Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 3

December 11, 2024

For the fun of it: An Open House for my Spring 2025 Classes

My Motives for Teaching

I was in the second year of my MBA program at UCLA, when I had my moment on grace. I had taken a job as a teaching assistant, almost entirely because I needed the money to pay my tuition and living expenses, and in a subject (accounting) that did not excite me in the least. A few minutes after I walked in to teach my first class, I realized that I had found what I wanted to do for the rest of my life, and I have been a teacher ever since. Since that was 1983, this will be my forty first year teaching, and I have never once regretted my choice. I know that teaching is not a profession held in high esteem anymore, for good and bad reasons, and I will not try to defend it here. It is possible that some of the critics are right, and I teach because I cannot do, but I like to think that there is more to my career choice than ineptitude. My motivations for teaching are manifold, and let me list some of them:I like the stage: I believe that every teacher, to some extent, has a little bit of a repressed actor in him or her, and I do enjoy being in front of an audience, with the added benefit that I get to review the audience, with the grades that I given them, rather than the other way around.I like to make a difference: I do not expect my students to agree with all or even much of what I have to say, but I would like to think that I sometimes change the way they think about finance, and perhaps even affect their choice of professions. I am lucky enough to hear from students who were in my classes decades ago, and to find out that my teaching made a difference in their lives. I like not having a boss: I would be a terrible employee, since I am headstrong, opinionated and awfully lazy, especially when I must do things I don’t like to do. As a teacher, I am my own boss and find my foibles completely understandable and forgivable.I know that teaching may not be your cup of tea, but I do hope that you enjoy whatever you do, as much as I do teaching, and I would like to think that some of that joy comes through.

My Teaching Process

I do a session on how to teach for business school faculty, and I emphasize that there is no one template for a good teacher. I am an old-fashioned lecturer, a control freak when it comes to what happens in my classroom. In forty years of teaching, I have never once had a guest lecturer in my classroom or turned my class over to a free-for-all discussion.Class narrative: This may be a quirk of mine, but I stay away from teaching classes that are collections of topics. In my view, having a unifying narrative not only makes a class more fun to teach, but also more memorable. As you look at my class list in the next section, you will note that each of the classes is built around a story line, with the sessions building up to what is hopefully a climax.Bulking up the reasoning muscle: When asked a question in class, even if I know the answer, I try to not only reason my way to an answer, but to also be open about doubts that I may have about that answer. In keeping with the old saying that it is better to teach someone to fish, than to give them fish, I believe it is my job to equip my students with the capacity to come up with answers to questions that they may face in the future. In my post on the threat that AI poses to us, I argued that one advantage we have over AI is the capacity to reason, but that the ease of looking up answers online, i.e., the Google search curse, is eating away at that capacity.Make it real: I know that, and especially so in business schools, students feel that what they are learning will not work in the real world. I like to think that my classes are firmly grounded in reality, with my examples being real companies in real time. I am aware of the risks that when you work with companies in real time, your mistakes will also play out in real time, but I am okay with being wrong. Straight answers: When I was a student, I remember being frustrated by teachers, who so thoroughly hedged themselves, with the one hand and the other hand playing out, that they left me unclear about what they were saying. I would like to think that I do not hold back, and that I stay true to the motto that I would rather be transparently wrong than opaquely right. It has sometimes got me some blowback, when I expressed my views about value investing being rigid, ritualistic and righteous and the absolute emptiness of virtue concepts like ESG and sustainability, but so be it.I am aware of things that I need to work on. My ego sometimes still gets in the way of admitting when I am wrong, I often do not let students finish their questions before answering them, I am sometimes more abrupt (and less kind) than I should be, especially when I am trying to get through material and my jokes can be off color and corny (as my kids point out to me). I do keep working on my teaching, though, and if you are a teacher, no matter what level you teach at, I think of you as a kindred spirit.

My Class Content

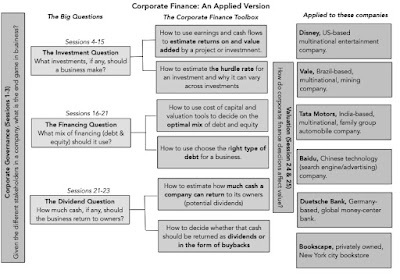

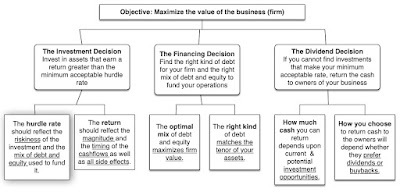

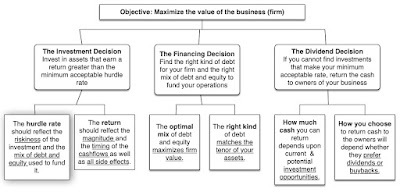

In my first two years of teaching, from 1984 to 1986, I was a visiting professor at the University of California at Berkeley, and like many visiting faculty around the world, I was asked to plug in holes in the teaching schedule. I taught six different classes ranging from a corporate finance class to undergraduates to a central banking for executive MBAs, and while I spent almost all of my time struggling to stay ahead of my students, with the material, it set me on a pathway to being a generalist. Once I came to NYU in 1986, I continued to teach classes across the finance spectrum, from corporate finance to valuation to investing, and I am glad that I did so. I am a natural dabbler, and I enjoy looking at big financial questions and ideas from multiple perspectives. There are two core classes that I have taught to the MBAs at Stern, almost every year since 1986. The first is corporate finance, a class about the first principles that should govern how to run a business, and thus a required class (in my biased view) for everyone in business.

If you are a business owner or operator, this class should give you the tools to use to make business choices that make the most financial sense. If you work in a business, whether it be in marketing, strategy or HR, this class is designed to provide perspective on how what you do fits into value creation at your business. If you are just interested in business, just as an observer, you may find this class useful in examining why companies do what they do, from acquisitions to buybacks, and when corporate actions violate common sense.

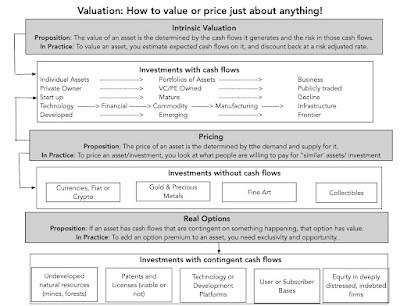

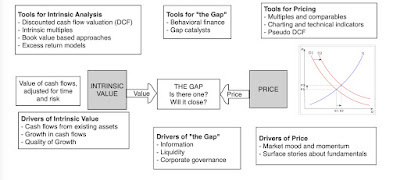

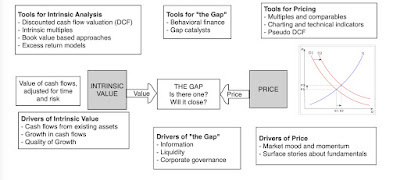

The second is valuation, a class about how to value or price almost anything, with a tool set for those who need to put numbers on assets.

Again, I teach this class to a broad audience, from appraisers/analysts whose jobs revolve around valuation/pricing to portfolio managers who are often users of analyst valuations to business owners, whose interests in valuation can range from curiosity (how much is my business worth?) to the transactional (how much of my business should I give up for a capital infusion?)

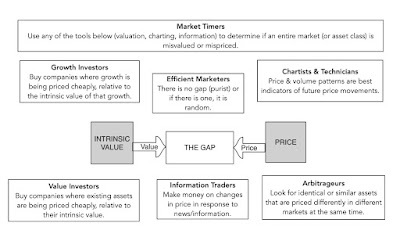

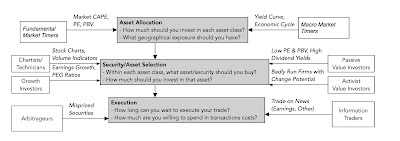

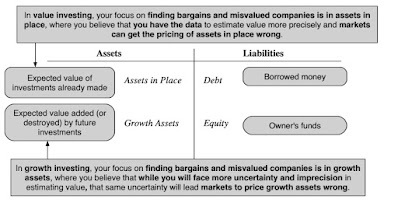

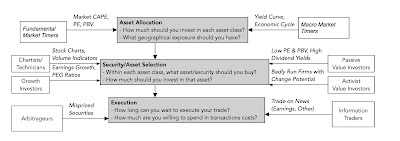

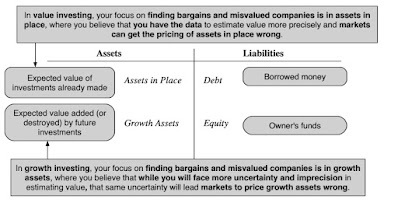

While my class schedule has been filled with these two courses, I developed a third course, investment philosophies, a class about how to approach investing, trying to explain why investors with very different market views and investment strategies can co-exist in a market, and why there is no one philosophy that dominates.

My endgame for this class is to provide as unbiased a perspective as I can for a range of philosophies from trading on price patterns to market timing, with stops along the way from value investing, growth investing and information trading. It is my hope that this class will allow you to find the investment philosophy that best fits you, given your financial profile and psychological makeup.

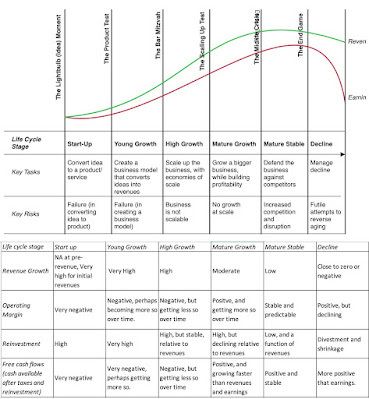

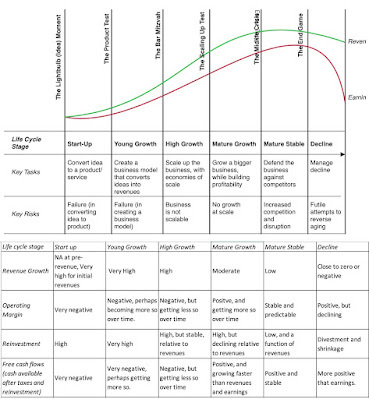

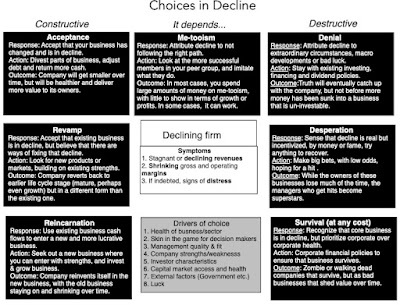

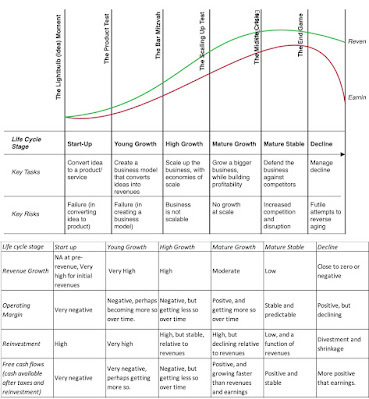

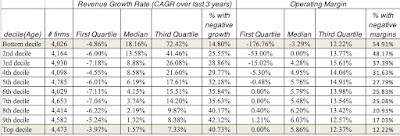

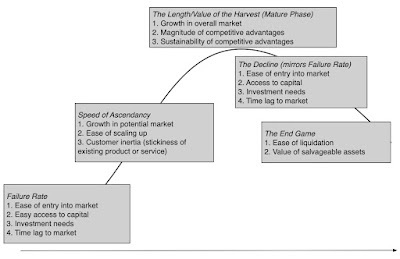

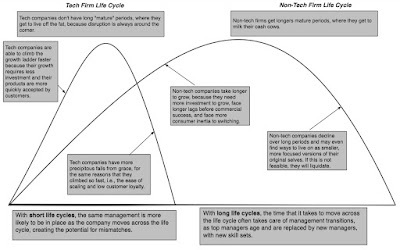

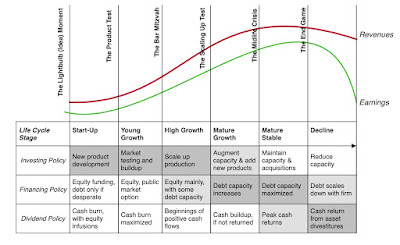

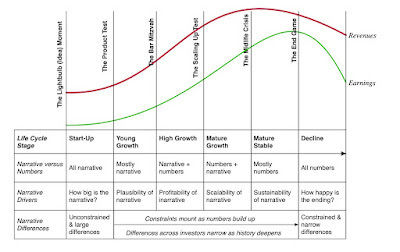

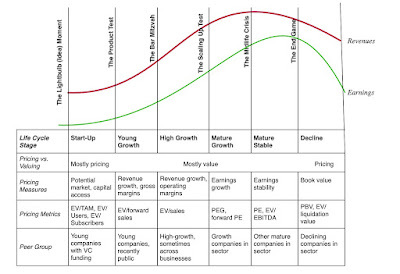

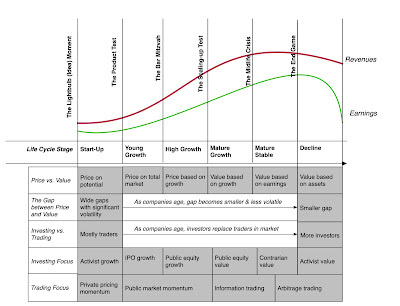

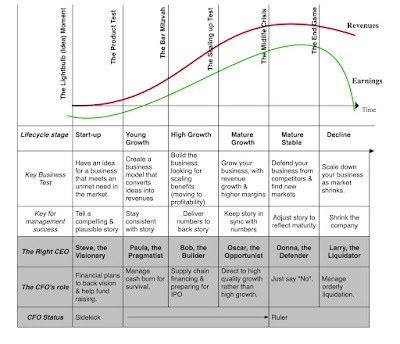

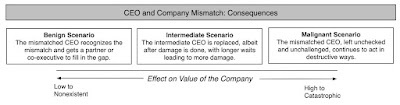

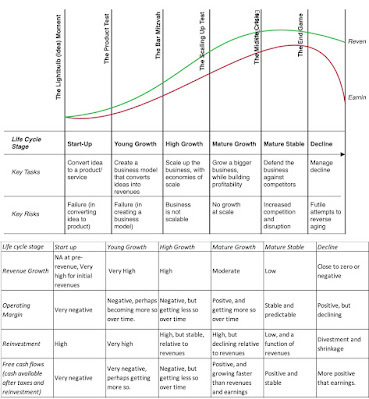

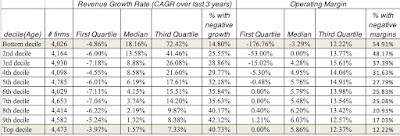

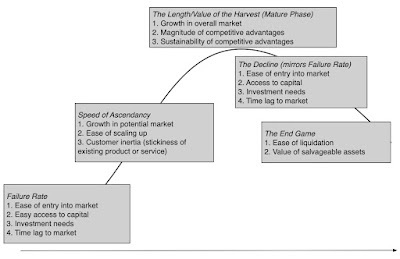

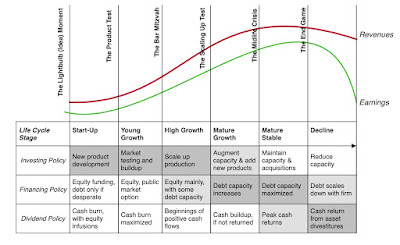

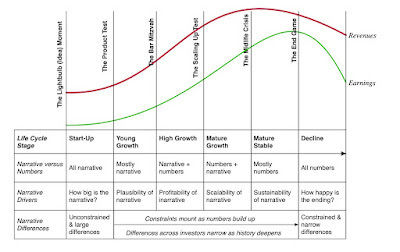

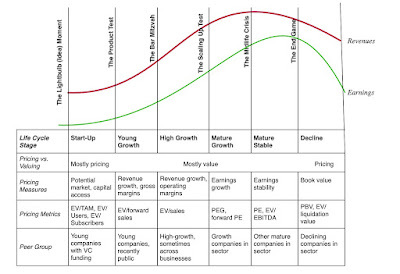

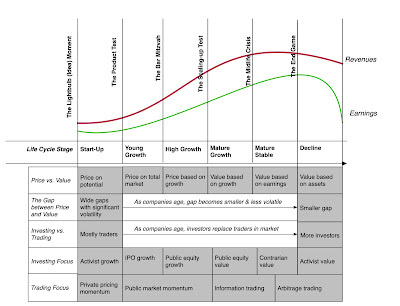

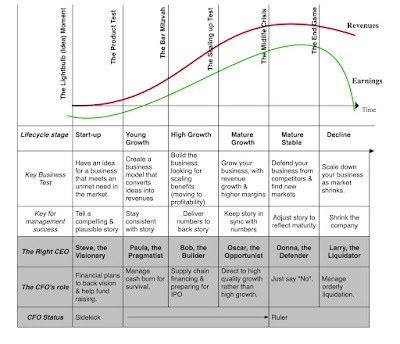

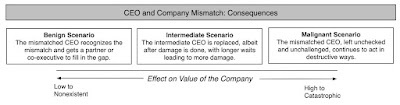

In 2024, I added a fourth course to the mix, one centered around my view that businesses age like human beings do, i.e., there is a corporate life cycle, and that how businesses operate and how investors value them, changes as they move from youth to demise.

I have used the corporate life cycle perspective to structure my thinking on almost every class that I teach, and in this class, I isolate it to examine how businesses age and how they respond to to aging, sometimes in destructive ways.

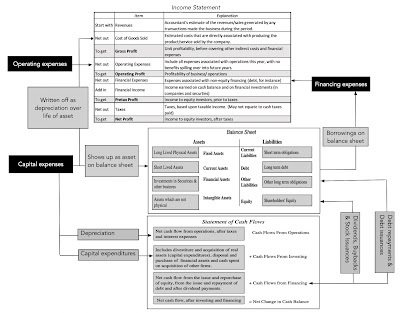

In my corporate finance and valuation classes, the raw material comes from financial statements, and I realized early on that my students, despite having had a class or two on accounting, still struggled with reading and using financial statements, and I created a short accounting class, specifically designed with financial analysis and valuation in mind. The class is structured around the three financial statements that embody financial reporting - the income statement, balance sheet and statement of cash flows - and how the categorization (and miscategorization) of expenses into operating, financing and capital expenses plays out in these statements.

As many of you who may have read my work know, I think that fair value accounting is not just an oxymoron but one that has done serious damage to the informativeness of financial statements, and I use this class to explain why.

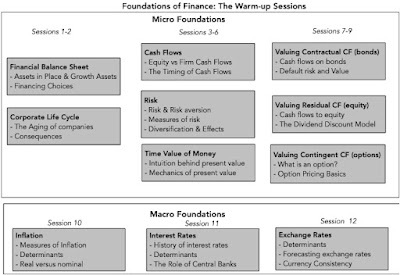

As many of you who may have read my work know, I think that fair value accounting is not just an oxymoron but one that has done serious damage to the informativeness of financial statements, and I use this class to explain why.Since so much of finance is built around the time value of money (present value) and an understanding of financial markets and securities, I also have a short online foundational class in finance:

As you can see, this class covers the bare basics of macroeconomics, since that is all I am capable to teaching, but in my experience, it is all that I have needed in finance.

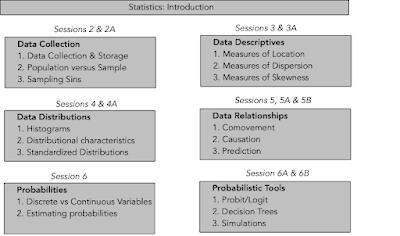

As you can see, this class covers the bare basics of macroeconomics, since that is all I am capable to teaching, but in my experience, it is all that I have needed in finance.As our access to financial data and tools has improved, I added a short course on statistics, again with the narrow objective of providing the basic tools of data analysis.

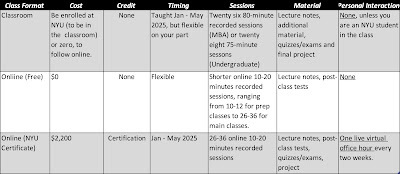

A statistics purist would probably blanch at my treatment of regressions, correlations and descriptive statistics, but as a pragmatist, I am willing to compromise and move along. As you browse through the content of these classes, and consider whether you want to take one, it is worth noting that they are taught in different formats. The corporate finance and valuation classes will be taught in the spring, starting in late January and ending in mid-May, with two eighty-minute sessions each week that will be recorded and accessible shorts after they are delivered in the classroom. There are online versions of both classes, and the investment philosophies class, that take the form of shorter recorded online classes (about twenty minutes), that you can either take for free on my webpage or for a certificate from NYU, for a fee.

The accounting, statistics and foundations classes are only in online format, on my webpage, and they are free. All in all, I know that some of you are budget-constrained, and others of you are time-constrained, and I hope that there is an offering that meeting your constraints.

If you are interested, the table below lists the gateways to each of the classes listed above. Note that the links for the spring 2025 classes will lead you to webcast pages, where there are no sessions listed yet, since the classes start in late January 2025. The links to the NYU certificate classes will take you to the NYU page that will allow you to enroll if you are interested, but for a price. The links to the free online classes will take you to pages that list the course sessions, with post-class tests and material to go with each session: table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }ClassNYU Spring 2025 Online (free)NYU CertificateWhatsApp Discussion Group Corporate FinanceLinkLinkLink (Fall)Link ValuationLinkLinkLink (Spring & Fall)Link Investment PhilosophiesNALinkLink (Spring)Link Corporate Life CycleNALinkNALink AccountingNALinkNA Foundations of FinanceNALinkNA StatisticsNALinkNA

The last column represents WhatsApp groups that I have set up for each class, where you can raise and answer questions from others taking the class.

My Book (and Written) Content Let me begin by emphasizing that you do not need any of my books to take my classes. In fact, I don't even require them, when I teach my MBA and undergraduate classes at NYU. The classes are self contained, with the material you need in the slides that I use for each class, and these slides will be accessible at no cost, either as a packet for the entire class or as a link to the session (on YouTube). To the extent that I use other material, spreadsheets or data in each session, the links to those as well will be accessible as well.

If you prefer to have a book, I do have a few that cover the classes that I teach, though some of them are obscenely overpriced (in my view, and there is little that I can do about the publishing business and its desire for self immolation.) You can find my books, and the webpages that support these books, at this link, and a description of the books is below:

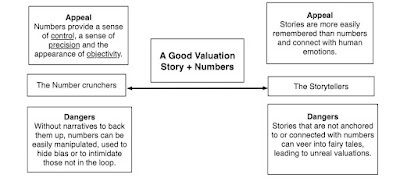

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }Corporate Finance Valuation Investment Philosophies Corporate Life Cycle Applied Corporate Finance (Wiley, 4th Ed): This is the book that is most closely tied to this class and represents my views of what should be in a corporate finance class most closely. Investment Valuation (Wiley, 3rd Ed, 4th ed forthcoming): This is my only valuation textbook, designed for classroom teaching. At almost 1000 pages, it is overkill but it is also the most comprehensive of the books in terms of coverage. Investment Philosophies (Wiley, 2nd Ed): This is the best book for this class, and provides background and evidence for each investment philosophy, with a listing of the personal characteristics that you need to make that philosophy work for you. Corporate Life Cycle (Penguin Random House, 1st Ed): This is the most recent of my books and it introduces the phases of the corporate life cycle and why business, management, valuation and investment challenges change with each phase. Corporate Finance (Wiley, 2nd Ed): This is a more conventional corporate finance book, but it has not seen a new edition in almost 20 years. Little Book of Valuation (Wiley, 2nd Ed): This is the shortest of the books, but it provides the essentials of valuation, and at a reasonable price. Investment Management (Wiley, 1st Ed): This is a very old book, and one that I co-edited with the redoubtable Peter Bernstein, focused on writings on different parts of the investment process. It is dated but it still has relevance (in my view). Strategic Risk Taking (Wharton, 1s Ed): This is a book specifically about measuring risk, dealing with risk and how risk taking/avoidance affect value. Dark Side of Valuation (Prentice Hall, 3rd Ed): This is a book about valuing difficult-to-value companies, from young businesses to cyclical/commodity companies. It is a good add-on to the valuation class. Investment Fables (FT Press, 1st Ed): This book is also old and badly in need of a second edition, which I may turn to next year, but it covers stories that we hear about how to beat the market and get rich quickly, the flaws in these stories, and why it pays to be a skeptic. Damodaran on Valuation (Wiley, 2nd Ed): This was my very first book, and it is practitioner-oriented, with the second half of the book dedicated to loose ends in vlauation (control, illiquidity etc.) Narrative and Numbers (Columbia Press, 1st Ed): This was the book I most enjoyed writing, and it ties storytelling to numbers in valuation, providing a basis for my argument that every good valuation is a bridge between stories and numbers.

Finally, I discovered early on how frustrating it is to be dependent on outsiders for data that you need for corporate financial analysis and valuation, and I decided to become self sufficient and create my own data tables, where I report industry averages on almost every statistic that we track and estimate in finance. These data tables should be accessible and downloadable (in excel), and if you find yourself stymied, when doing so, trying another browser often helps. The data is updated once a year, at the start of the year, and the 2025 data update will be available around January 10, 2025.

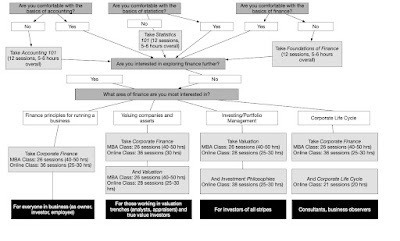

A Class Guide I would be delighted, if you decide to take one or more of my classes, but I understand that your lives are busy, with jobs, family and friends all competing for your time. You may start with the intent of taking a course, but you may not be able to finish for any number of reasons, and if that happens, I completely understand. In addition, the courses that you find useful will depend on your end game.If you own a business, work in the finance department of a company, or are a consultant, you may find the corporate finance course alone will suffice, providing most of what you need.If you are in the appraisal or valuation business, either as an appraiser or as an equity research analyst (buy or sell side), valuation is the class that will be most directly tied to what you will do. I do believe that to value businesses, you need to understand how to run them, making corporate finance a good lead in.If you plan to be in active investment, working at a mutual fund, wealth management or hedge fund, or are an individual investor trying to find your way in investing, I think that starting with a valuation class, and following up with investment philosophy will yield the biggest payoff.Finally, the corporate life cycle class, which spans corporate finance, valuation and investing, with doses of management and strategy, will be a good add on to any of the other pathways, or as a standalone for someone who has little patience for finance classes but wants a framework for understanding businesses.As a lead-in to any of these paths, I will leave it to you to decide whether you need to take the accounting, statistics, and foundations classes, to either refresh content you have not seen in a long time or because you find yourself confused about basics:

If you find yourself overwhelmed with any or all of these paths, you always have the option of watching a session or two of any class of your choice. As you look at the choices, you have to consider three realities. The first is that, unless you happen to be a NYU Stern student, you will be taking these classes online and asynchronously (not in real time). As someone who has been teaching online for close to two decades now, I have learned that watching a class on a computer or display screen is far more draining than being in a physical class, which is one reason that I have created the online versions of the classes with much shorter session lengths. The second is that the biggest impediment to finishing classes online, explaining why completion rates are often 5% or lower, even for the best structured online classes, is maintaining the discipline to continue with a class, when you fall behind. While my regular classes follow a time line, you don't have to stick with that calendar constraint, and can finish the class over a longer period, if you want, but you will have to work at it. The third is that learning, especially in my subject area, requires doing, and if all you do is watch the lecture videos, without following through (by trying out what you have learned on real companies of your choosing), the material will not stick. I will be teaching close to 800 students across my three NYU classes, in the spring, and they will get the bulk of my attention, in terms of grading and responding to emails and questions. With my limited bandwidth and time, I am afraid that I will not be able to answer most of your questions, if you are taking the free classes online; with the certificate classes, there will be zoom office hours once every two weeks for a live Q&A. I have created WhatsApp forums (see class list above) for you, if you are interested, to be able to interact with other students who are in the same position that you are in, and hopefully, there will be someone in the forum who can address your doubts. Since I have never done this before, it is an experiment, and I will shut them down, if the trolls take over.

If you find yourself overwhelmed with any or all of these paths, you always have the option of watching a session or two of any class of your choice. As you look at the choices, you have to consider three realities. The first is that, unless you happen to be a NYU Stern student, you will be taking these classes online and asynchronously (not in real time). As someone who has been teaching online for close to two decades now, I have learned that watching a class on a computer or display screen is far more draining than being in a physical class, which is one reason that I have created the online versions of the classes with much shorter session lengths. The second is that the biggest impediment to finishing classes online, explaining why completion rates are often 5% or lower, even for the best structured online classes, is maintaining the discipline to continue with a class, when you fall behind. While my regular classes follow a time line, you don't have to stick with that calendar constraint, and can finish the class over a longer period, if you want, but you will have to work at it. The third is that learning, especially in my subject area, requires doing, and if all you do is watch the lecture videos, without following through (by trying out what you have learned on real companies of your choosing), the material will not stick. I will be teaching close to 800 students across my three NYU classes, in the spring, and they will get the bulk of my attention, in terms of grading and responding to emails and questions. With my limited bandwidth and time, I am afraid that I will not be able to answer most of your questions, if you are taking the free classes online; with the certificate classes, there will be zoom office hours once every two weeks for a live Q&A. I have created WhatsApp forums (see class list above) for you, if you are interested, to be able to interact with other students who are in the same position that you are in, and hopefully, there will be someone in the forum who can address your doubts. Since I have never done this before, it is an experiment, and I will shut them down, if the trolls take over.In Closing…

I hope to see you (in person or virtually) in one of my classes, and that you find the content useful. If you are taking one of my free classes, please recognize that I share my content, not out of altruism, but because like most teachers, I like a big audience. If you are taking the NYU certificate classes, and you find the price tag daunting, I am afraid that I cannot do much more than commiserate, since the university has its own imperatives. If you do feel that you want to thank me, the best way you can do this is to pass it on, perhaps by teaching someone around you.

YouTube Video

Class list with linksCorporate Finance (NYU MBA): https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/webcastcfspr25.htm Valuation (NYU MBA): https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/webcasteqspr25.htm Corporate Finance (Free Online): https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/adamodar/New_Home_Page/webcastcfonline.htm Valuation (Free Online): https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/webcastvalonline.htm Corporate Finance (NYU Certificate): https://execed.stern.nyu.edu/products/corporate-finance-with-aswath-damodaran Valuation (NYU Certificate): https://execed.stern.nyu.edu/products/advanced-valuation-with-aswath-damodaran Investment Philosophies (Free Online): https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/webcastinvphil.htm Investment Philosophies (NYU Certificate): https://execed.stern.nyu.edu/products/investment-philosophies-with-aswath-damodaran Corporate Life Cycle (Free Online): https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/webcastCLC.htm Accounting 101 (Free Online): https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/webcastacctg.htm Foundations of Finance (Free Online): https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/webcastfoundationsonline.htm Statistics 101 (Free Online): https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/webcaststatistics.htmWhatsApp Groups for Classes

Corporate Finance: https://chat.whatsapp.com/C0yjIAWT2WdLozCHYctU9pValuation: https://chat.whatsapp.com/LjQBQXcbyh11I17idz176kInvestment Philosophies: https://chat.whatsapp.com/IolVsa3qScLJecUtu4uUKOCorporate Life Cycle: https://chat.whatsapp.com/J1V0vwFkIUoCblYp4J3ENs

November 14, 2024

The Siren Song of Sustainability: The Theocratic Trifecta's Third Leg!

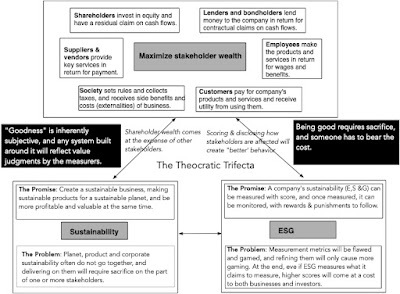

You might know, by now, of my views on ESG, which I have described as an empty acronym, born in sanctimony, nurtured in hypocrisy and sold with sophistry. My voyage with ESG began with curiosity in my 2019 exploration of what it purported to measure, turned to cynicism as the answers to the Cui Bono (who benefits) question became clear and has curdled into something close to contempt, as ESG advocates rewrote history and retroactively changed their measurements in recent years. Late last year, I looked at impact investing, as a subset of ESG investing, and chronicled the trillions put into fighting climate change, and the absence of impact from that spending. Sometime before these assessments, I also looked at the notion of stakeholder wealth maximization as an idea that only corporate lawyers and strategists would love, and argued that there is a reason, in conventional businesses to stay focused on shareholders. With each of these topics (ESG, impact investing, stakeholder wealth maximization), the response that I got from some of the strongest defenders was that "sustainability" is the ultimate end game, and that the fault has been in execution (in ESG and impact investing), and not in the core idea.

I was curious about what sets sustainability apart from the critiqued ideas, as well as skeptical, since the cast of characters (individual and entities) in the sustainability sales pitch seems much the same as for the ESG and impact investing sales pitches. In critiquing sustainability, I may be swimming against the tide, but less so than I was five years ago, when I first wrote about these issues. In fact, in my first post on ESG, I confessed that I risked being labeled as a "moral troglodyte" for my views, and I am sure that my subsequent posts have made that a reality, but I have a thick skin. This post on sustainability will, if it is read, draw withering scorn from the righteous, and take me off their party invite list, but I don't like parties anyway.

Sustainability: The What, the Why and the Who?

I have been in business and markets for more than four decades, and while sustainability as an end game has existed through that period, but much of that time, it was in the context of the planet, not for businesses. It is in the last two decades that corporate sustainability has become a term that you see in academic and business circles, albeit with definitions that vary across users. Before we look at how those definitions have evolved, it is instructive to start with three measures of sustainability, measuring (in my view) very different things:

Planet sustainability, measuring how our actions, as consumers and businesses, affect the planet, and our collective welfare and well being. This, of course, covers everything from climate change to health care to income inequality.Product sustainability, measuring how long a product or service from a business can be used effectively, before becoming useless or waste. In a throw-away world, where planned obsolescence seems to be built into every product or service, there are consumers and governments who care about product sustainability, albeit for different reasons.Business or corporate sustainability, measuring the life of a business or company, and actions that can extend or constrict that life. There are corporate sustainability advocates who will argue that it covers all of the above, and that a business that wants to increase its sustainability has to make more sustainable products, and that doing so will improve planet sustainability. That may be true, in some cases, but in many, there will be conflicts. A company that makes shaving razors may be able to create razor blades that stay sharp forever, and need no replacement, but that increased product sustainability may crimp corporate sustainability. In the same vein, there may be some companies (and you can let your priors guide you in naming them), whose very existence puts the planet at risk, and if planet sustainability is the end game, the best thing that can happen is for these companies to cease to exist.Which of these measures of sustainability lies at the heart of corporate sustainability, as practiced today? To get the answers, I looked at a variety of players in the sustainability game, and will use their own words in the description, lest I be accused of taking them out of context:

Business schools around the world have discovered that sustainability classes not only draw well, and improve their rankings (especially with the Financial Times, which seems to have a fetish with the concept), but are also money makers when constructed as executive classes. NYU, the institution that I teach at, has an executive corporate sustainability course, with certification costing $2,200, but I will quote the Vanderbilt University course description instead, where for a $3,000 price tag, you can get a certificate in corporate sustainability, which is described as " a holistic approach to conducting business while achieving long-term environmental, social, and economic sustainability." Academia: I read through seminal and impactful (as academics, we are fond of both words, with the latter measured in citations) papers on corporate sustainability, to examine how they defined and measured sustainability. A 2003 paper on corporate sustainability describes it as recognizing that "corporate growth and profitability are important, it also requires the corporation to pursue societal goals, specifically those relating to sustainable development — environmental protection, social justice and equity, and economic development." In the last two decades, it is estimated that there have been more than twelve thousand articles published on corporate sustainability, and while the definition has remained resilient, it has developed offshoots and variants.Corporate/Business: Companies, around the world, were quick to jump onto the sustainability bandwagon, and sustainability (or something to that effect) is part of many corporate mission statements. The Hartford, a US insurance company, describes corporate sustainability as centered "around developing business strategies and solutions to serve the needs of our stakeholders, while embracing the necessary innovation and foresight to ensure we are able to meet those needs in the decades to come."Governments: Governments have also joined the party, and the EU has been the frontrunner, and its definition of corporate sustainability as "integrating social, environmental, ethical, consumer, and human rights concerns into their business strategy and operations" has become the basis for both disclosure and regulatory actions. The Canadian government has used to EU model to create a corporate sustainability reporting directive, requiring companies to report on and spend more on a host on environmental, social and governance indicators. I am willing to be convinced otherwise, but all of these definitions seem to be centered around planet sustainability, with varying motivations for why businesses should act on that front, from clean consciences (it is the right thing to do) to being "good for business" (if you do it, you will become more profitable and valuable).

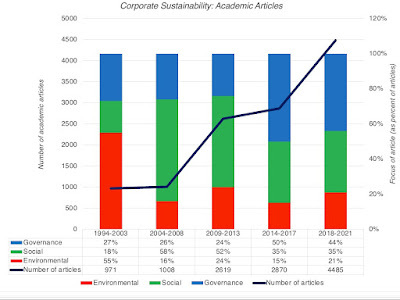

While corporate sustainability has taken center stage in the last two decades, it is part of a discussion about the social responsibilities of businesses that has been around for centuries. From Adam Smith's description of economics as the "gospel of mammon" in the 1700s to Milton Friedman's full-throated defense of business in the 1970s, it can be argued that almost every debate about businesses has included discussions of what they should do for society, beyond just following the law. That said, corporate sustainability (and its offshoots) have clearly taken a more central role in business than ever before, and one manifestation is in the rise of "corporate sustainability officers" (CSOs) at many large companies. A PwC survey of 1640 companies in 62 countries, in 2022, found that the number of companies with CSOs tripled in 2021, with about 30% of all companies having someone in that position. A Conference Board survey of hundred sustainability leaders (take the sample bias into account) of the state of corporate sustainability pointed to the expectation that sustainability teams at companies would continue to grow over time. Finally, going back to academia, an indicator of the buzz in buzzwords, a survey paper in 2022 noted the rise in the number of corporate-sustainability related articles in recent years, as well as documenting their focus:

Burbano, Delma and Cobo (2022)

Burbano, Delma and Cobo (2022)

Note that much of the surge in articles came from ESG, which at least for the bulk of this period marched in lockstep with sustainability. Reflecting that twinning, many of the papers on corporate sustainability, just like the papers on ESG, were framed as sustainability being not just good for society but also good for the companies that adopted them.

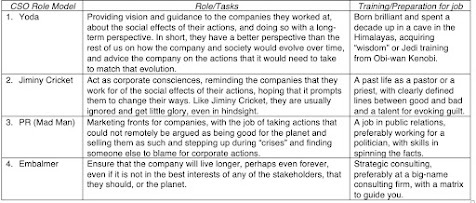

I will admit that I have no idea what a CSO is or does, but I did get a chance to find out for myself, when I was invited to give a talk to the CSOs of fifty large companies. I started that session with a question, born entirely out of curiosity, to the audience of what they did, at their respective organizations. After about twenty minutes of discussion, it was very clear that there was no consensus answer. In fact, some were as in the dark, as I was, about a CSO's responsibilities and role, and among the many and sometimes convoluted and contradictory answers I heard, here was my categorization of potential CSO roles:CSO as Yoda: Some of the CSOs described their role as providing vision and guidance to the companies they worked at, about the societal effects of their actions, and doing so with a long term perspective. In short, even though they did not make this explicit, they were projecting that they had the training and foresight on how the company and society would evolve over time, and advice the company on the actions that it would need to take to match that evolution. I was tempted, though I restrained myself, to ask what training they had to be such receptacles of wisdom, since a degree or certification in sustainability clearly would not do the trick. I did dig into Star Wars lore, where it is estimated that it takes a decade or two of intense training to become a Jedi, and left open the possibility that there may be an institution somewhere that is turning out sustainability jedis.CSO as Jiminy Cricket: I am a fan of Disney movies, and Pinocchio, while not one of the best known, remains one of my favorites. If you have watched the movie, Jiminy Cricket is the character that sits on Pinocchio's shoulder and acts as his conscience, and for some of the CSOs in the audience, that seemed to be the template, i.e., to act as corporate consciences, reminding the companies that they work for, of the social effects of their actions. The problem, of course, is that like the Jiminy Cricket in the movie, they get tagged as relentless scolds, usually get ignored, and get little glory, even when proved right. CSO as PR Genius: There were a few CSOs who were open about the fact that they were effectively marketing fronts for companies, with the job of taking actions that could not remotely be argued as being good for the planet and selling them as such. I am not sure whether Unilever's CSO was involved in the process, but the company's push to have each of its four hundred brands have a social or environmental purpose would have fallen into this realm. CSO as Embalmer: Finally, there were some CSOs who argued that it was their job to ensure that the company would live longer, perhaps even forever. Like the embalmers who promised the Egyptian pharaohs everlasting life, if they wrapped themselves in bandages and buried themselves in crypts, these CSOs view longer corporate lives as the end game, and act accordingly. If you are familiar with my work on corporate life cycles, I believe that not much good comes from companies surviving as “walking dead” entities, but in a world where survival at any cost is viewed as success, it is a by product. Here are the roles in table form, with the training that would prepare you best for each one:

I am sure that I am missing some of the nuance in sustainability, but if so, remember that nuance does not survive well in business contexts, where a version of Gresham's law is at work, with the worst motives driving out the best.

Sustainability and ESG In the last two or three years, corporate sustainability advocates have tried to separate themselves from ESG, arguing that the faults of ESG are of its own doing, and came from ignoring sustainability lessons. I am sorry, but I don't buy it. If ESG did not exist, sustainability would have had to invent it, because much of the growth in sustainability as a concept and in practice has come from its ESG arm. As I see it, ESG took the noble sounding words of corporate sustainability and converted them into a score, and it was that much maligned scoring mechanism that caused a surge of adoptions both in corporate boardrooms and in investment funds. To complete the linkage, both ESG and sustainability draw on stakeholder wealth maximization, with the core thesis that businesses should be run for the benefit of all stakeholders, rather than “just” for shareholders. It is in this context that I used the "theocratic trifecta" to describe how ESG, sustainability and stakeholder wealth are linked, and have been marketed.

I use of the word “theocrat” deliberately, since like the theocrats of yore, some in these spaces believe that they own the high ground on virtue, and view dissent as almost sacrilegious.

I use of the word “theocrat” deliberately, since like the theocrats of yore, some in these spaces believe that they own the high ground on virtue, and view dissent as almost sacrilegious. While the ESG scoring mechanism, by itself, can be viewed as having a good purpose, i.e., to create a measure of how much a company is moving towards it sustainability goals, and to hold it accountable, it creates the natural consequences that come with all scoring mechanisms:Measurers claiming to be objective arbiters, when the truth is that all scores require subjective judgments about what comprises goodness, and the consequences for business profitability and value.Businesses that start to understand the scoring process and factors, and then game the scoring systems to improve their scores. Greenwashing is a feature of these scoring systems, not a bug, and the more you try to refine the scoring, the more sophisticated the gaming will become.Advocates wringing their hands about the gaming, and arguing that the answer is more detailed definitions of things that defy definition, not recognizing (or perhaps not caring) that this just feeds the cycle and creates even more gaming.With ESG, we have seen this process play out in destructive ways, with scores varying across services for the same companies, significant gaming around ESG scoring and more disclosure, but with little to show in tangible benefits for society. In fact, taking a step back and looking at ESG and sustainability as concepts, they share many of the same characteristics:They are opaque: Both ESG and sustainability are opaque to the point of obfuscation, perhaps because it serves the interests of advocates, who can then market them in whatever form they want to. To the pushback from defenders that the details are being nailed down or that there are new standards in place or coming, the argument runs hollow because the end game seems to keep changing. With ESG, for instance, the end game when it was initiated was making the world a better place (doing good), which evolved to generating alpha (excess returns for investors), on to being a risk measure before converting on a disclosure requirement. Defenders argue that there will be convergence driven by tighter definitions from regulators and rule makers, and the EU, in particular, has been in the lead on this front, putting out a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) in 2022, outlining economic activities that contribute to meeting the EU’s environmental objectives. While ESG advocates may be right about convergence, looking to the the bureaucracy in Brussels to have the good sense (on economics and sustainability) to get this right is analogous to asking a long-time vegan where you can get the best steak in town. They are rooted in virtue: While some of the advocates for ESG and sustainability have now steered away from goodness as an argument for their use, almost every debate about the two topics eventually ends up with advocates claiming to own the high ground on virtue, with critics consigned to the other side. Disclosures, over actions: The path for purpose-driven concepts (sustainability, ESG) seems to follow a familiar arc. They start with the endgame of making the world a better place, are marketed with the pitch that purpose and profits go together (the original sin) and when the the lie is exposed, are repackaged as being about disclosures that can be used by consumers and investors to make informed judgments. Both ESG and sustainability have traversed this path, and both seem to be approaching the "it's all about disclosure" component. While that seems like a reasonable outcome, since almost everyone is in favor of more information, there are two downsides to this disclosure drive. The first is that disclosure can become not just a substitute for acting, but an impediment to the change that makes a difference. The second is that as disclosures become more extensive, there is a tipping point, especially as the consequential disclosures are mixed in with minor ones, where users start ignoring the disclosure, effectively removing their information value. Underplay or ignore sacrifice: Of all the mistakes, the biggest one made in the sales pitch for ESG and sustainability was that you could eat your cake, and have it too. Companies were told that being sustainable would make them more profitable and valuable, investors were sold on the notion that investing in good companies would deliver higher or extra returns and consumers were informed that they could make sustainable choices, with little or no additional cost. The truth is that sustainability will be costly to businesses, investors, and consumers, and why should that surprise us? Through history, being good has always required sacrifice, and it was always hubris to argue that you could upend that history, with ESG and sustainability.Notwithstanding the money, time and resources that have been poured into ESG and sustainability, there is little in terms of real change on any of the social or climate problems that they purport to want to change.

Can sustainability be saved?

I may be a moral troglodyte, because of my views on ESG, sustainability and all things good, but I want my children and grandchildren to live in a better world than the one that I lived in. Put simply, we have a shared interest in making the world a better place, and that leads to the question of whether corporate sustainability, or at least the mission that it espouses, can be saved. I believe that there is a path forward, but it requires steps that many sustainability purists may find anathema:

Be clear eyed about what can be achieved at the business level: There is truth to the Milton Friedman adage that the business of business is business, not filling in for social needs or catering to non-business interests. It is true that there are actions that businesses take that can create costs to society, and even if the law does not require it, it behooves us all to get businesses to behave better. That said, the danger of overreaching here, and asking businesses to do what governments and regulators should be doing, is that it is not just ineffective but counter-production. For business sustainability to deliver results, it has to make that line (between business and government action) clearer.Open about the costs to businesses of meeting sustainability goals: Start being real about the sacrifices in profitability and value that will be needed for a company to do what's good for society. To the extent that in a publicly traded company, it is not the managers, but one of the stakeholders (shareholders, bondholders, employees or customer), who bear this cost, you need buy in from them, of the sustainability actions are voluntary. For companies that are well managed and have delivered success for their owners, the sacrifice may be easier to sell, but for badly managed businesses, it will be and should be a steep hill to climb. To the extent that corporate executives and fund managers have chosen the path of virtue, at a cost to their shareholders and investors, without their buy in, there is clearly a violation of fiduciary duty that will and should leave them exposed to legal consequences.Clear about who bears these costs: I was recently asked to give testimony to a Canadian parliamentary committee that was considering ways of getting banks to contribute to fighting climate change (by lending less to fossil fuel companies and more to green energy firms), and much of what I heard from committee members and the other experts was about how banks would bear the costs. The truth is that when a bank is either restricted from a profit-making activity or forced to subsidize a money-losing activity, the costs are borne by either the bank's shareholders or depositors, or, in some cases, by taxpayers. In fact, given that bank equity is such a small slice of overall capital, I argued that it bank depositors who will be burdened the most by bank lending mandates. And honest about cost sharing: One of the benefits of recognizing that being good (for the planet or society) creates costs is that we can then also follow up by looking at who bears the costs. It is my view that for much of the past few decades, we (as academics, policy makers and regulators) been far too quick to decide what works for the "greater good", at least as we see it, and much too blind to the reality that the costs of delivering that greater good are borne by the people who can least afford it. Above all, drain the gravy train: Drawing on a biblical theme, both ESG and sustainability have been contaminated by the many people and entities that have benefited monetarily from their existence. The path to making sustainability matter has to start by removing the grifters, many masquerading as academics and experts, from the space. I won’t name names, but if you want to see who you should be putting on that grifter list, many of them will be at the annual extravaganza called COP29, where the useful idiots and feckless knaves who inhabit this space will fly in from distant places to Azerbaijan, to lecture the rest of us on how to minimize our carbon footprint. If you are a business that cares about the planet, fire your sustainability consultants, stop listening to sustainability advisors or bending business models to meet CSRD needs, and fall back on common sense, and while you are at it, you may want to get rid of your CSO (if you have one), unless you have Yoda on your payroll. In all of this discussion, there is a real problem that no one in the space seems to be willing to accept or admit to, and that is much as we (as consumers, investors and voters) claim to care about social good, we are unwilling to burden ourselves, even slightly (by paying higher prices or taxes), to deliver that good. It could be because we are callous, or have become so, but I think the true reason is that we have lost trust in governments and institutions, and who can blame us? Whether it is the city of San Diego, where I live, trying to increase sales taxes by half a percent or a government imposing a carbon tax, taxpayers seem disinclined to given governments the benefit of doubt, given their history of inefficiencies and broken promises. One argument that I have heard from many advocates for ESG and sustainability is that the pushback against these ideas is coming primarily from the United States, and that much of the rest of the world has bought in their necessity and utility. That is nonsense! I would suggest that these people leave the ivory towers and echo chambers that they inhabit, and talk to people in their own environs. There are many reasons that incumbent governments in Canada and France (both "leaders" in the climate change fight) are facing the political abyss in upcoming elections, but one reason is the "we know best" arrogance embedded in their climate change strictures and laws, combined with the insulting pitch that the people most affected by these laws will not feel the pain. How do we get trust in institutions back? It will not come from lecturing people on their moral shortcomings (as many will undoubtedly do to me, after reading this) or by gaslighting them (telling them that they are better off when they are clearly and materially not). It will require humility, where the agents of change (academics, governments, regulators) are transparent about what they hope to accomplish, and the costs of and uncertainties about reaching those objectives, and patience, where incremental change takes precedence over seismic or revolutionary change.

YouTube Video

My posts on ESG, impact investing and stakeholder wealthFrom Shareholder Wealth to Stakeholder Interests: CEO Capitulation or Empty Doublespeak? (August 2019)Sounding Good or Doing Good? A Skeptical Look at ESG (September 2020)The ESG Movement: The "Goodness" Gravy Train Rolls On! (September 2021)ESG's Russia Test: Trial by Fire or Crash and Burn? (March 2022)Good Intentions, Perverse Outcomes: The Impact of Impact Investing (October 2023)

November 7, 2024

The Wisdom and Madness of Crowds: Market Prices as Political Predictors!

In this, the first full week in November 2024, the big news stories of this week are political, as the US presidential election reached its climactic moment on Tuesday, but I don't write about politics, not because I do not have political views, but because I reserve those views are for my friends and family. The focus of my writing has always been on markets and companies, more micro than macro, and I am sure that you will find my spouting off about who I voted for, and why, off-putting, much as I did in his cycle, when celebrities and sports stars told me their voting plans. This post, though, does have a political angle, albeit with a market twist. During the just-concluded presidential election, we saw election markets, allowing you to predict almost every subset of the election, not only open up and grow, but also insert themselves into the political discourse. I would like to use this post to examine how these markets did during the lead in to the election, and then expand the discussion to a more general one of what markets do well, what they do badly, i.e., revisit an age-old divide between those who believe in the wisdom of crowds and and those that point to their madness.

Election Forecasts: From polls to political markets

I watched the movie "Conclave"just a couple of days ago, and it is about the death of a pope, and the meeting to pick a replacement. (It is based on a book by Robert Harris, one of my favorite authors.) In the movie, as the hundred-plus Catholic cardinals gathered in the Sistine chapel, to pick a pope, I was struck by how the leading candidates gauged support and jockeyed ahead of the election, essentially informally polling their brethren. I know that the movie (and book) is fiction, but I am sure that the actual conclaves that have characterized papal succession for centuries have used informal polling as a way of forecasting election winners for centuries. In fact, going back to the very first democracies in Greek and Roman times, where notwithstanding the restrictions on who could vote, there were attempts to assess election winners and losers, ahead of the event.

The first reported example of formal polling occurred ahead of the 1824 presidential election, when the Raleigh Star and North Carolina Gazette polled 504 voters to determine (rightly) that Andrew Jackson would beat John Quincy Adams. Starting in 1916, The Literary Digest started a political survey, asking its readers, and after correctly predicting the next four elections, failed badly in 1936 (predicting that Alf Landon would beat FDR in the election that year, when, in fact, he lost in a landslide). While polling found its statistical roots after that, it had one of its early dark moments, in 1948, when pollsters predictions that Thomas Dewey would beat Harry Truman were upended on Election Day, leading to one of the most famous headlines of all time (in the Chicago Tribune). In the decades after, polling did learn valuable lessons about sampling bias and with an assist from technological advancements, and the number of pollsters has proliferated. Coming into this century, pollsters were convinced that they had largely ironed out their big problems, but even at it peak, polls came with noise (standard errors), though pollsters were not always transparent about it, and the public took polling estimates as facts.

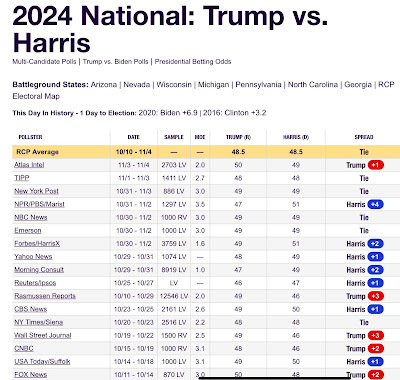

The fact that individual polls, even if not biased, are noisy (with ranges around estimates) led to a poll aggregators, which collected individual polls and averaged them out to yield presumably a more precise estimate. Here, for example, is the aggregated value from Real Clear Politics (RCP), which has been doing this for at least four presidential election cycles now, leading into election days in the US (November 5):

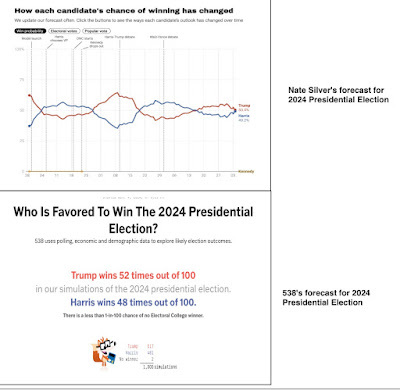

The pushback in poll-based forecasting (whether individual or aggregated) is that it may miss fundamentals on voter history and predilections, and in the last three cycles, there have been a few polling pundits who have used polling aggregates and their presumably deeper understanding of fundamentals to make judgments on who will win the election. Two are the best known are 538.com, a site that used to be part of the New York Times but is now owned by ABC, and Nate Silver's personal assessment, and leading into the election, here were their assessments for the election:

Both arrive at their estimates using Monte Carlo simulations, based upon data fed into the system. Note that polls, aggregated polls and poll judgment calls have run into problems in the last decade, some of which may be insurmountable. The first is the advent of smartphones (replacing land lines) and call screening allows callers to not answer some call, and polls have had to struggle with the consequences for sampling bias. The second is that a segment of the population has become tough, if not impossible, to poll, sometimes lying to pollsters, and to the extent that they are more likely to be for one side of the political divide, there will be systematic error in polls that will not average out, and those errors feed into polling judgments.

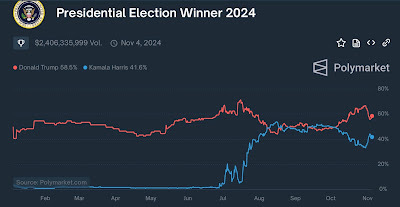

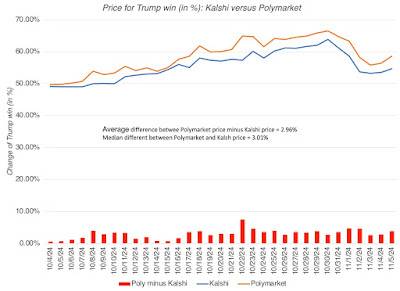

With poll-based forecasts being less reliable and trusted, a vacuum opened up leading into the 2024 elections, and political markets have stepped into the gap. While it has always been possible to bet on elections, either in Las Vegas or through UK-based betting sites like Betfair, they are odd-driven, opaque and restricted. In contrast, Polymarket opened markets on US election outcomes (president, senate, by state, etc.), and through much of 2024, it has given watchers a measure of what investors in that market thought about who would win the election. In the graph below, you can see the Polymarket prices for a "Trump win" and a "Harris win" in the months leading into the election:

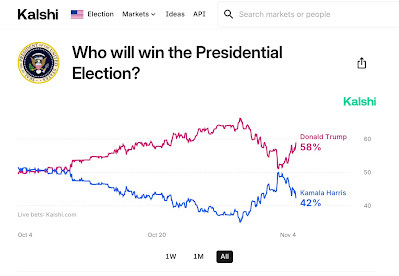

Note that until July, it was Joe Biden who was the democratic nominee for president, and the only portion of the graph that is relevant is the section starting in late July, when Kamala Harris became the nominee. Mid-year, Polymarket was joined by Kalshi, structured very similarly, with slightly different rules on trading and transactions costs, and that market's assessment of who would win the market is below:

Since both markets existed in tandem for the months leading into the election, there were intriguing questions that emerged. The first is that at almost every point in time, in the months that they have co-existed, the prices for a Trump or Harris win on the two pricing platforms were different, with the prices on Kalshi generally running a little lower than on Polymarket for a Trump win.

In theory, this looks like an arbitrage opportunity, where you could buy the Trump win on the cheaper market and sell it on the more expensive one, but the transactions costs (1-2% in both markets) would have made them tough to pull off.The second is that within each market, there were a proliferation of contracts covering the same outcome, trading at different prices. For instance, on Polymarket, you could buy a Trump win contract for one price, a a Republican win contract at a slightly higher price, leading into just last week, but that difference could just reflect concerns on mortality.Do the actual results vindicate political markets? At least on this election, the answer is nominally yes, since the political markets attached a higher probability for a decisive victory for Trump in the electoral college than did the poll aggregators or judgments. However, political markets did not expect Trump to win the popular vote, which he may end up doing (some states are still counting), and that can be taken as evidence that markets can be surprised sometimes. In the weeks leading into the election, there were two dimensions on which political markets varied from the polls and aggregators. On the plus side, the political markets were more dynamic, reflecting in real time, responses to events like the debates, interviews and endorsements; Polymarket's odds of a Trump win dropped by almost 10% after the debate. On the minus side, political markets were much more volatile than the polls, with swings driven sometimes by large trades; the Wall Street Journal highlighted one trader who put almost $30 million into the market on the Trump win, pushing up the price.

The Wisdom of Crowds

That trust in crowd judgments in guiding our actions is not restricted to politics. In an earlier part of this post, I talked about going to the movies, and it is indicative of the times we live in that my movie choice was made, not by reading movie reviews on the newspaper, but by movie ratings on Rotten Tomatoes. Once the movie was done, the restaurant choice I made was determined by Yelp reviews, and without boring you further, you can see this pattern unfold as you think about how you choose the products you buy on Amazon or even the services (plumbing, electrical, landscaping) that you go with, as a consumer. On a less personal and larger scale, the block chains that underlie Bitcoin transactions represent a crowd sourcing of the checking process (performed by institutions like banks conventionally), and you can argue that trusting social media to deliver you information is essentially crowd-sourcing your news.

With these examples, you can see one of the dangers of crowd judgments, and that is that in all the crowds described above (Rotten Tomatoes, Yelp, Amazon product reviews and social media), there is no cost to entry, or to offer an opinion, and that can dilute the power of the judgments. In every one of these sites, you can game the system to give high ratings to awful movies and terrible restaurants, and social media news can be filled with distortions. With markets, we introduce an entry fee to those who want to join the crowd in the form of price, and demand more money to amplify those views. In the words of Nassim Taleb, opinionated people with no skin in the game can make outlandish predictions, often with no accountability. If you don't believe me, watch the parade of experts and market gurus on any financial television channel, and notice how they are allowed to conveniently gloss over their own forecasts and predictions from earlier periods. In contrast, no matter what you think about the experience or motivations of traders on a market, they have to put money behind their views.

When you use the price in a market as an assessment of the likelihood of an event, which is what you are implicitly doing when you trust Polymarket or Kashi prices as predictors of election winners, you are, in effect, trusting the crowd (albeit a selective one of those who trade on these markets) to be closer to the right outcome than polling experts or opinion leaders. When market price based forecasts are offered as alternatives to expert forecasts, the push back that you get is that experts have a deeper knowledge of what is being predicted. So, why do we trust and attach weight to the prices that investors assess for something? There are three reasons:

Information aggregation: One of the almost magical aspects of well-functioning markets is how pieces of information possessed by individual traders about whatever is being traded get aggregated, delivering a composite price that is effectively a reflection of all of the information. Real time adjustments to news: While experts (rightfully) take their time to absorb new information and reflect that information in their assessments, markets do not have the luxury of waiting. Consequently, markets react in real time, often in the moment, to events as they unfold, and studies that look at that reaction find that they often not only beat experts to the punch but deliver better assessments. Law of large numbers: It is true that individual traders in a markets can make mistakes, often big ones, in their assessments of value, and can sometimes also let their preconceptions and biases drive their trading. To the extent that these mistakes and biases can lie on both sides, they will average out, allowing the "right' price to emerge from several wrong judgments.There is also a strand of research that is developing on the forecasting abilities of experts versus amateurs and it is not favorable for the former. Phil Tetlock, co-author of the book on super forecasting, chronicles the dismal record of expert forecasts, and argues that the best forecasts come from foxes (knows many things, but not in depth) and not hedgehogs (with deep expertise in the discipline). To the extent that a market is filled with amateurs, with very different knowledge and skill sets, Tetlock's work can be viewed as being supportive of market-based forecasts.

The Madness of Crowds

Well before we had Rotten Tomatoes and Twitter were conceived, we had financial markets, and not surprisingly, much of the most interesting research on crowd behavior has come from looking at those markets.. Our experience there is that while markets allow for information aggregation and consensus judgments that are almost magical in their timeliness and assessment quality, they are also capable of making mistakes, sometimes monumental ones. One of my favorite books is Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Markets, published in 1841, and it chronicles how market mistakes form and grow, using the South Sea Bubble and the Tulip Bulb Craze as illustrative examples. To those who believe that markets have somehow evolved since then to avoid these mistakes, behavioral finance provides the counter, which is that the behavioral quirks that gave rise to those bubble are still present, and may actually be amplified by technology and large platforms. The falsehood that was born in a pub in the South Sea bubble often looks weeks to work its way into market prices, but the same falsehood on a large social media platform today could affect prices almost instantaneously.

Without making this a treatise on behavioral finance, here are some of the problems that can lead markets off course, and make prices poor predictors of outcomes:

Noise drowns out information: In finance, we use noise as a term to capture all of the stories and influences that should have no effect on value, but that can still affect prices. While noise exists in even the best-functioning markets, there is enough information in those markets to offset the noise effect, and bring prices back into sync with value. However, if noise is the dominant force in a market, it can drown out information, causing prices to delink from information. Momentum versus Fundamentals: On a related note, it is worth remembering that the strongest force in markets is momentum, where price movements are driven more by price movements in past periods, than by fundamentals. While in a well-functioning market, that momentum will be checked by bargain hunters (if the price is pushed too low) or short sellers (if it is pushed too high), a market where one or the other of these players is either rare or non-existent can see momentum run rampant. It is one reason that I think that markets that restrict short selling, often labeling it as speculation, are creating the condition for market madness.Participant bias: While markets require skin in the game from traders, that requires money, and that biases markets against people with little or no money. In political markets, for instance, it could be argued that the traders on Polymarket and Kalshi represent a subset of the population (younger, better off) that may differ from the voting population. Market Manipulation: The history of financial markets also includes clear cases where markets have been manipulated, to deliver profits to the manipulators. That problem becomes worse in markets with limited liquidity, where big trades can move prices, and where market insiders have access to data that outsiders do not. Illiquidity: All of the problems listed above become greater in a market where liquidity is light, since a large trade, whether motivated by noise, momentum or manipulation, will move prices more. Feedback loop: There are times where market prices can affect the fundamentals, and through them, the value of what is being traded. With publicly traded companies, a higher stock price, for instance, may allow the companies to issue shares at these higher prices, to finance investments and acquisitions. With the political markets, this feedback loop manifested itself in my social media feeds, where I often saw the Polymarket or Kashi charts being used by candidates to convince potential voters that they were winning (to get them to jump on the bandwagon) or losing (to get people to give them money).Political markets are young, attract a subset of participants, and have limited liquidity (though it did improve over the course of the months), and there were clearly times in the weeks leading in to the election, where crowd madness overwhelmed crowd wisdom. On a optimistic note, these markets are not going away, and it is almost certain that there will be more traders in these markets in the next go-around and that some of the frictions will decrease.To "crowd" or not to "crowd"

I am convinced that in making our choices as consumers and citizens, we will be facing the choice between market-based assessments and expert assessment on more and more dimensions of our life. Thus, our weather forecasts may no longer come from meteorologists, but from a weather market where weather traders will tell us what tomorrow's temperature will be or how much snow will be delivered by a snow storm. As we face these choices, there will be two camps about whether market prices should be trusted. One, rooted in the wisdom of markets, will push us to accept more crowd-sourcing and crowd-judgments, and the other, building on market madness, will point to all the things that markets can get wrong.

While I do believe that, in balance, the wisdom will offset the madness in most markets, there are places where I will stay wary, as a user of market prices. Put simply, rather than view this as an either/or choice, consider using both a market pricing, if available, and a professional assessment. In the context of my discipline, which is valuation, I use both market assessment of country default risk, in the form of sovereign CDS spreads, and sovereign ratings, from the ratings agencies. The latter have more knowledge and expertise, but they are also slow to react to changes on the ground, and I am glad that I have market prices to fill in that gap. If you are planning to trade on these markets, I would hope you will heed my admonition from this post, where I argued that if you are buying or selling something that has no cash flows, you can only trade, not value, it. In the context of political markets, the price that you are paying is a function of probabilities of outcomes and your capacity to make money in the market will come from you being able to assess those probabilities better than the rest of the market.

There is another use for these political market securities that you may want to consider. To the extent that you feel emotionally invested in one candidate winning, and you don't have much faith in your probability assessments, you may want to consider buying shares in the other candidate. That way, no matter what the outcome, you will have a partially offsetting benefit; a win for your candidate will make you happy, but you will lose some money on your political market bet, and a loss for your candidate may be emotionally devastating, but you may be able to soothe your pain with a financial windfall.

YouTube Video

Political Market Links

PolymarketKalshiBook LinksExtraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of MarketsConclave (Robert Harris)October 1, 2024

Just do it! Brand Name Lessons from Nike'sTroubles!

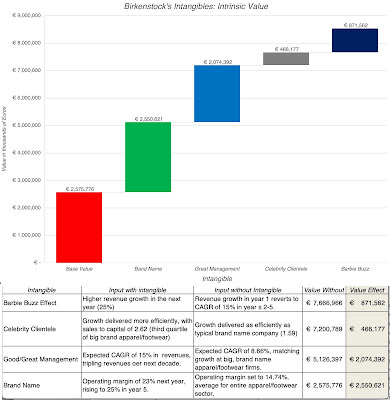

I have spent the last week reading "Shoe Dog", Phil Knight's memoir of how a runner on the Oregon University track team built one of the great shoe companies in the world, in Nike. In addition to its entertainment value, and it is a fun book to read, I read it for two storylines. The first is the time, effort and grit that it took to build a business, in a world where risk capital was more difficult to access than it has been in this century, and in a business where scaling up posed significant challenges. The second is the building of a brand name, with a mix of happy accidents (from the naming of the company to the creation of the swoosh as the company's symbol to its choice of slogan), good timing and great merchandising all playing a role in creating one of the great brand names in apparel and footwear. The latter assessment led a more general consideration of what constitutes a brand name, what makes a brand name valuable and what causes brand name values to deplete and disappear. Of course, since my attention was drawn to Nike in the first place, because of a change at the top the company and talk of brand name malaise, I tried my hand at valuing Nike in 2024, along the way.

Brand Name - What is it?

The broadest definition of a brand name is that it is recognized (by employees, consumers and the market) and remembered, either because of familiarity (because of brand name longevity) or association (with advertising or a celebrity). That definition, though, is not particularly useful since remembering or recognizing a brand, by itself, tells you nothing about its value. After all, almost everyone has heard or recognizes AT&T as a brand/corporate name, but as someone who is a cell service and internet customer of AT&T, I can assure you that neither of those choices were driven by brand name. The essence of brand name value is that the recognition or remembrance of a brand name changes how people behave in its presence. With customers, brand name recognition can manifest itself in buying choices (affecting revenues and revenue growth) or willingness to pay a higher price (higher profit margins). With capital providers, it may allow for lower funding costs, with equity investors pricing equity higher and lenders accepting lower interest rates and/or fewer lending covenants. For the moment, this may seem abstract and subjective, but in the next section, we will flesh out brand name effects on operating metrics and value more explicitly.

Corporate, Product and Personal Brand Names

Brand names can attach to entire companies, to particular products or brands, or even to personnel and people. With a company like Coca Cola, it is the corporate brand name that has the most power, but the soft drink beverages marketed by the company (Coca Cola, Fanta, Sprite, Dasani etc.) each have their own brand names. With companies like Unilever, the corporate brand name takes a back seat to the brands names of the dozens of products controlled by the company, which include Dove (soap), Axe (deodorant), Hellman's (mayonnaise) and Close-up (toothpaste), just to name a few. There are clearly cases of people with significant brand name value, in sports (Ohtani in baseball, Messi in soccer, Kohli in cricket) and entertainment (Taylor Swift, Beyonce), with a spill over to the entities that attach themselves to these people. In fact, a critical component of Nike's brand name was put in place in 1984, when the company signed on Michael Jordan, in his rookie season as a basketball player, and reaped benefits as he became the sport's biggest star over the next decade.

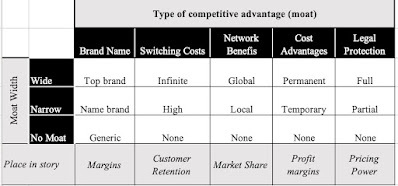

Brand names and other Competitive Advantages

One reason that brand name discussions often lose their focus is that companies are quick to bundle a host of competitive advantages, each of which may be valuable, in the brand name grouping. The table below, where I have loosely borrowed from Morningstar and Michael Porter is one way to think about both the types and sustainability of competitive advantages:

Companies like Walmart and Aramco have significant competitive advantages, but I don't think brand name is on the top five list. Walmart's strengths come from immense economies of scale and bargaining power with suppliers, and Aramco's value derives from massive oil reserves, with far lower costs of extraction, than any of its competitors. Google and Facebook control the advertising business, because they have huge networking benefits, i.e., they become more attractive destinations for advertisers as they get bigger, explaining why they were so quick to change their corporate names, and why it has had so little effect on value. The pharmaceutical companies have some brand name value, but a bigger portion of their value added comes from the protection against competition they get from owning patents. While this may seem like splitting hairs, since all competitive advantages find their way into the bottom line (higher earnings or lower risk), a company that mistakes where its competitive advantages come from risks losing those advantages.

Brand Name Value

At the risk of drawing backlash from marketing experts and brand name consultants, I will start with my "narrow" definition of brand name. In arriving at this definition, I will fall back on a structure where I connect the value of a business to key drivers, and look at how brand name will affect these drivers:

Put simply, brand name value can show up in almost every input, with a more recognizable (and respected) brand name leading to more sales (higher revenues and revenue growth), more pricing power (higher margins), and perhaps even less reinvestment and less risk (lower costs of capital and failure risk). That said, the strongest impact of brand name is on pricing power, with brand name in its purest form allowing it's owner to charge a higher price for a product or service than a competitor could charge for an identical offering. To illustrate, I walked over to my neighborhood pharmacy, and compared the prices of an over-the-counter pain killer (acetaminophen), in its branded form (Tylenol) and its generic version (CVS) :

The ingredients, in case you are wondering, are exactly the same, leading to the interesting question, more psychological than financial, of why anyone would pay an extra $2.50 for a product with no differentiating features. If you are wondering how this plays out at the business level, the operating margins of pharmaceutical companies that own the "brand names" are significantly higher than the brand names of companies that make just the generic substitutes.

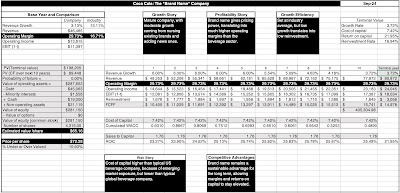

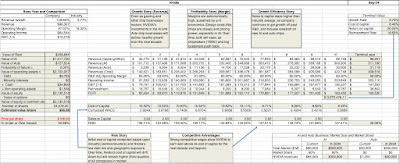

The Tylenol example also serves to illustrate when it is easiest to value brand name, i.e., when it is the only competitive advantage, and when it will become difficult to do, i.e., when it has many competitive advantages. It is for that reason that valuing brand name is easier to do at a beverage or cereal company, such as Coca Cola or Kellogg's, where there is little to differentiate across products other than brand name, and you can attribute the higher margins almost entirely to brand name. It is at the basis for my valuation of Coca Cola's brand name in the picture below, where I value the company with its current operating margin:

Coca Cola valuation

Note that while the company comes in as slightly overvalued, it is still given a value of $281.15 billion, with much of that value coming from its pre-tax operating margin of 29.73%. We estimate the value of Coca Cola's brand name in two steps, first comparing to a weighted average margin off 16.75% for soft-drink beverage companies, where many of the largest companies are themselves branded (Pepsi, Dr. Pepper etc.), albeit with less pricing power than Coca Coal and then comparing to the median operating margin of 6.92%, skewed towards smaller and generic beverage companies listed globally:

Coca Cola valuation

Coca Cola valuation