David Pilling's Blog, page 46

October 5, 2019

Expanding states

In the mid to late thirteenth century the big beasts of Western Europe decided to devour their less powerful neighbours, and then each other. Edward I’s efforts in Wales and Scotland are perhaps the best-known - certainly in modern times, thanks to the influence of films and novels and politics - but he was scarcely unique. Philip III of France mounted a disastrous invasion of Aragon, and his even more aggressive successor Philip III made determined efforts to conquer Flanders and Gascony. He also contemplated a full-scale invasion of England. Meanwhile the King of the Germans, Adolf of Nassau, waged war against his own people in an effort to turn the Holy Roman Empire into one vast centralized state.

Naturally, all this aggressive expansionism met with resistance. Edward failed in Scotland but succeeded in Wales; Philip failed in Gascony and imposed a sort of half-conquest on Flanders; Adolf failed in all respects and was chopped up on a German battlefield. His dismal fate was shared by the likes of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, whose efforts to establish a united Wales ended in disaster, and the Count of Holland, flung into a ditch and stabbed to death by his own nobles.

Other than crude power-grabbing, what was the ideology beyond the expansion of medieval states? One might say it was the logical effort to bind together a single people with their own laws, language and culture. That’s a little too pat, and doesn’t explain why Llywelyn, Adolf and Count Floris (among others) were abandoned at crucial times by their own people.

Philip le Bel

Philip le Bel

One aspect was the ‘religion of monarchy’. Philip le Bel was the greatest exponent of this: he was the most powerful monarch in Europe, the Vicar of God, the chief pillar of the Church, the inheritor of the holy insignia and unifying mission of Charlemagne. To oppose him was not only evil, it was sacrilegious. In his mind, and that of his fanatical chancellor Pierre Flote, there was no conflict. As Guillaume de Nogaret, another of Philip’s ministers, succinctly expressed it:

‘No true believer can fail to see that the interests of the French monarchy and the interests of the Church are identical. The Flemings are heretics, and Pope Boniface is a heretic, because they oppose the King of France, who is the pillar of the Church’.

The third pic is of the imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire, a terrific bit of bling.

Naturally, all this aggressive expansionism met with resistance. Edward failed in Scotland but succeeded in Wales; Philip failed in Gascony and imposed a sort of half-conquest on Flanders; Adolf failed in all respects and was chopped up on a German battlefield. His dismal fate was shared by the likes of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, whose efforts to establish a united Wales ended in disaster, and the Count of Holland, flung into a ditch and stabbed to death by his own nobles.

Other than crude power-grabbing, what was the ideology beyond the expansion of medieval states? One might say it was the logical effort to bind together a single people with their own laws, language and culture. That’s a little too pat, and doesn’t explain why Llywelyn, Adolf and Count Floris (among others) were abandoned at crucial times by their own people.

Philip le Bel

Philip le BelOne aspect was the ‘religion of monarchy’. Philip le Bel was the greatest exponent of this: he was the most powerful monarch in Europe, the Vicar of God, the chief pillar of the Church, the inheritor of the holy insignia and unifying mission of Charlemagne. To oppose him was not only evil, it was sacrilegious. In his mind, and that of his fanatical chancellor Pierre Flote, there was no conflict. As Guillaume de Nogaret, another of Philip’s ministers, succinctly expressed it:

‘No true believer can fail to see that the interests of the French monarchy and the interests of the Church are identical. The Flemings are heretics, and Pope Boniface is a heretic, because they oppose the King of France, who is the pillar of the Church’.

The third pic is of the imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire, a terrific bit of bling.

Published on October 05, 2019 05:07

October 3, 2019

Execution

So the execution of Prince Dafydd at Shrewsbury in 1283. I'm having to rush since today is the anniversary, but that's my fault for attempting to pack his career into just three days.

Anyway. This is a grim subject but the precise method of Dafydd's death is not clear. The version repeated in some modern accounts is that he was hanged, drawn and quartered i.e. taken to the gallows, hanged, cut down while still alive, eviscerated, and only then beheaded and quartered. Slow torture.

This is not readily apparent from medieval accounts of the execution. As usual they don't tally. The Chronicle of Bury St Edmunds says that Dafydd:

...was convicted of treason, lese-majesté and sacrilege, and condemned to be drawn, hanged, beheaded, burned and quartered.

The Annals of Worcester says:

He was dragged through the chanting citizens of Shrewsbury by horses, then hanged, afterwards beheaded.

The Annales Cambriae says:

On 3 September following he was hanged and drawn at Shrewsbury and divided into four parts with head cut off. Etc.

The key word is 'drawn': was Dafydd 'drawn' to the gallows or 'drawn' as in being cut apart while still alive? On balance, it appears he was hanged, cut down while still alive, beheaded and then drawn. This was nasty enough, of course, but not quite the prolonged torture of living disembowelment sometimes described.

There's something horrible and degrading about picking over the accounts of a grisly medieval execution, but we should probably try and get it right. Dafydd was not the first victim of the English judiciary to suffer in this way: an assassin who tried to kill Henry III was torn apart by horses a few decades earlier. He was, however, the first nobleman to be executed for what was effectively high treason, even though the actual conviction was for cumulative offences and 'high treason' was not yet on the statute book.

Anyway. This is a grim subject but the precise method of Dafydd's death is not clear. The version repeated in some modern accounts is that he was hanged, drawn and quartered i.e. taken to the gallows, hanged, cut down while still alive, eviscerated, and only then beheaded and quartered. Slow torture.

This is not readily apparent from medieval accounts of the execution. As usual they don't tally. The Chronicle of Bury St Edmunds says that Dafydd:

...was convicted of treason, lese-majesté and sacrilege, and condemned to be drawn, hanged, beheaded, burned and quartered.

The Annals of Worcester says:

He was dragged through the chanting citizens of Shrewsbury by horses, then hanged, afterwards beheaded.

The Annales Cambriae says:

On 3 September following he was hanged and drawn at Shrewsbury and divided into four parts with head cut off. Etc.

The key word is 'drawn': was Dafydd 'drawn' to the gallows or 'drawn' as in being cut apart while still alive? On balance, it appears he was hanged, cut down while still alive, beheaded and then drawn. This was nasty enough, of course, but not quite the prolonged torture of living disembowelment sometimes described.

There's something horrible and degrading about picking over the accounts of a grisly medieval execution, but we should probably try and get it right. Dafydd was not the first victim of the English judiciary to suffer in this way: an assassin who tried to kill Henry III was torn apart by horses a few decades earlier. He was, however, the first nobleman to be executed for what was effectively high treason, even though the actual conviction was for cumulative offences and 'high treason' was not yet on the statute book.

Published on October 03, 2019 08:53

The tragedy of Dafydd (6)

Prince Dafydd spent two years in exile at the court of Edward I, apparently doing very little. His Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, who had fled with him into England, was much more pro-active and set up headquarters at Shrewsbury. From here Gruffudd and his sons led frequent raids into their former territory in southern Powys, now occupied by the armies of Prince Llywelyn.

When war broke out between Edward and Llywelyn in 1276, Dafydd was sent to join the royal army gathering at Chester under the Earl of Warwick. He served with his retinue or 'teulu' of two hundred Welsh horsemen, among hundreds of English knights and men-at-arms. All we know of Dafydd's actions is an order from the king addressed to him and Guncelin de Badlesmere, justice of Chester, ordering them to 'receive to the king's peace' the Welsh of Bromfield, the district corresponding to the southern part of the present county of Denbighshire. This order was dated 26 December, so Dafydd spent a busy Christmas and New Year forcing his countrymen in Bromfield to submit to Edward's will.

This was followed by a general advance upon Llywelyn's position in the middle Dee, in which Dafydd again probably served as Warwick's army drove back the Welsh from the immediate west of Chester. Meanwhile feudal army stores and men continued to pour into the town, which would serve Edward as a main base over the summer. Orders survive for companies of workmen and crossbowmen sent up to Chester ahead of the king's advance.

We know more of Dafydd's actions in the spring of 1277. On 12 April 1277 he and Warwick advanced into Powys Fadog and forced Gruffudd ap Madog to partition the lordship between himself and his brothers, or be permanently disinherited. Apart from some lingering resistance at Castell Dinas Bran, this removed Llywelyn's last ally outside Gwynedd and left him isolated west of the Conwy, surrounded by royal armies and navies. Faced with starvation, he submitted in November.

Dafydd did not get all that he wanted from the king's war. In August, at Flint, Edward had promised that he would restore to Dafydd and his brother Owain half of Snowdonia, Anglesey and Penllyn, with the Lleyn peninsular, if he defeated Llywelyn. Alternatively , should Edward decided to keep the whole of Anglesey, the rest of Gwynedd would be divided between Dafydd and Owain. Llywelyn would be left totally disinherited.

In the event, Edward decided to force terms on Llywelyn rather than destroy him: the total defeat of the prince required an invasion of Snowdonia, and the king was too cautious a military commander to take that risk in the dead of winter. Dafydd was therefore granted the land of Hopedale and two of the Four Cantreds, Dyffrwyn Clwyd and Rhufoniog: this was, in fact, a renewal of the original grant Edward had made to Dafydd when the latter initially defected in 1263. So Dafydd could have his cake and like it.

But Dafydd wanted more cake. MORE CAKE FOR DAFYDD!

When war broke out between Edward and Llywelyn in 1276, Dafydd was sent to join the royal army gathering at Chester under the Earl of Warwick. He served with his retinue or 'teulu' of two hundred Welsh horsemen, among hundreds of English knights and men-at-arms. All we know of Dafydd's actions is an order from the king addressed to him and Guncelin de Badlesmere, justice of Chester, ordering them to 'receive to the king's peace' the Welsh of Bromfield, the district corresponding to the southern part of the present county of Denbighshire. This order was dated 26 December, so Dafydd spent a busy Christmas and New Year forcing his countrymen in Bromfield to submit to Edward's will.

This was followed by a general advance upon Llywelyn's position in the middle Dee, in which Dafydd again probably served as Warwick's army drove back the Welsh from the immediate west of Chester. Meanwhile feudal army stores and men continued to pour into the town, which would serve Edward as a main base over the summer. Orders survive for companies of workmen and crossbowmen sent up to Chester ahead of the king's advance.

We know more of Dafydd's actions in the spring of 1277. On 12 April 1277 he and Warwick advanced into Powys Fadog and forced Gruffudd ap Madog to partition the lordship between himself and his brothers, or be permanently disinherited. Apart from some lingering resistance at Castell Dinas Bran, this removed Llywelyn's last ally outside Gwynedd and left him isolated west of the Conwy, surrounded by royal armies and navies. Faced with starvation, he submitted in November.

Dafydd did not get all that he wanted from the king's war. In August, at Flint, Edward had promised that he would restore to Dafydd and his brother Owain half of Snowdonia, Anglesey and Penllyn, with the Lleyn peninsular, if he defeated Llywelyn. Alternatively , should Edward decided to keep the whole of Anglesey, the rest of Gwynedd would be divided between Dafydd and Owain. Llywelyn would be left totally disinherited.

In the event, Edward decided to force terms on Llywelyn rather than destroy him: the total defeat of the prince required an invasion of Snowdonia, and the king was too cautious a military commander to take that risk in the dead of winter. Dafydd was therefore granted the land of Hopedale and two of the Four Cantreds, Dyffrwyn Clwyd and Rhufoniog: this was, in fact, a renewal of the original grant Edward had made to Dafydd when the latter initially defected in 1263. So Dafydd could have his cake and like it.

But Dafydd wanted more cake. MORE CAKE FOR DAFYDD!

Published on October 03, 2019 01:03

October 2, 2019

The tragedy of Dafydd (5)

In September 1267 Dafydd was at the ford of Rhyd Chwima, the ford by Montgomery, to take part in the treaty negotiations between his brother Llywelyn and Henry III. Here, in the presence of the papal legate Ottobuono, Llywelyn knelt before the king and swore homage and fealty for the principality of Wales. He was the first and last Prince of Wales to gain such explicit recognition of his title from the English crown, but the arrangement did not secure any kind of political independence. Llywelyn’s authority as prince stemmed from his vassal status, a subordinate of the English king, just as the Count of Flanders was a vassal of the Capetian kings of France.

Dafydd was the elephant in the room. Via the terms of the Treaty of Montgomery, Llywelyn was bound to provide for his younger brother, who had defected to the English back in 1263. During the talks it was “specially ordained” that provision would be made for Dafydd, and that Llywelyn would restore to him the land he held in Wales before his defection. Further arrangements would be made if Dafydd was not satisfied. This appears to have been an effort to honour the agreement of 1263, in which Edward had promised to come to no agreement with Llywelyn without consulting Dafydd. To avoid breaking that treaty, the decision was passed to Llywelyn.

This must have annoyed Dafydd, who now found himself dependent on his brother’s charity. For all his ambition and striving, the best he could hope for was to be granted an estate within the borders of Llywelyn’s principality.

Dafydd ate his heart out for several years. Llywelyn, whose patience with his permanently disgruntled sibling was remarkable, welcomed him back to the fold. Together they waged war against Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, and invaded his lands of Senghenydd. Here Dafydd witnessed Llywelyn’s first real defeat as the prince failed to prevent the construction of Clare’s mighty new castle at Caerphilly. This seemed to plant an idea in his mind, though it took a while to germinate.

In early 1274 Dafydd entered into a plot with Owain ap Gwenwynwyn, eldest son of the lord of southern Powys. Together they planned to murder Llywelyn at Christmas, when the prince’s bodyguard was away touring his estates. The plan was for Dafydd to open a gate at night to allow Owain and his men into the court. Together they would go to Llywelyn’s bedchamber and murder him. In the morning Dafydd would be proclaimed the new Prince of Wales, presumably while Llywelyn’s body was quietly smuggled out of a rear entrance.

The plan was foiled by a snowstorm, which obliged Owain and his band of assassins to turn back. Llywelyn then got wind of the plot and summoned Dafydd to explain himself, but he and Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn fled over the border into England. The new king, Edward I, welcomed these useful idiots…valuable political allies…to his court.

Dafydd was the elephant in the room. Via the terms of the Treaty of Montgomery, Llywelyn was bound to provide for his younger brother, who had defected to the English back in 1263. During the talks it was “specially ordained” that provision would be made for Dafydd, and that Llywelyn would restore to him the land he held in Wales before his defection. Further arrangements would be made if Dafydd was not satisfied. This appears to have been an effort to honour the agreement of 1263, in which Edward had promised to come to no agreement with Llywelyn without consulting Dafydd. To avoid breaking that treaty, the decision was passed to Llywelyn.

This must have annoyed Dafydd, who now found himself dependent on his brother’s charity. For all his ambition and striving, the best he could hope for was to be granted an estate within the borders of Llywelyn’s principality.

Dafydd ate his heart out for several years. Llywelyn, whose patience with his permanently disgruntled sibling was remarkable, welcomed him back to the fold. Together they waged war against Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, and invaded his lands of Senghenydd. Here Dafydd witnessed Llywelyn’s first real defeat as the prince failed to prevent the construction of Clare’s mighty new castle at Caerphilly. This seemed to plant an idea in his mind, though it took a while to germinate.

In early 1274 Dafydd entered into a plot with Owain ap Gwenwynwyn, eldest son of the lord of southern Powys. Together they planned to murder Llywelyn at Christmas, when the prince’s bodyguard was away touring his estates. The plan was for Dafydd to open a gate at night to allow Owain and his men into the court. Together they would go to Llywelyn’s bedchamber and murder him. In the morning Dafydd would be proclaimed the new Prince of Wales, presumably while Llywelyn’s body was quietly smuggled out of a rear entrance.

The plan was foiled by a snowstorm, which obliged Owain and his band of assassins to turn back. Llywelyn then got wind of the plot and summoned Dafydd to explain himself, but he and Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn fled over the border into England. The new king, Edward I, welcomed these useful idiots…valuable political allies…to his court.

Published on October 02, 2019 12:42

The tragedy of Dafydd (4)

In March 1264 the alliance of Prince Dafydd and the Lord Edward kicked into gear. Civil war had broken out in England, and the conflict spilled over into the Welsh March. Edward arrived in the marches in February, where he deprived the Bohuns of their castles of Hay, Huntingdon and Brecon and handed them over to Roger Mortimer. He then turned about and attempted to relieve Gloucester, where the rebel barons had forced entry to the town and laid siege to the castle. John Giffard and another man allegedly tricked the porters by disguising themselves as Welsh merchants, only to throw off their outfits as soon as the gates were opened.

Three days before Edward’s first attempt to save Gloucester, Prince Dafydd and William de Zouche, the justice of Chester, poured over the border with an army of men of Cheshire and Shropshire and attacked the lands of Robert de Ferrers in Staffordshire. Ferrers, the Earl of Derby and at this point a Montfortian, had just sacked Worcester. The timing of the attack on his estates in Staffordshire is suspicously coincidental with Edward’s march, and suggests it was an attempt to draw Ferrers away from helping his allies at Gloucester. Dafydd and his allies stormed Stafford and seized Chartley Castle (pictured), one of the jewels in Ferrers’s crown. They also plundered churches and burnt the town of Stone, to the north of Stafford. On 2 March they attacked Stafford again, but were repulsed by another group of Marchers, probably led by Ralph Basset of Drayton.

It seems Dafydd did enough to distract Ferrers long enough for Edward to fix up a truce with the rebel leaders at Gloucester, which he promptly broke as soon as their backs were turned. Ferrers was not best pleased:

‘The earl Robert Ferrers, when he came hither, he was well-nigh mad for wrath that they had made agreement. He smote his steed with his spur, as did all his company. And turned himself for wrath again, as quick as he might hasten’ (Robert of Gloucester).

Later in the year, Ferrers got his opportunity for revenge. In May 1264 Edward and his father, Henry III, were captured at the Battles of Lewes. This left Ferrers free to deal with Prince Dafydd and his Marcher allies, who were encamped near the Cheshire border. In late October the earl raised an army twenty thousand strong - surely an exaggeration - and advanced to meet the army raised against him and led by Dafydd, Zouche and James Audley.

The engagement that followed was a disaster for Dafydd: his men broke ranks and fled without striking a blow, and over a hundred killed in the rout. It was a Pyrhhic victory for Ferrers. A few weeks later he was lured to London by Simon de Montfort on false pretences, and then thrown into prison. Simon had his beady eye on Edward’s lordship of Chester, as did Ferrers. Now he had Edward and Ferrers in custody, Simon could grab it for himself.

After his defeat at Chester, Dafydd slips off the radar for a while. He was technically still Edward’s ally, but isn’t known to have played any part in the final defeat of Simon de Montfort at Evesham in 1265. Possibly he was laying low somewhere, living off royal wages and waiting for events to turn in his favour. Shortly before Evesham, his brother Prince Llywelyn had agreed to an alliance with Simon at Pipton. It was a rather one-sided alliance, in which Llywelyn agreed to do something if Simon gave him everything, including the title Prince of Wales.

King Henry, dragged about as Simon’s captive, was compelled to put his seal to a document that went against his entire Welsh policy for the past thirty years. Llywelyn probably knew full well that his ally was doomed, and stayed well clear of the impending catastrophe. After the rebel army was obliterated Edward sent him one of Simon’s severed feet as a present.

Three days before Edward’s first attempt to save Gloucester, Prince Dafydd and William de Zouche, the justice of Chester, poured over the border with an army of men of Cheshire and Shropshire and attacked the lands of Robert de Ferrers in Staffordshire. Ferrers, the Earl of Derby and at this point a Montfortian, had just sacked Worcester. The timing of the attack on his estates in Staffordshire is suspicously coincidental with Edward’s march, and suggests it was an attempt to draw Ferrers away from helping his allies at Gloucester. Dafydd and his allies stormed Stafford and seized Chartley Castle (pictured), one of the jewels in Ferrers’s crown. They also plundered churches and burnt the town of Stone, to the north of Stafford. On 2 March they attacked Stafford again, but were repulsed by another group of Marchers, probably led by Ralph Basset of Drayton.

It seems Dafydd did enough to distract Ferrers long enough for Edward to fix up a truce with the rebel leaders at Gloucester, which he promptly broke as soon as their backs were turned. Ferrers was not best pleased:

‘The earl Robert Ferrers, when he came hither, he was well-nigh mad for wrath that they had made agreement. He smote his steed with his spur, as did all his company. And turned himself for wrath again, as quick as he might hasten’ (Robert of Gloucester).

Later in the year, Ferrers got his opportunity for revenge. In May 1264 Edward and his father, Henry III, were captured at the Battles of Lewes. This left Ferrers free to deal with Prince Dafydd and his Marcher allies, who were encamped near the Cheshire border. In late October the earl raised an army twenty thousand strong - surely an exaggeration - and advanced to meet the army raised against him and led by Dafydd, Zouche and James Audley.

The engagement that followed was a disaster for Dafydd: his men broke ranks and fled without striking a blow, and over a hundred killed in the rout. It was a Pyrhhic victory for Ferrers. A few weeks later he was lured to London by Simon de Montfort on false pretences, and then thrown into prison. Simon had his beady eye on Edward’s lordship of Chester, as did Ferrers. Now he had Edward and Ferrers in custody, Simon could grab it for himself.

After his defeat at Chester, Dafydd slips off the radar for a while. He was technically still Edward’s ally, but isn’t known to have played any part in the final defeat of Simon de Montfort at Evesham in 1265. Possibly he was laying low somewhere, living off royal wages and waiting for events to turn in his favour. Shortly before Evesham, his brother Prince Llywelyn had agreed to an alliance with Simon at Pipton. It was a rather one-sided alliance, in which Llywelyn agreed to do something if Simon gave him everything, including the title Prince of Wales.

King Henry, dragged about as Simon’s captive, was compelled to put his seal to a document that went against his entire Welsh policy for the past thirty years. Llywelyn probably knew full well that his ally was doomed, and stayed well clear of the impending catastrophe. After the rebel army was obliterated Edward sent him one of Simon’s severed feet as a present.

Published on October 02, 2019 01:51

October 1, 2019

The tragedy of Dafydd (3)

In 1262 a rumour spread that Llywelyn ap Gruffudd had died of a sudden illness. The story travelled across the Channel and reached the ears of Henry III at Amiens in France, who immediately sought to take advantage. He dispatched a letter to the Marchers and native princes of Wales, ordering them to look sharp.

The orders issued from Henry’s chancery reveal the king’s strategy in Wales. Now Llywelyn was dead - apparently - it was vital to secure the homage of Welsh lords, which the crown had claimed for generations. Henry knew exactly how to achieve this: divide their strength and pit them against each other. A show of force was also necessary. The king told Roger Mortimer and the other marchers to dissolve any existing alliances with the Welsh, and be ready to muster at Shrewsbury in September for a full-scale invasion. Meanwhile the king sought confirmation from Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys, whether Llywelyn was alive or dead.

Henry sent one of the marchers, James Audley, to order Gruffudd ap Madog to abandon Prince Dafydd and bring Powys Fadog back into the king’s allegiance. It was absolutely essential that Dafydd should not be acknowledged as Llywelyn’s heir. Technically Henry was correct: Dafydd had no automatic right to inherit, since his brothers Owain and Rhodri were still alive. Yet the king’s newfound love for Welsh custom was all part of his determination to ensure Gwynedd was partitioned in the wake of Llywelyn’s death.

Reports of the prince’s demise were greatly exaggerated. He recovered from his illness, prompting the Brut chronicler to remark that Divine providence afforded its sure protection to the Welsh nation.

As usual, Dafydd chose to follow his own unpredictable course. Despite being unceremoniously ditched by the king in 1262, he remained keen on an English alliance. When the Lord Edward came to the marches in the spring of 1263, Dafydd was sought an early meeting. The two men met at Hereford, where on 3 April Edward issued pardons to Dafydd and his men for waging war against the king. Via the same agreement he promised to: …

assist Dafydd in recovering his reasonable inheritance beyond the Conway, and granting him, in the meantime, the lands of Dyffryn Clwyd and Cynmeirch.

This agreement was approved by the king on 26 May and improved on 8 July with provision made for Dafydd, pending delivery of the lands, in Hawarden and Shotwick. The final treaty represented the start of a 19-year military and political alliance between Dafydd and the future Edward I.

It would be unreasonable to accuse Dafydd of simply betraying Llywelyn, when the latter was at the height of his success. The well-informed Chester chronicler says that he wished to liberate his brother Owain from prison at Dolbadarn. This may have some truth to it. Certainly, Owain’s confinement only served to rachet up the tensions in Gwynedd, and did nothing for Llywelyn’s popularity among his own people.

Dafydd had chosen to throw in his lot with Edward before the English prince led his army into Gwynedd. This was Edward’s first independent command in Wales. He managed to resupply his beleagured castles at Deganwy (pictured) and Diserth, but the French knights he brought over from the continent were tournament fighters, unsuited for guerilla warfare in North Wales. The Welsh led them in circles before vanishing into the forests and ‘morasses’, while Edward’s allies in the south found it hard going. John Lestrange was almost killed in an ambush at Abermule, Roger Mortimer was severely wounded in a skirmish, and Prince Llywelyn ap Maredudd killed in a battle at Clun.

The fight at Clun, however, was a defeat for Prince Llywelyn, who was engaged in the area south of Montgomery centred on the lordship of John FitzAlan. Possession of this land would extend Llywelyn’s authority to the outer limits of a territory which maintained ‘a community of the Welsh language’. To put Dafydd’s behaviour into context, John FitzAlan shortly afterwards chose to desert the king and join Simon de Montfort. He also struck a deal with Llywelyn, whereby FitzAlan agreed to hand over the lordship of Tempsiter or Dyffryn Tefeidiad to the Welsh prince.

Honestly, you couldn’t trust anyone.

The orders issued from Henry’s chancery reveal the king’s strategy in Wales. Now Llywelyn was dead - apparently - it was vital to secure the homage of Welsh lords, which the crown had claimed for generations. Henry knew exactly how to achieve this: divide their strength and pit them against each other. A show of force was also necessary. The king told Roger Mortimer and the other marchers to dissolve any existing alliances with the Welsh, and be ready to muster at Shrewsbury in September for a full-scale invasion. Meanwhile the king sought confirmation from Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys, whether Llywelyn was alive or dead.

Henry sent one of the marchers, James Audley, to order Gruffudd ap Madog to abandon Prince Dafydd and bring Powys Fadog back into the king’s allegiance. It was absolutely essential that Dafydd should not be acknowledged as Llywelyn’s heir. Technically Henry was correct: Dafydd had no automatic right to inherit, since his brothers Owain and Rhodri were still alive. Yet the king’s newfound love for Welsh custom was all part of his determination to ensure Gwynedd was partitioned in the wake of Llywelyn’s death.

Reports of the prince’s demise were greatly exaggerated. He recovered from his illness, prompting the Brut chronicler to remark that Divine providence afforded its sure protection to the Welsh nation.

As usual, Dafydd chose to follow his own unpredictable course. Despite being unceremoniously ditched by the king in 1262, he remained keen on an English alliance. When the Lord Edward came to the marches in the spring of 1263, Dafydd was sought an early meeting. The two men met at Hereford, where on 3 April Edward issued pardons to Dafydd and his men for waging war against the king. Via the same agreement he promised to: …

assist Dafydd in recovering his reasonable inheritance beyond the Conway, and granting him, in the meantime, the lands of Dyffryn Clwyd and Cynmeirch.

This agreement was approved by the king on 26 May and improved on 8 July with provision made for Dafydd, pending delivery of the lands, in Hawarden and Shotwick. The final treaty represented the start of a 19-year military and political alliance between Dafydd and the future Edward I.

It would be unreasonable to accuse Dafydd of simply betraying Llywelyn, when the latter was at the height of his success. The well-informed Chester chronicler says that he wished to liberate his brother Owain from prison at Dolbadarn. This may have some truth to it. Certainly, Owain’s confinement only served to rachet up the tensions in Gwynedd, and did nothing for Llywelyn’s popularity among his own people.

Dafydd had chosen to throw in his lot with Edward before the English prince led his army into Gwynedd. This was Edward’s first independent command in Wales. He managed to resupply his beleagured castles at Deganwy (pictured) and Diserth, but the French knights he brought over from the continent were tournament fighters, unsuited for guerilla warfare in North Wales. The Welsh led them in circles before vanishing into the forests and ‘morasses’, while Edward’s allies in the south found it hard going. John Lestrange was almost killed in an ambush at Abermule, Roger Mortimer was severely wounded in a skirmish, and Prince Llywelyn ap Maredudd killed in a battle at Clun.

The fight at Clun, however, was a defeat for Prince Llywelyn, who was engaged in the area south of Montgomery centred on the lordship of John FitzAlan. Possession of this land would extend Llywelyn’s authority to the outer limits of a territory which maintained ‘a community of the Welsh language’. To put Dafydd’s behaviour into context, John FitzAlan shortly afterwards chose to desert the king and join Simon de Montfort. He also struck a deal with Llywelyn, whereby FitzAlan agreed to hand over the lordship of Tempsiter or Dyffryn Tefeidiad to the Welsh prince.

Honestly, you couldn’t trust anyone.

Published on October 01, 2019 05:35

September 30, 2019

The tragedy of Dafydd (2)

Henry III’s order to Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and Owain Goch to restore to Dafydd an equal share of his patrimony was a deliberate royal strategy: the king meant to ensure that Gwynedd would be a partitioned state, of no further threat to the English crown. He applied the same principle to Powys Fadog, where the royal council insisted that Gruffudd ap Madog should, according to the custom of Wales, share his land with his co-heirs. It was no coincidence that Gruffudd was Llywelyn’s most loyal ally.

In early 1254 Llywelyn and Dafydd were informed that Henry was sending a commission to hear the disputes between the brothers. The king was subtle: the commission consisted of Alan la Zouche, John Lestrange, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn and Gruffudd ap Madog. By appointing two Welsh lords to the enquiry, Henry could not be accused of anti-Welsh prejudice. His choice of Gruffudd ap Madog as one of the four commissioners was an effort to split the alliance of Gwynedd and Powys Fadog.

The arguments rumbled on. At last it came to civil war, and in June 1255 Llywelyn met his brothers in open battle on the slopes of Bryn Derwin. It seems Owain and Dafydd attacked uphill and were defeated in less than an hour, after which Llywelyn ‘fed lavishly upon their lands without difficulty’.

Owain and Dafydd were both captured. Llywelyn’s ancestors, men such as Gruffydd ap Llywelyn or Owain Gwynedd, would most likely have blinded and castrated the prisoners. Llywelyn chose to imprison Owain at Dolbadarn and give Dafydd another chance. The prince’s merciful attitude did little to resolve the tensions in Gwynedd; a Welsh poet, Hywel Foel ap Griffri, bewailed his personal loss at Owain’s confinement. He was left an exile in his own country, a lordless man, without gifts, without the chief of warriors:

‘Difro wyf heb rwyf, hed roddion/Heb Owain, hebawg cynreinion’.

The very earth was left barren by Owain’s loss: ‘Diffrwythws daear o’i fod yng ngharchar’.

Despite his lucky escape, Dafydd continued to intrigue with the English. On 8 August 1257, as he prepared to invade Gwynedd, King Henry issued an order of safe-conduct for Dafydd to join him at Chester. The document was witnessed by the baronial core of the royal army, including the Lord Edward, on his first expedition into Wales.

Dafydd thought better of it. He declined to come, so the king had the document torn up. After the failure of Henry’s campaign Dafydd chose to stay loyal to his brother for a time, and accompanied Llywelyn on his march south to punish Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg, lord of Ystrad Tywi, who had given his homage to the king.

On 8 September 1258 Dafydd enjoyed perhaps his greatest moment. Wearing ‘his most splendid armour’, he advanced with his cavalry to attack Maredudd and his ally, Patrick Chaworth, at Cilgerran. Shortly after noon the two armies engaged and Dafydd won a splendid victory, killing Chaworth and Walter Malifant, an English knight, and forcing Maredudd to flee into the castle.

In early 1254 Llywelyn and Dafydd were informed that Henry was sending a commission to hear the disputes between the brothers. The king was subtle: the commission consisted of Alan la Zouche, John Lestrange, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn and Gruffudd ap Madog. By appointing two Welsh lords to the enquiry, Henry could not be accused of anti-Welsh prejudice. His choice of Gruffudd ap Madog as one of the four commissioners was an effort to split the alliance of Gwynedd and Powys Fadog.

The arguments rumbled on. At last it came to civil war, and in June 1255 Llywelyn met his brothers in open battle on the slopes of Bryn Derwin. It seems Owain and Dafydd attacked uphill and were defeated in less than an hour, after which Llywelyn ‘fed lavishly upon their lands without difficulty’.

Owain and Dafydd were both captured. Llywelyn’s ancestors, men such as Gruffydd ap Llywelyn or Owain Gwynedd, would most likely have blinded and castrated the prisoners. Llywelyn chose to imprison Owain at Dolbadarn and give Dafydd another chance. The prince’s merciful attitude did little to resolve the tensions in Gwynedd; a Welsh poet, Hywel Foel ap Griffri, bewailed his personal loss at Owain’s confinement. He was left an exile in his own country, a lordless man, without gifts, without the chief of warriors:

‘Difro wyf heb rwyf, hed roddion/Heb Owain, hebawg cynreinion’.

The very earth was left barren by Owain’s loss: ‘Diffrwythws daear o’i fod yng ngharchar’.

Despite his lucky escape, Dafydd continued to intrigue with the English. On 8 August 1257, as he prepared to invade Gwynedd, King Henry issued an order of safe-conduct for Dafydd to join him at Chester. The document was witnessed by the baronial core of the royal army, including the Lord Edward, on his first expedition into Wales.

Dafydd thought better of it. He declined to come, so the king had the document torn up. After the failure of Henry’s campaign Dafydd chose to stay loyal to his brother for a time, and accompanied Llywelyn on his march south to punish Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg, lord of Ystrad Tywi, who had given his homage to the king.

On 8 September 1258 Dafydd enjoyed perhaps his greatest moment. Wearing ‘his most splendid armour’, he advanced with his cavalry to attack Maredudd and his ally, Patrick Chaworth, at Cilgerran. Shortly after noon the two armies engaged and Dafydd won a splendid victory, killing Chaworth and Walter Malifant, an English knight, and forcing Maredudd to flee into the castle.

Published on September 30, 2019 08:53

The tragedy of Prince Dafydd, Part One

We’re coming up to the anniversary of the execution of Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales, on 3 October 1283. To commemorate this unhappy event, let’s have another look at him.

Dafydd was the third of the four sons of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, eldest son of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. He was born in 1238 and in 1241 handed over to the English, along with his younger brother Rhodri, as part of a peace agreement between their uncle, Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn, and Henry III.

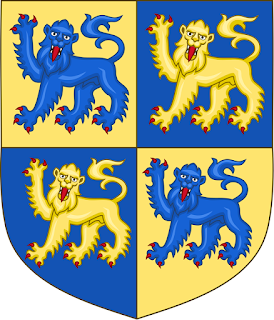

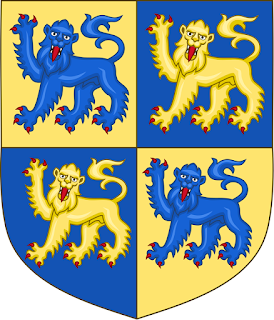

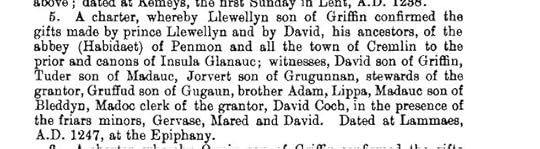

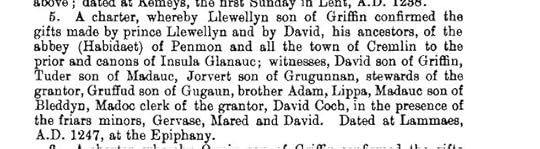

The influence of Dafydd’s upbringing in England has possibly been exaggerated. He clearly spent some time in Wales. In 1247, at just eight years old, he appears as a witness on a charter of his eldest brother, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, which granted land to the priors and canons of Ynys Lannog.

Dafydd next appears in 1252, presiding over a lawsuit in which the canons of the church of Aberdaron resolved a dispute with the Austin canons of Bardsey. Aged about fourteen, Dafydd was already exercising lordship over Cymydmaen, the westerly commote of the cantref of Llŷn.

Despite his earlier association with Llywelyn, it seems that Dafydd owed his lordship in Cymydmaen to the influence of his eldest brother, Owain Goch. The chronicler states that Dafydd was appointed captain of the household (dux familia) in Owain’s service. He therefore occupied the position of penteulu which, according to the custom of his lineage, was reserved for the near kinsman of the ruler.

No comparable grant of land was made over by Llywelyn to Dafydd. This is the first sign of tension between the brothers; by 1253 Dafydd had decided to take steps to gain an appropriate share of his patrimony, and offered his homage and fealty to Henry III. The king agreed to receive him, but had sailed for Gascony by the time Dafydd arrived at Westminster. Even so, he came to an arrangement with the royal council, who ensured that the king would endorse his tenure of whatever part of Gwynedd he acquired for himself.

Owain and Llywelyn, who had divided Gwynedd between them after the death of their uncle, were informed that Dafydd had sworn fealty to the king. This oath was sworn for the portion of lands in Gwynedd which had been held by Gruffudd ap Llywelyn and Dafydd ap Llywelyn. The brothers were thus required to provide him with a due portion ‘according to the custom of Wales’.

Dafydd was the third of the four sons of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, eldest son of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. He was born in 1238 and in 1241 handed over to the English, along with his younger brother Rhodri, as part of a peace agreement between their uncle, Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn, and Henry III.

The influence of Dafydd’s upbringing in England has possibly been exaggerated. He clearly spent some time in Wales. In 1247, at just eight years old, he appears as a witness on a charter of his eldest brother, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, which granted land to the priors and canons of Ynys Lannog.

Dafydd next appears in 1252, presiding over a lawsuit in which the canons of the church of Aberdaron resolved a dispute with the Austin canons of Bardsey. Aged about fourteen, Dafydd was already exercising lordship over Cymydmaen, the westerly commote of the cantref of Llŷn.

Despite his earlier association with Llywelyn, it seems that Dafydd owed his lordship in Cymydmaen to the influence of his eldest brother, Owain Goch. The chronicler states that Dafydd was appointed captain of the household (dux familia) in Owain’s service. He therefore occupied the position of penteulu which, according to the custom of his lineage, was reserved for the near kinsman of the ruler.

No comparable grant of land was made over by Llywelyn to Dafydd. This is the first sign of tension between the brothers; by 1253 Dafydd had decided to take steps to gain an appropriate share of his patrimony, and offered his homage and fealty to Henry III. The king agreed to receive him, but had sailed for Gascony by the time Dafydd arrived at Westminster. Even so, he came to an arrangement with the royal council, who ensured that the king would endorse his tenure of whatever part of Gwynedd he acquired for himself.

Owain and Llywelyn, who had divided Gwynedd between them after the death of their uncle, were informed that Dafydd had sworn fealty to the king. This oath was sworn for the portion of lands in Gwynedd which had been held by Gruffudd ap Llywelyn and Dafydd ap Llywelyn. The brothers were thus required to provide him with a due portion ‘according to the custom of Wales’.

Published on September 30, 2019 04:30

September 29, 2019

March mafia

On 25 January 1290 Edward I issued a proclamation ordering the earls of Gloucester and Hereford to stop waging private war in Brycheiniog. A few days later, 3 February, Clare sent four of his bailiffs ‘with a multitude of horsemen and footmen’ to invade Bohun’s territory, ‘with a banner of the earl’s arms displayed’. They pillaged the land up to two leagues beyond Clare’s new castle at Morlais, built to nail down his control of the territory, killed a number of Bohun’s men and carried off goods.

It seems Clare was attempting to set himself up as a rival potentate in the March. When Edward visited Glamorgan in 1284, the earl had greeted him almost as a fellow monarch. In pure military terms Clare was by far the most powerful of the Marcher lords: he could call upon the service of over 450 knights in England and Wales. His rival Bohun, by contrast, could summon a measly twenty-six.

Clare used his feud against Bohun as a way of striking back against the king, his lifelong rival. A second raid took place on 5 June, shortly after Clare had married Edward’s daughter, Joan of Acre. The terms of the marriage contract required the earl to surrender all his lands into the king’s hands, to be restored after the wedding. Under the terms of the new arrangement, Clare’s lands would pass to the heirs of his wife’s body, not his. Thus, if he died without issue and Joan remarried, all the vast Clare estates in England and Wales would pass to the heirs of her next husband.

Yet another raid took place in November. This was another tit-for-tat act of defiance. On 3 November Clare had conceded the king’s rights to all the revenue from the See of Llandaff; since he had previously snaffled the revenues of the bishopric during vacancy, Clare was judged to have usurped the king’s rights. Edward was tying the earl up in knots (not knights) and Clare’s response was to keep attacking Bohun, in defiance of the king’s prohibition against private war. A head-on collison loomed.

Meanwhile the Marches descended into chaos, and it seems the government struggled to keep track of who was doing what to whom. Tacked onto the end of a severely condensed abstract of the Clare-Bohun case is a mysterious reference to John Giffard, lord of Builth. This tells us that 'item placitum contra Iohannem Giffard et homines suos pro vexillis displicatis apud Gloucestriam' - the same plea against John Giffard and his men with banners displayed near Gloucester. This would imply that Giffard had led his men out of the March to attack Clare’s estates in Gloucestershire, possibly on behalf of Humphrey Bohun. There is no further reference to his actions, so it remains a mystery.

It seems Clare was attempting to set himself up as a rival potentate in the March. When Edward visited Glamorgan in 1284, the earl had greeted him almost as a fellow monarch. In pure military terms Clare was by far the most powerful of the Marcher lords: he could call upon the service of over 450 knights in England and Wales. His rival Bohun, by contrast, could summon a measly twenty-six.

Clare used his feud against Bohun as a way of striking back against the king, his lifelong rival. A second raid took place on 5 June, shortly after Clare had married Edward’s daughter, Joan of Acre. The terms of the marriage contract required the earl to surrender all his lands into the king’s hands, to be restored after the wedding. Under the terms of the new arrangement, Clare’s lands would pass to the heirs of his wife’s body, not his. Thus, if he died without issue and Joan remarried, all the vast Clare estates in England and Wales would pass to the heirs of her next husband.

Yet another raid took place in November. This was another tit-for-tat act of defiance. On 3 November Clare had conceded the king’s rights to all the revenue from the See of Llandaff; since he had previously snaffled the revenues of the bishopric during vacancy, Clare was judged to have usurped the king’s rights. Edward was tying the earl up in knots (not knights) and Clare’s response was to keep attacking Bohun, in defiance of the king’s prohibition against private war. A head-on collison loomed.

Meanwhile the Marches descended into chaos, and it seems the government struggled to keep track of who was doing what to whom. Tacked onto the end of a severely condensed abstract of the Clare-Bohun case is a mysterious reference to John Giffard, lord of Builth. This tells us that 'item placitum contra Iohannem Giffard et homines suos pro vexillis displicatis apud Gloucestriam' - the same plea against John Giffard and his men with banners displayed near Gloucester. This would imply that Giffard had led his men out of the March to attack Clare’s estates in Gloucestershire, possibly on behalf of Humphrey Bohun. There is no further reference to his actions, so it remains a mystery.

Published on September 29, 2019 08:44

September 27, 2019

March Mafia

In 1284 Humphrey Bohun, earl of Hereford, brought a case at law against John Giffard over the land of Isgenen, above the Tywi near Llandeilo. Bohun claimed that he had defeated Rhys Fychan, the Welsh lord of Isgenen, during the war of 1282-3 and ought to have the land. King Edward had granted it to Giffard, who stood high in the king’s favour and was one of his chief enforcers in Wales.

Technically Isgenen had been ‘conquered’ by William Valence and Rhys ap Maredudd, when they led a royal army through the district in the autumn of 1282: the men of the commote had agreed to come into the king’s peace and then immediately enlisted in the army. Valence and Rhys were powerful enough already, and the king chose to grant it to Giffard instead.

Bohun was nervous about the location of Isgenen, which bordered on his own lands. His plea in 1284 failed and Giffard confirmed in the grant. When the war of Rhys ap Maredudd broke out in 1287, the tenants of Isgenen revolted and were put down by Bohun, who could now claim a ‘double right of the sword’ to the commote.

All this kerfuffle was over a minor patch of land: the army payrolls for 1282 contain wages for no more than 60 men of Isgenen, implying a fairly small territory. Yet the honour - or rather the ego - of the Bohuns was at stake, and a disgruntled Marcher knew only one way of resolving disputes. Soon after the defeat of Rhys, Bohun armed his tenants and attacked Giffard’s men of Builth, inflicting ‘homicides, arsons, robberies and other felonies’ agains them.

Technically Isgenen had been ‘conquered’ by William Valence and Rhys ap Maredudd, when they led a royal army through the district in the autumn of 1282: the men of the commote had agreed to come into the king’s peace and then immediately enlisted in the army. Valence and Rhys were powerful enough already, and the king chose to grant it to Giffard instead.

Bohun was nervous about the location of Isgenen, which bordered on his own lands. His plea in 1284 failed and Giffard confirmed in the grant. When the war of Rhys ap Maredudd broke out in 1287, the tenants of Isgenen revolted and were put down by Bohun, who could now claim a ‘double right of the sword’ to the commote.

All this kerfuffle was over a minor patch of land: the army payrolls for 1282 contain wages for no more than 60 men of Isgenen, implying a fairly small territory. Yet the honour - or rather the ego - of the Bohuns was at stake, and a disgruntled Marcher knew only one way of resolving disputes. Soon after the defeat of Rhys, Bohun armed his tenants and attacked Giffard’s men of Builth, inflicting ‘homicides, arsons, robberies and other felonies’ agains them.

Published on September 27, 2019 07:14