David Pilling's Blog, page 47

September 27, 2019

March Mafia

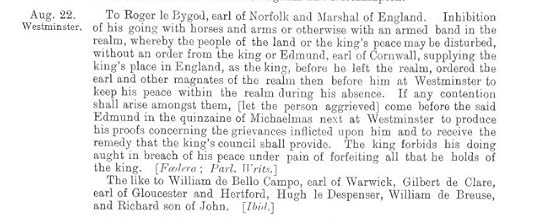

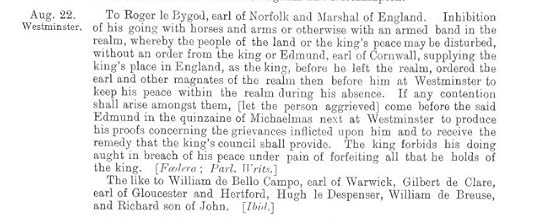

In 1286 Edward I sailed for Gascony and did not return for three years. He left the kingdom in the hands of a deputy, his cousin Edmund, Earl of Cornwall.

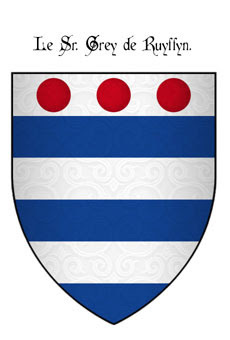

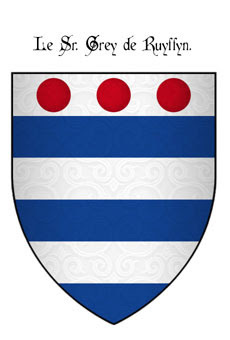

Once the pard was away, his nobles started to play. In December 1286 William de Warenne, son and heir of Earl Warenne, was killed at a tournament in Croydon. He was rumoured to have been murdered. The earl had granted to his son the lordship of Bromfield and Yale on the March, which just happened to lie adjacent to the lands of Reynold Grey, justice of Chester. As a matter of course the dead man’s lands were taken into the king’s hands, which meant Grey took custody of them. Earl Warenne protested that he had granted Bromfield and Yale direct to his son and not in chief from the king. Eventually, at a council meeting in London at Candlemas 1287, Grey was forced to release the lordship.

Grey wasn’t used to being thwarted. He raised an army on his lands in the March and invaded Bromfield and Yale, seizing most of it for himself. When Earl Warenne protested, Grey stuck two fingers up at him and replied that he would keep what he had conquered, and take more if he felt like it. This man, supposedly, was a royal justice invested with the responsibility of enforcing law and order in the king’s absence.

Warenne wrote his friend, the earl of Warwick, asking for assistance. Full-scale civil war in the March was on the cards, but fortunately Warwick had a few more brain cells than the average feudal gangster. He informed the regent of the brewing crisis, and Cornwall in turn issued a general prohibition against military activity. This order was specifically aimed at the earls of Gloucester, Warwick and Norfolk, Hugh Despener, William de Braose, William Fitz John, Earl Warenne and Reynold Grey.

Warenne wrote his friend, the earl of Warwick, asking for assistance. Full-scale civil war in the March was on the cards, but fortunately Warwick had a few more brain cells than the average feudal gangster. He informed the regent of the brewing crisis, and Cornwall in turn issued a general prohibition against military activity. This order was specifically aimed at the earls of Gloucester, Warwick and Norfolk, Hugh Despener, William de Braose, William Fitz John, Earl Warenne and Reynold Grey.

Who promptly ignored it.

Once the pard was away, his nobles started to play. In December 1286 William de Warenne, son and heir of Earl Warenne, was killed at a tournament in Croydon. He was rumoured to have been murdered. The earl had granted to his son the lordship of Bromfield and Yale on the March, which just happened to lie adjacent to the lands of Reynold Grey, justice of Chester. As a matter of course the dead man’s lands were taken into the king’s hands, which meant Grey took custody of them. Earl Warenne protested that he had granted Bromfield and Yale direct to his son and not in chief from the king. Eventually, at a council meeting in London at Candlemas 1287, Grey was forced to release the lordship.

Grey wasn’t used to being thwarted. He raised an army on his lands in the March and invaded Bromfield and Yale, seizing most of it for himself. When Earl Warenne protested, Grey stuck two fingers up at him and replied that he would keep what he had conquered, and take more if he felt like it. This man, supposedly, was a royal justice invested with the responsibility of enforcing law and order in the king’s absence.

Warenne wrote his friend, the earl of Warwick, asking for assistance. Full-scale civil war in the March was on the cards, but fortunately Warwick had a few more brain cells than the average feudal gangster. He informed the regent of the brewing crisis, and Cornwall in turn issued a general prohibition against military activity. This order was specifically aimed at the earls of Gloucester, Warwick and Norfolk, Hugh Despener, William de Braose, William Fitz John, Earl Warenne and Reynold Grey.

Warenne wrote his friend, the earl of Warwick, asking for assistance. Full-scale civil war in the March was on the cards, but fortunately Warwick had a few more brain cells than the average feudal gangster. He informed the regent of the brewing crisis, and Cornwall in turn issued a general prohibition against military activity. This order was specifically aimed at the earls of Gloucester, Warwick and Norfolk, Hugh Despener, William de Braose, William Fitz John, Earl Warenne and Reynold Grey.Who promptly ignored it.

Published on September 27, 2019 04:19

September 25, 2019

Raging in his fury: the trials of Madog ap Llywelyn (4)

The ‘war of Madog’, as it was remembered, began either on 29 or 30 September 1294. The Brut describes the start of the revolt thus:

Geoffrey Clement, justice of Deheubarth, was slain at 'Y Gwmfriw' in Builth. And there was a breach between Welsh and English on that feast of Michael. And Cynan ap Maredudd and Maelgwn ap Rhys were chief over Deheubarth, and Madog ap Llywelyn ap Maredudd over Gwynedd, and Morgan ap Maredudd over Morgannwg.

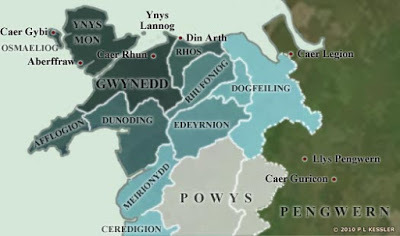

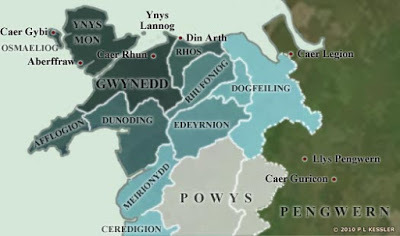

To judge from this, there were four main leaders, and they intended to partition Wales. As a member of the house of Aberffrau, Madog would have Gwynedd. Cynan ap Maredudd and Maelgwyn ap Rhys were both direct descendants of the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, and would divide their patrimony between them. Morgan ap Maredudd, a descendent of the ancient kings of Morgannwg, would have that territory.

Madog is clearly identified as the most important of the four. His revolt began on Anglesey - Ynys Mon - where he attacked the township of Llanfaes and destroyed the church. His choice of Llanfaes as a target is interesting. It was one of five bond townships (maerdrefi) in Anglesey associated with the royal court of Gwynedd. It was also the commercial centre of Gwynedd under the native princes; there was a port, a ferry across the Menai strait, and a herring fishery. Under the rule of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, about 70% of of the principality’s trade passed through the port. In 1992 a hoard of over one hundred silver medieval coins were discovered at Anglesey, demonstrating its importance as a trading centre (see link below).

When Madog attacked Llanfaes, the township was home to a community of English merchants. After the revolt, they sent the following desperate petition to Edward I:

THE BURGESSES OF LLANMAES (LLANFAES-ANGLESEY) TO THE KING:

They show that they are English in blood and in nationality, as also their ancestors of ancient times, by occasion of which fact, when the dominance of the Welsh was in its vigour, and especially at the time when Madoc was raging in his fury, they were oppressed by the Welsh and deprived of their property, and because, to tell the simple truth, they reside in Wales and among the Welsh, they are reputed Welsh by the English and in consequence are the less favoured by them so that they have neither the status of Englishmen nor even that of Welshmen, but they experience what is worst in either condition. They therefore pray that for the love of Our Lord Jesus Christ, as the King mercifully regards all Wales in common, so it may please him, for the good of his soul and of his parents' souls, to establish them in an assured position before he departs from Wales and to confirm it by his letters so that they may not fall into an indubitable state of beggary or worse'.

A later petition of c.1318 shows that Llanfaes continued to decline as the fairs and markets were relocated to Beaumaris. The population was moved to another maerdref, Rhosyr, about twelve miles away. This was renamed New Borough, and received its charter of incorporation on 24 April 1303.

MEDIEVAL COINS AT LLANFAES, ANGLESEY

Geoffrey Clement, justice of Deheubarth, was slain at 'Y Gwmfriw' in Builth. And there was a breach between Welsh and English on that feast of Michael. And Cynan ap Maredudd and Maelgwn ap Rhys were chief over Deheubarth, and Madog ap Llywelyn ap Maredudd over Gwynedd, and Morgan ap Maredudd over Morgannwg.

To judge from this, there were four main leaders, and they intended to partition Wales. As a member of the house of Aberffrau, Madog would have Gwynedd. Cynan ap Maredudd and Maelgwyn ap Rhys were both direct descendants of the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, and would divide their patrimony between them. Morgan ap Maredudd, a descendent of the ancient kings of Morgannwg, would have that territory.

Madog is clearly identified as the most important of the four. His revolt began on Anglesey - Ynys Mon - where he attacked the township of Llanfaes and destroyed the church. His choice of Llanfaes as a target is interesting. It was one of five bond townships (maerdrefi) in Anglesey associated with the royal court of Gwynedd. It was also the commercial centre of Gwynedd under the native princes; there was a port, a ferry across the Menai strait, and a herring fishery. Under the rule of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, about 70% of of the principality’s trade passed through the port. In 1992 a hoard of over one hundred silver medieval coins were discovered at Anglesey, demonstrating its importance as a trading centre (see link below).

When Madog attacked Llanfaes, the township was home to a community of English merchants. After the revolt, they sent the following desperate petition to Edward I:

THE BURGESSES OF LLANMAES (LLANFAES-ANGLESEY) TO THE KING:

They show that they are English in blood and in nationality, as also their ancestors of ancient times, by occasion of which fact, when the dominance of the Welsh was in its vigour, and especially at the time when Madoc was raging in his fury, they were oppressed by the Welsh and deprived of their property, and because, to tell the simple truth, they reside in Wales and among the Welsh, they are reputed Welsh by the English and in consequence are the less favoured by them so that they have neither the status of Englishmen nor even that of Welshmen, but they experience what is worst in either condition. They therefore pray that for the love of Our Lord Jesus Christ, as the King mercifully regards all Wales in common, so it may please him, for the good of his soul and of his parents' souls, to establish them in an assured position before he departs from Wales and to confirm it by his letters so that they may not fall into an indubitable state of beggary or worse'.

A later petition of c.1318 shows that Llanfaes continued to decline as the fairs and markets were relocated to Beaumaris. The population was moved to another maerdref, Rhosyr, about twelve miles away. This was renamed New Borough, and received its charter of incorporation on 24 April 1303.

MEDIEVAL COINS AT LLANFAES, ANGLESEY

Published on September 25, 2019 04:11

September 24, 2019

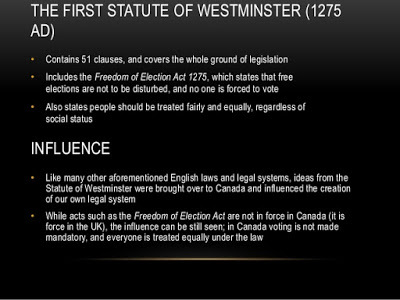

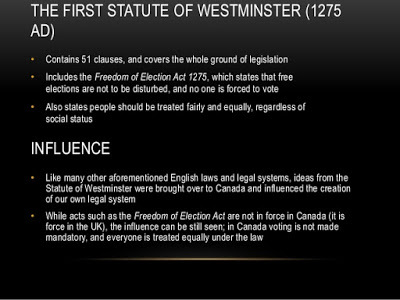

Freedom of Elections

This seems appropriate, given events in the Supreme Court today…

The Freedom of Elections Act is the second of two clauses of Statute of Westminster I (1275) still in force in England and Wales. It reads thus:

"There shall be no Disturbance of Free Elections. Elections shall be free. AND because Elections ought to be free, the King commandeth upon great Forfeiture, that no Man by force of Arms, nor by Malice, or Menacing, shall disturb any to make free Election."

The original purpose of this act was to ensure that the election of sheriffs, coroners, bailiffs and so forth were fair and equal, and could not be influenced by intimidation or corruption etc. As time went on the act became a convenient basis for representative government. It has influenced the growth of democratic legislature all over the planet.

Edward’s notions of representation were absorbed in his youth from Simon de Montfort and the baronial reform movement. He eventually destroyed Simon - before Simon could destroy him - but the the principles of reform were enshrined in the great statutes and parliaments of Edward’s reign.

The Freedom of Elections Act is the second of two clauses of Statute of Westminster I (1275) still in force in England and Wales. It reads thus:

"There shall be no Disturbance of Free Elections. Elections shall be free. AND because Elections ought to be free, the King commandeth upon great Forfeiture, that no Man by force of Arms, nor by Malice, or Menacing, shall disturb any to make free Election."

The original purpose of this act was to ensure that the election of sheriffs, coroners, bailiffs and so forth were fair and equal, and could not be influenced by intimidation or corruption etc. As time went on the act became a convenient basis for representative government. It has influenced the growth of democratic legislature all over the planet.

Edward’s notions of representation were absorbed in his youth from Simon de Montfort and the baronial reform movement. He eventually destroyed Simon - before Simon could destroy him - but the the principles of reform were enshrined in the great statutes and parliaments of Edward’s reign.

Published on September 24, 2019 08:18

The English Justinian

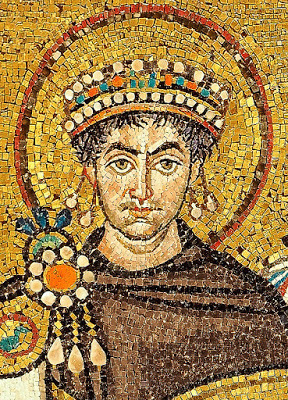

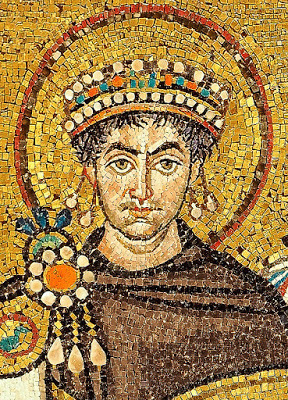

In the 17th century Sir Edward Coke, an English barrister, judge and politician, dubbed Edward I the ‘English Justinian’. Coke drew a comparison between Edward and the 6th century Roman Emperor, Justinian I, who codified the system of Roman law.

Justinian IThis is one of Edward’s nicknames, such as Longshanks or the Hammer of the Scots, that have dogged his posthumous reputation ever since. His reign witnessed enormous legal reforms, and several of his statutes are still in force in England and Wales. How much Edward was responsible for it, or even whether he had any personal interest in the law at all, is up for debate.

Justinian IThis is one of Edward’s nicknames, such as Longshanks or the Hammer of the Scots, that have dogged his posthumous reputation ever since. His reign witnessed enormous legal reforms, and several of his statutes are still in force in England and Wales. How much Edward was responsible for it, or even whether he had any personal interest in the law at all, is up for debate.

Other than surface details - his speech impediment, his fondness for hunting, his love for his wives etc - it isn’t easy to gauge the king’s personality. Edward was almost as inscrutable as his cousin, Philip le Bel, the Iron King (le Roi de Fer) whose personality was kept in a locked cage somewhere in the depths of his massive brain.

All we can do is rely on bits and pieces of documentary evidence. In a writ to the justiciar of his lordship of Chester in 1259, Edward expressed the following sentiment:

‘If common justice is denied to any one of our subjects by us or our bailiffs, we lose the favour of God and man, and our lordship is belittled’.

If Edward is to be taken at his word, he seems to have meant that common justice to all was necessary, otherwise his lordship over men had no value. This was a private writ, so there is no reason to accuse him of playing to the gallery.

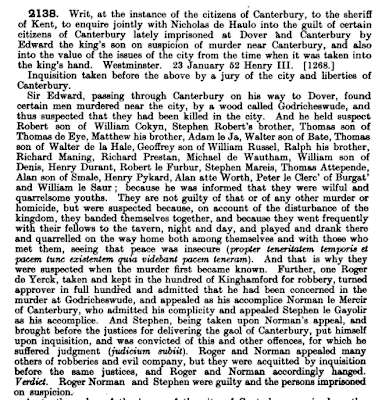

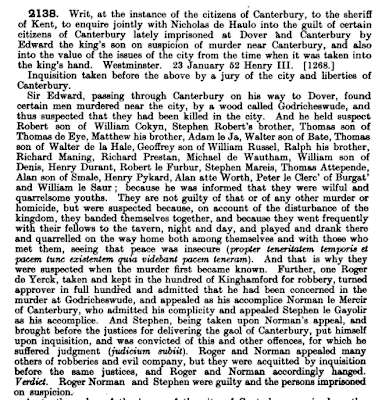

A few years later, in 1269, Edward gave more solid proof of his interest in common justice. While travelling on the road between Canterbury to Dover, he discovered some corpses lying in the woods. Edward suspected foul play and immediately set up a jury, where he accused several local men, ‘wilful and quarrelsome youths’, of doing the deed. Eventually two other men, not members of the gang, were convicted and hanged after trying to pin the guilt on each other. In this instance Edward’s judgement was at fault, but he was certainly taking an interest.

Justinian IThis is one of Edward’s nicknames, such as Longshanks or the Hammer of the Scots, that have dogged his posthumous reputation ever since. His reign witnessed enormous legal reforms, and several of his statutes are still in force in England and Wales. How much Edward was responsible for it, or even whether he had any personal interest in the law at all, is up for debate.

Justinian IThis is one of Edward’s nicknames, such as Longshanks or the Hammer of the Scots, that have dogged his posthumous reputation ever since. His reign witnessed enormous legal reforms, and several of his statutes are still in force in England and Wales. How much Edward was responsible for it, or even whether he had any personal interest in the law at all, is up for debate. Other than surface details - his speech impediment, his fondness for hunting, his love for his wives etc - it isn’t easy to gauge the king’s personality. Edward was almost as inscrutable as his cousin, Philip le Bel, the Iron King (le Roi de Fer) whose personality was kept in a locked cage somewhere in the depths of his massive brain.

All we can do is rely on bits and pieces of documentary evidence. In a writ to the justiciar of his lordship of Chester in 1259, Edward expressed the following sentiment:

‘If common justice is denied to any one of our subjects by us or our bailiffs, we lose the favour of God and man, and our lordship is belittled’.

If Edward is to be taken at his word, he seems to have meant that common justice to all was necessary, otherwise his lordship over men had no value. This was a private writ, so there is no reason to accuse him of playing to the gallery.

A few years later, in 1269, Edward gave more solid proof of his interest in common justice. While travelling on the road between Canterbury to Dover, he discovered some corpses lying in the woods. Edward suspected foul play and immediately set up a jury, where he accused several local men, ‘wilful and quarrelsome youths’, of doing the deed. Eventually two other men, not members of the gang, were convicted and hanged after trying to pin the guilt on each other. In this instance Edward’s judgement was at fault, but he was certainly taking an interest.

Published on September 24, 2019 01:08

September 22, 2019

Raging in his fury: the trials of Madog ap Llywelyn (3)

Between 1278-94, little is known of Madog. He doesn’t appear to have taken any part in the second war between Edward and Llywelyn in 1282-3, though he and his family presumably continued to dwell on Anglesey. They would have witnessed the landing of Edward’s expeditionary force on the isle in August, and Luke de Tany’s disastrous effort to cross the bridge of boats in November.

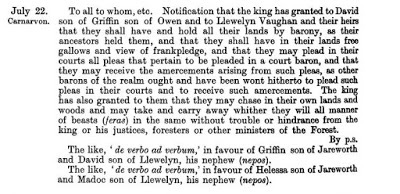

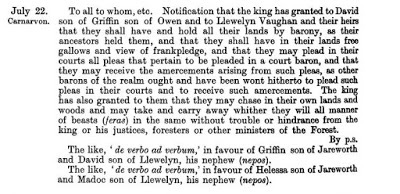

There is one possible reference to Madog in 1284. In July, at Caernarfon, Edward granted to Gruffudd ap Iorwerth and his nephew, Dafydd ap Llywelyn, and to Elise ap Iorwerth and his nephew, Madog ap Llywelyn, the right to hold all their lands in Wales by barony, as their ancestors had done. Gruffudd and Elise were lords of Edeirnion in the west of northern Powys and descendants of Owain Brogontyn; their ancestors had established themselves in Edeirnion and Dinmael by the early 13th century.

This lineage achieved some prominence in Wales. In 1258 Gruffudd and Elise were among the Welsh magnates who witnessed Prince Llywelyn’s agreement with the lords of Scotland; this was the first document in which Llywelyn styled himself ‘principe Wallie’ or Prince of Wales. Elise afterwards fell out with Llywelyn and was imprisoned, only to be released via the terms of the Treaty of Aberconwy in 1277. Gruffudd and Elise fought for Llywelyn against Edward in 1282, but were pardoned.

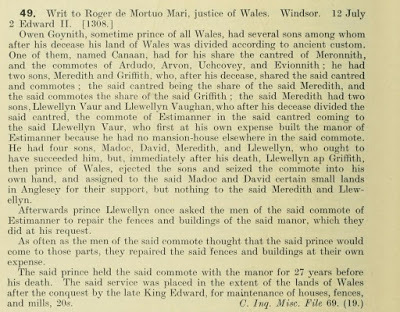

The names of their nephews, Madog and Dafydd, are not found in any other pedigrees relating to this lineage. Madog ap Llywelyn was the only contemporary figure of that name whose ancestry justified being granted tenure by barony: his father, Llywelyn ap Maredudd, had promised fealty to Henry III in 1246 on condition that and his heirs should be maintained according to the custom of Welsh barons. The tenure translated by the English as ‘Welsh barony’ was called ‘pennaeth’ in Welsh. In 1308 Llywelyn ab Owain, a lord of Ceredigion, was described as holding:

‘By the Welsh tenure Pennaethium…by fealty and service, that he and all his tenants wherever necessary were bound to come at the summons of the king’s bailiffs for three days at their own cost, and he owed suit at the court of Cardigan called the Welsh county. After his death the king was entitled to 100 shillings ‘ebediw’ and according to Welsh custom the lordship should be divided between his sons. The king cannot claim wardship or marriage’.

There is one possible reference to Madog in 1284. In July, at Caernarfon, Edward granted to Gruffudd ap Iorwerth and his nephew, Dafydd ap Llywelyn, and to Elise ap Iorwerth and his nephew, Madog ap Llywelyn, the right to hold all their lands in Wales by barony, as their ancestors had done. Gruffudd and Elise were lords of Edeirnion in the west of northern Powys and descendants of Owain Brogontyn; their ancestors had established themselves in Edeirnion and Dinmael by the early 13th century.

This lineage achieved some prominence in Wales. In 1258 Gruffudd and Elise were among the Welsh magnates who witnessed Prince Llywelyn’s agreement with the lords of Scotland; this was the first document in which Llywelyn styled himself ‘principe Wallie’ or Prince of Wales. Elise afterwards fell out with Llywelyn and was imprisoned, only to be released via the terms of the Treaty of Aberconwy in 1277. Gruffudd and Elise fought for Llywelyn against Edward in 1282, but were pardoned.

The names of their nephews, Madog and Dafydd, are not found in any other pedigrees relating to this lineage. Madog ap Llywelyn was the only contemporary figure of that name whose ancestry justified being granted tenure by barony: his father, Llywelyn ap Maredudd, had promised fealty to Henry III in 1246 on condition that and his heirs should be maintained according to the custom of Welsh barons. The tenure translated by the English as ‘Welsh barony’ was called ‘pennaeth’ in Welsh. In 1308 Llywelyn ab Owain, a lord of Ceredigion, was described as holding:

‘By the Welsh tenure Pennaethium…by fealty and service, that he and all his tenants wherever necessary were bound to come at the summons of the king’s bailiffs for three days at their own cost, and he owed suit at the court of Cardigan called the Welsh county. After his death the king was entitled to 100 shillings ‘ebediw’ and according to Welsh custom the lordship should be divided between his sons. The king cannot claim wardship or marriage’.

Published on September 22, 2019 02:58

September 21, 2019

Raging in his fury: the trials of Madog ap Llywelyn (2)

When war broke out between Prince Llywelyn and Edward I in 1276, Madog chose to serve the king. This was almost certainly a bid to recover his lost inheritance in Meirionydd, and he seems to have obtained official recognition from the crown of his status: an abbreviated payment of 20 shillings to Madog refers to him as ‘d’no Merioneth’ or lord of Merioneth/Meirionydd.

Madog’s actions during the war are uncertain, though a man of the same name crops up on a payroll for the army of the Middle March, serving with a ‘barded’ horse; barding in this era being a padded leather covering for the horse. This man appears under a payment for men raised at Clun, a long way from Madog’s home on Anglesey. However, his father had died in a battle at Clun, and it is not impossible that he did military service in the same region.

When the war was over, the defeated Prince Llywelyn immediately set about trying to recover his position. He invited certain lords of West Wales, who had fought for King Edward, to his court at Dolwyddelan in Snowdonia. Madog had no interest in reconciliation, and brought a lawsuit against Llywelyn for the land of Meirionydd.

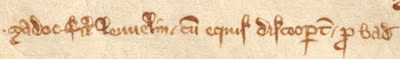

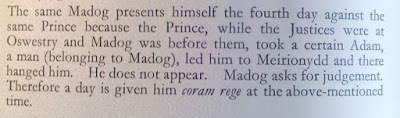

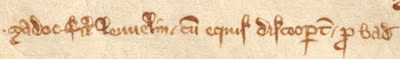

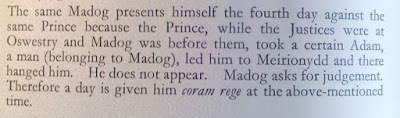

Llywelyn was furious. While the case was in progress at Oswestry, the prince seized one of Madog’s servants, a certain Adam, took him to Meirionydd and hanged him. No charges were levied against Adam, and he appears to have been executed - murdered, to use plain language - to make a point. Llywelyn ruled over Meirionydd and Madog would never get it back.

Dolwyddelan

Dolwyddelan

This was very unusual: unlike many Welsh princes, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd preferred to avoid bloodshed and never indulged in the customary blinding and castration of political rivals. His savagery towards the hapless Adam can only be explained by his fear of the threat posed by Madog.

Madog’s actions during the war are uncertain, though a man of the same name crops up on a payroll for the army of the Middle March, serving with a ‘barded’ horse; barding in this era being a padded leather covering for the horse. This man appears under a payment for men raised at Clun, a long way from Madog’s home on Anglesey. However, his father had died in a battle at Clun, and it is not impossible that he did military service in the same region.

When the war was over, the defeated Prince Llywelyn immediately set about trying to recover his position. He invited certain lords of West Wales, who had fought for King Edward, to his court at Dolwyddelan in Snowdonia. Madog had no interest in reconciliation, and brought a lawsuit against Llywelyn for the land of Meirionydd.

Llywelyn was furious. While the case was in progress at Oswestry, the prince seized one of Madog’s servants, a certain Adam, took him to Meirionydd and hanged him. No charges were levied against Adam, and he appears to have been executed - murdered, to use plain language - to make a point. Llywelyn ruled over Meirionydd and Madog would never get it back.

Dolwyddelan

DolwyddelanThis was very unusual: unlike many Welsh princes, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd preferred to avoid bloodshed and never indulged in the customary blinding and castration of political rivals. His savagery towards the hapless Adam can only be explained by his fear of the threat posed by Madog.

Published on September 21, 2019 09:21

Raging in his fury: the trials of Madog ap Llywelyn (1)

Madog ap Llywelyn was the eldest son of Llywelyn ap Maredudd, a prince of the House of Aberffraw and direct descendant of Owain Gwynedd via one of the latter’s many sons, Prince Cynan, lord of Meirionydd. He thus inherited yet another long-standing feud between the senior branch of Aberffraw and rival claimants.

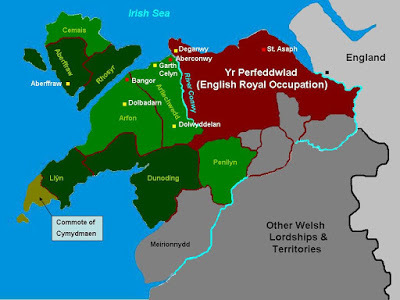

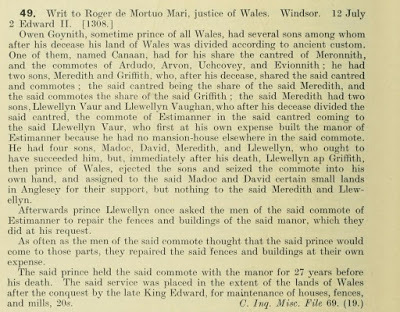

In December 1256 Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, lord of Gwynedd, summoned Llywelyn ap Maredudd to join forces with him. The prince had just conquered the Lord Edward’s lordship in the Perfeddwlad and now wished to extend direct control over Meirionydd. Llywelyn ap Maredudd refused and instead fled into England with his family. He wrote a letter to Henry III, commending himself as one who preferred fidelity to unfaithfulness, and asking for money from the royal exchequer. The king put him on a pension; in this respect Henry’s successor, Edward I, did no more than copy his father’s policy of granting asylum to useful waifs and strays from Wales.

Madog was the eldest of four sons, the others being Dafydd, Maredudd and Llywelyn. On 25 May 1263 their father was killed in a fight at the Clun. His death was mourned by Welsh chroniclers:

"On 25 May at Clun there were killed nearly a hundred men, among whom was Llywelyn ap Maredudd, the flower of the juveniles of Wales. He indeed was strenuous and strong in arms, lavish in gifts and in advice prophetic and he was loved by all.” (Annales Cambriae)

It is unclear whose side Llywelyn was fighting on. The Lord Edward campaigned in North Wales in this year, and a later inquisition of 1308 discovered that Llywelyn re-occupied Meirionydd at the same time. While he rode off to his death at Clun, his four sons were left in possession of the commote of Ystumanner. Immediately after he was killed, Prince Llywelyn invaded Meirionydd and drove Madog and his brothers into exile. This sequence of events would appear to confirm that Llywelyn ap Maredudd was on Edward’s side, and died at Clun fighting alongside the Marchers.

Once Meirionydd was firmly in his grasp, Prince Llywelyn relented a little. He granted the vills of Llanllibio and Lledwigan Llan on Mon (Anglesey) to Madog and Dafydd, but nothing to the two younger brothers. They presumably had to live off the charity of their elder siblings.

In December 1256 Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, lord of Gwynedd, summoned Llywelyn ap Maredudd to join forces with him. The prince had just conquered the Lord Edward’s lordship in the Perfeddwlad and now wished to extend direct control over Meirionydd. Llywelyn ap Maredudd refused and instead fled into England with his family. He wrote a letter to Henry III, commending himself as one who preferred fidelity to unfaithfulness, and asking for money from the royal exchequer. The king put him on a pension; in this respect Henry’s successor, Edward I, did no more than copy his father’s policy of granting asylum to useful waifs and strays from Wales.

Madog was the eldest of four sons, the others being Dafydd, Maredudd and Llywelyn. On 25 May 1263 their father was killed in a fight at the Clun. His death was mourned by Welsh chroniclers:

"On 25 May at Clun there were killed nearly a hundred men, among whom was Llywelyn ap Maredudd, the flower of the juveniles of Wales. He indeed was strenuous and strong in arms, lavish in gifts and in advice prophetic and he was loved by all.” (Annales Cambriae)

It is unclear whose side Llywelyn was fighting on. The Lord Edward campaigned in North Wales in this year, and a later inquisition of 1308 discovered that Llywelyn re-occupied Meirionydd at the same time. While he rode off to his death at Clun, his four sons were left in possession of the commote of Ystumanner. Immediately after he was killed, Prince Llywelyn invaded Meirionydd and drove Madog and his brothers into exile. This sequence of events would appear to confirm that Llywelyn ap Maredudd was on Edward’s side, and died at Clun fighting alongside the Marchers.

Once Meirionydd was firmly in his grasp, Prince Llywelyn relented a little. He granted the vills of Llanllibio and Lledwigan Llan on Mon (Anglesey) to Madog and Dafydd, but nothing to the two younger brothers. They presumably had to live off the charity of their elder siblings.

Published on September 21, 2019 04:47

September 16, 2019

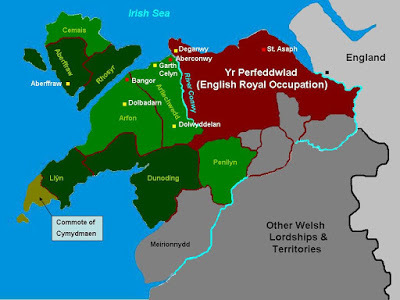

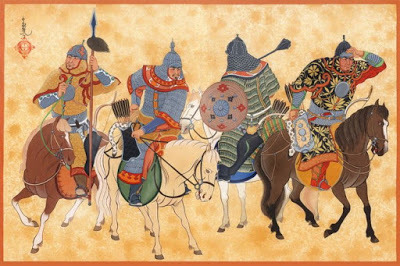

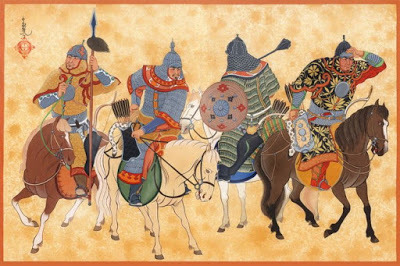

Longshanks and the Golden Horde

In mid-October 1271 a mounted column of over ten thousand Mongol lancers and Rumis (Turkish soldiers in the service of the il-khanate) invaded northern Syria. They were led by the warlord Samaghar and dispatched by the il-khan, Abaqa, in response to a plea for aid from the envoys of the Lord Edward.

The Mongols were keen on forging an effective alliance with the Franks, though the latter often disappointed. Mongol envoys had previously journeyed to Tunis to treat with the French king, Saint Louis, only to find him on his deathbed. They may have accompanied and advised Edward during his voyage from Tunis to Acre, which would explain why he was quick to send a team of diplomats to the court of the il-khan. His three envoys - Reginald Rossel, Godfrey Waus and John le Parker - underwent a hazardous journey through Mamluk territory to reach the il-khanate; this was set up to control the southwest section of the Mongol Empire, comprising present-day Iran and neighbouring territories.

At first all went swimmingly. The Mongols stormed past Aleppo, forcing the Mamluk garrison to evacuate the town, and then pushed up the Orontes valley past Hamah in west-central Syria. They appeared to be concentrating for an assault on Damascus, where the governor of the city arrived on 9 November to find the citizens in a state of panic. Eleven years earlier Damascus had been sacked by another Mongol warlord, Kitbogha, and memories were still fresh.

As ever in a crisis, Baibars kept a cool head and concentrated on reinforcing his garrisons in northern Syria. He knew Damascus could not be taken by a force of cavalry with no siege equipment, and left the defence of the city to the provincial garrison. Meanwhile he divided his field army and sent units north and east to Aleppo and towards Edessa, Marasah and the borders of Armenia. This threatened to block the Mongol line of retreat, which caused Samaghar to abandon the siege of Damascus and gallop back to the northeast. By the end of November the Mongols were in full retreat back to the Euphrates.

Baibars - no flies on him.

The Mongols were keen on forging an effective alliance with the Franks, though the latter often disappointed. Mongol envoys had previously journeyed to Tunis to treat with the French king, Saint Louis, only to find him on his deathbed. They may have accompanied and advised Edward during his voyage from Tunis to Acre, which would explain why he was quick to send a team of diplomats to the court of the il-khan. His three envoys - Reginald Rossel, Godfrey Waus and John le Parker - underwent a hazardous journey through Mamluk territory to reach the il-khanate; this was set up to control the southwest section of the Mongol Empire, comprising present-day Iran and neighbouring territories.

At first all went swimmingly. The Mongols stormed past Aleppo, forcing the Mamluk garrison to evacuate the town, and then pushed up the Orontes valley past Hamah in west-central Syria. They appeared to be concentrating for an assault on Damascus, where the governor of the city arrived on 9 November to find the citizens in a state of panic. Eleven years earlier Damascus had been sacked by another Mongol warlord, Kitbogha, and memories were still fresh.

As ever in a crisis, Baibars kept a cool head and concentrated on reinforcing his garrisons in northern Syria. He knew Damascus could not be taken by a force of cavalry with no siege equipment, and left the defence of the city to the provincial garrison. Meanwhile he divided his field army and sent units north and east to Aleppo and towards Edessa, Marasah and the borders of Armenia. This threatened to block the Mongol line of retreat, which caused Samaghar to abandon the siege of Damascus and gallop back to the northeast. By the end of November the Mongols were in full retreat back to the Euphrates.

Baibars - no flies on him.

Published on September 16, 2019 09:35

September 15, 2019

The wars of Gwenwynwyn (8, and last)

In 1216 Prince Gwenwynwyn chose to desert Llywelyn ab Iorwerth and go back to King John. He had previously fought for John against Llywelyn, before changing sides.

Gwenwynwyn had played the game pretty well for almost thirty years, ever since he and his brother lured Owain Fychan to Carreg Hofa at night and stuck a dagger in him. Now all his chickens came home to dung on his head, as Llywelyn gathered a grand coalition of Welsh princes to invade Powys:

He [Llywelyn] collected an army and called together nearly all the princes of Wales, and advanced against Powys, taking and subjugating all the land and forcing Gwenwynwyn to flight (Annales Cambriae)

Llywelyn’s hold on southern Powys was confirmed in the Worcester agreements with the government of Henry III in 1218. These set out that the northern prince was to keep all the land he had taken from Gwenwynwyn until the latter’s heirs came of age. He was to provide for the heirs out of the revenues of these lands, while maintaining the dower of Margaret, Gwenwynwyn’s wife, and respecting the existing rights of others.

Llywelyn did not fulfil a single one of these of these provisions. Instead he treated Powys as a conquered territory and ignored Gwenwynwyn’s three sons, who were fostered by Earl Ranulf of Chester. The most forceful of the three, Gruffudd, bore a lifelong grudge against the princes of Gwynedd. Often depicted as a traitor to Wales, Gruffudd had no reason to love the northern princes who murdered his ancestors, invaded and conquered his homeland, destroyed his father and drove him and his brothers into exile. He would eventually get his revenge.

Gwenwynwyn himself died in exile in Cheshire, sometime in 1216. Despite his failure at the end, he held a place of honour in the memory of his descendants. His grandson, Owain ap Gruffudd, was lauded by his poet as ‘wŷr Gwenwynwyn’ or a man like Gwenwynwn. In the fourteenth century Dafydd ap Gwilym, in an elegy or marwnad to his fellow poet Gruffudd ab Adda, praised him as ‘Gwanwyn doth Gwenwynwyn dir’ [any translation welcome…]

Here endeth the saga of Prince Gwenwynwyn ab Owain Cyfeiliog of Powys. There is no more. He lies cold and quiet in his grave. Explicit Liber Terminus.

Gwenwynwyn had played the game pretty well for almost thirty years, ever since he and his brother lured Owain Fychan to Carreg Hofa at night and stuck a dagger in him. Now all his chickens came home to dung on his head, as Llywelyn gathered a grand coalition of Welsh princes to invade Powys:

He [Llywelyn] collected an army and called together nearly all the princes of Wales, and advanced against Powys, taking and subjugating all the land and forcing Gwenwynwyn to flight (Annales Cambriae)

Llywelyn’s hold on southern Powys was confirmed in the Worcester agreements with the government of Henry III in 1218. These set out that the northern prince was to keep all the land he had taken from Gwenwynwyn until the latter’s heirs came of age. He was to provide for the heirs out of the revenues of these lands, while maintaining the dower of Margaret, Gwenwynwyn’s wife, and respecting the existing rights of others.

Llywelyn did not fulfil a single one of these of these provisions. Instead he treated Powys as a conquered territory and ignored Gwenwynwyn’s three sons, who were fostered by Earl Ranulf of Chester. The most forceful of the three, Gruffudd, bore a lifelong grudge against the princes of Gwynedd. Often depicted as a traitor to Wales, Gruffudd had no reason to love the northern princes who murdered his ancestors, invaded and conquered his homeland, destroyed his father and drove him and his brothers into exile. He would eventually get his revenge.

Gwenwynwyn himself died in exile in Cheshire, sometime in 1216. Despite his failure at the end, he held a place of honour in the memory of his descendants. His grandson, Owain ap Gruffudd, was lauded by his poet as ‘wŷr Gwenwynwyn’ or a man like Gwenwynwn. In the fourteenth century Dafydd ap Gwilym, in an elegy or marwnad to his fellow poet Gruffudd ab Adda, praised him as ‘Gwanwyn doth Gwenwynwyn dir’ [any translation welcome…]

Here endeth the saga of Prince Gwenwynwyn ab Owain Cyfeiliog of Powys. There is no more. He lies cold and quiet in his grave. Explicit Liber Terminus.

Published on September 15, 2019 01:19

September 14, 2019

The wars of Gwenwynwyn (7)

In December 1204 King John accused Earl Ranulf of Chester of being in league with Prince Gwenwynwn against the crown. Exactly what the allies were plotting is unclear, but a seed of suspicion was planted in the king’s mind. It may be that John resented Gwenwynwyn’s invasion of the Braose lands in the central March, since Wiliam Braose was the king’s protegé and intended to act as a counter to the power of Earl Ranulf in the north.

King John's tomb

King John's tomb

In 1208 John summoned Gwenwynwyn to Shrewsbury, where he was arrested. Llywelyn ab Iorwerth took this opportunity to march down from Gwynedd and seize all the lands and castles in Powys. At the same time he attacked Maelgwn ap Rhys, Gwenwynwyn’s ally, and forced the homage of most of the lords of South Wales.

Two years later, Gwenwynwyn reconquered southern Powys with the assistance of John:

About the feast of Andrew, Gwenwynwn regained possession of his territory, through the help of King John (Brut)

The Cronica de Wallia records that Gwenwynwyn attacked the castle of ‘Walwernia’ (Tafolwern) and ‘Kereynaun’, which must refer to a castle in Caerenion. At the same time Ranulf of Chester attacked Llywelyn in North Wales and occupied Deganwy, which may have been part of a combined operation against the Venedotians. Maelgwn ap Rhys made peace with the king and raised an army of French and Welsh to drive out Llywelyn’s supporters in the south. He failed, but Gwenwynwyn was left secure (for now) in Powys.

The alliance between Powys and King John was one of convenience. John kept hostages for Gwenwynwyn’s good behaviour, and insisted on keeping the castle of Mathrafal in royal hands.

King John's tomb

King John's tombIn 1208 John summoned Gwenwynwyn to Shrewsbury, where he was arrested. Llywelyn ab Iorwerth took this opportunity to march down from Gwynedd and seize all the lands and castles in Powys. At the same time he attacked Maelgwn ap Rhys, Gwenwynwyn’s ally, and forced the homage of most of the lords of South Wales.

Two years later, Gwenwynwyn reconquered southern Powys with the assistance of John:

About the feast of Andrew, Gwenwynwn regained possession of his territory, through the help of King John (Brut)

The Cronica de Wallia records that Gwenwynwyn attacked the castle of ‘Walwernia’ (Tafolwern) and ‘Kereynaun’, which must refer to a castle in Caerenion. At the same time Ranulf of Chester attacked Llywelyn in North Wales and occupied Deganwy, which may have been part of a combined operation against the Venedotians. Maelgwn ap Rhys made peace with the king and raised an army of French and Welsh to drive out Llywelyn’s supporters in the south. He failed, but Gwenwynwyn was left secure (for now) in Powys.

The alliance between Powys and King John was one of convenience. John kept hostages for Gwenwynwyn’s good behaviour, and insisted on keeping the castle of Mathrafal in royal hands.

Published on September 14, 2019 01:25