Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 10

October 4, 2021

The Indian Smartphone Revolution: Paytm's Coming of Age IPO!

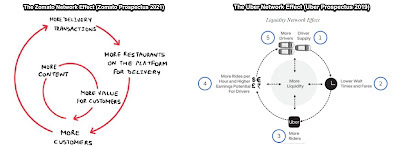

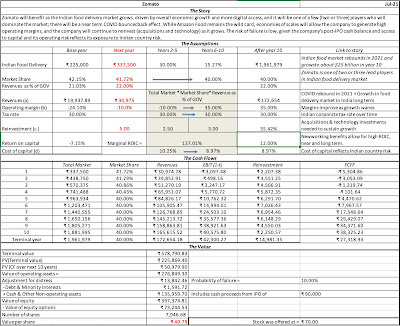

A few weeks ago, I valued Zomato, the Indian online food delivery company, just prior to its IPO, and argued that the excitement about its potential was tied to the potential for growth in India and the shifting habits of Indian consumers. Since its public offering, Zomato's stock price has reflected that excitement, more than doubling from its offering price of 74 rupees per share. Waiting in the wings for its public debut, is Paytm, a company that in many ways is even more closely tied to India's macro story, drawing on the growth of online commerce in India and a willingness of Indian consumers to use mobile payment mechanisms. In this post, I will look at the levers that drive Paytm's value, and you can make your judgments on where you think this offering will lead in terms of valuation and pricing.

Setting the Table

As the Paytm IPO speeds to offering date, it is worth looking back at its relatively short history as a company, and how much change has been packed into that period. Since so much of Paytm’s success has been driven by the rise if smart phone usage among Indian consumers, and the concurrent rise in mobile payments for goods and services, I will start with a review of that rise, before looking at how Paytm has put itself in position to take advantage of that market shift.

The Rise of the Indian Smartphone User

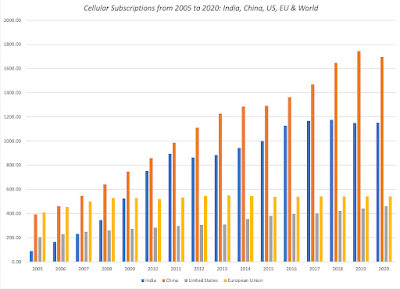

India was late to join the smart phone party, held back both by the relative expensiveness of these devices, as well as the absence of affordable and reliable cell service in much of the country. In 2010, fewer than 2% of Indians had smart phones, with most of them being well off and living in urban areas. In the decade since, that has changed, as the smart phone market has exploded to reach hundreds of millions of Indians in 2020.

Source: World Bank Database

Source: World Bank DatabaseEntering 2021, more than 500 million Indians had smart phones, making it the second largest smartphone market in the world (after China), but its penetration rate of less than 50% of the market gave it more room to grow. There are multiple forces that have contributed to this shift, but two stand out.

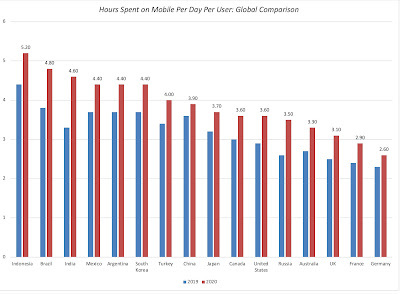

The first is that the costs of smartphones have decreased, and especially so in India, as technology and competition have worked their magic. In particular, the entry of Chinese brands, with Xiaomi and Vivo leading the charge, played a major role in making smartphones more affordable to Indians.The second is that cell service costs have also dropped, and in India, the drop in costs has been precipitous, after Reliance Jio entered the game in 2016, and quickly acquired 100 million subscribers by offering free voice and data calls over its 4G network. Today, Jio has more than 400 million subscribers, and while it remains a lightning rod for criticism, it is undeniable that it has played a major role in the evolution of the market. As smart phones have become ubiquitous in India, their usage has soared, partly because they are the only digital devices that many Indians have available to them to get online, and thus use to access social media, entertainment and shopping. By 2020, Indians ranked third in the world in how much time they were spending per day on their phones, with COVID contributing to a surge in that year: App Annie, State of Mobile 2021

App Annie, State of Mobile 2021

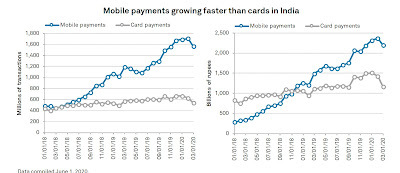

Access to these smartphones, in conjunction with poor banking outreach in India, has created the perfect storm for a surge in mobile payments in India, and this graph bears out this trend:

S&P, 2020 India Mobile Payments Market Report

S&P, 2020 India Mobile Payments Market Report

Within the mobile payment space, there was also an external development that added to its acceleration, and that was the advent, in 2016, of United Payments Interface (UPI), a real-time payment interface devised by the National Payments Corporation of India, and regulated by the Reserve Bank of India, facilitating and speeding up inter-bank, person to person and person to merchant transactions.

Paytm: Operating History

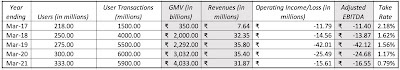

The rise of Paytm (Pay through Mobile) as a company parallels the rise of mobile phones in India. When it was founded in in 2010 by by Vijay Sharma, it operated as a pre-paid mobile platform, but its market then was small both in terms of numbers and services offered. As mobile access improved, Paytm has relentlessly added to its suite of products. In 2014, it introduced Paytm Wallet, a digital wallet that was accepted as a payment option by leading service providers and retailers. In 2016, it added ticket booking to movies, events and amusement parks, with flight bookings soon after, and started Paytm Mall, a consumer shopping app, based upon Alibaba's Taobao Mall model. In 2017 it added Paytm Gold, allowing users to buy gold in quantities as little as 1 rupee, and Paytm Payments Bank, a messaging platform with in-Chat payments. In 2018, it added a Paytm Money, for investment and wealth management, and in 2019, it launched a Paytm for Business app for merchants to track payments. In short, over time, it has used its platform of users to launch itself into almost every online activity. As Paytm's product suite has expanded, its numbers reflect both its strengths and weaknesses, with four key statistics tracking its expansion.

The first is the number of users on its platform, using one or more of its many services. The transactions that these users make on the platform plays out in the gross merchandise value of all the products and services bought. The third is the take rate, i.e., the percentage of this gross merchandise value that Paytm records as its revenues. The last is the operating margin, it operating income (or loss) as a percent of operating income each year.The table below is my attempt to recreate how Paytm has performed on these key measures in recent years, with the caveat that some of the information (on users and GMV, especially prior to 2019) is cobbled together from claims by corporate executives, press reports and opaque disclosures from the firm. Take Rate = Revenues/ GMV

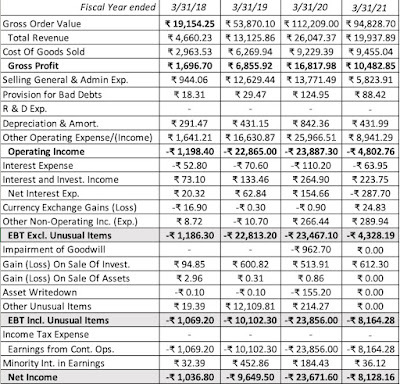

Take Rate = Revenues/ GMVLooking at the numbers, we start to get a picture of Paytm, warts and all, over its lifetime. First, it is a growth company, if you define growth as growth in user count and number of transactions done on its platform, and perhaps in gross merchandise value. However, its growth in revenues has not kept track with those larger statistics, leading to a cynical conclusion that the company is adding new services and giving them away for nothing (or close to it) to pad its user/transaction numbers. Second, this is a company that seems to run on hyperbolic forecasts from its founders and top management, that are not just consistently higher than what the company deliver, but often by a factor of three or four. For instance, just to pick on one of many examples, Vijay Sharma claimed in an interview in 2019 with Business Standard that the company's GMV would be $ 100 billion (7500 billion rupees) by the end of the year, more than double what the company reported as GMV for that year or the next. Third, access to capital from its deep pocketed investors, especially Alibaba, seems to have made this company casual about its business model and profitability, even by young, tech company standards. In fact, there is almost never even a mention of profitability (or aspirations towards profitability) in any of the corporate soundbites that I was able to read. The picture that emerges of Paytm is that of a management that is too focused on racking up user numbers, and too distracted to care about converting those into revenues and profits, while making grandiose statements about its future. Using the corporate life cycle framework to assess Paytm, it resembles an adolescent with attention deficit issues, in its scattershot approach to growth and absence of attention to business details, and if you are an investor, you have to hope that going public will cause it to grow up quickly.

