David Pilling's Blog, page 43

November 5, 2019

Time for junior

The English king arrived at Berwick on 5 July 1301; by the 12 his army had mustered and consisted of around 6800 footsoldiers. The exceptions were a few mounted officers and light horse or foresters who had been drafted into the army to serve as hobelars. Edward himself was attended by a bodyguard of twenty men, while the rest of his army were all archers save for 20 crossbowmen, 20 miners and 20 masons.

This was even smaller than the army he had taken to Flanders in 1297, and the lack of heavy cavalry - or any cavalry - is notable. It seems the old king intended to play a minor role in the campaign, and wanted his son to have all the credit. Edward had admitted as much in March, when he declared the Prince of Wales should have “the chief honour of taming the pride of the Scots”.

Edward junior was in charge of the main army at Carlisle; about 7000 Welsh and Irish and 1000 English cavalry. This was his time to shine, though he was only in nominal command. His father had given him a minder in the shape of Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, a battle-hardened veteran who was there was to ensure junior didn’t invade the Irish Sea or lead his men over a cliff.

Edward II

Edward II

Prince Edward probably set off from Carlisle in late July. His first target was the lordship of Ayr on the west coast. On 25 August the king received “good rumours” from Sir Malcolm Drummond, a Scottish knight captured by Sir John Segrave. Drummond presumably informed the king of junior’s success in Ayr. A Gascon knight with the interesting name of Sir Montasini de Novelliano was made constable of Ayr Castle, and Sir Edmund Hastings the sheriff. The keepership of the castle and sheriffdom was granted to Patrick, the pro-English Earl of Dunbar.

Whatever resistance the Cambro-Irish-English army encountered as it marched into Ayr is unknown. The capture of this region had taken three years, and was an important gain for the English: they now had control through to the west coast, and could import supplies from Ireland directly to Scotland.

Not much remains of Ayr Castle these days, so above is a pic of the dramatic ruins of Greenan Castle in Ayrshire, built for John Kennedy of Baltersan in 1603.

This was even smaller than the army he had taken to Flanders in 1297, and the lack of heavy cavalry - or any cavalry - is notable. It seems the old king intended to play a minor role in the campaign, and wanted his son to have all the credit. Edward had admitted as much in March, when he declared the Prince of Wales should have “the chief honour of taming the pride of the Scots”.

Edward junior was in charge of the main army at Carlisle; about 7000 Welsh and Irish and 1000 English cavalry. This was his time to shine, though he was only in nominal command. His father had given him a minder in the shape of Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, a battle-hardened veteran who was there was to ensure junior didn’t invade the Irish Sea or lead his men over a cliff.

Edward II

Edward IIPrince Edward probably set off from Carlisle in late July. His first target was the lordship of Ayr on the west coast. On 25 August the king received “good rumours” from Sir Malcolm Drummond, a Scottish knight captured by Sir John Segrave. Drummond presumably informed the king of junior’s success in Ayr. A Gascon knight with the interesting name of Sir Montasini de Novelliano was made constable of Ayr Castle, and Sir Edmund Hastings the sheriff. The keepership of the castle and sheriffdom was granted to Patrick, the pro-English Earl of Dunbar.

Whatever resistance the Cambro-Irish-English army encountered as it marched into Ayr is unknown. The capture of this region had taken three years, and was an important gain for the English: they now had control through to the west coast, and could import supplies from Ireland directly to Scotland.

Not much remains of Ayr Castle these days, so above is a pic of the dramatic ruins of Greenan Castle in Ayrshire, built for John Kennedy of Baltersan in 1603.

Published on November 05, 2019 05:22

November 4, 2019

Horse boys

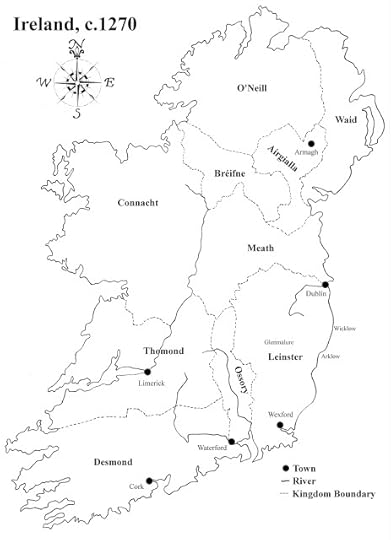

As well as raising large numbers of Welsh infantry for the 1301 campaign, Edward I also exploited the resources of Ireland. The Plantagenets treated the lordship of Ireland as a combination of food factory and recruitment ground; they seldom bothered to visit, and no English king set foot in the country between the reigns of King John and Richard II.

The purveyance in Ireland was to consist of:

3200 quarters of wheat 300 quarters of oats

2000 quarters of malt 500 quarters of beans and peas

200 casks of new wine

10,000 hard fish and 5 lasts of herring

Half of the above was to be sent to Skinburness, the port near Carlisle, and half to a port on the isle of Arran. Since 1298 the isle had been held for Edward I by Sir Hugh Bisset of Antrim, an Irish pirate who earned his knighthood by keeping the Irish Sea clear of Scottish ships. The stores were distributed to the garrisons of Lochmaben, Dumfries and Ayre, as well as the army of the Prince of Wales at Carlisle.

The king also wanted Irish soldiers, and lots of them. He was especially fond of hobelars or ‘horse boys’, light horse ideally suited to the difficult terrain of Ireland and Scotland. Edward’s justiciar of Ireland, John Wogan, haggled over terms of service with the Irish nobility. They drove a hard bargain, and the eventual arrangement was complicated. In return for pardon of two-thirds of their debts at the Exchequer, the Irish nobles agreed to serve in Scotland for 100 days. The remaining one-third would be allowed as wages or as compensation for loss of horses in the campaign. If this did not suffice, Edward guaranteed to pay extra cash to make up the deficit.

The Earl of Ulster, Richard de Burgh, refused to come to terms. Edward had practically begged for his support, informing Burgh that he relied on him “more than any other man in the land for many reasons”. Burgh was fully aware of the king’s desperate need for Irish troops, and wanted to extract the best possible terms for himself.

Even without Burgh’s support, an Irish army of 120 men-at-arms, 178 hobelars and 1200 infantry sailed for Scotland on 9 July in a fleet of 74 ships. They landed at Arran, and went on to join Prince Edward and his Welsh army at Carlisle. All of the Irish served in exchange for remission of debt, and the surviving wage-roll shows how highly the king valued their services: the infantry were paid 6d (pence) a day, three times the normal wage of English or Welsh footsoldiers. One of their troop-leaders, Donald Ruath Macarthi, was also granted an extra pardon of £100 of his debts.

Meanwhile the Earl of Ulster tired of playing politics, and sent a smaller Irish force to Scotland to join the king. This consisted of 4 knights, 42 men-at-arms, 39 squires, 86 hobelars and 128 infantry. These men, led by Eustace de Poer and Thomas de Mandeville, were in pay from 1 July.

[Second pic above is a modern sculpture of an Irish galloglass at Roscommon]

The purveyance in Ireland was to consist of:

3200 quarters of wheat 300 quarters of oats

2000 quarters of malt 500 quarters of beans and peas

200 casks of new wine

10,000 hard fish and 5 lasts of herring

Half of the above was to be sent to Skinburness, the port near Carlisle, and half to a port on the isle of Arran. Since 1298 the isle had been held for Edward I by Sir Hugh Bisset of Antrim, an Irish pirate who earned his knighthood by keeping the Irish Sea clear of Scottish ships. The stores were distributed to the garrisons of Lochmaben, Dumfries and Ayre, as well as the army of the Prince of Wales at Carlisle.

The king also wanted Irish soldiers, and lots of them. He was especially fond of hobelars or ‘horse boys’, light horse ideally suited to the difficult terrain of Ireland and Scotland. Edward’s justiciar of Ireland, John Wogan, haggled over terms of service with the Irish nobility. They drove a hard bargain, and the eventual arrangement was complicated. In return for pardon of two-thirds of their debts at the Exchequer, the Irish nobles agreed to serve in Scotland for 100 days. The remaining one-third would be allowed as wages or as compensation for loss of horses in the campaign. If this did not suffice, Edward guaranteed to pay extra cash to make up the deficit.

The Earl of Ulster, Richard de Burgh, refused to come to terms. Edward had practically begged for his support, informing Burgh that he relied on him “more than any other man in the land for many reasons”. Burgh was fully aware of the king’s desperate need for Irish troops, and wanted to extract the best possible terms for himself.

Even without Burgh’s support, an Irish army of 120 men-at-arms, 178 hobelars and 1200 infantry sailed for Scotland on 9 July in a fleet of 74 ships. They landed at Arran, and went on to join Prince Edward and his Welsh army at Carlisle. All of the Irish served in exchange for remission of debt, and the surviving wage-roll shows how highly the king valued their services: the infantry were paid 6d (pence) a day, three times the normal wage of English or Welsh footsoldiers. One of their troop-leaders, Donald Ruath Macarthi, was also granted an extra pardon of £100 of his debts.

Meanwhile the Earl of Ulster tired of playing politics, and sent a smaller Irish force to Scotland to join the king. This consisted of 4 knights, 42 men-at-arms, 39 squires, 86 hobelars and 128 infantry. These men, led by Eustace de Poer and Thomas de Mandeville, were in pay from 1 July.

[Second pic above is a modern sculpture of an Irish galloglass at Roscommon]

Published on November 04, 2019 02:53

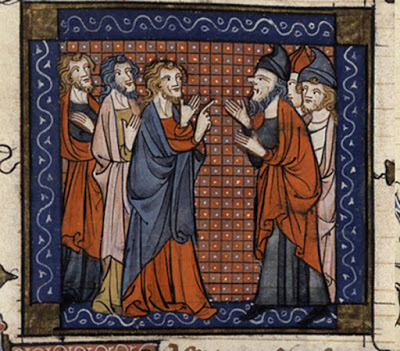

November 3, 2019

Diplomatic bunfights

The truce with the Scots, which began on 31 October 1300, was set to expire on 21 May 1301. On 1 March 1301 Earl Warenne and other English envoys were appointed to meet with envoys of the King of France, to discuss “the rectification of the disobediences, rebellions, contempts, trespasses, injuries, excesses and losses inflicted by the Scots”.

On 26 March the Scottish envoys, led by Master Nicholas Balmyle, were granted safe-conducts to travel south and discuss terms with the English and French representatives at Canterbury. Balmyle and his comrades may well have been outraged at the charges levied against the Scots by King Edward - given what the English got up to in Scotland - but they had to tread carefully. They were a long way from home, entirely under the power of a king who regarded them as traitors.

Why did Edward invite his enemies to talk turkey at Canterbury, in the heart of his realm? It was one way to keep them busy while he prepared for another campaign in Scotland. As early as 3 February, weeks before the talks at Canterbury, he ordered Earl Warenne to muster an army at Berwick, ready to set out “with horses and arms” against the Scots when the truce ended. He always knew what the outcome of the talks would be, though pretended not to. On 8 April his officers in Northumberland were warned to prepare for Scottish attacks, since the king “knew not what may result” from the conference between Scots and French ambassadors at Canterbury.

Edward did know what the result would be. He offered a further truce to the French on condition the Scots were excluded. Philip le Bel was fully engaged with trouble in Flanders, where the Flemish communes were on the point of driving out the French occupiers; just as Wallace and Moray drove the English from Scotland in 1297. The English king was fully aware of the situation, and that the French wanted no distractions in Scotland. Thus, when he offered the truce, Philip’s envoys bit his hand off. Balmyle and his fellow negotiators rejected the treaty, so the war was back on.

On 26 March the Scottish envoys, led by Master Nicholas Balmyle, were granted safe-conducts to travel south and discuss terms with the English and French representatives at Canterbury. Balmyle and his comrades may well have been outraged at the charges levied against the Scots by King Edward - given what the English got up to in Scotland - but they had to tread carefully. They were a long way from home, entirely under the power of a king who regarded them as traitors.

Why did Edward invite his enemies to talk turkey at Canterbury, in the heart of his realm? It was one way to keep them busy while he prepared for another campaign in Scotland. As early as 3 February, weeks before the talks at Canterbury, he ordered Earl Warenne to muster an army at Berwick, ready to set out “with horses and arms” against the Scots when the truce ended. He always knew what the outcome of the talks would be, though pretended not to. On 8 April his officers in Northumberland were warned to prepare for Scottish attacks, since the king “knew not what may result” from the conference between Scots and French ambassadors at Canterbury.

Edward did know what the result would be. He offered a further truce to the French on condition the Scots were excluded. Philip le Bel was fully engaged with trouble in Flanders, where the Flemish communes were on the point of driving out the French occupiers; just as Wallace and Moray drove the English from Scotland in 1297. The English king was fully aware of the situation, and that the French wanted no distractions in Scotland. Thus, when he offered the truce, Philip’s envoys bit his hand off. Balmyle and his fellow negotiators rejected the treaty, so the war was back on.

Published on November 03, 2019 10:55

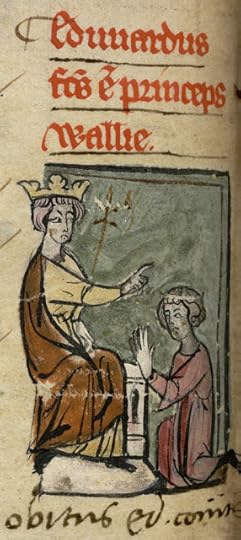

Inheriting the purple

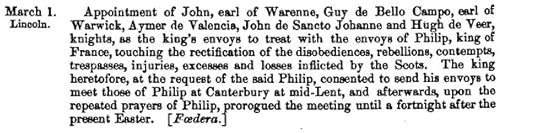

At the Lincoln parliament of 1301, on 7 February, Edward I granted the royal lands in Wales, along with the earldom of Chester, to his son Edward of Caernarfon. This was reminiscent of the grant made to Edward senior by his father, Henry III, forty-seven years earlier, and did not give the heir to the throne any specific title; Edward junior only began to be termed Prince of Wales from May onwards.

The grant may have been related to the forthcoming Scottish campaign. Edward had not raised any Welsh troops for the Galloway campaign in 1300, which proved a mistake as the English raised from the northern counties deserted in large numbers. In 1301 the king planned a two-pronged attack on the Scots; he would lead one army from Berwick, while Prince Edward led another from Carlisle. The idea was to catch the Guardians in a pincer movement and force them to battle.

In what looks like an act of political symbolism, the newly-minted Prince of Wales was given an army of Welshmen. William de Caumvill, Warin Martyn and Morgan ap Maredudd were empowered to raise the men of South and West Wales and ‘bring them to Carlisle by Friday before Midsummer’. The two sons of Hywel ap Meurig, Philip and Rhys, were appointed to pay the infantry conducted to Carlisle. Meanwhile Gruffudd Llwyd, Iwan ap Hywel and several others were appointed to raise the men of North Wales, specifically those of the Four Cantreds and Hopedale.

Carlisle Castle

Carlisle Castle

Among the prince’s army were the sons of loyalist or defeated Welsh princes. Gwilym de la Pole and his brother Gruffudd, two of the sons of Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, served in the retinue of John de Havering, Justiciar of North Wales. The four sons of Madog ap Llywelyn, self-proclaimed Prince of Wales, were transferred from prison to Prince Edward’s bodyguard. As symbolism went, this was fairly blunt: the Plantagenet was master of Wales now, and his son had ‘inherited the purple’, as it were.

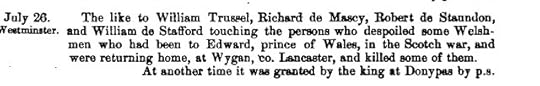

Getting the men up to Carlisle wasn’t an easy process. Warin Martyn, leader of the men of West Wales, later sought and received a pardon for the robberies and murders his men committed while they marched through England. The Welsh weren’t always perpetrators: on 26 July 1302 a commission was set up to investigate the killing of Welsh soldiers, attacked at Wigan in Lancashire on their way back from the Scottish war.

The grant may have been related to the forthcoming Scottish campaign. Edward had not raised any Welsh troops for the Galloway campaign in 1300, which proved a mistake as the English raised from the northern counties deserted in large numbers. In 1301 the king planned a two-pronged attack on the Scots; he would lead one army from Berwick, while Prince Edward led another from Carlisle. The idea was to catch the Guardians in a pincer movement and force them to battle.

In what looks like an act of political symbolism, the newly-minted Prince of Wales was given an army of Welshmen. William de Caumvill, Warin Martyn and Morgan ap Maredudd were empowered to raise the men of South and West Wales and ‘bring them to Carlisle by Friday before Midsummer’. The two sons of Hywel ap Meurig, Philip and Rhys, were appointed to pay the infantry conducted to Carlisle. Meanwhile Gruffudd Llwyd, Iwan ap Hywel and several others were appointed to raise the men of North Wales, specifically those of the Four Cantreds and Hopedale.

Carlisle Castle

Carlisle CastleAmong the prince’s army were the sons of loyalist or defeated Welsh princes. Gwilym de la Pole and his brother Gruffudd, two of the sons of Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, served in the retinue of John de Havering, Justiciar of North Wales. The four sons of Madog ap Llywelyn, self-proclaimed Prince of Wales, were transferred from prison to Prince Edward’s bodyguard. As symbolism went, this was fairly blunt: the Plantagenet was master of Wales now, and his son had ‘inherited the purple’, as it were.

Getting the men up to Carlisle wasn’t an easy process. Warin Martyn, leader of the men of West Wales, later sought and received a pardon for the robberies and murders his men committed while they marched through England. The Welsh weren’t always perpetrators: on 26 July 1302 a commission was set up to investigate the killing of Welsh soldiers, attacked at Wigan in Lancashire on their way back from the Scottish war.

Published on November 03, 2019 01:44

November 2, 2019

Ferrets and sparrows

The truce between the English and Scots in August 1300 gave both sides a chance to rest and recover. We don’t really know what the Guardians did, but the English took the opportunity to stuff their existing garrisons in Scotland with munitions. The logic was to secure the gains made in 1300 and then use them as a springboard for the next campaign after the truce expired in May 1301.

The details of victualling give an exact picture of the English position in Scotland at the turn of the century. They had royal garrisons at Berwick, Jedburgh, Roxburgh, Edinburgh, Dumfries, Lochmaben and Caerlaverock. In addition there were three castles - Hermitage, Dirleton and Dunbar - held by Scottish landholders loyal to King Edward. This meant the king held most of the strongpoints below the Forth, with the exception of Stirling and the castles in the barony of Renfrew; specifically Bothwell and Inverkip. North of the Forth was ‘Free Scotland’, the heartlands held by the Guardians.

To take a random example, Dumfries was supplied with the following:

9 bulls and cows, 14 sheep, 73 quarters and 4 bushels of oats, 70 gallons of wine, unidentified quantities of bread, ale, fish, chickens, almonds and various spices.

Etc. However, Edward wanted to rule Scotland, not just maintain garrisons. For that he needed to set up a working administration that was seen to enforce the law and raise taxes. In 1300, for the first time since he got involved in Scotland, there is an account of revenues raised on behalf of the king. From 30 September Sir John Kingston, sheriff of Edinbugh, collected revenue from the following:

Farms: North Berwick, Tyninghame, Haddington, the town of Edinburgh, Lasswade, Aberlady, Easter Pencaitland, East Niddry and Lowood.

Tolls: Town of Edinburgh.

Tenth (a tax on movables): Inveresk, Lasswade, Roslyn, Aberlady, Ballencrieff and Carrington.

All told, Kingston collected the fair-sized sum of £66 8 shillings and three pence, and a further sum of £25 15s 5d from the farms of Tranent and Seton, the sale of hides and sale of goods belonging to felons in Carrington. Among Kingston’s purchases were ‘sparrows’ and ‘ferrets of Dirleton’. At this point the mind starts to boggle a little bit.

The details of victualling give an exact picture of the English position in Scotland at the turn of the century. They had royal garrisons at Berwick, Jedburgh, Roxburgh, Edinburgh, Dumfries, Lochmaben and Caerlaverock. In addition there were three castles - Hermitage, Dirleton and Dunbar - held by Scottish landholders loyal to King Edward. This meant the king held most of the strongpoints below the Forth, with the exception of Stirling and the castles in the barony of Renfrew; specifically Bothwell and Inverkip. North of the Forth was ‘Free Scotland’, the heartlands held by the Guardians.

To take a random example, Dumfries was supplied with the following:

9 bulls and cows, 14 sheep, 73 quarters and 4 bushels of oats, 70 gallons of wine, unidentified quantities of bread, ale, fish, chickens, almonds and various spices.

Etc. However, Edward wanted to rule Scotland, not just maintain garrisons. For that he needed to set up a working administration that was seen to enforce the law and raise taxes. In 1300, for the first time since he got involved in Scotland, there is an account of revenues raised on behalf of the king. From 30 September Sir John Kingston, sheriff of Edinbugh, collected revenue from the following:

Farms: North Berwick, Tyninghame, Haddington, the town of Edinburgh, Lasswade, Aberlady, Easter Pencaitland, East Niddry and Lowood.

Tolls: Town of Edinburgh.

Tenth (a tax on movables): Inveresk, Lasswade, Roslyn, Aberlady, Ballencrieff and Carrington.

All told, Kingston collected the fair-sized sum of £66 8 shillings and three pence, and a further sum of £25 15s 5d from the farms of Tranent and Seton, the sale of hides and sale of goods belonging to felons in Carrington. Among Kingston’s purchases were ‘sparrows’ and ‘ferrets of Dirleton’. At this point the mind starts to boggle a little bit.

Published on November 02, 2019 04:30

November 1, 2019

The King's Rebels!

My new novella, the latest chapter in the saga of Sir Hugh Longsword, is now available on Kindle!

1277 AD. England prepares for war. Prince Llywelyn of Wales refuses to swear loyalty to the king, Edward I, and dreams of independence for his country. To defy the might of the English crown, Llywelyn will need allies. He looks to the west, to Ireland, where the rebellious Clan MacMurrough plan to set up their chieftain as High King. Together, the Welsh and Irish leaders plan to drive Edward’s forces from their land.

Sir Hugh Longsword is summoned by the king to deal with the crisis. With enemies at home thirsting for his blood, he is only too grateful to be sent to Ireland. There he encounters the galloglass, ferocious Gaelic warriors who will fight to the last man on the battlefield. Hugh has survived civil war in England, but will need all his skill and experience to survive the hell of Irish warfare.

Meanwhile an old friend is at work in Wales. Emma, the girl Hugh once rescued, is also working as a spy for the crown. As he fights in Ireland, she is ordered to break up the confederacy of Welsh princes. United, the king’s rebels may well be strong enough to overcome the English. Divided, King Edward can pick them off one by one. Yet, even as the clouds of war gather on every front, an old threat lurks in the background…

Longsword V: The King’s Rebels is the latest historical adventure novel by David Pilling, author of Reiver, Soldier of Fortune, The Half-Hanged Man, Caesar’s Sword and many more novels and short stories.

Longsword (V) The King's Rebels on Amazon US

Longsword (V) The King's Rebels on Amazon UK

1277 AD. England prepares for war. Prince Llywelyn of Wales refuses to swear loyalty to the king, Edward I, and dreams of independence for his country. To defy the might of the English crown, Llywelyn will need allies. He looks to the west, to Ireland, where the rebellious Clan MacMurrough plan to set up their chieftain as High King. Together, the Welsh and Irish leaders plan to drive Edward’s forces from their land.

Sir Hugh Longsword is summoned by the king to deal with the crisis. With enemies at home thirsting for his blood, he is only too grateful to be sent to Ireland. There he encounters the galloglass, ferocious Gaelic warriors who will fight to the last man on the battlefield. Hugh has survived civil war in England, but will need all his skill and experience to survive the hell of Irish warfare.

Meanwhile an old friend is at work in Wales. Emma, the girl Hugh once rescued, is also working as a spy for the crown. As he fights in Ireland, she is ordered to break up the confederacy of Welsh princes. United, the king’s rebels may well be strong enough to overcome the English. Divided, King Edward can pick them off one by one. Yet, even as the clouds of war gather on every front, an old threat lurks in the background…

Longsword V: The King’s Rebels is the latest historical adventure novel by David Pilling, author of Reiver, Soldier of Fortune, The Half-Hanged Man, Caesar’s Sword and many more novels and short stories.

Longsword (V) The King's Rebels on Amazon US

Longsword (V) The King's Rebels on Amazon UK

Published on November 01, 2019 02:58

October 31, 2019

Peace talks

On 30 October 1300 Edward I concluded a truce with the Scots, through the mediation of Philip le Bel of France, to last until 21 May 1301. This was the first time Edward had agreed to a truce in Scotland, and shows the effectiveness of Scottish resistance after 1296.

According to Rishanger, during the peace talks Edward had threatened to “set light to Scotland from sea to sea” and force the people into submission. This was hardly the language of diplomacy, and most unlikely since the talks ended in a temporary peace. The quote makes for good copy, but is yet another example of monkish chroniclers adding the spicy sauce of invention to the dull pottage of humdrum politics. Or something like that: feel free to invent your own metaphor, because mine is awful.

Edward was certainly in a vile mood, but his rage wasn’t directed at the Scots. He had made some tactical gains on his summer campaign in 1300, but was forced to make peace after his army fell apart. This was due to the mass desertion of the English infantry, which did more to scupper the campaign than the ineffectual efforts of the Guardians under the Earl of Buchan. By early September Edward had just 500 infantry left from the 9000 that had mustered at Carlisle a few weeks earlier.

Why did the infantry desert? There were the usual supply problems, which meant their wages were often overdue. Many were drawn from the northern counties, and preferred to stay at home to protect their families than march about Galloway with the king. While the gentry class in England were still keen on the Scottish war, enthusiasm among the commons had drained away since the first heady rush of war in 1296.

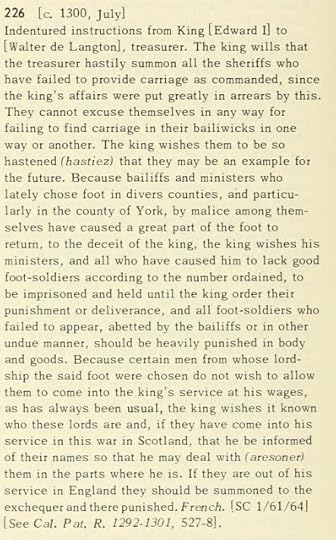

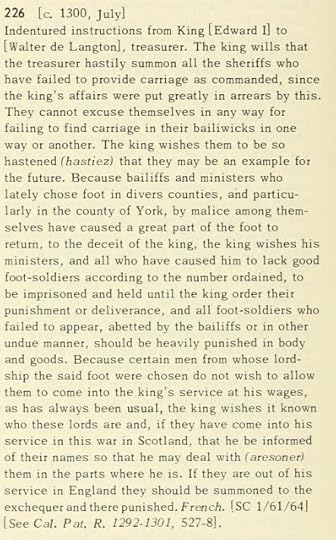

A revealing order went out in July 1300, when the campaign was still in progress. Edward sent a furious letter to the sheriffs in England, ordering them to imprison those bailiffs and ministers responsible for raising infantry: they had, the king claimed, caused a great part of his infantry to desert ‘by malice among themselves’, which suggests some kind of conspiracy. Possibly Edward was just being paranoid, though it is known that local officials were frequently bribed to excuse men from military service.

Lord Hunsdon

Lord Hunsdon

The king particularly blamed the men of the county of York, and this wasn’t the last time Yorkshiremen were suspected of a lack of enthusiasm. A later Warden of the East March, Lord Hunsdon, once caustically remarked that the army of York would not have ‘put their noses over Doncaster bridge’ if others hadn’t ‘beaten the bush for them’.

According to Rishanger, during the peace talks Edward had threatened to “set light to Scotland from sea to sea” and force the people into submission. This was hardly the language of diplomacy, and most unlikely since the talks ended in a temporary peace. The quote makes for good copy, but is yet another example of monkish chroniclers adding the spicy sauce of invention to the dull pottage of humdrum politics. Or something like that: feel free to invent your own metaphor, because mine is awful.

Edward was certainly in a vile mood, but his rage wasn’t directed at the Scots. He had made some tactical gains on his summer campaign in 1300, but was forced to make peace after his army fell apart. This was due to the mass desertion of the English infantry, which did more to scupper the campaign than the ineffectual efforts of the Guardians under the Earl of Buchan. By early September Edward had just 500 infantry left from the 9000 that had mustered at Carlisle a few weeks earlier.

Why did the infantry desert? There were the usual supply problems, which meant their wages were often overdue. Many were drawn from the northern counties, and preferred to stay at home to protect their families than march about Galloway with the king. While the gentry class in England were still keen on the Scottish war, enthusiasm among the commons had drained away since the first heady rush of war in 1296.

A revealing order went out in July 1300, when the campaign was still in progress. Edward sent a furious letter to the sheriffs in England, ordering them to imprison those bailiffs and ministers responsible for raising infantry: they had, the king claimed, caused a great part of his infantry to desert ‘by malice among themselves’, which suggests some kind of conspiracy. Possibly Edward was just being paranoid, though it is known that local officials were frequently bribed to excuse men from military service.

Lord Hunsdon

Lord HunsdonThe king particularly blamed the men of the county of York, and this wasn’t the last time Yorkshiremen were suspected of a lack of enthusiasm. A later Warden of the East March, Lord Hunsdon, once caustically remarked that the army of York would not have ‘put their noses over Doncaster bridge’ if others hadn’t ‘beaten the bush for them’.

Published on October 31, 2019 06:10

October 30, 2019

Team Guardian

On 8 August 1300 the main body of the English army reached the estuary of the Cree in southwest Scotland. The previous day this had been the scene of a skirmish between the Scots and an English foraging party, which ended with the capture of several Scottish knights. Piers Gaveston, Edward II’s future best friend, had sampled the waters of the Cree when his horse was killed under him.

Facing the English, on the western bank of the Cree, was a Scottish army. They were led by the brand-new team of Guardians; the Earl of Buchan, Ingram de Umfraville and John ‘the Red Comyn’ of Badenoch. This was an interesting phase in Scottish leadership: Sir William Wallace was relegated to the sidelines after his defeat at Falkirk, and Robert de Bruce had recently been sacked as Guardian in favour of Umfraville. The defence of Scotland was now in the hands of the Comyn faction.

After the disaster at Falkirk, the general policy of the Scots between 1298-1314 was to avoid open battle. In August 1300 Buchan and his lieutenants decided to risk a confrontation with Edward I, possibly in the hope that a victory would not only end the war, but shove Bruce into his box forever. The omens were not especially good: Buchan’s men had come off worst in skirmishes over the past couple of days, and the high desertion rate of Edward’s infantry still left the small matter of 2000 English knights and men-at-arms to deal with.

Edward also wanted a battle, but wasn’t about to rush into anything. At low tide some of his infantry crossed the ford and exchanged missiles with the Scots. The Prince of Wales rode up and down the bank, watching the skirmish with interest. The king ordered his vanguard to cross the ford. Then he was informed the Scots meant to lure him into an ambush, so he stopped and told the Earl of Hereford to recall the infantry. The footsoldiers mistook Hereford’s approach for the signal to attack, and charged the Scots. Their comrades on the other side rushed over to help, led by Prince Edward at the head of his Castilian lancers.

Edward senior had gone back to his pavilion. A galloper came tearing up to inform him that his only adult male heir had just triggered a general engagement. Cursing, Edward scrambled onto his destrier and roared at Earl Warenne to get on parade. The rickety old Warenne, for whom Scotland was his own private hell, puffed and clambered aboard his horse and followed the king into battle; as he had done for much of the past forty years. Trumpets screamed, and together they led two divisions of cavalry down to the ford. At this point Scottish morale disintegrated.

When the king’s banner was seen advancing into the field - the “three leopards courant gold” - Buchan’s division collapsed and his men fled in all directions. Panic spread through the ranks, as it always did in medieval armies, and the other two divisions were “scattered in a moment like hares in front of greyhounds”. Struck by “excessive fear”, the Scots were driven as far ten leagues into the mountains and groves. Over four hundred were killed in the rout, and all their baggage and equipment fell into English hands. The only recorded casualty on the English side was the loss of a single horse, belonging to one Thomas de Kingsemuthe.

Though a humiliation for Team Guardian, the Cree was not a disaster. Edward had raised no Welsh infantry or light horse for this campaign, so was unable to pursue the Guardians further and wipe them out. Thus, the chronicler concluded, “victory was suspended on both sides”.

Facing the English, on the western bank of the Cree, was a Scottish army. They were led by the brand-new team of Guardians; the Earl of Buchan, Ingram de Umfraville and John ‘the Red Comyn’ of Badenoch. This was an interesting phase in Scottish leadership: Sir William Wallace was relegated to the sidelines after his defeat at Falkirk, and Robert de Bruce had recently been sacked as Guardian in favour of Umfraville. The defence of Scotland was now in the hands of the Comyn faction.

After the disaster at Falkirk, the general policy of the Scots between 1298-1314 was to avoid open battle. In August 1300 Buchan and his lieutenants decided to risk a confrontation with Edward I, possibly in the hope that a victory would not only end the war, but shove Bruce into his box forever. The omens were not especially good: Buchan’s men had come off worst in skirmishes over the past couple of days, and the high desertion rate of Edward’s infantry still left the small matter of 2000 English knights and men-at-arms to deal with.

Edward also wanted a battle, but wasn’t about to rush into anything. At low tide some of his infantry crossed the ford and exchanged missiles with the Scots. The Prince of Wales rode up and down the bank, watching the skirmish with interest. The king ordered his vanguard to cross the ford. Then he was informed the Scots meant to lure him into an ambush, so he stopped and told the Earl of Hereford to recall the infantry. The footsoldiers mistook Hereford’s approach for the signal to attack, and charged the Scots. Their comrades on the other side rushed over to help, led by Prince Edward at the head of his Castilian lancers.

Edward senior had gone back to his pavilion. A galloper came tearing up to inform him that his only adult male heir had just triggered a general engagement. Cursing, Edward scrambled onto his destrier and roared at Earl Warenne to get on parade. The rickety old Warenne, for whom Scotland was his own private hell, puffed and clambered aboard his horse and followed the king into battle; as he had done for much of the past forty years. Trumpets screamed, and together they led two divisions of cavalry down to the ford. At this point Scottish morale disintegrated.

When the king’s banner was seen advancing into the field - the “three leopards courant gold” - Buchan’s division collapsed and his men fled in all directions. Panic spread through the ranks, as it always did in medieval armies, and the other two divisions were “scattered in a moment like hares in front of greyhounds”. Struck by “excessive fear”, the Scots were driven as far ten leagues into the mountains and groves. Over four hundred were killed in the rout, and all their baggage and equipment fell into English hands. The only recorded casualty on the English side was the loss of a single horse, belonging to one Thomas de Kingsemuthe.

Though a humiliation for Team Guardian, the Cree was not a disaster. Edward had raised no Welsh infantry or light horse for this campaign, so was unable to pursue the Guardians further and wipe them out. Thus, the chronicler concluded, “victory was suspended on both sides”.

Published on October 30, 2019 06:36

Skirmishes and ambuscades

After the siege of Caerlaverock in July 1300 the English moved west, along the southern Galloway coast. King Edward’s probable intention was to hunt down the Earl of Buchan, who held Cruggleton on the western banks of the Cree. Buchan was known to be in the area, trying to persuade those Gallovidians who supported Edward to switch to the Scots. The capture of Caerlaverock had strengthened the king’s hold over Galloway, and defeating Buchan would remove another threat.

Buchan seems to have tracked the progress of the English army. All he had to do was wait, as the English infantry were deserting in large numbers; of the 9000 who had originally mustered at Carlisle on 1 July, barely 4500 remained with the king by mid-August. There were no military police in the thirteenth century, and Edward had no means of preventing his footsoldiers from running off home.

Buchan was emboldened enough to go on the offensive. Between 6-9 August a number of skirmishes were fought at the mouth of the river Fleet, where the English men-at-arms were presumably foraging for supplies. Among them was a young Gascon squire named Piers Gaveston, who lost his horse in the fighting. Otherwise these tentative forays were a disaster for the Scots; the marshal of Scotland, Sir Robert Keith, was captured along with Sir Thomas Soules, Robert Barde, William Charteris and Laurence Ramsay. These men, described by the king as some of his “worst enemies”, were sent off to prison in England. Robert Barde in particular was a useful catch, since he and his seven brothers had been wreaking havoc in the Marches.

The Scots then tried a stratagem. One of Buchan’s men approached an English earl and pretended to have deserted the Scots. The earl (which one isn’t stated) gave him command of two hundred soldiers, whom the Scot led into an ambush. Some of the English were killed, but the survivors managed to flee back to the king. Edward immediately sent out more men, who attacked the pursuing Scots and chased them off. According to Rishanger, Buchan’s men were ‘inebriati’, which can mean drunk or light-headed; possibly both. If they had been hitting the booze, that might explain the failure of the ambush.

Despite his victory, Edward was in no mood to celebrate:

“…the losses of the day distressed the king's heart, as what he had hoped for only barely succeeded.”*

The Scottish spy can possibly be identified as one Robert Skort, who was delivered from gaol in Cumberland on 9 September. Skort was described as a Scotsman who had come to the king’s peace on three occasions, and each time defected back to the Scots with information on the state of England. The jury found that he was a spy, but Skort was recommitted to gaol until the king was consulted. At the next gaol delivery, on 7 March 1300, Skort was found guilty of ‘divers robberies’ and hanged.

*Thanks to Rich Price for the translation from Rishanger.

Buchan seems to have tracked the progress of the English army. All he had to do was wait, as the English infantry were deserting in large numbers; of the 9000 who had originally mustered at Carlisle on 1 July, barely 4500 remained with the king by mid-August. There were no military police in the thirteenth century, and Edward had no means of preventing his footsoldiers from running off home.

Buchan was emboldened enough to go on the offensive. Between 6-9 August a number of skirmishes were fought at the mouth of the river Fleet, where the English men-at-arms were presumably foraging for supplies. Among them was a young Gascon squire named Piers Gaveston, who lost his horse in the fighting. Otherwise these tentative forays were a disaster for the Scots; the marshal of Scotland, Sir Robert Keith, was captured along with Sir Thomas Soules, Robert Barde, William Charteris and Laurence Ramsay. These men, described by the king as some of his “worst enemies”, were sent off to prison in England. Robert Barde in particular was a useful catch, since he and his seven brothers had been wreaking havoc in the Marches.

The Scots then tried a stratagem. One of Buchan’s men approached an English earl and pretended to have deserted the Scots. The earl (which one isn’t stated) gave him command of two hundred soldiers, whom the Scot led into an ambush. Some of the English were killed, but the survivors managed to flee back to the king. Edward immediately sent out more men, who attacked the pursuing Scots and chased them off. According to Rishanger, Buchan’s men were ‘inebriati’, which can mean drunk or light-headed; possibly both. If they had been hitting the booze, that might explain the failure of the ambush.

Despite his victory, Edward was in no mood to celebrate:

“…the losses of the day distressed the king's heart, as what he had hoped for only barely succeeded.”*

The Scottish spy can possibly be identified as one Robert Skort, who was delivered from gaol in Cumberland on 9 September. Skort was described as a Scotsman who had come to the king’s peace on three occasions, and each time defected back to the Scots with information on the state of England. The jury found that he was a spy, but Skort was recommitted to gaol until the king was consulted. At the next gaol delivery, on 7 March 1300, Skort was found guilty of ‘divers robberies’ and hanged.

*Thanks to Rich Price for the translation from Rishanger.

Published on October 30, 2019 05:34

October 28, 2019

The sea-girt land of marsh and wood

In July 1300, at the height of an especially wet Scottish summer, the siege of Caerlaverock began. The English herald provides a vivid description of the castle and its surroundings:

“Mighty was Caerlaverock Castle. Siege it feared not, scorned surrender —wherefore came the King in person. Many a resolute defender, well supplied with stores and engines, ‘gainst assault the fortress manned. Shield-shaped, was it. corner-towered, gate and draw-bridge barbican’d. strongly walled, and girt with ditches filled with water brimmingly. Ne’er was castle lovelier sited: westward lay the Irish Sea, north a countryside of beauty by an arm of sea embraced. On two sides, whoe’er approached it danger from the waters faced; nor was easier the southward — sea-girt land of marsh and wood: therefore from the east we neared it, up the slope on which it stood.”

The king divided his army into three squadrons, and the forest of silken banners and pennons made a splendid sight; “aglow was all that place with gold, silver and rich colours”. The herald dwelled on the courage of King Edward’s knights, but the poor bloody infantry were sent in first. They charged at the castle, “discharging arrows, bolts and stones against the hold”. After an hour of exchanging missiles with the defenders, many of the English footsoldiers were dead or maimed. The infantry had been deserting in droves ever since the campaign began - and no wonder, if this was the treatment they could expect.

Then the English knights went in. There was nothing subtle about the assault; they simply charged on foot and tried to batter down the gates. Stones were dropped on their heads; “as caps and helms would pound to dust, shatter shields and batter targes; kill and wound was now their lust.” The herald praises the courage of individual knights (but not the peasants, naturally). Sir Robert Willoughby disdained to carry a shield, and so took a crossbow bolt to the chest. Ralph de Gorges stood under a hail of rocks and ‘refused to depart’; a knight named ‘le Kirkbride’ was virtually buried under a hail of rocks, bolts and arrows. Sir Robert Tony, dressed all in white, managed to climb onto the rampart and fight the Scots hand to hand.

Among the host were some Breton knights, led by the king’s nephew John of Brittany. These men forced the gates - “fierce as mountain lions were they, and their weapons wielded well” - but were pushed back by the defenders.

While “the fray continued fierce day and night”, a monk of Durham named Brother Robert prepared four great war-engines that had been dragged up from Berwick. One of these was called Robinet and would be used again at the siege of Stirling. These engines battered the castle, “devastating in their action, such that neither fort nor tower could withstand their mighty pounding”.

At last the roof of the gatehouse was smashed in, and most of the exhausted defenders offered to surrender. One of the Scots raised a flag to signal parley, only to be shot through the hand and face by an enraged archer who had no desire to yield. He was a lone voice, and the others agreed to surrender Caerlaverock to the king’s “mercy and grace”. Around sixty Scots survived the siege. The constable, Walter Benechase, and eleven of his fellows were sent off to prison at Newcastle. The fate of the others is unknown, though some were probably hanged.Caerlaverock was then granted to Robert Clifford, after which the army departed:

“Then the war-wise King directed how the army should be led, by what roads and by what passes, through the hostile land ahead.”

“Mighty was Caerlaverock Castle. Siege it feared not, scorned surrender —wherefore came the King in person. Many a resolute defender, well supplied with stores and engines, ‘gainst assault the fortress manned. Shield-shaped, was it. corner-towered, gate and draw-bridge barbican’d. strongly walled, and girt with ditches filled with water brimmingly. Ne’er was castle lovelier sited: westward lay the Irish Sea, north a countryside of beauty by an arm of sea embraced. On two sides, whoe’er approached it danger from the waters faced; nor was easier the southward — sea-girt land of marsh and wood: therefore from the east we neared it, up the slope on which it stood.”

The king divided his army into three squadrons, and the forest of silken banners and pennons made a splendid sight; “aglow was all that place with gold, silver and rich colours”. The herald dwelled on the courage of King Edward’s knights, but the poor bloody infantry were sent in first. They charged at the castle, “discharging arrows, bolts and stones against the hold”. After an hour of exchanging missiles with the defenders, many of the English footsoldiers were dead or maimed. The infantry had been deserting in droves ever since the campaign began - and no wonder, if this was the treatment they could expect.

Then the English knights went in. There was nothing subtle about the assault; they simply charged on foot and tried to batter down the gates. Stones were dropped on their heads; “as caps and helms would pound to dust, shatter shields and batter targes; kill and wound was now their lust.” The herald praises the courage of individual knights (but not the peasants, naturally). Sir Robert Willoughby disdained to carry a shield, and so took a crossbow bolt to the chest. Ralph de Gorges stood under a hail of rocks and ‘refused to depart’; a knight named ‘le Kirkbride’ was virtually buried under a hail of rocks, bolts and arrows. Sir Robert Tony, dressed all in white, managed to climb onto the rampart and fight the Scots hand to hand.

Among the host were some Breton knights, led by the king’s nephew John of Brittany. These men forced the gates - “fierce as mountain lions were they, and their weapons wielded well” - but were pushed back by the defenders.

While “the fray continued fierce day and night”, a monk of Durham named Brother Robert prepared four great war-engines that had been dragged up from Berwick. One of these was called Robinet and would be used again at the siege of Stirling. These engines battered the castle, “devastating in their action, such that neither fort nor tower could withstand their mighty pounding”.

At last the roof of the gatehouse was smashed in, and most of the exhausted defenders offered to surrender. One of the Scots raised a flag to signal parley, only to be shot through the hand and face by an enraged archer who had no desire to yield. He was a lone voice, and the others agreed to surrender Caerlaverock to the king’s “mercy and grace”. Around sixty Scots survived the siege. The constable, Walter Benechase, and eleven of his fellows were sent off to prison at Newcastle. The fate of the others is unknown, though some were probably hanged.Caerlaverock was then granted to Robert Clifford, after which the army departed:

“Then the war-wise King directed how the army should be led, by what roads and by what passes, through the hostile land ahead.”

Published on October 28, 2019 01:10