Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 23

February 17, 2017

My Snap Story: Valuing Snap ahead of it's IPO!

Five years ago, when my daughter asked me whether I had Snapchat installed on my phone, my response was “Snapwhat?". In the weeks following, she managed to convince the rest of us in the family to install the app on our phones, if for no other reason than to admire her photo taking skills. At the time, what made the app stand out was the impermanence of the photos that you shared with your circle, since they disappeared a few seconds after you viewed them, a big selling point for sharers lacking impulse control. In 2013, when Facebook offered $3 billion to buy Snap, it was a clear indication that the new company was making inroads in the social media market, especially with teenagers. When Evan Spiegel and Bobby Murphy, Snap's founders, turned down the offer, I am sure that there were many who viewed them as insane, since Snap had trouble attracting advertisers to its platform and little in revenues, at the time. After all, what advertiser wants advertisements to disappear seconds after you see them? Needless to say, as the IPO nears and it looks like the company will be priced at $20 billion or more, it looks like Snap's founders will have the last laugh!

Snap: A Camera Company?The Snap prospectus leads off with these words: Snap Inc. is a camera company. But is it? When I think of camera companies, I think of Eastman Kodak, Polaroid and the Japanese players (Fuji, Pentax) as the old guard, under assault as they face disruption from smartphone cameras, and companies like GoPro as the new entrants in the space, struggling to convert sales to profits. I don't think that this is the company that Snap aspires to keep and since it does not sell cameras or make money on photos, it is difficult to see it fitting in. If you define business in terms of how a company plans to make money, I would argue that Snap is an advertising business, albeit one in the online or digital space. I do know that Snap has hardware that it is selling in the form of Spectacles, but at least at the moment, the glasses seem to be designed to get users to stay in the Snap ecosystem for longer and see more ads.

So, why does Snap present itself as a camera company? I think that the answer lies in the social media business, as it stands today, and how entrants either carve a niche for themselves or get labeled as me-too companies. Facebook, notwithstanding the additions of Instagram and WhatsApp, is fundamentally a platform for posting to friends, LinkedIn is a your place for business networking, Twitter is where you go if you want to reach lots of people quickly with short messages or news and Snap, as I see it, is trying to position itself as the social media platform built around visual images (photos and video). The question of whether this positioning will work, especially given Facebook's investments in Instagram and new entrants into the market, is central to what value you will attach to Snap.

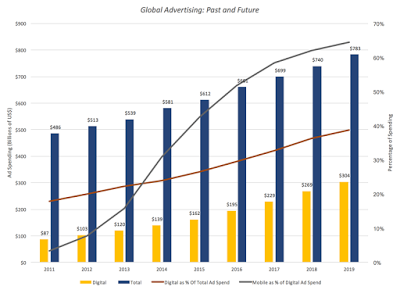

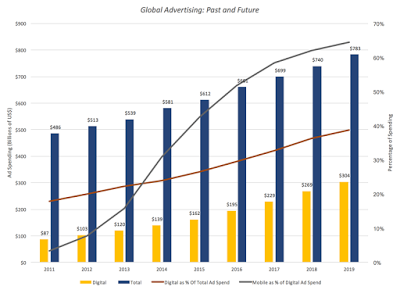

The Online Advertising BusinessIf you classify Snap as an online advertising company, the next step in the process becomes simple: identifying the total market for online advertising, the players in that market and what place you would give Snap in this market. Let’s start with some basic data on the online advertising market.It is a big market, growing and tilting to mobile: The digital online advertising market is growing, mostly at the expense of conventional advertising (newspapers, TV, billboards) etc. You can see this in the graph below, where I plot total advertising expenditures each year and the portion that is online advertising for 2011-2016 and with forecasted values for 2017-2019. In 2016, the digital ad market generated revenues globally of close to $200 billion, up from about $100 billion in 2012, and these revenues are expected to climb to over $300 billion in 2020. As a percent of total ad spending of $660 billion in 2016, digital advertising accounted for about 30% and is expected to account for almost 40% in 2020. The mobile portion of digital advertising is also increasing, claiming from about 3.45% of digital ad spending to about half of all ad spending in 2016, with the expectation that it will account for almost two thirds of all digital advertising in 2020. Sources: MultipleWith two giant players: There are two dominant players in the market, Google with its search engine and Facebook with its social media platforms. These two companies together control about 43% of the overall market, as you can see in this pie chart:

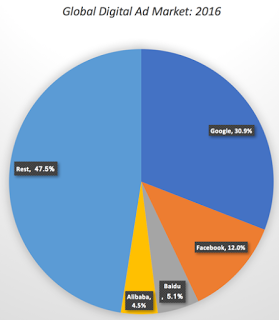

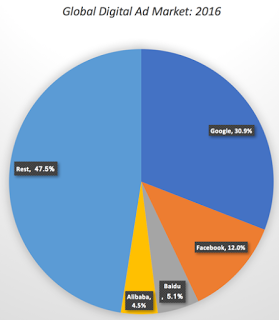

Sources: MultipleWith two giant players: There are two dominant players in the market, Google with its search engine and Facebook with its social media platforms. These two companies together control about 43% of the overall market, as you can see in this pie chart:

If you are a small player in the US market, the even scarier statistic is that these two giants are taking an even larger percentage of new online advertising than their historical share. In 2015 and 2016, for instance, Google and Facebook accounted for about two-thirds of the growth in the digital ad market. Put simply, these two companies are big and getting bigger and relentlessly aggressive about going after smaller competitors.In a post in August 2015, I argued that the size of the online advertising market may be leading both entrepreneurs and investors to over estimate their chances of both growing revenues and delivering profits, leading to what I termed the big market delusion. As Snap adds its name to the mix, that concern only gets larger, since it is not clear that the market is big enough or growing fast enough to accommodate the expectations of investors in the many companies in the space.

If you are a small player in the US market, the even scarier statistic is that these two giants are taking an even larger percentage of new online advertising than their historical share. In 2015 and 2016, for instance, Google and Facebook accounted for about two-thirds of the growth in the digital ad market. Put simply, these two companies are big and getting bigger and relentlessly aggressive about going after smaller competitors.In a post in August 2015, I argued that the size of the online advertising market may be leading both entrepreneurs and investors to over estimate their chances of both growing revenues and delivering profits, leading to what I termed the big market delusion. As Snap adds its name to the mix, that concern only gets larger, since it is not clear that the market is big enough or growing fast enough to accommodate the expectations of investors in the many companies in the space.

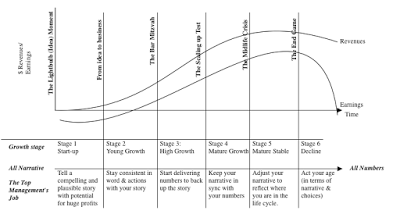

Snap: Possible Story LinesTo value a young company, especially one like Snap, you have to have a vision for what you see as success for the company, since there is little history for you to draw on and there are so many divergent paths that the company can follow, as it ages. That might sound really subjective, but without it, you are at the mercy of historical data that is both scarce and noisy or of metrics (like users and user intensity) that can lead you to misleading valuations.

Link to my bookThat is, of course, another shameless plug for my book on narrative and numbers, and if you have heard it before or have no interest in reading it, I apologize and let's go on. To get perspective on Snap, let’s start by comparing it to three social media companies, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn and to Google, the old player in the mix, at the time of their initial public offerings. The table below summarizes key numbers at the time of their IPOs, with a comparison to Snap's numbers. table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Link to my bookThat is, of course, another shameless plug for my book on narrative and numbers, and if you have heard it before or have no interest in reading it, I apologize and let's go on. To get perspective on Snap, let’s start by comparing it to three social media companies, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn and to Google, the old player in the mix, at the time of their initial public offerings. The table below summarizes key numbers at the time of their IPOs, with a comparison to Snap's numbers. table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

GoogleLinkedInFacebookTwitterSnapIPO date19-Aug-0419-May-1118-May-127-Nov-13NARevenues$1,466 $161 $3,711 $449 $405 Operating Income$326 $13 $1,756 $(93)$(521)Net Income$143 $2 $668 $(99)$(515)Number of UsersNA80.6845218161User minutes per day (January 2017)50 (Includes YouTube)NA50225Market Capitalization on offering date$23,000 $9,000 $81,000 $18,000 ?Link to Prospectus (from IPO date)Link Link Link Link Link

At the time of its IPO, Snap has less revenues than any of its peer group, other than LinkedIn, and is losing more money than any of them. Before you view this is a death knell for Snap, one reason for Snap’s big losses is that unlike its competitors, Snap pays for server space as it acquires new users, thus pushing up its operating expenses (and pushing down capital investment in servers). There is one other dimension where Snap measures up more favorably against at least two of the other companies: its users are spending more time on its platform that they were either on Twitter and LinkedIn and it ranks second only to Facebook on this dimension.

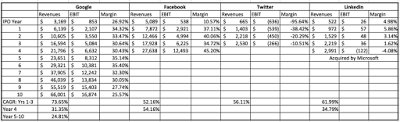

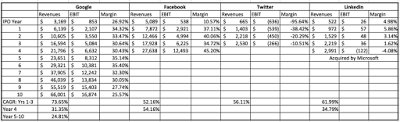

The more important question that you face with Snap, then, is which of these companies it will emulate in its post IPO year. The table below provides the contrast rather by looking at the years since the IPO for each company. Google and Facebook stand out as success stories, Google because it has maintained high revenue growth for almost a decade with very good profit margins and Facebook doing even better on both dimensions (higher growth in the earlier years and even higher margins). The least successful company in this mix is Twitter which has seen revenue growth that has trailed expectations and has been unable to unlock the secret to monetizing its user base, as it continues to post losses. Linkedin falls in the middle, with solid revenue growth for its first four years and some profits, but its margins are not only small but showed no signs of improvement from year to year. Now that it has been acquired by Microsoft, it will be interesting to see if the combination translates into better growth and margins.

Google and Facebook stand out as success stories, Google because it has maintained high revenue growth for almost a decade with very good profit margins and Facebook doing even better on both dimensions (higher growth in the earlier years and even higher margins). The least successful company in this mix is Twitter which has seen revenue growth that has trailed expectations and has been unable to unlock the secret to monetizing its user base, as it continues to post losses. Linkedin falls in the middle, with solid revenue growth for its first four years and some profits, but its margins are not only small but showed no signs of improvement from year to year. Now that it has been acquired by Microsoft, it will be interesting to see if the combination translates into better growth and margins.

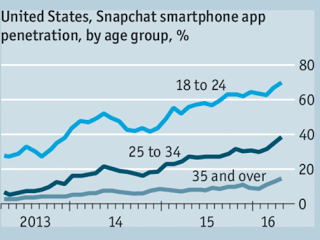

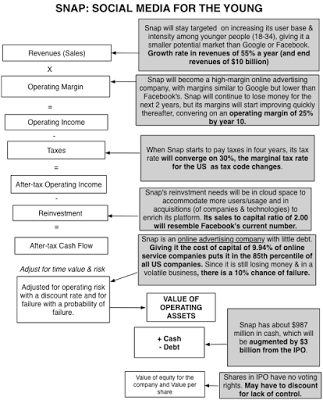

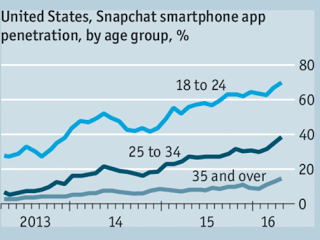

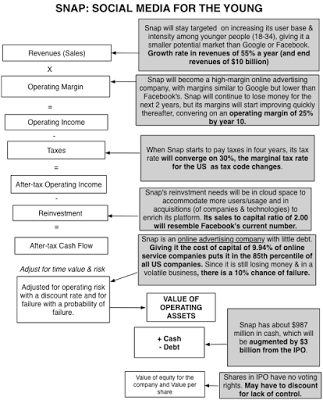

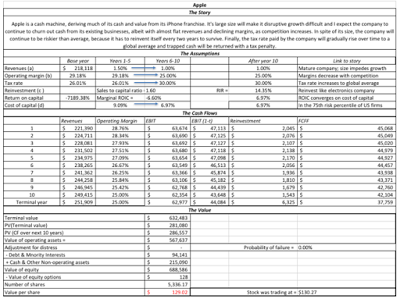

My Snap Story & ValuationTo value Snap, I built my story by looking at what its founders have said about the company, how its structured and the strengths and weaknesses of its platform, at least as I see them. As a consequence, here is what I see the company evolving.Snap will remain focused on online advertising: I believe that Snap's revenues will continue to come entirely or predominantly from advertising. Thus, the payoff to Spectacles or any other hardware offered by the company will be in more advertising for the company. Marketing to younger, tech-savvy users: Snap's platform, with its emphasis on the visual and the temporary, will remain more attractive to younger users. Rather than dilute the platform to go after the bigger market, Snap will create offerings to increase its hold on the youth segment of the market. Source: The EconomistWith an emphasis on user intensity over users: Snap's prospectus and public utterances by its founders emphasize user intensity more than the number of users, in contrast to earlier social media companies. This emphasis is backed up by the company's actions: the new features that it has added, like stories and geofilters, seem designed more to increase how much time users spend in the app than on getting new users. Some of that shift in emphasis reflects changes in how investors perceive social media companies, perhaps sobered by Twitter's failure to convert large user numbers into profits, and some of it is in Snap's business model, where adding users is not costless (since it has to pay for server space). These assumptions, in turn, drive my forecasts of revenues, margins and reinvestment. In my story, I don't see Snap reaching revenues of the magnitude delivered by Google and Facebook, the two big market players in the game, settling instead for smaller revenues. If Snap is able to hold on to its target market (young, tech savvy and visually inclined) and keep its users engaged, I think Snap has a chance of delivering high operating profit margins, perhaps not of the magnitude of Facebook today (45% margin) but close to that of Google (25% margin). Finally, its reinvestment will take the form of acquisition of technology and server space to sustain its user base, but by not trying to be the next Facebook, it will not have to over reach. Is there substantial risk that the story may not work out the way I expect it to? Of course! While I will give Snap a cost of capital of close to 10% (and in the 85th percentile of US companies), reflective of its online advertising business, I will also assume that there remains a non-trivial chance (10%) that the company will not make it. The picture below captures my story and the valuation inputs that emerge from it:

Source: The EconomistWith an emphasis on user intensity over users: Snap's prospectus and public utterances by its founders emphasize user intensity more than the number of users, in contrast to earlier social media companies. This emphasis is backed up by the company's actions: the new features that it has added, like stories and geofilters, seem designed more to increase how much time users spend in the app than on getting new users. Some of that shift in emphasis reflects changes in how investors perceive social media companies, perhaps sobered by Twitter's failure to convert large user numbers into profits, and some of it is in Snap's business model, where adding users is not costless (since it has to pay for server space). These assumptions, in turn, drive my forecasts of revenues, margins and reinvestment. In my story, I don't see Snap reaching revenues of the magnitude delivered by Google and Facebook, the two big market players in the game, settling instead for smaller revenues. If Snap is able to hold on to its target market (young, tech savvy and visually inclined) and keep its users engaged, I think Snap has a chance of delivering high operating profit margins, perhaps not of the magnitude of Facebook today (45% margin) but close to that of Google (25% margin). Finally, its reinvestment will take the form of acquisition of technology and server space to sustain its user base, but by not trying to be the next Facebook, it will not have to over reach. Is there substantial risk that the story may not work out the way I expect it to? Of course! While I will give Snap a cost of capital of close to 10% (and in the 85th percentile of US companies), reflective of its online advertising business, I will also assume that there remains a non-trivial chance (10%) that the company will not make it. The picture below captures my story and the valuation inputs that emerge from it:

To complete the valuation, there are two other details that relate to the IPO.

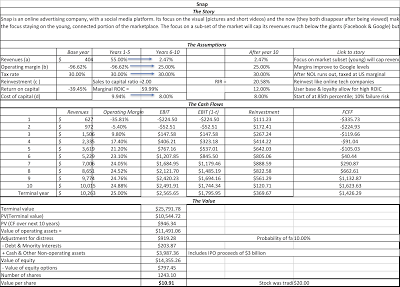

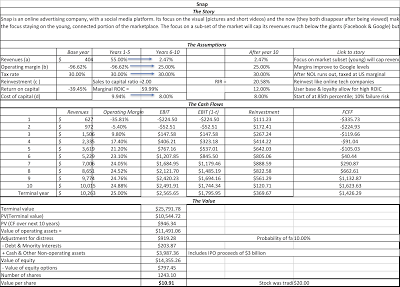

Share count: For an IPO, share count can be tricky, and especially so for a young tech company with multiple claims on equity in the form of options and restricted stock issues. Looking through the prospectus and adding up the shares outstanding on all three classes of shares, including shares set aside for restricted stock issues and assorted purposes, I get a total of 1,243.10 million shares outstanding in the company. In addition, I estimate that there are 44.90 million options outstanding in the company, with an average exercise price of $2.33 and an assumed maturity of 3 years.IPO Proceeds: This is a factor specific to IPOs and reflect the fact that cash is raised by the company on the offering date. If that cash is retained by the company, it adds to the value of the company (a version of post-money valuation). In the case of Snap, it is estimated that roughly $3 billion in cash from the offering that will be held by the company, to cover costs like the $2 billion that Snap has contracted to pay Google for cloud space for the next five years.These valuation inputs become the basis for my valuation and yield a value of $14.4 billion for the equity (and you can download the spreadsheet at this link).

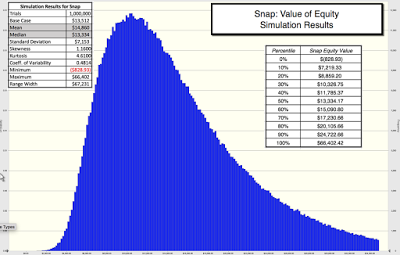

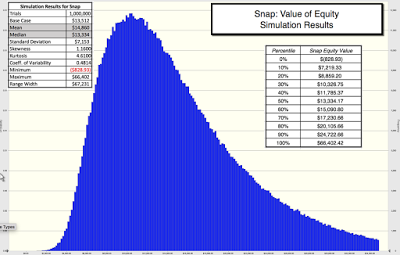

Download spreadsheetAllowing for the uncertainty inherent in my estimates, I also computed probability distribution for three key inputs, revenue growth, operating margin and cost of capital, and my value for Snap's equity is in the distribution below:

Download spreadsheetAllowing for the uncertainty inherent in my estimates, I also computed probability distribution for three key inputs, revenue growth, operating margin and cost of capital, and my value for Snap's equity is in the distribution below:

Snap Simulation DetailsAssuming that my share count is right, my value per share is about $11 per share. As you can see though, as is the case with almost any young company where the narrative can take you in other directions, there is a wide range around my expectations, with the lowest value being less than zero and the highest value pushing above $66 billion ($50/share). The median value is $13.3 billion and the average is $14.9 billion; one attractive feature to investors is that there is potential for breakout values (optionality) that exceed $30 billion.

Snap Simulation DetailsAssuming that my share count is right, my value per share is about $11 per share. As you can see though, as is the case with almost any young company where the narrative can take you in other directions, there is a wide range around my expectations, with the lowest value being less than zero and the highest value pushing above $66 billion ($50/share). The median value is $13.3 billion and the average is $14.9 billion; one attractive feature to investors is that there is potential for breakout values (optionality) that exceed $30 billion.

The numbers at the high end of the spectrum reflect a pathway for Snap that I call the Facebook Light story, where it emerges as a serious contender to Facebook in terms of time that users spend on its platform, but with a smaller user base. That leads to revenues of close to $25 billion by 2027, an operating margin of 40% for the company and a value for the equity of $48 billion.The numbers at the other end of the spectrum capture a darker version of the story, that I label Twitter Redux, where user growth slows, user intensity comes under stress and advertising lags expectations. In this variant, Snap will have trouble getting pushing revenue growth past 35%, settling for about $4 billion in revenues in 2027, is able to improve its margin to only 10% in steady state, yielding a value of equity of about $4 billion.As I learned the painful way with my Twitter experiences, the quality of the management at a young company can play a significant role in how the story evolves. I am impressed with both the poise that Snap's founders are showing in their public appearances and the story that they are telling about the company, though I am disappointed that they have followed the Google/Facebook path and consolidated control in the company by creating shares with different voting rights. I know that is in keeping with the tech sector's founder worship and paranoia about "short term" investors , but my advice, unsolicited and perhaps unwelcome, is that Snap's founders should trust markets more. After all, if you welcome me to invest me in your company and I do, you should want my input as well, right?

The Pricing Contrast

As I finish this post, I notice this news story from this morning that suggests that bankers have arrived at an offering price, yielding a pricing for the company of $18.5 billion to $21.5 billion for the company, about $4 billion above my estimate. So, how do I explain the difference between my valuation and this pricing? First, I have never felt the urge to explain what other people pay for a stock, since it is a free market and investors make their own judgments. Second, and this is keeping with a theme that I have promoted repeatedly in my posts, bankers don't value companies; they price them! If you are missing the contrast between value and price, you are welcome to read this piece that I have on the topic, but simply put, your job in pricing is not to assess the fair value of a company but to decide what investors will pay for the company today. The former is determined by cash flows, growth and risk, i.e., the inputs that I have grappled with in my story and valuation, and the latter is set by what investors are paying for other companies in the space. After all, if investors are willing to attach a pricing of $12 billion to Twitter, a social media company seeming incapable of translating potential to profits, and Microsoft is paying $26 billion for LinkedIn, another social media company whose grasp exceeded its reach, why should they not pay $20 billion for Snap, a company with vastly greater user engagement than either LinkedIn or Twitter? With pricing, everything is relative and Snap may be a bargain at $20 billion to a trader.

YouTube Video

Link to book

Narrative and Numbers: The Value of Stories in BusinessAttachments

Snap: Prospectus for IPOSnap: My IPO ValuationSnap: As Facebook LiteSnap: As Twitter ReduxSnap: Simulation Inputs & Output

Snap: A Camera Company?The Snap prospectus leads off with these words: Snap Inc. is a camera company. But is it? When I think of camera companies, I think of Eastman Kodak, Polaroid and the Japanese players (Fuji, Pentax) as the old guard, under assault as they face disruption from smartphone cameras, and companies like GoPro as the new entrants in the space, struggling to convert sales to profits. I don't think that this is the company that Snap aspires to keep and since it does not sell cameras or make money on photos, it is difficult to see it fitting in. If you define business in terms of how a company plans to make money, I would argue that Snap is an advertising business, albeit one in the online or digital space. I do know that Snap has hardware that it is selling in the form of Spectacles, but at least at the moment, the glasses seem to be designed to get users to stay in the Snap ecosystem for longer and see more ads.

So, why does Snap present itself as a camera company? I think that the answer lies in the social media business, as it stands today, and how entrants either carve a niche for themselves or get labeled as me-too companies. Facebook, notwithstanding the additions of Instagram and WhatsApp, is fundamentally a platform for posting to friends, LinkedIn is a your place for business networking, Twitter is where you go if you want to reach lots of people quickly with short messages or news and Snap, as I see it, is trying to position itself as the social media platform built around visual images (photos and video). The question of whether this positioning will work, especially given Facebook's investments in Instagram and new entrants into the market, is central to what value you will attach to Snap.

The Online Advertising BusinessIf you classify Snap as an online advertising company, the next step in the process becomes simple: identifying the total market for online advertising, the players in that market and what place you would give Snap in this market. Let’s start with some basic data on the online advertising market.It is a big market, growing and tilting to mobile: The digital online advertising market is growing, mostly at the expense of conventional advertising (newspapers, TV, billboards) etc. You can see this in the graph below, where I plot total advertising expenditures each year and the portion that is online advertising for 2011-2016 and with forecasted values for 2017-2019. In 2016, the digital ad market generated revenues globally of close to $200 billion, up from about $100 billion in 2012, and these revenues are expected to climb to over $300 billion in 2020. As a percent of total ad spending of $660 billion in 2016, digital advertising accounted for about 30% and is expected to account for almost 40% in 2020. The mobile portion of digital advertising is also increasing, claiming from about 3.45% of digital ad spending to about half of all ad spending in 2016, with the expectation that it will account for almost two thirds of all digital advertising in 2020.

Sources: MultipleWith two giant players: There are two dominant players in the market, Google with its search engine and Facebook with its social media platforms. These two companies together control about 43% of the overall market, as you can see in this pie chart:

Sources: MultipleWith two giant players: There are two dominant players in the market, Google with its search engine and Facebook with its social media platforms. These two companies together control about 43% of the overall market, as you can see in this pie chart:

If you are a small player in the US market, the even scarier statistic is that these two giants are taking an even larger percentage of new online advertising than their historical share. In 2015 and 2016, for instance, Google and Facebook accounted for about two-thirds of the growth in the digital ad market. Put simply, these two companies are big and getting bigger and relentlessly aggressive about going after smaller competitors.In a post in August 2015, I argued that the size of the online advertising market may be leading both entrepreneurs and investors to over estimate their chances of both growing revenues and delivering profits, leading to what I termed the big market delusion. As Snap adds its name to the mix, that concern only gets larger, since it is not clear that the market is big enough or growing fast enough to accommodate the expectations of investors in the many companies in the space.

If you are a small player in the US market, the even scarier statistic is that these two giants are taking an even larger percentage of new online advertising than their historical share. In 2015 and 2016, for instance, Google and Facebook accounted for about two-thirds of the growth in the digital ad market. Put simply, these two companies are big and getting bigger and relentlessly aggressive about going after smaller competitors.In a post in August 2015, I argued that the size of the online advertising market may be leading both entrepreneurs and investors to over estimate their chances of both growing revenues and delivering profits, leading to what I termed the big market delusion. As Snap adds its name to the mix, that concern only gets larger, since it is not clear that the market is big enough or growing fast enough to accommodate the expectations of investors in the many companies in the space. Snap: Possible Story LinesTo value a young company, especially one like Snap, you have to have a vision for what you see as success for the company, since there is little history for you to draw on and there are so many divergent paths that the company can follow, as it ages. That might sound really subjective, but without it, you are at the mercy of historical data that is both scarce and noisy or of metrics (like users and user intensity) that can lead you to misleading valuations.

Link to my bookThat is, of course, another shameless plug for my book on narrative and numbers, and if you have heard it before or have no interest in reading it, I apologize and let's go on. To get perspective on Snap, let’s start by comparing it to three social media companies, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn and to Google, the old player in the mix, at the time of their initial public offerings. The table below summarizes key numbers at the time of their IPOs, with a comparison to Snap's numbers. table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Link to my bookThat is, of course, another shameless plug for my book on narrative and numbers, and if you have heard it before or have no interest in reading it, I apologize and let's go on. To get perspective on Snap, let’s start by comparing it to three social media companies, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn and to Google, the old player in the mix, at the time of their initial public offerings. The table below summarizes key numbers at the time of their IPOs, with a comparison to Snap's numbers. table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; } GoogleLinkedInFacebookTwitterSnapIPO date19-Aug-0419-May-1118-May-127-Nov-13NARevenues$1,466 $161 $3,711 $449 $405 Operating Income$326 $13 $1,756 $(93)$(521)Net Income$143 $2 $668 $(99)$(515)Number of UsersNA80.6845218161User minutes per day (January 2017)50 (Includes YouTube)NA50225Market Capitalization on offering date$23,000 $9,000 $81,000 $18,000 ?Link to Prospectus (from IPO date)Link Link Link Link Link

At the time of its IPO, Snap has less revenues than any of its peer group, other than LinkedIn, and is losing more money than any of them. Before you view this is a death knell for Snap, one reason for Snap’s big losses is that unlike its competitors, Snap pays for server space as it acquires new users, thus pushing up its operating expenses (and pushing down capital investment in servers). There is one other dimension where Snap measures up more favorably against at least two of the other companies: its users are spending more time on its platform that they were either on Twitter and LinkedIn and it ranks second only to Facebook on this dimension.

The more important question that you face with Snap, then, is which of these companies it will emulate in its post IPO year. The table below provides the contrast rather by looking at the years since the IPO for each company.

Google and Facebook stand out as success stories, Google because it has maintained high revenue growth for almost a decade with very good profit margins and Facebook doing even better on both dimensions (higher growth in the earlier years and even higher margins). The least successful company in this mix is Twitter which has seen revenue growth that has trailed expectations and has been unable to unlock the secret to monetizing its user base, as it continues to post losses. Linkedin falls in the middle, with solid revenue growth for its first four years and some profits, but its margins are not only small but showed no signs of improvement from year to year. Now that it has been acquired by Microsoft, it will be interesting to see if the combination translates into better growth and margins.

Google and Facebook stand out as success stories, Google because it has maintained high revenue growth for almost a decade with very good profit margins and Facebook doing even better on both dimensions (higher growth in the earlier years and even higher margins). The least successful company in this mix is Twitter which has seen revenue growth that has trailed expectations and has been unable to unlock the secret to monetizing its user base, as it continues to post losses. Linkedin falls in the middle, with solid revenue growth for its first four years and some profits, but its margins are not only small but showed no signs of improvement from year to year. Now that it has been acquired by Microsoft, it will be interesting to see if the combination translates into better growth and margins.My Snap Story & ValuationTo value Snap, I built my story by looking at what its founders have said about the company, how its structured and the strengths and weaknesses of its platform, at least as I see them. As a consequence, here is what I see the company evolving.Snap will remain focused on online advertising: I believe that Snap's revenues will continue to come entirely or predominantly from advertising. Thus, the payoff to Spectacles or any other hardware offered by the company will be in more advertising for the company. Marketing to younger, tech-savvy users: Snap's platform, with its emphasis on the visual and the temporary, will remain more attractive to younger users. Rather than dilute the platform to go after the bigger market, Snap will create offerings to increase its hold on the youth segment of the market.

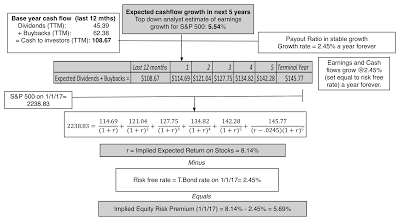

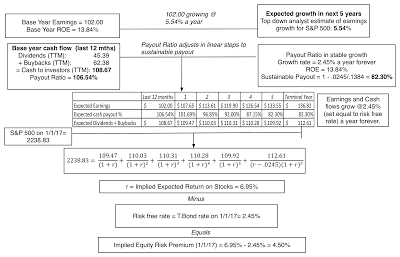

Source: The EconomistWith an emphasis on user intensity over users: Snap's prospectus and public utterances by its founders emphasize user intensity more than the number of users, in contrast to earlier social media companies. This emphasis is backed up by the company's actions: the new features that it has added, like stories and geofilters, seem designed more to increase how much time users spend in the app than on getting new users. Some of that shift in emphasis reflects changes in how investors perceive social media companies, perhaps sobered by Twitter's failure to convert large user numbers into profits, and some of it is in Snap's business model, where adding users is not costless (since it has to pay for server space). These assumptions, in turn, drive my forecasts of revenues, margins and reinvestment. In my story, I don't see Snap reaching revenues of the magnitude delivered by Google and Facebook, the two big market players in the game, settling instead for smaller revenues. If Snap is able to hold on to its target market (young, tech savvy and visually inclined) and keep its users engaged, I think Snap has a chance of delivering high operating profit margins, perhaps not of the magnitude of Facebook today (45% margin) but close to that of Google (25% margin). Finally, its reinvestment will take the form of acquisition of technology and server space to sustain its user base, but by not trying to be the next Facebook, it will not have to over reach. Is there substantial risk that the story may not work out the way I expect it to? Of course! While I will give Snap a cost of capital of close to 10% (and in the 85th percentile of US companies), reflective of its online advertising business, I will also assume that there remains a non-trivial chance (10%) that the company will not make it. The picture below captures my story and the valuation inputs that emerge from it:

Source: The EconomistWith an emphasis on user intensity over users: Snap's prospectus and public utterances by its founders emphasize user intensity more than the number of users, in contrast to earlier social media companies. This emphasis is backed up by the company's actions: the new features that it has added, like stories and geofilters, seem designed more to increase how much time users spend in the app than on getting new users. Some of that shift in emphasis reflects changes in how investors perceive social media companies, perhaps sobered by Twitter's failure to convert large user numbers into profits, and some of it is in Snap's business model, where adding users is not costless (since it has to pay for server space). These assumptions, in turn, drive my forecasts of revenues, margins and reinvestment. In my story, I don't see Snap reaching revenues of the magnitude delivered by Google and Facebook, the two big market players in the game, settling instead for smaller revenues. If Snap is able to hold on to its target market (young, tech savvy and visually inclined) and keep its users engaged, I think Snap has a chance of delivering high operating profit margins, perhaps not of the magnitude of Facebook today (45% margin) but close to that of Google (25% margin). Finally, its reinvestment will take the form of acquisition of technology and server space to sustain its user base, but by not trying to be the next Facebook, it will not have to over reach. Is there substantial risk that the story may not work out the way I expect it to? Of course! While I will give Snap a cost of capital of close to 10% (and in the 85th percentile of US companies), reflective of its online advertising business, I will also assume that there remains a non-trivial chance (10%) that the company will not make it. The picture below captures my story and the valuation inputs that emerge from it:

To complete the valuation, there are two other details that relate to the IPO.

Share count: For an IPO, share count can be tricky, and especially so for a young tech company with multiple claims on equity in the form of options and restricted stock issues. Looking through the prospectus and adding up the shares outstanding on all three classes of shares, including shares set aside for restricted stock issues and assorted purposes, I get a total of 1,243.10 million shares outstanding in the company. In addition, I estimate that there are 44.90 million options outstanding in the company, with an average exercise price of $2.33 and an assumed maturity of 3 years.IPO Proceeds: This is a factor specific to IPOs and reflect the fact that cash is raised by the company on the offering date. If that cash is retained by the company, it adds to the value of the company (a version of post-money valuation). In the case of Snap, it is estimated that roughly $3 billion in cash from the offering that will be held by the company, to cover costs like the $2 billion that Snap has contracted to pay Google for cloud space for the next five years.These valuation inputs become the basis for my valuation and yield a value of $14.4 billion for the equity (and you can download the spreadsheet at this link).

Download spreadsheetAllowing for the uncertainty inherent in my estimates, I also computed probability distribution for three key inputs, revenue growth, operating margin and cost of capital, and my value for Snap's equity is in the distribution below:

Download spreadsheetAllowing for the uncertainty inherent in my estimates, I also computed probability distribution for three key inputs, revenue growth, operating margin and cost of capital, and my value for Snap's equity is in the distribution below: Snap Simulation DetailsAssuming that my share count is right, my value per share is about $11 per share. As you can see though, as is the case with almost any young company where the narrative can take you in other directions, there is a wide range around my expectations, with the lowest value being less than zero and the highest value pushing above $66 billion ($50/share). The median value is $13.3 billion and the average is $14.9 billion; one attractive feature to investors is that there is potential for breakout values (optionality) that exceed $30 billion.

Snap Simulation DetailsAssuming that my share count is right, my value per share is about $11 per share. As you can see though, as is the case with almost any young company where the narrative can take you in other directions, there is a wide range around my expectations, with the lowest value being less than zero and the highest value pushing above $66 billion ($50/share). The median value is $13.3 billion and the average is $14.9 billion; one attractive feature to investors is that there is potential for breakout values (optionality) that exceed $30 billion.The numbers at the high end of the spectrum reflect a pathway for Snap that I call the Facebook Light story, where it emerges as a serious contender to Facebook in terms of time that users spend on its platform, but with a smaller user base. That leads to revenues of close to $25 billion by 2027, an operating margin of 40% for the company and a value for the equity of $48 billion.The numbers at the other end of the spectrum capture a darker version of the story, that I label Twitter Redux, where user growth slows, user intensity comes under stress and advertising lags expectations. In this variant, Snap will have trouble getting pushing revenue growth past 35%, settling for about $4 billion in revenues in 2027, is able to improve its margin to only 10% in steady state, yielding a value of equity of about $4 billion.As I learned the painful way with my Twitter experiences, the quality of the management at a young company can play a significant role in how the story evolves. I am impressed with both the poise that Snap's founders are showing in their public appearances and the story that they are telling about the company, though I am disappointed that they have followed the Google/Facebook path and consolidated control in the company by creating shares with different voting rights. I know that is in keeping with the tech sector's founder worship and paranoia about "short term" investors , but my advice, unsolicited and perhaps unwelcome, is that Snap's founders should trust markets more. After all, if you welcome me to invest me in your company and I do, you should want my input as well, right?

The Pricing Contrast

As I finish this post, I notice this news story from this morning that suggests that bankers have arrived at an offering price, yielding a pricing for the company of $18.5 billion to $21.5 billion for the company, about $4 billion above my estimate. So, how do I explain the difference between my valuation and this pricing? First, I have never felt the urge to explain what other people pay for a stock, since it is a free market and investors make their own judgments. Second, and this is keeping with a theme that I have promoted repeatedly in my posts, bankers don't value companies; they price them! If you are missing the contrast between value and price, you are welcome to read this piece that I have on the topic, but simply put, your job in pricing is not to assess the fair value of a company but to decide what investors will pay for the company today. The former is determined by cash flows, growth and risk, i.e., the inputs that I have grappled with in my story and valuation, and the latter is set by what investors are paying for other companies in the space. After all, if investors are willing to attach a pricing of $12 billion to Twitter, a social media company seeming incapable of translating potential to profits, and Microsoft is paying $26 billion for LinkedIn, another social media company whose grasp exceeded its reach, why should they not pay $20 billion for Snap, a company with vastly greater user engagement than either LinkedIn or Twitter? With pricing, everything is relative and Snap may be a bargain at $20 billion to a trader.

YouTube Video

Link to book

Narrative and Numbers: The Value of Stories in BusinessAttachments

Snap: Prospectus for IPOSnap: My IPO ValuationSnap: As Facebook LiteSnap: As Twitter ReduxSnap: Simulation Inputs & Output

Published on February 17, 2017 08:48

February 9, 2017

Apple: The Greatest Cash Machine in History?

As as sports fan, watching Brady and Belichick win the Super Bowl, Roger Federer triumph at the Australian Open and LeBron James carry the Cleveland Cavaliers to victory over the Warriors, it struck me how we take uncommon brilliance for granted. It is so easy, in the moment, to find fault, as many have, with these superstars and miss how special they are. That was the same reaction that I had as I watched another earnings report from Apple and the usual mix of reactions to it, some ho hum that the company made only $45 billion last year, some relieved that the company was able to post a 3% growth rate in revenues and the usual breast beating from those who found fault with it for not delivering another earth-shaking disruption. Since this is a company that I have valued after every quarterly earnings report since 2010, I thought this would be a good time to both take stock of what the company has managed to do over the last decade and to value it, given where it stands today.

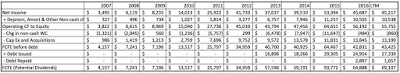

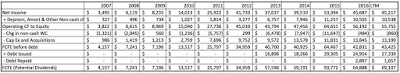

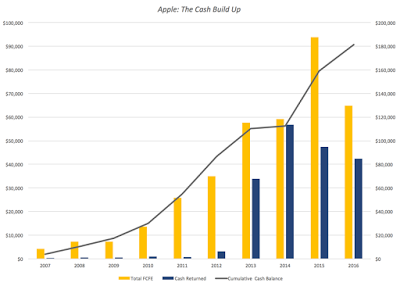

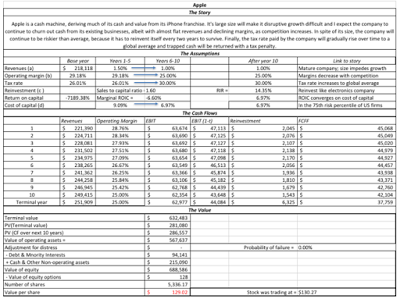

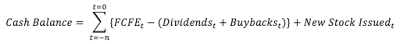

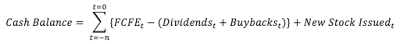

The Cash Machine Revs upIn my last post on dividend payout and cash return globally, I noted that large cash balances don't happen by accident but are a direct result of companies paying out less than they have available as potential dividends or free cash flows to equity, year after year. Since Apple's cash balance almost reached $250 billion in its most recent quarterly report, by far the largest cash balance ever accumulated by a publicly traded company, I decided that the place to start was by looking at how it got to its current level. I started by collecting the operating, debt financing and reinvestment cash flows each year from 2007 to 2016 and computing a free cash flow to equity (or potential dividend) each year.

Starting in 2013, when Apple started to tap into its debt capacity, the company has been able to add to its potential dividends each year. In 2015 alone, Apple generated $93.6 billion in FCFE or potential dividends, an astounding amount, larger that the GDP of half the countries in the world in 2015. Each year, I also looked at how much Apple has returned to stockholders in the form of dividends and stock buybacks.

Starting in 2013, when Apple started to tap into its debt capacity, the company has been able to add to its potential dividends each year. In 2015 alone, Apple generated $93.6 billion in FCFE or potential dividends, an astounding amount, larger that the GDP of half the countries in the world in 2015. Each year, I also looked at how much Apple has returned to stockholders in the form of dividends and stock buybacks.

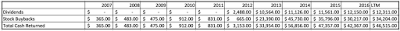

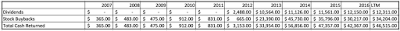

Note that while Apple took a while to start returning cash, and it needed prompting from David Einhorn and Carl Icahn, it not only initiated dividends in 2012 but has supplemented those dividends with stock buybacks of increasing magnitude each year. In fact, Apple returned $183 billion in cash to stockholders in the last five years, making it, by far, the largest cash-returner in the world over that period.

Note that while Apple took a while to start returning cash, and it needed prompting from David Einhorn and Carl Icahn, it not only initiated dividends in 2012 but has supplemented those dividends with stock buybacks of increasing magnitude each year. In fact, Apple returned $183 billion in cash to stockholders in the last five years, making it, by far, the largest cash-returner in the world over that period.

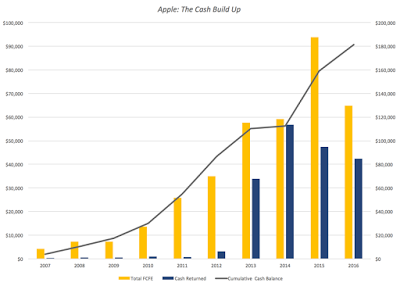

There are two amazing (at least to me) aspects to this story. The first is that in spite of the immense amounts of cash that Apple has returned each year, its cash balance has increased each year, partly because its operating cash flows are so high and partly because they are being supplemented by debt payments. You can see the cash build up between 2007 and 2016 in the chart below:

Note that while Apple was returning $183 billion in cash between 2013-2016, its cash balance continued to increase, as its cash inflows increased even more. If having a cash spigot that never turns off is a problem, Apple has it, but I am sure that it will not get about as much sympathy from the rest of the world as a supermodel who complains that she cannot put on weight, no matter how much she eats. The other equally surprising feature of this story is that Apple's managers have not felt the urge (yet) to use their huge cash reserves to buy a company, a whole set of companies or even an entire country, a fact that those who like Apple will attribute to the discipline of its management and Apple haters will argue is due to a lack of imagination.

My Apple Valuation HistoryAs many of you who have been reading this blog are aware, I have valued Apple many times before but rather than rehash old history, let me summarize. For Apple, the story that I have been telling about the company for the last five years has been remarkably unchanged. In my July 2012 valuation, where I looked at Apple just after it had become the largest market cap company in the world and had come off perhaps the greatest decade of disruption of any company in history (iTunes, iPod, iPhone and iPad), I concluded that while Apple was one of the great cash machines of all time, its days of disruption were behind it, partly because Steve Jobs was no longer at the helm but mostly because of its size; it is so much more difficult for a $600 billion company to create a significant enough disruption to change the trend lines on earnings, cash flows and value.

So, in my story, I saw Apple continuing to produce cash flows, with low revenue growth and gradually decreasing margins, as the smartphone business became more competitive. I won't make you read all of the posts that I have on Apple, but let me start with a post that I had in August 2015, when I updated the Apple story (and looked at Facebook and Twitter at the same time). The value I estimated for Apple in that post was $130, higher than the stock price of $110 at the time, prompting me to buy the stock. I revisited the story after an earnings report from Apple in February 2016 and compared it to Alphabet. At the time, I valued Apple at about $126 per share, well above the $94/share that it was trading at the time. In May 2016, Carl Icahn, a long time bull on Apple sold his shares, and Warren Buffett, a long time avoider of tech companies, bought shares in the company. In a Apple's Earnings Report & My NarrativeLast week, Apple released its latest 10Q and in conjunction with its latest 10K (Apple's fiscal year end is in September). It contained a modicum of good news, insofar as there was growth in revenues as opposed to the decline posted in the prior quarter and still-solid profit margins, but the revenue growth was only 3% and the margins are still lower than they used to be. Using the numbers in the most recent report, I took at look at my Apple story and guess what? It looks just like it did last year, a great cash machine, with very slow-growing revenues and declining margins. Using the process that I describe, perhaps in too much detail in my book on narrative and numbers, I converted my story in inputs to my valuation:

Some of you may find my story too cramped , seeing a greater possibility than I do of Apple breaking through into a new, big market (with Apple Pay or the Apple iCar). If you are in that group, please take my structure and make it yours, with a higher growth rate coming from your disruptive story, accompanied by lower margins and higher reinvestment. Others may find this story too optimistic, perhaps seeing a more precipitous fall of profit margins in the smart phone business and a greater tax liability from trapped cash. You too can alter the inputs to your liking and make your own judgment on Apple!

An Updated Valuation of AppleOnce you have a story for a company and convert that story into valuation inputs, the rest of the process becomes just mechanics. In the picture below, I have my February 2017 valuation of Apple. Download spreadsheet with valuationJust as my valuation looked too optimistic a year, when the earnings report contained darker news, it may seem too pessimistic this year, after a much sunnier report. That said, it is worth emphasizing how much Apple is on the iPhone roller coaster ride, reporting better earnings in the quarters immediately after a new iPhone is released and much worse earnings in the quarters thereafter. While the market seems to want to go on a ride with Apple on its ups and downs, my fundamental story for Apple has barely shifted in the last few years and my valuations reflect that story stability.

Download spreadsheet with valuationJust as my valuation looked too optimistic a year, when the earnings report contained darker news, it may seem too pessimistic this year, after a much sunnier report. That said, it is worth emphasizing how much Apple is on the iPhone roller coaster ride, reporting better earnings in the quarters immediately after a new iPhone is released and much worse earnings in the quarters thereafter. While the market seems to want to go on a ride with Apple on its ups and downs, my fundamental story for Apple has barely shifted in the last few years and my valuations reflect that story stability.

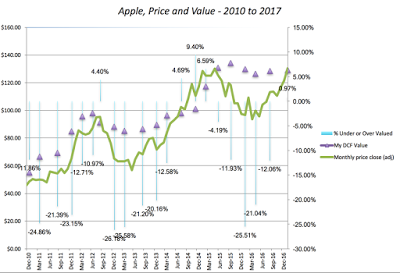

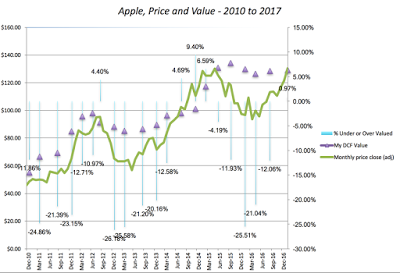

Apple's Price/Value DynamicsI have taken my share of punishment on investments that have not gone well, with Valeant being a source of continuing pain (which I will return to after its next earnings report). Apple, though, has served me well in the last decade, but even with Apple, I have had extended periods where my faith has been tested. The picture below graphs Apple's stock price from 2010 and 2017 with my valuations shown across time:

I held Apple from 2010 to 2012, as it traded under my estimated value. I sold in April 2012, just before a brief interlude where the price popped above value in June 2012, it reverted back to being under valued until June 2014. After spending a few months as an overvalued stock, the price plummeted in the late summer of 2015, making me a buyer, but it continued to drop until almost April 2016. It's been a good ride since, and much as I want to attribute this to my valuation insights and brilliant timing, I have a sneaking suspicion that luck had just as much or perhaps more to do with it. Now that the stock is fully valued, decision time is fast approaching and I am ready with my sell trigger at $140/share, the outer end of the range that I have for Apple's value today.

ConclusionApple is the greatest corporate cash machine in history and it is fully deserving of its market value. Its history as a disruptive force has led some investors to expect Apple to continue what it did a decade ago and come up with new products for new markets. Those expectations, though, don't factor in the reality that as a much larger player with huge profit margins, Apple is more likely to be disrupted than be disruptor. Until investors learn to live with the company, as it exists now and not the company that they wish would exist in its place, there will continue to be mood swings in the market translating into the ebbs and flows of its stock price, and I hope to take advantage of them.

YouTube

My book

Narrative and Numbers (Columbia University Press)

Prior Blog Posts on Apple

Narrative Resets: Revisiting a Tech Trio (August 2015)Race to the top: The Duel between Apple and Alphabet (February 2016)Apple: FCFE, Dividends and Cash Build up - 1988-2016Apple: Valuation in February 2017

The Cash Machine Revs upIn my last post on dividend payout and cash return globally, I noted that large cash balances don't happen by accident but are a direct result of companies paying out less than they have available as potential dividends or free cash flows to equity, year after year. Since Apple's cash balance almost reached $250 billion in its most recent quarterly report, by far the largest cash balance ever accumulated by a publicly traded company, I decided that the place to start was by looking at how it got to its current level. I started by collecting the operating, debt financing and reinvestment cash flows each year from 2007 to 2016 and computing a free cash flow to equity (or potential dividend) each year.

Starting in 2013, when Apple started to tap into its debt capacity, the company has been able to add to its potential dividends each year. In 2015 alone, Apple generated $93.6 billion in FCFE or potential dividends, an astounding amount, larger that the GDP of half the countries in the world in 2015. Each year, I also looked at how much Apple has returned to stockholders in the form of dividends and stock buybacks.

Starting in 2013, when Apple started to tap into its debt capacity, the company has been able to add to its potential dividends each year. In 2015 alone, Apple generated $93.6 billion in FCFE or potential dividends, an astounding amount, larger that the GDP of half the countries in the world in 2015. Each year, I also looked at how much Apple has returned to stockholders in the form of dividends and stock buybacks. Note that while Apple took a while to start returning cash, and it needed prompting from David Einhorn and Carl Icahn, it not only initiated dividends in 2012 but has supplemented those dividends with stock buybacks of increasing magnitude each year. In fact, Apple returned $183 billion in cash to stockholders in the last five years, making it, by far, the largest cash-returner in the world over that period.

Note that while Apple took a while to start returning cash, and it needed prompting from David Einhorn and Carl Icahn, it not only initiated dividends in 2012 but has supplemented those dividends with stock buybacks of increasing magnitude each year. In fact, Apple returned $183 billion in cash to stockholders in the last five years, making it, by far, the largest cash-returner in the world over that period.There are two amazing (at least to me) aspects to this story. The first is that in spite of the immense amounts of cash that Apple has returned each year, its cash balance has increased each year, partly because its operating cash flows are so high and partly because they are being supplemented by debt payments. You can see the cash build up between 2007 and 2016 in the chart below:

Note that while Apple was returning $183 billion in cash between 2013-2016, its cash balance continued to increase, as its cash inflows increased even more. If having a cash spigot that never turns off is a problem, Apple has it, but I am sure that it will not get about as much sympathy from the rest of the world as a supermodel who complains that she cannot put on weight, no matter how much she eats. The other equally surprising feature of this story is that Apple's managers have not felt the urge (yet) to use their huge cash reserves to buy a company, a whole set of companies or even an entire country, a fact that those who like Apple will attribute to the discipline of its management and Apple haters will argue is due to a lack of imagination.

My Apple Valuation HistoryAs many of you who have been reading this blog are aware, I have valued Apple many times before but rather than rehash old history, let me summarize. For Apple, the story that I have been telling about the company for the last five years has been remarkably unchanged. In my July 2012 valuation, where I looked at Apple just after it had become the largest market cap company in the world and had come off perhaps the greatest decade of disruption of any company in history (iTunes, iPod, iPhone and iPad), I concluded that while Apple was one of the great cash machines of all time, its days of disruption were behind it, partly because Steve Jobs was no longer at the helm but mostly because of its size; it is so much more difficult for a $600 billion company to create a significant enough disruption to change the trend lines on earnings, cash flows and value.

So, in my story, I saw Apple continuing to produce cash flows, with low revenue growth and gradually decreasing margins, as the smartphone business became more competitive. I won't make you read all of the posts that I have on Apple, but let me start with a post that I had in August 2015, when I updated the Apple story (and looked at Facebook and Twitter at the same time). The value I estimated for Apple in that post was $130, higher than the stock price of $110 at the time, prompting me to buy the stock. I revisited the story after an earnings report from Apple in February 2016 and compared it to Alphabet. At the time, I valued Apple at about $126 per share, well above the $94/share that it was trading at the time. In May 2016, Carl Icahn, a long time bull on Apple sold his shares, and Warren Buffett, a long time avoider of tech companies, bought shares in the company. In a Apple's Earnings Report & My NarrativeLast week, Apple released its latest 10Q and in conjunction with its latest 10K (Apple's fiscal year end is in September). It contained a modicum of good news, insofar as there was growth in revenues as opposed to the decline posted in the prior quarter and still-solid profit margins, but the revenue growth was only 3% and the margins are still lower than they used to be. Using the numbers in the most recent report, I took at look at my Apple story and guess what? It looks just like it did last year, a great cash machine, with very slow-growing revenues and declining margins. Using the process that I describe, perhaps in too much detail in my book on narrative and numbers, I converted my story in inputs to my valuation:

Some of you may find my story too cramped , seeing a greater possibility than I do of Apple breaking through into a new, big market (with Apple Pay or the Apple iCar). If you are in that group, please take my structure and make it yours, with a higher growth rate coming from your disruptive story, accompanied by lower margins and higher reinvestment. Others may find this story too optimistic, perhaps seeing a more precipitous fall of profit margins in the smart phone business and a greater tax liability from trapped cash. You too can alter the inputs to your liking and make your own judgment on Apple!

An Updated Valuation of AppleOnce you have a story for a company and convert that story into valuation inputs, the rest of the process becomes just mechanics. In the picture below, I have my February 2017 valuation of Apple.

Download spreadsheet with valuationJust as my valuation looked too optimistic a year, when the earnings report contained darker news, it may seem too pessimistic this year, after a much sunnier report. That said, it is worth emphasizing how much Apple is on the iPhone roller coaster ride, reporting better earnings in the quarters immediately after a new iPhone is released and much worse earnings in the quarters thereafter. While the market seems to want to go on a ride with Apple on its ups and downs, my fundamental story for Apple has barely shifted in the last few years and my valuations reflect that story stability.

Download spreadsheet with valuationJust as my valuation looked too optimistic a year, when the earnings report contained darker news, it may seem too pessimistic this year, after a much sunnier report. That said, it is worth emphasizing how much Apple is on the iPhone roller coaster ride, reporting better earnings in the quarters immediately after a new iPhone is released and much worse earnings in the quarters thereafter. While the market seems to want to go on a ride with Apple on its ups and downs, my fundamental story for Apple has barely shifted in the last few years and my valuations reflect that story stability.Apple's Price/Value DynamicsI have taken my share of punishment on investments that have not gone well, with Valeant being a source of continuing pain (which I will return to after its next earnings report). Apple, though, has served me well in the last decade, but even with Apple, I have had extended periods where my faith has been tested. The picture below graphs Apple's stock price from 2010 and 2017 with my valuations shown across time:

I held Apple from 2010 to 2012, as it traded under my estimated value. I sold in April 2012, just before a brief interlude where the price popped above value in June 2012, it reverted back to being under valued until June 2014. After spending a few months as an overvalued stock, the price plummeted in the late summer of 2015, making me a buyer, but it continued to drop until almost April 2016. It's been a good ride since, and much as I want to attribute this to my valuation insights and brilliant timing, I have a sneaking suspicion that luck had just as much or perhaps more to do with it. Now that the stock is fully valued, decision time is fast approaching and I am ready with my sell trigger at $140/share, the outer end of the range that I have for Apple's value today.

ConclusionApple is the greatest corporate cash machine in history and it is fully deserving of its market value. Its history as a disruptive force has led some investors to expect Apple to continue what it did a decade ago and come up with new products for new markets. Those expectations, though, don't factor in the reality that as a much larger player with huge profit margins, Apple is more likely to be disrupted than be disruptor. Until investors learn to live with the company, as it exists now and not the company that they wish would exist in its place, there will continue to be mood swings in the market translating into the ebbs and flows of its stock price, and I hope to take advantage of them.

YouTube

My book

Narrative and Numbers (Columbia University Press)

Prior Blog Posts on Apple

Narrative Resets: Revisiting a Tech Trio (August 2015)Race to the top: The Duel between Apple and Alphabet (February 2016)Apple: FCFE, Dividends and Cash Build up - 1988-2016Apple: Valuation in February 2017

Published on February 09, 2017 08:57

February 6, 2017

January 2017 Data Update 9: Dividends and Buybacks

If you are from my generation, I am sure that you remember Rodney Dangerfield, whose comedy routine was built around the fact that "he got no respect". This post is about dividends and cash return, the Rodney Dangerfield of Corporate finance, a decision that gets no respect and very little serious attention from either academics or practitioners. In many companies, the decision of how much to pay on dividends is made either on auto pilot or on a me-too basis, which is surprising, since just as a farmer’s payoff from planting crops comes from the harvest, an investor’s payoff from investing should come from cash flows being returned. The investment decisions get the glory, the financing decisions get in the news but the dividend decisions are what complete the cycle.

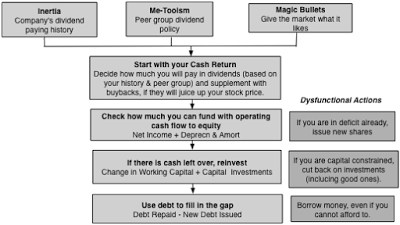

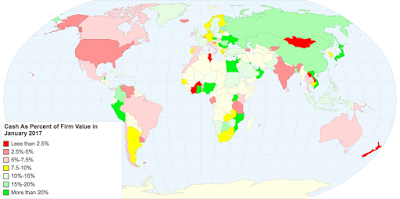

The Dividend Decision

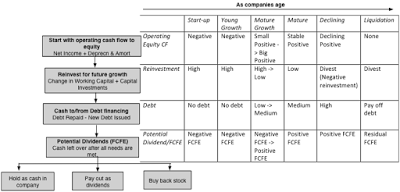

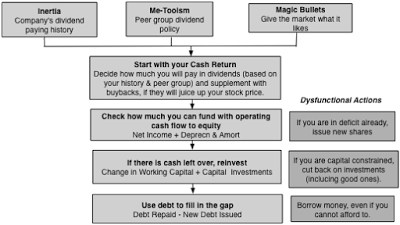

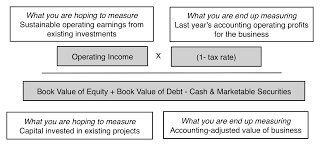

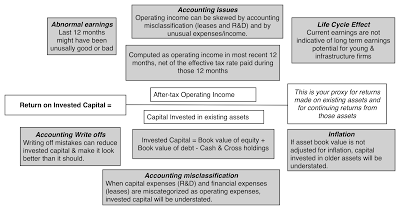

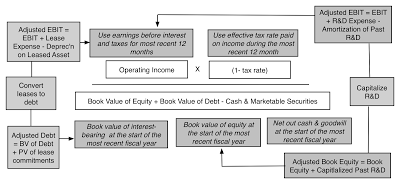

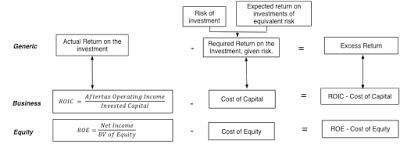

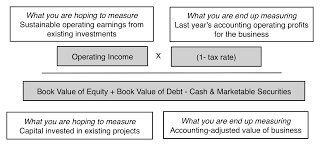

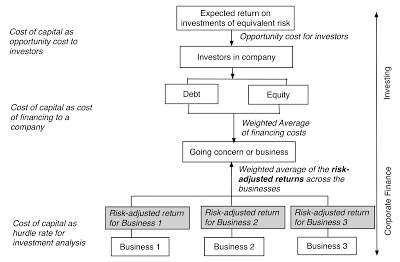

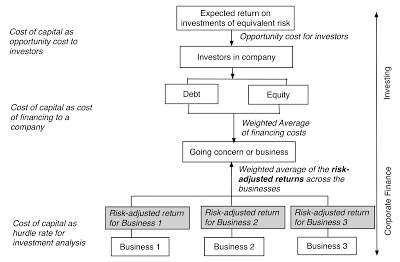

The decision of whether to return cash to the owners of a business and if yes, in what form, is the dividend decision. Since these cash flows are to equity investors, who are the residual claim holders in a business, logically, the dividend decision should be determined by and come after the investment and financing decisions made by a business. The picture below captures how dividends would be set, if they were truly residual cash flows:

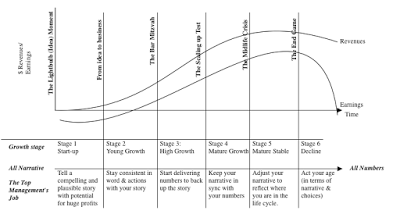

The process, which mirrors what you see in a statement of cash flows, starts with the cash flow to equity from operations, computed by adding back non-cash charges (depreciation and amortization) to net income. From that cash flow, the firm decides how much to reinvest in short term assets (working capital) and long term assets (capital expenditures), supplementing these cash flows with debt issuances and depleting them with debt repayments. If there is any cash flow left over after these actions, and there is not guarantee that there will be, that cash flow is my estimate of potential dividend or if you prefer a buzzier word, the free cash flow to equity. With this free cash flow to equity, the firm can do one of three things: hold the cash (increasing its cash balance), pay a dividend or buy back stock. To the right of the picture, I use a structure that I find useful in corporate finance, which is the corporate life cycle, to illustrate how these numbers change as a company ages.

Early in a company’s life, the operating cash flows are often negative (as the company lose money) and the hole gets deeper as the company has to reinvest to generate future growth and is unable to borrow money. Since the potential dividends (FCFE) are big negative numbers, the company will be raising new equity rather than returning cash. As the company starts to grow, the earnings first turn positive but the large reinvestment needs to sustain future growth will continue to keep potential dividends negative, thus justifying a no-cash return policy still. As the company matures, there will be two developments: the operating cash flows to equity will start exceeding reinvestment needs and the company’s capacity to borrow money will open up. While the initial response of the company to these developments will be denial (about no longer being growth companies), you cannot hide from the truth. The cash balance will mount and the company’s capacity to borrow money will be increasingly obvious and pressure will build on it to return some of its cash and borrow money. Even the most resistant firms will eventually capitulate and they will enter the period of plentiful cash returns, with large dividends supplemented by stock buybacks, at least partially funded by debt. Finally, you arrive at that most depressing phase of the corporate life cycle, decline, when reinvestment is replaced with divestitures (shrinking the firm and increasing free cash flows to equity) and the cash return swells. The company, in a sense, is partially liquidating itself over time.The truth is that there are companies where the decision on how much to pay in dividends in not the final one but the one made first. Put differently, rather than making investment and financing decisions first, based upon what works best for the firm, and paying the residual cash flow as dividends, firms make their dividend decisions (and I include buybacks in dividends) first and then modify their financing and investing decisions, given the dividends.

The companies that follow this backward sequence, and there are a lot of them, can easily end up with severely dysfunctional dividend policies that can destroy them, unless good sense prevails. It is an attitude that was best captured by Andrew Mackenzie, CEO of BHP Billiton, who when analysts asked him in 2015 whether he planned to cut dividends, as commodity prices plummeted and earnings dropped, responded by saying "over my dead body".

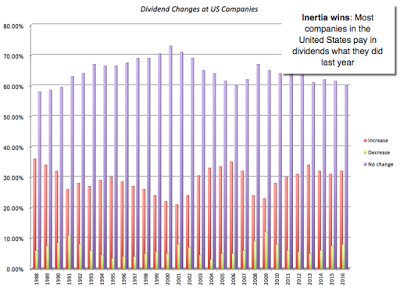

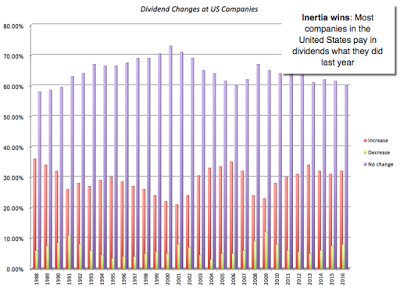

Dividends, Cash Return and Potential Dividends: The US HistoryLet’s start with some history on dividends, using the US market. In the graph below, I start by providing the basis for my inertia theory of dividends by looking at the proportion of US firms each year that increase dividends, decrease dividends and leave dividends unchanged:

In every year, since 1988, far more firms left dividends untouched than increased or decreased them, and when dividends did get changed, they were far more likely to be increased than decreased.

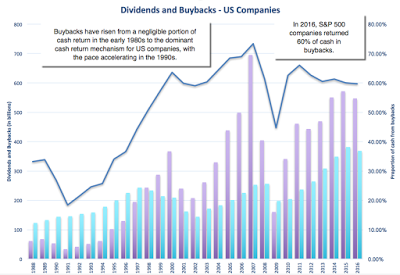

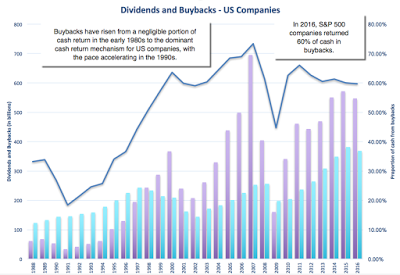

Let’s follow with another fact about US companies. Increasingly, they are replacing dividends, the time-tested way of returning cash to stockholders, with stock buybacks, as you can see in the figure below, where I graph dividends and stock buybacks from the S&P 500 companies from 1988 to 2016.

