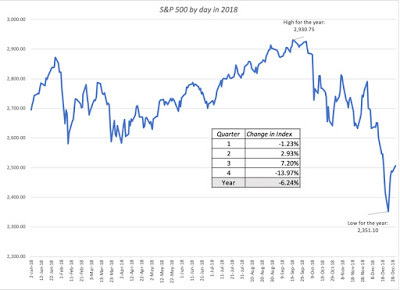

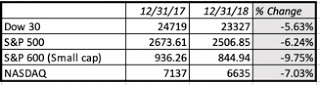

Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 17

January 27, 2019

January 2019 Data Update 6: Profitability and Value Creation!

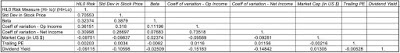

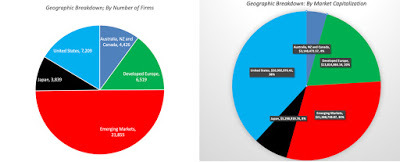

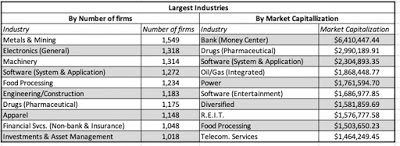

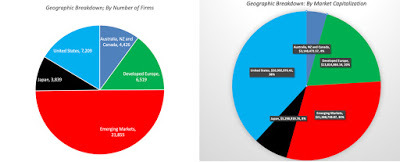

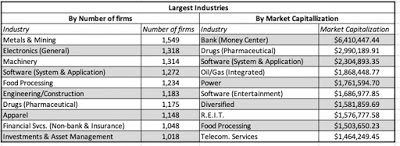

In my last post, I looked at hurdle rates for companies, across industries and across regions, and argued that these hurdle rates represent benchmarks that companies have to beat, to create value. That said, many companies measure success using lower thresholds, with some arguing that making money (having positive profits) is good enough and others positing that being more profitable than competitors in the same business makes you a good company. In this post, I will look at all three measures of success, starting with the minimal (making money), moving on to relative judgments (and how best to compare profitability across companies of different scales) and ending with the most rigorous one of whether the profits are sufficient to create value.

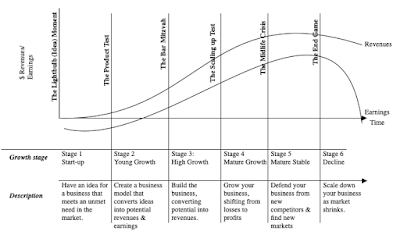

Measuring Financial SuccessYou may start a business with the intent of meeting a customer need or a societal shortfall but your financial success will ultimately determine your longevity. Put bluntly, a socially responsible company with an incredible product may reap good press and have case studies written about it, but if it cannot establish a pathway to profitability, it will not survive. But how do you measure financial success? In this portion of the post, I will start with the simplest measure of financial viability, which is whether the company is making money, usually from an accounting perspective, then move the goal posts to see if the company is more or less profitable than its competitors, and end with the toughest test, which is whether it is generating enough profits on the capital invested in it, to be a value creator.

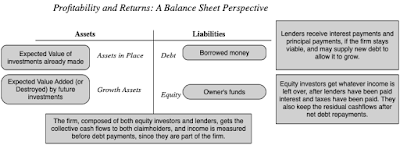

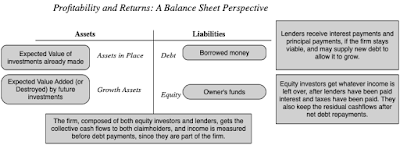

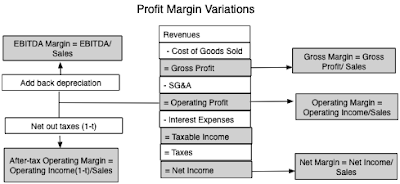

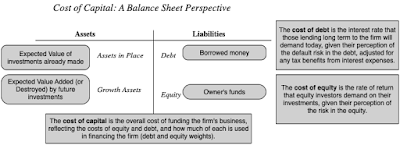

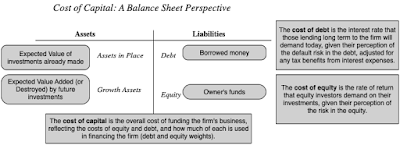

Profit MeasuresBefore I present multiple measures of profitability, it is useful to step back and think about how profits should be measured. I will use the financial balance sheet construct that I used in my last post to explain how you can choose the measure of profitability that is right for your analysis:

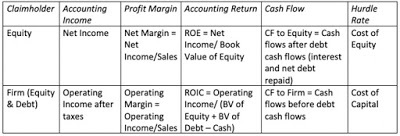

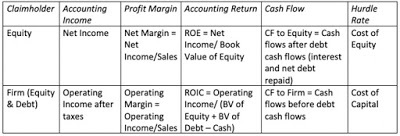

Just as hurdle rates can vary, depending on whether you take the perspective of equity investors (cost of equity) or the entire business (cost of capital), the profit measures that you use will also be different, depending on perspective. If looked at through the eyes of equity investors, profits should be measured after all other claim holders (like debt) and have been paid their dues (interest expenses), whereas using the perspective of the entire firm, profits should be estimated prior to debt payments. In the table below, I have highlighted the various measures of profits and cash flows, depending on claim holder perspective: The key, no matter which claim holder perspective you adopt, is to stay internally consistent. Thus, you can discount cash flows to equity (firm) at the cost of equity (capital) or compare the return on equity (capital) to the cost of equity (capital), but you cannot mix and match.

The key, no matter which claim holder perspective you adopt, is to stay internally consistent. Thus, you can discount cash flows to equity (firm) at the cost of equity (capital) or compare the return on equity (capital) to the cost of equity (capital), but you cannot mix and match.

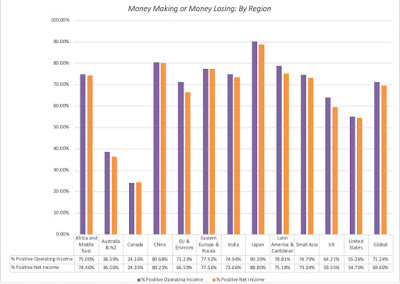

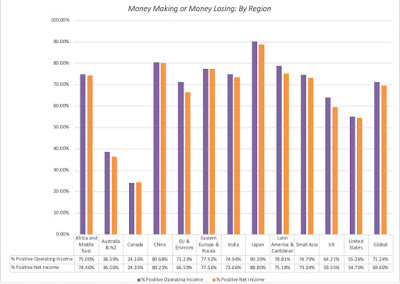

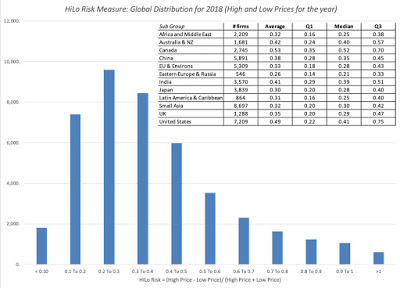

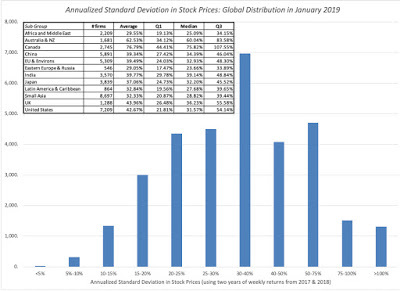

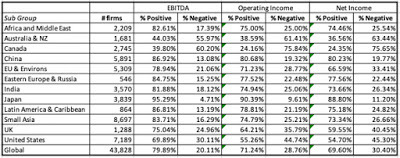

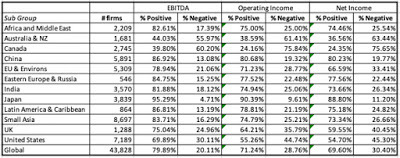

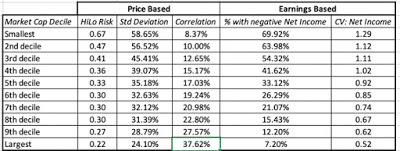

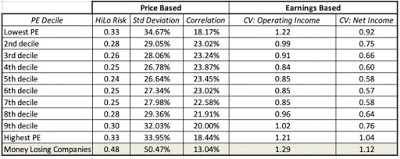

The Minimal Test: Making money?The lowest threshold for success in business is to generate positive profits, perhaps the reason why accountants create measures like breakeven, to determine when that will happen. In my post on measuring risk, I looked at the percentages of firms that meet this threshold on net income (for equity claim holders), an operating income (for all claim holders) and EBITDA (a very rough measure of operating cash flow for all claim holders). Using that statistic for the income over the last twelve month, a significant percentage of publicly traded firms are profitable: Data, by countryThe push back, even on this simplistic measure, is that just as one swallow does not a summer make, one year of profitability is not a measure of continuing profitability. Thus, you could expand this measure to not just look at average income over a longer period (say 5 to 10 years) and even add criteria to measure sustained profitability (number of consecutive profitable years). No matter which approach you use, you still will have two problems. The first is that because this measure is either on (profitable) or off (money losing), it cannot be used to rank or grade firms, once they have become profitable. The other is that making money is only the first step towards establishing viability, since the capital invested in the firm could have been invested elsewhere and made more money. It is absurd to argue that a company with $10 billion in capital invested in it is successful if it generates $100 in profits, since that capital invested even in treasury bills could have generated vastly more money.

Data, by countryThe push back, even on this simplistic measure, is that just as one swallow does not a summer make, one year of profitability is not a measure of continuing profitability. Thus, you could expand this measure to not just look at average income over a longer period (say 5 to 10 years) and even add criteria to measure sustained profitability (number of consecutive profitable years). No matter which approach you use, you still will have two problems. The first is that because this measure is either on (profitable) or off (money losing), it cannot be used to rank or grade firms, once they have become profitable. The other is that making money is only the first step towards establishing viability, since the capital invested in the firm could have been invested elsewhere and made more money. It is absurd to argue that a company with $10 billion in capital invested in it is successful if it generates $100 in profits, since that capital invested even in treasury bills could have generated vastly more money.

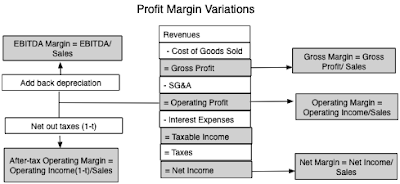

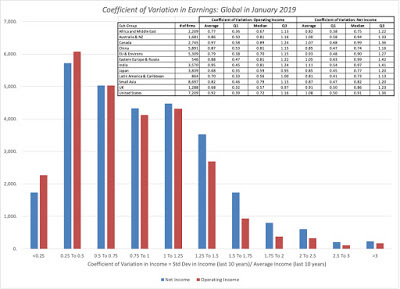

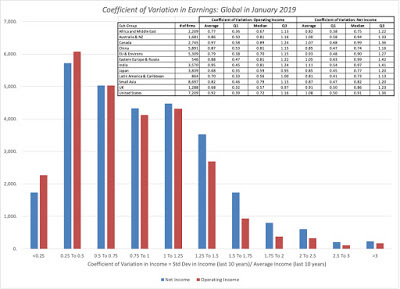

The Relative Test: Scaled ProfitabilityOnce a company starts making money, it is obvious that higher profits are better than lower ones, but unless these profits are scaled to the size of the firm, comparing dollar profits will bias you towards larger firms. The simplest scaling measure is revenues, a data item available for all but financial service firms, and one that is least likely to be affected by accounting choices, and profits scaled to revenues yields profit margins. In a data update post from a year ago, I provided a picture of different margin measures and why they might provide different information about business profitability:

As I noted in my section on claimholders above, you would use net margins to measure profitability to equity investors and operating margins (before or after taxes) to measure profitability to the entire firm. Gross and EBITDA margins are intermediate stops that can be used to assess other aspects of profitability, with gross margins measuring profitability after production costs (but before selling and G&A costs) and EBITDA margins providing a crude measure of operating cash flows.

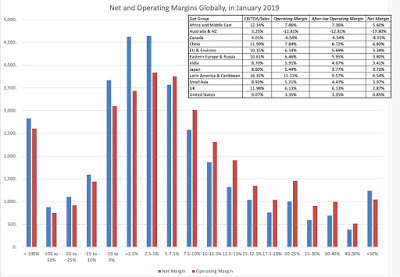

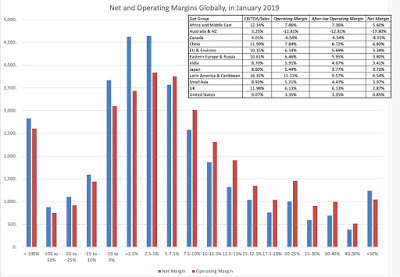

In the graph below, I look at the distribution of pre-tax operating margins and net margins globally, and provide regional medians for the margin measures:

The regional comparisons of margins are difficult to analyze because they reflect the fact that different industries dominate different regions, and margins vary across industries. You can get the different margin measures broken down by industry, in January 2019, for US firms by clicking here. You can download the regional averages using the links at the end of this post.

The Value Test: Beating the Hurdle RateAs a business, making money is easier than creating value, since to create value, you have to not just make money, but more money than you could have if you had invested your capital elsewhere. This innocuous statement lies at the heart of value, and it is in fleshing out the details that we run into practical problems on the three components that go into it:Profits: The profit measures we have for companies reflect their past, not the future, and even the past measures vary over time, and for different proxies for profitability. You could look at net income in the most recent twelve months or average net income over the last ten years, and you could do the same with operating income. Since value is driven by expectations of future profits, it remains an open question whether any of these past measures are good predictors.Invested Capital: You would think that a company would keep a running tab of all the money that is invested in its projects/assets, and in a sense, that is what the book value is supposed to do. However, since this capital gets invested over time, the question of how to adjust capital invested for inflation has remained a thorny one. If you add to that the reality that the invested capital will change as companies take restructuring charges or buy back stock, and that not all capital expenses finds their way on to the balance sheet, the book value of capital may no longer be a good measure of capital invested in existing investments.Opportunity Cost: Since I spent my last post entirely on this question, I will not belabor the estimation challenges that you face in estimating a hurdle rate for a company that is reflective of the risk of its investments.In a perfect world, you would scale your expected cashflows in future years, adjusted for time value of money, to the correct amount of capital invested in the business and compare it to a hurdle rate that reflects both your claim holder choice (equity or the business) but also the risk of the business. In fact, that is exactly what you are trying to do in a good intrinsic or DCF valuation.

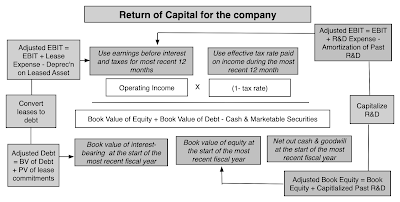

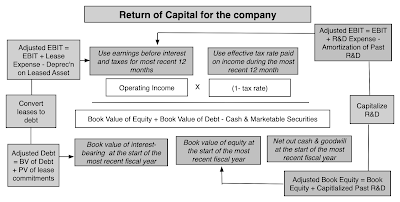

Since it is impossible to do this for 42000 plus companies, on a company-by-company basis, I used blunt instrument measures of each component, measuring profits with last year's operating income after taxes, using book value of capital (book value of debt + book value of equity - cash) as invested capital:

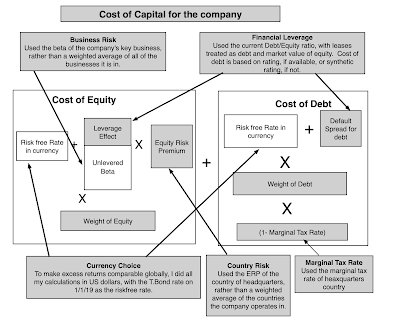

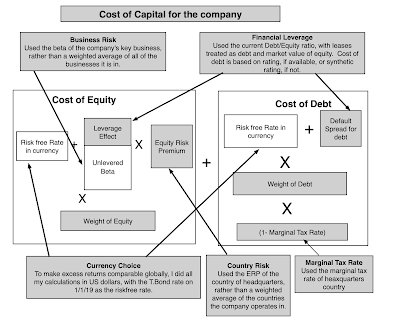

Similarly, to estimate cost of capital, I used short cuts I would not use, if I were called up to analyze a single company:

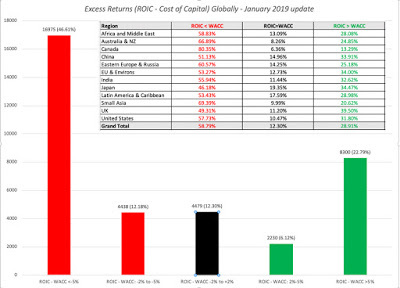

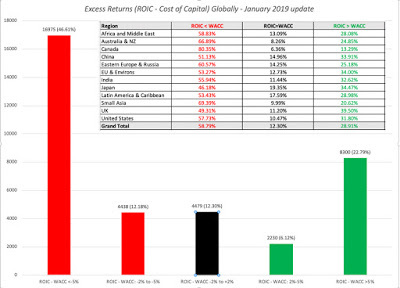

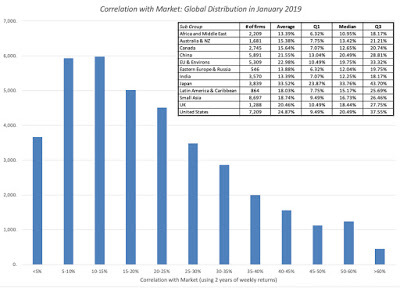

Comparing the return on capital to the cost of capital allows me to estimate excess returns for each of my firms, as the difference between the return on invested capital and the cost of capital. The distribution of this excess return measure globally is in the graph below: I am aware of the limitations of this comparison. First, I am using the trailing twelve month operating income as profits, and it is possible that some of the firms that measure up well and badly just had a really good (bad) year. It is also biased against young and growing firms, where future income will be much higher than the trailing 12-month value. Second, operating income is an accounting measure, and are affected not just by accounting choices, but are also affected by the accounting mis-categorization of lease and R&D expenses. Third, using book value of capital as a proxy for invested capital can be undercut by not only whether accounting capitalizes expenses correctly but also by well motivated attempts by accountants to write off past mistakes (which create charges that lower invested capital and make return on capital look better than it should). In fact, the litany of corrections that have to be made to return on capital to make it usable and listed in this long and very boring paper of mine. Notwithstanding these critiques, the numbers in this graph tell a depressing story, and one that investors should keep in mind, before they fall for the siren song of growth and still more growth that so many corporate management teams sing. Globally, approximately 60% of all firms globally earn less than their cost of capital, about 12% earn roughly their cost of capital and only 28% earn more than their cost of capital. There is no region of the world that is immune from this problem, with value destroyers outnumbering value creators in every region.

I am aware of the limitations of this comparison. First, I am using the trailing twelve month operating income as profits, and it is possible that some of the firms that measure up well and badly just had a really good (bad) year. It is also biased against young and growing firms, where future income will be much higher than the trailing 12-month value. Second, operating income is an accounting measure, and are affected not just by accounting choices, but are also affected by the accounting mis-categorization of lease and R&D expenses. Third, using book value of capital as a proxy for invested capital can be undercut by not only whether accounting capitalizes expenses correctly but also by well motivated attempts by accountants to write off past mistakes (which create charges that lower invested capital and make return on capital look better than it should). In fact, the litany of corrections that have to be made to return on capital to make it usable and listed in this long and very boring paper of mine. Notwithstanding these critiques, the numbers in this graph tell a depressing story, and one that investors should keep in mind, before they fall for the siren song of growth and still more growth that so many corporate management teams sing. Globally, approximately 60% of all firms globally earn less than their cost of capital, about 12% earn roughly their cost of capital and only 28% earn more than their cost of capital. There is no region of the world that is immune from this problem, with value destroyers outnumbering value creators in every region.

ImplicationsFrom a corporate finance perspective, there are lessons to be learned from the cross section of excess returns, and here are two immediate ones:Growth is a mixed blessing: In 60% of companies, it looks like it destroys value, does not add to it. While that proportion may be inflated by the presence of bad years or companies that are early in the life cycle, I am sure that the proportion of companies where value is being destroyed, when new investments are made, is higher than those where value is created.Value destruction is more the rule than the exception: There are lots of bad companies, if bad is defined as not making your hurdle rate. In some companies, it can be attributed to bad managed that is entrenched and set in its ways. In others, it is because the businesses these companies are in have become bad business, where no matter what management tries, it will be impossible to eke out excess returns.You can see the variations in excess returns across industries, for US companies, by clicking on this link, but there are clearly lots of bad businesses to be in. The same data is available for other regions in the datasets that are linked at the end of this post.

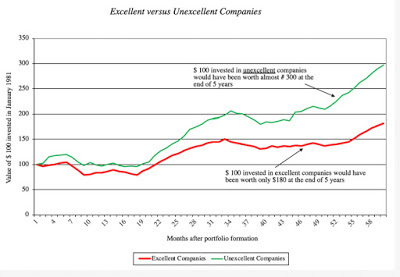

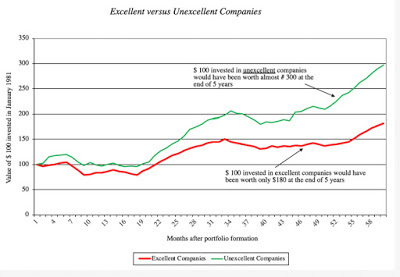

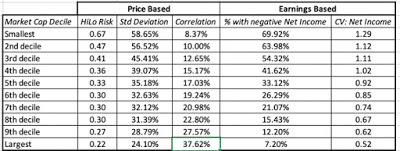

If there is a consolation prize for investors in this graph, it is that the returns you make on your investment in a company are driven by a different dynamic. If stocks are value driven, the stock price for a company will reflect its investment choices, and companies that invest their money badly will be priced lower than companies that invest their money well. The returns you will make on these companies, though, will depend upon whether the excess returns that they deliver in the future are greater or lower than expectations. Thus, a company that earns a return on capital of 5%, much lower than its cost of capital of 10%, which is priced to continue earning the same return will see if its stock price increase, if it can improve its return on capital to 7%, still lower than the cost of capital, but higher than expected. By the same token, a company that earns a return on capital of 25%, well above its cost of capital of 10%, and priced on the assumption that it can continue on its value generating path, will see its stock price drop, if the returns it generates on capital drop to 20%, well above the cost of capital, but still below expectations. That may explain a graph like the following, where researchers found that investing in bad (unexcellent) companies generated far better returns than investing in good (excellent) companies: Original Paper: Excellence Revisited, by Michelle KlaymanThe paper is dated, but its results are not, and they have been reproduced using other categorizations for good and bad firms. Thus, investing in the most admired firms generates worse returns for investors than investing in the least admired and investing in popular (with investors) firms under performs investing in unpopular ones. While these results may seem perverse, at first sight, that bad (good) companies can be good (bad) investments, it makes sense, once you factor in the expectations game.

Original Paper: Excellence Revisited, by Michelle KlaymanThe paper is dated, but its results are not, and they have been reproduced using other categorizations for good and bad firms. Thus, investing in the most admired firms generates worse returns for investors than investing in the least admired and investing in popular (with investors) firms under performs investing in unpopular ones. While these results may seem perverse, at first sight, that bad (good) companies can be good (bad) investments, it makes sense, once you factor in the expectations game.

Finally, on the corporate governance front, I feel that we have lost our way. Corporate governance laws and measures have focused on check boxes on director independence and corporate rules, rather than furthering the end game of better managed companies. From my perspective, corporate governance should give stockholders a chance to change the way companies are run, and if corporate governance works well, you should see more management turnover at companies that don't earn what they need to on capital. The fact that six in ten companies across the globe earned well below their cost of capital in 2018, added to the reality that many of these companies have not only been under performing for years, but are still run by the same management, makes me wonder whether the push towards better corporate governance is more talk than action.

YouTube Video

Data Links

Profit Margins: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India, China, Aus & CanadaExcess Returns to Equity and Capital: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India, China, Aus & CanadaPapers

Return on Capital, Return on Invested Capital and Return on Equity: Measurement and Implications (Warning: It is long and boring!) Related PostsExplaining a Paradox: Why good companies can be bad investments and vice versa

January 2019 Data UpdatesData Update 1: A Reminder that equities are risky, in case you forgot!Data Update 2: The Message from Bond MarketsData Update 3: Playing the Numbers GameData Update 4: The Many Faces of RiskData Update 5: Of Hurdle Rates and Funding Costs!Data Update 6: Profitability and Value Creation!

Measuring Financial SuccessYou may start a business with the intent of meeting a customer need or a societal shortfall but your financial success will ultimately determine your longevity. Put bluntly, a socially responsible company with an incredible product may reap good press and have case studies written about it, but if it cannot establish a pathway to profitability, it will not survive. But how do you measure financial success? In this portion of the post, I will start with the simplest measure of financial viability, which is whether the company is making money, usually from an accounting perspective, then move the goal posts to see if the company is more or less profitable than its competitors, and end with the toughest test, which is whether it is generating enough profits on the capital invested in it, to be a value creator.

Profit MeasuresBefore I present multiple measures of profitability, it is useful to step back and think about how profits should be measured. I will use the financial balance sheet construct that I used in my last post to explain how you can choose the measure of profitability that is right for your analysis:

Just as hurdle rates can vary, depending on whether you take the perspective of equity investors (cost of equity) or the entire business (cost of capital), the profit measures that you use will also be different, depending on perspective. If looked at through the eyes of equity investors, profits should be measured after all other claim holders (like debt) and have been paid their dues (interest expenses), whereas using the perspective of the entire firm, profits should be estimated prior to debt payments. In the table below, I have highlighted the various measures of profits and cash flows, depending on claim holder perspective:

The key, no matter which claim holder perspective you adopt, is to stay internally consistent. Thus, you can discount cash flows to equity (firm) at the cost of equity (capital) or compare the return on equity (capital) to the cost of equity (capital), but you cannot mix and match.

The key, no matter which claim holder perspective you adopt, is to stay internally consistent. Thus, you can discount cash flows to equity (firm) at the cost of equity (capital) or compare the return on equity (capital) to the cost of equity (capital), but you cannot mix and match.The Minimal Test: Making money?The lowest threshold for success in business is to generate positive profits, perhaps the reason why accountants create measures like breakeven, to determine when that will happen. In my post on measuring risk, I looked at the percentages of firms that meet this threshold on net income (for equity claim holders), an operating income (for all claim holders) and EBITDA (a very rough measure of operating cash flow for all claim holders). Using that statistic for the income over the last twelve month, a significant percentage of publicly traded firms are profitable:

Data, by countryThe push back, even on this simplistic measure, is that just as one swallow does not a summer make, one year of profitability is not a measure of continuing profitability. Thus, you could expand this measure to not just look at average income over a longer period (say 5 to 10 years) and even add criteria to measure sustained profitability (number of consecutive profitable years). No matter which approach you use, you still will have two problems. The first is that because this measure is either on (profitable) or off (money losing), it cannot be used to rank or grade firms, once they have become profitable. The other is that making money is only the first step towards establishing viability, since the capital invested in the firm could have been invested elsewhere and made more money. It is absurd to argue that a company with $10 billion in capital invested in it is successful if it generates $100 in profits, since that capital invested even in treasury bills could have generated vastly more money.

Data, by countryThe push back, even on this simplistic measure, is that just as one swallow does not a summer make, one year of profitability is not a measure of continuing profitability. Thus, you could expand this measure to not just look at average income over a longer period (say 5 to 10 years) and even add criteria to measure sustained profitability (number of consecutive profitable years). No matter which approach you use, you still will have two problems. The first is that because this measure is either on (profitable) or off (money losing), it cannot be used to rank or grade firms, once they have become profitable. The other is that making money is only the first step towards establishing viability, since the capital invested in the firm could have been invested elsewhere and made more money. It is absurd to argue that a company with $10 billion in capital invested in it is successful if it generates $100 in profits, since that capital invested even in treasury bills could have generated vastly more money.The Relative Test: Scaled ProfitabilityOnce a company starts making money, it is obvious that higher profits are better than lower ones, but unless these profits are scaled to the size of the firm, comparing dollar profits will bias you towards larger firms. The simplest scaling measure is revenues, a data item available for all but financial service firms, and one that is least likely to be affected by accounting choices, and profits scaled to revenues yields profit margins. In a data update post from a year ago, I provided a picture of different margin measures and why they might provide different information about business profitability:

As I noted in my section on claimholders above, you would use net margins to measure profitability to equity investors and operating margins (before or after taxes) to measure profitability to the entire firm. Gross and EBITDA margins are intermediate stops that can be used to assess other aspects of profitability, with gross margins measuring profitability after production costs (but before selling and G&A costs) and EBITDA margins providing a crude measure of operating cash flows.

In the graph below, I look at the distribution of pre-tax operating margins and net margins globally, and provide regional medians for the margin measures:

The regional comparisons of margins are difficult to analyze because they reflect the fact that different industries dominate different regions, and margins vary across industries. You can get the different margin measures broken down by industry, in January 2019, for US firms by clicking here. You can download the regional averages using the links at the end of this post.

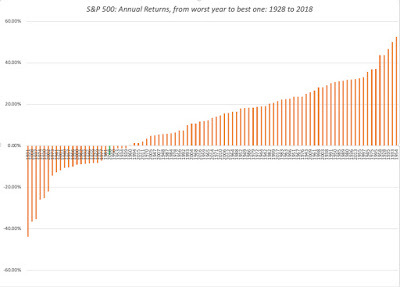

The Value Test: Beating the Hurdle RateAs a business, making money is easier than creating value, since to create value, you have to not just make money, but more money than you could have if you had invested your capital elsewhere. This innocuous statement lies at the heart of value, and it is in fleshing out the details that we run into practical problems on the three components that go into it:Profits: The profit measures we have for companies reflect their past, not the future, and even the past measures vary over time, and for different proxies for profitability. You could look at net income in the most recent twelve months or average net income over the last ten years, and you could do the same with operating income. Since value is driven by expectations of future profits, it remains an open question whether any of these past measures are good predictors.Invested Capital: You would think that a company would keep a running tab of all the money that is invested in its projects/assets, and in a sense, that is what the book value is supposed to do. However, since this capital gets invested over time, the question of how to adjust capital invested for inflation has remained a thorny one. If you add to that the reality that the invested capital will change as companies take restructuring charges or buy back stock, and that not all capital expenses finds their way on to the balance sheet, the book value of capital may no longer be a good measure of capital invested in existing investments.Opportunity Cost: Since I spent my last post entirely on this question, I will not belabor the estimation challenges that you face in estimating a hurdle rate for a company that is reflective of the risk of its investments.In a perfect world, you would scale your expected cashflows in future years, adjusted for time value of money, to the correct amount of capital invested in the business and compare it to a hurdle rate that reflects both your claim holder choice (equity or the business) but also the risk of the business. In fact, that is exactly what you are trying to do in a good intrinsic or DCF valuation.

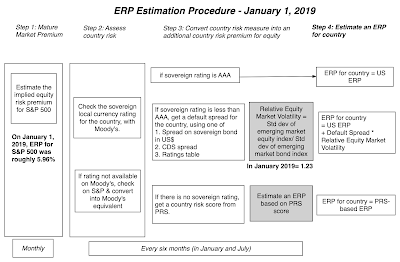

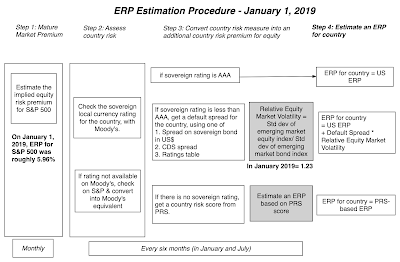

Since it is impossible to do this for 42000 plus companies, on a company-by-company basis, I used blunt instrument measures of each component, measuring profits with last year's operating income after taxes, using book value of capital (book value of debt + book value of equity - cash) as invested capital:

Similarly, to estimate cost of capital, I used short cuts I would not use, if I were called up to analyze a single company:

Comparing the return on capital to the cost of capital allows me to estimate excess returns for each of my firms, as the difference between the return on invested capital and the cost of capital. The distribution of this excess return measure globally is in the graph below:

I am aware of the limitations of this comparison. First, I am using the trailing twelve month operating income as profits, and it is possible that some of the firms that measure up well and badly just had a really good (bad) year. It is also biased against young and growing firms, where future income will be much higher than the trailing 12-month value. Second, operating income is an accounting measure, and are affected not just by accounting choices, but are also affected by the accounting mis-categorization of lease and R&D expenses. Third, using book value of capital as a proxy for invested capital can be undercut by not only whether accounting capitalizes expenses correctly but also by well motivated attempts by accountants to write off past mistakes (which create charges that lower invested capital and make return on capital look better than it should). In fact, the litany of corrections that have to be made to return on capital to make it usable and listed in this long and very boring paper of mine. Notwithstanding these critiques, the numbers in this graph tell a depressing story, and one that investors should keep in mind, before they fall for the siren song of growth and still more growth that so many corporate management teams sing. Globally, approximately 60% of all firms globally earn less than their cost of capital, about 12% earn roughly their cost of capital and only 28% earn more than their cost of capital. There is no region of the world that is immune from this problem, with value destroyers outnumbering value creators in every region.

I am aware of the limitations of this comparison. First, I am using the trailing twelve month operating income as profits, and it is possible that some of the firms that measure up well and badly just had a really good (bad) year. It is also biased against young and growing firms, where future income will be much higher than the trailing 12-month value. Second, operating income is an accounting measure, and are affected not just by accounting choices, but are also affected by the accounting mis-categorization of lease and R&D expenses. Third, using book value of capital as a proxy for invested capital can be undercut by not only whether accounting capitalizes expenses correctly but also by well motivated attempts by accountants to write off past mistakes (which create charges that lower invested capital and make return on capital look better than it should). In fact, the litany of corrections that have to be made to return on capital to make it usable and listed in this long and very boring paper of mine. Notwithstanding these critiques, the numbers in this graph tell a depressing story, and one that investors should keep in mind, before they fall for the siren song of growth and still more growth that so many corporate management teams sing. Globally, approximately 60% of all firms globally earn less than their cost of capital, about 12% earn roughly their cost of capital and only 28% earn more than their cost of capital. There is no region of the world that is immune from this problem, with value destroyers outnumbering value creators in every region.ImplicationsFrom a corporate finance perspective, there are lessons to be learned from the cross section of excess returns, and here are two immediate ones:Growth is a mixed blessing: In 60% of companies, it looks like it destroys value, does not add to it. While that proportion may be inflated by the presence of bad years or companies that are early in the life cycle, I am sure that the proportion of companies where value is being destroyed, when new investments are made, is higher than those where value is created.Value destruction is more the rule than the exception: There are lots of bad companies, if bad is defined as not making your hurdle rate. In some companies, it can be attributed to bad managed that is entrenched and set in its ways. In others, it is because the businesses these companies are in have become bad business, where no matter what management tries, it will be impossible to eke out excess returns.You can see the variations in excess returns across industries, for US companies, by clicking on this link, but there are clearly lots of bad businesses to be in. The same data is available for other regions in the datasets that are linked at the end of this post.

If there is a consolation prize for investors in this graph, it is that the returns you make on your investment in a company are driven by a different dynamic. If stocks are value driven, the stock price for a company will reflect its investment choices, and companies that invest their money badly will be priced lower than companies that invest their money well. The returns you will make on these companies, though, will depend upon whether the excess returns that they deliver in the future are greater or lower than expectations. Thus, a company that earns a return on capital of 5%, much lower than its cost of capital of 10%, which is priced to continue earning the same return will see if its stock price increase, if it can improve its return on capital to 7%, still lower than the cost of capital, but higher than expected. By the same token, a company that earns a return on capital of 25%, well above its cost of capital of 10%, and priced on the assumption that it can continue on its value generating path, will see its stock price drop, if the returns it generates on capital drop to 20%, well above the cost of capital, but still below expectations. That may explain a graph like the following, where researchers found that investing in bad (unexcellent) companies generated far better returns than investing in good (excellent) companies:

Original Paper: Excellence Revisited, by Michelle KlaymanThe paper is dated, but its results are not, and they have been reproduced using other categorizations for good and bad firms. Thus, investing in the most admired firms generates worse returns for investors than investing in the least admired and investing in popular (with investors) firms under performs investing in unpopular ones. While these results may seem perverse, at first sight, that bad (good) companies can be good (bad) investments, it makes sense, once you factor in the expectations game.

Original Paper: Excellence Revisited, by Michelle KlaymanThe paper is dated, but its results are not, and they have been reproduced using other categorizations for good and bad firms. Thus, investing in the most admired firms generates worse returns for investors than investing in the least admired and investing in popular (with investors) firms under performs investing in unpopular ones. While these results may seem perverse, at first sight, that bad (good) companies can be good (bad) investments, it makes sense, once you factor in the expectations game. Finally, on the corporate governance front, I feel that we have lost our way. Corporate governance laws and measures have focused on check boxes on director independence and corporate rules, rather than furthering the end game of better managed companies. From my perspective, corporate governance should give stockholders a chance to change the way companies are run, and if corporate governance works well, you should see more management turnover at companies that don't earn what they need to on capital. The fact that six in ten companies across the globe earned well below their cost of capital in 2018, added to the reality that many of these companies have not only been under performing for years, but are still run by the same management, makes me wonder whether the push towards better corporate governance is more talk than action.

YouTube Video

Data Links

Profit Margins: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India, China, Aus & CanadaExcess Returns to Equity and Capital: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India, China, Aus & CanadaPapers

Return on Capital, Return on Invested Capital and Return on Equity: Measurement and Implications (Warning: It is long and boring!) Related PostsExplaining a Paradox: Why good companies can be bad investments and vice versa

January 2019 Data UpdatesData Update 1: A Reminder that equities are risky, in case you forgot!Data Update 2: The Message from Bond MarketsData Update 3: Playing the Numbers GameData Update 4: The Many Faces of RiskData Update 5: Of Hurdle Rates and Funding Costs!Data Update 6: Profitability and Value Creation!

Published on January 27, 2019 15:03

January 24, 2019

January 2019 Data Update 5: Hurdle Rates and Costs of Financing

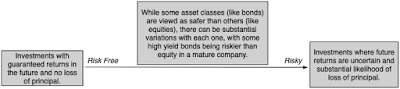

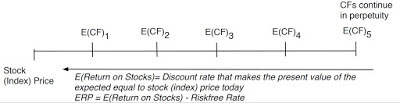

In the last post, I looked at how to measure risk from different perspectives, with the intent of bringing these risk measures into both corporate finance and valuation. In this post, I will close the circle by converting risk measures into hurdle rates, critical in corporate finance, since they drive whether companies should invest or not, and in valuation, because they determine the values of businesses. As with my other data posts, the focus will remain on what these hurdle rates look like for companies around the world at the start of 2019.

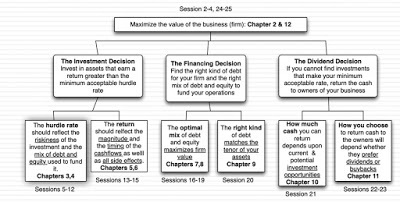

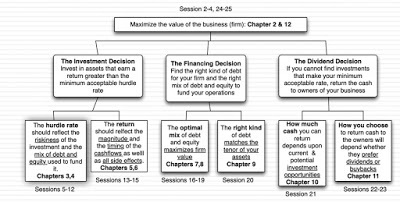

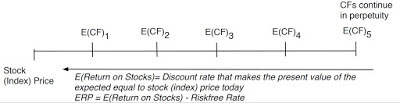

A Quick Introduction

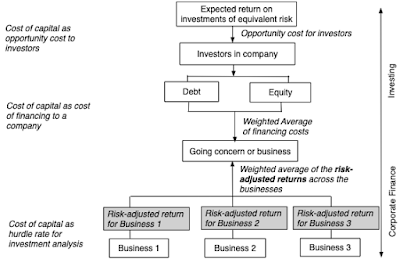

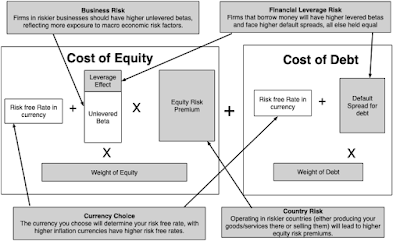

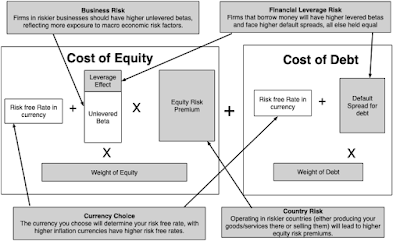

The simplest way to introduce hurdle rates is to look at them from the perspectives of the capital providers to a business. Using a financial balance sheet as my construct, here is a big picture view of these costs:

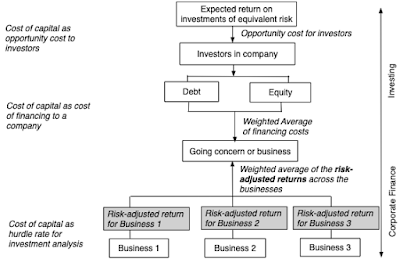

Thus. the hurdle rate for equity investors, i.e., the cost of equity, is the rate that they need to make, to break even, given the risk that they perceive in their equity investments. Lenders, on the other hand, incorporate their concerns about default risk into the interest rates they set on leans, i.e., the cost of debt. From the perspective of a business that raises funds from both equity investors and lenders, it is a weighted average of what equity investors need to make and what lenders demand as interest rates on borrowing, that represents the overall cost of funding, i.e., the cost of capital.

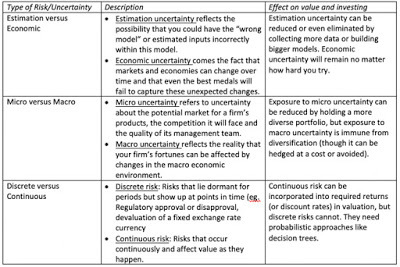

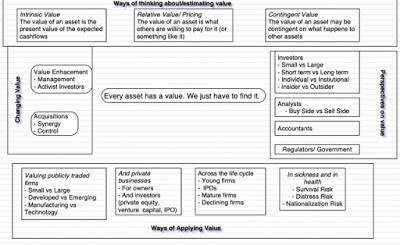

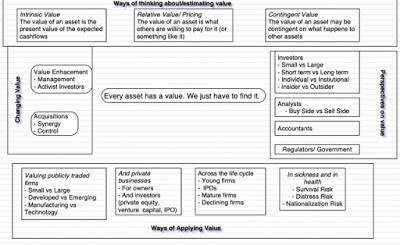

I have described the cost of capital as the Swiss Army Knife of finance, used in many different contexts and with very different meanings. I have reproduced below the different uses in a picture: Paper on cost of capitalIt is precisely because the cost of capital is used in so many different places that it is also one of the most misunderstood and misused numbers in finance. The best way to reconcile the different perspectives is to remember that the cost of capital is ultimately determined by the risk of the enterprise raising the funding, and that all of the many risks that a firm faces have to find their way into it. I have always found it easiest to break the cost of capital into parts, and let each part convey a specific risk, since if I am careless, I end up missing or double counting risk. In this post, I will break the risks that a company faces into four groups: the business or businesses the company operates in (business risk), the geographies that it operates in (country risk), how much it has chosen to borrow (financial leverage risk) and the currencies its cash flows are in (currency effects).

Paper on cost of capitalIt is precisely because the cost of capital is used in so many different places that it is also one of the most misunderstood and misused numbers in finance. The best way to reconcile the different perspectives is to remember that the cost of capital is ultimately determined by the risk of the enterprise raising the funding, and that all of the many risks that a firm faces have to find their way into it. I have always found it easiest to break the cost of capital into parts, and let each part convey a specific risk, since if I am careless, I end up missing or double counting risk. In this post, I will break the risks that a company faces into four groups: the business or businesses the company operates in (business risk), the geographies that it operates in (country risk), how much it has chosen to borrow (financial leverage risk) and the currencies its cash flows are in (currency effects).

Note that each part of the cost of capital has a key risk embedded in it. Thus, when valuing a company, in US dollars, in a safe business in a risky country, with very little financial leverage, you will see the 10-year US treasury bond rate as my risk free rate, a low beta (reflecting the safety of the business and low debt), but a high equity risk premium (reflecting the risk of the country). The rest of this post will look at each of the outlined risks.

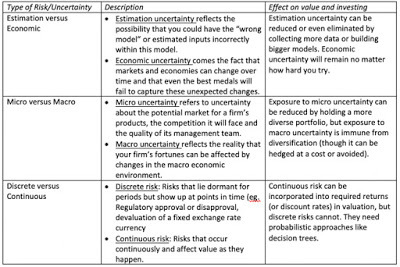

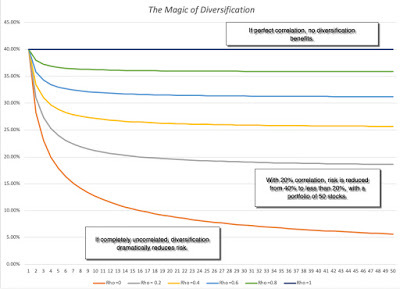

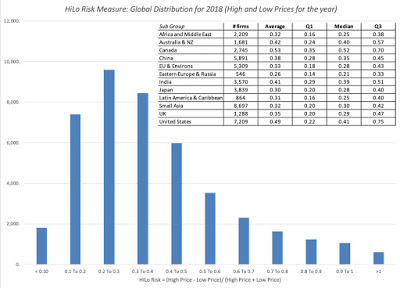

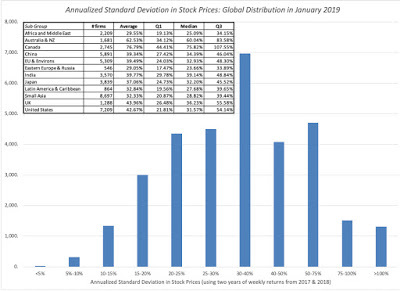

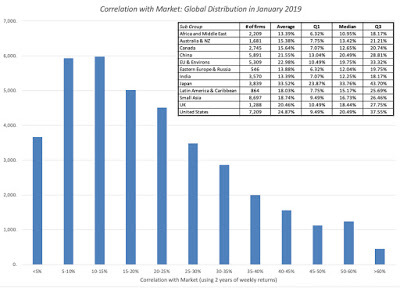

I. Business Risk

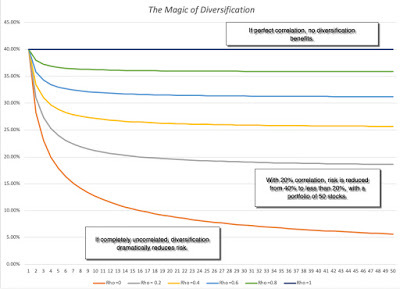

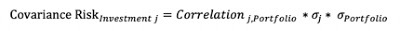

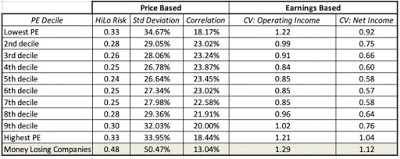

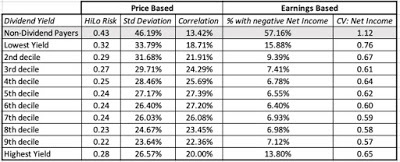

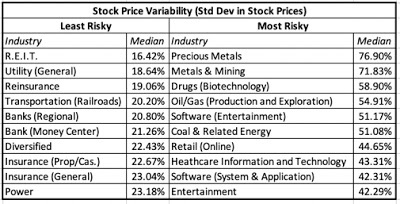

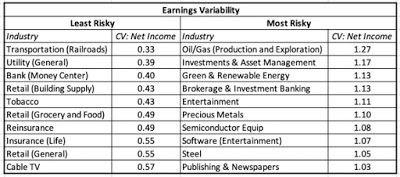

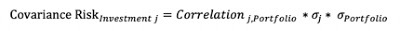

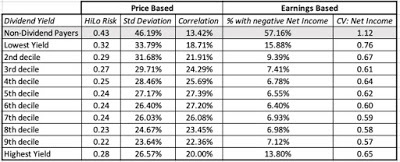

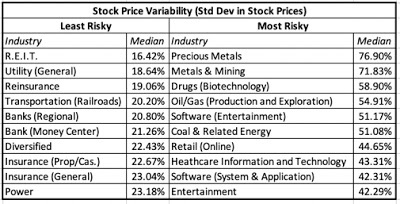

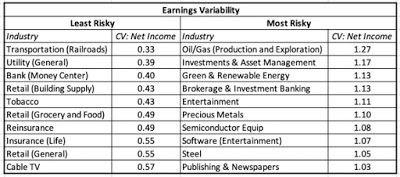

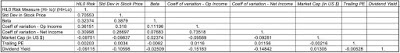

In my last post, where I updated risk measures across the world, I also looked at how these measures varied across different industries/businesses. In particular, I highlighted the ten most risky and safest industries, based upon both price variability and earnings variability, and noted the overlap between the two measures. I also looked at how the perceived risk in a business can change, depending upon investor diversification, and captured this effect with the correlation with the overall market. If you are diversified, I argued that you would measure the risk in an investment with the covariance of that investment with the market, or in its standardized form, its beta.

To get the beta for a company, then, you can adopt one of two approaches.

The first, and the one that is taught in every finance class, is to run a regression of returns on the stock against a market index and to use the regression beta. The second, and my preferred approach, is to estimate a beta by looking at the business or businesses a company operates in, and taking a weighted average of the betas of companies in that business. To use the second approach, you need betas by business, and each year, I estimate these numbers by averaging the betas of publicly traded companies in each business. These betas, in addition to reflecting the risk of the business, also reflect the financial leverage of companies in that business (with more debt pushing up betas) and their holdings in cash and marketable securities (which, being close to risk less, push down betas). Consequently, I adjust the average beta for both variables to estimate what is called a pure play or a business beta for each business. (Rather than bore you with the mechanics, please watch this video on how I make these adjustments). The resulting estimates are shown at this link, for US companies. (You can also download the spreadsheets that contain the estimates for other parts of the world, as well as global averages, by going to the end of this post).

To get from these business betas to the beta of a company, you need to first identify what businesses the company operates in, and then how much value it derives from each of the businesses. The first part is usually simple to do, though you may face the challenge of finding the right bucket to put a business into, but the second part is usually difficult, because the individual businesses do not trade. You can use revenues or operating income by business as approximations to estimate weights or apply multiples to each of these variables (by looking at what other companies in the business trade at) to arrive at value weights.

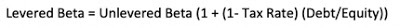

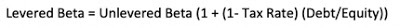

II. Financial LeverageYou can run a company, without ever using debt financing, or you can choose to borrow money to finance operations. In some cases, your lack of access to new equity may force you to borrow money and, in others, you may borrow money because you believe it will lower your cost of capital. In general, the choice of whether you use debt or equity remains one of the key parts of corporate finance, and I will discuss it in one of my upcoming data posts. In this post, though, I will just posit that your cost of capital can be affected by how much you borrow, unless you live in a world where there are no taxes, default risk or agency problems, in which case your cost of capital will remain unchanged as your funding mix changes. If you do borrow money to fund some or a significant portion of your operations, there are three numbers that you need to estimate for your cost of capital:

Debt Ratio: Th mix of debt and equity that you use represents the weights in your cost of capital.Beta Effect: As you borrow money, your equity will become riskier, because it is a residual claim, and having more interest expenses will make that claim more volatile. If you use beta as your measure of risk, this will require you to adjust upwards the business (or unlettered) beta that you obtained in the last part, using the debt to equity ratio of the company. Cost of Debt: The cost of debt, which is set by lenders based upon how much default risk that they see in a company, will enter the cost of capital equation, with an added twist. To the extent that the tax law is tilted towards debt, the after-tax cost of borrowing will reflect that tax benefit. Since this cost of debt is a cost of borrowing money, long term and today, you cannot use a book interest rate or the interest rate on existing debt. Instead, you have to estimate a default spread for the company, based upon either its bond ratings or financial ratios, and add that spread on to the risk free rate:

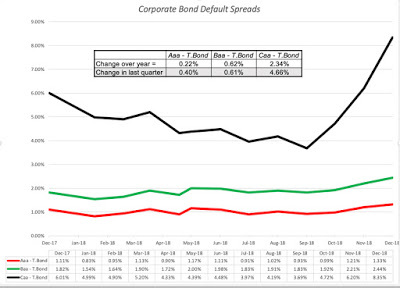

Cost of Debt: The cost of debt, which is set by lenders based upon how much default risk that they see in a company, will enter the cost of capital equation, with an added twist. To the extent that the tax law is tilted towards debt, the after-tax cost of borrowing will reflect that tax benefit. Since this cost of debt is a cost of borrowing money, long term and today, you cannot use a book interest rate or the interest rate on existing debt. Instead, you have to estimate a default spread for the company, based upon either its bond ratings or financial ratios, and add that spread on to the risk free rate:

I look at the debt effect on the cost of capital in each of the industries that I follow, with all three effects incorporated in this link, for US companies. The data, broken down, by other regional sub-groupings is available at the end of this post.

I look at the debt effect on the cost of capital in each of the industries that I follow, with all three effects incorporated in this link, for US companies. The data, broken down, by other regional sub-groupings is available at the end of this post.

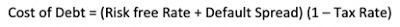

III. Country Risk

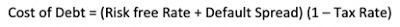

It strikes me as common sense that operating in some countries will expose you to more risk than operating in others, and that the cost of capital (hurdle rate) you use should reflect that additional risk. While there are some who are resistant to this proposition, making the argument that country risk can be diversified by having a global portfolio, that argument is undercut by rising correlations across markets. Consequently, the question becomes not whether you should incorporate country risk, but how best to do it. There are three broad choices:

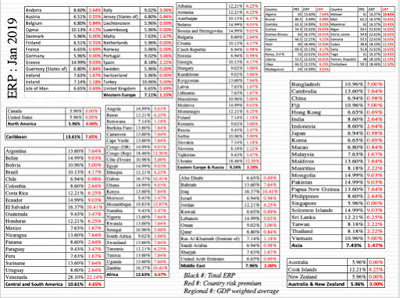

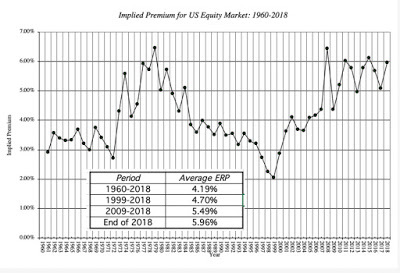

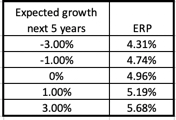

Sovereign Ratings and Default Spreads: The vast majority of countries have sovereign ratings, measuring their default risk, and since these ratings go with default spreads, there are many who use these default spreads as measures of country risk. Sovereign CDS spreads: The Credit Default Swap (CDS) market is one where you can buy insurance against sovereign default, and it offers a market-based estimate of sovereign risk. While the coverage is less than what you get from sovereign ratings, the number of countries where you can obtain these spreads has increased over time to reach 71 in 2019. Country Risk Premiums: I start with the default spreads, but I add a scaling factor to reflect the reality that equities are riskier than government bonds to come up with country risk premiums. The scaling factor that I use is obtained by dividing the volatility of an emerging market equity index by the volatility of emerging market bonds. To incorporate the country risk into my cost of capital calculations, I start with the implied equity risk premium that I estimated for the US (see my first data post for 2019) or 5.96% and add to it the country risk premium for each country. The full adjustment process is described in this picture:

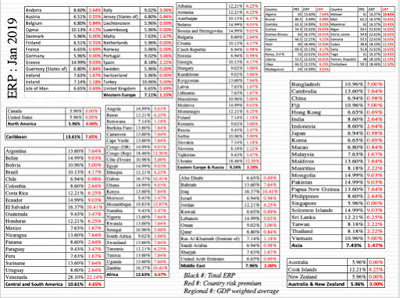

I also bring in frontier markets, which have no sovereign ratings, using a country risk score estimated by Political Risk Services. The final estimates of equity risk premiums around the world can be seen in the picture below:

You can see these equity risk premiums as a list by clicking here, or download the entire spreadsheet here. If you prefer a picture of equity risk around the world, my map is below:

Download spreadsheetI also report regional equity risk premiums, computed by taking GDP-weighted averages of the equity risk premiums of the countries int he region.

Download spreadsheetI also report regional equity risk premiums, computed by taking GDP-weighted averages of the equity risk premiums of the countries int he region.

IV. Currency Risk

It is natural to mix up countries and currencies, when you do your analysis, because the countries with the most risk often have the most volatile currencies. That said, my suggestion is that you keep it simple, when it comes to currencies, recognizing that they are scaling or measurement variables rather than fundamental risk drivers. Put differently, you can choose to value a Brazilian companies in US dollars, but doing so does not make Brazilian country risk go away.

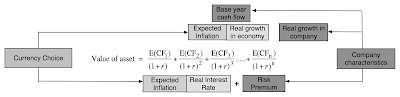

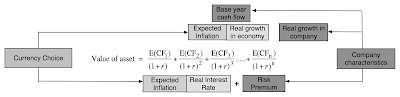

So, why do currencies matter? It is because each one has different expectations of inflation embedded in it, and when using a currency, you have to remain inflation-consistent. In other words, if you decide to do your analysis in a high inflation currency, your discount rate has to be higher, to incorporate the higher inflation, and so do your cash flows, for the same reason:

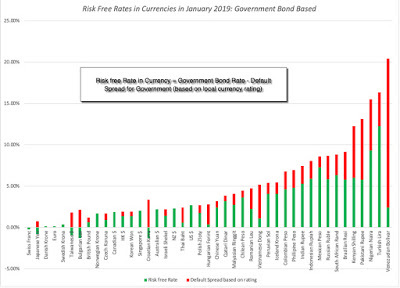

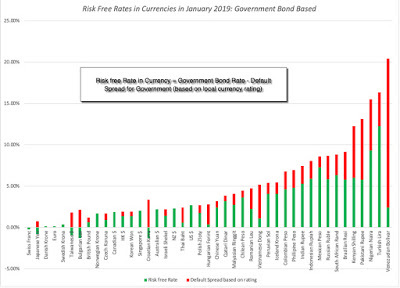

There are two ways in which you can bring inflation into discount rates. The first is to use the risk free rate in that currency as your starting point for the calculation, since risk free rates will be higher for high inflation currencies. The challenge is finding a risk free investment in many emerging market currencies, since even the governments bonds, in those currencies, have default risk embedded in them. I attempt to overcome this problem by starting with the government bond but then netting the default spread for the government in question from that bond to arrive at risk free rates:

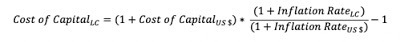

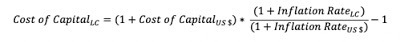

Download raw dataThese rates are only as reliable as the government bond rates that you start with, and since more than two thirds of all currencies don't even have government bonds and even on those that do, the government bond rate does not come from liquid markets, there a second approach that you can use to adjust for currencies. In this approach, you estimate the cost of capital in a currency that you feel comfortable with (in terms of estimating risk free rates and risk premiums) and then add on or incorporate the differential inflation between that currency and the local currency that you want to convert the cost of capital to. Thus, to convert the cost of capital in US $ terms to a different currency, you would do the following:

Download raw dataThese rates are only as reliable as the government bond rates that you start with, and since more than two thirds of all currencies don't even have government bonds and even on those that do, the government bond rate does not come from liquid markets, there a second approach that you can use to adjust for currencies. In this approach, you estimate the cost of capital in a currency that you feel comfortable with (in terms of estimating risk free rates and risk premiums) and then add on or incorporate the differential inflation between that currency and the local currency that you want to convert the cost of capital to. Thus, to convert the cost of capital in US $ terms to a different currency, you would do the following:

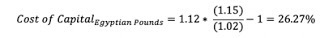

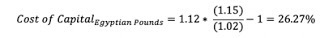

To illustrate, assume that you have a US dollar cost of capital of 12% for an Egyptian company and that the inflation rates are 15% and 2% in Egyptian Pounds and US dollars respectively:

The Egyptian pound cost of capital is 26.27%. Note that there is an approximation that is often used, where the differential inflation is added to the US dollar cost of capital; in this case your answer would have been 25%. The key to this approach is getting estimates of expected inflation, and while every source will come with warts, you can find the IMF's estimates of expected inflation in different currencies at this link.

The Egyptian pound cost of capital is 26.27%. Note that there is an approximation that is often used, where the differential inflation is added to the US dollar cost of capital; in this case your answer would have been 25%. The key to this approach is getting estimates of expected inflation, and while every source will come with warts, you can find the IMF's estimates of expected inflation in different currencies at this link.

General Propositions

Every company, small or large, has a hurdle rate, though the origins of the number are murky at most companies. The approach laid out in this post has implications for how hurdle rates get calculated and used.

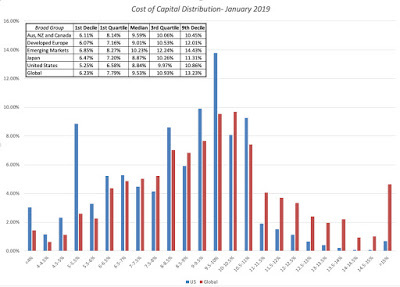

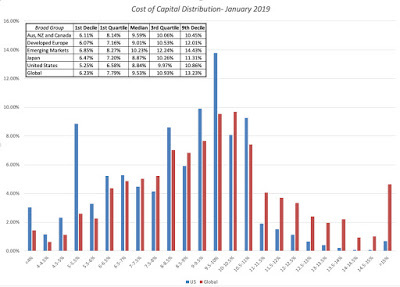

A hurdle rate for an investment should be more a reflection the risk in the investment, and less your cost of raising funding: I fault terminology for this, but most people, when asked what a cost of capital is, will respond with the answer that it is the cost of raising capital. In the context of its usage as a hurdle rate, that is not true. It is an opportunity cost, a rate of return that you (as a company or investor) can earn on other investments in the market of equivalent risk. That is why, when valuing a target firm in an acquisition, you should always use the risk characteristics of the target firm (its beta and debt capacity) to compute a cost of capital, rather than the cost of capital of the acquiring firm.A company-wide hurdle rate can be misleading and dangerous: In corporate finance, the hurdle rate becomes the number to beat, when you do investment analysis. A project that earns more than the hurdle rate becomes an acceptable one, whether you use cash flows (and compute a positive net present value) or income (and generate a return greater than the hurdle rate). Most companies claim to have a corporate hurdle rate, a number that all projects that are assessed within the company get measured against. If your company operates in only one business and one country, this may work, but to the extent that companies operate in many businesses across multiple countries, you can already see that there can be no one hurdle rate. Even if you use only one currency in analysis, your cost of capital will be a function of which business a project is in, and what country it is aimed at. The consequences of not making these differential adjustments will be that your safe businesses will end up subsidizing your risky businesses, and over time, both will be hurt, in what I term the "curse of the lazy conglomerate".Currency is a choice, but once chosen, should not change the outcome of your analysis: We spend far too much time, in my view, debating what currency to do an analysis in, and too little time working through the implications. If you follow the consistency rule on currency, incorporating inflation into both cash flows and discount rates, your analyses should be currency neutral. In other words, a project that looks like it is a bad project, when the analysis is done in US dollar terms, cannot become a good project, just because you decide to do the analysis in Indian rupees. I know that, in practice, you do get divergent answers with different currencies, but when you do, it is because there are inflation inconsistencies in your assessments of discount rates and cash flows.You cannot (and should not) insulate your cost of capital from market forces: In both corporate finance and investing, there are many who remain wary of financial markets and their capacity to be irrational and volatile. Consequently, they try to generate hurdle rates that are unaffected by market movements, a futile and dangerous exercise, because we have to be price takers on at least some of the inputs into hurdle rates. Take the risk free rate, for instance. For the last decade, there are many analysts who have replaced the actual risk free rate (US 10-year T.Bond rate, for instance) with a "normalized' higher number, using the logic that interest rates are too low and will go up. Holding all else constant, this will push up hurdle rates and make it less likely that you will invest (either as an investor or as a company), but to what end? That uninvested money cannot be invested at the normalized rate, since it is fictional and exists only in the minds of those who created it, but is invested instead at the "too low" rate. Have perspective: In conjunction with the prior point, there seems to be a view in some companies and for some investors, that they can use whatever number they feel comfortable with as hurdle rates. To the extent that hurdle rates are opportunity costs in the market, this is not true. The cost of capital brings together all of the risks that we have listed in this section. If nothing else, to get perspective on what comprises high or low, when it comes to cost of capital, I have computed a histogram of global and US company costs of capital, in US $ terms.

You can convert this table into any currency you want. The bottom line is that, at least at the start of 2019, a dollar cost of capital of 14% or 15% is an extremely high number for any publicly traded company. You can see the costs of capital, in dollar terms, for US companies at this link, and as with betas, you can download the cost of capital, by industry, for other parts of the world in the data links below this post.In short, if you work at a company, and you are given a hurdle rate to use, it behooves you to ask questions about its origins and logic. Often, you will find that no one really seems to know and/or the logic is questionable.

YouTube Video

Data Sets

Betas by Business: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India, China, Aus & CanadaSovereign Ratings and CDS Spreads by Country in January 2019Equity Risk Premiums by Country in January 2019Risk free Rates by Currency: Government bond basedCost of Capital in US $ (with conversion equation for other currencies): US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India, China, Aus & CanadaJanuary 2019 Data UpdatesData Update 1: A Reminder that equities are risky, in case you forgot!Data Update 2: The Message from Bond MarketsData Update 3: Playing the Numbers GameData Update 4: The Many Faces of RiskData Update 5: Of Hurdle Rates and Funding Costs!

A Quick Introduction

The simplest way to introduce hurdle rates is to look at them from the perspectives of the capital providers to a business. Using a financial balance sheet as my construct, here is a big picture view of these costs:

Thus. the hurdle rate for equity investors, i.e., the cost of equity, is the rate that they need to make, to break even, given the risk that they perceive in their equity investments. Lenders, on the other hand, incorporate their concerns about default risk into the interest rates they set on leans, i.e., the cost of debt. From the perspective of a business that raises funds from both equity investors and lenders, it is a weighted average of what equity investors need to make and what lenders demand as interest rates on borrowing, that represents the overall cost of funding, i.e., the cost of capital.

I have described the cost of capital as the Swiss Army Knife of finance, used in many different contexts and with very different meanings. I have reproduced below the different uses in a picture:

Paper on cost of capitalIt is precisely because the cost of capital is used in so many different places that it is also one of the most misunderstood and misused numbers in finance. The best way to reconcile the different perspectives is to remember that the cost of capital is ultimately determined by the risk of the enterprise raising the funding, and that all of the many risks that a firm faces have to find their way into it. I have always found it easiest to break the cost of capital into parts, and let each part convey a specific risk, since if I am careless, I end up missing or double counting risk. In this post, I will break the risks that a company faces into four groups: the business or businesses the company operates in (business risk), the geographies that it operates in (country risk), how much it has chosen to borrow (financial leverage risk) and the currencies its cash flows are in (currency effects).

Paper on cost of capitalIt is precisely because the cost of capital is used in so many different places that it is also one of the most misunderstood and misused numbers in finance. The best way to reconcile the different perspectives is to remember that the cost of capital is ultimately determined by the risk of the enterprise raising the funding, and that all of the many risks that a firm faces have to find their way into it. I have always found it easiest to break the cost of capital into parts, and let each part convey a specific risk, since if I am careless, I end up missing or double counting risk. In this post, I will break the risks that a company faces into four groups: the business or businesses the company operates in (business risk), the geographies that it operates in (country risk), how much it has chosen to borrow (financial leverage risk) and the currencies its cash flows are in (currency effects).

Note that each part of the cost of capital has a key risk embedded in it. Thus, when valuing a company, in US dollars, in a safe business in a risky country, with very little financial leverage, you will see the 10-year US treasury bond rate as my risk free rate, a low beta (reflecting the safety of the business and low debt), but a high equity risk premium (reflecting the risk of the country). The rest of this post will look at each of the outlined risks.

I. Business Risk

In my last post, where I updated risk measures across the world, I also looked at how these measures varied across different industries/businesses. In particular, I highlighted the ten most risky and safest industries, based upon both price variability and earnings variability, and noted the overlap between the two measures. I also looked at how the perceived risk in a business can change, depending upon investor diversification, and captured this effect with the correlation with the overall market. If you are diversified, I argued that you would measure the risk in an investment with the covariance of that investment with the market, or in its standardized form, its beta.

To get the beta for a company, then, you can adopt one of two approaches.

The first, and the one that is taught in every finance class, is to run a regression of returns on the stock against a market index and to use the regression beta. The second, and my preferred approach, is to estimate a beta by looking at the business or businesses a company operates in, and taking a weighted average of the betas of companies in that business. To use the second approach, you need betas by business, and each year, I estimate these numbers by averaging the betas of publicly traded companies in each business. These betas, in addition to reflecting the risk of the business, also reflect the financial leverage of companies in that business (with more debt pushing up betas) and their holdings in cash and marketable securities (which, being close to risk less, push down betas). Consequently, I adjust the average beta for both variables to estimate what is called a pure play or a business beta for each business. (Rather than bore you with the mechanics, please watch this video on how I make these adjustments). The resulting estimates are shown at this link, for US companies. (You can also download the spreadsheets that contain the estimates for other parts of the world, as well as global averages, by going to the end of this post).

To get from these business betas to the beta of a company, you need to first identify what businesses the company operates in, and then how much value it derives from each of the businesses. The first part is usually simple to do, though you may face the challenge of finding the right bucket to put a business into, but the second part is usually difficult, because the individual businesses do not trade. You can use revenues or operating income by business as approximations to estimate weights or apply multiples to each of these variables (by looking at what other companies in the business trade at) to arrive at value weights.

II. Financial LeverageYou can run a company, without ever using debt financing, or you can choose to borrow money to finance operations. In some cases, your lack of access to new equity may force you to borrow money and, in others, you may borrow money because you believe it will lower your cost of capital. In general, the choice of whether you use debt or equity remains one of the key parts of corporate finance, and I will discuss it in one of my upcoming data posts. In this post, though, I will just posit that your cost of capital can be affected by how much you borrow, unless you live in a world where there are no taxes, default risk or agency problems, in which case your cost of capital will remain unchanged as your funding mix changes. If you do borrow money to fund some or a significant portion of your operations, there are three numbers that you need to estimate for your cost of capital:

Debt Ratio: Th mix of debt and equity that you use represents the weights in your cost of capital.Beta Effect: As you borrow money, your equity will become riskier, because it is a residual claim, and having more interest expenses will make that claim more volatile. If you use beta as your measure of risk, this will require you to adjust upwards the business (or unlettered) beta that you obtained in the last part, using the debt to equity ratio of the company.

Cost of Debt: The cost of debt, which is set by lenders based upon how much default risk that they see in a company, will enter the cost of capital equation, with an added twist. To the extent that the tax law is tilted towards debt, the after-tax cost of borrowing will reflect that tax benefit. Since this cost of debt is a cost of borrowing money, long term and today, you cannot use a book interest rate or the interest rate on existing debt. Instead, you have to estimate a default spread for the company, based upon either its bond ratings or financial ratios, and add that spread on to the risk free rate:

Cost of Debt: The cost of debt, which is set by lenders based upon how much default risk that they see in a company, will enter the cost of capital equation, with an added twist. To the extent that the tax law is tilted towards debt, the after-tax cost of borrowing will reflect that tax benefit. Since this cost of debt is a cost of borrowing money, long term and today, you cannot use a book interest rate or the interest rate on existing debt. Instead, you have to estimate a default spread for the company, based upon either its bond ratings or financial ratios, and add that spread on to the risk free rate:

I look at the debt effect on the cost of capital in each of the industries that I follow, with all three effects incorporated in this link, for US companies. The data, broken down, by other regional sub-groupings is available at the end of this post.

I look at the debt effect on the cost of capital in each of the industries that I follow, with all three effects incorporated in this link, for US companies. The data, broken down, by other regional sub-groupings is available at the end of this post.III. Country Risk

It strikes me as common sense that operating in some countries will expose you to more risk than operating in others, and that the cost of capital (hurdle rate) you use should reflect that additional risk. While there are some who are resistant to this proposition, making the argument that country risk can be diversified by having a global portfolio, that argument is undercut by rising correlations across markets. Consequently, the question becomes not whether you should incorporate country risk, but how best to do it. There are three broad choices:

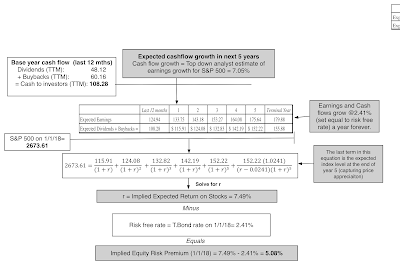

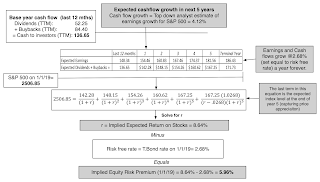

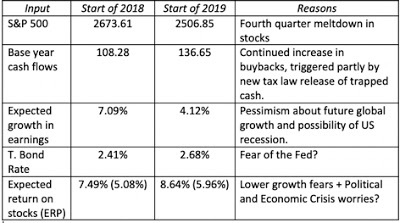

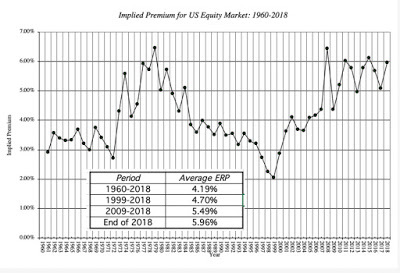

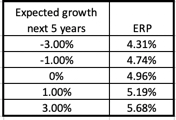

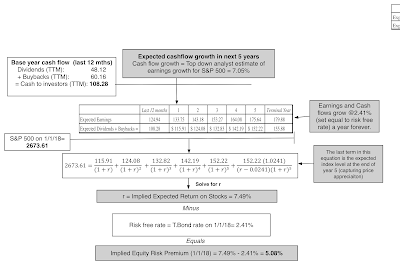

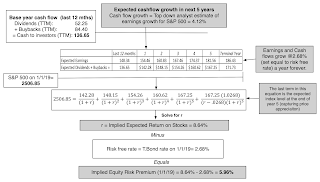

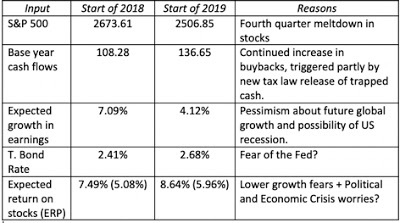

Sovereign Ratings and Default Spreads: The vast majority of countries have sovereign ratings, measuring their default risk, and since these ratings go with default spreads, there are many who use these default spreads as measures of country risk. Sovereign CDS spreads: The Credit Default Swap (CDS) market is one where you can buy insurance against sovereign default, and it offers a market-based estimate of sovereign risk. While the coverage is less than what you get from sovereign ratings, the number of countries where you can obtain these spreads has increased over time to reach 71 in 2019. Country Risk Premiums: I start with the default spreads, but I add a scaling factor to reflect the reality that equities are riskier than government bonds to come up with country risk premiums. The scaling factor that I use is obtained by dividing the volatility of an emerging market equity index by the volatility of emerging market bonds. To incorporate the country risk into my cost of capital calculations, I start with the implied equity risk premium that I estimated for the US (see my first data post for 2019) or 5.96% and add to it the country risk premium for each country. The full adjustment process is described in this picture:

I also bring in frontier markets, which have no sovereign ratings, using a country risk score estimated by Political Risk Services. The final estimates of equity risk premiums around the world can be seen in the picture below:

You can see these equity risk premiums as a list by clicking here, or download the entire spreadsheet here. If you prefer a picture of equity risk around the world, my map is below:

Download spreadsheetI also report regional equity risk premiums, computed by taking GDP-weighted averages of the equity risk premiums of the countries int he region.

Download spreadsheetI also report regional equity risk premiums, computed by taking GDP-weighted averages of the equity risk premiums of the countries int he region.IV. Currency Risk

It is natural to mix up countries and currencies, when you do your analysis, because the countries with the most risk often have the most volatile currencies. That said, my suggestion is that you keep it simple, when it comes to currencies, recognizing that they are scaling or measurement variables rather than fundamental risk drivers. Put differently, you can choose to value a Brazilian companies in US dollars, but doing so does not make Brazilian country risk go away.

So, why do currencies matter? It is because each one has different expectations of inflation embedded in it, and when using a currency, you have to remain inflation-consistent. In other words, if you decide to do your analysis in a high inflation currency, your discount rate has to be higher, to incorporate the higher inflation, and so do your cash flows, for the same reason:

There are two ways in which you can bring inflation into discount rates. The first is to use the risk free rate in that currency as your starting point for the calculation, since risk free rates will be higher for high inflation currencies. The challenge is finding a risk free investment in many emerging market currencies, since even the governments bonds, in those currencies, have default risk embedded in them. I attempt to overcome this problem by starting with the government bond but then netting the default spread for the government in question from that bond to arrive at risk free rates:

Download raw dataThese rates are only as reliable as the government bond rates that you start with, and since more than two thirds of all currencies don't even have government bonds and even on those that do, the government bond rate does not come from liquid markets, there a second approach that you can use to adjust for currencies. In this approach, you estimate the cost of capital in a currency that you feel comfortable with (in terms of estimating risk free rates and risk premiums) and then add on or incorporate the differential inflation between that currency and the local currency that you want to convert the cost of capital to. Thus, to convert the cost of capital in US $ terms to a different currency, you would do the following:

Download raw dataThese rates are only as reliable as the government bond rates that you start with, and since more than two thirds of all currencies don't even have government bonds and even on those that do, the government bond rate does not come from liquid markets, there a second approach that you can use to adjust for currencies. In this approach, you estimate the cost of capital in a currency that you feel comfortable with (in terms of estimating risk free rates and risk premiums) and then add on or incorporate the differential inflation between that currency and the local currency that you want to convert the cost of capital to. Thus, to convert the cost of capital in US $ terms to a different currency, you would do the following:

To illustrate, assume that you have a US dollar cost of capital of 12% for an Egyptian company and that the inflation rates are 15% and 2% in Egyptian Pounds and US dollars respectively:

The Egyptian pound cost of capital is 26.27%. Note that there is an approximation that is often used, where the differential inflation is added to the US dollar cost of capital; in this case your answer would have been 25%. The key to this approach is getting estimates of expected inflation, and while every source will come with warts, you can find the IMF's estimates of expected inflation in different currencies at this link.

The Egyptian pound cost of capital is 26.27%. Note that there is an approximation that is often used, where the differential inflation is added to the US dollar cost of capital; in this case your answer would have been 25%. The key to this approach is getting estimates of expected inflation, and while every source will come with warts, you can find the IMF's estimates of expected inflation in different currencies at this link.General Propositions

Every company, small or large, has a hurdle rate, though the origins of the number are murky at most companies. The approach laid out in this post has implications for how hurdle rates get calculated and used.

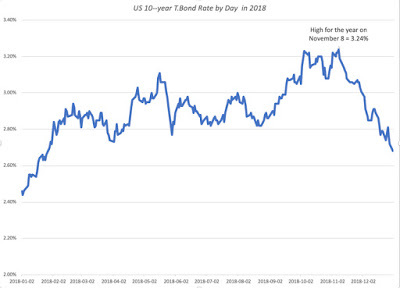

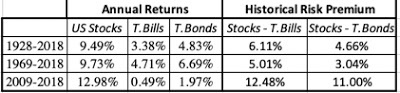

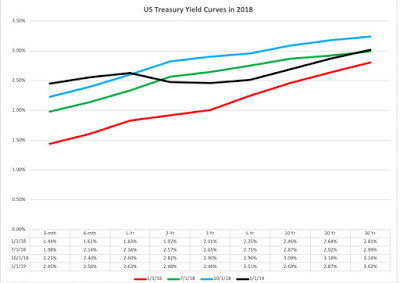

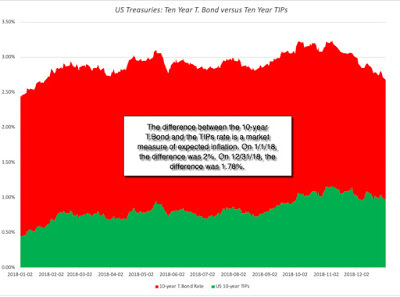

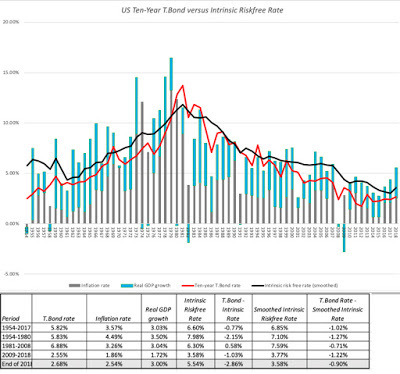

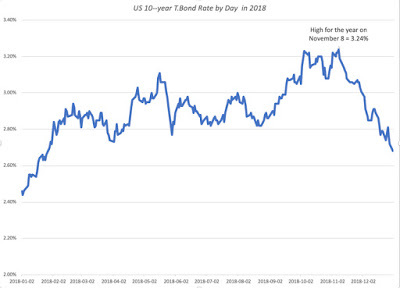

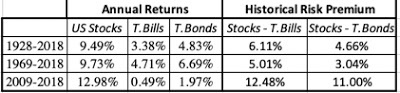

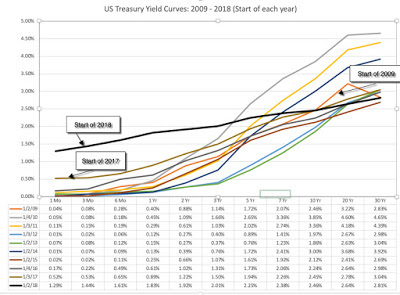

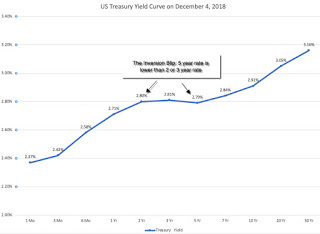

A hurdle rate for an investment should be more a reflection the risk in the investment, and less your cost of raising funding: I fault terminology for this, but most people, when asked what a cost of capital is, will respond with the answer that it is the cost of raising capital. In the context of its usage as a hurdle rate, that is not true. It is an opportunity cost, a rate of return that you (as a company or investor) can earn on other investments in the market of equivalent risk. That is why, when valuing a target firm in an acquisition, you should always use the risk characteristics of the target firm (its beta and debt capacity) to compute a cost of capital, rather than the cost of capital of the acquiring firm.A company-wide hurdle rate can be misleading and dangerous: In corporate finance, the hurdle rate becomes the number to beat, when you do investment analysis. A project that earns more than the hurdle rate becomes an acceptable one, whether you use cash flows (and compute a positive net present value) or income (and generate a return greater than the hurdle rate). Most companies claim to have a corporate hurdle rate, a number that all projects that are assessed within the company get measured against. If your company operates in only one business and one country, this may work, but to the extent that companies operate in many businesses across multiple countries, you can already see that there can be no one hurdle rate. Even if you use only one currency in analysis, your cost of capital will be a function of which business a project is in, and what country it is aimed at. The consequences of not making these differential adjustments will be that your safe businesses will end up subsidizing your risky businesses, and over time, both will be hurt, in what I term the "curse of the lazy conglomerate".Currency is a choice, but once chosen, should not change the outcome of your analysis: We spend far too much time, in my view, debating what currency to do an analysis in, and too little time working through the implications. If you follow the consistency rule on currency, incorporating inflation into both cash flows and discount rates, your analyses should be currency neutral. In other words, a project that looks like it is a bad project, when the analysis is done in US dollar terms, cannot become a good project, just because you decide to do the analysis in Indian rupees. I know that, in practice, you do get divergent answers with different currencies, but when you do, it is because there are inflation inconsistencies in your assessments of discount rates and cash flows.You cannot (and should not) insulate your cost of capital from market forces: In both corporate finance and investing, there are many who remain wary of financial markets and their capacity to be irrational and volatile. Consequently, they try to generate hurdle rates that are unaffected by market movements, a futile and dangerous exercise, because we have to be price takers on at least some of the inputs into hurdle rates. Take the risk free rate, for instance. For the last decade, there are many analysts who have replaced the actual risk free rate (US 10-year T.Bond rate, for instance) with a "normalized' higher number, using the logic that interest rates are too low and will go up. Holding all else constant, this will push up hurdle rates and make it less likely that you will invest (either as an investor or as a company), but to what end? That uninvested money cannot be invested at the normalized rate, since it is fictional and exists only in the minds of those who created it, but is invested instead at the "too low" rate. Have perspective: In conjunction with the prior point, there seems to be a view in some companies and for some investors, that they can use whatever number they feel comfortable with as hurdle rates. To the extent that hurdle rates are opportunity costs in the market, this is not true. The cost of capital brings together all of the risks that we have listed in this section. If nothing else, to get perspective on what comprises high or low, when it comes to cost of capital, I have computed a histogram of global and US company costs of capital, in US $ terms.