David Pilling's Blog, page 40

December 8, 2019

A judgement of blood

In 1305, as most of us are aware, William Wallace was executed in London. That year witnessed another ‘state trial’, just as notorious at the time in England, though all but forgotten now.

The trial concerned Nicholas Segrave, younger brother of the John Segrave who was captured at the battle of Roslin and later presided over the sentencing of Wallace. In 1304, when the English army was in Scoland, Segrave quarrelled with another knight, John Cromwell, and challenged him to trial by combat.

Segrave knew the king would forbid the duel, and so asked Cromwell to accompany him to the French court in Paris, where trials by combat were permitted. Cromwell’s response is unknown, but Segrave deserted the army and fled south. He was arrested at Dover while trying to find a ship to carry him to France. While he awaited trial at Westminster, Segrave was imprisoned at Dover Castle. King Edward caustically ordered the constable of Dover to allow Segrave to exercise in the castle grounds, since “we well know that knight has no little talent for escape”.

Segrave was brought to trial in February 1305. He was charged with deserting the army in time of war, thus exposing the king to danger from his enemies. He was also charged with adjourning his case to the French court, thus subjecting the king and realm to the authority of a foreign power. After three days of deliberation, the earls and barons of England gave judgement that Segrave was guilty of treason, and therefore the penalty was death. They also gratuitously informed the king that he might show mercy, if he chose. At this Edward snapped:

“Fools - of course I can, but I will give no more mercy, just for your sake, than I would show a dog!”

When his feathers had settled down a bit, Edward declared he preferred the life to the death of one who had submitted to his will. Therefore he reversed the judgement of blood and decreed that Segrave should be pardoned and allowed to go free. In exchange the prisoner would find seven men to act as sureties for his future good behaviour. These sureties were called ‘manucaptors’, and they undertook to deliver Segrave to prison if he offended again.

The acquittal of Segrave stands in contrast to the judgement on Wallace, just a few months later. Edward’s attitude was not coloured by one being an Englishman and the other a Scot: the king did not comprehend nationalism and regarded the two peoples as being one and the same, certainly at aristocratic level. Possibly Segrave was pardoned because he submitted himself to the king’s grace and will, which Wallace refused to do.

The trial concerned Nicholas Segrave, younger brother of the John Segrave who was captured at the battle of Roslin and later presided over the sentencing of Wallace. In 1304, when the English army was in Scoland, Segrave quarrelled with another knight, John Cromwell, and challenged him to trial by combat.

Segrave knew the king would forbid the duel, and so asked Cromwell to accompany him to the French court in Paris, where trials by combat were permitted. Cromwell’s response is unknown, but Segrave deserted the army and fled south. He was arrested at Dover while trying to find a ship to carry him to France. While he awaited trial at Westminster, Segrave was imprisoned at Dover Castle. King Edward caustically ordered the constable of Dover to allow Segrave to exercise in the castle grounds, since “we well know that knight has no little talent for escape”.

Segrave was brought to trial in February 1305. He was charged with deserting the army in time of war, thus exposing the king to danger from his enemies. He was also charged with adjourning his case to the French court, thus subjecting the king and realm to the authority of a foreign power. After three days of deliberation, the earls and barons of England gave judgement that Segrave was guilty of treason, and therefore the penalty was death. They also gratuitously informed the king that he might show mercy, if he chose. At this Edward snapped:

“Fools - of course I can, but I will give no more mercy, just for your sake, than I would show a dog!”

When his feathers had settled down a bit, Edward declared he preferred the life to the death of one who had submitted to his will. Therefore he reversed the judgement of blood and decreed that Segrave should be pardoned and allowed to go free. In exchange the prisoner would find seven men to act as sureties for his future good behaviour. These sureties were called ‘manucaptors’, and they undertook to deliver Segrave to prison if he offended again.

The acquittal of Segrave stands in contrast to the judgement on Wallace, just a few months later. Edward’s attitude was not coloured by one being an Englishman and the other a Scot: the king did not comprehend nationalism and regarded the two peoples as being one and the same, certainly at aristocratic level. Possibly Segrave was pardoned because he submitted himself to the king’s grace and will, which Wallace refused to do.

Published on December 08, 2019 05:51

December 7, 2019

It's a trap!

Lacy’s war.

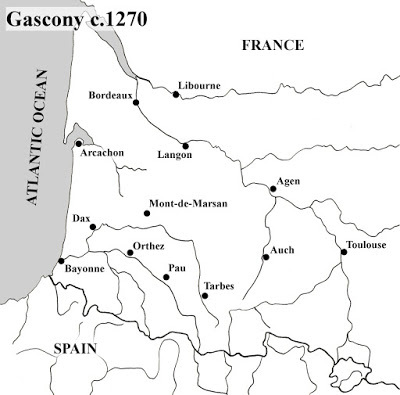

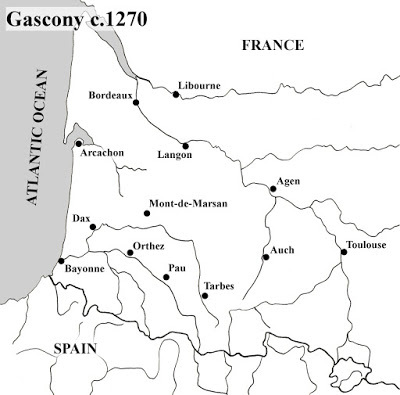

As they lay siege to Bourg in the summer of 1296, the French also attacked Bellegarde, a ducal bastide on the edge of English-held territory in southeast Gascony. The English are said to have ‘thrown themselves’ into Bellegarde, implying the attack was unexpected.

The French were led by Jean de Brienne, the young Count of Eu, and the provost of Toulouse. Neither seems to have been over-endowed with brains. When they arrived before the town, they found the gates had been left open. In the ‘boldness of his mind’, the young count decided to charge through the gates with a few followers, leaving the rest of his army outside.

Surprise, surprise - it was a trap. The gates clanged shut and the English rushed out from hiding. They put all the French to the sword with the exception of Jean himself, who was impaled with a lance. Incredibly, he survived and was ransomed, only to die six years later in the muddy carnage of Courtrai.

His lieutenant, the provost, decided now was the time for a really futile gesture. He drew his sword, leaped over the ditch under the walls of Bellegarde and cut through the nearest ropes. Alas, he failed to notice the ropes were attached to some beams on the battlements, upon which the citizens had placed baskets full of stones. The beams now overturned and tipped the stones onto his head, crushing him to death.

After witnessing this spectacular display of tomfoolery by their commanders, the French decided to call it a day and withdraw. And who can blame them.

The above pic is of the massive triple walled fortress built in the 18th century on top of the old medieval fortification at Bellegarde, to guard the borders of the First French Republic.

As they lay siege to Bourg in the summer of 1296, the French also attacked Bellegarde, a ducal bastide on the edge of English-held territory in southeast Gascony. The English are said to have ‘thrown themselves’ into Bellegarde, implying the attack was unexpected.

The French were led by Jean de Brienne, the young Count of Eu, and the provost of Toulouse. Neither seems to have been over-endowed with brains. When they arrived before the town, they found the gates had been left open. In the ‘boldness of his mind’, the young count decided to charge through the gates with a few followers, leaving the rest of his army outside.

Surprise, surprise - it was a trap. The gates clanged shut and the English rushed out from hiding. They put all the French to the sword with the exception of Jean himself, who was impaled with a lance. Incredibly, he survived and was ransomed, only to die six years later in the muddy carnage of Courtrai.

His lieutenant, the provost, decided now was the time for a really futile gesture. He drew his sword, leaped over the ditch under the walls of Bellegarde and cut through the nearest ropes. Alas, he failed to notice the ropes were attached to some beams on the battlements, upon which the citizens had placed baskets full of stones. The beams now overturned and tipped the stones onto his head, crushing him to death.

After witnessing this spectacular display of tomfoolery by their commanders, the French decided to call it a day and withdraw. And who can blame them.

The above pic is of the massive triple walled fortress built in the 18th century on top of the old medieval fortification at Bellegarde, to guard the borders of the First French Republic.

Published on December 07, 2019 01:52

December 6, 2019

Lacy's war

In July 1296 the French army under Robert of Artois laid siege to Bourg. Along with Blaye, this was one of just two remaining English strongholds in northern Gascony. If it fell, Blaye would soon follow, and half the duchy would be lost.

One of the hazards of campaigning in Aquitaine, especially in high summer, was the prevalence of heat and subsequent disease. Artois himself was not a well man. His household accounts show frequent payments for medicines from April to July, used for himself and members of his household. These include syrups, potions, cordials and electuaries, probably used to treat fever and dysentery. While he lay siege to Bourg, supplies of rose-water, pomegranates, camomile and other herbs were bought specifically for Artois at Bordeaux and Bergerac, and then carried to the French camp.

Rather than sweat and poo himself to death, Artois handed over command of the siege to the Sire de Sully, a French knight, and went off to recover elsewhere. He continued to be treated with an increasingly bizzare set of medicines, including crystallized rose petals and violets, Damascus rose-water and fifty pomegranates. To keep his spirits up, the count was entertained by a fool and a female dwarf. The mind boggles.

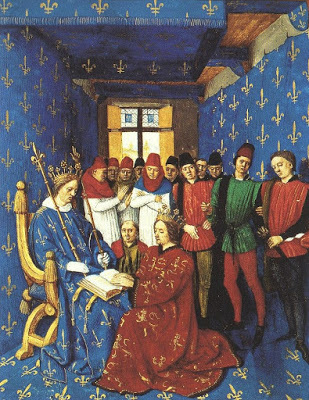

Meanwhile the French continued to bombard the town. It seemed Bourg must fall, but then cometh the hour, cometh the man. The man was Sir Simon Montague, a knight of Somerset. Simon, described as ‘miles strenuus et cordatus’ - a valiant and prudent knight - grabbed a supply ship, sailed it down the Gironde and smashed through the French blockade to bring vital provisions to Bourg.

Meanwhile the French continued to bombard the town. It seemed Bourg must fall, but then cometh the hour, cometh the man. The man was Sir Simon Montague, a knight of Somerset. Simon, described as ‘miles strenuus et cordatus’ - a valiant and prudent knight - grabbed a supply ship, sailed it down the Gironde and smashed through the French blockade to bring vital provisions to Bourg.

Seeing this, the Sire de Sully gave up and withdrew. Edward I sent a letter contragulating the garrison on their successful defence, and fresh supplies of corn, hay, beans, bacon and other victuals were rushed over from England to stock the town.

One of the hazards of campaigning in Aquitaine, especially in high summer, was the prevalence of heat and subsequent disease. Artois himself was not a well man. His household accounts show frequent payments for medicines from April to July, used for himself and members of his household. These include syrups, potions, cordials and electuaries, probably used to treat fever and dysentery. While he lay siege to Bourg, supplies of rose-water, pomegranates, camomile and other herbs were bought specifically for Artois at Bordeaux and Bergerac, and then carried to the French camp.

Rather than sweat and poo himself to death, Artois handed over command of the siege to the Sire de Sully, a French knight, and went off to recover elsewhere. He continued to be treated with an increasingly bizzare set of medicines, including crystallized rose petals and violets, Damascus rose-water and fifty pomegranates. To keep his spirits up, the count was entertained by a fool and a female dwarf. The mind boggles.

Meanwhile the French continued to bombard the town. It seemed Bourg must fall, but then cometh the hour, cometh the man. The man was Sir Simon Montague, a knight of Somerset. Simon, described as ‘miles strenuus et cordatus’ - a valiant and prudent knight - grabbed a supply ship, sailed it down the Gironde and smashed through the French blockade to bring vital provisions to Bourg.

Meanwhile the French continued to bombard the town. It seemed Bourg must fall, but then cometh the hour, cometh the man. The man was Sir Simon Montague, a knight of Somerset. Simon, described as ‘miles strenuus et cordatus’ - a valiant and prudent knight - grabbed a supply ship, sailed it down the Gironde and smashed through the French blockade to bring vital provisions to Bourg.Seeing this, the Sire de Sully gave up and withdrew. Edward I sent a letter contragulating the garrison on their successful defence, and fresh supplies of corn, hay, beans, bacon and other victuals were rushed over from England to stock the town.

Published on December 06, 2019 07:08

December 5, 2019

Don't panic!

Lacy’s war.

On 5 June 1296 Edmund of Lancaster died at Bayonne, aged fifty-one. He died in a state of self-recrimination: in his will he asked for his bones to remain unburied until his debts were paid, and he bequeathed to his lieutenant, Henry de Lacy, a failed and bankrupt enterprise in Gascony.

Edmund’s body was carried back to England and interred at Westminster Abbey on 15 July. The king requested prayers for:

“Our dearest and only brother, who was always devoted and faithful to us, and to the affairs of our realm, and in whom valour and many gifts of grace shone forth.”

Lacy was left holding the baby. He took on the new title of ‘Capitaneus’ or commander-in-chief in time of war with full emergency powers. This reflected the crisis facing the English in Aquitaine, and Lacy’s isolation, cut off from support in England.

The new C-o-C found himself in charge of an army that was demoralised after successive defeats, disintegrating for lack of pay and threatened by a much larger French army. This dire situation called for an inspiring military genius who could stiffen the tigers and rally the sinews, and all that sort of thing.

In short, the English in Aquitaine needed Henry V. What they got was Sergeant Wilson. Lacy was said to be handsome and debonair - debonair in the medieval sense, meaning one who conformed to accepted chivalric behaviour - but as a soldier he was stolid, plodding and unimaginative. His saving grace was a total refusal to admit defeat, even in the face of odds that would have reduced less thick-skinned men to quaking jelly.

Bourg

Bourg

Nor was he stupid. His first act was to abandon the hopeless offensive strategy, and revert to defending those citadels in Aquitaine that remained in English hands. The war now turned into a holding operation, established on the main operational base of Bayonne in the south. Bayonne also served as an alternative capital for the English while the French occupied Bordeaux.

This meant that the French had to extend their supply lines, and were faced with the uphill task of demolishing enemy citadels. It was a weary prospect, similar to the situation facing the English in Scotland, but they had to continue what they started. In July, at the height of a roasting summer, the Comte d’Artois marched on the strongpoint of Bourg in northern Gascony.

On 5 June 1296 Edmund of Lancaster died at Bayonne, aged fifty-one. He died in a state of self-recrimination: in his will he asked for his bones to remain unburied until his debts were paid, and he bequeathed to his lieutenant, Henry de Lacy, a failed and bankrupt enterprise in Gascony.

Edmund’s body was carried back to England and interred at Westminster Abbey on 15 July. The king requested prayers for:

“Our dearest and only brother, who was always devoted and faithful to us, and to the affairs of our realm, and in whom valour and many gifts of grace shone forth.”

Lacy was left holding the baby. He took on the new title of ‘Capitaneus’ or commander-in-chief in time of war with full emergency powers. This reflected the crisis facing the English in Aquitaine, and Lacy’s isolation, cut off from support in England.

The new C-o-C found himself in charge of an army that was demoralised after successive defeats, disintegrating for lack of pay and threatened by a much larger French army. This dire situation called for an inspiring military genius who could stiffen the tigers and rally the sinews, and all that sort of thing.

In short, the English in Aquitaine needed Henry V. What they got was Sergeant Wilson. Lacy was said to be handsome and debonair - debonair in the medieval sense, meaning one who conformed to accepted chivalric behaviour - but as a soldier he was stolid, plodding and unimaginative. His saving grace was a total refusal to admit defeat, even in the face of odds that would have reduced less thick-skinned men to quaking jelly.

Bourg

BourgNor was he stupid. His first act was to abandon the hopeless offensive strategy, and revert to defending those citadels in Aquitaine that remained in English hands. The war now turned into a holding operation, established on the main operational base of Bayonne in the south. Bayonne also served as an alternative capital for the English while the French occupied Bordeaux.

This meant that the French had to extend their supply lines, and were faced with the uphill task of demolishing enemy citadels. It was a weary prospect, similar to the situation facing the English in Scotland, but they had to continue what they started. In July, at the height of a roasting summer, the Comte d’Artois marched on the strongpoint of Bourg in northern Gascony.

Published on December 05, 2019 06:43

Nobody needs a war

JR Strayer, biographer of Philip le Bel, on the reasons for the war in Aquitaine.

“No one has ever satisfactorily explained why Philip IV drifted into war with Edward I of England in 1294. The Treaty of Paris in 1259 had made the king of England, in his capacity of Duke of Aquitaine, a vassal of the king of France, but it had not stated expressly what the obligations of the duke were, nor had it defined the boundaries of the duchy. In fact the matter of boundaries was left for later negotiations, negotiations that dragged on for decades.

Edward was anxious to avoid war with France at almost any cost. His objectives were not unlike Philip’s; he wanted above everything else to be recognized as sovereign throughout the island of Great Britain. Wales was his Aquitaine, Scotland was his Flanders, and he was having serious troubles with both of them. The last thing in the world he wanted was a war on the continent.

In accepting terms, Edward had demonstrated that he did not want a war. Philip should have then realized that he did not need a war. Edward had clearly recognized the sovereignty of the king of France, and the token occupation force could have acted as a tripwire to prevent any attempt to weaken that sovereignty. Instead Philip sent in a large army, made it impossible for Edward to defend himself in the Parlement by refusing a safe-conduct, and thus forced Edward to renounce his allegiance.

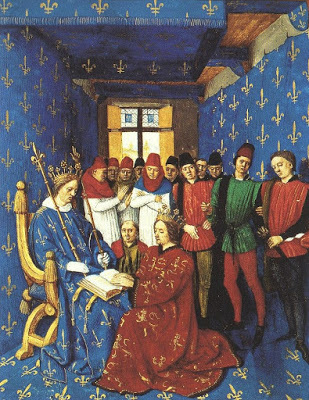

Philip le Bel

Philip le Bel

Both countries found it difficult to pay for wars that they really wanted to win - the English conquest of Scotland and the French conquest of Flanders - because they wasted so much on a war they had not desired”.

All of which dovetails neatly with the bare statistics for Edward’s Scottish wars. Between 1298-1302 he found it difficult to pay his troops in Scotland, which led to mass desertions and scuppered one campaign after another. This was a direct consequence of the war in Aquitaine, which Edward had done his best to avoid: along with the Flanders campaign, it devoured precisely 85% of his available financial resources. Such a drain had an inevitable knock-on effect.

Edward I

Edward I

In light of which, it seems incredible that Edward was able to gather himself for one final push in Scotland in 1303. Even this was directly connected to affairs on the continent, as his last Scottish campaign kicked off on the very day that Gascony was restored to the English. If there had been no war with France, one has to wonder how the Scottish wars of independence might have turned out.

“No one has ever satisfactorily explained why Philip IV drifted into war with Edward I of England in 1294. The Treaty of Paris in 1259 had made the king of England, in his capacity of Duke of Aquitaine, a vassal of the king of France, but it had not stated expressly what the obligations of the duke were, nor had it defined the boundaries of the duchy. In fact the matter of boundaries was left for later negotiations, negotiations that dragged on for decades.

Edward was anxious to avoid war with France at almost any cost. His objectives were not unlike Philip’s; he wanted above everything else to be recognized as sovereign throughout the island of Great Britain. Wales was his Aquitaine, Scotland was his Flanders, and he was having serious troubles with both of them. The last thing in the world he wanted was a war on the continent.

In accepting terms, Edward had demonstrated that he did not want a war. Philip should have then realized that he did not need a war. Edward had clearly recognized the sovereignty of the king of France, and the token occupation force could have acted as a tripwire to prevent any attempt to weaken that sovereignty. Instead Philip sent in a large army, made it impossible for Edward to defend himself in the Parlement by refusing a safe-conduct, and thus forced Edward to renounce his allegiance.

Philip le Bel

Philip le BelBoth countries found it difficult to pay for wars that they really wanted to win - the English conquest of Scotland and the French conquest of Flanders - because they wasted so much on a war they had not desired”.

All of which dovetails neatly with the bare statistics for Edward’s Scottish wars. Between 1298-1302 he found it difficult to pay his troops in Scotland, which led to mass desertions and scuppered one campaign after another. This was a direct consequence of the war in Aquitaine, which Edward had done his best to avoid: along with the Flanders campaign, it devoured precisely 85% of his available financial resources. Such a drain had an inevitable knock-on effect.

Edward I

Edward IIn light of which, it seems incredible that Edward was able to gather himself for one final push in Scotland in 1303. Even this was directly connected to affairs on the continent, as his last Scottish campaign kicked off on the very day that Gascony was restored to the English. If there had been no war with France, one has to wonder how the Scottish wars of independence might have turned out.

Published on December 05, 2019 02:04

December 4, 2019

Lacy's war

Shortly before he died, Edmund of Lancaster was offered an eleventh-hour shot at redemption. In late April 1296 five citizens of Bordeaux came to the English camp and, in return for £5000 in silver, agreed to secretly open the city gates at dawn two days hence. When the English entered, they would slaughter everyone who was not wearing the badge of St George: this was presumably the red cross against a white field.

La Rochelle

La Rochelle

It all went wrong. The plot was discovered, and the five citizens arrested and hanged when they returned to Bordeaux. When the English arrived, it was to find the gates firmly shut against them. After the failure of this last gambit, Edmund went south to Bayonne to die.

As he lay on his deathbed, the people of Bayonne made a remarkable gesture of loyalty. On 14 May, at their request, Edward I declared the community of Bayonne had been united indissolubly to the English crown. If the French conquered Gascony, the Bayonnais would not submit to the King of France in Paris; instead they would fight to the last man, or take to the sea as pirates.

The Bayonnais had motives beyond simple loyalty. When the French war began, in 1294, the town of Bayonne was split between two factions. These were the mariners, led by Pascal de Vielle, and an aristocratic party led by the Manx family. The aristocrats had sided with the French and driven Pascal and his friends into exile. Pascal offered his services to the English, and together they recaptured Bayonne later in the year. The Manx were driven out. As a reward for linking Bayonne forever to the English crown, King Edward granted the mariners all the plum jobs. Pascal was made mayor, castellan and provost, and given access for five years to all the rents and revenues of Bayonne. The smiths of Bayonne, meanwhile, were guaranteed protection against the entry of competing iron manufactures.

Bayonne

Bayonne

There was also recent history to take into account. The Bayonnais were notorious pirates, and had sacked the French coastal town of La Rochelle. By severing all ties with the French government, they could not be prosecuted by Philip le Bel’s lawyers. Thus their show of loyalty was also an insurance policy.

Edward’s most significant appointment turned out to be his wisest one with regard to this war. He appointed a Bayonnais sea-captain, Barran de Sescars, to supreme naval command of the entire Anglo-Gascon fleet. It was largely thanks to Barran, a forgotten individual, that the English held onto Aquitaine for another 150 years.

La Rochelle

La RochelleIt all went wrong. The plot was discovered, and the five citizens arrested and hanged when they returned to Bordeaux. When the English arrived, it was to find the gates firmly shut against them. After the failure of this last gambit, Edmund went south to Bayonne to die.

As he lay on his deathbed, the people of Bayonne made a remarkable gesture of loyalty. On 14 May, at their request, Edward I declared the community of Bayonne had been united indissolubly to the English crown. If the French conquered Gascony, the Bayonnais would not submit to the King of France in Paris; instead they would fight to the last man, or take to the sea as pirates.

The Bayonnais had motives beyond simple loyalty. When the French war began, in 1294, the town of Bayonne was split between two factions. These were the mariners, led by Pascal de Vielle, and an aristocratic party led by the Manx family. The aristocrats had sided with the French and driven Pascal and his friends into exile. Pascal offered his services to the English, and together they recaptured Bayonne later in the year. The Manx were driven out. As a reward for linking Bayonne forever to the English crown, King Edward granted the mariners all the plum jobs. Pascal was made mayor, castellan and provost, and given access for five years to all the rents and revenues of Bayonne. The smiths of Bayonne, meanwhile, were guaranteed protection against the entry of competing iron manufactures.

Bayonne

BayonneThere was also recent history to take into account. The Bayonnais were notorious pirates, and had sacked the French coastal town of La Rochelle. By severing all ties with the French government, they could not be prosecuted by Philip le Bel’s lawyers. Thus their show of loyalty was also an insurance policy.

Edward’s most significant appointment turned out to be his wisest one with regard to this war. He appointed a Bayonnais sea-captain, Barran de Sescars, to supreme naval command of the entire Anglo-Gascon fleet. It was largely thanks to Barran, a forgotten individual, that the English held onto Aquitaine for another 150 years.

Published on December 04, 2019 09:17

Lacy's war

After failing to take Bordeaux, Edmund of Lancaster and Henry de Lacy marched on to Langon, a few miles southeast down the Gironde river. These days Langon lies adjacent to a wine-growing region and the Landes forest, and is home to a very nice medieval church which was presumably there when the English showed up in 1296.

Edmund was on his last legs, but at least had the satisfaction of seeing the French garrison at Langon run away. The Langonnais were loyalists and freely surrendered their town to the forces of the king-duke. Nearby lay the town of Rions, but this was no longer a strategic objective since the French had dismantled its defences in the previous year.

Now installed as lieutenant of Langon, Edmund sent a message to the town of St Macaire, ordering the inhabitants to surrender. One of the confusing aspects of the war in Gascony is the plethora of mixed loyalties: the people of St Macaire chose to support the French, and obtained a truce from Edmund for three days. They used that time to ask for help from the French garrison at Bordeaux, and when this failed to arrive the town duly offered its surrender.

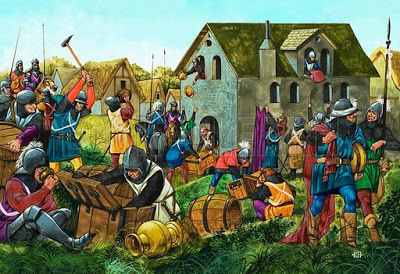

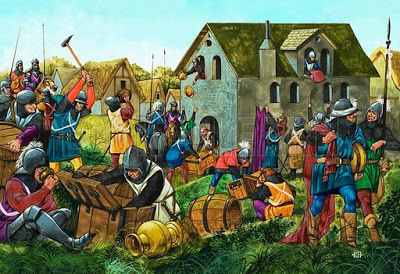

The French in the castle, led by Thibaut de Cheppoix, chose to resist. Edmund laid siege, but the garrison resisted daily assaults for three weeks. At the same time Edmund’s Gascon troops under the Captal de Buch and other nobles pillaged the town without mercy. A later petition revealed that the Gascons stole wine, oats, corn, hay, bread and other victuals from the burgesses. A citizen named Gaillard Ayquem, at that time being held hostage by the French, complained that his property had been ransacked: four coffers were broken open, six feather pillows and eight sheets removed, two cloaks and many bedcovers and hangings looted, grain taken from his storehouse, while his servant had been stripped of his shirt and held prisoner for three days.

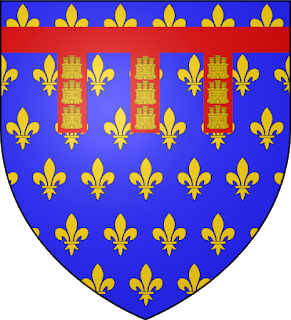

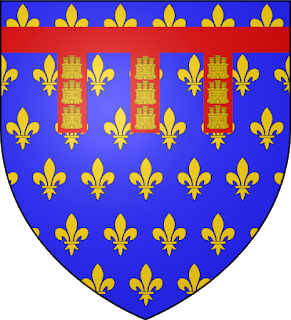

This was no way to win hearts and minds. The approach of a French army under the Comte d’Artois (coat of arms attached) forced Edmund to raise the siege, and the disgruntled citizens promptly opened their gates to the enemy.

Edmund was out of luck, out of money and almost out of time. ‘His face fell’, reports the chronicler, and he was sick in body and spirit.

Edmund was on his last legs, but at least had the satisfaction of seeing the French garrison at Langon run away. The Langonnais were loyalists and freely surrendered their town to the forces of the king-duke. Nearby lay the town of Rions, but this was no longer a strategic objective since the French had dismantled its defences in the previous year.

Now installed as lieutenant of Langon, Edmund sent a message to the town of St Macaire, ordering the inhabitants to surrender. One of the confusing aspects of the war in Gascony is the plethora of mixed loyalties: the people of St Macaire chose to support the French, and obtained a truce from Edmund for three days. They used that time to ask for help from the French garrison at Bordeaux, and when this failed to arrive the town duly offered its surrender.

The French in the castle, led by Thibaut de Cheppoix, chose to resist. Edmund laid siege, but the garrison resisted daily assaults for three weeks. At the same time Edmund’s Gascon troops under the Captal de Buch and other nobles pillaged the town without mercy. A later petition revealed that the Gascons stole wine, oats, corn, hay, bread and other victuals from the burgesses. A citizen named Gaillard Ayquem, at that time being held hostage by the French, complained that his property had been ransacked: four coffers were broken open, six feather pillows and eight sheets removed, two cloaks and many bedcovers and hangings looted, grain taken from his storehouse, while his servant had been stripped of his shirt and held prisoner for three days.

This was no way to win hearts and minds. The approach of a French army under the Comte d’Artois (coat of arms attached) forced Edmund to raise the siege, and the disgruntled citizens promptly opened their gates to the enemy.

Edmund was out of luck, out of money and almost out of time. ‘His face fell’, reports the chronicler, and he was sick in body and spirit.

Published on December 04, 2019 04:38

December 3, 2019

Lacy's war

In April 1296 Edmund of Lancaster and Henry de Lacy began their campaign to reconquer Gascony from the French. They landed at Blaye in the northern part of the duchy, with the intention of capturing those forts which had either fallen or been handed over to the enemy. The twin ducal strongholds of Bourg and Blaye commanded access to the Gironde, a waterway that led into the heart of Gascony. So long as the English held these places, they had a springboard to launch attacks on French-held settlements along the line of the river.

When Lancaster and Lacy arrived, there was a general flocking to the standard. All the free Gascons who had not submitted to the French rallied to them, as did the remains of the first English expeditionary force under John de St John and John of Brittany. There was now only one Anglo-Gascon field army in the duchy. The English commanders chose to have a crack at recapturing Bordeaux, the chief city of Gascony and centre of the wine trade. With over 30,000 inhabitants, Bordeaux was about the same size as London. If it could be swiftly retaken, the French occupation of the duchy would soon unravel.

On Wednesday in Easter Week, the English army landed near Bègles, a suburb of Bordeaux and adjacent to it on the south. The French garrison sallied out to meet them, along with some Bordeaux militia. All the pro-English elements inside the city had been carefully weeded out and sent off to prison at Toulouse and Carcassone, where many died in filthy conditions.

The battle that followed is almost totally forgotten; possibly nobody has yet made a terrible film about it. The French and their allies charged the English men-at-arms, who staged a feigned retreat. When the enemy had pursued them a considerable distance from the city, the English turned about and slaughtered their pursuers, who fled back to the city gates. Some two thousand French were killed. A handful of English knights chased the fugitives into Bordeaux, only to find the gates slammed behind them. Rather than surrender, they stood back-to-back and died to a man.

Edmund, who was now terminally ill, had won a Pyrhhic victory. He set fire to the suburbs of Bordeaux, but lacked siege equipment to force a surrender. It seems the English hoped the citizens would rise up and drive out the French, but were unaware that their sympathizers inside the city had been evacuated. When it became clear the English could not take Bordeaux by storm, they raised the siege and marched away.

When Lancaster and Lacy arrived, there was a general flocking to the standard. All the free Gascons who had not submitted to the French rallied to them, as did the remains of the first English expeditionary force under John de St John and John of Brittany. There was now only one Anglo-Gascon field army in the duchy. The English commanders chose to have a crack at recapturing Bordeaux, the chief city of Gascony and centre of the wine trade. With over 30,000 inhabitants, Bordeaux was about the same size as London. If it could be swiftly retaken, the French occupation of the duchy would soon unravel.

On Wednesday in Easter Week, the English army landed near Bègles, a suburb of Bordeaux and adjacent to it on the south. The French garrison sallied out to meet them, along with some Bordeaux militia. All the pro-English elements inside the city had been carefully weeded out and sent off to prison at Toulouse and Carcassone, where many died in filthy conditions.

The battle that followed is almost totally forgotten; possibly nobody has yet made a terrible film about it. The French and their allies charged the English men-at-arms, who staged a feigned retreat. When the enemy had pursued them a considerable distance from the city, the English turned about and slaughtered their pursuers, who fled back to the city gates. Some two thousand French were killed. A handful of English knights chased the fugitives into Bordeaux, only to find the gates slammed behind them. Rather than surrender, they stood back-to-back and died to a man.

Edmund, who was now terminally ill, had won a Pyrhhic victory. He set fire to the suburbs of Bordeaux, but lacked siege equipment to force a surrender. It seems the English hoped the citizens would rise up and drive out the French, but were unaware that their sympathizers inside the city had been evacuated. When it became clear the English could not take Bordeaux by storm, they raised the siege and marched away.

Published on December 03, 2019 05:05

December 2, 2019

He opened not his mouth.

In July 1295, in a parliament at Stirling, King John Balliol of Scotland was ‘given’ a council of twelve advisors with powers to arrange a marriage between Balliol’s son and Jeanne of Valois, niece to Philip IV of France. This was part of the Franco-Scots alliance against Edward I of England. Poor old John played little part in the talks over his own son’s marriage: according to Rishanger, he “opened not his mouth” as the negotiations went ahead.

Meanwhile Philip and his advisors were busy securing diversions from the north and to make alliances in reply to Edward’s alliance with King Adolf of Germany and the princes of the Rhineland. The French were just as concerned to ally with Norway as Scotland: in return for an annual payment of £50,000 sterling, King Eric of Norway promised to equip a fleet of 100 great ships for four months of each year to attack the English. Meanwhile Balliol undertook - or rather, his council undertook - to invade and harry England if Edward left the country or sent large forces to make war on France. Philip undertook to give aid to Scotland in case of need.

All of this had been triggered by Philip’s seizure of the English territories of Gascony and Ponthieu in 1294, via the approved methods of underhand scheming, bare-faced deceit and brute force. Edward’s response in England was to appoint the Bishop of Durham and Earl Warenne as custodians of the north, and Robert de Bruce as castellan of Carlisle. Balliol was ordered to surrender the castles and boroughs of Berwick, Roxburgh and Jedburgh, and on 16 October writs were issued for the seizure of all English lands held by Balliol and his tenants who dwelt in Scotland.

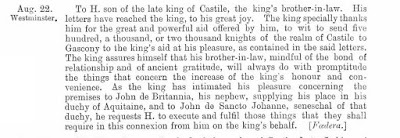

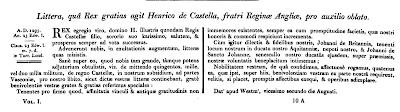

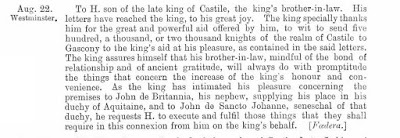

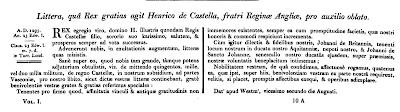

The lights were going out all over Western Europe. In late August Edward had sent reinforcements to defend what remained of English-held Gascony. He received a boost from Henry the Senator, regent of Castile and the brother of Edward’s late queen, Eleanor; Henry offered to send five hundred, a thousand or two thousand knights of Castile to storm across the Pyrenees and attack the French in Gascony.

Therefore, if a prince blew his nose in Berlin, it was heard as far away as Glasgow.

Meanwhile Philip and his advisors were busy securing diversions from the north and to make alliances in reply to Edward’s alliance with King Adolf of Germany and the princes of the Rhineland. The French were just as concerned to ally with Norway as Scotland: in return for an annual payment of £50,000 sterling, King Eric of Norway promised to equip a fleet of 100 great ships for four months of each year to attack the English. Meanwhile Balliol undertook - or rather, his council undertook - to invade and harry England if Edward left the country or sent large forces to make war on France. Philip undertook to give aid to Scotland in case of need.

All of this had been triggered by Philip’s seizure of the English territories of Gascony and Ponthieu in 1294, via the approved methods of underhand scheming, bare-faced deceit and brute force. Edward’s response in England was to appoint the Bishop of Durham and Earl Warenne as custodians of the north, and Robert de Bruce as castellan of Carlisle. Balliol was ordered to surrender the castles and boroughs of Berwick, Roxburgh and Jedburgh, and on 16 October writs were issued for the seizure of all English lands held by Balliol and his tenants who dwelt in Scotland.

The lights were going out all over Western Europe. In late August Edward had sent reinforcements to defend what remained of English-held Gascony. He received a boost from Henry the Senator, regent of Castile and the brother of Edward’s late queen, Eleanor; Henry offered to send five hundred, a thousand or two thousand knights of Castile to storm across the Pyrenees and attack the French in Gascony.

Therefore, if a prince blew his nose in Berlin, it was heard as far away as Glasgow.

Published on December 02, 2019 06:34

December 1, 2019

Broken promises

In the summer of 1241, a year after the death of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, the Welsh lords of the middle March were at war with Ralf Mortimer of Wigmore. They were assisted by the seneschals of Dafydd ap Llywelyn, lord of Gwynedd and self-proclaimed Prince of Wales.

Mortimer sought to protect himself by sowing dissension in Gwynedd. On 12 August he stood surety for a fine promised to Henry III by Senana, wife of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, for which the king undertook to free Gruffydd and his son Owain from Dafydd’s prison. Gruffydd and Dafydd were half-brothers and the royal policy was to dangle Gruffydd as a potential threat to Dafydd’s hegemony in North Wales.

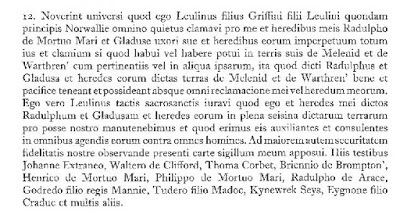

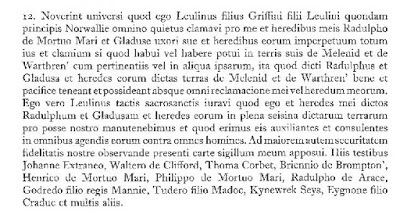

At about the same time Mortimer came to an agreement with his wife’s nephew, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Two copies of a deed exist, in which Llywelyn quit all his rights in the lands of Gwrtherynion and Maelienydd to Ralf Mortimer and his heirs. One of the copies of the deed contains a saving clause in which Llywelyn swore to support the Mortimers against all men, saving the King of England. In the deed Llywelyn styles himself ‘filius Griffith filii Leulini quondam principis Norwallie’. This reflects English chancery practice with respect to his uncle Prince Dafydd, who was designated ‘filius Lewelini quondam principies Norwallie’. In King Henry’s agreement of 12 August with Senana, he stipulated that two of her sons, Dafydd and Rhodri, should handed over as hostages. Her husband Gruffydd and the eldest son, Owain Goch, were also taken into royal custody. Llywelyn was exempt.

Among the witnesses to the Mortimer deed is Einion ap Caradog, who had recently fled Prince Dafydd’s court after informing Dafydd to his face that he was “too weak to be a prince”. Another member of Llywelyn’s entourage at this time was Richard, Bishop of Bangor, who abandoned Dafydd and publicly declared his fealty to Henry III.

At this time, therefore, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd appears to have been a royal partisan against his uncle Dafydd, and in alliance with the Mortimers. His attitude changed when his father, Gruffydd, died attempting to escape from the Tower in 1244. After this Llywelyn became a supporter of Prince Dafydd, possibly in the hope that Dafydd would make him his successor. In the event he and his brother Owain seized power after Dafydd’s death in 1246.

Even so, Llywelyn could not escape his oath to the Mortimers. In 1257, sixteen years after he quit all his rights in Maelienydd and Gwrtherynion, Llywellyn broke the agreement and invaded those lands. This possibly sowed the seeds of his eventual destruction at Mortimer hands in 1282.

Mortimer sought to protect himself by sowing dissension in Gwynedd. On 12 August he stood surety for a fine promised to Henry III by Senana, wife of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, for which the king undertook to free Gruffydd and his son Owain from Dafydd’s prison. Gruffydd and Dafydd were half-brothers and the royal policy was to dangle Gruffydd as a potential threat to Dafydd’s hegemony in North Wales.

At about the same time Mortimer came to an agreement with his wife’s nephew, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Two copies of a deed exist, in which Llywelyn quit all his rights in the lands of Gwrtherynion and Maelienydd to Ralf Mortimer and his heirs. One of the copies of the deed contains a saving clause in which Llywelyn swore to support the Mortimers against all men, saving the King of England. In the deed Llywelyn styles himself ‘filius Griffith filii Leulini quondam principis Norwallie’. This reflects English chancery practice with respect to his uncle Prince Dafydd, who was designated ‘filius Lewelini quondam principies Norwallie’. In King Henry’s agreement of 12 August with Senana, he stipulated that two of her sons, Dafydd and Rhodri, should handed over as hostages. Her husband Gruffydd and the eldest son, Owain Goch, were also taken into royal custody. Llywelyn was exempt.

Among the witnesses to the Mortimer deed is Einion ap Caradog, who had recently fled Prince Dafydd’s court after informing Dafydd to his face that he was “too weak to be a prince”. Another member of Llywelyn’s entourage at this time was Richard, Bishop of Bangor, who abandoned Dafydd and publicly declared his fealty to Henry III.

At this time, therefore, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd appears to have been a royal partisan against his uncle Dafydd, and in alliance with the Mortimers. His attitude changed when his father, Gruffydd, died attempting to escape from the Tower in 1244. After this Llywelyn became a supporter of Prince Dafydd, possibly in the hope that Dafydd would make him his successor. In the event he and his brother Owain seized power after Dafydd’s death in 1246.

Even so, Llywelyn could not escape his oath to the Mortimers. In 1257, sixteen years after he quit all his rights in Maelienydd and Gwrtherynion, Llywellyn broke the agreement and invaded those lands. This possibly sowed the seeds of his eventual destruction at Mortimer hands in 1282.

Published on December 01, 2019 04:22