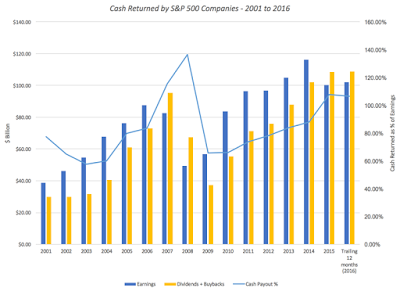

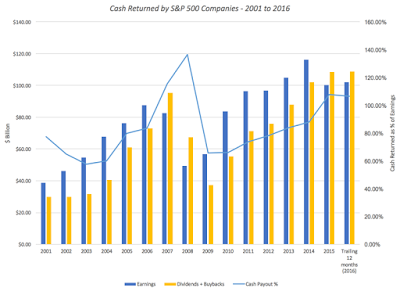

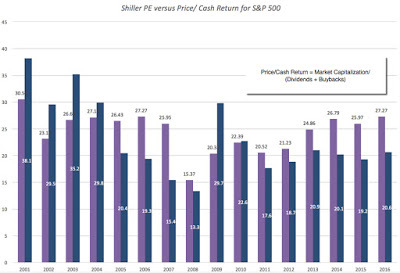

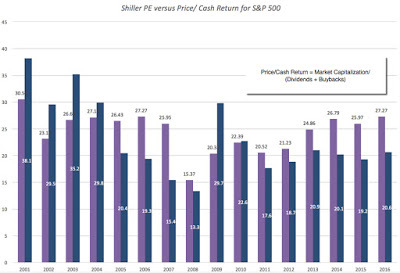

The shift is remarkable. In 1988, almost 70% of all cash returned to stockholders took the form of dividends and by 2016, close to 60% of all cash returned took the form of buybacks. I have written about why this shift has occurred in this post and also why much of the breast beating you hear about how buybacks represent the end of the economy is misdirected. That said, the amount of cash that US companies are returning to stockholders is unsustainable, given the earnings and expectations of growth. In the figure below, I look at for the S&P 500, the cash returned to investors as a proportion of earnings each year from 2001 to 2016:

In 2015 and 2016, the companies in the S&P 500 returned more than 100% of earnings to investors. It is the reason that I highlighted the possibility of a pull back on cash flows as on the stock market’s biggest vulnerabilities this year in my post on US equities.

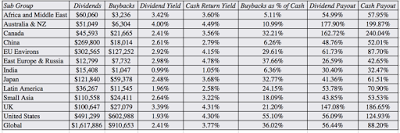

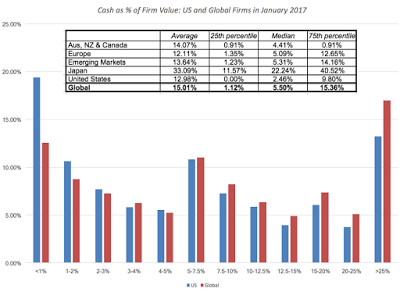

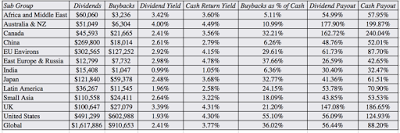

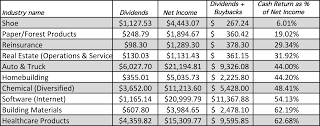

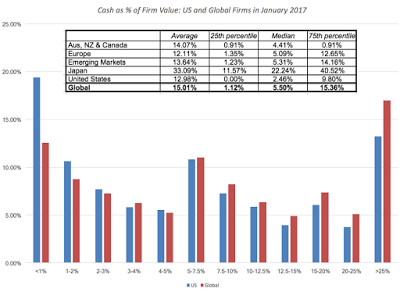

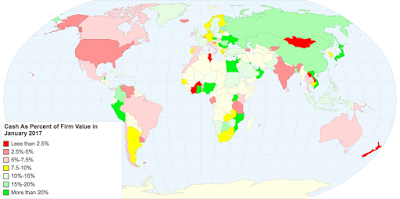

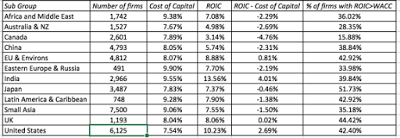

Cash Return: A Global ComparisonHaving looked at US companies, let’s turn the focus to the rest of the world. The stickiness of dividends that we see in the United States is a global phenomenon, though it takes different forms in some parts of the world; in Latin America, for instance, it is payout ratios, not absolute dividends, that companies try to maintain. To provide a measure of cash returned, I report on three statistics: table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

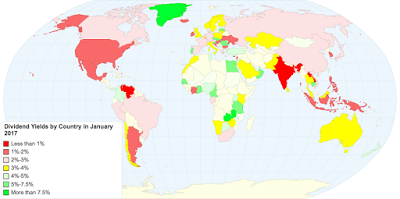

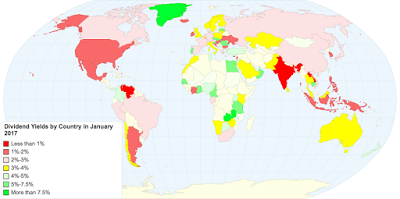

Cash Return StatisticDefinitionWhat it measuresDividend YieldDividends/Market CapPortion of equity return that comes from dividends.Dividend PayoutDividends/Net Income (if net income is positive, NA if negative)Proportion of earnings held back by the company for reinvestment or as cash balance.Cash Return/FCFE(Dividends + Buybacks)/FCFE (if FCFE is positive, NA if negative)Percentage of potential dividends returned to stockholders. Remaining goes into cash balance.The picture below looks at these dividend yields and payout ratios across the globe:

Link to live mapUnlike investment and debt policy, it is difficult to determine what number here would be the “best” number to see. Clearly, over time, you would like companies to return residual cash to stockholders but prudent companies, facing difficult business times, should try to hold back some cash as a buffer. Returning too little cash (low payout ratios) for long periods, though, is indicative of an absence of stockholder power and a sign that managers/insiders are building cash empires. Returning too much cash can mean less cash available for good projects and/or increasing debt ratios. In the table below, you can see the statistics broken down by region:

Link to live mapUnlike investment and debt policy, it is difficult to determine what number here would be the “best” number to see. Clearly, over time, you would like companies to return residual cash to stockholders but prudent companies, facing difficult business times, should try to hold back some cash as a buffer. Returning too little cash (low payout ratios) for long periods, though, is indicative of an absence of stockholder power and a sign that managers/insiders are building cash empires. Returning too much cash can mean less cash available for good projects and/or increasing debt ratios. In the table below, you can see the statistics broken down by region:

Link to full country spreadsheetLet's take a look at the numbers in this table. The shift towards buybacks which has been so drastic in the United States seems to be wending its way globally. While there are markets like India, where buybacks are still uncommon (comprising only 6.36% of total cash returned), almost 30% of cash returned in Europe and 33% of cash returned in Japan took the form of buybacks. In Canada and Australia, companies returned over 150% of potential dividends to investors, perhaps because natural resource companies are hotbeds of dysfunctional dividend policy, with top managers maintaining dividends even in the face of sustained declines in commodity prices (and corporate earnings). The Mackenzie "over my dead body" dividend policy is live and well at many of other natural resource companies. With buybacks counted in, you see cash return rising above 100% for the US as well, backing up the point made earlier about unsustainable dividends.

Link to full country spreadsheetLet's take a look at the numbers in this table. The shift towards buybacks which has been so drastic in the United States seems to be wending its way globally. While there are markets like India, where buybacks are still uncommon (comprising only 6.36% of total cash returned), almost 30% of cash returned in Europe and 33% of cash returned in Japan took the form of buybacks. In Canada and Australia, companies returned over 150% of potential dividends to investors, perhaps because natural resource companies are hotbeds of dysfunctional dividend policy, with top managers maintaining dividends even in the face of sustained declines in commodity prices (and corporate earnings). The Mackenzie "over my dead body" dividend policy is live and well at many of other natural resource companies. With buybacks counted in, you see cash return rising above 100% for the US as well, backing up the point made earlier about unsustainable dividends.

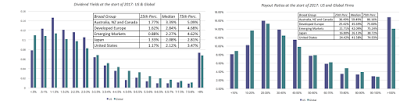

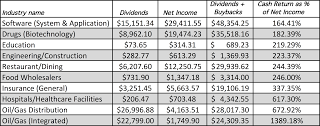

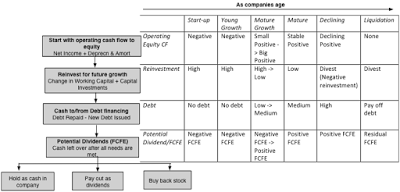

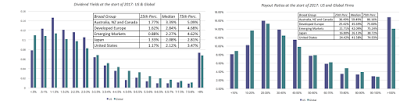

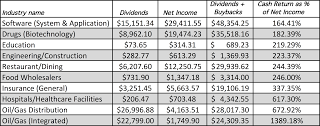

Cash Return: A Company and Sector ComparisonDividend policy varies across firms, the result of not only financial factors (where the company is in its life cycle, what type of business it is in and how investors get taxed) but also emotional ones (how risk averse managers are and how much they value control). As a result dividend yields and payout ratios vary widely across companies, and the picture below captures the distribution of both statistics across US and global companies: There are wide variations in cash return across sectors, some reflecting where they stand in the life cycle and some just a function of history. In the table below, I highlight the sectors that returned the most cash, as a percent of net income, in the table below:

There are wide variations in cash return across sectors, some reflecting where they stand in the life cycle and some just a function of history. In the table below, I highlight the sectors that returned the most cash, as a percent of net income, in the table below:

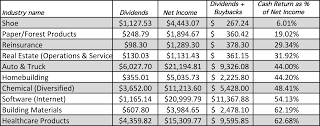

It is difficult to see a common theme here. You can see the residue of sticky dividends and inertia in the high cash return at oil and gas companies, perhaps still struggling to adapt to lower oil prices. There are surprises, with application software and biotech firms making the list. Looking at the sectors that returned the least cash, here is the list of the top ten:

If the cash that companies can return increases as they age, you should see the cash return policies change over time for sectors. Many of the technology firms that were high growth in the 1980s are now ageing and they are returning large amounts of cash to their stockholders; Apple, IBM and Microsoft are at the top of the list of companies that have bought back the most stock in the last decade.