Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 15

December 19, 2019

A Teaching Manifesto: An Invitation to my Spring 2020 classes

If you have been reading my blog for long enough, you should have seen this post coming. Every semester that I teach, and it has only been in the spring in the last few years, I issue an invitation to anyone interested to attend my classes online. While I cannot offer you credit for taking the class or much direct personal help, you can watch my sessions online (albeit not live), review the slides that I use and access the post class material, and it is free. If you are interested in a certificate version of the class, NYU offers that option, but it does so for a fee. You can decide what works for you, and whatever your decision is, I hope that you enjoy the material and learn from it, in that order.

The Structure

I will be teaching three classes in Spring 2020 at the Stern School of Business (NYU), a corporate finance class to the MBAs and two identical valuation classes, one to the MBAs and one for undergraduates. If you decide to take one of the MBA classes, the first session will be on February 3, 2020, and there will be classes every Monday and Wednesday until May 11, 2020, with the week of March 15-22 being spring break. In total, there will be 26 sessions, each session lasting 80 minutes. The undergraduate classes start a week earlier, on January 27, and go through May 11, comprising 28 sessions of 75 minutes apiece. The Spring 2020 Classses: With all three classes, the sessions will be recorded and converted into streams, accessible on my website and downloadable, as well as YouTube videos, with each class having its own playlist. In addition, the classes will also be carried on iTunes U, with material and slides, accessible from the site. The session videos will usually be accessible about 3-4 hours after class is done and you can either take the class in real time, watching the sessions in the week that they are taught, or in bunches, when you have the time to spend to watch the sessions; the recordings will stay online for at least a couple of years after the class ends. There will be no need for passwords, since the session videos will be unprotected on all of the platforms. The (Free) Online Version: During the two decades that I have been offering this online option, I have noticed that many people who start the class with the intent of finishing it give up for one of two reasons. The first is that watching an 80-minute video on a TV or tablet is a lot more difficult than watching it live in class, straining both your patience and your attention. The second is that watching these full-length videos is a huge time commitment and life gets in the way. It is to counter these problems that I created 12-15 minute versions of the each session for online versions of the classes. These online classes, recorded in 2014 and 2015, is also available on my website and through YouTube, and should perhaps be more doable than the full class version.The NYU Certificate Version: For most of the last 20 years, I have been asked why I don’t offer certificates of completion for my own classes and I have had three answers. The first is that, as a solo act, I don’t have the bandwidth to grade and certify the 20,000 people who take the classes each semester. The second is that certification requires regulatory permission, a bureaucratic process in New York State that I have neither the stomach nor the inclination to go through. The third is, and it is perhaps the most critical, is that I am lazy and I really don't want to add this to my to-do list. One solution would be to offer the classes through platforms like Coursera, but those platforms work with universities, not individual faculty, and NYU has no agreements with any of these platforms. About three years ago, when NYU approached me with a request to create online certificate classes, I agreed, with one condition: that the free online versions of these classes would continue to be offered. With those terms agreed to, there are now NYU Certificate versions of each of the online classes, with much of the same content, but with four add ons. First, each participant will have to take quizzes and a final exam, multiple choice and auto-graded, that will be scored and recorded. Second, each participant will have to complete and turn in a real-world project, showing that they can apply the principles of the class on a company of their choice, to be graded by me. Third, I will have live Zoom sessions every other week for class participants, where you can join and ask questions about the material. Finally, at the end of the class, assuming that the scores on the exams and project meet thresholds, you will get a certificate, if you pass the class, or a certificate with honors, if you pass it with flying colors. The Classes I have absolutely no desire to waste your time and your energy by trying to get you to take classes that you either have no interest in, or feel will serve no good purpose for you. In this section, I will provide a short description of each class, and provide links to the different options for taking each class.

I. Corporate Finance

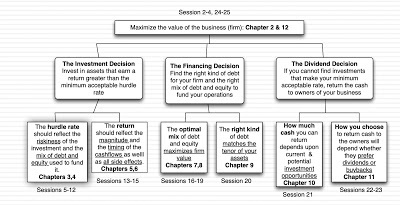

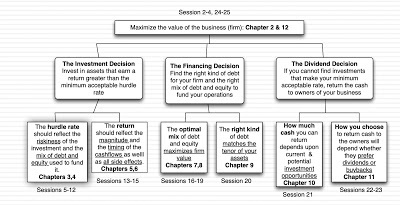

Class description : I don’t like to play favorites, but corporate finance is my favorite class, a big picture class about the first principles of finance that govern how to run a business. I will not be egotistical enough to claim that you cannot run a business without taking this class, since there are many incredibly successful business-people who do, but I do believe that you cannot run a business without paying heed to the first principles. I teach this class as a narrative, staring with the question of what the objective of a business should be and then using that objective to determine how best to allocate and invest scarce resources (the investment decision), how to fund the business (the financing decision) and how much cash to take out and how much to leave in the business (the dividend decision). I end the class, by looking at how all of these decisions are connected to value.

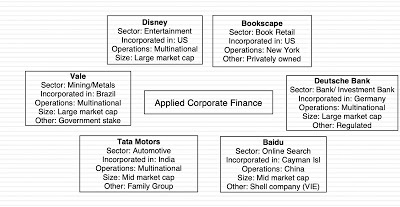

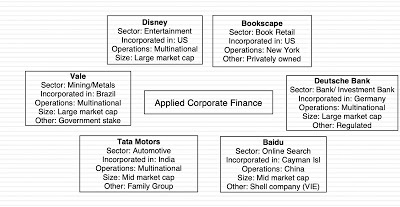

Chapters: Applied Corporate Finance Book, Sessions: Class sessionI am not a believer in theory, for the sake of theory, and everything that we do in this class will be applied to real companies, and I will use six companies (Disney, Vale, Tata Motors, Deutsche Bank, Baidu and a small private bookstore called Bookscape) as lab experiements that run through the entire class.

Chapters: Applied Corporate Finance Book, Sessions: Class sessionI am not a believer in theory, for the sake of theory, and everything that we do in this class will be applied to real companies, and I will use six companies (Disney, Vale, Tata Motors, Deutsche Bank, Baidu and a small private bookstore called Bookscape) as lab experiements that run through the entire class.

I say, only half-jokingly, that everything in business is corporate finance, from the question of whether shareholder or stakeholder interests should have top billing at companies, to why companies borrow money and whether the shift to stock buybacks that we are seeing at US companies is good or bad for the economy. Since each of these questions has a political component, and have now entered the political domain, I am sure that the upcoming presidential election in the US will create some heat, if not light, around how they are answered.

For whom?

As I admitted up front, I believe that having a solid corporate finance perspective can be helpful to everyone. I have taught this class to diverse groups, from CEOs to banking analysts, from VCs to startup founders, from high schoolers to senior citizens, and while the content does not change, what people take away from the class is different. For bankers and analysts, it may be the tools and techniques that have the most staying power, whereas for strategists and founders, it is the big picture that sticks. So, in the words of the old English calling, "Come ye, come all", take what you find useful, abandon what you don't and have fun while you do this.

Links to Offerings

1. Spring 2020 Corporate Finance MBA class (Free)Webpage for the classMy website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U class (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of FLJ-MLN-XZL)2. Online Corporate Finance Class (Free)

My website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U class (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of HAS-CCR-FRA)3. NYU Certificate Class on Corporate Finance (It will cost you...)

NYU Entry Page II. Valuation

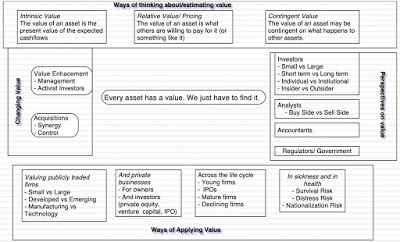

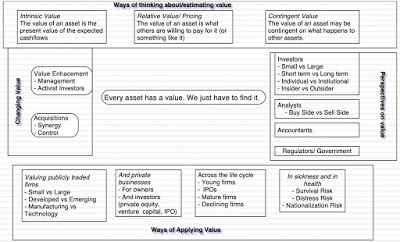

Class description: Some time in the last decade, I was tagged as the Dean of Valuation, and I still cringe when I hear those words for two reasons. First, it suggests that valuation is a deep and complex subject that requires intense study to get good at. Second, it also suggests that I somehow have mastered the topic. If nothing else, this class that I first taught in 1987 at NYU, and have taught pretty much every year since, dispenses with both delusions. I emphasize that valuation, at its core, is simple and that practitioner, academics and analysts often choose to make it complex, sometimes to make their services seem indispensable, and sometimes because they lose the forest for the trees. Second, I describe valuation as a craft that you learn by doing, not by reading or watching other people talk about it, and that I am still working on the craft. In fact, the more I learn, the more I realize that I have more work to do. This is a class about valuing just about anything, from an infrastructure project to a small private business to a multinational conglomerate, and it also looks at value from different perspectives, from that of a passive investor seeking to buy a stake or shares in a company to a PE or VC investor taking a larger stake to an acquirer interested in buying the whole company.

