Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 13

June 19, 2020

A Viral Market Update X: A Corporate Life Cycle Perspective

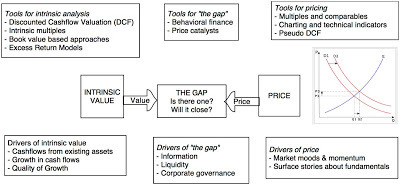

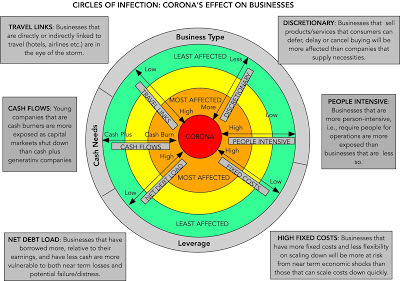

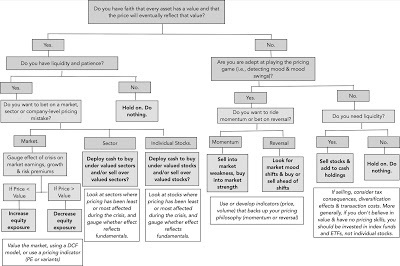

Fear and greed are dueling forces in financial markers at all times, but especially so in periods of uncertainty, when they pull in opposite directions, causing wild market swings and momentum shifts. I think that no matter what your market views are right now, you would agree that we are in a period of intense uncertainty, with divergent views on how this pandemic will play out, not just in the coming months, but in the coming years. It is this divergence that have been at the heart of both the steep fall in equity markets in February and March, and the equally precipitous rise in April and May. As US equity markets climb back towards pre-crisis levels, the focus on market levels may be missing the underlying shift in value that has occurred across companies. In this post, I will focus on this shift, using the framework of a corporate life cycle, and record a redistribution of value from older, low growth, more capital intensive companies to younger, high growth companies. It is possible that this shift is the result of irrational exuberance on the part of young, inexperienced investors, but I think that a more plausible explanation is that it reflects not only the unique nature of this crisis, but also a changing business landscape.

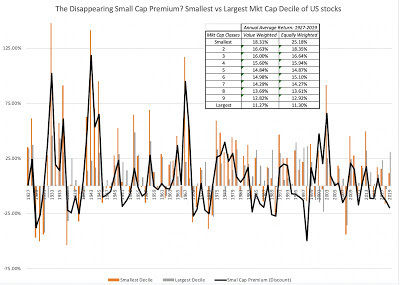

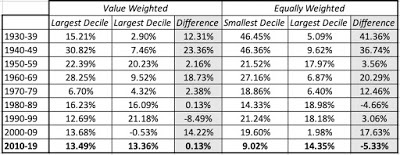

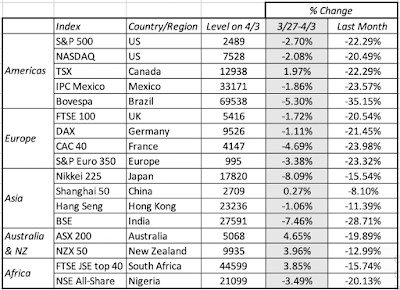

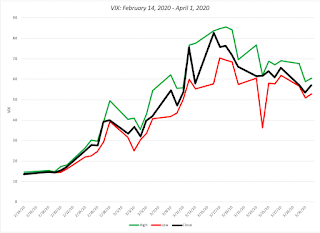

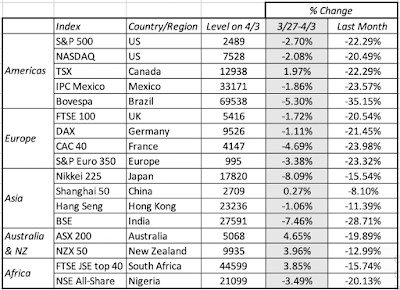

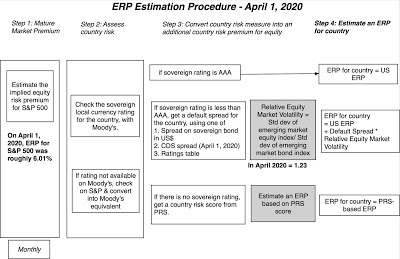

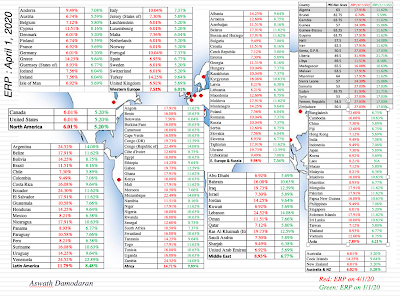

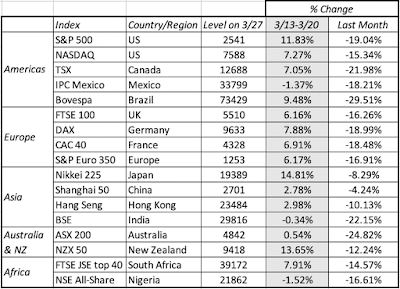

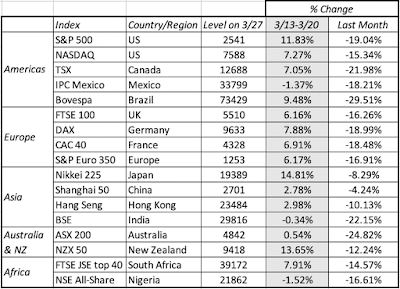

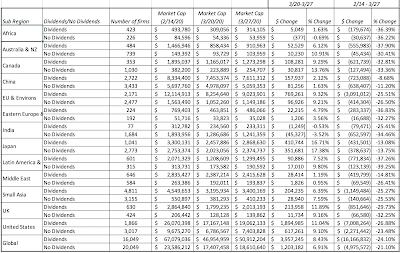

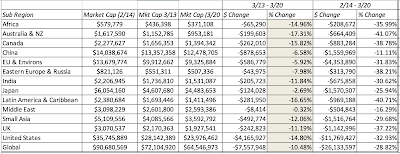

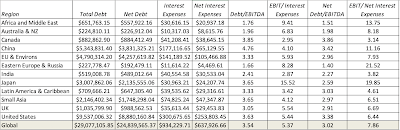

Updating the MarketAs with my previous updates, I will start with a chronicling of how markets have behaved in the two weeks since my last update, and overall, during the crisis. Let's start with equity indices, where we saw one week of relative stability (5/29-6/5) and a week of drama (6/5-6/12), after surges in April and May: Download dataFor those who thought that the worst of the crisis was behind them, June 11 delivered the message that this crisis is not quite done, as the S&P 500 dropped 7%, and markets around the world followed. I have computed the returns since February 14, broken down into two time periods, with the first stretching from February 14 to March 20, and the second from March 20 to June 12. Every equity index that I list in this table dropped in the first phase, with some indices losing more than 30%, as fear stalked markets around the world. In the second phase, every index posted positive returns, with some climbing back almost to pre-crisis levels. I will return to look at equities in more detail in the next section, but as stocks were going through contortions, US treasury yields were also on the move:

Download dataFor those who thought that the worst of the crisis was behind them, June 11 delivered the message that this crisis is not quite done, as the S&P 500 dropped 7%, and markets around the world followed. I have computed the returns since February 14, broken down into two time periods, with the first stretching from February 14 to March 20, and the second from March 20 to June 12. Every equity index that I list in this table dropped in the first phase, with some indices losing more than 30%, as fear stalked markets around the world. In the second phase, every index posted positive returns, with some climbing back almost to pre-crisis levels. I will return to look at equities in more detail in the next section, but as stocks were going through contortions, US treasury yields were also on the move:

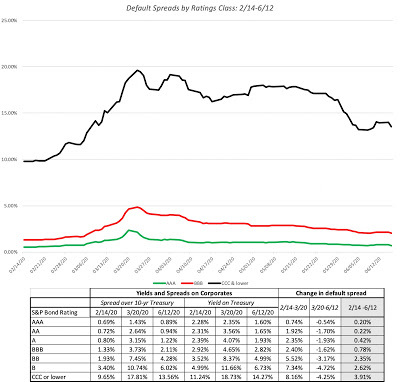

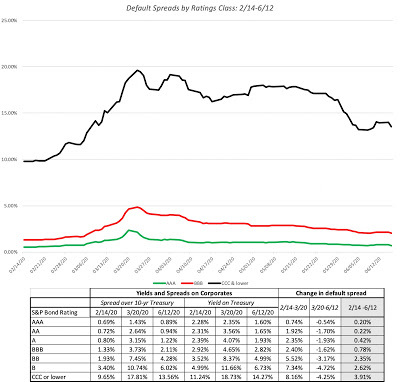

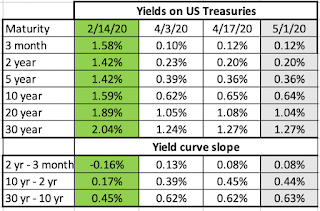

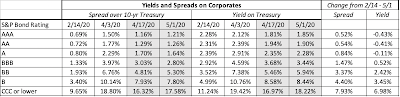

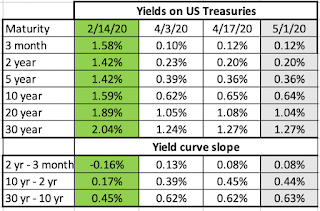

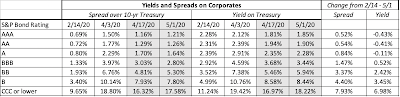

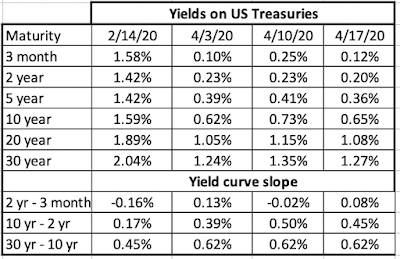

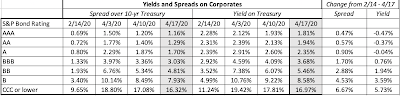

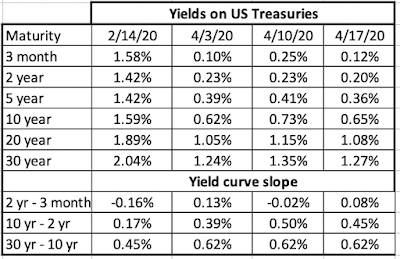

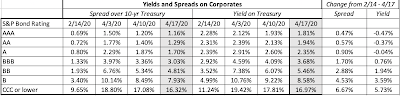

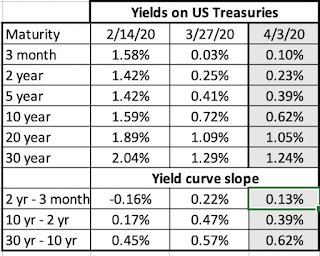

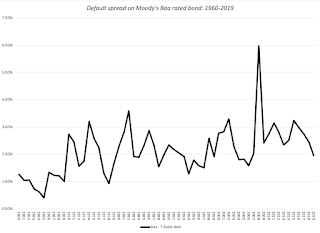

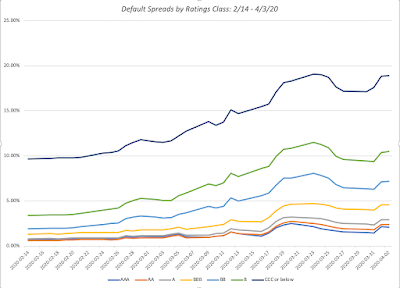

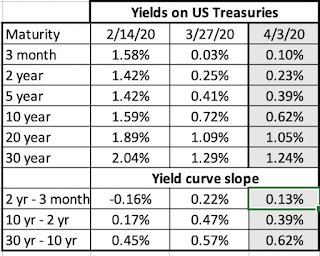

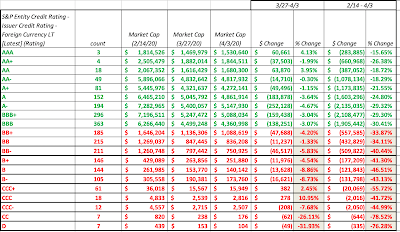

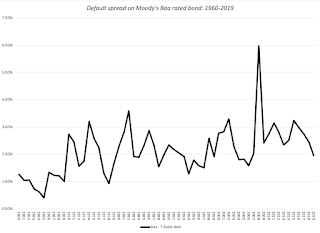

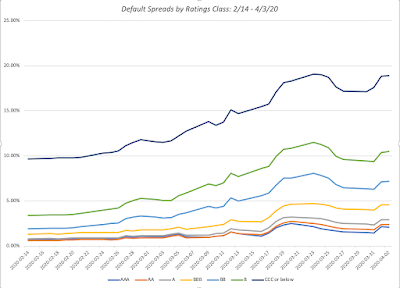

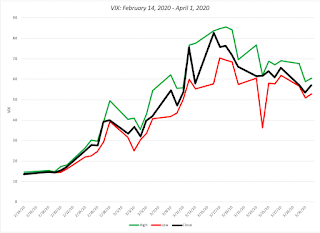

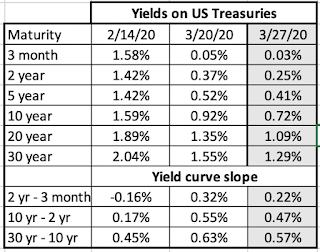

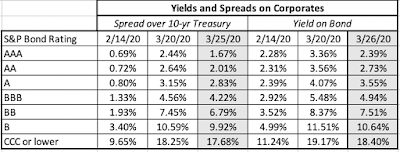

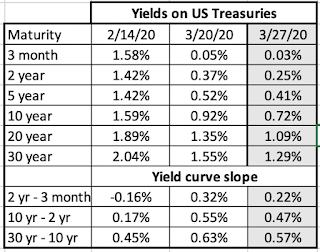

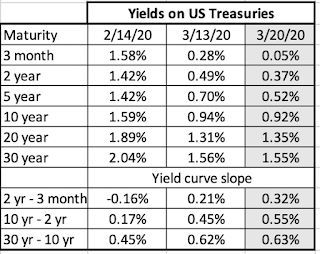

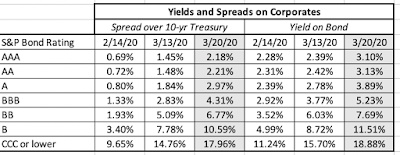

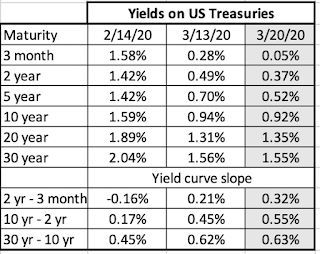

Download dataUS treasury rates dropped in the first weeks of the crisis, and with 3-month yields dropping close to zero and 10-year rates declining below 1%. While it is convenient to attribute everything that happens to interest rates to the Fed, note that much of the drop in rates occurred before the Fed's two big moves, the first one on March 15, where the Fed Funds rate was cut by 0.5% (almost to zero) and a $700 billion quantitative easing plan was announced, and the second one on March 23, when the Fed lifted the cap on its easing plan and extended its role as a backstop in the corporate bond and lending markets. While treasury rates were not affected much by the Fed's actions, its entry into the corporate bond market played a key role in turning the tide, where default spreads across ratings classes had been on the rise since February 14:

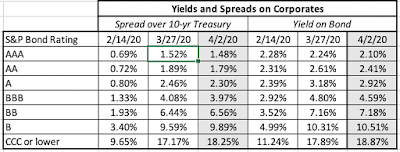

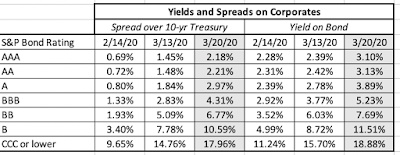

Download dataUS treasury rates dropped in the first weeks of the crisis, and with 3-month yields dropping close to zero and 10-year rates declining below 1%. While it is convenient to attribute everything that happens to interest rates to the Fed, note that much of the drop in rates occurred before the Fed's two big moves, the first one on March 15, where the Fed Funds rate was cut by 0.5% (almost to zero) and a $700 billion quantitative easing plan was announced, and the second one on March 23, when the Fed lifted the cap on its easing plan and extended its role as a backstop in the corporate bond and lending markets. While treasury rates were not affected much by the Fed's actions, its entry into the corporate bond market played a key role in turning the tide, where default spreads across ratings classes had been on the rise since February 14:

Download data

Download data

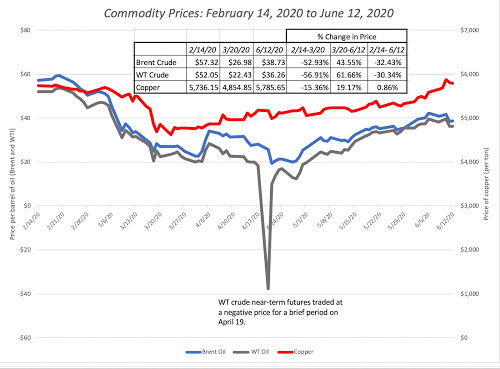

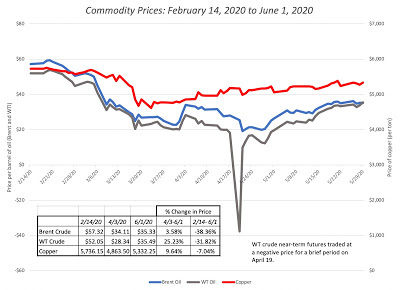

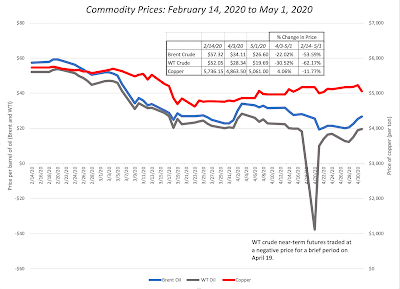

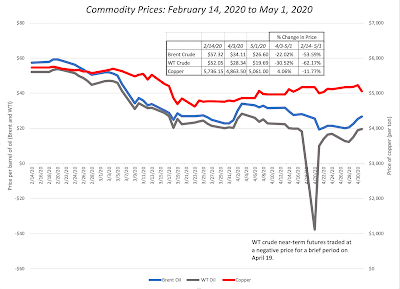

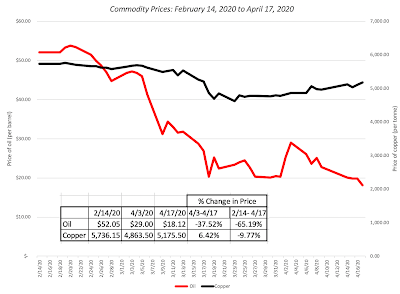

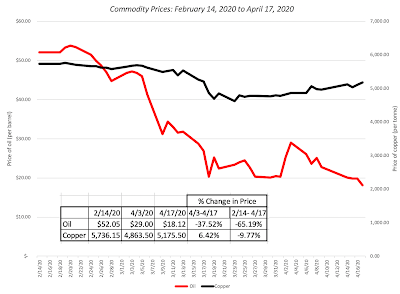

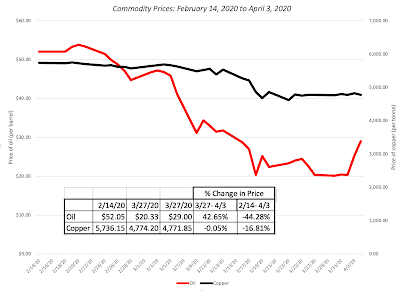

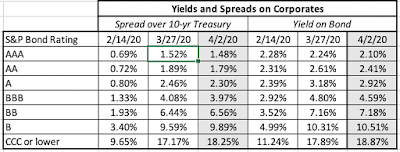

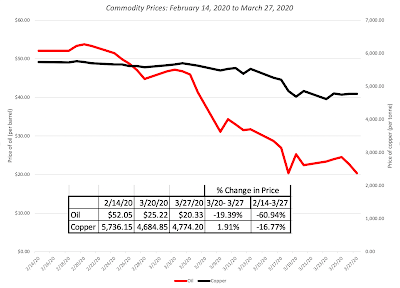

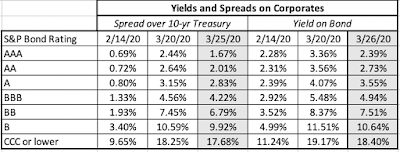

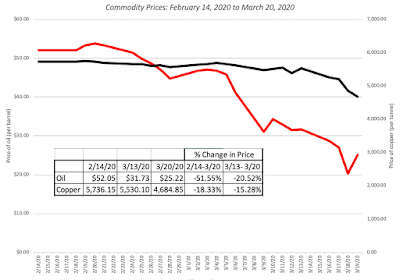

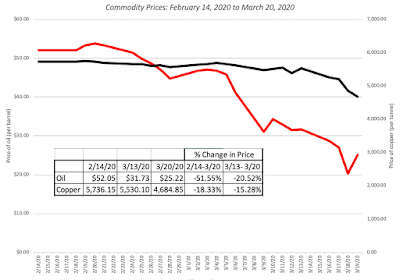

Default spreads followed the path of equities, widening significantly between February 14 and March 20, and falling back by June 12, albeit to levels higher then on February 14. The fear about how the pandemic would slow economic growth also affected commodity prices, and I chart the path of copper and oil, two commodities sensitive to global economic growth below:

Download data

Download data

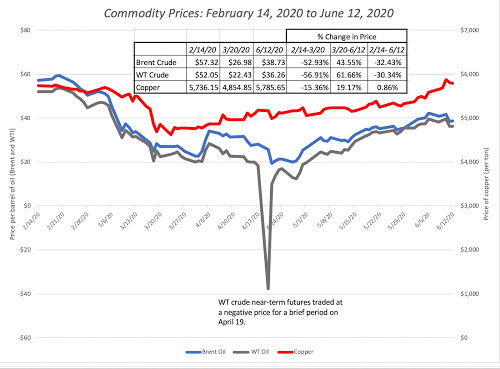

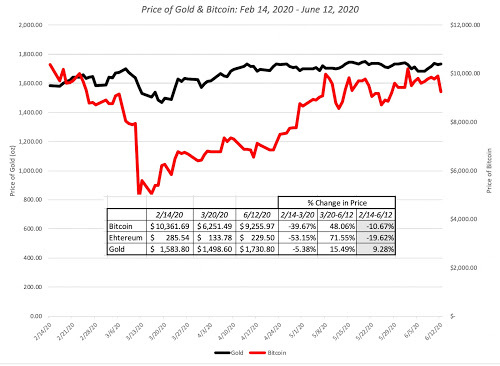

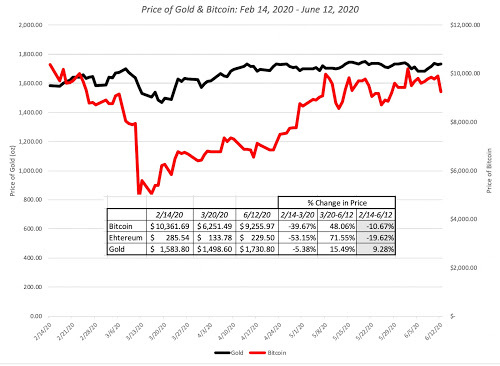

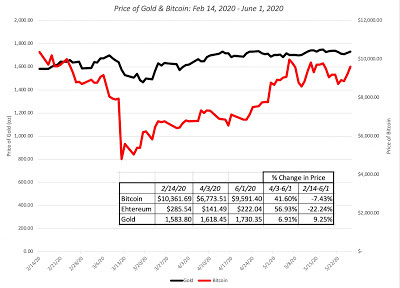

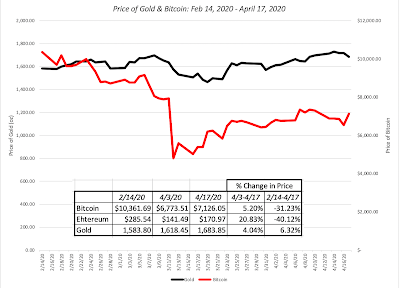

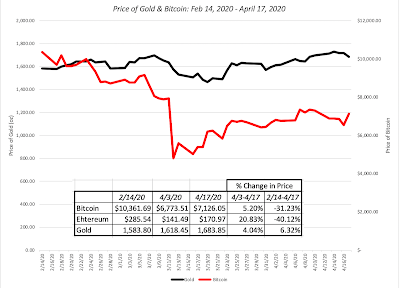

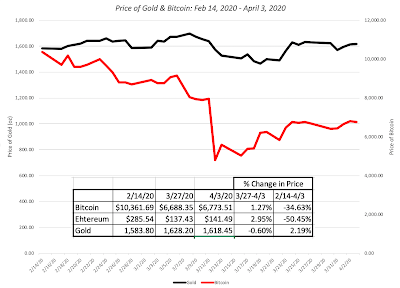

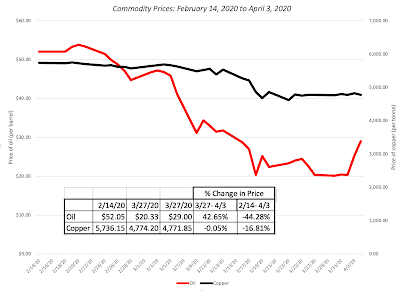

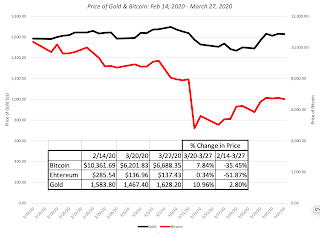

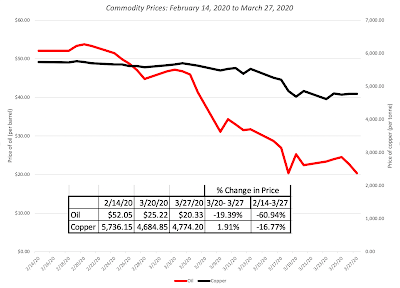

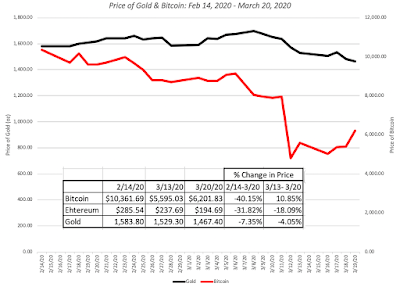

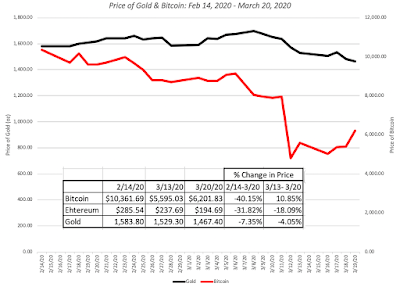

As with corporate bonds and equities, it is a tale of two periods, with commodity prices dropping between February 14 and March 20, before clawing their way back in the subsequent period. With copper, the market has retraced its entire decline, and it is now back to where it was trading at, on February 14. With oil, it is a different story, with a decline of more than 50% between February 14 and March 20 in both Brent and West Texas crude. and oil prices, notwithstanding a strong recovery between March 20 and June 12, are about 30% lower than they were on February 14. Finally, I look at gold and bitcoin, gold, because it has historically been a crisis asset and bitcoin, because it has been marketed by some as an alternative asset:

Download data

Download data

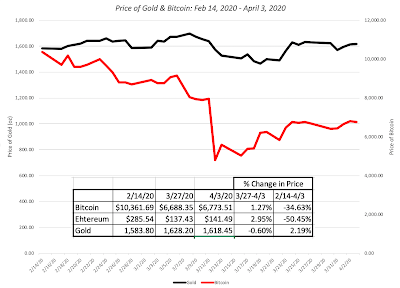

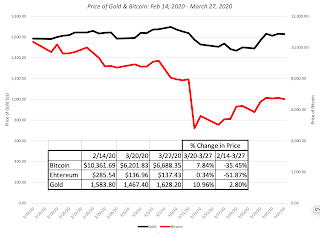

Gold has held its value and is up 9.28% during the crisis, though it saw less upside during the first few weeks of this crisis than in prior ones. Bitcoin has behaved more like equity, and very risky equity at that, during this crisis, dropping almost 40% between February 14 and March 20, before recovering to close down only 10.67% by June 12.

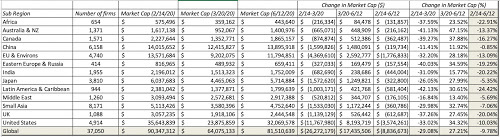

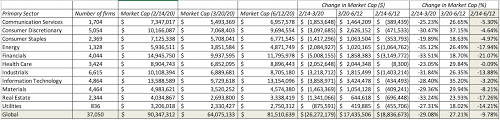

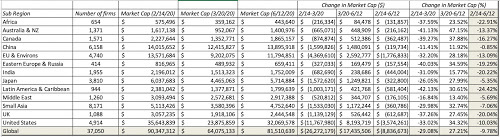

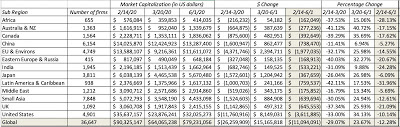

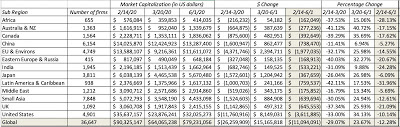

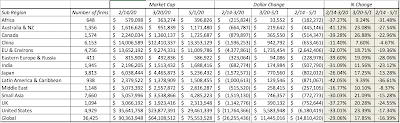

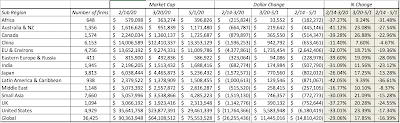

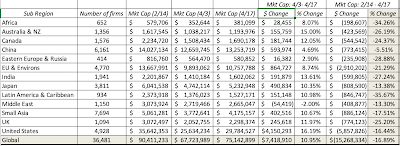

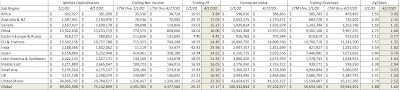

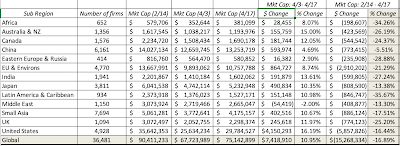

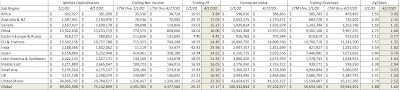

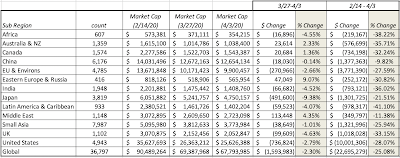

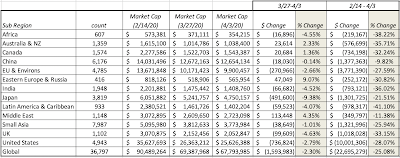

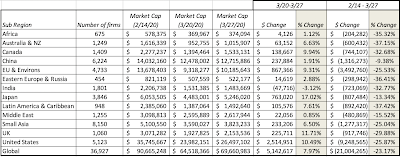

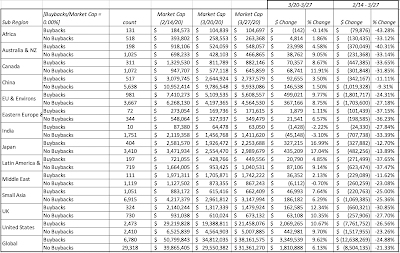

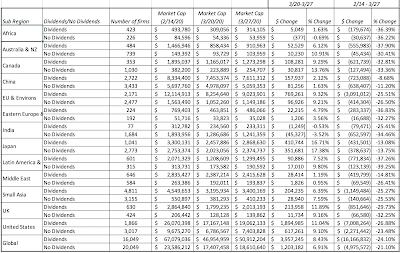

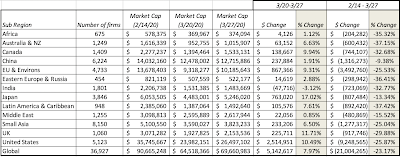

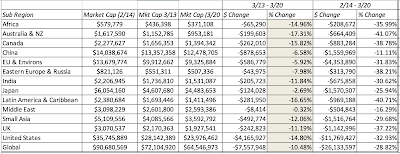

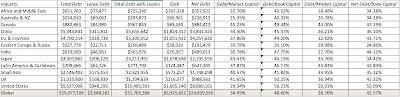

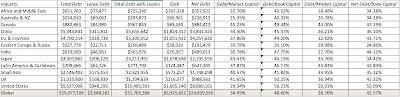

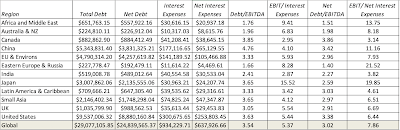

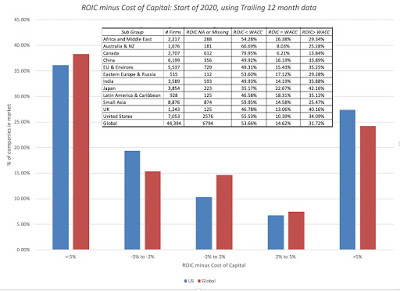

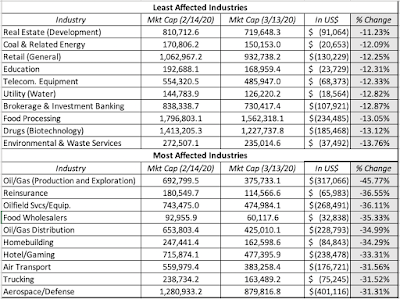

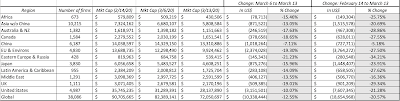

Equities: A BreakdownIn keeping with a practice I have adopted on my prior updates, I downloaded individual stock data on 37,050 publicly traded global companies, with market capitalizations exceeding $5 million, and computed changes in market cap, by region: Download data

Download data

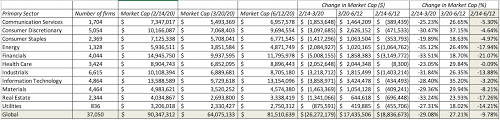

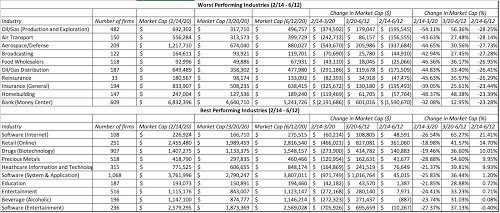

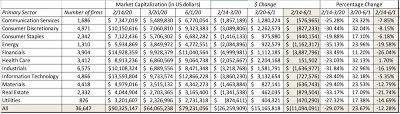

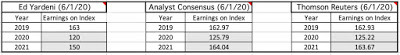

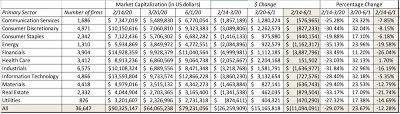

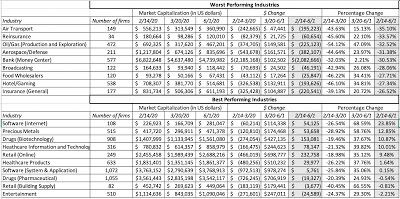

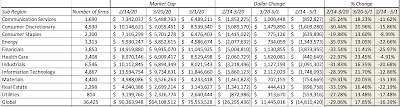

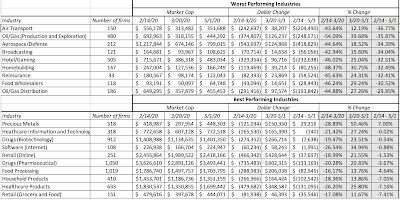

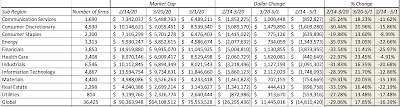

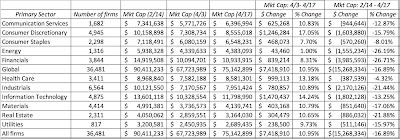

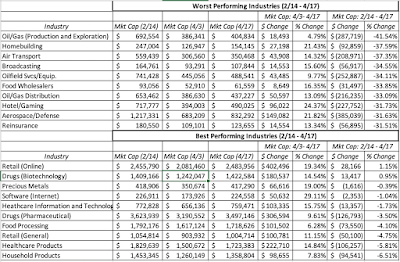

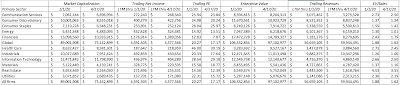

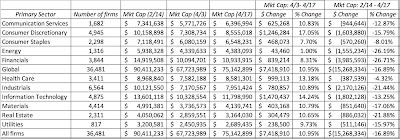

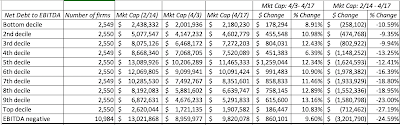

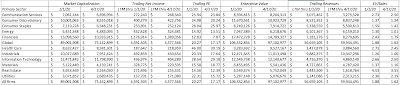

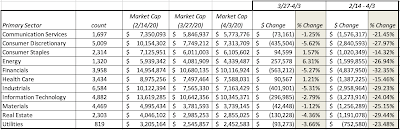

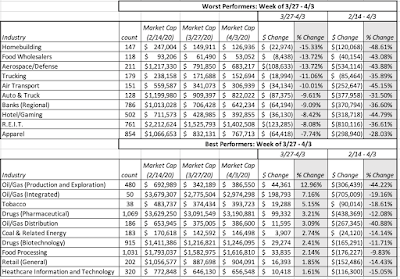

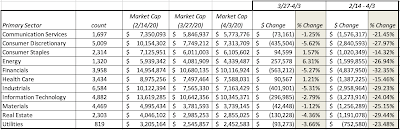

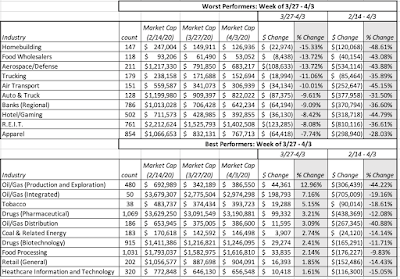

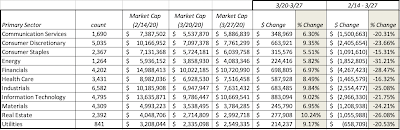

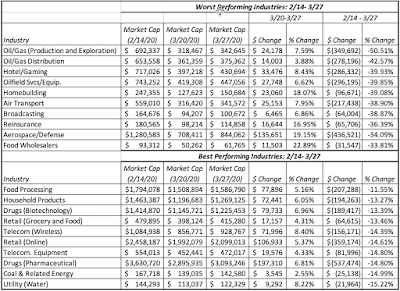

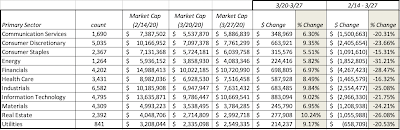

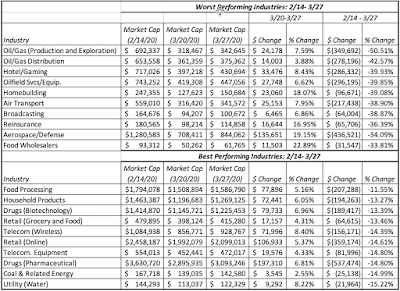

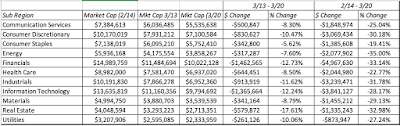

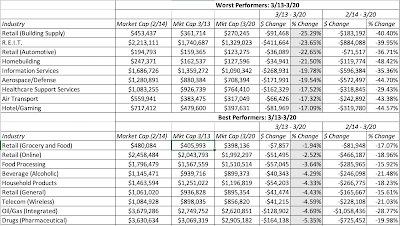

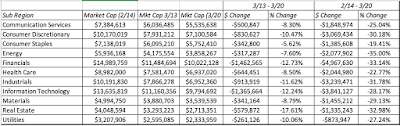

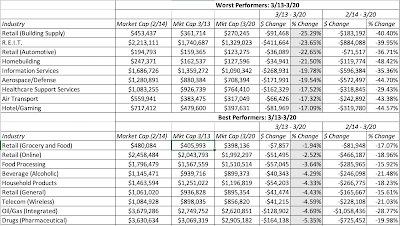

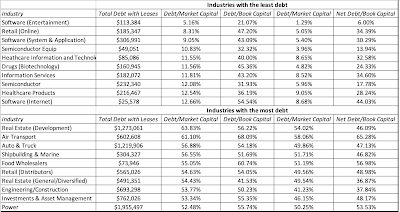

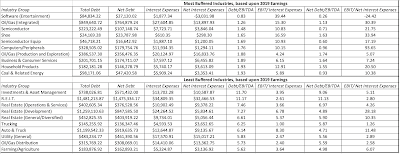

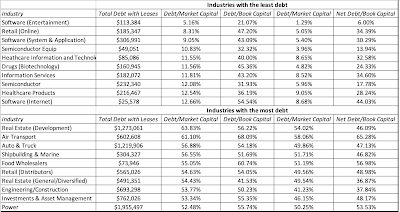

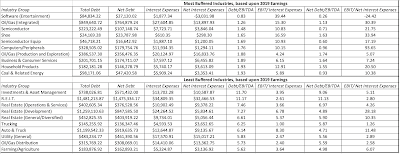

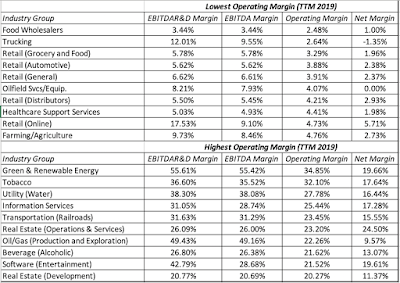

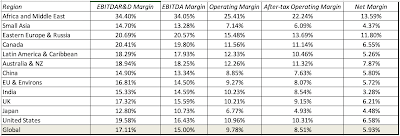

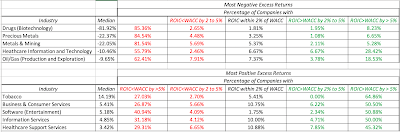

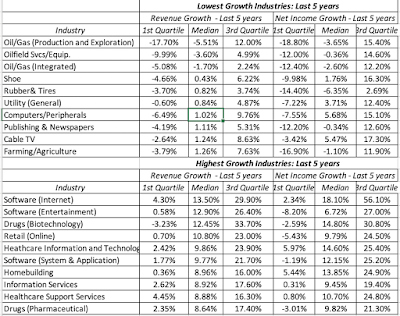

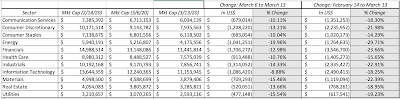

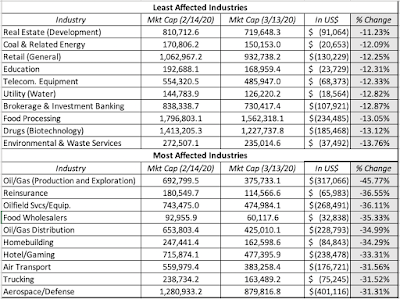

Looking at overall returns from February 14 to June 12, the worst performing regions in the world are mostly in emerging markets (India, Latin America and Africa), with the UK as the worst performing developing market, down about 20%. Breaking down the companies by sector, I look at returns across the period, broken down into two sub periods: Download dataThe sectors with double digit negative returns over the entire period are energy, utilities, real estate, industrials and financials, with the first four being punished for their capital intensity and debt dependence, and financials reflecting the fear of debt defaults. Health care shows almost no change in value over the entire period, and tech is down only 3.2%. Breaking the sectors down into industries, and looking at returns over the crisis period, I list out the ten worst and best performing industries between February 14 and June 12, 2020:

Download dataThe sectors with double digit negative returns over the entire period are energy, utilities, real estate, industrials and financials, with the first four being punished for their capital intensity and debt dependence, and financials reflecting the fear of debt defaults. Health care shows almost no change in value over the entire period, and tech is down only 3.2%. Breaking the sectors down into industries, and looking at returns over the crisis period, I list out the ten worst and best performing industries between February 14 and June 12, 2020:

Download data

Download data

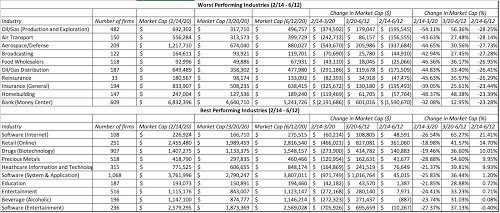

There are no surprises here, given the earlier sector assessment, with a strong representation of infrastructure and financial service companies among the worst performing sectors, and health care and technology on the best performing list.

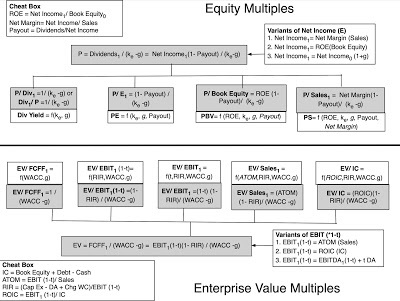

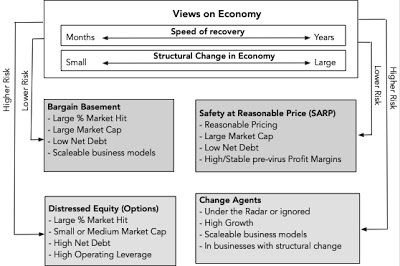

Crisis Effects across the Corporate Life CycleIn each update on the crisis, I have tried to look at a different facet of market performance, hoping to get some understanding of what the market is pricing in, and whether it makes sense. This week, I will use the concept of a corporate life cycle, a structure that I have found useful in thinking about both corporate financial questions and in valuation, and look at how this crisis has played out across the life cycle.

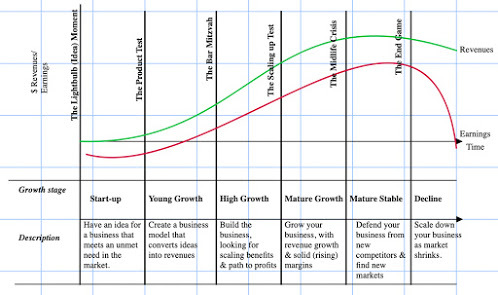

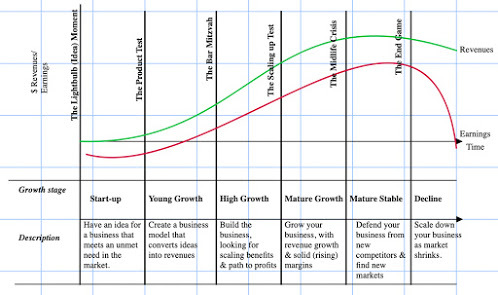

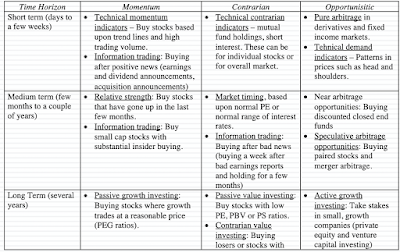

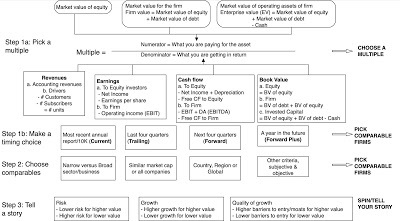

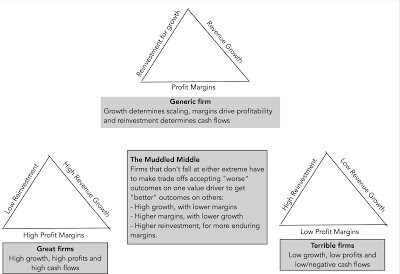

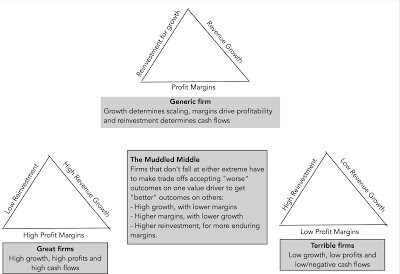

The Corporate Life CycleI believe that companies, like humans, go through a life cycle from newborn (start up) to toddler to teenager, peaking as successful growth companies, before becoming middle aged (mature) and then declining.

While there are companies that find pathways to reincarnation (IBM in 1992, Apple in 1999, Microsoft in 2013), they remain the exceptions to the rule that fighting corporate aging creates more costs than benefits. The life cycle is useful not just as a device for chronicling corporate age but also in identifying the challenges that companies face at each stage. It is also worth noting that the free cash flows, i.e., cash flows left over after taxes and reinvestment, vary as companies move through the life cycle:

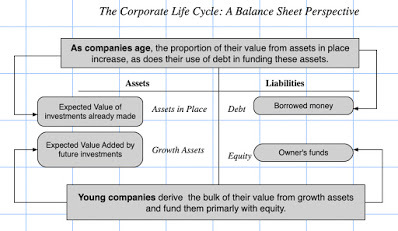

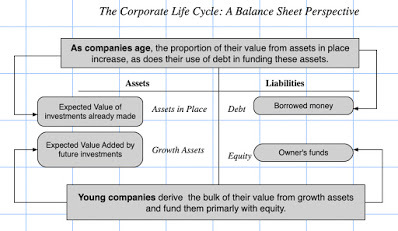

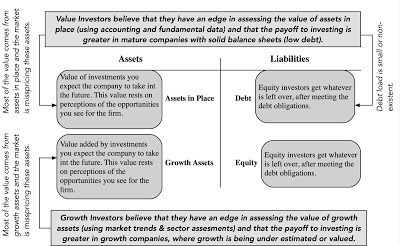

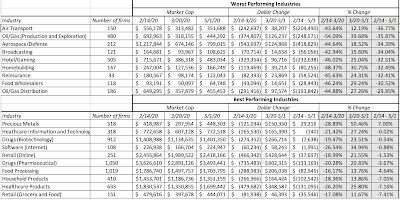

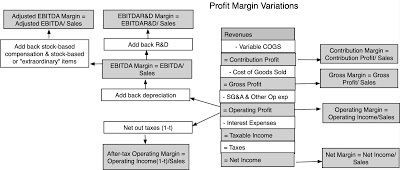

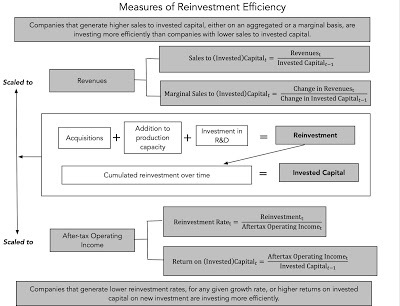

In general, negative cash flows (cash burn) are a feature of young companies, cash build ups occur as companies grow and mature, and declining companies return cash as they shrink. Finally, to understand how companies change as they move through the life cycle, I will draw on another general construct, the financial balance sheet:

Note that young companies derive their value mostly or even entirely from growth assets, i.e., the value of investments that they are expected to make in the future, and that the portion that is attributable to assets in place increases as companies age, with mature and aging firms deriving most or all of their value from existing investments. Young companies, lacking the earnings and cash flows to service debt, are also more dependent on equity to fund their businesses than mature firms.

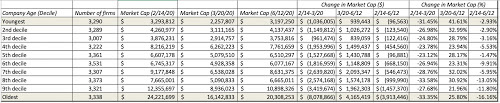

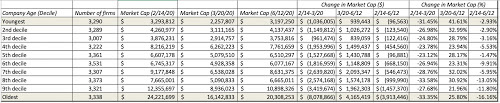

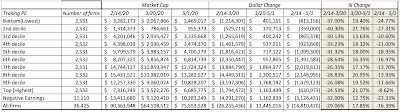

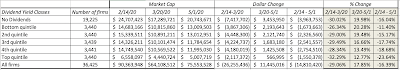

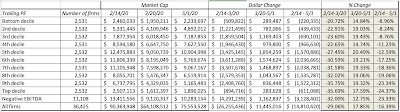

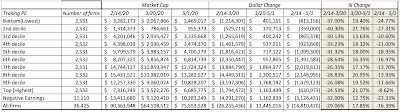

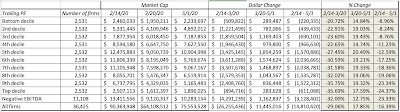

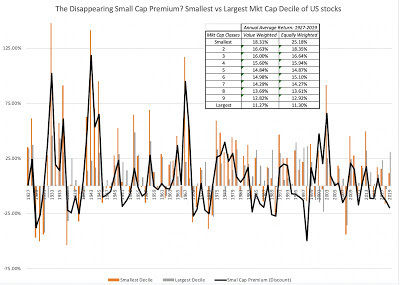

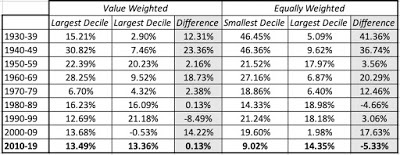

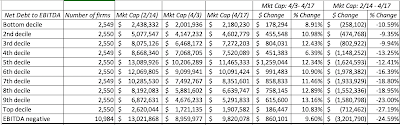

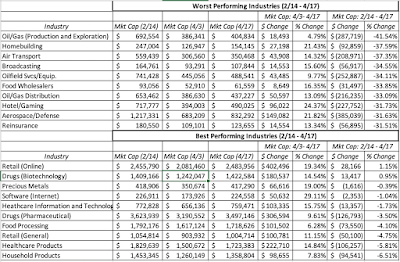

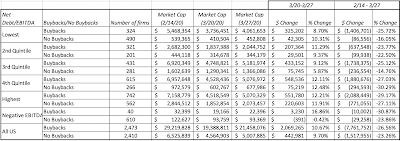

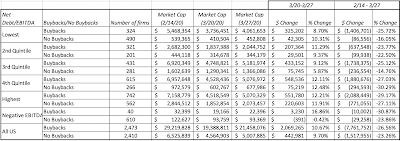

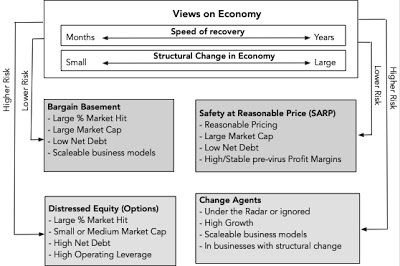

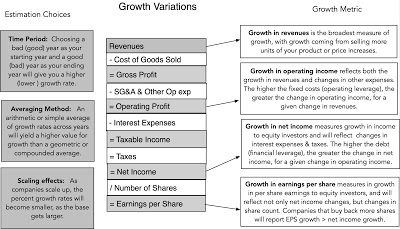

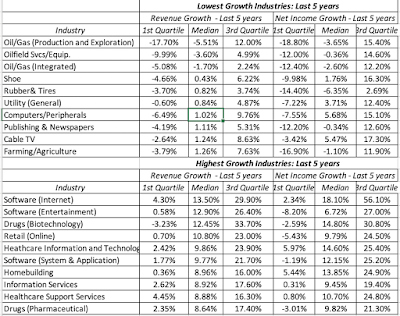

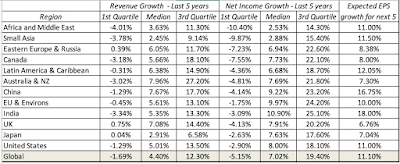

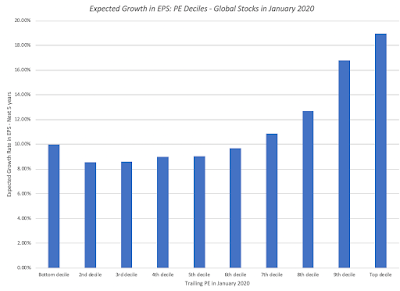

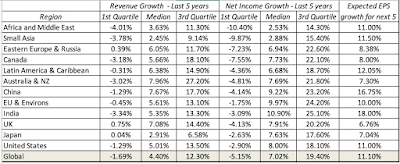

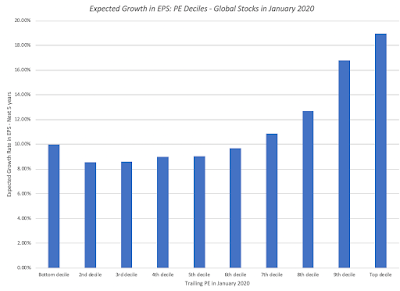

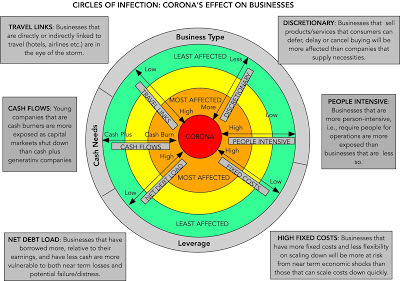

The Crisis Effect across the Life CycleA crisis tests all companies, but the dimensions on which they get tested will vary depending on where they fall in the life cycle. Start up and very young companies: For young companies, the challenge is survival, since they mostly have small or no revenues, and are money losers. They need capital to make it to the next and more lucrative phases in the life cycle, and in a crisis, access to capital (from venture capitalists or public equity) can shut down or become prohibitively expensive, as investors become more fearful. These companies will either have to shut down or sell themselves at bargain basement prices to larger, deeper-pocketed competitors.Young growth companies: For young growth companies that have turned the corner on profitability, capital access still remains critical since it is needed for future growth. Without that capital, the values of these firms will shrink towards assets in place, and in a crisis, these firms have to hunker down and scale back their growth ambitions.Mature firms: For mature firms, the bigger damage from a crisis is the punishment it metes to assets in place, as the economy slows or goes into recession, and consumers cut back on spending. The effect will be greater on companies that sell discretionary products than on companies that sell staples.Declining firms: For declining firms, especially those with substantial debt, a crisis can tip them into distress and default, especially if access to risk capital declines, and risk premiums increase. In summary, the answer to the question of which companies (young or old) get affected more in a crisis will depend on how the crisis affects the real economy and capital access. In most crises, it is access to capital that takes the early hit, with the pain from economic effects showing up more gradually. As a result, in the first parts of the crisis, it is the firms at either end of the life cycle (young companies and declining ones) that are most dependent on new capital to survive that are hurt the most, with the pain spreading more slowly to mature firms, and least to firms that sell consumer staples. How has this crisis played out in terms of damage to companies across the life cycle? Let me start with a very simplistic measure of life cycle, company age, as measured from the year of founding: Download dataThe table tells an interesting story. In the down phase (2/14-3/20), there was little distinction between younger and older firms, as firms in every age group lost about 30% of value. In the second phase from 3/20 to June 12, younger companies have seen a much more robust comeback than older firms, resulting in much lower negative returns over the entire period for younger firms (the bottom five deciles) than older ones (the top five deciles). You could argue that company age is not a composite measure of where a company falls in the life cycle, since some companies move through the life cycle faster than others. To counter this critique, I break firms down by expected revenue growth, as estimated prior to the crisis, building on the assumption that expected revenue growth should be highest for young firms and lower for firms further along in the life cycle:

Download dataThe table tells an interesting story. In the down phase (2/14-3/20), there was little distinction between younger and older firms, as firms in every age group lost about 30% of value. In the second phase from 3/20 to June 12, younger companies have seen a much more robust comeback than older firms, resulting in much lower negative returns over the entire period for younger firms (the bottom five deciles) than older ones (the top five deciles). You could argue that company age is not a composite measure of where a company falls in the life cycle, since some companies move through the life cycle faster than others. To counter this critique, I break firms down by expected revenue growth, as estimated prior to the crisis, building on the assumption that expected revenue growth should be highest for young firms and lower for firms further along in the life cycle:

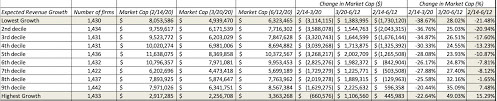

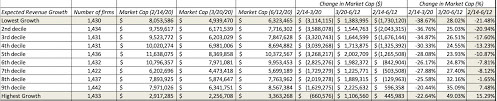

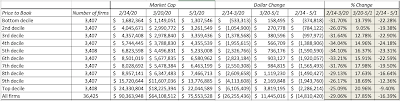

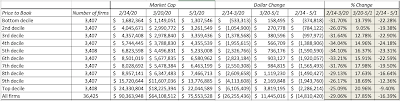

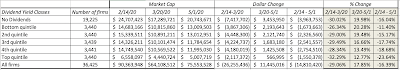

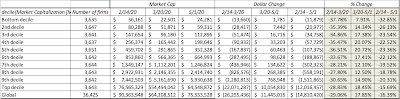

Download dataNote that expected revenue growth estimates are available for just over a third of all the firms in my sample, and across those firms, the differences are stark. Firms in the lowest revenue growth decile are down substantially over the crisis period (2/14 - 6/12) whereas the firms with the highest expected revenue growth, coming into the crisis, have seen their values increase over the same period.

Download dataNote that expected revenue growth estimates are available for just over a third of all the firms in my sample, and across those firms, the differences are stark. Firms in the lowest revenue growth decile are down substantially over the crisis period (2/14 - 6/12) whereas the firms with the highest expected revenue growth, coming into the crisis, have seen their values increase over the same period.

In summary, this crisis seems to have had a much greater negative impact on older, more mature companies than on younger, high growth ones. perhaps because it started at a time, when capital markets were buoyant and investors were eagerly taking on risk, with risk premiums in both equity and bond markets at close to decade-level lows, with a global economic shut down, with a cessation of most business activity. That shut down came with a time frame, though there was uncertainty not only about when economic activity would start up again, but how vigorously it would return. Young companies have also benefited from the fact, that after being on hold in the first few weeks of the crisis, risk capital came back in the middle of March, both in public and private markets. The big story, still unfolding, from this crisis is that access to risk capital has held up remarkably well, coming back into markets earlier and in larger magnitudes, than in prior crisis. The Fed has undoubtedly played a role in this comeback, especially with its intervention in lending markets, but it has succeeded only because it tapped a willing investor base.That access to risk capital has also benefited distressed companies at the other end of the life cycle, explaining why you have seen surges in airline stock prices and in portions of the oil sector. To those who attribute the shift to amateur investors, subject to so much scorn from market watchers, there is collectively too little capital in the hands of these investors to have caused this much of a change in markets.

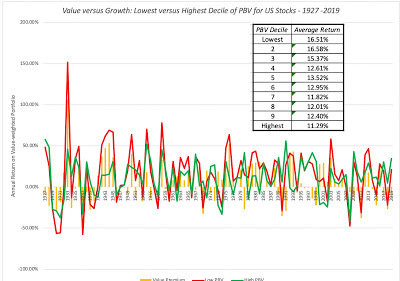

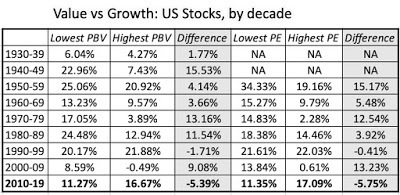

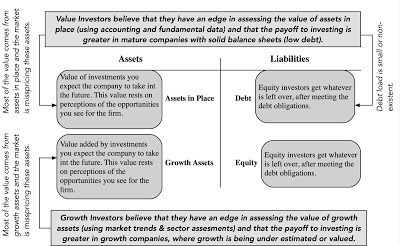

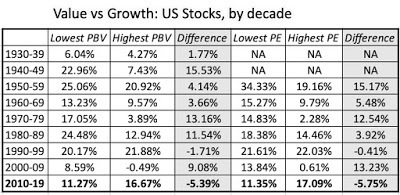

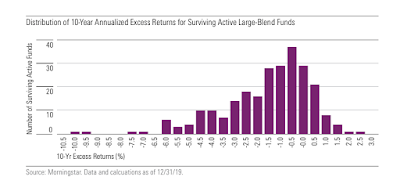

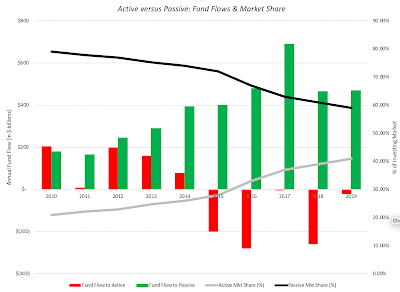

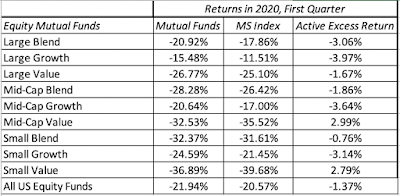

The divergence in the market treatment between young and older companies during this crisis also explains why value has underperformed growth, since value investing strategies skew towards more mature companies and growth investing is more focused on younger companies. It may also explain why so many market "pros" have been left in the dust by amateurs, since many of the former have been using scripts developed in prior crisis to decide when and where to invest, and this one has followed a different path. While value investors and pros may still be vindicated, the lesson that I would take from this crisis is that while it is true that those who do not remember history are destined to repeat it, it is also true that those who let history alone drive their investment decisions are in just as much danger.

ConclusionThe trajectory of markets in this crisis has followed the path of the virus, with markets rising and falling on news about viral breakouts in different parts of the world, and vaccines/medication to mitigate its effects. It should therefore come as no surprise that just as the virus has had its most deadly effects on the elderly and the infirm, the market is meting out its biggest punishment to mature and aging companies. As we pass the four-month mark since this crisis started roiling financial markets in the US and Europe, it is still an evolving story and there will be more twists and turns before it is done.

YouTube Video<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/NR0Blxm..." frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Data

Market data (June 12, 2020)Regional breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Country breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Sector breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Industry breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Age breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Growth breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Viral Market Update PostsA Viral Market Meltdown: Fear or Fundamentals?A Viral Market Meltdown II: Pricing or Valuing? Investing or Trading?A Viral Market Meltdown III: Clues in the Market DebrisA Viral Market Meltdown IV: Investing for a post-virus EconomyA Viral Market Meltdown V: Back to BasicsA Viral Market Meltdown VI: The Price of RiskA Viral Market Meltdown VII: Market MultiplesA Viral Market Meltdown VIII: Value vs Growth, Active vs Passive, Small Cap vs Large!A Viral Market Meltdown IX: A Do-it-Yourself S&P 500 ValuationA Viral Market Meltdown X: A Corporate Life Cycle Perspective

Updating the MarketAs with my previous updates, I will start with a chronicling of how markets have behaved in the two weeks since my last update, and overall, during the crisis. Let's start with equity indices, where we saw one week of relative stability (5/29-6/5) and a week of drama (6/5-6/12), after surges in April and May:

Download dataFor those who thought that the worst of the crisis was behind them, June 11 delivered the message that this crisis is not quite done, as the S&P 500 dropped 7%, and markets around the world followed. I have computed the returns since February 14, broken down into two time periods, with the first stretching from February 14 to March 20, and the second from March 20 to June 12. Every equity index that I list in this table dropped in the first phase, with some indices losing more than 30%, as fear stalked markets around the world. In the second phase, every index posted positive returns, with some climbing back almost to pre-crisis levels. I will return to look at equities in more detail in the next section, but as stocks were going through contortions, US treasury yields were also on the move:

Download dataFor those who thought that the worst of the crisis was behind them, June 11 delivered the message that this crisis is not quite done, as the S&P 500 dropped 7%, and markets around the world followed. I have computed the returns since February 14, broken down into two time periods, with the first stretching from February 14 to March 20, and the second from March 20 to June 12. Every equity index that I list in this table dropped in the first phase, with some indices losing more than 30%, as fear stalked markets around the world. In the second phase, every index posted positive returns, with some climbing back almost to pre-crisis levels. I will return to look at equities in more detail in the next section, but as stocks were going through contortions, US treasury yields were also on the move: Download dataUS treasury rates dropped in the first weeks of the crisis, and with 3-month yields dropping close to zero and 10-year rates declining below 1%. While it is convenient to attribute everything that happens to interest rates to the Fed, note that much of the drop in rates occurred before the Fed's two big moves, the first one on March 15, where the Fed Funds rate was cut by 0.5% (almost to zero) and a $700 billion quantitative easing plan was announced, and the second one on March 23, when the Fed lifted the cap on its easing plan and extended its role as a backstop in the corporate bond and lending markets. While treasury rates were not affected much by the Fed's actions, its entry into the corporate bond market played a key role in turning the tide, where default spreads across ratings classes had been on the rise since February 14:

Download dataUS treasury rates dropped in the first weeks of the crisis, and with 3-month yields dropping close to zero and 10-year rates declining below 1%. While it is convenient to attribute everything that happens to interest rates to the Fed, note that much of the drop in rates occurred before the Fed's two big moves, the first one on March 15, where the Fed Funds rate was cut by 0.5% (almost to zero) and a $700 billion quantitative easing plan was announced, and the second one on March 23, when the Fed lifted the cap on its easing plan and extended its role as a backstop in the corporate bond and lending markets. While treasury rates were not affected much by the Fed's actions, its entry into the corporate bond market played a key role in turning the tide, where default spreads across ratings classes had been on the rise since February 14:

Download data

Download dataDefault spreads followed the path of equities, widening significantly between February 14 and March 20, and falling back by June 12, albeit to levels higher then on February 14. The fear about how the pandemic would slow economic growth also affected commodity prices, and I chart the path of copper and oil, two commodities sensitive to global economic growth below:

Download data

Download dataAs with corporate bonds and equities, it is a tale of two periods, with commodity prices dropping between February 14 and March 20, before clawing their way back in the subsequent period. With copper, the market has retraced its entire decline, and it is now back to where it was trading at, on February 14. With oil, it is a different story, with a decline of more than 50% between February 14 and March 20 in both Brent and West Texas crude. and oil prices, notwithstanding a strong recovery between March 20 and June 12, are about 30% lower than they were on February 14. Finally, I look at gold and bitcoin, gold, because it has historically been a crisis asset and bitcoin, because it has been marketed by some as an alternative asset:

Download data

Download dataGold has held its value and is up 9.28% during the crisis, though it saw less upside during the first few weeks of this crisis than in prior ones. Bitcoin has behaved more like equity, and very risky equity at that, during this crisis, dropping almost 40% between February 14 and March 20, before recovering to close down only 10.67% by June 12.

Equities: A BreakdownIn keeping with a practice I have adopted on my prior updates, I downloaded individual stock data on 37,050 publicly traded global companies, with market capitalizations exceeding $5 million, and computed changes in market cap, by region:

Download data

Download dataLooking at overall returns from February 14 to June 12, the worst performing regions in the world are mostly in emerging markets (India, Latin America and Africa), with the UK as the worst performing developing market, down about 20%. Breaking down the companies by sector, I look at returns across the period, broken down into two sub periods:

Download dataThe sectors with double digit negative returns over the entire period are energy, utilities, real estate, industrials and financials, with the first four being punished for their capital intensity and debt dependence, and financials reflecting the fear of debt defaults. Health care shows almost no change in value over the entire period, and tech is down only 3.2%. Breaking the sectors down into industries, and looking at returns over the crisis period, I list out the ten worst and best performing industries between February 14 and June 12, 2020:

Download dataThe sectors with double digit negative returns over the entire period are energy, utilities, real estate, industrials and financials, with the first four being punished for their capital intensity and debt dependence, and financials reflecting the fear of debt defaults. Health care shows almost no change in value over the entire period, and tech is down only 3.2%. Breaking the sectors down into industries, and looking at returns over the crisis period, I list out the ten worst and best performing industries between February 14 and June 12, 2020:

Download data

Download dataThere are no surprises here, given the earlier sector assessment, with a strong representation of infrastructure and financial service companies among the worst performing sectors, and health care and technology on the best performing list.

Crisis Effects across the Corporate Life CycleIn each update on the crisis, I have tried to look at a different facet of market performance, hoping to get some understanding of what the market is pricing in, and whether it makes sense. This week, I will use the concept of a corporate life cycle, a structure that I have found useful in thinking about both corporate financial questions and in valuation, and look at how this crisis has played out across the life cycle.

The Corporate Life CycleI believe that companies, like humans, go through a life cycle from newborn (start up) to toddler to teenager, peaking as successful growth companies, before becoming middle aged (mature) and then declining.

While there are companies that find pathways to reincarnation (IBM in 1992, Apple in 1999, Microsoft in 2013), they remain the exceptions to the rule that fighting corporate aging creates more costs than benefits. The life cycle is useful not just as a device for chronicling corporate age but also in identifying the challenges that companies face at each stage. It is also worth noting that the free cash flows, i.e., cash flows left over after taxes and reinvestment, vary as companies move through the life cycle:

In general, negative cash flows (cash burn) are a feature of young companies, cash build ups occur as companies grow and mature, and declining companies return cash as they shrink. Finally, to understand how companies change as they move through the life cycle, I will draw on another general construct, the financial balance sheet:

Note that young companies derive their value mostly or even entirely from growth assets, i.e., the value of investments that they are expected to make in the future, and that the portion that is attributable to assets in place increases as companies age, with mature and aging firms deriving most or all of their value from existing investments. Young companies, lacking the earnings and cash flows to service debt, are also more dependent on equity to fund their businesses than mature firms.

The Crisis Effect across the Life CycleA crisis tests all companies, but the dimensions on which they get tested will vary depending on where they fall in the life cycle. Start up and very young companies: For young companies, the challenge is survival, since they mostly have small or no revenues, and are money losers. They need capital to make it to the next and more lucrative phases in the life cycle, and in a crisis, access to capital (from venture capitalists or public equity) can shut down or become prohibitively expensive, as investors become more fearful. These companies will either have to shut down or sell themselves at bargain basement prices to larger, deeper-pocketed competitors.Young growth companies: For young growth companies that have turned the corner on profitability, capital access still remains critical since it is needed for future growth. Without that capital, the values of these firms will shrink towards assets in place, and in a crisis, these firms have to hunker down and scale back their growth ambitions.Mature firms: For mature firms, the bigger damage from a crisis is the punishment it metes to assets in place, as the economy slows or goes into recession, and consumers cut back on spending. The effect will be greater on companies that sell discretionary products than on companies that sell staples.Declining firms: For declining firms, especially those with substantial debt, a crisis can tip them into distress and default, especially if access to risk capital declines, and risk premiums increase. In summary, the answer to the question of which companies (young or old) get affected more in a crisis will depend on how the crisis affects the real economy and capital access. In most crises, it is access to capital that takes the early hit, with the pain from economic effects showing up more gradually. As a result, in the first parts of the crisis, it is the firms at either end of the life cycle (young companies and declining ones) that are most dependent on new capital to survive that are hurt the most, with the pain spreading more slowly to mature firms, and least to firms that sell consumer staples. How has this crisis played out in terms of damage to companies across the life cycle? Let me start with a very simplistic measure of life cycle, company age, as measured from the year of founding:

Download dataThe table tells an interesting story. In the down phase (2/14-3/20), there was little distinction between younger and older firms, as firms in every age group lost about 30% of value. In the second phase from 3/20 to June 12, younger companies have seen a much more robust comeback than older firms, resulting in much lower negative returns over the entire period for younger firms (the bottom five deciles) than older ones (the top five deciles). You could argue that company age is not a composite measure of where a company falls in the life cycle, since some companies move through the life cycle faster than others. To counter this critique, I break firms down by expected revenue growth, as estimated prior to the crisis, building on the assumption that expected revenue growth should be highest for young firms and lower for firms further along in the life cycle:

Download dataThe table tells an interesting story. In the down phase (2/14-3/20), there was little distinction between younger and older firms, as firms in every age group lost about 30% of value. In the second phase from 3/20 to June 12, younger companies have seen a much more robust comeback than older firms, resulting in much lower negative returns over the entire period for younger firms (the bottom five deciles) than older ones (the top five deciles). You could argue that company age is not a composite measure of where a company falls in the life cycle, since some companies move through the life cycle faster than others. To counter this critique, I break firms down by expected revenue growth, as estimated prior to the crisis, building on the assumption that expected revenue growth should be highest for young firms and lower for firms further along in the life cycle:

Download dataNote that expected revenue growth estimates are available for just over a third of all the firms in my sample, and across those firms, the differences are stark. Firms in the lowest revenue growth decile are down substantially over the crisis period (2/14 - 6/12) whereas the firms with the highest expected revenue growth, coming into the crisis, have seen their values increase over the same period.

Download dataNote that expected revenue growth estimates are available for just over a third of all the firms in my sample, and across those firms, the differences are stark. Firms in the lowest revenue growth decile are down substantially over the crisis period (2/14 - 6/12) whereas the firms with the highest expected revenue growth, coming into the crisis, have seen their values increase over the same period. In summary, this crisis seems to have had a much greater negative impact on older, more mature companies than on younger, high growth ones. perhaps because it started at a time, when capital markets were buoyant and investors were eagerly taking on risk, with risk premiums in both equity and bond markets at close to decade-level lows, with a global economic shut down, with a cessation of most business activity. That shut down came with a time frame, though there was uncertainty not only about when economic activity would start up again, but how vigorously it would return. Young companies have also benefited from the fact, that after being on hold in the first few weeks of the crisis, risk capital came back in the middle of March, both in public and private markets. The big story, still unfolding, from this crisis is that access to risk capital has held up remarkably well, coming back into markets earlier and in larger magnitudes, than in prior crisis. The Fed has undoubtedly played a role in this comeback, especially with its intervention in lending markets, but it has succeeded only because it tapped a willing investor base.That access to risk capital has also benefited distressed companies at the other end of the life cycle, explaining why you have seen surges in airline stock prices and in portions of the oil sector. To those who attribute the shift to amateur investors, subject to so much scorn from market watchers, there is collectively too little capital in the hands of these investors to have caused this much of a change in markets.

The divergence in the market treatment between young and older companies during this crisis also explains why value has underperformed growth, since value investing strategies skew towards more mature companies and growth investing is more focused on younger companies. It may also explain why so many market "pros" have been left in the dust by amateurs, since many of the former have been using scripts developed in prior crisis to decide when and where to invest, and this one has followed a different path. While value investors and pros may still be vindicated, the lesson that I would take from this crisis is that while it is true that those who do not remember history are destined to repeat it, it is also true that those who let history alone drive their investment decisions are in just as much danger.

ConclusionThe trajectory of markets in this crisis has followed the path of the virus, with markets rising and falling on news about viral breakouts in different parts of the world, and vaccines/medication to mitigate its effects. It should therefore come as no surprise that just as the virus has had its most deadly effects on the elderly and the infirm, the market is meting out its biggest punishment to mature and aging companies. As we pass the four-month mark since this crisis started roiling financial markets in the US and Europe, it is still an evolving story and there will be more twists and turns before it is done.

YouTube Video<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/NR0Blxm..." frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Data

Market data (June 12, 2020)Regional breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Country breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Sector breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Industry breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Age breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Growth breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 12, 2020)Viral Market Update PostsA Viral Market Meltdown: Fear or Fundamentals?A Viral Market Meltdown II: Pricing or Valuing? Investing or Trading?A Viral Market Meltdown III: Clues in the Market DebrisA Viral Market Meltdown IV: Investing for a post-virus EconomyA Viral Market Meltdown V: Back to BasicsA Viral Market Meltdown VI: The Price of RiskA Viral Market Meltdown VII: Market MultiplesA Viral Market Meltdown VIII: Value vs Growth, Active vs Passive, Small Cap vs Large!A Viral Market Meltdown IX: A Do-it-Yourself S&P 500 ValuationA Viral Market Meltdown X: A Corporate Life Cycle Perspective

Published on June 19, 2020 13:55

June 4, 2020

A Viral Market Update IX: A Do-it-Yourself S&P 500 Valuation

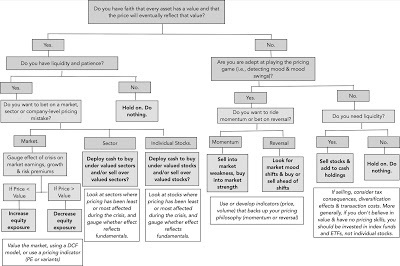

It has been close to four weeks since my last viral market update, and I could come up with a whole host of excuses for the delay, but the truth is that I have not had much to say that is original, and I am naturally lazy. That said, markets have settled in, mostly with an upward bias in these last few weeks, and the big question, as US equities climb back towards pre-crisis levels is whether the market has lost its bearings. After all, the news, whether on macroeconomic indicators or company-level earnings, is not just bad, but historically so, and it seems incongruous that markets should be rising, when consumer confidence and spending are plummeting, the ranks of the unemployed rising and professional economists are painting a picture of impending doom. There are some market gurus who are pointing to this disconnect as evidence that markets are just wrong and that a major correction is around the corner, but their credibility is undercut by the fact that many in this group have been forecasting this correction for the last decade, and with metrics (PE, CAPE, Shiller PE) that have lost their potency. I have absolutely no shame in admitting that I am not a market timer, but I do believe that embedded in market action is always a link, though sometimes tenuous, to fundamentals. In this post, I will start with my usual updates of what has transpired in the last few weeks across markets, in general, and equities, in particular. I will then revisit my framework for valuing the S&P index, which I first presented in my first viral market post on February 27 and then expanded on in subsequent posts on March 9 and March 16. While I will update my valuation of the index, given what we have learned since, I will also follow a template that I developed when I valued Tesla earlier this year, and offer a Do-it-yourself (DIY) valuation of the index.

Market UpdateMy crisis clock started on February 14, 2020, shortly after US equities hit all time highs, and in the weeks since, I have tracked the ups and downs of equity indices. Download dataBetween February 14 and March 20, it was a precipitous drop with almost equity index in the world down between 30-40%, with the Chinese markets being the exceptions, a bear market compressed into five weeks. Since March 20, though, it has been not just an up market, but one that has climbed steeply. For instance, the S&P 500 which dropped a little over 28% between February 14 and March 20, had recouped most of those losses by June 1, and is now down only 5.29% since February 14. Two emerging market indices, the Bovespa (Brazil) and the Sensex (India), and one developed market index, the CAC (France), have still lost more than 20% of their value over the period. Moving on to treasuries, the immediate effect of the crisis was a flight to US treasuries, where yields dropped across the board:

[image error]

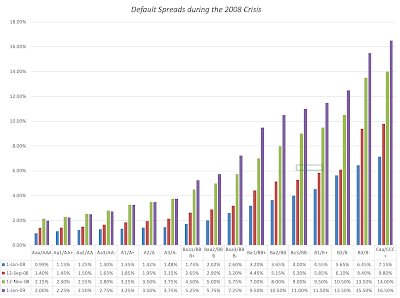

Download dataNote that almost all of the yield drop occurred before March 15, when the Fed announced its quantitative easing actions. The fear factor in the first few weeks that caused the flight to treasuries also pushed up default spreads on corporate bonds:

Download dataBetween February 14 and March 20, it was a precipitous drop with almost equity index in the world down between 30-40%, with the Chinese markets being the exceptions, a bear market compressed into five weeks. Since March 20, though, it has been not just an up market, but one that has climbed steeply. For instance, the S&P 500 which dropped a little over 28% between February 14 and March 20, had recouped most of those losses by June 1, and is now down only 5.29% since February 14. Two emerging market indices, the Bovespa (Brazil) and the Sensex (India), and one developed market index, the CAC (France), have still lost more than 20% of their value over the period. Moving on to treasuries, the immediate effect of the crisis was a flight to US treasuries, where yields dropped across the board:

[image error]

Download dataNote that almost all of the yield drop occurred before March 15, when the Fed announced its quantitative easing actions. The fear factor in the first few weeks that caused the flight to treasuries also pushed up default spreads on corporate bonds:

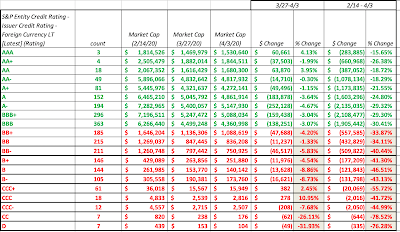

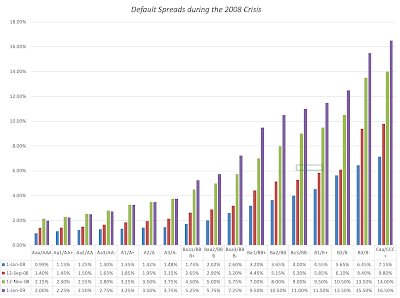

Download dataNote the dramatic surge in spreads between February 14 an April 3, with a tripling in the spread on BBB rated bonds. Like equities, corporate bonds seem to have entered a more sanguine period, with spreads on June 1, 2020, down significantly from their highs in early April. I have also been tracking two commodities, oil and copper, to measure how a global economic showdown is affecting prices:

Download dataNote the dramatic surge in spreads between February 14 an April 3, with a tripling in the spread on BBB rated bonds. Like equities, corporate bonds seem to have entered a more sanguine period, with spreads on June 1, 2020, down significantly from their highs in early April. I have also been tracking two commodities, oil and copper, to measure how a global economic showdown is affecting prices:

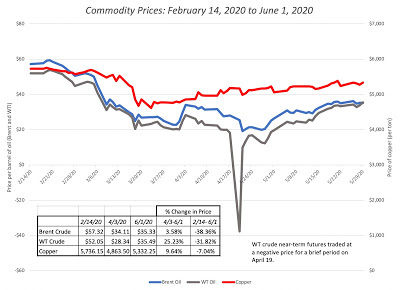

Download dataCopper prices are down about 7% on June 1, from February 14 levels, but that is as improvement from the almost 14% drop in mid-March. The oil market has had volatility that cannot just be explained by the COVID crisis, as oil prices plunged in late April, with West Texas crude dropping below zero on April 19, but even oil prices have seen recovery in the last few weeks. Finally, I look at gold and bitcoin, the former a crisis asset of long standing and the latter a new entrant.

Download dataCopper prices are down about 7% on June 1, from February 14 levels, but that is as improvement from the almost 14% drop in mid-March. The oil market has had volatility that cannot just be explained by the COVID crisis, as oil prices plunged in late April, with West Texas crude dropping below zero on April 19, but even oil prices have seen recovery in the last few weeks. Finally, I look at gold and bitcoin, the former a crisis asset of long standing and the latter a new entrant.

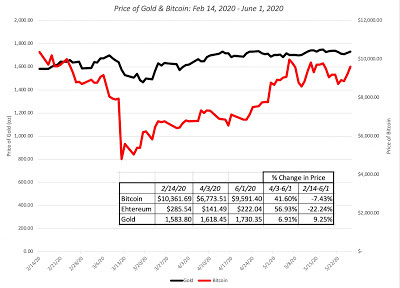

Download dataGold has held up, and is up just over 9% in the weeks since February 14, but bitcoin has behaved more like a risky speculative investment than a crisis asset, dropping more than 50% by mid March before recouping most of its losses, as equities came back April and May.

Download dataGold has held up, and is up just over 9% in the weeks since February 14, but bitcoin has behaved more like a risky speculative investment than a crisis asset, dropping more than 50% by mid March before recouping most of its losses, as equities came back April and May.

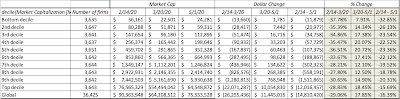

Equity BreakdownI have been downloading company-level data on publicly traded companies, at the end of each week for the last 15 weeks, and looking at changes in market capitalization across different classes of stocks. That allows me to see to not only get a more complete measure of market damage than just looking at indices, but to also use the data to double check assertions about causality.

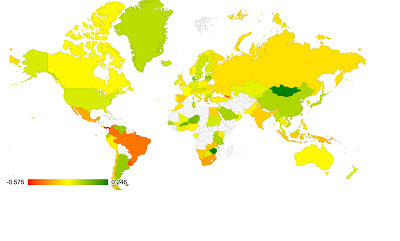

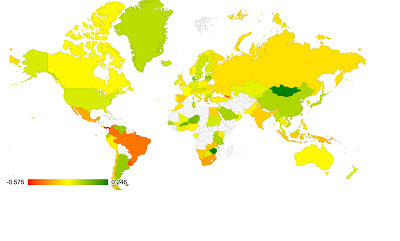

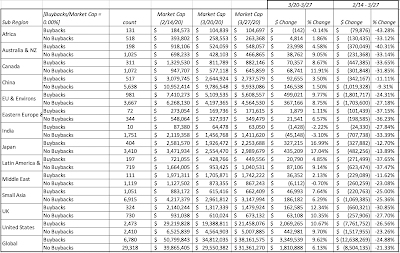

RegionThe problem with indices, especially those that contain only handfuls of stock, is that it is easy to miss changes that are occurring at smaller and lower profile companies. I used the company-level data to break down the market changes since February 14 by region: Download dataAs with the equity indices, the divide is clear, both in terms of time, with the drop occurring between February 14 and March 20 and the rise from March 20 to June 1, but also in terms of geography, with emerging markets showing bigger declines in percentage terms over the entire period. If you prefer your data on a country level, you may find this picture more revealing:

Download dataAs with the equity indices, the divide is clear, both in terms of time, with the drop occurring between February 14 and March 20 and the rise from March 20 to June 1, but also in terms of geography, with emerging markets showing bigger declines in percentage terms over the entire period. If you prefer your data on a country level, you may find this picture more revealing:

Download country-level dataThe full list of countries is available at this link. Note that all of the values in the data are in US dollar terms to allow for comparability, but that does mean that exchange rate effects will add to local stock market effects.

Download country-level dataThe full list of countries is available at this link. Note that all of the values in the data are in US dollar terms to allow for comparability, but that does mean that exchange rate effects will add to local stock market effects.

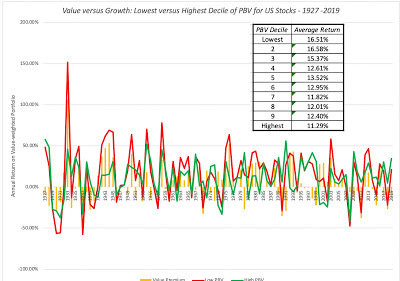

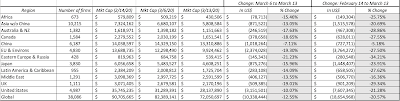

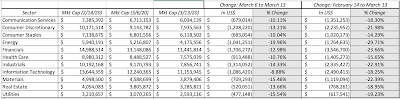

Sector/ IndustryWhile market behavior was characterized as chaotic in the first few weeks, this is clearly a market that has been orderly in how it doles out rewards and metes out punishment, as you can see in the breakdown of market cap changes by sector in the table below: Download dataAs you browse the table, note that health care, as a sector, is now in the plus column and that technology and consumer goods (both staple and discretionary) show much less damage than the rest of the market. In effect, the overall market may have recovered much of its losses, but along the way, value has been reallocated from financials, real estate and energy into health care and technology. Breaking down sectors into industries provides for more detail, and the ten best performing and ten worst performing industries between February 14 and June 1, 2020 are listed below:

Download dataAs you browse the table, note that health care, as a sector, is now in the plus column and that technology and consumer goods (both staple and discretionary) show much less damage than the rest of the market. In effect, the overall market may have recovered much of its losses, but along the way, value has been reallocated from financials, real estate and energy into health care and technology. Breaking down sectors into industries provides for more detail, and the ten best performing and ten worst performing industries between February 14 and June 1, 2020 are listed below:

Download dataThe list of best and worst performing industries has stayed stable for most of the last seven to eight weeks, but the rise in the market in the last few weeks has led to some of the best performing industries now delivering positive returns, with software, precious metal, biotech and healthcare info/tech now posting returns exceeding 10%, since February 14, 2020.

Download dataThe list of best and worst performing industries has stayed stable for most of the last seven to eight weeks, but the rise in the market in the last few weeks has led to some of the best performing industries now delivering positive returns, with software, precious metal, biotech and healthcare info/tech now posting returns exceeding 10%, since February 14, 2020.

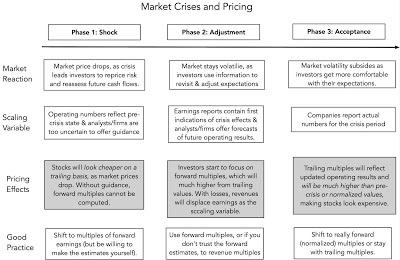

The Mystery of MarketsAs markets have recovered from their mid-March lows, there are many who are puzzled by the rise. For some, the skepticism comes from the disconnect with macroeconomic numbers that are abysmal, as unemployment claims climb into the tens of millions and consumer confidence hovers around historic lows. I will spend the first part of this section arguing that this reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of what markets try to do, and a misreading of history. For others, the question is whether markets are adequately reflecting the potential for long term damage to earnings and cash flows, as well as the cost of defaults, from this crisis. Since that answer to that question lies in the eyes of the beholder, I will provide a framework for converting your fears and hopes into numbers and a value for the market.

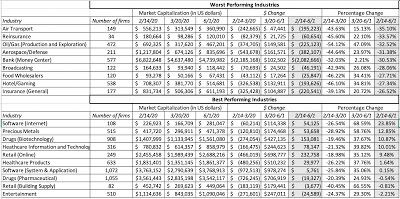

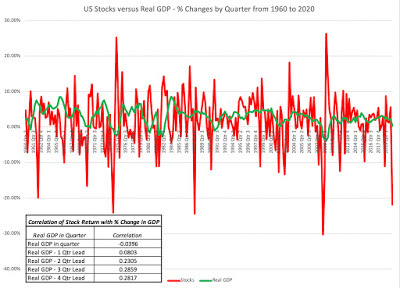

Markets and the EconomyThe notion that stock markets and economies are closely tied together is deeply held, simply because it appeals to intuition. After all, how can stocks keep going up if the economy is doing badly? While I concede that the right answer is they cannot, there are three factors that may delink the two.The first is that stocks are driven by earnings, not real growth in the economy or employment, and to the extent that companies can continue to generate income, even in stagnant or declining economies, you may see stock prices rise. The second is that the “economy” that stocks are tied to does not always have to be the domestic one, since globalization has made it possible for companies to continue to prosper in slow-growing economies. The third is time, since stock markets are prediction machines, albeit with a lot of noise and error, the link between markets and the economy, even if it exists, will be with a lag of months or longer. To those who prefer a data-based argument, the graph below plots US stock market returns against real GDP growth in the United States, using quarterly data.

Download data

Download data

Note that there is almost no correlation between stock returns and real GDP growth contemporaneously, and while the correlation grows as you look at GDP is subsequent quarters, it is still modest even four quarters ahead. If the relationship between stock returns and measures of economic activity is weak, as both logic and the data suggest, it should be even weaker right now, where every measure of economic activity is ravaged by the crisis-driven shutdown. To those in the media and the investment community who profess to be shocked by the latest economic numbers, my question is whether you are just as shocked to see your speedometer at zero, when your car is parked in the driveway, or when your pie does not bake in an oven that is not turned on? In short, there is almost nothing of use to investors from poring over current macroeconomic data, which is one reason why markets have started ignoring them. That will change, as the economy opens up again, and markets start looking at the data for cues on how quickly it is coming back to life.

Valuing the Market

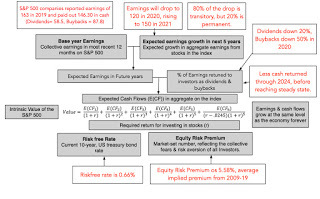

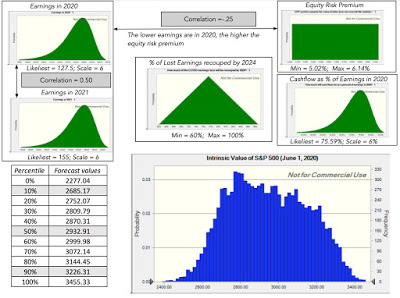

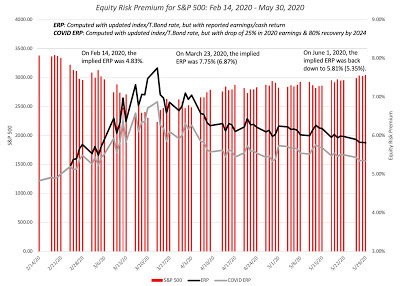

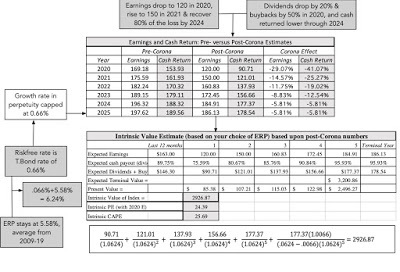

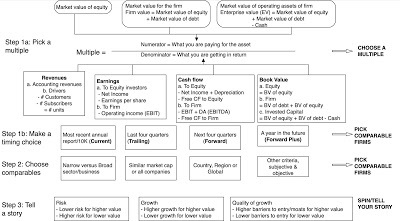

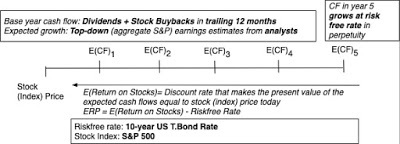

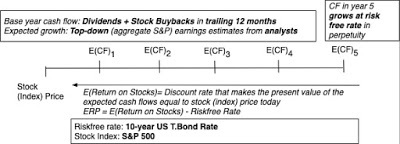

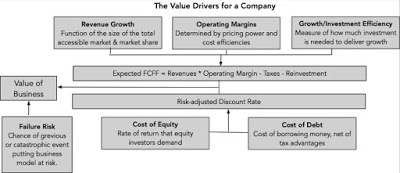

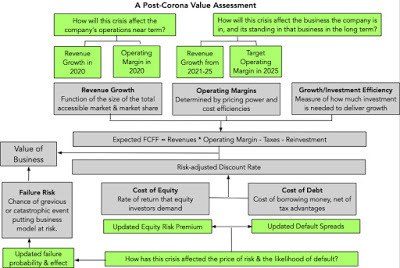

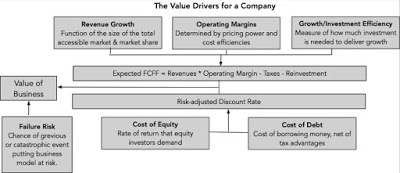

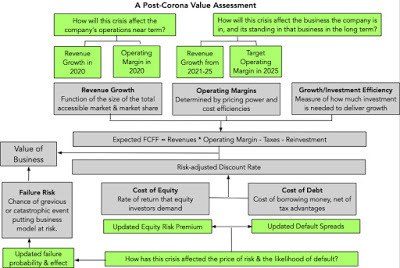

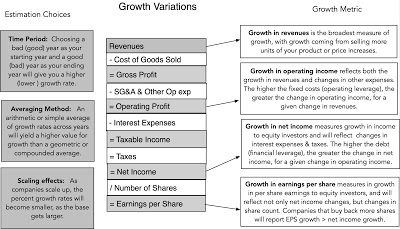

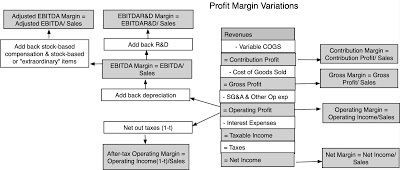

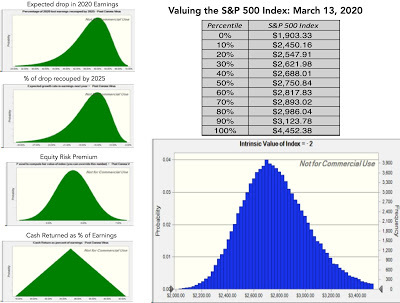

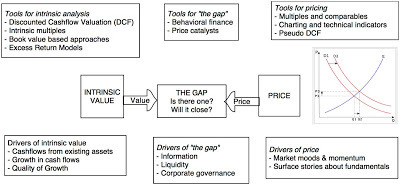

In my first viral market update, I sketched a picture of the drivers of value for the market, drawing on fundamentals. I revisited that picture and tweaked it to reflect the uncertainties that investors face about the future, broke down into near term (2020 & 2021) and the long term (in the years through 2024):

[image error]

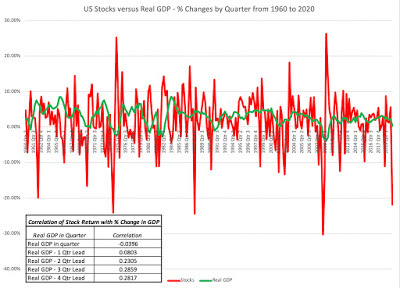

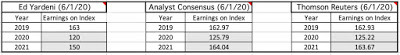

While the picture looks daunting and your estimates are fraught with uncertainty, we are now in a better position to estimate the effects than even a few weeks ago:Earnings and Growth: In 2019, the companies in the S&P 500 reported 163 in earnings, and analysts were forecasting modest growth of about 4% over the next five years, prior to the crisis. It is beyond debate that the economic shut down will be devastating for earnings in 2020, with the damage spilling over in 2021. In my valuation in March 2020, there was almost no information on the extent of this damage, but as companies have reported first quarter earnings, we are getting. preliminary estimates of future earnings. In the picture below, I look at three sets of predictions from analysts who trace the index: Sources: Yardeni, Thomson Reuters, FactsetI follow up by also reporting on what market strategists at major banks are forecasting:

Sources: Yardeni, Thomson Reuters, FactsetI follow up by also reporting on what market strategists at major banks are forecasting:

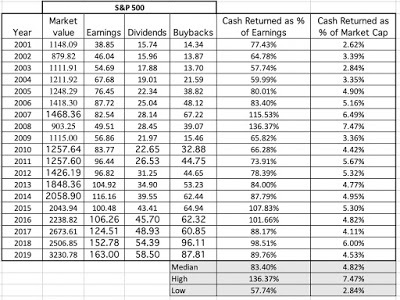

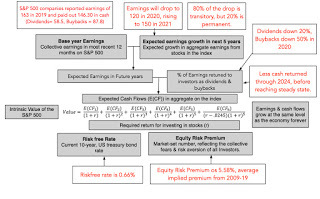

As of right now, there seems to be only nascent attempts to forecast long term damage to earnings, but a consensus is forming that there will be some.Cash Return: In 2019, companies in the index returned 146.30 in cash to stockholders, 57.5 in dividends and 87.8 in buybacks, amounting to 89.75% of earnings in that year. This represented a continuation of a trend through the decade of increasing buybacks and cash return:

As of right now, there seems to be only nascent attempts to forecast long term damage to earnings, but a consensus is forming that there will be some.Cash Return: In 2019, companies in the index returned 146.30 in cash to stockholders, 57.5 in dividends and 87.8 in buybacks, amounting to 89.75% of earnings in that year. This represented a continuation of a trend through the decade of increasing buybacks and cash return:

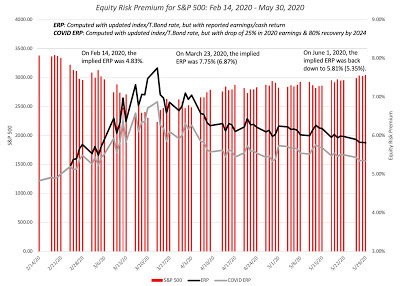

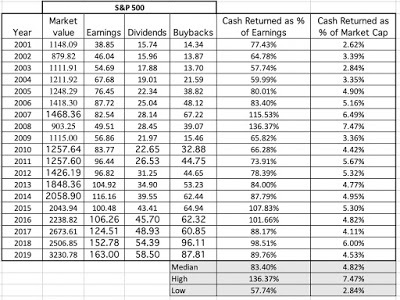

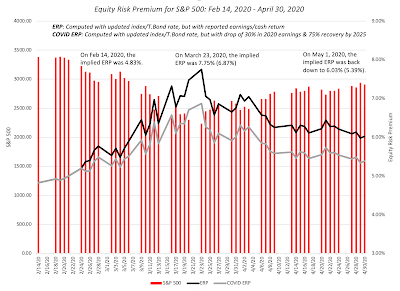

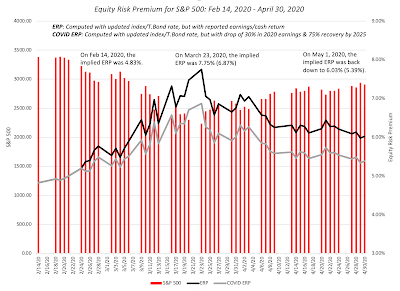

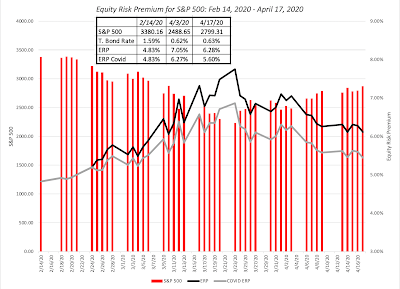

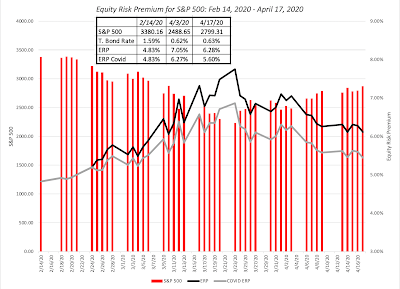

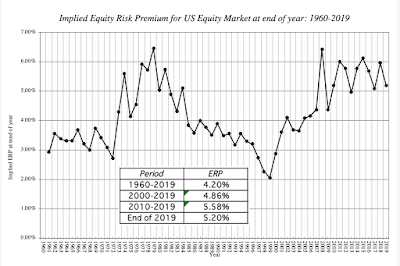

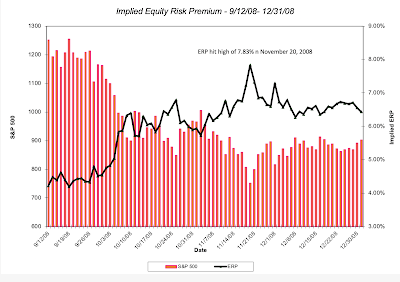

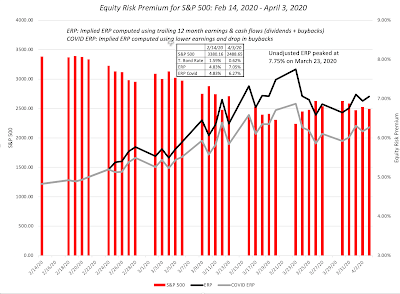

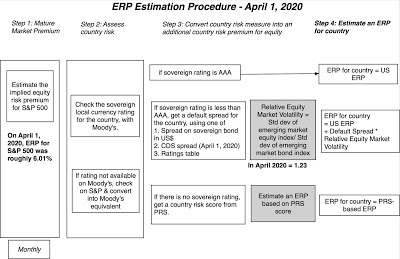

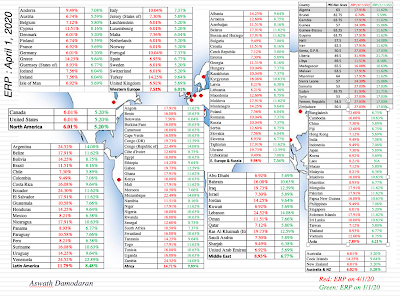

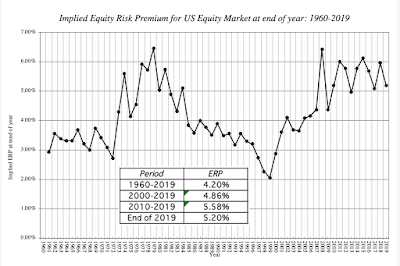

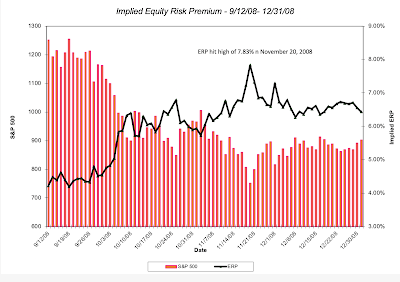

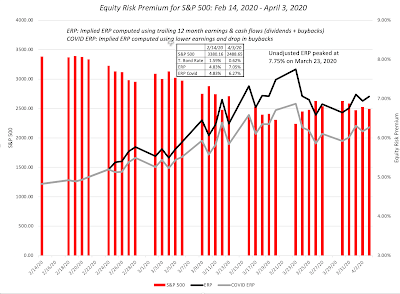

As with earnings, this crisis will result in cash flow shocks, and dividends and buybacks will drop this year. Given that dividends tend to be stickier than buybacks, the drop will be lower fro the former than the latter. Analysts vary on how much, though, with a range of a drop of 30-70% in buybacks and 10-30% in dividends.Risk: Every crisis has consequences for risk premiums, as I noted in this post, and it is for that reason that I have been updating equity risk premiums, by day, since February 14.

As with earnings, this crisis will result in cash flow shocks, and dividends and buybacks will drop this year. Given that dividends tend to be stickier than buybacks, the drop will be lower fro the former than the latter. Analysts vary on how much, though, with a range of a drop of 30-70% in buybacks and 10-30% in dividends.Risk: Every crisis has consequences for risk premiums, as I noted in this post, and it is for that reason that I have been updating equity risk premiums, by day, since February 14.

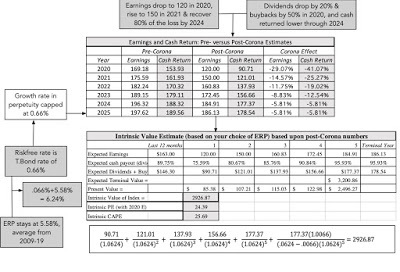

Add captionIn the early weeks of this crisis, equity risk premiums soared, peaking at more than 7% in mid-March, and have steadily dropping since, though at 5.3-5.5% on June 1, they remain above pre-crisis levels.Using this information, I made my best judgments, assuming that earnings for the S&P 500 will be 120 in 2020 and 150 in 2021, at the more conservative end of the analyst estimates, and that dividends and buybacks would drop in 2020, the former by 20% and the latter by 50%. I also assume that companies will return far less cash in future years, partly in response to the crisis:

Add captionIn the early weeks of this crisis, equity risk premiums soared, peaking at more than 7% in mid-March, and have steadily dropping since, though at 5.3-5.5% on June 1, they remain above pre-crisis levels.Using this information, I made my best judgments, assuming that earnings for the S&P 500 will be 120 in 2020 and 150 in 2021, at the more conservative end of the analyst estimates, and that dividends and buybacks would drop in 2020, the former by 20% and the latter by 50%. I also assume that companies will return far less cash in future years, partly in response to the crisis:

With these assumptions, I can value the index and I capture the valuation in the picture below. My estimated value for the index is about 2926, which would lead to a judgment that the index was over valued by about 6% (based upon the level on June 1, 2020).

With these assumptions, I can value the index and I capture the valuation in the picture below. My estimated value for the index is about 2926, which would lead to a judgment that the index was over valued by about 6% (based upon the level on June 1, 2020).

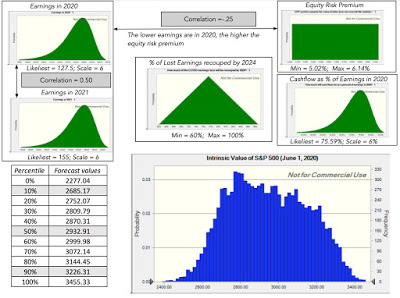

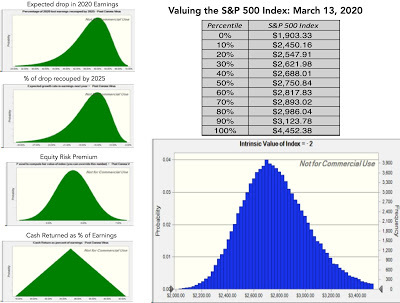

As with my March 2020 valuation, I am fully aware that my numbers are just a reflection of my story and that each of the inputs has a range around it, and I have brought in that uncertainty into a simulation below:

As with my March 2020 valuation, I am fully aware that my numbers are just a reflection of my story and that each of the inputs has a range around it, and I have brought in that uncertainty into a simulation below:

Download simulation results (Oracle Crystal Ball used in simulation)Note that I have centered the simulations around the median estimates of earnings for 2020 and 2021 from analysts, while building in the range in the estimates into the distributions. The median value from the simulation is 2932. On June 1, the S&P 500 was trading at close to 3100, putting it near the 80th percentile of the distribution, bolstering the "market has gotten ahead of itself" camp, but there is something here for everyone. If you are more optimistic about earnings in 2020 and 2021 than the the median analyst, and about how quickly and completely the market will recover from the crisis shock, you will arrive at a higher value than mine. If you are more pessimistic about the future, perhaps because you think the market is under estimating the likelihood of a second wave of shutdowns or a surge in company defaults, your valuations will be much lower.

Download simulation results (Oracle Crystal Ball used in simulation)Note that I have centered the simulations around the median estimates of earnings for 2020 and 2021 from analysts, while building in the range in the estimates into the distributions. The median value from the simulation is 2932. On June 1, the S&P 500 was trading at close to 3100, putting it near the 80th percentile of the distribution, bolstering the "market has gotten ahead of itself" camp, but there is something here for everyone. If you are more optimistic about earnings in 2020 and 2021 than the the median analyst, and about how quickly and completely the market will recover from the crisis shock, you will arrive at a higher value than mine. If you are more pessimistic about the future, perhaps because you think the market is under estimating the likelihood of a second wave of shutdowns or a surge in company defaults, your valuations will be much lower.

In all of this discussion, you will note that I have not mentioned the Fed, and to those who are Fed-focused, it may seem like I am ignoring the elephant in the room. I have argued, for much of the last decade, that analysts and investors over estimate the effect that the Fed has on markets. To the counter that it is low interest rates that are keeping the index level high, my response is that low interest rates cut both ways, first by lowering the discount rate (and thus increasing value) but also by signaling much lower growth in the long term (which I capture by lowering growth in perpetuity to the risk free rate). In fact, in my valuation spreadsheet, I offer the option of raising interest rates to what you may believe are more normal levels over time, and you can check out the effect on value, and don't be surprised if it is not as large as you expect it to be, since I also adjust growth rates and equity risk premiums to reflect changed rates. In fact, use the spreadsheet to and make your disagreements with me explicit, come up with your value for the index, and let's get a crowd valuation of the S&P 500 going. (It is a google shared spreadsheet, where you can enter your estimated value for the index).

Bottom Line

Every investor has a narrative, sometimes explicit and sometimes implicit, about how the economy and markets will evolve over time. Markets reflect a collective narrative across investors, and there are times when your narrative will be at odds with that of the market. It is during those times that you will feel the urge to label markets as crazy or irrational, and to view yourself as the last sane investor left on the planet. While I understand that urge, it is my experience that projecting your personal fears and hopes on to the market, and then getting angry when the market responds differently is a recipe for frustration and dysfunctional investing. That is not to say that markets cannot be wrong, but even if they are, a dose of humility is always in order, and there is always something that can be learned fro market movements. Right now, it is true that markets are collectively more upbeat about the future than most economists/market experts, but given their relative track records over time, are you really more willing to trust the latter? I most certainly am not!

YouTube Videos

Data

Market data (June 1, 2020)Regional breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 1, 2020)Country breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 1, 2020)Sector breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 1, 2020)Industry breakdown - Market Changes and Pricing (June 1, 2020)Equity Risk Premium, by day (Updated through June 1, 2020)Spreadsheets

Spreadsheet to value the index (June 1, 2020)Simulation results for S&P 500 valuation (June 1, 2020)Google Shared Spreadsheet (for your S&P 500 valuations)Google Shared SpreadsheetViral Market Update PostsA Viral Market Meltdown: Fear or Fundamentals?A Viral Market Meltdown II: Pricing or Valuing? Investing or Trading?A Viral Market Meltdown III: Clues in the Market DebrisA Viral Market Meltdown IV: Investing for a post-virus EconomyA Viral Market Meltdown V: Back to BasicsA Viral Market Meltdown VI: The Price of RiskA Viral Market Meltdown VII: Market MultiplesA Viral Market Meltdown VIII: Value vs Growth, Active vs Passive, Small Cap vs Large!A Viral Market Meltdown IX: A Do-it-Yourself S&P 500 Valuation

Market UpdateMy crisis clock started on February 14, 2020, shortly after US equities hit all time highs, and in the weeks since, I have tracked the ups and downs of equity indices.

Download dataBetween February 14 and March 20, it was a precipitous drop with almost equity index in the world down between 30-40%, with the Chinese markets being the exceptions, a bear market compressed into five weeks. Since March 20, though, it has been not just an up market, but one that has climbed steeply. For instance, the S&P 500 which dropped a little over 28% between February 14 and March 20, had recouped most of those losses by June 1, and is now down only 5.29% since February 14. Two emerging market indices, the Bovespa (Brazil) and the Sensex (India), and one developed market index, the CAC (France), have still lost more than 20% of their value over the period. Moving on to treasuries, the immediate effect of the crisis was a flight to US treasuries, where yields dropped across the board:

[image error]

Download dataNote that almost all of the yield drop occurred before March 15, when the Fed announced its quantitative easing actions. The fear factor in the first few weeks that caused the flight to treasuries also pushed up default spreads on corporate bonds:

Download dataBetween February 14 and March 20, it was a precipitous drop with almost equity index in the world down between 30-40%, with the Chinese markets being the exceptions, a bear market compressed into five weeks. Since March 20, though, it has been not just an up market, but one that has climbed steeply. For instance, the S&P 500 which dropped a little over 28% between February 14 and March 20, had recouped most of those losses by June 1, and is now down only 5.29% since February 14. Two emerging market indices, the Bovespa (Brazil) and the Sensex (India), and one developed market index, the CAC (France), have still lost more than 20% of their value over the period. Moving on to treasuries, the immediate effect of the crisis was a flight to US treasuries, where yields dropped across the board:

[image error]

Download dataNote that almost all of the yield drop occurred before March 15, when the Fed announced its quantitative easing actions. The fear factor in the first few weeks that caused the flight to treasuries also pushed up default spreads on corporate bonds:

Download dataNote the dramatic surge in spreads between February 14 an April 3, with a tripling in the spread on BBB rated bonds. Like equities, corporate bonds seem to have entered a more sanguine period, with spreads on June 1, 2020, down significantly from their highs in early April. I have also been tracking two commodities, oil and copper, to measure how a global economic showdown is affecting prices:

Download dataNote the dramatic surge in spreads between February 14 an April 3, with a tripling in the spread on BBB rated bonds. Like equities, corporate bonds seem to have entered a more sanguine period, with spreads on June 1, 2020, down significantly from their highs in early April. I have also been tracking two commodities, oil and copper, to measure how a global economic showdown is affecting prices:

Download dataCopper prices are down about 7% on June 1, from February 14 levels, but that is as improvement from the almost 14% drop in mid-March. The oil market has had volatility that cannot just be explained by the COVID crisis, as oil prices plunged in late April, with West Texas crude dropping below zero on April 19, but even oil prices have seen recovery in the last few weeks. Finally, I look at gold and bitcoin, the former a crisis asset of long standing and the latter a new entrant.

Download dataCopper prices are down about 7% on June 1, from February 14 levels, but that is as improvement from the almost 14% drop in mid-March. The oil market has had volatility that cannot just be explained by the COVID crisis, as oil prices plunged in late April, with West Texas crude dropping below zero on April 19, but even oil prices have seen recovery in the last few weeks. Finally, I look at gold and bitcoin, the former a crisis asset of long standing and the latter a new entrant.

Download dataGold has held up, and is up just over 9% in the weeks since February 14, but bitcoin has behaved more like a risky speculative investment than a crisis asset, dropping more than 50% by mid March before recouping most of its losses, as equities came back April and May.

Download dataGold has held up, and is up just over 9% in the weeks since February 14, but bitcoin has behaved more like a risky speculative investment than a crisis asset, dropping more than 50% by mid March before recouping most of its losses, as equities came back April and May.Equity BreakdownI have been downloading company-level data on publicly traded companies, at the end of each week for the last 15 weeks, and looking at changes in market capitalization across different classes of stocks. That allows me to see to not only get a more complete measure of market damage than just looking at indices, but to also use the data to double check assertions about causality.

RegionThe problem with indices, especially those that contain only handfuls of stock, is that it is easy to miss changes that are occurring at smaller and lower profile companies. I used the company-level data to break down the market changes since February 14 by region:

Download dataAs with the equity indices, the divide is clear, both in terms of time, with the drop occurring between February 14 and March 20 and the rise from March 20 to June 1, but also in terms of geography, with emerging markets showing bigger declines in percentage terms over the entire period. If you prefer your data on a country level, you may find this picture more revealing:

Download dataAs with the equity indices, the divide is clear, both in terms of time, with the drop occurring between February 14 and March 20 and the rise from March 20 to June 1, but also in terms of geography, with emerging markets showing bigger declines in percentage terms over the entire period. If you prefer your data on a country level, you may find this picture more revealing:

Download country-level dataThe full list of countries is available at this link. Note that all of the values in the data are in US dollar terms to allow for comparability, but that does mean that exchange rate effects will add to local stock market effects.

Download country-level dataThe full list of countries is available at this link. Note that all of the values in the data are in US dollar terms to allow for comparability, but that does mean that exchange rate effects will add to local stock market effects.Sector/ IndustryWhile market behavior was characterized as chaotic in the first few weeks, this is clearly a market that has been orderly in how it doles out rewards and metes out punishment, as you can see in the breakdown of market cap changes by sector in the table below:

Download dataAs you browse the table, note that health care, as a sector, is now in the plus column and that technology and consumer goods (both staple and discretionary) show much less damage than the rest of the market. In effect, the overall market may have recovered much of its losses, but along the way, value has been reallocated from financials, real estate and energy into health care and technology. Breaking down sectors into industries provides for more detail, and the ten best performing and ten worst performing industries between February 14 and June 1, 2020 are listed below:

Download dataAs you browse the table, note that health care, as a sector, is now in the plus column and that technology and consumer goods (both staple and discretionary) show much less damage than the rest of the market. In effect, the overall market may have recovered much of its losses, but along the way, value has been reallocated from financials, real estate and energy into health care and technology. Breaking down sectors into industries provides for more detail, and the ten best performing and ten worst performing industries between February 14 and June 1, 2020 are listed below:

Download dataThe list of best and worst performing industries has stayed stable for most of the last seven to eight weeks, but the rise in the market in the last few weeks has led to some of the best performing industries now delivering positive returns, with software, precious metal, biotech and healthcare info/tech now posting returns exceeding 10%, since February 14, 2020.

Download dataThe list of best and worst performing industries has stayed stable for most of the last seven to eight weeks, but the rise in the market in the last few weeks has led to some of the best performing industries now delivering positive returns, with software, precious metal, biotech and healthcare info/tech now posting returns exceeding 10%, since February 14, 2020. The Mystery of MarketsAs markets have recovered from their mid-March lows, there are many who are puzzled by the rise. For some, the skepticism comes from the disconnect with macroeconomic numbers that are abysmal, as unemployment claims climb into the tens of millions and consumer confidence hovers around historic lows. I will spend the first part of this section arguing that this reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of what markets try to do, and a misreading of history. For others, the question is whether markets are adequately reflecting the potential for long term damage to earnings and cash flows, as well as the cost of defaults, from this crisis. Since that answer to that question lies in the eyes of the beholder, I will provide a framework for converting your fears and hopes into numbers and a value for the market.

Markets and the EconomyThe notion that stock markets and economies are closely tied together is deeply held, simply because it appeals to intuition. After all, how can stocks keep going up if the economy is doing badly? While I concede that the right answer is they cannot, there are three factors that may delink the two.The first is that stocks are driven by earnings, not real growth in the economy or employment, and to the extent that companies can continue to generate income, even in stagnant or declining economies, you may see stock prices rise. The second is that the “economy” that stocks are tied to does not always have to be the domestic one, since globalization has made it possible for companies to continue to prosper in slow-growing economies. The third is time, since stock markets are prediction machines, albeit with a lot of noise and error, the link between markets and the economy, even if it exists, will be with a lag of months or longer. To those who prefer a data-based argument, the graph below plots US stock market returns against real GDP growth in the United States, using quarterly data.

Download data

Download dataNote that there is almost no correlation between stock returns and real GDP growth contemporaneously, and while the correlation grows as you look at GDP is subsequent quarters, it is still modest even four quarters ahead. If the relationship between stock returns and measures of economic activity is weak, as both logic and the data suggest, it should be even weaker right now, where every measure of economic activity is ravaged by the crisis-driven shutdown. To those in the media and the investment community who profess to be shocked by the latest economic numbers, my question is whether you are just as shocked to see your speedometer at zero, when your car is parked in the driveway, or when your pie does not bake in an oven that is not turned on? In short, there is almost nothing of use to investors from poring over current macroeconomic data, which is one reason why markets have started ignoring them. That will change, as the economy opens up again, and markets start looking at the data for cues on how quickly it is coming back to life.

Valuing the Market

In my first viral market update, I sketched a picture of the drivers of value for the market, drawing on fundamentals. I revisited that picture and tweaked it to reflect the uncertainties that investors face about the future, broke down into near term (2020 & 2021) and the long term (in the years through 2024):

[image error]

While the picture looks daunting and your estimates are fraught with uncertainty, we are now in a better position to estimate the effects than even a few weeks ago:Earnings and Growth: In 2019, the companies in the S&P 500 reported 163 in earnings, and analysts were forecasting modest growth of about 4% over the next five years, prior to the crisis. It is beyond debate that the economic shut down will be devastating for earnings in 2020, with the damage spilling over in 2021. In my valuation in March 2020, there was almost no information on the extent of this damage, but as companies have reported first quarter earnings, we are getting. preliminary estimates of future earnings. In the picture below, I look at three sets of predictions from analysts who trace the index:

Sources: Yardeni, Thomson Reuters, FactsetI follow up by also reporting on what market strategists at major banks are forecasting:

Sources: Yardeni, Thomson Reuters, FactsetI follow up by also reporting on what market strategists at major banks are forecasting:

As of right now, there seems to be only nascent attempts to forecast long term damage to earnings, but a consensus is forming that there will be some.Cash Return: In 2019, companies in the index returned 146.30 in cash to stockholders, 57.5 in dividends and 87.8 in buybacks, amounting to 89.75% of earnings in that year. This represented a continuation of a trend through the decade of increasing buybacks and cash return:

As of right now, there seems to be only nascent attempts to forecast long term damage to earnings, but a consensus is forming that there will be some.Cash Return: In 2019, companies in the index returned 146.30 in cash to stockholders, 57.5 in dividends and 87.8 in buybacks, amounting to 89.75% of earnings in that year. This represented a continuation of a trend through the decade of increasing buybacks and cash return:

As with earnings, this crisis will result in cash flow shocks, and dividends and buybacks will drop this year. Given that dividends tend to be stickier than buybacks, the drop will be lower fro the former than the latter. Analysts vary on how much, though, with a range of a drop of 30-70% in buybacks and 10-30% in dividends.Risk: Every crisis has consequences for risk premiums, as I noted in this post, and it is for that reason that I have been updating equity risk premiums, by day, since February 14.

As with earnings, this crisis will result in cash flow shocks, and dividends and buybacks will drop this year. Given that dividends tend to be stickier than buybacks, the drop will be lower fro the former than the latter. Analysts vary on how much, though, with a range of a drop of 30-70% in buybacks and 10-30% in dividends.Risk: Every crisis has consequences for risk premiums, as I noted in this post, and it is for that reason that I have been updating equity risk premiums, by day, since February 14.

Add captionIn the early weeks of this crisis, equity risk premiums soared, peaking at more than 7% in mid-March, and have steadily dropping since, though at 5.3-5.5% on June 1, they remain above pre-crisis levels.Using this information, I made my best judgments, assuming that earnings for the S&P 500 will be 120 in 2020 and 150 in 2021, at the more conservative end of the analyst estimates, and that dividends and buybacks would drop in 2020, the former by 20% and the latter by 50%. I also assume that companies will return far less cash in future years, partly in response to the crisis: