David Pilling's Blog, page 37

January 3, 2020

Independence come early

In the summer of 1244, while Prince Dafydd raised war in Wales, Henry III marched north to confront Alexander II of Scotland. Henry had already given orders to mobilise at Newcastle in preparation for a massive invasion, including the construction of siege engines and 30,000 crossbow bolts. If the invasion had gone ahead, the Wars of Independence might have come early with Longshanks (born in 1239) barely astride his first pony.

The cause of the trouble was apparently a statement by Alexander, who declared he held nothing of his realm from the King of England. There was also a hefty dollop of intrigue, with a band of Scottish exiles at Henry’s court accusing the King of Scots of plotting an alliance with France. As with Henry’s Welsh campaigns in this decade, the situation eerily foreshadowed the later conflicts under Edward I.

The details are confusing. Henry’s specific allegation against the Scots was that Walter Comyn and other Scottish nobles had fortified two castles in Galway and Lothian, to the prejudice of the king of England, and contrary to the charters of their ancestors. Comyn had also entered into a secret alliance with the French, and received outlaws and fugitives from England. He did this, Henry alleged, to draw men away from the king’s allegiance.

Alexander moved first and invaded England. According to Matthew Paris, he pitched camp near Newcastle with an army of a thousand mounted knights and a hundred thousand footsoldiers; an impossible figure, though Alexander had obviously come fully loaded. Henry advanced to confront him with five thousand knights, which again sounds impossibly large: Edward I could only raise two thousand knights for the Falkirk campaign in 1298, when he raised the largest army seen in the British Isles since 1066.

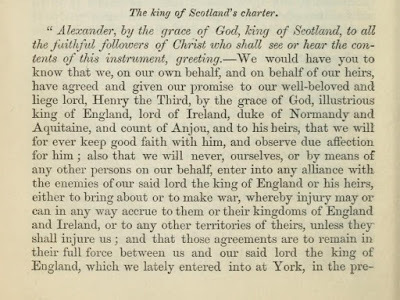

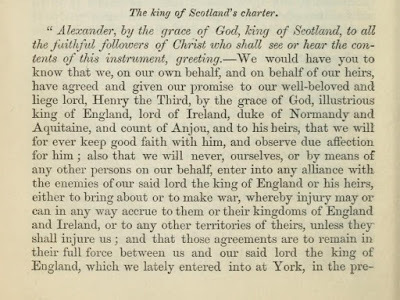

Battle was avoided thanks to the efforts of Walter Gray and Richard of Cornwall, Henry’s brother, who brokered peace between the two armies. Alexander promised not to enter into any foreign alliance against Henry unless he was ‘unjustly oppressed’ by him.

In the charter or peace agreement, Alexander referred to Henry as his liege lord. Possibly that only applied to Alexander’s lands in England, though the text doesn’t say as much. The pope was then asked to confirm the agreement, and to restrain and censure Alexander and his heirs if they ever deviated from it.

The cause of the trouble was apparently a statement by Alexander, who declared he held nothing of his realm from the King of England. There was also a hefty dollop of intrigue, with a band of Scottish exiles at Henry’s court accusing the King of Scots of plotting an alliance with France. As with Henry’s Welsh campaigns in this decade, the situation eerily foreshadowed the later conflicts under Edward I.

The details are confusing. Henry’s specific allegation against the Scots was that Walter Comyn and other Scottish nobles had fortified two castles in Galway and Lothian, to the prejudice of the king of England, and contrary to the charters of their ancestors. Comyn had also entered into a secret alliance with the French, and received outlaws and fugitives from England. He did this, Henry alleged, to draw men away from the king’s allegiance.

Alexander moved first and invaded England. According to Matthew Paris, he pitched camp near Newcastle with an army of a thousand mounted knights and a hundred thousand footsoldiers; an impossible figure, though Alexander had obviously come fully loaded. Henry advanced to confront him with five thousand knights, which again sounds impossibly large: Edward I could only raise two thousand knights for the Falkirk campaign in 1298, when he raised the largest army seen in the British Isles since 1066.

Battle was avoided thanks to the efforts of Walter Gray and Richard of Cornwall, Henry’s brother, who brokered peace between the two armies. Alexander promised not to enter into any foreign alliance against Henry unless he was ‘unjustly oppressed’ by him.

In the charter or peace agreement, Alexander referred to Henry as his liege lord. Possibly that only applied to Alexander’s lands in England, though the text doesn’t say as much. The pope was then asked to confirm the agreement, and to restrain and censure Alexander and his heirs if they ever deviated from it.

Published on January 03, 2020 00:49

January 2, 2020

Vassal states

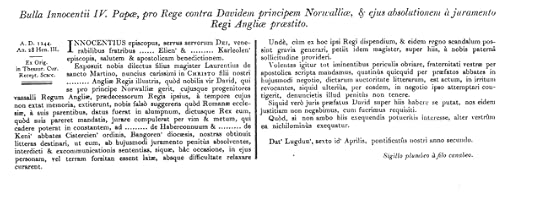

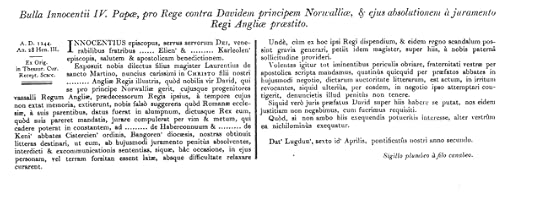

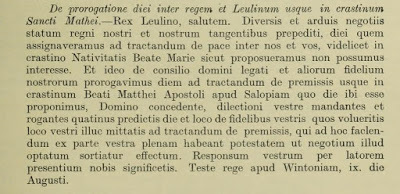

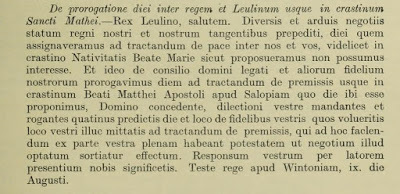

Attached is a fairly important document relating to the history of medieval Wales. It is a response from Pope Innocent IV to Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn, dated 8 April 1245, to the latter’s plea that Wales should be held from Rome as a papal fiefdom. This would sever feudal ties to the English crown, and make Wales a vassal state of the papacy.

Most of this story comes from Matthew Paris, who cannot be trusted. Fortunately this response from the pope survives, which confirms the essence of it. The letter of the papal court references Dafydd’s argument that his parents had given him to the church of Rome as a child - an alumnus or ward - and on this account he sought absolution from the pledges forced upon him by Henry III via the treaties of Rhuddlan and London.

Most of this story comes from Matthew Paris, who cannot be trusted. Fortunately this response from the pope survives, which confirms the essence of it. The letter of the papal court references Dafydd’s argument that his parents had given him to the church of Rome as a child - an alumnus or ward - and on this account he sought absolution from the pledges forced upon him by Henry III via the treaties of Rhuddlan and London.

Dafydd claimed that these pledges had been extracted from him by ‘force and fear’. If so this rendered them null and void, for medieval jurisprudence discounted any oath exacted under duress. The document of the treaty of London states that Dafydd had surrendered Gwynedd to King Henry of his own free will - his ‘liberality’ - which is a classic example of medieval legalism. No prince in command of his faculties ever surrendered his patrimony unless he was forced: in crude terms, we may imagine Dafydd putting his seal to the London treaty while a man stood behind him with a big stick.

Coincidentally - or not - Dafydd’s request was the exact same deal later offered by Edward I to Pope Boniface VIII over the duchy of Gascony. If Boniface agreed to take Gascony as a papal fief, that would have severed feudal ties with France and meant future kings of England did not have to swear homage and fealty to the Capetian kings in Paris. It would also remove any legal pretext for French invasions of Gascony. Equally, Dafydd sought to cut Wales loose from the English crown and remove any cause for English military aggression against his country. Whether or not Edward was influenced by Prince Dafydd, a Welsh prince who died when he was just seven years old, is unknowable. That said, the strategy in both cases is the same. Neither ploy worked.

Within a year of Dafydd’s request, Pope Innocent responded that every Christian knew that the prince of Wales was no more than a minor vassal of the king of England. Innocent’s view may have been influenced by a hefty English bribe. As Lloyd put it, the response of His Divine Brilliance revealed “not obscurely the influence of the weightier purse”.

Most of this story comes from Matthew Paris, who cannot be trusted. Fortunately this response from the pope survives, which confirms the essence of it. The letter of the papal court references Dafydd’s argument that his parents had given him to the church of Rome as a child - an alumnus or ward - and on this account he sought absolution from the pledges forced upon him by Henry III via the treaties of Rhuddlan and London.

Most of this story comes from Matthew Paris, who cannot be trusted. Fortunately this response from the pope survives, which confirms the essence of it. The letter of the papal court references Dafydd’s argument that his parents had given him to the church of Rome as a child - an alumnus or ward - and on this account he sought absolution from the pledges forced upon him by Henry III via the treaties of Rhuddlan and London.

Dafydd claimed that these pledges had been extracted from him by ‘force and fear’. If so this rendered them null and void, for medieval jurisprudence discounted any oath exacted under duress. The document of the treaty of London states that Dafydd had surrendered Gwynedd to King Henry of his own free will - his ‘liberality’ - which is a classic example of medieval legalism. No prince in command of his faculties ever surrendered his patrimony unless he was forced: in crude terms, we may imagine Dafydd putting his seal to the London treaty while a man stood behind him with a big stick.

Coincidentally - or not - Dafydd’s request was the exact same deal later offered by Edward I to Pope Boniface VIII over the duchy of Gascony. If Boniface agreed to take Gascony as a papal fief, that would have severed feudal ties with France and meant future kings of England did not have to swear homage and fealty to the Capetian kings in Paris. It would also remove any legal pretext for French invasions of Gascony. Equally, Dafydd sought to cut Wales loose from the English crown and remove any cause for English military aggression against his country. Whether or not Edward was influenced by Prince Dafydd, a Welsh prince who died when he was just seven years old, is unknowable. That said, the strategy in both cases is the same. Neither ploy worked.

Within a year of Dafydd’s request, Pope Innocent responded that every Christian knew that the prince of Wales was no more than a minor vassal of the king of England. Innocent’s view may have been influenced by a hefty English bribe. As Lloyd put it, the response of His Divine Brilliance revealed “not obscurely the influence of the weightier purse”.

Published on January 02, 2020 04:06

December 31, 2019

Of his own free will

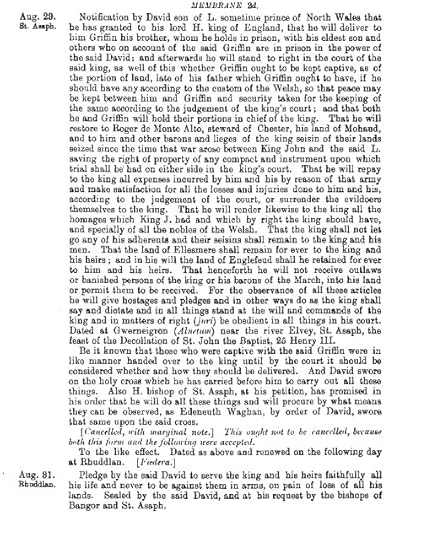

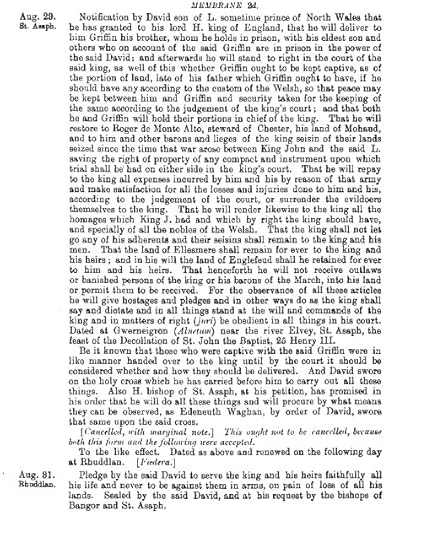

On 29 August 1241, at Gwern Eigron on the river Elwy near St Asaph, and on the following day in the royal tent at Rhuddlan, Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn came to terms with Henry III.

The Treaty of Gwerneigron

The Treaty of Gwerneigron

Dafydd undertook to release his brother, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, and to submit to the decision of the king’s court on the share of his father’s lands which Gruffydd ought to have. The king would decide if the case should be settled via Welsh custom or the rule of ‘feudal’ law. Dafydd also agreed that his lands in Gwynedd should be held in chief of the crown, and he surrendered Mold castle and all lands of Henry’s barons and vassals occupied by Llywelyn the Great since the days of King John. He promised to pay war damages and restore the homages which Welshmen had once owed to John, including Welsh nobles.

At London, in October, Dafydd was obliged to go further. He had no direct heir, so Henry induced him to accept feudal law, whereby his land would escheat to the crown upon death. The document states that Dafydd did this of his own free will - "donacione inter vivos" - though we may entertain reasonable suspicions. He also surrendered the manor of Ellesmere, the Welsh cantref of Tegeingl, and the castle and lands of Degannwy.

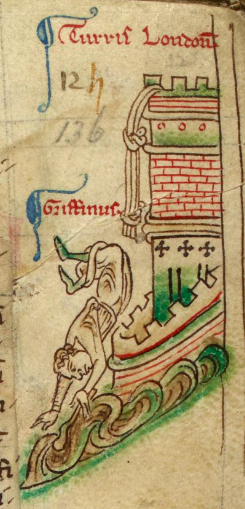

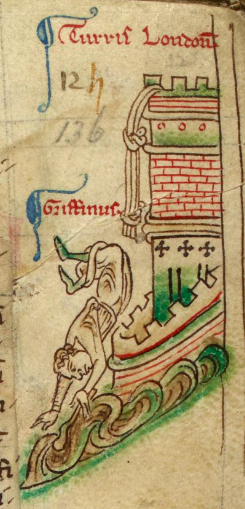

Gruffydd, that unhappy man, had been well and truly set aside. Henry kept him in the Tower of London, to use as potential leverage against his brother. His active career was over.

He still had a theoretical purpose. Henry, an underrated politician, had declared his intention to partition Gwynedd between the brothers. In reality he wished to establish a principle: the king sought to reverse the unity sought by princes of Gwynedd ever since the days of Gruffydd ap Cynan, and he used the Welsh law of partible inheritance to do it. This meant he could use the ‘custom of Wales’ against any Welsh prince, as the princes themselves were all too aware. In a bid to keep their territories intact, they rushed to make peace with the king.

For the moment, Dafydd was left politically isolated. He would remain so as long as Gruffydd was alive.

The Treaty of Gwerneigron

The Treaty of GwerneigronDafydd undertook to release his brother, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, and to submit to the decision of the king’s court on the share of his father’s lands which Gruffydd ought to have. The king would decide if the case should be settled via Welsh custom or the rule of ‘feudal’ law. Dafydd also agreed that his lands in Gwynedd should be held in chief of the crown, and he surrendered Mold castle and all lands of Henry’s barons and vassals occupied by Llywelyn the Great since the days of King John. He promised to pay war damages and restore the homages which Welshmen had once owed to John, including Welsh nobles.

At London, in October, Dafydd was obliged to go further. He had no direct heir, so Henry induced him to accept feudal law, whereby his land would escheat to the crown upon death. The document states that Dafydd did this of his own free will - "donacione inter vivos" - though we may entertain reasonable suspicions. He also surrendered the manor of Ellesmere, the Welsh cantref of Tegeingl, and the castle and lands of Degannwy.

Gruffydd, that unhappy man, had been well and truly set aside. Henry kept him in the Tower of London, to use as potential leverage against his brother. His active career was over.

He still had a theoretical purpose. Henry, an underrated politician, had declared his intention to partition Gwynedd between the brothers. In reality he wished to establish a principle: the king sought to reverse the unity sought by princes of Gwynedd ever since the days of Gruffydd ap Cynan, and he used the Welsh law of partible inheritance to do it. This meant he could use the ‘custom of Wales’ against any Welsh prince, as the princes themselves were all too aware. In a bid to keep their territories intact, they rushed to make peace with the king.

For the moment, Dafydd was left politically isolated. He would remain so as long as Gruffydd was alive.

Published on December 31, 2019 04:44

December 30, 2019

On the banks of the Elwy

In the autumn of 1240, after swearing homage to Henry III, Prince Dafydd returned to Gwynedd and arrested his brother Gruffydd for a second time. He did this by inviting Gruffydd to a council and then breaking the safe-conduct:

“Dafydd, simultaneously forgetful of their fraternity and their honesty, ordered him to be seized and, even though the leaders were unwilling and cried out in protest, he ordered him to be consigned to the safe keeping of jail.”

- Matthew Paris

Rhuddlan Castle

Rhuddlan Castle

Along with Dafydd’s contumacy over the rights to Mold castle, King Henry now had all the reasons he needed to invade North Wales. In August he advanced from Chester to Shrewsbury, accompanied by Ralph Mortimer, Gruffudd ap Madog and his brothers Hywel and Maredudd, Maredudd ap Robert of Cydewain, Walter Clifford, Roger of Mold and Maelgwn Fychan.

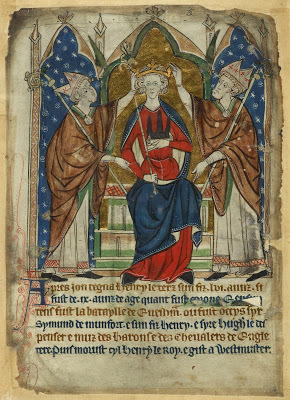

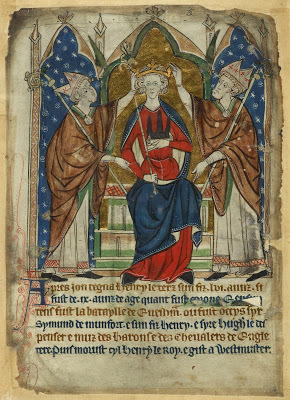

Henry III

Henry III

At Shrewsbury, on 12 August, Henry was met by Gruffydd ap Llywelyn’s wife, Senana. Earlier, at Easter, she had gone to Henry’s court to persuade the king to secure her husband’s release from Dafydd’s prison. Now she tried again, and this time offered cash. In exchange for 600 marks (£400), she asked Henry to deliver Gruffudd and her son Owain Goch from captivity.

Henry took the money, but his agreement was carefully worded. He offered to deliver Gruffydd and Owain from prison on condition that Gruffudd would ‘abide by the judgement of the king’s court, whether lawfully he ought to be detained in prison’. Unless Senana was naive, she must have appreciated what this meant: Gruffydd and Owain would be taken from Dafydd’s prison into royal custody. So long as Henry could use him as leverage against Dafydd, Gruffydd would never be released. Perhaps Senana realised this, but had better hopes of obtaining the release of her son. In any event, it was better than Gruffydd should abide with his step-uncle than his half-brother, who would in all likelihood have him killed.

The king moved on. Like his son over thirty years later, he overran the northeast coast and pitched his headquarters at Rhuddlan. Before the end of August, on the banks of the Elwy in the cantref of Rhos, Prince Dafydd came to the king and threw down his arms.

“Dafydd, simultaneously forgetful of their fraternity and their honesty, ordered him to be seized and, even though the leaders were unwilling and cried out in protest, he ordered him to be consigned to the safe keeping of jail.”

- Matthew Paris

Rhuddlan Castle

Rhuddlan CastleAlong with Dafydd’s contumacy over the rights to Mold castle, King Henry now had all the reasons he needed to invade North Wales. In August he advanced from Chester to Shrewsbury, accompanied by Ralph Mortimer, Gruffudd ap Madog and his brothers Hywel and Maredudd, Maredudd ap Robert of Cydewain, Walter Clifford, Roger of Mold and Maelgwn Fychan.

Henry III

Henry IIIAt Shrewsbury, on 12 August, Henry was met by Gruffydd ap Llywelyn’s wife, Senana. Earlier, at Easter, she had gone to Henry’s court to persuade the king to secure her husband’s release from Dafydd’s prison. Now she tried again, and this time offered cash. In exchange for 600 marks (£400), she asked Henry to deliver Gruffudd and her son Owain Goch from captivity.

Henry took the money, but his agreement was carefully worded. He offered to deliver Gruffydd and Owain from prison on condition that Gruffudd would ‘abide by the judgement of the king’s court, whether lawfully he ought to be detained in prison’. Unless Senana was naive, she must have appreciated what this meant: Gruffydd and Owain would be taken from Dafydd’s prison into royal custody. So long as Henry could use him as leverage against Dafydd, Gruffydd would never be released. Perhaps Senana realised this, but had better hopes of obtaining the release of her son. In any event, it was better than Gruffydd should abide with his step-uncle than his half-brother, who would in all likelihood have him killed.

The king moved on. Like his son over thirty years later, he overran the northeast coast and pitched his headquarters at Rhuddlan. Before the end of August, on the banks of the Elwy in the cantref of Rhos, Prince Dafydd came to the king and threw down his arms.

Published on December 30, 2019 07:51

Deadly war

In 1240 Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn swore homage and fealty to Henry III for his right to North Wales. This should have removed any source of conflict, but then a row blew up over the border fortress of Mold, some five miles to the west of the Dee.

The remains of Mold CastleVia the peace of Gloucester, Dafydd’s right to the castle was reserved. In October 1240 the matter was submitted for arbitration to a team of English and Welsh judges. The English side included the papal legate, while the Welsh side included Ednyfed Fychan and the bishop of St Asaph, two of the most powerful elder statesmen of Wales.

The remains of Mold CastleVia the peace of Gloucester, Dafydd’s right to the castle was reserved. In October 1240 the matter was submitted for arbitration to a team of English and Welsh judges. The English side included the papal legate, while the Welsh side included Ednyfed Fychan and the bishop of St Asaph, two of the most powerful elder statesmen of Wales.

Dafydd refused two summons to appear before the commissioners. This was an eerie foreshadow of later events, when his nephew Llywelyn ap Gruffudd refused to appear before Edward I. In Dafydd’s case, the context turned on a subtle point of feudal law: Henry III had originally agreed to submit the issue of Mold to arbitration. In March 1241, contrary to the terms of peace, he treated the matter in dispute as though it fell within his jurisdiction. In plain language, it was no longer a dispute between equals, but between a lord and his vassal.

This struck at the heart of the problematic relationship between the English crown and the princes of North Wales: were Llywelyn the Great and his heirs heads of state in their own right, albeit owing homage to the king, or were they merely tenants-in-chief?

Dafydd’s mistake, later repeated by his nephew, was to refuse to appear to argue his case. Judgement went against him by default, and when he failed to appear a second time Henry took action. The king gained the approval of the other Welsh princes by promising to satisfy the claims of Dafydd’s prisoner, his brother Gruffydd.

There was certainly more sympathy for Gruffydd than Dafydd in Wales. Gruffydd ap Madog, lord of Bromfield, expressed the prevailing view when he promised the king everlasting support:

“if he would invade Wales, and make deadly war against the false Dafydd and his many wrongs.”

Dafydd also incurred the censure of the church. In July 1241, after his attempt to persuade the prince to release Gruffydd failed, Bishop Richard of Bangor excommunicated Dafydd and went to Henry demanding military action.

The remains of Mold CastleVia the peace of Gloucester, Dafydd’s right to the castle was reserved. In October 1240 the matter was submitted for arbitration to a team of English and Welsh judges. The English side included the papal legate, while the Welsh side included Ednyfed Fychan and the bishop of St Asaph, two of the most powerful elder statesmen of Wales.

The remains of Mold CastleVia the peace of Gloucester, Dafydd’s right to the castle was reserved. In October 1240 the matter was submitted for arbitration to a team of English and Welsh judges. The English side included the papal legate, while the Welsh side included Ednyfed Fychan and the bishop of St Asaph, two of the most powerful elder statesmen of Wales.Dafydd refused two summons to appear before the commissioners. This was an eerie foreshadow of later events, when his nephew Llywelyn ap Gruffudd refused to appear before Edward I. In Dafydd’s case, the context turned on a subtle point of feudal law: Henry III had originally agreed to submit the issue of Mold to arbitration. In March 1241, contrary to the terms of peace, he treated the matter in dispute as though it fell within his jurisdiction. In plain language, it was no longer a dispute between equals, but between a lord and his vassal.

This struck at the heart of the problematic relationship between the English crown and the princes of North Wales: were Llywelyn the Great and his heirs heads of state in their own right, albeit owing homage to the king, or were they merely tenants-in-chief?

Dafydd’s mistake, later repeated by his nephew, was to refuse to appear to argue his case. Judgement went against him by default, and when he failed to appear a second time Henry took action. The king gained the approval of the other Welsh princes by promising to satisfy the claims of Dafydd’s prisoner, his brother Gruffydd.

There was certainly more sympathy for Gruffydd than Dafydd in Wales. Gruffydd ap Madog, lord of Bromfield, expressed the prevailing view when he promised the king everlasting support:

“if he would invade Wales, and make deadly war against the false Dafydd and his many wrongs.”

Dafydd also incurred the censure of the church. In July 1241, after his attempt to persuade the prince to release Gruffydd failed, Bishop Richard of Bangor excommunicated Dafydd and went to Henry demanding military action.

Published on December 30, 2019 04:06

December 29, 2019

Homage and fealty

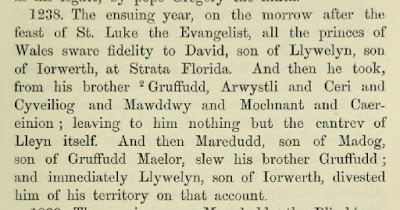

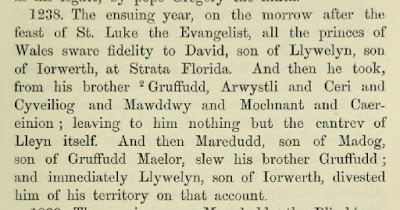

In 1238, at Strata Florida, the princes of Wales swore fealty or ‘fidelity’ to Dafydd, second son and heir to Llywelyn the Great. Llywellyn had summoned them all in an effort to secure Dafydd’s succession before his father died.

Strata Florida

Strata Florida

The nature of the oath is important, and reveals the mindset of the princes. There were two forms of oath-taking: homage and fealty. Homage was a binding oath between a lord and his vassal. Fealty was less binding, and could be taken to more than one lord.

Llywelyn wanted the princes of Wales to swear homage and fealty to his son. They did not. This failure to secure a binding agreement made it virtually inevitable that Llywelyn’s supremacy would start to fall apart after his death.

The arms of Powys Fadog

The arms of Powys Fadog

Why did the princes refuse to swear homage? Every individual had his reasons. The princes had their own interests to safeguard, and the records of the chancery show their anxiety to swear homage to Henry III in the summer of 1240. This was after they had sworn the lesser oath to Prince Dafydd. Among the first to swear homage to the king was Gruffudd ap Madog of Powys Fadog, who hated Dafydd anyway and had waged war on him in the last years of Llywelyn’s reign. He also wished to see off the threat of his brothers and preserve a united Powys Fadog, which could only be done with royal support.

In the south, Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg had only inherited a portion of Ystrad Tywi from his father. The death of Prince Llywelyn gave him the opportunity to secure a broader dominion, which again could only be achieved with the king’s consent and support.

Henry III

Henry III

Dafydd, for his part, was keen to swear homage to Henry III as quickly as possible, so he could return to Gwynedd to deal with his brother, Gruffudd ap Llywelyn. He came before the king at Gloucester, did homage for his right to North Wales, was knighted, and “wore the talaith or coronet which was the special symbol of his rank”. Dafydd also agreed with Henry to submit to arbitration the rights to land claimed by the lords of Powys Wenwynwyn, ‘as barons of the lord king’. Not for the last time, the House of Mathrafal chose to identify as English-style barons instead of Welsh princes in order to gain a legal advantage.

By the terms of the peace at Gloucester, Dafydd surrendered ‘all the homages of the barons of Wales’ to the king and his heirs without question. This concession, freely given by the prince, would have dire consequences for the future.

Strata Florida

Strata FloridaThe nature of the oath is important, and reveals the mindset of the princes. There were two forms of oath-taking: homage and fealty. Homage was a binding oath between a lord and his vassal. Fealty was less binding, and could be taken to more than one lord.

Llywelyn wanted the princes of Wales to swear homage and fealty to his son. They did not. This failure to secure a binding agreement made it virtually inevitable that Llywelyn’s supremacy would start to fall apart after his death.

The arms of Powys Fadog

The arms of Powys FadogWhy did the princes refuse to swear homage? Every individual had his reasons. The princes had their own interests to safeguard, and the records of the chancery show their anxiety to swear homage to Henry III in the summer of 1240. This was after they had sworn the lesser oath to Prince Dafydd. Among the first to swear homage to the king was Gruffudd ap Madog of Powys Fadog, who hated Dafydd anyway and had waged war on him in the last years of Llywelyn’s reign. He also wished to see off the threat of his brothers and preserve a united Powys Fadog, which could only be done with royal support.

In the south, Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg had only inherited a portion of Ystrad Tywi from his father. The death of Prince Llywelyn gave him the opportunity to secure a broader dominion, which again could only be achieved with the king’s consent and support.

Henry III

Henry IIIDafydd, for his part, was keen to swear homage to Henry III as quickly as possible, so he could return to Gwynedd to deal with his brother, Gruffudd ap Llywelyn. He came before the king at Gloucester, did homage for his right to North Wales, was knighted, and “wore the talaith or coronet which was the special symbol of his rank”. Dafydd also agreed with Henry to submit to arbitration the rights to land claimed by the lords of Powys Wenwynwyn, ‘as barons of the lord king’. Not for the last time, the House of Mathrafal chose to identify as English-style barons instead of Welsh princes in order to gain a legal advantage.

By the terms of the peace at Gloucester, Dafydd surrendered ‘all the homages of the barons of Wales’ to the king and his heirs without question. This concession, freely given by the prince, would have dire consequences for the future.

Published on December 29, 2019 04:02

December 28, 2019

True lord of the land

The late summer of 1238 witnessed all kinds of maneuvering and power play in Wales. Unfortunately not all the documents have survived, but some reasonable assumptions can be made. On 9 August Henry III wrote to Llywelyn the Great, informing the prince that he would be at Shrewsbury on 22 September to discuss royal power in Wales. The language is blunt: this was all about power - potestatem - and nobody was pretending otherwise.

CricciethWithin the month, on 19 October, all the princes of Wales swore homage to Dafydd son of Prince Llywelyn at Strata Florida. Earlier in the year Henry had protested that this was an abuse of his majesty, but this second oath-taking provoked no hostile response from the king. Many of the rolls are lost for this period, but it appears the homage must have been taken with Henry’s consent. This in turn implies that Henry and Llywelyn had come to a mutually amicable arrangement.

CricciethWithin the month, on 19 October, all the princes of Wales swore homage to Dafydd son of Prince Llywelyn at Strata Florida. Earlier in the year Henry had protested that this was an abuse of his majesty, but this second oath-taking provoked no hostile response from the king. Many of the rolls are lost for this period, but it appears the homage must have been taken with Henry’s consent. This in turn implies that Henry and Llywelyn had come to a mutually amicable arrangement.

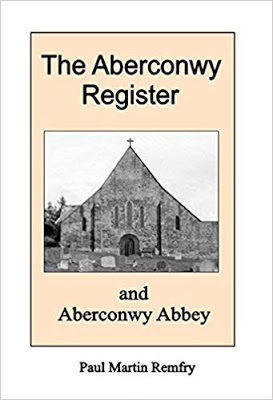

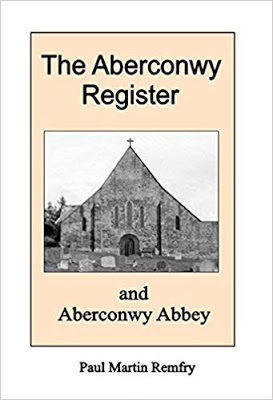

The disabled Llywelyn had done all he could. Two years later, on 11 April 1240, he was laid to rest at Aberconwy after taking the habit of a monk. Soon after his death, Einion Wan composed an elegy for Llywelyn (translated by Sir John Lloyd):

“True lord of the land - how strange that today

He rules not o’er Gwynedd;

Lord of nought but the piled up stones of his tomb,

Of the seven-foot grave in which he lies.”

Prince Dafydd, Llywelyn’s heir, had already taken steps to deal with his elder brother Gruffydd. The Bruts record that a few months before their father died:

“Dafydd ap Llywelyn seized Gruffydd, his brother, breaking faith with him and imprisoned him and his son at Criccieth.”

Once again Gruffydd was the fall guy (no pun intended).

CricciethWithin the month, on 19 October, all the princes of Wales swore homage to Dafydd son of Prince Llywelyn at Strata Florida. Earlier in the year Henry had protested that this was an abuse of his majesty, but this second oath-taking provoked no hostile response from the king. Many of the rolls are lost for this period, but it appears the homage must have been taken with Henry’s consent. This in turn implies that Henry and Llywelyn had come to a mutually amicable arrangement.

CricciethWithin the month, on 19 October, all the princes of Wales swore homage to Dafydd son of Prince Llywelyn at Strata Florida. Earlier in the year Henry had protested that this was an abuse of his majesty, but this second oath-taking provoked no hostile response from the king. Many of the rolls are lost for this period, but it appears the homage must have been taken with Henry’s consent. This in turn implies that Henry and Llywelyn had come to a mutually amicable arrangement.

The disabled Llywelyn had done all he could. Two years later, on 11 April 1240, he was laid to rest at Aberconwy after taking the habit of a monk. Soon after his death, Einion Wan composed an elegy for Llywelyn (translated by Sir John Lloyd):

“True lord of the land - how strange that today

He rules not o’er Gwynedd;

Lord of nought but the piled up stones of his tomb,

Of the seven-foot grave in which he lies.”

Prince Dafydd, Llywelyn’s heir, had already taken steps to deal with his elder brother Gruffydd. The Bruts record that a few months before their father died:

“Dafydd ap Llywelyn seized Gruffydd, his brother, breaking faith with him and imprisoned him and his son at Criccieth.”

Once again Gruffydd was the fall guy (no pun intended).

Published on December 28, 2019 07:37

Homage and dissidence

On 16 June 1237 Henry III wrote to Llywelyn the Great, confirming a truce to last until 25 July 1238. The king also expressed his thanks that Llywelyn thought fit to send his second son, Dafydd, to continue peace talks at Worcester. This meeting was postponed and in the end never happened, possibly due to the refusal of the men of Powys Fadog to agree to any deal proposed by Llywelyn and Dafydd.

The Powysian dissidents were led by their lord, Gruffydd ap Madog, and Llywelyn’s eldest son Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. Together the two Gruffydds, probably supported by other Welsh lords and Marchers, formed an opposition party to the disabled Llywelyn and his son Dafydd. To add to Llywelyn’s woes, 1237 also witnessed the death of his wife, Princess Joan Plantagenet, and his son-in-law Earl John of Chester.

It appears King Henry trusted no-one. On 4 July he issued an order for the archbishop of Canterbury to escort Dafydd to him at Westminster; the very next day it was agreed that Dafydd would prolong the truce with ‘our faithful Prince Llywelyn and his adherents’, described as the king’s ‘open enemies’.

In early 1238 Dafydd launched a campaign against his elder brother. Over the next few months he took from Gruffydd the lands of Arwystli, Ceri, Cyfeiliog, Mochnant, Caereinon and Mawddy. All of Gruffydd’s territorial gains over the past three years were reversed, leaving him with just Llyn.

With Dafydd in the ascendant, the ageing Llywelyn permitted his second son to take the homage of some of the magnates of Wales. When Henry heard of this, he wrote to Morgan of Caerleon, Rhys ap Gruffudd, Rhys Mechyll, Hywel ap Maredudd, Maredudd ap Rhys, Cynan ap Hywel, Maelgwn ap Maelgwn, Gruffydd ab Owain, Richard ap Hywel, Rhys ap Trahaearn, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (the future prince of Wales), Maredudd ap Maelgwn, Owain ap Hywel and his brother, Owain ap Maredudd and all the tenants of honour of Brecon and Buellt and all the tenants of Richard Clare and all the tenants of the English earls and barons in Wales. This mighty assembly was warned not to pay homage to Dafydd, since:

"the aforesaid magnates hold their lands from us and they owe homage to us and because the aforesaid Dafydd should pay homage to us and has not yet done homage to us.”

Henry III

Henry III

Henry’s complaint was not that Dafydd had taken the homage of the lords of Wales; rather, he had done so before swearing homage to the king. Further letters went back and forth, in which Henry protested at attacks and trespasses committed in the lands of Powys by Dafydd’s men. Thus, the king intervened on behalf of his step-nephew Gruffydd against his blood-nephew Dafydd.

The Powysian dissidents were led by their lord, Gruffydd ap Madog, and Llywelyn’s eldest son Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. Together the two Gruffydds, probably supported by other Welsh lords and Marchers, formed an opposition party to the disabled Llywelyn and his son Dafydd. To add to Llywelyn’s woes, 1237 also witnessed the death of his wife, Princess Joan Plantagenet, and his son-in-law Earl John of Chester.

It appears King Henry trusted no-one. On 4 July he issued an order for the archbishop of Canterbury to escort Dafydd to him at Westminster; the very next day it was agreed that Dafydd would prolong the truce with ‘our faithful Prince Llywelyn and his adherents’, described as the king’s ‘open enemies’.

In early 1238 Dafydd launched a campaign against his elder brother. Over the next few months he took from Gruffydd the lands of Arwystli, Ceri, Cyfeiliog, Mochnant, Caereinon and Mawddy. All of Gruffydd’s territorial gains over the past three years were reversed, leaving him with just Llyn.

With Dafydd in the ascendant, the ageing Llywelyn permitted his second son to take the homage of some of the magnates of Wales. When Henry heard of this, he wrote to Morgan of Caerleon, Rhys ap Gruffudd, Rhys Mechyll, Hywel ap Maredudd, Maredudd ap Rhys, Cynan ap Hywel, Maelgwn ap Maelgwn, Gruffydd ab Owain, Richard ap Hywel, Rhys ap Trahaearn, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (the future prince of Wales), Maredudd ap Maelgwn, Owain ap Hywel and his brother, Owain ap Maredudd and all the tenants of honour of Brecon and Buellt and all the tenants of Richard Clare and all the tenants of the English earls and barons in Wales. This mighty assembly was warned not to pay homage to Dafydd, since:

"the aforesaid magnates hold their lands from us and they owe homage to us and because the aforesaid Dafydd should pay homage to us and has not yet done homage to us.”

Henry III

Henry IIIHenry’s complaint was not that Dafydd had taken the homage of the lords of Wales; rather, he had done so before swearing homage to the king. Further letters went back and forth, in which Henry protested at attacks and trespasses committed in the lands of Powys by Dafydd’s men. Thus, the king intervened on behalf of his step-nephew Gruffydd against his blood-nephew Dafydd.

Published on December 28, 2019 04:41

December 27, 2019

His father's heel

Brenhinedd y Saesson [1233-1234]:

“In that year Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was released from prison, after he had been there six years.” Gruffydd’s father, Llywelyn the Great, had thrown his eldest son in prison in 1228. This was apparently done for no other reason than to get him out of the way for a while, so Llywelyn’s second son Dafydd could secure his grip on the patrimony.

After his release, Gruffudd was able to expand his powerbase from Llyn to include Arwystli, Ceri, Cyfeiliog, Mawddy, Mochnant and Caereinion. These lands were probably granted to him by Llywelyn, or at least acquired with his father’s consent. Llywelyn seems to have revived his earlier plan of giving Gruffydd a large share of Powys to compensate for Dafydd inheriting Gwynedd.

Gruffydd had suffered too much to let bygones be bygones. In the words of Matthew Paris, he had ‘endured his father’s heel’ for long enough. Possibly he was also driven by a desire to avenge his mother, cast aside and treated like a prostitute for the sake of dynastic gain. In 1237, when Llywelyn suffered a stroke that left him partially paralysed, Gruffydd rose in arms against him.

In desperation, Llywelyn pleaded with his old enemy, Henry III of England, for aid. According to Paris, he promised to:

“place himself and all his men under the power and guardianship of the king of the Engilsh to settle the dispute, and of him he would hold his lands in faith and friendship, entering into an indissolvable treaty. And if the king might go on an expedition, to campaign by foot and horse, and with his treasury, attended by his forces, that with his faithful men, he himself [Llywelyn] faithfully would move forward in support.”

Paris added a rhetorical flourish. Of the nobles of Wales, he remarked:

“I fear Danaans, even when bringing gifts.” Danaans were the besiegers of Troy, usually claimed to have been Greeks.

The chronicler also added a quip from Seneca:

“You are never safe when making a treaty with the enemy.”

“In that year Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was released from prison, after he had been there six years.” Gruffydd’s father, Llywelyn the Great, had thrown his eldest son in prison in 1228. This was apparently done for no other reason than to get him out of the way for a while, so Llywelyn’s second son Dafydd could secure his grip on the patrimony.

After his release, Gruffudd was able to expand his powerbase from Llyn to include Arwystli, Ceri, Cyfeiliog, Mawddy, Mochnant and Caereinion. These lands were probably granted to him by Llywelyn, or at least acquired with his father’s consent. Llywelyn seems to have revived his earlier plan of giving Gruffydd a large share of Powys to compensate for Dafydd inheriting Gwynedd.

Gruffydd had suffered too much to let bygones be bygones. In the words of Matthew Paris, he had ‘endured his father’s heel’ for long enough. Possibly he was also driven by a desire to avenge his mother, cast aside and treated like a prostitute for the sake of dynastic gain. In 1237, when Llywelyn suffered a stroke that left him partially paralysed, Gruffydd rose in arms against him.

In desperation, Llywelyn pleaded with his old enemy, Henry III of England, for aid. According to Paris, he promised to:

“place himself and all his men under the power and guardianship of the king of the Engilsh to settle the dispute, and of him he would hold his lands in faith and friendship, entering into an indissolvable treaty. And if the king might go on an expedition, to campaign by foot and horse, and with his treasury, attended by his forces, that with his faithful men, he himself [Llywelyn] faithfully would move forward in support.”

Paris added a rhetorical flourish. Of the nobles of Wales, he remarked:

“I fear Danaans, even when bringing gifts.” Danaans were the besiegers of Troy, usually claimed to have been Greeks.

The chronicler also added a quip from Seneca:

“You are never safe when making a treaty with the enemy.”

Published on December 27, 2019 06:58

December 23, 2019

Lost princes

In September 1228 Llywelyn the Great seized Gruffydd, his son by his first wife, and imprisoned at Degannwy castle. This apparently occured just prior to Henry III’s Ceri campaign in that year; since Ceri was an area that had been under Gruffydd’s control it may be that the king was acting on behalf of his vassal, just as he would later claim to do in 1241.

Over the past twenty years, Llywelyn’s attitude towards his eldest son had swung from one extreme to the other. In 1211 he handed over Gruffydd as a hostage to King John, only to receive him back again in 1215. This was probably because Gruffydd became less valuable to the king after the birth of his brother, Dafydd, in 1212. Via the terms of the original treaty, Llywelyn had surrendered Gruffudd permanently to the king, implying he wanted to get rid of him.

Everything changed in 1226, when Llywelyn granted Gruffydd a large share of Powys. Since Gruffydd’s maternal great-grandfather had been Madog ap Maredudd, the last king of a united Powys, Llywelyn may have hoped to substitute Gruffydd for the heirs of Gwenwynwyn as prince of Powys. For some reason the experiment failed and within two years Gruffydd was imprisoned. This was apparently so Llywelyn’s son by Joan Plantagenet, Prince Dafydd, could secure his grip on the inheritance.

As an aside, Llywelyn’s first wife - and Gruffydd’s mother - is said to have been Tangwystl Goch, daughter of King Reginald of Man. Reginald had no such daughter and there was no such person: the alleged daughter was invented in the 17th century to clean up the genealogy.

The real Tangwystyl Goch was in fact a man. In 1336, about 130 years after the period in question, the survey of Denbigh recorded that Llywelyn had at some unknown time mortgaged land worth £13 to ‘some friend of his named Tangwystl Goch’ - ‘Qui quidem Princeps dedit dictum pignus cuidam amice sue nomine Tanguestel Goch’.

Over the past twenty years, Llywelyn’s attitude towards his eldest son had swung from one extreme to the other. In 1211 he handed over Gruffydd as a hostage to King John, only to receive him back again in 1215. This was probably because Gruffydd became less valuable to the king after the birth of his brother, Dafydd, in 1212. Via the terms of the original treaty, Llywelyn had surrendered Gruffudd permanently to the king, implying he wanted to get rid of him.

Everything changed in 1226, when Llywelyn granted Gruffydd a large share of Powys. Since Gruffydd’s maternal great-grandfather had been Madog ap Maredudd, the last king of a united Powys, Llywelyn may have hoped to substitute Gruffydd for the heirs of Gwenwynwyn as prince of Powys. For some reason the experiment failed and within two years Gruffydd was imprisoned. This was apparently so Llywelyn’s son by Joan Plantagenet, Prince Dafydd, could secure his grip on the inheritance.

As an aside, Llywelyn’s first wife - and Gruffydd’s mother - is said to have been Tangwystl Goch, daughter of King Reginald of Man. Reginald had no such daughter and there was no such person: the alleged daughter was invented in the 17th century to clean up the genealogy.

The real Tangwystyl Goch was in fact a man. In 1336, about 130 years after the period in question, the survey of Denbigh recorded that Llywelyn had at some unknown time mortgaged land worth £13 to ‘some friend of his named Tangwystl Goch’ - ‘Qui quidem Princeps dedit dictum pignus cuidam amice sue nomine Tanguestel Goch’.

Published on December 23, 2019 11:15