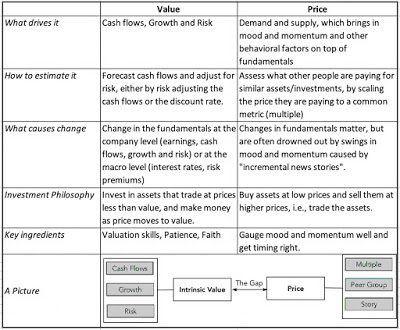

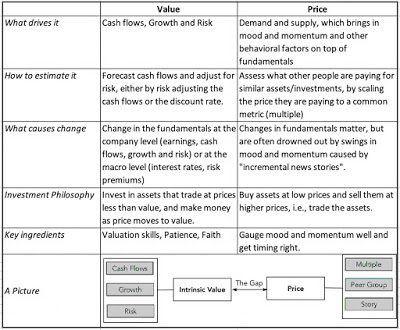

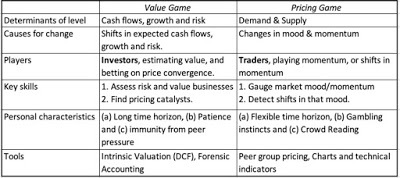

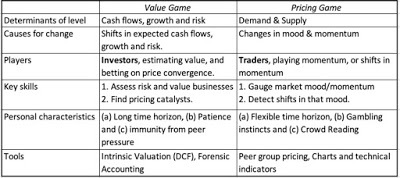

Finally, I lay out my rationale for differentiating between value and price, and why pricing an asset can give you a very different number than valuing that asset, and why much of what passes for valuation in the real world is really pricing.

Along the way, I emphasize how little has changed in valuation over the centuries, even as we get access to more data and more complex models, while also bringing in new tools that have enriched us, from option pricing models to value real options (young biotech companies, natural resource firms) to statistical add-ons (decision trees, Monte Carlo simulations, regressions).

For whom?

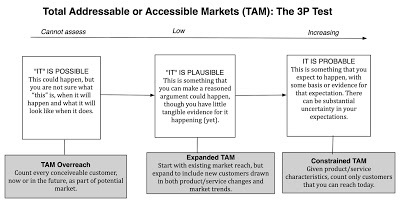

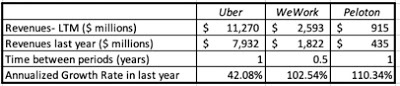

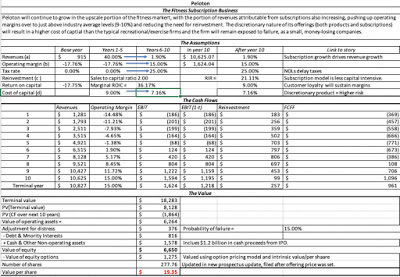

Do you need to be able to do valuation to live a happy and fulfilling life? Of course not, but it is a skill worth having as a business owner, consultant, investor or just bystander. With that broad audience in mind, I don't teach this class to prepare people for equity research or financial analysis jobs, but to get a handle on what it is that drives value, in general, and how to detect BS, often spouted in its context. Don't get me wrong! I want you to be able to value or price just about anything by the end of this class, from Bitcoin to WeWork, but don't take yourself too seriously, as you do so.

Links to Offerings 1a. Spring 2020 Valuation MBA class (Free)Webpage for the classMy website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U class (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of FSN-WWJ-RAH)1b. Spring 2020 Valuation Undergraduate class (Free)Webpage for the classMy website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U class (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of ENT-ZXA-JYL)2. Online Valuation Class (Free)My website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U class (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of K7X-VD9-5KE)3. NYU Certificate Class on Valuation (Paid)

NYU Entry Page III. Investment Philosophies

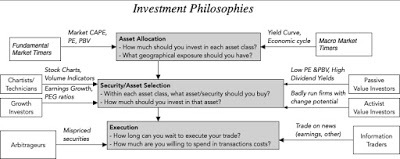

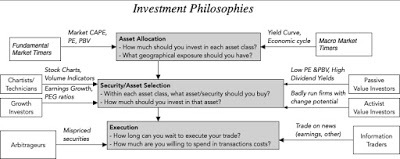

Class description: This is my orphan class, a class that I have had the material to teach but never taught in a regular classroom. It had its origins in an couple of observations that puzzled me. The first was that, if you look at the pantheon of successful investors over time, it is not only a short one, but a diverse grouping, including those from the old time value school (Ben Graham, Warren Buffett), growth success stories (Peter Lynch and VC), macro and market timers (George Soros), quant players (Jim Simon) and even chartists. The second was that the millions who claim to follow these legends, by reading everything ever written by or about them and listening to their advice, don’t seem to replicate their success. That led me to conclude that there could be no one ‘best’ Investment philosophy across all investors but there could be one that is best for you, given your personal makeup and characteristics, and that if you are seeking investment nirvana, the person that you most need to understand is not Buffett or Lynch, but you. In this class, having laid the foundations for understanding risk, transactions cost and market efficiency (and inefficiency), I look at the entire spectrum of investment philosophies, from charting/technical analysis to value investing in all its forms (passive, activist, contrarian) to growth investing (from small cap to venture capital) to market timing. With each one, I look at the core drivers (beliefs and assumptions) of the philosophy, the historical evidence on what works and does not work and end by looking at what an investor needs to bring to the table, to succeed with each one.

I will try (and not always succeed) to keep my biases out of the discussion, but I will also be open about where my search for an investment philosophy has brought me. By the end of the class, it is not my intent to make you follow my path but to help you find your own.

For whom?

This is a class for investors, not portfolio managers or analysts, and since we are all investors in one way or the other, I try to make it general. That said, if your intent is to take a class that will provide easy pathways to making money, or an affirmation of the "best" investment philosophy, this is not the class for you. My objective in this class is not to provide prescriptive advice, but to instead provide a menu of choices, with enough information to help you can make the choice that is best for you. Along the way, you will see how difficult it is to beat the market, why almost every investment strategy that sounds too good to be true is built on sand, and why imitating great investors is not a great way to make money.

Links to Offerings

1. Online Investment Philosophies Class (Free)My website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of J6Z-AD7-NX3)2. NYU Certificate Class on Valuation (Paid)NYU Entry Page (Coming soon)ConclusionI have to confess that I don't subscribe to the ancient Guru/Sishya relationship in teaching, where the Guru (teacher) is an all-knowing individual who imparts his or her fountain of wisdom to a receptive and usually subservient follower. I have always believed that every person who takes my class, no matter how much of a novice in finance, already knows everything that needs to be known about valuation, corporate finance and investments, and it is my job, as a teacher, to make him or her aware of this knowledge. Put simply, I can provide some structure for you to organize what you already know, and tools that may help you put that knowledge into practice, but I am incapable of profundity. I hope that you do give one (or more) of my classes a shot and I hope that you both enjoy the experience and get a chance to try it out on real companies in real time.

YouTube Video

The Structure

I will be teaching three classes in Spring 2020 at the Stern School of Business (NYU), a corporate finance class to the MBAs and two identical valuation classes, one to the MBAs and one for undergraduates. If you decide to take one of the MBA classes, the first session will be on February 3, 2020, and there will be classes every Monday and Wednesday until May 11, 2020, with the week of March 15-22 being spring break. In total, there will be 26 sessions, each session lasting 80 minutes. The undergraduate classes start a week earlier, on January 27, and go through May 11, comprising 28 sessions of 75 minutes apiece. The Spring 2020 Classses: With all three classes, the sessions will be recorded and converted into streams, accessible on my website and downloadable, as well as YouTube videos, with each class having its own playlist. In addition, the classes will also be carried on iTunes U, with material and slides, accessible from the site. The session videos will usually be accessible about 3-4 hours after class is done and you can either take the class in real time, watching the sessions in the week that they are taught, or in bunches, when you have the time to spend to watch the sessions; the recordings will stay online for at least a couple of years after the class ends. There will be no need for passwords, since the session videos will be unprotected on all of the platforms. The (Free) Online Version: During the two decades that I have been offering this online option, I have noticed that many people who start the class with the intent of finishing it give up for one of two reasons. The first is that watching an 80-minute video on a TV or tablet is a lot more difficult than watching it live in class, straining both your patience and your attention. The second is that watching these full-length videos is a huge time commitment and life gets in the way. It is to counter these problems that I created 12-15 minute versions of the each session for online versions of the classes. These online classes, recorded in 2014 and 2015, is also available on my website and through YouTube, and should perhaps be more doable than the full class version.The NYU Certificate Version: For most of the last 20 years, I have been asked why I don’t offer certificates of completion for my own classes and I have had three answers. The first is that, as a solo act, I don’t have the bandwidth to grade and certify the 20,000 people who take the classes each semester. The second is that certification requires regulatory permission, a bureaucratic process in New York State that I have neither the stomach nor the inclination to go through. The third is, and it is perhaps the most critical, is that I am lazy and I really don't want to add this to my to-do list. One solution would be to offer the classes through platforms like Coursera, but those platforms work with universities, not individual faculty, and NYU has no agreements with any of these platforms. About three years ago, when NYU approached me with a request to create online certificate classes, I agreed, with one condition: that the free online versions of these classes would continue to be offered. With those terms agreed to, there are now NYU Certificate versions of each of the online classes, with much of the same content, but with four add ons. First, each participant will have to take quizzes and a final exam, multiple choice and auto-graded, that will be scored and recorded. Second, each participant will have to complete and turn in a real-world project, showing that they can apply the principles of the class on a company of their choice, to be graded by me. Third, I will have live Zoom sessions every other week for class participants, where you can join and ask questions about the material. Finally, at the end of the class, assuming that the scores on the exams and project meet thresholds, you will get a certificate, if you pass the class, or a certificate with honors, if you pass it with flying colors. The Classes I have absolutely no desire to waste your time and your energy by trying to get you to take classes that you either have no interest in, or feel will serve no good purpose for you. In this section, I will provide a short description of each class, and provide links to the different options for taking each class.

I. Corporate Finance

Class description : I don’t like to play favorites, but corporate finance is my favorite class, a big picture class about the first principles of finance that govern how to run a business. I will not be egotistical enough to claim that you cannot run a business without taking this class, since there are many incredibly successful business-people who do, but I do believe that you cannot run a business without paying heed to the first principles. I teach this class as a narrative, staring with the question of what the objective of a business should be and then using that objective to determine how best to allocate and invest scarce resources (the investment decision), how to fund the business (the financing decision) and how much cash to take out and how much to leave in the business (the dividend decision). I end the class, by looking at how all of these decisions are connected to value.

Chapters: Applied Corporate Finance Book, Sessions: Class sessionI am not a believer in theory, for the sake of theory, and everything that we do in this class will be applied to real companies, and I will use six companies (Disney, Vale, Tata Motors, Deutsche Bank, Baidu and a small private bookstore called Bookscape) as lab experiements that run through the entire class.

Chapters: Applied Corporate Finance Book, Sessions: Class sessionI am not a believer in theory, for the sake of theory, and everything that we do in this class will be applied to real companies, and I will use six companies (Disney, Vale, Tata Motors, Deutsche Bank, Baidu and a small private bookstore called Bookscape) as lab experiements that run through the entire class.

I say, only half-jokingly, that everything in business is corporate finance, from the question of whether shareholder or stakeholder interests should have top billing at companies, to why companies borrow money and whether the shift to stock buybacks that we are seeing at US companies is good or bad for the economy. Since each of these questions has a political component, and have now entered the political domain, I am sure that the upcoming presidential election in the US will create some heat, if not light, around how they are answered.

For whom?

As I admitted up front, I believe that having a solid corporate finance perspective can be helpful to everyone. I have taught this class to diverse groups, from CEOs to banking analysts, from VCs to startup founders, from high schoolers to senior citizens, and while the content does not change, what people take away from the class is different. For bankers and analysts, it may be the tools and techniques that have the most staying power, whereas for strategists and founders, it is the big picture that sticks. So, in the words of the old English calling, "Come ye, come all", take what you find useful, abandon what you don't and have fun while you do this.

Links to Offerings

1. Spring 2020 Corporate Finance MBA class (Free)Webpage for the classMy website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U class (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of FLJ-MLN-XZL)2. Online Corporate Finance Class (Free)

My website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U class (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of HAS-CCR-FRA)3. NYU Certificate Class on Corporate Finance (It will cost you...)

NYU Entry Page II. Valuation

Class description: Some time in the last decade, I was tagged as the Dean of Valuation, and I still cringe when I hear those words for two reasons. First, it suggests that valuation is a deep and complex subject that requires intense study to get good at. Second, it also suggests that I somehow have mastered the topic. If nothing else, this class that I first taught in 1987 at NYU, and have taught pretty much every year since, dispenses with both delusions. I emphasize that valuation, at its core, is simple and that practitioner, academics and analysts often choose to make it complex, sometimes to make their services seem indispensable, and sometimes because they lose the forest for the trees. Second, I describe valuation as a craft that you learn by doing, not by reading or watching other people talk about it, and that I am still working on the craft. In fact, the more I learn, the more I realize that I have more work to do. This is a class about valuing just about anything, from an infrastructure project to a small private business to a multinational conglomerate, and it also looks at value from different perspectives, from that of a passive investor seeking to buy a stake or shares in a company to a PE or VC investor taking a larger stake to an acquirer interested in buying the whole company.

Finally, I lay out my rationale for differentiating between value and price, and why pricing an asset can give you a very different number than valuing that asset, and why much of what passes for valuation in the real world is really pricing.

Along the way, I emphasize how little has changed in valuation over the centuries, even as we get access to more data and more complex models, while also bringing in new tools that have enriched us, from option pricing models to value real options (young biotech companies, natural resource firms) to statistical add-ons (decision trees, Monte Carlo simulations, regressions).

For whom?

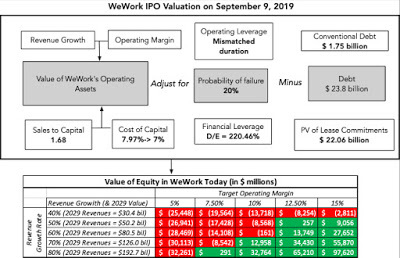

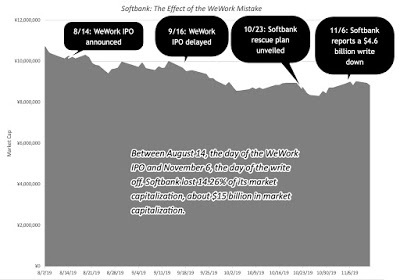

Do you need to be able to do valuation to live a happy and fulfilling life? Of course not, but it is a skill worth having as a business owner, consultant, investor or just bystander. With that broad audience in mind, I don't teach this class to prepare people for equity research or financial analysis jobs, but to get a handle on what it is that drives value, in general, and how to detect BS, often spouted in its context. Don't get me wrong! I want you to be able to value or price just about anything by the end of this class, from Bitcoin to WeWork, but don't take yourself too seriously, as you do so.

Links to Offerings 1a. Spring 2020 Valuation MBA class (Free)Webpage for the classMy website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U class (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of FSN-WWJ-RAH)1b. Spring 2020 Valuation Undergraduate class (Free)Webpage for the classMy website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U class (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of ENT-ZXA-JYL)2. Online Valuation Class (Free)My website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U class (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of K7X-VD9-5KE)3. NYU Certificate Class on Valuation (Paid)

NYU Entry Page III. Investment Philosophies

Class description: This is my orphan class, a class that I have had the material to teach but never taught in a regular classroom. It had its origins in an couple of observations that puzzled me. The first was that, if you look at the pantheon of successful investors over time, it is not only a short one, but a diverse grouping, including those from the old time value school (Ben Graham, Warren Buffett), growth success stories (Peter Lynch and VC), macro and market timers (George Soros), quant players (Jim Simon) and even chartists. The second was that the millions who claim to follow these legends, by reading everything ever written by or about them and listening to their advice, don’t seem to replicate their success. That led me to conclude that there could be no one ‘best’ Investment philosophy across all investors but there could be one that is best for you, given your personal makeup and characteristics, and that if you are seeking investment nirvana, the person that you most need to understand is not Buffett or Lynch, but you. In this class, having laid the foundations for understanding risk, transactions cost and market efficiency (and inefficiency), I look at the entire spectrum of investment philosophies, from charting/technical analysis to value investing in all its forms (passive, activist, contrarian) to growth investing (from small cap to venture capital) to market timing. With each one, I look at the core drivers (beliefs and assumptions) of the philosophy, the historical evidence on what works and does not work and end by looking at what an investor needs to bring to the table, to succeed with each one.

I will try (and not always succeed) to keep my biases out of the discussion, but I will also be open about where my search for an investment philosophy has brought me. By the end of the class, it is not my intent to make you follow my path but to help you find your own.

For whom?

This is a class for investors, not portfolio managers or analysts, and since we are all investors in one way or the other, I try to make it general. That said, if your intent is to take a class that will provide easy pathways to making money, or an affirmation of the "best" investment philosophy, this is not the class for you. My objective in this class is not to provide prescriptive advice, but to instead provide a menu of choices, with enough information to help you can make the choice that is best for you. Along the way, you will see how difficult it is to beat the market, why almost every investment strategy that sounds too good to be true is built on sand, and why imitating great investors is not a great way to make money.

Links to Offerings

1. Online Investment Philosophies Class (Free)My website & streamingYouTube PlaylistiTunes U (Download the iTunes U app and use enroll code of J6Z-AD7-NX3)2. NYU Certificate Class on Valuation (Paid)NYU Entry Page (Coming soon)ConclusionI have to confess that I don't subscribe to the ancient Guru/Sishya relationship in teaching, where the Guru (teacher) is an all-knowing individual who imparts his or her fountain of wisdom to a receptive and usually subservient follower. I have always believed that every person who takes my class, no matter how much of a novice in finance, already knows everything that needs to be known about valuation, corporate finance and investments, and it is my job, as a teacher, to make him or her aware of this knowledge. Put simply, I can provide some structure for you to organize what you already know, and tools that may help you put that knowledge into practice, but I am incapable of profundity. I hope that you do give one (or more) of my classes a shot and I hope that you both enjoy the experience and get a chance to try it out on real companies in real time.

YouTube Video

Published on December 19, 2019 13:30

November 19, 2019

Regime Change and Value: A Follow up Post on Aramco

In my post from a couple of days ago, I valued Aramco at about $1.65 trillion, but I qualified that valuation by noting that this was the value before adjusting for regime change concerns. That comment seems to have been lost in the reading, and it is perhaps because (a) I made it at the end of the valuation and (b) because the adjustment I made for it seemed completely arbitrary, knocking off about 10% off the value. Since this is a issue that is increasingly relevant in a world, where political disruptions seem to be the order of the day in many parts of the world, I thought that a post dedicated to just regime changes and how they affect value might be in order, and Aramco would offer an exceptionally good lab experiment.

Going Concern and Truncation RisksRisk is part and parcel of investing. That said, risk came come from many sources and not all risk is created equal, to investors. In fact, modern finance was born from the insight that for a diversified investor, it is only risk that you cannot diversify away, i.e., macroeconomic risk exposure, that affects value. In this section, I want to examine another stratification of risk into going concern and truncation risk that is talked about much less, but could matter even more to value.

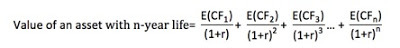

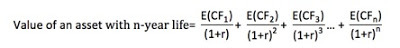

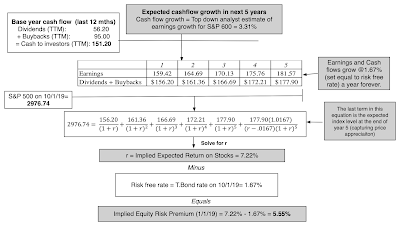

DCF Valuation: A Going Concern Judgment The intrinsic value of a company has always been a function of its expected cash flows, its growth and how risky the cash flows are, but in recent decades a combination of access to data and baby steps in bringing economic models into valuation has resulted in the development of discounted cashflow valuation as a tool to estimate intrinsic value. Put simply, the discounted cash flow value of an asset is:

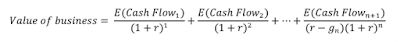

Extended to a publicly traded company, with a potential life in perpetuity, this value can be written as:

If you are a reader of my posts, it should come as no mystery to you that I not only use DCF models to value companies, but that I believe that people under estimate how adaptable it is, usable in valuing everything from start ups to infrastructure projects. There is, however, one significant limitation with DCF models that neither its proponents nor its critics seem be aware of, and it needs to be addressed. Specifically, a DCF is an approach for valuing going concerns, and every aspect of it is built around that presumption. Thus, you estimate expected cash flows each year for the firm, as a going concern, and your discount rate reflects the risk that you see in the company as a going concern. In fact, it is this going concern assumption that allows us to assume that cash flows continue for the long term, sometimes forever, and attach a terminal value to these cash flows.

Truncation Risks If you accept the premise that a DCF is a going concern value, you are probably wondering what other risks there may be in investing that are being missed in a DCF valuation. The risks that I believe are either ignored or incorrectly incorporated into value are truncation risks. The simplest way of illustrating the difference between going concern and truncation risks is by picking a year in your cash flow estimation, say year 3. With going concern risk, you are worried about the actual cash flows in year 3 being different from your expectations, but with truncation risk, you are worried about whether there will be a year 3 for your company.

So, what types of risk will fall into the truncation risk category? Looking at the corporate life cycle, you will see truncation risk become not just significant, but is perhaps the dominant risk that you worry about, age both ends of the life cycle. With start ups and young companies, it is survival risk that is front and center, given that approximately two thirds of start ups never make it to becoming viable businesses. With declining and aging companies, especially laden with debt, it is distress risk, where the company unable to meet its contractual obligations, shutters its doors and liquidates it assets. Looking at political risk, truncation risk can come in many forms, starting with nationalization risk, where a government takes over your business and pays you nothing in some cases and less than fair value in the rest, but extending to other expropriation risks, where you still are allowed to hold equity, but in a much less valuable concern.

Since truncation risk is more the rule than the exception, and it is the dominant risk in some companies, you would think that investors and analysts valuing these companies will have devised sensible ways of incorporating the risk, but you would be wrong.

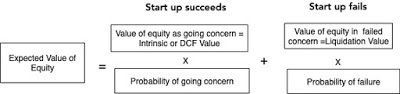

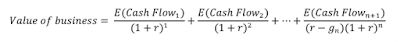

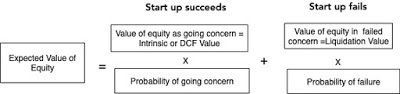

The most common approach to dealing with truncation risk is for analysts to hike up the discount rate, using the alluring argument that if there is more risk, you would demand a higher return. The problem, though, is that this higher discount rate still goes into a DCF where expected cash flows continue in perpetuity, creating an internal contradiction, where you increase the discount rate for truncation risk but you do nothing to the cash flows. In addition, the discount rate that these analysts use are made up, higher just for the sake of being higher, with no rationale for the adjustment. With venture capitalists, this shows up as absurdly high target rates of 40%, 50% or 60%, fiction in a world where these VCs actually deliver returns closer to 15-20%. Discount rates are blunt instruments and are incapable of carrying the burden of truncation risk, and should not be made to do so.Some analysts take the more sensible approach of scenario analysis, allowing for good and bad scenarios (including failure or nationalization) but never close the loop by attaching probabilities to the scenarios. Instead, they leave behind ranges for the value that are so wide as to be useless for decision making purposes. My suggestion is that you use a decision tree approach, where you not only allow for different scenarios, but you make these scenarios cover all possibilities and then attach a probability to each one. In the case of a start up, then, your two possible outcomes will be that the company will make it as a going concern and that it will not, and you will follow through with a DCF, with a going concern discount rate, yielding the value for the going concern outcome, and a liquidation providing your judgment for what the company will be worth, in the failure scenario:

Since you have probabilities for each outcome, you can compute an expected value. If you do this, you should expect to see discount rates for companies prone to failure (young start ups and declining firms) be drawn from the same distribution as that for healthy companies, but the adjustment for failure will be in the post-DCF adjustments. Put more simply, you should see 12-15% as costs of capital for even the riskiest start-ups, in a DCF, never 40-50%, but your post value adjustments for failure and its consequences will still take their toll.

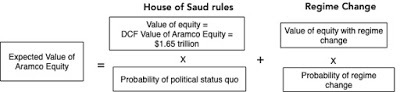

The Aramco Valuation: Bringing in Truncation Risk In my last post, I valued Aramco in a DCF, using three measures of cash flows from dividends to potential dividends to free cash flows to the firm and arrived at values that were surprisingly close to each other, centered around $1.65 trillion, for the equity. Note, though, that these are going concern values, and reflect the expectation that while there may be year to year changes in cash flows, as oil prices changes, management recalibrate and the government tweaks tax and royalty rates, the company will be a going concern and that it will not suffer catastrophic damage to its core asset of low-cost oil reserves. For many investors in Aramco, the prime concern may be less on these fronts and more on whether the House of Saud, as the backer of the promises that Aramco is making its investors, will survive intact for the next few decades.

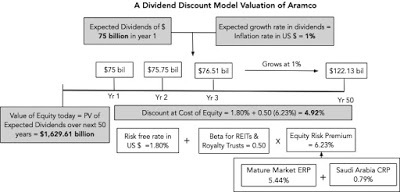

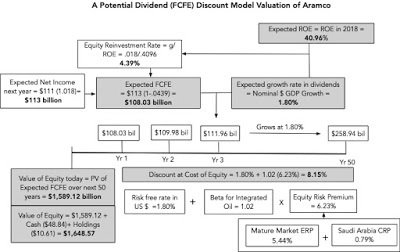

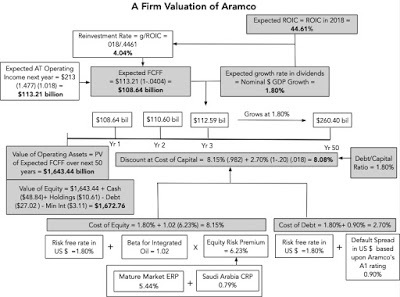

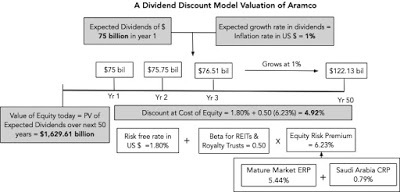

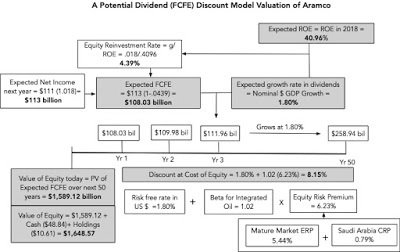

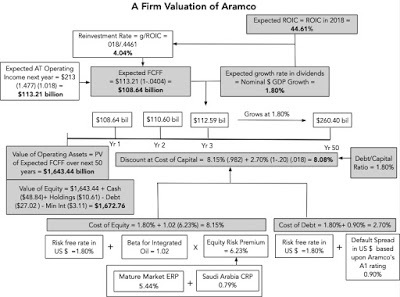

DCF Valuation: Going Concern Risk Reviewing my discounted cash flow valuations of Aramco, you will notice that I began with a risk free rate in US dollars, because my currency choice was that currency. I then adjusted for risk, using a beta for Aramco, based upon REITs/royalty trusts for the promised dividend model and integrated oil companies for the potential dividends/free cash flow models, and an equity risk premium for Saudi Arabia of only 6.23%, with a country risk premium of 0.79% estimated for the country added to the mature market premium estimated for the US. The end result is that I had costs of equity ranging from 4.82% for promised dividends to 8.15% for cash flows.

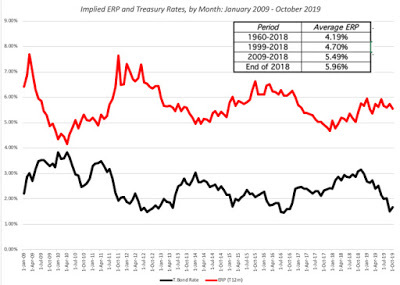

The biggest push back I have had on my valuations is that the cost of equity seems low for a country like Saudi Arabia, and my response is that you are right, if you consider all of the risk in investing in a Saudi equity. However, much of the risk that you are contemplating in Saudi Arabia is political risk, or put more bluntly, the risk of regime change in the country, that could have dramatic effects on value. In fact, if you remove that risk from consideration and look at the remaining risk, Aramco is a remarkably safe investment, with the safety coming from its access to huge oil reserves and mind-boggling profits and cash flows. The DCF values that I have estimated, centered around $1.65 trillion, are therefore values before adjusting for the risk of regime change.

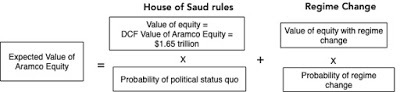

Regime Change Concerns If you invest in Aramco, you clearly have an interests in who rules and runs the country, since every aspect of your valuation is dependent on that assumption. If the House of Saud continues to rule, I believe that the company will be the cash cow that I project it to be in my DCF and the values that I estimated hold. If the Arab spring comes to Riyadh and there is a regime change, the foundations of my value can either crack or be completely swept away, with cash flows, growth and risk all up for re-estimation. In fact, to complete my valuation, I need to bring both the probability of regime change and the consequences into my final valuation:

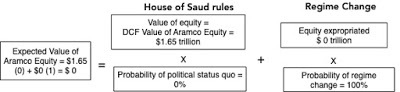

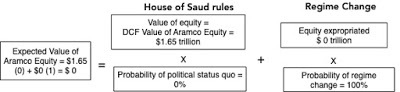

Consider the most extreme case. If you believe that regime change in imminent and certain, and that the change will be extreme (with equity being expropriated and Aramco being brought back entirely into the hands of the state), my expected value for equity becomes zero:

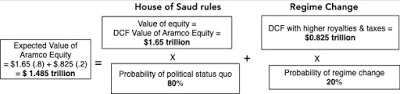

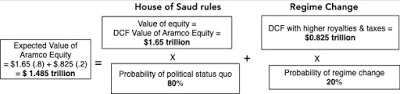

If at the other extreme, you either believe that regime change will never happen, or even if it does, the new regime will not want to hurt the goose that lays the golden eggs and leaves existing terms in place, the value effect of considering regime change will be zero. The truth lies between the extremes, though where it lies is open for debate. I believe that there remains a non-trivial chance (perhaps as high as 20%) that there will be a regime change over the long term and that if there is one, there will be changes that reduce, but not extinguish, my claim, as an equity investor, on the cash flows.

That, in an entirely subjective nutshell, is why I think Aramco's equity value is closer to $1.5 trillion than $1.7 trillion. As with all my other valuations, I understand that your judgments on Aramco will be different from mine, but I think that the disagreements we have are not so much on the going concern estimates of cash flows and risk but on the likelihood and consequences of regime change.

Democracies versus AutocraciesI am not a political scientist, but I have always been fascinated by the question of how political structure and economic value are intertwined. Specifically, would you attach more value to a company or project operating in a democracy or in an autocracy? The approach that I have described in this post to deal with going concern and regime change risk allows me one way of trying too answer the question. Democracies are messy institutions, where governments change and policies morph, because voters change their minds. Put simply, a democracy generally cannot offer any business iron clad guarantees about regulations not changing or tax rates remaining stable, because the government that offers those promises first has to get them approved by legislatures, often can be checked by legal institutions and, most critically, can be voted out of office. Consequently, companies operating in democracies will always complain more about the rules constantly changing, and how those changing rules affect cash flows, growth and risk. Autocracies offer more stability, since autocrats don't have to get policies approved by legislators, often are unchecked by legal institutions and don't have to worry about how their decision poll with voters. Companies operating in autocracies can be promise rules that are fixed, regulations that don't change and tax rates that will stay constant. The catch, though, is that autocracies seldom transition smoothly, and when change comes, it is often unexpected and wrenching.In valuation terms, democracies create more going concern risk and autocracies create more worries about regime change. The former will show up as higher discount rates in a DCF valuation and the latter as post-DCF adjustments. While I prefer democracies to autocracies, there is no way, a priori, that you can argue that democracies are always better than autocracies or vice versa, at least when it comes to value, and here is why:The going concern risk that is added by being in a democracy will depend on how the democracy works. If you have a democracy, where the opposing parties tend to agree on basic economic principles and disagree on the margins, the going concern risk added will be small. In the United States, in the second half of the last century, both parties (Republicans and Democrats) agreed on the fundamentals of the economy, though one party may have been more favorable on some issues, for business, and less favorable on other issues. In contrast, if you have a democracy, where governments are unstable and the opposing parties have widely different views on the very fundamentals of how an economy should be structured, the effect on going concern risk will be much higher. The regime change risk in an autocracy will vary in how the autocracy is structured and how transitions happen. Autocracies structured around a person are inherently more unstable than autocracies built around a party or ideology, and transitions are more likely to be violent if the military is involved in regime change, in either direction. In addition, violent regime changes feed on themselves, with memories of past violent meted out to a group driving the violence that it metes out, when its turn comes.In summary, when you are trying to decide on whether a business is worth more in a democracy than in a dictatorship, you are being asked to trade off more continuous, going concern risk in the former for the more stable environment of the latter, but with more discontinuous risk. I have deliberately stayed away from using specific country examples in this section, because this argument is more emotion than intellect, but you can fill your own contrasts of countries, and make your own judgments.

ConclusionI have often described valuation as a craft, where mastery is an elusive goal and the key to getting better is working at doing more valuation. I am glad that I valued Aramco, because it is an unconventional investment, a company where I have to worry more about political risks than economic ones. The techniques I develop on Aramco will serve me well, not only when I value Latin American companies, as that continent seems to be entering one of its phases of disquiet, but when I value developed market companies, as Europe and the US seem to be developing emerging market traits.

YouTube Video

Blog Posts

A coming out party for an Oil Colossus: Aramco's IPOValuation LinksAramco Valuation(s)

Going Concern and Truncation RisksRisk is part and parcel of investing. That said, risk came come from many sources and not all risk is created equal, to investors. In fact, modern finance was born from the insight that for a diversified investor, it is only risk that you cannot diversify away, i.e., macroeconomic risk exposure, that affects value. In this section, I want to examine another stratification of risk into going concern and truncation risk that is talked about much less, but could matter even more to value.

DCF Valuation: A Going Concern Judgment The intrinsic value of a company has always been a function of its expected cash flows, its growth and how risky the cash flows are, but in recent decades a combination of access to data and baby steps in bringing economic models into valuation has resulted in the development of discounted cashflow valuation as a tool to estimate intrinsic value. Put simply, the discounted cash flow value of an asset is:

Extended to a publicly traded company, with a potential life in perpetuity, this value can be written as:

If you are a reader of my posts, it should come as no mystery to you that I not only use DCF models to value companies, but that I believe that people under estimate how adaptable it is, usable in valuing everything from start ups to infrastructure projects. There is, however, one significant limitation with DCF models that neither its proponents nor its critics seem be aware of, and it needs to be addressed. Specifically, a DCF is an approach for valuing going concerns, and every aspect of it is built around that presumption. Thus, you estimate expected cash flows each year for the firm, as a going concern, and your discount rate reflects the risk that you see in the company as a going concern. In fact, it is this going concern assumption that allows us to assume that cash flows continue for the long term, sometimes forever, and attach a terminal value to these cash flows.

Truncation Risks If you accept the premise that a DCF is a going concern value, you are probably wondering what other risks there may be in investing that are being missed in a DCF valuation. The risks that I believe are either ignored or incorrectly incorporated into value are truncation risks. The simplest way of illustrating the difference between going concern and truncation risks is by picking a year in your cash flow estimation, say year 3. With going concern risk, you are worried about the actual cash flows in year 3 being different from your expectations, but with truncation risk, you are worried about whether there will be a year 3 for your company.

So, what types of risk will fall into the truncation risk category? Looking at the corporate life cycle, you will see truncation risk become not just significant, but is perhaps the dominant risk that you worry about, age both ends of the life cycle. With start ups and young companies, it is survival risk that is front and center, given that approximately two thirds of start ups never make it to becoming viable businesses. With declining and aging companies, especially laden with debt, it is distress risk, where the company unable to meet its contractual obligations, shutters its doors and liquidates it assets. Looking at political risk, truncation risk can come in many forms, starting with nationalization risk, where a government takes over your business and pays you nothing in some cases and less than fair value in the rest, but extending to other expropriation risks, where you still are allowed to hold equity, but in a much less valuable concern.

Since truncation risk is more the rule than the exception, and it is the dominant risk in some companies, you would think that investors and analysts valuing these companies will have devised sensible ways of incorporating the risk, but you would be wrong.

The most common approach to dealing with truncation risk is for analysts to hike up the discount rate, using the alluring argument that if there is more risk, you would demand a higher return. The problem, though, is that this higher discount rate still goes into a DCF where expected cash flows continue in perpetuity, creating an internal contradiction, where you increase the discount rate for truncation risk but you do nothing to the cash flows. In addition, the discount rate that these analysts use are made up, higher just for the sake of being higher, with no rationale for the adjustment. With venture capitalists, this shows up as absurdly high target rates of 40%, 50% or 60%, fiction in a world where these VCs actually deliver returns closer to 15-20%. Discount rates are blunt instruments and are incapable of carrying the burden of truncation risk, and should not be made to do so.Some analysts take the more sensible approach of scenario analysis, allowing for good and bad scenarios (including failure or nationalization) but never close the loop by attaching probabilities to the scenarios. Instead, they leave behind ranges for the value that are so wide as to be useless for decision making purposes. My suggestion is that you use a decision tree approach, where you not only allow for different scenarios, but you make these scenarios cover all possibilities and then attach a probability to each one. In the case of a start up, then, your two possible outcomes will be that the company will make it as a going concern and that it will not, and you will follow through with a DCF, with a going concern discount rate, yielding the value for the going concern outcome, and a liquidation providing your judgment for what the company will be worth, in the failure scenario:

Since you have probabilities for each outcome, you can compute an expected value. If you do this, you should expect to see discount rates for companies prone to failure (young start ups and declining firms) be drawn from the same distribution as that for healthy companies, but the adjustment for failure will be in the post-DCF adjustments. Put more simply, you should see 12-15% as costs of capital for even the riskiest start-ups, in a DCF, never 40-50%, but your post value adjustments for failure and its consequences will still take their toll.

The Aramco Valuation: Bringing in Truncation Risk In my last post, I valued Aramco in a DCF, using three measures of cash flows from dividends to potential dividends to free cash flows to the firm and arrived at values that were surprisingly close to each other, centered around $1.65 trillion, for the equity. Note, though, that these are going concern values, and reflect the expectation that while there may be year to year changes in cash flows, as oil prices changes, management recalibrate and the government tweaks tax and royalty rates, the company will be a going concern and that it will not suffer catastrophic damage to its core asset of low-cost oil reserves. For many investors in Aramco, the prime concern may be less on these fronts and more on whether the House of Saud, as the backer of the promises that Aramco is making its investors, will survive intact for the next few decades.

DCF Valuation: Going Concern Risk Reviewing my discounted cash flow valuations of Aramco, you will notice that I began with a risk free rate in US dollars, because my currency choice was that currency. I then adjusted for risk, using a beta for Aramco, based upon REITs/royalty trusts for the promised dividend model and integrated oil companies for the potential dividends/free cash flow models, and an equity risk premium for Saudi Arabia of only 6.23%, with a country risk premium of 0.79% estimated for the country added to the mature market premium estimated for the US. The end result is that I had costs of equity ranging from 4.82% for promised dividends to 8.15% for cash flows.

The biggest push back I have had on my valuations is that the cost of equity seems low for a country like Saudi Arabia, and my response is that you are right, if you consider all of the risk in investing in a Saudi equity. However, much of the risk that you are contemplating in Saudi Arabia is political risk, or put more bluntly, the risk of regime change in the country, that could have dramatic effects on value. In fact, if you remove that risk from consideration and look at the remaining risk, Aramco is a remarkably safe investment, with the safety coming from its access to huge oil reserves and mind-boggling profits and cash flows. The DCF values that I have estimated, centered around $1.65 trillion, are therefore values before adjusting for the risk of regime change.

Regime Change Concerns If you invest in Aramco, you clearly have an interests in who rules and runs the country, since every aspect of your valuation is dependent on that assumption. If the House of Saud continues to rule, I believe that the company will be the cash cow that I project it to be in my DCF and the values that I estimated hold. If the Arab spring comes to Riyadh and there is a regime change, the foundations of my value can either crack or be completely swept away, with cash flows, growth and risk all up for re-estimation. In fact, to complete my valuation, I need to bring both the probability of regime change and the consequences into my final valuation:

Consider the most extreme case. If you believe that regime change in imminent and certain, and that the change will be extreme (with equity being expropriated and Aramco being brought back entirely into the hands of the state), my expected value for equity becomes zero:

If at the other extreme, you either believe that regime change will never happen, or even if it does, the new regime will not want to hurt the goose that lays the golden eggs and leaves existing terms in place, the value effect of considering regime change will be zero. The truth lies between the extremes, though where it lies is open for debate. I believe that there remains a non-trivial chance (perhaps as high as 20%) that there will be a regime change over the long term and that if there is one, there will be changes that reduce, but not extinguish, my claim, as an equity investor, on the cash flows.

That, in an entirely subjective nutshell, is why I think Aramco's equity value is closer to $1.5 trillion than $1.7 trillion. As with all my other valuations, I understand that your judgments on Aramco will be different from mine, but I think that the disagreements we have are not so much on the going concern estimates of cash flows and risk but on the likelihood and consequences of regime change.

Democracies versus AutocraciesI am not a political scientist, but I have always been fascinated by the question of how political structure and economic value are intertwined. Specifically, would you attach more value to a company or project operating in a democracy or in an autocracy? The approach that I have described in this post to deal with going concern and regime change risk allows me one way of trying too answer the question. Democracies are messy institutions, where governments change and policies morph, because voters change their minds. Put simply, a democracy generally cannot offer any business iron clad guarantees about regulations not changing or tax rates remaining stable, because the government that offers those promises first has to get them approved by legislatures, often can be checked by legal institutions and, most critically, can be voted out of office. Consequently, companies operating in democracies will always complain more about the rules constantly changing, and how those changing rules affect cash flows, growth and risk. Autocracies offer more stability, since autocrats don't have to get policies approved by legislators, often are unchecked by legal institutions and don't have to worry about how their decision poll with voters. Companies operating in autocracies can be promise rules that are fixed, regulations that don't change and tax rates that will stay constant. The catch, though, is that autocracies seldom transition smoothly, and when change comes, it is often unexpected and wrenching.In valuation terms, democracies create more going concern risk and autocracies create more worries about regime change. The former will show up as higher discount rates in a DCF valuation and the latter as post-DCF adjustments. While I prefer democracies to autocracies, there is no way, a priori, that you can argue that democracies are always better than autocracies or vice versa, at least when it comes to value, and here is why:The going concern risk that is added by being in a democracy will depend on how the democracy works. If you have a democracy, where the opposing parties tend to agree on basic economic principles and disagree on the margins, the going concern risk added will be small. In the United States, in the second half of the last century, both parties (Republicans and Democrats) agreed on the fundamentals of the economy, though one party may have been more favorable on some issues, for business, and less favorable on other issues. In contrast, if you have a democracy, where governments are unstable and the opposing parties have widely different views on the very fundamentals of how an economy should be structured, the effect on going concern risk will be much higher. The regime change risk in an autocracy will vary in how the autocracy is structured and how transitions happen. Autocracies structured around a person are inherently more unstable than autocracies built around a party or ideology, and transitions are more likely to be violent if the military is involved in regime change, in either direction. In addition, violent regime changes feed on themselves, with memories of past violent meted out to a group driving the violence that it metes out, when its turn comes.In summary, when you are trying to decide on whether a business is worth more in a democracy than in a dictatorship, you are being asked to trade off more continuous, going concern risk in the former for the more stable environment of the latter, but with more discontinuous risk. I have deliberately stayed away from using specific country examples in this section, because this argument is more emotion than intellect, but you can fill your own contrasts of countries, and make your own judgments.

ConclusionI have often described valuation as a craft, where mastery is an elusive goal and the key to getting better is working at doing more valuation. I am glad that I valued Aramco, because it is an unconventional investment, a company where I have to worry more about political risks than economic ones. The techniques I develop on Aramco will serve me well, not only when I value Latin American companies, as that continent seems to be entering one of its phases of disquiet, but when I value developed market companies, as Europe and the US seem to be developing emerging market traits.

YouTube Video

Blog Posts

A coming out party for an Oil Colossus: Aramco's IPOValuation LinksAramco Valuation(s)

Published on November 19, 2019 15:16

November 18, 2019

A coming out party for the world's most valuable company: Aramco's long awaited IPO!

In a year full of interesting initial public offerings, many of which I have looked at in this blog, it is fitting that the last IPO I value this year will be the most unique, a company that after its offering is likely to be the most valuable company in the world, the instant it is listed. I am talking about Aramco, the Saudi Arabian oil colossus, which after many false starts, filed a prospectus on November 10 and that document, a behemoth weighing in at 658 pages, has triggered the listing clock.

Aramco: History and Set Up

Aramco’s beginnings trace back to 1933, when Standard Oil of California discovered oil in the desert sands of Saudi Arabia. Shortly thereafter, Texaco and Chevron formed the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco) to develop oil fields in the country and the company also built the Trans-Arabian pipeline to deliver oil to the Mediterranean Sea. In 1960, the oil producing countries, then primarily concentrated in the Middle East, created OPEC and in the early 1970s, the price of oil rose rapidly, almost quadrupling in 1973. The Saudi Government which had been gradually buying Aramco’s assets, nationalized the company in 1980 and effectively gave it full power over all Saudi reserves and production. The company was renamed Saudi Aramco in 1988.

To understand why Aramco has a shot at becoming the most valuable company in the world, all you have to do is look at its oil reserves. In 2018, it was estimated that Aramco had in excess of 330 billion barrels of oil and gas in its reserves, a quarter of all of the world’s reserves, and almost ten times those of Exxon Mobil, the current leader in market cap, among oil companies. To add to the allure, oil in Saudi Arabia is close to the surface and cheap to extract, making it the most profitable place on oil to own reserves, with production costs low enough to break even at $20-$25 a barrel, well below the $40-$50 break even price that many other conventional oil producers face, and even further below the new entrants into the game. This edge in both quantity and costs plays out in the numbers, and Aramco produced 13.6 million barrels of oil & gas every day in 2018, and reported revenues of $355 billion for the year, on which it generated operating income of $212 billion and net income of $111 billion. In short, if your complaint about the IPOs that you saw this year was that they had little to show in terms of revenues and did not have money-making business models, this company is your antidote.

Aramco, Saudi Arabia and the House of Saud!

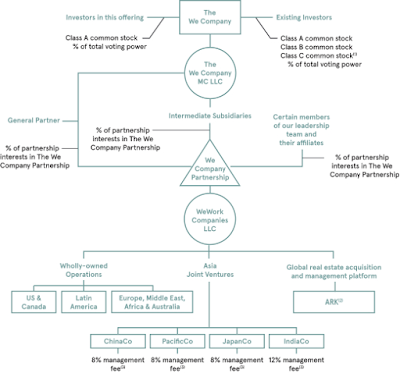

The numbers that are laid out in the annual report are impressive, painting a picture of the most profitable company in the world, with almost unassailable competitive advantages, investors need to be clear that even after its listing, Aramco will not be a conventional company, and in fact, it will never be one. The reason is simple. Saudi Arabia is one of the wealthier countries in the world, on a per capital basis, and one of the 20 largest economies, in terms of GDP, but it derives almost 80% of that GDP from oil. Thus, a company that controls those oil spigots is a stand in for the entire country, and over the last few decades, it should not surprise you to learn that the Saudi budget has been largely dependent on the cash flows it collects from Aramco, in royalties and taxes, and that Aramco has also invested extensively in social service projects all over the country. The overlap between company and country becomes even trickier when you bring in the Saudi royal family, and its close to absolute control of the country, which also means that Aramco’s fortunes are tied to the royal family’s fortunes. It is true that there will still be oil under the ground, even if there is a change in regime in Saudi Arabia, but the terms laid out in the prospectus reflect the royal family’s promises and may very well be revisited if control changed. Should this overlap between company, country and family have an effect on how you view Aramco? I don’t see how it cannot and it will play out in many dimensions:Corporate governance: After the IPO, the company will have all the trappings of a publicly traded company, from a board of directors to annual meetings to the rituals of financial disclosure. These formalities, though, should not obscure the fact that there is no way that this company can or ever will be controlled by shareholders. The Saudi government is open about this, stating in its prospectus that “the Government will continue to own a controlling interest in the Company after the Offering and will be able to control matters requiring shareholder approval. The Government will have veto power with respect to any shareholder action or approval requiring a majority vote, except where it is required by relevant rules for the government.” While one reason is that the majority control will remain with the government, it is that it would be difficult to visualize and perhaps to dangerous to even consider allowing a company that is a proxy for the country to be exposed to corporate control costs. After all, a hostile acquisition of the company would then be the equivalent of an invasion of the country. The bottom line is that if you invest in Aramco, you should recognize that you are more capital provider than shareholder and that you will have little or no say in corporate decision making.Country risk: Aramco has a few holdings and joint ventures outside Saudi Arabia, but this company is not only almost entirely dependent on Saudi Arabia but its corporate mission will keep it so. Put differently, a conventional oil company that finds itself overdependent on a specific country for its production can try to reduce this risk by exploring for oil or buying reserves in other countries, but Aramco will be limited in doing this, because of its national status.Political risk: For decades, the Middle East has had more than its fair share of turmoil, terrorism and war, and while Saudi Arabia has been a relatively untouched part, it too is being drawn into the problem. The drone attack on its facilities in Shaybah in August 2019, which not only caused a 54% reduction in oil production, but also cost billions of dollars to the company was just a reminder of how difficult it is to try to be oasis. On an even larger scale, the last decade has seen regime changes in many countries in the Middle East, with some occurring in countries, where the ruling class was viewed as insulated. The Saudi political order seems settled for the moment, with the royal family firmly in control, but that too can change, and quickly.In short, this is not a conventional company, where shareholders gather at annual meetings, elect boards of directors and the corporate mission is to do whatever is necessary to increase shareholder well being, and it never will be one. For some, that feature alone may be sufficient to take the company off their potential investment list. For others, it will be something that needs to be factored into the pricing and value, but at the right price or value, presumably with a discount built in for the country and political risk overlay, the company can still be a good investment.

IPO Twists

Before we price and value Aramco, there are a few twists to this IPO that should be clarified, since they may affect how much you are willing to pay. The prospectus, filed on November 10, sheds some light:Dividends: In the ending on September 30, 2019, Aramco paid out an ordinary dividend of $13.4 billion, entirely to the Saudi Government, and it plans to pay an additional interim dividend of at least $9.5 billion to the government, prior to the offering. The company commits to paying at least $75 billion in dividends in 2020, with holders of shares issued in the IPO getting their share, and to maintaining these dividends through 2024. Beyond 2024, dividends will revert back to their normal discretionary status, with the board of directors determining the appropriate amount. As an aside, the dividends to non-government shareholders will be paid in Saudi Riyal and to the government in US dollars.IPO Proceeds: The prospectus does not specify how many shares will be offered in the initial offering, but it is not expected to be more than a couple of percent of the company. None of the proceeds from the IPO will remain in Aramco. The government will redirect the proceeds elsewhere, in pursuit of its policy of making Saudi Arabia into an economy less dependent on oil.Trading constraints: Once the offering is complete, the shares will be listed on the Saudi stock exchange and its size will make it the dominant listing overnight, while also subjecting it to the trading restrictions of the exchange, including a limit of a 10% movement in the stock price in a day; trading will be stopped if it hits this limit.Inducements for Saudi domestic investors: In an attempt to get more domestic investors to hold the stock, the Saudi government will give one bonus share, for every ten shares bought and held for six months, by a Saudi investor, with a cap at a hundred bonus shares.Royalties & Taxes: In my view, it is this detail that has been responsible for the delay in the IPO process and it is easy to see why. For all of its life, Aramco has been the cash machine that keeps Saudi Arabia running, and the cash flows extracted from the company, whether they were titled royalties, taxes or dividends, were driven by Saudi budget considerations, rather than corporate interests. Investors were wary of buying into a company, where the tax rate and the royalties were fuzzy or unspecified and the prospectus lays out the following. First, the corporate tax rate will be 20% on downstream taxable income, though tax rates on different income streams can be different. The Saudi government also imposes a Zakat, a levy of 2.5% on assessed income, thus augmenting the tax rate. In sum, these tax rate changes were already in effect in 2018, and the company paid almost 48% of its taxable income in taxes that year. Second, the royalties on oil were reset ahead of the IPO and will vary, depending on the oil price, starting at 40% if oil prices are less than $70/barrel, increasing to 45% if they fell between $70 and $100, and becoming 80% if the oil price exceeds $100/barrel. A Pricing of Aramco

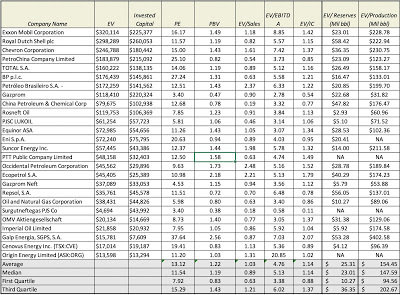

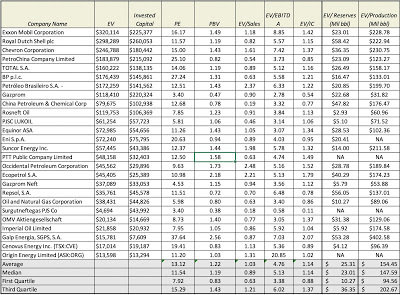

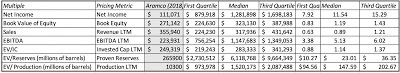

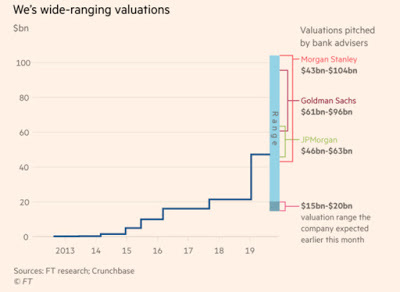

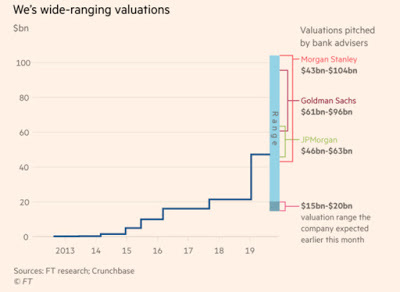

The initial attempts by the Saudi government to take Aramco public, as long as two years ago, came with an expectation that the company would be “valued” at $2 trillion or more. Since the IPO announcement a few weeks ago, much has been made about the fact that there seem to be wide divergences in how much bankers seem to think Aramco is worth, with numbers ranging from $1.2 billion to $2.3 trillion. Before we take a deep dive into how the initial assessments of value were made and why there might be differences, I think that we should be clear eyed about these numbers. Most of these numbers are not valuations, based upon an assessment of business models, risk and profitability, but instead represent pricing of Aramco, where assessment of price being made by looking at how the market is pricing publicly traded oil companies, relative to a metric, and extending that to Aramco, adjusting (subjectively) for its unique set up in terms of corporate governance, country risk and political risk. In the table below, I look at integrated oil companies, with market caps in excess of $10 billion, in October 2019, and how the market is pricing them relative to a range of metrics, from barrels of oil in reserve, to oil produced, to more conventional financial measures (revenues, earnings, cash flows):

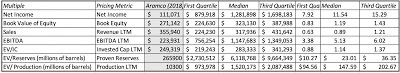

Download spreadsheetThe median oil company equity trades at about 13 times earnings, and was a business, at about the value of its annual revenues, and the market seems to be paying about $23 for every barrel of proven reserves of oil (or equivalent). In the table below, I have priced Aramco, using all of the metrics, and at the median and both the first and third quartiles:

Download spreadsheetThe median oil company equity trades at about 13 times earnings, and was a business, at about the value of its annual revenues, and the market seems to be paying about $23 for every barrel of proven reserves of oil (or equivalent). In the table below, I have priced Aramco, using all of the metrics, and at the median and both the first and third quartiles:

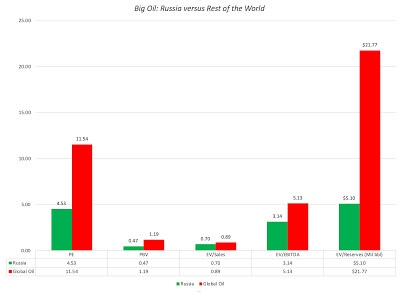

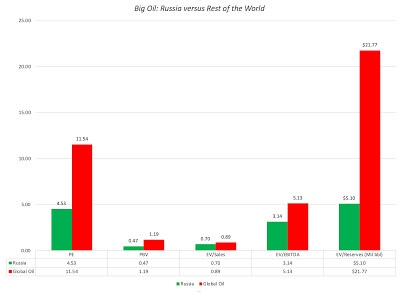

You can already see that if you are looking at how to price Aramco, the metric on which you base it on will make a very large difference: If you price Aramco based on its revenues of $356 billion or on its book value of equity of $271 billion, its value looks comparable or slightly higher than the value of Exxon Mobil and Royal Dutch, the largest of the integrated oil companies. That pricing, though, is missing Aramco’s immense cost advantage, which allows it to generate much higher earnings from the same revenues. Thus, when you base the pricing on Aramco’s EBITDA of $224 billion, you can see the pricing rise to above a trillion and if you shift to Aramco’s net income of $111 billion, the pricing approaches $1.5 trillion. The pricing is highest when you focus on Aramco’s most valuable edge, its control of the Saudi oil reserves and its capacity to produce more oil than any other oil company in the world. If you base the pricing on the 10.3 billion barrels of oil that Aramco produced in 2018, Aramco should be priced above $1.5 trillion and perhaps even closer to $2 trillion. If you base the pricing on the 265.9 billion barrels of proven reserves that Aramco controls for the next 40 years, Aramco’s pricing rises to sky high levels.If you are a potential investor, the pricing range in this table may seem so large, as to make it useless, but it can still provide some useful guidelines. First, you should not be surprised to see the roadshows center on Aramco’s strongest suits, using its huge net income (and PE ratios) as the opening argument to set a base for its pricing, and then using its reserves as a reason to augment that pricing. Second, there is a huge discount on the pricing, if just reserves are used as the basis for pricing, but there are two good reasons why that high pricing will be a reach:Production limits: Aramco not only does not own its reserves in perpetuity, with the rights reverting back to the Saudi government after 40 years, with the possibility of a 20-year extension, if the government decides to grant it, but it is also restricted in how much oil it can extract from those reserves to a maximum of 12 billion barrels a year.Governance and Risk: We noted, earlier, that Aramco’s flaws: the government’s absolute control of it, the country risk created by its dependence on domestic production and the political risk emanating from the possibility of regime change. To see how this can affect pricing, consider how the five companies on the integrated oil peer group that are Russian (with Gazprom, Rosneft and Lukoil being the biggest) are priced, relative to the global average: Russian oil companies are discounted by 50% or more, relative to their peer group, and while Saudi Arabia does not have the same degree of exposure, the market will mete out some punishment.

Russian oil companies are discounted by 50% or more, relative to their peer group, and while Saudi Arabia does not have the same degree of exposure, the market will mete out some punishment.

A Valuation of AramcoThe value of Aramco, like that of any company in any sector, is a function of its cash flows, growth and risk. In fact, the story that underlies the Aramco valuation is that of a mature company, with large cash flows and concentrated country risk. That said, the structuring of the company and the desire of the Saudi government to use its cash flows to diversify the economy play a role in value.

General Assumptions

While I will offer three different approaches to valuing Aramco, they will all be built on a few common components.

First, I will do my valuation in US dollars, rather than Saudi Riyals, since as a commodity company, revenues are in dollars and the company reports its financials in US dollars (as well as Riyal). This will also allow me to evade tricky issues related to the Saudi Riyal being pegged to the US dollar though the reverberations from the peg unraveling will be felt in the operating numbers. Second, I will use an expected inflation rate of 1.00% in US dollars, representing a rough approximation of the difference between the US treasury bond rate and the US TIPs rate. Third, I will use the equity risk premium of 6.23% for Saudi Arabia, representing about a 0.79% premium over my estimate of a mature market premium of 5.44% at the start of November 2019. Finally, rather than use the standard perpetual growth model, where cash flows continue forever, I will use a 50-year growth period, representing the fact that the company's primary asset, its oil reserves, are not infinite and will run out at some point in time, even if additional reserves are discovered. In fact, at the current production level, the existing reserves will be exhausted in about 35 years.

Valuation: Promised Dividends

While the dividend discount model is far too restrictive in its assumptions about payout to be used to value most companies, Aramco may be the exception, especially given the promise in the prospectus to pay out at least $75 billion in dividends every year from 2020 and 2024, and the expectation that these dividends will continue and grow after that. There is one additional factor that makes Aramco a good candidate for the dividend discount model and that is the absolute powerlessness that stockholders will have at the company to change how much it returns to shareholders. To complete my valuation of Aramco using the promised dividends, I will make two additional assumptions: