Aswath Damodaran's Blog

August 5, 2025

The Imitation Game: Defending against AI's Dark Side!

An Easy Target?

In a post last year, I talked about a bot in my name, that was in development phase at NYU, and while officially sanctioned, it did open up existential challenges for me. In discussing that bot, I noted that this bot had accessed everything that I had ever written, talked about or valued in my lifetime, and that I had facilitated its path by making that access easy. I will explain my rationale for the open access, and provide you with the links if you want to get to them, hoping to pre-empt those who will try to charge you for that content.

My Open Access Policy

I have said this before, but there is no harm in saying it again, but I am a teacher, first and foremost, and almost every choice I make in my profession life reflects that mindset. A teacher, like an actor or singer, craves an audience, and the larger and more enthusiastic that audience, the better. When I started teaching in 1986, my audience was restricted to those in my physical classroom at NYU's business school, and my initial attempts at expanding that audience were very limited. I had video recorders set up to record my lectures, made three copies of each lecture tape, and put them on the shelves at NYU's library for patrons to check out and watch. The internet, for all of its sins, changed the game for me, allowing me to share not only class materials (slides, exams) but also my lecture videos, in online formats. Though my early attempts to make these conversions were primitive, the technology for recording classes and putting them online has made a quantum leap. In spring 2025, every one of my NYU classes was recorded by cameras that are built into classroom, the conversions to online videos happened in minutes, right after the class is done, and YouTube has been a game changer, in allowing access to anyone with an internet connection anywhere in the world.

As the internet has expanded its reach, and social media platforms have joined the mix, I have also shared the other components that go into my classes more widely, starting with the data on industry averages that I need and use in my own valuations, the spreadsheets that contain these valuations and blog posts on markets and companies and any other tools that I use in my own analyses. While I am happy to receive compliments for the sharing and praise for being unselfish, the truth is that my sharing is driven less by altruism (I am no Mother Theresa!) and more by two other forces. The first is that, as I noted in my post on country equity risk premiums last week, there much of what I know or write about is pedestrian, and holding it in secret seems silly. The second is that, while I am not easily outraged, I am driven to outrage by business consultants and experts who state the obvious (replacing words you know with buzzwords and acronyms), while making outrageous claims of what they can deliver and charging their customers absurd amounts for their advice and appraisals. If I can save even a few of these customers from making these payments, I consider it to be a win.

My Sharing Spots

Everything that I have ever written, worked on or taught is somewhere online, almost always with no protective shields (no passwords or subscriptions), and there are four places where you can find them:

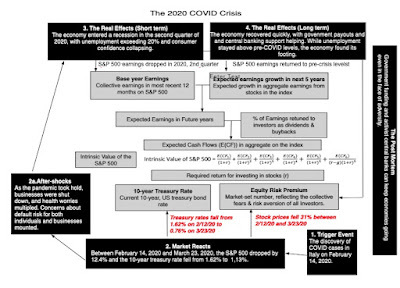

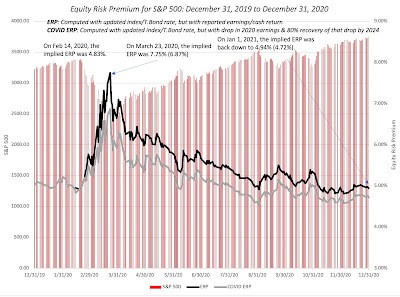

Webpage: The oldest platform for my content remains my webpage, damodaran.com, and while it can be creaky, and difficult to navigate, it contains the links to my writing, teaching, data, spreadsheets and other tools. Teaching: I teach two classes at Stern, corporate finance and valuation, and have four other classes - a lead-into-valuation accounting class, a made-for-finance statistics class, a class on investment philosophies and one on corporate life cycles, and I described these classes in a post on teaching at the start of 2025. You can find them all by going to the teaching link on my webpage, https://people.stern.nyu.edu/adamodar/New_Home_Page/teaching.html including my regular classes (class material, lecture notes, exams and quizzes and webcasts of the classes) in real time, as well as archived versions from previous semesters. In addition, the online classes are at the same link, with material, post- class tests and webcasts of sessions for each class. This is also the place where you can find links to seminars that I teach in the rest of the world, with slides and materials that I used for those classes (though I have been tardy about updating these).Data: At the start of every year for the last three decades, I have shared my analysis of data on publicly traded companies, breaking down the data into corporate finance and valuation categories. This link, https://people.stern.nyu.edu/adamodar/New_Home_Page/data.html, will take you to the entry page, and you can then either access the most recent data (from the start of 2025, since I update only once a year, for most datasets) or archived data (from previous years). My raw data comes from a variety of sources, and in the interests of not stepping on the toes of my data providers, my data usually reflects industry averages, rather than company-specific data, but it does include regional breakdowns: US, Europe, Emerging Markets (with India and China broken out individually, Australia & Canada & New Zealand) and Japan. Spreadsheets: I am not an Excel ninja, and while my spreadsheet-building skills are adequate, my capacity to make them look polished is limited. I do share the spreadsheets that I use in my classes and work here, with my most-used (by me) spreadsheet being one that I use to value most companies at this link, with a webcast explaining its usage.Books: I have written eleven books and co-edited one, spread out across corporate finance, valuation and investing, and you can find them all listed here. Many of these books are in their third or fourth editions, but with each one, you should find a webpage that contains supplementary material for that book or edition (slides, answers to questions at the end of each chapter, data, spreadsheets backing the examples). This is the only section of the spreadsheet where you may encounter a gatekeeper, asking you for a password, and only if you seek access to instructor material. If you are wondering what is behind the gate, it is only the powerpoint slides, with my notes on each slide, but the pdf versions of these slides should be somewhere on the same page, without need for a password.Papers: I don't much care much for academic research, but I do like to write about topics that interest or confound me, and you can find these papers at this link. My two most widely downloaded papers are updates I do each year on the equity risk premium (in March) and country risk premiums (in July). Much of the material in these papers has made its way into one or more of my books, and thus, if you find the books unaffordable, you can get that material here for free.Blog posts: I will confess that when I write my first blog post on September 17, 2008, I had no idea what a blog was, what I was doing with it, and whether it would last through the following week. In the years since, this blog has become my first go-to, when I have doubts or questions about something, and I am trying to resolve those doubts for myself. In short, my blog has becoming my therapy spot, in times of uncertainty, and I have had no qualms about admitting to these doubts. During 2020, as COVID made us question almost everything we know about markets and the economy, for instance, I posted on where I was in the uncertainty spectrum every week from February 14, 2020 (when the virus became a global problem, not one restricted to China and cruise ships) to November 2020, when the vaccine appeared. You can get all of those posts in one paper, if you click on this link. While my original blog was on Google, in the last two years, I have replicated these posts on Substack (you need to be a subscriber, but it is free) and on LinkedIn. If you are on the latter, you are welcome to follow me, but I have hit my connections limit (I did not even know there was one, until I hit it) and am unable to add connections.YouTube: For the last decade, I have posted my class videos on YouTube, grouping them into playlists for each class. You can start with the link to my YouTube channel here, but if you are interested in taking a class, my suggestion is that you click on the playlists and pick on the one that corresponds to the class. Here, for instance, are my links to my Spring 2025 MBA valuation class and my Spring 2025 Corporate Finance class. Starting about a decade, I have also accompanied every one of my blog posts with a YouTube video, that contains the same material, and you can find those posts in its own (very long) playlist. X (Twitter): Some of you have strong feelings about X, with some of those feelings reflecting your political leanings and others driven by the sometimes toxic posting on the platform. I have been a user of the platform since April 2009, and I have used it as a bulletin board, to alert people to content being posted elsewhere. In fact, outside of these "alert" posts, I almost never post on X, and steer away as far away as I can from debates and discussions on the platform, since a version of Gresham's law seems to kick in, where the worst and least informed posters hijack the debate and take it in directions that you do not want it to go.I cannot think of a single item of content that I have produced in the last decade that is not on one of these platforms, making my professional life an open book, and thus also accessible to any AI entity. The Damodaran bot that I wrote about last year has access to all of this material, and while I signed off on that and one other variant, there are multiple unauthorized versions that have been works-in-progress.The Commonalities My content has taken many forms including posts, videos, data and spreadsheets, and is on multiple platforms, but there are a few common features that they share:

Low tech: I am decidedly low tech, and it shows in my sharing. My website looks like it was designed two decades ago, because it was, and contains none of the bells and whistles that make for a modern website. My blog remains on Google blogger, notwithstanding everything I have been told about how using WordPress would make it more attractive/adaptable, and my posts are neither short nor punchy. Every week, I get people reaching out to me to tell me that my YouTube videos are far too long and verbose, and that I would get more people watching with shorter videos and catchier descriptions, and much as I appreciate their offers to help, I have not taken them up on it., In addition, I shoot almost every one of my videos in my office, sometimes with my dog in the background, and often with ambient noise and mistakes embedded, making them definitely unpolished. On twitter, I have only recently taken to stringing tweets together and I have never used the long text version that some professional twitter users have mastered. In my defense, I could always claim that I am too old to learn new tricks, but the truth is that I did not start any of my sharing as a means to acquiring a larger social media following, and it may very well be true that keeping my presence low-tech operates as a screener, repelling mismatched users.Process over product: In my writing and teaching, I am often taken to task for not getting to the bottom line (Is the stock cheap or expensive? Should I buy or sell?) quickly, and spending so much time on the why and how, as opposed to the what. Much as my verbosity may frustrate you, it reflects what I think my job is as a teacher, which is to be transparent about process, i.e., explain how I reasoned my way to getting an answer than giving you my answer.Pragmatism over Purity: Though I am often criticized for being an “academic”, I am a terrible one, and if there were an academic fraternity, I would be shunned. I view much of an academic research as navel gazing, and almost everything I write and teach is for practitioners. Consequently, I am quick to adapt and modify models to make them fit both reality and the available data, and make assumptions that would make a purist blanch. No stock picks or investment advice: In all my years of writing about and valuing markets and individual stocks, I have tried my best to steer away from making stock picks or offering investment advice. That may sound odd, since so much of what I do relates to valuation, and the essence of valuation is that you act on your estimates of value, but here is how I explain the contradiction. I value stocks (like Meta or Nvidia or Amazon or Mercado Libre) and I act (buy or sell) those stocks, based on my valuations, but it is neither my place nor my role to try to get other people to do the same. That said, I will share my story and valuation spreadsheet with you, and if you want to adapt that story/spreadsheet to make it your own, I am at peace with that choice, even if it is different from mine. The essence of good investing is taking ownership of your investment actions, and it is antithetical to that view of the world for me or anyone else to be telling you what to buy or sell.No commercial entanglements: If you do explore my content on any of the platforms it is available on, you will notice that they are free, both in terms of what you pay and how you access them. In fact, none of them are monetized, and if you do see ads on my YouTube videos, it is Google that is collecting the revenue, not me. One reason for this practice is that I am lazy, and monetizing any of these platforms requires jumping through hoops and catering to advertisers that I neither have the time nor the inclination to do. The other is that I believe (though this may be more hope than truth) that one of the reasons that people read what I write or listen to me is because, much as they may disagree with me, I am perceived as (relatively) unbiased. I fear that formalizing a link with any commercial entity (bank, consultant, investor), whether as advisor, consultant or as director, opens the door to the perception of bias. The one exception to the "no commercial entranglements' clause is for my teaching engagements, with the NYU Certificate program and for the handful of valuation seminars I teach in person in the rest of the world. I am grateful that NYU has allowed me to share my class recordings with the world, and I will not begrudge them whatever they make on my certificate classes, though I do offer the same content for free online, on my webpage. I am also indebted to the people and organizations that manage the logistics of my seminars in the rest of the world, and if I can make their life easier by posting about these seminars, I will do so.

The Imitation Game

Given that my end game in sharing is to give access to people who want to use my material, I have generally taken a lax view of others borrowing my slides, data, spreadsheets or even webcasts, for their own purposes.

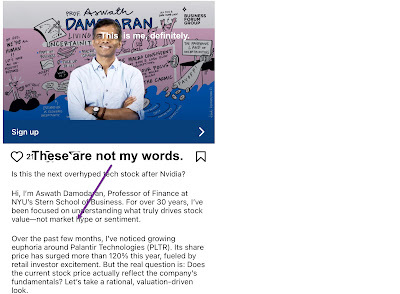

For the most part, I categorize this borrowing as good neighbor sharing, where just as I would lend a neighbor a key cooking ingredient to save them the trouble of a trip to the grocery store, I am at peace with someone using my material to help in their teaching, save time on a valuation or a corporate finance project, prepare for an interview, or even burnish their credentials. An acknowledgement, when this happens, is much appreciated, but I don't take it personally when none is forthcoming. There are less benign copycat versions of the imitation game - selectively using data from my site to back up arguments, misreading or misinterpreting what I have said and reproducing large portions of my writing without acknowledgement. To be honest, if made aware of these transgressions, I have gently nudged the culprits, but I don't have a legal hammer to follow up.The most malignant variations of this game are scams, where the scammers use my content or name to separate people from their money - the education companies that used my YouTube videos and charge for classes, the data sites that copy my data or spreadsheets and sell them to people, and the valuation/investment sites that try to get people to invest money, with my name as a draw. Until now, I have tried, as best as I can, to let people know that they are being victimized, but for the most part, these scams have been so badly designed that they have tended to collapse under the weight of their own contradictions.It is clear to me that AI is now going to change this game, and that I will have to think about new ways to counter its insidious reach. To get a measure of what the current AI scams that are making the rounds get right and wrong, I did take the time to take a closer look at both the Instagram post and the fake video that are making the rounds. What they get right: The Instagram post, which is in shown below, uses language that clearly is drawn from my posts and an image that is clearly mine.

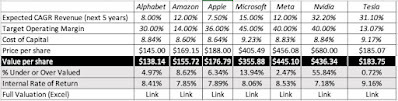

Not only does this post reflect the way I write, but it also picked Nvidia and Palantir as the two firms to highlight, the first a company that I own and have valued on my blog, and the second a company that I have been talking about as one that I am interested in owning, at the right price, giving it a patina of authenticity. The video looks and sounds like me, which should be no surprise since it had thousands of hours of YouTube videos to use as raw data. Using a yiddish word that I picked up in my days in New York, I have the give the scammers credit for chutzpah, on this front,, but I will take a notch off the grade, for the video's slickness, since my videos have much more of a homemade feel to them.

What they struggled with most: The scam does mention that Palantir is "overhyped", a word that I use rarely, and while it talks about the company’s valuation, it is cagey about what that value is and there is little of substance to back up the claim. Palantir is a fascinating company, but to value it, you need a story of a data/software firm, with two channels for value creation, one of which looks at the government as a customer (a lower-margin, stickier and lower growth business) and the other at its commercial market (higher margin, more volatile and higher growth). Each of the stories has shades of grey, with the potential for overlap and conflict, but this is not a company where you can extrapolate the past, slap numbers on revenue growth and profitability, and arrive at a value. This post not only does not provide any tangible backing for its words in terms of value, but it does not even try. If these scammers had truly wanted to pull this off, they could have made their AI bot take my class, construct a plausible Palantir story, put it into my valuation spreadsheet and provide it as a link.

What they get wrong: To get a sense of what this post gets wrong, you should revisit the earlier part of the post where I talk about my sharing philosophy, and with as much distance as I can muster, here are the false notes in this scam. First, this scam pushes people to join an investment club, where I will presumably guide them on what to buy or sell. Given that my view of clubs is very much that of Groucho Marx, which is that I would not be belong to any club which would admit me as a member, the notion of telling people which stocks to buy cuts against every grain of my being. Second, there is a part of this scam where I purportedly promise investors who decide to partake that they will generate returns of 60% or higher, and as someone who has chronicled that not only do most active investors not keep up with the market, and argued that anyone who promises to deliver substantially more than the market in the long term is either a liar or fraud, this is clearly not me.

In sum, there is good news and bad news in this grading assessment. The good news is that this AI scam gets my language and look right, but it is sloppily done in terms of content and capturing who I am as a person. The bad news is that it if this scammer was less lazy and more willing to put in some work, even with the current state of AI, it would have been easy to bring up the grades on content and message. I will wager that the Damodaran Bot that I mentioned earlier on in this post that is being developed at NYU Stern would have created a post that would have been much more difficult for you to detect as fake, making it a Frankenstein monster perhaps in the making. The worse news is that AI technology is evolving, and it will get better on every one of these fronts at imitating others, and you should prepare yourself for a deluge of investment scams.

In sum, there is good news and bad news in this grading assessment. The good news is that this AI scam gets my language and look right, but it is sloppily done in terms of content and capturing who I am as a person. The bad news is that it if this scammer was less lazy and more willing to put in some work, even with the current state of AI, it would have been easy to bring up the grades on content and message. I will wager that the Damodaran Bot that I mentioned earlier on in this post that is being developed at NYU Stern would have created a post that would have been much more difficult for you to detect as fake, making it a Frankenstein monster perhaps in the making. The worse news is that AI technology is evolving, and it will get better on every one of these fronts at imitating others, and you should prepare yourself for a deluge of investment scams.An AI Protective Shield

I did think long about writing this post, wondering whether it would make a difference. After all, if you are a frequent reader of this blog or have read this post all the way down to this point, it is unlikely that you were fooled by the Instagram post or video. It remains an uncomfortable truth that the people most exposed to these scams are the ones who have read little or none of what I have written, and I wish there were a way that I could pass on the following suggestions on how they can protect themselves against the other fakes and scams that will undoubtedly be directed at them.

YouTube Video

LinksWebpage: https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/home.htm Blog: (1) Google: https://aswathdamodaran.blogspot.com (2) Substack: https://aswathdamodaran.substack.com (3) LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/aswathdamodaran/

YouTubehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCLvnJL8htRR1T9cbSccaoVw X: https://x.com/aswathdamodaran?lang=en

July 31, 2025

Country Risk 2025: The Story behind the Numbers!

At the start of July, I updated my estimates of equity risk premiums for countries, in an semiannual ritual that goes back almost three decades. As with some of my other data updates, I have mixed feelings about publishing these numbers. On the one hand, I have no qualms about sharing these estimates, which I use when I value companies, because there is no secret sauce or special insight embedded in them. On the other, I worry about people using these premiums in their valuations, without understanding the choices and assumptions that I had to make to get to them. Country risk, in particular, has many components to it, and while you have to ultimately capture them in numbers, I wanted to use this post to draw attention to the many layers of risk that separate countries. I hope, and especially if you are a user of my risk premiums, that you read this post, and if you do have the time and the stomach, a more detailed and much longer update that I write every year.

Country Risk - Dimensions

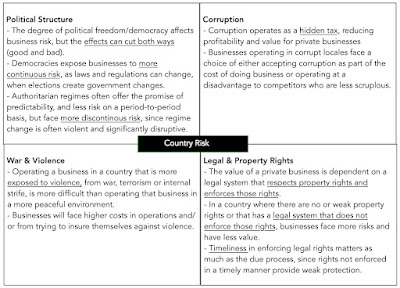

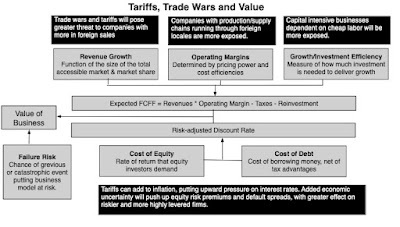

When assessing business risk from operating in a country, you will be affected by uncertainty that arises from almost every source, with concerns about political structure (democracies have very different risk profiles than authoritarian regimes), exposure to violence (affecting both costs and revenues), corruption (which operates an implicit tax) and legal systems (enforcing ownership rights) all playing out in business risk.

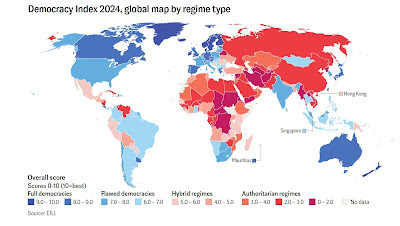

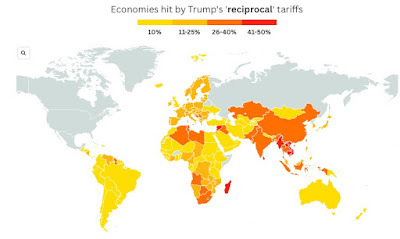

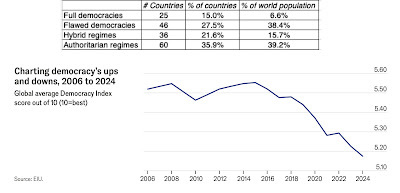

I will start with political structure, where the facile answer is that it less risky to operate a business in a democracy than in an authoritarian regime, but where the often unpalatable truth is that each structure brings its own risks. With democracies, the risk is that newly elected governments can revisit, modify or discard policies that a previous government have adopted, requiring businesses to adapt and change to continuous changes in policy. In contrast, an authoritarian government can provide long term policy continuity, with the catch being that changes in the government, though infrequent, can create wrenching policy shifts that businesses have to learn to live with. Keeping the contrast between the continuous risk of operating in a democracy and the discontinuous risk in an authoritarian structure in mind, take a look at this picture of how the world looked in terms of democracy leading into 2025:

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU)

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU)

It is worth noting that there are judgment calls that the Economist made in measuring democracy that you and I might disagree with, but not only is a large proportion of the world under authoritarian rule, but the trend lines on this dimension also have been towards more authoritarianism in the last decade.

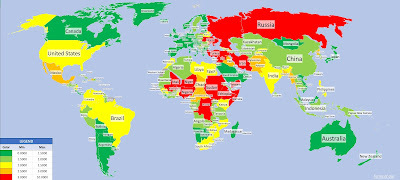

On the second dimension, exposure to violence, the effects on business are manifold. In addition to the threat that violence can affect operations, its presence shows up as higher operating costs (providing security for employees and factories) and as insurance costs (if the risks can be insured). To measure exposure to violence, from both internal and external sources, I draw on measures developed and updated by the Institute of Economics & Peace across countries in 2024:

Institute of Economics & Peace

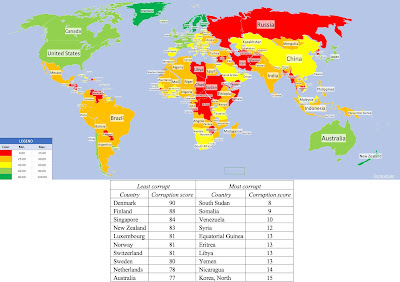

The Russia-Ukraine war has caused risk to flare up in the surrounding states and the Middle East and central Africa continue to be risk cauldrons, but at least according to the Institute's measures, the parts of the world that are least exposed to violence are in Northern Europe, Australia and Canada. Again, there are judgments that are made in computing these scores that will lead you to disagree with specific country measures (according the Peace Institute, the United States and Brazil have higher exposures to violence than Argentina and Chile, and India has more exposure to violence than China), but the bottom line is that there are significant differences in exposure to violence across the world. Corruption is a concern for everyone, but for businesses, it manifests in two ways. First, it puts more honest business operators at a disadvantage in a corrupt environment, since they are less willing to break the rules and go along with corrupt practices than their less scrupulous competitors. Second, even for those businesses that are willing to play the corruption game, it creates costs that I would liken to an implicit tax that reduces profits, cash flows and value. The measure of corruption that I use comes from Transparency International, and leading into July 2025, and the heat map below captures corruption scores (with higher scores indicating less corruption), as well as the ten most and least corrupt countries in the world:

Institute of Economics & Peace

The Russia-Ukraine war has caused risk to flare up in the surrounding states and the Middle East and central Africa continue to be risk cauldrons, but at least according to the Institute's measures, the parts of the world that are least exposed to violence are in Northern Europe, Australia and Canada. Again, there are judgments that are made in computing these scores that will lead you to disagree with specific country measures (according the Peace Institute, the United States and Brazil have higher exposures to violence than Argentina and Chile, and India has more exposure to violence than China), but the bottom line is that there are significant differences in exposure to violence across the world. Corruption is a concern for everyone, but for businesses, it manifests in two ways. First, it puts more honest business operators at a disadvantage in a corrupt environment, since they are less willing to break the rules and go along with corrupt practices than their less scrupulous competitors. Second, even for those businesses that are willing to play the corruption game, it creates costs that I would liken to an implicit tax that reduces profits, cash flows and value. The measure of corruption that I use comes from Transparency International, and leading into July 2025, and the heat map below captures corruption scores (with higher scores indicating less corruption), as well as the ten most and least corrupt countries in the world:

Transparency International

Transparency International

As you can see from the map, there are vast swaths of the world where businesses have to deal with corruption in almost every aspect of business, and while some may attribute this to cultural factors, I have long argued that corruption almost inevitably follows in bureaucratic settings, where you need licenses and approvals for even the most trivial of actions, and the bureaucrats (who make the licensing decisions) are paid a pittance relative to the businesses that they regulate.

As a final component, I look at legal systems, especially when it comes to enforcing contractual agreements and property rights, central to running successful businesses. Here, I used estimates from the IPRI, a non-profit institution that measures the quality of legal systems around the world. In their latest rankings from 2024, here is how countries measured up in 2024:

Property Rights Alliance

Property Rights Alliance

In making these assessments, you have to consider not just the laws in place but also the timeliness with which these laws get enforced, since a legal system where justice is delayed for years or even decades is almost as bad as one that is capricious and biased.

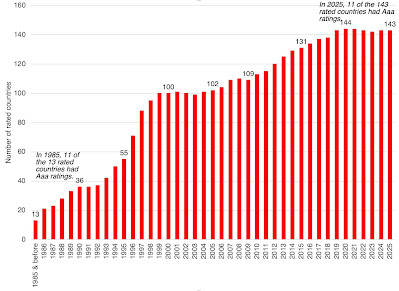

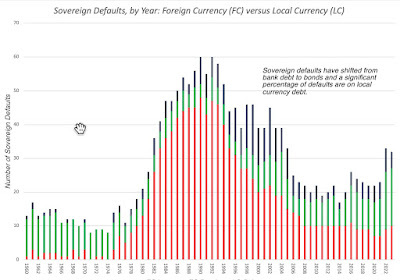

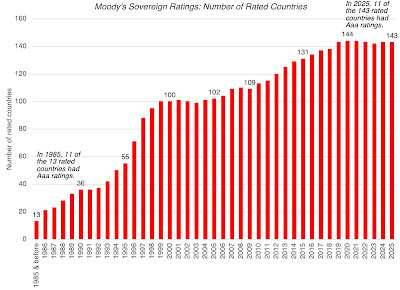

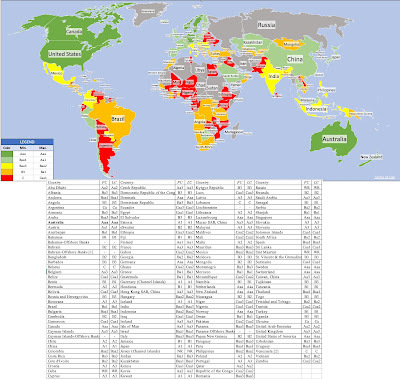

Country Risk - Measures The simplest and most longstanding measure of country risk takes the form of sovereign ratings, with the same agencies that rate companies (S&P, Moody's and Fitch) also rating countries, with the ratings ranging from Aaa (safest) to D (in default). The number of countries with sovereign ratings available on them has surged in the last few decades; Moody’s rated 13 countries in 1985, but that number increased to 143 in 2025, with the figure below listing the number of rated countries over time:

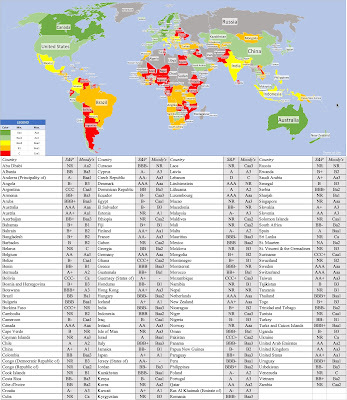

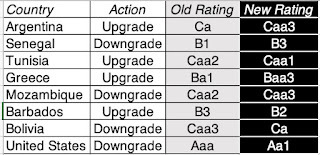

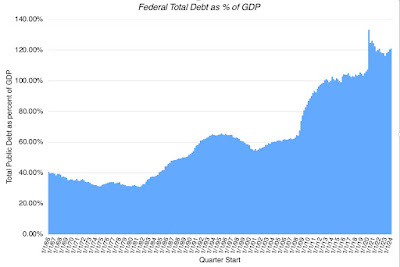

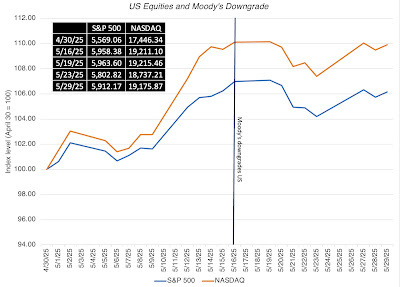

Note that that the number of Aaa rated countries stayed at eleven, even while more countries were rated, and has dropped from fifteen just a decade ago, with the UK and France losing their Aaa ratings during that period. In May 2025, Moody's downgraded the United States, bringing them in line with the other ratings agencies; S&P downgraded the US in 2011 and Fitch in 2023. The heat map below captures sovereign ratings across the world in July 2025:

Note that that the number of Aaa rated countries stayed at eleven, even while more countries were rated, and has dropped from fifteen just a decade ago, with the UK and France losing their Aaa ratings during that period. In May 2025, Moody's downgraded the United States, bringing them in line with the other ratings agencies; S&P downgraded the US in 2011 and Fitch in 2023. The heat map below captures sovereign ratings across the world in July 2025:

Moody's

Moody's

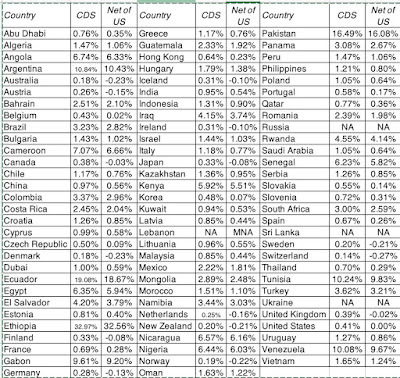

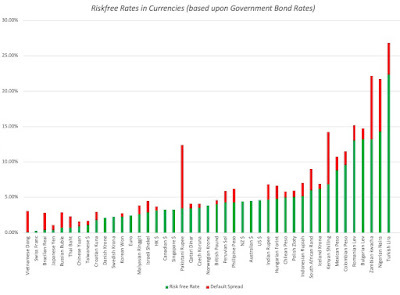

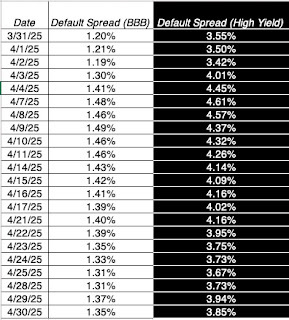

While sovereign ratings are useful risk measures, they do come with caveats. First, their focus on default risk can lead them to be misleading measures of overall country risk, especially in countries that have political risk issues but not much default risk; the Middle East, for instance, has high sovereign ratings. Second, the ratings agencies have blind spots, and some have critiqued these agencies for overrating European countries and underrating Asian, African and Latin American countries. Third, ratings agencies are often slow to react to events on the ground, and ratings changes, when they do occur, often lag changes in default risk. If you are leery about trusting ratings agencies, I understand your distrust, and there is an alternative measure of sovereign default risk, at least for about half of all countries, and that is the sovereign credit default swap (CDS) market, which investors can buy protection against country default. These market-determined numbers will reflect events on the ground almost instantaneously, albeit with more volatility than ratings. At the end of June 2025, there were about 80 countries with sovereign CDS available on them, and the figure below captures the values:

The sovereign CDS spreads are more timely, but as with all market-set numbers, they are subject to mood and momentum swings, and I find using them in conjunction with ratings gives me a better sense of sovereign default risk. If default risk seems like to provide too narrow a focus on countr risk, you can consider using country risk scores, which at least in principle, incorporate other components of country risk. There are many services that estimate country risk scores, including the Economist and the World Bank, but I have long used Political Risk Services (PRS) for my scores.. The PRS country risk scores go from low to high, with the low scores indicative of more country risk, and the table below captures the world (at least according to PRS):

Political Risk Services (PRS)

Political Risk Services (PRS)

There are some puzzling numbers here, with the United States coming in as riskier than Vietnam and Libya, but that is one reason why country risk scores have never acquired traction. They vary across services, often reflecting judgments and choices made by each service, and there is no easy way to convert these scores into usable numbers in business and valuation or compare them across services.

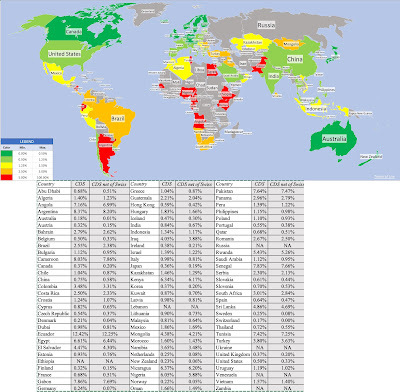

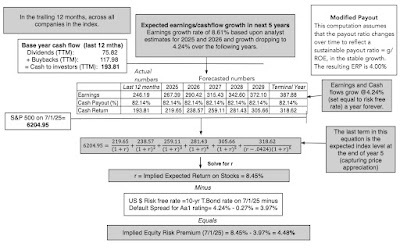

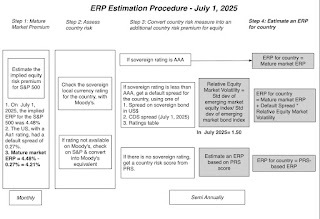

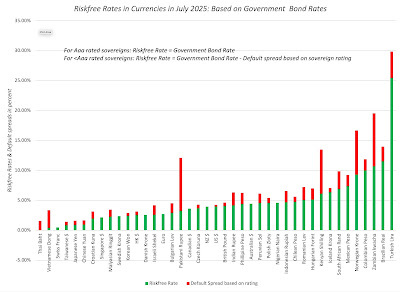

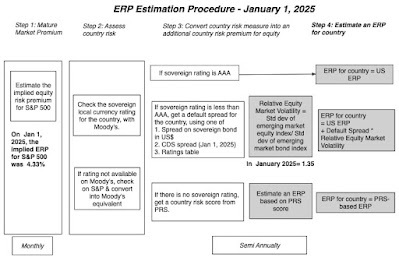

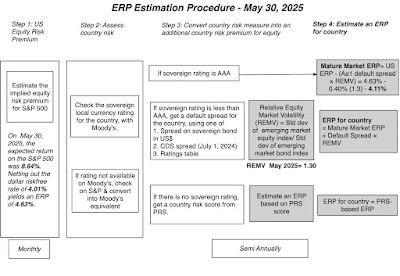

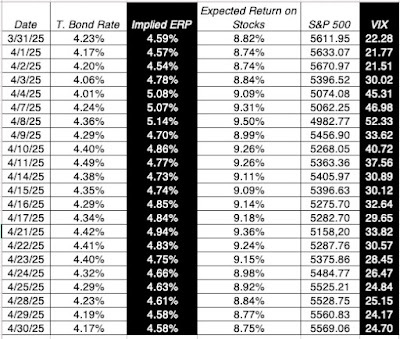

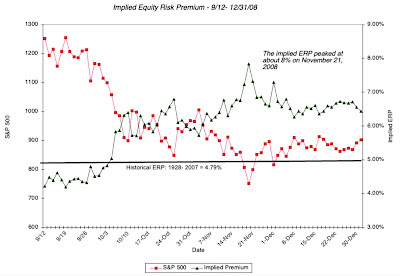

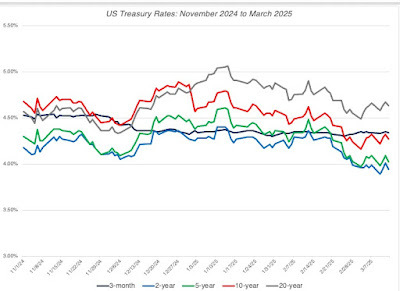

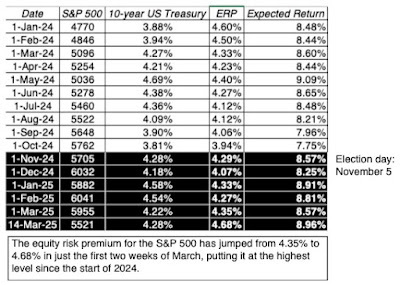

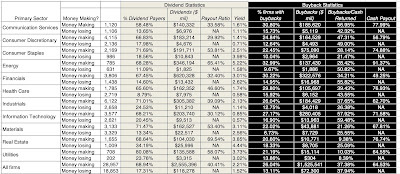

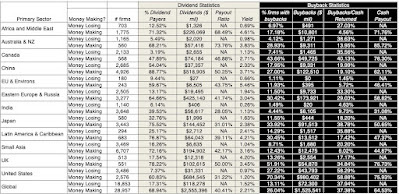

Country Risk - Equity Risk Premiums My interest in country risk stems almost entirely from my work in corporate finance and valuation, since this risk finds its way into the costs of equity and capital that are critical ingredients in both disciplines. To estimate the cost of equity for an investment in a risky country. I will not claim that the approaches I use to compute equity risk premiums for countries are either original or brilliant, but they do have the benefit of consistency, since I have used them every year (with an update at the start of the year and mid-year) since the 1990s. The process starts with my estimate of the implied equity risk premium for the S&P 500, and I make this choice not for parochial reasons but because getting the raw data that you need for the implied equity risk premium is easiest to get for the S&P 500, the most widely tracked index in the world. In particular, the process requires data on dividends and stock buybacks on the stocks in the index, as well as expected growth in these cash flows over time, and involves finding the discount rate (internal rate of return) that makes the present value of cash flows equal to the level of the index. On June 30, 2025, this assessment generated an expected return of 8.45% for the index:

Download ERP spreadsheet

Download ERP spreadsheet

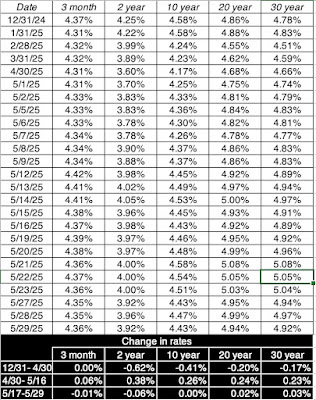

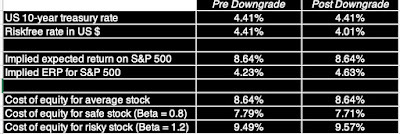

Until May 2025, I just subtracted the US 10-year treasury bond rate from this expected return, to get to an implied equity risk premium for the index, with the rationale that the US T.Bond rate is the riskfree rate in US dollars. The Moody’s downgrade of the US from Aaa to Aa1 has thrown a wrench into the process, since it implies that the T.Bond rate has some default risk associated with it, and thus incorporates a default spread. To remove that risk, I net out the default spread associated with Aa1 rating from the treasury rate to arrive at a riskfree rate in dollars and an equity risk premium based on that:

Riskfree rate in US dollars = T.Bond rate minus Default Spread for Aa1 rating= 4.24% - 0.27% = 3.97%

Implied equity risk premium for US = Expected return on S&P 500 minus US $ riskfree rate= 8.45% - 3.97% = 4.48%Note that this approach to estimating equity risk premiums is model agnostic and reflects what investors are demanding in the market, rather than making a judgment on whether the premium is right or what it should be (which I leave to market timers). To get the equity risk premiums for other countries, I need a base premium for a mature market, i.e., one that has no additional country risk, and here again, the US downgrade has thrown a twist into the process. Rather than use the US equity risk premium as my estimate of the mature market premium, my practice in every update through the start of 2025, I adjusted that premium (4.48%) down to take out the US default spread (0.27%), to arrive at the mature market premium of 4.21%. That then becomes the equity risk premium for the eleven countries that continue to have Aaa ratings, but for all other countries, I estimate default spreads based upon their sovereign ratings. As a final adjustment, I scale these default spreads upwards to incorporate the higher risk of equities, and these become the country risk premiums, which when added to the mature market premium, yields equity risk premiums by country. The process is described below:

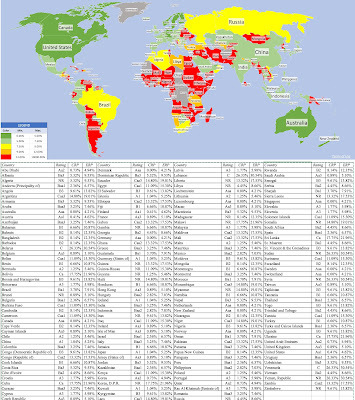

The results from following this process are captured in the picture below, where I create both a heat map based on the equity risk premiums, and report on the ratings, country risk premiums and equity risk premiums, by country:

Download equity risk premium, by country

Download equity risk premium, by country

If you compare the equity risk premium heat map with the heat maps on the other dimensions of country risk (political and legal structures, exposure to violence and corruption), you will notice the congruence. The parts of the world that are most exposed to corruption and violence, and have capricious legal systems, tend to have higher equity risk premiums. The effects of the US ratings downgrade also manifest in the table, with the US now having a higher equity risk premium than its Aaa counterparts in Northern Europe, Australia and Canada.

A User's Guide My estimates of equity risk premiums, by country, are available for download, and I am flattered that there are analysts that have found use for these number. One reason may be that they are free, but I do have concerns sometimes that they are misused, and the fault is mine for not clarifying how they should be used. In this section, I will lay out steps in using these equity risk premiums in corporate finance and valuation practice, and if I have still left areas of grey, please let me know.

Step 1: Start with an understanding of what the equity risk premium measures The starting point for most finance classes is with the recognition that investors are collectively risk averse, and will demand higher expected returns on investments with more risk. The equity risk premium is a measure of the “extra” return that investors need to make, over and above the riskfree rate, to compensate for the higher risk that they are exposed to, on equities collectively. In the context of country risk, it implies that investments in riskier countries will need to earn higher returns to beat benchmarks than in safer countries. Using the numbers from July 2025, this would imply that investors need to earn 7.46% more than the riskfree rate to invest in an average-risk investment in India, and 10.87% more than the riskfree rate to invest in an average risk investment in Turkey. It is also worth recognizing how equity risk premiums play out investing and valuation. Increasing the equity risk premium will raise the rate of return you need to make on an investment, and by doing so, reduce its value. That is why equity risk premiums and stock prices move inversely, with the ERP rising as stock prices drop (all other thins being held constant) and falling as stock prices increase.

Step 2: Pick your currency of analysis (and estimate a riskfree rate) I start my discussions of currency in valuation by positing that currency is a choice, and that not only can you assess any project or value any company in any currency, but also that your assessment of project worth or company value should not be affected by that choice. Defining the equity risk premium as the extra return that investors need to make, over and above the risk free rate, may leave you puzzled about what riskfree rate to use, and while the easy answer is that it should be the riskfree rate in the currency you chose to do the analysis in, it is worth emphasizing that this riskfree rate is not always the government bond rate, and especially so, if the government does not have Aaa rating and faces default risk. In that case, you will need to adjust the government bond rate (just as I did with the US dollar) for the default spread, to prevent double counting risk.

Staying with the example of an Indian investment, the expected return on an average-risk investment in Indian rupees would be computed as follows:Indian government bond rate on July 1, 2025 = 6.32%Default spread for India, based on rating on July 1, 2025 = 2.16%Indian rupee risk free rate on July 1, 2025 = 6.32% - 2.16% = 4.16%ERP for India on July 1, 2025 = 7.46%Expected return on average Indian equity in rupees on July 1, 2025 = 4.16% + 7..46% = 11.62%Note also that if using the Indian government bond rate as the riskfree rate in rupees, you would effectively be double counting Indian country risk, once in the government bond rate and once again in the equity risk premium. I know that the ERP is in dollar terms, and adding it to a rupee riskfree rate may seem inconsistent, but it will work well for riskfree rates that are reasonably close to the US dollar risk free rate. For currencies, like the Brazilian real or Turkish lira, it is more prudent to do your calculations entirely in US dollars, and convert using the differential inflation rate:US dollar riskfree rate on July 1, 2025 = 3.97%ERP for Turkey on July 1, 2025 = 10.87%Expected return on average Turkish equity in US $ on July 1, 2025 = 3.97% + 10.87% = 14.84%Expected inflation rate in US dollars = 2.5%; Expected inflation rate in Turkish lira = 20%Expected return on average Turkish equity Turkish lira on July 1, 2025 = 1.1484 *(1.20/1.025) -1 = 34.45%Note that this process scales up the equity risk premium to a higher number for high-inflation currencies.

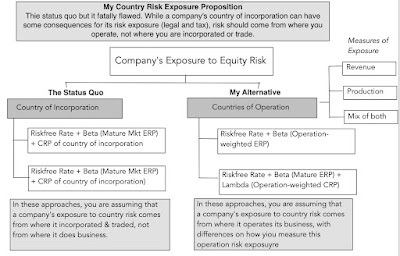

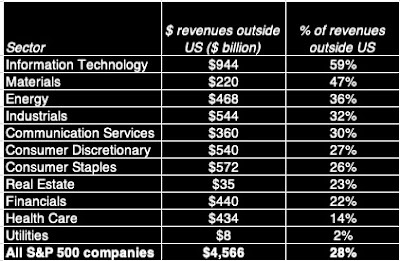

Step 3: Estimate the equity risk premium or premiums that come into play based on operations Many analysts use the equity risk premiums for a country when valuing companies that are incorporated in that country, but I think that is too narrow a perspective. In my view, the exposure to country risk comes from where a company operates, not where it is incorporated, opening the door for bringing in country risk from emerging markets into the cost of equity for multinationals that may be incorporated in mature markets. I use revenue weights, based on geography, for most companies, but I am open to using production weights, for natural resource companies, and even a mix of the two.

In corporate finance, where you need equity risk premiums to estimate costs of equity and capital in project assessment, the location of the project will determine which country’s equity risk premiums come into play. When Amazon decides to invest in a Brazilian online retail project, it is the equity risk premium for Brazil that should be incorporated, with the choice of currency for analysis determining the riskfree rate.

Step 4: Estimate project-specific or company-specific risk measures and costs The riskfree rate and equity-risk premiums are market-wide numbers, driven by macro forces. To complete this process, you need two company-specific numbers:Not all companies or projects are average risk, for equity investors in them, and for companies that are riskier or safer than average, you need a measure of this relative risk. At the risk of provoking those who may be triggered by portfolio theory or the CAPM, the beta is one such measure, but as I have argued elsewhere, I am completely at home with alternative measures of relative equity risk. The cost of equity is calculated as follows:

Cost of equity = Riskfree rate + Beta × Equity Risk Premium

For the cost of debt, you need to estimate the default spread that the company will face. If the company has a bond rating, you can use this rating to estimate the default spread, and if it is not, you can use the company's financials to assess a synthetic rating.Cost of debt =Riskfree Rate + Default spreadThe beta (relative risk measure) measures the risk of the business that the company/project is in, and for a diversified investor, captures only risk that cannot be diversified away. While we are often taught to use regressions against market indices to get these betas, using industry-average or bottom-up betas yields much better estimates for projects and companies.

Harking back to the discussion of riskfree rates, a company in a country with sovereign default risk will often bear a double burden, carrying default spreads for both itself and the country.

The currency choice made in step two will hold, with the riskfree rate in both the cost of equity and debt being the long-term default free rate in that currency (and not always the government bond rate).

Step 5: Ensure that your cash flows are currency consistent The currency choice made in step 2 determines not only the discount rates that you will be using but also the expected cash flows, with expected inflation driving both inputs. Thus, if you analyze a Turkish project in lira, where the expected inflation rate is 20%, you should expect to see costs of equity and capital that exceed 25%, but you should also see growth rates in the cash flows to be inflated the same expected inflation. If you assess the same project in Euros, where the expected inflation is 2%, you should expect to see much lower discount rates, high county risk notwithstanding, but the expected growth in cash flows will also be muted, because of the low inflation. There is nothing in this process that is original or path-breaking, but it does yield a systematic and consistent process for estimating discount rates, the D in DCF. It works for me, because I am a pragmatist, with a valuation mission to complete, but you should feel free to adapt and modify it to meet your concerns.YouTube Video

PaperCountry Risk Determinants: Determinants, Measures and Implications - The 2025 EditionDatasetsEquity Risk Premiums, by country - July 2025Country Risk LinksEIU Democracy IndexGlobal Peace Index (Exposure to Violence)Corruption IndexInternational Property Rights IndexMoody's Sovereign RatingsPolitical Risk Services (PRS) Country Risk ScoresSpreadsheetsImplied Equity Risk Premium for S&P 500 on July 1, 2025

July 18, 2025

To Bitcoin or not to Bitcoin? A Corporate Cash Question!

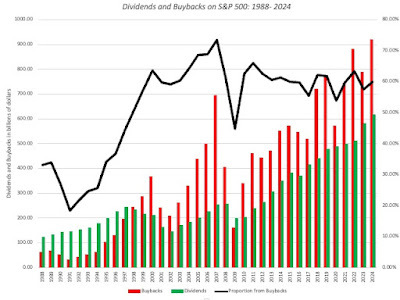

In this post, I will bring together two disparate and very different topics that I have written about in the past. The first is the role that cash holdings play in a business, an extension of the dividend policy question, with an examination of why businesses often should not pay out what they have available to shareholders. In my classes and writing on corporate finance, I look at the motives for businesses retaining cash, as well as how much cash is too much cash. The second is bitcoin, which can be viewed as either a currency or a collectible, and in a series of posts, I argued that bitcoin can only be priced, not valued, making debates about whether to buy or not to buy entirely a function of perception. In fact, I have steered away from saying much about bitcoin in recent years, though I did mention it in my post on alternative investments as a collectible (like gold) that can be added to the choice mix. While there may be little that seemingly connects the two topics (cash and bitcoin), I was drawn to write this post because of a debate that seems to be heating up on whether companies should put some or a large portion of their cash balances into bitcoin, with the success of MicroStrategy, a high-profile beneficiary of this action, driving some of this push. I believe that it is a terrible idea for most companies, and before Bitcoin believers get riled up, my reasoning has absolutely nothing to do with what I think of bitcoin as an investment and more to do with how little I trust corporate managers to time trades right. That said, I do see a small subset of companies, where the holding bitcoin strategy makes sense, as long as there are guardrails on disclosure and governance.

Cash in a Going Concern

In a world where businesses can raise capital (equity or debt) at fair prices and in a timely manner, there is little need to hold cash, but that is not the world we live in. For a variety of reasons, some internal and some external, companies are often unable or unwilling to raise capital from markets, and with that constraint in place, it is logical to hold cash to meet unforeseen needs. In this section, I will start by laying out the role that cash holdings play in any business, and examine how much cash is held by companies, broken down by groupings (regional, size, industry).

A Financial Balance Sheet

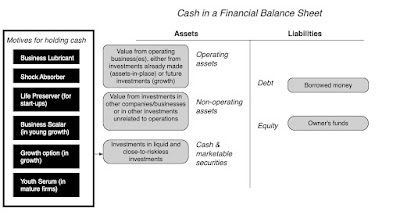

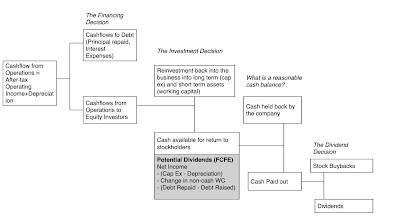

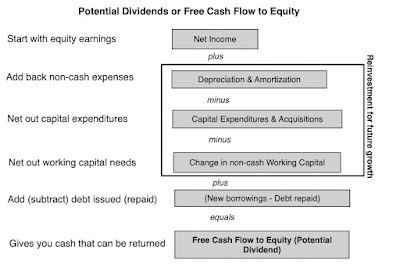

To understand the place of cash in a business, I will start with a financial balance sheet, a structure for breaking down a business, public or private:

On the asset side of the balance sheet, you start with the operating business or businesses that a company is in, with a bifurcation of value into value from investments already made (assets-in-place) and value from investments that the company expects to make in the future (growth assets). The second asset grouping, non-operating assets, includes a range of investments that a company may make, sometimes to augment its core businesses (strategic investments), and sometimes as side investments, and thus include minority holdings in other companies (cross holdings) and even investments in financial assets. Sometimes, as is the case with family group companies, these cross holdings may be a reflection of the company's history as part of the group, with investments in other group companies for either capital or corporate control reasons. The third grouping is for cash and marketable securities, and this is meant specifically for investments that share two common characteristics - they are riskless or close to riskless insofar as holding their value over time and they are liquid in the sense that they can be converted to cash quickly and with no penalty. For most companies, this has meant investing cash in short-term bonds or bills, issued by either governments (assuming that they have little default risk) or by large, safe companies (in the form of commercial paper issued by highly rated firms).

Note that there are two sources of capital for any business, debt or equity, and in assessing how levered a firm is, investors look at the proportion of the capital that comes from each:

Debt to Equity = Debt/ EquityDebt to Capital = Debt/ (Debt + Equity)In fact, there are many analysts and investors who estimate these debt ratios, using net debt, where they net the cash holdings of a company against the debt, with the rationale, merited or not, that cash can be used to pay down debt.

Net Debt to Equity = (Debt-Cash)/ EquityDebt to Capital = (Debt-Cash)/ (Debt + Equity)All of these ratios can be computed using accounting book value numbers for debt and equity or with market value numbers for both.The Motives for holding Cash

In my introductory finance classes, there was little discussion of cash holdings in companies, outside of the sessions on working capital. In those sessions, cash was introduced as a lubricant for businesses, necessary for day-to-day operations. Thus, a retail store that had scores of cash customers, it was argued, needed to hold more cash, often in the form of currency, to meet its transactional needs, than a company with corporate suppliers and business customers, with predictable patterns in operations. In fact, there were rules of thumb that were developed on how much cash a company needed to have for its operations. As the world shifts away from cash to digital and online payments, this need for cash has decreased, but clearly not disappeared. The one carve out is the financial services sector, where the nature of the business (banking, trading, brokerage) requires companies in the sector to hold cash and marketable securities as part of their operating businesses.

If the only reason for holding cash was to cover operating needs, there would be no way to justify the tens of billions of dollars that many companies hold; Apple alone has often had cash balances that exceeded $200 billion, and the other tech giants are not far behind. For some companies, at least, the rationale for holding far more cash than justified by their operating needs is that it can operate as a shock absorber, something that they can fall back on during periods of crisis or to cover unexpected expenses. That is the reason that cyclical and commodity firms have often offered for holding large cash balances (as a percent of their overall firm value), since a recession or a commodity price downturn can quickly turn profits to losses.

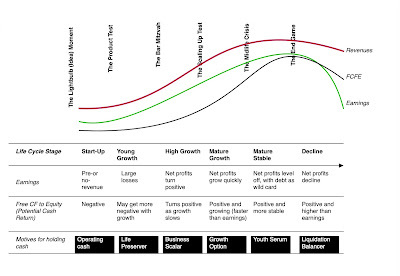

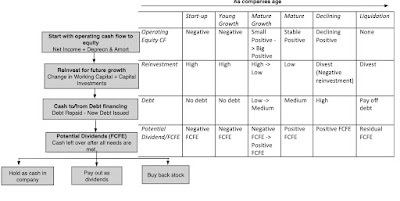

Using the corporate life cycle structure can also provide insight into how the motives for holding cash can change as a company ages.

For start-ups, that are either pre-revenue or have very low revenues, cash is needed to keep the business operating, since employees have to be paid and expenses covered. Young firms that are money-losing and with large negative cash flows, hold cash to cover future cash flow needs and to fend off the risk of failure. In effect, these firms are using cash as life preservers, where they can make it through periods where external capital (venture capital, in particular) dries up, without having to sell their growth potential at bargain basement prices. As firms start to make money, and enter high growth, cash has use as a business scalar, for firms that want to scale up quickly. In mature growth, cash acquires optionality, useful in allowing the business to find new markets for its products or product extensions. Mature firms sometimes hold cash as youth serum, hoping that it can be used to make once-in-a-lifetime investments that may take them back to their growth days, and for declining firms, cash becomes a liquidation manager, allowing for the orderly repayment of debt and sale of assets.

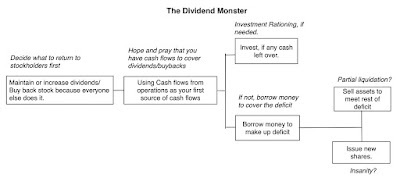

There is a final rationale for holding cash that is rooted in corporate governance and the control and power that comes from holding cash. I have long argued that absent pressure from shareholders, managers at most publicly traded firms would choose to return very little of the cash that they generate, since that cash balance not only makes them more sought after (by bankers and consultants who are endlessly inventive about uses that the cash can be put to) but also gives them the power to build corporate empires and create personal legacies.

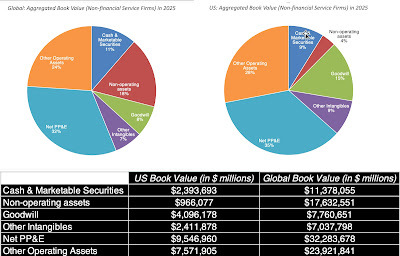

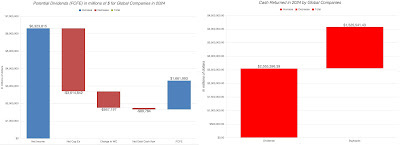

Corporate Cash Holdings

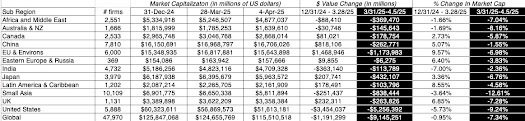

Given the multitude of reasons for holding cash, it should come as no surprise that publicly traded companies around the world have significant cash balances. Leading into July 2025, for instance, global non-financial-service firms held almost $11.4 trillion in cash and marketable securities; financial service firms held even more in cash and marketable securities, but those holdings, as we noted earlier, can represent their business needs. Using our earlier breakdown of the asset side of the balance sheet into cash, non-operating and operating assets, this is what non-financial service firms in the aggregate looked like in book value terms (global and just US firms):

Note that cash is about 11% of the book value of total assets, in the aggregate, for global firms, and about 9% of the book value of total assets, for US firms. Global firms do hold a higher percentage of their value in non-operating assets, but US firms are more active on the acquisition front, explaining why goodwill (which is triggered almost entirely by acquisitions) is greater at US firms.

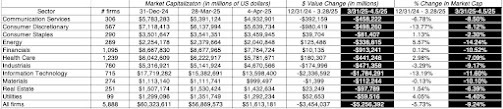

The typical publicly traded firm holds a large cash balance, but there are significant differences in cash holdings, by sector. In the table below, I look at cash as a percent of total assets, a book value measure, as well as cash as a percent of firm value, computed by aggregating market values:

As you can see, technology firms, which presumably face more uncertainty about their future hold far more cash as a percent of book value, but the value that the market attaches to their growth brings down cash as a percent of firm value. Utilities, regulated and often stable businesses, tend to hold the least cash, both in book and market terms.

Breaking down the sample by region, I look at cash holdings, as a percent of total assets and firms, across the globe:

The differences across the globe can be explained by a mix of market access, with countries in parts of the world where it can be difficult to access capital (Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa) holding more cash. In addition, and corporate governance, with cash holdings being greater in parts of the world (China, Russia) where shareholders have less power over managers.

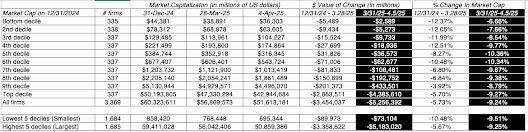

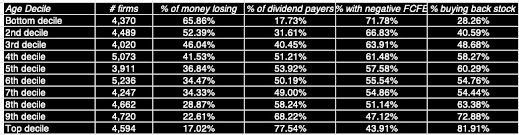

Given the earlier discussion of how the motives for holding cash can vary across the life cycle, I broke the sample down by age decile, with age measured from the year of founding, and looked at cash holdings, by decile:

The results are mixed, with cash holdings as a percent of total assets being higher for the younger half of the sample (the top five deciles) than for the older half, but the is no discernible pattern, when cash is measured as a percent of firm value (market). Put simple, companies across the life cycle hold cash, though with different motives, with the youngest firms holding on to cash as lifesavers (and for survival) and the older firms keeping cash in the hopes that they can use it to rediscover their youth.

The Magic of Bitcoin

I have been teaching and working with investments now for four decades, and there has been no investment that has received as much attention from both investors and the financial press, relative to its actual value, as has bitcoin. Some of the draw has come from its connections to the digital age, but much of it has come from its rapid rise in price that has made many rich, with intermittent collapses that have made just as many poor. I am a novice when it comes to crypto, and while I have been open about the fact that it is not my investment preference, I understand its draw, especially for younger investors.

The Short, Eventful History of Bitcoin

The origin story for Bitcoin matters since it helps us understand both its appeal and its structure. It was born in November 2008, two months into one of the worst financial crises of the last century, with banks and governments viewed as largely responsible for the mess. Not surprisingly, Bitcoin was built on the presumption that you cannot trust these institutions, and its biggest innovation was the blockchain, designed as a way of crowd-checking transactions and preserving transaction integrity. I have long described Bitcoin as a currency designed by the paranoid for the paranoid, and I have never meant that as a critique, since in the untrustworthy world that we live in, paranoia is a justifiable posture.

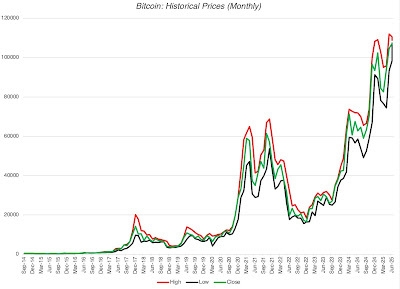

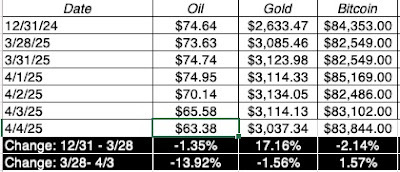

From its humble beginnings, where only a few (mostly tech geeks) were aware of its existence, Bitcoin has accumulated evangelists, who argue that it is the currency of the future, and speculators who have used its wild price swings to make and lose tens of millions of dollars. In the chart below, I look at the price of bitcoin over the last decade, as its price has increased from less than $400 in September 2014 to more than $110,000 in June 2025:

Along the way, Bitcoin has also found some acceptance as a currency, first for illegal activities (drugs on the Silk Road) and then as the currency for countries with failed fiat currencies (like El Salvador), but even Bitcoin advocates will agree that its use in transactions (as the medium of exchange) has not kept pace with its growth as a speculative trade.

Along the way, Bitcoin has also found some acceptance as a currency, first for illegal activities (drugs on the Silk Road) and then as the currency for countries with failed fiat currencies (like El Salvador), but even Bitcoin advocates will agree that its use in transactions (as the medium of exchange) has not kept pace with its growth as a speculative trade.

Pricing Bitcoin

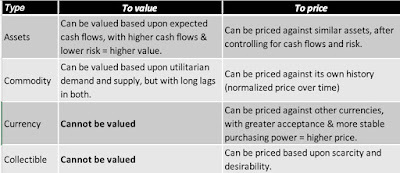

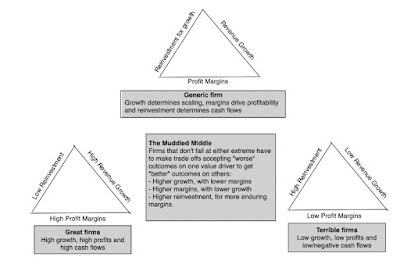

In a post in 2017, I divided investments into four groups - assets that generate cash flows (stocks, bonds, private businesses), commodities that can be used to produce other goods (oil, iron ore etc), currencies that act as mediums of exchange and stores of value and collectibles that are priced based on demand and supply:

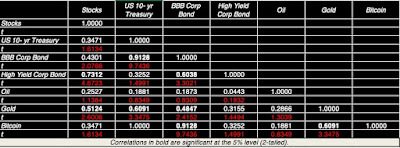

You may disagree with my categorization, and there are shades of gray, where an investment can be in more than one grouping. Gold, for instance, is both a collectible of long standing and a commodity that has specific uses, but the former dominates the latter, when it comes to pricing. In the same vein, crypto has a diverse array of players, with a few meeting the asset test and some (like ethereum) having commodity features. The contrast between the different investment classes also allows for a contrast between investing, where you buy (sell) an investment if it is under (over) valued, and trading, where you buy (sell) an investment if you expect its price to go up (down). The former is a choice, though not a requirement, with an asset (stocks, bonds or private businesses), though there may be others who still trade that asset. With currencies and collectibles, you can only trade, making judgments on price direction, which, in turn, requires assessments of mood and momentum, rather than fundamentals. With bitcoin, this classification allows us to cut through the many distractions that pop up during discussions of its pricing level, since it can be framed either as a currency or a collectible, and thus only priced, not valued. Seventeen years into its existence, Bitcoin has struggled on the currency front, and while there are pockets where it has gained acceptance, its design makes it inefficient and its volatility has impeded its adoption as a medium of exchange. As a collectible, Bitcoin starts with the advantage of scarcity, restricted as it is to 21 million units, but it has not quite measured up, at least so far, when it comes to holding its value (or increasing it) when financial assets are in meltdown mode. In every crisis since 2008, Bitcoin has behaved more like risky stock, falling far more than the average stock, when stocks are down, and rising more, when they recover. I noted this in my posts looking at the performance of investments in both the first quarter of 2020, when COVID laid waste to markets, and in 2022, when inflation ravaged stock and bond markets. That said, it is still early in its life, and it is entirely possible that it may change its behavior as it matures and draws in a wider investor base. The bottom line is that discussions of whether Bitcoin is cheap or expensive are often pointless and sometimes frustrating, since it depends almost entirely on your perspective on how the demand for Bitcoin will shift over time. If you believe that its appeal will fade, and that it will be displaced by other collectibles, perhaps even in the crypto space, you will be in the short selling camp. If you are convinced that its appeal will not just endure but also reach fresh segments of the market, you are on solid ground in assuming that its price will continue to rise. It behooves both groups to admit that neither has a monopoly on the truth, and this is a disagreement about trading and not an argument about fundamentals.

The MicroStrategy Story

It is undeniable that one company, MicroStrategy, has done more to advance the corporate holding of Bitcoin than any other, and that has come from four factors;

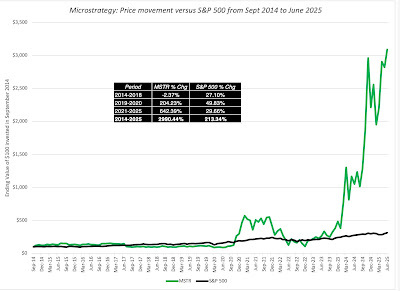

A stock market winner: The company's stock price has surged over the last decade, making it one of the best performing stocks on the US exchanges: It is worth noting that almost all of the outperformance has occurred in this decade, with the winnings concentrated into the last two years. With the rise (increasingly) tied to Bitcoin: Almost all of MicroStrategy’s outperformance has come from its holdings of bitcoin, and not come from improvements in business operations. That comes through in the graph below, where I look at the prices of MicroStrategy and Bitcoin since 2014:

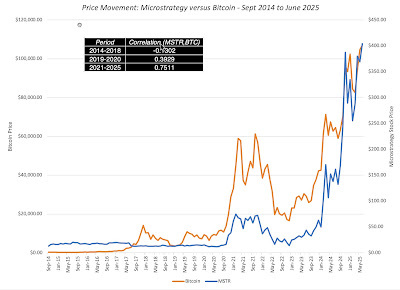

It is worth noting that almost all of the outperformance has occurred in this decade, with the winnings concentrated into the last two years. With the rise (increasingly) tied to Bitcoin: Almost all of MicroStrategy’s outperformance has come from its holdings of bitcoin, and not come from improvements in business operations. That comes through in the graph below, where I look at the prices of MicroStrategy and Bitcoin since 2014:

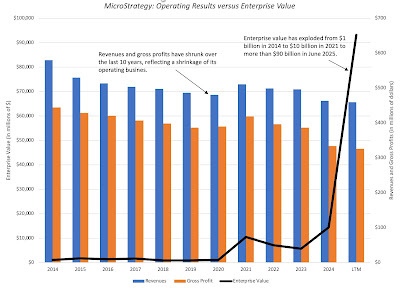

Note that MicroStrategy’s stock price has gone from being slightly negatively correlated with Bitcoin’s price between 2014-2018 to tracking Bitcoin in more recent years.And disconnected from operations: In 2014, MicroStrategy was viewed and priced as a software/services tech company, albeit a small one with promise. In the last decade, its operating numbers have stagnated, with both revenues and gross profits declining, but during the same period, its enterprise value has soared from $1 billion in 2014 to more than more than $100 billion in July 2025:

It is clear now that anyone investing in MicroStrategy at its current market cap (>$100 billion) is making a bitcoin play.With a high-profile "bitcoin evangelist" as CEO: MicroStrategy’s CEO, Michael Saylor, has been a vocal and highly visible promoter of bitcoin, and has converted many of his shareholders into fellow-evangelists and convinced at least some of them that he is prescient in detecting price movements. In recent years, he has been public in his plans to issue increasing amounts of stock and using the proceeds to buy more bitcoin.In sum, MicroStrategy is now less a software company and more a Bitcoin SPAC or closed-end fund, where investors are trusting Saylor to make the right trading judgments on when to buy (and sell) bitcoin, and hoping to benefit from the profits.

The “Put your cash in bitcoin” movement

For investors in other publicly traded companies that have struggled delivering value in their operating businesses, MicroStrategy’s success with its bitcoin holdings seems to indicate a lost opportunity, and one that can be remedied by jumping on the bandwagon now. In recent months, even high profile companies, like Microsoft, have seen shareholder proposals pushing them to abandon their conventional practice of holding cash in liquid and close-to-riskless investments and buying Bitcoin instead. Microsoft’s shareholders soundly rejected the proposal, and I will start by arguing that they were right, and that for most companies, investing cash in bitcoin does not make sense, but in the second part, I will carve out the exceptions to this rule.

The General Principle: No to Bitcoin

As a general rule, I think it is not only a bad idea for most companies to invest their cash in bitcoin, but I would go further and also argue that they should banned from doing so. Let me hasten to add that I would make this assertion even if I was bullish on Bitcoin, and my argument would apply just as strongly to companies considering moving their cash into gold, Picassos or sports franchises, for five reasons:

The Carveouts

I do believe that there are cases when you, as a shareholder, may be at peace with the company not only investing cash in bitcoin, but doing so actively and aggressively. Here are four of my carveouts to the general rule on bitcoin:

Even with these exceptions, though, I think that you need guardrails before signing off on opening the door to letting companies hold bitcoin.

Shareholder buy-in: If you are a publicly traded company considering investing some or much of the company's cash in bitcoin, it behooves you to get shareholder approval for that move, since it is shareholder cash that is being deployed. Transparency about Bitcoin transactions/holdings: Once a company invests in bitcoin, it is imperative that there be full and clear disclosure not only on those holdings but also on trading (buying and selling) that occurs. After all, if it is a company's claim that it can time its bitcoin trades better than the average investor, it should reveal the prices at which it bought and sold its bitcoin. Clear mark-to-market rules: If a company invests its cash in bitcoin, I will assume that the value of that bitcoin will be volatile, and accounting rules have to clearly specify how that bitcoin gets marked to market, and where the profits and losses from that marking to market will show up in the financial statements. As bitcoin prices rise to all time highs, there is the danger that regulators and rule-writers will be lax in their rule-writing, opening the door to corporate scandals in the future.Cui Bono?

Bitcoin advocates have been aggressively pushing both institutional investors and companies to include Bitcoin in their investment choices, and it is true that at least first sight, they will benefit from that inclusion. Expanding the demand for bitcoin, an investment with a fixed supply, will drive the price upwards, and existing bitcoin holders will benefit. In fact, much of the rise of bitcoin since the Trump election in November 2024 can be attributed to the perception that this administration will ease the way for companies and investors to join in the crypto bonanza.

For bitcoin holders, increasing institutional and corporate buy-in to bitcoin may seem like an unmixed blessing, but there will be costs that, in the long run, may lead at least some of them to regret this push:

YouTube Video

June 17, 2025

The (Uncertain) Payoff from Alternative Investments: Many a slip between the cup and the lip?

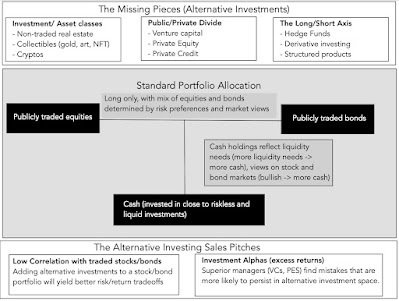

The Alternative Investment Universe The use of the word "alternative" in the alternative investing pitch is premised on the belief that much of investing advice is aimed at long-only investors allocating their portfolios between traded stocks, bonds and cash (close to riskless and liquid investments). In that standard investment model, investors choose a stock-bond mix, for investing, and use cash as a buffer to bring in not only liquidity needs and risk preferences, but also views on stock and bond markets (being over or under priced):

The mix of stocks and bonds is determined both by risk preferences, with more risk taking associated with a higher allocation to stocks, and market timing playing into more invested in stocks (if stocks are viewed as under priced) or more into bonds (if stocks are over priced and bond are viewed as neutral investments). This framework accommodates a range of choices, from the purely mechanical (like the much touted 60% stocks/40% bonds mix) to more flexible, where allocations can vary across time and be a function of market conditions. This general framework allows for variants, including different view on markets (from those who believe that markets are efficient to stock pickers and market timers) as well as investors with very different time horizons and risk levels. However, there are clearly large segments of investing that are left out of this mix from private businesses (since they are not listed and traded) to short selling (where you can have negative portfolio weights not just on individual investments but on entire markets) to asset classes that are not traded. In fact, the best way to structure the alternative investing universe if by looking at alternatives through the lens of these missing pieces.

1. Long-Short In principle, there is little difference between being long on an investment and holding a short position, with the only real difference being in the sequencing of cash flows, with the former requiring a negative cash flow at the time of the action (buying the stock or an asset) and a positive cash flow in a subsequent period (when it is sold), and the latter reversing the process, with the positive cash flow occurring initially (when you sell a stock or an asset that you do not own yet) and the negative cash flow later. That said, they represent actions that you would take with diametrically opposite views of the same stock (asset), with being long (going short) making sense on assets where you expect prices to go up (down). In practice, though, regulators and a subset of investors seem to view short selling more negatively, often not just attaching loaded terms like "speculation" to describe it, but also adding restrictions of how and when it can be done. Many institutional investors, including most mutual, pension and endowment funds, are restricted from taking short positions on investments, with exceptions sometimes carved out for hedging. For close to a century, at least in the United States, hedge funds have been given the freedom to short assets, and while they do not always use that power to benefit, it is undeniable that having that power allows them to create return distributions (in terms of expected returns, volatility and other distributional parameters) that are different from those faced by long-only investors. Within the hedge fund universe, there are diverse strategies that not only augment long-only strategies (value, growth) but also invest across multiple markets (stocks, bonds and convertibles) and geographies. The opening up of derivatives markets has allowed some investors to create investment positions and or structured products that use options, futures, swaps and forwards to create cash flow and return profiles that diverge from stock and bond market returns.

2. Public-Private While much of our attention is spent on publicly traded stocks and bonds, there is a large segment of the economy that is composed of private businesses that are not listed or traded. In fact, there are economies, especially in emerging markets, where the bulk of economic activity occurs in the private business space, with only a small subset of businesses meeting the public listing/trading threshold. Many of these private businesses are owned and funded by their owners, but a significant proportion do need outside equity capital, and historically, there have been two providers:

For young private businesses, and especially those that aspire to become bigger and eventually go public, it is venture capital that fills the void, covering the spectrum from angel financing for idea businesses to growth capital for firms further along in their evolution. From its beginnings in the 1950s, venture capital has grown bigger and carries more heft, especially as technology companies have come to dominate the market in the twenty first century.For more established private businesses, some of which need capital to grow and some of which have owners who want to cash out, the capital has come from private equity investors. Again, while private equity has been part of markets for a century or more, it has become more formalized and spread its reach in the last four decades, with the capacity to raise tens of billions of dollars to back up deal making.On the debt front, the public debt and bank debt market is supplemented by private credit, where investors pool funds to lend to private businesses, with negotiated rates and terms. again a process that has been around a while, but one that has also become formalized and a much larger source of funds. Advocates for private credit investing argue that it can be value-adding partly because of the borrower composition (often cut off from other sources of credit, either because of their size or default history) and partly because private credit providers can be more discerning of true default risk. Even as venture capital, private equity and private credit have expanded as capital sources, they remained out of reach for both institutional and individual investors until a couple of decades ago, but are now integral parts of the alternative investing universe.

3. Asset classes Public equity and debt, at least in the United States, cover a wide spectrum of the economy, and by extension, multiple asset classes and businesses, but there are big investment classes that are either underrepresented in public markets or missing.

Real estate: For much of the twentieth century, real estate remained outside the purview of public markets, with a segmented investor base and illiquid investments, requiring localized knowledge. That started to change with the creation of real estate investment trusts, which securitized a small segment of the market, creating liquidity and standardized units for public market investors. The securitization process gained stream in the 1980s with the advent of mortgage-backed securities. Thus, real estate now has a presence in public markets, but that presence is far smaller than it should be, given the value of real estate in the economy.Collectibles: The collectible asset class spans an array of investment, most of which generate little or no cash flows, but derive their pricing from scarcity and enduring demand. The first and perhaps the longest standing collectible is gold, a draw for investors during inflationary period or when they lose faith in fiat currencies and governments. The second is art, ranging from paintings from the masters to digital art (non-fungible tokens or NFTs), that presumably offers owners not just financial returns but emotional dividends. At the risk of raising the ire of crypto-enthusiasts, I would argue that much of the crypto space (and especially bitcoin) also fall into this grouping, with a combination of scarcity and trading demand determining pricing. Institutional and individual investors have dabbled with adding these asset classes to their portfolios, but the lack of liquidity and standardization and the need for expert assessments (especially on fine art) have limited those attempts.

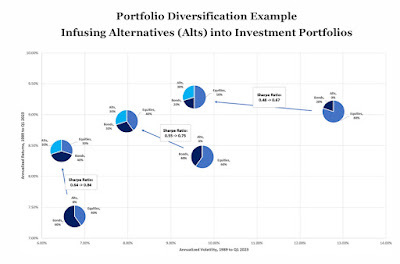

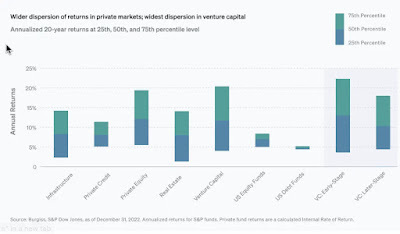

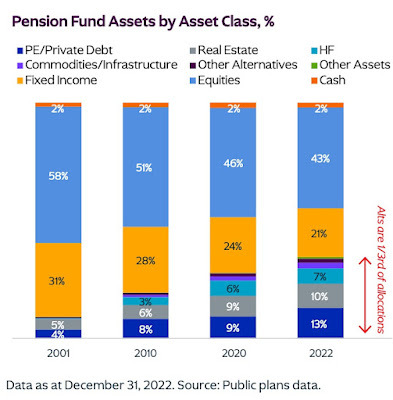

The Sales Pitch for Alternatives The strongest pitch for adding alternative investments to a portfolio dominated by publicly traded stocks and bonds comes from a basic building block for portfolio theory, which is that adding investments that have low correlation to the existing holdings in a portfolio can create better risk/return tradeoffs for investors. That pitch has been supplemented in the last two decades with arguments that alternative investments also offer a greater chance of finding market mistakes and inefficiencies, partly because they are more likely to persist in these markets, and partly because of superior management skills on the part of alternative investment managers, particularly hedge funds and private equity.