Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 5

November 1, 2023

Tesla in November 2023 : Story twists and turns, with value consequences!

I was planning to start this post by telling you that Tesla was back in the news, but that would be misleading, since Tesla never leaves the news. Some of that attention comes from the company's products and innovations, but much of it comes from having Elon Musk as a CEO, a man who makes himself the center of every news cycle. That attention has worked in the company's favor over much of its lifetime, as it has gone from a start-up to one of the largest market cap companies in the world, disrupting multiple businesses in the process. At regular intervals, though, the company steps on its own story line, creating confusion and distractions, and during these periods, its stock price is quick to give up gains, and that has been the case for the last few weeks. As the price dropped below $200 today (October 30,2023), I decided that it was time for me to revisit and revalue the company, taking into account the news, financial and other, that has come out since my last valuation in January 2023, and to understand the dueling stories that are emerging about the company.

My Tesla History

When I write and teach valuation, I describe it as a craft, and there are very few companies that I enjoy practicing that craft more than I do with Tesla. Along the way, I have been wrong often on the company, and if you are one of those who only reads valuations by people who get it right all the time, you should skip the rest of this post, because I will cheerfully admit that I will be wrong again, though I don't know in which direction. My first valuation of Tesla was in 2013, when it was a nascent automobile firm, selling less than 25,000 cars a year, and viewed by the rest of the automobile sector with a mix of disdain and curiosity. I valued it as a luxury automobile firm that would succeed in that mission, giving it Audi-level revenues in 2023 of about $65 billion, and operating margins of 12.50% that year (reflecting luxury auto margins). To deliver this growth, I did assume that Tesla would have to invest large amounts of capital in capacity, and that this would create a significant drag on value, resulting in a equity value of just under $10 billion.

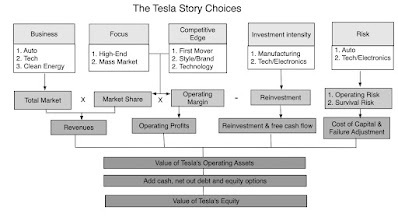

In subsequent valuations, I modified and adapted this story to reflect lessons that I learned about Tesla, along the way. First, I learned that the company was capable of generating growth much more efficiently, and more flexibly, than other auto companies, reducing the capital investment needed for growth. Second, I noticed that Tesla customers were almost fanatically attached to the company's products, and were willing to evangelize about it, yielding a brand loyalty that legacy auto companies could only dream about. Third, in a world where many companies are run by CEO who are, at best, operating automatons, and at worst, evidence of the Peter Principle at play, where incompetence rises to the top, Tesla had a CEO whose primary problem was too much vision, rather than too little. In valuation terms, that results in a company whose value shifts with narrative changes, creating not only wide swings in value, but vast divergences in opinion on value. In 2016, I looked at how Tesla's story would vary depending upon the narrative you had for the company and listed some of the possible choices in a picture:

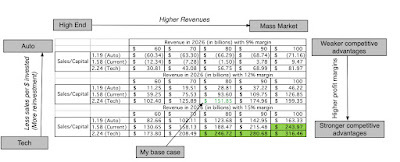

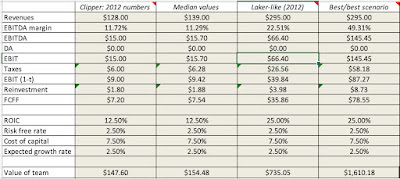

I translated these stories into inputs on revenue growth, profit margins and reinvestment, to arrive at a template of values:

I translated these stories into inputs on revenue growth, profit margins and reinvestment, to arrive at a template of values:

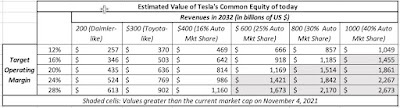

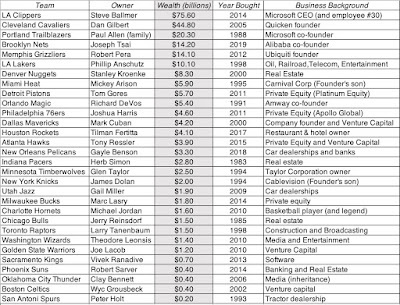

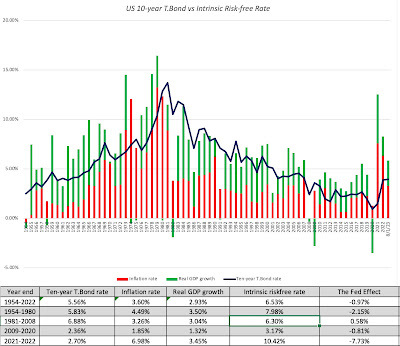

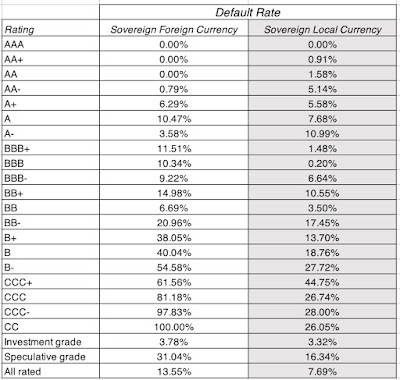

Note that is multiple stock splits ago, and the prices per share here are not comparable to the share price today, but the overall lessons contained in this table still apply. First, when you see significant disagreements about what Tesla is worth, those differences come from divergent stories, not disagreements about numbers. Second, every news story or financial disclosure about Tesla has to be used to evaluate how the company's narrative is changing, creating multiplier effects that create disproportionate value changes. Along the way, Tesla (or more precisely, Elon Musk) has made choices that could be, at best, described as puzzling, and, at worst, as perilous for the company's long term health, from borrowing money in 2017, when equity would have been a much better choice, to setting arbitrary targets on production (remember the 5000 cars a week for the company in 2018) and cash flows (positive cash flows in 2018) that pushed the company into a corner. If you add to that the self-inflicted wounds including Musk tweeting out that he had a deal to sell the company at $420 a share, funding secured, in 2018, it is not surprising that the stock has had periods of trauma. It was after one of these downturns in 2019, when the stock hit $180 (with a market cap of $32 billion), that I bought Tesla for the first time, albeit labeling it as my corporate teenager, an investment that would frustrate me because it would get in the way of its own potential. I profited mightily on that investment, but I sold too soon, when Tesla's market capitalization hit $150 billion, and just before COVID put the company on a new price orbit. In fact, I revisited the company's value in November 2021, when its market capitalization hit a trillion, marveling at its rise, but also noting that it was priced to deliver such wondrous results ($600-$800 billion in revenues, with 20%+ margins) that I was uncomfortable going along:

Note that is multiple stock splits ago, and the prices per share here are not comparable to the share price today, but the overall lessons contained in this table still apply. First, when you see significant disagreements about what Tesla is worth, those differences come from divergent stories, not disagreements about numbers. Second, every news story or financial disclosure about Tesla has to be used to evaluate how the company's narrative is changing, creating multiplier effects that create disproportionate value changes. Along the way, Tesla (or more precisely, Elon Musk) has made choices that could be, at best, described as puzzling, and, at worst, as perilous for the company's long term health, from borrowing money in 2017, when equity would have been a much better choice, to setting arbitrary targets on production (remember the 5000 cars a week for the company in 2018) and cash flows (positive cash flows in 2018) that pushed the company into a corner. If you add to that the self-inflicted wounds including Musk tweeting out that he had a deal to sell the company at $420 a share, funding secured, in 2018, it is not surprising that the stock has had periods of trauma. It was after one of these downturns in 2019, when the stock hit $180 (with a market cap of $32 billion), that I bought Tesla for the first time, albeit labeling it as my corporate teenager, an investment that would frustrate me because it would get in the way of its own potential. I profited mightily on that investment, but I sold too soon, when Tesla's market capitalization hit $150 billion, and just before COVID put the company on a new price orbit. In fact, I revisited the company's value in November 2021, when its market capitalization hit a trillion, marveling at its rise, but also noting that it was priced to deliver such wondrous results ($600-$800 billion in revenues, with 20%+ margins) that I was uncomfortable going along:

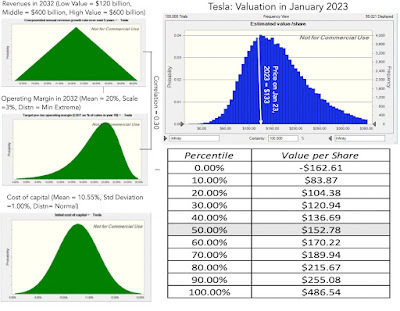

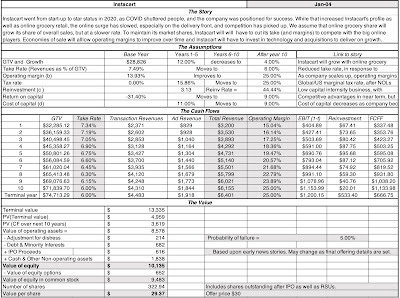

In 2022, the stock came back to earth with a vengeance, losing more than 65% of its equity value, leaving the stock (on a post-split basis) trading at close to $100 a share at the end of the year. Three weeks later, i.e., at the start of 2023, I revalued the stock, allowing for uncertainties in my estimate of revenues and margins to deliver a median value per share of $153, with significant variation in potential outcomes:

I was about a week late on my valuation, since the stock price had already broken through this value by the time I finished it, leaving my portfolio Tesla-free, in 2023.

I was about a week late on my valuation, since the stock price had already broken through this value by the time I finished it, leaving my portfolio Tesla-free, in 2023.Tesla Update

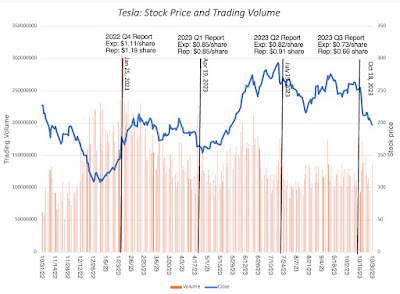

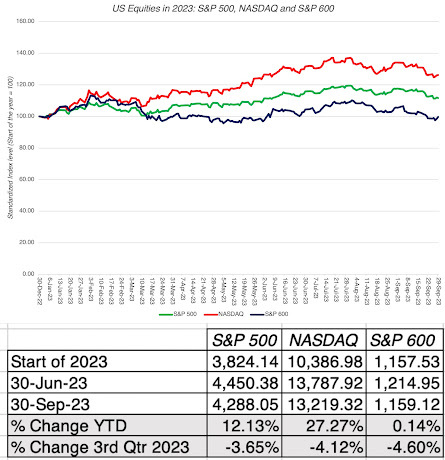

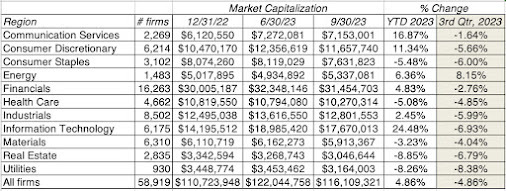

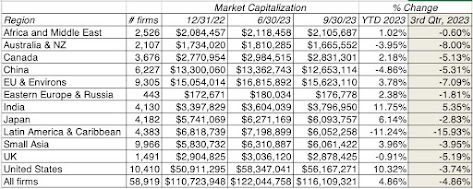

My last Tesla valuation is less than ten months old, and while that is not long in calendar time, with Tesla, it feels like an eternity, with this stock. As a lead in to updating the company’s valuation, it makes sense to start with the stock price, the market’s barometer for the company's health. The stock, which started the year in a swoon, recovered quickly in the first half of the year, peaking around mid-year at close to $300 a share.

The last four months have tested the stock, and it has given back a significant portion of its gains this year, with the stock dropping below $200 on October 30, 2023. Since earnings reports are often viewed as the catalysts for momentum shifts, I have highlighted the four earnings reports during the course of 2023, with a comparison of earnings per share reported, relative to expectations. The first earnings report, in January 2023, has been the only one where the company beat expectations, and it matched expectations in the April report, and fallen behind in the July and October reports.

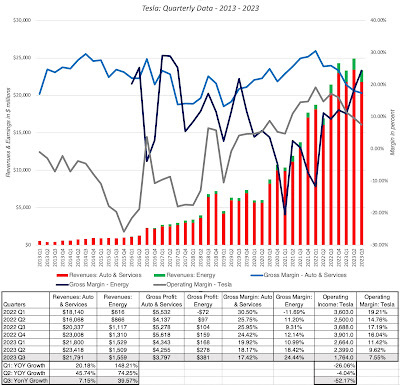

The earnings per share focus misses much of Tesla’s story, and it is instructive to dig deeper into the income statement and examine how the company has performed on broader operating metrics:

In the twelve months, ending September 2023, Tesla reported operating income of $10.7 billion on revenues of $95.9 billion; that puts their revenues well ahead of my 2013 projection of $65 billion, albeit with an operating margin of 11.18%, lagging my estimate of 12.5%. That makes Tesla the eleventh largest automobile company in the world, in revenue terms, and the seventh most profitable on the list, making it more and more difficult for naysayers to argue that it is a fad that will pass. Breaking down the news in the financials by business grouping, here is what the reports reveal:

Auto business: Tesla's auto business saw revenue growth slow down from the torrid pace that it posted between 2020 and 2022, with third quarter year-on-year revenue growth dropping to single digits, but given the flat sales in the auto sector and a sluggish electric car market, it remains a stand-out. The more disappointing number, at least for those who were expecting pathways to software-company like margins for the company, was the decline in profit margins on automobiles from 2022 levels, though the 17.42% gross margin in the third quarter, while disappointing for Tesla, would have been cause for celebration at almost any of its competitors.Energy business: Tesla's energy business, which was grounded by its acquisition of Solar City in 2016, has had a strong year, rising from 4.8% of the company's revenues in 2022 to 6.2% in the twelve months ending September 2023. In conjunction, the profitability of the business also surged in the last twelve months, and while some of this increase will average out, some of it can be attributed to a shift in emphasis to storage solutions (battery packs and other) from energy generation.In short, Tesla's financial reports, are an illustration of how much expectations can play a role in how markets react to the news in them. The post-COVID surge in Tesla's revenues and profitability led to unrealistically high expectations of what the company can do in this decade, and the numbers, especially in the last two quarters, have acted as a reality check. As a story stock, Tesla is affected as much by news stories about the company and its CEO, as it is by financials, and there are three big story lines about the company that bear on its value today:Price Cuts: During the course of 2023, Tesla has repeatedly cut prices on its offerings, with the most recent ones coming earlier this month, The $1,250 reduction in the Model 3 should see its price drop to about $39,000, making it competitive, even on a purely price basis, in the mass auto market in the United States. Some of this price cutting is tactical and in response to competition, current or forecast, but some of it may reflect a shift in the company's business model.Full Self Driving (FSD): Tesla, as a company, has pushed its work on full self driving to the forefront of its story, though there remains a divide in how far ahead Tesla is of its competition, and the long term prospects for automated driving. Its novelty and news value has made it a central theme of debate, with Tesla fans and critics using its successes and failures as grist for their social media postings. While an autopilot feature is packaged as a standard feature with Teslas, it offers FSD software, which is still in beta version, offers an enhanced autopilot model, albeit at a price of $12,000. The FSD news stories have also reignited talk of a robotaxi business for Tesla, with leaks from the company of a $25,000 vehicle specifically aimed at that business.Cybertruck: After years of waiting, the Tesla Cybertruck is here, and it too has garnered outsized attention, partly because of its unique design and partly because it is Tesla's entree into a market, where traditional auto companies still dominate. While there is still debate about whether this product will be a niche offering or one that changes the trucking market, it has undoubtedly drawn attention to the company. In fact, the company's reservation tracker records more than two millions reservations (with deposits), though if history is a guide, the actual sales will fall well short of these numbers.This being Tesla, there are dozens of other stories about the company, but that is par for the course. We will focus on these three stories because they have the potential to upend or alter the Tesla narrative, and by extension, its value.

Story and Valuation: Revisit and Revaluation

In my Tesla valuations through the start of 2023, I have valued Tesla as an automobile company, with the other businesses captured in top line numbers, rather than broken out individually. That does not mean that they are adding significantly to value, but that the value addition is buried in an input to value, rather than estimated standing alone. In my early 2023 valuation, I estimated an operating margin of 16% for Tesla, well above auto industry averages, because I believed that software and or the robotaxi businesses, in addition to delivering additional revenues, would augment operating margins, since they are high-margin businesses.

The news stories about Tesla this year have made me reassess that point of view, since they feed into the narrative that Tesla not only believes that the software and robotaxi businesses have significant value potential as stand-alone businesses, but it is acting accordingly. To see why, let me take each of the three news story lines and work them into my Tesla narrative:

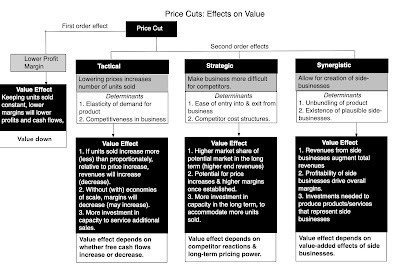

Cybertrucks: The easiest news items to weave into the Tesla narrative is the Cybertruck effect. If the advance orders are an indication of pent-up demand and the Cybertruck represents an extension into a hitherto untapped market, it does increase Tesla's revenue growth potential. There are two potential negatives to consider, and Musk referenced them during the course of the most recent earnings call. The first is that, even with clever design choices, at their rumored pricing, the margins on these trucks will be lower than on higher-end offerings. The other is that the Cybertruck may very well require dedicated production facilities, pushing up reinvestment needs. If Cybertruck sales are brisk, and the demand is strong, the positives will outweigh the negatives, but if the buzz fades, and it becomes a niche product, it may very well prove a distraction that reduces value. The value added by Cybertrucks will also depend, in part, on who buys them, with Tesla gaining more if the sales comes from truck buyers, coming from other companies, than it will if the sales comes from Tesla car buyers, which will cannibalize their own sales.FSD: As I look at the competing arguments about Tesla's FSD research, it seems clear to me that both sides have a point. On the plus side, Tesla is clearly further along this road than any other company, not only from a technological standpoint, but also from business model and marketing standpoints. While I do not believe that charging $12,000 for FSD as an add-on will create a big market, lowering that price will open the door not only to software sales to Tesla drivers, but perhaps even to other carmakers. In addition, it seems clear to me that the Tesla robotaxi business has now moved from possible to plausible on my scale, and thus merits being taken seriously. On the minus side, I do agree that the world is not quite ready for driverless cars, on scale, and that rushing the product to market can be catastrophic. Price cuts: The Tesla price cuts have led to a divide among Tesla bulls, with some pointing to it as the reason for Tesla's recent pricing travails and others viewing it as a masterstroke advancing it on its mission of global domination. To decide which side has the more realistic perspective, I decided to take a look at how price cuts play out in value for a generic company. The first order effect of a price cut is negative, since lowering prices will lower margins and profits, and it is easy to compute. It is the second order effects that are tricky, and I list the possibilities in the figure below, with value consequences:

In short, price cuts can, and often will, change the number of units sold, perhaps offsetting some of the downside to price cut (tactical), make it more difficult for competitors to keep up or enter your business (strategic) and expand the potential for side or supplemental businesses to thrive (synergistic). This figure explains the divide on the Tesla price cuts, with the pessimists arguing that electric car demand is too inelastic for volume increases that will compensate for the lower margins, and the optimists arguing that the value losses from lower margins will be more than offset by a long-term increase in Tesla's market share, and increase the value from their software and robotaxi businesses.

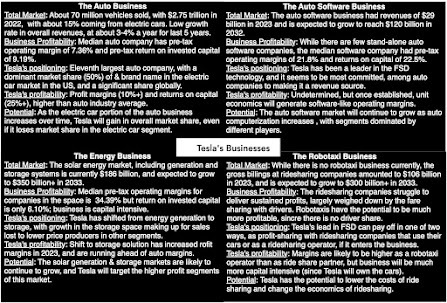

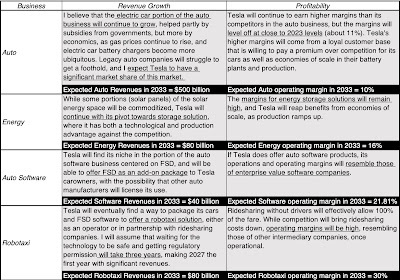

To bring these stories into play, I break Tesla down into four businesses - the auto business, the energy business, the software business and the robotaxi business. I do know that there will be Tesla optimists who will argue that there are other businesses that Tesla can enter, including insurance and robots, but for the moment, I think that the company has its hands full. I look out the landscape for these businesses in the picture below, looking at the potential size and profitability of the market for each of these businesses, as well as Tesla's standing in each.

Note that the auto business is, by far, the largest in terms of revenue potential, but it lags the other business in profitability, especially the software and robotaxi businesses, where unit economics are favorable and margins much higher. Note also that estimates for the future in the robotaxi and auto software businesses are squishy, insofar as they are till nascent, and there is much that we do not know.My Tesla story for each of these businesses is below, with revenue and profitability assumption, broken down by business:

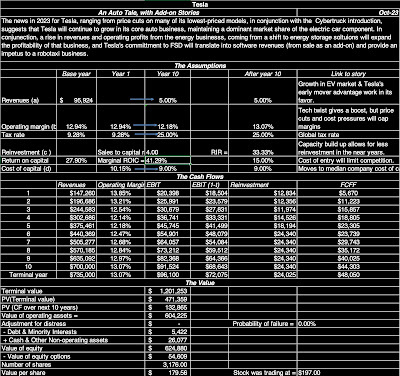

With these stories in place, I estimate revenues, earnings and cash flows for the businesses, and in sum, for the company, and use these cash flows to estimate a value per share for the company:

Download spreadsheet

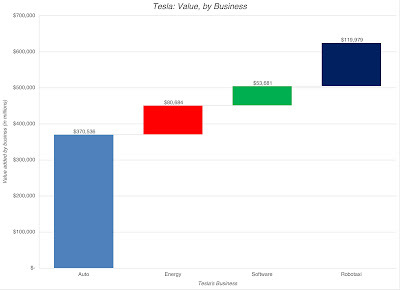

Download spreadsheetIn sum, the value per share that I get with Tesla's businesses broken down and allowing for divergent growth and profitability across businesses, is about $180 a share. That is higher than my estimate at the start of the year, with part of that increase coming from the higher profit potential in the side businesses, and expectations of a much larger end game in each one. Given that this value comes from four businesses, you can break down the value into each of those businesses, and I do so below:

Just as a note of caution, these businesses are all linked together, since the battery technology that drives the auto and energy businesses are shared, and FSD software sales will be tied to car sales. Consequently, you would not be able to spin off or sell these businesses, at least as these estimated values, but it does provide a sense of investors should watch for in this company. Thus, with a chunk of value tied to FSD, from software and robotaxis, any signs of progress (failure) on the FSD front will have consequences for value.

Just as a note of caution, these businesses are all linked together, since the battery technology that drives the auto and energy businesses are shared, and FSD software sales will be tied to car sales. Consequently, you would not be able to spin off or sell these businesses, at least as these estimated values, but it does provide a sense of investors should watch for in this company. Thus, with a chunk of value tied to FSD, from software and robotaxis, any signs of progress (failure) on the FSD front will have consequences for value.An Action Plan As you review my story and numbers, you will undoubtedly have very different views about Tesla going forward, and rather than tell me that you disagree with my views, which serves neither of us, please download the spreadsheet and make your own projections, by business. So, if you believe that I am massively underestimating the size of the robotaxi business, please do make your own judgment on how big it can get, with the caveat that making that business bigger will make your auto and software businesses smaller. After all, if everyone is taking robotaxis, the number of cars sold should drop off and existing car owners may be less likely to pay extra for a FSD package. At $197 a share, Tesla remains over valued, at least based on my story, but a stock that has dropped $54 in price in the last few weeks could very well drop another $20 in the next few. To capture that possibility, I have a limit buy at my estimated value of $180, with the acceptance that it may never hit that price in this iteration. For those of you who wonder why I don't have a margin of safety (MOS), I have argued that the MOS is a blunt instrument that is most useful when you are valuing mature companies where you face a luxury of riches (lots of under valued companies). Furthermore, as my January 2023 simulation of Tesla value reveals, this is a company with more upside than downside, and that make a fair-value investment one that I can live with. Put simply, the possibility of other businesses that Tesla can enter into adds optionality that I have not incorporated into my value, and that acts as icing on the cake. Obviously, and this will sound like the postscript from an email that you get from your investment banking friends, I am not offering this as investment advice. Unlike those investment banking email postscripts, I mean that from the heart and am not required by either regulators or lawyer to say it. I believe that investors have to take ownership of their investment decisions, and I would suggest that the only way for you to make your own judgment on Tesla is to frame your story, and value it based on that story. Of course, you are welcome to use, adapt or just ignore my spreadsheet in that process.

YouTube Video

Data and SpreadsheetsTesla 10Q (third quarter of 2023)My Tesla Valuation (October 30, 2023)

October 12, 2023

Good Intentions, Perverse Outcomes: The Impact of Impact Investing!

I have made no secret of my disdain for ESG, an over-hyped and over-sold acronym, that has been a gravy train for a whole host of players, including fund managers, consultants and academics. In response, I have been told that the problem is not with the idea of ESG, but in its measurement and application, and that impact investing is the solution to both market and society's problems. Impact investing, of course, is investing in businesses and assets based on the expectation of not just earning financial returns, but also creating positive change in society.

It is human nature to want to make the world a better place, but does impact investing have the impact that it aims to create? That is the question that I hope to address in this post. In the course of the post, I will work with two presumptions. The first is that the problems for society that impact investing are aiming to address are real, whether it be climate change, poverty or wealth inequality. The second is that impact investors have good intentions, aiming to make a positive difference in the world. I understand that there will be some who feel that these presumptions are conceding too much, but I want to keep my focus on the mechanics and consequences of impact investing, rather than indulge in debates about society's problems or question investor motives.

Impact Investing: The What, The Why and the How!

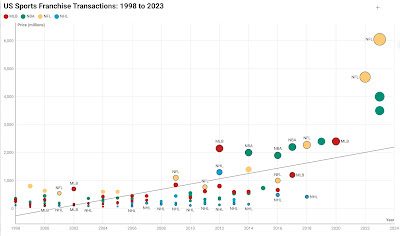

Impact investments are investments made with the intent of generating benefits for society, alongside a financial return. That generic definition is not only broad enough to cover a wide range of impact investing actions and motives, but has also been with us since the beginning of time. Investors and business people have often considered social payoffs when making investments, though they have differed on the social outcomes that they seek, and the degree to which they are willing to sacrifice the bottom line to achieve those outcomes. In the last two decades, this age-old investing behavior has come under the umbrella of impact investing, with several books on how to do it right, academic research on how it is working (or not), and organizations dedicated to advancing its mission. The Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), a non-profit that tracks the growth of this investing movement, estimated that more than $1.16 trillion was invested by impact investors in 2021, with a diverse range of investors: Global Impact Investing Network, 2022 Report

Global Impact Investing Network, 2022 ReportNot surprisingly, the balance between social impact and financial return desired by investors, varies across investor groups, with some more focused on the former and others the latter. In a survey of impact investors, GIIN elicited these responses on what types of returns investors expected to earn on their impact investments, broken down by groups:

Global Impact Investing Network, 2020 Report

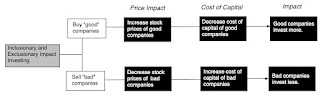

Global Impact Investing Network, 2020 ReportAlmost two thirds of impact investors believe that they can eat their cake and have it too, expecting to earn as much or more than a risk-adjusted return, even as they do good. That delusion running deepest among pension funds, insurance companies, for-profit fund managers and diversified financial investors, who also happen to account for 78% of all impact investing funds. If having a positive impact on society, while earning financial returns, is what characterizes impact investing, it can take one of three forms:Inclusionary Impact Investing: On the inclusionary path, impact investors seek out businesses or companies that are most likely to have a positive impact on whatever societal problem they are seeking to solve, and invest in these companies, often willing to pay higher prices than justified by the financial payoffs on the business. Exclusionary Impact Investing: In the exclusionary segue, impact investors sell shares in businesses that they own, or refuse to buy shares in these businesses, if they are viewed as worsening the targeted societal problem.Evangelist Impact Investing: In the activist variant, impact investors buy stakes in businesses that they view as contributing to the societal problem, and then use that ownership stake to push for changes in operations and behavior, to reduce the negative social or environmental impact.The effect of impact investing in the inclusionary and exclusionary paths is through the stock price, with the buying (selling) in inclusionary (exclusionary) investing pushing stock prices up (down), which, in turn, decreases (increases) the costs of equity and capital at these firms. The changes in costs of funding then show up in investing decisions and growth choices at these companies, with good companies expanding and bad companies shrinking.

With evangelist impact investing, impact investors aim to get a critical mass of shareholders as allies in pushing for changes in how companies operate, shifting the company away from actions that create bad consequences for society to those that have neutral or good consequences.

With evangelist impact investing, impact investors aim to get a critical mass of shareholders as allies in pushing for changes in how companies operate, shifting the company away from actions that create bad consequences for society to those that have neutral or good consequences.

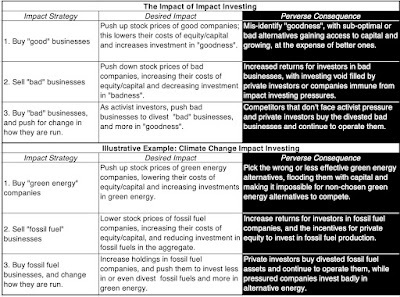

As you can see, for impact investing to have an impact on society, a series of links have to work, and if any or all of them fail, there is the very real potential that impact investing can have perverse consequences.With inclusionary investing, there is the danger that you mis-identify the companies capable of doing good, and flood these companies with too much capital. Not only is capital invested in these companies wasted, but increases the barriers to better alternatives to doing good. With exclusionary investing, pushing prices down below their "fair" values will allow investors who don’t care about impact to earn higher returns, from owning these companies. More importantly, if it works at reducing investment from public companies in a "bad" business, it will open the door to private investors to fill the business void. With evangelist investing, an absence of allies among other shareholders will mean that your attempts to change the course of businesses will be largely unsuccessful. Even when you are successful in dissuading these companies from "bad" investments, but may not be able to stop them from returning the cash to shareholders as dividends and buybacks, rather than making "good" investments.In the table below, I look at the potential for perverse outcomes under each of three impact investing approaches, using climate change impact investing as my illustrative example:

The question of whether impact investing has beneficial or perverse effects is an empirical question, not a theoretical one, since your assumptions about market depth, investor behavior and business responses can lead you to different conclusion. It is worth noting that impact investing may have no effect on stock prices or on corporate behavior, either because there is too little money behind it, or because there is offsetting investing in the other direction. In those cases, impact investing is less about impacting society and more about alleviating the guilt and cleansing the consciences of the impact investors, and the only real impact will be on the returns that they earn on their portfolios.

The Impact of Impact Investing: Climate Change

While impact investing can be directed at any of society's ills, it is undeniable that its biggest focus in recent years has been on climate change, with hundreds of billions of dollars directed at reversing its effects. Climate change, in many ways, is also tailored to impact investing, since concerns about climate change are widely held and many of the businesses that are viewed as good or bad, from a climate change perspective, are publicly traded. As an empirical question, it is worth examining how impact investing has affected the market perceptions and pricing of green energy and fossil fuel companies, the operating decisions at these companies, and most critically, on the how we produce and consume energy.

Fund Flows

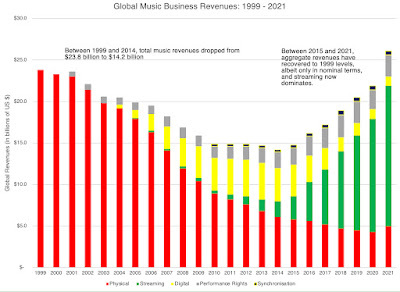

The biggest successes of climate change impact investing have been on the funding side. Not only has impact investing directed large amounts of capital towards green and alternative energy investments, but the movement has also succeeded in convincing many fund managers and endowments to divest themselves of their investments in fossil fuel companies.

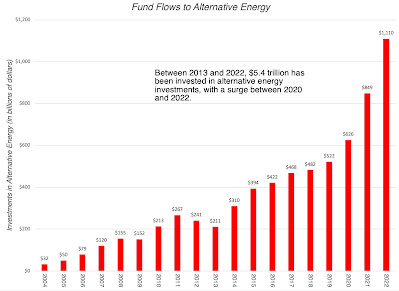

As concerns about climate change have risen, the money invested in alternative energy companies has expanded, with $5.4 trillion cumulatively invested in the last decade: Source: BloombergNEF

Source: BloombergNEFOn the divestment side, the drumbeat against fossil fuel investing has had an effect, with many investment fund managers and endowments joining the divestiture movement:Almost half of this investment in alternative energy sources has been in renewable energy, with electrified transport and electrified heat accounting for a large portion of the remaining investments.

By 2023, close to 1600 institutions, with more than $40 trillion of funds under their management, had announced or concluded their divestitures of investments in fossil fuel companies.

If impact investing were measured entirely on fund flows into green energy companies and out of fossil fuel companies, it has clearly succeeded.

Market Price (and Capitalization)

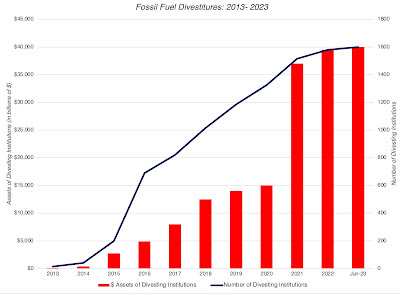

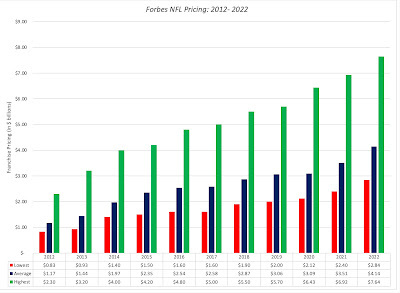

It is undeniable that fund flows into or out of companies affects their stock prices, and if the numbers in the last section are even close to reality, you should have expected to see a surge in market prices at alternative energy companies, as a result of funds flowing into them, and a decline in market prices of fossil fuel companies, as fossil fuel divestment gathers steam.

On the alternative energy front, as money has flowed into these companies, there has been a surge in enterprise value (equity and net debt) and market capitalization (equity value); I report both because impact investing can also take the form of green bonds, or debt, at these companies. The enterprise value of publicly traded alternative energy companies has risen from close to zero two decades ago to more than $700 billion in 2020, before losing steam in the last three years:

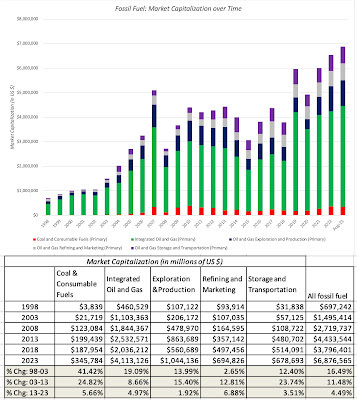

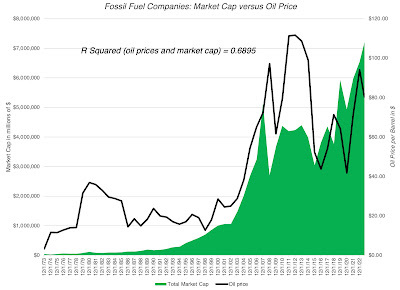

Adding in the value of private companies and start-ups in this space would undoubtedly push up the number further.On the fossil fuel front, the fossil fuel divestments have had an impact on market capitalizations, though there are signs that the effect is weakening:

In the last decade, when fossil fuel divestment surged, the percentage changes in market capitalization at fossil fuel companies lagged returns on the market, with fossil fuel companies reporting a compounded annual percentage increase of 4.49% a year.. The negative effect was strongest in the middle of the last decade, but market prices for fossil fuel companies have recovered strongly between 2020 and 2023.

It is worth noting that even after their surge in market cap in the last decade, alternative energy companies have a cumulated enterprise value of about $600 billion in September 2023, a fraction of the $8.5 trillion of cumulated enterprise value at fossil fuel companies.

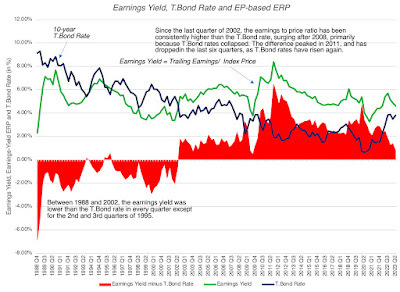

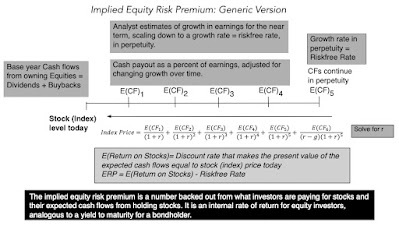

Investor perceptions

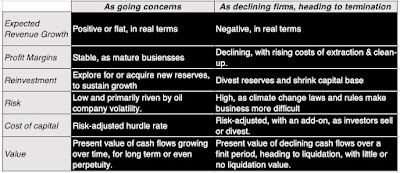

Impact investing has always been about changing investor perceptions of energy companies, more than just prices. In fact, some impact investors have argued that their presence in the market and advocacy for alternative energy has led investors to change their views about fossil fuel companies, shifting from viewing them as profitable, cash-rich businesses with extended lives, to companies living on borrowed time, looking at decline and even demise. In intrinsic valuation terms, that shift should show up in the pricing, with lower value attached to the latter scenario than the former:

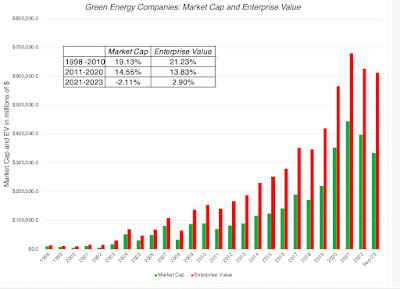

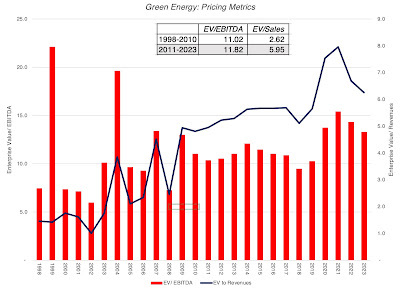

On the green energy front, to see if investors perceptions of these companies have changed, I look at two the pricing metrics for green energy companies - the enterprise value to EBITDA and enterprise value to revenue multiples:

The numbers offer a mixed message on whether impact investing has changed investor perceptions, with EV to EBITDA multiples staying unchanged, between the 1998-2010 and 2011-2023 time periods, but EV as a multiple of revenues soaring from 2.62 in the 1998-2010 time period to 5.95 in the 2011-2023 time period. The fund flows into green energy are affecting pricing, though it remains an open question as to whether the pricing is getting too rich, as too much money chases too few opportunities.

The numbers offer a mixed message on whether impact investing has changed investor perceptions, with EV to EBITDA multiples staying unchanged, between the 1998-2010 and 2011-2023 time periods, but EV as a multiple of revenues soaring from 2.62 in the 1998-2010 time period to 5.95 in the 2011-2023 time period. The fund flows into green energy are affecting pricing, though it remains an open question as to whether the pricing is getting too rich, as too much money chases too few opportunities.Looking at fossil fuel firms, the poor performance in the last decade seems to support the notion that impact investing has changed how investors perceive fossil fuel companies, but there are some checks that need to be run to come that conclusion.

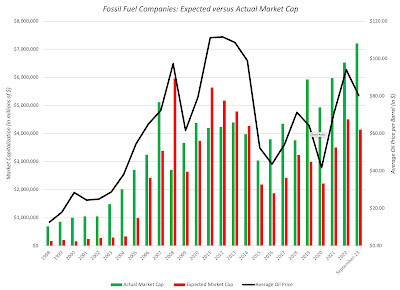

Oil Price Effect: The market capitalization of oil companies is dependent on oil prices, as you can see in the figure below, where the collective market capitalization of fossil fuel companies is graphed against the average oil price each year from 1970 to 2022; almost 70% of the variation in market capitalization over time explained by oil price movements.

To separate impact investing divestment effects from oil price effects, I estimated the predicted market capitalization of fossil fuel companies, given the oil price each year, using the statistical relationship between market cap and oil prices in the twenty five years leading into the forecast year. (I regress market capitalization against average oil price from 1973 to 1997 to estimate the expected market cap in 1998, given the oil price in 1998, and so on, for every year from 1998 to 2023. Note that the only thing you can read these regressions is that market capitalization and oil prices move together, and that there is no way to draw conclusions about causation):

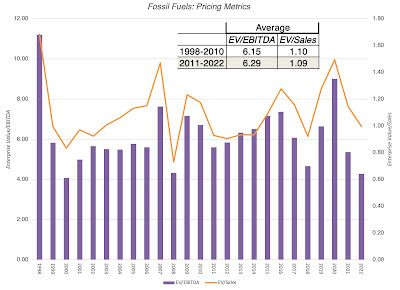

If divestitures are having a systematic effect on how markets are pricing fossil fuel companies, you should expect to see the actual market capitalizations trailing the expected market capitalization, based on the oil price. That seems to be the case, albeit marginally, between 2011 and 2014, but not since then. In short, the divestiture effect on fossil fuel companies has faded over time, with other investors stepping in and buying shares in their companies, drawn by their earnings power.Pricing: If impact investing is changing investor perceptions about the future growth and termination risk at fossil fuel companies, it should show up in how these companies are priced, lowering the multiples of revenues or earnings that investors are willing to pay. In the chart below, I look at the pricing of fossil fuel companies over time, using EV to sales and EV to EBITDA as pricing metrics:

While the pricing metrics swing from year to year, that has always been true at oil companies, since earnings and revenues vary, with oil prices. However, if impact investing is having a systematic effect on how investors are pricing companies, there is little evidence of that in this chart.In sum, while it is possible to find individual investors who have become skeptical about the future for fossil fuel companies, that view is not reflective of the market consensus. I do believe that investors are pricing fossil fuel companies now, with the expectation of much lower growth in the future, than they used to, but that is coming as much from these companies returning more of their earnings as cash and reinvesting less than they used to, as it is from an expectation that the days of fossil fuel are numbered. Some impact investors will argue that this is because investors are short-term, but that is a double-edged sword, since it undercuts the very idea of using investing as the vehicle to create social and environmental change.

Operating Impact

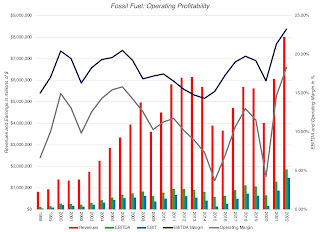

Impact investing, in addition to affecting pricing of green energy and fossil fuel companies, can also have effects on how fossil fuel companies perform and operate. On the profitability front, fossil fuel companies seem to have weathered the onslaught of climate change critics, with revenues and profit margins (EBITDA and operating) bouncing back from a slump between 2014 and 2018 to reach historic highs in 2022.

While the pricing metrics swing from year to year, that has always been true at oil companies, since earnings and revenues vary, with oil prices. However, if impact investing is having a systematic effect on how investors are pricing companies, there is little evidence of that in this chart.In sum, while it is possible to find individual investors who have become skeptical about the future for fossil fuel companies, that view is not reflective of the market consensus. I do believe that investors are pricing fossil fuel companies now, with the expectation of much lower growth in the future, than they used to, but that is coming as much from these companies returning more of their earnings as cash and reinvesting less than they used to, as it is from an expectation that the days of fossil fuel are numbered. Some impact investors will argue that this is because investors are short-term, but that is a double-edged sword, since it undercuts the very idea of using investing as the vehicle to create social and environmental change.

Operating Impact

Impact investing, in addition to affecting pricing of green energy and fossil fuel companies, can also have effects on how fossil fuel companies perform and operate. On the profitability front, fossil fuel companies seem to have weathered the onslaught of climate change critics, with revenues and profit margins (EBITDA and operating) bouncing back from a slump between 2014 and 2018 to reach historic highs in 2022.

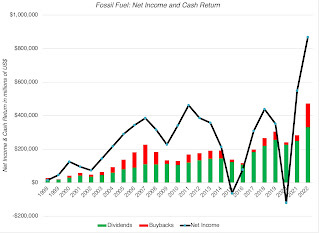

A key development over the last decade, as profits have returned, is that fossil fuel companies are returning much of cash flows that they are generating to their shareholders in the form of dividends and buybacks, notwithstanding the pressure from activist impact investors that they reinvest that money in green energy projects:

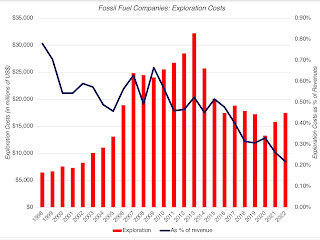

A key development over the last decade, as profits have returned, is that fossil fuel companies are returning much of cash flows that they are generating to their shareholders in the form of dividends and buybacks, notwithstanding the pressure from activist impact investors that they reinvest that money in green energy projects: In one development that impact investors may welcome, fossil fuel companies are collectively investing less in exploration for new fossil fuel reserves in the last decade than they did in prior ones:

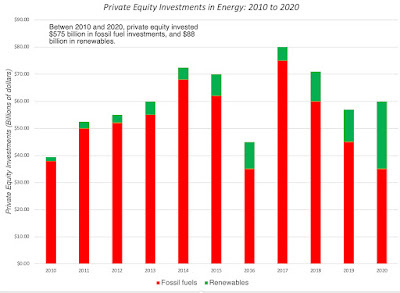

In one development that impact investors may welcome, fossil fuel companies are collectively investing less in exploration for new fossil fuel reserves in the last decade than they did in prior ones: If you couple this trend of exploring less with the divestitures of fossil fuel reserves, over the last decade, there is a basis for the argument that fossil fuel companies are reducing their fossil fuel presence, and some impact investing advocates may be tempted to declare victory. After all, if the objective is to reduce fossil fuel production, does it not advance your cause if less money is being spent exploring for coal, oil and gas? Before claiming a win, though, there is a dark side to this retreat by public fossil-fuel companies, and that comes from private equity investors and privately-owned (or government-owned) oil companies stepping into the breach; many of the divestitures and sales of fossil fuel assets by publicly traded companies have been to private buyers, and the assets being divested are often among the dirtiest (from a climate-change perspective) of their holdings.. Over the last decade, some of private equity’s biggest players have invested well over $1.1 trillion in fossil fuel, with the investments ranging the spectrum.

If you couple this trend of exploring less with the divestitures of fossil fuel reserves, over the last decade, there is a basis for the argument that fossil fuel companies are reducing their fossil fuel presence, and some impact investing advocates may be tempted to declare victory. After all, if the objective is to reduce fossil fuel production, does it not advance your cause if less money is being spent exploring for coal, oil and gas? Before claiming a win, though, there is a dark side to this retreat by public fossil-fuel companies, and that comes from private equity investors and privately-owned (or government-owned) oil companies stepping into the breach; many of the divestitures and sales of fossil fuel assets by publicly traded companies have been to private buyers, and the assets being divested are often among the dirtiest (from a climate-change perspective) of their holdings.. Over the last decade, some of private equity’s biggest players have invested well over $1.1 trillion in fossil fuel, with the investments ranging the spectrum.

Source: Pitchbook

Source: PitchbookWhile there was an uptick in investments in renewables in 2019 and 2020, the overwhelming majority of private equity investments during the decade were in fossil fuels. In the process, private equity firms like the Carlyle Group and KKR have become major holders of fossil fuel reserves, and there are a few private buyers who have profited from buying abandoned and castoff oil wells from oil companies, pressured to sell by impact investors. While climate change advocates are quick to point to this public-to-private transition of fossil fuel assets as a flaw, they fail to recognize that it is is a natural side-effect of an approach that paints publicly traded fossil fuel firms as villains and shuns their investments, while continuing to be dependent on fossil fuels for meeting energy needs. On the activist front, there is evidence that impact investing's capacity to change oil company behavior is losing its potency. While fossil fuel companies were quick to give in to pressure from impact investors to de-carbonize, for much of the last decade, the Russian invasion of Ukraine seems to have been an "emperor-has-no-clothes" moment for green energy advocates, laying bare how reliant the globe still is on fossil fuels for its energy needs. In the aftermath, the biggest fossil fuel companies have become bolder about their plans to stay in and grow their fossil fuel investments, with Royal Dutch taking a stake in Qatari gas field, BP announcing it will produce more oil and gas, Exxon Mobil buying Pioneer Natural Resources, a shale driller for $60 billion, and Petrobras reversing course on divestitures.

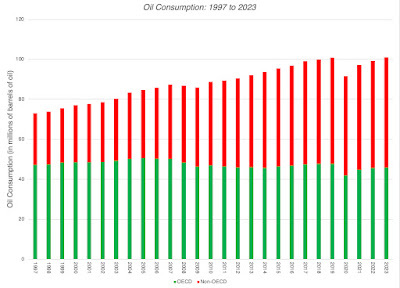

Macro Impact The success or failure of impact investing, when it relates to climate change, ultimately comes from the changes it creates in how energy is produce and consumed, and it is on this front that the futility of the movement is most visible. While alternative energy sources have expanded their production, it has not been at the expense of oil consumption, which has barely budged over the last decade.

EIA: World Oil Consumption

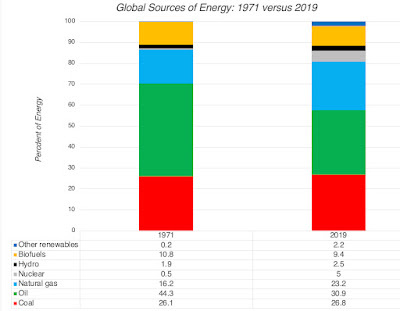

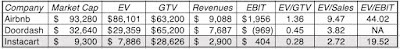

Fairly or unfairly, the pandemic seems to have done more to curb oil consumption than all of impact investing's efforts over the last decade, but the COVID effect, which saw oil consumption drop in 2020 has largely faded. Taking a global and big-picture perspective of where we get our energy, a comparison of energy sources in 1971 and 2019 yields a picture of how little things have changed:

EIA: World Oil Consumption

Fairly or unfairly, the pandemic seems to have done more to curb oil consumption than all of impact investing's efforts over the last decade, but the COVID effect, which saw oil consumption drop in 2020 has largely faded. Taking a global and big-picture perspective of where we get our energy, a comparison of energy sources in 1971 and 2019 yields a picture of how little things have changed:

IEA: World Energy Balances Overview

IEA: World Energy Balances Overview

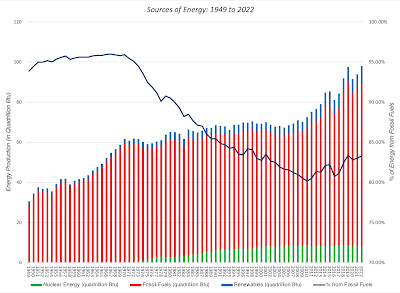

Fossil fuel, which accounted for 86.6% of energy production in 1971, was responsible for 80.9% of production in 2019, with almost all of that gain from coming from nuclear energy, which many impact investors viewed as an undesirable alternative energy source for much of the last decade. Focusing on energy production just in the US, the failure of impact investing to move the needle on energy production can be seen in stark terms:

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Fossil fuels account for a higher percent of overall energy produced in the United States today than they did ten or fifteen years ago, with gains in solar, wind and hydropower being largely offset by reductions in nuclear energy. If this is what passes for winning in impact investing, I would hate to see what losing looks like. I have tried out variants of this post with impact investing acquaintances, and there are three broad responses that they have to its findings (and three defenses for why we should keep trying):

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Fossil fuels account for a higher percent of overall energy produced in the United States today than they did ten or fifteen years ago, with gains in solar, wind and hydropower being largely offset by reductions in nuclear energy. If this is what passes for winning in impact investing, I would hate to see what losing looks like. I have tried out variants of this post with impact investing acquaintances, and there are three broad responses that they have to its findings (and three defenses for why we should keep trying):Things would be worse without impact investing: It is impossible to test this hypothetical, but is it possible that our dependence on fossil fuels would be even greater, without impact investing making a difference? Of course, but that argument would be easier to make, if the trend lines were towards fossil fuels before impact investing, and moved away from fossil fuels after its rise. The data, though, suggests that the biggest shift away from fossil fuels occurred decades ago, well before impact investing was around, primarily from the rise of nuclear energy, and that impact investing's tunnel vision on alternative energy has actually made things worse.It takes time to create change: It is true that the energy business is an infrastructure business, requiring large investments up front and long gestation periods. It is possible that the effects of impact investing are just not being felt yet, and that they are likely to show up later this decade. This would undercut the urgency argument that impact investors have used to induce their clients to invest large amounts and doing it now, and if they had been more open about the time lag from the beginning, this argument would have more credibility today.Investing cannot offset consumption choices: If the argument is that impact investing cannot stymie climate change on its own, without changes in consumer behavior, I could not agree more, but changing behavior will be painful, both politically and economically. I would argue that impact investing, by offering the false promise of change on the cheap, has actually reduced the pressure on politicians and rule-makers to make hard decisions on taxes and production.Even conceding some truth in all three arguments, what I see in the data is the essence of insanity, where impact investors keep throwing in more cash into green energy and more vitriol at fossil fuels, while the global dependence on fossil fuels increases.

Impact Investing: Investing for change Much of what I have said about impact investing's quest to fight climate change can be said about the other societal problems that impact investors try to address. Poverty, sexism, racism and inequality have had impact investing dollars directed at them, albeit not on the same scale as climate change, but are we better off as a society on any of these dimensions? To the response that doing something is better than being doing nothing, I beg to differ, since acting in ways that create perverse outcomes can be worse than sitting still. To end this post on a hopeful note, I believe that impact investing can be rescued, albeit in a humbler, more modest form. With your own money, pass the sleep test: If you are investing your own money, your investing should reflect your pocketbook as well as your conscience. After all, investors, when choosing what to invest in, and how much, have to pass the sleep test. If investing in Exxon Mobil or Altria leads you to lose sleep, because of guilt, you should avoid investing in these companies, no matter how good they look on a financial return basis.With other people's money, be transparent and accountable about impact: If you are investing other people’s money, and aiming for impact, you need to be explicit on what the problem is that you are trying to solve, and get buy in from those who are investing with you. In addition, you should specify measurement metrics that you will use to evaluate whether you are having the impact that you promised.Be honest about trade offs: When investing your own or other people's money, you have to be honest with yourself not only about the impact that you are having, but about the trade offs implicit in impact investing. As someone who teaches at NYU, I believe that NYU's recent decision to divest itself of fossil fuels will not only have no effect on climate change, but coming from an institution that has established a significant presence in Abu Dhabi, it is an act of rank hypocrisy. It is also critical that those impact investors who expect to make risk-adjusted market returns or more, while advancing social good, recognize that being good comes with a cost.Less absolutism, more pragmatism: For those impact investors who cloak themselves in virtue, and act as if they command the moral high ground, just stop! Not only do you alienate the rest of the world, with your I-care-about-the-world-more-than-you attitude, but you eliminate any chances of learning from your own mistakes, and changing course, when your actions don't work.Harness the profit motive: I know that for some impact investors, the profit motive is a dirty concept, and the root reason for the social problems that impact investing is trying to address. While it is true that the pursuit of profits may underlie the problem that you are trying to solve, the power from harnessing the profit motive to solve problems is immense. Agree with his methods or not, Elon Musk, driven less by social change and more by the desire to create the most valuable company in the world, has done more to address climate change than all of impact investing put together. I started this post with two presumptions, that the social problems being addressed by impact investors are real and that impact investors have good intentions, and if that is indeed the case, I think it is time that impact investors face the truth. After 15 years, and trillions invested in its name, impact investing, as practiced now, has made little progress on the social and environmental problems that it purports to solve. Is it not time to try something different?

YouTube Video

ESG PostsSounding Good or Doing Good: A Skeptical Look at ESGThe ESG Movement: The Goodness Gravy Train rolls on!ESG's Russia Test: Trial by Fire or Crash and Burn?

October 6, 2023

Invisible, yet Invaluable: Valuing Intangibles in the Birkenstock IPO!

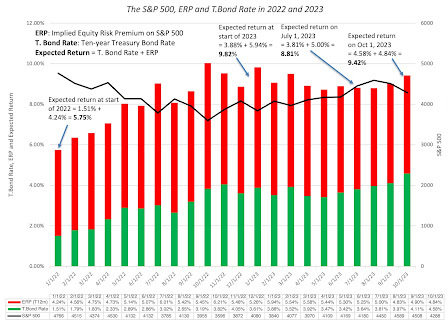

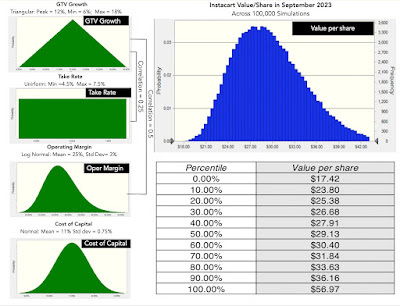

A few days ago, I valued Instacart ahead of its initial public offering, and noted that the reception that the stock gets will be a good barometer of where risk capital stands in the market, right now. After a buzzy open, when the stock jumped from its offering price of $30 a share to $42, the stock has quickly given up those gains and now trades at below to its offer price. In this post, I will look at another initial public offering, Birkenstock, that is likely to get more attention in the next few weeks, given that it is targeting to go public at a pricing of about €8 billion, for its equity, in a few weeks. Rather than make this post all about valuing Birkenstock, and comparing that value to the proposed pricing, I would like to use the company to discuss how intangible assets get valued in an intrinsic valuation, and why much of the discussion of intangible valuation in accounting circles is a reflection of a mind-set on valuation that often misses its essence.

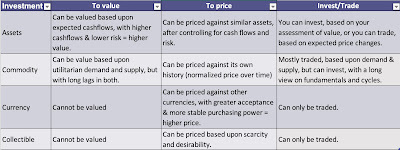

The Value of Intangible Assets

Accounting has historically done a poor job dealing with intangible assets, and as the economy has transitioned away from a manufacturing-dominated twentieth century to the technology and services focused economy of the twenty first century, that failure has become more apparent. The resulting debate among accountants about how to bring intangibles on to the books has spilled over into valuation practice, and many appraisers and analysts are wrongly, in my view, letting the accounting debate affect how they value companies.

The Rise of Intangibles

While the debate about intangibles, and how best to value them, is relatively recent, it is unquestionable that intangibles have been a part of valuation, and the investment process, through history. An analyst valuing General Motors in the 1920s was probably attaching a premium to the company, because it was headed by Alfred Sloan, viewed then a visionary leader, just as an investor pricing GE in the 1980s was arguing for a higher pricing, because Jack Welch was engineering a rebirth of the company. Even a cursory examination of the the Nifty Fifty, the stocks that drove US equities upwards in the early 1970s, reveals companies like Coca Cola and Gilette, where brand name was a significant contributor to value, as well as pharmaceutical companies like Bristol-Myers and Pfizer, which derived a large portion of their value from patents. In fact, IBM and Hewlett Packard, pioneers of the tech sector, were priced higher during that period, because of their technological strengths and other intangibles. Within the investment community, there has always been a clear recognition of the importance of intangibles in driving investment value. In fact, among old-time value investors, especially in the Warren Buffet camp, the importance of having "good management' and moats (competitive advantages, many of which are intangible) represented an acceptance of to how critical it is that we incorporate these intangible benefits into investment decisions.

With that said, it is clear that the debate about intangibles has become more intense in the last two decades. One reason is the perception that intangibles now represent a greater percent of value at companies and are a significant factor in more of the companies that we invest in, than in the past. While I have seen claims that intangibles now account for sixty, seventy or even ninety percent of value, I take these contentions with a grain of salt, since the definition of "intangible" is elastic, and some stretch it to breaking point, and the measures of value used are questionable. A more tangible way to see why intangibles have become a hot topic of discussion is to look at the evolution of the top ten companies in the world, in market capitalization, over time:

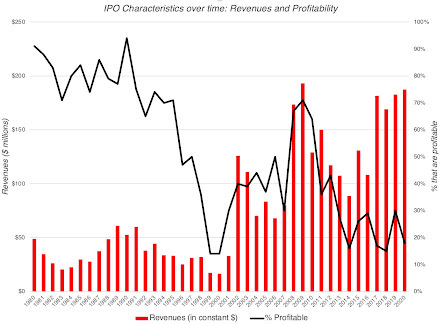

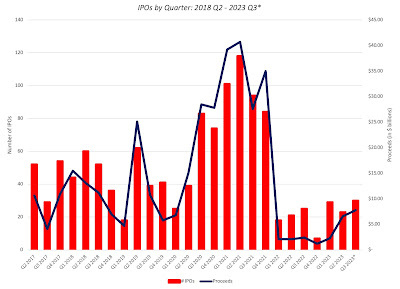

In 1980, IBM was the largest market cap company in the world, but eight of the top ten companies were oil or manufacturing companies. With each decade, you can see the effect of regional and sector performance in the previous decade; the 1990 list is dominated by Japanese stocks, reflecting the rise of Japanese equities in the 1980s, and the 2000 list by technology and communication companies, benefiting from the dot-com boom. Looking at the top ten companies in 2020 and 2023, you see the dominance of technology companies, many of which sell products that you cannot see, often in production facilities that are just as invisible. The other development that has pushed the intangible discussion to the forefront is a sea change in the characteristics of companies entering public markets. While companies that were listed for much of the twentieth century waited until they had established business models to go public, the dot-com boom saw the listing of young companies with growth potential but unformed business models (translating into operating losses), and that trend has continued and accelerated in this century. The graph below looks at the revenues and profitability of companies that go public each year, from 1980 to 2020:

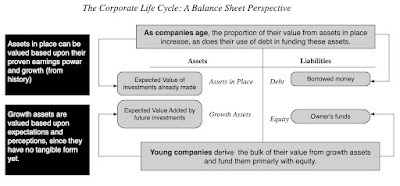

As you can see, the percent of money-making companies going public has dropped from more than 90% in the 1980s to less than 20% in 2020, but at the same time, while also reporting much higher revenues, reporting the push by private companies to scale up quickly. In valuing these companies, investors and analysts face a challenge, insofar as much of the values of these firms came from expectations of what they would do in the future, rather than investments that they have already made. I capture this effect in what I call a financial balance sheet:

While you can value assets-in-place, using historical data and the information in financial statements, in assessing the value of growth assets, you are making your best assessments of investments that these companies will make in the future, and these investments are formless, at least at the moment.

The Accounting Challenge with Intangibles

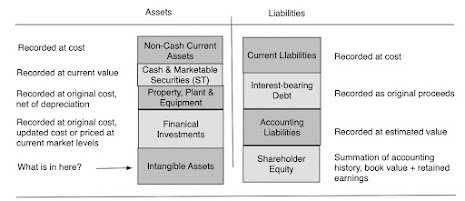

The intangible debate is most intense in the accounting community, with both practitioners and academics arguing about whether intangibles should be "valued", and if so, how to bring that value into financial statements. To see why the accounting consequences are likely to be dramatic, consider how these choices will play out in the balance sheet, the accountants' attempt to encapsulate what a business owns, what it owes and how much its equity is worth.

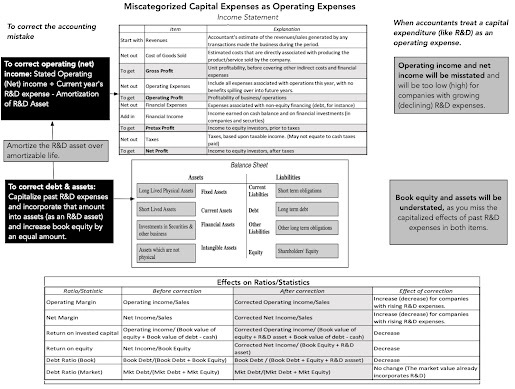

There are inconsistencies in how accountants measure different classes of assets, and I incorporate them into my picture above, leaving the intangible assets section as the unknown: Any changes in accounting rules on measuring the value of intangibles, and bringing them on the balance sheet, will also play out as changes on the other side of the balance sheet, primarily as changes in the value of assessed or book equity. Put simply, if accountants decide to bring intangible assets like brand name, management quality and patent protection into asset value will increase the value of book equity, at least as accountants measure it, in that company. In their attempt to bring intangible assets on to balance sheets, accountants face a barrier of their own creation, emanating from how they treat the expenditures incurred in building up these assets. To understand why, consider how fixed assets (such as plant and equipment and equipment) become part of the balance sheet. The expenditures associated with acquiring these fixed assets are treated as capital expenditures, separate from operating expenses, and only the portion of that expenditure (depreciation or amortization) that is assumed to be related to the current year's operations is treated as an operating expense. The unamortized or un-depreciated portions of these capital expenses are what we see as assets on balance sheets. The expenses that result in intangible asset acquisitions are, for the most part, not treated consistently, with brand name advertising, R&D expenses and investments in recruiting/training, the expenses associated with building up brand name, patent protection and human capital, respectively, being treated as operating, rather than capital, expenses. As a consequence of this mistreatment, I have argued that not only are the biggest assets, mostly intangible, at some companies kept off the balance sheet, but their earnings are misstated:

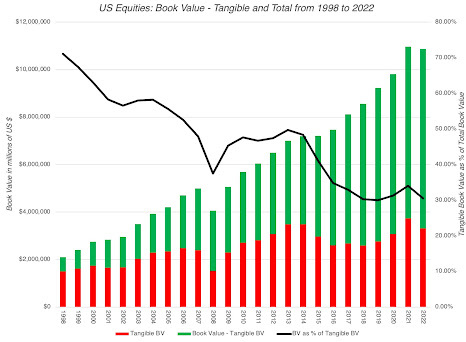

There are ways in which accounting can fix this inconsistency, but it will result in an overhaul of all of the financial statements, and companies and investors balk at wholesale revamping of accounting numbers (EBITDA, earnings per share, book value) that they have relied on to price these firms. So, how far has accounting come in bringing intangible assets on to balance sheets? One way to measure progress on this issue is to look at the portion of the book value of equity at US companies that comes from tangible assets, in the chart below:

There are ways in which accounting can fix this inconsistency, but it will result in an overhaul of all of the financial statements, and companies and investors balk at wholesale revamping of accounting numbers (EBITDA, earnings per share, book value) that they have relied on to price these firms. So, how far has accounting come in bringing intangible assets on to balance sheets? One way to measure progress on this issue is to look at the portion of the book value of equity at US companies that comes from tangible assets, in the chart below:

Looking across all US firms from 1980 to 2022, the portion of book value of equity that comes tangible assets has dropped from more than 70% in 1998 to about 30% in 2022. That would suggest that intangible assets are being valued and incorporated into balance sheets much more now than in the past. Before you come to that conclusion, though, you may want to consider the breakdown of the intangible assets on accounting balance sheets, which I do in the graph below:

Looking across all US firms from 1980 to 2022, the portion of book value of equity that comes tangible assets has dropped from more than 70% in 1998 to about 30% in 2022. That would suggest that intangible assets are being valued and incorporated into balance sheets much more now than in the past. Before you come to that conclusion, though, you may want to consider the breakdown of the intangible assets on accounting balance sheets, which I do in the graph below:

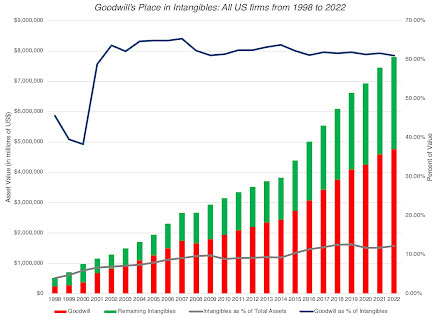

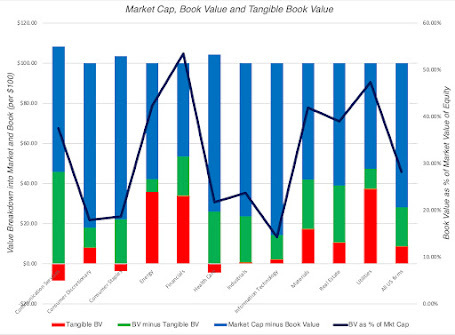

Over the last 25 years, as intangible assets have risen in value, goodwill has been, by far, the biggest single component of that value, accounting for about 60% of all intangibles on US corporate balance sheets; the jump in 2001 came from a change in accounting rules on acquisitions, when pooling was banned and companies were forced to recognize goodwill on all acquisitions. So what? I have long argued that goodwill is not an asset, intangible or not, but more a plug variable, signifying the difference between the price paid to acquire a target company and its book value, with adjustments for fairness, and designed to make balance sheets balance. Thus, much of the talk about intangibles in accounting has been just that, talk, with little of real consequence for balance sheets. There is another measure that you can use to see the futility, at least so far, of accounting attempts to value intangibles. In the graph below, I look at the aggregated market capitalization of companies, in 2022, which should incorporate the pricing of intangibles by the market, and compare that value to book value (tangible and intangible), by sector, reflecting accounting attempts to value these same intangibles.

The sectors where you would expect intangible assets to be the largest portion of value are consumer products (brand name) and technology (R&D and patents). These are also the sectors with the lowest book values, relative to market value, suggesting that whatever accountants are doing to bring in intangibles in these companies into book value is not having a tangible effect on the numbers. In sum, the accounting obsession with intangibles, and how best to deal with them, has not translated into material changes on balance sheets, at least with GAAP in the United States. It is true that IFRS has moved faster in bringing intangible assets on to balance sheets, albeit not always in the most sensible ways, but even with those rules in place, progress on bringing intangible assets onto balance sheets has been slow. To be frank, I don't think accounting rule writers will be able to handle intangibles in a sensible way, and the barriers lie not in rules or models, but in the accounting mindset. Accounting is backward-looking and rule-driven, making it ill equipped to value intangibles, where you have no choice, but to be forward looking, and principle-driven.

The Intrinsic Value of Intangibles

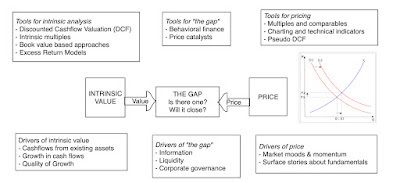

I have been teaching and writing about valuation for close to four decades now, and I have often been accused of giving short shrift to intangible assets, because I don't have a session dedicated to valuing intangibles, in my valuation class, and I don't have entire books, or even chapters of my books, on the topic. While it may seem like I am in denial, given how much value companies derive from assets you cannot see, I have never felt the need to create new models, or even modify existing models, to bring in intangibles. In this section, I will explain why and make the argument that if you do intrinsic valuation right, intangibles should be, with imagination and very little modification of existing models, already in your intrinsic value.

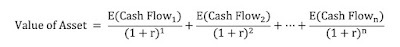

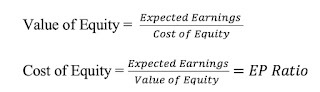

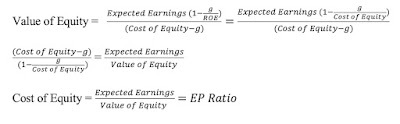

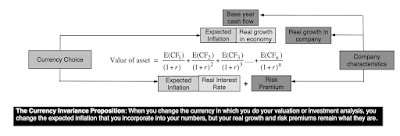

To understand intrinsic value, it is worth starting with the simple equation that animates the estimation of value, for an asset with n years of cash flows:

Thus, the intrinsic value of an asset is the present value of the expected cash flows on it, over its lifetime. When valuing a business, where cash flows could last for much longer (perhaps even forever), this equation can be adapted:

In this equation, for anything, tangible or not, has to show up in either the expected cash flows or in the risk (and the resulting discount rate); that is my "IT" proposition. This proposition has stood me in good stead, in assessing the effect on value of just about everything, from macro variables like inflation to buzzwords like ESG.

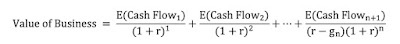

Using this framework for assessing intangible assets, from brand name to quality management, you can see that their effect on value has to come from either higher expected cash flows or lower risk (discount rates). To provide more structure to this discussion, I reframe the value equation in terms of inputs that valuation analysts should be familiar with - revenue growth, operating margins and reinvestment, driving cash flows, and equity and debt risk, determining discount rates and failure risk.

In the picture, I have highlight some of the key intangibles and which inputs are mostly likely to be affected by their presence. It is the operating margin where brand name, and the associated pricing power, is likely have its biggest effect, though it can have secondary effects on revenue growth and even the cost of capital. Good management, another highly touted intangible, will manifest in a business being able to deliver higher revenue growth, but also show up in margins and reinvestment; the essence of superior management is being able to find growth, when it is scarce, while maintaining profitability and not reinvesting too much. Connections to governments and regulators, an intangible that is seldom made explicit, can affect value by reducing failure risk and the cost of debt, while increasing growth and or profitability, as the company gets favorable treatment on bids for contracts.This is not a comprehensive list, but the framework applies to any intangible that you believe may have an effect on value. This approach to intangibles also allows you to separate valuable intangibles from wannabe intangibles, with the latter, no matter how widely sold, having little or no effect on value. Thus, a company that claims that it has a valuable brand name, while delivering operating margins well below the industry average, really does not, and the effect of ESG on value, no matter what its advocates claim, is non-existent. It is true that this approach to valuing intangibles works best for a company with a single intangible, whether it be brand name or customer loyalty, where the effect is isolated to one of the value drivers. It becomes more difficult to use for companies, like Apple, with multiple intangibles (brand name, styling, operating system, user platform). While you can still value Apple in the aggregate, breaking out how much of that value comes from each of the intangibles will be difficult, but as an investor, why does it matter?

The Birkenstock IPO: A Footwear company with intangibles

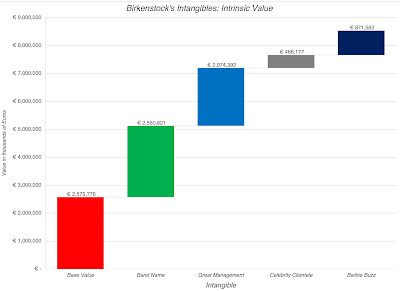

If you have found this discussion of intangibles abstract, I don't blame you, and I will try to remedy that by applying my intrinsic value framework to value Birkenstock, just ahead of its initial public offering. As a company with multiple intangible components in its story, it is well suited to the exercise, and I will try to not only estimate the value of the company with the intangibles incorporated into the numbers, but also break down the value of each of its intangibles.

The Lead In

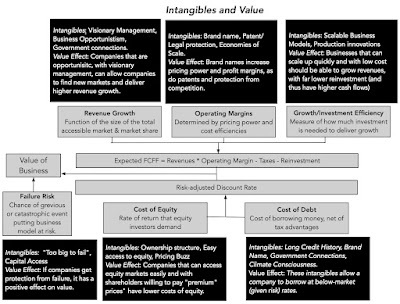

Birkenstock is primarily a footwear company, and to get perspective on growth, profitability and reinvestment in the sector, I looked at all publicly traded footwear companies across the globe. the table below summarizes key valuation metrics for the 86 listed footwear companies that were listed as of September 2023.

In the aggregate, the metrics for footwear companies are indicative of an unattractive business, with more than half the listed companies seeing revenues shrink in the decade, leading into 2022 and more than quarter reporting operating losses. However, many of these companies are small companies, with a median revenue at $170 million, struggling to stay afloat in a competitive product market. Since Birkenstock generated revenues of $1.4 billion in the twelve months leading into its initial public offering, with an expectation of more growth in the future, I zeroed in on the twelve largest companies in the apparel and footwear sector, in market capitalization, and looked at their operating metrics:

As you can see, these companies look very different from the sector aggregates, with solid revenue growth (median compounded growth rate of 8.66% a year, for the last decade) and exceptional operating margins (gross margins close to 70% and operating margins of 24%). Each of the companies also has a recognizable or many recognizable brand names, with LVMH and Hermes topping the list. In this business, at least, brand name seems to be dividing line between success and mediocrity, and having a well-recognized brand name contributes to growth and profitability. It is this grouping that I will draw on more, as I look valuing Birkenstock.

Birkenstock's History

In my work on corporate life cycles, I talk about how companies age, and how importance it is that they act accordingly. Generally, as a company moves across the life cycle, revenue growth eases, margins level off and there is less reinvestment. As a business that has been around for almost 250 years, Birkenstock should be a mature or even old company, but it has found a new lease on life in the last decade.

Birkenstock was founded in 1774 by Johann Adam Birkenstock, a Germany cobbler, and it stayed a family business for much of its life. In the decades following its founding, the company modified and adapted its footwear offerings, catering to wealthy Europeans in the growing German spa culture in the 1800s, and modifying its product line, adding flexible insoles in 1896 and pioneering arch supports in 1902. During the 1920s and 1930s, the company carved out a market around comfort and foot care, partnering with physicians and podiatrists, offering solutions for customers with foot pain. In 1963, the company introduced its first fitness sandal, the Madrid, and sandals now represent the heart of Birkenstock's product line.

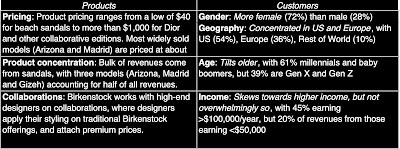

Along the way, serendipity played a role in the company's expansion. In 1966, a Californian named Margot Fraser, when visiting her native Germany, discovered that Birkenstocks helped her tired and hurting feet, and she convinced Karl Birkenstock to try selling the company's sandals in California. It is said that Karl advanced her credit, and helped her persuade reluctant California retailers to carry the company’s unconventional footwear in their stores. That proved timely, since people protesting against the war and society's ills latched on to these sandals, making them them symbolic footwear for the rebellious. in the 1990s, the brand had a rebirth, when a very young Kate Moss wore it for a cover story, and it became a hot brand, especially on college campuses. Today, Birkenstock gets more than 50% of its revenues in the United States, with multiple celebrities among its customers. The company's prospectus does a good job painting a picture of both the product offerings and customer base, leading into the IPO, and I have captured those statistics in the picture below:

Unlike some in its designer and brand name peers, the company’s products are not exorbitantly over priced and the company’s best seller, the Arizona, sells for close to $100. While the company sells more shoes to women than men, it sells footwear to a surprisingly diverse customer base, in terms of income, with 20% of its sales coming from customers who earn less than $50,000 a year, and in terms of age, with almost 40% of its revenues coming from Gen X and Gen Z members.

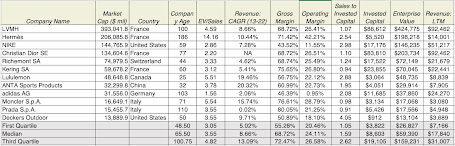

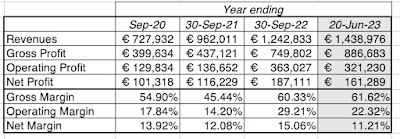

For much of its history, Birkenstock was run as a family business, capital constrained and with limited growth ambitions, perhaps explaining its long life. The turning point for the company, to get to its current form, occurred in 2012, when the family, facing internal strife, turned control of the company over to outside managers, choosing Markus Bensberg, a company veteran, and Oliver Reichert, a consultant, as co-CEOs of the company. Reichert, in particular, was a controversial pick since he was not only an outsider, but one with little experience in the shoe business, but the choice proved to be inspired. With an assist again from serendipity, when Phoebe Philo exhibited a black mink-lined Arizona on a Paris catwalk in 2012, leading to collaborations with high-end designers like Dior, the company has found a new life as a growth company, with revenues rising from €200 million in 2012 to more than €1.4 billion in the twelve months leading into the IPO, representing an 18.2% compounded annual growth rate over the decade:

Birkenstock Prospectus 2023 (October 4 filing)

Birkenstock Prospectus 2023 (October 4 filing)The surge in revenues has been particularly pronounced since 2020, the COVID year, with different theories on why the pandemic increased demand for the product; one is that people working from home chose the comfort of Birkenstocks over uncomfortable work shoes. The company's growth has come with solid profitability, and the table below shows key profit metrics over the last three years:

Birkenstock Prospectus 2023 (October 4 filing)

Birkenstock Prospectus 2023 (October 4 filing)Note that the company's operating and gross margins, at least in the last two years, match up well with the operating margins of the large, brand name apparel & footwear companies that we highlighted in the last section. It may be early to value brand name, but the company certainly has been delivering margins that put it in the brand name group.