £4,291 out of a total of £74,070 - or about one-eighteenth of the whole. In one particular field, at least, Edward got a better bargain out of his conquest that Henry VIII did in forging the ‘Tudor Union’.”

Those who did get a nasty shock were the Marcher lords, who in 1292 were presented with a massive bill by the king as the price of getting rid of their chief enemy.

Published on June 16, 2019 01:58

June 15, 2019

Pre-Falkirk

We’re coming up to the Battle of Falkirk, about the only medieval anniversary I ever remember; largely thanks to the late Patrick McGoohan’s fantastic sneering performance as Longshanks in That Film, betraying and backstabbing everybody all over the place. The movie strains every sinew to get round the awkward fact that the hero, Wallace, got stuffed at Falkirk. Naturally, it was because the other guys cheated, and not at all because Wallace was simply outgunned and outgeneralled on the day. Naturally.

I digress. In a desperate search to find something new to say about the battle, I stumbled across this document in a printed collection. On 8 June 1298, a few weeks before the battle, King Edward’s diplomats met the King of France, Philip le Bel, for talks at Provins in the diocese of Sens. Here they agreed to a truce proposed by the French, along with an exchange of prisoners. This appears to show the French had already dumped Wallace, even before he engaged the English in battle. Among the documents presented by the English diplomats was a list of names of Scottish landholders (attached, above). These men had aided John Balliol in his war against Edward I, before submitting to the English and swearing to aid Edward against their former lord. This agreement was sealed on the day of St John the Baptist, 1296.

The named individuals on the list appear to have been Galwegians, probably drummed up by Robert de Bruce’s father, Bob Senior. Bruce the elder was given authority by King Ted to take submissions in Scotland, and allegedly provided the English with counterfeit banners to dupe the Scots at Berwick into opening their gates. This latter episode was omitted from a later version of the Scotichronicon, presumably because it was politically embarrassing to mention it in a Scotland ruled by Bruce’s descendants. History written by the victors.

I digress. In a desperate search to find something new to say about the battle, I stumbled across this document in a printed collection. On 8 June 1298, a few weeks before the battle, King Edward’s diplomats met the King of France, Philip le Bel, for talks at Provins in the diocese of Sens. Here they agreed to a truce proposed by the French, along with an exchange of prisoners. This appears to show the French had already dumped Wallace, even before he engaged the English in battle. Among the documents presented by the English diplomats was a list of names of Scottish landholders (attached, above). These men had aided John Balliol in his war against Edward I, before submitting to the English and swearing to aid Edward against their former lord. This agreement was sealed on the day of St John the Baptist, 1296.

The named individuals on the list appear to have been Galwegians, probably drummed up by Robert de Bruce’s father, Bob Senior. Bruce the elder was given authority by King Ted to take submissions in Scotland, and allegedly provided the English with counterfeit banners to dupe the Scots at Berwick into opening their gates. This latter episode was omitted from a later version of the Scotichronicon, presumably because it was politically embarrassing to mention it in a Scotland ruled by Bruce’s descendants. History written by the victors.

Published on June 15, 2019 05:40

Medraut review

A neat but short but nice review of Medraut, the fifth and last book of my Arthurian series, Leader of Battles.

"An extraordinary story. Interesting beyond a doubt. A sorrowful ending for the great Artorius who still lives in our hearts as King Arthur."

Leader of Battles (V) Medraut on Amazon US

"An extraordinary story. Interesting beyond a doubt. A sorrowful ending for the great Artorius who still lives in our hearts as King Arthur."

Leader of Battles (V) Medraut on Amazon US

Published on June 15, 2019 03:19

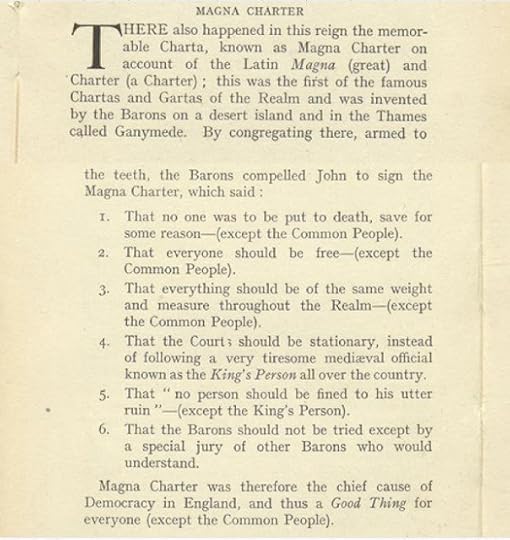

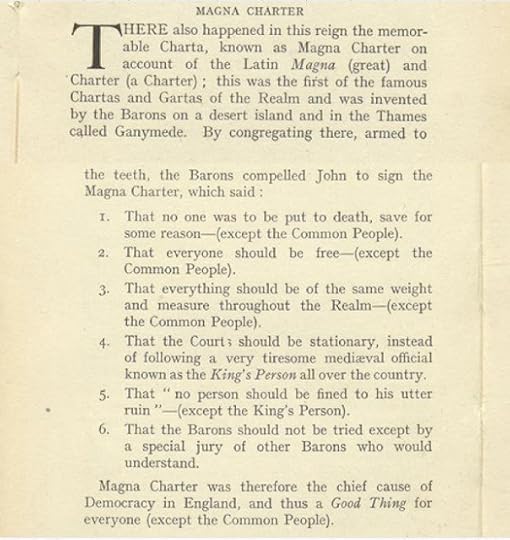

The Great Thingy

On this day in June 1215, King John was compelled to put his seal to the Great Charter by a bunch of democratically-minded barons. Yep, those barons - they were always giving it to the poor.

Here, Messers Sellar and Yeatman remind us of the meaning of this momentous thingy, from 1066 And All That.

Here, Messers Sellar and Yeatman remind us of the meaning of this momentous thingy, from 1066 And All That.

Published on June 15, 2019 01:31

June 14, 2019

New book review

So I've reviewed this. It's very good and makes the reader learn and think, which is also good.

Dr David Stephenson’s new book on medieval Wales has been hailed as a bold commentary on a difficult era of Welsh history, as well as a deliberate challenge to traditional interpretations. This is the judgement of Professor Ralph A Griffiths, Emeritus Professor of Swansea University, and it is hard to disagree. At the same time a ‘deliberate challenge to traditional interpretations’ might sound provocative, as if the author is dealing in subversion to whip up controversy. Thankfully, the book is far more intelligent and incisive than that.

Stephenson concentrates on the political history of Wales c.1050-1332, between the rise and fall of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn and the turbulent reign of Edward II. It is, in the author’s words, meant to provide a sketch of the Age of Princes, and provide an honest - sometimes brutally honest - assessment of why the princes failed to unite Wales. As such the book might not make many friends, but is far too easy to view this era in romantic terms. The truth is not black and white, but the usual muddy shades of grey streaked with someone else’s blood.

The book begins with a fairly conventional outline of the history of Wales in this era, chronicling the invasion of the Normans, the rise and fall of the various native dynasties of Wales and the final conquest by Edward I. Stephenson’s intention is to present an overview of Welsh history as it is generally understood, and then devote the rest of the book to presenting a more ambivalent view: hence the title.

Stephenson examines the Ages of the Princes in terms of shifting political structures. In the thirteenth century the lords of Gwynedd laid claim to the title Prince of Wales, but were not the first to do so. The competing dynasties of Powys and Deheubarth had similar ambitions, and were willing to work with and against each other to undermine their rivals. Many of the princes were hard-nosed, practical men, able to play the game of thrones as well as anyone. The lords of Gwynedd showed a particular eagerness to marry into the royal dynasties of England, and thus cement their overlordship in Wales. These alliances also served to integrate the rulers of Wales into the wider ranks of European royalty. This was a canny move: for all the emphasis on warfare in histories of medieval Wales, the best hope off staving off conquest lay in political ties with English kings and nobility. Thus, Dafydd ap Owain Gwynedd married Emma Plantagenet, his nephew Llywelyn ab Iorwerth cast aside his first wife to marry Joan Plantagenet, and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd married (disastrously) Eleanor de Montfort.

Yet Stephenson refuses to indulge in the tendency to assume that Gwynedd equalled Wales. This impression is understandable, since the princes of Gwynedd were nation-builders who led the final effort to unite the Welsh. There is a danger, however, of ignoring the ‘other Wales’ i.e. the Wales of the Marcher lords and the native dynasties outside Gwynedd. Their actions and desires are frequently subsumed in the obsession with the conflict between Gwynedd, principally the two Llywelyns, and the English crown. The actions and decision-making of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in particular come under the microscope.

Stephenson tackles the difficult question of why, at a vital juncture, Llywelyn’s principality crumbled about his ears. He isn’t the first historian to question the prince’s competence. JG Edwards, for instance, accused Llywelyn of fumbling his way to disaster. Stephenson doesn’t say anything so drastic, but there is a sense that Llywelyn’s career can be divided into two halves. In the first, he enjoyed remarkable success and was the only Welsh ruler to force a King of England to formally recognise his title. Latterly, after the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267, Llywelyn staggered from one mistake and defeat to the next. The contrast is stark enough for Stephenson to suggest that Llywelyn suffered from the loss of a key advisor; possibly Goronwy ab Ednyfed, who died just before the prince’s fortunes started to turn.

The first real fractures in the fledgling principality appeared in the Middle March, where Llywelyn practised heavy-handed methods of retaining the loyalty of local magnates. These were a combination of hostage-taking and intimidation, with neighbouring lords forced to stand surety for the loyalty of those whom the prince suspected. Men such as Hywel ap Meurig, whose families had been in the service of Marcher lords for generations, were not to be bullied into submission. When war finally broke out between England and Wales in 1276, Hywel and his neighbours were in the vanguard of Edward I’s army.

The war of 1282, in which Llywelyn died in murky circumstances, tends to hog the headlines. In terms of hard political reality, the previous war of 1276-77 witnessed the destruction of his power. Much of the explanation lies in the rejection of Venedotian hegemony by the Welsh themselves. The lords of West Wales, Ystrad Tywi and southern Powys all turned against the prince, as did the magnates of the Middle March. Nor was this simply a revolt of the upper classes. When Llywelyn’s hereditary enemy, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, returned from exile to his lordship, the men of Powys abandoned any pretence of loyalty to Llywelyn and flocked to their lord’s banner. The overriding impression is that land and lordship counted for more than ‘nationalism’ in this era, and that shifting allegiances were rarely dictated by love of one’s country.

Not that Stephenson seeks to reinvent the conquest as a misunderstood exercise in Welsh emancipation. As he states, it is depressingly easy to list the dire consequences for the Welsh after 1282: the oppression and discrimination, the eviction of entire communities in favour of English settler communities. North Wales was carved up into English lordships and royal demesne. In the Honour of Denbigh alone, over ten thousand acres of fertile land was occupied by English incomers. Many of the Welsh, meanwhile, were forcibly resettled on vastly inferior uplands. Llanfaes on Anglesey, the principal trading centre of the princes, was destroyed to make way for the castle and new town of Beaumaris, and its inhabitants forced to move across the island to the less profitable centre of Newborough. Stephenson also highlights the massive exploitation of Welsh manpower. Only the large-scale enlistment of Welsh troops in every theatre of war enabled Edward to sustain his tottering empire in the last decade of the reign. Ironically, thousands of these men must have fought against Edward in previous conflicts.

The Edwardian conquest itself is a thorny issue. In recent times some (not unbiased, it must be said) commentators have argued there was no ‘conquest’ per se, but rather a partial occupation. The reality, as RR Davies pointed out long ago, is that Edward I conquered Gwynedd. This made him the most powerful landholder in Wales, able to spend the next decade imposing his power on the rest of the country. Only in 1294, after two further military campaigns and the breaking of the great Marcher lords, could Edward truly call himself the ‘master of Wales’, as Stephenson puts it. In this context 1282, for all its tragedy and drama and emotional appeal, was the first step of a process of conquest. Yet a conquest it was.

Not all Welshmen greeted the new order with dismay. Many of the ‘uchelwyr’ or gentry, men of non-princely rank, fulfilled a prominent role in the Edwardian administration. After the destruction of the princes, these were the natural leaders of Welsh communities. The most prominent in the immediate postconquest era were Morgan ap Maredudd, Gruffudd Llwyd and Dafydd ap Gruffudd of Hendwr. All three appear to have been realists, willing to serve as spies and commissioners of array for Edward I and Edward II. They were possibly torn by conflicting loyalties: Morgan and Gruffudd both intrigued with enemies of the English state, though it is impossible to tell whether they were genuine or acting as mere agent provocateurs.

Closer examination of the evidence reveals all kinds of similar ambiguities. For instance, the revolt against English rule in Gwent in 1294 was not led by Morgan ap Maredudd, as traditionally assumed, but by an obscure local landholder named Meurig ap Dafydd. Meurig had previously been employed as a royal tax collector: a supreme example of this ‘age of ambiguity’.

The last word goes to the author:

“In truth, the post-conquest decades offered to the people of Wales a kaleidoscopic blend of oppression, suffering, frustration, advancement, accumulation of honours and power.”

Dr David Stephenson’s new book on medieval Wales has been hailed as a bold commentary on a difficult era of Welsh history, as well as a deliberate challenge to traditional interpretations. This is the judgement of Professor Ralph A Griffiths, Emeritus Professor of Swansea University, and it is hard to disagree. At the same time a ‘deliberate challenge to traditional interpretations’ might sound provocative, as if the author is dealing in subversion to whip up controversy. Thankfully, the book is far more intelligent and incisive than that.

Stephenson concentrates on the political history of Wales c.1050-1332, between the rise and fall of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn and the turbulent reign of Edward II. It is, in the author’s words, meant to provide a sketch of the Age of Princes, and provide an honest - sometimes brutally honest - assessment of why the princes failed to unite Wales. As such the book might not make many friends, but is far too easy to view this era in romantic terms. The truth is not black and white, but the usual muddy shades of grey streaked with someone else’s blood.

The book begins with a fairly conventional outline of the history of Wales in this era, chronicling the invasion of the Normans, the rise and fall of the various native dynasties of Wales and the final conquest by Edward I. Stephenson’s intention is to present an overview of Welsh history as it is generally understood, and then devote the rest of the book to presenting a more ambivalent view: hence the title.

Stephenson examines the Ages of the Princes in terms of shifting political structures. In the thirteenth century the lords of Gwynedd laid claim to the title Prince of Wales, but were not the first to do so. The competing dynasties of Powys and Deheubarth had similar ambitions, and were willing to work with and against each other to undermine their rivals. Many of the princes were hard-nosed, practical men, able to play the game of thrones as well as anyone. The lords of Gwynedd showed a particular eagerness to marry into the royal dynasties of England, and thus cement their overlordship in Wales. These alliances also served to integrate the rulers of Wales into the wider ranks of European royalty. This was a canny move: for all the emphasis on warfare in histories of medieval Wales, the best hope off staving off conquest lay in political ties with English kings and nobility. Thus, Dafydd ap Owain Gwynedd married Emma Plantagenet, his nephew Llywelyn ab Iorwerth cast aside his first wife to marry Joan Plantagenet, and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd married (disastrously) Eleanor de Montfort.

Yet Stephenson refuses to indulge in the tendency to assume that Gwynedd equalled Wales. This impression is understandable, since the princes of Gwynedd were nation-builders who led the final effort to unite the Welsh. There is a danger, however, of ignoring the ‘other Wales’ i.e. the Wales of the Marcher lords and the native dynasties outside Gwynedd. Their actions and desires are frequently subsumed in the obsession with the conflict between Gwynedd, principally the two Llywelyns, and the English crown. The actions and decision-making of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in particular come under the microscope.

Stephenson tackles the difficult question of why, at a vital juncture, Llywelyn’s principality crumbled about his ears. He isn’t the first historian to question the prince’s competence. JG Edwards, for instance, accused Llywelyn of fumbling his way to disaster. Stephenson doesn’t say anything so drastic, but there is a sense that Llywelyn’s career can be divided into two halves. In the first, he enjoyed remarkable success and was the only Welsh ruler to force a King of England to formally recognise his title. Latterly, after the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267, Llywelyn staggered from one mistake and defeat to the next. The contrast is stark enough for Stephenson to suggest that Llywelyn suffered from the loss of a key advisor; possibly Goronwy ab Ednyfed, who died just before the prince’s fortunes started to turn.

The first real fractures in the fledgling principality appeared in the Middle March, where Llywelyn practised heavy-handed methods of retaining the loyalty of local magnates. These were a combination of hostage-taking and intimidation, with neighbouring lords forced to stand surety for the loyalty of those whom the prince suspected. Men such as Hywel ap Meurig, whose families had been in the service of Marcher lords for generations, were not to be bullied into submission. When war finally broke out between England and Wales in 1276, Hywel and his neighbours were in the vanguard of Edward I’s army.

The war of 1282, in which Llywelyn died in murky circumstances, tends to hog the headlines. In terms of hard political reality, the previous war of 1276-77 witnessed the destruction of his power. Much of the explanation lies in the rejection of Venedotian hegemony by the Welsh themselves. The lords of West Wales, Ystrad Tywi and southern Powys all turned against the prince, as did the magnates of the Middle March. Nor was this simply a revolt of the upper classes. When Llywelyn’s hereditary enemy, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, returned from exile to his lordship, the men of Powys abandoned any pretence of loyalty to Llywelyn and flocked to their lord’s banner. The overriding impression is that land and lordship counted for more than ‘nationalism’ in this era, and that shifting allegiances were rarely dictated by love of one’s country.

Not that Stephenson seeks to reinvent the conquest as a misunderstood exercise in Welsh emancipation. As he states, it is depressingly easy to list the dire consequences for the Welsh after 1282: the oppression and discrimination, the eviction of entire communities in favour of English settler communities. North Wales was carved up into English lordships and royal demesne. In the Honour of Denbigh alone, over ten thousand acres of fertile land was occupied by English incomers. Many of the Welsh, meanwhile, were forcibly resettled on vastly inferior uplands. Llanfaes on Anglesey, the principal trading centre of the princes, was destroyed to make way for the castle and new town of Beaumaris, and its inhabitants forced to move across the island to the less profitable centre of Newborough. Stephenson also highlights the massive exploitation of Welsh manpower. Only the large-scale enlistment of Welsh troops in every theatre of war enabled Edward to sustain his tottering empire in the last decade of the reign. Ironically, thousands of these men must have fought against Edward in previous conflicts.

The Edwardian conquest itself is a thorny issue. In recent times some (not unbiased, it must be said) commentators have argued there was no ‘conquest’ per se, but rather a partial occupation. The reality, as RR Davies pointed out long ago, is that Edward I conquered Gwynedd. This made him the most powerful landholder in Wales, able to spend the next decade imposing his power on the rest of the country. Only in 1294, after two further military campaigns and the breaking of the great Marcher lords, could Edward truly call himself the ‘master of Wales’, as Stephenson puts it. In this context 1282, for all its tragedy and drama and emotional appeal, was the first step of a process of conquest. Yet a conquest it was.

Not all Welshmen greeted the new order with dismay. Many of the ‘uchelwyr’ or gentry, men of non-princely rank, fulfilled a prominent role in the Edwardian administration. After the destruction of the princes, these were the natural leaders of Welsh communities. The most prominent in the immediate postconquest era were Morgan ap Maredudd, Gruffudd Llwyd and Dafydd ap Gruffudd of Hendwr. All three appear to have been realists, willing to serve as spies and commissioners of array for Edward I and Edward II. They were possibly torn by conflicting loyalties: Morgan and Gruffudd both intrigued with enemies of the English state, though it is impossible to tell whether they were genuine or acting as mere agent provocateurs.

Closer examination of the evidence reveals all kinds of similar ambiguities. For instance, the revolt against English rule in Gwent in 1294 was not led by Morgan ap Maredudd, as traditionally assumed, but by an obscure local landholder named Meurig ap Dafydd. Meurig had previously been employed as a royal tax collector: a supreme example of this ‘age of ambiguity’.

The last word goes to the author:

“In truth, the post-conquest decades offered to the people of Wales a kaleidoscopic blend of oppression, suffering, frustration, advancement, accumulation of honours and power.”

Published on June 14, 2019 06:01