Paytm: Funding and Ownership

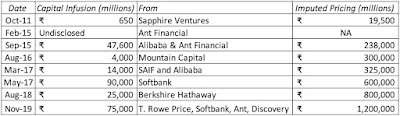

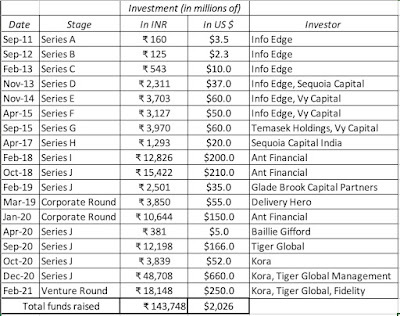

Paytm's ambitious growth plans have made it one of India's premier cash burning machines, and it has been able to pull these plans off, because it has found ample sources of capital to feed them. In the table below, I list Paytm's big capital infusions over its lifetime:

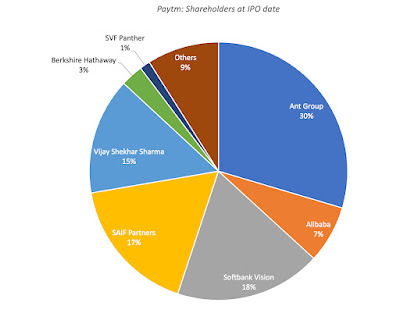

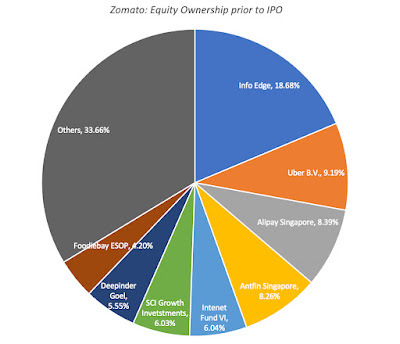

Along the way, there have been others who have provided capital to the firm (Reliance, Ratan Tata) who have exited as foreign investors, led by Alibaba and SoftBank, have muscled their way into the firm. Those capital infusions have naturally led to a diminution of the share of the company held by its founder, and the pie chart below lists the owners of Paytm, ahead of its IPO:

Paytm Prospectus

Paytm Prospectus

Note that while the company's origins and business are in India, it is primarily a Chinese-owned company ahead of its IP0, with Ant Group, Alibaba and SAIF Partners (a Hong-Kong based private equity firm) collectively owning more than 50% of the shares, with the Softbank Vision fund as the next largest investor with 18%. Vijay Sharma's holdings in the company have dwindled to 15% of the company, and his tenure as CEO depends on whether he can keep his foreign shareholder base happy.

Paytm: Story and Valuation

With that lead in, the pieces are in place to value Paytm and I will start by laying out the value drivers for the company and follow with my valuation. In making this assessment, I will draw on the company's stated plans to raise money from the offering, though they may be altered as the company gets to its offering date.

The Story

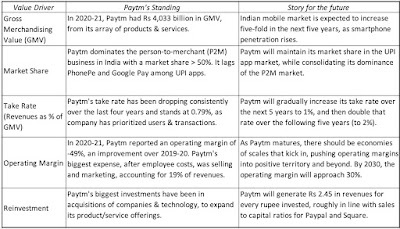

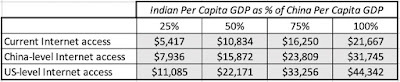

The company's history provides some insight into the Paytm's value drivers, starting with a large and growing mobile payment market in India, and working down to the company's operating metrics.

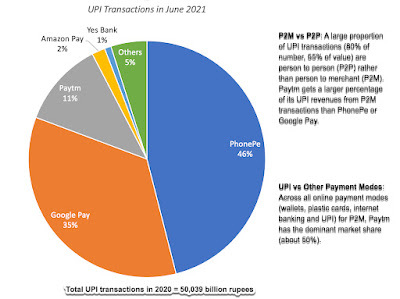

The value story for Paytm starts with a large and growing digital payment market in India, one that has surged over the last four years, and is expected to increase five-fold over the next five years, as the smart phone penetration rate rises for India and more merchants accept mobile payments. While Paytm has the advantage of having been in the Indian mobile payment market the longest, and having the largest user base, PhonePe and Google Pay have outmaneuvered Paytm in the UPI app ecosystem, claiming the lion's share of that market, though the bulk of the transaction in that ecosystem are person-to-person. Paytm's large user base, close to 350 million, and the wide acceptance of its wallets allow it to dominate the person to merchant (P2M) market in India, giving it a market share of close to 50% in early 2021.

The growth in the Indian mobile payment market will provide enough of a tailwind for Paytm to continue to grow its user base and transactions, but the bigger challenges for Paytm will be on the business dimensions where it has lagged in the past.

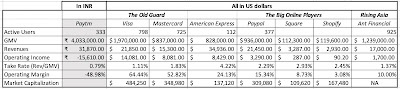

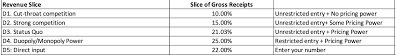

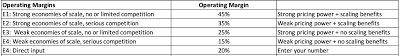

The first is in the take rate, where Paytm has seen its revenue share of GMV drop from 2.18% in 2016-17 to 0.79% in 2020-21, as the company has prioritized acquiring users and user transactions over actually generating revenues from these transactions. To get a measure of a reasonable take rate that the company can aspire to reach in the long term, I looked at larger, more established players in the payment processing space: From company 10Ks. Removed net interest income from Amex revenues and subscription/bitcoin/hardware revenues from Square revenues

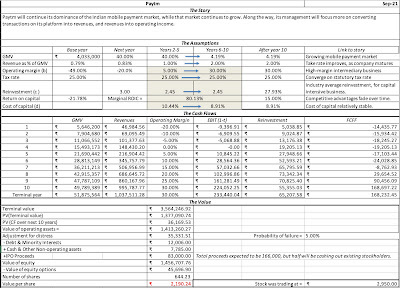

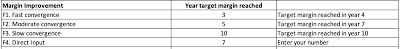

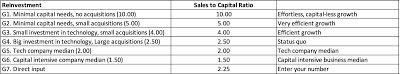

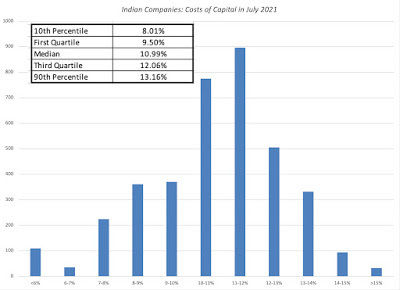

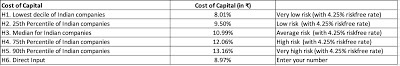

From company 10Ks. Removed net interest income from Amex revenues and subscription/bitcoin/hardware revenues from Square revenuesVisa and Mastercard, the status quo players, still retain considerable market share, though Mastercard has a higher take rate (1.83%) than Visa does (1.11%); American Express has a higher take rate than the two larger players, because it gets a higher percent of its revenue from annual card fees. Paypal Shopify and Square, all of which derive their revenues from merchandising value, have take rates between 2% and 3%, though Square gets substantial additional revenues from bitcoin transactions (not counted in GMV or revenues in this table). Ant Financials, perhaps the company that Paytm has most closely modeled itself around, has a low take rate (1.37%), but makes up for it with huge transaction volumes. In modeling Paytm's take rate over time, I will begin by assuming that the company will spend the next few years putting user growth first, at the expense of generating revenues, and that the take rate will stay low over the next five years, rising slowly to 1% in 2026. In the years following, though, I expect the take rate to double (to 2%), as the focus shifts from users to revenues, and its business model approaches that of a more conventional payment processing company.The second big challenge that Paytm faces is generating profits, a feat the company has been unable to accomplish over its lifetime. While the operating margins posted by Visa and Mastercard may be unreachable, note that Paypal's operating margin has been trending up, as the company has become bigger. As Paytm increases its revenues, and user growth starts to level off, Paytm's marketing and personnel expenses should start to decrease, and I expect operating profits to turn positive and the operating margin to reach 5% in 2026, and for that improvement to accelerate in the following five years, as growth rates decrease, allowing for an operating margin of 30% in stable growth.As a technology company, whose most valuable asset is the platform that it offers and products and services on, Paytm's reinvestments have been mostly in the form of acquisitions and technology investments, and we assume that it will continue to follow this path, generating ₹3 in revenues for every rupee of capital invested in the near term, but ₹2.45 per dollar invested in the long term, converging on an industry average (for business and consumer services). Within the online payment space, this number has wide variance, with Paypal, perhaps the most mature of the companies, having a sales to invested capital of 2.54 over the last five years and Square, a younger and faster growing player, reporting a sales to invested capital of 5.68.On the risk front, there is little reason to reinvent the wheel. Paytm's cost of capital, in rupee terms, is 10.43%, reflecting its business risk, and puts the company just below the median Indian company, in risk terms. The company's capacity to burn cash will continue to expose it to risk, but with deep pocketed investors (Alibaba and Softbank), and a large cash balance (post IPO), the risk of failure is low (5%).To get from these numbers to a value per share, I use the existing share count, in conjunction with the information in the prospectus that the company plans to raise ₹16,600 million at the offering, with half of these proceeds staying in the firm to cover future investment needs and the other half going to existing shareholders, cashing out.

There are other Paytm businesses that may augment revenues in future years, but each one comes with caveats. The money deposited in Paytm wallets by users can potentially earn interest for the company, but restrictions that this money be kept in escrow accounts at banks, not always paying close to market interest rates, can crimp that income stream. Paytm Bank could expand from its very limited presence now to more traditional banking (taking deposits, making loans), but that is a capital and regulation intensive business. I believe that Paytm's core value comes from being an intermediary, in the payments business, and the story reflects that belief.

The Valuation

If you buy into my story of Paytm continuing to maintain a dominant market share of the mobile payment market in India, while also increasing its take rate over time and improving operating margins to those of an intermediary business, you have the pieces in place for a valuation of Paytm, captured in the picture below:

Download spreadsheet; Price per share of ₹2950 is for unlisted shares.

Download spreadsheet; Price per share of ₹2950 is for unlisted shares.I know that there are many on both sides of the value divide who will disagree with me on my story and valuation, and that is par for the course. On one side, there will be some who view a value of close to $20 billion (₹1500 billion) for a company with a pittance in revenues, a history of operating losses and distracted management as insanity. On the other side, there will be some who feel that I am not giving the company credit for all of the new businesses it can enter, using its vast platform of users, and thus under valuing the company. To both sides, my defense is that this is my story and valuation, and it will drive my investment, but that you are welcome to download the spreadsheet, change the inputs that you disagree with and come up with your own valuations.

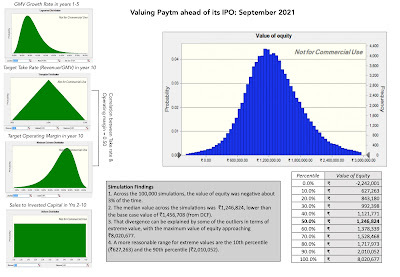

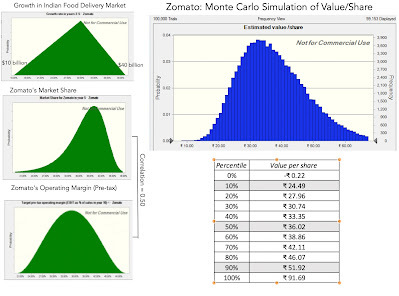

In making my assessment, I fully understand that there is substantial operating and execution risk in this story, since this value presupposes that Paytm will remain a dominant player in the Indian mobile payment space, as it grows, and that Paytm's management will pivot from growing users to growing revenues and from growing revenues to growing profits, over time, with nothing in their history to back that up. Needless to say, if I invested in Paytm, it would not only have to be at the right price, i.e., trading at less than ₹1500 billion, but also with the acceptance that this cannot be a passive (buy and hold) investment, but one that will require active engagement and monitoring of the company's actions and performance. To assess how this uncertainty will play out in my estimates of overall equity value, I did a Monte Carlo simulation, with my point estimates on total GMV, take rate, operating margin and sales to invested capital replaced with distributions:

Crystal Ball used for simulation

Crystal Ball used for simulationThere are lessons, albeit some obvious, that emerge from this simulation. First, given that almost all of the value of Paytm comes from expectations of the future, and there is significant uncertainty on every single dimension, it should come as no surprise that the range on estimated value is immense, with a 3%chance that the company's equity is worth nothing to more than ₹2000 billion at the 90th percentile. Second, with this range in value, the potential for your priors and biases to play out on your final valuation are strong. Put simply, if you like the company so much that you want to buy the stock, you can find a way to make the assumptions that get to that value. Third, even if you strongly favor the company and find it under valued, it would be hubris to concentrate your portfolio, around this stock. In other words, this is the type of stock that you would put 5% or perhaps 10% of your portfolio in, not 25% or 40%.

Closing Thoughts

As human beings, it is natural for us to categorize choices we face into broad groupings, because those groupings then allow us to generalize. In the 1980s, when technology companies first entered the market in big numbers, we classified them all as high growth, high risk investments. While that categorization would have worked at the time, it is quite clear that the technology sector today is not only a dominant segment of the market (accounting for the largest slice of the S&P 500 market capitalization pie), but is also home to a wide array of companies. In fact, at one end of the spectrum, there are many older tech companies that are now mature, and perhaps even in decline, and several are stable, cash earning machines, akin to the consumer product companies of the 1980. At the other end, you see new sub-segments of technology-based companies that have emerged to claim the "high growth, high risk" mantle, deriving more of their value from the number of users on their platforms, than from conventional financial metrics. A few weeks ago, when I valued Zomato, I argued that it was a joint bet on the company's continued dominance of the food delivery market and the growth in the Indian restaurant/food delivery business. Paytm is also a joint bet on an early entrant into the Indian mobile payment market, continuing to maintain market share, in a growing digital payment market in India. That said, the companies have very different business models, with Zomato's 20% plus take of every dollar spent on its platform vastly exceeding Paytm's less than 1% take of every dollar spent on its platform. They are both big market bets, but the Paytm bet is much more dependent on management figuring out a way to grow, while improving take rates at the same time.

YouTube Video

Spreadsheets to download

Valuation of Paytm (for IPO)

September 14, 2021

The ESG Movement: The "Goodness" Gravy Train Rolls On!

Last year, I wrote a post on ESG and explained why I was skeptical about the claims made by advocates about the benefits it would bring to companies, investors and society. In the year since, I have heard from many on the topic, and while there are some who agreed with me on the internal inconsistencies in its arguments, there were quite a few who disagreed with me. In keeping with my belief that you learn more by engaging with those who disagree with you, than those who do, I have tried my best to see things through the eyes of ESG true believers, and I must confess that the more I look at ESG, the more convinced I become that "there is no there there". More than ever, I believe that ESG is not just a mistake that will cost companies and investors money, while making the world worse off, but that it create more harm than good for society.

ESG: Value and Pricing ImplicationsRather than repeat in detail the points I made in last year's post, I will summarize my key conclusions, with addendums and modifications, based upon the feedback (positive and negative) that I have received.

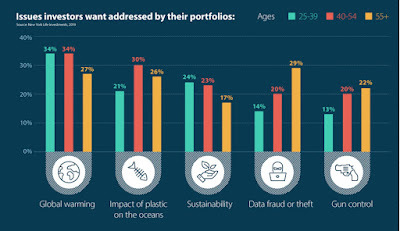

1. Goodness is difficult to measure, and the task will not get easier!The starting point for the ESG argument is the premise that we can come up with measures of goodness that can then be targeted by corporate managers and used by investors. To meet this demand, services have popped up around the world, claiming to measure ESG with scores and ratings. As I noted in my last post, there seems to be little consensus across services on how to measure goodness, and the low correlation across service measures of ESG has been well chronicled. The counter from the ESG services and ESG advocates is that these differences reflect growing pains, and just as bond ratings agencies found convergence on measuring default risk, services will also find commonalities. I think that view misses a key difference between default risk and goodness, insofar as default is an observable event and services were able to learn from corporate defaults and fine tune their ratings. Goodness is in the eyes of the beholder, and what you perceive to be a grevious corporate sin may not even register on my list, as a problem. To illustrate how investors can differ on core values, consider the chart below, where investors were asked to assess which issues should rank highest, when considering corporate goodness:

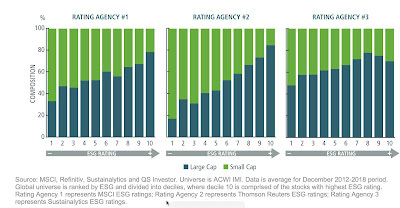

Based on this survey, younger investors want the focus to be on global warming and plastics, whereas older investors seem to focus on data fraud and gun control. If you expand these factors to include other social and religious issues, I would wager that the differences will only widen. As ESG scores and ratings get more traction, researchers are also looking at the factors that allow companies to get high scores and good rankings, and improve them over time. Studies of ESG scores find that they were influenced by company size and location, with larger companies getting higher ESG scores/rankings than smaller companies, and developed market companies getting higher scores and rankings than emerging market companies:

LaBella, Sullivan, Russel and Novikov (2019)

LaBella, Sullivan, Russel and Novikov (2019)

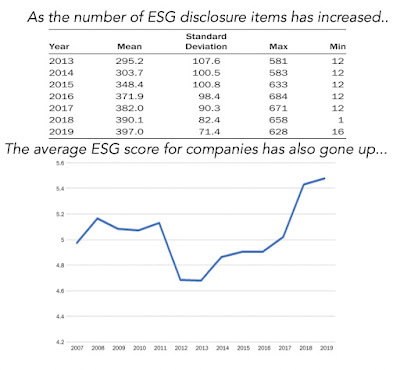

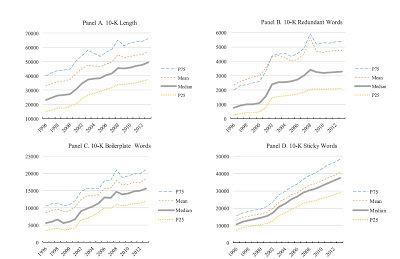

It is entirely possible that big companies are better corporate citizens than smaller ones, but it is also just as plausible that big companies have the resources to play the ESG scoring game, and that more disclosure is a tactic used by these companies that want to bury skeletons in their current or past lives, rather than expose them. In fact, a JP Morgan study of ESG Ratings and disclosures also points to a larger danger from enhanced ESG disclosure requirements, which is that the ESG ratings seems to increase across companies, as disclosure increase.

Chen et al, JP Morgan

Chen et al, JP MorganWhile I am sure that there will be some in the ESG community who will view this as vindication that disclosure is inducing better corporate behavior, the cynic in me sees companies learning to play the ESG game, at least as designed by services, and using the disclosure process to check boxes and up their scores. To me, the parallels to the corporate governance movement from two decades ago are uncanny, where services rushed to estimate corporate governance scores for companies, accountants and rule writers added hundreds of pages of disclosure on corporate governance, and promises were made of a "golden age" for shareholder power. The fact that the corporate governance movement enriched services, consultants and bankers, and left shareholders more powerless than they were before the movement started, holding shares in companies with dual class shares or worse, should act as a warning for ESG disclosure/measurement advocates, but I have a feeling that it will not.

2. Being “good” will add to value some companies, hurt others, and leave the rest unaffected!

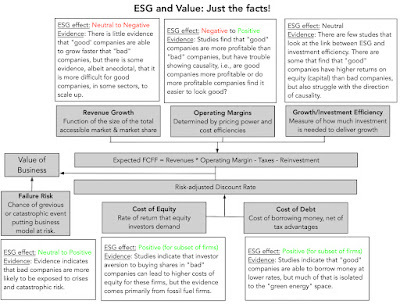

If the ESG sales pitch to companies, which is that if you are a "good" company, you will be worth more, is right, why do we need ESG? In fact, Milton Friedman, the bête noire of ESG advocates, would stand vindicated, and companies would do good, because it made them more profitable and valuable, and not because of lectures about morality and goodness. This may be cynical, on my party, but the very fact that ESG advocates keep insisting that being "good" increases value must be because they are themselves unsure why or whether this is true. The framework for tracing out the effect of ESG on value is a simple one, since ESG, if it affects value, has to affect one of four variables: revenue growth (by increasing or decreasing growth), operating profit margins, reinvestment efficiency (the payoff to investing in new capacity) or risk (through the cost of funding/capital and failure risk). In last year's post, I noted that the empirical evidence that ESG has a positive payoff is weak, at best, and inconclusive, for the most part: The strongest evidence that is supportive of ESG comes on the risk front, with evidence that it does not pay to be a "bad" company, with some a higher cost of funding and greater risk of catastrophes, but much of that evidence comes from fossil fuel companies. The weakest evidence in ESG's favor is on profitability and cash flows, since almost every study that purports to find positive correlation between profitability and ESG scores trips up on the causality question, i.e., are "good" companies more profitable or are companies that are more profitable able to take the actions that make them look good? An objective look at the data would lead us to conclude that while one can make a reasonable case that companies should work at "not being bad", there is very little evidence that there is a payoff to spending more money to be "good".

The strongest evidence that is supportive of ESG comes on the risk front, with evidence that it does not pay to be a "bad" company, with some a higher cost of funding and greater risk of catastrophes, but much of that evidence comes from fossil fuel companies. The weakest evidence in ESG's favor is on profitability and cash flows, since almost every study that purports to find positive correlation between profitability and ESG scores trips up on the causality question, i.e., are "good" companies more profitable or are companies that are more profitable able to take the actions that make them look good? An objective look at the data would lead us to conclude that while one can make a reasonable case that companies should work at "not being bad", there is very little evidence that there is a payoff to spending more money to be "good".3. The ESG sales pitch to investors is internally inconsistent and fundamentally incoherent

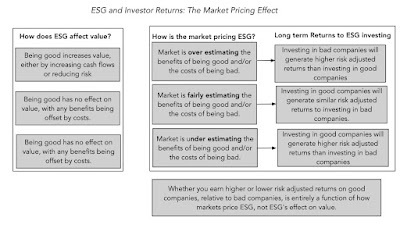

If the argument that ESG translates into higher value is weak, the argument that incorporating ESG into your investing is going to increase your returns fails a very simple investment test. For any variable, no matter how intuitive and obvious its connection to value might be, to generate "excess" returns, you have to consider whether it has been priced in already. That is why investing in a well managed company or one that has high growth does not translate into excess returns, if the market already is pricing in the management and growth. Applying this principle to ESG investing, the question of whether ESG-based investing pays off or not depends on not only whether you think ESG increases or decreases firm value, but also on whether the market has already priced in the impact.

If the market has fully priced in the ESG effect on value, positive or negative, investing in 'good' companies or avoiding 'bad' companies will have no effect on excess returns. In fact, if being good makes companies less risky, investors in good companies will earn lower returns than investors in bad companies, before adjusting for risk, and equivalent returns after adjusting for risk.If the market is over enthused with ESG and is overpricing how much being "good" will add to a company's profitability or reduce risk, investing in 'good' companies will generate lower risk-adjusted returns than investing in 'bad' companies.If the market is underestimating the benefits of being good on growth, margins and risk, investing in 'good' companies will generate higher returns for investors, even after adjusting for risk.In the latter two cases, the excess returns (negative in the "markets are over estimating" case and positive in the "markets are under estimating") will manifest only when the market corrects its mistakes. Bringing in market pricing into the discussion is important for two reasons. The first is that it suggests that much of the research on the relationship between ESG and returns yields murky findings. Put simply, there is very little that we learn from these studies, whether they find positive or negative relationships between ESG and investor returns, since that relationship is compatible with a number of competing hypotheses about ESG, value and price. The second is that bringing in market pricing does shed some light on perhaps the only aspect of ESG investing that seems to deliver a payoff for investors, which is investing ahead or during market transitions. In my last post, I pointed to this study that find that activist investors who take stakes in "bad" companies and try to get them to change their ways generate significant excess returns from doing so. Another study contends that investing in companies that improve their ESG can generate excess returns of about 3% a year, but skepticism is in order because it is based upon a proprietary ESG improvement score (REIS), and was generated by an asset management firm that invests based upon that score. If you are interested in making market transitions on ESG work in your favor, you also have to be clear about the strengths you will need to get the payoffs, including skills in divining not only what social values are gaining and losing ground and which changes have staying power.

If the market has fully priced in the ESG effect on value, positive or negative, investing in 'good' companies or avoiding 'bad' companies will have no effect on excess returns. In fact, if being good makes companies less risky, investors in good companies will earn lower returns than investors in bad companies, before adjusting for risk, and equivalent returns after adjusting for risk.If the market is over enthused with ESG and is overpricing how much being "good" will add to a company's profitability or reduce risk, investing in 'good' companies will generate lower risk-adjusted returns than investing in 'bad' companies.If the market is underestimating the benefits of being good on growth, margins and risk, investing in 'good' companies will generate higher returns for investors, even after adjusting for risk.In the latter two cases, the excess returns (negative in the "markets are over estimating" case and positive in the "markets are under estimating") will manifest only when the market corrects its mistakes. Bringing in market pricing into the discussion is important for two reasons. The first is that it suggests that much of the research on the relationship between ESG and returns yields murky findings. Put simply, there is very little that we learn from these studies, whether they find positive or negative relationships between ESG and investor returns, since that relationship is compatible with a number of competing hypotheses about ESG, value and price. The second is that bringing in market pricing does shed some light on perhaps the only aspect of ESG investing that seems to deliver a payoff for investors, which is investing ahead or during market transitions. In my last post, I pointed to this study that find that activist investors who take stakes in "bad" companies and try to get them to change their ways generate significant excess returns from doing so. Another study contends that investing in companies that improve their ESG can generate excess returns of about 3% a year, but skepticism is in order because it is based upon a proprietary ESG improvement score (REIS), and was generated by an asset management firm that invests based upon that score. If you are interested in making market transitions on ESG work in your favor, you also have to be clear about the strengths you will need to get the payoffs, including skills in divining not only what social values are gaining and losing ground and which changes have staying power.4. Outsourcing your conscience is a salve, not a solution!

Even if being “good” does not increase value or make investors better off, could it still help, by making the world a better place? After all, what harm can there be in asking and putting pressure on companies to behave well, even if costs them? In the short term, the answer may be no, but in the long term, I believe that this will cost us all (as society). The ESG movement has given each of us an easy way out of having to make choices, by outsourcing these choices to corporate CEOs and investment fund managers, asking them to be “good” for us, while not charging us more for their products and services (as consumers) and delivering above-average returns (as investors). Implicit in the ESG push is the presumption that unless companies that are explicitly committed to ESG, they cannot contribute to society, but that is not true. Consider Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, two men who built extraordinarily valuable companies, with goodness a factor in decision making only if it was good for business. Both men have not only made giving pledges, promising to give away most of their wealth to their favorite causes in their lifetimes, and living up to that promise, but they have also made their shareholders wealthy, and many of them give money back to society. As I see it, the difference between this “old” model of business and the proposed “new ESG” version is in who does the giving to society, with corporate CEOs and management taking over that responsibility from shareholders. I am willing to listen to arguments for why this new model is better, but I am certainly not willing to concede, without challenge, that a corporate CEO knows my value system better than I do, as a shareholder, and is better positioned to make judgments on how much to give back to society, and to whom, than I am.

For a perspective more informed and eloquent than mine, I would strongly recommend this piece by Tariq Fancy, whose stint at BlackRock, as chief investment officer for sustainable investing, put him at the heart of the ESG investing movement. He argues that trusting companies and investment fund managers to make the right judgments for society will fail, because their views (and actions) will be driven by profits, for companies, and investment returns, for fund managers. He also believes that governments and regulators have been derelict in writing rules and laws, allowing companies to step into the void. While I don’t share his faith that government actions are the solution, I share his view that entities whose prime reasons for existence are to generate profits for shareholders (companies) or returns for investors (investment funds) all ill suited to be custodians of public good.

Cui Bono? The ESG Gravy Train (or Circle)!

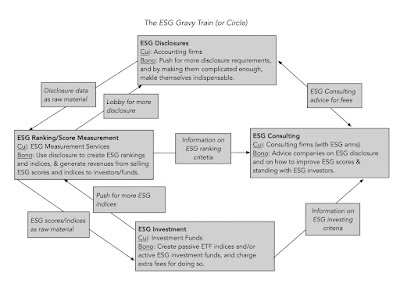

If ESG is a flawed concept, perhaps fatally so, and if the flaws are visible for everyone to see, how do we explain the immense push in both corporate and investment settings? I think the answer always lies in asking the question "Cui Bono, or who benefits?". With ESG, the answer seems to be everyone, but those it is purported to help, i.e. corporate stakeholders, investors and society. The picture below captures the groups that have primarily benefited from the ESG boom, and how they feed off each other.

Given how much ESG disclosure advocates, measurement services, investment funds and consultants feed off each other, it is no wonder that they have an incentive to sell you on its unstoppable growth and inevitable success. Given that shareholders in companies and investors in funds are paying for this gravy, you may wonder why corporate CEOs not only go along with this charade, but also actively encourage it, and the answer lies in the power it gives them to bypass shareholders and to evade accountability. After all, these are the same CEOs who, in 2019, put forth the fanciful, but great sounding, argument that it is a company’s responsibility to maximize stakeholder wealth, rather than cater to shareholders, which I argued in a post then that being accountable to everyone effectively meant that CEOs were accountable to no one. In some cases, flaunting goodness has become a way that founders and CEOs use to cover business model weaknesses and overreach. It is a point that I made in my posts on Theranos, at the time of its implosion in October 2015, and on WeWork, during its IPO debacle in 2019, noting that Elizabeth Holmes and Adam Neumann used their “noble purpose” credentials to cover up fraud and narcissism.

I should add that, notwithstanding my negative views about ESG, I do not think that ESG consultants, fund managers and analysts are venal, but I do think that they, like everyone else, are driven by self interest. I also believe that many in the ESG ecosystem are driven by good motives, a desire to do good for society and make the world a better place, but that are being used by a few at the top of the ESG pyramid, whose commitment to the cause is skin deep. If you are someone working in the ESG space or a true believer, please do look to the highest profile spokespersons for your cause, mostly corporate CEOs and investment fund titans, and remember the adage about waking up with fleas, if you lie down with dogs.A Roadmap for being and doing Good

My skepticism about ESG notwithstanding, I understand its draw, especially on the young. As individuals, each of us has a moral code, sometimes coming from religion, sometimes from family and sometimes from culture, but whatever its source, our actions should be consistent with that code. Since those actions involve what we do at work, and in investing, it stands to reason that there are some investments you will and should not make, because it violates your sense of right and wrong, and other investments that you will make, because they advance your view of goodness. It is for this reason that I would suggest a more nuanced and personalized version of ESG, built around the following principles:

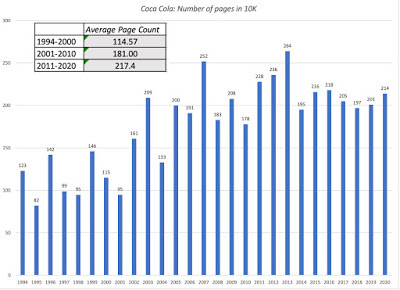

Start with a personalized measure of goodness, and don’t overreach: The key with moral codes is that they are personal, and for goodness to be incorporated into your investment and business decisions, you have to bring in your value judgments, rather than leave it to ESG measurement services or to portfolio managers. I would also recommend that you focus on core values, rather than try to find a match on every one, not only because adding too restrictions will constrain you in your choices, perhaps to the point of paralysis, but also because you may find yourself accepting major compromises on your key values in order to meet secondary values. As a business person, be clear on how being good will affect business models and value: If you own a business, you are absolutely within your rights to bring your personal views on morality into your business decisions, but if you do so, you should work through the effects on growth, margins and risk, and be at peace with the fact that staying true to your values may, and probably will, cost you money. If you are making decisions at a publicly traded company, as an employee, manager or even CEO, you are investing other people’s money and if you choose to make decisions based upon your personalized moral code, you cannot justify these decisions with hand waving and double talk. In fact, you have an obligation to be open about what your conscience will cost your shareholders, a twist on disclosure that ESG advocates will not like.As an investor, understand how much goodness has been priced in: If you are an investor, you don’t have to compromise on your values, as long as you start with the recognition that, at least in the long term, you will have to accept lower returns than you would have earned without that constraint. If you are tempted to have your cake and eat it too, and who isn’t, you may be able to do so by getting ahead of the market in detecting shifts in social mores and pushing for change in the companies you invest in, to change. As a consumer and citizen, make choices that are consistent with your moral code: If you believe that owning a portfolio of “good” stocks or running a “good” business is all you have to do to fulfill your moral or societal obligations, you are wrong. Your consumption decisions (on which products and services you buy) and your citizenship decisions (on voting and community participation) have as big, if not greater, an effect. Put simply, if your key societal issue is climate change, your refusal to own fossil fuel stocks in your portfolio is of little consequence, if you still drive a gas guzzler, air condition your house to feel like an ice box all summer and take private corporate jets to Davos every year.On a personal note, I have always found that the people that I've known who do good, spend very little time talking about being good or lecturing other people on goodness. I would extend that perspective to companies and investment funds as well, and I reserve my skepticism for those companies that spend hundreds of pages of their annual filings telling me how much "good" they do.In conclusion The ESG movement’s biggest disservice is the message that it has given those who are torn between morality and money, that they can have it all. Telling companies that being good will always make them more valuable, investors that they can add morality constraints to their investments and earn higher returns at the same time, and young job seekers that they can be paid like bankers, while doing peace corps work, is delusional. In the long term, as the truth emerges, it will breed cynicism in everyone involved, and if you care about the social good, it will do more damage than good. The truth is that, most of the time, being good will cost you and/or inconvenience you (as businesses, investors or employees), and that you choose to be good, in spite of that concern. YouTube Video

September 1, 2021

China's Tech Crackdown: Its about Control, not Consumers or Competition!

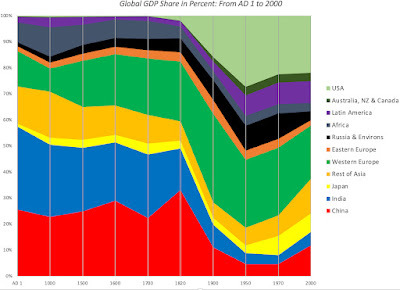

Angus Maddison, University of Groningen

In 1500, China had the largest GDP of any country in the world, followed by India, not surprising since output and population were tied together strongly at the time, when human labor was the key driver of economic output. With the advent of the Industrial Age, both India and China fell off the pace, and by the start of the twentieth century were punching well below their (population) weight.

Angus Maddison, University of Groningen

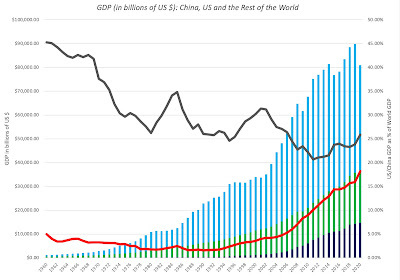

In 1500, China had the largest GDP of any country in the world, followed by India, not surprising since output and population were tied together strongly at the time, when human labor was the key driver of economic output. With the advent of the Industrial Age, both India and China fell off the pace, and by the start of the twentieth century were punching well below their (population) weight.I am not an historian or political scientist, and will not probe the reasons, but China spent much of the twentieth century with a stalled economy, and in 1970, China's GDP accounted for 4.63% of global GDP, down from more 30% in 1820. The turn around that occurred in China's economic growth occurred is one for the history books, and you can see the rise in the graph below, where I look at China's GDP, relative to the United States (which had the dominant share of global GDP) and to the rest of the world between 1960 and 2020:

World Bank Database

World Bank Database

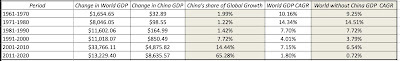

The United States, which used to account for close to half of global GDP in 1960 has seen its share drop go global GDP drop to 25%, while China's share has climbed close to 20% in 2020. To get a sense of how dependent the world economy has become on China for its growth, take a look at the table below, where I report World GDP growth, by decade, with and without China:

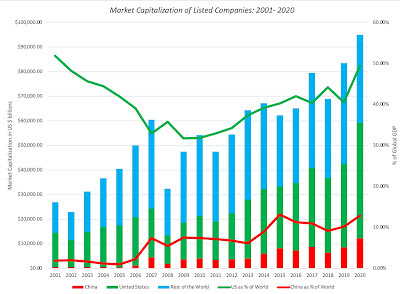

World BankPut bluntly, without China, the world economy would have tread water for the last decade, since China accounted for close to two thirds of global GPD added on during the decade. As China's economy has grown, its financial markets have also found their footing, albeit at a slower pace. In the graph below, I plot the market capitalization of Chinese listed companies, in dollar terms, and as a percent of market capitalization of all global companies:

World BankPut bluntly, without China, the world economy would have tread water for the last decade, since China accounted for close to two thirds of global GPD added on during the decade. As China's economy has grown, its financial markets have also found their footing, albeit at a slower pace. In the graph below, I plot the market capitalization of Chinese listed companies, in dollar terms, and as a percent of market capitalization of all global companies:

World Bank Database

World Bank Database

Chinese equities have risen from a negligible share of global market capitalization, in 2000, to more than 10% of global market capitalization, in 2020. It is beyond debate that China's economy and markets have had a renaissance, cementing the country’s place as a leading economic power.

While many of the companies listed initially on the Chinese markets represented infrastructure and financial service companies, the last decade has seen the rise of the Chinese tech behemoth. That transition can be seen when you compare the fifteen largest Chinese companies, in market capitalization terms, at the end of 2010 to the fifteen largest Chinese companies, again in market capitalization terms, at the end of 2020.

S&P Capital IQAt the end of 2010, of the fifteen largest market cap companies in China, only two were tech companies (Tencent and Baidu), and they were towards the bottom of the rankings; banks and insurance companies dominated the list. By the end of 2020, six of the top fifteen were technology companies, and Tencent and Alibaba topped the rankings.The Chinese Tech DecadeThe rise of technology as an economic force and market driver is not unique to China. After all, the FANGAM stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google, Apple and Microsoft) were the engine that drove market capitalization up in the US, for the last decade, with COVID super charging their rise in 2020. In this section, I will focus on the Chinese tech market, by looking at some its biggest success stores, and using them to gain an understanding of both the promise and peril in this business. Chinese Tech Plays - The Lead InIn this day and age, every business brands itself, at least in part, as a technology company, and it is always tricky to try to crystallize the diverse mix of technology into a tech sector. That said, there is an advantage to taking a deeper look at some of the biggest winners in the tech business, not only to understand why they succeeded, but also to get insights into whether they can sustain that success in the future. It is for that reason that I will focus on four Chinese tech companies (Tencent, Alibaba, JD.com and Didi) for the rest of this post, the first three because they make the top fifteen list of market cap companies in China, and Didi because of its high profile IPO, just a few weeks ago.

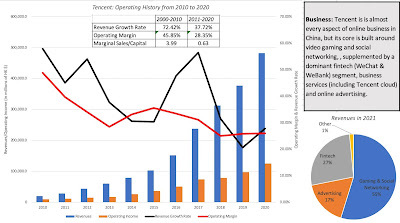

S&P Capital IQAt the end of 2010, of the fifteen largest market cap companies in China, only two were tech companies (Tencent and Baidu), and they were towards the bottom of the rankings; banks and insurance companies dominated the list. By the end of 2020, six of the top fifteen were technology companies, and Tencent and Alibaba topped the rankings.The Chinese Tech DecadeThe rise of technology as an economic force and market driver is not unique to China. After all, the FANGAM stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google, Apple and Microsoft) were the engine that drove market capitalization up in the US, for the last decade, with COVID super charging their rise in 2020. In this section, I will focus on the Chinese tech market, by looking at some its biggest success stores, and using them to gain an understanding of both the promise and peril in this business. Chinese Tech Plays - The Lead InIn this day and age, every business brands itself, at least in part, as a technology company, and it is always tricky to try to crystallize the diverse mix of technology into a tech sector. That said, there is an advantage to taking a deeper look at some of the biggest winners in the tech business, not only to understand why they succeeded, but also to get insights into whether they can sustain that success in the future. It is for that reason that I will focus on four Chinese tech companies (Tencent, Alibaba, JD.com and Didi) for the rest of this post, the first three because they make the top fifteen list of market cap companies in China, and Didi because of its high profile IPO, just a few weeks ago. I am not a fan of extensive corporate write ups, with long treatises about corporate history and developments, since they often operate more as distractions than as sources of information. Instead, I will try to compress what I know (which is not much) about the evolution and operations of each of the four companies. I will start with Tencent, in deference to its age (it is the oldest of the four) as well as its standing as the largest market cap company on the list.

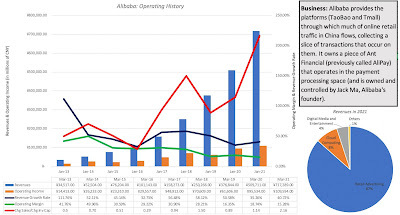

Tencent is the most versatile of the four companies, in terms of its business mix, and while it has been in existence for 20 years as a publicly traded company, its growth in the last decade has converted it from a minnow to a whale. Moving to Alibaba, the second largest Chinese tech company in 2020, I drew on a blog post that I wrote ahead of its IPO in 2014, where I described it as “the Real China Story”, because so much of Chinese retail traffic travels through its platforms (Taobao and TMall), with the company collecting a slice of the transaction revenues, in return for its intermediation services.

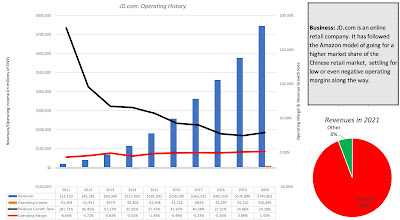

While Alibaba is sometimes characterized as China's Amazon, it is closer to Google in its business model, collecting most of its revenues from customers using its platforms to buy goods and services. Staying in the online retail space, I look at JD.com, which operates more as a retailer, selling goods and services through its platforms.

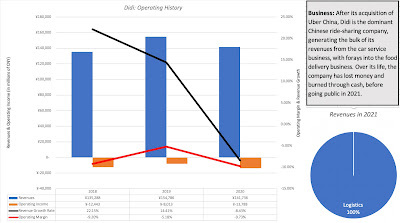

Note that JD.com, while posting strong revenue growth rates for much of the last decade, has had trouble generating significant operating profits. That, in my view, is not accidental, since the company has been open about its focus on increasing market share, at the expense of profitability, following the Field of Dreams model (If we build it, they will come)... The final company in my list is Didi, a company that I had tracked in the process of valuing Uber and Lyft, and it followed them into public markets in 2021:

Didi's acquisition of Uber China has given it dominance over the Chinese ride sharing market, but it is difficult to see the payoff in the numbers. Revenues have stagnated between 2018 and 2020, and the easy excuse of COVID does not explain the stagnation, since growth was tepid even in 2019. The company has also shown an almost unparalleled capacity to lose money and burn through cash, even by ride sharing company standards.Chinese Tech Plays - Valuation StoriesTo value the Chinese tech companies, I have to construct valuation stories that fit them, and as you can see there are big differences across the four companies (Tencent, Alibaba, JD.com and Didi) not only in where they are in terms of growth potential, but also in terms of profitability and business models. That said. there are some commonalities across these companies that I will explore in this section.

Big Markets (Squared)There are many aspects that make Chinese tech companies attractive to investors, but the one overriding attraction of these companies is their access to the Chinese market. As I noted in the first section, China was the engine that drove global growth over the last decade, and with that growth has come a surge in buying power for Chinese consumers. Companies that are positioned to take advantage of this growth, whether domestic or foreign, have been rewarded by investors with higher market capitalizations, even if the promise has not translated into profitability (yet). With tech companies that are disrupting conventional businesses, there is an added allure of growth occurring at the expense of the status quo. Tencent in the gaming business, Alibaba and JD.com, with retailing, and Didi, with logistics, are all disruptors of the status quo, in the businesses that they operate in. You could argue that this combination of China and disruption creates growth stories on steroids, as investors load on dreams of one big market (from disruption) on top of another (China).

As with any steroid-driven story, there are downsides. First, I have had multiple posts on the big market delusion, where I argue that investors often over estimate the likelihood and payoffs of success in big markets, because they fail to factor in new entrants, and changing technology fully. This argument applies to Chinese companies, generally, and to Chinese tech companies, specifically, as "the market is huge, the company's value has to be immense" argument often wins the day. Second, the size of the Chinese market, in conjunction with local dominance, has also meant that Chinese tech companies prioritize domestic market growth, simply because it is easier and often more profitable. Of the four companies that I am analyzing, Tencent is the only one where foreign market revenues are substantial enough to make a difference to its valuation. Alibaba has aspirations to grow in foreign markets but has little to show yet in terms of profits, and Didi and JD.com are almost entirely China-focused. Clearly, their global ambitions notwithstanding, Chinese tech companies have remained overwhelmingly Chinese. There are benefits to getting growth from domestic markets, but that dependence also makes these companies extraordinarily exposed to government regulations and restrictions in these markets.

Attuned to the Chinese MarketThe argument that the big (and growing) Chinese tech market explains the success of the winners (like Alibaba, Tencent, JD.com and Didi) short changes these companies, by underplaying what each of them brought to the game that allowed them to succeed. Note that these companies were very much part of the pack, competing with foreign and domestic players, just a decade or two ago, but have managed to separate themselves from their competitors, in the years since. While there are many factors that may have contributed, one in particular stands out. Rather than copying what successful US tech companies were doing to gain market share and profitability, these companies tailored their business models and product offerings to the Chinese market, adapting to what Chinese consumers cared about and wanted. In my IPO post on Alibaba, I argued that the reason it was able to vanquish eBay and more established competitors was because it created what the Economist called the "world's greatest bazaar" and a payment mechanism that Chinese consumers felt comfortable using online. Tencent not only built a gaming platform specifically focused on Chinese consumers, but was well ahead of its US tech competitors in building the world's leading social media platform in WeChat. Didi was conceived as a cab-hailing company in 2012, but it too tailored its services to the local characteristics of the Chinese market, acquiring its main domestic rival in Kuadi Dache in 2015, and forcing Uber to capitulate and sell its Chinese segment in 2017.

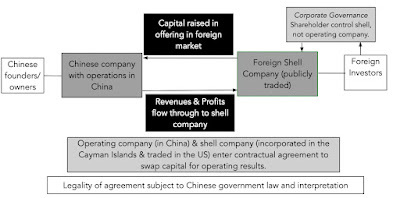

Corporate Governance NightmaresThere is another feature that Chinese tech companies share, and it is not a favorable one. While Alibaba, Tencent, JD.com and Didi are undeniably Chinese companies (both in terms of operations and where they get their revenues), three of these companies (Alibaba, JD and Didi) made their public market debuts in New York, with NASDAQ listings. In fact, these three companies are also incorporated in the Cayman Islands, and Tencent began its corporate life as a Cayman Island listing. In fact, the structure (called a variable interest entity or VIE) used by Alibaba, HD and Didi essentially means that shareholders are technically owners of shell companies (in the Cayman Islands) rather than the Chinese enterprises that they they think they are buying.

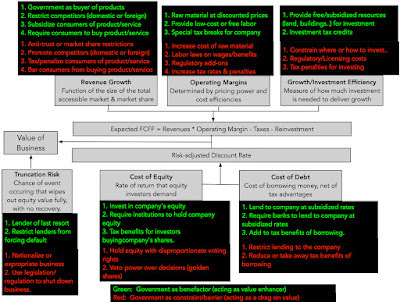

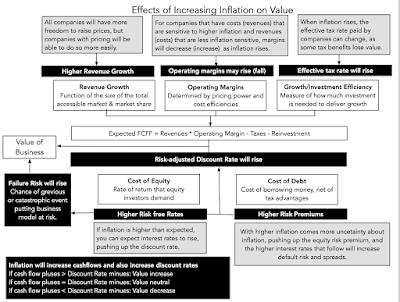

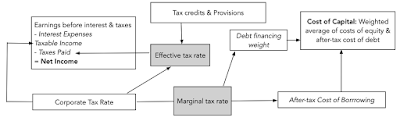

Why do Chinese tech companies favor this convoluted structure? The answer lies in Chinese laws and regulations that restrict the types of business that foreign investors are allowed to own shares in, and technology is one of those restricted businesses. Variable interest entities are a technicality that allows Chinese tech companies to get around the law, but they hold up only because the Chinese government has looked the other way, perhaps because the benefits to China (of tapping into foreign capital) exceed the costs. The legality of variable interest entities is still much debates, but if its gets litigated, stockholders in these companies may find themselves with limited standing. As an added complication, each of these companies has elaborate subsidiary structures, including wholly owned, majority owned and minority owned subsidiaries that are, at best, opaquely reported upon, and at worst, a blank slate.Beijing: A Silent (or not-so-silent) Partner!The discussion of variable interest entities (VIE) its a good lead in to the third component that Chinese tech companies share in common, which is that the Chinese government is a player in the game, no matter what business you enter into in China. Note, though, that the notion that governments are neutral arbiters who don't affect company value is utopian, since governments in every market affect almost every dimension of value, sometimes positively and sometimes negatively. In the figure below, I have used my value drivers framework, where I connect the value of a company to key drivers of value (revenue growth, operating margins, capital intensity and risk), to examine how government action (or inaction) can affect each driver.

Why do Chinese tech companies favor this convoluted structure? The answer lies in Chinese laws and regulations that restrict the types of business that foreign investors are allowed to own shares in, and technology is one of those restricted businesses. Variable interest entities are a technicality that allows Chinese tech companies to get around the law, but they hold up only because the Chinese government has looked the other way, perhaps because the benefits to China (of tapping into foreign capital) exceed the costs. The legality of variable interest entities is still much debates, but if its gets litigated, stockholders in these companies may find themselves with limited standing. As an added complication, each of these companies has elaborate subsidiary structures, including wholly owned, majority owned and minority owned subsidiaries that are, at best, opaquely reported upon, and at worst, a blank slate.Beijing: A Silent (or not-so-silent) Partner!The discussion of variable interest entities (VIE) its a good lead in to the third component that Chinese tech companies share in common, which is that the Chinese government is a player in the game, no matter what business you enter into in China. Note, though, that the notion that governments are neutral arbiters who don't affect company value is utopian, since governments in every market affect almost every dimension of value, sometimes positively and sometimes negatively. In the figure below, I have used my value drivers framework, where I connect the value of a company to key drivers of value (revenue growth, operating margins, capital intensity and risk), to examine how government action (or inaction) can affect each driver.

There are a myriad of ways in which governments can add or detract from value, and the net effect will depend on the company and government in question. I have found this framework useful in dealing with a effect on value of everything from crony capitalism and political connections to regulation.

If this is true for all companies, why make this an issue with just Chinese tech companies? There are two reasons. First, the Chinese government can not only change the competitive balance and business more decisively than democratic counterparts, where making laws involves trade offs and bargains, but also make the changes more permanent, since a change in government is not in the cards. Second, in most countries, government rules and regulations have to run a gauntlet of legal challenges, before becoming law, since a judiciary can over ride, delay or even set aside government actions. This may reflect my ignorance, but I have never heard of a Chinese government law or regulation that had to be withdrawn or suspended, because a Chinese court ruled it illegal. Put simply, the Chinese government has more power to give and to take away from its companies than any other government of consequence in the world. Sensible investors have always understood this power, and tried to price them in, but for much of the last decade that has led them to bid up Chinese companies, on the assumption that Beijing would tilt the playing field in favor of domestic companies, at the expense of foreign competitors, and that the governments' push for more economic growth would make it more likely to be an ally, rather than an adversary, to companies.

That calculation, though, does miss the other quality that the Chinese government has always valued, which is control, and the tussle between the two (growth and control), in my view, explains much of the crackdown on Chinese tech. As Chinese tech companies have become larger and more valuable, they have also become repositories for data on their customers, and that data is what Beijing not only fears, but covets. While the government may frame its crackdown on big tech as designed to protect Chinese consumers’ privacy or to prevent market domination, the truth is that this is mostly about the Chinese government increasing its control of data and markets. Just as a thought experiment, if the Chinese government had the information that Tencent and Alibaba have about their customers, do you believe that they would not keep it? Whatever the reasons for the Chinese government’s actions, it is undeniable that they have changed the calculus, at least for the moment, of how the Chinese government affects Chinese tech company valuations. As investors bring in the downside of the government effects on value, markets have reassessed the pricing of all four of the companies that I am valuing, dropping market capitalization by 17% for Tencent, 46% for Alibaba and 7% for JD.com in 2021, over the most recent year, and providing a frosty reception to Didi’s IPO, with the stock price dropping 42% from its offer price of $14 a share , just a few weeks ago. The question is not whether the mark down on price has a good reason (it does), but whether the market is over or under reacting to the new relationship between Chinese tech and the Chinese government.Investing in China TechWith that long lead in, I think that we are positioned to not only value Tencent, Alibaba, JD.com and Didi, but also to bring in the effect of activist government on their value drivers in the future. In the process, the question of whether these companies are cheap, given their recent mark downs, or expensive, will be answered.

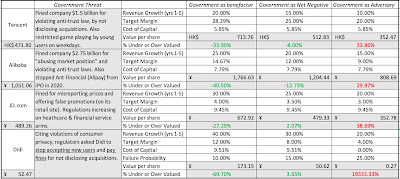

Valuing Chinese Tech Companies As I noted in the last section, investors have priced Chinese tech companies for much of the last decade, on the presumption that the Chinese government would be a net plus for these companies, stifling competition from foreign companies and easing the pathway to growth to profitability. It is for that reason that investors have been shocked by the realization that what governments can give, they can take away. Rather than bury you in details of each company's valuation, I have summarized the key inputs and valuations of each company, under three scenarios, built around views of the government - the government as benefactor, the government as a net-negative (more likely to hurt the company than help it, reflecting my current view on the Chinese government's relationship with these companies) and the government as adversary - in the table below:

Tencent: Government as benefactor, net negative and adversary

Tencent: Government as benefactor, net negative and adversaryAlibaba: Government as benefactor, net negative and adversary

JD.com: Government as benefactor, net negative and adversary

Didi: Government as benefactor, net negative and adversaryThe effects of the Chinese government on the valuations of these technology companies can be seen in the range of values per share that you get for each company. In making my assessments of how government affects value, I believe that almost all of the effect will be in the cash flows for the companies, since most of the restrictions are on growth (constraints rising from anti-trust moves) or on margins (costs associated with meeting privacy needs). While there is talk of banning tech companies from listing on foreign markets, using shell structures, I don't believe it will be retroactive, and the companies on my list are big enough to transition. With Didi, I do believe that a strong push by the government to restrict how it does business will increase the chance that the company will not make it as a going concern, since its business model is still a work in process.

Based upon my assessments, the quick takeaway is that at current stock prices, all four of the companies are under valued, with what I believe are reasonable constraints brought in by government actions. Alibaba is the most undervalued (by 12.7%), followed by Tencent (by 8%), but Didi and JD.com are close to being fairly valued (undervalued by 3.65% and 2.07%). Digging deeper, there is substantial downside if the government becomes openly and actively adversarial, with Didi dropping to becoming almost worthless, if that happens. On the upside, if any of these companies finds a way into the government's good graces, the benefits that flow from it can increase the upside at each of these companies, but most at Didi. Didi is clearly more exposed to government actions than the other three, suggesting a broader principle at play, which is that young companies are more affected in terms of both upside and downside, by government actions and regulations, than older companies.

Investing in Chinese Tech Companies Valuation is a pragmatic, rather than a theoretic, exercise, where the end game is not just understanding and estimating the value of a company, but acting on that valuation. If you are an investor, you should be willing to buy under valued companies and sell short on over valued companies, with the caveat that you need a market correction to make money, and that correction may take time. Since I find all four of the Chinese tech companies under valued, what would I do next? First, I would remove Didi and JD.com from the mix, largely because they are closer to fairly valued, than under valued. In fact, I would argue that looking at Didi's still unformed business model, and the huge consequences of government action or inaction, it is closer to being an option than a conventional going-concern valuation. Second, with Alibaba and Tencent, both of which are under valued in my base case (government as a net negative), I have three choices:Buy both Alibaba and Tencent, and hope that the "government as adversary" scenario does not play out for either. Buy one of the two, based upon not just the valuation but also the rest of the company, including corporate governance and structure.Buy neither, because you believe that the "government as adversary" scenario is more likely than the "government as benefactor".I am not inclined to double down (buying both companies) on betting on how the Chinese government will behave in the future, and if I had to pick one, I would pick Tencent over Alibaba for three reasons. The first is that Tencent is a more rounded company in terms of being in business mix, and I think that the WeChat platform, like the Facebook platform, adds a premium to their valuation. The second is that I prefer buying Tencent on the Hong Kong stock exchange to buying Alibaba's Cayman Islands shell company on the New York Stock Exchange. The third is that while I admire Jack Ma as an entrepreneur, I am believe that personality-driven companies have an added layer of risk, since that personality can draw attention and fire. In fact, there are some who believe that the increased regulation of Chinese technology can be traced to Jack Ma's challenging Beijing in 2020.

With my Tencent investment, I faced a secondary choice of investing directly in Tencent or indirectly buying shares in Naspers, a South African holding company. If you are puzzled about why Naspers enters the equation, the company acquired 46.5% of Tencent in return for a $32 million VC investment in 2001, and as Tencent surged in market capitalization, Naspers has become a proxy for the stock, with 80% or more of its value coming from its Tencent holdings. The one difference is that the market is discounting the holding by 20-30%, in Naspers hands, reflecting concerns about taxes due and corporate governance at Naspers. That discount seems immune to almost every attempt by Naspers to make it disappear; for instance, Naspers spun off a Dutch entity, Prosus, and endowed it with a portion of the holding, in an attempt to eliminate the discount, but the discount persists in Prosus as well, albeit a little smaller. I decided that the potential upside of hoping that the discount narrows over time is exceeded by the downside of creating an extra layer between me and my Tencent investment. (For those of you who want to track my Tencent investment, and perhaps taunt me if (or when) I get wrong, I bought the ADR on August 31.)

ConclusionIn valuation, we seldom consider the explicit effects of government policy and regulations on company value. The rationale that is usually offered for this practice is either that the government's capacities to add and detract from value offset each other or that the current numbers for the company (growth, margin etc.) already incorporate the government effect. While ignoring governments may be defensible, when government policy is stable, it breaks down when governments deviate from the script, and behave differently that they have in the past. With Chinese tech companies, long used to the Chinese government being an ally in their search for growth and profits, the last year has been a rude awakening to a new reality of a more activist and punitive version. That said, I don't for a moment believe that the Chinese government cares about either consumers or competition, the stated reasons for the crackdown, and am convinced that this is more about the it exercising control over both companies and data. I also believe that the adjustment in market prices that we have seen in Chinese tech companies is reflecting the fear that investors have now that the government will act as a constraint rather than an accelerator on future growth and profitability. As markets recalibrate prices to reflect the new reality, there are opportunities for solid returns in this space, and I hope to one of the beneficiaries!

YouTube Video

ValuationsTencent: Government as benefactor, net negative and adversaryAlibaba: Government as benefactor, net negative and adversaryJD.com: Government as benefactor, net negative and adversaryDidi: Government as benefactor, net negative and adversary

August 2, 2021

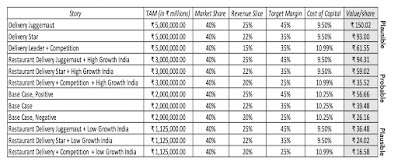

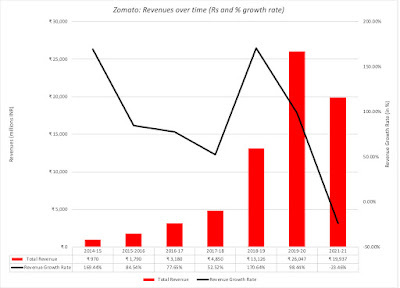

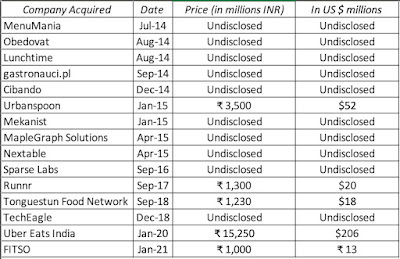

A DIY (Do-It-Yourself) Valuation of Zomato

Just over a week ago, I valued Zomato ahead of its market debut, and as with almost every valuation that I do on this forum, I heard from many of you. Some of you felt that I was being far too generous in my assumptions about market share and profitability, for a company with no history of making money, and that I was over valuing the company. Many others argued that I was understating the growth in the Indian food market and the company's potential to enter new markets, and thus undervaluing the company, a point that the market made even more emphatically by pricing the stock at about three times my estimated value. A few of you posited that I was missing the point entirely, and that Zomato is a trader's game, and that there are plenty of reasons for traders to be optimistic about its future prospects. In this post, rather than impose my story (and value) on you, I offer a template for telling your own story about Zomato, and arriving at your own estimate of value.

The Prelude

After I posted my valuation last week, I did find some of the portrayals of my post to be a little unsettling. Some started by describing me as some kind of valuation luminary, and then proceeding to describe what I did to arrive at value as the result of deeply insightful research. Let me dispel both delusions. First, there is nothing in valuation that merits the use of “expert” or “guru” as a descriptor, since it is for the most part, common sense, layered with a few valuation basics. Second, while valuation practitioners have created their own buzzwords to create an aura of mystery, and added complexities, often with no reason other than to intimidate outsiders, I believe that anyone should be able to value a company, as I hope to show later in this post. There was also some who misread my post to imply that I disliked Zomato as a company, or that I was trying to talk others out of investing in the company. Neither assertion is true, and since they relate to what I view as fundamental truths about investing, let me elaborate:

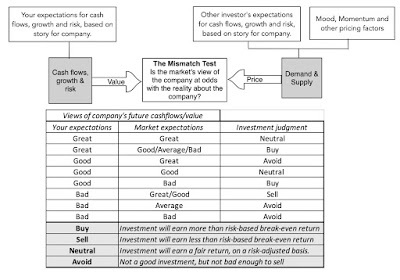

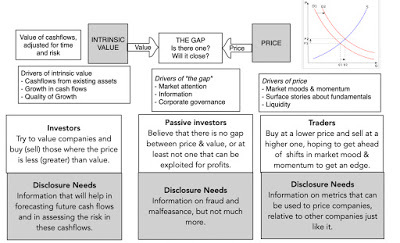

Good Company versus Good Investment: While it is true that, at least in my assessment, Zomato is over priced, making it a bad investment, it does not follow that it is a bad company. I have written about the contrast between good investments and good companies before, but the picture below captures the essence:

In short, your assessment of whether a company is good, average or bad is based upon how you see their business model playing out in future earnings and cash flows, but your assessment of whether it is a good investment depends upon whether your expectations for the company are more positive or negative than the market expectations for that company. My story for Zomato is a very positive one, where the company not only maintains its market share of a growing Indian market, but preserves its profitability, in the face of competition. That is one reason that I emphasized that unlike some, who have concluded that its money-losing status and big ambitions make it a "bad" company, my conclusion is that it is a good company. That said, the market seems to be pricing in the expectation that it will be a great company, and in my view, that judgment is premature.Taking ownership of investment decisions: I value companies for an audience of one, and that audience member is forgiving and understanding, because I see him in the mirror every day. It has always been my belief that as investors, each of us needs to take ownership of our investment decisions, and that buying or selling a company because someone else is doing so, even if that person has legendary investment credentials, is a dereliction of investment due diligence. Thus, if you find Zomato to be cheap and buy it, I have no desire to talk you out of your decision, since it is your money that you are investing, and that decision should be based upon your assessment of the company's prospects, not mine.If investing is all about market price and how it relates to your assessment of value, it follows that there will never be consensus, and that disagreement is not only part and parcel of the process, but a healthy component in good valuation.

Valuation Storytelling: The Feedback Loop

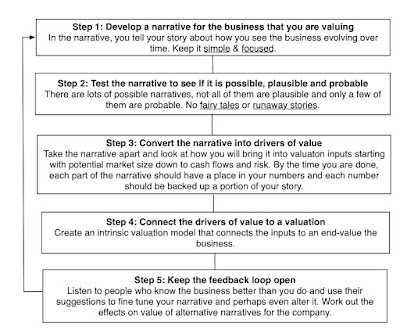

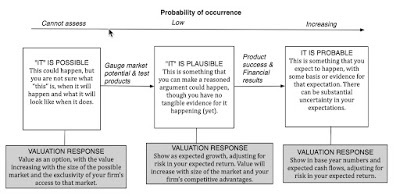

In my valuation of Zomato, I laid out the story that I was telling about the company and how it played out in valuation numbers. It is part of a broader theme that I have harped on for years, which is that a good valuation is a bridge between story and numbers, and in my book on how to build that bridge, I talked about a five-step process: