Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 2

February 23, 2025

Data Update 8 for 2025: Debt, Taxes and Default - An Unholy Trifecta!

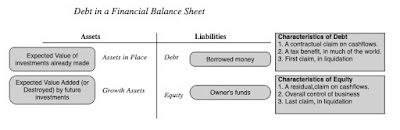

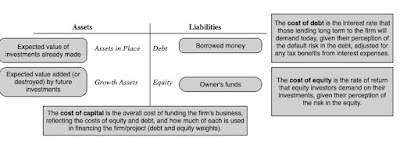

The Debt Trade off As a prelude to examining the debt and equity tradeoff, it is best to first nail down what distinguishes the two sources of capital. There are many who trust accountants to do this for them, using whatever is listed as debt on the balance sheet as debt, but that can be a mistake, since accounting has been guilty of mis-categorizing and missing key parts of debt. To me, the key distinction between debt and equity lies in the nature of the claims that its holders have on cash flows from the business. Debt entitles its holders to contractual claims on cash flows, with interest and principal payments being the most common forms, whereas equity gives its holders a claim on whatever is left over (residual claims). The latter (equity investors) take the lead in how the business is run, by getting a say in choosing who manages the business and how it is run, while lenders act, for the most part, as a restraining influence.

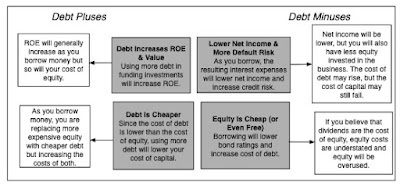

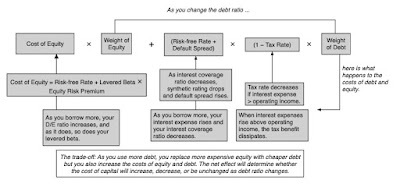

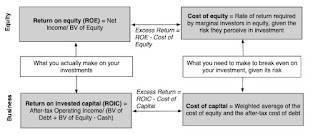

Using this distinction, all interest-bearing debt, short term and long term, clears meets the criteria for debt, but for almost a century, leases, which also clearly meet the criteria (contractually set, limited role in management) of debt, were left off the books by accountants. It was only in 2019 that the accounting rule-writers (IFRS and GAAP) finally did the right thing, albeit with a myriad of rules and exceptions. Every business, small or large, private or public and anywhere in the world, faces a question of whether to borrow money, and if so, how much, and in many businesses, that choice is driven by illusory benefits and costs. Under the illusory benefits of debt, I would include the following:Borrowing increases the return on equity, and is thus good: Having spent much of the last few decades in New York, I have had my share of interactions with real estate developers and private equity investors, who are active and heavy users of debt in funding their deals. One reason that I have heard from some of them is that using debt allows them to earn higher returns on equity, and that it is therefore a better funding source than equity. The first part of the statement, i.e., that borrowing money increases the expected return on equity in an investment, is true, for the most part, since you have to contribute less equity to get the deal done, and the net income you generate, even after interest payments, will be a higher percentage of the equity invested. It is the second part of the statement that I would take issue with, since the higher return on equity, that comes with more debt, will be accompanied by a higher cost of equity, because of the use of that debt. In short, I would be very skeptical of any analysis that claims to turn a neutral or bad project, funded entirely with equity, into a good one, with the use of debt, especially when tax benefits are kept out of the analysis.The cost of debt is lower than the cost of equity: If you review my sixth data update on hurdle rates, and go through my cost of capital calculation, there is one inescapable conclusion. At every level of debt, the cost of equity is generally much higher than the cost of debt for a simple reason. As the last claimants in line, equity investors have to demand a higher expected return than lenders to break even. That leads some to conclude, wrongly, that debt is cheaper than equity and more debt will lower the cost of capital. (I will explain why later in the post.)Under the illusory costs of debt, here are some that come to mind:Debt will reduce profits (net income): On an absolute basis, a business will become less profitable, if profits are defined as net income, if it borrows more money. That additional debt will give rise to interest expenses and lower net income. The problem with using this rationale for not borrowing money is that it misses the other side of debt usage, where using more debt reduces the equity that you will have to invest.Debt will lower bond ratings: For companies that have bond ratings, many decisions that relate to use of debt will take into account what that added debt will do to the company’s rating. When companies borrow more money, it may seem obvious that default risk has increased and that ratings should drop, because that debt comes with contractual commitments. However, remember that the added debt is going into investments (projects, joint ventures, acquisitions), and these investments will generate earnings and cash flows. When the debt is within reasonable bounds (scaling up with the company), a company can borrow money, and not lower its ratings. Even if bond ratings drop, a business may be worth more, at that lower rating, if the tax benefits from the debt offset the higher default risk.Equity is cheaper than debt: There are businesspeople (including some CFOs) who argue that debt is cheaper than equity, basing that conclusion on a comparison of the explicit costs associated with each – interest payments on debt and dividends on equity. By that measure, equity is free at companies that pay no dividends, an absurd conclusion, since investors in equity anticipate and build in an expectation of price appreciation. Equity has a cost, with the expected price appreciation being implicit, but it is more expensive than debt.The picture below captures these illusory benefits and costs:

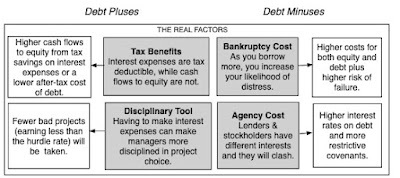

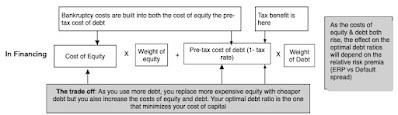

If the above listed are illusory reasons for borrowing or not borrowing, what are the real reasons for companies borrowing money or not borrowing? The two primary benefits of borrowing are listed below:Tax Benefits of Debt: The interest expenses that you have on debt are tax deductible in much of the world, and that allows companies that borrow money to effectively lower their cost of borrowing:

After-tax cost of debt = Interest rate on debt (1 – tax rate)

In dollar terms, the effect is similar; a firm with a 25% tax rate and $100 million in interest expenses will get a tax benefit of $25 million, from that payment.Debt as a disciplinary mechanism: In some businesses, especially mature ones with lots of earnings and cash flows, managers can become sloppy in capital allocation and investment decisions, since their mistakes can be covered up by the substantial earnings. Forcing these companies to borrow money, can make managers more disciplined in project choices, since poor projects can trigger default (and pain for managers).These have to be weighted off against two key costs:Expected bankruptcy costs: As companies borrow money, the probability that they will be unable to make their contractual payments on debt will always increase, albeit at very different rtes across companies, and across time, and the expected bankruptcy cost is the product of this probability of default and the cost of bankruptcy, including both direct costs (legal and deadweight) and indirect costs (arising from the perception that the business is in trouble).Agency costs: Equity investors and lenders both provide capital to the business, but the nature of their claims (contractual and fixed for debt versus residual for equity) creates very different incentives for the two groups. In short, what equity investors do in their best interests (taking risky projects, borrow more money or pay dividends) may make lenders worse off. As a consequence, when lending money, lenders write in covenants and restrictions on the borrowing businesses, and those constraints will cause costs (ranging from legal and monitoring costs to investments left untaken).The real trade off on debt is summarized in the picture below:

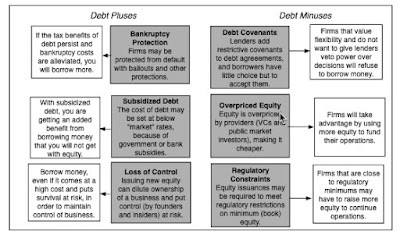

While the choices that businesses make on debt and equity should be structured around expected tax benefits (debt’s biggest plus) and expected bankruptcy costs (debt’s biggest minus), businesses around the world are affected by frictions, some imposed by the markets that they operate in, and some self-imposed. The biggest frictional reasons for borrowing are listed below:Bankruptcy protections (from courts and governments): If governments or courts step in to protect borrowers, the former with bailouts, and the latter with judgments that consistently favor borrowers, they are nullifying the effect of expected bankruptcy costs in restraining companies from borrowing too much. Consequently, companies in these environments will borrow much more than they should.Subsidized Debt: If lenders or governments lend money to firms at below-market reasons for reasons of virtue (green bonds and lending) or for political/economic reasons (governments lending to companies that choose to keep their manufacturing within the domestic economy), it is likely that companies will borrow much more than they would have without these debt subsidies.Corporate control: There are companies that choose to borrow money, even though debt may not be the right choice for them, because the inside investors in these companies (family groups, founders) do not want to raise fresh equity from the market, concerned that the new shares issued will reduce their power to control the firm. The biggest frictional reasons for holding back on borrowing include:Debt covenants: To the extent that debt comes with restrictions, a market where lender restrictions are more onerous in terms of the limits that they put on what borrowers can or cannot do will lead to a subset of companies that value flexibility borrowing less.Overpriced equity: To the extent that markets may become over exuberant about a company's prospects, and price its equity too highly, they also create incentives for these firms to overuse equity (and underutilize debt). Regulatory constraints: There are some businesses where governments and regulators may restrict how much companies operating in them can borrow, with some of these restrictions reflecting concerns about systemic costs from over leverage and others coming from non-economic sources (religious, political).The debt equity trade off, in frictional terms, is in the picture below:

As you look through these trade offs, real or frictional, you are probably wondering how you would put them into practice, with a real company, when you are asked to estimate how much it should be borrow, with more specificity. That is where the cost of capital, the Swiss Army Knife of finance that I wrote about in my sixth data update update, comes into play as a debt optimizing tool. Since the cost of capital is the discount rate that you use to discount cash flows back to get to a value, a lower cost of capital, other things remaining equal, should yield a higher value, and minimizing the cost of capital should maximize firm. With this in place, the “optimal” debt mix of a business is the one that leads to the lowest cost of capital:

You will notice that as you borrow more money, replacing more expensive equity with cheaper debt, you are also increasing the costs of debt and equity, leading to a trade off that can sometimes lower the cost of capital and sometimes increase it. This process of optimizing the debt ratio to minimize the cost of capital is straight forward, and if you are interested, this spreadsheet will help you do this for any company.

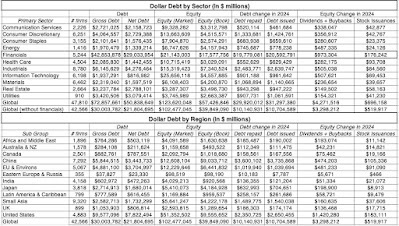

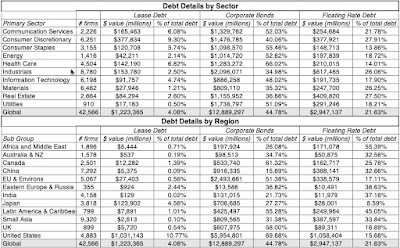

Measuring the Debt Burden With that tradeoff in place, we are ready to examine how it played out in 2024, by looking at how much companies around the world borrowed to fund their operations. We can start with dollar value debt, with two broad measures – gross debt, representing all interest-bearing debt and lease debt, and net debt, which nets cash and marketable securities from gross debt. In 2024, here are the gross and net debt values for global companies, broken down by sector and sub-region:

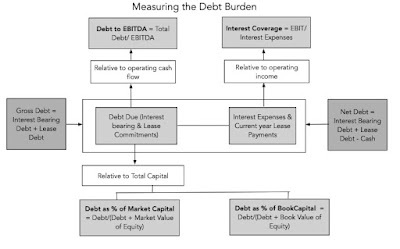

The problem with dollar debt is that absolute values can be difficult to compare across sectors and markets with very different values, I will look at scaled versions of debt, first to total capital (debt plus equity) and then then to rough measures of cash flows (EBITDA) and earnings (EBIT). The picture below lists the scaled versions of debt:

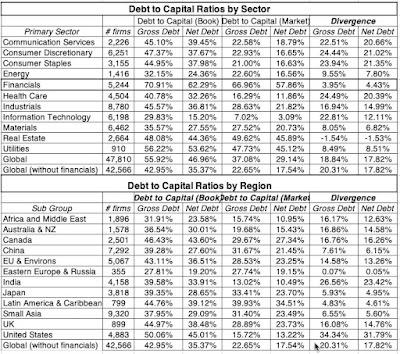

Debt to Capital: The first measure of debt is as a proportion of total capital (debt plus equity), and it is this version that you use to compute the cost of capital. The ratio, though, can be very different when you use book values for debt and equity then when market values are used. The table below computes debt to capital ratios, in book and market terms, by sector and sub-region:

Debt to Capital: The first measure of debt is as a proportion of total capital (debt plus equity), and it is this version that you use to compute the cost of capital. The ratio, though, can be very different when you use book values for debt and equity then when market values are used. The table below computes debt to capital ratios, in book and market terms, by sector and sub-region:

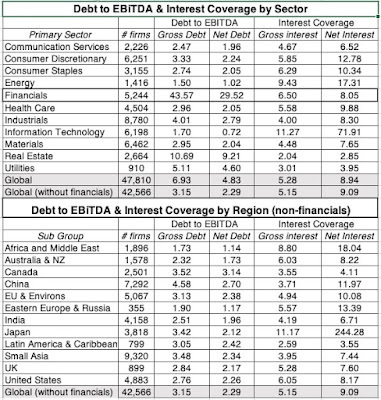

I would begin by separating the financial sector from the rest of the market, since debt to banks is raw material, not a source of capital. Breaking down the remaining sectors, real estate and utilities are the heaviest users of debt, and technology and health care the lightest. Across regions, and looking just at non-financial firms, the US has the highest debt ratio, in book value terms, but among the lowest in market value terms. Note that the divergence between book and market debt ratios in the last two columns varies widely across sectors and regions.Debt to EBITDA: Since debt payments are contractually set, looking at how much debt is due relative to measure of operating cash flow making sense, and that ratio of debt to EBITDA provides a measure of that capacity, with higher (lower) numbers indicating more (less) financial strain from debt.Interest coverage ratio: Interest expenses on debt are a portion of the contractual debt payments, but they represent the portion that is due on a periodic basis, and to measure that capacity, I look at how much a business generates as earnings before interest and taxes (operating income), relative to interest expenses. In the table below, I look at debt to EBITDA and interest coverage ratios, by region and sector:

I would begin by separating the financial sector from the rest of the market, since debt to banks is raw material, not a source of capital. Breaking down the remaining sectors, real estate and utilities are the heaviest users of debt, and technology and health care the lightest. Across regions, and looking just at non-financial firms, the US has the highest debt ratio, in book value terms, but among the lowest in market value terms. Note that the divergence between book and market debt ratios in the last two columns varies widely across sectors and regions.Debt to EBITDA: Since debt payments are contractually set, looking at how much debt is due relative to measure of operating cash flow making sense, and that ratio of debt to EBITDA provides a measure of that capacity, with higher (lower) numbers indicating more (less) financial strain from debt.Interest coverage ratio: Interest expenses on debt are a portion of the contractual debt payments, but they represent the portion that is due on a periodic basis, and to measure that capacity, I look at how much a business generates as earnings before interest and taxes (operating income), relative to interest expenses. In the table below, I look at debt to EBITDA and interest coverage ratios, by region and sector:

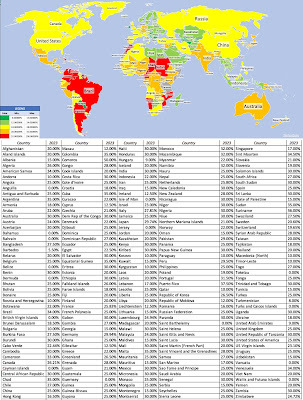

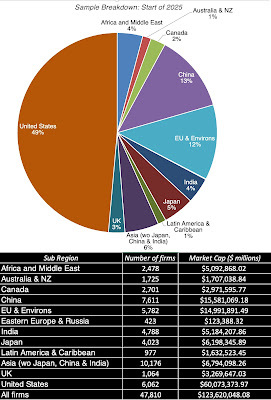

The results in this table largely reaffirm our findings with the debt to capital ratio. Reda estate and utilities continue to look highly levered, and technology carries the least debt burden. Across regions, the debt burden in the US, stated as a multiple of EBITDA or looking at interest coverage ratios, puts it at or below the global averages, whereas China has the highest debt burden, relative to EBITDA.The Drivers and Consequences of Debt As you look at differences in the use of debt across regions and sectors, it is worth examining how much of these differences can be explained by the core fundamentals that drive the debt choice – the tax benefits of debt and the bankruptcy cost. The tax benefit of debt is the easier half of this equation, since it is directly affected by the marginal tax rate, with a higher marginal tax rate creating a greater tax benefit for debt, and a greater incentive to borrow more. Drawing on a database maintained by PWC that lists marginal tax rates by country, I create a heat map:

The results in this table largely reaffirm our findings with the debt to capital ratio. Reda estate and utilities continue to look highly levered, and technology carries the least debt burden. Across regions, the debt burden in the US, stated as a multiple of EBITDA or looking at interest coverage ratios, puts it at or below the global averages, whereas China has the highest debt burden, relative to EBITDA.The Drivers and Consequences of Debt As you look at differences in the use of debt across regions and sectors, it is worth examining how much of these differences can be explained by the core fundamentals that drive the debt choice – the tax benefits of debt and the bankruptcy cost. The tax benefit of debt is the easier half of this equation, since it is directly affected by the marginal tax rate, with a higher marginal tax rate creating a greater tax benefit for debt, and a greater incentive to borrow more. Drawing on a database maintained by PWC that lists marginal tax rates by country, I create a heat map:

Download corporate tax rates, by country

Download corporate tax rates, by country

The country with the biggest changes in corporate tax policy in the world, for much of the last decade, has been the United States, where the federal corporate tax rate, which at 35%, was one of the highest in the world prior to 2017, saw a drop to 21% in 2017, as part of the first Trump tax reform. With state and local taxes added on, the US, at the start of 2025, had a marginal corporate tax rate of 25%, almost perfectly in line with a global norm. The 2017 tax code, though, will sunset at the end of 2025, and corporate tax rates will revert to their old levels, but the Trump presidential win has not only increased the odds that the 2017 tax law changes will be extended for another decade, but opened up the possibility that corporate tax rates may decline further, at least for a subset of companies.

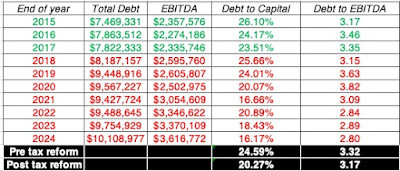

An interesting question, largely unanswered or answered incompletely, is whether the US tax code change in 2017 changed how much US companies borrowed, since the lowering of tax rates should have lowered the tax benefits of borrowing. In the table below, I look at dollar debt due at US companies every year from 2015 to 2024, and the debt to EBITDA multiples each year:

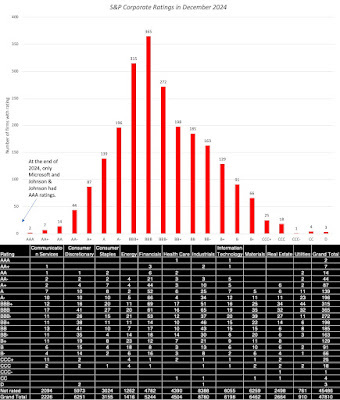

The most commonly used measure of default risk is corporate bond ratings, since ratings agencies respond (belatedly) to concerns about default risk by downgrading companies. The graph below, drawing on data from S&P< looks at the distribution of bond ratings, from S&P, of rated companies, across the globe, and in the table below, we look at the breakdown by sector:

As you can see, the tax reform act has had only a marginal effect on US corporate leverage, albeit in the right direction. While the dollar debt at US companies has continued to rise, even after marginal tax rates in the US declines, the scaled version of debt (debt to capital ratio and debt to EBITDA have both decreased).

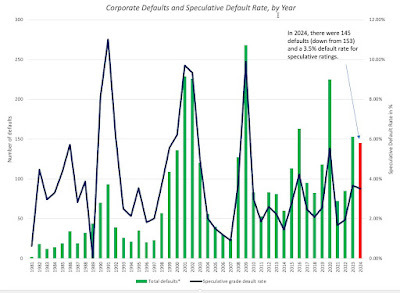

The ratings are intended to measure the likelihood of default, and it is instructive to look at actual default rates over time. In the graph below, we look at default rates in 2024, in a historical context:

S&P

S&PAs you can see in the graph, default rates are low in most periods, but, not surprisingly, spike during recessions and crises. With only 145 corporate defaults, 2024 was a relatively quiet year, since that number was slightly lower than the 153 defaults in 2023, and the default rate dropped slightly (from 3.6% to3.5%) during the year.

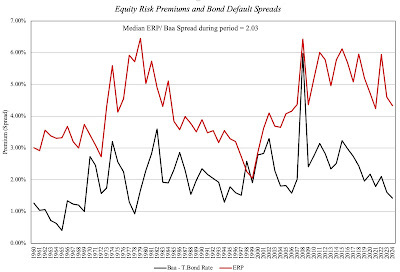

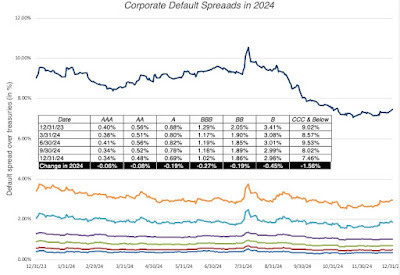

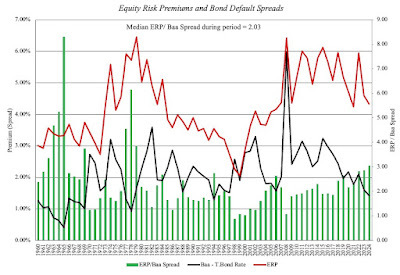

The default spread is a price of risk in the bond market, and if you recall, I estimated the price of risk in equity markets, with an implied equity risk premium, in my second data update. To the extent that the price of risk in both the equity and debt markets are driven by the endless tussle between greed and fear, you would expect them to move together much of the time, and as you can see in the graph below, I look at the implied equity risk premium and the default spread on a Baa rated bond:

Damodaran.com

Damodaran.comIn 2024, the default spread for a Baa rated dropped from 1.61% to 1.42%, paralleling a similar drop in the implied equity risk premium from 4.60% to 4.33%.

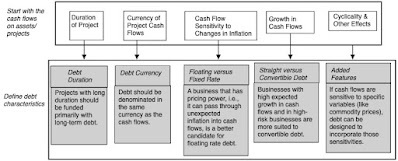

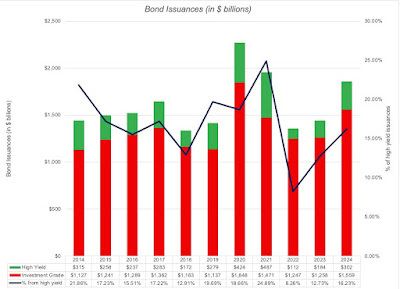

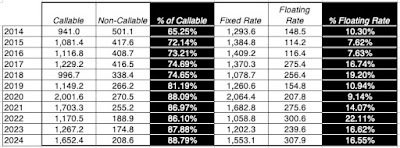

Debt Design There was a time when businesses did not have much choice, when it came to borrowing, and had to take whatever limited choices that banks offered. In the United States, corporate bond markets opened up choices for US companies, and in the last three decades, the rest of the world has started to get access to domestic bond markets. Since corporate bonds lend themselves better than bank loans to customization, it should come as no surprise now that many companies in the world have literally dozens of choices, in terms of maturity, coupon (fixed or floating), equity kickers (conversion options) and variants on what index the coupon payment is tied to. While these choices can be overwhelming for some companies, who then trust bankers to tell them what to do, the truth is that the first principles of debt design are simple. The best debt for a business is one that matches the assets it is being used to fund, with long term assets funded with long term debt, euro assets financed with euro debt, and with coupon payments tied to variables that also affect cash flows.

There is data on debt design, though not all companies are as forthcoming about how their debt is structured. In the table below, I look at broad breakdowns – conventional and lease debt, long term and short debt, by sector and sub-region again:

The US leads the world in the use of lease debt and in corporate bonds, with higher percentages of total debt coming from those sources. However, floating rate debt is more widely used in emerging markets, where lenders, having been burned by high and volatile inflation, are more likely to tie lending rates to current conditions. While making assessments of debt mismatch requires more company-level analysis, I would not be surprised if inertia (sticking with the same type of debt that you have always uses) and outsourcing (where companies let bankers pick) has left many companies with debt that does not match their assets. These companies then have to go to derivatives markets and hedge that mismatch with futures and options, creating more costs for themselves, but fees and benefits again for those who sell these hedging products.

The US leads the world in the use of lease debt and in corporate bonds, with higher percentages of total debt coming from those sources. However, floating rate debt is more widely used in emerging markets, where lenders, having been burned by high and volatile inflation, are more likely to tie lending rates to current conditions. While making assessments of debt mismatch requires more company-level analysis, I would not be surprised if inertia (sticking with the same type of debt that you have always uses) and outsourcing (where companies let bankers pick) has left many companies with debt that does not match their assets. These companies then have to go to derivatives markets and hedge that mismatch with futures and options, creating more costs for themselves, but fees and benefits again for those who sell these hedging products.Bottom Line When interest rates in the United States and Europe rose strongly in 2022, from decade-long lows, there were two big questions about debt that loomed. The first was whether companies would pull back from borrowing, with the higher rates, leading to a drop in aggregate debt. The other was whether there would be a surge in default rates, as companies struggled to generate enough income to cover their higher interest expenses. While it is still early, the data in 2023 and 2024 provide tentative answers to these questions, with the findings that there has not been a noticeable decrease in debt levels, at least in the aggregate, and that while the number of defaults has increased, default rates remain below the highs that you see during recessions and crises. The key test for companies will remain the economy, and the question of whether firms have over borrowed will be a global economic slowdown or recession.

YouTube Video

Data Updates for 2025Data Update 1 for 2025: The Draw (and Danger) of Data!Data Update 2 for 2025: The Party continued for US EquitiesData Update 3 for 2025: The times they are a'changin'!Data Update 4 for 2025: Interest Rates, Inflation and Central Banks!Data Update 5 for 2025: It's a small world, after all!Data Update 6 for 2025: From Macro to Micro - The Hurdle Rate Question!Data Update 7 for 2025: The End Game in Business!Data Update 8 for 2025: Debt, Taxes and Default - An Unholy Trifecta!Data LinksDebt fundamentals, by industry (US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India & China)Debt details, by industry (US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India & China)

February 18, 2025

Return on Equity, Earnings Yield and Market Efficiency: Back to Basics!

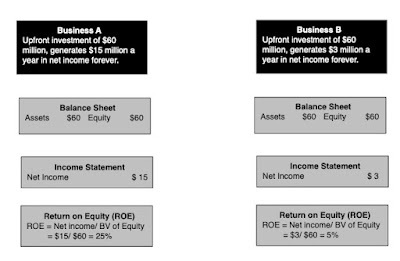

The Lead In: Business Formation To keep this example as stripped of complexity as I can, at least to begin, I will start with two entrepreneurs who invest $60 million apiece to start new businesses, albeit with very different economics:The first entrepreneur starts business A, with a $60 million investment up front, and that business is expected to generate $15 million in net income every year in perpetuity.The second entrepreneur starts business B, again with a $60 million investment up front, and that investment is expected to generate $3 million every year in perpetuity.With these characteristics, the accounting balance sheets for these companies will be identical right after they start up, and the book value of equity will be $60 million in each company.

The return on equity is an entirely accounting concept, and it can be computed by dividing the net income of each of the two businesses by the book value of equity:Return on equity for Business A = Net income for Business A / Book Value of Equity for Business A = 15/60 = 25%Return on equity for Business B = Net income for Business B / Book Value of Equity for Business B = 3/60 = 5%Assume that both these businesses have the same underlying business risk that translates into a cost of equity of 10%, giving the two businesses the following excess returns:Excess Return for Business A = Return on equity for Business A – Cost of equity for Business A = 25% -10% = 15%Excess Return for Business B = Return on equity for Business B – Cost of equity for Business B = 5% -10% = -5%In the language of my last post, the first business is a good one, because it creates value by earning more than your money would have earned elsewhere on an investment of equivalent risk, and the second is a bad one, because it does not. The return on equity may be an equation that comes from accounting statements, but in keeping with my argument that every number needs a narrative, each of these numbers has a narrative, often left implicit, that should be made explicit.On business A, the story has to be one of strong barriers to entry that allow it to sustain its excess returns in perpetuity, and those could include anything from a superlative brand name to patent protection to exclusive access to a natural resource. In the absence of these competitive advantages, these excess returns would have faded very quickly over time.On business B, you have a challenge, since it does seem irrational that an entrepreneur would enter a bad business, and while that irrationality cannot be ruled out (perhaps the entrepreneur thinks that earning any profit makes for a good business), the reality is that outside events can wreak havoc on the bet paid plans of businesses. For instance, it is possible that the entrepreneur’s initial expectations were that he or she would earn much more than 5%, but a competitor launching a much better product or a regulatory change could have changed those expectations.In sum, the return on equity and its more expansive variant, the return on invested capital, measure what a company is making on the capital it has invested in business, and is a measure of business quality.

The Market Launch Assume now that the owners of both businesses (A and B) list their businesses in the market, disclosing what they expect to generate as net income in perpetuity. Investors in equity markets will now get a chance to price the two companies, and if markets are efficient, they will arrive at the following:

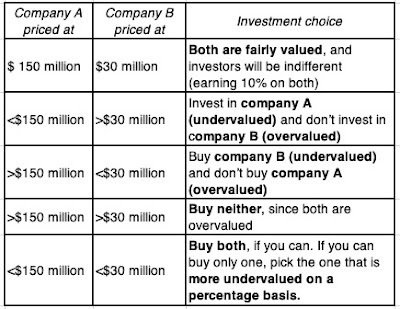

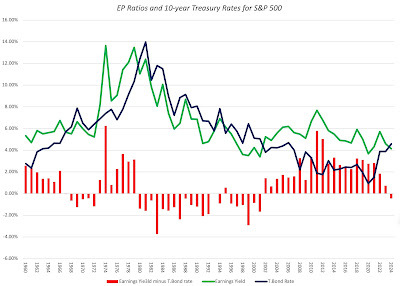

Thus, a discerning (efficient) market would value business A, with $15 million in net income in perpetuity at $150 million, while valuing business B, with $3 million in net income in perpetuity, at $30 million. If you are wondering why you would discount net income, rather than cash flow, the unique features of these investments (constant net income, no growth and forever lives) makes net income equal to cash flow. Even with this very simplistic example, there are useful implications. The first is that if markets are efficient, the price to book ratios will reflect the quality of these companies. In this example, for instance, business A, with a market value of equity of $150 million and a book value of equity of $60 million, will trade at 2.50 times book value, whereas company B with a market value of equity of $30 million and a book value of equity of $60 million will trade at half of book value. Both companies would be fairly valued, though the first trades at well above book value and the second at well below, thus explaining why a lazy variant of value investing, built almost entirely on buying stocks that trade at low price to book ratio,, will lead you to holding bad businesses, not undervalued ones. As I noted at the start of this post, it was motivated by trying to clear up a fundamental misunderstanding of what return on equity measures. In fact, the working definition that some commenters used for return on equity was obtained by dividing the net income by the market value of equity. That is not return on equity, but an earnings to price ratio, i.e., the earnings yield, and in these examples, with no growth and perpetual (constant) net income, that earnings yield will be equal to the cost of equity in an efficient market.

Thus, a discerning (efficient) market would value business A, with $15 million in net income in perpetuity at $150 million, while valuing business B, with $3 million in net income in perpetuity, at $30 million. If you are wondering why you would discount net income, rather than cash flow, the unique features of these investments (constant net income, no growth and forever lives) makes net income equal to cash flow. Even with this very simplistic example, there are useful implications. The first is that if markets are efficient, the price to book ratios will reflect the quality of these companies. In this example, for instance, business A, with a market value of equity of $150 million and a book value of equity of $60 million, will trade at 2.50 times book value, whereas company B with a market value of equity of $30 million and a book value of equity of $60 million will trade at half of book value. Both companies would be fairly valued, though the first trades at well above book value and the second at well below, thus explaining why a lazy variant of value investing, built almost entirely on buying stocks that trade at low price to book ratio,, will lead you to holding bad businesses, not undervalued ones. As I noted at the start of this post, it was motivated by trying to clear up a fundamental misunderstanding of what return on equity measures. In fact, the working definition that some commenters used for return on equity was obtained by dividing the net income by the market value of equity. That is not return on equity, but an earnings to price ratio, i.e., the earnings yield, and in these examples, with no growth and perpetual (constant) net income, that earnings yield will be equal to the cost of equity in an efficient market.Extending the Discussion One of the advantages of this very simple illustration is that it now can be used as a launching pad for casting light on some of the most interesting questions in investing:Good companies versus Good Investments: I have written about the contrast between a good company and a good investment, and this example provides an easy way to illustrate the difference. Looking at companies A and B, there is absolutely no debating the fact that company A is better company, with sustainable moats and high returns on equity (25%), than company B, which struggles to make money (return on equity of 5%), and clearly is in a bad business. However, which of these two companies is the better investment rests entirely on how the market prices them:

As you can see, the good company (A) can be a good, bad or neutral investment, depending on whether its is priced at less than, greater than or equal to its fair value ($150 million) and the same can be said about the bad company (B), with the price relative to its fair value ($30 million). At fair value, both become neutral investments, generating returns to shareholders that match their cost of equity.The Weakest Link in Excess Returns: The excess return is computed as the difference between return on equity and the cost of equity, and while it is true that different risk and return models and differences in risk parameters (relative risk measures and equity risk premiums) can cause variations in cost of equity calculations, the return on equity is the weaker link in this comparison. To understand some of the ways the return on equity can be skewed, consider the following variants on the simple example in this case:Accounting inconsistencies: As an entirely accounting number, the return on equity is exposed to accounting inconsistencies and miscategorization. To illustrate with our simple example, assume that half the money invested in business A is in R&D, which accountants expense, instead of capitalizing. That business will report a loss of $15 million (with the R&D expense of $30 million more than wiping out the profit of $15 million) in the first year on book capital of $30 million (the portion of the capital invested that is not R&D), but in the years following, it will report a return on capital of 50.00% (since net income will revert back to $15 million, and equity will stay at $30 million). Carrying this through to the real world, you should not be surprised to see technology and pharmaceutical companies, the two biggest spenders on R&D, report much higher accounting returns than they are actually earning on their investments..Aging assets: In our example, we looked at firms an instant after the upfront investment was made, when the book value of investment measures what was paid for the assets acquired. As assets age, two tensions appear that can throw off book value, the first being inflation, which if not adjusted for, will result in the book value being understated, and accounting returns overstated. The other is accounting depreciation, which often has little to do with economic depreciation (value lost from aging), and subject to gaming. Extrapolating, projects and companies with older assets will tend to have overstated accounting returns, as inflation and depreciation lay waste to book values. In fact, with an aging company, and adding in stock buybacks, the book value of equity can become negative (and is negative for about 10% of the companies in my company data sample).Fair Value Accounting: For the last few decades, the notion of fair value accounting has been a fever dream for accounting rule writers, and those rules, albeit in patchwork form, have found their way into corporate balance sheets. In my view, fair value accounting is pointless, and I can use my simple example to illustrate why. If you marked the assets of both company A and company B to market, you would end with book values of $150 million and $30 million for the two companies and returns on equity of 10% for both firms. In short, if fair value accounting does what it is supposed to do, every firm in the market will earn a return on equity (capital) equal to the cost of equity (capital), rendering it useless as a metric for separating good and bad businesses. If fair value accounting fails at what it is supposed to do, which is the more likely scenario, you will end up with book values of equity that measure neither original capital invested nor current market value, and returns on equity and capital that become noise.Growth enters the equation: For companies A and B, in this example, we assumed that the net income was constant, i.e., there is no growth. Introducing growth into the equation changes none of the conclusions that we have drawn so far, but it makes reading both the return on equity and the earnings yield much messier. To see why, assume that company A in the example continues to have no growth, but company B expects to see compounded annual growth of 50% a year in its net income of $3 million for the next decade. We can no longer consign company B to the bad business pile as easily, and the current earnings to price ratio for that company will no longer be equal to the cost of equity, even if markets are efficient. Incorporating growth into the analysis will also mean that net income is not equal to cash flow, since some or a large portion of that net income will have to get reinvested back to deliver the growth. In fact, this is the argument that I used in my second data update to explain why comparing the earnings yield to the treasury bond rate is unlikely to yield a complete assessment of whether stocks are under or over valued, since it ignores growth and reinvestment entirely.Exiting bad businesses: This example also helps to bring home why it is so difficult for companies in bad businesses to fix their "badness" or exit their businesses. In the case of company B, for instance, telling the manager to find projects that earn more than 10% is advice that can be freely dished out, but how exactly do you invent good projects in a business that has turned bad? While exiting the business seems to be a better choice, that presupposes that you will get your capital ($60 million) back when you do, but in the real world, potential buyers will discount that value. In fact, if you divest or sell the bad business for less than $30 million, you are actually worse off than staying in the business and continuing to generate $3 million a year in perpetuity, which has a $30 million value. In the real world, most companies in bad businesses hire new CEOs, restructure their businesses and enter new businesses in a desperate attempt to become good businesses, and enrich consultants and bankers, but not their own shareholders, along the way. Conclusion Many of the comments on my seventh data update, and on my explanation about why ROE and cost of equity don’t have to be equal in an efficient market, came from people with degrees and certifications in finance, and quite a few of the commenters had “finance professional” listed in their profile. Rather than take issue with them, I would argue that this misunderstanding of basics is a damning indictment of how these concepts and topics are taught in the classroom, and since I may very well be one of the culprits, one reason that I wrote this post is to remind myself that I have to revisit the basics, before making ambitious leaps into corporate financial analysis and valuation. For those of you who are not finance professionals, but rely on them for advice, I hope this is a cautionary note on taking these professionals (consultants, appraisers, bankers) at their word. Some of them throw buzzwords and metrics around, with little understanding of what they mean and how they are related, and it is caveat emptor.

YouTube Video

February 12, 2025

Data Update 7 for 2025: The End Game in Business!

I am in the third week of the corporate finance class that I teach at NYU Stern, and my students have been lulled into a false sense of complacency about what's coming, since I have not used a single metric or number in my class yet. In fact, we have spent almost four sessions (that is 15% of the overall class) talking about the end game in business. In an age when ESG, sustainability and stakeholder wealth maximization have all tried to elbow their way to the front of the line, all laying claim to being what business should be about, I have burnished my "moral troglodyte" standing by sticking with my belief that the end game in business is to maximize value, with earnings and cash flows driving that value, and that businesses that are profitable and value creating are in a much better position to do good, if they choose to try. In this post, I will focus on how companies around the world, and in different sectors, performed on their end game of delivering profits, by first focusing on profitability differences across businesses, then converting profitability into returns, and comparing these returns to the hurdle rates that I talked about in my last data update post.

Profitability - Absolute and Relative

While we may all agree with the proverbial bottom line being profits, there seems to be no consensus on how best to measure profitability, either from an accounting or an economic perspective. In this section, I will begin with a simplistic breakdown of the income statement, the financial statement that is supposed to tell us how much a business generated in profits in during a period, and use it as an (imperfect) tool to understand the business economics.

While accountants remain focused on balance sheets, with a fixation of bringing intangibles on to the balance and marking everything up to the market, much of the information that we need to assess the value of a business comes from income and cash flow statements. I am not an accountant, but I do rely on accounting statements for the raw data that I use in corporate finance and valuation. I have tried my hand at financial statement analysis, as practiced by accountants, and discovered that for the most part, the analysis creates more confusions than clarity, as a multiplicity of ratios pull you in different directions. It is for that reason that I created my own version of an accounting class, that you can find on my webpage.

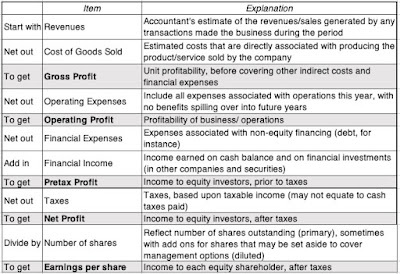

During the course of the class, I assess the income statement, in its most general form, by looking at the multiple measures of earnings at different phases of the statement:

Which of these represents the bottom line for businesses? If you are a shareholder in a company, i.e., an equity investor, the measure that best reflects the profits the company made on the equity you invested in them is the earnings per share. That said, there is information in the measures of earnings as you climb the income statement, and there are reasons why as you move up the income statement, the growth rates you observe may be different:To get from net income to earnings per share, you bring in share count, and actions taken by companies that alter that share count will have effects. Thus, a company that issues new shares to fund its growth may see net income growth, but its earnings per share growth will lag, as the share count increases. Conversely, a company that buys back shares will see share count drop, and earnings per share growth will outpace net income growth.To get from operating income to net income, you have multiple variables to control for. The first is taxes, and incorporating its effect will generally lead to lower net income, and the tax rate that you pay to get from pretax profit to net income is the effective tax rate. To the extent that you have cash on your balance, you will generate interest income which adds on to net income, but interest expenses on debt will reduce income, with the net effect being positive for companies with large cash balance, relative to the debt that they owe, and negative for firms with large net debt outstanding. There is also the twist of small (minority) holdings in other companies and the income you generate from those holdings that affect net income.To get from gross income to operating income, you have to bring in operating expenses that are not directly tied to sales. Thus, if you have substantial general and administrative costs or incur large selling and advertising costs or if you spend money on R&D (which accountants mistakenly still treat as operating expenses), your operating income will be lower than your gross income.Finally, to get from revenues to gross income, you net out the expenses incurred on producing the goods/services that you sell, with these expenses often bundled into a "cost of goods sold" categorization. While depreciation of capital investments made is usually separated out from costs of goods sold, and shown as an operating cost, there are some companies, where it is bundled into costs of goods sold. In many cases, the only statement where you will see depreciation and amortization as a line item is the statement of cash flows.

With that template in place, the place to start the assessment of corporate profitability is to to look at how much companies generated in each of the different earnings metrics around the world in 2024, broken down by sector:

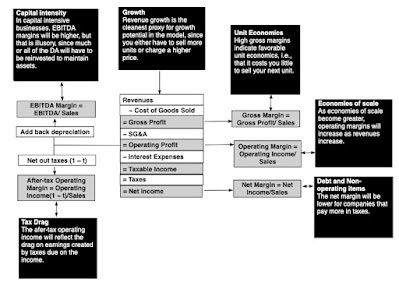

For the financial services sector, note that I have left revenues, gross profit, EBITDA and operating profit as not applicable, because of their unique structure, where debt is raw material and revenue is tough to nail down. (Conventional banks often start their income statements with net interest income, which is interest expense on their debt/deposits netted out against net income, making it closer to nough to categorize and compare to non-financial firms). I have also computed the percentage of firms globally that reported positive profits, a minimalist test on profitability in 2024, and there are interesting findings (albeit some not surprising) in this table:On a net profit basis, there is no contest for the sector that delivers the most net income. It is financials by a wide margin, accounting for a third of the net profits generated by all firms globally in 2024. In fact, technology, which is the sector with the highest market cap in 2024, is third on the list, with industrials taking second place.As you move from down the income statement, the percentage of firms that report negative earnings decreases. Across the globe, close to 84% of firms had positive gross profits, but that drops to 67% with EBITDA, 62% percent with operating income and 61% with net income. Across sectors, health care has the highest percentage of money-losing companies, on every single metric, followed by materials and communication services, whereas utilities had the highest percentage of money makers.While looking at dollar profits yields intriguing results, comparing them across sectors or regions is difficult to do, because they are in absolute terms, and the scale of businesses vary widely. The simple fix for that is to measure profitability relative to revenues, yielding profit margins - gross margins for gross profits, operating margins with operating profits and net margins with net profits. At the risk of stating these margins, not only are these margins not interchangeable, but they each convey information that is useful in understanding the economics of a business:

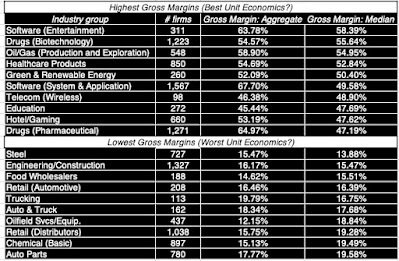

As you can see, each of the margins provides insight (noisy, but still useful) about different aspects of a business model. With gross margins, you are getting a measure of unit economics, i.e., the cost of producing the next unit of sale. Thus, for a software company, this cost is low or even zero, but for a manufacturing company, no matter how efficient, the cost will be higher. Even within businesses that look similar, subtle differences in business models can translate into different unit economics. For Netflix, adding a subscriber entails very little in additional cost, but for Spotify, a company that pays for the music based on what customers listen to, by the stream, the additional subscriber will come with additional cost. Just to get a big picture perspective on unit economics, I ranked industries based upon gross margin and arrived at the following list of the ten industries with the highest gross margins and the ten with the lowest:

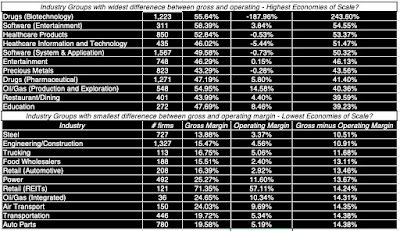

With the caveat that accounting choices can affect these margins, you can see that the rankings do make intuitive sense. The list of industry groups that have the highest margins are disproportionately in technology, though infrastructure firms (oil and gas, green energy, telecom) also make the list since their investment is up front and not per added product sold. The list of industry group with the lowest margins are heavily tilted towards manufacturing and retail, the former because of the costs of making their products and the latter because of their intermediary status. With operating margins, you are getting a handle on economies of scale. While every companies claims economies of scale as a rationale for why margins should increase as they get larger, the truth is more nuanced. Economies of scale will be a contributor to improving margins only if a company has significant operating expenses (SG&A, Marketing) that grow at a rate lower than revenues. To measure the potential for economies of scale, I looked at the difference between gross and operating margins, across industries, with the rationale that companies with a large difference have a greater potential for economies of scale.

With the caveat that accounting choices can affect these margins, you can see that the rankings do make intuitive sense. The list of industry groups that have the highest margins are disproportionately in technology, though infrastructure firms (oil and gas, green energy, telecom) also make the list since their investment is up front and not per added product sold. The list of industry group with the lowest margins are heavily tilted towards manufacturing and retail, the former because of the costs of making their products and the latter because of their intermediary status. With operating margins, you are getting a handle on economies of scale. While every companies claims economies of scale as a rationale for why margins should increase as they get larger, the truth is more nuanced. Economies of scale will be a contributor to improving margins only if a company has significant operating expenses (SG&A, Marketing) that grow at a rate lower than revenues. To measure the potential for economies of scale, I looked at the difference between gross and operating margins, across industries, with the rationale that companies with a large difference have a greater potential for economies of scale.

Many of the industry groups in the lowest difference (between gross and operating margin) list were also on the low gross margin list, and the implication is not upbeat. When valuing or analyzing these firms, not only should you expect low margins, but those margins will not magically improve, just because a firm becomes bigger. The EBITDA margin is an intermediate stop, and it serves two purposes. If provides a ranking based upon operating cash flow, rather than operating earnings, and for businesses that have significant depreciation, that difference can be substantial. It is also a rough measure of capital intensity since to generate large depreciation/amortization, these companies also had to have substantial cap ex. Using the difference between EBITDA and operating margin as a measure of capital intensity, the following table lists the industries with the most and least capital intensity:

Profit margins by industry: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India and China

Profit margins by industry: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India and ChinaAgain, there are few surprises on this list, including the presence of biotech at the top of the most capital intensive list, but that is due to the significant amortization line items on their balance sheets, perhaps from writing off failed R&D, and real estate on the top of the least capital intensive list, but the real estate segment in question is for real estate operations, not ownership. The net margin, in many ways, is the least informative of the profit margins, because there are so many wild cards at play, starting with differences in taxes (higher taxes lower net income), financial leverage (more leverage reduces net margins), cash holdings (interest from higher cash balances increases net income) and cross holdings (with varying effects depending on how they are accounted for, and whether they make or lose money). Ranking companies based upon net margin may measure everything from differences in financial leverage (more net debt should lead to lower margins) to extent of cross holdings and non-operating investments (more of these investments can lead to higher margins).

Accounting Returns

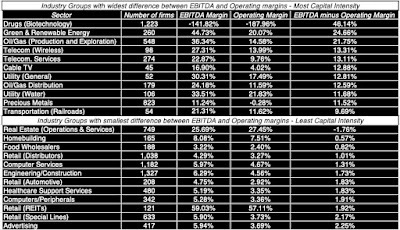

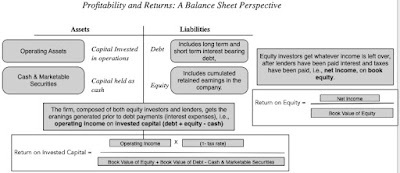

While scaling profits to revenues to get margins provides valuable information about business models and their efficacy, scaling profits to capital invested in a business is a useful tool for assessing the efficiency of capital allocation at the business., The two measures of profits from the previous section that are scaled to capital are operating income (before and after taxes) and net income, with the former measured against total invested capital (from equity and debt) and the latter against just equity capital. Using a financial balance sheet structure again, here is what we get:

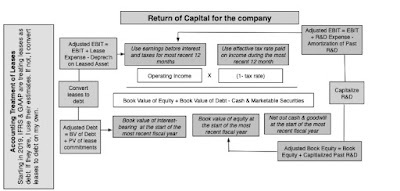

The achilles heel for accounting return measures is their almost total dependence on accounting numbers, with operating (net) income coming from income statements and invested capital (equity) from accounting balance sheets. Any systematic mistakes that accountants make (such as not treating leases as debt, which was the default until 2019, and treating R&D as an operating expense, which is still the case) will skew accounting returns. In addition, accounting decisions to write off an asset or take restructuring charges will make the calculation of invested capital more difficult. I wrote a long (and boring) paper on the mechanics of computing accounting returns laying out these and other challenges in computing accounting returns, and you are welcome to browse through it, if you want.

If you are willing to live with the limitations, the accounting returns become proxies for what a business earns on its equity (with return on equity) and as a business (with the cost of capital). Since the essence of creating value is that you need to earn more than your cost of capital, you can synthesize returns with the costs of equity and capital that I talked about in the last post, to get measures of excess returns:

I have the data to compute the accounting returns for the 48,000 publicly traded companies in my sample, though there are estimation choices that I had to make, when computing returns on equity and capital:

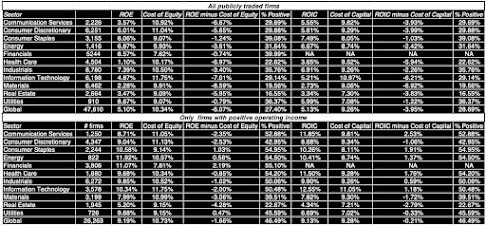

Thus, you will note that I have bypassed accounting rules and capitalized R&D and leases (even in countries where it is not required) to come up with my versions of earnings and invested capital. Having computed the return on capital (equity) for each company, I then compared that return to the cost of capital (equity) to get a measure of excess returns for the company. In the table below, I start by breaking companies down by sector, and looking at the statistics on excess returns, by sector:

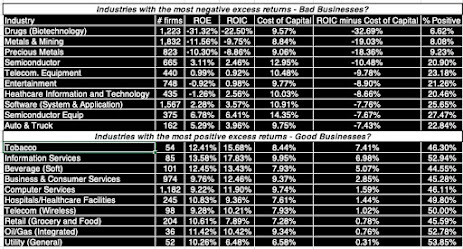

Note that across all firms, only about 30% of firms earn a return on capital that exceeds the cost of capital. Removing money-losing firms, which have negative returns on capital from the sample, improves the statistic a little, but even across money making firms, roughly half of all firms earn less the the cost of capital.While the proportions of firms that earn returns that exceed the cost of equity (capital) vary across sectors, there is no sector where an overwhelming majority of firms earn excess returns. I disaggregate the sectors into industry groups and rank them based upon excess returns in the table below, with the subtext being that industries that earn well above their cost of capital are value creators (good businesses) and those that earn below are value destroyers (bad businesses):

Excess returns by industry: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India and China

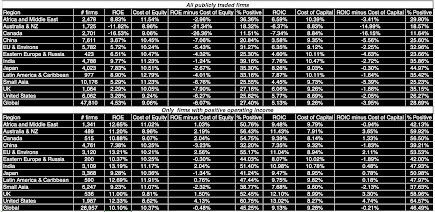

Excess returns by industry: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India and ChinaThere are some industry groups on this list that point to the weakness of using last year's earnings to get accounting return on capital. You will note that biotech drug companies post disastrously negative returns on capital but many of these firms are young firms, with some having little or no revenues, and their defense would be that the negative accounting returns reflect where they fall in the life cycle. Commodity companies cycle between the most negative and most returns lists, with earnings varying across the cycle; for these firms, using average return on capital over a longer period should provide more credible results. Finally, I look at excess returns earned by non-financial service companies by sub-region, again to see if companies in some parts of the world are better positioned to create value than others:

As you can see, there is no part of the world that is immune from this problem, and only 29% of all firms globally earn more than their cost of capital. Even if you eliminate firms with negative earnings, the proportion of firms that earn more than their cost of capital is only 46.5%.

Implications I have been doing versions of this table every year for the last decade, and the results you see in this year's table, i.e., that 70% of global companies generate returns on equity (capital) that are less tan their hurdle rates, has remained roughly static for that period. Making money is not enough for success: In many businesses, public or private, managers and even owners seem to think that making money (having a positive profit) represents success, not recognizing that the capital invested in these businesses could have been invested elsewhere to earn returns. Corporate governance is a necessity; Marty Lipton, a renowned corporate lawyer and critic of this things activist argued that activist investing was not necessary because most companies were well managed, and did not need prodding to make the right choices. The data in this post suggests otherwise, with most companies needing reminders from outside investors about the opportunity cost of capital.Companies are not fatted calves: In the last few years, two groups of people have targeted companies - politicians arguing that companies are price-gouging and the virtue crowd (ESG, sustainability and stakeholder wealth maximizers) pushing for companies to spend more on making the world a better place. Implicit in the arguments made by both groups is the assumption that companies are, at least collectively, are immensely profitable and that they can afford to share some of those spoils with other stakeholders (cutting prices for customers with the first group and spending lavishly on advancing social agendas with the second). That may be true for a subset of firms, but for most companies, making money has only become more difficult over the decades, and making enough money to cover the cost of the capital that they raise to create their businesses is an even harder reach. Asking these already stretched companies to spend more money to make the world a better place will only add to the likelihood that they will snap, under the pressures. A few months ago, I was asked to give testimony to a Canadian legislative committee that was planning to force Canadian banks to lend less to fossil fuel companies and more to green energy firms, a terrible idea that seems to have found traction in some circles. If you isolate the Canadian banks in the sample, they collectively generated returns on equity of 8.1%, with two thirds of banks earning less than their costs of equity. Pressuring these banks to lend less to their best customers (in terms of credit worthiness) and more to their worst customers (green energy company are, for the most part, financial basket cases) is a recipe for pushing these banks into distress, and most of the costs of that distress will be borne not by shareholders, but by bank depositors.

YouTube Video

Data Updates for 2025Data Update 1 for 2025: The Draw (and Danger) of Data!Data Update 2 for 2025: The Party continued for US EquitiesData Update 3 for 2025: The times they are a'changin'!Data Update 4 for 2025: Interest Rates, Inflation and Central Banks!Data Update 5 for 2025: It's a small world, after all!Data Update 6 for 2025: From Macro to Micro - The Hurdle Rate Question!Data Update 7 for 2025: The End Game in Business!Data LinksExcess returns by industry: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India and ChinaProfit margins by industry: US, Global, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, India and ChinaPaper LinksReturn on Capital (ROC), Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) and Return on Equity: Measurement and Implications

February 8, 2025

Data Update 6 for 2025: From Macro to Micro - The Hurdle Rate Question!

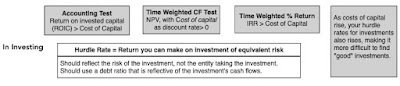

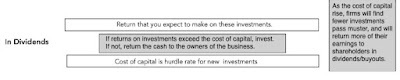

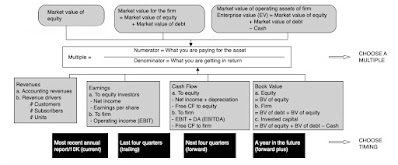

The Hurdle Rate - Intuition and Uses You don't need to complete a corporate finance or valuation class to encounter hurdle rates in practice, usually taking the form of costs of equity and capital, but taking a finance class both deepens the acquaintance and ruins it. It deepens the acquaintance because you encounter hurdle rates in almost every aspect of finance, and it ruins it, by making these hurdle rates all about equations and models. A few years ago, I wrote a paper for practitioners on the cost of capital, where I described the cost of capital as the Swiss Army knife of finance, because of its many uses. In my corporate finance class, where I look at the first principles of finance that govern how you run a business, the cost of capital shows up in every aspect of corporate financial analysis:In business investing (capital budgeting and acquisition) decisions, it becomes a hurdle rate for investing, where you use it to decide whether and what to invest in, based on what you can earn on an investment, relative to the hurdle rate. In this role, the cost of capital is an opportunity cost, measuring returns you can earn on investments on equivalent risk.

In business financing decisions, the cost of capital becomes an optimizing tool, where businesses look for a mix of debt and equity that reduces the cost of capital, and where matching up the debt (in terms of currency and maturity) to the assets reduces default risk and the cost of capital. In this context, the cost of capital become a measure of the cost of funding a business:

In dividend decisions, i.e., the decisions of how much cash to return to owners and in what form (dividends or buybacks), the cost of capital is a divining rod. If the investments that a business is looking at earn less than the cost of capital, it is a trigger for returning more cash, and whether it should be in the form of dividends or buybacks is largely a function of what shareholders in that company prefer:

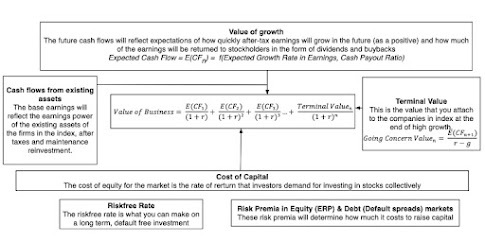

The end game in corporate finance is maximizing value, and in my valuation class, where I look at businesses from the outside (as a potential investor), the cost of capital reappears again as the risk-adjusted discount rate that you use estimate the intrinsic value of a business.

The end game in corporate finance is maximizing value, and in my valuation class, where I look at businesses from the outside (as a potential investor), the cost of capital reappears again as the risk-adjusted discount rate that you use estimate the intrinsic value of a business.

Much of the confusion in applying cost of capital comes from not recognizing that it morphs, depending on where it is being used. An investor looking at a company, looking at valuing the company, may attach one cost of capital to value the company, but within a company, but within a company, it may start as a funding cost, as the company seeks capital to fund its business, but when looking at investment, it becomes an opportunity cost, reflecting the risk of the investment being considered.

The Hurdle Rate - Ingredients

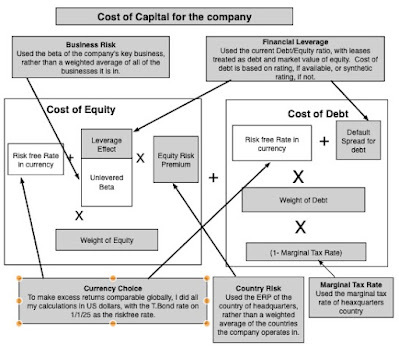

If the cost of capital is a driver of so much of what we do in corporate finance and valuation, it stands to reason that we should be clear about the ingredients that go into it. Using one of my favored structures for understanding financial decision making, a financial balance sheet, a cost of capital is composed of the cost of equity and the cost of debt, and I try to capture the essence of what we are trying to estimate with each one in the picture below:

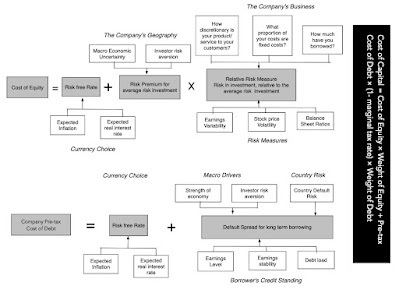

To go from abstractions about equity risk and default risk to actual costs, you have to break down the costs of equity and debt into parts, and I try to do so, in the picture below, with the factors that you underlie each piece:

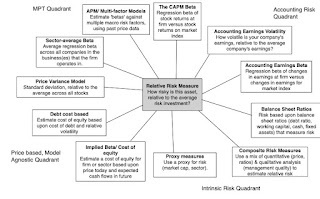

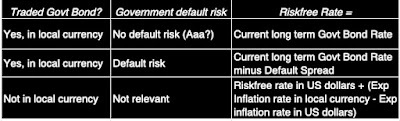

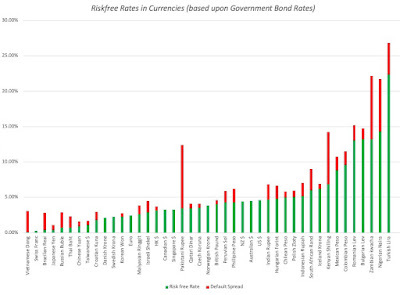

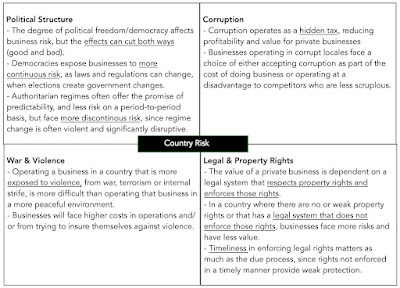

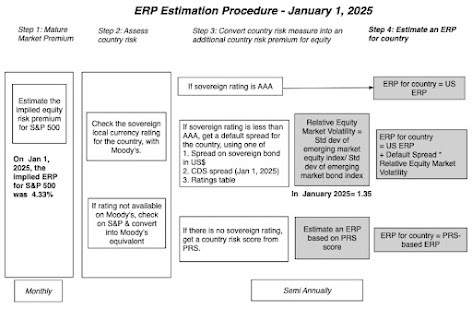

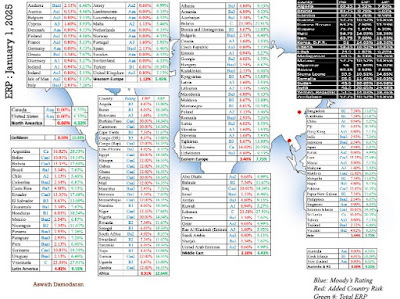

As you can see, most of the items in these calculations should be familiar, if you have read my first five data posts, since they are macro variables, having nothing to do with individual companies. The first is, of course, the riskfree rate, a number that varies across time (as you saw in post on US treasury rates in data update 4) and across currencies (in my post on currencies in data update 5). The second set of inputs are prices of risk, in both the equity and debt markets, with the former measured by equity risk premiums, and the latter by default spreads. In data update 2, I looked at equity risk premiums in the United States, and expanded that discussion to equity risk premiums in the rest of the world in data update 5). In data update 4, I looked at movements in corporate default spreads during 2024.There are three company-specific numbers that enter the calculation, all of which contribute to costs of capital varying across companies;Relative Equity Risk, i.e., a measure of how risky a company's equity is, relative to the average company's equity. While much of the discussion of this measure gets mired in the capital asset pricing model, and the supposed adequacies and inadequacies of beta, I think that too much is made of it, and that the model is adaptable enough to allow for other measures of relative risk.

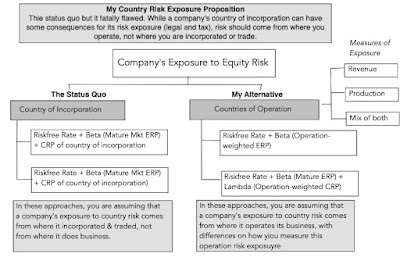

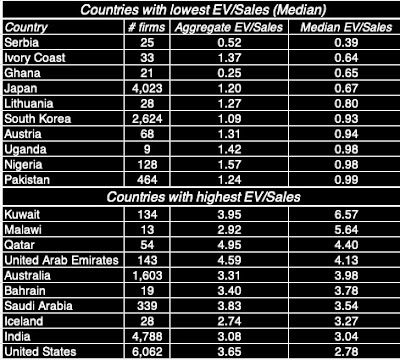

I am not a purist on this measure, and while I use betas in my computations, I am open to using alternate measures of relative equity risk.Corporate Default Risk, i.e, a measure of how much default risk there is in a company, with higher default risk translating into higher default spreads. For a fairly large subset of firms, a bond rating may stand in as this measure, but even in its absence, you have no choice but to estimate default risk. Adding to the estimation challenge is the fact that as a company borrows more money, it will play out in the default risk (increasing it), with consequences for both the cost of equity and debt (increasing both of those as well).Operating geographies: The equity risk premium for a company does not come from where it is incorporated but from where it does business, both in terms of the production of its products and services and where it generates revenue. That said, the status quo in valuation in much of the world seems to be to base the equity risk premium entirely on the country of incorporation, and I vehemently disagree with that practice:

I am not a purist on this measure, and while I use betas in my computations, I am open to using alternate measures of relative equity risk.Corporate Default Risk, i.e, a measure of how much default risk there is in a company, with higher default risk translating into higher default spreads. For a fairly large subset of firms, a bond rating may stand in as this measure, but even in its absence, you have no choice but to estimate default risk. Adding to the estimation challenge is the fact that as a company borrows more money, it will play out in the default risk (increasing it), with consequences for both the cost of equity and debt (increasing both of those as well).Operating geographies: The equity risk premium for a company does not come from where it is incorporated but from where it does business, both in terms of the production of its products and services and where it generates revenue. That said, the status quo in valuation in much of the world seems to be to base the equity risk premium entirely on the country of incorporation, and I vehemently disagree with that practice:

Again, I am flexible in how operating risk exposure is measured, basing it entirely on revenues for consumer product and business service companies, entirely on production for natural resource companies and a mix of revenues and production for manufacturing companies.As you can see, the elements that go into a cost of capital are dynamic and subjective, in the sense that there can be differences in how one goes about estimating them, but they cannot be figments of your imagination.

Again, I am flexible in how operating risk exposure is measured, basing it entirely on revenues for consumer product and business service companies, entirely on production for natural resource companies and a mix of revenues and production for manufacturing companies.As you can see, the elements that go into a cost of capital are dynamic and subjective, in the sense that there can be differences in how one goes about estimating them, but they cannot be figments of your imagination.The Hurdle Rate - Estimation in 2025 With that long lead in, I will lay out the estimation choices I used to estimate the costs of equity, debt and capital for the close to 48,000 firms in my sample. In making these choices, I operated under the obvious constraint of the raw data that I had on individual companies and the ease with which I could convert that data into cost of capital inputs.

Riskfree rate: To allow for comparisons and consolidation across companies that operate in different currencies, I chose to estimate the costs of capital for all companies in US dollars, with the US ten-year treasury rate on January 1, 2025, as the riskfree rate.Equity Risk Premium: Much as I would have liked to compute the equity risk premium for every company, based upon its geographic operating exposure, the raw data did not lend itself easily to the computation. Consequently, I have used the equity risk premium of the country in which a company is headquartered to compute the equity risk premium for it.Relative Equity Risk: I stay with beta, notwithstanding the criticism of its effectiveness for two reasons. First, I use industry average betas, adjusted for leverage, rather than the company regression beta, because because the averages (I title them bottom up betas) are significantly better at explaining differences in returns across stocks. Second, and given my choice of industry average betas, none of the other relative risk measures come close, in terms of predictive ability. For individual companies, I do use the beta of their primary business as the beta of the company, because the raw data that I have does not allow for a breakdown into businesses. Corporate default risk: For the subset of the sample of companies with bond ratings, I use the S&P bond rating for the company to estimate the cost of debt. For the remaining companies, I use interest coverage ratios as a first measure to estimate synthetic ratings, and standard deviation in stock prices as back-up measure.Debt mix: I used the market capitalization to measure the market value of equity, and stayed with total debt (including lease debt) to estimate debt to capital and debt to equity ratiosThe picture below summarizes my choices:

There are clearly approximations that I used in computing these global costs of capital that I would not use if I were computing a cost of capital for valuing an individual company, but this approach yields values that can yield valuable insights, especially when aggregated and averaged across groups.

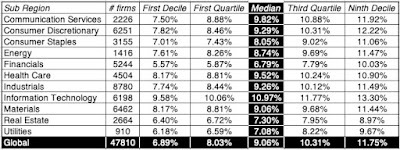

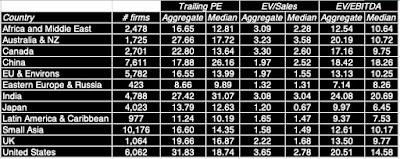

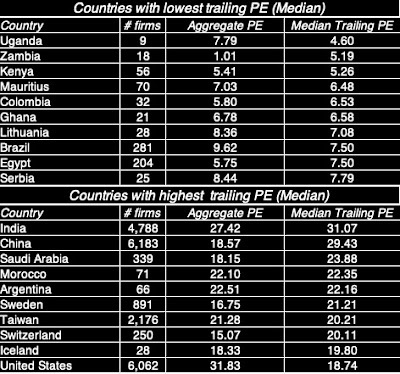

a. Sectors and Industries The risks of operating a business will vary widely across different sectors, and I will start by looking at the resulting differences in cost of capital, across sectors, for global companies:

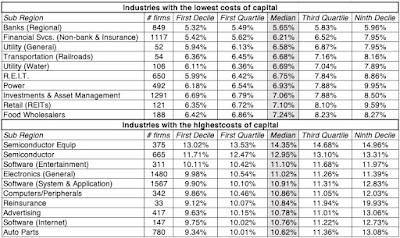

There are few surprises here, with technology companies facing the highest costs of capital and financials the lowest, with the former pushed up by high operating risk and a resulting reliance on equity for capital, and the latter holding on because of regulatory protection. Broken down into industries, and ranking industries from highest to lowest costs of capital, here is the list that emerges:

There are few surprises here, with technology companies facing the highest costs of capital and financials the lowest, with the former pushed up by high operating risk and a resulting reliance on equity for capital, and the latter holding on because of regulatory protection. Broken down into industries, and ranking industries from highest to lowest costs of capital, here is the list that emerges:

Download industry costs of capital

Download industry costs of capital

The numbers in these tables may be what you would expect to see, but there are a couple of powerful lessons in there that businesses ignore at their own peril. The first is that even a casual perusal of differences in costs of capital across industries indicates that they are highest in businesses with high growth potential and lowest in mature or declining businesses, bringing home again the linkage between danger and opportunity. The second is that multi-business companies should understand that the cost of capital will vary across businesses, and using one corporate cost of capital for all of them is a recipe for cross subsidization and value destruction.

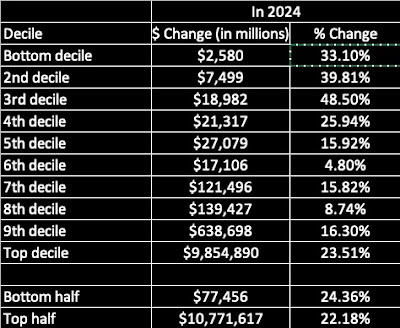

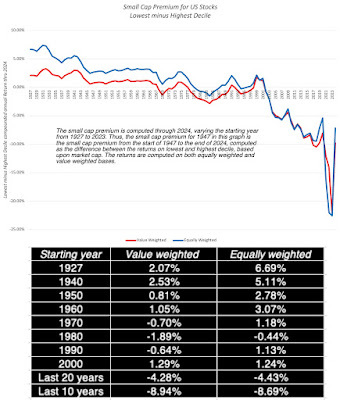

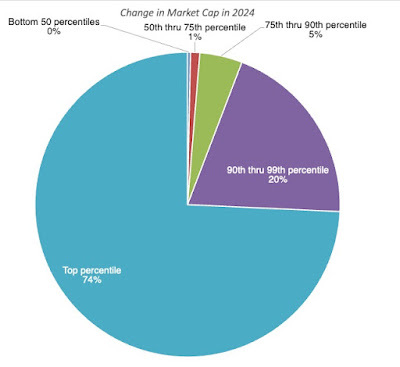

b. Small versus Larger firms In my third data update for this year, I took a brief look at the small cap premium, i.e, the premium that small cap stocks have historically earned over large cap stocks of equivalent risk, and commented on its disappearance over the last four decades. I heard from a few small cap investors, who argued that small cap stocks are riskier than large cap stocks, and should earn higher returns to compensate for that risk. Perhaps, but that has no bearing on whether there is a small cap premium, since the premium is a return earned over and above what you would expect to earn given risk, but I remained curious as to whether the conventional wisdom that small cap companies face higher hurdle rates is true. To answer this question, I examine the relationship between risk and market cap, breaking companies down into market cap deciles at the start of 2025, and estimating the cost of capital for companies within each decile:

The results are mixed. Looking at the median costs of capital, there is no detectable pattern in the cost of capital, and the companies in the bottom decile have a lower median cost of capital (8.88%) than the median company in the sample (9.06%). That said, the safest companies in largest market cap decile have lower costs of capital than the safest companies in the smaller market capitalizations. As a generalization, if small companies are at a disadvantage when they compete against larger companies, that disadvantage is more likely to manifest in difficulties growing and a higher operating cost structure, not in a higher hurdle rate.

c. Global Distribution In the final part of this analysis, I looked at the costs of capital of all publicly traded firms and played some Moneyball, looking at the distribution of costs of capital across all firms. In the graph below,I present the histogram of cost of capital, in US dollar terms, of all global companies at the start of 2025, with a breakdown of costs of capital, by region, below:

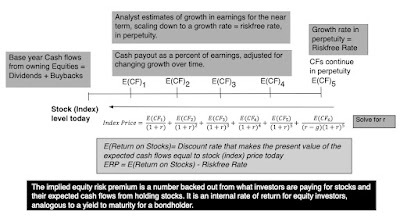

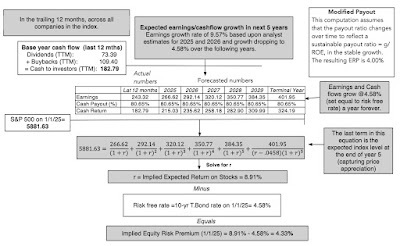

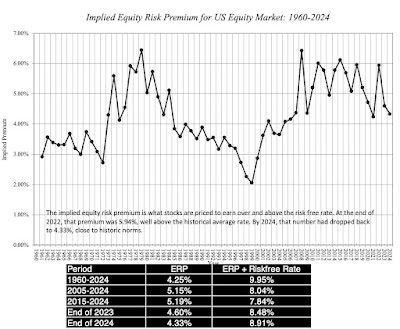

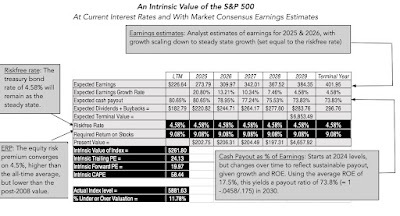

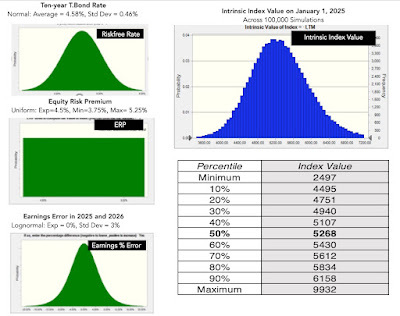

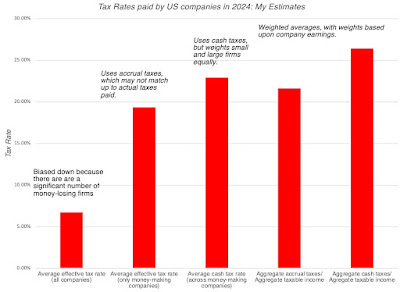

I find this table to be one of the most useful pieces of data that I possess and I use it in almost every aspect of corporate finance and valuation:Cost of capital calculation: The full cost of capital calculation is not complex, but it does require inputs about operating risk, leverage and default risk that can be hard to estimate or assess for young companies or companies with little history (operating and market). For those companies, I often use the distribution to estimate the cost of capital to use in valuing the company. Thus, when I valued Uber in June 2014, I used the cost of capital (12%) at the 90th percentile of US companies, in 2014, as Uber's cost of capital. Not only did that remove a time consuming task from my to-do list, but it also allowed me to focus on the much more important questions of revenue growth and margins for a young company. Drawing on my fifth data update, where I talk about differences across currencies, this table can be easily modified into the currency of your choice, by adding differential inflation. Thus, if you are valuing an Indian IPO, in rupees, and you believe it is risky, at the start of 2025, adding an extra 2% (for the inflation differential between rupees and dollars in 2025) to the ninth decile of Indian costs of capital (12.08% in US dollars) will give you a 14.08% Indian rupee cost of capital.Fantasy hurdle rates: In my experience, many investors and companies make up hurdle rates, the former to value companies and the latter to use in investment analysis. These hurdle rates are either hopeful thinking on the part of investors who want to make that return or reflect inertia, where they were set in stone decades ago and have never been revisited. In the context of checking to see whether a valuation passes the 3P test (Is it possible? Is it plausible? Is it probable?), I do check the cost of capital used in the valuation. A valuation in January 2025, in US dollars, that uses a 15% cost of capital for a publicly traded company that is mature is fantasy (since it is in well in excess of the 90th percentile), and the rest of the valuation becomes moot. Time-varying hurdle rates: When valuing companies, I believe in maintaining consistency, and one of the places I would expect it to show up is in hurdle rates that change over time, as the company's story changes. Thus, if you are valuing a money-losing and high growth company, you would expect its cost of capital to be high, at the start of the valuation, but as you build in expectations of lower growth and profitability in future years, I would expect the hurdle rate to decrease (from close to the ninth decile in the table above towards the median).It is worth emphasizing that since my riskfree rate is always the current rate, and my equity risk premiums are implied, i.e., they are backed out from how stocks are priced, my estimates of costs of capital represent market prices for risk, not theoretical models. Thus, if looking at the table, you decide that a number (median for your region, 90th percentile in US) look too low or too high, your issues are with the market, not with me (or my assumptions).