Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 11

March 25, 2021

Interest Rates, Earning Growth and Equity Value: Investment Implications

The first quarter of 2021 has been, for the most part, a good time for equity markets, but there have been surprises. The first has been the steep rise in treasury rates in the last twelve weeks, as investors reassess expected economic growth over the rest of the year and worry about inflation. The second has been a shift within equity markets, a "rotation" in Wall Street terms, as the winners from last year underperformed the losers in the first quarter, raising questions about whether this shift is a long term one or just a short term adjustment. The answers are not academic, since they cut to the heart of how stockholders will do over the rest of the year, and whether value investors will finally be able to mount a comeback.

The Interest Rates Story

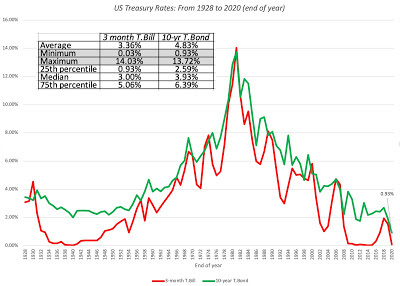

To me the biggest story of markets in 2021 has been the rise of interest rates, especially at the long end of the maturity spectrum. To understand the story and put it in context, I will go back more than a decade to the 2008 crisis, and note how in its aftermath, US treasury rates dropped and stayed low for the next decade.

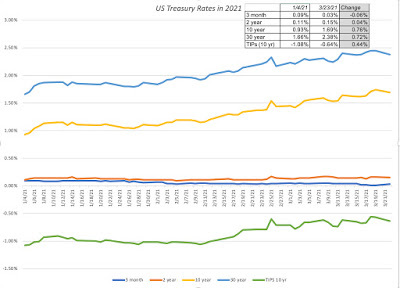

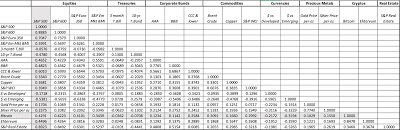

Coming in 2020, the ten-year T.Bond rate at 1.92% was already close to historic lows. The arrival of the COVID in February 2020, and the ensuing market meltdown, causing treasury rates to plummet across the spectrum, with three-month T.bill rates dropping from 1.5% to close to zero, and the ten-year T.Bond rate declining to close to 0.70%. Those rates stayed low through the rest of 2020, even as equity markets recovered and corporate bond spreads fell back to pre-crisis levels. Coming into 2021, the ten-year T.Bond rate was at 0.93%, and I noted the contradiction in investor assessments for the rest of the year, with the consensus gathered around a strong economic comeback (with earnings growth following), but with rates continuing to stay low. In the first quarter of 2021, we continued to see evidence of economic growth, bolstered by a stimulus package of $1.9 trillion, but it does seem like the treasury bond market is starting to wake up to that recognition as well, as rates have risen strongly:

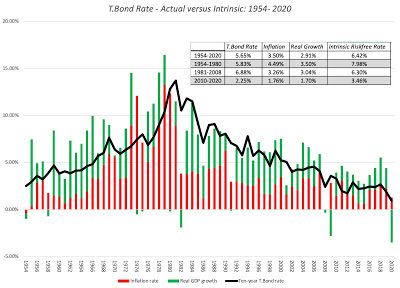

These rising rates have led to some hand wringing about why the Fed is not doing more to keep rates down, mostly from people who seem to have an almost mystical faith in the Fed's capacity to keep rates wherever it wants them to be. I would argue that the Fed has tried everything it can to keep rates from rising, and the very fact that rates have risen, in spite of this effort, is an indication of the limited power it has to set any of the rates that we care about in investing. To those who use the low interest rates of the last decade as proof of the Fed's power, I would counter with a graph that I have used many times before to illustrate the fundamental drivers of interest rates (and the Fed is not on that list):

The reason interest rates have been low for the last decade is because inflation has been low and real growth has been anemic. With its bond buying programs and its "keep rates low" talk, the Fed has had influence, but only at the margin.

As for rates for the rest of the year, you may draw comfort from the Fed's assurances that it will keep rate low, but I don't. Put bluntly, the only rate that the Fed directly sets is the Fed Funds rate, and while it may send signals to the market with its words and actions, it faces two limits.

The first is that the Fed Funds rate is currently close to zero, limiting the Fed's capacity to signal with lower rates. The second and more powerful factor is that the reason that a central bank is able to signal to markets, only if it has credibility, since the signal is more about what the Fed sees, using data that only it might have, about inflation and real growth in the future. Every time a Federal Reserve chair or any of the FOMC members make utterances that undercut that credibility, the Fed risks losing even the limited signaling power it continues to have. I believe that the most effective central bankers speak very little, and when they do, don't say much.In particular, the Fed's own assessments of real growth of 6.5% for 2021 and inflation of 2.2% for the year are at war with its concurrent promise to keep rates low; after all, adding those numbers up yields a intrinsic risk free rate of 8.7%. While I understand that much of the real growth in 2021 is a bounce back from 2020, even using a 2-3% real growth yields risk free rates that are much, much higher than today's numbers.The Stocks Story

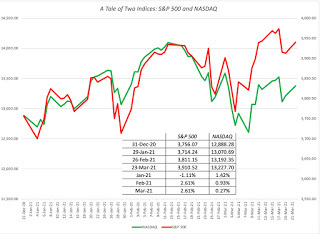

As treasury rates have risen in 2021, equity markets have been surprisingly resilient, with stocks up during the first three months. However, as with last year, the gains have been uneven with some groups of stocks doing better than others, with an interesting twist; the winners of last year seem to be lagging this year, and the losers are doing much better. While some of this reversal is to be expected in any market, there are questions about whether it has anything to do with rising rates, as well as whether there may be light at the end of the tunnel for some investor groups who were left out of the market run-up in the last decade. For much of the last year, I tracked the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ, the first standing in for large cap stocks and the broader market, and the latter proxying for technology and growth stocks, with some very large market companies included in the mix. Continuing that practice, I look at the two indices in 2021:

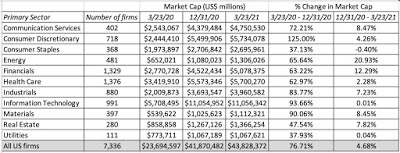

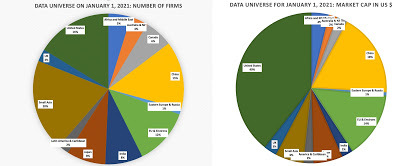

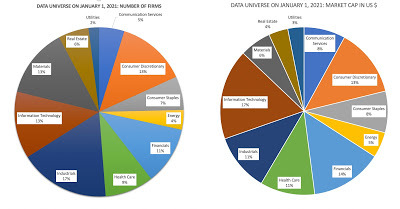

Both indices are up for the year, but they have diverged in their paths. In January, the NASDAQ continued its 2020 success, and the S&P 500 lagged, losing value. In February and March, the tide shifted, and the S&P 500 outperformed the NASDAQ. Looking at the market capitalization of all stocks listed in the United States, and breaking down the market action in 2021, by sector, here is what I see:

Both indices are up for the year, but they have diverged in their paths. In January, the NASDAQ continued its 2020 success, and the S&P 500 lagged, losing value. In February and March, the tide shifted, and the S&P 500 outperformed the NASDAQ. Looking at the market capitalization of all stocks listed in the United States, and breaking down the market action in 2021, by sector, here is what I see:

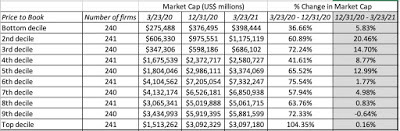

The two sectors where there is the biggest divergence between post-crisis performance in 2020 and market returns in 2021 are energy, which has gone from one of the worse performing sectors to the very best and technology, which has made a journey in the other direction. Using price to book ratios as a rough proxy for value versus growth, I looked at returns in the post-crisis period in 2020 and in 2021, to derive the following table:

The two sectors where there is the biggest divergence between post-crisis performance in 2020 and market returns in 2021 are energy, which has gone from one of the worse performing sectors to the very best and technology, which has made a journey in the other direction. Using price to book ratios as a rough proxy for value versus growth, I looked at returns in the post-crisis period in 2020 and in 2021, to derive the following table:

It is much too early to be drawing strong conclusions, but at least so far in 2021, low price to book stocks, which lagged the market in 2020, are doing much better than higher price to book stocks.

Interest Rates and Value

As interest rates have risen, the discussion in markets has turned ito the effects that these rates will have on stock prices. While the facile answer is that higher rates will cause stock prices to fall, I will argue in this section that not only is the answer more nuanced, and depends, in large part, on why rates are rising in the first place.

Value Framework

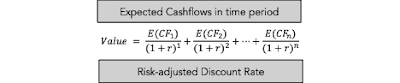

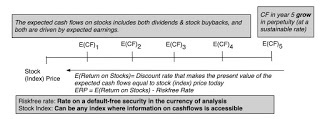

As with any discussion about value and the variables that affect it, I find it useful to go back to basics. If you accept the proposition that the value of a business is a function of its expected cash flows (with both the benefits and costs of growth embedded in them) and the risk in these cash flows, we are in agreement on what drives value, even if we disagree about the specifics on how to measure risk and incorporate it into value:

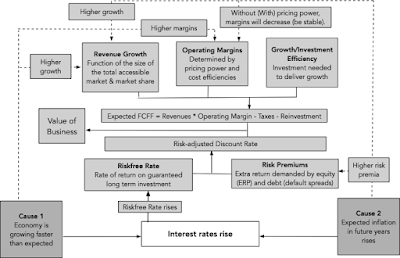

This equation looks abstract, but it has all of the components of a business in it, as you can see in this richer version of the equation:

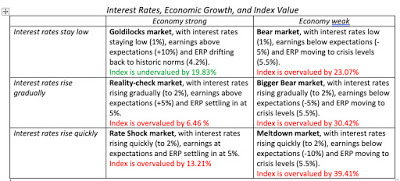

In this richer version, the effect of rising rates can be captured in the components that drive value. The direct effect is obviously through the base rate, i.e. the riskfree rate, on which the discount rate is built, and it is the effect that most analysts latch on to. If you stopped with that effect, rising rates always lead to lower values for equities, since holding all else constant, and raising what you require as a rate of return will translate into lower value today. That misses the indirect effects, and these indirect effects emerge from looking at why rates rose in the first place. Fundamentally, interest rates can rise because investors expectations of inflation go up, or because real economic growth increases, and these macroeconomic fundamentals can affect the other drivers of value: table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Higher real growthHigher inflation Riskfree RateRiskfree rate will rise.Riskfree rate will rise. Risk premiumsNo effect or even a decrease.Risk premia may rise as inflation increases, because higher inflation is almost always more volatile than low inflation. Revenue GrowthIncreases with economic growth, and more so economy-dependent companiesIncreases, as inflation provides a backdraft adding to existing real growth. Operating MarginsIncreases, as increased consumer spending/demand allows for price increasesFor companies with the power to pass through inflation to their customers, stable margins, but for companies without that pricing power, margins decrease. Investment EfficiencyImproves, as the same investment delivers more revenues/profits.No effect, in real terms, but in nominal terms, companies can look more efficient. Value EffectMore likely to be positive. Investors will demand higher rates of return (negative), but higher earnings and cash flows can more than offset effect.More likely to be negative. Investors will demand higher rates of return (negative), and while revenue growth will increase, lower margins will lead to lagging earnings.Put simply, the effect of rising rates on stock prices will depend in large part on the precipitating factors.

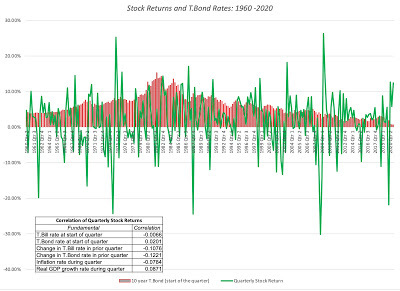

If rising rates are primarily driven by expectations of higher real growth, the effect is more likely to be positive, as higher growth and margins offset the effect of investors demanding higher rates of return on their investments. If rising rates are primarily driven by inflation, the effects are far more likely to be negative, since you have more negative side effects, with risk premiums rising and margins coming under pressure, especially for companies without pricing power. To see how changes in interest rates play out in equity markets, I started with a simple, perhaps even simplistic adjustment, where I look at quarterly stock returns and T.Bond rates at the start of each quarter, to examine the linkage. Download data

Download dataWhile the chart itself has too much noise to draw conclusions, the correlations that I have calculated provide more information. The negative correlation between stock returns and rate changes in the prior quarter (-.12 with the treasury bond rate) provide backing for the conventional wisdom that rising rates are more likely to be accompanied by lower stock returns. However, if you break down the reason for rising rates into higher inflation and higher real growth increases, stocks are negatively affected by the former (correlation of -0.078) and positively affected by the latter (correlation of .087). It is also worth noting that none of the correlations are significant enough to represent money making opportunities, since there seems to be much more driving stock returns than just interest rates, inflation and real growth.

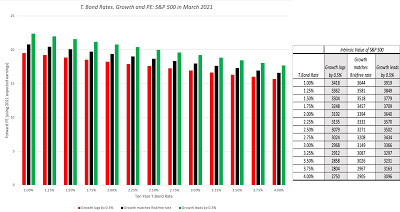

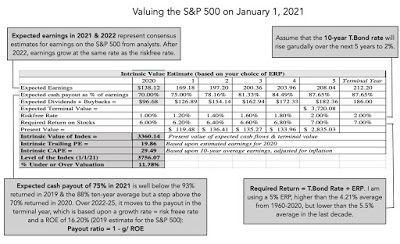

I also updated my valuation (from January 2021) of the S&P to reflect current rates and earnings numbers, and played out the effect of changing rates on the intrinsic PE ratio for the index:

Download spreadsheet

Download spreadsheetIn making these computations, I looked at three scenarios, a neutral scenario, where changes in the T.Bond rate are matched by changes in the expected long term earnings growth rate, a benign scenario, where expected long term earnings growth runs ahead of the change in the T.Bond rate by 0.5%, in the long term, and a malignant scenario, where earnings growth lags changes in the T.Bond rate by 0.5%, in the long term. Note that in the best case scenario, at least with my range of outcomes, where rates drop back to 1.00%, but long term earnings growth runs ahead of riskfree rates by 0.5%, the intrinsic value for the index is 3919, just above current levels. In the worst case scenario, where rates rise to 3% or higher, and growth lags by 0.5%, the index is over valued significantly. Connecting to my earlier discussion of how inflation and real growth play out differently in earnings growth, I would expect a real-growth driven increase in rates to yield values closer to my benign ones, where an inflation-driven increase in rates will be far more damaging for stocks.

Rates and the Corporate Life Cycle

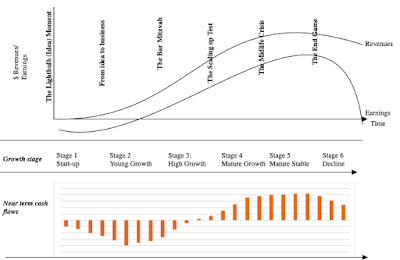

There is a surprisingly complicated relationship between interest rates and stock prices, with higher interest rates sometimes coexisting with higher stock prices and sometimes with lower. As rates rise, though, the effects on value will vary across companies, with some companies being hurt more and others being hurt less, or even helped. To understand why, I will draw on one of my favorite structures, the corporate life cycle, where I argue that most companies go through a process of birth, growth, aging and ultimate decline and death. To see the connection with interest rates, note that there are two dimensions on which companies vary across the life cycle:

Cashflows: Young companies are more likely to have negative than positive cash flows in the early years, as their business models are in flux, economies of scale have not kicked in yet, and substantial reinvestment is needed to deliver the promised growth. As they mature, the cash flows will turn positive, as margins improve and reinvestment needs drop off.

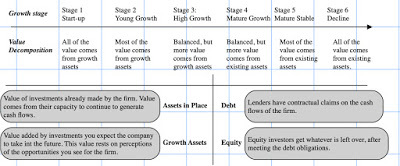

Source of value: Drawing on another construct , the financial balance sheet, the value of a company can be broken down into the value it derives from investments it has already made (assets in place) and the value of investments it is expected to make in the future (growth assets). Young companies derive the bulk of their value from growth assets, whereas more mature firms get their value from assets in place.

Connecting to the earlier discussion on interest rates and value, you can see why increases in interest rates can have divergent effects on companies at different stages in the life cycle. When interest rates rise, the value of future growth decreases, relative to the value of assets in place, for all companies, but the effect is far greater for young companies than mature companies. This will be true even if growth rates match increases in interest rates, but it will get worse if growth does not keep up with rate increases.

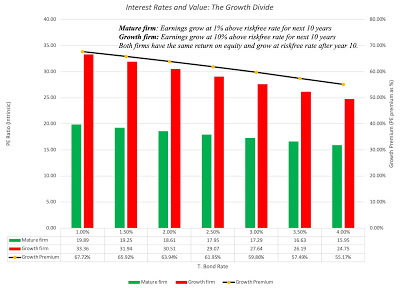

To illustrate this, I will use two firms, similar in asset quality (return on equity = 15%) and risk (cost of equity is 5% above the risk free rate), but different in growth prospects; the mature firm will grow 1% higher than the riskfree rate and the growth firm will grow 10% a year higher than the risk free rate, for the next 10 years. After year 10, both firms will be mature, growing at the risk free rate. As I increase the risk free rate, note that the costs of equity and growth rates will go up for both firms, and that their reinvestment needs will change accordingly. The effects of changing the T.Bond rate in this simplistic example are illustrated below:

Download spreadsheet

Download spreadsheetBoth companies see a decline in PE ratios, as interest rates rise, but the high growth firm sees a bigger drop. This is captured in the growth premium (computed by comparing the PE ratio for the growth firm to the PE ratio for a mature firm). You can check out the effects of introducing malign and benign growth effects into this example, with the former exacerbating the differential effect and the latter reducing it.

The Rest of 2021

I hope that this discussion of the relationship between interest rates and value provides some insight into both why the equity market has been able to maintain its upward trend in the face of rising rates, as well as explain the divergences across growth and mature companies. The primary story driving interest rates, for much of 2021, has been one of economic resurgence, and it does not surprise me that the positives have outweighed the negatives, so far. At the same time, there is concern that inflation might be lurking under the surface, and on days when these worries surface, the market is much more susceptible to melting down. My guess is that this dance will continue for the foreseeable future, but as more real data comes out on both real growth and inflation, one or the other point of view will get vindication. Unlike some in the market, who believe that the Fed has the power to squelch inflation, if it does come back, I am old enough to remember both how stealthy inflation is, as well as how difficult it is for central banks to reassert dominance over inflation, once it emerges as a threat.

YouTube Video

Data links

Treasury Rates; 1928 to 2020Intrinsic versus Actual T.Bond Rate: 1954-2020Stock Returns, Interest Rates, Inflation and Real Growth: 1960-2020Spreadsheets

S&P 500 valuation spreadsheet- March 23, 2021PE calculator for mature and growth companies

February 10, 2021

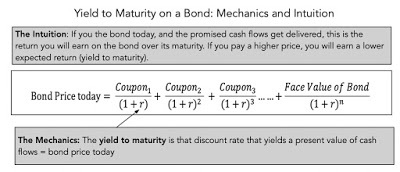

Data Update 4 for 2021: The Hurdle Rate Question!

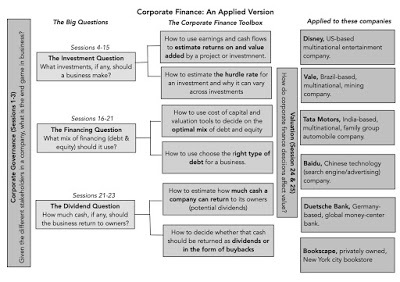

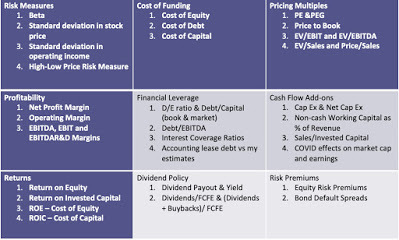

What is a hurdle rate for a business? There are multiple definitions that you will see offered, from it being the cost of raising capital for that business to an opportunity cost, i.e., a return that you can make investing elsewhere, to a required return for investors in that business. In a sense, each of those definitions has an element of truth to it, but used loosely, each of them can also lead you to the wrong destination. In this post, I will start by looking at the role that hurdle rates play in running a business, with the consequences of setting them too high or too low, and then look at the fundamentals that should cause hurdle rates to vary across companies.

What is a hurdle rate?

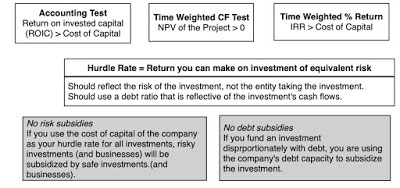

Every business, small or large, public or private, faces a challenge of how to allocate capital across competing needs (projects, investments and acquisitions), though some businesses have more opportunities or face more severe constraints than others. In making these allocation or investment decisions, businesses have to make judgments on the minimum return that they would accept on an investment, given its risk, and that minimum return is referenced as the hurdle rate. Having said that, though, it is worth noting that this is where the consensus ends, since there are deep divides on how this hurdle rate should be computed, with companies diverging and following three broad paths to get that number:

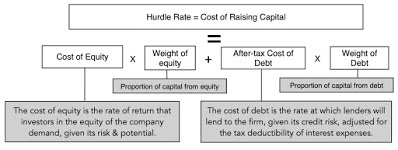

1. Cost of raising funds (capital): Since the funds that are invested by a business come from equity investors and lenders, one way in which the hurdle rate is computed is by looking at how much it costs the investing company to raise those funds. Without any loss of generality, if we define the rate of return that investors demand for investing in equity as the cost of equity and the rate that lenders charge for lending you money as the cost of debt, the weighted average of these two costs, with the weights representing how much of each source you use, is the cost of capital:

The problem with a corporate cost of capital as a hurdle rate is that it presumes that every project the company takes has the same overall risk profile as the company. That may make sense if you are a retailer, and every investment you make is another mall store, but it clearly does not, if you are a company in multiple businesses (or geographies) and some investments are much riskier than others.

2. Opportunity Cost: The use of a corporate cost of capital as a hurdle rate exposes you to risk shifting, where safe projects subsidize risky projects, and one simple and effective fix is to shift the focus away from how much it costs a company to raise money to the risk of the project or investment under consideration. The notion of opportunity cost makes sense only if it is conditioned on risk, and the opportunity cost of investing in a project should be the rate of return you could earn on an alternative investment of equivalent risk.

If you follow this practice, you are replacing a corporate cost of capital with a project-specific hurdle rate, that reflects the risk of that project. It is more work than having one corporate hurdle rate, but you are replacing a bludgeon with a scalpel, and the more varied your projects, in terms of business and geography, the greater the payoff.

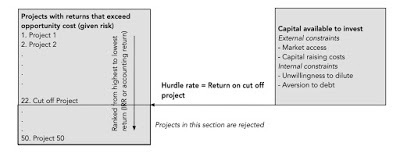

3. Capital Constrained Clearing Rate: The notion that any investment that earns more than what other investments of equivalent risk are delivering is a good one, but it is built on the presumption that businesses have the capital to take all good investments. Many companies face capital constraints, some external (lack of access to capital markets) and some internal (a refusal to issue new equity because of dilution concerns), and consequently cannot follow this rule. Instead, they find a hurdle rate that incorporates their capital constraints, yielding a hurdle rate much higher than the true opportunity cost. To illustrate, assume that you are a company with fifty projects, all of similar risk, and all earning more than the 10% that investments of equivalent risk are making in the market. If you faced no capital constraints, you would take all fifty, but assume that you have limited capital, and that you rank these projects from highest to lowest returns (IRR or accounting return). The logical thing to do is to work down the list, accepting projects with the highest returns first until you run out of capital. If the last project that you end up accepting has a 20% rate of return, you set your hurdle rate as 20%, a number that clears your capital.

By itself, this practice make sense, but inertia is one of the strongest forces in business, and that 20% hurdle rate often become embedded in practice, even as the company grows and capital constraints disappear. The consequences are both predictable and damaging, since projects making less than 20% are being turned away, even as cash builds up in these companies.

While the three approaches look divergent and you may expect them to yield different answers, they are tied together more than you realize, at least in steady state. Specifically, if market prices reflect fair value, the cost of raising funds for a company will reflect the weighted average of the opportunity costs of the investments they make as a company, and a combination of scaling up (reducing capital constraints) and increased competition (reducing returns on investments) will push the capital constrained clearing rate towards the other two measures. If you are willing to be bored, I do have a paper on cost of capital that explains how the different definitions play out, as well as the details of estimating each one.

Hurdle Rate - The Drivers

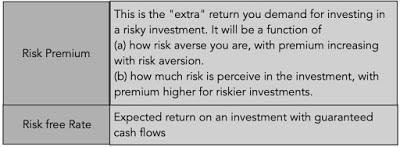

For the rest of this post, I will adopt the opportunity cost version of hurdle rates, where you are trying to measure how much you should demand on a project or investment, given its risks. In this section, I will point to the three key determinants of whether the hurdle rate on your next project should be 5% or 15%. The first is the business that the investment is in, and the risk profile of that business. The second is geography, with hurdle rates being higher for projects in some parts of the world, than others. The third is currency, with hurdle rates, for any given project, varying across currencies.

A. Business

If you are a company with two business lines, one with predictable revenues and stable profit margins, and the other with cyclical revenues and volatile margins, you would expect to, other things remaining equal, use a lower hurdle rate for the first than the second. That said, there are two tricky components of business risk that you need to navigate:

Firm specific versus Macro risk: When you invest in a company, be it GameStop or Apple, there are two types of risks that you are exposed to, risks that are specific to the company (that GameStop's online sales will be undercut by competition or that Apple's next iPhone launch may not go well) and risks that are macroeconomic and market-wide (that the economy may not come back strongly from the shut down or that inflation will flare up). If you put all your money in one or the other of these companies, you are exposed to all these risks, but if you spread your bets across a dozen or more companies, you will find that company-specific risk gets averaged out. From a hurdle rate perspective, this implies that companies, where the marginal investors (who own a lot of stock and trade that stock) are diversified, should incorporate only macroeconomic or market risk into hurdle rates. For small private firms, where the sole owner is not diversified, the hurdle rate will have to incorporate and be higher.Financial leverage: There are two ways you can raise funding for a company, and since lenders have contractual claims on the cash flows, the cost of debt should be lower than the cost of equity for almost every company, and that difference is increased by the tax laws tilt towards debt (with interest expenses being tax deductible). Unfortunately, there are many who take this reality and jump to the conclusion that adding debt will lower your hurdle rate, an argument that is built on false premises and lazy calculations. In truth, debt can lower the hurdle rate for some companies, but almost entirely because of the tax subsidy feature, not because it is cheaper, but it can just as easily increase the hurdle rate for others, as distress risk outweighs the tax benefits. (More on that issue in a future data update post...)I know that many of you are not fans of modern portfolio theory or betas, but ultimately, there is no way around the requirement that you need to measure how risky a business, relative to other businesses. I am a pragmatist when it comes to betas, viewing them as relative risk measures that work reasonably well for diversified investors, but I have also been open about the fact that I will take an alternate measure of risk that accomplishes the same objective.

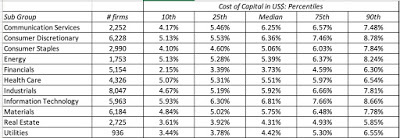

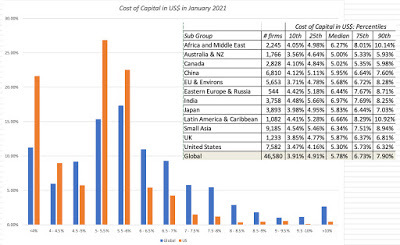

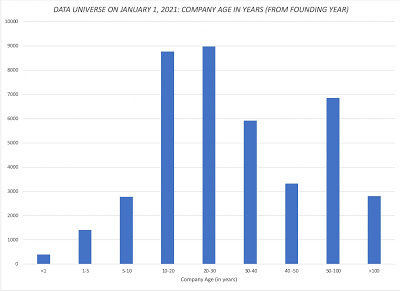

To illustrate how costs of capital can vary across businesses, I used a very broad classification of global companies into sectors, and computed the cost of capital at the start of 2021, in US $ terms, for each one:

If you prefer a more granular breakdown, I estimate costs of capital by industry (with 95 industry groupings) in US $ and you can find the links here. (US, Europe, Emerging Markets, Japan, Australia/NZ & Canada, Global)

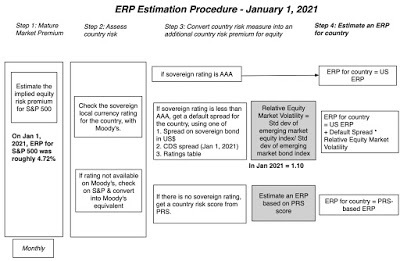

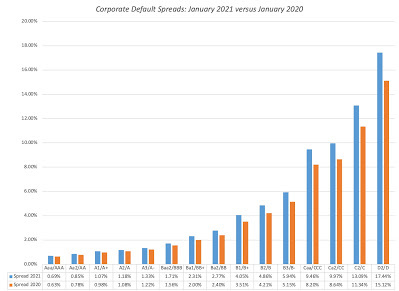

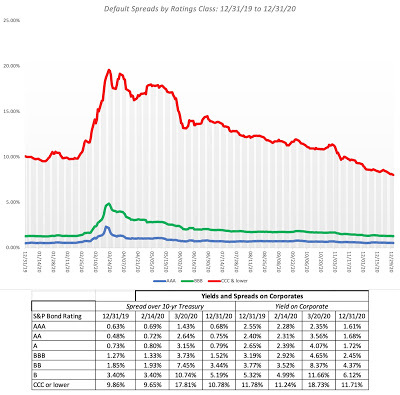

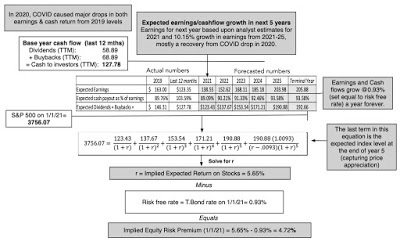

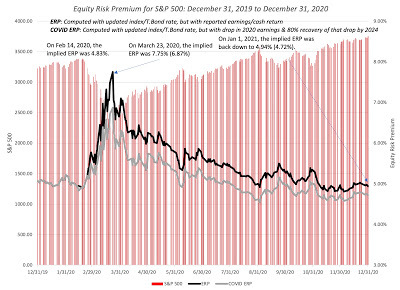

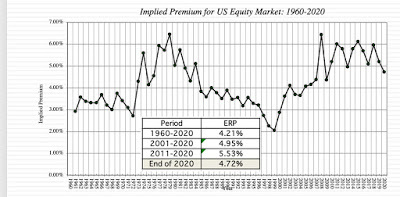

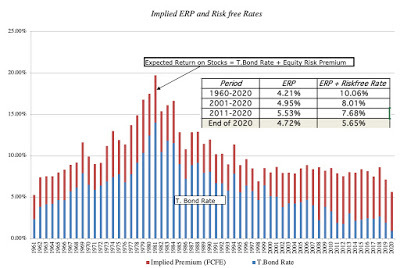

2. Geography

As a business, should you demand a higher US $ hurdle rate for investing in a project in Nigeria than the US $ hurdle rate you would require for an otherwise similar project in Germany? The answer, to me, seems to be obviously yes, though there are still some who argue otherwise, usually with the argument that country risk can be diversified away. The vehicle that I use to convey country risk into hurdle rates is the equity risk premium, the price of risk in equity markets, that I talked about in my earlier post on the topic. In that post, I computed the equity risk premium for the S&P 500 at the start of 2021 to be 4.72%, using a forward-looking, dynamic measure. If you accept that estimate, a company looking at a project in the US or a geographical market similar to the US in terms of country risk, would accept projects that delivered this risk premium to equity investors.

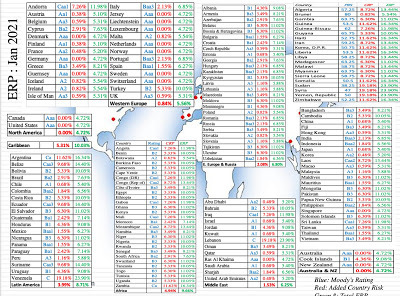

But what if the company is looking at a project in Nigeria or Bangladesh? To answer that question, I estimate equity risk premiums for almost every country in the world, using a very simple (or simplistic) approach. I start with the 4.72%, my estimate of the US ERP, as my base premium for mature equity markets, treating all Aaa rated countries (Germany, Australia, Singapore etc.) as mature markets. For countries not rated Aaa, I use the sovereign rating for the country to estimate a default spread for that country, and scale up that default spread for the higher risk that equities bring in, relative to government bonds.

That additional premium, which I call a country risk premium, when added to the US ERP, gives me an equity risk premium for the country in question.

Download country ERPs

Download country ERPsWhat does this mean? Going back to the start of this section, a company (say Ford) would require a higher cost of equity for a Nigerian project than for an equivalent German project (using a US $ risk free rate of 1% and a beta of 1.1 for Ford).

Cost of equity in US $ for German project = 1% + 1.1 (4.72%) = 6.19%Cost of equity in US $ for a Nigerian project = 1% + 1.1 (10.05%) = 12.06%The additional 5.87% that Ford is demanding on its Nigerian investment reflects the additional risk that the country brings to the mix.3. Currency

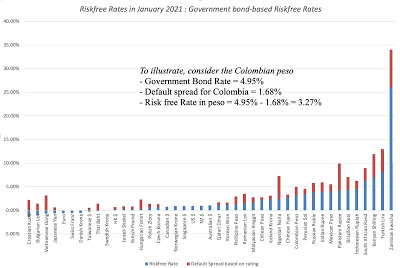

I have studiously avoided dealing with currencies so far, by denominating all of my illustrations in US dollars, but that may strike some of you as avoidance. After all, the currency in Nigeria is the Naira and in Germany is the Euro, and you may wonder how currencies play out in hurdle rates. My answer is that currencies are a scaling variable, and dealing with them is simple if you remember that the primary reason why hurdle rates vary across currencies is because they bring different inflation expectations into the process, with higher-inflation currencies commanding higher hurdle rates. To illustrate, if you assume that inflation in the US $ is 1% and that inflation in the Nigerian Naira is 8%, the hurdle rate that we computed for the Nigerian project in the last section can be calculated as follows:

Cost of equity in Naira for Nigerian project (approximate) = 12.06% + (8% - 1%) = 19.06%Cost of equity in Naira for Nigerian project (precise) = 1.1206 * (1.08/1.01) -1 = 19.83%In effect, the Nigerian Naira hurdle rate will be higher by 7% (7.77%) roughly (precisely) than a US $ hurdle rate, and that difference is entirely attributable to inflation differentials. The instrument that best delivers measures of the expected inflation is the riskfree rate in a currency, which I compute by starting with a government bond rate in that currency and then cleaning up for default risk. At the start of 2021, the riskfree rates in different currencies are shown below:

Download government-bond based riskfree rates

Download government-bond based riskfree ratesThese risk free rates are derived from government bond rates, and to the extent that some of the government bonds that I looked at are not liquid or widely traded, you may decide to replace those rates with synthetic versions, where you add the differential inflation to the US dollar risk free rate. Also, note that there are quite a few currencies with negative risk free rates, a phenomenon that can be unsettling, but one you can work with, as long as you stay consistent.

Implications

As we reach the end of this discussion, thankfully for all our sakes, let's look at the implications of what the numbers at the end of 2020 are for investors are companies.

Get currency nailed down: We all have our frames of reference, based often upon where we work, and not surprisingly, when we talk with others, we expect them to share the same frames of reference. When it comes to hurdle rates, that can be dangerous, since hurdle rates will vary across currencies, and cross-currency comparisons are useless. Thus, a 6% hurdle rate in Euros may look lower than a 12% hurdle rate in Turkish lira, but after inflation is considered, the latter may be the lower value. Any talk of a global risk free rate is nonsensical, since risk free rates go with currencies, and currencies matter only because they convey inflation. That is why you always have the option of completely removing inflation from your analysis, and do it in real terms.A low hurdle rate world: At the start of 2021, you are looking at hurdle rates that are lower than they have ever been in history, for most currencies. In the US dollar, for instance, a combination of historically low risk free rates and compressed equity risk premiums have brought down costs of capital across the board, and you can see that in the histogram of costs of capital in US $ of US and global companies at the start of 2021:

The median cost of capital in US $ for a US company is 5.30%, and for a global company is 5.78%, and those numbers will become even lower if you compute them in Euros, Yen or Francs. I know that if you are an analyst, those numbers look low to you, and the older you are, the lower they will look, telling you something about how your framing of what you define to be normal is a function of what you used to see in practice, when you were learning your craft. That said, unless you want to convert every company valuation into a judgment call on markets, you have to get used to working with these lower discount rates, while adjusting your inputs for growth and cash flows to reflect the conditions that are causing those low discount rates. For companies and investors who live in the past, this is bad news. A company that uses a 15% cost of capital, because that is what it has always used, will have a hard time finding any investments that make the cut, and investors who posit that they will never invest in stocks unless they get double digit returns will find themselves holding almost mostly-cash portfolios. While both may still want to build a buffer to allow for rising interest rates or risk premiums, that buffer is still on top of a really low hurdle rate and getting to 10% or 15% is close to impossible.Don't sweat the small stuff: I spend a lot of my time talking about and doing intrinsic valuations, and for those of you who use discounted cash flow valuations to arrive at intrinsic value, it is true that discount rates are an integral part of a DCF. That said, I believe that we spend way too much time on discount rates, finessing risk measures and risk premiums, and too little time on cash flows. In fact, if you are in a hurry to value a company in US dollars, my suggestion is that you just use a cost of capital based upon the distribution in the graph above (4.16% for a safe company, 5.30% for an average risk company or 5.73% for a risky company) as your discount rate, spend your time estimating revenue growth, margins and reinvestment, and if you do have the time, come back and tweak the discount rate.

I know that some of you have been convinced about the centrality of discount rates by sensitivity analyses that show value changing dramatically as discount rates changes. These results are almost the consequence of changing discount rates, while leaving all else unchanged, an impossible trick to pull off in the real world. Put simply, if you woke up tomorrow in a world where the risk free rate was 4% and the cost of capital was 8% for the median company, do you really believe that the earnings and cash flows you projected in a COVID world will remain magically unchanged? I don't!

YouTube Video

Spreadsheets

Cost of capital, by industry - January 2021 (US, Europe, Emerging Markets, Japan, Australia/NZ & Canada, Global)Equity Risk Premiums, by Country - January 2021 Risk free rates by currency - January 2021February 3, 2021

The Price-Value Feedback Loop: A Look at GME and AMC!

There are three topics that you can write or talk about that are almost guaranteed to draw a audience, stocks (because greed drives us all), sex (no reason needed) and salvation. I am not an expert on the latter two, and I am not sure that I have that much that is original to say about the first. That said, in my niche, which is valuation, many start with the presumption that almost every topic you pick is boring. Obviously, I do not believe that, but there are some topics in valuation that are tough to care about, unless they are connected to real events or current news. One issue that I have always wanted to write about is the potential for a feedback loop between price and value (I can see you already rolling your eyes, and getting ready to move on..), but with the frenzy around GameStop and AMC, you may find it interesting. Specifically, a key question that many investors, traders and interested observers have been asking is whether a company, whose stock price and business is beleaguered, can take advantage of a soaring stock price to not just pull itself out of trouble, but make itself a more valuable firm. In other words, can there be a feedback loop, where increasing stock prices can pull value up, and conversely, could decreasing prices push value down?

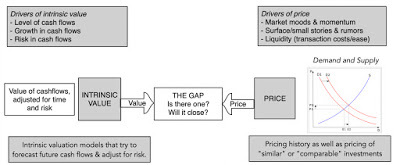

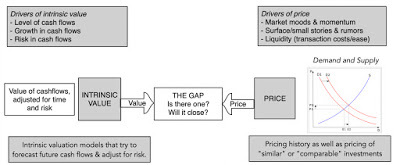

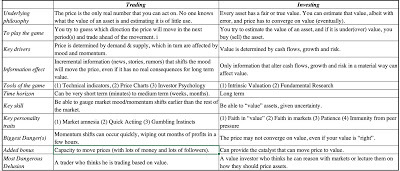

Price, Value and the Gap

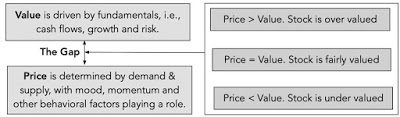

For the third time in three posts, I am going to fall back on my divide between value and price. Value, as I have argued is a function of cash flows, growth and risk, reflecting the quality of a company's business model. Price is determined by demand and supply, where, in addition to, or perhaps even overwhelming, fundamentals, you have mood, momentum and revenge (at least in the case of GameStop) thrown into the mix. Since the two processes are driven by different forces, there is no guarantee that the two will yield the same number for an investment or a company at a point in time:

Put simply, you can have the price be greater than value (over valued), less than value (under valued) or roughly the same (fairly valued). The last scenario is the one where markets are reasonably efficient, and in that scenario, the two processes do not leak into each other. In terms of specifics, when a stock's value is roughly equal to its price:

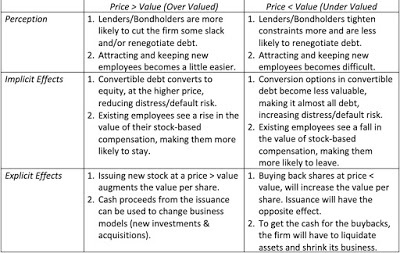

Issuing new shares at the market price will have no effect on the value per share or the price per share, dilution bogeyman notwithstanding.Buying back shares at the market price will have no effect on the value per share or price per share of the remaining shares, even though the earnings per share may increase as a result of decreased share count.I know these implications sound unbelievable, especially since we have been told over and over that these actions have consequences for investors, and so much analysis is built around assessments of accretion and dilution, with the former being viewed as an unalloyed good and latter as bad.The Feedback LoopIn the real world, there are very few people who believe in absolute market efficiency, with even the strongest proponents of the idea accepting the fact that price can deviate from value for some or many companies. When this happens, and there is a gap between price and value, there is the potential for a feedback loop, where a company's pricing can affects its value. That loop can be either a virtuous one (where strong pricing for a company can push up its value) or a vicious one (where weak pricing for a company can push down value). There are three levels at which a gap between value and price can feed back into value:Perception: While nothing fundamentally has changed in the company, a rise (fall) in its stock price, makes bondholders/lenders more willing to slacken (tighten) constraints on the firm and increase (decrease) the chances of debt being renegotiated. It also affects the company's capacity to attract or repel new employees, with higher stock prices making a company a more attractive destination (especially with stock-based compensation thrown into the mix) and lower stock prices having the opposite effect.Implicit effects: When a company's stock price goes up or down, there can be tangible changes to the company's fundamentals. If a company has a significant amount of debt that is weighing it down, creating distress risk, and some of it is convertible, a surge in the stock price can result in debt being converted to equity on favorable terms (fewer shares being issued in return) and reduce default risk. Conversely, if the stock price drops, the conversion option in convertible debt will melt away, making it almost all debt, and pushing up debt as a percent of value. A surge or drop in stock prices can also affect a company's capacity to retain existing employees, especially when those employees have received large portions of their compensation in equity (options or restricted stock) in prior years. If stock prices rise (fall), both options and restricted stock will gain (lose) in value, and these employees are more (less) likely to stay on to collect on the proceeds. Explicit effects: If a company's stock price rises well above value, companies will be drawn to issue new shares at that price. While I will point out some of the limits of this strategy below, the logic is simple. Issuing shares at the higher price will bring in cash into the company and it will augment overall value per share, even though that augmentation is coming purely from the increase in cash. Companies can use the cash proceeds to pay down debt (reducing the distress likelihood) or even to change their business models, investing in new models or acquiring them. If a company's stock price falls below value, a different set of incentives kick in. If that company buys back shares at that stock price, the value per share of the remaining shares will increase. To do this, though, the company will need cash, which may require divestitures and shrinking the business model, not a bad outcome if the business has become a bad one.I have summarized all of these effects in the table below:

These effects will play out in different inputs into valuation, with the reduction in distress risk showing up in lower costs for debt and failure probabilities, the capacity to hire new and keep existing employees in higher operating margin, the issuance or buyback of shares in cash balances and changes in the parameters of the business model (growth, profitability). Looking at the explicit effect of being able to issue shares in the over valued company or buy back shares in the under valued one, there are limits that constrain their use:Regulations and legal restrictions: A share issuance by a company that is already public is a secondary offering, and while it is less involved than a primary offering (IPO), there are still regulatory requirements that take time and require SEC approval. Specifically, a company planning a secondary offering has to file a prospectus (S-3), listing out risks that the company faces, how many shares it plans to issue and what it plans to use the proceeds for. That process is not as time consuming or as arduous as it used to be, but it is not instantaneous; put simply, a company that sees its stock price go up 10-fold in a day won't be able to issue shares the next day.Demand, supply and momentum: If the price is set by demand and supply, increasing the supply of shares will cause price to drop, but the effect is much more insidious. To the extent that the demand for an over valued stock is driven by mood and momentum, the very act of issuing shares can alter momentum, magnifying the downward pressure on stock prices. Put simply, a company that sees it stock price quadruple that then rushes a stock issuance to the market may find that the act of issuing the shares, unless pre-planned, May itself cause the price rise to unravel.Value transfer, not value creation: Even if you get past the regulatory and demand/supply obstacles, and are able to issue the shares at the high price, it is important that you not operate under the delusion that you have created value in that stock issuance. The increase in value per share that you get comes from a value transfer, from the shareholders who buy the newly issued shares at too high a price to the existing shareholders in the company.Cash and trust: If you can live with the value transfer, there is one final hurdle. The new stock issuance will leave the company with a substantial cash balance, and if the company's business model is broken, there is a very real danger that managers, rather than follow finding productive ways to fix the model, will waste the cash trying to reinvent themselves.With buybacks, the benefits of buying shares back at below value are much touted, and Warren Buffett made this precept an explicit part of the Berkshire Hathaway buyback program, but buybacks face their own constraints. A large buyback may require a tender offer, with all of the costs and restrictions that come with them, the act of buying back stock may push the price up and beyond value. The value transfer in buybacks, if they occur at below fair value, also benefit existing shareholders, but the losers will be those shareholders who sold their shares back. Finally, a buyback funded with cash that a company could have used on productive investment opportunities is lost value for the company.

Reality Check

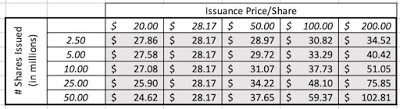

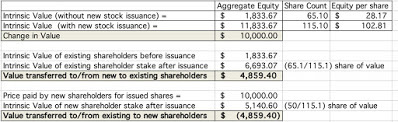

With that long lead in, we can address the question that many of those most upbeat about GameStop and AMC were asking last week. Can the largely successful effort, at least so far, in pushing up stock prices actually make GameStop or AMC a more valuable company? The answer is nuanced and it depends on the company:Perception: For the moment, the rise in the stock price has bought breathing room in both companies, as lenders back off, but that effect is likely to be transient. Perception alone cannot drive up value.Implicit effects: On this dimension, AMC has already derived tangible benefits, as $600 million in convertible debt will become equity, making the company far less distressed. For those Redditors primed for revenge against Wall Street, it is worth noting that the biggest beneficiary in this conversion is Silver Lake, a hedge fund that invested in these bonds in the dark days for the company. GameStop's debt is more conventional borrowing, and while bond prices have gone up, the benefits don't accrue as directly to the company.Explicit effects: On this dimension again, AMC is better positioned, having already filed a prospectus for a secondary offering on December 11, well ahead of the stock run-up. In that offering, AMC filed for approval for issuance of up to 178 million additional shares, from time to time, primarily to pay down debt. If the stock price stays elevated, and that is a big if, AMC will be able to issue shares at a price > value and increase its value per share. It is unclear whether GameStop has the time to even try to do this, especially if the stock price rise dissipates in days or weeks, rather than months.To incorporate the feedback loop, I had modified my base case GameStop valuation (not the best case that you saw in my last post), and allowed for two additional inputs: new shares issued and an issuance price. Note that the value per share that I get with no additional shares issued is $28.17, and you can see how that value per share changes, for different combinations of issuance share numbers and issuance share prices:

Note that if the issuance occurs at my estimate of intrinsic value of $28.17, the share issuance has no effect on value per share, since the increase in share count offsets the increased cash balance exactly. Even in the more upbeat scenarios, where the company is able to issue new shares at a price above this value, let's be clear that the game that is playing out is value transfer. To see this, take the most extreme scenario, where GameStop is able to issue 50 million new shares (increasing their share count from 65.1 million to 115.1 million) at a stock price of $200, viable perhaps on Friday (when the stock traded about $300) but not today, the value effect and transfer can be seen below:

The value transfer can be intuitively explained. If new shareholders pay well above value, that increment accrues to existing shareholders. Since the new shareholders are buying the shares voluntarily, you may be at peace with this transfer, but if these new shareholders are small individual investors drawn in by the frenzy, the entire notion of this price run-up being a blow for fairness and justice is undercut. Investing Endgames!The anger and sense of unfairness that animated many of those who were on the buying end of GameStop and AMC last week has roots in real greviances, especially among those who came of age in the midst or after the 2008 crisis. I understand that, but investing with the intent of hurting another group, no matter how merited you think that punishment is, has two problems. The first is that markets are fluid, with the winners and losers from an investing episode representing a quickly shifting coalition, The people who are helped and hurt are not always the people that you set out to help or hurt. The second is that if you truly want to punish a group that you think is deserving of punishment, you have to find a way to do damage to their investment models. Hurting some hedge funds, say the short sellers in GameStop, while helping others, like Silver Lake, will only cause investors in these funds to move their money from losing funds to winning funds. Thus, the best revenge you can have on funds is to see investors collectively pull their money out of funds, and that will happen if they under perform as a group.

YouTube Video

SpreadsheetValuation of GameStop (with Feedback loop for stock issues)Blog Posts on GameStopThe Storming of the Bastille: The Redditor Crowd traders the Hedge Funds!

January 29, 2021

The Storming of the Bastille: The Reddit Crowd targets the Hedge Funds!

I generally try to stay out of fights, especially when they become mud-wrestling contests, but the battle between the hedge funds and Reddit investors just too juicy to ignore. As you undoubtedly know, the last few days have been filled with news stories of how small investors, brought together on online forums, have not only pushed up the stock prices of the stocks that they have targeted (GameStop, AMC, BB etc.), but in the process, driven some of the hedge funds that have sold short on these companies to edge of oblivion. The story resonates because it has all of the elements of a David versus Goliath battle, and given the low esteem that many hold Wall Street in, it has led to sideline cheerleading. Of course, as with everything in life, this story has also acquired political undertones, as populists on all sides, have found a new cause. I don't have an axe to grind in this fight, since I don't own GameStop or care much about hedge funds, but I am interested in how this episode will affect overall markets and whether I need to change the ways in which I invest and trade.

Short Sales and Squeezes

I know that you want to get to the GameStop story quickly, but at the risk of boring or perhaps even insulting you, I want to lay the groundwork by talking about the mechanics of a short sale as well as how short sellers can sometimes get squeezed. When most of look at investing, we think of stocks that we believe (based upon research, instinct or innuendo) will go up in value and buying those stocks; in investing parlance, if you do this, you have a "long" position. For those of you tempted to put all of Wall Street into one basket, it is worth noting that the biggest segment of professional money management still remains the mutual fund business, and mutual funds are almost all restricted to long only positions. But what if you think a stock is too highly priced and is likely to go down? If you already own the stock, you can sell it, but if you don't have a position in the stock and want to monetize your pessimistic point of view, you can borrow shares in the stock and sell them, with an obligation to return the shares at a specified point in time in the future. This is a “short” sale, and if you are right and the stock price drops, you can buy the shares at the now "discounted" price, return them to the original owner and keep the difference as your profit.

Short sellers have never been popular in markets, and that dislike is widely spread, not just among small investors, but also among corporate CEOs, and many institutional investors. In fact, this dislike shows up not only in restrictions on short selling in some markets, but outright bans in others, especially during periods of turmoil. I don't believe that there is anything inherently immoral about being a pessimist on markets, and that short selling serves a purpose in well-functioning markets, as a counter balance to relentless and sometimes baseless optimism. In fact, mathematically, all that you do in a short sale, relative to a conventional investment, is reverse the sequence of your actions, selling first and buying back later.

It is true that short sellers face a problem that their long counterparts generally do not, and that is they have far less control over their time horizons. While you may be able to sell short on a very liquid, widely traded stock for a longer period, on most stocks, your short sale comes with a clock that is ticking from the moment you initiate your short sale. Consequently, short sellers often try to speed the process along, going public with their reasons for why the stock is destined to fall, and they sometimes step over the line, orchestrating concerted attempts to create panic selling. While short sellers wait for the correction, they face multiple threats, some coming from shifts in fundamentals (the company reporting better earnings than expected or getting a cash infusion) and some from investors with a contrary view on the stock, buying the stock and pushing the stock price up. Since short sellers have potentially unlimited losses, these stock price increases may force them to buy back shares in the market to cover their short position, in the process pushing prices up even more. In a short squeeze, this cycle speeds up to the point that short sellers have no choice but to exit the position.

Short squeezes have a long history on Wall Street. In 1862, Cornelius Vanderbilt squeezed out short sellers in Harlem Railroad, and used his power to gain full control of the New York railroad business. During the 20th century, short sales ebbed and flowed over the decades, but lest you fall into the trap of believing that this is a purely US phenomenon, the short sale with the largest dollar consequences was the one on Volkswagen in 2008, when Porsche bought enough shares in Volkswagen to squeeze short sellers in the stock, and briefly made Volkswagen the highest market cap company in the world. Until this decade, though, most short squeezes were initiated and carried through by large investors on the other side of short sellers, with enough resources to force capitulation. In the last ten years, the game has changed, for a number of reasons that I will talk about later in this post, but the company where this changed dynamic has played out most effectively has been Tesla. In the last decade, Tesla has been at the center of a tussle between two polarized groups, one that believes that the stock is a scam and worth nothing, and the other that is convinced that this is the next multi-trillion dollar company. Those divergent viewpoints have led to the former to sell short on the stock, making Tesla one of the most widely shorted stocks of all time, and the latter buying on dips. There have been at least three and perhaps as many as five short squeezes on Tesla, with the most recent one occurring at the start of 2020. With Tesla, individual investors who adore the company have been at the front lines in squeezing short sellers, but they have had help from institutional investors who are also either true believers in the company, or are too greedy not to jump on the bandwagon.

The Story (so far)

This story is still evolving, but the best way to see it is to pick one company, GameStop, and see how it became the center of a feeding frenzy. Note that much of what I say about GameStop could be said about AMC and BB, two other companies targeted in the most recent frenzy.

A Brief History

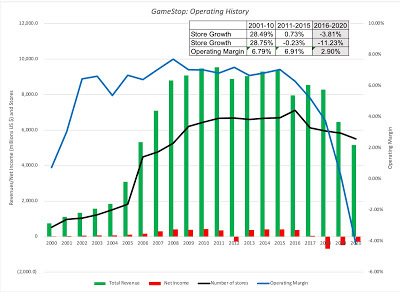

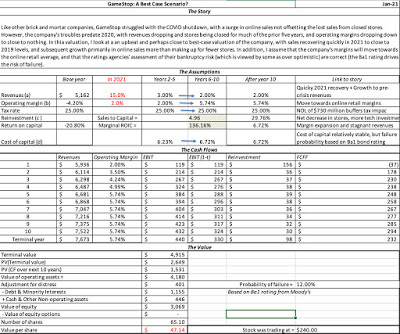

GameStop is a familiar presence in many malls in the United States, selling computer gaming equipment and games, and it built a business model around the growth of the gaming business. That business model ran into a wall a few years ago, as online retailing and gaming pulled its mostly young customers away, causing growth to stagnate and margins to drop, as you can see in this graph of the company’s operating history:

Leading into 2020, the company was already facing headwinds, with declining store count and revenues, and lower operating margins; the company reported net losses in 2018 and 2019.

The COVID Effect

In 2020, the company, like most other brick and mortar companies, faced an existential crisis. As the shutdown put their stores out of business, the debt and lease payments that are par for the course for any brick-and-mortar retailer threatened to push them into financial distress. The stock prices for the company reflected those fears, as you can see in this graph (showing prices from 2015 through the start of 2021):

Looking at the graph, you can see that if GameStop is a train wreck, it is one in slow motion, as stock prices have slid every year since 2015, with the added pain of rumored bankruptcy in 2019 and 2020.

A Ripe Target and the Push Back

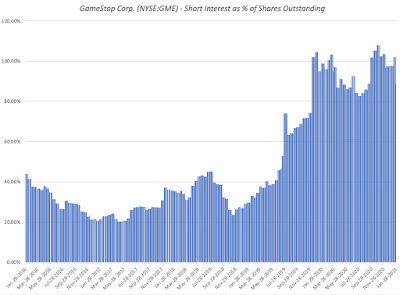

While mutual funds are often constrained to be hold only long positions, hedge funds have the capacity to play both sides of the game, though some are more active on the short side than others. While short sellers target over priced firms, adding distress to the mix sweetens the pot, since drops in stock prices can put them into death spirals. The possibility of distress at GameStop loomed large enough that hedge funds entered the fray, as can be seen in the rising percentage of shares held by short sellers in 2020:

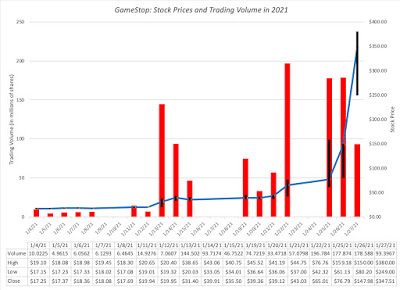

Note that short seller interest in GameStop first picked up in 2019, and then steadily built up in 2020. Even prior to the Reddit buy in, there were clearly buyers who felt strongly enough to to push back against the short sellers, since stock prices posted a healthy increase in the last few months of 2019. To show you how quickly this game has shifted, Andrew Left, one of the short sellers, put out a thesis on January 21, where he argued that GameStop was in terminal decline, and going to zero. While his intent may have been to counter what many believed was a short squeeze on the stock in the prior two days, it backfired by drawing attention to the squeeze and drawing in more buyers. That effect can be seen in the stock price movements and trading volume in the last few days:

This surge in stock prices was catastrophic for short sellers, many of whom closed out (or tried to close out) their short positions, in the process pushing up prices even more. Melvin Capital and Citron, two of the highest profile names on the short selling list, both claimed to have fully exited their positions in the last few days, albeit with huge losses. On January 27 and 28, regulators and trading platforms acted to curb trading on GameStop, ostensibly to bring stability back to markets, but traders were convinced that the establishment was changing the rules of the game to keep them from winning. GameStop, which had traded briefly at over $500/share was trading at about $240 at the time this post was written.

A Value Play?

When you have a pure trading play, as GameStop has become over the last few weeks, value does not even come into play, but there are investors, who pre-date the Redditors, who took counter positions against the short sellers, because they believed that the value of the company was higher. At the risk of ridicule, I will value the company, assuming the most upbeat story that I can think of, at least at the moment:

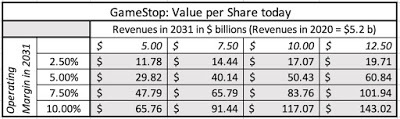

Note that this valuation is an optimistic one, assuming that probability of failure remains low, and that GameStop makes it way back to find a market in a post-COVID world, while also improving its margins to online retail levels. If you believe this valuation, you would have been a strong buyer of GameStop for much of last year, since it traded well below my $47 estimate. After the spectacular price run up in the last two weeks, though, there is no valuation justification left. To see why, take a look at how much the value per share changes as you change your assumptions about revenues and operating margins, the two key drivers of value.

Even if GameStop is able to more than double its revenues over the next decade, which would require growth in revenues of 15% a year for the next five years, and improve its margins to 12.5%, a supreme reach for a company that has never earned double digit margins over its lifetime, the value per share is about half the current stock price. Put simply, there is no plausible story that can be told about GameStop that could justify paying a $100 price, let alone $300 or $500.

The Backstory

To put the GameStop trading frenzy in perspective, let's start with the recognition that markets are not magical mechanisms, but represent aggregations of human beings making investment judgments, some buying and some selling, for a variety of reasons, ranging from the absurd to the profound. It should therefore not come as a surprise that the forces playing out in other aspects of human behavior find their way into markets. In particular, there are three broad trends from the last decade at play here:

A loss of faith in experts (economic, scientific, financial, government): During the 20th century, advances in education, and increasing specialization created expert classes in almost every aspect of human activity, from science to government to finance/economics. For the most part, we assumed that their superior knowledge and experience equipped them to take the right actions, and with our limited access to information, we often were kept in the dark, when they were wrong. That pact has been shattered by a combination of arrogance on the part of experts and catastrophic policy failures, with the 2008 banking crisis acting as a wake up call. In the years since, we have seen this loss of faith play out in economics, politics and even health, with expert opinion being cast aside, ignored or ridiculed. An unquestioning worship of crowd wisdom, combined with an empowering of crowds: In conjunction, we have also seen the rise of big data and the elevation of "crowd" judgments over expert opinions, and it shows up in our life choices. We pick the restaurants we eat at, based on Yelp reviews, the movies we watch on Rotten Tomatoes and the items we buy on customer reviews. Social media has made it easier to get crowd input (online), and precipitate crowd actions.A conversion of disagreements in every arena into the personal and the political: While we can continue to debate the reasons, it remains inarguable that public discourse has coarsened, with the almost every debate, no matter in what realm, becoming personal and political. I can attest to that from just my personal experiences, especially when I post on what I call "third rail" topics, specifically Tesla and Bitcoin, in the last few years. As I look at the GameStop episode play out, I see all three of these at play. One reason that the Redditors targeted GameStop is because they viewed hedge funds as part of the "expert" class, and consequently incapable of getting things right. They have used social media platforms to gather and reinforce each others' views, right or wrong, and then act in concert quickly and with extraordinary efficiency, to move stock prices. Finally, even a casual perusal of the comments on the Reddit thread exposes how much of this is personal, with far more comments about how this would teach hedge funds and Wall Street a lesson than there were about GameStop the company.The End GameI am a realist and if you are one of those who bought GameStop or AMC in recent days, I know that there is only a small chance that you will be reading this post, since I am probably too old (my four children remind me of that every day), too establishment (I have been teaching investing and valuation for 40 years) and too expert to be worth listening to. I accept that, though if you are familiar with my history, you should know that I have been harsh on how investing gets practiced in hedge funds, investment banks and even Omaha. The difference, I think, between our views is that many of you seem to believe that hedge funds (and other Wall Streeters) have been winning the investment sweepstakes, at your expense, and I believe that they are much too incompetent to do so. In my view, many hedge funds are run by people who bring little to the investment table, other than bluster, and charge their investors obscene amounts as fees, while delivering sub-standard results, and it is the fees that make hedge fund managers rich, not their performance. It is for that reason that I have spent my lifetime trying to disrupt the banking and money management business by giving away the data and the tools you need to do both for free, as well as pretty much everything I know (which is admittedly only a small subset) about investing in my classes. My sympathies lie with you, but I wonder what your end game is, and rather than pre-judge you, I will offer you the four choices: GameStop is a good investment: That may be a viable path, if you bought GameStop at $40 or $50, but not if you paid $200 or $300 a share. At those prices, I don’t see how you get value for your money, but that may reflect a failure of my imagination, and I encourage you to download my spreadsheet and make your own judgments.GameStop remains a good trade: You may believe that given your numbers (as individual investors), you can sell the stock to someone else at a higher price, but to whom? You may get lucky and be able to exit before everyone else tries to, but the risk that you will be caught in a stampede is high, as everyone tries to rush the exit doors at the same time. In fact, the constant repetition of the mantra that you need to hold to meet a bigger cause (teach Wall Street a lesson) should give you pause, since it is buying time for others (who may be the ones lecturing you) to exit the stock. I hope that I am wrong, but I think that the most likely end game here is that AMC, GameStop and Blackberry will give back all of the gains that they have had from your intervention and return to pre-action prices sooner rather than later.Teach hedge funds and Wall Street a lesson: I won't patronize you by telling you either that I understand your anger or that you should not be angry. That said, driving a few hedge funds out of business will do little to change the overall business, since other funds will fill the void. If this is your primary reason, though, just remember that the money you are investing in GameStop is more donation to a cause, than an investment. If you are investing tuition money, mortgage savings or your pension fund in GameStop and AMC, you are impoverishing yourself, trying to deliver a message that may or may not register. The biggest threat to hedge funds does not come from Reddit investor groups or regulators, but from a combination of obscene fee structures and mediocre performance. Play savior: It is possible that your end game was selfless, and that you were trying to save AMC and GameStop as companies, but if that was the case, how has any of what’s happened in the last two weeks help these companies? Their stock prices may have soared, but their financial positions are just as precarious as they were two weeks ago. If your response is that they can try to issue shares at the higher prices, I think of the odds of being able to do this successfully are low for two reasons. The first is that planning a new share issuance takes time, requiring SEC filings and approval. The second is that the very act of trying to issue new shares at the higher price may deflate that price. In a perverse way, you might have made it more difficult for GameStop and AMC to find a pathway to survive as parts of larger companies, by pushing up stock prices, and making them more expensive as targets.If you are in this game, at least be clear with yourself on what your end game is and protect yourself, because no one else will. The crowds that stormed the Bastille for the French Revolution burned the prison and killed the governor, but once done, they turned on each other. Watch your enemies (and I know that you include regulators and trading platforms in here), but watch your friends even more closely!

Market LessonsIf you are not a hedge fund that sold short on the targeted stocks, or a trader who bought in on other side, are there any consequences for you, from this episode? I do think that we sometimes read too much into market events and episodes, but this short period has some lessons.Flattening of the Investment World: Borrowing a term from Tom Friedman, I believe that the investment world has flattened over the last few decades, as access to data and powerful tools widens, and trading eases. It should come as no surprise then that portfolio managers and market gurus are discovering that they no longer are the arbiters of whether markets are cheap or expensive, and that their path of least resistance might come from following what individual investors do, rather than lead them. In a prior post, I pointed to this as one reason why risk capital stayed in the game in 2020, confounding many long-term market watchers, who expected it to flee. Emptiness of Investment Expertise: Professional money management has always sold its wares (mutual funds, hedge funds, investment advice) as the products of deep thinking and serious analysis, and as long as the processes stayed opaque and information was scanty, they were able to preserve the delusion. In the last few decades, as we have stripped away the layers, we have discovered how little there is under the surface. The hand wringing on the part of money managers about the momentum trading and absence of attention to fundamentals on the part of Redditors strikes me as hypocritical, since many of these money managers are themselves momentum players, whose idea of fundamentals is looking at trailing earnings. My prediction is that this episode and others like it will accelerate the shift from active to passive investing, especially on the part of investors who are paying hefty fees, and receiving little in return.Value ≠ Price: I won’t bore you again with my distinction between value and price, but it stands me in good stead during periods like this one. During the last week, I have been asked many times how I plan to change the way I value companies, as a result of the GameStop story, and my answer is that I don’t. That is not because I am stuck in my ways, but because almost everything that is being talked about (the rising power of the individual investors, the ease of trading on apps like Robinhood, the power of social media investing forums to create crowds) are factors that drive price, not value. It does mean that increasing access to data and easing trading may have the perverse effect of causing price to vary more, relative to value, and for longer periods. My advice, if you are an investor who believes in fundamentals, is that you accept this as the new reality and not drive yourself in a frenzy because you cannot explain what other people are paying for Tesla, Airbnb or Zoom.In the next few weeks, I predict that we will hear talk of regulatory changes intended to protect investors from their own excesses. If the regulators have their way, it will get more difficult to trade options and borrow money to buy shares, and I have mixed feelings about the efficacy of these restrictions. I understand the motivation for this talk, but I think that the best lessons that you learn about risk come from taking too much or the wrong risks, and then suffering the consequences.

YouTube Video

SpreadsheetValuation of GameStop (January 28, 2021)

January 27, 2021

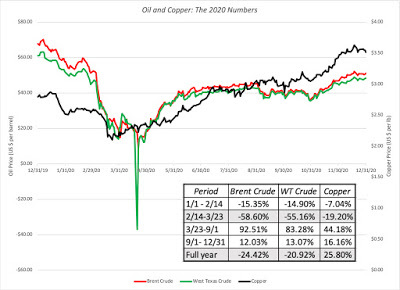

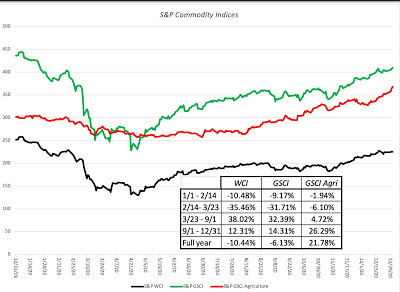

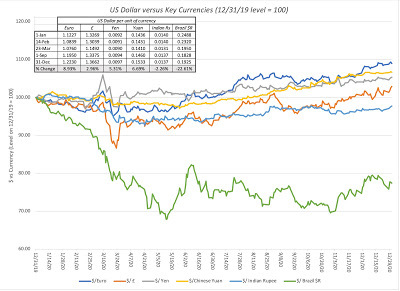

Data Update 3 for 2021: Currencies, Commodities, Collectibles and Cryptos

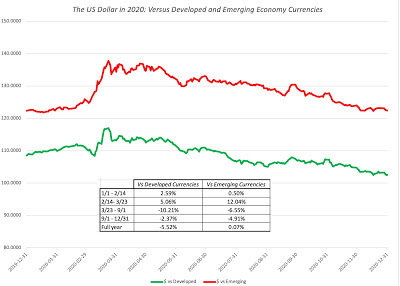

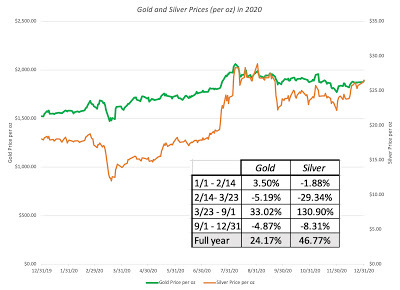

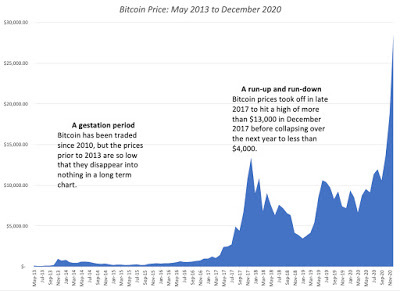

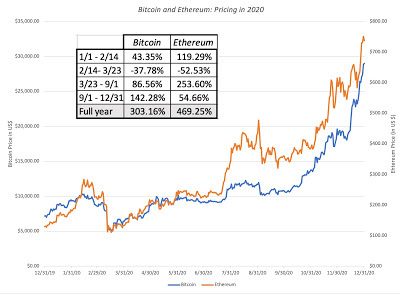

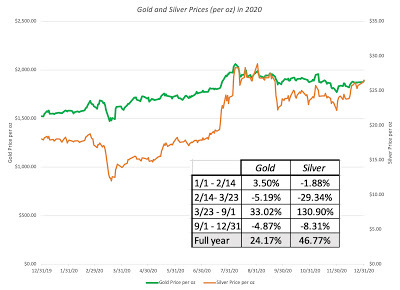

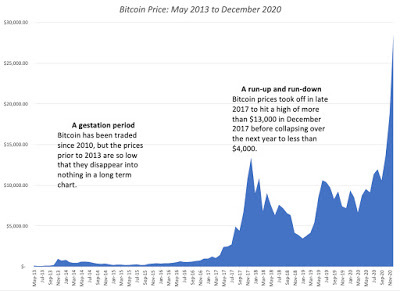

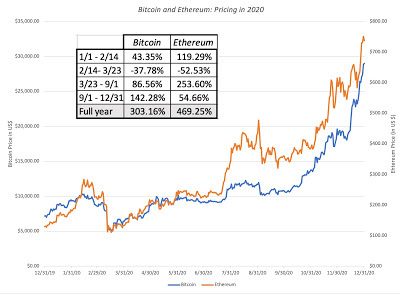

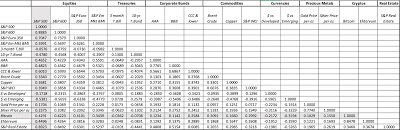

In my last post, I described the wild ride that the price of risk took in 2020, with equity risk premiums and default spreads initially sky rocketing, as the virus led to global economic shutdowns, and then just as abruptly dropping back to pre-crisis levels over the course of the year. As stock and bond markets went through these gyrations, it should come as no surprise that the same forces were playing out in other markets as well. In this post, I will take a look at these other markets, starting with a way of dividing investments into assets, commodities, currencies and collectibles that I find useful in thinking about what I can (and cannot) do in those markets, and then reviewing how these markets performed during 2020. As I do this, there is no way that I can evade discussing Bitcoin and other crypto assets, which continued to draw disproportionate (relative to their actual standing in markets) attention during the year, and talking about what 2020 taught us about them.

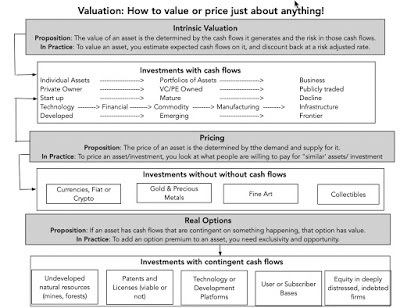

Investments: Classifications and Consequences

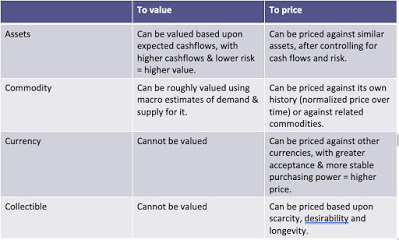

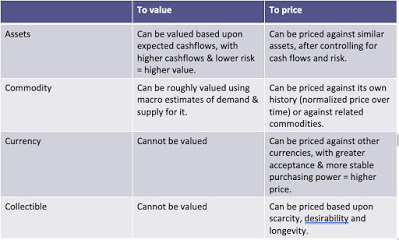

In a 2017 post, focused on bitcoin, I argued that all investments can be categorized into one of four groups, assets, commodities, currencies and collectibles, and the differences across these group are central to understanding why pricing is different from value, and what sets investing apart from trading.

The Divide: Assets, Commodities, Currencies and Collectibles

If you define an investment as anything that you can buy and hold, with the intent of making money, every investment has to fall into at least one of these groupings:

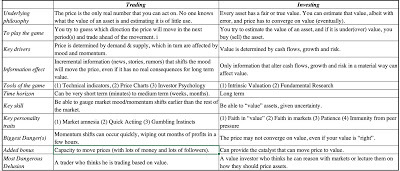

Assets: An asset has expected cash flows that can either be contractually set (as they are with loans or bonds), residual (as is the case with an equity investment in a business or shares in a publicly traded company) or even conditional on an event occurring (options and warrants). Commodities: A commodity derives its value from being an input into a process to produce a item (product or service) that consumers need or want. Thus, agricultural products like wheat and soybeans are commodities, as are industrial commodities like iron ore and copper, and energy-linked commodities like oil and natural gas. Currencies: A currency serves three functions. It is a measure of value (used to tell you how much a product or service costs), a medium of exchange (facilitating the buying and selling of products and services) and a store of value (allowing people to save to meet future needs). While we tend to think of fiat currencies like this Euro, the US dollar or the Indian rupee, the use of currency pre-dates governments, and human beings have used everything from seashells to rocks as currency.Collectibles: A collectible's pricing comes from the perception that it has value, driven by tastes (artwork) and/or scarcity (rare items). There are a range of items that fall into this grouping from fine art to sports memorabilia to precious metals.While most investments fall into one of these buckets, there are some that can span two or more, and you have to decide which one dominates. Take gold, for instance, whose ductility and malleability makes it a prized commodity to jewelers and electronics makers, but whose scarcity and indestructibility (almost) make it even more attractive as a currency or a collectible, With bitcoin, even its most ardent promoters seem to be divided on whether the end game is to create a currency or a collectible, a debate that we will revisit at the end of this post.Price versus ValueThe classification of investments is key to understanding a second divide, one that I have repeatedly returned to in my posts, between value and price.

If the value of an investment is a function of its cashflows and the risk in those cash flows, it follows that only assets can be valued. Though commodities can sometimes be roughly valued with macro estimates of demand and supply, they are far more likely to be priced. Currencies and collectible can only be priced, and the determinants of their pricing will vary:Commodity Pricing: With commodities, the pricing will be determined by two factors. The first is the demand for and supply of the commodity, given its usage, with shocks to either causing price to change. Thus, it should come as no surprise that the oil embargo in the 1970s caused oil prices to surge and freezing weather in Florida resulted in higher prices for orange juice. The second is storability, with storage costs ranging from minimal with some commodities to prohibitive for others. In general, storable commodities provide buyers with the option of buying when prices are low, and storing the commodity, and for that reason, futures prices of storable commodities are tied to spot prices and storage costs.Currency Pricing: Currencies are priced against each other, with the prices taking the form of "exchange rates". In the long term, that pricing will be a function of how good a currency is as a medium of exchange and a store of value, with better performing currencies gaining at the expense of worse performing ones. On the first dimension (medium of exchange) currencies that are freely exchangeable (or even usable) anywhere in the world (like the US dollar, the Euro and the Yen) will be priced higher than currencies that do not have that reach (like the Indian rupee or the Peruvian Sul). On the second (store of value), it is inflation that separates good from bad currencies, with currencies with low inflation (like the Swiss franc) gaining at the expense of currencies with higher inflation (like the Zambian kwacha). Collectible Pricing: Most collectibles are pure plays on demand and supply, with no fundamentals driving the price, other than scarcity and desirability, real or perceived. Paintings by Picasso, Monet or Van Gogh are bought and sold for millions, because there are collectors and art lovers who see them as special works of art, and their supply is limited. Adding to the allure (and pricing) of collectibles is their longevity, reflected in their continuous hold on investor consciousness. It should come as no surprise that gold's, because it brings together all three characteristics; it's scarcity comes from nature, its desirability comes from in many forms and it has been used and valued for thousands of years.I capture these differences in the table below: