Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 7

January 26, 2023

Tesla in 2023: A Return to Reality, The Start of the End or Time to Buy?

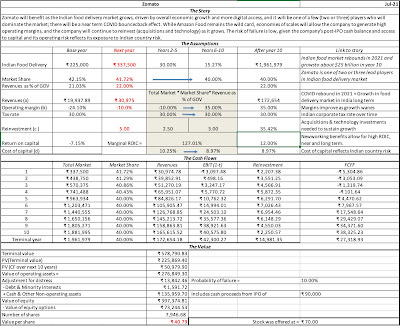

I am not much of a car person and view cars primarily as a mode of transportation. I drive a 2010 Honda Civic, a perfectly serviceable vehicle that is never going to get oohs and ahas from onlookers, but I feel no urge to value Honda. I don't own a Tesla, and have only driven someone else's Tesla, but as readers of this blog know, I valued Tesla for the first time in 2014, and I keep returning to the scene of the crime. One reason is that no matter what you think of Elon Musk and Tesla, they are never boring, and interesting companies are much more fun to value than boring ones. Another is that when valuing companies, I am, in addition to valuing a company to see if it is fairly priced, interested into the broader insights about business and valuation that emerge from the company. Thus, almost everything I know and practice, when valuing young and start-up companies, I learned in the process of valuing Amazon in the 1990s. In the same vein, I have learned a great about the power of disruption and the capacity of a young company (and its founder) to change the way a large, inertia-bound business is run, in the process of valuing Tesla. As I will note in more detail in the post, I have been wrong, and sometimes hopelessly so, in some of my earlier valuations of Tesla, but that does not stop me from trying anew. It is also true that Tesla is a company that attracts strong and very divergent views, and consequently, I get more pushback on my valuations of Tesla than on any other company, but as in last few attempts with this company, I have structured my valuation to allow you to incorporate your disagreement. My last valuation of Tesla was in November 2021, towards its market peak, and given its steep fall from grace, in conjunction with Elon Musk's Twitter experiment, it is time for a revisit.

Tesla: A Revolution Unfolds

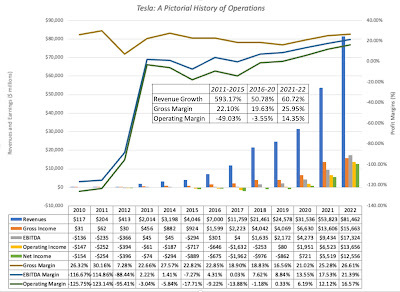

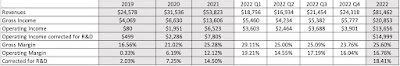

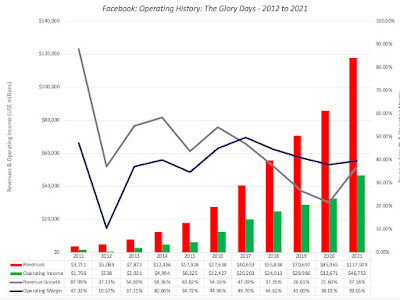

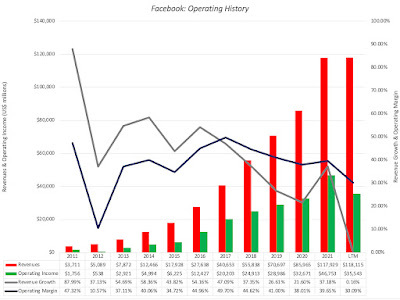

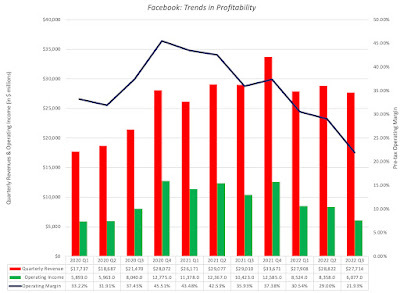

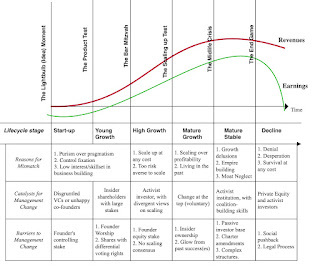

In evaluating Tesla's climb to domination, at least in market value terms, of the automobile business, it is worth remembering how impervious this business was to disruption in the decades leading up to Tesla's arrival. In the United States and Europe, domestic competitors to the established players did not get far, largely brought down by requirements of large capital investments and a distribution system built to favor established players. When Tesla was founded in 2006, with a stated intent of building electric cars, the traditional auto companies were quick to dismiss it as a potential competitor. Tesla's rise is summarized in the graph below, where we look at the company's revenues and earnings over time, with earnings measured in gross and operating terms, and EBITDA capturing operating cash flows:

2022 numbers updated to reflect 4th quarter earnings call on 1/25/23

2022 numbers updated to reflect 4th quarter earnings call on 1/25/23Between 2010 and 2020, Tesla grew revenues from $117 million to $31.5 billion, a remarkable achievement by itself, but COVID gave the company a boost, as revenue have increased about 250% in the 2020-22 time-period. Just as impressively, the company finally started delivering on its promise of profitability, going from barely making money in 2019 to an operating margin of 16.57% in 2022. While the company still has skeptics, it is no longer a niche player in a big market, and has moved the sector closer to its vision than the other way around.

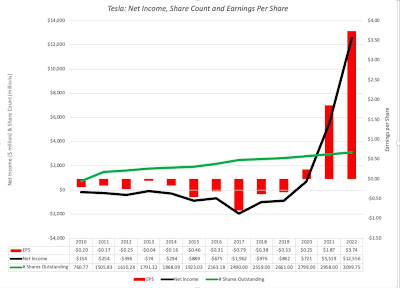

In its early years, Tesla was dependent on equity issuances for funding growth investments, and its liberal use of options to reward management (and especially Elon Musk) opened it up to criticism. Since both affect share count, I look at the company's net income and earnings per share over its public life:

2022 numbers updated to reflect 4th quarter earnings call on 1/25/23

2022 numbers updated to reflect 4th quarter earnings call on 1/25/23It is true that the number of shares outstanding has quadrupled over the company's lifetime, but the good news is that the net income increases in recent years have outstripped the share count increase, with earnings per share increasing from 25 cents per share in 2020 to $3.74 per share in 2022.

My Tesla History

I have valued Tesla multiple times over the last decade, and while I have been wrong at each turn, I have tried to learn from my mistakes. In this section, I will begin by looking at the evolution of my Tesla value from 2013 to 2021, and then present my updated valuation of the company.

My Tesla Valuations over Time

My first valuation of Tesla was in 2013, and I found the company significantly overvalued then, and in hindsight, there were three errors that I made in that valuation that I systematically found myself repeating in my early valuations.

With the 3:1 stock split since, his value per share has to be divided by three to make it comparable to today's priceI argued that I could see almost no plausible pathway to get to Tesla's market cap then and that I believed that the company was over valued.

With the 3:1 stock split since, his value per share has to be divided by three to make it comparable to today's priceI argued that I could see almost no plausible pathway to get to Tesla's market cap then and that I believed that the company was over valued.A Valuation Update

It is a year and two months since my last valuation of Tesla, and it has been an eventful period for the company, Elon Musk, its founder/CEO and the overall market:

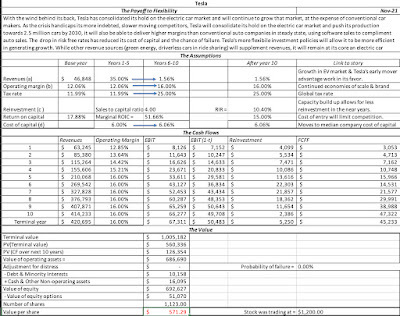

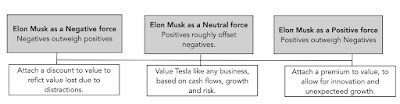

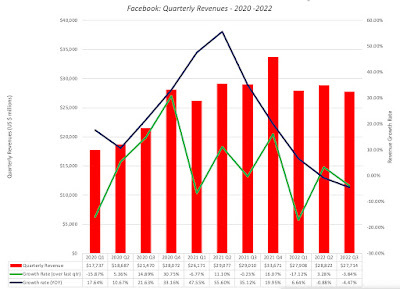

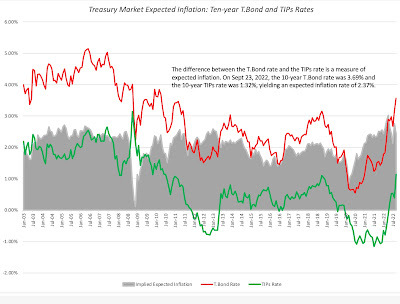

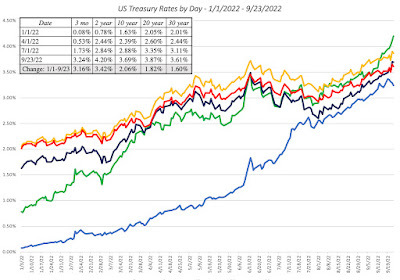

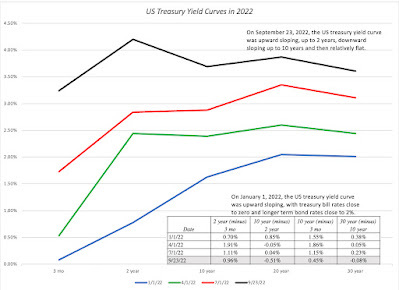

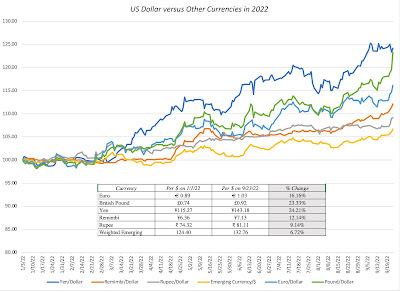

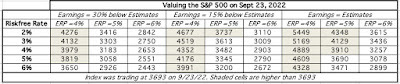

Until recently, even Tesla critics would have conceded that Musk, in spite of his numerous faults, was a net positive to the company. In the last year, even Tesla advocates have starting questioning that belief, partly because Musk's Twitter adventures seem to be taking up much of his time, leaving a perceived vacuum at the helm of the company. That may be an overreaction, and I am not quite ready to come to the conclusion that he is net negative for the company, but it is undeniable that the net Musk effect being negative is not being dismissed. There is also the question of whether Musk will come under pressure to sell Tesla shares to meet demands from Twitter lenders, and how that will play out in markets.The Market: The US equity market in January 2023 looks very different from the market at the start of 2022. As I noted in my last post, rising risk free rates and equity risk premiums have pushed up the costs of equity for all companies, and Tesla is not only no exception but is perhaps even more exposed as an above-average risk company. In short, the cost of capital of 6% that I used in November 2021, higher than the median cost of capital of 5.6% for US companies then, no longer is defensible, as the median cost of capital has climbed toward 9.6%.With these changes in mind, I revisited my valuation of Tesla from November 2021 and made the following changes: First, I left my end revenues for Tesla back to $400 billion, still a reflection of my view that electric cars will become the dominant part of the auto market, and that Tesla still has not only a lead in that market, but will have a significant market share. In fact, Tesla's revenues of $81 billion in 2022 makes this assumption more plausible, not less so Note that this will still give Tesla more revenues than the largest automobile companies in the world, and will require that they make a transition, at least on core models, to a mass market product (with prices to match). I know that Tesla does and can sell more than just cars (energy solutions and software), but these are businesses that, at best, can add tens of billions of dollars to the mix, not hundreds.In my November 2021 valuation, I had chosen a target operating margin of 16%, higher than the then-prevailing margin of 12.06%. In 2022, Tesla delivered an operating margin of 16.76% before correcting for R&D, and 18.41% after the correction, though its performance varied widely across the four quarters:

Until recently, even Tesla critics would have conceded that Musk, in spite of his numerous faults, was a net positive to the company. In the last year, even Tesla advocates have starting questioning that belief, partly because Musk's Twitter adventures seem to be taking up much of his time, leaving a perceived vacuum at the helm of the company. That may be an overreaction, and I am not quite ready to come to the conclusion that he is net negative for the company, but it is undeniable that the net Musk effect being negative is not being dismissed. There is also the question of whether Musk will come under pressure to sell Tesla shares to meet demands from Twitter lenders, and how that will play out in markets.The Market: The US equity market in January 2023 looks very different from the market at the start of 2022. As I noted in my last post, rising risk free rates and equity risk premiums have pushed up the costs of equity for all companies, and Tesla is not only no exception but is perhaps even more exposed as an above-average risk company. In short, the cost of capital of 6% that I used in November 2021, higher than the median cost of capital of 5.6% for US companies then, no longer is defensible, as the median cost of capital has climbed toward 9.6%.With these changes in mind, I revisited my valuation of Tesla from November 2021 and made the following changes: First, I left my end revenues for Tesla back to $400 billion, still a reflection of my view that electric cars will become the dominant part of the auto market, and that Tesla still has not only a lead in that market, but will have a significant market share. In fact, Tesla's revenues of $81 billion in 2022 makes this assumption more plausible, not less so Note that this will still give Tesla more revenues than the largest automobile companies in the world, and will require that they make a transition, at least on core models, to a mass market product (with prices to match). I know that Tesla does and can sell more than just cars (energy solutions and software), but these are businesses that, at best, can add tens of billions of dollars to the mix, not hundreds.In my November 2021 valuation, I had chosen a target operating margin of 16%, higher than the then-prevailing margin of 12.06%. In 2022, Tesla delivered an operating margin of 16.76% before correcting for R&D, and 18.41% after the correction, though its performance varied widely across the four quarters:

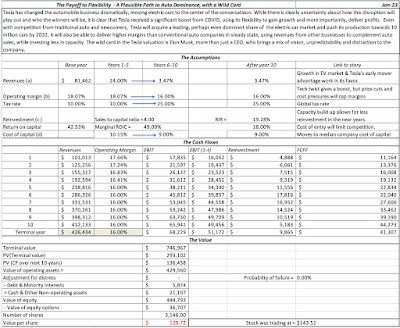

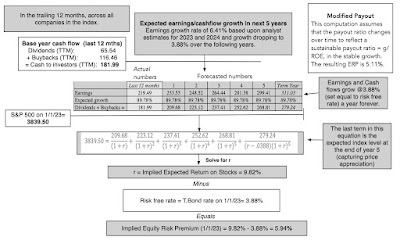

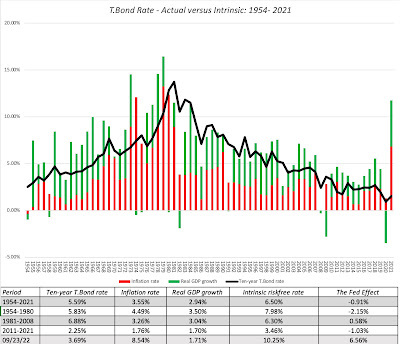

While Tesla's profitability in 2022 has been a pleasant surprise, I have left the target margin at 16% because the forces that pushed the operating margin back down to 16% in the last quarter of 2022, which include price cuts and increasing production costs at their plants, will only intensify as Tesla seeks out market share. There is a niche market story that can be used to justify higher operating margins at Tesla, but that story would be incompatible with it having revenues of $400 billion.Third, my cost of capital for Tesla has jumped to 10.15%, reflecting a world of higher interest rates and risk premiums:

Download spreadsheet

Download spreadsheet

This is still an upbeat story, but the value per share that I get with these updated inputs is about $130, a mark down from my November 2021 valuation, and about 10% below the stock price ($143 on January 25, 2023)

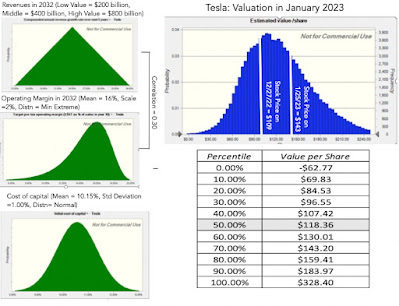

As with my previous valuations of Tesla, I am open about the fact that my Tesla story and inputs come with uncertainties, significant and potentially value-changing. Rather than wring my hands about these mistakes or be defensive about them, I chose to run a simulation, replacing my point estimates for revenue growth, operating margins and cost of capital, with distributions to arrive at the following value distribution

Note that my median value is slightly lower than my base case value, mostly because there are more potential upside values than downside value. The bottom line, though, is that the median value, at $120, confirms that the stock is overvalued, at least based on my estimates, at least at its stock price of $143. However, unlike November 2021 or at other points in Tesla's life, the stock is very much in play, and anyone who bought the stock on 12/27/22, when the price hit $109, would have got a reasonable bargain. I am writing this post, in the aftermath of Tesla's earnings report, and the stock is up in the after market, perhaps in reaction to the fact that the company beat its earnings per share forecast, the least meaningful part of any earnings report. To be honest, there is nothing that I see in that report, which is still barebones, that would lead to fundamentally reassess Tesla's value, but clearly the earnings per share beat and the "news is not as bad as it could have been" effect is clearly playing out in Tesla's pricing.

Lessons for Investing

When valuing companies, it is important that you focus on the task at hand, which is to value a company and make an investment judgment on whether you should buy or sell the company, but it is also productive to look for general lessons that you can use in valuing other companies in the future. The Tesla valuation offers me a chance to examine bigger questions including how much a personality (Musk in the case of Tesla) can affect value, when the laws of business catch up with even the most successful disruptors and finally, and most depressingly, how politics has entered investing and business decisions in ways that we will come to regret.

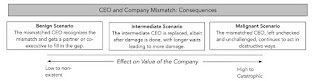

1. Personality-driven Companies

In entertainment, sports, politics and business, we live in a personality-driven world, where individuals are given more attention than institutions. This is not a new phenomenon, but social media has furthered this trend, by giving influential people platforms and megaphones to reach tens of millions of followers. Some of the highest profile corporations in the last decade have tied their business stories to their founders, making it difficult to separate one from the other. In many cases, this has helped, not hurt, these companies, as Jack Ma drew investors and customers to Alibaba with his enthusiasm and energy, and no one sold Tesla to customers and investors better than Elon Musk. In both cases, though, we are discovering that there is a downside to personality-driven companies, since as human beings, these personalities come with good and bad qualities. There is no doubt in my mind that Elon Musk has enough vision to power a dozen companies, but he is also easily distracted and sometimes eccentric, but that is the package that drew people to the company a dozen years ago, when the company was started, that engineered its ascent to trillion-dollar market cap status, just a couple of years ago, and is now, at least in the eyes of some, weighing down the company.

Good founders find ways to build businesses that outlast them, as Bill Gates did at Microsoft and Jeff Bezos at Amazon, but that required them to set aside egos and to overcome their desire for control. With Tesla, I still believe that Musk's vision is critical, but it is essential for Tesla's long term success that he takes two actions. The first is to stop being the spokesperson for the company on all things small and large, and allow others in the company to find their voices. The second is to either build a management team that can run the company without him, if that team does not exist, or if it does, to give more visibility and front-stage status to the members of that team. I will wager that many investors in Tesla would be hard pressed to name its CFO or others in its top ranks, and that is an indication of how completely Musk has dominated the Tesla conversation.

2. The Universal Laws of Business and Economics

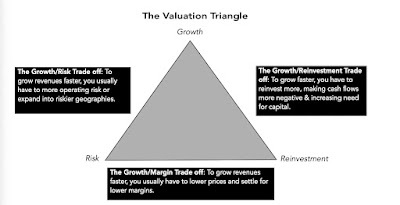

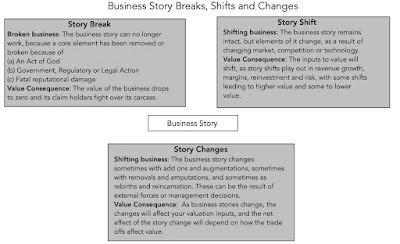

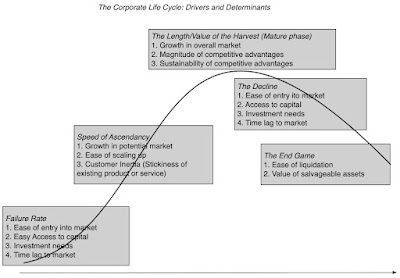

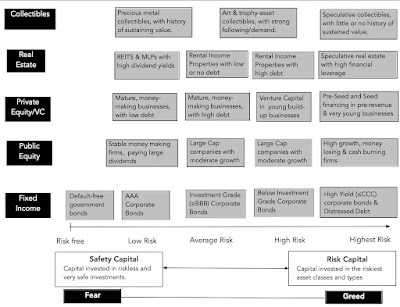

When looking at businesses, it is worth remembering the business rules that have always governed success and failure, and recognize that while there are some companies that can deviate from these rules for a period of time, they eventually find themselves subject to them. I capture these business rules in what I call my valuation triangle, shown below:

Put simply, most businesses that want to grow faster have to accept that this higher growth will come with more risk (because it will require entering riskier geographies or marks segments), will need more investment in capacity (to be able to deliver on that growth) and often require accepting lower operating margins (because you may have to cut prices to sell more). For most of the last decade, Tesla has seemed to be impervious to these rules, showing a capacity to deliver revenue growth with rapidly rising margins in a competitive electric car business, and doing so with far less reinvestment than other automobile companies.

That said, though, there are indications that the company, while still delivered wondrous results, is finding itself coming back to earth. The recent report that the company plans to cut prices for its cars in the United States may be a transitory change in policy, but it is more likely a reflection of the reality that customers, for whatever reasons, are now willing to at least look at other carmaker's offerings, if the price is right. In the same vein, the challenges that Tesla is facing in its manufacturing plants and with supply chains are familiar problems that all manufacturing companies face, and reflect the fact that it it Tesla no longer a niche company with absolute pricing power, selling to a fanatically loyal customer base. My guess is that the stories, while more negative than positive, will even out over time, and that Tesla will be able to stay ahead of its competitors, but for those investors and analysts who are used to Tesla posting super normal performance, it may take time to stop treating normal performance as a negative surprise.

3. Everything is political

In a world where where you shop, to where you eat and even which sports teams you cheer on depend on which side of the political divide you fall on, is it any surprise that politics is now affecting business and investing choices as well? It is one reason why I have argued against bringing ESG into companies and investing, because there is almost no social issue that an ESG-measuring service can defensibly bring into a score, without a backlash. In the case of Tesla, the politics of the moment are undeniably an issue, and I would argue that where your political views will have more of an effect on whether you think Tesla is under or over valued than any of its operating numbers. It is amusing to see Tesla advocates become adversaries overnight, mostly because their politics have diverged from Musk's, and Tesla opponents become its defenders, because they are in political agreement with Musk. As should be clear from my many posts on Tesla, I fall in the muddled middle when it comes to Musk. I believe that he is a visionary, not so much because Tesla is at the cutting edge of technology, but because he has changed the automobile business and our driving choices fundamentally. There are qualities that I admire in him, and qualities that I do not, but I think that as a society, we are better off with him than without him. That said, I would like to think that my decisions on whether to buy or sell Tesla will be unaffected by my personal views on Musk, but that may be just my delusion speaking.

YouTube Video

Spreadsheet links

Valuation (DIY) of Tesla in November 2021Valuation (DIY) of Tesla in January 2023January 21, 2023

Data Update 2 for 2023: A Rocky Year for Equities!

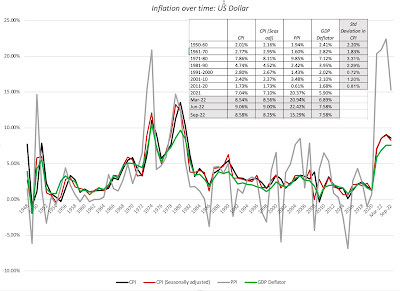

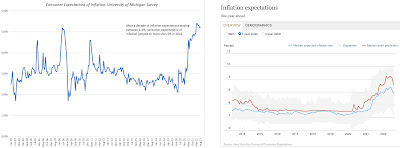

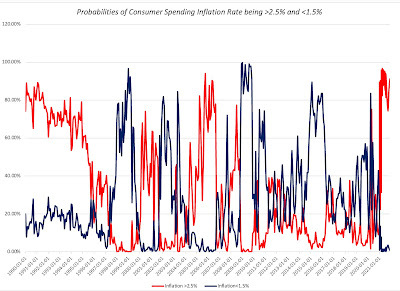

It is the nature of stocks that you have good years and bad ones, and much as we like to forget about the latter during market booms, they recur at regular intervals, if for no other reason than to remind us that risk is not an abstraction, and that stocks don't always win, even in the long term. In 2022, we needed that reminder more than ever before, especially after markets came roaring back from the COVID drop in 2020 and 2021. While there are many events during 2022, some political and some economic, that one can point to as the reason for poor stock returns, it is undeniable that inflation was the driving force behind the market correction. In this post, I will begin by chronicling the damage done to equities during 2022, before putting the year in historical context, and then examine how developments during the year have affected expectations for the future. I will follow up by looking at the mechanics that connect stock prices to inflation, and examine why the damage from higher inflation can vary across companies and sectors.

Stocks: The What?

We invest in equities expecting to earn more than we can make on risk free or guaranteed investments, but the risk in equities is that actual returns can deviate from expectations. In some years, those deviations work to our benefit and in others, it can hurt us, and 2022, unfortunately, fell into the latter column. In this section, I will begin with a deconstruction of stock returns in 2022 and the year's place in stock market history. I will then provide a template for estimating expected returns on equities, and examine how expected returns changed during the course of the year.

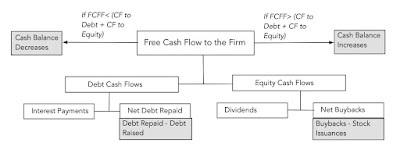

Actual Returns

Your returns on equities come in one of two forms. The first is the dividends you receive, while you hold stocks, a cash flow stream that provides a measure of stability to investors who seek it. The other, and less predictable component, is the price change, which in good years adds to the return as a price appreciation, and in bad years, often overwhelms dividends to deliver negative returns.

The Year in Review

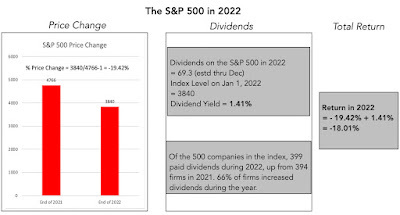

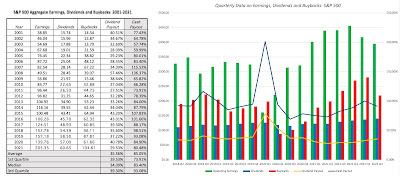

At the start of 2022, the S&P 500 was at 4766.18, up from 3756.07 at the start of that year. During the course of 2022, the index was staggered by political events, with Russia's invasion of Ukraine upending global economies, and by inflation, which entered the year high, and continued on that path through the course of the year. The graph below shows the S&P 500 at the end of each month, from December 31, 2021 to December 31, 2022, and the resulting monthly returns:

Aggregating over the entire year, the index declined 19.42% in 2022, and while the dividends during the course of the year rose, the dividend yield of 1.41% provided only a minor offset, resulting in total returns of -18.01% on the S&P 500 for the year:

I know that this is US-centric and large-cap oriented and I will cover returns in other geographies and across broader classes of stocks in my next few posts, but suffice to say, that in this year, there were no sectors or geographies that were spared.

I know that this is US-centric and large-cap oriented and I will cover returns in other geographies and across broader classes of stocks in my next few posts, but suffice to say, that in this year, there were no sectors or geographies that were spared.And in historical context

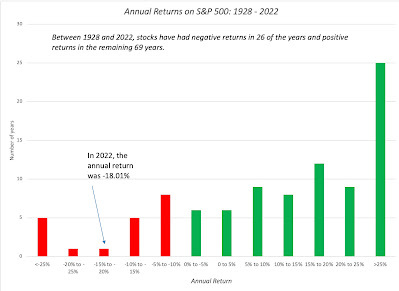

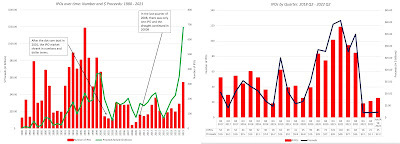

It is undeniable that 2022 was a bad year for stocks, but in historical context, how bad a year was it? I maintain a database of historical returns on stocks, bonds, bills and other asset classes on my webpage, and I looked at the annual returns, by year, starting in 1928 through 2022 for US stocks. In the graph below, I look at the distribution of annual returns over those 95 years, paying special attention to the negative years:

S&P 500 officially came into existence in 1957, but we filled in earlier years using stock return data

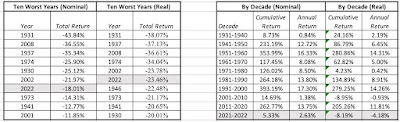

S&P 500 officially came into existence in 1957, but we filled in earlier years using stock return dataAs you can see, it is not uncommon for stocks to have negative years, but the returns in 2022 of -18.01% put them at the tail end of the historical distribution. In the table below, I look at how 2022 ranks in terms of bad years over the 1928 - 2022 time period:

In nominal terms, i.e., before taking into account inflation, 2022 ranks as the seventh worst year, over the 95-year time period, and in real terms, it moves up to being the sixth worst year, with real returns of -23.48%. No matter how you slice it, there is no denying that 2022 was the worst year for US equity investors since 2008, and the magnitude of the damage is even more staggering, if you consider it in market value terms. During the course of 2022, US equities collectively lost $11.6 trillion in market capitalization, but for balance, it is also worth noting that US equities are still holding on to a gain of $6.9 trillion on their market capitalization at the end of 2019. Given that we endured a pandemic, multiple political crises and wars in the three years since, that is almost a miracle.

In nominal terms, i.e., before taking into account inflation, 2022 ranks as the seventh worst year, over the 95-year time period, and in real terms, it moves up to being the sixth worst year, with real returns of -23.48%. No matter how you slice it, there is no denying that 2022 was the worst year for US equity investors since 2008, and the magnitude of the damage is even more staggering, if you consider it in market value terms. During the course of 2022, US equities collectively lost $11.6 trillion in market capitalization, but for balance, it is also worth noting that US equities are still holding on to a gain of $6.9 trillion on their market capitalization at the end of 2019. Given that we endured a pandemic, multiple political crises and wars in the three years since, that is almost a miracle.Expected Returns

Markets are driven by expectations, and while expectations for the future can be affected by what has happened in the past, they are still worth exploring. After a year of being pummeled by markets, what are investors pricing stocks to make in 2023 and beyond? And will they be disappointed or delighted by what the year delivers? Those are the questions that investors have to answer today and I will try to provide my perspective in this section.

Actual vs Expected Returns

As you saw in the previous section, actual returns on stocks can be negative, and significantly negative, in some periods, and those negative returns can sometimes extend into decades. Those who invested in the Nikkei at its peak on December 29, 1989, have spent the decades since trying to get back to that level. The notion that stocks always win in the long term is a dangerous one, and while those pushing it claim to have the data on their side, it is worth remembering that the use of US data to make this case is statistically flawed. The US was one of the most successful of global equity markets of the twentieth century, and to use its historical record as the basis for all equity investment in the future strikes me as wrong headed.

That said, when investors buy equities, it would be both irrational and illogical to settle for expected returns that are less than what you can earn on risk free or guaranteed investments, though behavioral finance suggests that both irrationality and illogic are persistent human traits. The premium that investors demand over and above the risk free rate is the equity risk premium, and practitioners in finance have wrestled with how best to estimate that number, since it is not easily observable (unlike the expected return on a bond which manifests as a current market interest rate).

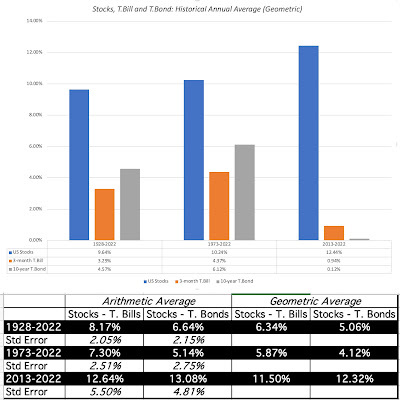

a. Historical Equity Risk Premium

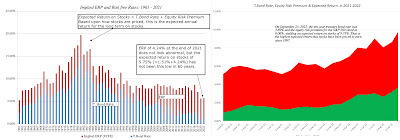

The conventional wisdom, at least as taught in business schools and practiced by appraisers, is that the only practice way to estimate equity risk premiums for the future is to use equity risk premiums earned in the past. Thus, historical risk premiums are viewed as the best estimates for the future, though analysts disagree not only about how far back in time they should go, whether to compare stock returns to T.Bill or T.Bond returns and even on how to compute the historical average return (arithmetic versus geometric averages). The graph and table below provide my estimates of the historical equity risk premiums in the US market:

As you can see, I arrive at premiums ranging from 4.12% to 13.08%, depending upon my estimation choices on time period, treasury rate used and averaging approach, but I don't use any of these numbers as my estimate for the future for two reasons. The first is that the use of historical risk premiums is predicated on the belief that the future will look like the past, and the world, in all its dimensions, has changed dramatically over the last few decades. The second is that even if you are comfortable with assuming mean reversion, the estimates from the past are extremely noisy (have large standard errors), with the premium from 1928 to 2022 having a standard error of 2.15%. In effect, even with that long period, the best I can offer, if you are looking for an equity risk premium for stocks over T.Bonds is a range so wide (2.34% - 10.94%, i.e., the average plus or minus two standard errors) that it is not useful

As you can see, I arrive at premiums ranging from 4.12% to 13.08%, depending upon my estimation choices on time period, treasury rate used and averaging approach, but I don't use any of these numbers as my estimate for the future for two reasons. The first is that the use of historical risk premiums is predicated on the belief that the future will look like the past, and the world, in all its dimensions, has changed dramatically over the last few decades. The second is that even if you are comfortable with assuming mean reversion, the estimates from the past are extremely noisy (have large standard errors), with the premium from 1928 to 2022 having a standard error of 2.15%. In effect, even with that long period, the best I can offer, if you are looking for an equity risk premium for stocks over T.Bonds is a range so wide (2.34% - 10.94%, i.e., the average plus or minus two standard errors) that it is not usefulImplied Expected Returns

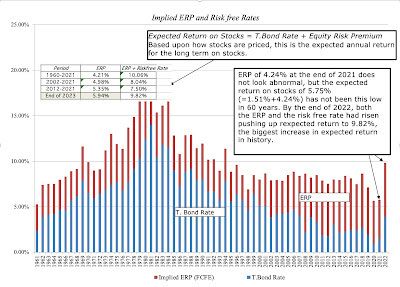

There is another approach to estimating expected returns on stocks, and equity risk premiums, and it is forward-looking. It too requires estimate for inputs, but the range of error is magnitudes smaller than with historical premiums. In this approach, I draw on a technique used to compute the yield to maturity on a bond, the discount rate that makes the present value of cash flows on the bond (coupons and face value) equal to the price of the bond, and extend it to equities. To illustrate, I estimate this implied equity risk premium for the S&P 500 at the start of 2023, using the index level as the price that I pay on the index and using market estimates of earnings and dividends/buybacks on the index for the next five years and beyond.

As with the yield to maturity for a bond, I solve for the discount rate (IRR) that makes the present value of cashflows on the index equal to the level of the index. At the start of 2023, by my calculations and with analyst estimates of earnings, I estimate an expected return of 9.82%. which when you net out the T.Bond rate that day results in an implied equity risk premium of 5.94%. There are clearly input estimates that you can take issue with, especially on earnings and cashflows. Thus, if you assume that analysts are over estimating earnings and/or that companies will return less of these earnings to investors in the form of dividends and buybacks, the estimated equity risk premium will decrease, and if you assume that growth will be stronger than forecast, the equity risk premium will rise. In this spreadsheet, you can see that making different assumptions on these fronts yields equity risk premiums ranging from 4.83% to about 6%, a much narrower range than from historical risk premiums.

In historical context

In my first data post, I noted the increase in equity risk premiums during 2022 from 4.24% at the start of 2022 to 5.94% at the start of 2023. I posited that any debate about whether the market, as it stands now, is fairly, under or over valued is really one about whether the equity risk premium at the start of 2023 is too high (in which case, the market is under valued) or too low (in which case, it is overvalued). To answer that question, and address the question of where the expected return of 9.82% stands in historical context, I report the expected returns and equity risk premiums for the S&P 500 from 1960 to 2022:

At 5.94%, the implied equity risk premium is closer to top of the range of historical risk premiums, but the most striking feature of 2022 is that the expected return on stocks, at 9.82%, is now at its highest level since 1995.

At 5.94%, the implied equity risk premium is closer to top of the range of historical risk premiums, but the most striking feature of 2022 is that the expected return on stocks, at 9.82%, is now at its highest level since 1995. Stocks: The So What?

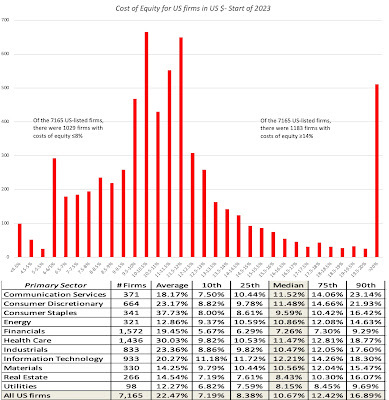

It is worth noting that in valuation, demanding a higher expected return depresses value today, and the increase in expected returns over 2022 is therefore consistent with the decline in stock prices during the year. In fact, the drop in stock prices of 20% is mild, given the surge in expected returns during the course of the year. There is another reading of this expected return that ties into investment and growth, where the expected return on stocks is the cost of equity that companies need to clear to make investments. In short, an average-risk project with a return on equity of 7%, which would have passed the investment test at the start of 2022, because it was greater than the cost of equity of 5.75%, prevailing at the time, would not pass muster at the start of 2023.

The effects of a higher equity risk premium are also not uniform across all stocks, with higher risk stocks seeing much greater rises in their costs of equity than lower risk stocks. The table below provides the cost of equity distribution across US companies at the start of 2023:

Note that, for the first time in a decade, more US firms have double digit costs of equity than single digit values, and while that may seem shocking to younger analysts, it is a return to what used to be normal in the pre-2008 market.

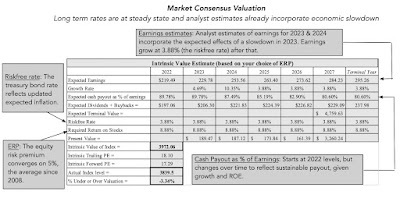

Stocks: The What Next?

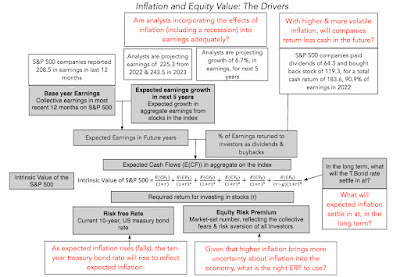

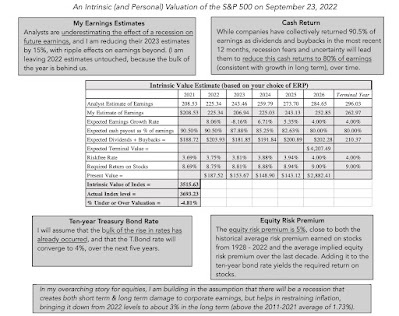

To close this post, I revisited my valuation of the S&P 500 on September 23, 2022, and since much of last year's changes to the risk free rate, earnings expectations and the equity risk premium had happened by then, my value of the index has not changed much. In fact, if you view the current treasury bond rate as reflective of the market consensus on future inflation and rates, and assume that analyst estimates of earning already incorporate the effects of an economic slowdown in 2023 and 2024, the index value comes in at almost the current index level:

Download spreadsheet

Download spreadsheet

In sum, with analyst estimates of earnings for the next two years powering earnings expectations, and an desired equity risk premium of 5% (close to the average premium in the post-2008 time period), stocks started the new year closer to fair value than being under or over valued.

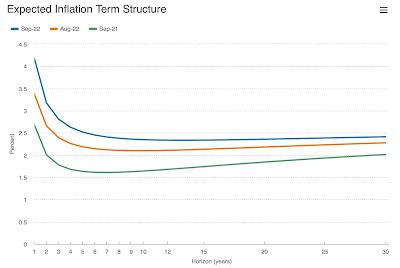

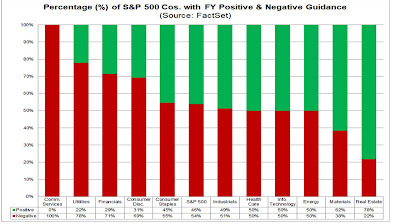

The market consensus can be wrong, and as the last year has shown, markets can change their minds, and especially so on two variables. The first is inflation, and whether it will recede to pre-pandemic levels or stay elevated, with consequences for both interest rates, nominal earnings growth in the long term and reinvestment. The second is the economy, where talk of recession fills the air but where a whole range of outcomes is possible from no recession to a steep drop off in economic indicators.

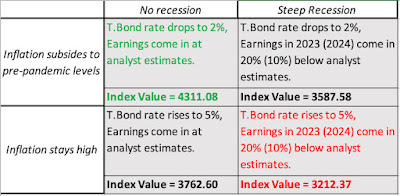

Download spreadsheets: Low inflation & no recession, Low inflation & steep recession, High inflation & no recession, High inflation & steep recessionAs you can see, the most favorable scenario for the market is one where inflation subsides quickly to pre-pandemic levels (1-2%), bringing down the treasury bond rate, and the economy escapes a recession, leaving corporate earnings unscathed; in this scenario, the index value is 4311, about 10% higher than the current level (in January 2023). In the least favorable scenario, inflation stays high, pushing interest rates further up, and the economy enters a steep recession, with earnings dropping 20% (10%) from analyst estimates for 2023 and 2024; in this scenario, the index value is 3212, leaving the market over valued by almost 20%. Note that I am not calling it the worst case scenario, because that depends on how high inflation gets, with the higher the inflation, the more dire the outcomes for stocks, as well as how bad a recession is, with worse economic outcomes lowering value more.

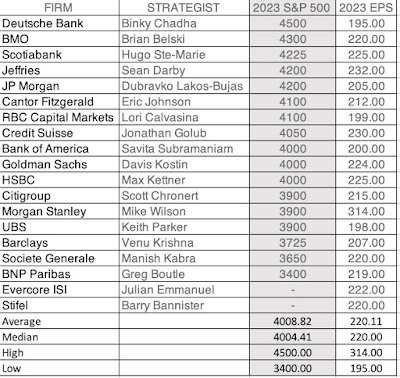

Download spreadsheets: Low inflation & no recession, Low inflation & steep recession, High inflation & no recession, High inflation & steep recessionAs you can see, the most favorable scenario for the market is one where inflation subsides quickly to pre-pandemic levels (1-2%), bringing down the treasury bond rate, and the economy escapes a recession, leaving corporate earnings unscathed; in this scenario, the index value is 4311, about 10% higher than the current level (in January 2023). In the least favorable scenario, inflation stays high, pushing interest rates further up, and the economy enters a steep recession, with earnings dropping 20% (10%) from analyst estimates for 2023 and 2024; in this scenario, the index value is 3212, leaving the market over valued by almost 20%. Note that I am not calling it the worst case scenario, because that depends on how high inflation gets, with the higher the inflation, the more dire the outcomes for stocks, as well as how bad a recession is, with worse economic outcomes lowering value more.Summing up One of the rituals that start the market year is for market strategists at investment banks to make their best predictions for where they see markets going over the course of the year. While this exercise has zero predictive power, and perhaps even a perverse relationship with actual returns, it does offer some insights into how much strategists are in agreement or disagreement about the year to come. At the start of 2023, here are the predictions from strategists for the year:

What should you do with these forecasts? Absolutely nothing, but the wide divergence in forecasts comes from different expectations of how the inflation/real economy story will play out. Rather than adopt one of their outlooks, or mine, you should, as an investor, find your point of view and let it drive your investment actions for the year. The first step in being a good investor is to take ownership of your investment decisions, and I hope that my framework/spreadsheet helps you on that path.

YouTube Videos

Datasets (If you have download trouble, switch browsers)Historical Returns on Stocks, Bonds, Bills and Other Assets- 1928-2022Implied Equity Risk Premiums on US stocks- 1960 - 2022SpreadsheetsImplied Equity Risk Premium Calculation (Jan 1, 2023)Valuation of the S&P 500 on January 1, 2023

January 6, 2023

Data Update 1 for 2023: Setting the table!

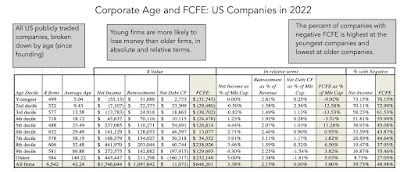

Data: Trickle to a Flood! It is perhaps a reflection of my age that I remember when getting data to do corporate financial analysis or valuation was a chore. To obtain company-level information, you needed to find its annual reports in physical form and for industry-level data, you were dependent on services that computed and reported industry averages, such as Value Line and S&P. The times have changed, and if there is a problem now, it is that we have too much data, rather than too little. As I noted in my posts on data disclosure last year, this has led to at least three unhealthy developments. Data distractions: Faced with massive amounts of data, quantitative as well as qualitative, many investors and analysts find themselves distracted by immaterial, irrelevant and sometimes misleading data points along the way. Data as a crutch: At the other extreme, there are some who believe that they answer to every question lies in the data, and that when seeking an input for valuation and corporate financial analysis, the data will provide it. Rather than make their best judgments or reason their way, when faced with estimation challenges, these investors and analysts embark on a search for more data, and if they do not find that data, they give up.Data bias: There is the canard that data is objective, as opposed to estimates or judgments, which are considered subjective. That is not true! In my experience, data is malleable, and if there is enough of it at your disposal, you can screen it and selectively choose the data to support whatever viewpoint you want to advance.During the course of my corporate finance and valuation journey, I have been guilty of all three of these sins, and it is to counter these pre-dispositions that I started spending the first week of every year looking at data with four objectives:Get perspective: One of the challenges that anyone doing business analysis, investing or valuation faces is getting a measure of what comprises a reasonable value for a business metric. Thus, without a sense of what comprises a high or low profit margin for a firm, or what the cost of capital is for the typical company, it is easy to create "fairy tale" valuations and analyses. By the same token, it is impossible to use a pricing metric (PE or EV to EBITDA), without a sense of the cross sectional distribution of that metric at the time.Mean reversion: I am not a knee-jerk believer in mean reversion, but the tendency for numbers to move back towards averages is a strong one. That said, to use mean reversion in analysis or investing, you need to know what these averages are, either over time or across companies, and data can help in that pursuit. Counter made-up numbers: It remains true that people (analysts, market experts, politicians) often make assertions based upon either incomplete or flawed data, or no data at all. For instance, is it true, as some assert, that inflation was high last year because companies raised prices to increase profits? Or, do US companies pay far less in taxes than companies incorporated in the rest of the world? Rather than indulge in endless debates, where each side provides anecdotal evidence, data can prove to be the tie-breaker.Check rules of thumb: Investing and corporate finance are full of rules of thumb, many of long standing. For example, I have seen it asserted that a stock that trades at less than book value is cheap or that a stock that trades at more than twenty times EBITDA is expensive. These assertions may very well be true, but cheap and expensive, at least in pricing terms, is relative, and looking at the data can help you detect rules of thumb that work from those that do not.When valuing or analyzing a company, I find myself looking for and using macro data (risk premiums, default spreads, tax rates) and industry-level data on profitability, risk and leverage. Rather than collecting this data each time I do an analysis, I realized that having these numbers computed and ready to go ahead of the analysis not only saves me time, but also allows me to focus more on the company that I am valuing and analyzing. I also realized that while these numbers are useful to me, they could be useful to others doing analysis as well, and I could not think of a single reason not to share what I had on hand.

Data: Sources and Description My first attempt at sharing data was in 1997, and it was limited to about a dozen data sets, all related to US companies, and I never expected very many people to use my data. That has changed, and this year, I am posting two hundred data sets, including more than a thousand data items, and extended the coverage to global companies. While I hope that you find this data useful, I also hope that you will spend a few minutes reading what I have to say about the companies that comprise my data universe, the data items I report on, the timing of the data and caveats.

Data Universe and Grouping At first sight, computing an industry average seems like a simple computation, where you take individual company numbers in an industry group and average them out. However, embedded in this statement are multiple estimation choices that you have to make that affect the reported numbers, and it behooves me to describe my choices:

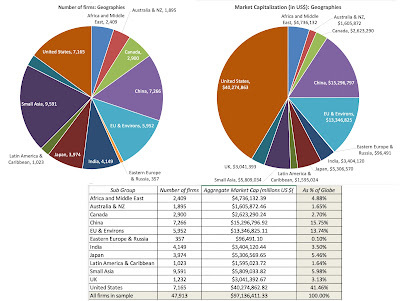

1. Data universe: In my sample, I include all publicly traded firms with market capitalizations that exceed zero, traded anywhere in the world. While there are risks bringing in very small and lightly-traded companies, with shaky data, into the sample, I include them to avoid the biases that will be created in industry averages by looking at just larger publicly traded companies, or just US-listed companies. In January 2023, I ended up with 47,913 publicly traded firms in my sample, with the pie chart below providing a geographic breakdown.

Speaking of biases, I do exclude privately owned (non-listed) companies for two reasons. The first is that in much of the world, these companies are not required to make their financial statements public, thus making it impossible to get the data. The second is that for data items that require market prices, including all the pricing metrics, private businesses cannot be included, since they have no market values.

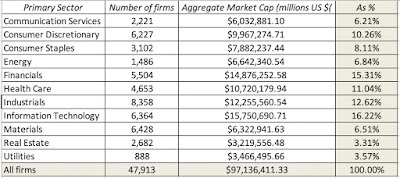

2. Sectors and Industries: To make data useful for corporate financial analysis and valuation, I break the companies down into groupings, based upon the sectors and industries that they operate in. For the former, I use S&P's sector categorization and for the latter, I create 95 industry groups, built to allow users of my data to compare statistics over time. The sector breakdown of my overall sample is reported below:

My industry groupings are open to questioning for many reasons. First, for multi-business companies, I use the company's primary business (in terms of revenues) for categorization. Second, for some companies, it is not clear what industry group best fits the company. Thus, for Apple, it is unclear whether to put the company into company hardware, reflecting its history as a computer maker, or telecommunication equipment, reflecting its current dependence on the iPhone.

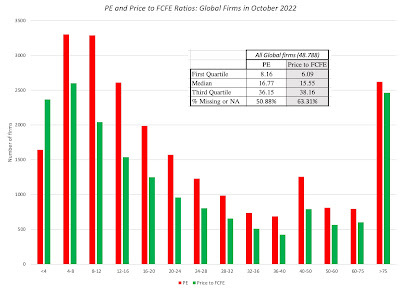

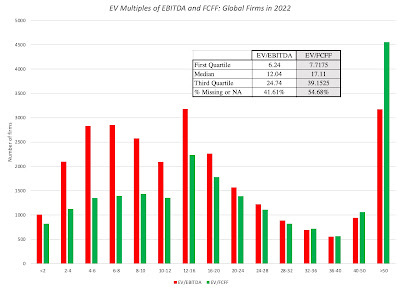

Data Items Much of my focus, when it comes to data, is on company-specific variables, rather than macro economic data, for two reasons. The first is that there are other and much better sources for raw macroeconomic data than mine, and my favorite remains. Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED): This is hands down, in my view, the best site for macroeconomic data in the world. While its focus is naturally on the US economy, inflation and rates, there is data for the rest of the world as well. I do report on a few market-wide data items especially on risk premiums for both equity and debt. The second is that in my line of work, which is corporate finance and valuation, the numbers I need lie in micro or company-level data, not in the macro space. At the company-level, I provide data on risk, profitability, leverage and dividends, broken down by industry-groups, to be used in both corporate finance and valuation. I also report on pricing statistics, again broken down by industry grouping, with equity (PE, Price to Book, Price to Sales) and enterprise value (EV/EBIT, EV/EBITDA, EV/Sales, EV/Invested Capital) multiples. The table below shows a subset of the data items that I have on my website, with the links to the US versions of the data sets, in html. To get to the excel versions of this data, or the excel versions by region (Emerging Markets, Europe, Australia & Canada, Japan) as well as globally, please go the current data page of my website:

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; } Risk MeasuresCost of FundingPricing Multiples 1. Beta1. Cost of Equity1. PE & PEG 2. Standard deviation in stock price2. Cost of Debt2. Price to Book 3. Standard deviation in operating income3. Cost of Capital3. EV/EBIT and EV/EBITDA 4. High-Low Price Risk Measure

5. Standard deviations in equity and firm value 4. EV/Sales and Price/Sales

5. Per-employee Statistics ProfitabilityFinancial LeverageReinvestment 1. Net Profit Margin1. Debt ratios (Debt to capital, Debt to EBITDA)1. Cap Ex & Net Cap Ex ((including acquisitons) 2. Operating Margin2. Debt breakdown2.. Non-cash Working Capital 3. EBITDA, EBIT and EBITDAR&D Margins3. Goodwill & Impairment

4. Financing Flows Accounting ReturnsDividends & OwnershipRisk Premiums 1. Return on Equity1. Dividend Payout & Yield1. Historical returns on US stocks, bonds, and other asset classes 2. Return on Invested Capital2. Dividends/FCFE & (Dividends + Buybacks)/ FCFE2. Historical Implied ERP for US 3. Excess Returns (ROE minus cost of equity, ROIC minus cost of capital, EVA)3. Insider, Institutional & CEO holdings 3. Equty Risk Premiums, by Country 4. Bond Default Spreads Growth RatesAccounting Clean upTax Rates 1. Historical Growth Rate in Revenue/Earnings

1. Leases as debt: Effects1. Marginal tax rates, by country 2. Sustainable Growth Rate in Net Income & Operating Income2. R&D as cap ex: Effects2. Effective tax ratesIf you are interested in the archived data from prior years, you can get them by going to this link. For a description of the variables (and how I compute them), please try this link.

Data Timing There is one final estimation detail that needs clarification. I did my updates in the last week (January 1- January 5, 2023), and used the most updated data that I could find on each company. For market data, where the updating is continuous, that is data as of the January 1, 2023. Thus, market capitalization, interest rates and risk premiums, the data is as of that date.For accounting flow items, in income statements and statements of cash flows, such as revenues, earnings and expenses, I used the data in the most recent twelve months of reporting; for most firms, that data is from October 2021 to September 2022.For accounting stock items, from balance sheets, I use the numbers from the most recent balance sheet; again, for most firms, the numbers are from the balance sheets, as of September 30, 2022 or the most recent quarterly statements.While these timing differences may strike some as inconsistent, they do meet my timing consistency test, which is that they are the most updated numbers that decision-makers (CFOs and investors) would have as of January 1, 2023.

Data Caveats I have no qualms about sharing my data, since there is nothing particularly original or unique about what I do, and I am glad that there are some to whom the data is proving useful. If I save analysts and investors time in their decision making, I consider the time spent on my data analysis to have earned its required returns and more. Given the wide range of uses to which my data is put, I do have some caveats on its usage.

Mistakes and Errors: I am a team of one, reflecting more my desire for control that unwillingness on the part of others to help. That said, working with a data sheet with 47,913 companies and hundreds of data items can get daunting, as is updating individual excel sheets, by variable and region. If you find a mistake or mistakes, please bring it to my attention and I will fix it.Judgment calls: I have made judgment calls starting with my creation of industry groups (which you may not like) and my assignment of companies into groups. Some take issue with my regional classifications, arguing that Mexico should be North America (geographically, you are absolutely right) rather than in Latin America (which is where I put it).Company-level data: I do not provide company-level data for two reasons. One is that it would violate agreements that I (or NYU) have with my raw data providers and the other is that getting company-level data has become trivial. I know that most of you cannot afford a Bloomberg terminal or S&P Capital IQ, but you can get the data not just from Yahoo! Finance but also from a variety of online data services that are affordable and very well done. Agenda: If you are using my data to advance a point of view that you hold, you are welcome to do so, but please be clear that this is your reading of my data, not mine. If you are in a fight (legal or online) and using my data as ammunition, you are entirely on your own, and I will not enter the fight on either side, unless you have a clarification question. Staleness: I update my data once a year, and I will not return to do an update until January 2024; the equity risk premiums for the US will get updated every month and the equity risk premiums for other countries will get a mid-year update. While I have no compunctions continuing to use industry averages for risk, profitability and leverage over the course of the year, the pricing metrics (PE, EV/EBITDA etc.) will become dated as the year goes on, and especially so if the market moves up or down significantly.You owe nothing to me for the data, and if it does get you into trouble, feel free to blame me. If you really want to offer something in return, the best favor you can do for me is to help someone else out there.

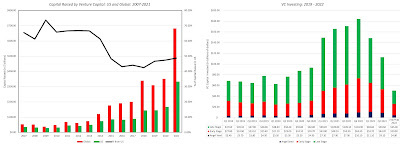

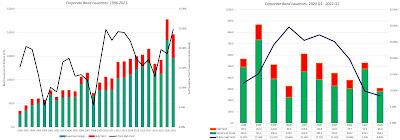

The Posts to come In the posts to come, I will talk about what the numbers tell us about the state of the market and the companies that inhabit them, as of the start of 2023. It is undeniable that 2022 was a tumultuous year, with inflation taking center stage, and driving markets. In my next three posts, I will look at inflation's effects on equity markets (in post 2), government and corporate bond markets (in post 3) and other asset classes (real estate, collectibles and cryptos). For those who had become somnolent about country risk, the year provided a reminder of how quickly country risk can flare up and change, with Russia's invasion of Ukraine a precipitating factor, and in my fifth post, I will look at the evolution of country risk during the year. In the three posts that follow, I will look at the shifts in corporate hurdle rates (in post 6), debt loads and worries (in post 7) and dividends/cash returned in post 8. In the ninth post, I will look at how market pricing changed during 2022, across sectors/industries (with technology taking the biggest hit) as well as across growth and corporate life cycles. There is always the chance that I will get distracted along the way, since I want to value Tesla later this month and return to my FANGAM valuations in February!

YouTube Video

LinksCurrent data from January 2023 (on my webpage)Archived data (on my webpage)Variable definitions

December 21, 2022

A Return to Teaching: The Spring 2023 Edition

If, as you read this post, it feels like you have read it or a close variant before, it is because you have. Each year, ahead of teaching my classes at NYU's Stern School of Business in the spring, I invite readers to accompany me on my journey, and this year is no different. Starting in late January 2023, I will be back in the classroom, teaching valuation and corporate finance to the MBAs and valuation to the undergraduates, and these classes will continue through May 2023. If you are curious about the content of these classes, and may want to partake, I will use this post to lay out my teaching philosophy, to describe the classes that I teach and provide options that you may be able to use to take them.

Teaching Philosophy

I have heard the old saying that "those who can do, and those who cannot teach", and I won't get defensive in response, because it may be true. I would like to believe that I am capable of both doing and teaching valuation and corporate finance, but I will leave that judgment for you to make, since my valuations and corporate finance assessments are in the public domain (on my blog and in my lecture notes). If your query is why I would continue to teach rather than seek out more lucrative careers in investing or banking, my answer is a simple one. I love teaching and if you follow my classes, I hope it shows, and my teaching philosophy can be summarized in six precepts:

Preparation is key: Paraphrasing Edison, teaching is 90% perspiration and 10% inspiration. If you are prepared for your class, you are well on your way to being a good teacher.Respect your students: I believe that anyone who sits on my classroom is as capable as I am, though perhaps not as experienced, and is passionate about learning.Be fair: I don't believe that students dislike or punish tough teachers, but I do believe that they dislike and punish teachers who are unfair, either in the way they test students or in the way they grade them. I know that I will make mistakes, but as long as I keep an open door and correct my mistakes, I think that students will cut me some slack. Have empathy: It has been a long time since I was a student in a classroom, but I try to keep my memory fresh by remembering the things I disliked in my classes and trying not to repeat them.Teaching is not just in the classroom: My impact on students does not come just from what what I do in the classroom. It is affected just as much but what I do outside the classroom, in my office hours and in my interactions (online and in person) with my students.Have fun: If you look at the joy that young children show when they learn something new, it is obvious that human beings enjoy learning (though our education systems are often designed to stamp out that joy). I want my classes to be meaningful, impactful and profound, but I also want them to be fun. For that to happen, I have to have fun teaching and I will!Older, though not wiser, as I start my 37th year teaching at NYU, I am looking forward to class just as much as I did the very first year that taught, as a visiting lecturer at the University of California at Berkeley in the fall of 1984.

Course Offerings

I am a dabbler, someone who knows a little bit about a whole host of subjects, without being close to an expert on any one of them. In a world where specialization is the norm, this does put me at a bit of a disadvantage, since there are many who know a great deal more about almost any topic that I choose to talk about, but I do think that it gives me a big-picture perspective that helps me find answers. As you will see in this section, I teach a range of courses, and I hope that my teaching of each course is informed by thinking about and teaching of the other courses.

1. Pre-game Prep

If there is a lesson be learnt from the last few years of market mayhem, it is that far too many investors, professional as well as retail, seem to have lost their moorings (or never had them in the first place), when it comes to the basics of accounting, finance and statistics. In the last few years, I have created my own versions of each of these disciplines, reflecting the tools and skills that I draw upon in my valuation and corporate finance classes.

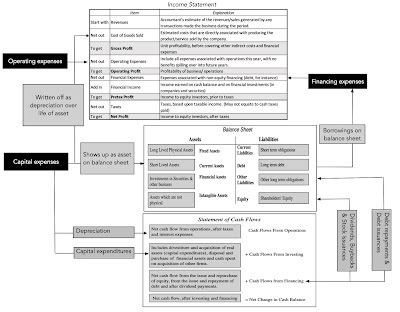

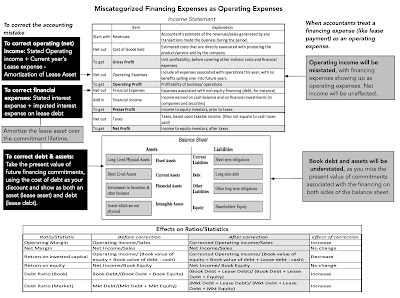

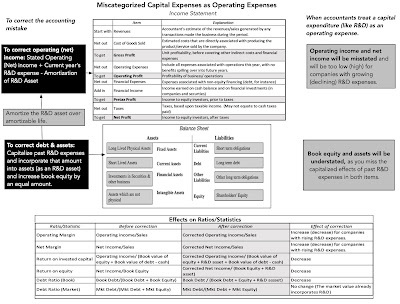

a. Accounting

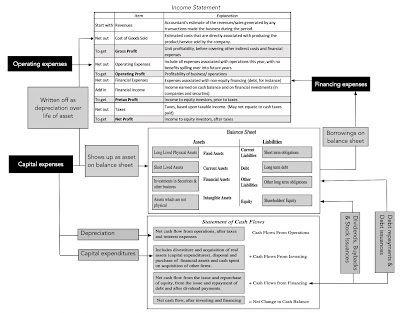

Much of the raw data that you use in corporate finance and valuation comes from accounting statements, and if you do not understand the difference between operating and net income, you are fatally handicapped. If your accounting basics are strong, you can move right along, but if they are shaky, I have an abbreviated online accounting class, with twelve sessions that around built around using the financial statements (income statement, balance sheet and statement of cash flows) to assess a firm’s financial standing, as a prelude to analyzing or valuing it.

Link to accounting class

Link to accounting class

Just as a note of warning, this is my quirky version of accounting, and I don’t follow the accounting script in this class. I challenge what I see as indefensible practices in accounting, including the expensing of R&D (a capital expense) and inconsistencies in accounting ratios.

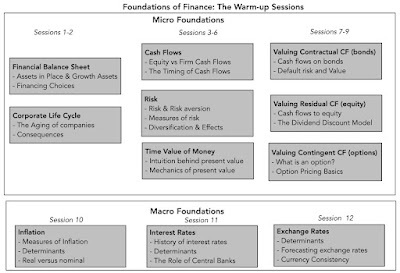

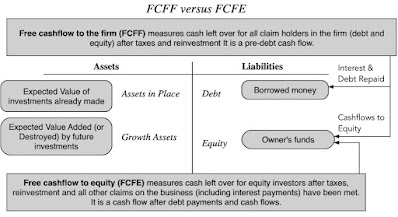

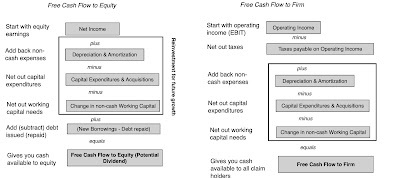

b. Foundations of Finance

I also have a 12-session foundations of finance class, where I introduce two structures that I draw on all through my classes - the financial balance sheet (as opposed to an accounting balance sheet) and a corporate life cycle. I provide an introduction to cash flows and risk, and how they play out in the time value of money, and the basics of valuing contractual cash flows (bonds), residual cash flows (equity) and contingent cash flows (options). Finally, I carve out simple (even simplistic) sessions on inflation, interest rates and exchange rate, three macro variables that we are exposed to in almost all financial analysis and valuations.

Link to Foundations class

Link to Foundations class Again, if your finance basics are solid, and you understand the link between expected inflation, interest rates and exchange rates, you can skip this class.

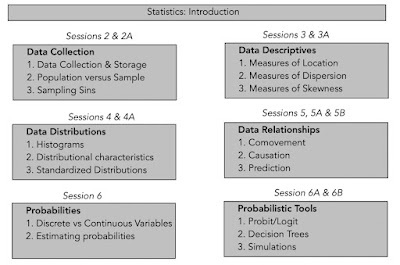

c. Statistics

The most recent addition to my class list is one on statistics, and it was motivated by the wanton misuse and misunderstanding of data that I see not only in investing, but in the rest of life. It is ironic, and perhaps telling, that our understanding of statistics seems to have hit rock bottom in the age of big data. In this class, I start by looking at data collection and data descriptives, before moving on to distributions and data relationships (correlations, covariances and regressions) and closing with probabilities and probabilistic tools.

Link to Statistics class

Link to Statistics classIf you find yourself inundated by data in financial analysis, I hope this class helps you convert data to information, and data that matters from data that distracts.

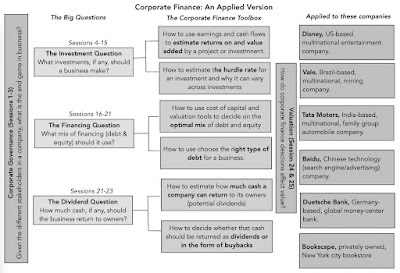

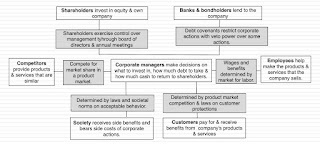

2. Corporate Finance

If the introductory classes in accounting, finance and foundations don’t exhaust you, you are welcome to my corporate finance class, which covers the first principles that govern how to run a business. The class starts with a question of what the end game should be for a business (profitability, value, social good?), and uses that endgame to cast light on the investing, financing and dividend decisions that all businesses, small or large, private or public, have to make.

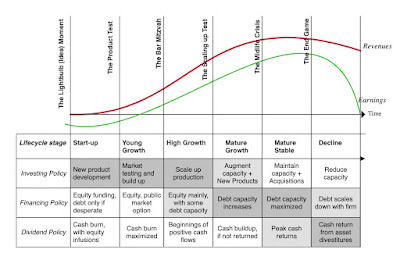

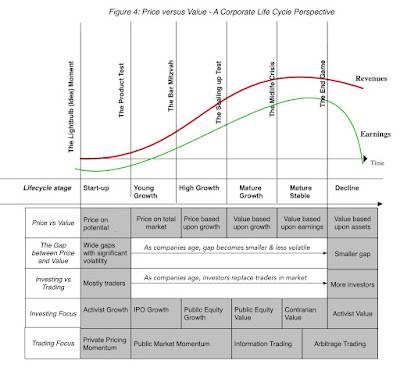

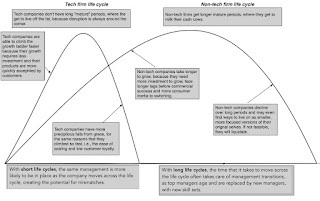

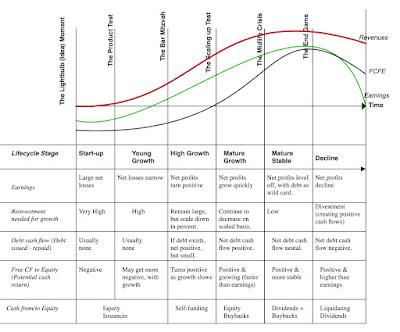

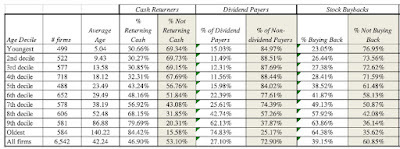

This is a big picture class, designed not for bankers and consultants, but for a much broader audience of business owners, entrepreneurs and investors. If you have struggled with why debt helps some companies and hinders others, or how stock buybacks affect shareholders, I hope that you will give this class a try. It is also a relentlessly applied class, where every concept that is introduced in class is applied on companies that range the spectrum: a multinational entertainment company facing leadership challenges (Disney), a family-group automobile company (Tata Motors), a bank with a storied past and a troubled present (Deutsche Bank), an emerging-market mining company (Vale), a Chinese search engine (Baidu) and a small privately owned bookstore in New York City. Along the way, I will use the corporate life cycle to illustrate how the corporate finance focus of a business changes as it ages, from investing (in young companies) to financing (in mature businesses) to dividends (in declining businesses):

This is a big picture class, designed not for bankers and consultants, but for a much broader audience of business owners, entrepreneurs and investors. If you have struggled with why debt helps some companies and hinders others, or how stock buybacks affect shareholders, I hope that you will give this class a try. It is also a relentlessly applied class, where every concept that is introduced in class is applied on companies that range the spectrum: a multinational entertainment company facing leadership challenges (Disney), a family-group automobile company (Tata Motors), a bank with a storied past and a troubled present (Deutsche Bank), an emerging-market mining company (Vale), a Chinese search engine (Baidu) and a small privately owned bookstore in New York City. Along the way, I will use the corporate life cycle to illustrate how the corporate finance focus of a business changes as it ages, from investing (in young companies) to financing (in mature businesses) to dividends (in declining businesses):

It will help make my case that companies that act in age-inappropriate ways (a young company that borrows large amounts, a mature company that relentlessly chases growth or a declining firm looking for reincarnation) destroy value, while making their bankers and consultants wealthy.

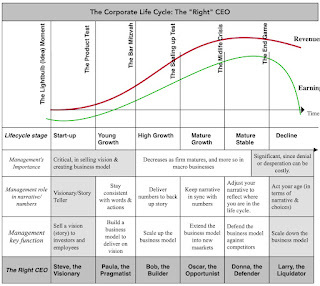

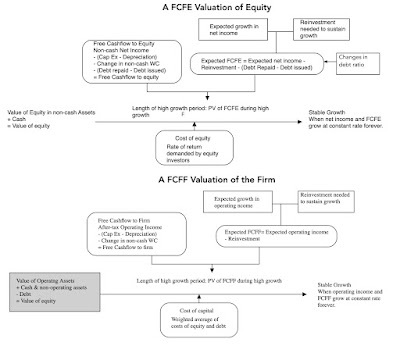

It will help make my case that companies that act in age-inappropriate ways (a young company that borrows large amounts, a mature company that relentlessly chases growth or a declining firm looking for reincarnation) destroy value, while making their bankers and consultants wealthy.3. Valuation

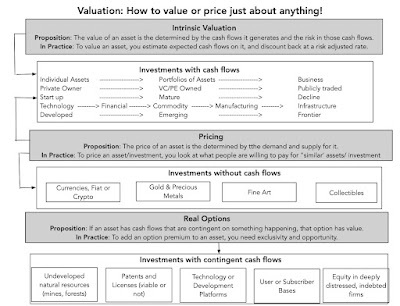

In 1986, when I taught the first semester-long valuation class at NYU, I was told that there was not enough material for a class that long. I persevered, and thirty seven years later, I think I can say, with some confidence, that I have enough material to fill a semester-long class. This is a class in search of pragmatic solutions, not purity or theory, and it is my intent is to value assets, companies and investments, not just talk about valuing them.

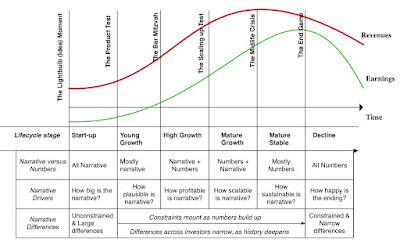

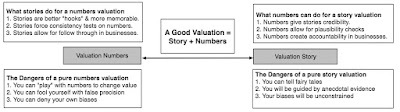

I have argued that valuation books and courses do a disservice by focusing all their attention on money-making publicly-traded companies, with long histories and mostly in developed markets, leaving readers and students with the false impression that you cannot value young companies., firms in emerging markets or private businesses. I claim, perhaps boastfully, in my first session of this class that this is a class about valuing or pricing just about anything, including private business, assets, collectibles and even cryptos. I use the corporate life cycle to talk about how the challenges in valuing and pricing companies shift as you move from start-ups to companies in decline:

As with the corporate finance class, I cast my net wide, when it comes to my audience, and while the class will help prepare you for a valuation career, as an equity research analyst or appraiser, the class is designed for anyone who has ever struggled with understanding valuation and market pricing. This may surprise you, but we spend a significant amount of time in this class talking about telling business stories that pass the “fairy tale” test and tying stories to valuation inputs, and almost no time opening and closing spreadsheets. So, whether you are a number cruncher or story teller, I think you will find something to take away from the class.

4. Investment Philosophy

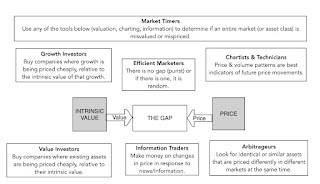

The last class that I teach, albeit only online, is one on investment philosophies, and it was born from two observing two investing realities.

The first is that notwithstanding the hundreds of books on how to beat the market and the thousands of cannot-miss trading strategies that exist on paper, there are only a handful of investors and traders who have consistently beaten the market over long periods. The second is that these consistent winners have very little in common, in terms of market beliefs and strategies, with value investors, market timers and traders in the mix. My reading of these two realities is that there is no one best investment philosophy, that works for everyone, but there is one best philosophy for you, given your personal make up and investable capital. Consequently, this class lays out a menu of investment philosophies, from short-term (day) trading to long-term value investing, from passive to active to activist investing and from stock picking to market timing, with the intent of letting you find the investment philosophy that is right for you.

As with my corporate finance and valuation classes, I argue that your choice of investment philosophy will determine where in the corporate life cycle, you will find your investments.

If you believe that markets make mistakes in valuing assets-in-place, i.e., you are a value investor, your portfolio will be composed of mature companies. In contrast, if your view is that markets make mistakes in valuing growth assets, i.e., you are a growth investor, your investments will be primarily from growth companies.

If you believe that markets make mistakes in valuing assets-in-place, i.e., you are a value investor, your portfolio will be composed of mature companies. In contrast, if your view is that markets make mistakes in valuing growth assets, i.e., you are a growth investor, your investments will be primarily from growth companies. Choices, choices, choices...

You have lives to live, work to do and families to be with, and it is unrealistic and arrogant of me to expect you to spend a large portion of your time, taking my classes. I will settle for what I can get, and offer my classes in multiple formats, tailored to different time constraints and diverse tastes.

Formats

There are three formats in which I offer my classes, though not all of the classes are available in every format.

Regular classes (Free): My corporate finance and valuation classes are taught, as semester-long classes, meeting twice a week for 80-minute sessions. While you need to be registered in the classes, as Stern students, to be able to sit in the classrooms, the sessions will be recorded and accessible by the end of the class day. You can take the class this upcoming semester, when the classes start late January 2023 and continue through May 2023, or watch the archived versions from spring 2022.

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; } ClassWebpage for classSpring 2023 (Real time)Spring 2022 (Archived) Corporate FinanceLinkLinkLink Valuation (MBA)LinkLinkLink Valuation (Undergraduate)LinkLinkLinkNote that the MBA and undergraduate valuation classes are identical in content, and you can take one or the other. If you decide to take the class, you will have access to everything that my students will have, from the slides that I use in the class, to the tests and exams that I give, with solutions that you can use to grade yourself, to the emails that I send my students on an almost daily basis. You can even do the projects (a corporate financial analysis in the corporate finance class or valuing & pricing a company in the valuation class) that are required for the classes. The downside is that this is the most time consuming of the choices, and much as I try, my 80-minute sessions cannot compete with The White Lotus for entertainment value.

Online classes (Free): If you find yourself unable to invest the time needed to take my regular classes or find the long sessions unwatchable (I don't blame you..), I have online versions of these classes that compress the 80-minute sessions into 12-15 minutes. It is a testimonial to the bloat in MBA programs that I can do this without compromising much on content, and these sessions also come with supporting material.

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Online ClassWebpage for classYouTube Playlist AccountingLinkLink Foundations of FinanceLinkLink StatisticsLinkLink Corporate FinanceLinkLink ValuationLinkLink Investment PhilosophyLinkLinkOne downside is that many of these online sessions were recorded a few years ago, and you may find no mention of valuation challenges of today, from how the COVID crisis upended value and the steep fall in FANGAM stocks this year. Another is that even if you watch every video, take every post-class test and feel that you have mastered the material, I cannot offer you any official affirmation or certification for taking the class, but on the flip side, the courses are free!

Certificate classes (Not free): If certification is what you seek, New York University offers my three main courses as certificate classes. The content is similar to that in my online classes, but the videos are more polished, the classes follow a calendar and I do have an online meetup on zoom every two weeks:

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; } Certificate ClassNYU Exec Ed LinkSemesters taught Corporate FinanceLinkFall Semester ValuationLinkFall & Spring Semesters Investment PhilosophyLinkSpring SemesterIn keeping with the adage that there is no free lunch, you will have to pay for the certification privilege, and if the price gives you sticker shock, please remember that I have no role in that pricing decision and offer a free version, with the same content.

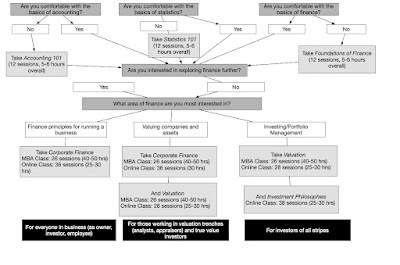

Sequencing

If you are interested but are unclear about where to start, I am reproducing a flow chart I created last year to guide you through my classes.

As you can see, the sequencing of classes depends upon your background, as well as your interests. Specifically, if you are mostly interested in running or helping to run a business, the only class that you may need is a corporate finance class, supplemented by, if necessary, one or more of the three prep classes (accounting, basic finance and statistics). If your interests lie in learning the craft of valuation, perhaps because your job requires it or because you are curious, my recommendation is that you take both the corporate finance and valuation classes. If investing is what rings your bell, the valuation class twinned with an investment philosophy class should get you to wherever you want to go.

As you can see, the sequencing of classes depends upon your background, as well as your interests. Specifically, if you are mostly interested in running or helping to run a business, the only class that you may need is a corporate finance class, supplemented by, if necessary, one or more of the three prep classes (accounting, basic finance and statistics). If your interests lie in learning the craft of valuation, perhaps because your job requires it or because you are curious, my recommendation is that you take both the corporate finance and valuation classes. If investing is what rings your bell, the valuation class twinned with an investment philosophy class should get you to wherever you want to go. Supporting Cast

Watching a video of a class is just the first step in learning. To help, I try to provide as much supporting material as I can. As you look down the list, please do not be intimidated by its length, since you may find a use for only a portion of what I offer:

Lecture Notes: The only material that I require for the students in my class are the lecture note slides that I use in the class, and the only reason I require it is to reduce the amount of note-taking during class. The slides are available as full packets for my regular classes, on the webpages for the classes (see above), but they are also available with each session as links. As you review these slides, you will note that I break every rule in creating slides, cramming in way too much information on each slide. I am sorry for doing so, but my intent is to allow these slides to be the equivalent of class notes.Post-class test: Every session of each class comes with a post-class test. These tests take about 15 minutes to do, and are a review of the material covered during the class. If you have the time, it is worth taking these tests to reaffirm what you are learning.Data: The data that I reference during the class are available in their most updated formats on my webpage, under current data, with the next update due at the start of 2023. Spreadsheets: I almost never open an excel spreadsheet during my classes and spend little time on financial modeling, but I do use my limited Excel skills, when valuing companies and doing corporate financial analysis. To save you the trouble of building spreadsheets from scratch, I leave my spreadsheets online for you to access, adapt and change.Tools videos: As I noted earlier, my classes are applied, and to provide guidance on applying what I teach to real life, I have YouTube videos on almost every application, from how to read an annual report all the way to a full company valuation.Blog Posts: If you find the material in my classes of interest, you can read my blog on Google Blogger and Substack. I don't post often, but when I do, my posts tend to focus on valuation, corporate finance and investment philosophy topics. Books: I have books on each of the topics that I teach, but you do not need any of them to get through these classes. Some of these books are obscenely over-priced, and I don't require them for any of my classes.table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Book

Publisher link

Webpage for book

Valuation

Damodaran on Valuation

Link

Link

Investment Valuation

Link

Link

The Dark Side of Valuation

Link

Link

The Little Book of Valuation

Link

Link

Narrative and Numbers

Link

Link

Corporate Finance

Corporate Finance

Link

Link

Applied Corporate Finance

Link

Link

Strategic Risk Taking

Link

Link

Investment Philosophies

Investment Philosophies

Link

Link

Investment Fables

Link

Link

All Classes

The Corporate Life Cycle

Forthcoming in 2023

Forthcoming in 2023

Group Work and Interaction

Starting on an online class is easy, but finishing the class is difficult. One obvious reason is time and commitment, and I will have to leave it to you to figure that one out, but another is that a class is more than a collection of lectures. There is a peer-group component to learning that includes class discussions and group interactions that is often absent in big online classes, leaving you not only with unanswered questions, but also missing the critical part of learning that comes from explaining concepts to, and bouncing ideas off, others in the class.

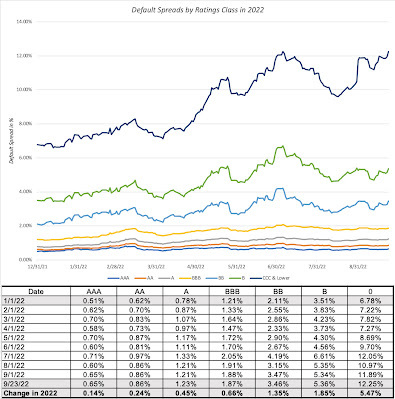

I do not have the bandwidth to be able to provide direct support to everyone taking my classes, but a few months ago, I was approached by Sebastian Marambio, who has set up a neat site called We are six, allowing people to set up groups to work with, for online classes, with apps available for Android and iOS. Once you register on the site, you can enter the class code for the class that you then proceed to create a group with others with similar time frames and compatible time zones for taking the class. Sebastian has been kind enough to set up free versions for my online classes and the links to them are below: