Due fidelity

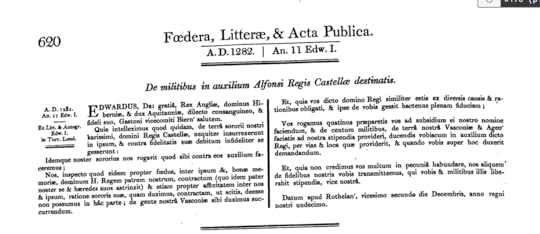

A letter dated 22 December 1282, from Edward I to Gaston Moncada, Viscount of Béarn in southern Gascony. The attached transcript is from a printed collection of diplomatic correspondence called the Foedera; the original is held in the National Archives at Kew.

A letter dated 22 December 1282, from Edward I to Gaston Moncada, Viscount of Béarn in southern Gascony. The attached transcript is from a printed collection of diplomatic correspondence called the Foedera; the original is held in the National Archives at Kew.This letter is used by Kathleen Neal as an example of Edward's delicate treatment of his Gascon subjects. Gaston had frequently rebelled against the king and his father, Henry III, but by 1282 was reconciled. Edward had been asked by his brother-in-law, Alfonso of Castile, to send troops to help him fight a civil war. Occupied with a rebellion in Wales, Edward could not go to Castile himself, or spare English soldiers. His solution was to ask Gaston to go in his name.

This military summons was not expressed as a demand. Instead it was framed as a polite request, in which Gaston was also asked his advice on the situation in Castile. This was not because Edward necessarily wanted his advice, but the aim was to soothe Gaston's touchy sense of pride and honour, and make him feel valued. As Neal puts it:

“Gascon loyalty could not simply be expected or demanded. It had to be argued for, by articulating it as an ideal and a proper course of action, and by specifying the personal consequences of failure”.

By personal consequences, Neal is not referring to punishment, but the potential damage to Gaston's image and reputation if he failed to oblige the king.

The letter opens with a moral evaluation of the war in Castile:

'A certain man, from the land of our dearest brother in law, the lord king of Castile, has risen up against him wickedly, and conducted himself faithlessly against his due fidelity'.

The emphasis on 'wickedness' and bad faith is entirely calculated. Edward follows by articulating his reasons for assisting Alfonso; these include the kinship between the two kings, due to Edward's marriage to Alfonso's half-sister, Eleanor of Castile; the peace between the two kingdoms; and Gaston's personal loyalty towards Alfonso. For good measure, Edward reminded Gaston that he had shown the king of Castile 'full fidelity up to now'; the implication being that he was duty-bound to continue doing so.

Thus, the rhetoric of summons was cast as part of a continuing tradition of loyal service, past and present. Edward was also careful to make use of the highly courteous verbal pairing 'requirimus et rogamus', the highest register of epistolary politeness. This cast the summons in the form of a voluntary act, based on a tradition of service and the promise of further recognition and reward. These cumulative obligations gave Edward the necessary leverage to gain Gaston's service, and send him to Castile at the head of '100 knights of Gascony and Agen'.

They weren't daft, these medieval types.

Published on February 23, 2022 05:33

No comments have been added yet.