Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 22

July 20, 2017

Online Teaching: Promise, Pitfalls and Potential!

I am a teacher. That is how I describe myself to anyone who chooses to ask me what I do for a living. I am not a professor (sounds pedantic and pompous), definitely not an academic (how boring is that..) and don't consider myself anything more than a dilettante on almost every topic that I hold forth on. It is in pursuit of my teaching mission that I have put my regular classes online for most of the last two decades, though technology has made that sharing easier. For those of you who have read my postings before, I usually announce a few weeks ahead of every semester, the classes that I will be teaching at Stern, what each class is about and how you can access it, as I did in January with my Spring 2017 valuation and corporate finance classes. As September 2018 approaches, I was going to skip that ritual, since I will be on sabbatical next year (and if you have no idea what a sabbatical is, more on that later..) but I will be teaching, nevertheless, during the year.

Online Education

I still remember the first semester that I shared a class with an online audience was in the 1990s, when the internet was still in its infancy, we were still using dial-up modems and phones were connected to landlines. I recorded my regular classes using a VHS camcorder onto tapes, and then converted the tapes into videos of woeful quality, but with passable audio. I posted these online, but with only minimal additional material, since sharing was both time consuming and difficult to do. Needless to say, the internet has grown up and made sharing much easier, with class recordings now being made with built-in cameras in classrooms and converted to high quality videos quickly, to be watched on tablets on smart phones. Here, for instance, is my entire Spring 2017 valuation class, with links to the videos as well as almost every scrap of material that I provide for the class and even the emails I sent to the class.

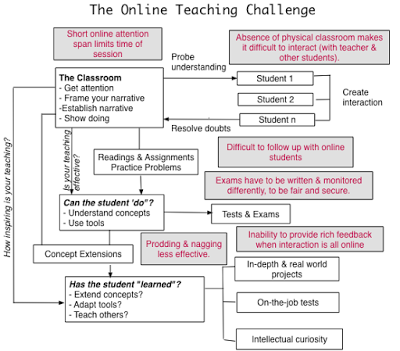

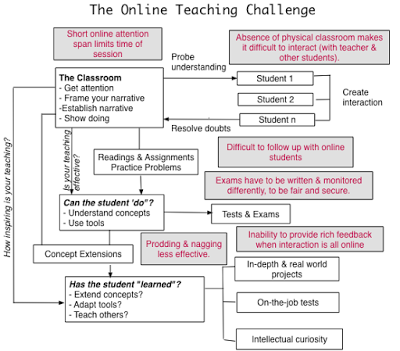

I have long believed that the traditional university model not only is ripe for, but is deserving of , disruption, saddled with legacy costs and a muddled mission. That said, the attempts by online education to upend the university model have, for the most part, had only marginal success and it is in trying to answer why that I started thinking about how we teach, and learn online. In particular, online classes have proved a imperfect substitutes for regular classes due to three shortcomings:No personal touch: This may be a reflection of my age, but there is a difference between being in a live and watching a video of the same class, no matter how well it is recorded and presented. No interaction: We forget how much of the learning in a classroom comes, not from lectures, but from interaction, not just between the teacher and students but between students, often in informal and serendipitous exchanges. With online education, the interaction, if it exists, is highly formalized and there is less learning.Tough to stay disciplined: When you were in college, and enrolled for an 8.30 am class, did you feel like not going to class? I certainly did, but what kept me going was the fact that my absence would be noticed, not just by the professor, but by other students in the class. In fact, it is that group pressure and class structure that keeps us focused on project deadlines and exam dates, with regular classes. With online classes, that discipline has to come from within, and it should be therefore no surprised that most people who start online classes never finish them. It is perhaps easiest to see the challenges and limits of online teaching by looking at what it is that makes for a good class, in person or online. In my view, the measure of good teaching is that students don't get just content (tools, techniques, models) but that they learn how to create their own content, i.e., the capacity to devise their own tools to meet their needs. In the context of a regular class, you use readings, problem sets, quizzes and exams to deliver the former (content) but the latter (learning) requires a more complex mix of classroom and informal interaction, real life projects and intellectual curiosity (and I believe that it is partly a teacher's responsibility to evoke that). The time schedule of a regular class also puts limits on how much students can procrastinate, and peer pressure, from others taking the class or working with you on assignments, serves to keep most on task.

With this framework, the challenges of teaching online become clear. You have to find ways to keep students engaged, disciplined and interactive, and you have to do it online. While there are technical solutions to each one of these challenges (great videos for engagement, a time schedule and online exams for discipline, and discussion boards for interaction), and we have come a long way in the last few years, there is still a great deal of work to be done.

Online Classes: My learning curve

My search for a better way of delivering what I teach online started about five years ago, with a simple first step. I decided to try to take each of my regular lectures, which go for 80 minutes, and see if I could compress it into a 10-12 minute slot and the results were both revealing and humbling. It was not that difficult to compress my classes, a testimonial to how much buffer I build into my regular classes to ramble and pontificate. (If you have been in one of my regular classes or watched one, you probably know that there is nothing I enjoy more than going off on a riff on a topic or news story and I think you need a few of these in a 80-minute class to keep your class engaged.) I also started developing short post-session quizzes with solutions that someone watching the class could take, to check on whether they were "getting" the session material. I organized and sequenced the sessions and you can click to see the online versions of my corporate finance, valuation and investment philosophy classes.

I was under no illusions that I had unlocked the key to online learning with these classes, and these classes had significant limitations. First, packing material densely into 10-12 minute chunks can make watching even these short sessions taxing. Second, the videos that I made (with the help of a friend who was a camera man) were lacking in bells and whistles, basic talking-head videos with slides in the background. Third, there is no personal touch or interaction, since the videos are recorded. Finally, given the number of people in each of these classes, there was no way for me to give and grade exams, look over valuations or corporate financial analysis (a key ingredients of my regular classes) or provide certification that someone had taken the class.

Valuation Certificate ClassJust over a year ago, the Stern School of Business, which is where I teach, asked me whether I would be willing to teach an online certificate class. My initial response was to say no for two reasons. First, universities always seem to operate at deficits, no matter how much revenue they collect from tuition, and I knew that Stern would extract its pound of flesh from those who took the certificate. Second, I was concerned that if I did do a certificate class, and it became a money generator, that I would be asked to remove my free online classes. Stern must have wanted to do this certificate really badly since they offered to leave my online material untouched, if I agreed to work on the certificate course. It was this assurance, in conjunction with the opportunity to have videos shot in a studio, a platform that would allow me to offer exams and quizzes and discussion boards that finally led me to yes.

So, what makes the valuation certificate class different from the free online version? It is certainly not the content, since everything I teach in the certificate class is available on my website in multiple forms, but here are a few of the primary differences:Studio-shot videos: A studio, with professionals manning cameras, sound and lights, does allow for much better videos. With the help of a talented group that knows a lot more about editing and animation than I ever will, the final versions of the online classes are better than my online videos. There are, in all, 28 video sessions, with two sessions each week, over a 14 week time period. Supporting material: In addition to the post class tests and the supporting slides, I have links to papers, spreadsheets, data, YouTube videos and blog posts that go with each session. While I am a realist and know that much of this additional material will go untouched, having it accessible will make it easier for you to use it, if you feel the urge.Live Webex sessions: Every two weeks, through the semester, we will have a live webex session, where you (if you are enrolled in the class) can ask questions, not just about material covered in the previous week's sessions but news stories and happenings. I know it is not much, but it is a step in the right direction.Announcements and outreach: I contact the students in my regular classes about once a day, but I will spare you that level of harassment. You will hear from me a couple of times every week, checking in on how you are doing and keeping you updated on the course. Exams/Quizzes: There will be three quizzes and a final exam for the class. While they will be scheduled on specific dates, you can take them any time during a 24-hour time period and if you miss a quiz, the points will be moved to the remaining quizzes. So, if life gets in the way and you are unable to take a quiz, it is not the end of the world.Valuation Project: Each person in the class can pick any company he or she want to value and value it, over the course of the class. Midway through the semester, I will offer feedback, if you want, to allow you to tweak your valuation, and at the end of the semester, it will become a significant part of your overall grade.Certificate: After the final exam and valuation are graded, you will receive a certificate for the class, if you complete the requirements. If you do exceptionally well (and you will have to leave that judgment to me), your certificate will come "with honors".There were 66 people who signed up for the pilot version of the class, which started in January 2017 and 39 completed the class in May 2017. I learned as much from my students as I hope they learned from me, and here are a few lessons. First, I discovered that the discussion boards were effective at creative interactive discussions, among the students, if I did my job and organized the boards by topic. Second, in perhaps the most rewarding part of the class, a few students, who found the material both interesting and easy to grasp, took on the role of teachers helping others deal with mechanical and conceptual questions. Since the most effective way to learn something is to explain it to someone who does not quite "get" it, I restrained myself from jumping into the discussion boards, unless absolutely necessary. Third, I was impressed with both the work that was put into and the quality of the valuations that were turned in by those who finished the class. Of the 39 who were certified at the end of the class, about a third did well enough to get "with honors" attached to the certificate. I would have been proud with any of these students in my regular classes.

This fall, Stern will be offering the valuation certificate class to a bigger audience, with a class of several hundred. The good news is that the class will be tweaked to reflect the lessons learnt from the pilot class. I will continue to do what I did for the pilot, with my webex sessions, and provide feedback and grades not only for your exams but on the companies that you choose to value. The bad news is that Stern will charge "university level" prices for the class and I will not try to tell you that it is "worth it", since that depends on your circumstances. It is entirely possible that you will decide that the price charged is too much for a certificate, that you cannot afford it, or that you are more interested in the learning than in the certification, and if so, I hope that you give the free online version of the class a shot. If you are interested in enrolling in the class, the webpage where you can start the process is here. Incidentally, a pilot version of my corporate finance class, also offered as a certificate class, will be run in Spring 2018, and if you are interested, here is that link.

My Sabbatical

I mentioned, at the start of this post, that I would be on sabbatical, and at the risk of evoking envy, I will tell you what that involves. I am taking the 2017-18 academic year (September 2017- September 2018) off from my regular teaching, as I am allowed to do every seventh year. It is an entitlement that people in most other professions don't have and I recognize how incredibly lucky I am to be able to take a paid break from work. I do have a few odds and ends to take care off during the year, including teaching the certificate classes that I just listed and writing the third edition of The Dark Side of Valuation, but I plan to spend much of the year idling my time away, thinking about nothing in particular. That may sound wasteful, but I have discovered that my mind is most productive, when I am not trying too hard to be insightful. At least, that's my hope and if it does happen, that would be great. I But then again, if I don't have a single creative thought all year, that too was meant to be!

YouTube Video

My Free Online Classes

Corporate Finance (YouTube Playlist version)Valuation (YouTube Playlist version)Investment Philosophies (YouTube Playlist version) (New version will be out at the start of 2018)Stern Certificate ClassesValuation Certificate (Fall 2017)Corporate Finance Certificate Pilot (Spring 2018)

Online Education

I still remember the first semester that I shared a class with an online audience was in the 1990s, when the internet was still in its infancy, we were still using dial-up modems and phones were connected to landlines. I recorded my regular classes using a VHS camcorder onto tapes, and then converted the tapes into videos of woeful quality, but with passable audio. I posted these online, but with only minimal additional material, since sharing was both time consuming and difficult to do. Needless to say, the internet has grown up and made sharing much easier, with class recordings now being made with built-in cameras in classrooms and converted to high quality videos quickly, to be watched on tablets on smart phones. Here, for instance, is my entire Spring 2017 valuation class, with links to the videos as well as almost every scrap of material that I provide for the class and even the emails I sent to the class.

I have long believed that the traditional university model not only is ripe for, but is deserving of , disruption, saddled with legacy costs and a muddled mission. That said, the attempts by online education to upend the university model have, for the most part, had only marginal success and it is in trying to answer why that I started thinking about how we teach, and learn online. In particular, online classes have proved a imperfect substitutes for regular classes due to three shortcomings:No personal touch: This may be a reflection of my age, but there is a difference between being in a live and watching a video of the same class, no matter how well it is recorded and presented. No interaction: We forget how much of the learning in a classroom comes, not from lectures, but from interaction, not just between the teacher and students but between students, often in informal and serendipitous exchanges. With online education, the interaction, if it exists, is highly formalized and there is less learning.Tough to stay disciplined: When you were in college, and enrolled for an 8.30 am class, did you feel like not going to class? I certainly did, but what kept me going was the fact that my absence would be noticed, not just by the professor, but by other students in the class. In fact, it is that group pressure and class structure that keeps us focused on project deadlines and exam dates, with regular classes. With online classes, that discipline has to come from within, and it should be therefore no surprised that most people who start online classes never finish them. It is perhaps easiest to see the challenges and limits of online teaching by looking at what it is that makes for a good class, in person or online. In my view, the measure of good teaching is that students don't get just content (tools, techniques, models) but that they learn how to create their own content, i.e., the capacity to devise their own tools to meet their needs. In the context of a regular class, you use readings, problem sets, quizzes and exams to deliver the former (content) but the latter (learning) requires a more complex mix of classroom and informal interaction, real life projects and intellectual curiosity (and I believe that it is partly a teacher's responsibility to evoke that). The time schedule of a regular class also puts limits on how much students can procrastinate, and peer pressure, from others taking the class or working with you on assignments, serves to keep most on task.

With this framework, the challenges of teaching online become clear. You have to find ways to keep students engaged, disciplined and interactive, and you have to do it online. While there are technical solutions to each one of these challenges (great videos for engagement, a time schedule and online exams for discipline, and discussion boards for interaction), and we have come a long way in the last few years, there is still a great deal of work to be done.

Online Classes: My learning curve

My search for a better way of delivering what I teach online started about five years ago, with a simple first step. I decided to try to take each of my regular lectures, which go for 80 minutes, and see if I could compress it into a 10-12 minute slot and the results were both revealing and humbling. It was not that difficult to compress my classes, a testimonial to how much buffer I build into my regular classes to ramble and pontificate. (If you have been in one of my regular classes or watched one, you probably know that there is nothing I enjoy more than going off on a riff on a topic or news story and I think you need a few of these in a 80-minute class to keep your class engaged.) I also started developing short post-session quizzes with solutions that someone watching the class could take, to check on whether they were "getting" the session material. I organized and sequenced the sessions and you can click to see the online versions of my corporate finance, valuation and investment philosophy classes.

I was under no illusions that I had unlocked the key to online learning with these classes, and these classes had significant limitations. First, packing material densely into 10-12 minute chunks can make watching even these short sessions taxing. Second, the videos that I made (with the help of a friend who was a camera man) were lacking in bells and whistles, basic talking-head videos with slides in the background. Third, there is no personal touch or interaction, since the videos are recorded. Finally, given the number of people in each of these classes, there was no way for me to give and grade exams, look over valuations or corporate financial analysis (a key ingredients of my regular classes) or provide certification that someone had taken the class.

Valuation Certificate ClassJust over a year ago, the Stern School of Business, which is where I teach, asked me whether I would be willing to teach an online certificate class. My initial response was to say no for two reasons. First, universities always seem to operate at deficits, no matter how much revenue they collect from tuition, and I knew that Stern would extract its pound of flesh from those who took the certificate. Second, I was concerned that if I did do a certificate class, and it became a money generator, that I would be asked to remove my free online classes. Stern must have wanted to do this certificate really badly since they offered to leave my online material untouched, if I agreed to work on the certificate course. It was this assurance, in conjunction with the opportunity to have videos shot in a studio, a platform that would allow me to offer exams and quizzes and discussion boards that finally led me to yes.

So, what makes the valuation certificate class different from the free online version? It is certainly not the content, since everything I teach in the certificate class is available on my website in multiple forms, but here are a few of the primary differences:Studio-shot videos: A studio, with professionals manning cameras, sound and lights, does allow for much better videos. With the help of a talented group that knows a lot more about editing and animation than I ever will, the final versions of the online classes are better than my online videos. There are, in all, 28 video sessions, with two sessions each week, over a 14 week time period. Supporting material: In addition to the post class tests and the supporting slides, I have links to papers, spreadsheets, data, YouTube videos and blog posts that go with each session. While I am a realist and know that much of this additional material will go untouched, having it accessible will make it easier for you to use it, if you feel the urge.Live Webex sessions: Every two weeks, through the semester, we will have a live webex session, where you (if you are enrolled in the class) can ask questions, not just about material covered in the previous week's sessions but news stories and happenings. I know it is not much, but it is a step in the right direction.Announcements and outreach: I contact the students in my regular classes about once a day, but I will spare you that level of harassment. You will hear from me a couple of times every week, checking in on how you are doing and keeping you updated on the course. Exams/Quizzes: There will be three quizzes and a final exam for the class. While they will be scheduled on specific dates, you can take them any time during a 24-hour time period and if you miss a quiz, the points will be moved to the remaining quizzes. So, if life gets in the way and you are unable to take a quiz, it is not the end of the world.Valuation Project: Each person in the class can pick any company he or she want to value and value it, over the course of the class. Midway through the semester, I will offer feedback, if you want, to allow you to tweak your valuation, and at the end of the semester, it will become a significant part of your overall grade.Certificate: After the final exam and valuation are graded, you will receive a certificate for the class, if you complete the requirements. If you do exceptionally well (and you will have to leave that judgment to me), your certificate will come "with honors".There were 66 people who signed up for the pilot version of the class, which started in January 2017 and 39 completed the class in May 2017. I learned as much from my students as I hope they learned from me, and here are a few lessons. First, I discovered that the discussion boards were effective at creative interactive discussions, among the students, if I did my job and organized the boards by topic. Second, in perhaps the most rewarding part of the class, a few students, who found the material both interesting and easy to grasp, took on the role of teachers helping others deal with mechanical and conceptual questions. Since the most effective way to learn something is to explain it to someone who does not quite "get" it, I restrained myself from jumping into the discussion boards, unless absolutely necessary. Third, I was impressed with both the work that was put into and the quality of the valuations that were turned in by those who finished the class. Of the 39 who were certified at the end of the class, about a third did well enough to get "with honors" attached to the certificate. I would have been proud with any of these students in my regular classes.

This fall, Stern will be offering the valuation certificate class to a bigger audience, with a class of several hundred. The good news is that the class will be tweaked to reflect the lessons learnt from the pilot class. I will continue to do what I did for the pilot, with my webex sessions, and provide feedback and grades not only for your exams but on the companies that you choose to value. The bad news is that Stern will charge "university level" prices for the class and I will not try to tell you that it is "worth it", since that depends on your circumstances. It is entirely possible that you will decide that the price charged is too much for a certificate, that you cannot afford it, or that you are more interested in the learning than in the certification, and if so, I hope that you give the free online version of the class a shot. If you are interested in enrolling in the class, the webpage where you can start the process is here. Incidentally, a pilot version of my corporate finance class, also offered as a certificate class, will be run in Spring 2018, and if you are interested, here is that link.

My Sabbatical

I mentioned, at the start of this post, that I would be on sabbatical, and at the risk of evoking envy, I will tell you what that involves. I am taking the 2017-18 academic year (September 2017- September 2018) off from my regular teaching, as I am allowed to do every seventh year. It is an entitlement that people in most other professions don't have and I recognize how incredibly lucky I am to be able to take a paid break from work. I do have a few odds and ends to take care off during the year, including teaching the certificate classes that I just listed and writing the third edition of The Dark Side of Valuation, but I plan to spend much of the year idling my time away, thinking about nothing in particular. That may sound wasteful, but I have discovered that my mind is most productive, when I am not trying too hard to be insightful. At least, that's my hope and if it does happen, that would be great. I But then again, if I don't have a single creative thought all year, that too was meant to be!

YouTube Video

My Free Online Classes

Corporate Finance (YouTube Playlist version)Valuation (YouTube Playlist version)Investment Philosophies (YouTube Playlist version) (New version will be out at the start of 2018)Stern Certificate ClassesValuation Certificate (Fall 2017)Corporate Finance Certificate Pilot (Spring 2018)

Published on July 20, 2017 06:58

July 13, 2017

The Dark Side of Globalization: An Update on Country Risk!

The inexorable push towards globalization has stalled in the last few years, but the change it has created is irreversible. The largest companies in the world are multinationals, deriving large portions of their revenues from outside domestic markets, and even the most inward looking investors are dependent upon global economies for their returns. As a consequence, measuring and incorporating country risk into decision making is a requirement in both corporate finance and valuation. It is in pursuit of that objective that I revisit the country risk issue twice every year, once at the start of the year and once mid-year, at which time I also update a paper that I have on the topic, that you are welcome to read or browse or ignore.

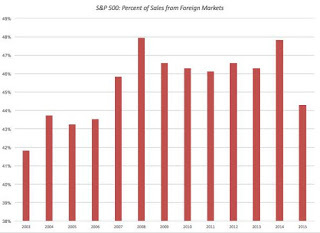

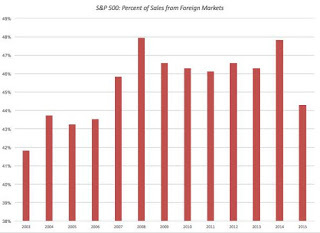

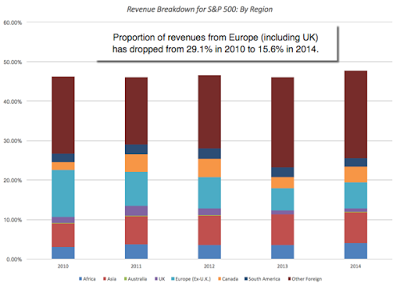

The Globalization of CompaniesThere are some investors, especially in the United States, who feel that they can avoid dealing with risk in other countries, by investing in just US stocks. That is a delusion, though, because a company that is incorporated and traded in the United States can derive a significant portion of its revenues and earnings from outside the country. In 2015, the companies in the S&P 500, the largest market cap stocks in the US, derived approximately 44% of its revenues from foreign markets, down from 48% in the prior year. Source: S&PThe composition of foreign sales is also changing, though gradually, over time, shifting away from the UK and Europe to emerging markets, as evidenced in the graph below:

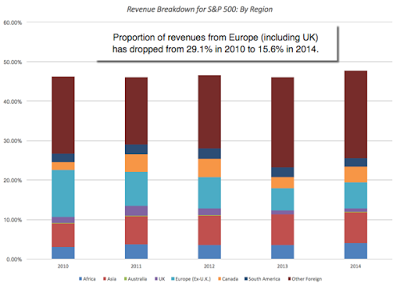

Source: S&PThe composition of foreign sales is also changing, though gradually, over time, shifting away from the UK and Europe to emerging markets, as evidenced in the graph below:

Source: S&PLest you feel that this graph is skewed by the biggest companies in the index, 239 of the 500 companies in the index reported that foreign sales represented between 15% and 85% of their total sales and 13 companies reported that more than 85% of their sales came from outside the US. In 2014, two companies, Accenture and Seagate Technology, reported that all their sales were foreign, making them US companies only in name. This phenomenon is not restricted to US companies, as the largest companies in most markets exhibit similar characteristics. While we can debate whether these trend lines are good or bad for consumers and investors, the consequences are real:Fraying link to domestic economies: For decades, the conventional wisdom has been that the stock market in a country is closely tied to how well the economy of that country is doing. That relationship has been weakened by globalization and equity market performance around the world is disconnecting from domestic economic growth. Taking the US as an example, consider that equity markets in the US have been on a bull run, with indices up 170% to 200%, cumulatively since 2009, even as the US economy has been posting anemic growth.Central Banking power is diluted: In the decades since the great depression, we have to come to accept that central banks can use the policy levers that they have at their disposal to move long term interest rates and to strongly influence overall economic growth, but that power too has been reduced by globalization and its unpredictable flows. It should come as no surprise then that the frantic efforts of central banks\ in the US, Europe and Japan, in the last decade, to use the interest rate lever to pump up economic growth or to alter the trajectory of long term interest rates have failed.Taxing questions: When writing tax code, governments have generally assumed that companies incorporated in their domiciles have little choice but to accede to tax laws eventually and pay their share of taxes. While companies have historically played the tax game by delaying and deferring taxes due, their global reach now seems to have shifted the balance of power in their direction. In the United States, in particular, where the government has tried to tax companies on their global income, this push back has taken the form of trapped cash, as companies hold trillions of dollars of cash on foreign shores, and inversions, where some US companies have chosen to move their home base to more favorable tax locales.Declining cross-market correlations: As companies globalize, it should come as no surprise that the correlations across global equity markets have climbed, with two immediate consequences. The first is that global crises are now an almost annual occurrence rather than uncommon surprises, as pain in one market quickly spreads across the world. The second is that the salve of geographic diversification, long touted as protection against domestic market shocks, provides far less protection than it used to.The bottom line is that there is no place to hide from country risk, and as with any other type of risk, it is best to face up to it and deal with it explicitly.

Source: S&PLest you feel that this graph is skewed by the biggest companies in the index, 239 of the 500 companies in the index reported that foreign sales represented between 15% and 85% of their total sales and 13 companies reported that more than 85% of their sales came from outside the US. In 2014, two companies, Accenture and Seagate Technology, reported that all their sales were foreign, making them US companies only in name. This phenomenon is not restricted to US companies, as the largest companies in most markets exhibit similar characteristics. While we can debate whether these trend lines are good or bad for consumers and investors, the consequences are real:Fraying link to domestic economies: For decades, the conventional wisdom has been that the stock market in a country is closely tied to how well the economy of that country is doing. That relationship has been weakened by globalization and equity market performance around the world is disconnecting from domestic economic growth. Taking the US as an example, consider that equity markets in the US have been on a bull run, with indices up 170% to 200%, cumulatively since 2009, even as the US economy has been posting anemic growth.Central Banking power is diluted: In the decades since the great depression, we have to come to accept that central banks can use the policy levers that they have at their disposal to move long term interest rates and to strongly influence overall economic growth, but that power too has been reduced by globalization and its unpredictable flows. It should come as no surprise then that the frantic efforts of central banks\ in the US, Europe and Japan, in the last decade, to use the interest rate lever to pump up economic growth or to alter the trajectory of long term interest rates have failed.Taxing questions: When writing tax code, governments have generally assumed that companies incorporated in their domiciles have little choice but to accede to tax laws eventually and pay their share of taxes. While companies have historically played the tax game by delaying and deferring taxes due, their global reach now seems to have shifted the balance of power in their direction. In the United States, in particular, where the government has tried to tax companies on their global income, this push back has taken the form of trapped cash, as companies hold trillions of dollars of cash on foreign shores, and inversions, where some US companies have chosen to move their home base to more favorable tax locales.Declining cross-market correlations: As companies globalize, it should come as no surprise that the correlations across global equity markets have climbed, with two immediate consequences. The first is that global crises are now an almost annual occurrence rather than uncommon surprises, as pain in one market quickly spreads across the world. The second is that the salve of geographic diversification, long touted as protection against domestic market shocks, provides far less protection than it used to.The bottom line is that there is no place to hide from country risk, and as with any other type of risk, it is best to face up to it and deal with it explicitly.

Country Risk - Default Risk MeasuresThe simplest and most easily measured country risk is the risk of sovereign default. When countries default on their obligations, it is not just the government that feels the pain but companies, consumers and investors do, as well.

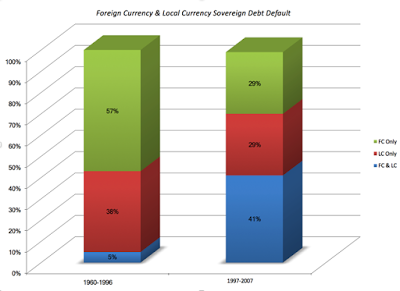

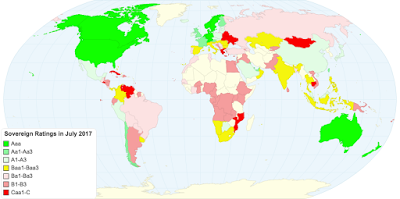

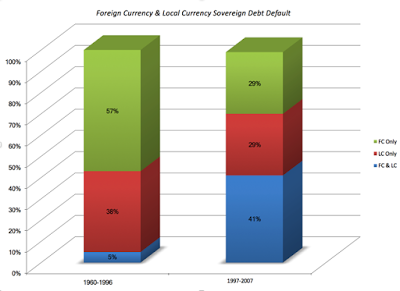

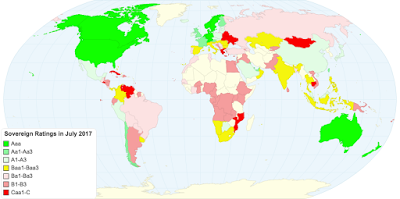

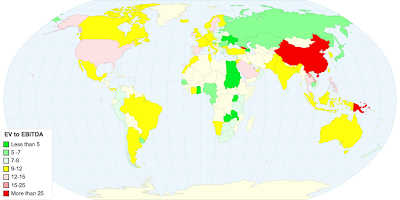

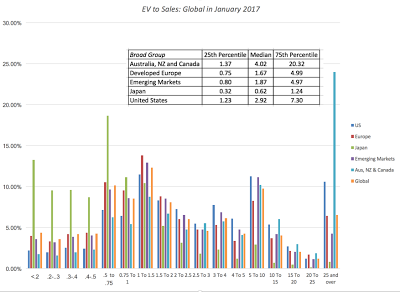

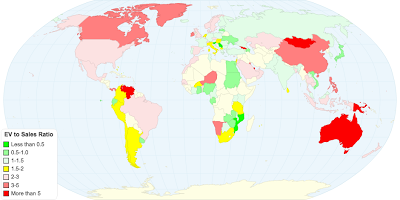

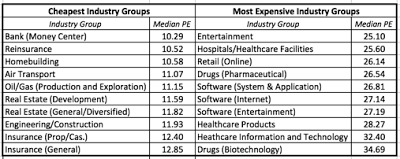

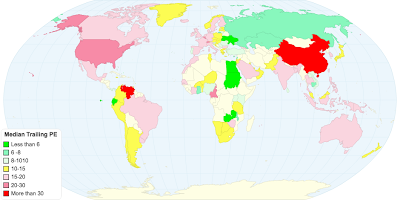

Sovereign Default: Frequency and ConsequencesGovernments borrow money, both from their own citizens and from foreign entities, and they sometimes borrow too much. Some of these government default, not only on their foreign currency debt but also on their local currency debt, with the latter having become more common over time: Source: Fitch RatingsYou may be puzzled by local currency debt defaults, since governments do have the capacity to print more of their own currency, but faced with a choice between defaulting or debasing their currencies, many governments choose the latter. When default occurs, the immediate pain is felt by the government and lenders, the former because it loses the capacity to borrow more, and the latter because they don't get paid., but there is collateral damage:Capital Market Turmoil: Liquidity dries up, as investors withdraw from equity and bond markets, making it more difficult for private enterprises in the defaulting country to raise funds for projects and resulting in sharp price drops in both bond and stock markets.Real growth: Sovereign defaults are generally followed by economic recessions, as consumers hold back on spending and firms are reluctant to commit resources to long-term investments.Political Instability: Default can also strike a blow to the national psyche, which in turn can put the leadership class at risk. The wave of defaults that swept through Europe in the 1930s, with Germany, Austria, Hungary and Italy all falling victims, allowed for the rise of the Nazis and set the stage for the Second World War. In Latin America, defaults and coups have gone hand in hand for much of the last two centuries.Sovereign RatingsThe most accessible measures of sovereign default risk are sovereign ratings, with S&P, Moody's and Fitch all providing both local currency and foreign currency ratings for most countries around the world. While there are many who mistrust these ratings, they are widely used as proxies of country risk and changes in ratings, especially down grades, are news worthy and affect markets. The process and metrics used to arrive at the ratings are described more fully here and here but the picture below summarizes the sovereign ratings assigned to countries in July 2017 and the data can be downloaded at this link:

Source: Fitch RatingsYou may be puzzled by local currency debt defaults, since governments do have the capacity to print more of their own currency, but faced with a choice between defaulting or debasing their currencies, many governments choose the latter. When default occurs, the immediate pain is felt by the government and lenders, the former because it loses the capacity to borrow more, and the latter because they don't get paid., but there is collateral damage:Capital Market Turmoil: Liquidity dries up, as investors withdraw from equity and bond markets, making it more difficult for private enterprises in the defaulting country to raise funds for projects and resulting in sharp price drops in both bond and stock markets.Real growth: Sovereign defaults are generally followed by economic recessions, as consumers hold back on spending and firms are reluctant to commit resources to long-term investments.Political Instability: Default can also strike a blow to the national psyche, which in turn can put the leadership class at risk. The wave of defaults that swept through Europe in the 1930s, with Germany, Austria, Hungary and Italy all falling victims, allowed for the rise of the Nazis and set the stage for the Second World War. In Latin America, defaults and coups have gone hand in hand for much of the last two centuries.Sovereign RatingsThe most accessible measures of sovereign default risk are sovereign ratings, with S&P, Moody's and Fitch all providing both local currency and foreign currency ratings for most countries around the world. While there are many who mistrust these ratings, they are widely used as proxies of country risk and changes in ratings, especially down grades, are news worthy and affect markets. The process and metrics used to arrive at the ratings are described more fully here and here but the picture below summarizes the sovereign ratings assigned to countries in July 2017 and the data can be downloaded at this link:

Link for live mapThe last decade has turned the spotlight on both the pluses and minuses of ratings. On the plus side, as the ratings agencies are quick to point out, ratings and default spreads are highly correlated. On the minus side, ratings agencies seem to have regional biases (under rating emerging markets and over rating developed markets) and are slow to change ratings.

Link for live mapThe last decade has turned the spotlight on both the pluses and minuses of ratings. On the plus side, as the ratings agencies are quick to point out, ratings and default spreads are highly correlated. On the minus side, ratings agencies seem to have regional biases (under rating emerging markets and over rating developed markets) and are slow to change ratings.

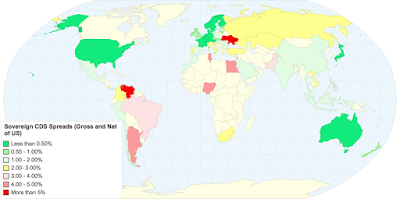

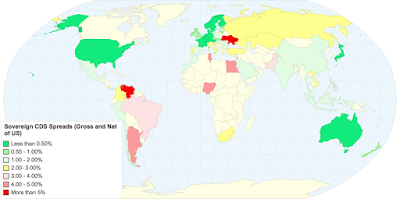

Sovereign CDS SpreadsIn the last decade, we have seen the growth of a market-based measure of default risk in the Credit Default Swap (CDS) market, where you can buy insurance against sovereign default by buying a sovereign CDS. Since the insurance is priced on annual basis, the price of a sovereign CDS becomes a market measure of the default spread for that country. In July 2017, there were 68 countries with sovereign CDS and the picture below captures the pricing (with the data available for download at this link). One of the limitations of the CDS market is that there is still credit risk in the market and to allow for the upward bias this creates in the spreads, I compute a netted version of the spread, where I net out the US sovereign CDS spread of 0.34% from each country's CDS spread. Link for live mapTo provide a comparison between the CDS and sovereign rating measures of default risk, let me offer two example. The sovereign CDS for Brazil on July 1, 2017, was 3.46%. On the same day, Moody rated Brazil at Ba2, with an estimated default spread of 3.17%, close to the CDS value. For India, the sovereign CDS spread on July 1, 2017, was 2.42%, very close to the default spread of 2.32% that would have been assigned to it based upon its Baa3 rating.

Link for live mapTo provide a comparison between the CDS and sovereign rating measures of default risk, let me offer two example. The sovereign CDS for Brazil on July 1, 2017, was 3.46%. On the same day, Moody rated Brazil at Ba2, with an estimated default spread of 3.17%, close to the CDS value. For India, the sovereign CDS spread on July 1, 2017, was 2.42%, very close to the default spread of 2.32% that would have been assigned to it based upon its Baa3 rating.

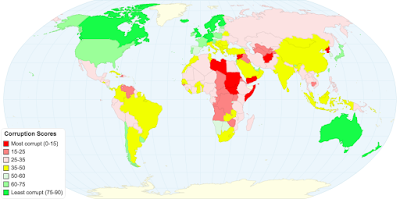

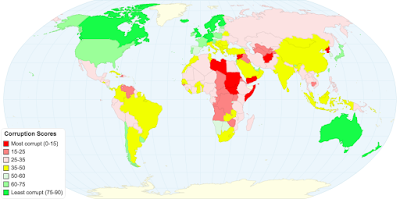

Country Risk - Institutional RiskWhen investing in a company, the sovereign default risk is just one of many risks that you have to factor into your decision making. In fact, default risk may pale in comparison to risks you face because of the institutional structure, or lack of it, in a country. At the risk of picking at scabs, here is my shot at assessing some of these risks.1. CorruptionMuch as we like to inveigh against its consequences, corruption is not just part and parcel of operating in some parts of the world, but it takes on the role of an implicit tax, one that is paid to free agents, acting in their own interests, rather than to governments. Transparency International, an entity that measures corruption risk around the world, estimates corruption scores for individual countries and heir findings for 2016 are summarized in the picture below. To see where a country falls on the corruption continuum, you can either click on the live link below the picture or download the data by country by clicking here.

Link to live mapWhile it is easy to fall back on cultural stereotypes to explain differences across countries, there is a high correlation between economic well being and corruption. Thus, while much of Latin America scores low on the corruption, Chile and Uruguay rank much higher, as do South Korea and Japan in Asia.

Link to live mapWhile it is easy to fall back on cultural stereotypes to explain differences across countries, there is a high correlation between economic well being and corruption. Thus, while much of Latin America scores low on the corruption, Chile and Uruguay rank much higher, as do South Korea and Japan in Asia.

2. Legal ProtectionsEven the very best investments are only as good as the legal protections that you have as an investor, against expropriation or theft, which is why the property right protections rank high on investor wish lists. To measure the strength of property rights, I turned to the International Property Rights Index (IPRI), and report the scores they assigned in their most recent update in 2016, to countries in the picture below. You can click on the live link below the picture or download the data here.

Link to live mapEurope, North America, Japan and Australia all score high on property rights, but the hopeful sign is that index itself has seen increasing respect for property rights across time and Venezuela and Myanmar are now more the exception, than the rule.

Link to live mapEurope, North America, Japan and Australia all score high on property rights, but the hopeful sign is that index itself has seen increasing respect for property rights across time and Venezuela and Myanmar are now more the exception, than the rule.

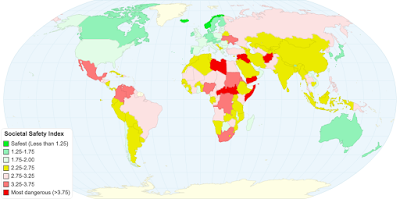

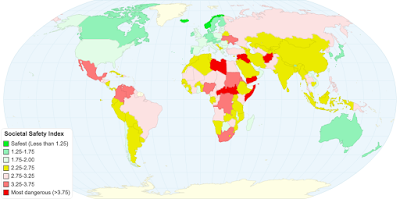

3. Risk of violenceIt is difficult to do business, when you have bullets whizzing by and bombs going off around you. Holding all else constant, you would prefer to operate in parts of the world that are safer rather than riskier. To measure exposure to violence, I again turn to an external entity, Vision of Humanity, and reproduce their Global Peace Index in the picture below (with link to live map and to data):

Link to live mapIn keeping with the adage that when it rains, it pours, the countries that are most susceptible to corruption and have weak property rights also seem to be most exposed to physical violence.

Link to live mapIn keeping with the adage that when it rains, it pours, the countries that are most susceptible to corruption and have weak property rights also seem to be most exposed to physical violence.

Country Risk - Equity RiskAs you can see, there are multiple dimensions on which you can measure country risk, leading to different scores and rankings. As an investor in the country, you are exposed to all of these risks, albeit to varying degrees, and you have to consider all these risks in making decisions. Consequently, you would like (a) a composite measure of risk that (b) you can convert into a metric that easily fits into your investment framework.

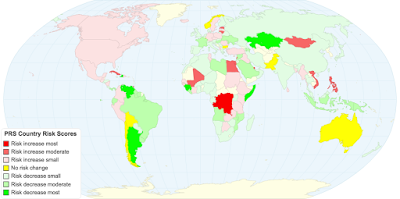

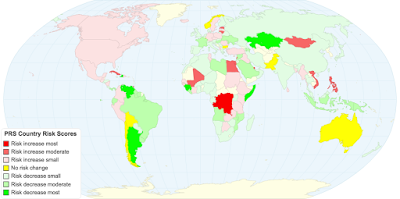

1. Country Risk ScoresThere are several services that provide composite measures of country risk, including the Economist, Euromoney and Political Risk Services (PRS). These country risk measures take the form of numerical scores, and in the heat map below, I report the change in the PRS country risk score between July 2016 and July 2017 and categorize countries based on the direction and magnitude of the change. Here, as in the prior pictures, you can see the PRS scores and the change, by country, by either clicking on the live map link below the picture or download the data by clicking here). Link for live mapBased on the PRS scores, the vast majority of emerging markets became safer during the time period between July 2016 and July 2017, with the biggest improvements in Latin America and Asia. The North American countries saw risk go up, as did pockets of Africa and South East Asia. The problem with country risk scores, no matter how well they are measured, is that they do not fit a standardized framework. Just to provide an illustration, PRS scores are low for risky countries and high for safe countries, whereas the Economist risk scores are high for risky countries and low for safe countries.

Link for live mapBased on the PRS scores, the vast majority of emerging markets became safer during the time period between July 2016 and July 2017, with the biggest improvements in Latin America and Asia. The North American countries saw risk go up, as did pockets of Africa and South East Asia. The problem with country risk scores, no matter how well they are measured, is that they do not fit a standardized framework. Just to provide an illustration, PRS scores are low for risky countries and high for safe countries, whereas the Economist risk scores are high for risky countries and low for safe countries.

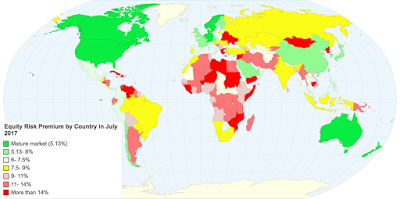

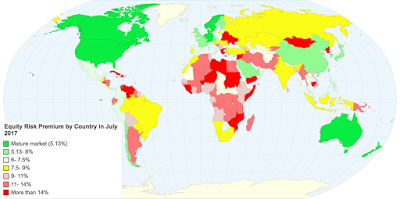

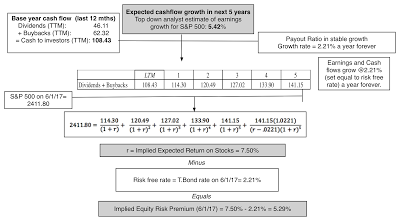

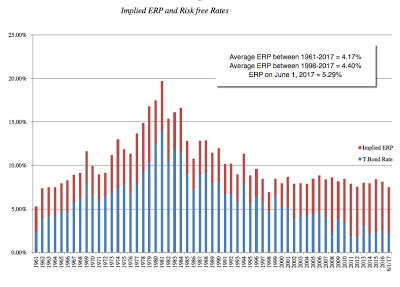

3. Equity Risk PremiumsTo incorporate and adjust for country risk into investing and valuation, I try to estimate the equity risk premiums for country, with riskier countries having higher equity risk premiums. I start with the implied equity risk premium for the US, which I estimate to be 5.13% at the start of July 2017 as my mature market premium and add to it a scaled up version of the default spread (based upon the rating); the scaling factor of 1.15 is based upon the relative volatility of emerging market equities versus bonds. You can see a more detailed description of the process in the paper that is linked at the end of this post. You can look up the equity risk premium for an individual country by clicking on the live map link or download the data by clicking here. Link for live mapThese equity risk premiums are central to how I deal with country risk in valuation, as I will explain in the last section of this post.

Link for live mapThese equity risk premiums are central to how I deal with country risk in valuation, as I will explain in the last section of this post.

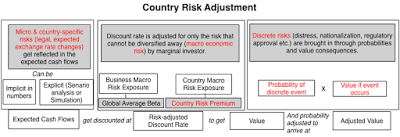

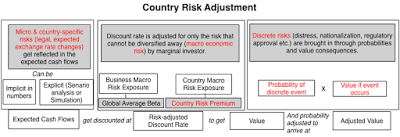

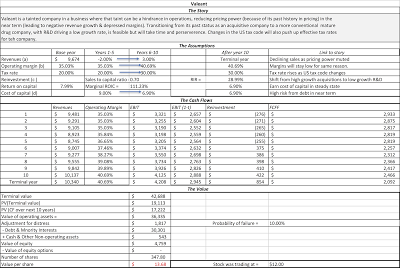

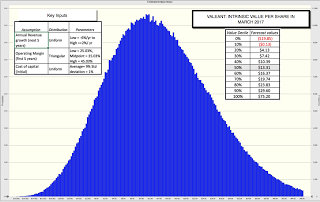

Closing the LoopWhen valuing companies that have substantial exposure to country risk, it is easy to get overwhelmed by the variety of risks. To keep the process under your control, you should start by breaking country risk into three buckets: risk that is specific just to that country, risk that is macro/global and discrete risks that are potentially catastrophic (such as nationalization or terrorism). Each has a place in valuation, with country specific risks incorporated into expected cash flows, macro economic risks in the discount rate and discrete risks in a post-valuation adjustment.

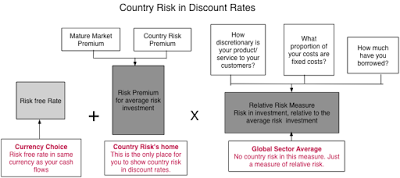

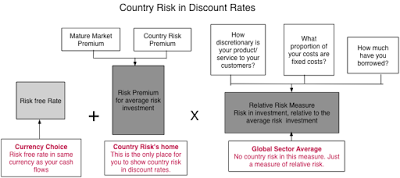

1. Adjusting discount ratesThe key to a clean country risk adjustment, when estimating discount rates, is to make sure that you do not double or even triple count it. With the cost of equity for a company, for instance, where there are only three inputs that drive the cost, it is only the equity risk premium that should be conduit for country risk (hence explaining my earlier focus on equity risk premiums, by country). The risk free rate is a function of the currency that you choose to do your valuation in and the relative risk measure (or beta, if that is how you choose to measure it) should be determined by the business or businesses that the company operates in.

If you are discounting the composite cash flows of a multinational company, the equity risk premium should be a weighted average of the equity risk premiums of the countries that the company operates in, with the weights based on revenues or operating assets. If you are valuing just the operations in one country, you would use the equity risk premium just for that country.

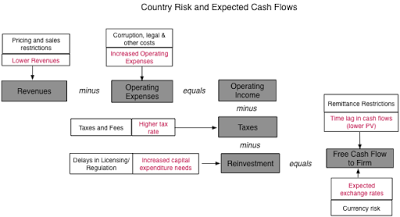

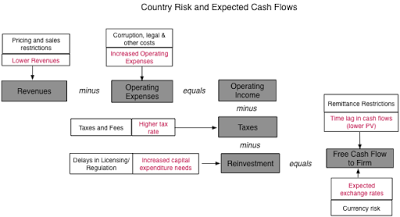

2. Expected cash flowsWith risks that are specific to a country, it is better to incorporate the risks into the expected cash flows. Thus, if a country is rife with corruption, you could treat the resulting costs as part of operating expenses, reducing profits and cash flows. When legal and regulatory delays are a feature of business in a country, you can build in the delay as lags between investing and operations. When violence (from terrorism or war) is part and parcel of operations, you may want to include a cost of insuring against the risk in your cash flows.

None of these adjustments are easy to make, but it is worth remembering that incorporating the risk into your cash flows is not risk adjusting the cash flow, since the latter requires replacing the expected cash flow with a certainty equivalent one. Where does currency risk play out? When converting cash flows from one currency (foreign) to another (domestic), you should bring in expected devaluation or revaluation into expected exchange rates. If you want to hedge exchange rate risk, you can incorporate the cost of heeding into your cash flows but it is not clear that you should be adjusting discount rates for that risk, since investors can diversify it away.

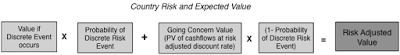

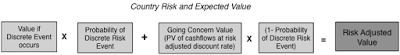

3. Post-Valuation AdjustmentThere are some risks that are rare, but if they occur, can be devastating, at least for investors in a business. Included in this grouping would be the risk of nationalization and terrorism. These risks cannot be incorporated easily into discount rates and adjusting expected cash flows in a going concern valuation (DCF) for risk that a company will be nationalized or will not survive is messy.

Thus, to estimate the effect that nationalization risk will have on the value of a business, you will have to assess the probability that the business will be nationalized and the value that you will receive as owners of the business, in the event of nationalization.

Danger and OpportunityOne of my favorite definitions of risk is the Chinese symbol for it, a combination of the symbols for danger and opportunity. 風險With risky emerging markets, this comes into , I am reminded that to have one (opportunity), I have to be willing to live the other (danger). Blindly ignoring these markets, as some conservative developed market companies are inclined to do, because there is danger will lead to stagnation, but blindly jumping into them, drawn by opportunity, will cause implosions. The essence of risk management is to measure the danger in markets and then gauge whether the opportunities are sufficient to compensate you for the dangers. That is what I hope that I have laid the foundations for, in this post.

YouTube Video

Attachment

Country Risk: Determinants, Measures and Implications - The 2017 EditionData LinksSovereign Ratings - July 2017Sovereign CDS Spreads - July 2017Corruption Scores - July 2017Property Rights Index - July 2017Peace/Violence Index - July 2017PRS Score Groupings - July 2017Equity Risk Premiums - July 2017

The Globalization of CompaniesThere are some investors, especially in the United States, who feel that they can avoid dealing with risk in other countries, by investing in just US stocks. That is a delusion, though, because a company that is incorporated and traded in the United States can derive a significant portion of its revenues and earnings from outside the country. In 2015, the companies in the S&P 500, the largest market cap stocks in the US, derived approximately 44% of its revenues from foreign markets, down from 48% in the prior year.

Source: S&PThe composition of foreign sales is also changing, though gradually, over time, shifting away from the UK and Europe to emerging markets, as evidenced in the graph below:

Source: S&PThe composition of foreign sales is also changing, though gradually, over time, shifting away from the UK and Europe to emerging markets, as evidenced in the graph below:

Source: S&PLest you feel that this graph is skewed by the biggest companies in the index, 239 of the 500 companies in the index reported that foreign sales represented between 15% and 85% of their total sales and 13 companies reported that more than 85% of their sales came from outside the US. In 2014, two companies, Accenture and Seagate Technology, reported that all their sales were foreign, making them US companies only in name. This phenomenon is not restricted to US companies, as the largest companies in most markets exhibit similar characteristics. While we can debate whether these trend lines are good or bad for consumers and investors, the consequences are real:Fraying link to domestic economies: For decades, the conventional wisdom has been that the stock market in a country is closely tied to how well the economy of that country is doing. That relationship has been weakened by globalization and equity market performance around the world is disconnecting from domestic economic growth. Taking the US as an example, consider that equity markets in the US have been on a bull run, with indices up 170% to 200%, cumulatively since 2009, even as the US economy has been posting anemic growth.Central Banking power is diluted: In the decades since the great depression, we have to come to accept that central banks can use the policy levers that they have at their disposal to move long term interest rates and to strongly influence overall economic growth, but that power too has been reduced by globalization and its unpredictable flows. It should come as no surprise then that the frantic efforts of central banks\ in the US, Europe and Japan, in the last decade, to use the interest rate lever to pump up economic growth or to alter the trajectory of long term interest rates have failed.Taxing questions: When writing tax code, governments have generally assumed that companies incorporated in their domiciles have little choice but to accede to tax laws eventually and pay their share of taxes. While companies have historically played the tax game by delaying and deferring taxes due, their global reach now seems to have shifted the balance of power in their direction. In the United States, in particular, where the government has tried to tax companies on their global income, this push back has taken the form of trapped cash, as companies hold trillions of dollars of cash on foreign shores, and inversions, where some US companies have chosen to move their home base to more favorable tax locales.Declining cross-market correlations: As companies globalize, it should come as no surprise that the correlations across global equity markets have climbed, with two immediate consequences. The first is that global crises are now an almost annual occurrence rather than uncommon surprises, as pain in one market quickly spreads across the world. The second is that the salve of geographic diversification, long touted as protection against domestic market shocks, provides far less protection than it used to.The bottom line is that there is no place to hide from country risk, and as with any other type of risk, it is best to face up to it and deal with it explicitly.

Source: S&PLest you feel that this graph is skewed by the biggest companies in the index, 239 of the 500 companies in the index reported that foreign sales represented between 15% and 85% of their total sales and 13 companies reported that more than 85% of their sales came from outside the US. In 2014, two companies, Accenture and Seagate Technology, reported that all their sales were foreign, making them US companies only in name. This phenomenon is not restricted to US companies, as the largest companies in most markets exhibit similar characteristics. While we can debate whether these trend lines are good or bad for consumers and investors, the consequences are real:Fraying link to domestic economies: For decades, the conventional wisdom has been that the stock market in a country is closely tied to how well the economy of that country is doing. That relationship has been weakened by globalization and equity market performance around the world is disconnecting from domestic economic growth. Taking the US as an example, consider that equity markets in the US have been on a bull run, with indices up 170% to 200%, cumulatively since 2009, even as the US economy has been posting anemic growth.Central Banking power is diluted: In the decades since the great depression, we have to come to accept that central banks can use the policy levers that they have at their disposal to move long term interest rates and to strongly influence overall economic growth, but that power too has been reduced by globalization and its unpredictable flows. It should come as no surprise then that the frantic efforts of central banks\ in the US, Europe and Japan, in the last decade, to use the interest rate lever to pump up economic growth or to alter the trajectory of long term interest rates have failed.Taxing questions: When writing tax code, governments have generally assumed that companies incorporated in their domiciles have little choice but to accede to tax laws eventually and pay their share of taxes. While companies have historically played the tax game by delaying and deferring taxes due, their global reach now seems to have shifted the balance of power in their direction. In the United States, in particular, where the government has tried to tax companies on their global income, this push back has taken the form of trapped cash, as companies hold trillions of dollars of cash on foreign shores, and inversions, where some US companies have chosen to move their home base to more favorable tax locales.Declining cross-market correlations: As companies globalize, it should come as no surprise that the correlations across global equity markets have climbed, with two immediate consequences. The first is that global crises are now an almost annual occurrence rather than uncommon surprises, as pain in one market quickly spreads across the world. The second is that the salve of geographic diversification, long touted as protection against domestic market shocks, provides far less protection than it used to.The bottom line is that there is no place to hide from country risk, and as with any other type of risk, it is best to face up to it and deal with it explicitly.Country Risk - Default Risk MeasuresThe simplest and most easily measured country risk is the risk of sovereign default. When countries default on their obligations, it is not just the government that feels the pain but companies, consumers and investors do, as well.

Sovereign Default: Frequency and ConsequencesGovernments borrow money, both from their own citizens and from foreign entities, and they sometimes borrow too much. Some of these government default, not only on their foreign currency debt but also on their local currency debt, with the latter having become more common over time:

Source: Fitch RatingsYou may be puzzled by local currency debt defaults, since governments do have the capacity to print more of their own currency, but faced with a choice between defaulting or debasing their currencies, many governments choose the latter. When default occurs, the immediate pain is felt by the government and lenders, the former because it loses the capacity to borrow more, and the latter because they don't get paid., but there is collateral damage:Capital Market Turmoil: Liquidity dries up, as investors withdraw from equity and bond markets, making it more difficult for private enterprises in the defaulting country to raise funds for projects and resulting in sharp price drops in both bond and stock markets.Real growth: Sovereign defaults are generally followed by economic recessions, as consumers hold back on spending and firms are reluctant to commit resources to long-term investments.Political Instability: Default can also strike a blow to the national psyche, which in turn can put the leadership class at risk. The wave of defaults that swept through Europe in the 1930s, with Germany, Austria, Hungary and Italy all falling victims, allowed for the rise of the Nazis and set the stage for the Second World War. In Latin America, defaults and coups have gone hand in hand for much of the last two centuries.Sovereign RatingsThe most accessible measures of sovereign default risk are sovereign ratings, with S&P, Moody's and Fitch all providing both local currency and foreign currency ratings for most countries around the world. While there are many who mistrust these ratings, they are widely used as proxies of country risk and changes in ratings, especially down grades, are news worthy and affect markets. The process and metrics used to arrive at the ratings are described more fully here and here but the picture below summarizes the sovereign ratings assigned to countries in July 2017 and the data can be downloaded at this link:

Source: Fitch RatingsYou may be puzzled by local currency debt defaults, since governments do have the capacity to print more of their own currency, but faced with a choice between defaulting or debasing their currencies, many governments choose the latter. When default occurs, the immediate pain is felt by the government and lenders, the former because it loses the capacity to borrow more, and the latter because they don't get paid., but there is collateral damage:Capital Market Turmoil: Liquidity dries up, as investors withdraw from equity and bond markets, making it more difficult for private enterprises in the defaulting country to raise funds for projects and resulting in sharp price drops in both bond and stock markets.Real growth: Sovereign defaults are generally followed by economic recessions, as consumers hold back on spending and firms are reluctant to commit resources to long-term investments.Political Instability: Default can also strike a blow to the national psyche, which in turn can put the leadership class at risk. The wave of defaults that swept through Europe in the 1930s, with Germany, Austria, Hungary and Italy all falling victims, allowed for the rise of the Nazis and set the stage for the Second World War. In Latin America, defaults and coups have gone hand in hand for much of the last two centuries.Sovereign RatingsThe most accessible measures of sovereign default risk are sovereign ratings, with S&P, Moody's and Fitch all providing both local currency and foreign currency ratings for most countries around the world. While there are many who mistrust these ratings, they are widely used as proxies of country risk and changes in ratings, especially down grades, are news worthy and affect markets. The process and metrics used to arrive at the ratings are described more fully here and here but the picture below summarizes the sovereign ratings assigned to countries in July 2017 and the data can be downloaded at this link:

Link for live mapThe last decade has turned the spotlight on both the pluses and minuses of ratings. On the plus side, as the ratings agencies are quick to point out, ratings and default spreads are highly correlated. On the minus side, ratings agencies seem to have regional biases (under rating emerging markets and over rating developed markets) and are slow to change ratings.

Link for live mapThe last decade has turned the spotlight on both the pluses and minuses of ratings. On the plus side, as the ratings agencies are quick to point out, ratings and default spreads are highly correlated. On the minus side, ratings agencies seem to have regional biases (under rating emerging markets and over rating developed markets) and are slow to change ratings. Sovereign CDS SpreadsIn the last decade, we have seen the growth of a market-based measure of default risk in the Credit Default Swap (CDS) market, where you can buy insurance against sovereign default by buying a sovereign CDS. Since the insurance is priced on annual basis, the price of a sovereign CDS becomes a market measure of the default spread for that country. In July 2017, there were 68 countries with sovereign CDS and the picture below captures the pricing (with the data available for download at this link). One of the limitations of the CDS market is that there is still credit risk in the market and to allow for the upward bias this creates in the spreads, I compute a netted version of the spread, where I net out the US sovereign CDS spread of 0.34% from each country's CDS spread.

Link for live mapTo provide a comparison between the CDS and sovereign rating measures of default risk, let me offer two example. The sovereign CDS for Brazil on July 1, 2017, was 3.46%. On the same day, Moody rated Brazil at Ba2, with an estimated default spread of 3.17%, close to the CDS value. For India, the sovereign CDS spread on July 1, 2017, was 2.42%, very close to the default spread of 2.32% that would have been assigned to it based upon its Baa3 rating.

Link for live mapTo provide a comparison between the CDS and sovereign rating measures of default risk, let me offer two example. The sovereign CDS for Brazil on July 1, 2017, was 3.46%. On the same day, Moody rated Brazil at Ba2, with an estimated default spread of 3.17%, close to the CDS value. For India, the sovereign CDS spread on July 1, 2017, was 2.42%, very close to the default spread of 2.32% that would have been assigned to it based upon its Baa3 rating.Country Risk - Institutional RiskWhen investing in a company, the sovereign default risk is just one of many risks that you have to factor into your decision making. In fact, default risk may pale in comparison to risks you face because of the institutional structure, or lack of it, in a country. At the risk of picking at scabs, here is my shot at assessing some of these risks.1. CorruptionMuch as we like to inveigh against its consequences, corruption is not just part and parcel of operating in some parts of the world, but it takes on the role of an implicit tax, one that is paid to free agents, acting in their own interests, rather than to governments. Transparency International, an entity that measures corruption risk around the world, estimates corruption scores for individual countries and heir findings for 2016 are summarized in the picture below. To see where a country falls on the corruption continuum, you can either click on the live link below the picture or download the data by country by clicking here.

Link to live mapWhile it is easy to fall back on cultural stereotypes to explain differences across countries, there is a high correlation between economic well being and corruption. Thus, while much of Latin America scores low on the corruption, Chile and Uruguay rank much higher, as do South Korea and Japan in Asia.

Link to live mapWhile it is easy to fall back on cultural stereotypes to explain differences across countries, there is a high correlation between economic well being and corruption. Thus, while much of Latin America scores low on the corruption, Chile and Uruguay rank much higher, as do South Korea and Japan in Asia.2. Legal ProtectionsEven the very best investments are only as good as the legal protections that you have as an investor, against expropriation or theft, which is why the property right protections rank high on investor wish lists. To measure the strength of property rights, I turned to the International Property Rights Index (IPRI), and report the scores they assigned in their most recent update in 2016, to countries in the picture below. You can click on the live link below the picture or download the data here.

Link to live mapEurope, North America, Japan and Australia all score high on property rights, but the hopeful sign is that index itself has seen increasing respect for property rights across time and Venezuela and Myanmar are now more the exception, than the rule.

Link to live mapEurope, North America, Japan and Australia all score high on property rights, but the hopeful sign is that index itself has seen increasing respect for property rights across time and Venezuela and Myanmar are now more the exception, than the rule.3. Risk of violenceIt is difficult to do business, when you have bullets whizzing by and bombs going off around you. Holding all else constant, you would prefer to operate in parts of the world that are safer rather than riskier. To measure exposure to violence, I again turn to an external entity, Vision of Humanity, and reproduce their Global Peace Index in the picture below (with link to live map and to data):

Link to live mapIn keeping with the adage that when it rains, it pours, the countries that are most susceptible to corruption and have weak property rights also seem to be most exposed to physical violence.

Link to live mapIn keeping with the adage that when it rains, it pours, the countries that are most susceptible to corruption and have weak property rights also seem to be most exposed to physical violence.Country Risk - Equity RiskAs you can see, there are multiple dimensions on which you can measure country risk, leading to different scores and rankings. As an investor in the country, you are exposed to all of these risks, albeit to varying degrees, and you have to consider all these risks in making decisions. Consequently, you would like (a) a composite measure of risk that (b) you can convert into a metric that easily fits into your investment framework.

1. Country Risk ScoresThere are several services that provide composite measures of country risk, including the Economist, Euromoney and Political Risk Services (PRS). These country risk measures take the form of numerical scores, and in the heat map below, I report the change in the PRS country risk score between July 2016 and July 2017 and categorize countries based on the direction and magnitude of the change. Here, as in the prior pictures, you can see the PRS scores and the change, by country, by either clicking on the live map link below the picture or download the data by clicking here).

Link for live mapBased on the PRS scores, the vast majority of emerging markets became safer during the time period between July 2016 and July 2017, with the biggest improvements in Latin America and Asia. The North American countries saw risk go up, as did pockets of Africa and South East Asia. The problem with country risk scores, no matter how well they are measured, is that they do not fit a standardized framework. Just to provide an illustration, PRS scores are low for risky countries and high for safe countries, whereas the Economist risk scores are high for risky countries and low for safe countries.

Link for live mapBased on the PRS scores, the vast majority of emerging markets became safer during the time period between July 2016 and July 2017, with the biggest improvements in Latin America and Asia. The North American countries saw risk go up, as did pockets of Africa and South East Asia. The problem with country risk scores, no matter how well they are measured, is that they do not fit a standardized framework. Just to provide an illustration, PRS scores are low for risky countries and high for safe countries, whereas the Economist risk scores are high for risky countries and low for safe countries.3. Equity Risk PremiumsTo incorporate and adjust for country risk into investing and valuation, I try to estimate the equity risk premiums for country, with riskier countries having higher equity risk premiums. I start with the implied equity risk premium for the US, which I estimate to be 5.13% at the start of July 2017 as my mature market premium and add to it a scaled up version of the default spread (based upon the rating); the scaling factor of 1.15 is based upon the relative volatility of emerging market equities versus bonds. You can see a more detailed description of the process in the paper that is linked at the end of this post. You can look up the equity risk premium for an individual country by clicking on the live map link or download the data by clicking here.

Link for live mapThese equity risk premiums are central to how I deal with country risk in valuation, as I will explain in the last section of this post.

Link for live mapThese equity risk premiums are central to how I deal with country risk in valuation, as I will explain in the last section of this post.Closing the LoopWhen valuing companies that have substantial exposure to country risk, it is easy to get overwhelmed by the variety of risks. To keep the process under your control, you should start by breaking country risk into three buckets: risk that is specific just to that country, risk that is macro/global and discrete risks that are potentially catastrophic (such as nationalization or terrorism). Each has a place in valuation, with country specific risks incorporated into expected cash flows, macro economic risks in the discount rate and discrete risks in a post-valuation adjustment.

1. Adjusting discount ratesThe key to a clean country risk adjustment, when estimating discount rates, is to make sure that you do not double or even triple count it. With the cost of equity for a company, for instance, where there are only three inputs that drive the cost, it is only the equity risk premium that should be conduit for country risk (hence explaining my earlier focus on equity risk premiums, by country). The risk free rate is a function of the currency that you choose to do your valuation in and the relative risk measure (or beta, if that is how you choose to measure it) should be determined by the business or businesses that the company operates in.

If you are discounting the composite cash flows of a multinational company, the equity risk premium should be a weighted average of the equity risk premiums of the countries that the company operates in, with the weights based on revenues or operating assets. If you are valuing just the operations in one country, you would use the equity risk premium just for that country.

2. Expected cash flowsWith risks that are specific to a country, it is better to incorporate the risks into the expected cash flows. Thus, if a country is rife with corruption, you could treat the resulting costs as part of operating expenses, reducing profits and cash flows. When legal and regulatory delays are a feature of business in a country, you can build in the delay as lags between investing and operations. When violence (from terrorism or war) is part and parcel of operations, you may want to include a cost of insuring against the risk in your cash flows.

None of these adjustments are easy to make, but it is worth remembering that incorporating the risk into your cash flows is not risk adjusting the cash flow, since the latter requires replacing the expected cash flow with a certainty equivalent one. Where does currency risk play out? When converting cash flows from one currency (foreign) to another (domestic), you should bring in expected devaluation or revaluation into expected exchange rates. If you want to hedge exchange rate risk, you can incorporate the cost of heeding into your cash flows but it is not clear that you should be adjusting discount rates for that risk, since investors can diversify it away.

3. Post-Valuation AdjustmentThere are some risks that are rare, but if they occur, can be devastating, at least for investors in a business. Included in this grouping would be the risk of nationalization and terrorism. These risks cannot be incorporated easily into discount rates and adjusting expected cash flows in a going concern valuation (DCF) for risk that a company will be nationalized or will not survive is messy.

Thus, to estimate the effect that nationalization risk will have on the value of a business, you will have to assess the probability that the business will be nationalized and the value that you will receive as owners of the business, in the event of nationalization.

Danger and OpportunityOne of my favorite definitions of risk is the Chinese symbol for it, a combination of the symbols for danger and opportunity. 風險With risky emerging markets, this comes into , I am reminded that to have one (opportunity), I have to be willing to live the other (danger). Blindly ignoring these markets, as some conservative developed market companies are inclined to do, because there is danger will lead to stagnation, but blindly jumping into them, drawn by opportunity, will cause implosions. The essence of risk management is to measure the danger in markets and then gauge whether the opportunities are sufficient to compensate you for the dangers. That is what I hope that I have laid the foundations for, in this post.

YouTube Video

Attachment