Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 12

November 5, 2020

A Viral Market Update XIV: A Wrap on the COVID market, premature or not!

Over the last eight months, I have written a series of posts on the market and how it has adapted and adjusted to COVID. The very first of these posts, on February 26, 2020, was about two weeks into the meltdown and it is indicative of how little we knew about the virus then, and what effects it would have on the economy and the market. More than seven months later, there is still much that we still do not know about COVID, as it continues to wreak havoc on global economies and businesses. In this post, I intend to wrap up this series with a final post, reviewing how value has been reallocated across companies during the months, and providing an updated valuation of the S&P 500. Given that much of Europe is going into lockdown, and that there is no vaccine in sight, this may seem premature, but I have a feeling that there will be other uncertainties that will vie for market attention over the coming weeks, especially as the US election results play out in legal and legislative arenas.

A Market Overview

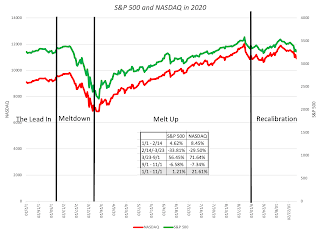

For those of you who have read my prior posts on COVID's market effects, I will follow a familiar script. I will start by noting that this crisis has played out in markets in three acts, captured in the graph below where I look at the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ, since the start of this year:

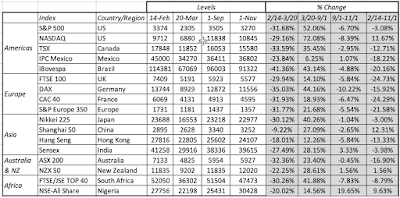

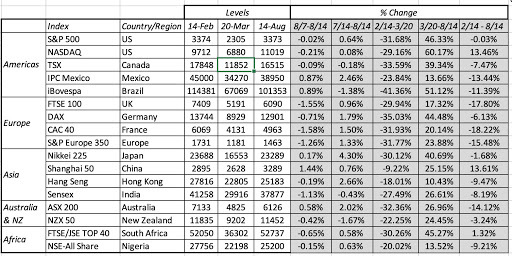

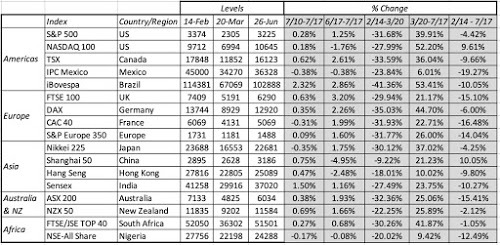

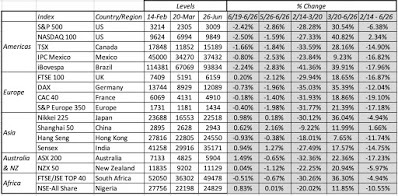

The year began auspiciously for US equities, as stocks built on positive performance in 2019 (when it was up more than 30%) and continued to rise. In fact, on February 14, US equities were are at all time highs, when news of the virus encroaching into Europe and then rapidly expanding across the world caused stocks to go into a tailspin that lasted just over five weeks. On March 23, 2020, amidst talk of doomsday for stocks, momentum shifted, with some credit to the Fed, and stocks went on a run that extended through the end of August, recovering almost all of the ground lost during the meltdown. In September and October, stocks were choppy with more bad days than good, as investors recalibrated. While the graph is US-centric, this was a global crisis, and equities around the global moved through the same three phases, as you can see in the table below, where I look at selected equity indices from around the world:

Download data

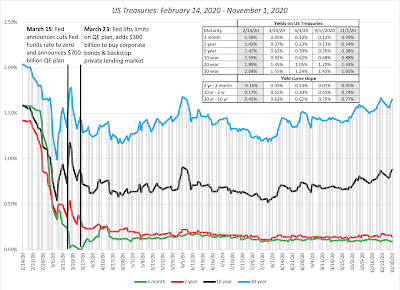

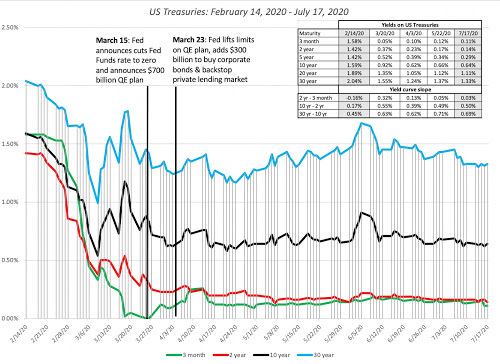

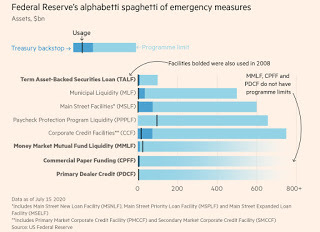

Download dataNote that the pattern is very similar, across indices, with steep drops in the first phase (2/14-3/20), followed by steep increases in the following months (3/20-9/1) before settling down in the last two months (9/1-11/1). As equities went on a turbulent ride, other asset classes were also affected, with US treasuries benefiting from a flight to safety in the first five weeks:

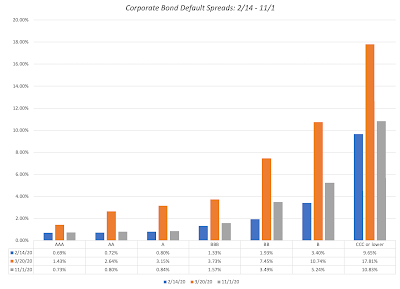

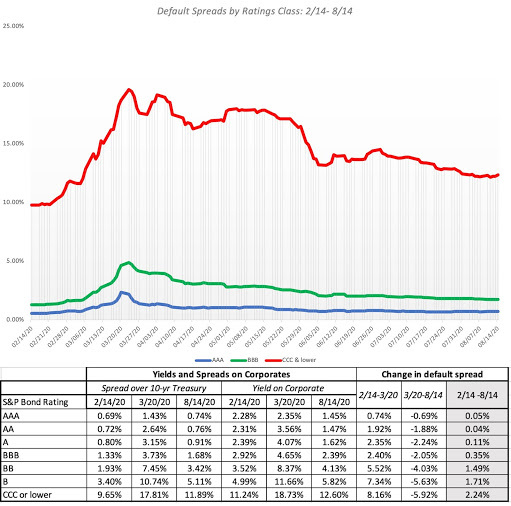

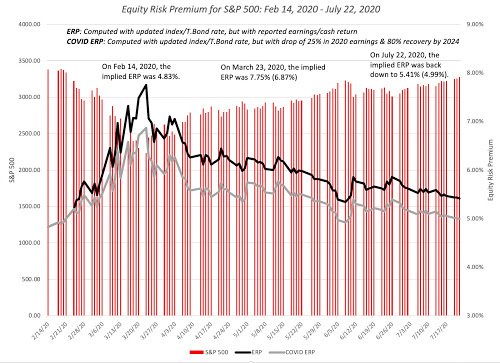

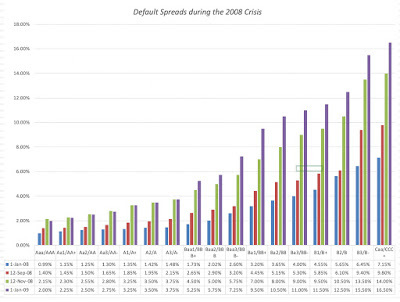

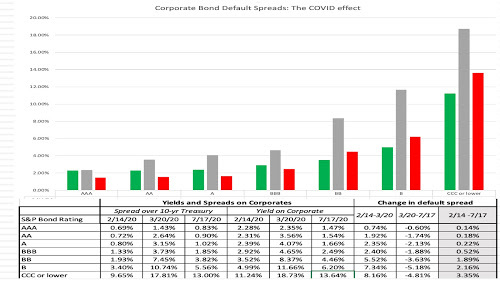

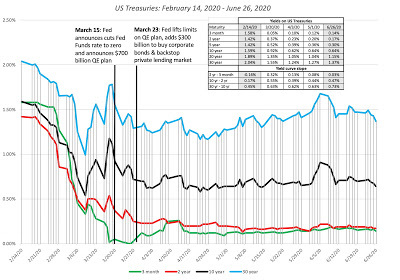

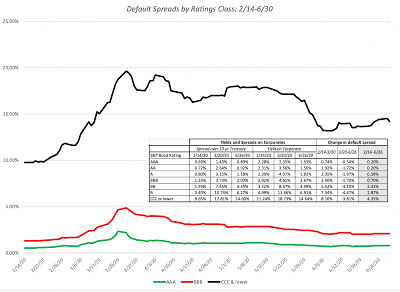

Download dataUS treasury yields dropped across all maturity classes between February 14 and March 20, with short term rates dropping close to zero and 10-year T.Bond rates dropping fro 1.7% to 0.7%. I know it is fashionable now to attribute all things related to interest rates to the Fed's actions, but the bulk of the decline in treasury rates occurred before the Fed finally acted in mid-March, and it is surprising how little movement there has been in treasury rates in the months since. Though treasury yields have stayed at their mid-March levels, the rise and fall of the fear factor in the equity markets also played out in the corporate bonds, in the form of movements in corporate default spreads:

Download dataUS treasury yields dropped across all maturity classes between February 14 and March 20, with short term rates dropping close to zero and 10-year T.Bond rates dropping fro 1.7% to 0.7%. I know it is fashionable now to attribute all things related to interest rates to the Fed's actions, but the bulk of the decline in treasury rates occurred before the Fed finally acted in mid-March, and it is surprising how little movement there has been in treasury rates in the months since. Though treasury yields have stayed at their mid-March levels, the rise and fall of the fear factor in the equity markets also played out in the corporate bonds, in the form of movements in corporate default spreads:

Download data

Download dataWhen stocks were melting down between February 14 and March 20, corporate bond spreads were also widening dramatically, but those spreads have fallen back almost to pre-crisis levels for the higher ratings, and mostly recovered even for the lower ratings.

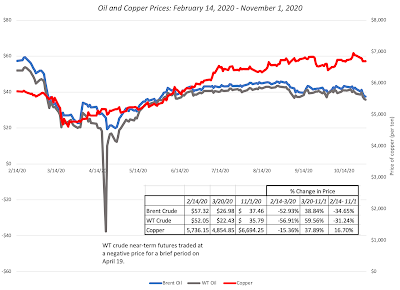

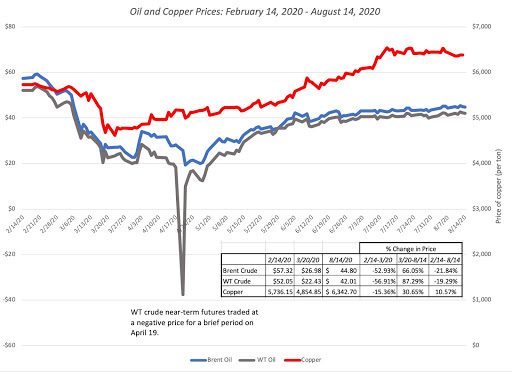

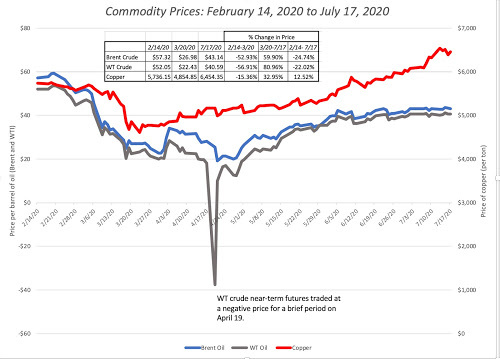

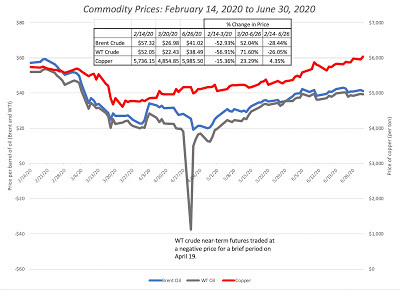

Looking at oil and copper, two economically sensitive commodities, you see reflections of the turbulence that affected equities and corporate bond markets:

Download data

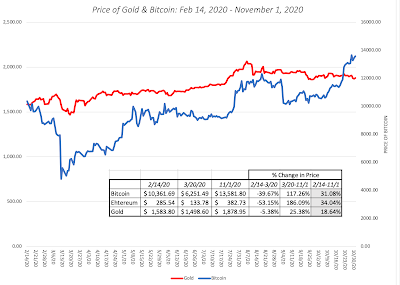

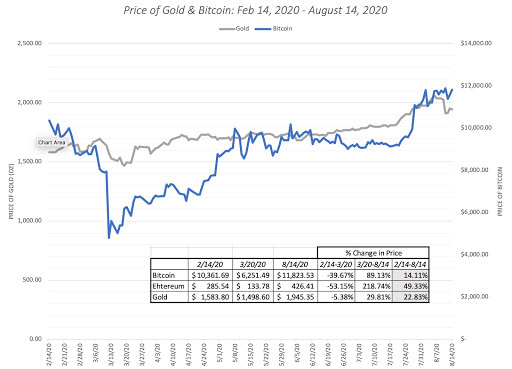

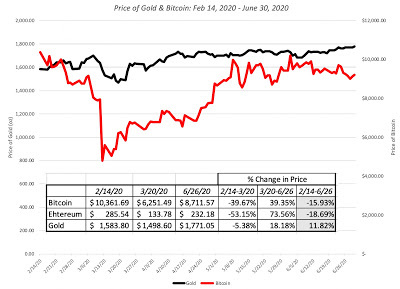

Download dataBoth oil and copper prices dropped significantly between February 14 and March 20, with oil showing a much larger decline (down more than 50%) than copper (about 15%), but both commodities have recovered, with copper now up almost 17% from pre-crisis levels. Oil, in spite of its comeback in the last few months, is still down more than 30% from pre-crisis levels. Finally, I look at gold and bitcoin, an odd pair, but both touted by their advocates as crisis assets:

Download dataWhile bitcoin is now up more than gold over the period, gold has performed better as a crisis asset, holding its own when equities were melting down between February 14 and March 20. In contrast, the crypto currencies (Bitcoin and Ethereum) have behaved like very risky equities, going down more than equities, when stocks were going down, and rising more, when they rose.

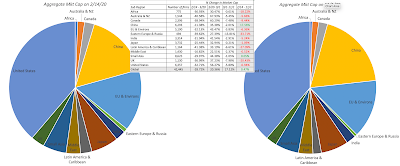

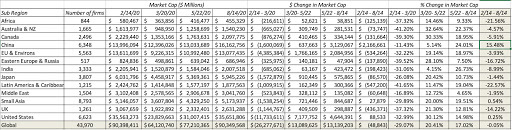

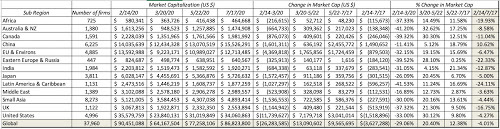

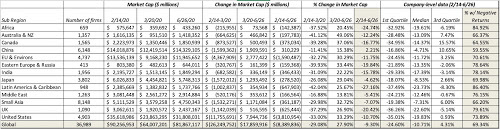

Download dataWhile bitcoin is now up more than gold over the period, gold has performed better as a crisis asset, holding its own when equities were melting down between February 14 and March 20. In contrast, the crypto currencies (Bitcoin and Ethereum) have behaved like very risky equities, going down more than equities, when stocks were going down, and rising more, when they rose.Equity Markets: A Wealth TransferThe quick recovery in equity markets has led some to believe that the market has ignored the crisis, but that is not true. While equity values have recovered globally, there has been a significant shift in value across regions, sectors and company types. While I have talked about this value reallocation in previous posts, I will update the numbers and provide a summary of what the data is showing as of November 1. First, this crisis has played out very differently in different parts of the world, as you can see below, where I break down the market capitalizations of all publicly traded companies, by region, on February 14, 2020 and on November 1, 2020, with a table showing the percentage changes over the period:

Download data

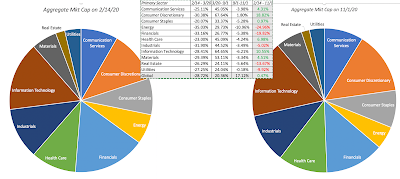

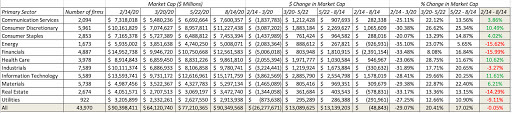

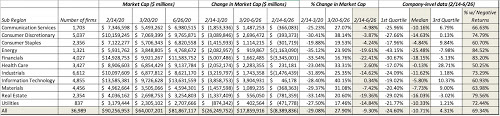

Download dataThe markets that are showing the most residual damage are Africa, Eastern Europe & Russia and Latin America. While the easy explanation is that they are all emerging markets, note that Asia has emerged not just unscathed, but as one of the best performing regions of the world. Among the developed markets, the UK is the worst performer, perhaps dragged down by the continued uncertainty of how Brexit will play out. A better explanation would be that these are regions heavily dependent on natural resource and infrastructure businesses, and as we will see in the next section, those have been adversely affected by this crisis. In addition, since these returns are in US dollars, currency movements add to the effect, with depreciating (appreciating) currencies, against the dollar, worsening (improving) returns. Building on the theme that damage has varied across sections, I break down aggregate market cap by sectors, on February 14 and November 20, in the graph below (also with percent changes over the period:

Download data

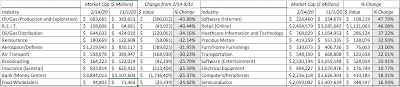

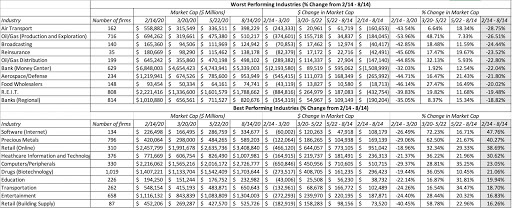

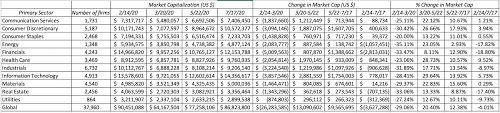

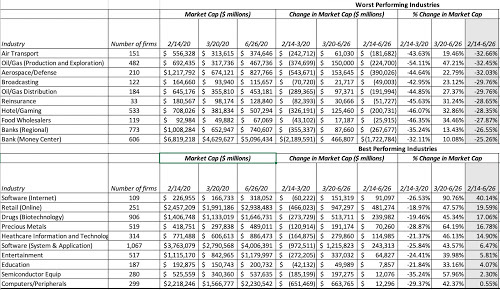

Download dataAgain, the shift in value is clear and decisive, with consumer discretionary, technology and health care gaining at the expense of energy, real estate, utilities and financials. Put simply, capital light businesses have gained at the expense of capital intensive ones, and breaking down sectors into finer industry detail, emphasizes this shift, with the ten best and worst performing industries below:

Download data

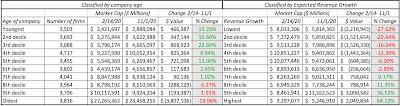

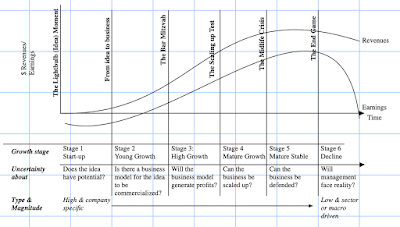

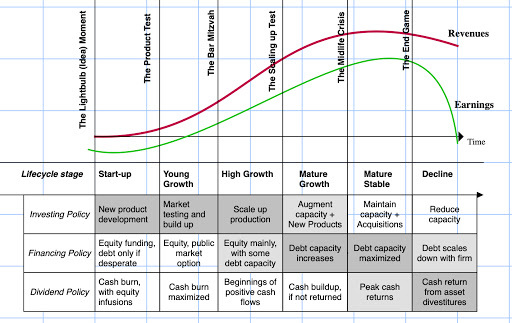

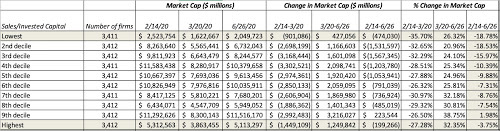

Download dataIn an earlier post, I connected this value shift across industries to corporate life cycles, noting that younger, higher growth companies have gained value at the expense of older, more mature businesses, as can be seen in the tables below, where I break down the value change across companies, first by age, and then by expected revenue growth rate, into deciles:

Download corporate age data & revenue growth data

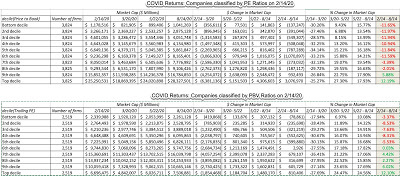

Download corporate age data & revenue growth dataThe youngest companies have gained value over this crisis, whereas the oldest companies have lost value, and high growth companies have benefited at the expense of low growth firms. As this shift has occurred, it is not surprising that the stocks most favored by value investors (low PE/PBV, high dividends) have underperformed the stocks that are most favored by growth investors. I capture this in the table below, where I first look at value changes across companies, first classified across PE ratios and then across dividend yields:

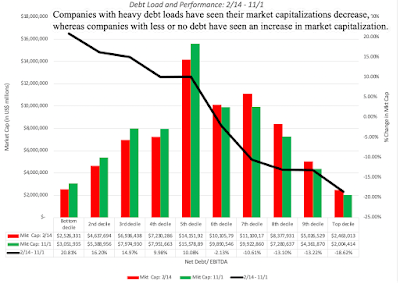

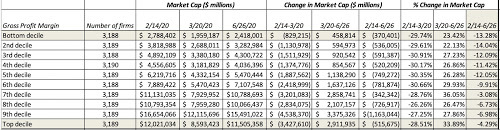

Download PE decile data & Dividend decile dataValue investors have also warned us over the last decade about two trends in corporate behavior, an increase in debt loads at some companies and a surge in stock buybacks. To evaluate whether those warnings were justified, I looked at companies classified by debt load (net debt to EBITDA) into deciles and computed value changes between February 14 and November 1.

Download PE decile data & Dividend decile dataValue investors have also warned us over the last decade about two trends in corporate behavior, an increase in debt loads at some companies and a surge in stock buybacks. To evaluate whether those warnings were justified, I looked at companies classified by debt load (net debt to EBITDA) into deciles and computed value changes between February 14 and November 1.

Download data

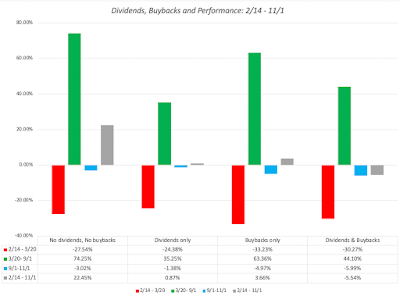

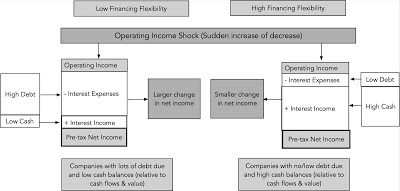

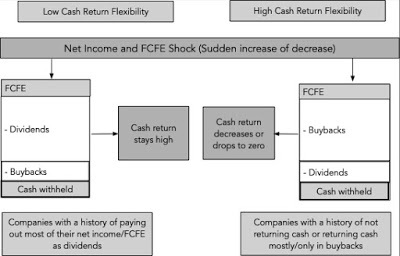

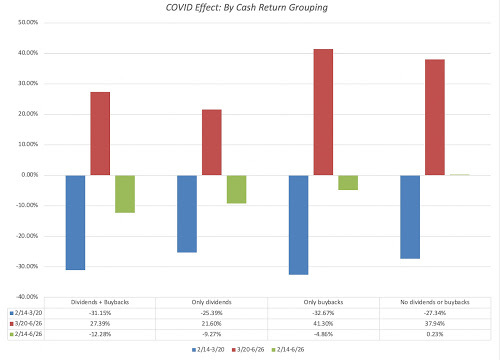

Download dataOn this front, I think that the message is clear that the more indebted a company, the more exposed it was to damage during this crisis. On the buyback front, the results are a little murkier. In the graph below, I look at value changes for four groups of companies, (1) those that returned no cash at all in 2019 (no dividends or buybacks), (2) those that paid only dividends, (3) those that returned cash in the form of buybacks and (4) those that did both:

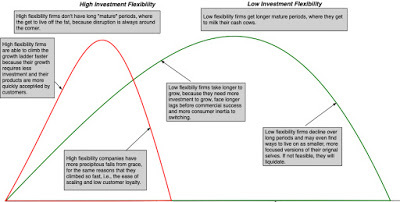

There is a muddled message in this graph. While companies that returned no cash to their shareholders in 2019 fared better overall than companies that returned cash (either in dividends or in buybacks) in 2019, companies that returned cash only in the form of buybacks recovered faster and more completely the companies that paid only dividends. Companies that both paid dividends and bought back stock did worst of all. If flexibility is key to surviving a crisis, it is possible that this crisis will make companies more reluctant to return cash, in general, and when they do, it is also more likely that you will see that cash returned in the form of buybacks than dividends, since the former are easily retracted but the latter are sticky.

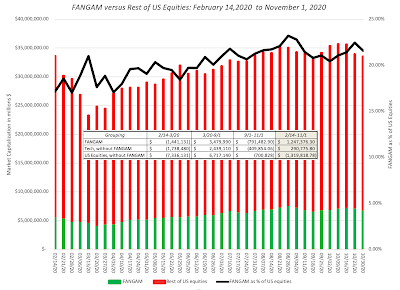

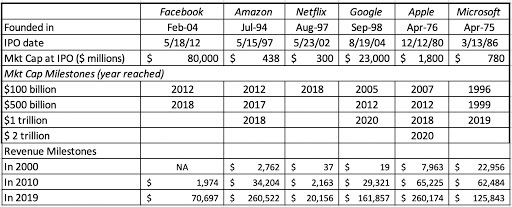

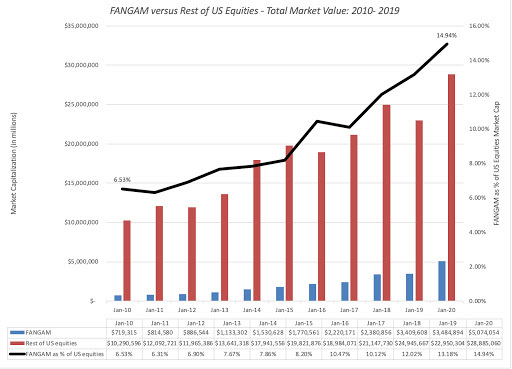

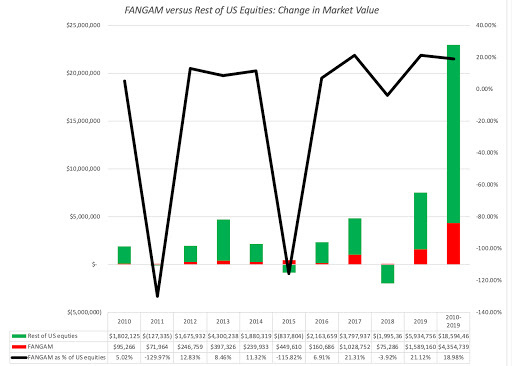

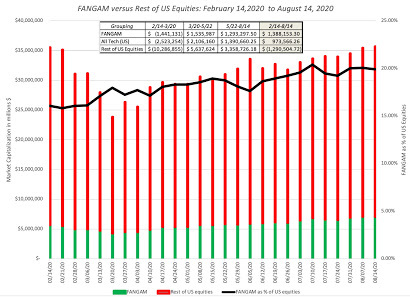

Finally, no post on US equities is complete without a mention of the FANGAM stocks, a topic that I focused on in my last post. Updating the numbers through November 1, here is how these six companies have performed over the crisis, relative to the rest of the market:

Download data

Download dataAs you can see, the FANGAM stocks have added $1.25 trillion in aggregate market cap since February 14, while all other US equities have shed $1.32 trillion over that period. If the market has almost fully recovered from its early swoon, the credit has to go almost entirely to these six companies.

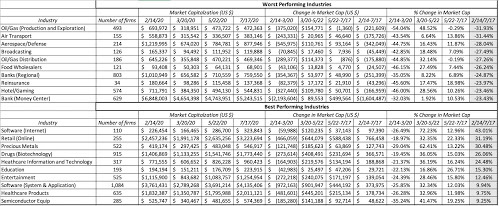

The Resilient Risk Capital ThesisThe best way to summarize how this crisis has affected companies is to summarize the value transfer from what would be consider "risk on" categories (young, high growth, high PE, low or no dividends and high debt) to "risk off" categories (old, low growth, low PE, high dividends and low debt), looking at the top and bottom deciles of each grouping:

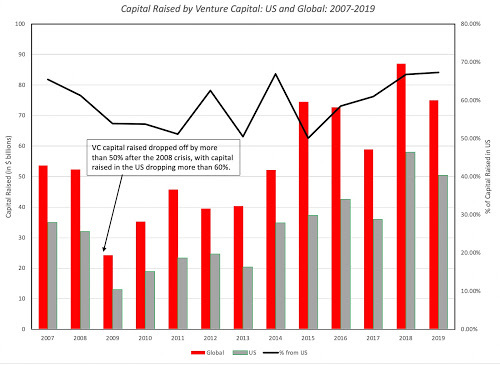

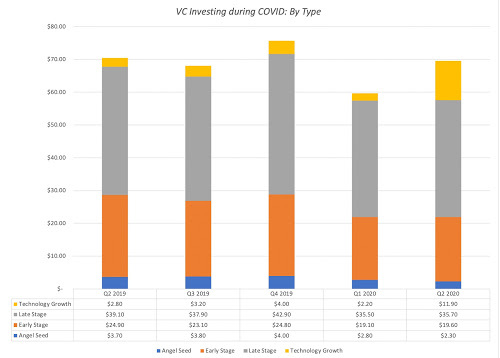

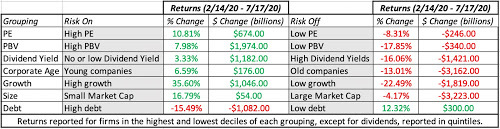

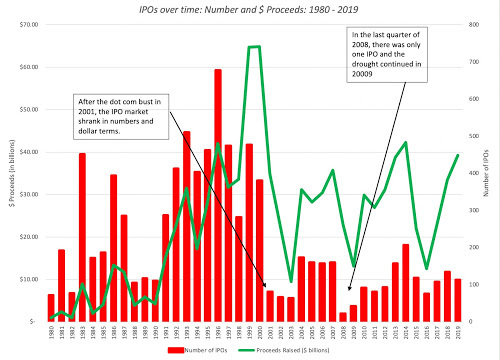

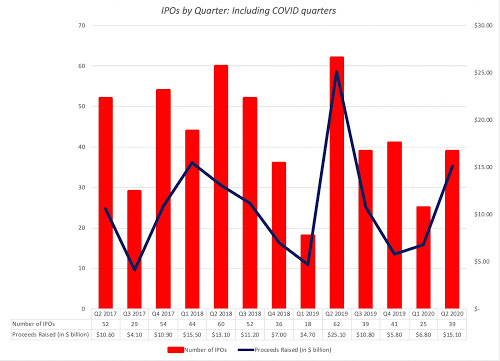

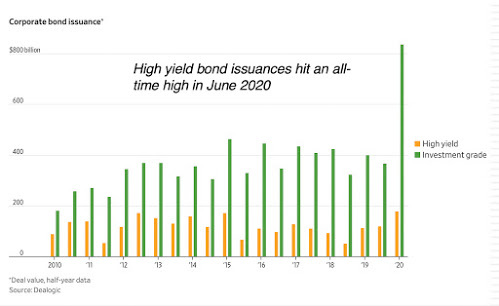

Note that in almost every category, other than debt, the "risk on" group gained value at the expense of the "risk off" group. One explanation that I offered in my post from a few weeks ago was that, unlike prior crises, risk capital (defined as capital invested in the highest risk assets, such as venture capital and investments in below investment grade bonds) has stayed in the game, as can be seen in the behavior of VC fund flows and issuances of high yield bonds (updated to include the third quarter of 2020):

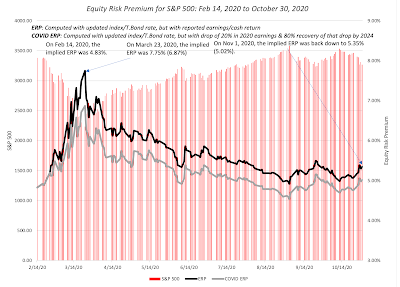

In fact, it is this resilience of risk capital that explains why the equity risk premium for the S&P 500, which soared in the first five weeks of this crisis, has reverted back to pre-crisis levels:

Download data

Download dataPut simply, markets, for better or worse, seem to be sending the message that the fear factor of the crisis has passed, though earnings and cash flows will need to be tweaked.

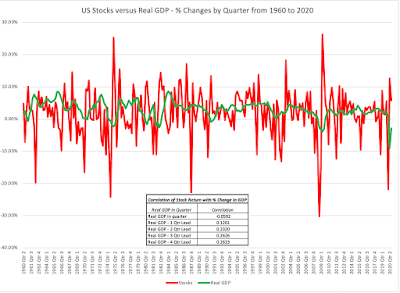

Market Assessment: Predictive Mechanism or Animal SpiritsAs markets have risen over the last few months, there has been a fair amount of hand wringing about animal spirits and irrational exuberance driving markets higher. Some of this concern has come from the clear disconnect between stocks going up and economic malaise, but I noted that this is neither unusual nor unexpected, using this graph of stock returns and real GDP growth, by quarter:

Download data

Download dataLooking at the quarterly data over the last 60 years, there has been little to no relationship between stock returns in a quarter and the GDP change in that quarter, and if there is one, it is mildly negative, i.e., stocks are slightly more likely to go up (down) in a quarter when GDP is down (up). While that may surprise some people, it is entirely understandable, when you recognize that stock markets are predictive mechanisms, and that is borne out by the data, with stock returns becoming positively correlated with GDP growth in future quarters. Note that while the correlation increases as you look three or four quarters ahead, it flattens out at about 0.26 indicating that markets are noisy predictors; they are wrong as often as they are right, but given a choice between trusting markets and going with market gurus, I will take the former every single time.

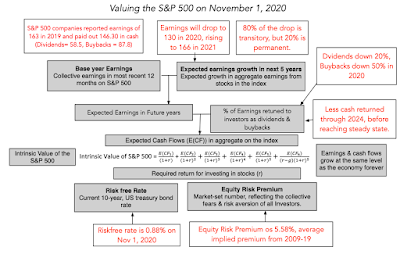

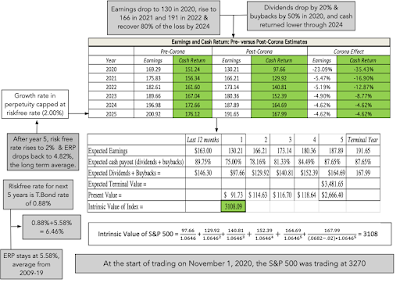

There is a debate to be had about whether markets have over adjusted to the possibility of a vaccine and the economy reopening, and to address that question, I decided to value the S&P 500 again; I did value it on June 1, 2020 and found it to be close to fairly valued. I revisited my assumptions, updating my estimates of earnings for the index in the near years (2020, 2021 and 2022), where the bulk of the damage from this crisis will be done.

Note that in the intervening five months, since my last valuation, analysts tracking the index have become more optimistic about earnings in 2020 and 2021. The resulting valuation reflects these improved estimates:

Download spreadsheet

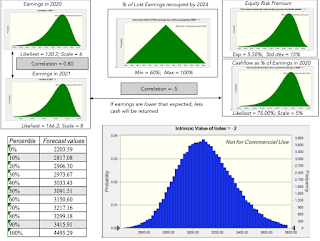

Download spreadsheetBased upon my inputs, I arrive at a value for the index of just over 3100, which would make stocks mildly over valued. I also followed up with a simulation of this valuation, based upon distributions for my key inputs, and the results are below:

Download spreadsheet with simulation results

Download spreadsheet with simulation resultsThe simulation reinforces the findings in the base case valuation. You could make a case that stocks are over valued, and that case will be built on the premise that the economic damage from this crisis will be much greater and long lasting that analysts believe. However, if your argument is that markets have gone crazy and that nothing explains stock prices, you may want to evaluate that view, and consider at least the possibility that your world view (about how the economy will recover and the virus will play out) is wildly at odds with the market consensus. That leaves open the unpleasant possibility that it is you that is being irrational and wrong, not the market.

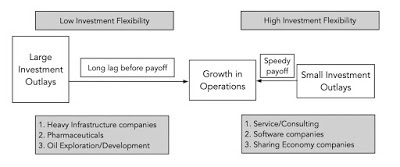

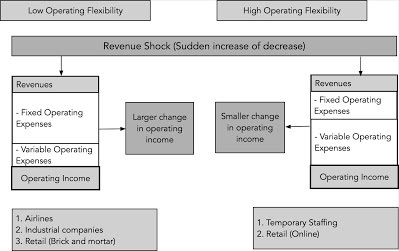

Crisis as Crucible: Lessons learned, unlearned and relearnedEvery crisis is a crucible, exposing what we don't know and putting our faith to the test. This one has been no different, and while I will not tell you that I have enjoyed it, I have learned some lessons from it.Respect markets, even if you disagree with them: Markets are not all knowing and they are definitely not efficient, but they are extraordinary platforms for conveying a consensus view of the future. While you and I may disagree with the market view, and markets can be wrong, it behooves us all to at least try and understand the message that it delivers.Time to move on: For many managers and investors, the COVID crisis is a reminder, sometimes in painful terms, that we are now well into the 21st century and continuing to use tools, techniques and metrics that were developed and tested on 20th century data is a recipe for disaster. That was the underlying message in my posts on value investing from last month.Importance of Flexibility: If you look across what companies that have done well during this crisis share in common, it is flexibility, with companies that can adapt quickly to new circumstances improving their odds of winning. In the same vein, it seems self defeating for companies to borrow too much or lock themselves into paying large dividends, since both reduce their capacity to respond quickly to changed circumstances.All in all, it has been an interesting roller coaster ride over these last few months, and I am glad that you were able to join me for at least some of the ride. It is definitely not over, but I have a feeling it is time for me to move on. There are other attractions at this fair!

YouTube Video

Data

Market data (November 1, 2020)Regional breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)Country breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)Sector breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)Industry breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)PE breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)PBV breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)Dividend Yield breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)Cash Return breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)Age breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)Revenue Growth breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)Debt load breakdown - Market Changes (November 1, 2020)SpreadsheetsValuation of the S&P 500 on November 1, 2020S&P 500 simulation resultsViral Market Update PostsA Viral Market Meltdown: Fear or Fundamentals?A Viral Market Meltdown II: Pricing or Valuing? Investing or Trading?A Viral Market Meltdown III: Clues in the Market DebrisA Viral Market Meltdown IV: Investing for a post-virus EconomyA Viral Market Meltdown V: Back to BasicsA Viral Market Meltdown VI: The Price of RiskA Viral Market Update VII: Market MultiplesA Viral Market Update VIII: Value vs Growth, Active vs Passive, Small Cap vs Large!A Viral Market Update IX: A Do-it-Yourself S&P 500 ValuationA Viral Market Update X: A Corporate Life Cycle PerspectiveA Viral Market Update XI: The Flexibility PremiumA Viral Market Update XII: The Resilience of Private Risk CapitalA Viral Market Update XIII: The Strong (FANGAM) get Stronger!A Viral Market Update XIV: It's a wrap, premature or not!

October 23, 2020

Value Investing III: Requiem, Rebirth or Reinvention?

If you have had the endurance to make your way through my first two posts on value investing, I compliment you on your staying power, but I am sure that, if you are a value investor, you have found my take on it to be unduly negative. In this, my third post, I want to explain why value investing is in trouble and point to ways in which it can be reinvented, to gain new life. I am sure that many of you will disagree both with my diagnosis and my solutions, but I welcome your points of view.

Value Investing: Has it lost its way?

I have never made the pilgrimage to the Berkshire Hathaway meetings, but I did visit Omaha, around the time of the annual meeting, a few years ago, to talk to some of the true believers who had made the trek. I do not think that I will be invited back again, because I argued in harsh terms that value investing had lost its way at three levels.

It has become rigid: In the decades since Ben Graham published Security Analysis, value investing has developed rules for investing that have no give to them. Some of these rules reflect value investing history (screens for current and quick ratios), some are a throwback in time, and some just seem curmudgeonly. For instance, value investing has been steadfast in its view that companies that do not have significant tangible assets, relative to their market value, and that view has kept many value investors out of technology stocks for most of the last three decades. Similarly, value investing's focus on dividends has caused adherents to concentrate their holdings in utilities, financial service companies and older consumer product companies, as younger companies have shifted away to returning cash in buybacks. It has become ritualistic: The rituals of value investing are well established, from the annual trek to Omaha, to the claim that your investment education is incomplete unless you have read Ben Graham's Intelligent Investor and Security Analysis to an almost unquestioning belief that anything said by Warren Buffett or Charlie Munger has to be right. Its has become righteous: While investors of all stripes believe that their "investing ways" will yield payoffs, some value investors seem to feel entitled to high returns because they have followed all of the rules and rituals. In fact, they view investors who deviate from the script as shallow speculators, but are convinced that they will fail in the "long term".Put simply, value investing, at least as practiced by some of its advocates, has evolved into a religion, rather than a philosophy, viewing other ways of investing as not just misguided, but wrong and deserving of punishment.

A New Paradigm for Value Investing

For value investing to rediscover its roots and reclaim its effectiveness, I believe that it has to change in fundamental ways. As I list some of these changes, they may sound heretical, especially if you have spent decades in the value investing trenches.

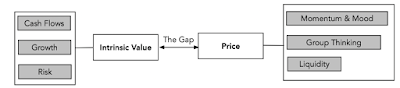

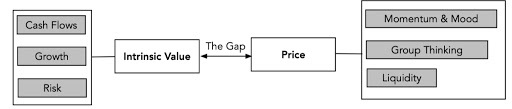

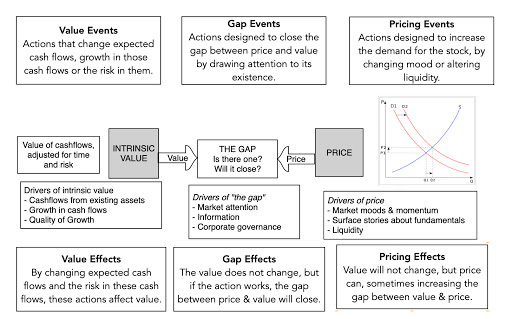

Be clearer about the distinction between value and price: While value and price are often used interchangeably by some market commentators, they are the results of very different processes and require different tools to assess and forecast.

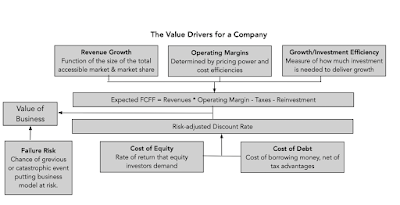

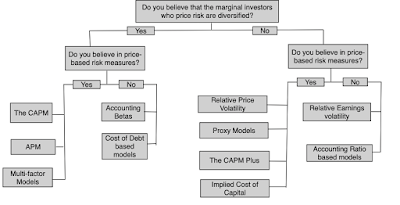

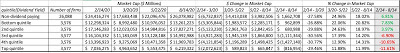

Value is a function of cash flows, growth and risk, and any intrinsic valuation model that does not explicitly forecast cash flows or adjust for risk is lacking core elements. Price is determined by demand and supply, and moved by mood and momentum, and you price an asset by looking at how the market is pricing comparable or similar assets. I am surprised that so many value investors seem to view discounted cash flow valuation as a speculative exercise, and instead pin their analysis on comparing comparing on pricing multiples (PE, Price to book etc.). After all, there should be no disagreement that the value of a business comes from its future cash flows, and the uncertainty you feel about those cash flows, and as I see it, all that discounted cash flow valuation does is bring these into the fold:

It is true that you are forecasting future cash flows and trying to adjust for risk in intrinsic valuation, and that both exercises expose you to error, but I don't see how using a pricing ratio or a short cut makes that error or uncertainty go away. Rather than avoid uncertainty, face up to it: Many value investors view uncertainty as "bad" and "something to be avoided", and it is this perspective that has led them away from investing in growth companies, where you have to grapple with forecasting the future and towards investing in mature companies with tangible assets. The truth is that uncertainty is a feature of investing, not a bug, and that it always exists, even with the most mature, established companies, albeit in smaller doses.

While it is true that there is less uncertainty, when valuing more mature companies in stable markets, you are more likely to find those mistakes in companies where the uncertainty is greatest about the future, either because they are young or distressed, or because the macroeconomic environment is challenging. In fact, uncertainty underlies almost every part of intrinsic value, whether it be from micro to macro sources:

To deal with that uncertainty, value investors need to expand their tool boxes to include basic statistical tools, from probability distributions to decision trees to Monte Carlo simulations. Margin of safety is not a substitute risk measure: I know that value investors view traditional risk and return models with disdain, but there is nothing in intrinsic value that requires swearing allegiance to betas and modern portfolio theory. In fact, if you don't like betas, intrinsic valuation is flexible enough to allow you to replace them with your preferred measures of risk, whether they be based upon earnings, debt or accounting ratios.

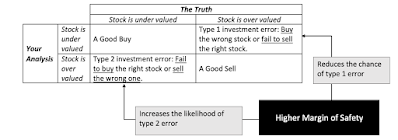

For those value investors who argue that the margin of safety is a better proxy for risk, it is worth emphasizing that the margin of safety comes into play only after you have valued a company, and to value a company, you need a measure of risk. When used, the margin of safety creates trade offs, where you avoid one type of investment mistake for another:

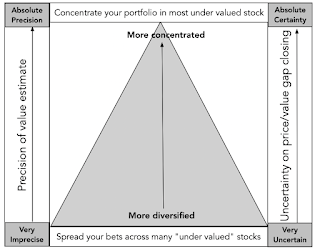

As to whether having a large MOS is a net plus or minus depends in large part on whether value investors can afford to be picky. One simply measure that the margin of safety has been set too high is a portfolio that is disproportionately in cash, an indication that you have set your standards so high that too few equities pass through. Don't take accounting numbers at face value: It is undeniable that value investing has an accounting focus, with earnings and book value playing a central role in investing strategies. There is good reason to trust those numbers less now than in decades past, for a few reasons. One is that companies have become much more aggressive in playing accounting games, using pro forma income statements to skew the numbers in their favor. The second is that as the center of gravity in the economy has shifted away from manufacturing companies to technology and service companies, accounting has struggled to keep up. In fact, it is clear that the accounting treatment of R&D has resulted in the understatement of book values of technology and pharmaceutical companies. You can pick stocks, and be diversified, at the same time: While not all value investors make this contention, a surprisingly large number seem to view concentrated portfolios as a hallmark of good value investing, arguing that spreading your bets across too many stocks will dilute your upside. The choice of whether you want to pick good stocks or be diversified is a false one, since there is no reason you cannot do both. After all, you have thousands of publicly traded stocks to pick from, and all that diversification requires is that rather than put your money in the very best stock or the five best stocks, you should hold the best thirty or forty stocks. My reasoning for diversification is built on the presumption that any investment, no matter how well researched and backed up, comes with uncertainty about the payoff, either because you missed a key element when valuing the investment or because the market may not correct its mistakes. In a post from a few years ago, I presented the choice between concentration and diversification in terms of those two uncertainties, i.e., about value and the price/value gap closing:

I think that value investors are on shaky ground assuming that doing your homework and focusing on mature companies yield precise valuations, and on even shakier ground, when assuming that markets correct these mistakes in a timely fashion. In a market, where even the most mature of companies are finding their businesses disrupted and market momentum is augmented by passive trading, having a concentrated portfolio is foolhardy.Don't feel entitled to be rewarded for your virtue: Investing is not a morality play, and there are no virtuous ways of making money. The distinction between investing and speculating is not only a fine one, but very much in the eyes of the beholder. To hold any investing philosophy as better than the rest is a sign of hubris and an invitation for markets to take you down. If you are a value investor, that is your choice, but it should not preclude you from treating other investors with respect and borrowing tools to enhance your returns. I will argue that respecting other investors and considering their investment philosophies with respect can allow value investors to borrow components from other philosophies to augment their returns. Moving ForwardInvestors, when asked to pick an investment philosophy, gravitate towards value investing, drawn by both its way of thinking about markets and its history of success in markets. While that dominance was unquestioned for much of the twentieth century, when low PE/PBV stocks earned significantly higher returns than high PE/PBV stocks, the last decade has shaken the faith of even diehard value investors. While some in this group see this as a passing phase or the result of central banking overreach, I believe that value investing has lost its edge, partly because of its dependence on measures and metrics that have become less meaningful over time and partly because the global economy has changed, with ripple effects on markets. To rediscover itself, value investing needs to get over its discomfort with uncertainty and be more willing to define value broadly, to include not just countable and physical assets in place but also investments in intangible and growth assets.

YouTube Video

Blog Posts on Value Investing (2020)Value Investing I: The Glory DaysValue Investing II: A Lost DecadeValue Investing III: Rebirth, Reincarnation or Requiem?

Value Investing II: Tough times for Value Investing - Passing Phase or a Changed World?

In the last post, I noted the strong backing for value investing for much of the last century, where a combination of investing success stories and numbers that back those stories allowed it to acquire its lead position among investment philosophies. In this post, I plan to look at the underbelly of value investing, by first going back to the "good old days" for value investing, and probing the numbers more closely to see if even in those days, there were red lights that were being ignored. I will follow up by looking at the last decade (2010-2019), a period where value investing lost its sheen and even long time value investors started questioning its standing, and then extend this discussion to 2020, as COVID has caused further damage. I will close by looking at the explanations for this lost decade, not so much as a post-mortem, but to get a measure of what value investors may need to do, going forward.

The Dark Side of the Good Old DaysFor value investors, nostalgic for the good old days, when the dominance of value investing was unquestioned, I think it is worth pointing out that the good old days were never that good, and that even in those days, there were legitimate questions about the payoff to value investing that remained unanswered or ignored.

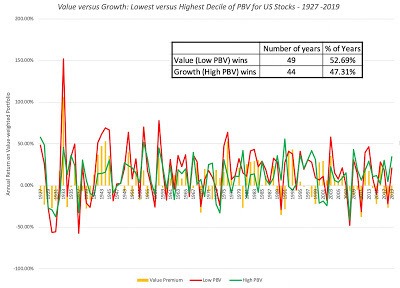

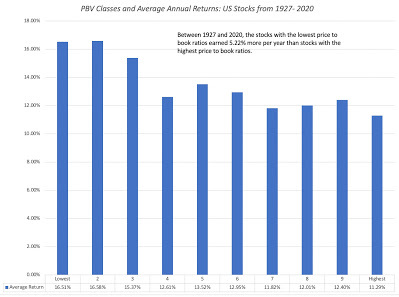

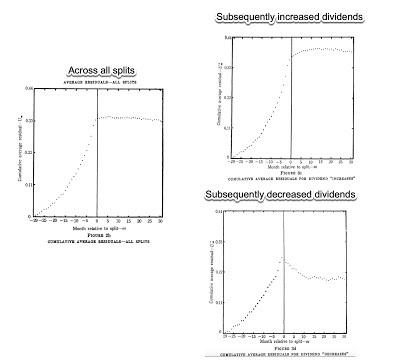

Revisiting the Value PremiumFor some value investors, the graph from my last post, showing that low price to book stocks have outperformed high price to book stocks by more than 5% a year, going back to 1927 in the US, is all the proof they need to conclude that value investing has won the investing game, but even that rosy history has warts that are worth examining. In the graph below, I look at the year-to-year movements in the value premium, i.e. the difference between the annual returns on the lowest and highest deciles of price to book ratios:

Source: Ken French

Source: Ken FrenchWhile it is true that low price to book stocks earned higher annual returns than high price to book stocks over the entire time period, note that there is significant variation over time, and that the high price to book stocks delivered higher returns in 44 of the 93 years of data. In fact, one of the pitches that growth investors made, with some success, during the glory days of value investing was that you could still succeed as a growth investor, if you had the capacity to time the value/growth cycle. In particular, looking back at the data on value versus growth and correlating with other variables, there are two fundamentals that seem to be correlated with whether value or growth investing emerges the winner.

The first is earnings growth, with growth investing beating value investing when earnings growth rates are low, perhaps because growth becomes a scarcer and a bigger driver of value. The other is the slope of the yield curve, i.e., the difference between short term and long term rates, with flatter and downward sloping yield curves associates with growth outperforming and upward sloping yield curves with value outperforming.In short, the fact that value stocks, at least based upon the price to book proxy, delivered higher returns than growth stocks, again using that proxy, obscures the reality that there were periods of time even in the twentieth century, where the latter won out.

Payoff to Active Value InvestingInvesting in low PE or low PBV stocks would not be considered true value investing, by most of its adherents. In fact, most value investors would argue that the while you may start with these stocks, the real payoff to value investing comes in from the additional analysis that you do, whether it be in bringing in other quantitative screens (following up on Ben Graham) and qualitative ones (good management, moats). If we call this active value investing, the true test of value investing then becomes whether following value investing precepts and practices and picking stocks generates returns that exceed the returns on a value index fund, created by investing in low price to book or low PE stocks. Defined thus, the evidence that value investing works has always been weaker than just looking at the top lines, though the strength of the evidence varies depending upon the strand of value investing examined.

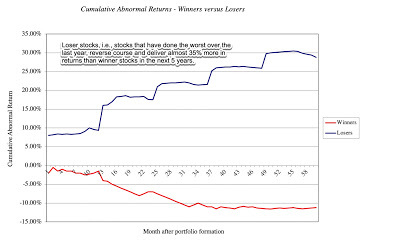

Screening for Value: Since Ben Graham provided the architecture for screening for cheap stocks, it should be no surprise that some of the early research looked at whether Graham's screens worked in delivering returns. Henry Oppenheimer examined the returns on stocks, picked using the Graham screens, between 1970 and 1983, and found that they delivered average annual returns of 29.4% a year, as opposed to 11.5% of the index. There are other studies that do come to the same conclusion, looking at screening over the period, but they all suffer from two fundamental problems. The first is that one of the value screens that invariably gets used is low PE and low PBV, and we already know that these stocks delivered significantly higher returns than the rest of the market for much of the last century, and it is unclear from these studies whether all of the additional screens (Graham has a dozen or more) add much to returns. The second is that the ultimate test of a philosophy is not in whether its strategies work on paper, but in whether the investors who use those strategies make money on actual portfolios. There is many a slip between the cup and the lip, when it comes to converting paper strategies to practical ones, and finding investors who have consistently succeeded at beating the market, using screening, is difficult to do. Contrarian Value: The early evidence on contrarian investing came from looking at loser stocks, i.e., stocks that have gone down the most over a prior period, and chronicling the returns you would earn if you bought these stocks. One of the earliest studies, from the mid 1980s, presented this eye-catching graph, backing up the thesis that loser stocks are investment winners: Source: DeBondt and Thaler,

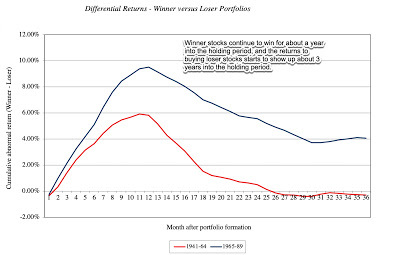

Source: DeBondt and Thaler, Loser stocks, defined as the stocks that have gone down the most in the last year, deliver almost 45% more in returns than winner stocks, defined as stocks that have gone up the most in the last year. Before you jump out and start buying loser stocks, research in subsequent years pointed to two flaws. The first was that many of the loser stocks in the study traded at less than a dollar, and once transactions costs were factored in, the payoff to buying these stocks shrunk significantly. The second came in a different study, which made a case for buying winner stocks with this graph:

Source: Jegadeesh and Titman

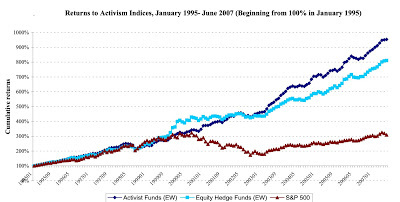

Source: Jegadeesh and TitmanNote that winner stocks continue to win, in both time periods examined, in the first twelve months after the portfolios are created, though those excess returns fade in the months thereafter. Put simply, if you invest in loser stocks and lose your nerve or your faith, and sell too soon, your loser stock strategy will not pay off.Activist Value: Of all of the different strands of value investing, the one that seems to offer the most promise is activist investing, since it is a club that only those with substantial resources can join, with the promise of bringing change to companies. The early results looked promising, as activist hedge funds seemed to offer a greater chance of beating the market than other investing approaches:

Source: Brav (2008)

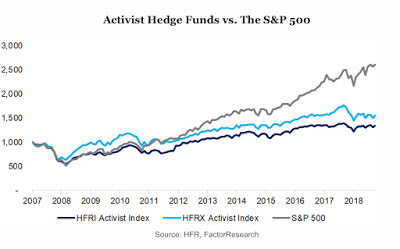

Source: Brav (2008)In the 1995-2007 time period, activist value investors outstripped both hedge funds and the S&P 500, delivering super-sized returns Those numbers, though, are starting to come under strain, as activist investing has widened it search and perhaps lost its focus in the last decade:

Source: CFA Institute

Source: CFA InstituteIn the last decade, the bloom has come off the activist investing rose, as returns from it have dropped off to the point that activist investors, at least in the aggregate, are underperforming the market. The only saving grace is that activist investing is a skewed game, where the winners win really big, and many of the losers drop out.Indexed Value: Many value investors will blanch at the idea of letting indexed value investors into this group, but there can be no denying the fact that funds have flowed into tilted index funds, with many of the tilts reflecting historical value factors (low price to book, small cap, low volatility). The sales pitch for these funds is more often that you can not only get a higher return, because of your factor tilts, but also a bigger bang (return) for your risk (standard deviation) rather than a higher return per se (higher ratios of returns to standard deviation). The jury is still out, and my personal view is that titled index funds are an oxymoron, and that these funds should be categorized as minimalist value funds, where you try to minimize your activity, so as to lower your costs.

The most telling statistics on the failure of value investing come from looking at the performance of mutual fund managers who claim to be its adherents. While the earliest studies of mutual funds looked at them as a group, and concluded that they collectively under performed the market, later studies have looked at mutual funds, grouped by category (small cap vs large cap, value vs growth) to see if fund managers in any of these groupings performed better than managers in other groupings. None of these studies have found any evidence that value fund managers are more likely to beat their index counterparts than their growth fund counterparts. It is telling that value investors, when asked to defend their capacity to add value to investing, almost never reference that research, partly because there is little that they can point to as supportive evidence, but instead fall back on Warren Buffett, as their justification for value investing. As I noted in my last post, there is no doubt about Buffett's success over the decades, but as the man turned ninety this year, it is worth asking whether the continued use of his name is more a sign of weakness in value investing, rather than of strength.

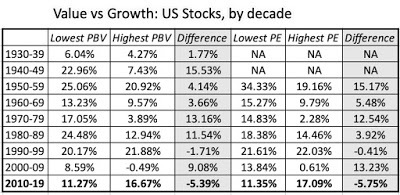

Wandering in the wilderness? Value Investing in the last decadeLooking at my analysis of value investing over the last century, you can accuse me of perhaps nitpicking an overall record of success, but the last decade has, in my view, tested value investing in ways that we have never seen before. To see how much of an outlier this period (2010-2019) has been, take a look at the returns to low and high PBV stocks, by decade:

Source: Ken French

Source: Ken FrenchWhile it is true that the dot-com boom allowed growth stocks to beat out value stocks in the 1990s, the difference was small and bunched up in the last few years of that decade. In the 2010-2019 time period, in the battle between value and growth, it was no contest with growth winning by a substantial amount and in seven of the ten years.

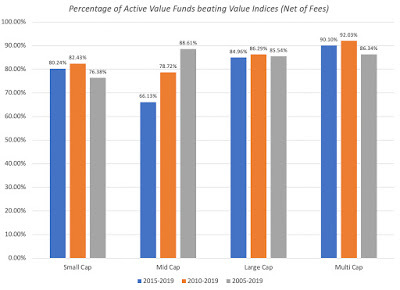

To make things worse, active value investors, at least those that run mutual funds, found ways to underperform even these badly performing indices. Rather than use risk and return models or academic research to back up this proposition, and open up the debate about portfolio theories, I will draw on a much more simplistic but perhaps more effective comparison. One of S&P's most informative measures is SPIVA, where S&P compares the returns of fund managers in different groupings to indices that reflect that grouping (value index for value funds, growth index for growth funds etc.) and reports on the percentage of managers in each grouping that beat the index. Listed below are the SPIVA measures for 2005-2019 for value managers in all different market cap classes (large, mid-sized, small):

Risk Adjusted SPIVA Scorecard (2019)

Risk Adjusted SPIVA Scorecard (2019)Put simply, most value fund managers have had trouble beating the value indices, net of fees. Even gross of fees, the percentages of fund managers beating their indices stays well above 50%.

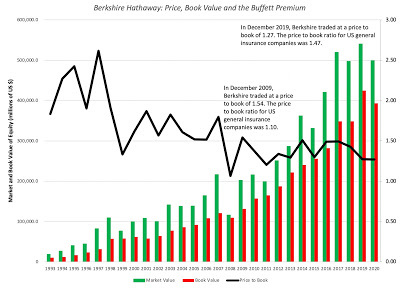

Even legendary value investors lost their mojo during the decade, and even Warren Buffett's stock picking delivered average returns. He abandoned long standing practices, such as using book value as a basis for estimating intrinsic value and never doing buybacks, for good and bad reasons. The best indicator of how the market has also lowered the value it attaches to his stock picking is in a number that has the Buffett imprimatur, the ratio of price to book at Berkshire in the last few years:

Since Berkshire's assets are primarily in publicly traded companies, and these investments have been marked to market for all of this period, one way to look at a portion of the premium that investors are paying over book value is to consider it to be the stock picker premium. Since some of the premium can also be explained by its presence in the insurance business, I compared the price to book for Berkshire to that of general insurance companies listed and traded in the United States. At the start of 2010, Berkshire traded at a price to book ratio of 1.54, well above the US insurance company industry average of 1.10. Ten years later, at the start of 2020, the price to book ratio for Berkshire had dropped to 1.27, below the average of 1.47 for US insurance companies. The loss of the Buffett premium may seem puzzling to those who track news stories about the man, since he is still not only treated as an investing deity, but viewed as the person behind every Berkshire Hathaway decision, from its investment in Apple in 2017 to its more recent one in the Snowflake IPO. My reading is that markets are less sentimental and more realistic in assessing both the quality of his investments (that he is now closer to the average investor than he has ever been) and the fact that at his age, it is unlikely that he is the lead decision-maker at Berkshire anymore.

The COVID shockFor much of the decade, value investors argued that their underperformance was a passing phase, driven by the success of growth and momentum and aided and abetted by the Fed, and that it value investing would come back with a vengeance in a crisis. The viral shock delivered by the Corona Virus early this year seemed to offer an opportunity for value investing, with its emphasis on safety and earnings, to shine.

In the first few weeks, there were some in the value investing camp who argued that following old time value investing precepts and investing in stocks with low PE and Price to book ratios and high dividends would help buffer investors from downside risk. While the logic may have been appealing, the results have not, as can be seen in this table, where I look at stocks classified based upon their PE ratios and Price to Book ratios on February 14, 2020 (at the start of the crisis), and examining the changes in the aggregate market capitalization in the six months following:

The numbers speak for themselves. Low PE and low PBV stocks have lost value during this crisis, just as high PE and PBV stocks have gained in value. Breaking companies down based upon dividend yields, and looking at market capitalization changes yields the following:

The results are perverse, at least from a value investing perspective, since the stocks that have done best in this crisis are non-dividend paying, high PE stocks, and the stocks that have done worst during the crisis have been high dividend paying, low PE stock.

The ExplanationsThe attempt to explain what happened to value investing in the last decade (and during COVID) is not just about explaining the past, since the rationale you provide will inform whether you will continue to adhere to old time value investing rules, modify them to reflect new realities or abandon them in search of new ones. In particular, there are four explanations that I have heard from value investors for what were wrong during the last decade, and I will list them in their order of consequence for value investing practices, from most benign to most consequential.

This is a passing phase!Diagnosis: Even in its glory days, during the last century, there were extended periods (like the 1990s) when low PE and low PBV stocks underperformed, relative to high PE and high PBV stocks. Once those periods passed, they regained their rightful place at the top of the investing heap. The last decade was one of those aberrations, and as with previous aberrations, it too shall pass!Prescription: Be patient. With time, value investing will deliver superior returns.The Fed did it!Diagnosis: Starting with the 2008 crisis and stretching into the last decade, central banks around the world have become much more active players in markets. With quantitative easing, the Fed and other central banks have contributed not only to keeping interest rates lower (than they should be, given fundamentals) but also provided protection for risk taking at the expense of conservative investing. Prescription: Central banks cannot keep interest rates low in perpetuity, and even they do not have the resource to bail out risk takers forever. Eventually, the process will blow up, causing currencies to lose value, government budgets to implode and inflation and interest rates to rise. When that happens, value investors will find themselves less hurt than other investors.The Investment World has become flatter!Diagnosis: When Ben Graham listed his screens for finding good investments in 1949, running those screens required data and tools that most investors did not have access to, or the endurance to run. All of the data came from poring over annual reports, often using very different accounting standards, the ratios had to be computed with slide rules or on paper, and the sorting of companies was done by hand. Even into the 1980s, access to data and powerful analytical tools was restricted to professional money managers and thus remained a competitive advantage. As data has become easier to get, accounting more standardized and analytical tools more accessible, there is very little competitive advantage to computing ratios (PE, PBV, debt ratio etc.) from financial statements and running screens to find cheap stocks. Prescription: To find a competitive edge, value investors have to become creative in finding new screens that are either qualitative or go beyond the financial statements or in finding new ways of processing publicly accessible data to find undervalued stocks. The global economy has changed!Diagnosis: At the risk of sounding cliched, the shift in economic power to more globalized companies, built on technology and immense user platforms, has made many old time value investing nostrums useless. Prescription: Value investing has to adapt to the new economy, with less of a balance sheet focus and more flexibility in how you assess value. Put simply, investors may have to leave their preferred habitat (mature companies with physical assets bases) in the corporate life cycle to find value.From listening to value investors across the spectrum, there does not seem to be a consensus yet on what ails it, but the evolution in thinking has been clear. As the years of under performance have stretched on, there are fewer value investors who believe that this is a passing phase and that all that is needed is patience. There are many value investors who still blame the Fed (and other central banks) for their underperformance, and while I agree with them that central banks have sometimes over reached and skewed markets, I also think that this belief has become a convenient excuse for not looking at the very real problems at the heart of value investing. Especially after the COVID experience, there are at least some value investors who are willing to consider the possibility that it is time to change the way we practice value investing. In my next post, I will look at some of these changes.YouTube Video

Blog Posts on Value Investing (2020)Value Investing I: The Glory DaysValue Investing II: A Lost DecadeValue Investing III: Rebirth, Reincarnation or Requiem?

Value Investing I: The Back Story

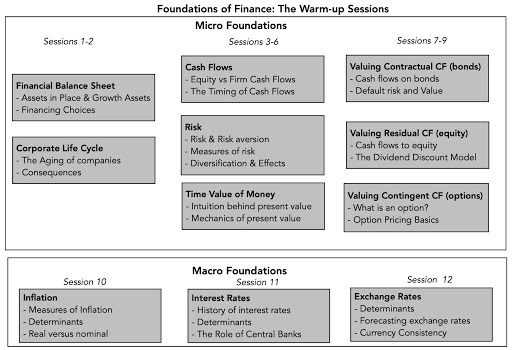

One of the classes that I teach is on investment philosophies, where I begin by describing an investment philosophy as a set of beliefs about how markets work (and sometimes don't) which lead to investment strategies designed to take advantage of market mistakes. Unlike some, I don't believe that there is a single "best" philosophy, since the best investment philosophy for you is the one that best fits you as a person. It is for that reason that I try to keep my personal biases and choices out, perhaps imperfectly, of the investment philosophies, and use the class to describe the spectrum of investment philosophies that investors have used, and some have succeeded with, over time. I start with technical analysis and charting, move on to value investing, then on to growth investing, and end with information trading and arbitrage. The most common pushback that I get is from old-time value investors, arguing that there is no debate, since value investing is the only guaranteed way of winning over the long term. Embedded in this statement are a multitude of questions that deserve to be answered:

What is value investing and what do you need to do to be called a value investor?Where does this certitude that value investing is the "winningest" philosophy come from? Is it deserved?How long is the long term, and why is it guaranteed that value investing wins?I will argue over the course of the next few posts that the answers to these questions are not only more nuanced than many true believers posit them to be, but also that changes in economies and markets are undercutting key components of the value investing case. In this post, I will focus on defining value investing and on the roots of its allure.What is value investing?

Given how widely data services tracking mutual funds and active investing seem to be able classify funds and investors into groupings. how quickly prognosticators are able to pass judgment on value investing's successes and failures and how much academics have been able to write about and opine on value investing in the last few decades, you would think that there is consensus now on what comprises value investing, and how to define it. But you would be wrong! The definition of value investing varies widely even among value investors, and the differences are not often deep and difficult to bridge.

In this section, I will start by providing three variants on value investing that I have seen used in practice, and then go on to explore a way to find commonalities.

Lazy Value Investing: Let's start with the easiest and most simplistic definition, and the one that many data services and academics continue to use, simply because it is quantifiable and convenient, and that is to base whether you are a value or growth investor on whether the stocks you buy trade at low or high multiples of earnings or book value. Put simply, if you consistently invest in stocks that trade at low PE and low price to book ratios, you are a value investor, and if you do not, you are not one. Cerebral Value Investing: If you use the lazy definition of value investing as just buying low PE and low PBV stocks with a group of Omaha-bound value investors, you will get pushback from them. They will point to value investing writing, starting with Graham and buffered by Buffett's annual letters to shareholders, that good value investing starts by looking at cheapness (PE and PBV) but also includes other criteria such as good management, solid moats or competitive advantages and other qualitative factors. Big Data Value Investing: Closely related to cerebral value investing in philosophy, but differing in its roots is a third and more recent branch of value investing, where investors start with the conventional measures of cheapness (low PE and low PBV) but also look for additional criteria that has separated good investments from bad ones. Those criteria are found by poring over the data and looking at historical returns, a path made more accessible by access to huge databases and powerful statistical tools.In my book on value investing, I take a different twist to value investing, arguing that value investors can be broadly classified into four groups, depending on how they approach finding bargains:Passive Value Investing: In passive value investing, you screen for the best stocks using criteria that you believe will improve your odds. Once you buy these stocks, you are asked to be patient, and in some cases, to just buy and hold, and that your patience will pay off as higher returns and a more solid portfolio. To see this approach play out, at least in the early days of value investing, take a look at these screens for good stocks that Ben Graham listed out in 1939 in his classic book on the intelligent investor. These screens have evolved in the years since, in two ways. The first is with the introduction of more qualitative screens, like "good" management, where notwithstanding attempts to measure goodness, there will be disagreements. The second is to use increased access to data, both from the company and about it, to both test existing screens and to add to them. Contrarian Value Investing: In contrarian value investing, you focus your investing energies on companies that have seen steep drops in stock prices, with the belief that markets tend to overreact to news, and that corrections will occur, to deliver higher returns, across the portfolio. Within this approach, access to data has allowed for refinements that, at least on paper, deliver higher and more sustained returns. Activist Value Investing: In activist value investing, you target companies that are not only cheap but badly run, and then expend resources (and you need a considerable amount of those) to push for change, either in management practices or in personnel. The payoff to activist value investing comes from activist investors being the catalysts for both price change in the near term, as markets react to their appearance, and to changes in how the company is run, in the long term.Minimalist Value Investing: There is a fourth approach to value investing that perhaps belongs more within passive investing, but for the moment, I will set it apart. In the last decade or two, we have seen the rise of titled index funds and ETFs, where you start with an index fund or ETF, and tilt the fund/ETF by overweighting value stocks (high PE/PBV, for instance) and underweighting non-value stocks.At this stage, if you are completely confused about what a value investor is, I don't blame you, but there is a more general approach to framing value investing that encompasses all these approaches, and allows you to differentiate it from its most direct competitor, which is growth investing. That approach draws on a structure that I have used repeatedly in my writing and teaching, which is the use of a financial (as opposed to an accounting) balance sheet to describe companies:

Put simply, the contrast between value and growth investing is not that one cares about value and the other does not, but in what part of the company the "value error" lies. Value investors believe that their tools and data are better suited to finding mistakes in valuing assets in place, and that belief leads them to focus in on more mature companies, that derive the bulk of their value from existing investments. Growth investors, on the other hand, accept that valuing growth is more difficult and more imprecise, but argue that it is precisely because of these difficulties that growth assets are more likely to be mis-valued.

Is value investing the winningest philosophy?

While it is not uncommon for investors of all stripes to express confidence that their approach to investing is the best one, it is my experience that value investors express not just confidence, but an almost unquestioning belief, that their approach to investing will win in the end. To see where this confidence comes from, it is worth tracing out the history of value investing over the last century, where two strands, one grounded in stories and practice and the other in numbers and academic, connected to give it a strength that no other philosophy can match.

The Story Strand

When stock markets were in their infancy, investors faced two problems. The first was that there were almost no information disclosure requirements, and investors had to work with whatever information they had on companies, or on rumors and stories. The second was that investors, more using to pricing bonds than stocks, drew on bond pricing methods to evaluate stocks, giving rise to the practice of paying dividends (as replacements for coupons). That is not to suggest that there were not investors who were ahead of the game, and the first stories about value investing come out of the damage of the Great Depression, where a few investors like Bernard Baruch found a way to preserve and even grow their wealth. However, it was Ben Graham, a young associate of Baruch, who laid the foundations for modern value investing, by formalizing his approach to buying stocks and investing in 1934 in Security Analysis, a book that reflected his definition of an investment as "one which thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and adequate return". In 1938, John Burr Williams wrote The Theory of Investment Value, introducing the notion of present value and discounted cash flow valuation. Graham's subsequent book, The Intelligent Investor, where he elaborated his more developed philosophy of value investing and developed a list of screens, built around observable values, for finding under valued stocks.

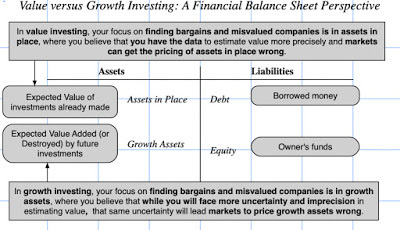

While Graham was a successful investor, putting many of his writings into practice, I would argue that Graham's greater contribution to value investing came as a teacher at Columbia University. While many of his students have acquired legendary status, one of them, Warren Buffett has come to embody value investing. Buffett started an investment partnership, which he dissolved (famously) in 1969, arguing that given a choice between bending his investment philosophy and finding investments and not investing, he would choose the latter. These words, in his final letter to partners in May 1969, more than any others have cemented his status in value investing: "I just don't see anything available that gives any reasonable hope of delivering such a good year and I have no desire to grope around, hoping to "get lucky" with other people's money. He did allow his partners a chance to receive shares in a struggling textile maker, Berkshire Hathaway, and the rest, as they say, is history, as Berkshire Hathaway morphed into an insurance company, with an embedded closed end mutual fund, investing in both public and some private businesses, run by Buffett. While Buffett has been generous in his praise for Graham, his approach to value investing has been different, insofar as he has been more willing to bring in qualitative factors (management quality, competitive advantages) and to be more active (taking a role in how the companies he has invested in are run) than Graham was. If you had invested in Berkshire Hathaway in 1965 or soon after, and had continued to hold through today, you would be incredibly wealthy:

Source: Berkshire Annual Report for 2019 (with a Sept 2020 update)

Source: Berkshire Annual Report for 2019 (with a Sept 2020 update)The numbers speak for themselves and you don't need measures of statistical significance to conclude that these are not just unusually good, but cannot be explained away as luck or chance. Not only did Berkshire Hathaway deliver a compounded annual return that was double that of the S&P 500, it did so with consistency, outperforming the index in 37 out of 55 years. It is true that the returns have looked a lot more ordinary in the last two decades, and we will come back to examine those years in the next post.

Along the way, Buffett has proved to be an extraordinary spokesperson for value investing, not only by delivering mind-blowing returns, but also because of his capacity to explain value investing in homespun, catchy letters to shareholders each year. In 1978, he was joined by Charlie Munger, whose aphorisms about investing have been just as effective at getting investor attention, and were captured well in this book. There have been others who have worn the value investing mantle successfully, and I don't mean to discount them, but it is difficult to overstate how much of value investing as we know it has been built around Graham and Buffett. The Buffett legend has been burnished not just with flourishes like the 1969 partnership letter but by the stories of the companies that he picked along the way. Even novice value investors will have heard the story of Buffett's investment in American Express in 1963, after its stock price collapsed following a disastrous loan to scandalous salad oil company, and quickly doubled his investment.

The Numbers Strand

If all that value investing had for it were the stories of great value investors and their exploits, it would not have the punch that it does today, without the help of a numbers strand, ironically delivered by the very academics that value investors hold in low esteem. To understand this contribution, we need to go back to the 1960s, when finance as we know it, developed as a discipline, built around strong beliefs that markets are, for the most part, efficient. In fact, the capital asset pricing model, despised by value investors, also was developed in 1964, and for much of the next 15 years, financial researchers worked hard trying to test the model. To their disappointment, the model not only revealed clear weaknesses, but it consistently misestimated returns for classes of stock. In 1981, Rolf Banz published a paper, showing that smaller companies (in terms of market capitalization) delivered much higher returns, after adjusting for risk with the CAPM, than larger companies. Over the rest of the 1980s, researchers continued to find other company characteristics that seemed to be systematically related to "excess" returns, even though theory suggested that they should not. (It is interesting that in the early days, these systematic irregularities were called anomalies and non inefficiencies, suggesting that it was not markets that were mispricing these stocks but researchers who were erroneously measuring risk.)

In 1992, Fama and French pulled all of these company characteristics together in a study, where they reversed the research order. Rather than ask whether betas, company size or profitability were affecting returns, they started with the returns on stocks and backed into the characteristics that were strongest in explaining differences across companies. Their conclusion was that two variables, market capitalization (size) and book to market ratios explained the bulk of the variation in stock returns from 1963 to 1990, and that the other variables were either subsumed by these or played only a marginal role in explaining differences. For value investors, long attuned to book value as a key metric, this research was vindication of decades of work. In fact, the relationship between returns over time and price to book ratios still takes pride of place in any sales pitch for value investing, and Ken French has been kind enough to keep updating and making accessible the data on the Fama-French factors, allowing me to provide you with an updated version of the link between returns and price to book ratios:

Source: Ken French

Source: Ken FrenchThat study has not only been replicated multiple times with US stocks, and there is evidence that if you back in time, low price to book stocks earn premium returns in much of the rest of the world. Dimson, Marsh and Staunton, in their comprehensive and readable annual update on global market returns, note that the value premium (the premium earned by low price to book stocks, relative to the market) has been positive in 16 of the 24 countries that they have returns for more than a century and amounted to an annual excess return of 1.8%, on a global basis.

While value investors are quick to point to these academic studies as backing for value investing, they are slower to acknowledge the fact that among researchers, there is a clear bifurcation in what they see as the reasons for these value premium:

It is a proxy for missed risk: In their 1992 paper, Fama and French argued that companies that trade at low price to book ratios are more likely to be distressed and that our risk and return models were not doing an adequate job of capturing that risk. They and others who have advanced the same type of argument would argue that rather than be a stamp of approval for value investing, these studies indicate risks that may not show up in near term returns or in traditional risk and return models, but eventually will manifest themselves and cleanse the excess returns. Put simply, in their world, value investors will look like they are beating the market, until these unseen risks show up and mark down their portfolios.It is a sign of market inefficiency: During the 1980s, as behavioral finance became more popular, academics also became more willing to accept and even welcome the notion that markets make systematic mistakes and that investors less susceptible to these behavioral quirks could take advantage of these mistakes. For these researchers, the findings that low price to book stocks were being priced to earn higher returns gave rise to theories of how investor irrationalities could explain these returns. It is the latter group that reinforces the opinion that value investors have that they are better than the rest of the market and that the excess returns that they earned were a reward for their patience and careful research. i.e., being the grown-ups in a world filled with juvenile and impulsive traders.The End Result

When valuing companies, I talk about how value is a bridge between stories and numbers, and how the very best and most valuable companies represent an uncommon mix of strong stories backed up by strong numbers. In the realm of investment philosophies, value investing has had that unique mix work in its favor, with stories of value investors and their winning stocks backed up by numbers on how well value investing does, relative to other philosophies. It is therefore no surprise that many investors, when asked to describe their investment philosophies, describe themselves as value investors, not just because of its winning track record, but also because of its intellectual and academic backing.

YouTube Videos

September 21, 2020

Sounding good or Doing good? A Skeptical Look at ESG

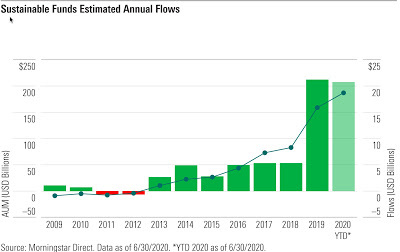

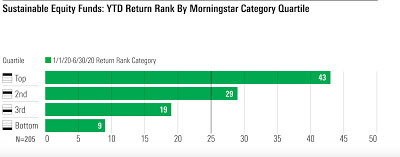

In my time in corporate finance and valuation, I have seen many "new and revolutionary" ideas emerge, each one marketed as the solution to all of the problems that businesses face. Most of the time, these ideas start by repackaging an existing concept or measure and adding a couple of proprietary tweaks that are less improvement and more noise, then get acronyms, before being sold relentlessly. With each one, the magic fades once the limitations come to the surface, as they inevitably do, but not before consultants and bankers have been enriched. So, forgive me for being a cynic when it comes to the latest entrant in this game, where ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance), a measure of the environment and social impact of companies, has become one of the fastest growing movements in business and investing, and this time, the sales pitch is wider and deeper. Companies that improve their social goodness standing will not only become more profitable and valuable over time, we are told, but they will also advance society's best interests, thus resolving one of the fundamental conflicts of private enterprise, while also enriching investors. This week, the ESG debate has come back to take main stage, for three reasons.

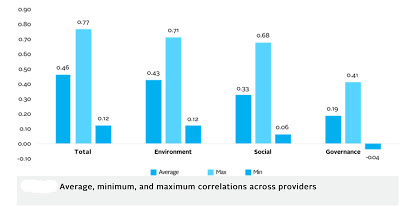

It is the fiftieth anniversary of one of the most influential opinion pieces in media history , where Milton Friedman argued that the focus of a company should be profitability, not social good. There have been many retrospectives published in the last week, with the primary intent of showing how far the business world has moved away from Friedman's views. There were multiple news stories about how "good" companies, with goodness measured on the social scale, have done better during the COVID crisis, and how much money was flowing into ESG funds, with some suggesting that the crisis could be a tipping point for companies and investors, who were on the fence about the added benefits of being socially conscious. In a more long standing story line, the establishment seems to have bought into ESG consciousness, with business leaders in the Conference Board signing on to a "stakeholder interest" statement last year and institutional investors shifting more money into ESG funds.In the interests of openness, I took issue with the Conference Board last year on stakeholder interests, and I start from a position of skepticism, when presented with "new" ways of business thinking. If the debate about ESG had been about facts, data and common sense, and ESG had won, I would gladly incorporate that thinking into my views on corporate finance, investing and valuation. But that has not been the case, at least so far, simply because ESG has been posited by its advocates as good, and any dissent from the party line on ESG (that it is good for companies, investors and society) is viewed as a sign of moral deficiency. At the risk of sounding being labeled a troglodyte (I kind of like that label), I will argue that many fundamental questions about ESG have remained unanswered or have been answered sloppily, and that it is in its proponents' best interests to stop overplaying the morality card, and to have an honest discussion about whether ESG is a net good for companies, investors and society.Measures of Goodness We have spent decades measuring financial performance and output at companies, either at the operating level, as revenues, profits or capital invested, or at the investor level, as market cap and returns. Any attempts to measure environment and social goodness face two challenges. The first is that much of social impact is qualitative, and developing a numerical value for that impact is difficult to do. The second is even trickier, which is that there is little consensus on what social impacts to measure, and the weights to assign to them. If your counter is that there are multiple services now that measure ESG at companies, you are right, but the lack of clarity and consensus results in the companies being ranked very differently by different services. This shows up in low correlations across the ESG services on ESG scores, as indicated by this study:

Correlations across six ESG data providers

Correlations across six ESG data providers

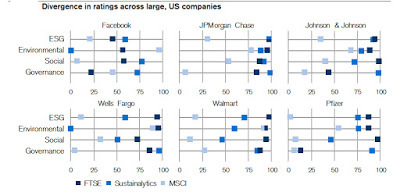

This low correlation often occurs even on high profile companies, as shown in a comprehensive analysis of ESG investing by Dimson, Marsh and Staunton, as part of their global investment returns update:

Source:

CS Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2020, Dimson, Marsh and Staunton

Source:

CS Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2020, Dimson, Marsh and Staunton

Note the divergence in both the overall ratings and on the individual metrics (E, S and G) across the services, even for widely tracked companies like Facebook and Walmart. There are some who believe that this reflects a measurement process that is still evolving, and that as companies provide more disclosure on ESG data and ESG measurement services mature, there will be consensus. I don't believe it! After all, what I find to be good or bad in a company will reflect my personal values and morality scales, and the choices I make will be different from your choices, and any notion that there will be consensus on these measures is a pipe dream.

Even if you overlook disagreements on ESG as growing pains, there is one more component that adds noise to the mix and that is the direction of causality: Do companies perform better because they are socially conscious (good) companies, or do companies that are doing well find it easier to do good? Put simply, if ESG metrics are based upon actions/measures that companies that are doing better, either operationally and/or in markets, can perform/deliver more easily than companies that are doing badly, researchers will find that ESG and performance move together, but it is not ESG that is causing good performance, but good performance which is allowing companies to be socially good.

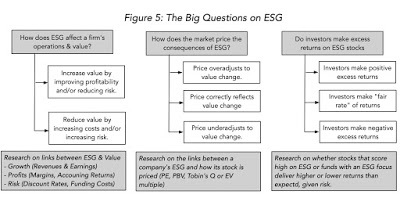

The ESG Sales Pitch - Promises and ContradictionsThe power of the ESG sales pitch has always been that it offers something good to everyone involved, from companies adopting its practices, to investors in those companies, and more broadly, to all of society. For companies, the promise is that being "good" will generate higher profits for the company, at least in the long term, with lower risk, and thus make them more valuable businesses.For investors in these companies, the promise is that investing in "good" companies will generate higher returns than investing in "bad" or middling companies. For society, the promise is that not only will good companies help fight problems directly related to ESG, like climate change and low wages, but also counter more general problems like income inequality and uneven healthcare.Given that ESG has been marketed as all things good, to all people, it is no surprise that its usage has soared, with companies signing on in droves to social compacts, and investors pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into ESG funds and investments. In the process, though, its advocates have either glossed over, or mixed up, three separate questions that need to be answered, on ESG:

The reason it is useful to separate the three questions is that it opens up possibilities that are often missed in both debate and research. For instance, it is possible that ESG does nothing for value, but that it offers a sheen to companies that allows them to be priced more highly than their less socially conscious counterparts and enriches investors, who trade on its basis. Alternatively, it is also possible that ESG does increase value, but that markets adjust quickly to this and that investors do not benefit from investing in ESG stocks. It also illustrates the danger of overreach from ESG research. Much of the research on ESG is compartmentalized, where only one of these questions is addressed, but the researchers seem to use the results to draw conclusions about answers the other two. Thus, a research study that finds that investors make higher returns on companies that rank high on ESG often will go on to posit that this must mean that ESG increases value, a leap that is neither justified nor warranted.

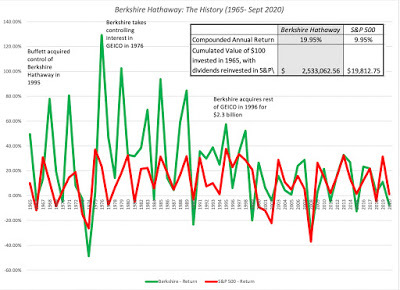

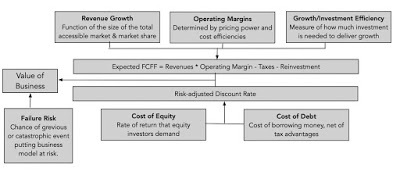

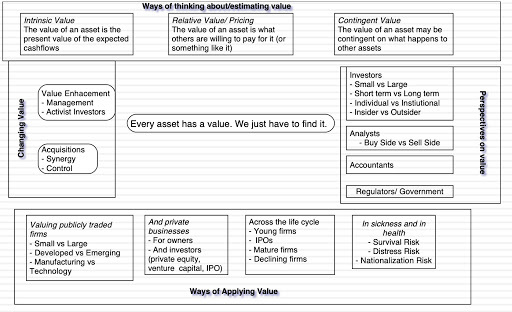

ESG and ValueThe framework for answering the question of whether ESG affects value is no different from the framework for assessing whether acquisitions or financing or any other action affects value. It is both simple and universal, and I have captured the drivers of value for any business in the picture below:

Figure 1: The Drivers of Value

Figure 1: The Drivers of ValueIn fact, my favorite propositions in value is the "It Proposition", which posits that for "it" (investing, financing, dividends, ESG) to affect value, "it" has to affect either the cash flows (through revenue growth, operating margins and investment efficiency) or the risk in those cash flows (which plays out in the cost of equity and capital).

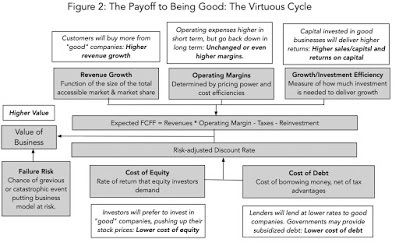

Goodness will be rewardedApplying this proposition to ESG, the most direct way to induce companies to behave in a socially responsible manner is to make it in their financial best interests to do so. There is a plausible scenario, where being good creates a cycle of positive outcomes, which makes the company more valuable. Figure 2 describes this virtuous cycle: