David Pilling's Blog, page 38

December 23, 2019

Lost princes

The Annales Cambriae for the year 1212:

“Llywelyn the leader of the North Welsh with his confederate leaders, that is Maelgwyn and Gwenwynwyn, and others of small name but powerful leaders, captured the castles the king had strengthened throughout North Wales and Powys, one after another by the strong hand. Of their garrisons part they killed, part they ransomed and some they scattered”.

The grant by King John to Owain and Gruffydd

The grant by King John to Owain and Gruffydd

This describes the efforts of Llywelyn the Great to destroy royal garrisons in the Perfeddwlad and parts of Powys. King John had earlier attempted to curb Llywelyn’s power by granting the cantref of Rhos except for Degannwy castle within the commote of Creuddyn to Owain ap Dafydd and Gruffydd ap Rhodri. Owain and Gruffydd were the sons of two of Llywelyn’s uncles: he had driven Dafydd into exile and framed Rhodri on charges of what we would call child abuse. The latter was done so Llywelyn could cast aside his first wife and marry Joan, King John’s daughter. Thus he was now at war with his cousins and his father-in-law.

A digital rendering of Degannwy castle

A digital rendering of Degannwy castle

John had also granted Rhufoniog and Dyffryn Clwyd to Dafydd and Gruffydd. Llywelyn’s summer campaign in the Perfeddwlad was aimed squarely at wiping out their power. He managed to retake much of the territory from his kinsmen, though three castles - probably Degannwy, Rhuddlan and Denbigh or Basingwerk - held out. This was in spite of King John, who sent no aid to help Owain and Gruffydd repel Llywelyn’s invasion.

Owain ap Dafydd and his unnamed wife and son are never heard of again, so it is likely they were slaughtered in the conflict. Only a year later, John instructed the Bishop of Winchester to build a house of religion in the manor of Hales in Shropshire. This became known as Halesowen or Halas Owen and was named after Owain ap Dafydd, who had been lord of the manor. It is possible that the religious house was founded in memory of Owain after he perished fighting Llywelyn.

Llywelyn the Great

Llywelyn the Great

Gruffudd ap Rhodri pursued an interesting career. In 1214, two years after Llywelyn’s conquest of the Perfeddwlad, Gruffydd is recorded as a captain of Welsh troops in the king’s service. A man of the same name appears as prominent in the service of Llywelyn in the 1220s and 1230s, and may well be identical with the English partisan of 1212 and 1214.

“Llywelyn the leader of the North Welsh with his confederate leaders, that is Maelgwyn and Gwenwynwyn, and others of small name but powerful leaders, captured the castles the king had strengthened throughout North Wales and Powys, one after another by the strong hand. Of their garrisons part they killed, part they ransomed and some they scattered”.

The grant by King John to Owain and Gruffydd

The grant by King John to Owain and GruffyddThis describes the efforts of Llywelyn the Great to destroy royal garrisons in the Perfeddwlad and parts of Powys. King John had earlier attempted to curb Llywelyn’s power by granting the cantref of Rhos except for Degannwy castle within the commote of Creuddyn to Owain ap Dafydd and Gruffydd ap Rhodri. Owain and Gruffydd were the sons of two of Llywelyn’s uncles: he had driven Dafydd into exile and framed Rhodri on charges of what we would call child abuse. The latter was done so Llywelyn could cast aside his first wife and marry Joan, King John’s daughter. Thus he was now at war with his cousins and his father-in-law.

A digital rendering of Degannwy castle

A digital rendering of Degannwy castleJohn had also granted Rhufoniog and Dyffryn Clwyd to Dafydd and Gruffydd. Llywelyn’s summer campaign in the Perfeddwlad was aimed squarely at wiping out their power. He managed to retake much of the territory from his kinsmen, though three castles - probably Degannwy, Rhuddlan and Denbigh or Basingwerk - held out. This was in spite of King John, who sent no aid to help Owain and Gruffydd repel Llywelyn’s invasion.

Owain ap Dafydd and his unnamed wife and son are never heard of again, so it is likely they were slaughtered in the conflict. Only a year later, John instructed the Bishop of Winchester to build a house of religion in the manor of Hales in Shropshire. This became known as Halesowen or Halas Owen and was named after Owain ap Dafydd, who had been lord of the manor. It is possible that the religious house was founded in memory of Owain after he perished fighting Llywelyn.

Llywelyn the Great

Llywelyn the GreatGruffudd ap Rhodri pursued an interesting career. In 1214, two years after Llywelyn’s conquest of the Perfeddwlad, Gruffydd is recorded as a captain of Welsh troops in the king’s service. A man of the same name appears as prominent in the service of Llywelyn in the 1220s and 1230s, and may well be identical with the English partisan of 1212 and 1214.

Published on December 23, 2019 04:36

The hooded knight

At dawn, on 1 June 1283, three men rode toward the lists prepared for the combat between Peter of Aragon and Charles of Anjou. On the way they sent a message to En Gilbert de Cruilles, a Catalan knight, who was lodged at an inn outside the city. En Gilbert came to meet them, and ‘changed colour’ when he saw that one of the men was King Peter himself, disguised as a squire.

The skeleton of Peter of Aragon

The skeleton of Peter of Aragon

Peter told En Gilbert not to be afraid, and to go and find the seneschal of Gascony, Jean de Grailly. Jean was to be informed that a knight of the king of Aragon wished to speak with him. En Gilbert did as he was told. Shortly afterwards Jean was brought to the lists, where he found a hooded knight waiting for him. This was King Peter, though he kept his face hidden.

Peter formally asked the seneschal:

“Seneschal, I have appeared here before you for the lord king of Aragon, because today is the day on which he and the Lord King Charles have sworn and promised to be in the lists - this very day. And so I ask if you can assure the safety of the lists to the Lord King of Aragon.”

To which Jean answered:

“Lord, I answer you briefly, in the name of my lord the king of England and in mine, that I cannot assure his safety; rather, in the name of God and the king of England, we hold him excused; and we declare him fair and loyal and absolved of his oath. We know for certain that if he came here, nothing could save him.”

Bordeaux

Bordeaux

Then King Peter threw back his hood and said: “Lord seneschal, do you know me?” Jean, astonished, replied “What is this?” “

I,” said Peter, “have come here to fulfil my oath.”

He then rode around the lists, a formal way of ‘searching’ for his opponent. Since Charles and all his knights were still asleep, they weren’t likely to appear. Peter declared he had come to the lists, as he had sworn, and thus kept his oath. If Charles chose not to appear, that was his problem. The king of Aragon then high-tailed it out of Bordeaux and back across the Pyrenees, guided across the shortest route by En Domingo de la Figuera. By the time the Angevin knights were roused and thundered onto the field, their prey was long gone.

The Pyrenees

The Pyrenees

Attached (above, at the top) is a pic of the skeleton of King Peter, partially covered with white linen fabric and layers of dried organic material.

The skeleton of Peter of Aragon

The skeleton of Peter of AragonPeter told En Gilbert not to be afraid, and to go and find the seneschal of Gascony, Jean de Grailly. Jean was to be informed that a knight of the king of Aragon wished to speak with him. En Gilbert did as he was told. Shortly afterwards Jean was brought to the lists, where he found a hooded knight waiting for him. This was King Peter, though he kept his face hidden.

Peter formally asked the seneschal:

“Seneschal, I have appeared here before you for the lord king of Aragon, because today is the day on which he and the Lord King Charles have sworn and promised to be in the lists - this very day. And so I ask if you can assure the safety of the lists to the Lord King of Aragon.”

To which Jean answered:

“Lord, I answer you briefly, in the name of my lord the king of England and in mine, that I cannot assure his safety; rather, in the name of God and the king of England, we hold him excused; and we declare him fair and loyal and absolved of his oath. We know for certain that if he came here, nothing could save him.”

Bordeaux

BordeauxThen King Peter threw back his hood and said: “Lord seneschal, do you know me?” Jean, astonished, replied “What is this?” “

I,” said Peter, “have come here to fulfil my oath.”

He then rode around the lists, a formal way of ‘searching’ for his opponent. Since Charles and all his knights were still asleep, they weren’t likely to appear. Peter declared he had come to the lists, as he had sworn, and thus kept his oath. If Charles chose not to appear, that was his problem. The king of Aragon then high-tailed it out of Bordeaux and back across the Pyrenees, guided across the shortest route by En Domingo de la Figuera. By the time the Angevin knights were roused and thundered onto the field, their prey was long gone.

The Pyrenees

The PyreneesAttached (above, at the top) is a pic of the skeleton of King Peter, partially covered with white linen fabric and layers of dried organic material.

Published on December 23, 2019 01:52

December 22, 2019

Secrets of the king

In June 1283 a knight of Catalonia, En Guillebert de Cruilles, went to Bordeaux to check all was ready for the tournament between Peter of Aragon and Charles of Anjou. He found the seneschal of Gascony, Jean de Grailly, waiting for him with a secret message from Edward I. According to Roman Muntana, a Catalan chronicler, the message was:

“Since he has assured the combats, he [Edward] has heard for certain that the King of France is coming to Bordeaux and is bringing full twelve thousand armed knights. And King Charles will be here, at Bordeaux, on the day the King of France comes, as I have heard. And the King of England sees that he will not be able to hold the lists secure and so he does not wish to be present; he knows for certain that the King of France is coming to Bordeaux to kill the King of Aragon and all who will be with him.”

Jaca

Jaca

En Guillebert sent four runners to Jaca inside the Pyrenees, where King Peter was staying. When Peter received Edward’s warning, he resolved to go to the lists at Bordeaux anyway: if he did not, he would forfeit his right to the crown of Sicily. At the same time he didn’t have enough men to oppose the army of Charles and Philip III.

The king sent for one of his merchants, a man named En Domingo da la Figuera. He ordered Domingo to swear on the Gospels that he would never divulge the secret Peter was about to tell him. Domingo knelt, kissed the king’s foot and swore to keep his mouth shut.

Peter then described his plan. Domingo would take twenty-seven horses from the royal stables to sell at Bordeaux. He would ride on horseback as a great lord, while King Peter rode behind him dressed as a humble squire. A third man, En Bernart de Peratallada, would carry Peter’s money and armour. Bernart would also look after the horses.

Before he set out, Peter sent ten knights to Bordeaux carrying letters to the seneschal, Jean de Grailly. This was so people would get used to the sight of messengers on the road to and from Aragon, and think nothing of it. King Philip ordered Jean to get a message back to Peter, telling him that the lists were ready and Charles was ready to fight for the crown of Sicily. Jean pretended to agree, but sent a message repeating Edward’s earlier warning not to come. Thus the seneschal of Gascony deceived the king of France, who thought his orders were being obeyed.

“Since he has assured the combats, he [Edward] has heard for certain that the King of France is coming to Bordeaux and is bringing full twelve thousand armed knights. And King Charles will be here, at Bordeaux, on the day the King of France comes, as I have heard. And the King of England sees that he will not be able to hold the lists secure and so he does not wish to be present; he knows for certain that the King of France is coming to Bordeaux to kill the King of Aragon and all who will be with him.”

Jaca

JacaEn Guillebert sent four runners to Jaca inside the Pyrenees, where King Peter was staying. When Peter received Edward’s warning, he resolved to go to the lists at Bordeaux anyway: if he did not, he would forfeit his right to the crown of Sicily. At the same time he didn’t have enough men to oppose the army of Charles and Philip III.

The king sent for one of his merchants, a man named En Domingo da la Figuera. He ordered Domingo to swear on the Gospels that he would never divulge the secret Peter was about to tell him. Domingo knelt, kissed the king’s foot and swore to keep his mouth shut.

Peter then described his plan. Domingo would take twenty-seven horses from the royal stables to sell at Bordeaux. He would ride on horseback as a great lord, while King Peter rode behind him dressed as a humble squire. A third man, En Bernart de Peratallada, would carry Peter’s money and armour. Bernart would also look after the horses.

Before he set out, Peter sent ten knights to Bordeaux carrying letters to the seneschal, Jean de Grailly. This was so people would get used to the sight of messengers on the road to and from Aragon, and think nothing of it. King Philip ordered Jean to get a message back to Peter, telling him that the lists were ready and Charles was ready to fight for the crown of Sicily. Jean pretended to agree, but sent a message repeating Edward’s earlier warning not to come. Thus the seneschal of Gascony deceived the king of France, who thought his orders were being obeyed.

Published on December 22, 2019 05:11

December 21, 2019

Sliced and diced

In the winter of 1283 Peter of Aragon and Charles of Anjou agreed to meet at Bordeaux in June, to fight each over the crown of Sicily. They were to bring a hundred knights each and fight until one side was hacked to pieces. Edward I of England, as Duke of Gascony, was invited to act as umpire.

Charles of Anjou conspired with his kinsman, Philip III of France, to ambush Peter at Bordeaux and murder him. This seems to have been a standard tactic: the same fate had overcome Prince Llywelyn of Wales a few months earlier. Philip acted with the full knowledge and authority of the pope. At Paris, before his council, the French king was formally absolved by the papal legate of any oath or obligation towards Peter. This meant the king of Aragon could be betrayed and killed without fear of excommunication.

Philip then rose and said to Charles:

“We will go with you in person, and we shall go so well accompanied that we do not believe the king of Aragon will be so bold as to dare to appear on the day; or, if he does, he will lose his life. Neither the king of England nor anyone else will be able to help him.”

Conwy Castle

Conwy Castle

King Edward was far away at Conwy in North Wales, overseeing the war against Prince Dafydd. His seneschal in Gascony, Jean de Grailly, got wind of the plot and sent word to his master. He also received a frenzied appeal from the pope, ordering him to stop the tournament at Bordeaux. Since the pope had already given King Philip permission to murder Peter, this was sheer hypocrisy.

Edward, horrified at what was about to unfold, wrote to Charles:

“We cannot find it in our heart, nor in any manner possible, that such great cruelty should be done in our presence, nor within our power, nor in any other place where we could put a stop to it. For know truly, that not even to gain two such kingdoms as Sicily and Aragon would we guard the lists where such a battle should take place.”

Edward’s refusal to attend did nothing to stop the tournament going ahead. He dared not openly defy the combined power of France and Anjou, and in any case his entire army was in Wales. His fears were confirmed when Charles and Philip arrived at Bordeaux, not with a hundred knights as agreed, but at the head of twelve thousand armoured cavalry. The moment Peter turned up, he would be sliced and diced.

Edward’s refusal to attend did nothing to stop the tournament going ahead. He dared not openly defy the combined power of France and Anjou, and in any case his entire army was in Wales. His fears were confirmed when Charles and Philip arrived at Bordeaux, not with a hundred knights as agreed, but at the head of twelve thousand armoured cavalry. The moment Peter turned up, he would be sliced and diced.

Although Peter lied to Edward about the invasion of Sicily, the English king had no desire to see him murdered. Such a political assassination would only plunge Europe into an even bigger war, and end any hopes of another crusade. So Edward had to think of something. At the same time he had to cope with the conflict raging in Wales, and the threat of another baronial revolt in England.

It was shit to be the king.

Charles of Anjou conspired with his kinsman, Philip III of France, to ambush Peter at Bordeaux and murder him. This seems to have been a standard tactic: the same fate had overcome Prince Llywelyn of Wales a few months earlier. Philip acted with the full knowledge and authority of the pope. At Paris, before his council, the French king was formally absolved by the papal legate of any oath or obligation towards Peter. This meant the king of Aragon could be betrayed and killed without fear of excommunication.

Philip then rose and said to Charles:

“We will go with you in person, and we shall go so well accompanied that we do not believe the king of Aragon will be so bold as to dare to appear on the day; or, if he does, he will lose his life. Neither the king of England nor anyone else will be able to help him.”

Conwy Castle

Conwy CastleKing Edward was far away at Conwy in North Wales, overseeing the war against Prince Dafydd. His seneschal in Gascony, Jean de Grailly, got wind of the plot and sent word to his master. He also received a frenzied appeal from the pope, ordering him to stop the tournament at Bordeaux. Since the pope had already given King Philip permission to murder Peter, this was sheer hypocrisy.

Edward, horrified at what was about to unfold, wrote to Charles:

“We cannot find it in our heart, nor in any manner possible, that such great cruelty should be done in our presence, nor within our power, nor in any other place where we could put a stop to it. For know truly, that not even to gain two such kingdoms as Sicily and Aragon would we guard the lists where such a battle should take place.”

Edward’s refusal to attend did nothing to stop the tournament going ahead. He dared not openly defy the combined power of France and Anjou, and in any case his entire army was in Wales. His fears were confirmed when Charles and Philip arrived at Bordeaux, not with a hundred knights as agreed, but at the head of twelve thousand armoured cavalry. The moment Peter turned up, he would be sliced and diced.

Edward’s refusal to attend did nothing to stop the tournament going ahead. He dared not openly defy the combined power of France and Anjou, and in any case his entire army was in Wales. His fears were confirmed when Charles and Philip arrived at Bordeaux, not with a hundred knights as agreed, but at the head of twelve thousand armoured cavalry. The moment Peter turned up, he would be sliced and diced.Although Peter lied to Edward about the invasion of Sicily, the English king had no desire to see him murdered. Such a political assassination would only plunge Europe into an even bigger war, and end any hopes of another crusade. So Edward had to think of something. At the same time he had to cope with the conflict raging in Wales, and the threat of another baronial revolt in England.

It was shit to be the king.

Published on December 21, 2019 06:58

Ramon Muntaner

A leaf of the Crònica de Ramon Muntaner, one of the four Catalan Grand Chronicles through which historians view the thirteenth and fourteenth-century military and political affairs in Aragon and Catalonia.

Ramon Muntaner (1265-1336) was a Catalan mercenary and writer, born at Perelada in the province of Girona. As captain of the Catalan Company, a precursor to the ‘Free Companies’ that plagued Europe in the later fourteenth century, he led an adventurous life. His company was made up of Aragonese and Catalan light infantry, known as Almogavars, and under the overall leadership of Roger de Flor - an Italian military adventurer - Ramon led them to Constantinople to aid the Greeks against the Turks.

Later in life, in semi-retirement, Ramon was inspired by a vision to begin work on his chronicle. In the preamble he states:

“I, Ramon Muntaner, native of the town of Perelada and citizen of Valencia, give great thanks to Our Lord the true God and to his blessed Mother, Our Lady Saint Mary, and to all the Heavenly Court, for the favour and grace he has shown me and my escape from the many perils I have been in. Such as thirty-two battles on sea and land in which I have been, as well as in many prisons and torments inflicted on my person in wars in which I have taken part, and many persecutions suffered, as as well in my fortune as in other ways, you will understand from the events of my time.”

Though at times uncritical, excitable and egotistical, Ramon’s account is considered a faithful and vivid history of his time, and is still used as an important source for the pan-European wars of the late thirteenth century.

Ramon Muntaner (1265-1336) was a Catalan mercenary and writer, born at Perelada in the province of Girona. As captain of the Catalan Company, a precursor to the ‘Free Companies’ that plagued Europe in the later fourteenth century, he led an adventurous life. His company was made up of Aragonese and Catalan light infantry, known as Almogavars, and under the overall leadership of Roger de Flor - an Italian military adventurer - Ramon led them to Constantinople to aid the Greeks against the Turks.

Later in life, in semi-retirement, Ramon was inspired by a vision to begin work on his chronicle. In the preamble he states:

“I, Ramon Muntaner, native of the town of Perelada and citizen of Valencia, give great thanks to Our Lord the true God and to his blessed Mother, Our Lady Saint Mary, and to all the Heavenly Court, for the favour and grace he has shown me and my escape from the many perils I have been in. Such as thirty-two battles on sea and land in which I have been, as well as in many prisons and torments inflicted on my person in wars in which I have taken part, and many persecutions suffered, as as well in my fortune as in other ways, you will understand from the events of my time.”

Though at times uncritical, excitable and egotistical, Ramon’s account is considered a faithful and vivid history of his time, and is still used as an important source for the pan-European wars of the late thirteenth century.

Published on December 21, 2019 02:14

December 20, 2019

To fight the enemies of the faith

The massacre of the Sicilian Vespers in 1282 worked to the advantage of Peter of Aragon, who wanted the crown of Sicily for himself. This might be seen as greedy, since he was already King of Aragon, King of Valencia and Count of Barcelona, but one can never have too many hats. In 1262 he married Constance, daughter of Manfred, king of Sicily and bastard son of the Emperor Frederick II. Ever since his marriage Peter had regarded himself as the champion of the Hohenstaufen right to Sicily.

Peter was almost certainly involved in the anti-French resistance movement in Sicily, and with the Byzantine emperor, Michael VIII. In 1281 he gathered fleet of 140 ships and 15,000 men to invade Tunisia, where the Muslim emir had thrown off the yoke of Aragonese suzerainty. A few months later, while the fleet was still gathering, he received a message from the Sicilians, asking him to come and replace Charles of Anjou.

The whole of Europe watched nervously to see which way Peter would jump. He kept his intentions a secret from everyone. From the hour of the departure of his fleet from Portfangos, near the mouth of the Ebro, his own sailors did not know their destination. In July Peter wrote to Edward I in England, informing him that the fleet was indeed destined for Tunisia, ‘to fight the enemies of the faith, if pleasing to the pope’.

It was a lie. On 30 August Peter crossed to Trapani on the west coast of Sicily, and on 1 September was crowned king of Sicily at Palermo. Those Angevins that remained on the island after the Sicilian Vespers were driven out. Pope Martin IV was outraged and hurled bulls of excommunication at Peter, who ignored them.

In desperation, Charles of Anjou issued an extraordinary challenge. Instead of fighting a war over Sicily, he offered to fight Peter to the death in a tourney with a hundred knights on either side. It would take place at Bordeaux, on neutral territory, with Edward I invited to act as umpire.

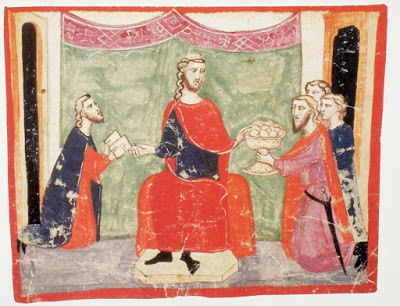

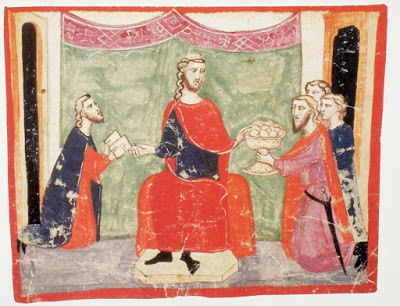

The image is from the Nuova Chronica or New Chronicles of Florence in the 14th century, depicting Peter receiving envoys from the Holy Roman Emperor and Michael VIII, begging him to intervene in the war against Charles of Anjou.

Peter was almost certainly involved in the anti-French resistance movement in Sicily, and with the Byzantine emperor, Michael VIII. In 1281 he gathered fleet of 140 ships and 15,000 men to invade Tunisia, where the Muslim emir had thrown off the yoke of Aragonese suzerainty. A few months later, while the fleet was still gathering, he received a message from the Sicilians, asking him to come and replace Charles of Anjou.

The whole of Europe watched nervously to see which way Peter would jump. He kept his intentions a secret from everyone. From the hour of the departure of his fleet from Portfangos, near the mouth of the Ebro, his own sailors did not know their destination. In July Peter wrote to Edward I in England, informing him that the fleet was indeed destined for Tunisia, ‘to fight the enemies of the faith, if pleasing to the pope’.

It was a lie. On 30 August Peter crossed to Trapani on the west coast of Sicily, and on 1 September was crowned king of Sicily at Palermo. Those Angevins that remained on the island after the Sicilian Vespers were driven out. Pope Martin IV was outraged and hurled bulls of excommunication at Peter, who ignored them.

In desperation, Charles of Anjou issued an extraordinary challenge. Instead of fighting a war over Sicily, he offered to fight Peter to the death in a tourney with a hundred knights on either side. It would take place at Bordeaux, on neutral territory, with Edward I invited to act as umpire.

The image is from the Nuova Chronica or New Chronicles of Florence in the 14th century, depicting Peter receiving envoys from the Holy Roman Emperor and Michael VIII, begging him to intervene in the war against Charles of Anjou.

Published on December 20, 2019 11:16

The Sicilian Vespers

“Lord God, since it has pleased you to ruin my fortune, let me go down in small steps.”

This is a quote from Charles of Anjou, when he was informed of the massacre of the French inhabitants of Sicily in April 1282. The massacre is known as the Sicilian Vespers, since it began at the start of Vespers, the sunset prayer that marked the beginning of the night vigil on Easter Monday (30 March). Coincidentally, it occured just 24 hours after the rising of Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd against Edward I in Wales.

The Sicilian Vespers

The Sicilian Vespers

Edward was on the Welsh Marches when news reached him of trouble in Sicily. Ferrante of Aragon, writing from France, informed the king of the news in a most casual way:

“Also, my lord, know that I have learnt from certain merchants who lately came to Court that it is decided that the pope will soon arrive at Marseilles; they also told me as sure that five Sicilian cities have risen against King Charles and killed all the French living in them. There is no other news in Paris worth repeating”.

Charles of Anjou

Charles of Anjou

The Vespers was apparently triggered by an incident involving a French soldier named Druet, who tried to chat up a woman outside the Church of the Holy Spirit near Palermo. She resisted - other sources say she pulled a knife on him - and then her husband got involved. A scuffle broke out, Druet was killed, and then his comrades were slaughtered by an angry mob. The news quickly spread and within hours the entire island was in revolt against the French occupiers. Within six weeks over five thousand French, soldiers and civilians, were put to death. Foreign clergymen who could not pronounce the word “ciciri” - a sound the French tongue could never accurately reproduce - were also butchered.

Despite the tales of Druet and his botched womanising, the Vespers was probably organised in advance. King Charles had planned to make Naples the capital of his empire of the Two Sicilies, and use the Mediterannean as a springboard for the conquest of Constantinople. He would thus become king and emperor, the heir to the Roman Empire, and the most powerful Christian ruler in the world.

Michael VIII

Michael VIII

The Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII, had seized the throne by deposing and blinding his nephew, John IV Laskaris, on the latter’s eleventh birthday. This supremely ruthless and competent man, who made Edward I and Philip le Bel look like schoolboys, wasn’t about to submit to some Angevin pretender. It is possible that the massacre was organised by Michael and Peter of Aragon via John of Procida, an Italian physician and diplomat: John had good reason to hate Charles of Anjou, since his wife and daughter had been raped by a French knight in Angevin service. Afterwards the knight murdered John’s son. It is theorised that John lay at the heart of a “vast European conspiracy” against Charles and his ally the pope.

Michael VIII made no effort to hide his role in the affair. In latter years he proudly declared:

"Should I dare to claim that I was God's instrument to bring freedom to the Sicilians, then I should only be stating the truth."

This is a quote from Charles of Anjou, when he was informed of the massacre of the French inhabitants of Sicily in April 1282. The massacre is known as the Sicilian Vespers, since it began at the start of Vespers, the sunset prayer that marked the beginning of the night vigil on Easter Monday (30 March). Coincidentally, it occured just 24 hours after the rising of Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd against Edward I in Wales.

The Sicilian Vespers

The Sicilian VespersEdward was on the Welsh Marches when news reached him of trouble in Sicily. Ferrante of Aragon, writing from France, informed the king of the news in a most casual way:

“Also, my lord, know that I have learnt from certain merchants who lately came to Court that it is decided that the pope will soon arrive at Marseilles; they also told me as sure that five Sicilian cities have risen against King Charles and killed all the French living in them. There is no other news in Paris worth repeating”.

Charles of Anjou

Charles of AnjouThe Vespers was apparently triggered by an incident involving a French soldier named Druet, who tried to chat up a woman outside the Church of the Holy Spirit near Palermo. She resisted - other sources say she pulled a knife on him - and then her husband got involved. A scuffle broke out, Druet was killed, and then his comrades were slaughtered by an angry mob. The news quickly spread and within hours the entire island was in revolt against the French occupiers. Within six weeks over five thousand French, soldiers and civilians, were put to death. Foreign clergymen who could not pronounce the word “ciciri” - a sound the French tongue could never accurately reproduce - were also butchered.

Despite the tales of Druet and his botched womanising, the Vespers was probably organised in advance. King Charles had planned to make Naples the capital of his empire of the Two Sicilies, and use the Mediterannean as a springboard for the conquest of Constantinople. He would thus become king and emperor, the heir to the Roman Empire, and the most powerful Christian ruler in the world.

Michael VIII

Michael VIIIThe Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII, had seized the throne by deposing and blinding his nephew, John IV Laskaris, on the latter’s eleventh birthday. This supremely ruthless and competent man, who made Edward I and Philip le Bel look like schoolboys, wasn’t about to submit to some Angevin pretender. It is possible that the massacre was organised by Michael and Peter of Aragon via John of Procida, an Italian physician and diplomat: John had good reason to hate Charles of Anjou, since his wife and daughter had been raped by a French knight in Angevin service. Afterwards the knight murdered John’s son. It is theorised that John lay at the heart of a “vast European conspiracy” against Charles and his ally the pope.

Michael VIII made no effort to hide his role in the affair. In latter years he proudly declared:

"Should I dare to claim that I was God's instrument to bring freedom to the Sicilians, then I should only be stating the truth."

Published on December 20, 2019 05:03

December 19, 2019

A pot boy and a donkey

In the autumn of 1281 Margaret of Provence, dowager queen of France, decided to gather a coalition against Charles of Anjou, King of Sicily. She and her sister, Eleanor (the widow of Henry III of England), had spent years in fruitless negotiations to get practical recognition of their rights in Provence and the adjacent county of Fourcalquier. Charles, in their view, had unjustly deprived them. Added to this confusing mix were the ambitions of Charles of Salerno, also heir to Provence, and German pretensions to acquire the entire kingdom of Arles, of which Provence was the richest part.

In October Margaret wrote to her nephew, Edward I of England, informing him that her allies had agreed to assemble a great army at Lyons the following May. They included Edward’s brother Edmund, in his role as titular Count of Brie and Champagne, the archbishop of Lyons, the count of Savoy, Duke Robert of Burgundy, the count of the Free County, the count of Alencon, and several others. All these were endangered or annoyed by Angevin pretensions, and ready to form a grand military alliance to defend their interests.

Edward, so aggressive inside the British Isles, pursued the opposite policy on the continent. His desire was to unite all the princes of Europe for a grand passagium to the Holy Land: a proper one this time, in which everyone took part instead of leaving him alone to face forty thousand Mamluk berserkers with a pot boy and a donkey. At the same time he was fond of his mother and aunt, and couldn’t duck out of his feudal responsiblities.

In November he wrote to Margaret and promised to send troops to her aid, but also begged her to act prudently. At the same time he wrote to Pope Martin IV and his kinsman Charles of Salerno to urge settlement by arbitration. He explained that his ties with Margaret would compel him to assist her if it came to war. In an unusually personal touch - Edward’s letters are usually terse and businesslike - he opened his mind to Charles:

“I am very reluctant in this matter. My heart is not in it, on account of the love between you and me. I pray you, do not take it amiss, for I call God to witness that, if the thing affected me only, I would do nothing against your wishes.”

In the event, war did not come. Charles was ready to fight in Provence, but Margaret’s allies - known as the League of Macon - made a mess of their preparations. A few weeks before they were due to go into action, the Sicilians revolted against Charles of Anjou.

Attached is Margaret’s letter to Edward and an image of her seal.

In October Margaret wrote to her nephew, Edward I of England, informing him that her allies had agreed to assemble a great army at Lyons the following May. They included Edward’s brother Edmund, in his role as titular Count of Brie and Champagne, the archbishop of Lyons, the count of Savoy, Duke Robert of Burgundy, the count of the Free County, the count of Alencon, and several others. All these were endangered or annoyed by Angevin pretensions, and ready to form a grand military alliance to defend their interests.

Edward, so aggressive inside the British Isles, pursued the opposite policy on the continent. His desire was to unite all the princes of Europe for a grand passagium to the Holy Land: a proper one this time, in which everyone took part instead of leaving him alone to face forty thousand Mamluk berserkers with a pot boy and a donkey. At the same time he was fond of his mother and aunt, and couldn’t duck out of his feudal responsiblities.

In November he wrote to Margaret and promised to send troops to her aid, but also begged her to act prudently. At the same time he wrote to Pope Martin IV and his kinsman Charles of Salerno to urge settlement by arbitration. He explained that his ties with Margaret would compel him to assist her if it came to war. In an unusually personal touch - Edward’s letters are usually terse and businesslike - he opened his mind to Charles:

“I am very reluctant in this matter. My heart is not in it, on account of the love between you and me. I pray you, do not take it amiss, for I call God to witness that, if the thing affected me only, I would do nothing against your wishes.”

In the event, war did not come. Charles was ready to fight in Provence, but Margaret’s allies - known as the League of Macon - made a mess of their preparations. A few weeks before they were due to go into action, the Sicilians revolted against Charles of Anjou.

Attached is Margaret’s letter to Edward and an image of her seal.

Published on December 19, 2019 06:27

December 18, 2019

The heart of a king

In December 1291 the heart of Henry III of England was dispatched for burial to the abbess and convent of Fontrevault in northern France, southeast of Angers. In his letter to the abbess Edward I described his father as ‘of celebrated memory’ and confirmed all the rights and privileges bestowed by his Angevin forebears on the convent. Henry III’s heart was laid to rest in Anjou, the homeland of his ancestors, placed next to his mighty forebears.

This was part of a long-running practice of honouring the Angevin past. At Christmas 1286 Edward had sent six pieces of gold to Fontrevault, to be laid upon the tombs of Henry II, Richard I, Eleanor of Aquitaine and Isabella of Angouleme. In 1330 his grandson Edward III was still giving alms to Fontrevault, the mausoleum of the Angevin dynasty.

By Edward I’s reign the continental possessions of his house had shrunk to a fragment of their former glory; only the duchy of Aquitaine and county of Ponthieu remained of a domain that had consisted of much of western France and its Atlantic seaboard. A line of kings that had once ruled a great network of continental territories, larger than that controlled by the Capetian kings of France, could not easily forget that legacy. This explains the grim determination to hang onto Aquitaine, despite repeated French invasions and enormous financial and logistical problems: it could even be argued that Edward I sacrificed his ambitions in Scotland to recover Aquitaine, though that would require a wider perspective on events than many are maybe prepared to admit.

The heart of the Plantagenet dynasty, literally and figuratively, lay in France.

This was part of a long-running practice of honouring the Angevin past. At Christmas 1286 Edward had sent six pieces of gold to Fontrevault, to be laid upon the tombs of Henry II, Richard I, Eleanor of Aquitaine and Isabella of Angouleme. In 1330 his grandson Edward III was still giving alms to Fontrevault, the mausoleum of the Angevin dynasty.

By Edward I’s reign the continental possessions of his house had shrunk to a fragment of their former glory; only the duchy of Aquitaine and county of Ponthieu remained of a domain that had consisted of much of western France and its Atlantic seaboard. A line of kings that had once ruled a great network of continental territories, larger than that controlled by the Capetian kings of France, could not easily forget that legacy. This explains the grim determination to hang onto Aquitaine, despite repeated French invasions and enormous financial and logistical problems: it could even be argued that Edward I sacrificed his ambitions in Scotland to recover Aquitaine, though that would require a wider perspective on events than many are maybe prepared to admit.

The heart of the Plantagenet dynasty, literally and figuratively, lay in France.

Published on December 18, 2019 04:37

December 17, 2019

Kissing cousins (3)

Philip III of France was not deterred by the failure of his efforts to invade Castile in 1276. Throughout 1277 war was still imminent, despite the best efforts of the pope to broker peace. By this point war had broken out in Wales, and Edward I of England was no longer in a position to help Philip. In October 1277, during the last stages of the Welsh war, Edward wrote to excuse himself from military service and informed Philip that two envoys, Maurice de Craon and Jean de Grailly, would travel to France to explain his position.

Alfonso of Castile

Alfonso of Castile

As a friend bound by responsible ties to his brother-in-law, King Alfonso, Edward decided to try and make peace between France and Castile. It was a slow process, and two years passed before Alfonso agreed to enter into negotiations for a truce. He also agreed to entrust Edward with the task of mediating peace at a formal conference. The truce was made at Paris in spring 1280, and in May Alfonso publicly thanked Edward for his good offices as peace-maker.

Alfonso then dramatically changed his tune. At the same time as he thanked Edward, he sent envoys to Charles of Salerno asking him to replace the English king as mediator. His change of mind caused a great stir in Europe. Philip III was baffled, and thought that Edward must have offended Alfonso by freezing him out of treaty negotiations at Amiens. In fact Edward had kept Alfonso fully informed of the talks at Amiens and received a warm letter of thanks in return, along with congratulations that Edward had managed to acquire the county of Ponthieu. Margaret of France, Edward’s aunt, expressed surprise at the incident in a letter to her nephew.

So what was Alfonso’s beef? His behaviour was odd. In July 1280 Edward’s agents in Paris reported to their master that Castilian agents were spreading malicious reports against Edward in the French court. Fortunately Philip refused to believe them, while Edward was more amused than concerned. In a letter to the French king, he surmised that Alfonso must have considered him ‘slothful and sleepy’ in defending the interests of Castile, and thus taken offence. Again one is left with the impression that this was just one big family row, in which everyone indulged in gossip and laughed at silly cousin Alfonso making a fool of himself.

The English king’s response was to invite his kinsman Charles of Salerno to hold the peace conference in Gascony in December. All the relevant parties turned up, though the people of Bayonne expressed alarm at the size of the armed retinue brought by King Alfonso. The talks went off without a hitch, or anyone offering to ram something sharp into someone else. War in Europe was averted, at least for a time, and the seneschal of Gascony wrote to Edward informing him that ‘the kings, princes and magnates went away well contented with you and yours’.

Alfonso of Castile

Alfonso of CastileAs a friend bound by responsible ties to his brother-in-law, King Alfonso, Edward decided to try and make peace between France and Castile. It was a slow process, and two years passed before Alfonso agreed to enter into negotiations for a truce. He also agreed to entrust Edward with the task of mediating peace at a formal conference. The truce was made at Paris in spring 1280, and in May Alfonso publicly thanked Edward for his good offices as peace-maker.

Alfonso then dramatically changed his tune. At the same time as he thanked Edward, he sent envoys to Charles of Salerno asking him to replace the English king as mediator. His change of mind caused a great stir in Europe. Philip III was baffled, and thought that Edward must have offended Alfonso by freezing him out of treaty negotiations at Amiens. In fact Edward had kept Alfonso fully informed of the talks at Amiens and received a warm letter of thanks in return, along with congratulations that Edward had managed to acquire the county of Ponthieu. Margaret of France, Edward’s aunt, expressed surprise at the incident in a letter to her nephew.

So what was Alfonso’s beef? His behaviour was odd. In July 1280 Edward’s agents in Paris reported to their master that Castilian agents were spreading malicious reports against Edward in the French court. Fortunately Philip refused to believe them, while Edward was more amused than concerned. In a letter to the French king, he surmised that Alfonso must have considered him ‘slothful and sleepy’ in defending the interests of Castile, and thus taken offence. Again one is left with the impression that this was just one big family row, in which everyone indulged in gossip and laughed at silly cousin Alfonso making a fool of himself.

The English king’s response was to invite his kinsman Charles of Salerno to hold the peace conference in Gascony in December. All the relevant parties turned up, though the people of Bayonne expressed alarm at the size of the armed retinue brought by King Alfonso. The talks went off without a hitch, or anyone offering to ram something sharp into someone else. War in Europe was averted, at least for a time, and the seneschal of Gascony wrote to Edward informing him that ‘the kings, princes and magnates went away well contented with you and yours’.

Published on December 17, 2019 06:15