Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 9

January 27, 2022

Data Update 3 for 2022: Inflation and its Ripple Effects!

Inflation numbers have been coming in high now, for more than a year, but for much of the early part of 2021, bankers, investors and politicians seemed to be either in denial or casually dismissive of its potential for damage. Initially, the high inflation numbers were attributed to the speed with the economy was recovering from COVID, and once that excuse fell flat, it was the supply chain that was help responsible. By the end of 2021, it was clear that this bout of inflation was not as transient a phenomenon as some had made it out to be, and the big question leading in 2022, for investors and markets, is how inflation will play out during the year, and beyond, and the consequences for stocks, bonds and currencies.

Inflation: Measurement and Determinants

As the inflation debate was heating up in the middle of last year, I wrote a comprehensive post on how inflation is measured, what causes it and how it affects returns on different asset classes. Rather than repeat much of that post, let me summarize my key points.

Measuring inflation is not as simple as it looks, and measures of inflation can vary depending on the basket of good/services used, the perspective adopted (consumer, producer, GDP deflator) and the sampling used to collect prices. That said, the three primary inflation indices in the US, the CPI, the PPI and the GDP deflator all told the same story in 2021: Download historical inflation numbers

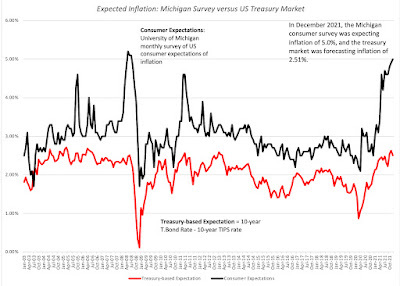

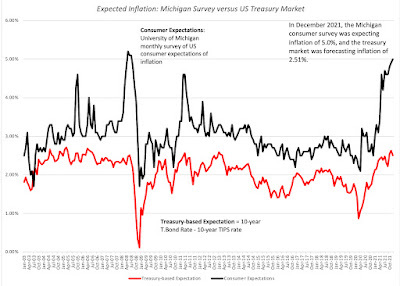

Download historical inflation numbersThe inflation rate during the course of the year reached levels not seen in close to 40 years, with every price index registering a surge.While news stories focus on reported (and past0 inflation, it is expected inflation that should drive investment, and measures of these expectations can come from surveys of consumers (University of Michigan) or from the market, as the difference between the treasury bond rate and the inflation-protected treasury bond, of equivalent maturity:

Download data

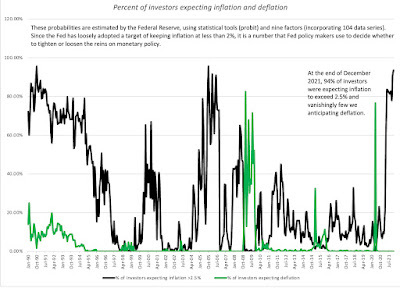

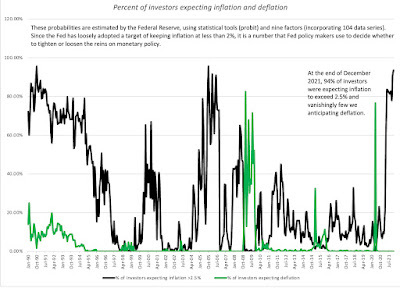

Download dataUsing the ten-year bond, it is clear that while inflation expectations have inched up in the bond market, but that rise is far more muted than in the actual inflation indices, and consumer expectations of inflation now significantly exceed the bond-market imputed estimate for expected inflation.While the implied inflation in bond rates is low, investors seem to be anticipating higher inflation. Using a measure that the Federal Reserve has developed, I report the percent of investors expecting inflation to be greater than 2.5%, representing one end of the inflation expectation spectrum, and those expecting deflation, representing the other, in the graph below:

Download dataAs you can see the 93.96% of investors were expecting inflation to be greater than 2.5%, by the end of December 2021, up from 6.74% in December 2020, suggesting a sea change in the market. Conversely, the percent of investors expecting deflation has dropped to a vanishing low number, suggesting that Cathie Wood has little company, in her contention that deflation is the real danger to markets and economies.The undeniable fact is that inflation came back in 2021, but the question of why it happened, and whether it will stay high, is hotly debated. To those who believe that it is a spike that will dissipate over time, it is another casualty of COVID, as a combination of virus-driven supply chain issues and government spending to offset shutdowns has driven prices up. In this mostly benign story, inflation will go back down, once these pressure ease, though it is unclear to what level. To others, and especially those old enough to remember the 1970s, it does seem like a return to more unsettled times, with potentially dangerous consequences for the economy and markets.

Download dataAs you can see the 93.96% of investors were expecting inflation to be greater than 2.5%, by the end of December 2021, up from 6.74% in December 2020, suggesting a sea change in the market. Conversely, the percent of investors expecting deflation has dropped to a vanishing low number, suggesting that Cathie Wood has little company, in her contention that deflation is the real danger to markets and economies.The undeniable fact is that inflation came back in 2021, but the question of why it happened, and whether it will stay high, is hotly debated. To those who believe that it is a spike that will dissipate over time, it is another casualty of COVID, as a combination of virus-driven supply chain issues and government spending to offset shutdowns has driven prices up. In this mostly benign story, inflation will go back down, once these pressure ease, though it is unclear to what level. To others, and especially those old enough to remember the 1970s, it does seem like a return to more unsettled times, with potentially dangerous consequences for the economy and markets.Interest Rates and Inflation

Inflation and interest rates are intertwined, and when their paths deviate, as they sometimes do, there is always a reckoning. While we have increasingly given central banks primacy in discussions of interest rates, it remains my view that markets set rates, and while central banks can nudge market expectations, they cannot alter them. Put simply, no central bank, no matter how powerful, can force market interest rates down, if inflation expectations stay low, or up, if investor are anticipating high inflation.

US Treasuries: A Mostly Uneventful Year

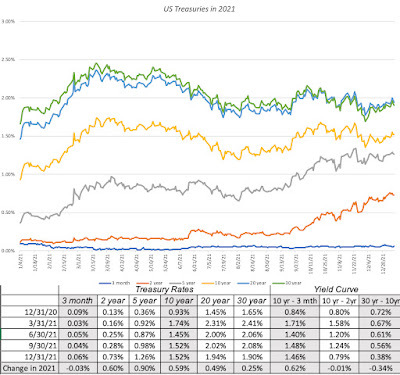

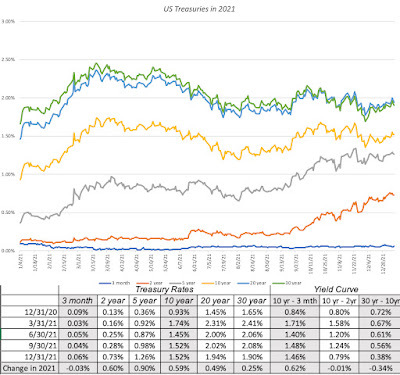

After a turbulent year in 2020, when COVID shut the global economy down, and interest rates plunged and stayed down for the rest of the year, 2021 was a more settled year, with long term rates rising gradually over the course of the year, but short terms rates staying put:

Treasury Rates Data

Treasury Rates DataWhile treasury bills continued to yield rates close to zero, rates increased for longer term treasuries, with 2-10 years rates rising much more than rates on the longest term treasuries (20-year to 30-year). For those who track the slope of the yield curve, and I am not one of those who believes that it has much predictive power, it was a confusing year. The treasury curve became steeper, but only at the shortest end of the spectrum, with the slope rising for the 2-year, relative to the 3-month, but not at all, when comparing the 10-year to the 2-year rate. Beyond the 10-year maturity, the slope of the yield curve actually flattened out, with the difference between the 30-year rate and the 10-year rate declining by 0.34%.

Corporate Bonds: No Shortage of Risk Capital

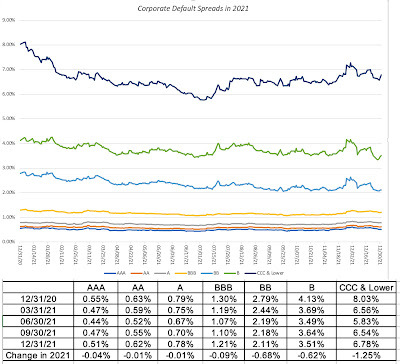

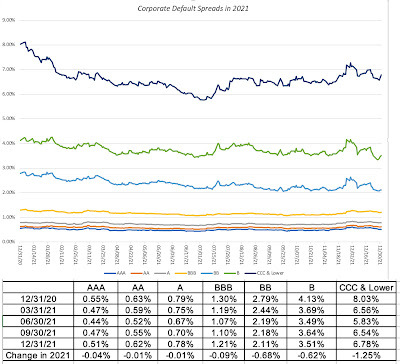

In my last post, I chronicled the movement in the equity risk premium, i.e. the price of risk in the equity market, during 2021, but the bond market has its own, and more measurable, price of risk in the form of corporate default spreads. Using bond ratings classes to categorize companies, based upon credit risk, I looked at the movement of default spreads during 2021:

Download data

Download dataCorporate default spreads decrease across ratings classes, but the decline is much larger for lower rated bonds, with the default spread on high yield bonds registering a drop of 1.25%. Note that the decrease in default spreads, at least for the lower ratings, mirrors the drop in the implied equity risk premium during the course of 2021. Read together, it suggests that private risk capital continued to not just stay in the game, but increased its stake during the course of the year, extending a decade-long run.

Expected Inflation, Interest Rates and Bond Returns

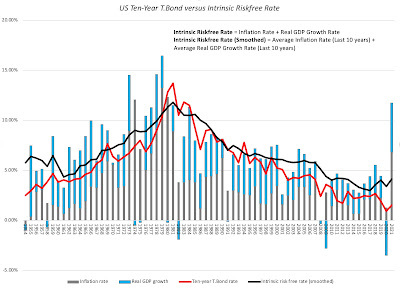

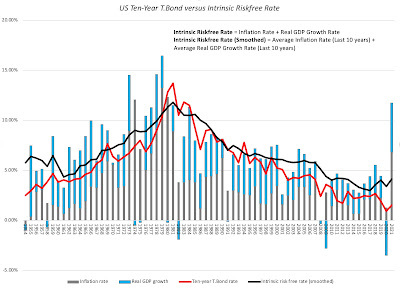

While day to day movements in interest rates are driven by multiple forces, including the latest smoke signals coming from central banks and investor sentiment, the longer term and drivers of interest rates are fundamental. In particular, if you start by breaking down a long term riskfree rate (like the 10-year treasury bond) into an expected inflation and an expected real interest rate components, you can also reconstruct an intrinsic risk free rate by assuming that the real growth in the economy is a stand-in for the real interest rate and that most investors form expectations of future inflation by looking at the inflation in the most recent year(s):

Download data

Download dataIn this picture, ythe actual ten-year treasury bond rate is superimposed against a rough measure of the intrinsic risk free rate (obtained by adding together the actual inflation rate and real growth rate each year) and a smoothed out version (where I used the average inflation rate and real growth rate over the previous ten years). Not only has the intrinsic risk free rate moved in sync with the ten-year bond rate for most of the last seven decades, but you can also see that the main reason why rates have been low for the last decade is not the Fed, with all of its quantitative easing machinations, but a combination of low growth and low inflation. Coming into 2022, though, the intrinsic risk free rate is clearly running ahed of the ten-year treasury bond rate, and if history is any guide, that gap will close either with a rise in the treasury bond rate or a decline in the risk free rate (coming from a recession or a rapid drop off in inflation).

Unexpected Inflation and Asset Returns

Note that it is expected inflation that drives interest rates, and that the actual inflation rate can come in above or below expectations. In my post on inflation last year, I drew a contrast between expected and unexpected inflation, arguing that financial assets are affected differently by each component. If expected inflation is high, but it is predictable, investors and businesses have the opportunity to incorporate that inflation into their decision making, with investors demanding higher interest rates on bond and expected returns on stocks, and businesses raising prices on their products/services to cover expected inflation. Unexpected inflation is what catches us off guard, with unexpectedly high inflation leading to a reassessment of pricing (for all financial assets) and an uneven impact across businesses, leaving those with pricing power in a better position than those without that power.

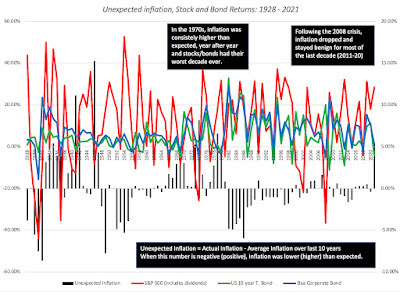

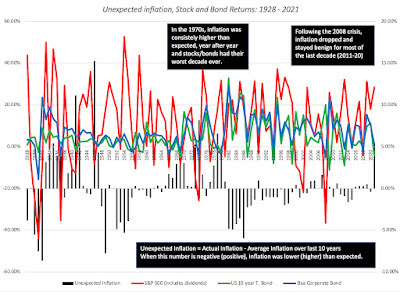

To assess how inflation has affected asset returns over time, I broke down the actual inflation rates since 1954 into expected and unexpected components each year, using a brute force assumption that the average inflation rate over the last ten years is the expected inflation rate. (In the last two decades, we have had access to more sophisticated measures of expected inflation, including the difference between the nominal treasury bond and TIPs rates, but not in earlier years). In the graph below, I look at annual returns on stocks, treasury bonds and corporate bonds, with the unexpected inflation numbers also shown:

There are a few aspects of this graph that stand out. With my crude measure of inflation expectations, it looks like it takes time for inflation expectations to shift, during periods of higher or lower inflation, as can be seen in the extended stretches of higher than expected inflation, in the 1970s, and lower than expected inflation in the 1980s.

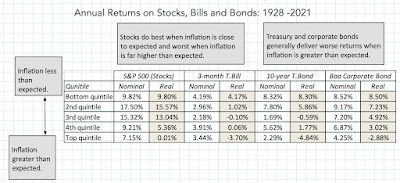

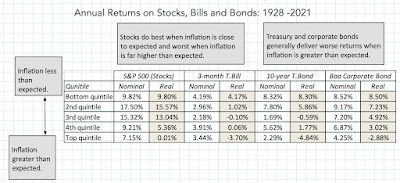

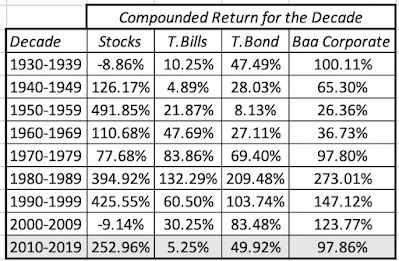

While it is not immediately visible in the graph, returns on stocks and bonds are affected by unexpected inflation, and to illustrate by how much, I broke the 94 years of data into five quartiles, based upon the level of unexpected inflation, with the lowest (highest) quintile representing the years when inflation came in most below (above) expectations, and estimated the annual returns (nominal and real) for stocks, treasuries and corporate bonds in the table below:

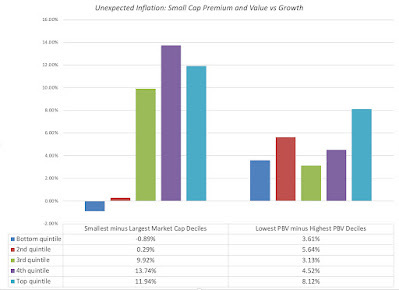

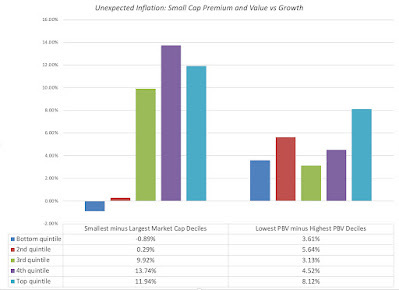

With treasuries and corporates, the returns generally get worse, as inflation comes in above expectations, with real returns showing the damage from unexpected inflation. With equities, the sweet spot in terms of returns is when inflation is at or below expectations, and the worst scenarios are when inflation comes in well above expectations. I also looked at how inflation plays out on equity sub-groupings, on two dimensions, the first being market capitalization and the second being price to book, with the former becoming a stand-in for the vaunted small cap premium and the latter for the value versus growth question.

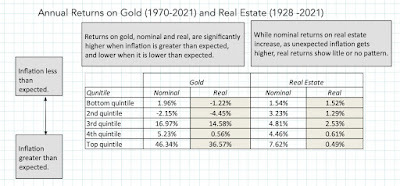

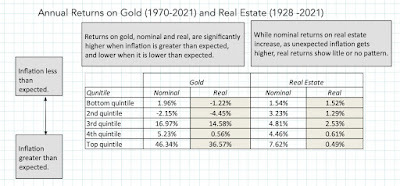

Over much of the last century, small cap stocks have done better than large cap stocks, when inflation has come in well above expectations, perhaps providing some insight into why the vaunted small cap premium seems have to disappeared over the last two decades of muted inflation. Similarly, the value effect, computed as the premium (or discounted) return earned by low price to book stocks over high price to book, becomes more pronounced during periods when inflation is greater than expected and much less so, during periods when inflation is lower than anticipated. Using the same approach with gold and real estate, with the caveat that historical data on the former is more limited, I get the following results:

While gold and real estate both do better than financial assets, when inflation is greater than expected, there is also a clear difference between the two investment classes. Real estate operates more as a neutral hedge, delivering returns that are, for the most part, unscathed by unexpectedly high inflation, but gold is a bet on inflation, delivering the highest returns, when inflation is much greater than expected, and negative returns, when it is lower than expected. Much as I would like to extend this analysis to newer investment classes, there is not enough historical data on crypto currencies or NFTs to allow for the analysis. As I noted in my inflation post in 2021, though, the early evidence is not promising for these new investment categories, at least as inflation and crisis hedges, since they have behaved more like risky equities, at least on a day-to-day basis and during the 2020 crisis, than like gold.

While gold and real estate both do better than financial assets, when inflation is greater than expected, there is also a clear difference between the two investment classes. Real estate operates more as a neutral hedge, delivering returns that are, for the most part, unscathed by unexpectedly high inflation, but gold is a bet on inflation, delivering the highest returns, when inflation is much greater than expected, and negative returns, when it is lower than expected. Much as I would like to extend this analysis to newer investment classes, there is not enough historical data on crypto currencies or NFTs to allow for the analysis. As I noted in my inflation post in 2021, though, the early evidence is not promising for these new investment categories, at least as inflation and crisis hedges, since they have behaved more like risky equities, at least on a day-to-day basis and during the 2020 crisis, than like gold.Inflation and Currencies Much of this post has been about inflation in the US, and by extension, in US dollar terms, it is worth emphasizing that inflation is a currency-specific phenomenon. While inflation in the US dollar, by dint of its status as the currency in which commodities are priced, can sometimes spill over into other currencies, it remains true that you can have high inflation in one currency, while there is low inflation in other currencies. Inflation differences across currencies play out in two domains, with the first being interest rates in different currencies and the other being exchange rate.

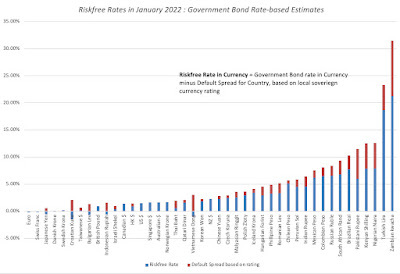

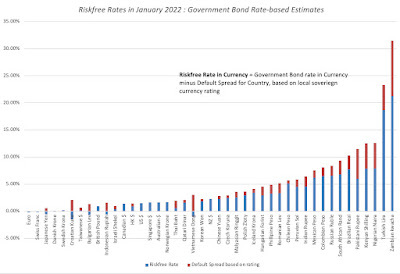

Interest Rates across Currencies I start every one of my discussions of discount rates with a truism, by stating that the riskfree rate that you start with should reflect the currency in which you have decided to do your valuation. That then becomes the springboard for estimating risk free rates in different currencies, following one of two paths. In the first, you start with government bond rates in the local currency, in different currencies, and adjust those rates for default risk in the local currency government bond. (Government bonds in local currencies do default, and account for a significant proportion of sovereign defaults in the last 50 years). My estimates for the start of 2022 for the currencies where local-currency government bonds are available is below:

Download data

Download data

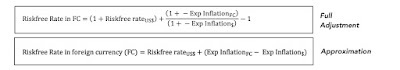

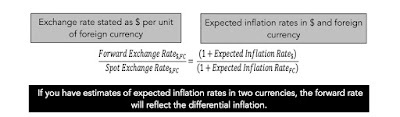

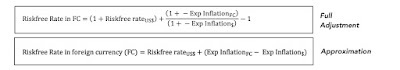

Riskfree rates are highest in currencies, like the Zambian Kwacha or Turkish Lira, where inflation is highest, lower in low-inflation currencies and even negative in currencies, where deflation may be the long term prediction. I am using the default spreads based upon the local currency sovereign ratings for the countries in question, with the government bond rate being the risk free rate only for currencies where the issuing government in triple-A rated. If you dislike this assumption, or do not believe that the government bond rate is a market-set number in a particular market, there is a second approach, where you start with the risk free rate in US dollar or Euros, and adjust it for differential inflation, i.e., the difference in expected inflation between the US and the country in question:

Thus, if the US treasury bond rate is 1.5%, and expected inflation rates in the US and Indonesia are 1% and 4% respectively, the approximate riskfree rate in Indonesian Rupiah will be 4.5% (=1.5% + (4%-1%)) and the more precise riskfree rate in Rupiah will be 4.52% (=1.015*(1.04/1.01)-1). While the expected inflation rate in dollars may be an easy get, it is more difficult to get expected inflation rates in other currencies, but the IMF has estimates for the next five years at this link.

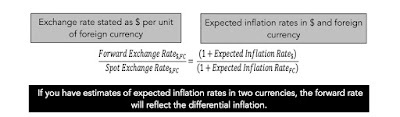

Thus, if the US treasury bond rate is 1.5%, and expected inflation rates in the US and Indonesia are 1% and 4% respectively, the approximate riskfree rate in Indonesian Rupiah will be 4.5% (=1.5% + (4%-1%)) and the more precise riskfree rate in Rupiah will be 4.52% (=1.015*(1.04/1.01)-1). While the expected inflation rate in dollars may be an easy get, it is more difficult to get expected inflation rates in other currencies, but the IMF has estimates for the next five years at this link.Exchange Rates Just as interest rates in currencies are determined, in large part, by inflation differentials, exchange rates over time are also driven by those same inflation differentials. Drawing on one of the oldest relationships in exchange rates, purchasing power parity, you can extract the forward exchange rate in a currency:

Thus, currencies with higher inflation can be expected currency devaluation over time, relative to currencies with lower inflation. As with interest rates, in the short term, there are forces, ranging from central banking intervention to momentum and speculation, that can cause rates to deviate from the inflation script, but in the long term, it is almost impossible to break the cycle. Connecting this linkage to the discussion of US inflation in the prior sections, here are the takeaways. If you believe that inflation will stay high, not just in the US, but across the globe, the exchange rate effects will be muted. If, on the other hand, you believe that the inflation shock will vary across countries, your actions will be more nuanced. For the countries where you believe that local inflation will decrease, relative to the US, the US dollar will weaken against their currencies, augmenting returns you will earn in their markets (stock or bond). For countries, where you see local inflation surging more than you expect to see in the US, the US dollar will strengthen against their currencies, reducing the returns you make in their markets. As with the discussion of asset returns, it is not expected inflation that is the source of exchange rate risk, since you can incorporate those expectations into exchange rates, but unexpected inflation, which, when extreme, can cause significant revaluations of currencies.

Conclusion As with any historical data assessment, I could give you the standard boilerplate disclaimer that past performance is not always a good predictor of the past, but to the extent that the past provides signals, your expectations of how inflation will play out in the coming year will play a key role in your asset allocation and stock selection decisions. If you believe that last year's surge in inflation is a precursor to a long time period when inflation is likely to stay high, and come in above expectations, you should be shifting your holdings away from financial to real assets, and within your equity holdings, towards small cap stocks, stocks trading at lower pricing multiples (PE, Price to Book) and companies with more pricing power. If, on the other hand, you believe that inflation worries are overdone, and that there will be a reversion back to the low inflation that we have seen in the last decade, staying invested in stocks, and especially in larger cap and high growth stocks, even if richly priced, makes sense.

YouTube Video

Data LinksInflation Data: CPI, PPI and GDP DeflatorIntrinsic versus Actual T.Bond Rates: 1954-2021Inflation and Returns on Asset ClassesRiskfree Rates in Currencies (Government Bond based estimates)Blog Post LinksInflation and Investing: False Alarm or Fair Warning?The Fed, Interest Rates and Stock Prices: Fighting the Fear Factor

Data Update 3: Inflation and its Ripple Effects!

Inflation numbers have been coming in high now, for more than a year, but for much of the early part of 2021, bankers, investors and politicians seemed to be either in denial or casually dismissive of its potential for damage. Initially, the high inflation numbers were attributed to the speed with the economy was recovering from COVID, and once that excuse fell flat, it was the supply chain that was help responsible. By the end of 2021, it was clear that this bout of inflation was not as transient a phenomenon as some had made it out to be, and the big question leading in 2022, for investors and markets, is how inflation will play out during the year, and beyond, and the consequences for stocks, bonds and currencies.

Inflation: Measurement and Determinants

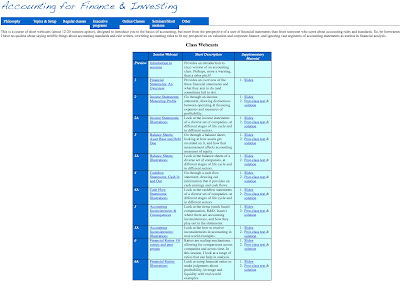

As the inflation debate was heating up in the middle of last year, I wrote a comprehensive post on how inflation is measured, what causes it and how it affects returns on different asset classes. Rather than repeat much of that post, let me summarize my key points.

Measuring inflation is not as simple as it looks, and measures of inflation can vary depending on the basket of good/services used, the perspective adopted (consumer, producer, GDP deflator) and the sampling used to collect prices. That said, the three primary inflation indices in the US, the CPI, the PPI and the GDP deflator all told the same story in 2021: Download historical inflation numbers

Download historical inflation numbersThe inflation rate during the course of the year reached levels not seen in close to 40 years, with every price index registering a surge.While news stories focus on reported (and past0 inflation, it is expected inflation that should drive investment, and measures of these expectations can come from surveys of consumers (University of Michigan) or from the market, as the difference between the treasury bond rate and the inflation-protected treasury bond, of equivalent maturity:

Download data

Download dataUsing the ten-year bond, it is clear that while inflation expectations have inched up in the bond market, but that rise is far more muted than in the actual inflation indices, and consumer expectations of inflation now significantly exceed the bond-market imputed estimate for expected inflation.While the implied inflation in bond rates is low, investors seem to be anticipating higher inflation. Using a measure that the Federal Reserve has developed, I report the percent of investors expecting inflation to be greater than 2.5%, representing one end of the inflation expectation spectrum, and those expecting deflation, representing the other, in the graph below:

Download dataAs you can see the 93.96% of investors were expecting inflation to be greater than 2.5%, by the end of December 2021, up from 6.74% in December 2020, suggesting a sea change in the market. Conversely, the percent of investors expecting deflation has dropped to a vanishing low number, suggesting that Cathie Wood has little company, in her contention that deflation is the real danger to markets and economies.The undeniable fact is that inflation came back in 2021, but the question of why it happened, and whether it will stay high, is hotly debated. To those who believe that it is a spike that will dissipate over time, it is another casualty of COVID, as a combination of virus-driven supply chain issues and government spending to offset shutdowns has driven prices up. In this mostly benign story, inflation will go back down, once these pressure ease, though it is unclear to what level. To others, and especially those old enough to remember the 1970s, it does seem like a return to more unsettled times, with potentially dangerous consequences for the economy and markets.

Download dataAs you can see the 93.96% of investors were expecting inflation to be greater than 2.5%, by the end of December 2021, up from 6.74% in December 2020, suggesting a sea change in the market. Conversely, the percent of investors expecting deflation has dropped to a vanishing low number, suggesting that Cathie Wood has little company, in her contention that deflation is the real danger to markets and economies.The undeniable fact is that inflation came back in 2021, but the question of why it happened, and whether it will stay high, is hotly debated. To those who believe that it is a spike that will dissipate over time, it is another casualty of COVID, as a combination of virus-driven supply chain issues and government spending to offset shutdowns has driven prices up. In this mostly benign story, inflation will go back down, once these pressure ease, though it is unclear to what level. To others, and especially those old enough to remember the 1970s, it does seem like a return to more unsettled times, with potentially dangerous consequences for the economy and markets.Interest Rates and Inflation

Inflation and interest rates are intertwined, and when their paths deviate, as they sometimes do, there is always a reckoning. While we have increasingly given central banks primacy in discussions of interest rates, it remains my view that markets set rates, and while central banks can nudge market expectations, they cannot alter them. Put simply, no central bank, no matter how powerful, can force market interest rates down, if inflation expectations stay low, or up, if investor are anticipating high inflation.

US Treasuries: A Mostly Uneventful Year

After a turbulent year in 2020, when COVID shut the global economy down, and interest rates plunged and stayed down for the rest of the year, 2021 was a more settled year, with long term rates rising gradually over the course of the year, but short terms rates staying put:

Treasury Rates Data

Treasury Rates DataWhile treasury bills continued to yield rates close to zero, rates increased for longer term treasuries, with 2-10 years rates rising much more than rates on the longest term treasuries (20-year to 30-year). For those who track the slope of the yield curve, and I am not one of those who believes that it has much predictive power, it was a confusing year. The treasury curve became steeper, but only at the shortest end of the spectrum, with the slope rising for the 2-year, relative to the 3-month, but not at all, when comparing the 10-year to the 2-year rate. Beyond the 10-year maturity, the slope of the yield curve actually flattened out, with the difference between the 30-year rate and the 10-year rate declining by 0.34%.

Corporate Bonds: No Shortage of Risk Capital

In my last post, I chronicled the movement in the equity risk premium, i.e. the price of risk in the equity market, during 2021, but the bond market has its own, and more measurable, price of risk in the form of corporate default spreads. Using bond ratings classes to categorize companies, based upon credit risk, I looked at the movement of default spreads during 2021:

Download data

Download dataCorporate default spreads decrease across ratings classes, but the decline is much larger for lower rated bonds, with the default spread on high yield bonds registering a drop of 1.25%. Note that the decrease in default spreads, at least for the lower ratings, mirrors the drop in the implied equity risk premium during the course of 2021. Read together, it suggests that private risk capital continued to not just stay in the game, but increased its stake during the course of the year, extending a decade-long run.

Expected Inflation, Interest Rates and Bond Returns

While day to day movements in interest rates are driven by multiple forces, including the latest smoke signals coming from central banks and investor sentiment, the longer term and drivers of interest rates are fundamental. In particular, if you start by breaking down a long term riskfree rate (like the 10-year treasury bond) into an expected inflation and an expected real interest rate components, you can also reconstruct an intrinsic risk free rate by assuming that the real growth in the economy is a stand-in for the real interest rate and that most investors form expectations of future inflation by looking at the inflation in the most recent year(s):

Download data

Download dataIn this picture, ythe actual ten-year treasury bond rate is superimposed against a rough measure of the intrinsic risk free rate (obtained by adding together the actual inflation rate and real growth rate each year) and a smoothed out version (where I used the average inflation rate and real growth rate over the previous ten years). Not only has the intrinsic risk free rate moved in sync with the ten-year bond rate for most of the last seven decades, but you can also see that the main reason why rates have been low for the last decade is not the Fed, with all of its quantitative easing machinations, but a combination of low growth and low inflation. Coming into 2022, though, the intrinsic risk free rate is clearly running ahed of the ten-year treasury bond rate, and if history is any guide, that gap will close either with a rise in the treasury bond rate or a decline in the risk free rate (coming from a recession or a rapid drop off in inflation).

Unexpected Inflation and Asset Returns

Note that it is expected inflation that drives interest rates, and that the actual inflation rate can come in above or below expectations. In my post on inflation last year, I drew a contrast between expected and unexpected inflation, arguing that financial assets are affected differently by each component. If expected inflation is high, but it is predictable, investors and businesses have the opportunity to incorporate that inflation into their decision making, with investors demanding higher interest rates on bond and expected returns on stocks, and businesses raising prices on their products/services to cover expected inflation. Unexpected inflation is what catches us off guard, with unexpectedly high inflation leading to a reassessment of pricing (for all financial assets) and an uneven impact across businesses, leaving those with pricing power in a better position than those without that power.

To assess how inflation has affected asset returns over time, I broke down the actual inflation rates since 1954 into expected and unexpected components each year, using a brute force assumption that the average inflation rate over the last ten years is the expected inflation rate. (In the last two decades, we have had access to more sophisticated measures of expected inflation, including the difference between the nominal treasury bond and TIPs rates, but not in earlier years). In the graph below, I look at annual returns on stocks, treasury bonds and corporate bonds, with the unexpected inflation numbers also shown:

There are a few aspects of this graph that stand out. With my crude measure of inflation expectations, it looks like it takes time for inflation expectations to shift, during periods of higher or lower inflation, as can be seen in the extended stretches of higher than expected inflation, in the 1970s, and lower than expected inflation in the 1980s.

While it is not immediately visible in the graph, returns on stocks and bonds are affected by unexpected inflation, and to illustrate by how much, I broke the 94 years of data into five quartiles, based upon the level of unexpected inflation, with the lowest (highest) quintile representing the years when inflation came in most below (above) expectations, and estimated the annual returns (nominal and real) for stocks, treasuries and corporate bonds in the table below:

With treasuries and corporates, the returns generally get worse, as inflation comes in above expectations, with real returns showing the damage from unexpected inflation. With equities, the sweet spot in terms of returns is when inflation is at or below expectations, and the worst scenarios are when inflation comes in well above expectations. I also looked at how inflation plays out on equity sub-groupings, on two dimensions, the first being market capitalization and the second being price to book, with the former becoming a stand-in for the vaunted small cap premium and the latter for the value versus growth question.

Over much of the last century, small cap stocks have done better than large cap stocks, when inflation has come in well above expectations, perhaps providing some insight into why the vaunted small cap premium seems have to disappeared over the last two decades of muted inflation. Similarly, the value effect, computed as the premium (or discounted) return earned by low price to book stocks over high price to book, becomes more pronounced during periods when inflation is greater than expected and much less so, during periods when inflation is lower than anticipated. Using the same approach with gold and real estate, with the caveat that historical data on the former is more limited, I get the following results:

While gold and real estate both do better than financial assets, when inflation is greater than expected, there is also a clear difference between the two investment classes. Real estate operates more as a neutral hedge, delivering returns that are, for the most part, unscathed by unexpectedly high inflation, but gold is a bet on inflation, delivering the highest returns, when inflation is much greater than expected, and negative returns, when it is lower than expected. Much as I would like to extend this analysis to newer investment classes, there is not enough historical data on crypto currencies or NFTs to allow for the analysis. As I noted in my inflation post in 2021, though, the early evidence is not promising for these new investment categories, at least as inflation and crisis hedges, since they have behaved more like risky equities, at least on a day-to-day basis and during the 2020 crisis, than like gold.

While gold and real estate both do better than financial assets, when inflation is greater than expected, there is also a clear difference between the two investment classes. Real estate operates more as a neutral hedge, delivering returns that are, for the most part, unscathed by unexpectedly high inflation, but gold is a bet on inflation, delivering the highest returns, when inflation is much greater than expected, and negative returns, when it is lower than expected. Much as I would like to extend this analysis to newer investment classes, there is not enough historical data on crypto currencies or NFTs to allow for the analysis. As I noted in my inflation post in 2021, though, the early evidence is not promising for these new investment categories, at least as inflation and crisis hedges, since they have behaved more like risky equities, at least on a day-to-day basis and during the 2020 crisis, than like gold.Inflation and Currencies Much of this post has been about inflation in the US, and by extension, in US dollar terms, it is worth emphasizing that inflation is a currency-specific phenomenon. While inflation in the US dollar, by dint of its status as the currency in which commodities are priced, can sometimes spill over into other currencies, it remains true that you can have high inflation in one currency, while there is low inflation in other currencies. Inflation differences across currencies play out in two domains, with the first being interest rates in different currencies and the other being exchange rate.

Interest Rates across Currencies I start every one of my discussions of discount rates with a truism, by stating that the riskfree rate that you start with should reflect the currency in which you have decided to do your valuation. That then becomes the springboard for estimating risk free rates in different currencies, following one of two paths. In the first, you start with government bond rates in the local currency, in different currencies, and adjust those rates for default risk in the local currency government bond. (Government bonds in local currencies do default, and account for a significant proportion of sovereign defaults in the last 50 years). My estimates for the start of 2022 for the currencies where local-currency government bonds are available is below:

Download data

Download data

Riskfree rates are highest in currencies, like the Zambian Kwacha or Turkish Lira, where inflation is highest, lower in low-inflation currencies and even negative in currencies, where deflation may be the long term prediction. I am using the default spreads based upon the local currency sovereign ratings for the countries in question, with the government bond rate being the risk free rate only for currencies where the issuing government in triple-A rated. If you dislike this assumption, or do not believe that the government bond rate is a market-set number in a particular market, there is a second approach, where you start with the risk free rate in US dollar or Euros, and adjust it for differential inflation, i.e., the difference in expected inflation between the US and the country in question:

Thus, if the US treasury bond rate is 1.5%, and expected inflation rates in the US and Indonesia are 1% and 4% respectively, the approximate riskfree rate in Indonesian Rupiah will be 4.5% (=1.5% + (4%-1%)) and the more precise riskfree rate in Rupiah will be 4.52% (=1.015*(1.04/1.01)-1). While the expected inflation rate in dollars may be an easy get, it is more difficult to get expected inflation rates in other currencies, but the IMF has estimates for the next five years at this link.

Thus, if the US treasury bond rate is 1.5%, and expected inflation rates in the US and Indonesia are 1% and 4% respectively, the approximate riskfree rate in Indonesian Rupiah will be 4.5% (=1.5% + (4%-1%)) and the more precise riskfree rate in Rupiah will be 4.52% (=1.015*(1.04/1.01)-1). While the expected inflation rate in dollars may be an easy get, it is more difficult to get expected inflation rates in other currencies, but the IMF has estimates for the next five years at this link.Exchange Rates Just as interest rates in currencies are determined, in large part, by inflation differentials, exchange rates over time are also driven by those same inflation differentials. Drawing on one of the oldest relationships in exchange rates, purchasing power parity, you can extract the forward exchange rate in a currency:

Thus, currencies with higher inflation can be expected currency devaluation over time, relative to currencies with lower inflation. As with interest rates, in the short term, there are forces, ranging from central banking intervention to momentum and speculation, that can cause rates to deviate from the inflation script, but in the long term, it is almost impossible to break the cycle. Connecting this linkage to the discussion of US inflation in the prior sections, here are the takeaways. If you believe that inflation will stay high, not just in the US, but across the globe, the exchange rate effects will be muted. If, on the other hand, you believe that the inflation shock will vary across countries, your actions will be more nuanced. For the countries where you believe that local inflation will decrease, relative to the US, the US dollar will weaken against their currencies, augmenting returns you will earn in their markets (stock or bond). For countries, where you see local inflation surging more than you expect to see in the US, the US dollar will strengthen against their currencies, reducing the returns you make in their markets. As with the discussion of asset returns, it is not expected inflation that is the source of exchange rate risk, since you can incorporate those expectations into exchange rates, but unexpected inflation, which, when extreme, can cause significant revaluations of currencies.

Conclusion As with any historical data assessment, I could give you the standard boilerplate disclaimer that past performance is not always a good predictor of the past, but to the extent that the past provides signals, your expectations of how inflation will play out in the coming year will play a key role in your asset allocation and stock selection decisions. If you believe that last year's surge in inflation is a precursor to a long time period when inflation is likely to stay high, and come in above expectations, you should be shifting your holdings away from financial to real assets, and within your equity holdings, towards small cap stocks, stocks trading at lower pricing multiples (PE, Price to Book) and companies with more pricing power. If, on the other hand, you believe that inflation worries are overdone, and that there will be a reversion back to the low inflation that we have seen in the last decade, staying invested in stocks, and especially in larger cap and high growth stocks, even if richly priced, makes sense.

YouTube Video

Data LinksInflation Data: CPI, PPI and GDP DeflatorIntrinsic versus Actual T.Bond Rates: 1954-2021Inflation and Returns on Asset ClassesRiskfree Rates in Currencies (Government Bond based estimates)Blog Post LinksInflation and Investing: False Alarm or Fair Warning?The Fed, Interest Rates and Stock Prices: Fighting the Fear Factor

January 19, 2022

Data Update 2 for 2022: US Stocks kept winning in 2021, but���

Leading into 2021, the big questions facing investors were about how quickly economies would recover from COVID, with the assumption that the virus would fade during the year, and the pressures that the resulting growth would put on inflation. In a post at the start of 2021, I argued that while stocks entered the year at elevated levels, especially on historic metrics (such as PE ratios), they were priced to deliver reasonable returns, relative to very low risk free rates (with the treasury bond rate at 0.93% at the start of 2021). At the start of 2022, it feels like Groundhog Day, with the same questions about economic growth and inflation looming for the year, and the same judgment about stocks, i.e., that they look expensive. In this post, I will begin with a historical assessment of stock returns in the recent past, then move on to evaluate the returns that investors can expect to make, given how they are priced at the start of 2022, and end with a do-it-yourself valuation of the index right now.

The year that was....

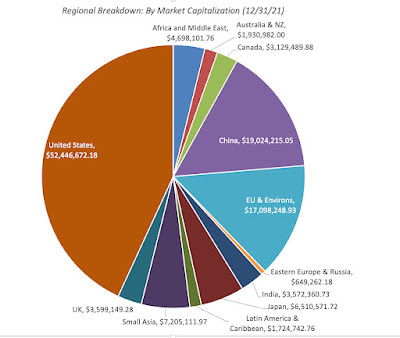

If equity markets surprised us with their resilience in 2020, not just weathering a pandemic for the ages, but prospering in its midst, US equity markets, in particular, managed to find light even in the darkest news stories, and continued their rise through 2021. Foreign markets, though, had a mixed year, and that divergence is worth noting, since it may provide clues to what may be coming in the next year.

US Equities, in the aggregate

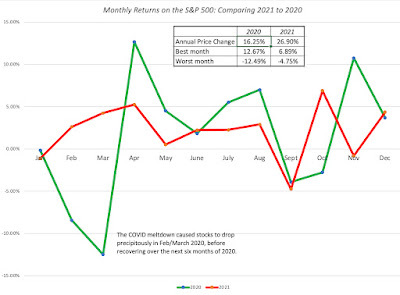

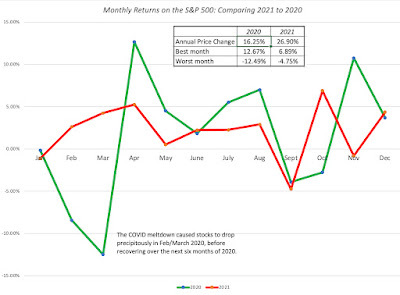

US equities had a good year, by any measure, with the S&P 500 rising from 3756 at the start of 2021 to end the year at 4766, an increase of 26.90%. While that followed another good year for stocks in 2020, with the index rising 16.25%, from 3231 to 3756, the index took different pathways during the two years:

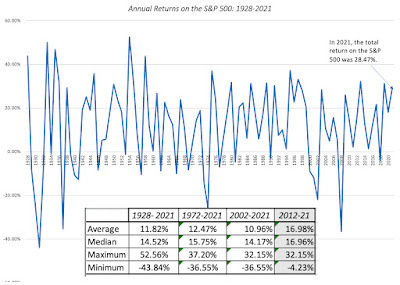

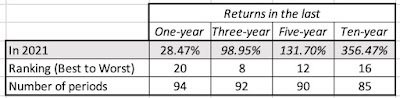

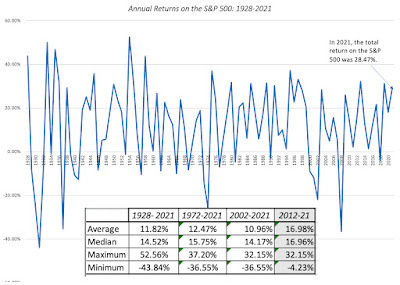

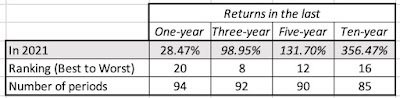

In 2020, the market was up, but only after it absorbed the after-shocks of the inception of the virus in February and March of 2020. In 2021, the index had a smoother ride, up in nine of twelve months, with only September qualifying a significant drop (with the index down 4.75%). When you augment this price change with the dividends on the index during 2021, the total return on the S&P 500 for 2021 was 28.47%. I report a dataset containing annual returns on stocks, going back to 1928, and to put 2021 in context, I looked at the historical returns on the index:

Download historical returns on US stocks

Download historical returns on US stocksLooking at the 94 years in this dataset, the returns in 2021 would have ranked 20th on the list, good, but not exceptional. Note, though, that 2021 is the third consecutive year of very good returns on the index, with 2019 delivering 31.21%, and 2020 generating 18.02%, and that the cumulative return over the three years (2019-21) is 98.95%. If you compute cumulative returns, on a rolling three-year time period (1928-30, 1929-31, 1930-32 etc.), the 2019-21 time period would rank 8th on the list of 92 3-year time periods. The table below provides the rankings for returns over 5-year and 10-year periods, and where the most recent three-year, five-year and ten-year cumulative returns would rank on the list:

Download return rankings

Download return rankings

In sum, if you have money to invest over the last decade, and you stayed invested, you should count yourself as lucky to have enjoyed one of the great market runs of the last century. Conversely, if you stayed out of the market, for the last decade, you would have committed one of the great investing mistakes of all time, and blaming the Fed or bubble-talk will not bring you absolution.

US Equities, by sub-group

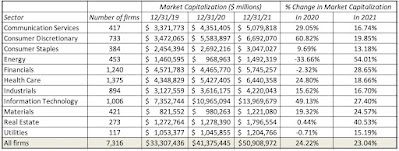

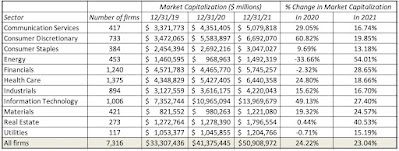

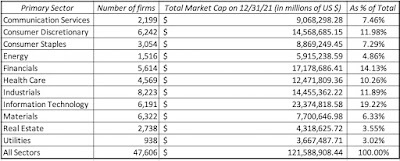

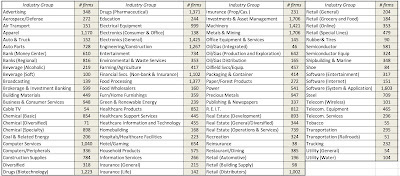

It has always true that when markets move, up or down, not all sectors and sub-groups are treated equally. I do believe that too much is often made of these differences, as it is generally more the rule than the exception that markets, when they are up strongly, get the bulk of that rise from a small sub-set of stocks or sectors. Using S&P's sector classification, I take a look at how each one did in 2022, looking at the percent changes in market capitalization:

In contrast to 2020, when technology and consumer discretionary firms ran well ahead of the pack, the best performing sectors in 2021 were energy and real estate, two of the biggest laggards in 2020. That can be viewed as vindication, at least in this year, for contrarians, but as a cautionary note for ESG advocates, who assumed that fossil fuel companies were on a death march, based upon their performance over the last decade.

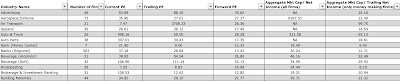

There is no debate more likely to draw heat than the value versus growth debate, and at the risk of being labeled simplistic by value investors, I looked at returns on companies, in 2021, based upon their PE ratios at the start of 2021:

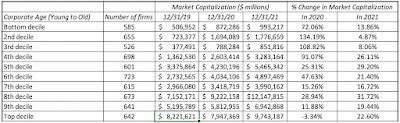

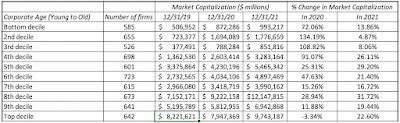

Unlike 2020, where high PE stocks beat low PE stocks decisively, the results in 2021 were mixed, with no clear patterns across the classes. The results are similar if you break stocks down based upon price to book ratios or revenue growth rates. Finally, and in keeping with my fixation on corporate age and life cycles, I broke companies down by company age (measured from the founding year):

Again, unlike 2020, when young companies delivered significantly higher returns than older companies, the best returns in 2021 were delivered by middle aged companies.

For the rest of the world

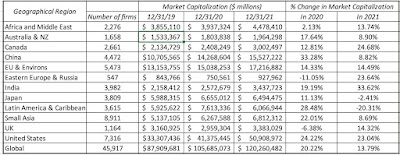

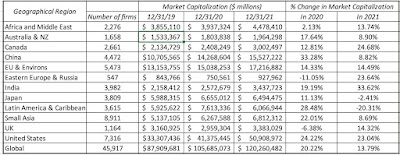

While US equities continued to set new highs in 2021, the picture in the rest of the world was not as rosy, as you can see in the table below (with percent returns in US dollar terms):

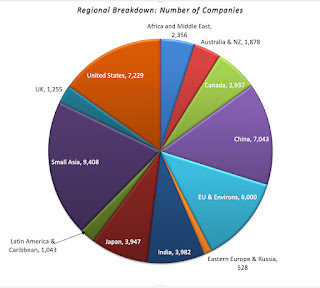

In US dollar terms, India had the best-performing market in 2021, following a strong 2020, but China, the best performer in the world in 2020 came back to earth in 2021. North America (US and Canada) outperformed the globe, but Latin America was the worst performing region, down more than 20% in US dollar terms. There are many reasons why markets diverge, but here again the contrast with 2020 is worth drawing. In 2020, the COVID crisis played out across markets, increasing the co-movement and correlation across developed markets, with the US, Europe and Japan moving mostly in sync. In 2021, you saw a return to more normal times, with markets in each country affected more by local factors.

The Price of Risk in Equity Markets

The allure of having the historical data that we do in financial markets, especially in the United States, is that there is information in the past. The danger of poring over this historical data is that a focus on the past can blind us to structural changes in markets that can make the future very different from the past. To get a measure of what equity markets are offering in terms of expected returns, we are better served with a forward-looking and dynamic measure of these returns, and that is the focus of this section.

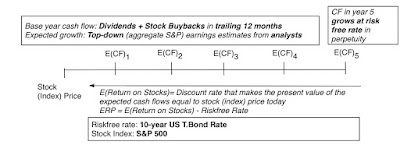

Implied Equity Risk Premiums

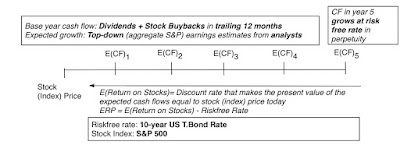

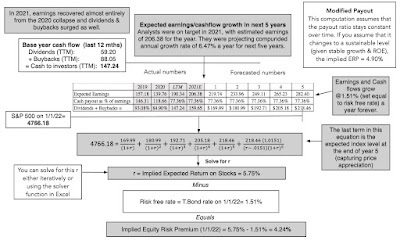

To understand the intuition behind the implied equity risk premium, it is easiest to start with the concept of a yield to maturity on a bond, computed as the discount rate that makes the present value of the cash flows on the bond (coupons, during the bond's lifetime, and face value, at maturity) equal to the price of the bond. With equities, the cash flows take the form of dividends and buybacks, and in addition to estimating them using future growth rates, you have to assume that they continue in perpetuity. In computing this implied equity risk premium for the S&P 500, I start with the dividends and buybacks on the stocks in the index in the most recent year (which is known) and assume that they grow at the rate that analysts who follow the index are projecting for the next five years. Beyond the fifth year, I make the simplifying assumption that earnings growth will converge on the nominal growth rate of the economy, which I set equal to the risk free rate.

If you set the present value of the expected cash flows equal to the index level today, and solve for a discount rate (you may need to use the solver function in Excel, or trial and error), the resulting number is the expected return on stocks, based upon how stocks are priced today, and expected cash flows. This approach is built on the proposition that the intrinsic value of stocks is the present value of the expected cash flows that you generate in perpetuity, from holding these stocks, but it is model agnostic. Put simply, it does not require that you believe in any risk and return model in finance, since it is based on price and expected cash flows. To the critique that analysts can over estimate future earnings and growth, the response is that even if they do (and there is no evidence that top-down forecasts are biased), it is the price of risk, given expected cash flows.

If you set the present value of the expected cash flows equal to the index level today, and solve for a discount rate (you may need to use the solver function in Excel, or trial and error), the resulting number is the expected return on stocks, based upon how stocks are priced today, and expected cash flows. This approach is built on the proposition that the intrinsic value of stocks is the present value of the expected cash flows that you generate in perpetuity, from holding these stocks, but it is model agnostic. Put simply, it does not require that you believe in any risk and return model in finance, since it is based on price and expected cash flows. To the critique that analysts can over estimate future earnings and growth, the response is that even if they do (and there is no evidence that top-down forecasts are biased), it is the price of risk, given expected cash flows.The Implied ERP - Start of 2022

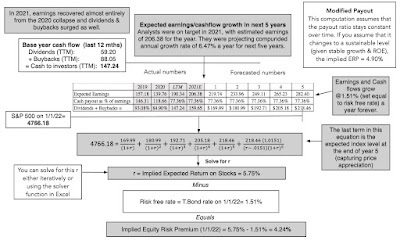

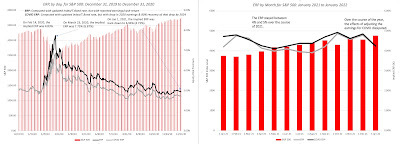

I have computed the implied equity risk premium at the start of every month, since September 2008, and during crisis periods, I compute it every day. Over the course of 2021, as the index rose, risk free rates climbed and analysts got much more upbeat about expected earnings for the next three years, the equity risk premium drifted down, to end the year at 4.24%:

Download spreadsheet

Download spreadsheet

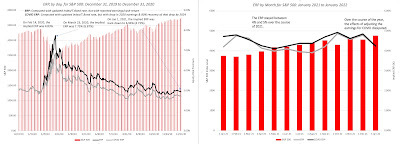

Much as I would love to claim that I have the estimated the equity risk premium to the second decimal point, the truth is that there is some give in these numbers and that changing assumptions about earnings and cash flows generates an equity risk premium between 4-5%. The contrast between the behavior f equity risk premiums in 2020 and 2021 are in the picture below, where I show my (daily) estimates of ERP during 2020 on the left, and my (monthly) estimates of ERP for 2021 on the right.

Download data on ERP by month from 2008-2021

Download data on ERP by month from 2008-2021

During 2020, the equity risk started the year at about 4.7%, spiraled to almost 8% on March 23, 2020, before reverting back quickly to pre-crisis levels by September 2020. During 2021, you saw equity risk premiums revert back to a more sedate path, with numbers staying between 4% and 5% through the course of the entire year.

Historical Perspective

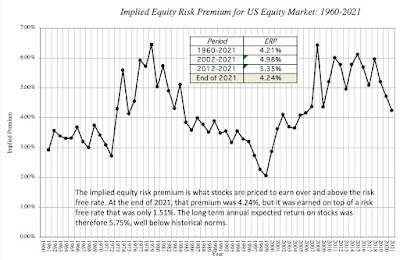

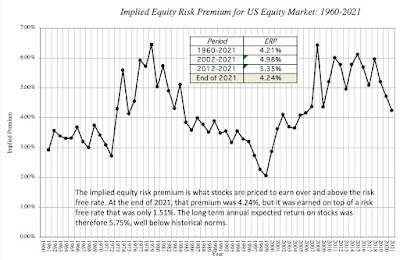

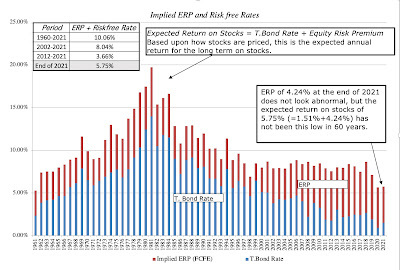

As talk of a bubble fills the air, one way to reframe the question of whether stocks are in bubble territory is to ask whether the current implied equity risk premium has become ���too low���. If your answer is yes, you are arguing that stocks are over priced, and if the answer is no, that they are under priced. At least on the surface, the current level of the equity risk premium is not flashing red lights, since at 4.24%, it is running slightly above the long term averages of 4.21% (1960 - 2021).

Download past implied ERP

Download past implied ERP

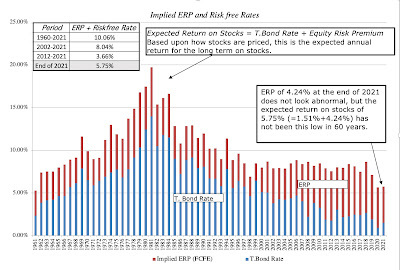

That said, there are two reasons for concern. The first is that the premium is now lower than the average premium since 2008, a period that perhaps better reflects the new global economy. The second and scarier reason is that the 5.75% expected return that is implied in today���s stock prices is close to a sixty-year low:

Download past implied ERP

Download past implied ERP

A pessimist looking at this graph will conclude that expected returns on stocks have become too low, and that we are due for a correction, but that would be more a statement about treasury bond rates being too low than about equity risk premiums. Even if you belong to the camp arguing that low risk free rates are now the norm, this graph suggests that we all need to re-examine how much we, as individuals, are saving for retirement, since the old presumption that you can earn 8-10% investing in stocks will longer hold. Across the United States, defined-benefit pension funds that have set aside funds on this same assumption will face massive funding shortfalls, unless they reevaluate benefit levels or infuse new funds.

A Market Assessment

If you look at history, it seems difficult to argue against the notion that market timing is the impossible dream, but that has never stopped investors from trying to time markets, partly because the payoff from being right is immense. I have long claimed that I am not a market timer, but that is a lie, since every investor times markets, with the difference being in whether the timing is implicit (with cash holdings in your portfolio increasing, when you feel uneasy about markets, and decreasing, when you feel bullish) or explicit (where you actively bet on market direction). Rather than just give you just my estimate of whether I think the market is under or over valued, I will ask each of you to make your own judgments, while also offering my own.

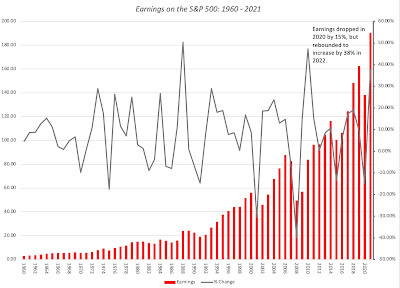

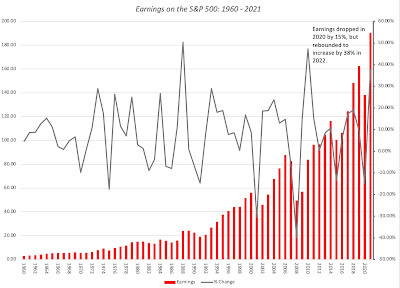

The process of valuing the index starts with an assessment of expected earnings, and with the S&P 500, there is no shortage of either historical data or assessments of the future, on this dimension. Let's start with a look at S&P earnings over time:

Download historical earnings

Download historical earnings

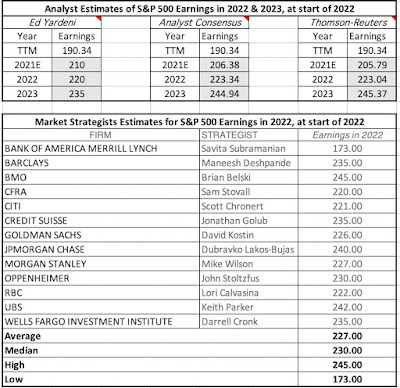

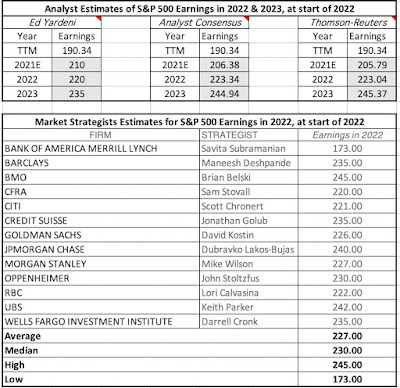

While COVID wreaked havoc with corporate earnings in 2020, the comeback in earnings in 2021 has been remarkable, with trailing 12-month earnings (October 2020 - September 2021) at 190.34, and estimated earnings for 2021 of 206.38, both significantly higher than the 162.35 that was earned in 2019 (pre-COVID). At the end of 2021, analyst estimates for earnings in 2022 and 2023 reflect their views that the earnings recovery will continue:

I will use the analyst estimates as my expected earnings for the index for the next two years, but assume that earnings growth rate thereafter will move down over the following three years to a stable growth rate (set equal to the risk free rate). It is true that analysts are often wrong, and in some cases, biased, but the latter is more of a problem with analyst estimates for individual companies, than for market aggregate earnings. However, if you believe that analysts have overestimated earnings, my valuation spreadsheet gives you the option of haircutting those estimates. Conversely, if your contention is that analysts are still playing catch-up, you can increase their estimates by a factor of your choosing.

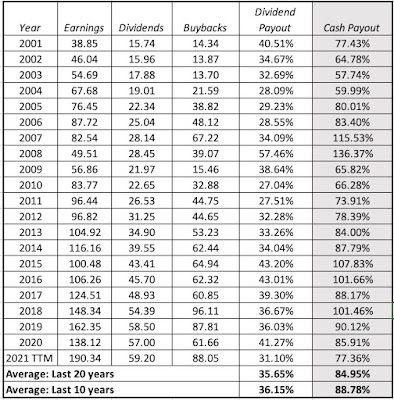

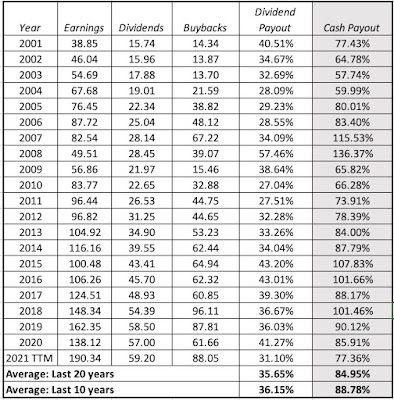

I will use the analyst estimates as my expected earnings for the index for the next two years, but assume that earnings growth rate thereafter will move down over the following three years to a stable growth rate (set equal to the risk free rate). It is true that analysts are often wrong, and in some cases, biased, but the latter is more of a problem with analyst estimates for individual companies, than for market aggregate earnings. However, if you believe that analysts have overestimated earnings, my valuation spreadsheet gives you the option of haircutting those estimates. Conversely, if your contention is that analysts are still playing catch-up, you can increase their estimates by a factor of your choosing.Investors don't get value from earnings directly, but do get value from the cash flows flowing from those earnings. As I have noted in prior posts, these cash flows, which used to entirely take the form of dividends, have increasingly shifted, over the last three decades, to stock buybacks.

While dividends are stickier than buybacks, insofar as companies are more willing to reduce the latter during crisis years like 2009 and 2020, it is also clear, as the comeback in buybacks in 2021 shows. In my base case valuation, I will start with 77.36%, the percent of earnings that companies have returned to shareholders, in dividends and buybacks, in the last twelve months, but I will increase this over time to a cash payout ratio that is consistent with my estimate of stable growth (risk free rate) and the return on equity of 16.10% that S&P 500 companies have earned, on average, over the last decade. (Sustainable Payout Ratio = 1 - g/ ROE; with a 16.10% return on equity and a 2.5% growth rate, the payout ratio in stable growth is 84.47%= 1 - .025/.161).

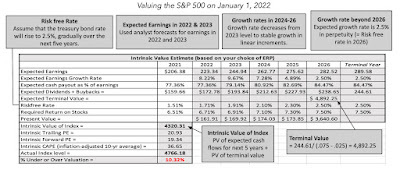

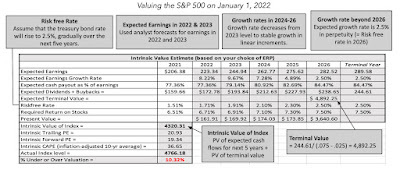

While dividends are stickier than buybacks, insofar as companies are more willing to reduce the latter during crisis years like 2009 and 2020, it is also clear, as the comeback in buybacks in 2021 shows. In my base case valuation, I will start with 77.36%, the percent of earnings that companies have returned to shareholders, in dividends and buybacks, in the last twelve months, but I will increase this over time to a cash payout ratio that is consistent with my estimate of stable growth (risk free rate) and the return on equity of 16.10% that S&P 500 companies have earned, on average, over the last decade. (Sustainable Payout Ratio = 1 - g/ ROE; with a 16.10% return on equity and a 2.5% growth rate, the payout ratio in stable growth is 84.47%= 1 - .025/.161).On the risk free rate, I start with 1.51%, the 10-year treasury bond rate on January 1, 2022, but I will assume that this rate will drift upwards over the next five years to reach 2.5%. That reflects my view that inflation pressures will push up long term rates in the year to come and has little to do with what the Fed may or may not do with the Fed funds rate. Finally, I build in the expectation that a fair ERP for the S&P 500 should be 5%, higher than the long term historical average of 4.21%, but closer to the average ERP since 2008. On both these macro assumptions, I encourage you to take your own point of view. With these assumptions in place, my valuation for the S&P 500, as of January 1, 2022, is shown below:

Download spreadsheet to value S&P 500 index

Download spreadsheet to value S&P 500 index

Note that even in the two weeks since I did this valuation, there have been material changes in key inputs, with the treasury bond rate rising to 1.87% on January 19, 2022, and the S&P dropping to 4533, down 3.8% from its level at the start of the year.

In Conclusion

As with any valuation, I don't believe that I should try to convince you that my valuation is the right one, nor do I have no desire to do so. In fact, I know that my valuation is wrong, with the question being in what direction, and by how much. I would strongly encourage you to take my valuation spreadsheet, change the numbers that I have used on earnings, cash flows, the risk free rate and the equity risk premium to reflect your views, and come up with your own assessment of value. Good investing requires taking ownership of your investment decisions, and trusting this choice to talking heads on TV, market strategists at investment banks or those market gurus who looked good last year is a dereliction of investment duty.

YouTube Video

Datasets (to download)

Historical returns on stocks, bonds, bills and real estate: 1928 - 2021Historical implied ERP on the S&P 500: 1960 -2021Spreadsheet (to value the S&P 500)

Spreadsheet to compute implied ERP on January 1, 2022Spreadsheet to value the S&P 500 on January 1, 2022

Data Update 2 for 2022: US Stocks kept winning in 2021, but…

Leading into 2021, the big questions facing investors were about how quickly economies would recover from COVID, with the assumption that the virus would fade during the year, and the pressures that the resulting growth would put on inflation. In a post at the start of 2021, I argued that while stocks entered the year at elevated levels, especially on historic metrics (such as PE ratios), they were priced to deliver reasonable returns, relative to very low risk free rates (with the treasury bond rate at 0.93% at the start of 2021). At the start of 2022, it feels like Groundhog Day, with the same questions about economic growth and inflation looming for the year, and the same judgment about stocks, i.e., that they look expensive. In this post, I will begin with a historical assessment of stock returns in the recent past, then move on to evaluate the returns that investors can expect to make, given how they are priced at the start of 2022, and end with a do-it-yourself valuation of the index right now.

The year that was....

If equity markets surprised us with their resilience in 2020, not just weathering a pandemic for the ages, but prospering in its midst, US equity markets, in particular, managed to find light even in the darkest news stories, and continued their rise through 2021. Foreign markets, though, had a mixed year, and that divergence is worth noting, since it may provide clues to what may be coming in the next year.

US Equities, in the aggregate

US equities had a good year, by any measure, with the S&P 500 rising from 3756 at the start of 2021 to end the year at 4766, an increase of 26.90%. While that followed another good year for stocks in 2020, with the index rising 16.25%, from 3231 to 3756, the index took different pathways during the two years:

In 2020, the market was up, but only after it absorbed the after-shocks of the inception of the virus in February and March of 2020. In 2021, the index had a smoother ride, up in nine of twelve months, with only September qualifying a significant drop (with the index down 4.75%). When you augment this price change with the dividends on the index during 2021, the total return on the S&P 500 for 2021 was 28.47%. I report a dataset containing annual returns on stocks, going back to 1928, and to put 2021 in context, I looked at the historical returns on the index:

Download historical returns on US stocks

Download historical returns on US stocksLooking at the 94 years in this dataset, the returns in 2021 would have ranked 20th on the list, good, but not exceptional. Note, though, that 2021 is the third consecutive year of very good returns on the index, with 2019 delivering 31.21%, and 2020 generating 18.02%, and that the cumulative return over the three years (2019-21) is 98.95%. If you compute cumulative returns, on a rolling three-year time period (1928-30, 1929-31, 1930-32 etc.), the 2019-21 time period would rank 8th on the list of 92 3-year time periods. The table below provides the rankings for returns over 5-year and 10-year periods, and where the most recent three-year, five-year and ten-year cumulative returns would rank on the list:

Download return rankings

Download return rankings

In sum, if you have money to invest over the last decade, and you stayed invested, you should count yourself as lucky to have enjoyed one of the great market runs of the last century. Conversely, if you stayed out of the market, for the last decade, you would have committed one of the great investing mistakes of all time, and blaming the Fed or bubble-talk will not bring you absolution.

US Equities, by sub-group

It has always true that when markets move, up or down, not all sectors and sub-groups are treated equally. I do believe that too much is often made of these differences, as it is generally more the rule than the exception that markets, when they are up strongly, get the bulk of that rise from a small sub-set of stocks or sectors. Using S&P's sector classification, I take a look at how each one did in 2022, looking at the percent changes in market capitalization:

In contrast to 2020, when technology and consumer discretionary firms ran well ahead of the pack, the best performing sectors in 2021 were energy and real estate, two of the biggest laggards in 2020. That can be viewed as vindication, at least in this year, for contrarians, but as a cautionary note for ESG advocates, who assumed that fossil fuel companies were on a death march, based upon their performance over the last decade.

There is no debate more likely to draw heat than the value versus growth debate, and at the risk of being labeled simplistic by value investors, I looked at returns on companies, in 2021, based upon their PE ratios at the start of 2021:

Unlike 2020, where high PE stocks beat low PE stocks decisively, the results in 2021 were mixed, with no clear patterns across the classes. The results are similar if you break stocks down based upon price to book ratios or revenue growth rates. Finally, and in keeping with my fixation on corporate age and life cycles, I broke companies down by company age (measured from the founding year):

Again, unlike 2020, when young companies delivered significantly higher returns than older companies, the best returns in 2021 were delivered by middle aged companies.

For the rest of the world

While US equities continued to set new highs in 2021, the picture in the rest of the world was not as rosy, as you can see in the table below (with percent returns in US dollar terms):

In US dollar terms, India had the best-performing market in 2021, following a strong 2020, but China, the best performer in the world in 2020 came back to earth in 2021. North America (US and Canada) outperformed the globe, but Latin America was the worst performing region, down more than 20% in US dollar terms. There are many reasons why markets diverge, but here again the contrast with 2020 is worth drawing. In 2020, the COVID crisis played out across markets, increasing the co-movement and correlation across developed markets, with the US, Europe and Japan moving mostly in sync. In 2021, you saw a return to more normal times, with markets in each country affected more by local factors.

The Price of Risk in Equity Markets

The allure of having the historical data that we do in financial markets, especially in the United States, is that there is information in the past. The danger of poring over this historical data is that a focus on the past can blind us to structural changes in markets that can make the future very different from the past. To get a measure of what equity markets are offering in terms of expected returns, we are better served with a forward-looking and dynamic measure of these returns, and that is the focus of this section.

Implied Equity Risk Premiums

To understand the intuition behind the implied equity risk premium, it is easiest to start with the concept of a yield to maturity on a bond, computed as the discount rate that makes the present value of the cash flows on the bond (coupons, during the bond's lifetime, and face value, at maturity) equal to the price of the bond. With equities, the cash flows take the form of dividends and buybacks, and in addition to estimating them using future growth rates, you have to assume that they continue in perpetuity. In computing this implied equity risk premium for the S&P 500, I start with the dividends and buybacks on the stocks in the index in the most recent year (which is known) and assume that they grow at the rate that analysts who follow the index are projecting for the next five years. Beyond the fifth year, I make the simplifying assumption that earnings growth will converge on the nominal growth rate of the economy, which I set equal to the risk free rate.

If you set the present value of the expected cash flows equal to the index level today, and solve for a discount rate (you may need to use the solver function in Excel, or trial and error), the resulting number is the expected return on stocks, based upon how stocks are priced today, and expected cash flows. This approach is built on the proposition that the intrinsic value of stocks is the present value of the expected cash flows that you generate in perpetuity, from holding these stocks, but it is model agnostic. Put simply, it does not require that you believe in any risk and return model in finance, since it is based on price and expected cash flows. To the critique that analysts can over estimate future earnings and growth, the response is that even if they do (and there is no evidence that top-down forecasts are biased), it is the price of risk, given expected cash flows.

If you set the present value of the expected cash flows equal to the index level today, and solve for a discount rate (you may need to use the solver function in Excel, or trial and error), the resulting number is the expected return on stocks, based upon how stocks are priced today, and expected cash flows. This approach is built on the proposition that the intrinsic value of stocks is the present value of the expected cash flows that you generate in perpetuity, from holding these stocks, but it is model agnostic. Put simply, it does not require that you believe in any risk and return model in finance, since it is based on price and expected cash flows. To the critique that analysts can over estimate future earnings and growth, the response is that even if they do (and there is no evidence that top-down forecasts are biased), it is the price of risk, given expected cash flows.The Implied ERP - Start of 2022

I have computed the implied equity risk premium at the start of every month, since September 2008, and during crisis periods, I compute it every day. Over the course of 2021, as the index rose, risk free rates climbed and analysts got much more upbeat about expected earnings for the next three years, the equity risk premium drifted down, to end the year at 4.24%:

Download spreadsheet

Download spreadsheet

Much as I would love to claim that I have the estimated the equity risk premium to the second decimal point, the truth is that there is some give in these numbers and that changing assumptions about earnings and cash flows generates an equity risk premium between 4-5%. The contrast between the behavior f equity risk premiums in 2020 and 2021 are in the picture below, where I show my (daily) estimates of ERP during 2020 on the left, and my (monthly) estimates of ERP for 2021 on the right.

Download data on ERP by month from 2008-2021

Download data on ERP by month from 2008-2021

During 2020, the equity risk started the year at about 4.7%, spiraled to almost 8% on March 23, 2020, before reverting back quickly to pre-crisis levels by September 2020. During 2021, you saw equity risk premiums revert back to a more sedate path, with numbers staying between 4% and 5% through the course of the entire year.

Historical Perspective

As talk of a bubble fills the air, one way to reframe the question of whether stocks are in bubble territory is to ask whether the current implied equity risk premium has become “too low”. If your answer is yes, you are arguing that stocks are over priced, and if the answer is no, that they are under priced. At least on the surface, the current level of the equity risk premium is not flashing red lights, since at 4.24%, it is running slightly above the long term averages of 4.21% (1960 - 2021).

Download past implied ERP

Download past implied ERP

That said, there are two reasons for concern. The first is that the premium is now lower than the average premium since 2008, a period that perhaps better reflects the new global economy. The second and scarier reason is that the 5.75% expected return that is implied in today’s stock prices is close to a sixty-year low:

Download past implied ERP

Download past implied ERP

A pessimist looking at this graph will conclude that expected returns on stocks have become too low, and that we are due for a correction, but that would be more a statement about treasury bond rates being too low than about equity risk premiums. Even if you belong to the camp arguing that low risk free rates are now the norm, this graph suggests that we all need to re-examine how much we, as individuals, are saving for retirement, since the old presumption that you can earn 8-10% investing in stocks will longer hold. Across the United States, defined-benefit pension funds that have set aside funds on this same assumption will face massive funding shortfalls, unless they reevaluate benefit levels or infuse new funds.

A Market Assessment

If you look at history, it seems difficult to argue against the notion that market timing is the impossible dream, but that has never stopped investors from trying to time markets, partly because the payoff from being right is immense. I have long claimed that I am not a market timer, but that is a lie, since every investor times markets, with the difference being in whether the timing is implicit (with cash holdings in your portfolio increasing, when you feel uneasy about markets, and decreasing, when you feel bullish) or explicit (where you actively bet on market direction). Rather than just give you just my estimate of whether I think the market is under or over valued, I will ask each of you to make your own judgments, while also offering my own.

The process of valuing the index starts with an assessment of expected earnings, and with the S&P 500, there is no shortage of either historical data or assessments of the future, on this dimension. Let's start with a look at S&P earnings over time:

Download historical earnings

Download historical earnings

While COVID wreaked havoc with corporate earnings in 2020, the comeback in earnings in 2021 has been remarkable, with trailing 12-month earnings (October 2020 - September 2021) at 190.34, and estimated earnings for 2021 of 206.38, both significantly higher than the 162.35 that was earned in 2019 (pre-COVID). At the end of 2021, analyst estimates for earnings in 2022 and 2023 reflect their views that the earnings recovery will continue:

I will use the analyst estimates as my expected earnings for the index for the next two years, but assume that earnings growth rate thereafter will move down over the following three years to a stable growth rate (set equal to the risk free rate). It is true that analysts are often wrong, and in some cases, biased, but the latter is more of a problem with analyst estimates for individual companies, than for market aggregate earnings. However, if you believe that analysts have overestimated earnings, my valuation spreadsheet gives you the option of haircutting those estimates. Conversely, if your contention is that analysts are still playing catch-up, you can increase their estimates by a factor of your choosing.

I will use the analyst estimates as my expected earnings for the index for the next two years, but assume that earnings growth rate thereafter will move down over the following three years to a stable growth rate (set equal to the risk free rate). It is true that analysts are often wrong, and in some cases, biased, but the latter is more of a problem with analyst estimates for individual companies, than for market aggregate earnings. However, if you believe that analysts have overestimated earnings, my valuation spreadsheet gives you the option of haircutting those estimates. Conversely, if your contention is that analysts are still playing catch-up, you can increase their estimates by a factor of your choosing.Investors don't get value from earnings directly, but do get value from the cash flows flowing from those earnings. As I have noted in prior posts, these cash flows, which used to entirely take the form of dividends, have increasingly shifted, over the last three decades, to stock buybacks.

While dividends are stickier than buybacks, insofar as companies are more willing to reduce the latter during crisis years like 2009 and 2020, it is also clear, as the comeback in buybacks in 2021 shows. In my base case valuation, I will start with 77.36%, the percent of earnings that companies have returned to shareholders, in dividends and buybacks, in the last twelve months, but I will increase this over time to a cash payout ratio that is consistent with my estimate of stable growth (risk free rate) and the return on equity of 16.10% that S&P 500 companies have earned, on average, over the last decade. (Sustainable Payout Ratio = 1 - g/ ROE; with a 16.10% return on equity and a 2.5% growth rate, the payout ratio in stable growth is 84.47%= 1 - .025/.161).