Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 20

March 2, 2018

Interest Rates and Stock Prices: It's Complicated!

Jerome Powell, the new Fed Chair, was on Capitol Hill on February 27, and his testimony was, for the most part, predictable and uncontroversial. He told Congress that he believed that the economy had strengthened over the course of the last year and that the Fed would continue on its path of "raising rates". Analysts have spent the next few days reading the tea leaves of his testimony, to decide whether this would translate into three or four rate hikes and what this would mean for stocks. In fact, the blame for the drop in stocks over the last four trading days has been placed primarily on the Fed bogeyman, with protectionism providing an assist on the last two days. While there may be an element of truth to this, I am skeptical about any Fed-based arguments for market increases and decreases, because I disagree fundamentally with many about how much power central banks have to set interest rates, and how those interest rates affect value.

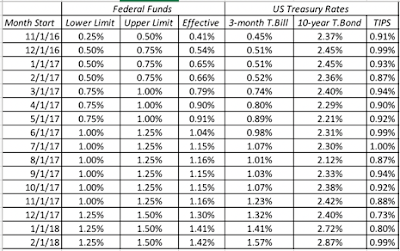

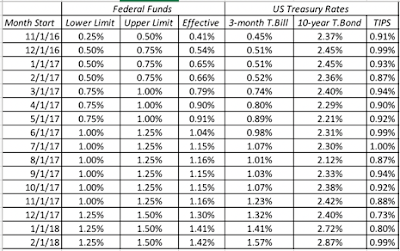

1. The Fed's power to set interest rates is limitedI have repeatedly pushed back against the notion that the Fed or any central bank somehow sets market interest rates, since it really does not have the power to do so. The only rate that the Fed sets directly is the Fed funds rate, and while it is true that the Fed's actions on that rate send signals to markets, those signals are fuzzy and do not always have predictable consequences. In fact, it is worth noting that the Fed has been hiking the Fed Funds rate since December 2016, when Janet Yellen's Fed initiated this process, raising the Fed Funds rate by 0.25%. In the months since, the effects of the Fed Fund rate changes on long term rates is debatable, and while short term rate have gone up, it is not clear whether the Fed Funds rate is driving short term rates or whether market rates are driving the Fed.

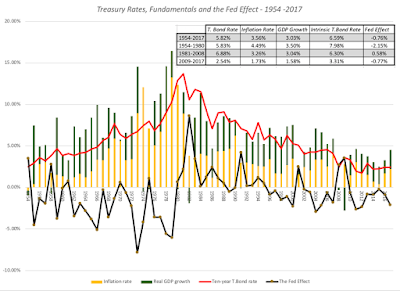

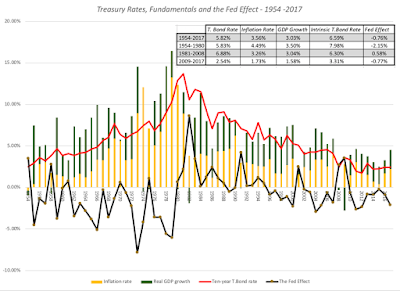

It is true that post-2008, the Fed has been much more aggressive in buying bonds in financial markets in its quantitative easing efforts to keep rates low. While that was started as a response to the financial crisis of 2008, it continued for much of the last decade and clearly has had an impact on interest rates. To those who would argue that it was the Fed, through its Fed Funds rate and quantitative easing policies that kept long term rates low from 2008-2017, I would beg to differ, since there are two far stronger fundamental factors at play - low or no inflation and anemic real economic growth. In the graph below, I have the treasury bond rate compared to the sum of inflation and real growth each year, with the difference being attributed to the Fed effect: Download spreadsheet with raw dataYou have seen me use this graph before, but my point is a simple one. The Fed is less rate-setter, when it comes to market interest rates, than rate-influencer, with the influence depending upon its credibility. While rates were low in the 2009-2017 time period, and the Fed did play a role (the Fed effect lowered rates by 0.77%), the primary reasons for low rates were fundamental. It is for that reason that I described the Fed Chair as the Wizard of Oz, drawing his or her power from the perception that he or she has power, rather than actual power. That said, the Fed effect at the start of 2018, as I noted in a post at the beginning of the year, is larger than it has been at any time in the last decade, perhaps setting the stage for the tumult in stock and bond markets in the last few weeks.

Download spreadsheet with raw dataYou have seen me use this graph before, but my point is a simple one. The Fed is less rate-setter, when it comes to market interest rates, than rate-influencer, with the influence depending upon its credibility. While rates were low in the 2009-2017 time period, and the Fed did play a role (the Fed effect lowered rates by 0.77%), the primary reasons for low rates were fundamental. It is for that reason that I described the Fed Chair as the Wizard of Oz, drawing his or her power from the perception that he or she has power, rather than actual power. That said, the Fed effect at the start of 2018, as I noted in a post at the beginning of the year, is larger than it has been at any time in the last decade, perhaps setting the stage for the tumult in stock and bond markets in the last few weeks.

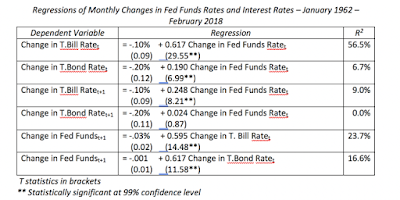

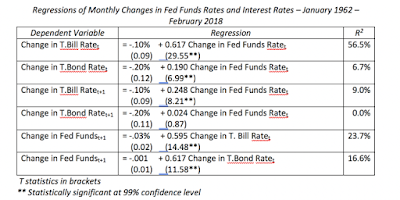

To examine more closely the relationship between moves in the Fed Funds rate and treasury rates, I collected monthly data on the Fed Funds rate, the 3-month US treasury bill rate and the US 10-year treasury bond rate every month from January 1962 to February 2018. The raw data is at the link below, but I regressed the changes in both short term and long term treasuries against changes in the Fed funds rate in the same month: Looking at these regressions, here are some interesting conclusions that emerge:Short term T.Bill rates and the Fed Funds rate move together strongly: The result backs up the intuition that the Fed Funds rate and the short term treasury rate are connected strongly, with an R-squared of 56.5%; a 1% increase in the Fed Funds rate is accompanied by a 0.62% increase in the T.Bill rate, in the same month. Note, though, that this regression, by itself, tells you nothing about the direction of the effect, i.e., whether higher Fed funds rates lead to higher short term treasury rates or whether higher rates in the short term treasury bill market lead the Fed to push up the Fed Funds rate. T.Bond rates move with the Fed Funds rate, but more weakly: The link between the Fed Funds rate and the 10-year treasury bond rate is mush weaker, with an R-squared of 6.7%; a 1% increase in the Fed Funds rate is accompanied by a 0.19% increase in the 10-year treasury bond rate. T. Bill rates lead, Fed Funds rates lag: Regressing changes in Fed funds rates against changes in T.Bill rates in the following period, and then reversing direction and regressing changes in T.Bill rates against changes in the Fed Funds rate in the following period, provide clues to the direction of the relationship. At least over this time period, and using monthly changes, it is changes in T.Bill rates that lead changes in Fed Funds rates more strongly, with an R squared of 23.7%, as opposed to an R-squared of 9% for the alternate hypothesis. With treasury bond rates, there is no lagged effect of Fed funds rate changes (R squared of zero), while changes in T.Bond rates do predict changes in the Fed Funds rate in the subsequent period. The Fed is more a follower of markets, than a leader. The bottom line is that if you are trying to get a measure of how much treasury bond rates will change over the next year or two, you will be better served focusing more on changes in economic fundamentals and less on Jerome Powell and the Fed.

Looking at these regressions, here are some interesting conclusions that emerge:Short term T.Bill rates and the Fed Funds rate move together strongly: The result backs up the intuition that the Fed Funds rate and the short term treasury rate are connected strongly, with an R-squared of 56.5%; a 1% increase in the Fed Funds rate is accompanied by a 0.62% increase in the T.Bill rate, in the same month. Note, though, that this regression, by itself, tells you nothing about the direction of the effect, i.e., whether higher Fed funds rates lead to higher short term treasury rates or whether higher rates in the short term treasury bill market lead the Fed to push up the Fed Funds rate. T.Bond rates move with the Fed Funds rate, but more weakly: The link between the Fed Funds rate and the 10-year treasury bond rate is mush weaker, with an R-squared of 6.7%; a 1% increase in the Fed Funds rate is accompanied by a 0.19% increase in the 10-year treasury bond rate. T. Bill rates lead, Fed Funds rates lag: Regressing changes in Fed funds rates against changes in T.Bill rates in the following period, and then reversing direction and regressing changes in T.Bill rates against changes in the Fed Funds rate in the following period, provide clues to the direction of the relationship. At least over this time period, and using monthly changes, it is changes in T.Bill rates that lead changes in Fed Funds rates more strongly, with an R squared of 23.7%, as opposed to an R-squared of 9% for the alternate hypothesis. With treasury bond rates, there is no lagged effect of Fed funds rate changes (R squared of zero), while changes in T.Bond rates do predict changes in the Fed Funds rate in the subsequent period. The Fed is more a follower of markets, than a leader. The bottom line is that if you are trying to get a measure of how much treasury bond rates will change over the next year or two, you will be better served focusing more on changes in economic fundamentals and less on Jerome Powell and the Fed.

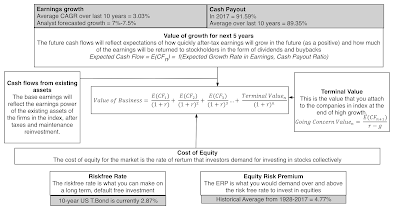

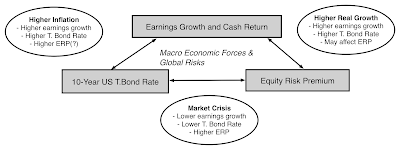

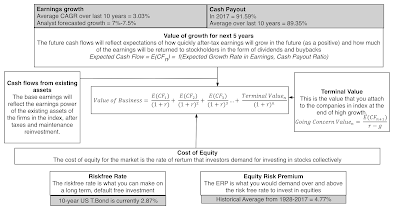

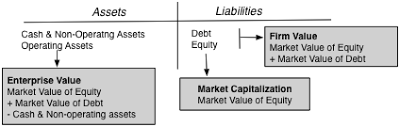

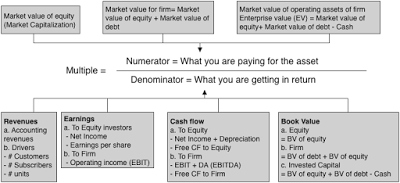

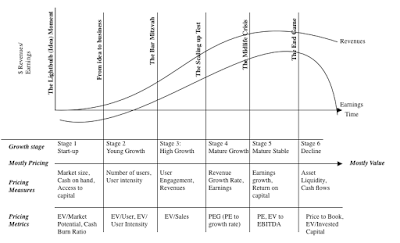

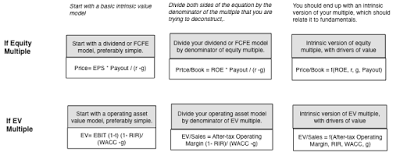

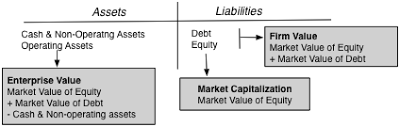

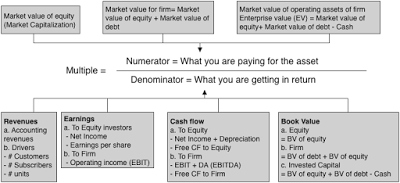

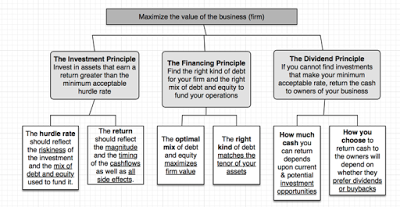

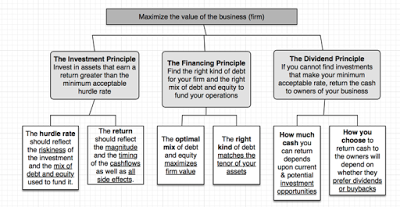

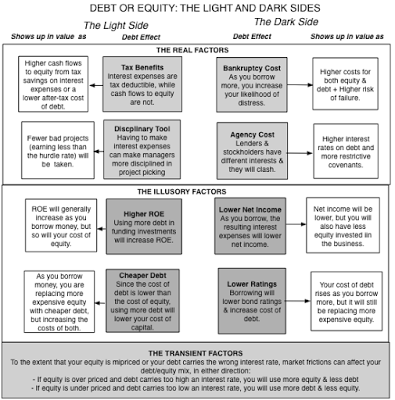

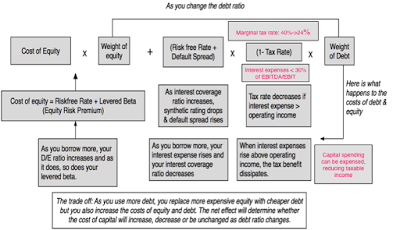

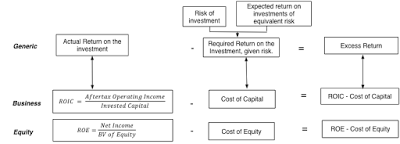

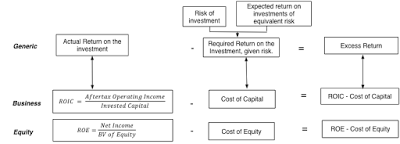

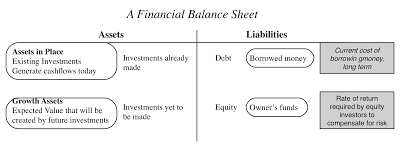

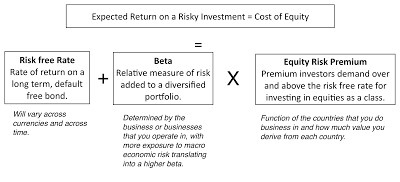

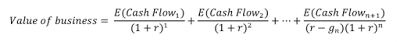

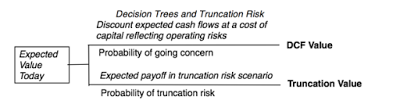

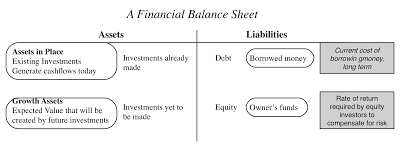

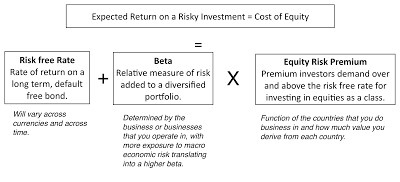

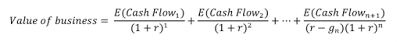

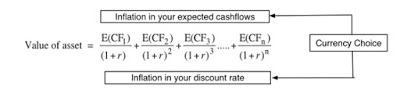

2. The relationship between interest rates and stock market value is complicatedWhen interest rates go up, stock prices should go down, right? Though you may believe or have been told that the answer is obvious, that higher interest rates are bad for stock prices, the answer is not straight forward. To understand why people are drawn to the notion that higher rates are bad for value, all you need to do is go back to the drivers of stock market value:

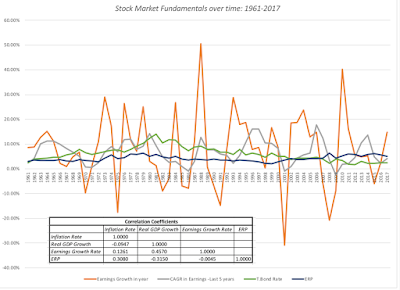

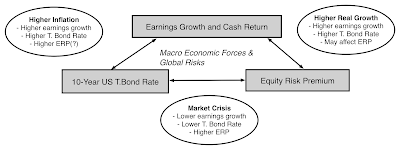

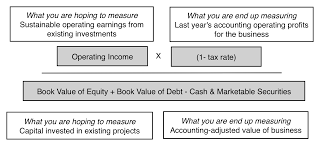

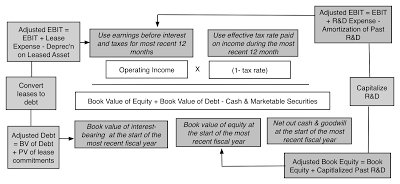

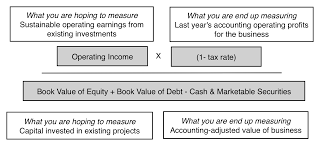

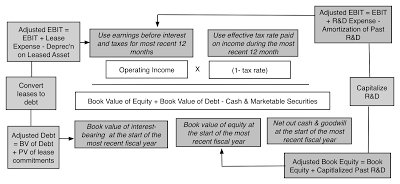

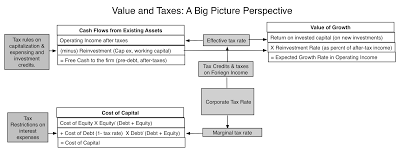

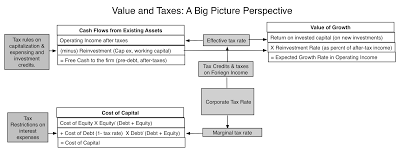

As you can see in this picture, holding all else constant, and raising long term interest rates, will increase the discount rate (cost of equity and capital), and reduce value. That assessment, though, is built on the presumption that the forces that push up interest rates have no effect on the other inputs into value - the equity risk premium, earnings growth and cash flows, a dangerous delusion, since these variables are all connected together to a macro economy. Note that almost any macro economic change, whether it be a surge in inflation, an increase in real growth or a global crisis (political or economic) affects earnings growth, T.Bond rates and the equity risk premiums, making the impact on value indeterminate, until you have worked through the net effect. To illustrate the interconnections between earnings growth rates, equity risk premiums and macroeconomic fundamentals, I looked at data on all of the variables going back to 1961:

Note that almost any macro economic change, whether it be a surge in inflation, an increase in real growth or a global crisis (political or economic) affects earnings growth, T.Bond rates and the equity risk premiums, making the impact on value indeterminate, until you have worked through the net effect. To illustrate the interconnections between earnings growth rates, equity risk premiums and macroeconomic fundamentals, I looked at data on all of the variables going back to 1961:

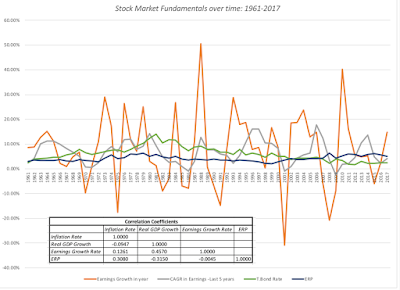

Download spreadsheet with raw dataThe co-movement in the variables and their sensitivity to macro economic fundamentals is captured in the correlation table. Higher inflation, over this period, is accompanied by higher earnings growth but also increases equity risk premiums and suppresses real growth, making its net effect often more negative than positive. Higher real economic growth, on the other hand, by pushing up earnings growth rate and lowering equity risk premiums, has a much more positive effect on value.

Download spreadsheet with raw dataThe co-movement in the variables and their sensitivity to macro economic fundamentals is captured in the correlation table. Higher inflation, over this period, is accompanied by higher earnings growth but also increases equity risk premiums and suppresses real growth, making its net effect often more negative than positive. Higher real economic growth, on the other hand, by pushing up earnings growth rate and lowering equity risk premiums, has a much more positive effect on value.

3. Value has to be built around a consistent narrativeIn my post from February 10, right after the last market meltdown, I offered an intrinsic valuation model for the S&P 500, with a suggestion that you fill in your inputs and come up with your own estimate of value. Some of you did take me up on my offer, came up with inputs, and entered them into a shared Google spreadsheet and, in your collective wisdom, the market was overvalued by about 3.34% in mid-February. While making assumptions about risk premiums, earnings growth and the treasury bond rate, I should have emphasized the importance of narrative, i.e., the macro and market story that lay behind your numbers, since without it, you can make assumptions that are internally inconsistent. To illustrate, here are two inconsistent story lines that I have seen in the last few weeks, from opposite sides of the spectrum (bearish and bullish).

In the bearish version, which I call the Interest Rate Apocalypse, all of the inputs (earnings growth for the next five years and beyond, equity risk premiums) into value are held constant, while raising the treasury bond rate to 4% or 4.5%. Not surprisingly, the effect on value is calamitous, with the value dropping about 20%. While that may alarm you, it is unclear how the analysts who tell this story explain why the forces that push interest rates upwards have no effect on earnings growth, in the next 5 years or beyond, oron equity risk premiums.In the bullish version, which I will term the Real Growth Fantasy, all of the inputs into value are left untouched, while higher growth in the US economy causes earnings growth rates to pop up. The effect again is unsurprising, with value increasing proportionately. While neither of these narratives is fully worked through, there are three separate narratives about the market that are all internally consistent, that can lead to very different judgments on value.

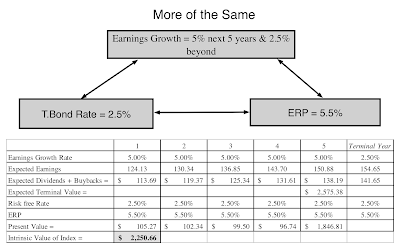

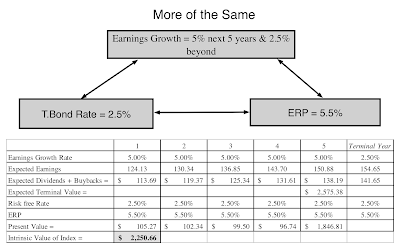

More of the same: In this narrative, you can argue that, as has been so often the case in the last decade, the breakout in the US economy will be short lived and that we will revert back the low growth, low inflation environment that developed economies have been mired in since 2008. In this story, the treasury bond rate will stay low (2.5%), earnings growth will revert back to the low levels of the last decade (3.03%) after the one-time boost from lower taxes fades, and equity risk premiums will stay at post-2008 levels (5.5%). The index value that you obtain is about 2250, about 16.4% below March 2nd levels. Download spreadsheetThe Return of Inflation: In this story line, inflation returns, though how the story plays out will depend upon how much inflation you foresee. That higher inflation rate will translate into higher earnings growth, though the effect will vary across companies, depending upon their pricing power, but it will also cause T. Bond rates to rise. If the inflation rate in the story is a high one (3% or higher), the equity risk premium may also rise, if history is any guide. With an inflation rate of 3% and an equity risk premium of 6%, the index value that you obtain is about 2133, about 20.7% below March 2nd levels.

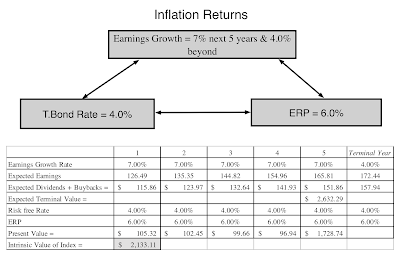

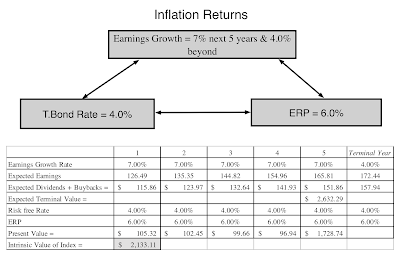

Download spreadsheetThe Return of Inflation: In this story line, inflation returns, though how the story plays out will depend upon how much inflation you foresee. That higher inflation rate will translate into higher earnings growth, though the effect will vary across companies, depending upon their pricing power, but it will also cause T. Bond rates to rise. If the inflation rate in the story is a high one (3% or higher), the equity risk premium may also rise, if history is any guide. With an inflation rate of 3% and an equity risk premium of 6%, the index value that you obtain is about 2133, about 20.7% below March 2nd levels.

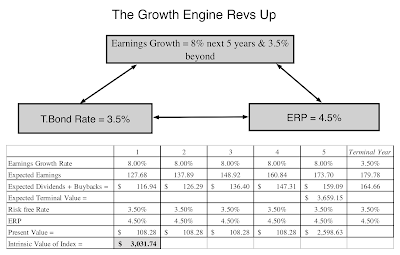

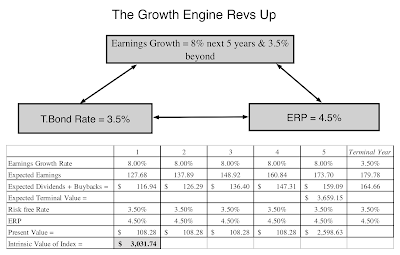

Download spreadsheetThe Growth Engine Revs Up: In this telling, it is real growth in the US economy that surges, creating tailwinds for growth in the rest of the world. That higher real growth rate, while pushing up earnings growth for US companies (to 8% for the near term), will also increase treasury bond rates (to 3.5%), as in the inflation story, but unlike it, equity risk premiums will drift back to pre-2008 levels (closer to 4.5%). The index value that you obtain is about 3031, about 12.7% above March 2nd levels.

Download spreadsheetThe Growth Engine Revs Up: In this telling, it is real growth in the US economy that surges, creating tailwinds for growth in the rest of the world. That higher real growth rate, while pushing up earnings growth for US companies (to 8% for the near term), will also increase treasury bond rates (to 3.5%), as in the inflation story, but unlike it, equity risk premiums will drift back to pre-2008 levels (closer to 4.5%). The index value that you obtain is about 3031, about 12.7% above March 2nd levels.

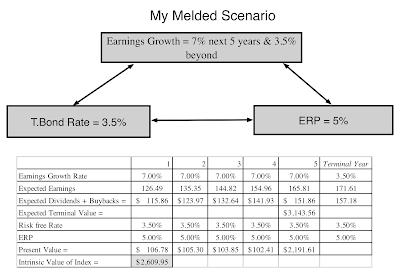

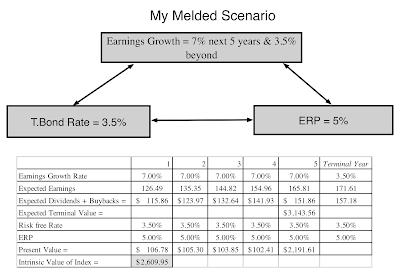

Download spreadsheetA Melded Version: I believe in a melded version of these stories, where inflation returns (but stays around 2%) and real growth in the economy increases, but only moderately. That will translate into higher treasury bond rates (my guess would be 3.5%), with a proportionate increase in earnings growth (at least in steady state) and an equity risk premium of 5%, splitting the difference between pre-crisis and post-crisis periods. The index value that I obtain, with these assumptions, is about 2610, about 3.1% below March 2nd levels.

Download spreadsheetA Melded Version: I believe in a melded version of these stories, where inflation returns (but stays around 2%) and real growth in the economy increases, but only moderately. That will translate into higher treasury bond rates (my guess would be 3.5%), with a proportionate increase in earnings growth (at least in steady state) and an equity risk premium of 5%, splitting the difference between pre-crisis and post-crisis periods. The index value that I obtain, with these assumptions, is about 2610, about 3.1% below March 2nd levels.

Download spreadsheetYou can see, even from this limited list of scenarios, that to assess how stock prices will move, as interest rates change, you have to also make a judgment on why interest rates are moving. An inflation-driven increase in interest rates is net negative for stocks, but a real-growth driven increase in interest rates is a net positive. In fact, the scenario where interest rates go down sees a much bigger drop in value than two of three scenarios, where interest rates rise.

Download spreadsheetYou can see, even from this limited list of scenarios, that to assess how stock prices will move, as interest rates change, you have to also make a judgment on why interest rates are moving. An inflation-driven increase in interest rates is net negative for stocks, but a real-growth driven increase in interest rates is a net positive. In fact, the scenario where interest rates go down sees a much bigger drop in value than two of three scenarios, where interest rates rise.

The Bottom LineWhen macro economic fundamentals change, markets take time to adjust, translating into market volatility. During these adjustment periods, you will hear a great deal of market punditry and much of it will be half baked, with the advisor or analyst focusing on one piece of the valuation puzzle and holding all else constant. Thus, you will read predictions about how much the market will drop if treasury bond rates rise to 4.5% or how much it will rise if earnings growth is 10%. I hope that this post has given you tools that you can use to fill in the rest of the story, since it is possible that stocks could actually go up, even if rates go up to 4.5%, if that rate rise is precipitated by a strong economy, and that stocks could be hurt with 10% earnings growth, if that growth comes mostly from high inflation. I also hope that, after you have listened to the narratives offered by others, for what markets will or will not do, that you start developing your own narrative for the market, as the basis for your investment decisions. You've seen my narrative, but I will leave the feedback loop open, as fresh data on inflation and growth comes in, and I plan to revisit my narrative, tweaking, adjusting or even abandoning it, if the data leads me to.

YouTube Video

Data LinksT.Bond Rates, Inflation and Real GDP Growth - 1954-2017Fed Funds Rate and Treasury Rates - 1962-2017T.Bond Rates, Earnings Growth Rates and ERP - 1961- 2017Spreadsheet LinksIntrinsic Valuation Spreadsheet for S&P 500More of the Same: SpreadsheetThe Return of Inflation: SpreadsheetThe Growth Engine Revs Up: SpreadsheetThe Melded Version: SpreadsheetBlog Post LinksTesting Times: Market Turmoil and Investment Serenity

1. The Fed's power to set interest rates is limitedI have repeatedly pushed back against the notion that the Fed or any central bank somehow sets market interest rates, since it really does not have the power to do so. The only rate that the Fed sets directly is the Fed funds rate, and while it is true that the Fed's actions on that rate send signals to markets, those signals are fuzzy and do not always have predictable consequences. In fact, it is worth noting that the Fed has been hiking the Fed Funds rate since December 2016, when Janet Yellen's Fed initiated this process, raising the Fed Funds rate by 0.25%. In the months since, the effects of the Fed Fund rate changes on long term rates is debatable, and while short term rate have gone up, it is not clear whether the Fed Funds rate is driving short term rates or whether market rates are driving the Fed.

It is true that post-2008, the Fed has been much more aggressive in buying bonds in financial markets in its quantitative easing efforts to keep rates low. While that was started as a response to the financial crisis of 2008, it continued for much of the last decade and clearly has had an impact on interest rates. To those who would argue that it was the Fed, through its Fed Funds rate and quantitative easing policies that kept long term rates low from 2008-2017, I would beg to differ, since there are two far stronger fundamental factors at play - low or no inflation and anemic real economic growth. In the graph below, I have the treasury bond rate compared to the sum of inflation and real growth each year, with the difference being attributed to the Fed effect:

Download spreadsheet with raw dataYou have seen me use this graph before, but my point is a simple one. The Fed is less rate-setter, when it comes to market interest rates, than rate-influencer, with the influence depending upon its credibility. While rates were low in the 2009-2017 time period, and the Fed did play a role (the Fed effect lowered rates by 0.77%), the primary reasons for low rates were fundamental. It is for that reason that I described the Fed Chair as the Wizard of Oz, drawing his or her power from the perception that he or she has power, rather than actual power. That said, the Fed effect at the start of 2018, as I noted in a post at the beginning of the year, is larger than it has been at any time in the last decade, perhaps setting the stage for the tumult in stock and bond markets in the last few weeks.

Download spreadsheet with raw dataYou have seen me use this graph before, but my point is a simple one. The Fed is less rate-setter, when it comes to market interest rates, than rate-influencer, with the influence depending upon its credibility. While rates were low in the 2009-2017 time period, and the Fed did play a role (the Fed effect lowered rates by 0.77%), the primary reasons for low rates were fundamental. It is for that reason that I described the Fed Chair as the Wizard of Oz, drawing his or her power from the perception that he or she has power, rather than actual power. That said, the Fed effect at the start of 2018, as I noted in a post at the beginning of the year, is larger than it has been at any time in the last decade, perhaps setting the stage for the tumult in stock and bond markets in the last few weeks. To examine more closely the relationship between moves in the Fed Funds rate and treasury rates, I collected monthly data on the Fed Funds rate, the 3-month US treasury bill rate and the US 10-year treasury bond rate every month from January 1962 to February 2018. The raw data is at the link below, but I regressed the changes in both short term and long term treasuries against changes in the Fed funds rate in the same month:

Looking at these regressions, here are some interesting conclusions that emerge:Short term T.Bill rates and the Fed Funds rate move together strongly: The result backs up the intuition that the Fed Funds rate and the short term treasury rate are connected strongly, with an R-squared of 56.5%; a 1% increase in the Fed Funds rate is accompanied by a 0.62% increase in the T.Bill rate, in the same month. Note, though, that this regression, by itself, tells you nothing about the direction of the effect, i.e., whether higher Fed funds rates lead to higher short term treasury rates or whether higher rates in the short term treasury bill market lead the Fed to push up the Fed Funds rate. T.Bond rates move with the Fed Funds rate, but more weakly: The link between the Fed Funds rate and the 10-year treasury bond rate is mush weaker, with an R-squared of 6.7%; a 1% increase in the Fed Funds rate is accompanied by a 0.19% increase in the 10-year treasury bond rate. T. Bill rates lead, Fed Funds rates lag: Regressing changes in Fed funds rates against changes in T.Bill rates in the following period, and then reversing direction and regressing changes in T.Bill rates against changes in the Fed Funds rate in the following period, provide clues to the direction of the relationship. At least over this time period, and using monthly changes, it is changes in T.Bill rates that lead changes in Fed Funds rates more strongly, with an R squared of 23.7%, as opposed to an R-squared of 9% for the alternate hypothesis. With treasury bond rates, there is no lagged effect of Fed funds rate changes (R squared of zero), while changes in T.Bond rates do predict changes in the Fed Funds rate in the subsequent period. The Fed is more a follower of markets, than a leader. The bottom line is that if you are trying to get a measure of how much treasury bond rates will change over the next year or two, you will be better served focusing more on changes in economic fundamentals and less on Jerome Powell and the Fed.

Looking at these regressions, here are some interesting conclusions that emerge:Short term T.Bill rates and the Fed Funds rate move together strongly: The result backs up the intuition that the Fed Funds rate and the short term treasury rate are connected strongly, with an R-squared of 56.5%; a 1% increase in the Fed Funds rate is accompanied by a 0.62% increase in the T.Bill rate, in the same month. Note, though, that this regression, by itself, tells you nothing about the direction of the effect, i.e., whether higher Fed funds rates lead to higher short term treasury rates or whether higher rates in the short term treasury bill market lead the Fed to push up the Fed Funds rate. T.Bond rates move with the Fed Funds rate, but more weakly: The link between the Fed Funds rate and the 10-year treasury bond rate is mush weaker, with an R-squared of 6.7%; a 1% increase in the Fed Funds rate is accompanied by a 0.19% increase in the 10-year treasury bond rate. T. Bill rates lead, Fed Funds rates lag: Regressing changes in Fed funds rates against changes in T.Bill rates in the following period, and then reversing direction and regressing changes in T.Bill rates against changes in the Fed Funds rate in the following period, provide clues to the direction of the relationship. At least over this time period, and using monthly changes, it is changes in T.Bill rates that lead changes in Fed Funds rates more strongly, with an R squared of 23.7%, as opposed to an R-squared of 9% for the alternate hypothesis. With treasury bond rates, there is no lagged effect of Fed funds rate changes (R squared of zero), while changes in T.Bond rates do predict changes in the Fed Funds rate in the subsequent period. The Fed is more a follower of markets, than a leader. The bottom line is that if you are trying to get a measure of how much treasury bond rates will change over the next year or two, you will be better served focusing more on changes in economic fundamentals and less on Jerome Powell and the Fed.2. The relationship between interest rates and stock market value is complicatedWhen interest rates go up, stock prices should go down, right? Though you may believe or have been told that the answer is obvious, that higher interest rates are bad for stock prices, the answer is not straight forward. To understand why people are drawn to the notion that higher rates are bad for value, all you need to do is go back to the drivers of stock market value:

As you can see in this picture, holding all else constant, and raising long term interest rates, will increase the discount rate (cost of equity and capital), and reduce value. That assessment, though, is built on the presumption that the forces that push up interest rates have no effect on the other inputs into value - the equity risk premium, earnings growth and cash flows, a dangerous delusion, since these variables are all connected together to a macro economy.

Note that almost any macro economic change, whether it be a surge in inflation, an increase in real growth or a global crisis (political or economic) affects earnings growth, T.Bond rates and the equity risk premiums, making the impact on value indeterminate, until you have worked through the net effect. To illustrate the interconnections between earnings growth rates, equity risk premiums and macroeconomic fundamentals, I looked at data on all of the variables going back to 1961:

Note that almost any macro economic change, whether it be a surge in inflation, an increase in real growth or a global crisis (political or economic) affects earnings growth, T.Bond rates and the equity risk premiums, making the impact on value indeterminate, until you have worked through the net effect. To illustrate the interconnections between earnings growth rates, equity risk premiums and macroeconomic fundamentals, I looked at data on all of the variables going back to 1961:

Download spreadsheet with raw dataThe co-movement in the variables and their sensitivity to macro economic fundamentals is captured in the correlation table. Higher inflation, over this period, is accompanied by higher earnings growth but also increases equity risk premiums and suppresses real growth, making its net effect often more negative than positive. Higher real economic growth, on the other hand, by pushing up earnings growth rate and lowering equity risk premiums, has a much more positive effect on value.

Download spreadsheet with raw dataThe co-movement in the variables and their sensitivity to macro economic fundamentals is captured in the correlation table. Higher inflation, over this period, is accompanied by higher earnings growth but also increases equity risk premiums and suppresses real growth, making its net effect often more negative than positive. Higher real economic growth, on the other hand, by pushing up earnings growth rate and lowering equity risk premiums, has a much more positive effect on value.3. Value has to be built around a consistent narrativeIn my post from February 10, right after the last market meltdown, I offered an intrinsic valuation model for the S&P 500, with a suggestion that you fill in your inputs and come up with your own estimate of value. Some of you did take me up on my offer, came up with inputs, and entered them into a shared Google spreadsheet and, in your collective wisdom, the market was overvalued by about 3.34% in mid-February. While making assumptions about risk premiums, earnings growth and the treasury bond rate, I should have emphasized the importance of narrative, i.e., the macro and market story that lay behind your numbers, since without it, you can make assumptions that are internally inconsistent. To illustrate, here are two inconsistent story lines that I have seen in the last few weeks, from opposite sides of the spectrum (bearish and bullish).

In the bearish version, which I call the Interest Rate Apocalypse, all of the inputs (earnings growth for the next five years and beyond, equity risk premiums) into value are held constant, while raising the treasury bond rate to 4% or 4.5%. Not surprisingly, the effect on value is calamitous, with the value dropping about 20%. While that may alarm you, it is unclear how the analysts who tell this story explain why the forces that push interest rates upwards have no effect on earnings growth, in the next 5 years or beyond, oron equity risk premiums.In the bullish version, which I will term the Real Growth Fantasy, all of the inputs into value are left untouched, while higher growth in the US economy causes earnings growth rates to pop up. The effect again is unsurprising, with value increasing proportionately. While neither of these narratives is fully worked through, there are three separate narratives about the market that are all internally consistent, that can lead to very different judgments on value.

More of the same: In this narrative, you can argue that, as has been so often the case in the last decade, the breakout in the US economy will be short lived and that we will revert back the low growth, low inflation environment that developed economies have been mired in since 2008. In this story, the treasury bond rate will stay low (2.5%), earnings growth will revert back to the low levels of the last decade (3.03%) after the one-time boost from lower taxes fades, and equity risk premiums will stay at post-2008 levels (5.5%). The index value that you obtain is about 2250, about 16.4% below March 2nd levels.

Download spreadsheetThe Return of Inflation: In this story line, inflation returns, though how the story plays out will depend upon how much inflation you foresee. That higher inflation rate will translate into higher earnings growth, though the effect will vary across companies, depending upon their pricing power, but it will also cause T. Bond rates to rise. If the inflation rate in the story is a high one (3% or higher), the equity risk premium may also rise, if history is any guide. With an inflation rate of 3% and an equity risk premium of 6%, the index value that you obtain is about 2133, about 20.7% below March 2nd levels.

Download spreadsheetThe Return of Inflation: In this story line, inflation returns, though how the story plays out will depend upon how much inflation you foresee. That higher inflation rate will translate into higher earnings growth, though the effect will vary across companies, depending upon their pricing power, but it will also cause T. Bond rates to rise. If the inflation rate in the story is a high one (3% or higher), the equity risk premium may also rise, if history is any guide. With an inflation rate of 3% and an equity risk premium of 6%, the index value that you obtain is about 2133, about 20.7% below March 2nd levels.

Download spreadsheetThe Growth Engine Revs Up: In this telling, it is real growth in the US economy that surges, creating tailwinds for growth in the rest of the world. That higher real growth rate, while pushing up earnings growth for US companies (to 8% for the near term), will also increase treasury bond rates (to 3.5%), as in the inflation story, but unlike it, equity risk premiums will drift back to pre-2008 levels (closer to 4.5%). The index value that you obtain is about 3031, about 12.7% above March 2nd levels.

Download spreadsheetThe Growth Engine Revs Up: In this telling, it is real growth in the US economy that surges, creating tailwinds for growth in the rest of the world. That higher real growth rate, while pushing up earnings growth for US companies (to 8% for the near term), will also increase treasury bond rates (to 3.5%), as in the inflation story, but unlike it, equity risk premiums will drift back to pre-2008 levels (closer to 4.5%). The index value that you obtain is about 3031, about 12.7% above March 2nd levels.

Download spreadsheetA Melded Version: I believe in a melded version of these stories, where inflation returns (but stays around 2%) and real growth in the economy increases, but only moderately. That will translate into higher treasury bond rates (my guess would be 3.5%), with a proportionate increase in earnings growth (at least in steady state) and an equity risk premium of 5%, splitting the difference between pre-crisis and post-crisis periods. The index value that I obtain, with these assumptions, is about 2610, about 3.1% below March 2nd levels.

Download spreadsheetA Melded Version: I believe in a melded version of these stories, where inflation returns (but stays around 2%) and real growth in the economy increases, but only moderately. That will translate into higher treasury bond rates (my guess would be 3.5%), with a proportionate increase in earnings growth (at least in steady state) and an equity risk premium of 5%, splitting the difference between pre-crisis and post-crisis periods. The index value that I obtain, with these assumptions, is about 2610, about 3.1% below March 2nd levels.

Download spreadsheetYou can see, even from this limited list of scenarios, that to assess how stock prices will move, as interest rates change, you have to also make a judgment on why interest rates are moving. An inflation-driven increase in interest rates is net negative for stocks, but a real-growth driven increase in interest rates is a net positive. In fact, the scenario where interest rates go down sees a much bigger drop in value than two of three scenarios, where interest rates rise.

Download spreadsheetYou can see, even from this limited list of scenarios, that to assess how stock prices will move, as interest rates change, you have to also make a judgment on why interest rates are moving. An inflation-driven increase in interest rates is net negative for stocks, but a real-growth driven increase in interest rates is a net positive. In fact, the scenario where interest rates go down sees a much bigger drop in value than two of three scenarios, where interest rates rise. The Bottom LineWhen macro economic fundamentals change, markets take time to adjust, translating into market volatility. During these adjustment periods, you will hear a great deal of market punditry and much of it will be half baked, with the advisor or analyst focusing on one piece of the valuation puzzle and holding all else constant. Thus, you will read predictions about how much the market will drop if treasury bond rates rise to 4.5% or how much it will rise if earnings growth is 10%. I hope that this post has given you tools that you can use to fill in the rest of the story, since it is possible that stocks could actually go up, even if rates go up to 4.5%, if that rate rise is precipitated by a strong economy, and that stocks could be hurt with 10% earnings growth, if that growth comes mostly from high inflation. I also hope that, after you have listened to the narratives offered by others, for what markets will or will not do, that you start developing your own narrative for the market, as the basis for your investment decisions. You've seen my narrative, but I will leave the feedback loop open, as fresh data on inflation and growth comes in, and I plan to revisit my narrative, tweaking, adjusting or even abandoning it, if the data leads me to.

YouTube Video

Data LinksT.Bond Rates, Inflation and Real GDP Growth - 1954-2017Fed Funds Rate and Treasury Rates - 1962-2017T.Bond Rates, Earnings Growth Rates and ERP - 1961- 2017Spreadsheet LinksIntrinsic Valuation Spreadsheet for S&P 500More of the Same: SpreadsheetThe Return of Inflation: SpreadsheetThe Growth Engine Revs Up: SpreadsheetThe Melded Version: SpreadsheetBlog Post LinksTesting Times: Market Turmoil and Investment Serenity

Published on March 02, 2018 15:38

February 10, 2018

Testing Times: Market Turmoil and Investment Serenity

The last week has been a roller coaster ride, though more down than up, and investors have done what they always do during market crises. The fear factor rises, some investors sell and head for the safer pastures, some are paralyzed not knowing what to do, and some double down as contrarians, buying into the sell off. In the last week, I found myself drawn to each of three camps, often at different points in the same day, as the market went through wild mood swings. These are my most vulnerable moments as an investor, since good sense is replaced by "animal spirits", and I feel the urge to abandon everything I know about investing, and go with my gut, never a good idea. I know that I have to step back from the action, regain perspective and return to what works for me in markets, and it is for that reason that I find myself going through the same sequence, each time I face a market crisis.

Step 1: Assess the damage and regain perspectiveThe first casualty in a crisis is perspective, as drawn into the news of the day, we tend to lose any sense of proportion. The last week has been an awful week for stocks, with many major indices down by 10% since last Thursday. If your initial investment in stocks was on February 1, 2018, I feel for you, because the pain has no salve, but most of us have had money in stocks for a lot longer than a week. In the table below, I look at the change in the S&P 500 last week and then compare it to the changes since the start of the year (which was less than 6 weeks ago) to a year ago and to ten years ago.

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

2/1/082/1/171/1/182/1/18S&P 500 on date1355227926742822S&P 500 on 2/8/182581258125812581% Change90.48%13.25%-3.48%-8.54%I know that this is small consolation, but if you have been invested in stocks since the start of the year, your portfolio is down, but by less than 3.5%. If you have been invested a year, you are still ahead by 13.25%, even after last week, and if you've been in stocks, since February 2008, you've not only lived through an even bigger market crisis (with the S&P 500 down 38% between September 2008 and March 2009), but you have seen your portfolio climb 90.48% over the entire period, and that does not even include dividends. That is why when confronted by perpetual bears, with their "I told you so" warnings, I try to remember that most of them have been bearish since time immemorial.

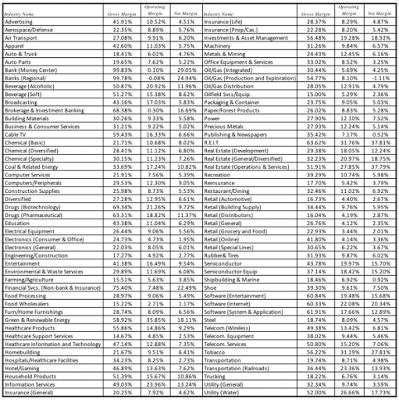

Returning the focus to the last week, let's first look across sectors to see which ones were punished the most and which ones endured. Using the S&P classification for sectors, here is how the sectors performed between February 2, 2018 and February 9, 2018;

Not surprisingly, every sector had a down week, though energy stocks did worse than the rest of the market, with an oil price drop adding to the pain. Continuing to look at equities, let's now look geographically at returns in different markets over the last week.

Not surprisingly, every sector had a down week, though energy stocks did worse than the rest of the market, with an oil price drop adding to the pain. Continuing to look at equities, let's now look geographically at returns in different markets over the last week.

While the S&P 500 had a particularly bad week, the rest of the world felt the pain, with only one index (Colombo, Sri Lanka) on the WSJ international index list showing positive returns for the week. In fact, Asia presents a dichotomy, with the larger markets (China, Japan) among the worst hit and the smaller markets in South Asia (Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and Philippines) showing up on the least affected list.

While the S&P 500 had a particularly bad week, the rest of the world felt the pain, with only one index (Colombo, Sri Lanka) on the WSJ international index list showing positive returns for the week. In fact, Asia presents a dichotomy, with the larger markets (China, Japan) among the worst hit and the smaller markets in South Asia (Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and Philippines) showing up on the least affected list.

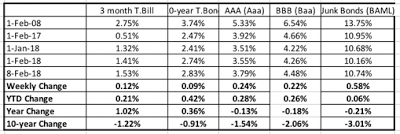

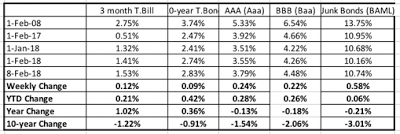

While equities have felt the bulk of the pain, it is interest rates that have been labeled as the source of this market meltdown, and the graph below captures the change in treasury rates and corporate bonds in different ratings classes (AAA, BBB and Junk) over the last week and the last year: The treasury bond rate rose slightly over the week, at odds with what you usually see in big stock market sell offs, when the flight to safety usually pushes rates down. The increases in default spreads, reflected in the jumps in interest rates increasing with lower ratings, is consistent with a story of a increased risk aversion. Here again, taking a look across a longer time period does provide additional information, with treasury rates at significantly higher levels than a year ago, with a flattening of the yield curve. In summary, this has been an awful week for stocks, across sectors and geographies, and only a mildly bad week for bonds. Looking over the last year, it is bonds that have suffered a bad year, while stocks have done well. That said, the rates that we see on treasuries today are more in keeping with a healthy, growing economy than the rates we saw a year ago.

The treasury bond rate rose slightly over the week, at odds with what you usually see in big stock market sell offs, when the flight to safety usually pushes rates down. The increases in default spreads, reflected in the jumps in interest rates increasing with lower ratings, is consistent with a story of a increased risk aversion. Here again, taking a look across a longer time period does provide additional information, with treasury rates at significantly higher levels than a year ago, with a flattening of the yield curve. In summary, this has been an awful week for stocks, across sectors and geographies, and only a mildly bad week for bonds. Looking over the last year, it is bonds that have suffered a bad year, while stocks have done well. That said, the rates that we see on treasuries today are more in keeping with a healthy, growing economy than the rates we saw a year ago.

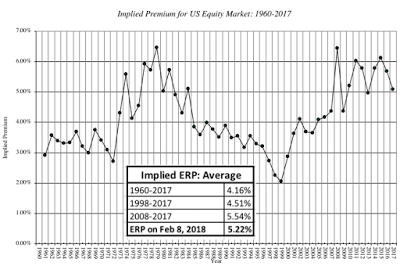

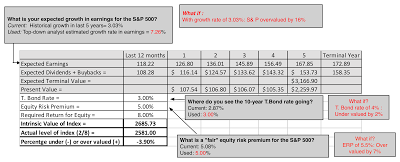

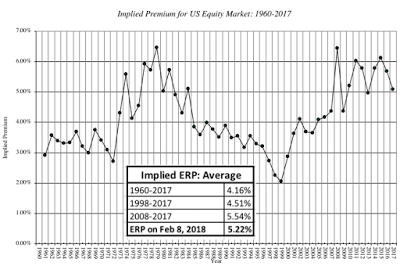

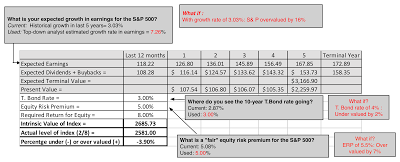

Step 2: Read the tea leavesIt is natural that when faced with large market moves, we look for logical and rational explanations. It is in keeping then that the last week has been full of analysis of the causes and consequences of this market correction. As I see it, there are three possible explanations for any market meltdown over a short period, like this one:Market Meltdowns: Reasons, Symptoms and Consequences Explanation Symptoms Market Consequences Panic Attack Sharp movements in stock prices for no discernible reasons, with surge in fear indices. Market drops sharply, but quickly recovers back most or all of its losses as panic subsides Fundamentals Event or news that causes expected cash flows, growth or perceived risk in equities to change significantly. Market drops sharply and stays down, with price moves tied to the fundamental(s) in focus. Repricing of Risk Event or news that leads to repricing of risk (in the form of equity risk premiums or default spreads). As price of risk is reassessed upwards, market drops until the price of risk finds its new equilibrium. The question in any meltdown is which explanation dominates, since stock market crisis has elements of all three. As I look at what's happened over the last week, I would argue that it was triggered by a fundamental (interest rates rising) leading to a repricing of risk (equity risk premiums going up) and to momentum & fear driven selling. The Fundamentals Trigger: This avalanche of selling was started last Friday (February 1, 2018) by a US unemployment report that contained mostly good news, with 200,000 new jobs created, a continuation of a long string of positive jobs reports. Included in the report, though, was a finding that wages increased 2.9% for US workers, at odds with the mostly flat wage growth over the last decade. That higher wage growth has both positive and negative connotations for stock fundamentals, providing a basis for strong earnings growth at US companies that is built on more than tax cuts, while also sowing the seeds for higher inflation and interest rates, which will make that future growth less valuable. The Repricing of Equity Risk: That expectation of higher interest rates and inflation seems to have caused equity investors to reprice risk by charging higher equity risk premiums, which can be chronicled in a forward-looking estimate of an implied ERP. I last updated that number on January 31, 2018, and I have estimated that premium, by day, over the five trading days between February 1 and February 8, 2018. There is little change in the growth rates and base cash flows, as you go from day to day, partly because neither is updated as frequently as interest rates and stock prices, but holding those numbers, the estimated equity risk premium has increased over the last week from 4.78% at the start of trading on February 1, 2018 to 5.22% at the close of trading on February 8, 2018. Implied ERP, by Day: January 31, 2018 (Close) to February 8, 2018 (Close) Date (Close) S&P 500 T.Bond Rate Implied ERP Link to spreadsheet 31-Jan-18 2823.81 2.74% 4.78% ERP, Jan 31 1-Feb-18 2821.98 2.77% 4.78% ERP, Feb 1 2-Feb-18 2762.13 2.85% 4.88% ERP, Feb 2 5-Feb-18 2648.94 2.79% 5.09% ERP, Feb 5 6-Feb-18 2695.14 2.77% 5.00% ERP, Feb 6 7-Feb-18 2681.66 2.84% 5.02% ERP, Feb 7 8-Feb-18 2581.00 2.83% 5.22% ERP, Feb 8 The Panic Response: Most market players don't buy or sell stocks on fundamentals or actively think about the price of equity risk. Instead, some of them trade, trying to take advantage of shifts in market mood and momentum, and for those traders, the momentum shift in markets is the only reason that they need, to go from being stock buyers to sellers. Others have to sell because their financial positions are imperiled, either because they borrowed money to buy stocks or because they fear irreparable damage to their retirement or savings portfolios. The rise in the volatility indices are a clear indicator of this panic response, with the VIX almost tripling in the course of the week. Just in case you feel the urge to blame millennials, with robo-advisors, for the panic selling, they seem to be staying on the side lines for the most part, and it is the usual culprits, "professional" money managers, that are most panicked of all.At this point, you are probably confused about where to go next. If you are trying to make that judgment, you have to find answers to three questions:Where are interest rates headed? There has been a disconnect between the equity and the bond market, since the 2016 US presidential election, with the equity markets consistently pricing in more optimistic forecasts for the US economy, than the bond markets. Stocks prices rose on the expectation that tax cuts and more robust economic growth, but bond markets were more subdued with rates continuing to stay at the 2.25%-2.5% range that we have seen for much of the last decade. As I noted in my post at the start of this year on equity markets, the gap between the US 10-year T.Bond rate and an intrinsic measure of that rate, computed by adding inflation to real GDP growth, has widened to it's highest level in the last decade. The advent of the new year seems to have caused the bond market to notice this gap, and rates have risen since. If you are optimistic about the US economy and wary about inflation, there is more room for rates to rise, with or without the Fed's active intervention.Is the ERP high enough? Is the repricing of equity risk over? The answer depends upon whether you believe the numbers that underlie my estimates, and if you do, whether you think 5.22% is a sufficient premium for investing in equities. The only way to address that question is to examine it in the context of history, which is what I have done in the picture below: Download historical ERP dataWith all the caveats about the numbers that underlie this graph in place, note that the premium is now solidly in the middle of the distribution. There is always the possibility that the earnings growth estimates that back it up are wrong, but if they are, the interest rate rise that scares markets will also be reversed.When will the panic end? I don't know the answer to the question but I do know that it rests less on economics and more on psychology. There will be a moment, perhaps early next week or in two weeks or in two months, where the fever will pass and the momentum will shift. If you are a trader, you can get rich playing this game, if you play it well, or poor in a hurry, if you play it badly. I choose not to play it all.Is there a way that we can bring this all together into a judgment call in the market. I think so and I will use the same framework that I used for my implied equity risk premium to make my assessment. You will need three numbers, an expected growth rate in earnings for the S&P 500, you estimate of where the 10-year treasury bond rate will end up and what you think is a fair equity risk premium for the S&P 500. For instance, if you accept the analyst forecasted growth in earnings of 7.26% for the next five years as a reasonable estimate, that the the T.Bond rate will settle in at about 3.0% and that 5.0% is a fair value for the equity risk premium, your estimate of value for the S&P 500 is below:

Download historical ERP dataWith all the caveats about the numbers that underlie this graph in place, note that the premium is now solidly in the middle of the distribution. There is always the possibility that the earnings growth estimates that back it up are wrong, but if they are, the interest rate rise that scares markets will also be reversed.When will the panic end? I don't know the answer to the question but I do know that it rests less on economics and more on psychology. There will be a moment, perhaps early next week or in two weeks or in two months, where the fever will pass and the momentum will shift. If you are a trader, you can get rich playing this game, if you play it well, or poor in a hurry, if you play it badly. I choose not to play it all.Is there a way that we can bring this all together into a judgment call in the market. I think so and I will use the same framework that I used for my implied equity risk premium to make my assessment. You will need three numbers, an expected growth rate in earnings for the S&P 500, you estimate of where the 10-year treasury bond rate will end up and what you think is a fair equity risk premium for the S&P 500. For instance, if you accept the analyst forecasted growth in earnings of 7.26% for the next five years as a reasonable estimate, that the the T.Bond rate will settle in at about 3.0% and that 5.0% is a fair value for the equity risk premium, your estimate of value for the S&P 500 is below:

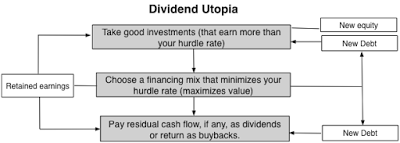

Download spreadsheetWith these estimates, you should be okay with how the market is valuing equities at the close of trading February 8, 2018; it is slightly under valued at 3.90%. To provide a contrast, if you feel that analysts are over estimating the impact of the tax cuts and that the historical earnings growth rate over the last decade (about 3.03%) is a more appropriate forecast for future growth, holding the risk free rate and ERP at 3% and 5% respectively, the value you will get for the index is 2233, about 16% below the index level of February 8, 2018. If you want put in your own estimates of earnings growth, T.Bond rates and equity risk premiums, please download this spreadsheet. In fact, if you are inclined to share your estimates with a group, I have created a shared google spreadsheet for the S&P 500. Let's see what we can get as a crowd valuation.

Download spreadsheetWith these estimates, you should be okay with how the market is valuing equities at the close of trading February 8, 2018; it is slightly under valued at 3.90%. To provide a contrast, if you feel that analysts are over estimating the impact of the tax cuts and that the historical earnings growth rate over the last decade (about 3.03%) is a more appropriate forecast for future growth, holding the risk free rate and ERP at 3% and 5% respectively, the value you will get for the index is 2233, about 16% below the index level of February 8, 2018. If you want put in your own estimates of earnings growth, T.Bond rates and equity risk premiums, please download this spreadsheet. In fact, if you are inclined to share your estimates with a group, I have created a shared google spreadsheet for the S&P 500. Let's see what we can get as a crowd valuation.

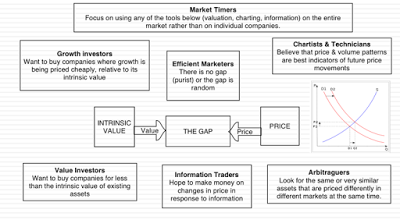

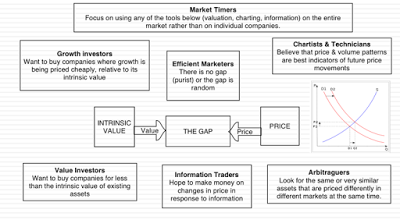

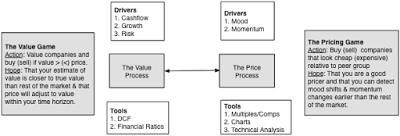

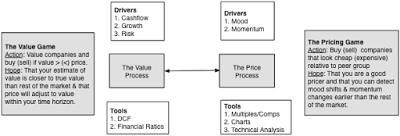

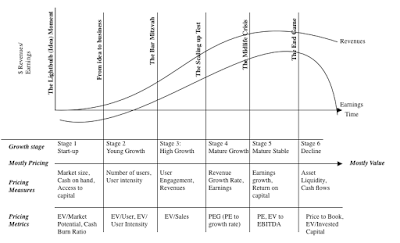

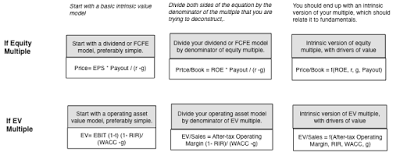

Step 3: Review your investment philosophyI firmly believe that to be a successful investor, you need a core investment philosophy, a set of beliefs of not just how markets work but who you are as a person, and you need to stay true to that philosophy. It is the one common ingredient that you see across successful investors, whether they succeed as pure traders, growth investors or value investors. The best way that I can think of presenting the different choices you have on investment philosophies is by using my value/price contrast: To the question of which of these is the best philosophy, my answer is that there while there is one philosophy that is best for you, there is no one philosophy that is best for all investors. The key to finding that "best" philosophy is to find what makes you tick, as an individual and an investor, not what makes Warren Buffett successful.

To the question of which of these is the best philosophy, my answer is that there while there is one philosophy that is best for you, there is no one philosophy that is best for all investors. The key to finding that "best" philosophy is to find what makes you tick, as an individual and an investor, not what makes Warren Buffett successful.

I see myself as an investor, not a trader, and that given my tool kit and personality, what works for me is to be a investor grounded in value, though my use of a more expansive definition of value than old-time value investors, allows me to buy both growth stocks and value stocks. I am not a market timer for two reasons.

First, the overall market has too many variables feeding into it that I do not control and cannot forecast, making my valuations inherently too noisy to be useful. Second, I see little that I bring to the overall market in terms of tools or information that will give me an edge over others. The truest test of whether you have a solid investment philosophy is a week like the last one, where you will be tempted to or panicked into abandoning everything that you believe about markets. I would lying if I said that I have not been tempted in the last week to time markets, either because of fear (driving me to sell) or hubris (where I want to play market contrarian), but so far, I have been able to hold out.

Step 4: Act consistently

During every market crisis, you will be tempted to look and ask that ever present question of "What if?", where you think about all of the money you could have saved, if only you had sold last Thursday. Not only is this pointless, unless you have mastered time travel, but it can be damaging to your future returns, as your regrets about past actions taken and not taken play out in new actions that you take. My suggestion is that you return to your core investment philosophy and start to think about the actions that you can take on Monday, when the market opens, that would be consistent with that philosophy. I am taking my own suggestion to heart and have started revisiting the list of companies that I would love to invest in (like Amazon, Netflix and Tesla), but have been priced out of my reach, in the hope that the correction will put some of them into play. More painfully, I have been revaluing every single company in my existing portfolio, with the intent of shedding those that are now over valued, even if they have done well for me. If nothing else, this will keep me busy and perhaps stop me from being caught up in the market frenzy!

YouTube Video

Spreadsheets

S&P 500 Intrinsic Value SpreadsheetGoogle Shared Spreadsheet of Intrinsic Valuations

Step 1: Assess the damage and regain perspectiveThe first casualty in a crisis is perspective, as drawn into the news of the day, we tend to lose any sense of proportion. The last week has been an awful week for stocks, with many major indices down by 10% since last Thursday. If your initial investment in stocks was on February 1, 2018, I feel for you, because the pain has no salve, but most of us have had money in stocks for a lot longer than a week. In the table below, I look at the change in the S&P 500 last week and then compare it to the changes since the start of the year (which was less than 6 weeks ago) to a year ago and to ten years ago.

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

2/1/082/1/171/1/182/1/18S&P 500 on date1355227926742822S&P 500 on 2/8/182581258125812581% Change90.48%13.25%-3.48%-8.54%I know that this is small consolation, but if you have been invested in stocks since the start of the year, your portfolio is down, but by less than 3.5%. If you have been invested a year, you are still ahead by 13.25%, even after last week, and if you've been in stocks, since February 2008, you've not only lived through an even bigger market crisis (with the S&P 500 down 38% between September 2008 and March 2009), but you have seen your portfolio climb 90.48% over the entire period, and that does not even include dividends. That is why when confronted by perpetual bears, with their "I told you so" warnings, I try to remember that most of them have been bearish since time immemorial.

Returning the focus to the last week, let's first look across sectors to see which ones were punished the most and which ones endured. Using the S&P classification for sectors, here is how the sectors performed between February 2, 2018 and February 9, 2018;

Not surprisingly, every sector had a down week, though energy stocks did worse than the rest of the market, with an oil price drop adding to the pain. Continuing to look at equities, let's now look geographically at returns in different markets over the last week.

Not surprisingly, every sector had a down week, though energy stocks did worse than the rest of the market, with an oil price drop adding to the pain. Continuing to look at equities, let's now look geographically at returns in different markets over the last week. While the S&P 500 had a particularly bad week, the rest of the world felt the pain, with only one index (Colombo, Sri Lanka) on the WSJ international index list showing positive returns for the week. In fact, Asia presents a dichotomy, with the larger markets (China, Japan) among the worst hit and the smaller markets in South Asia (Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and Philippines) showing up on the least affected list.

While the S&P 500 had a particularly bad week, the rest of the world felt the pain, with only one index (Colombo, Sri Lanka) on the WSJ international index list showing positive returns for the week. In fact, Asia presents a dichotomy, with the larger markets (China, Japan) among the worst hit and the smaller markets in South Asia (Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and Philippines) showing up on the least affected list. While equities have felt the bulk of the pain, it is interest rates that have been labeled as the source of this market meltdown, and the graph below captures the change in treasury rates and corporate bonds in different ratings classes (AAA, BBB and Junk) over the last week and the last year:

The treasury bond rate rose slightly over the week, at odds with what you usually see in big stock market sell offs, when the flight to safety usually pushes rates down. The increases in default spreads, reflected in the jumps in interest rates increasing with lower ratings, is consistent with a story of a increased risk aversion. Here again, taking a look across a longer time period does provide additional information, with treasury rates at significantly higher levels than a year ago, with a flattening of the yield curve. In summary, this has been an awful week for stocks, across sectors and geographies, and only a mildly bad week for bonds. Looking over the last year, it is bonds that have suffered a bad year, while stocks have done well. That said, the rates that we see on treasuries today are more in keeping with a healthy, growing economy than the rates we saw a year ago.

The treasury bond rate rose slightly over the week, at odds with what you usually see in big stock market sell offs, when the flight to safety usually pushes rates down. The increases in default spreads, reflected in the jumps in interest rates increasing with lower ratings, is consistent with a story of a increased risk aversion. Here again, taking a look across a longer time period does provide additional information, with treasury rates at significantly higher levels than a year ago, with a flattening of the yield curve. In summary, this has been an awful week for stocks, across sectors and geographies, and only a mildly bad week for bonds. Looking over the last year, it is bonds that have suffered a bad year, while stocks have done well. That said, the rates that we see on treasuries today are more in keeping with a healthy, growing economy than the rates we saw a year ago.Step 2: Read the tea leavesIt is natural that when faced with large market moves, we look for logical and rational explanations. It is in keeping then that the last week has been full of analysis of the causes and consequences of this market correction. As I see it, there are three possible explanations for any market meltdown over a short period, like this one:Market Meltdowns: Reasons, Symptoms and Consequences Explanation Symptoms Market Consequences Panic Attack Sharp movements in stock prices for no discernible reasons, with surge in fear indices. Market drops sharply, but quickly recovers back most or all of its losses as panic subsides Fundamentals Event or news that causes expected cash flows, growth or perceived risk in equities to change significantly. Market drops sharply and stays down, with price moves tied to the fundamental(s) in focus. Repricing of Risk Event or news that leads to repricing of risk (in the form of equity risk premiums or default spreads). As price of risk is reassessed upwards, market drops until the price of risk finds its new equilibrium. The question in any meltdown is which explanation dominates, since stock market crisis has elements of all three. As I look at what's happened over the last week, I would argue that it was triggered by a fundamental (interest rates rising) leading to a repricing of risk (equity risk premiums going up) and to momentum & fear driven selling. The Fundamentals Trigger: This avalanche of selling was started last Friday (February 1, 2018) by a US unemployment report that contained mostly good news, with 200,000 new jobs created, a continuation of a long string of positive jobs reports. Included in the report, though, was a finding that wages increased 2.9% for US workers, at odds with the mostly flat wage growth over the last decade. That higher wage growth has both positive and negative connotations for stock fundamentals, providing a basis for strong earnings growth at US companies that is built on more than tax cuts, while also sowing the seeds for higher inflation and interest rates, which will make that future growth less valuable. The Repricing of Equity Risk: That expectation of higher interest rates and inflation seems to have caused equity investors to reprice risk by charging higher equity risk premiums, which can be chronicled in a forward-looking estimate of an implied ERP. I last updated that number on January 31, 2018, and I have estimated that premium, by day, over the five trading days between February 1 and February 8, 2018. There is little change in the growth rates and base cash flows, as you go from day to day, partly because neither is updated as frequently as interest rates and stock prices, but holding those numbers, the estimated equity risk premium has increased over the last week from 4.78% at the start of trading on February 1, 2018 to 5.22% at the close of trading on February 8, 2018. Implied ERP, by Day: January 31, 2018 (Close) to February 8, 2018 (Close) Date (Close) S&P 500 T.Bond Rate Implied ERP Link to spreadsheet 31-Jan-18 2823.81 2.74% 4.78% ERP, Jan 31 1-Feb-18 2821.98 2.77% 4.78% ERP, Feb 1 2-Feb-18 2762.13 2.85% 4.88% ERP, Feb 2 5-Feb-18 2648.94 2.79% 5.09% ERP, Feb 5 6-Feb-18 2695.14 2.77% 5.00% ERP, Feb 6 7-Feb-18 2681.66 2.84% 5.02% ERP, Feb 7 8-Feb-18 2581.00 2.83% 5.22% ERP, Feb 8 The Panic Response: Most market players don't buy or sell stocks on fundamentals or actively think about the price of equity risk. Instead, some of them trade, trying to take advantage of shifts in market mood and momentum, and for those traders, the momentum shift in markets is the only reason that they need, to go from being stock buyers to sellers. Others have to sell because their financial positions are imperiled, either because they borrowed money to buy stocks or because they fear irreparable damage to their retirement or savings portfolios. The rise in the volatility indices are a clear indicator of this panic response, with the VIX almost tripling in the course of the week. Just in case you feel the urge to blame millennials, with robo-advisors, for the panic selling, they seem to be staying on the side lines for the most part, and it is the usual culprits, "professional" money managers, that are most panicked of all.At this point, you are probably confused about where to go next. If you are trying to make that judgment, you have to find answers to three questions:Where are interest rates headed? There has been a disconnect between the equity and the bond market, since the 2016 US presidential election, with the equity markets consistently pricing in more optimistic forecasts for the US economy, than the bond markets. Stocks prices rose on the expectation that tax cuts and more robust economic growth, but bond markets were more subdued with rates continuing to stay at the 2.25%-2.5% range that we have seen for much of the last decade. As I noted in my post at the start of this year on equity markets, the gap between the US 10-year T.Bond rate and an intrinsic measure of that rate, computed by adding inflation to real GDP growth, has widened to it's highest level in the last decade. The advent of the new year seems to have caused the bond market to notice this gap, and rates have risen since. If you are optimistic about the US economy and wary about inflation, there is more room for rates to rise, with or without the Fed's active intervention.Is the ERP high enough? Is the repricing of equity risk over? The answer depends upon whether you believe the numbers that underlie my estimates, and if you do, whether you think 5.22% is a sufficient premium for investing in equities. The only way to address that question is to examine it in the context of history, which is what I have done in the picture below:

Download historical ERP dataWith all the caveats about the numbers that underlie this graph in place, note that the premium is now solidly in the middle of the distribution. There is always the possibility that the earnings growth estimates that back it up are wrong, but if they are, the interest rate rise that scares markets will also be reversed.When will the panic end? I don't know the answer to the question but I do know that it rests less on economics and more on psychology. There will be a moment, perhaps early next week or in two weeks or in two months, where the fever will pass and the momentum will shift. If you are a trader, you can get rich playing this game, if you play it well, or poor in a hurry, if you play it badly. I choose not to play it all.Is there a way that we can bring this all together into a judgment call in the market. I think so and I will use the same framework that I used for my implied equity risk premium to make my assessment. You will need three numbers, an expected growth rate in earnings for the S&P 500, you estimate of where the 10-year treasury bond rate will end up and what you think is a fair equity risk premium for the S&P 500. For instance, if you accept the analyst forecasted growth in earnings of 7.26% for the next five years as a reasonable estimate, that the the T.Bond rate will settle in at about 3.0% and that 5.0% is a fair value for the equity risk premium, your estimate of value for the S&P 500 is below:

Download historical ERP dataWith all the caveats about the numbers that underlie this graph in place, note that the premium is now solidly in the middle of the distribution. There is always the possibility that the earnings growth estimates that back it up are wrong, but if they are, the interest rate rise that scares markets will also be reversed.When will the panic end? I don't know the answer to the question but I do know that it rests less on economics and more on psychology. There will be a moment, perhaps early next week or in two weeks or in two months, where the fever will pass and the momentum will shift. If you are a trader, you can get rich playing this game, if you play it well, or poor in a hurry, if you play it badly. I choose not to play it all.Is there a way that we can bring this all together into a judgment call in the market. I think so and I will use the same framework that I used for my implied equity risk premium to make my assessment. You will need three numbers, an expected growth rate in earnings for the S&P 500, you estimate of where the 10-year treasury bond rate will end up and what you think is a fair equity risk premium for the S&P 500. For instance, if you accept the analyst forecasted growth in earnings of 7.26% for the next five years as a reasonable estimate, that the the T.Bond rate will settle in at about 3.0% and that 5.0% is a fair value for the equity risk premium, your estimate of value for the S&P 500 is below: Download spreadsheetWith these estimates, you should be okay with how the market is valuing equities at the close of trading February 8, 2018; it is slightly under valued at 3.90%. To provide a contrast, if you feel that analysts are over estimating the impact of the tax cuts and that the historical earnings growth rate over the last decade (about 3.03%) is a more appropriate forecast for future growth, holding the risk free rate and ERP at 3% and 5% respectively, the value you will get for the index is 2233, about 16% below the index level of February 8, 2018. If you want put in your own estimates of earnings growth, T.Bond rates and equity risk premiums, please download this spreadsheet. In fact, if you are inclined to share your estimates with a group, I have created a shared google spreadsheet for the S&P 500. Let's see what we can get as a crowd valuation.

Download spreadsheetWith these estimates, you should be okay with how the market is valuing equities at the close of trading February 8, 2018; it is slightly under valued at 3.90%. To provide a contrast, if you feel that analysts are over estimating the impact of the tax cuts and that the historical earnings growth rate over the last decade (about 3.03%) is a more appropriate forecast for future growth, holding the risk free rate and ERP at 3% and 5% respectively, the value you will get for the index is 2233, about 16% below the index level of February 8, 2018. If you want put in your own estimates of earnings growth, T.Bond rates and equity risk premiums, please download this spreadsheet. In fact, if you are inclined to share your estimates with a group, I have created a shared google spreadsheet for the S&P 500. Let's see what we can get as a crowd valuation.Step 3: Review your investment philosophyI firmly believe that to be a successful investor, you need a core investment philosophy, a set of beliefs of not just how markets work but who you are as a person, and you need to stay true to that philosophy. It is the one common ingredient that you see across successful investors, whether they succeed as pure traders, growth investors or value investors. The best way that I can think of presenting the different choices you have on investment philosophies is by using my value/price contrast:

To the question of which of these is the best philosophy, my answer is that there while there is one philosophy that is best for you, there is no one philosophy that is best for all investors. The key to finding that "best" philosophy is to find what makes you tick, as an individual and an investor, not what makes Warren Buffett successful.

To the question of which of these is the best philosophy, my answer is that there while there is one philosophy that is best for you, there is no one philosophy that is best for all investors. The key to finding that "best" philosophy is to find what makes you tick, as an individual and an investor, not what makes Warren Buffett successful.I see myself as an investor, not a trader, and that given my tool kit and personality, what works for me is to be a investor grounded in value, though my use of a more expansive definition of value than old-time value investors, allows me to buy both growth stocks and value stocks. I am not a market timer for two reasons.

First, the overall market has too many variables feeding into it that I do not control and cannot forecast, making my valuations inherently too noisy to be useful. Second, I see little that I bring to the overall market in terms of tools or information that will give me an edge over others. The truest test of whether you have a solid investment philosophy is a week like the last one, where you will be tempted to or panicked into abandoning everything that you believe about markets. I would lying if I said that I have not been tempted in the last week to time markets, either because of fear (driving me to sell) or hubris (where I want to play market contrarian), but so far, I have been able to hold out.

Step 4: Act consistently