Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 21

January 9, 2018

January 2018 Data Update 2: The Buoyancy of US Equities

If you were an investor in US stocks, 2017 was a very good year for you. Faced with a wall of macro economic and political worries, the US equity market proved more than up to the challenge and delivered good returns, proving the experts wrong again. Looking back at the year, the word that I used to describe US equities at the start of last year, which was "resilient", best described US stocks in 2017 as well. As we enter 2018 with US stocks at historical highs, worries remain, but stocks are on a healthier footing now, than a year ago, in terms of fundamentals. At the same time, the long promised surge in T.Bond rates that the Fed watchers promised us would happen in 2017 was nowhere to be seen, which raises interesting questions about whether we should waste our time listening to either stock market prognosticators and Fed watchers. But then again, without them, how would CNBC fill all its time?

The Year that WasThe best way that I can think of mapping out the year is to look at how stocks and bonds performed on a month by month basis through the entire year. In the table below, I look at returns on the S&P 500 and on bonds, through the year: table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Start of monthS&P 500Price Appreciation in MonthT.Bond RateMonthly return1-Jan-1722392.45%1-Feb-1722791.79%2.47%0.03%1-Mar-1723643.73%2.40%0.82%1-Apr-172363-0.04%2.39%0.29%1-May-1723840.89%2.30%1.00%1-Jun-1724121.17%2.21%0.99%1-Jul-1724230.46%2.30%-0.61%1-Aug-1724701.94%2.30%0.19%1-Sep-172418-2.11%2.12%1.80%1-Oct-1725194.18%2.33%-1.68%1-Nov-1725752.22%2.37%-0.16%1-Dec-1726482.83%2.42%-0.24%1-Jan-1826740.98%2.41%0.29%Dividend Yield2.22%-Total Return21.65%2.80%The return on the S&P 500 for the year was 21.65%, with price appreciation accounting for 19.43% in returns and dividend yield representing the remaining 2.22%. In fact, the S&P 500 increased in ten of twelve months, with August representing the only significant down month; stocks were barely down in April. The T.Bond rate stayed within a tight bound for much of the year, with rates dropping to 2.12% at the start of September, from 2.45% at the start of the year, before rebounding to end the year little changed at 2.41%. Given that rates changed so little over the course of the year, the return on a 10-year T.Bond, with coupon and price change included, was 2.80%.

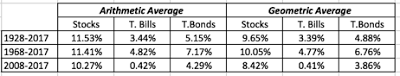

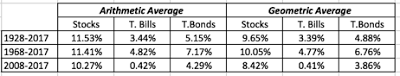

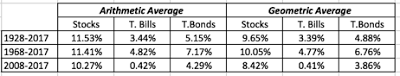

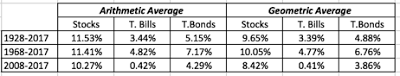

Putting 2017 in perspective, adding the 2017 returns for stocks, T.Bonds and T.Bills to the historical data yields the following historical annual average returns for the three asset classes: Download historical returns spreadsheetFor devotees of mean reversion (and I am not one), this table becomes the basis for estimating equity risk premiums, with the geometric average returns pointing to an equity risk premium of 4.77% over the 10-year T.Bond rate, i.e., the difference between the geometric average return on stocks (9.65%) and the geometric average return on bonds (4.88%).

Download historical returns spreadsheetFor devotees of mean reversion (and I am not one), this table becomes the basis for estimating equity risk premiums, with the geometric average returns pointing to an equity risk premium of 4.77% over the 10-year T.Bond rate, i.e., the difference between the geometric average return on stocks (9.65%) and the geometric average return on bonds (4.88%).

When stocks have as good a year as they did in 2017, you would normally expect the fundamentals to weaken, at least relative to prices, but stocks ended the year in a healthier state than at the start. That can be seen by comparing the earnings, dividends and cash returned in 2017, by the S&P 500 companies, relative to 2016:

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

20162017% Change for year10-Year AverageEarnings106.26124.9417.58%93.00Dividends45.749.738.82%32.76Dividends + Buybacks108.02109.891.73%82.28Payout Ratio43.01%39.80%42.05%Cash Return Ratio101.66%87.95%89.35%Note that earnings almost kept track with stock prices for the year, but the change is in the cash returned, where you saw a leveling off in the buyback boom. While that would normally be a negative for stocks, the draw back in buybacks left stocks looking healthier by reducing the cash returned as a percent of earnings from an unsustainable 101.66% in 2016 to 87.95% in 2017.

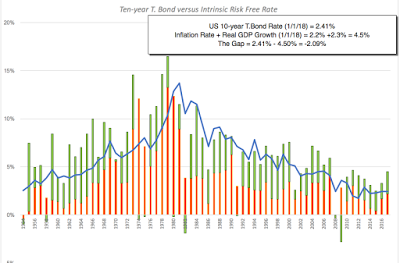

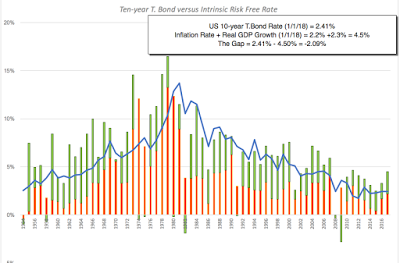

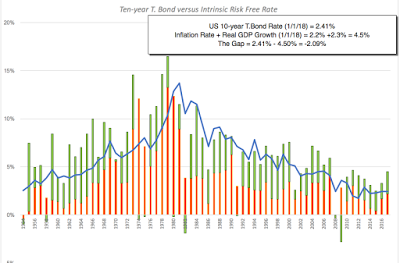

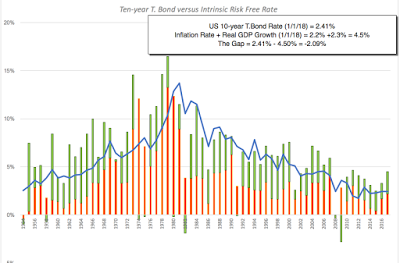

To evaluate whether the T.Bond rate is at a level that can be justified by fundamentals, I fall back on an approach that I have used before, where I compare the T.Bond rate to an intrinsic risk free rate that I compute by adding the inflation rate for the year to real growth rate in the economy (GDP real growth rate). While those numbers are still not final for 2017, using the most recent values for both allows for an update of my intrinsic interest rate chart: Download spreadsheet with data

The intrinsic risk free rate, using the estimated numbers as of January 1, 2018, is 4.50%, 2.09% higher than the US treasury bond rate of 2.41%, suggesting that there will be upward pressure on the US treasury bond rate over the next year.

Download spreadsheet with data

The intrinsic risk free rate, using the estimated numbers as of January 1, 2018, is 4.50%, 2.09% higher than the US treasury bond rate of 2.41%, suggesting that there will be upward pressure on the US treasury bond rate over the next year.

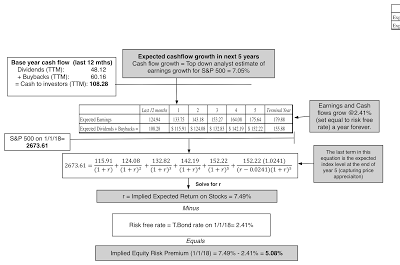

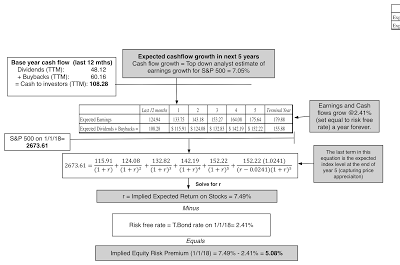

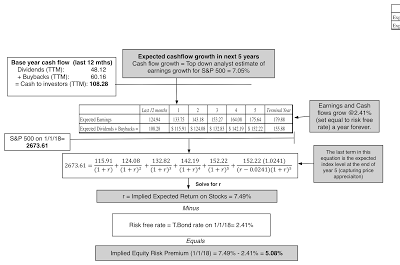

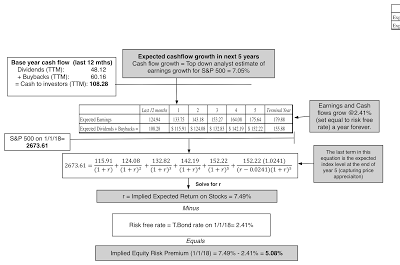

Looking ForwardWhile it is tempting to continue to dissect last year's numbers, it is healthier to turn our attention to the future. It is why I have increasingly moved away from using historical risk premiums, like the 4.77% premium that I computed by looking at the 1928-2017 return table, and towards implied equity risk premiums, where I back out what investors are demanding as a premium for investing in stocks by looking at how much they pay for stocks and what they expect to generate as cash flows. (Think of it as an IRR for stocks, analogous to the yield to maturity on a bond). At the start of 2018, putting this approach into play, I estimated an equity risk premium of 5.08% for the S&P 500:

Download spreadsheetIt is instructive to look at how the inputs have changed since the start of 2017, when my estimate of the implied ERP was 5.69%. The S&P 500 has risen 19.43%, while cash returned has remained stable; the drop in buybacks has been offset by an increase in dividends. Analysts have become more optimistic about future earnings growth, partly because US companies had a healthy earnings year and partly because of the expected drop in corporate tax rates. It is true that there are judgment calls that I had to make in estimating the implied premium, including using the analyst estimates of earnings growth for the S&P 500 (7.05%), but the resulting error pales in comparison to the standard error in the historical risk premium estimate.

Download spreadsheetIt is instructive to look at how the inputs have changed since the start of 2017, when my estimate of the implied ERP was 5.69%. The S&P 500 has risen 19.43%, while cash returned has remained stable; the drop in buybacks has been offset by an increase in dividends. Analysts have become more optimistic about future earnings growth, partly because US companies had a healthy earnings year and partly because of the expected drop in corporate tax rates. It is true that there are judgment calls that I had to make in estimating the implied premium, including using the analyst estimates of earnings growth for the S&P 500 (7.05%), but the resulting error pales in comparison to the standard error in the historical risk premium estimate.

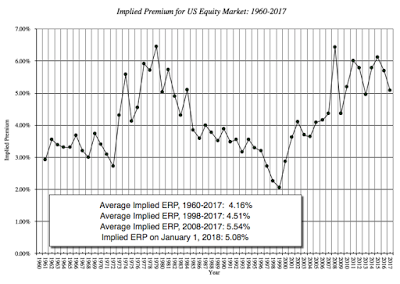

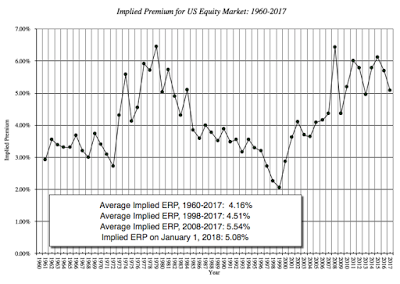

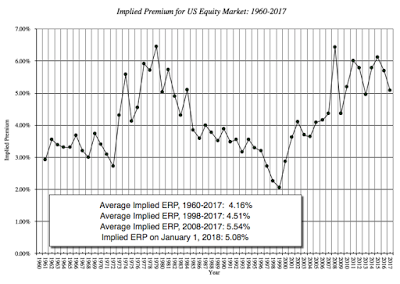

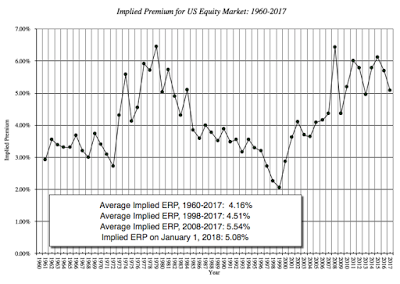

While I take this implied equity risk premium as a market price for risk, and will use it in my individual company valuations in January 2018, there are some who like playing the market timing game. If you are so inclined, the question that you are asking is whether 5.08% is a high, low or reasonable number. If you believe that the current implied premium is too low (high), you also have to believe that stocks are over priced (under priced), and to help you make that judgment, I have graphed the implied equity risk premium for the S&P 500 from 1960 to 2017 in the graph below: Historical Implied ERP spreadsheetThere is a reason why those who are intent on claiming that the market is in a bubble have a tough sell. Unlike the end of 1999, when implied equity risk premiums were at historical lows (close to 2%), the current implied ERP is well within the bounds of historic norms. It is only if you read this graph, in conjunction with the earlier one on risk free rates, that you should be concerned, since one reason that the premium is at 5.08% is because the US treasury bond rate is 2.41%. If the T.Bond rate moves towards 4.50%, and nothing else changes, the implied ERP will drop below comfort levels.

Historical Implied ERP spreadsheetThere is a reason why those who are intent on claiming that the market is in a bubble have a tough sell. Unlike the end of 1999, when implied equity risk premiums were at historical lows (close to 2%), the current implied ERP is well within the bounds of historic norms. It is only if you read this graph, in conjunction with the earlier one on risk free rates, that you should be concerned, since one reason that the premium is at 5.08% is because the US treasury bond rate is 2.41%. If the T.Bond rate moves towards 4.50%, and nothing else changes, the implied ERP will drop below comfort levels.

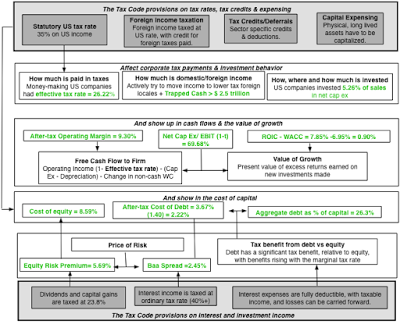

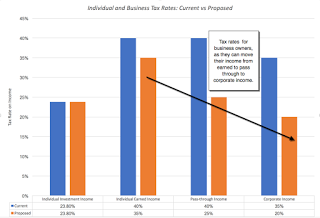

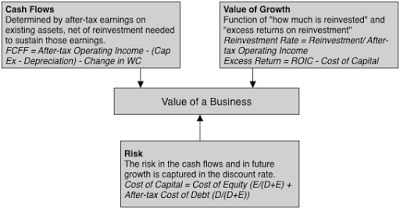

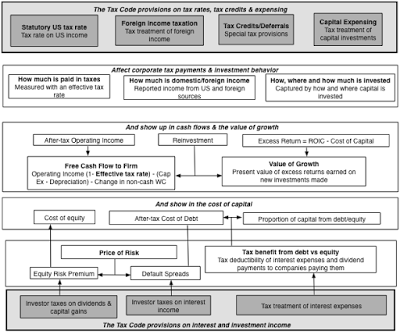

Worried about Equities? There has never been a time in the last three decades where I have felt sanguine about equity markets and I am thankful for that, since that is a sure sign of denial about the risk that is always under the surface, with stocks. That said, my worries shift from year to year and in this new year, I will continue to watch how the changing tax code will play out in both earnings and cash flows, since both are likely to be significantly affected, the former, because a lower tax rate should raise after-tax earnings, and the latter, because of the release of hundreds of billions of trapped cash. My macro crystal ball is always hazy but I expect T. Bond rates to rise, but if those higher rates go with a more robust economy, the market will take it in stride. There is the very real possibility that the economy stumbles, while rates rise, in which case US equities will be hard pressed to repeat their 2017 performance next year.

YouTube Video

Data Links

Historical Returns on Stocks, Bonds and Bills: 1928-2017T.Bond and Intrinsic Interest Rates: 1960-2017Implied Equity Risk Premium, S&P 500 (Jan 1, 2018)Historical Implied Equity Risk Premiums, 1960-2017Data Update PostsJanuary 2018 Data Update 1: Numbers don't lie, or do they?January 2018 Data Update 2: The Buoyancy of US Equities!January 2018 Data Update 3: Taxing Questions on ValueJanuary 2018 Data Update 4: The Currency ConundrumJanuary 2018 Data Update 5: Country Risk UpdateJanuary 2018 Data Update 6: A Cost of Capital PrimerJanuary 2018 Data Update 7: Growth and Value - Investment ReturnsJanuary 2018 Data Update 8: Debt and TaxesJanuary 2018 Data Update 9: The Cash Harvest - Dividend PolicyJanuary 2018 Data Update 10: The Pricing Prerogative

The Year that WasThe best way that I can think of mapping out the year is to look at how stocks and bonds performed on a month by month basis through the entire year. In the table below, I look at returns on the S&P 500 and on bonds, through the year: table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Start of monthS&P 500Price Appreciation in MonthT.Bond RateMonthly return1-Jan-1722392.45%1-Feb-1722791.79%2.47%0.03%1-Mar-1723643.73%2.40%0.82%1-Apr-172363-0.04%2.39%0.29%1-May-1723840.89%2.30%1.00%1-Jun-1724121.17%2.21%0.99%1-Jul-1724230.46%2.30%-0.61%1-Aug-1724701.94%2.30%0.19%1-Sep-172418-2.11%2.12%1.80%1-Oct-1725194.18%2.33%-1.68%1-Nov-1725752.22%2.37%-0.16%1-Dec-1726482.83%2.42%-0.24%1-Jan-1826740.98%2.41%0.29%Dividend Yield2.22%-Total Return21.65%2.80%The return on the S&P 500 for the year was 21.65%, with price appreciation accounting for 19.43% in returns and dividend yield representing the remaining 2.22%. In fact, the S&P 500 increased in ten of twelve months, with August representing the only significant down month; stocks were barely down in April. The T.Bond rate stayed within a tight bound for much of the year, with rates dropping to 2.12% at the start of September, from 2.45% at the start of the year, before rebounding to end the year little changed at 2.41%. Given that rates changed so little over the course of the year, the return on a 10-year T.Bond, with coupon and price change included, was 2.80%.

Putting 2017 in perspective, adding the 2017 returns for stocks, T.Bonds and T.Bills to the historical data yields the following historical annual average returns for the three asset classes:

Download historical returns spreadsheetFor devotees of mean reversion (and I am not one), this table becomes the basis for estimating equity risk premiums, with the geometric average returns pointing to an equity risk premium of 4.77% over the 10-year T.Bond rate, i.e., the difference between the geometric average return on stocks (9.65%) and the geometric average return on bonds (4.88%).

Download historical returns spreadsheetFor devotees of mean reversion (and I am not one), this table becomes the basis for estimating equity risk premiums, with the geometric average returns pointing to an equity risk premium of 4.77% over the 10-year T.Bond rate, i.e., the difference between the geometric average return on stocks (9.65%) and the geometric average return on bonds (4.88%).When stocks have as good a year as they did in 2017, you would normally expect the fundamentals to weaken, at least relative to prices, but stocks ended the year in a healthier state than at the start. That can be seen by comparing the earnings, dividends and cash returned in 2017, by the S&P 500 companies, relative to 2016:

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

20162017% Change for year10-Year AverageEarnings106.26124.9417.58%93.00Dividends45.749.738.82%32.76Dividends + Buybacks108.02109.891.73%82.28Payout Ratio43.01%39.80%42.05%Cash Return Ratio101.66%87.95%89.35%Note that earnings almost kept track with stock prices for the year, but the change is in the cash returned, where you saw a leveling off in the buyback boom. While that would normally be a negative for stocks, the draw back in buybacks left stocks looking healthier by reducing the cash returned as a percent of earnings from an unsustainable 101.66% in 2016 to 87.95% in 2017.

To evaluate whether the T.Bond rate is at a level that can be justified by fundamentals, I fall back on an approach that I have used before, where I compare the T.Bond rate to an intrinsic risk free rate that I compute by adding the inflation rate for the year to real growth rate in the economy (GDP real growth rate). While those numbers are still not final for 2017, using the most recent values for both allows for an update of my intrinsic interest rate chart:

Download spreadsheet with data

The intrinsic risk free rate, using the estimated numbers as of January 1, 2018, is 4.50%, 2.09% higher than the US treasury bond rate of 2.41%, suggesting that there will be upward pressure on the US treasury bond rate over the next year.

Download spreadsheet with data

The intrinsic risk free rate, using the estimated numbers as of January 1, 2018, is 4.50%, 2.09% higher than the US treasury bond rate of 2.41%, suggesting that there will be upward pressure on the US treasury bond rate over the next year.Looking ForwardWhile it is tempting to continue to dissect last year's numbers, it is healthier to turn our attention to the future. It is why I have increasingly moved away from using historical risk premiums, like the 4.77% premium that I computed by looking at the 1928-2017 return table, and towards implied equity risk premiums, where I back out what investors are demanding as a premium for investing in stocks by looking at how much they pay for stocks and what they expect to generate as cash flows. (Think of it as an IRR for stocks, analogous to the yield to maturity on a bond). At the start of 2018, putting this approach into play, I estimated an equity risk premium of 5.08% for the S&P 500:

Download spreadsheetIt is instructive to look at how the inputs have changed since the start of 2017, when my estimate of the implied ERP was 5.69%. The S&P 500 has risen 19.43%, while cash returned has remained stable; the drop in buybacks has been offset by an increase in dividends. Analysts have become more optimistic about future earnings growth, partly because US companies had a healthy earnings year and partly because of the expected drop in corporate tax rates. It is true that there are judgment calls that I had to make in estimating the implied premium, including using the analyst estimates of earnings growth for the S&P 500 (7.05%), but the resulting error pales in comparison to the standard error in the historical risk premium estimate.

Download spreadsheetIt is instructive to look at how the inputs have changed since the start of 2017, when my estimate of the implied ERP was 5.69%. The S&P 500 has risen 19.43%, while cash returned has remained stable; the drop in buybacks has been offset by an increase in dividends. Analysts have become more optimistic about future earnings growth, partly because US companies had a healthy earnings year and partly because of the expected drop in corporate tax rates. It is true that there are judgment calls that I had to make in estimating the implied premium, including using the analyst estimates of earnings growth for the S&P 500 (7.05%), but the resulting error pales in comparison to the standard error in the historical risk premium estimate. While I take this implied equity risk premium as a market price for risk, and will use it in my individual company valuations in January 2018, there are some who like playing the market timing game. If you are so inclined, the question that you are asking is whether 5.08% is a high, low or reasonable number. If you believe that the current implied premium is too low (high), you also have to believe that stocks are over priced (under priced), and to help you make that judgment, I have graphed the implied equity risk premium for the S&P 500 from 1960 to 2017 in the graph below:

Historical Implied ERP spreadsheetThere is a reason why those who are intent on claiming that the market is in a bubble have a tough sell. Unlike the end of 1999, when implied equity risk premiums were at historical lows (close to 2%), the current implied ERP is well within the bounds of historic norms. It is only if you read this graph, in conjunction with the earlier one on risk free rates, that you should be concerned, since one reason that the premium is at 5.08% is because the US treasury bond rate is 2.41%. If the T.Bond rate moves towards 4.50%, and nothing else changes, the implied ERP will drop below comfort levels.

Historical Implied ERP spreadsheetThere is a reason why those who are intent on claiming that the market is in a bubble have a tough sell. Unlike the end of 1999, when implied equity risk premiums were at historical lows (close to 2%), the current implied ERP is well within the bounds of historic norms. It is only if you read this graph, in conjunction with the earlier one on risk free rates, that you should be concerned, since one reason that the premium is at 5.08% is because the US treasury bond rate is 2.41%. If the T.Bond rate moves towards 4.50%, and nothing else changes, the implied ERP will drop below comfort levels. Worried about Equities? There has never been a time in the last three decades where I have felt sanguine about equity markets and I am thankful for that, since that is a sure sign of denial about the risk that is always under the surface, with stocks. That said, my worries shift from year to year and in this new year, I will continue to watch how the changing tax code will play out in both earnings and cash flows, since both are likely to be significantly affected, the former, because a lower tax rate should raise after-tax earnings, and the latter, because of the release of hundreds of billions of trapped cash. My macro crystal ball is always hazy but I expect T. Bond rates to rise, but if those higher rates go with a more robust economy, the market will take it in stride. There is the very real possibility that the economy stumbles, while rates rise, in which case US equities will be hard pressed to repeat their 2017 performance next year.

YouTube Video

Data Links

Historical Returns on Stocks, Bonds and Bills: 1928-2017T.Bond and Intrinsic Interest Rates: 1960-2017Implied Equity Risk Premium, S&P 500 (Jan 1, 2018)Historical Implied Equity Risk Premiums, 1960-2017Data Update PostsJanuary 2018 Data Update 1: Numbers don't lie, or do they?January 2018 Data Update 2: The Buoyancy of US Equities!January 2018 Data Update 3: Taxing Questions on ValueJanuary 2018 Data Update 4: The Currency ConundrumJanuary 2018 Data Update 5: Country Risk UpdateJanuary 2018 Data Update 6: A Cost of Capital PrimerJanuary 2018 Data Update 7: Growth and Value - Investment ReturnsJanuary 2018 Data Update 8: Debt and TaxesJanuary 2018 Data Update 9: The Cash Harvest - Dividend PolicyJanuary 2018 Data Update 10: The Pricing Prerogative

Published on January 09, 2018 10:39

January 2017 Data Update 2: The Buoyancy of US Equities

If you were an investor in US stocks, 2017 was a very good year for you. Faced with a wall of macro economic and political worries, the US equity market proved more than up to the challenge and delivered good returns, proving the experts wrong again. Looking back at the year, the word that I used to describe US equities at the start of last year, which was "resilient", best described US stocks in 2017 as well. As we enter 2018 with US stocks at historical highs, worries remain, but stocks are on a healthier footing now, than a year ago, in terms of fundamentals. At the same time, the long promised surge in T.Bond rates that the Fed watchers promised us would happen in 2017 was nowhere to be seen, which raises interesting questions about whether we should waste our time listening to either stock market prognosticators and Fed watchers. But then again, without them, how would CNBC fill all its time?

The Year that WasThe best way that I can think of mapping out the year is to look at how stocks and bonds performed on a month by month basis through the entire year. In the table below, I look at returns on the S&P 500 and on bonds, through the year: table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Start of monthS&P 500Price Appreciation in MonthT.Bond RateMonthly return1-Jan-1722392.45%1-Feb-1722791.79%2.47%0.03%1-Mar-1723643.73%2.40%0.82%1-Apr-172363-0.04%2.39%0.29%1-May-1723840.89%2.30%1.00%1-Jun-1724121.17%2.21%0.99%1-Jul-1724230.46%2.30%-0.61%1-Aug-1724701.94%2.30%0.19%1-Sep-172418-2.11%2.12%1.80%1-Oct-1725194.18%2.33%-1.68%1-Nov-1725752.22%2.37%-0.16%1-Dec-1726482.83%2.42%-0.24%1-Jan-1826740.98%2.41%0.29%Dividend Yield2.22%-Total Return21.65%2.80%The return on the S&P 500 for the year was 21.65%, with price appreciation accounting for 19.43% in returns and dividend yield representing the remaining 2.22%. In fact, the S&P 500 increased in ten of twelve months, with August representing the only significant down month; stocks were barely down in April. The T.Bond rate stayed within a tight bound for much of the year, with rates dropping to 2.12% at the start of September, from 2.45% at the start of the year, before rebounding to end the year little changed at 2.41%. Given that rates changed so little over the course of the year, the return on a 10-year T.Bond, with coupon and price change included, was 2.80%.

Putting 2017 in perspective, adding the 2017 returns for stocks, T.Bonds and T.Bills to the historical data yields the following historical annual average returns for the three asset classes: Download historical returns spreadsheetFor devotees of mean reversion (and I am not one), this table becomes the basis for estimating equity risk premiums, with the geometric average returns pointing to an equity risk premium of 4.77% over the 10-year T.Bond rate, i.e., the difference between the geometric average return on stocks (9.65%) and the geometric average return on bonds (4.88%).

Download historical returns spreadsheetFor devotees of mean reversion (and I am not one), this table becomes the basis for estimating equity risk premiums, with the geometric average returns pointing to an equity risk premium of 4.77% over the 10-year T.Bond rate, i.e., the difference between the geometric average return on stocks (9.65%) and the geometric average return on bonds (4.88%).

When stocks have as good a year as they did in 2017, you would normally expect the fundamentals to weaken, at least relative to prices, but stocks ended the year in a healthier state than at the start. That can be seen by comparing the earnings, dividends and cash returned in 2017, by the S&P 500 companies, relative to 2016:

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

20162017% Change for year10-Year AverageEarnings106.26124.9417.58%93.00Dividends45.749.738.82%32.76Dividends + Buybacks108.02109.891.73%82.28Payout Ratio43.01%39.80%42.05%Cash Return Ratio101.66%87.95%89.35%Note that earnings almost kept track with stock prices for the year, but the change is in the cash returned, where you saw a leveling off in the buyback boom. While that would normally be a negative for stocks, the draw back in buybacks left stocks looking healthier by reducing the cash returned as a percent of earnings from an unsustainable 101.66% in 2016 to 87.95% in 2017.

To evaluate whether the T.Bond rate is at a level that can be justified by fundamentals, I fall back on an approach that I have used before, where I compare the T.Bond rate to an intrinsic risk free rate that I compute by adding the inflation rate for the year to real growth rate in the economy (GDP real growth rate). While those numbers are still not final for 2017, using the most recent values for both allows for an update of my intrinsic interest rate chart: Download spreadsheet with data

The intrinsic risk free rate, using the estimated numbers as of January 1, 2018, is 4.50%, 2.09% higher than the US treasury bond rate of 2.41%, suggesting that there will be upward pressure on the US treasury bond rate over the next year.

Download spreadsheet with data

The intrinsic risk free rate, using the estimated numbers as of January 1, 2018, is 4.50%, 2.09% higher than the US treasury bond rate of 2.41%, suggesting that there will be upward pressure on the US treasury bond rate over the next year.

Looking ForwardWhile it is tempting to continue to dissect last year's numbers, it is healthier to turn our attention to the future. It is why I have increasingly moved away from using historical risk premiums, like the 4.77% premium that I computed by looking at the 1928-2017 return table, and towards implied equity risk premiums, where I back out what investors are demanding as a premium for investing in stocks by looking at how much they pay for stocks and what they expect to generate as cash flows. (Think of it as an IRR for stocks, analogous to the yield to maturity on a bond). At the start of 2018, putting this approach into play, I estimated an equity risk premium of 5.08% for the S&P 500:

Download spreadsheetIt is instructive to look at how the inputs have changed since the start of 2017, when my estimate of the implied ERP was 5.69%. The S&P 500 has risen 19.43%, while cash returned has remained stable; the drop in buybacks has been offset by an increase in dividends. Analysts have become more optimistic about future earnings growth, partly because US companies had a healthy earnings year and partly because of the expected drop in corporate tax rates. It is true that there are judgment calls that I had to make in estimating the implied premium, including using the analyst estimates of earnings growth for the S&P 500 (7.05%), but the resulting error pales in comparison to the standard error in the historical risk premium estimate.

Download spreadsheetIt is instructive to look at how the inputs have changed since the start of 2017, when my estimate of the implied ERP was 5.69%. The S&P 500 has risen 19.43%, while cash returned has remained stable; the drop in buybacks has been offset by an increase in dividends. Analysts have become more optimistic about future earnings growth, partly because US companies had a healthy earnings year and partly because of the expected drop in corporate tax rates. It is true that there are judgment calls that I had to make in estimating the implied premium, including using the analyst estimates of earnings growth for the S&P 500 (7.05%), but the resulting error pales in comparison to the standard error in the historical risk premium estimate.

While I take this implied equity risk premium as a market price for risk, and will use it in my individual company valuations in January 2018, there are some who like playing the market timing game. If you are so inclined, the question that you are asking is whether 5.08% is a high, low or reasonable number. If you believe that the current implied premium is too low (high), you also have to believe that stocks are over priced (under priced), and to help you make that judgment, I have graphed the implied equity risk premium for the S&P 500 from 1960 to 2017 in the graph below: Historical Implied ERP spreadsheetThere is a reason why those who are intent on claiming that the market is in a bubble have a tough sell. Unlike the end of 1999, when implied equity risk premiums were at historical lows (close to 2%), the current implied ERP is well within the bounds of historic norms. It is only if you read this graph, in conjunction with the earlier one on risk free rates, that you should be concerned, since one reason that the premium is at 5.08% is because the US treasury bond rate is 2.41%. If the T.Bond rate moves towards 4.50%, and nothing else changes, the implied ERP will drop below comfort levels.

Historical Implied ERP spreadsheetThere is a reason why those who are intent on claiming that the market is in a bubble have a tough sell. Unlike the end of 1999, when implied equity risk premiums were at historical lows (close to 2%), the current implied ERP is well within the bounds of historic norms. It is only if you read this graph, in conjunction with the earlier one on risk free rates, that you should be concerned, since one reason that the premium is at 5.08% is because the US treasury bond rate is 2.41%. If the T.Bond rate moves towards 4.50%, and nothing else changes, the implied ERP will drop below comfort levels.

Worried about Equities? There has never been a time in the last three decades where I have felt sanguine about equity markets and I am thankful for that, since that is a sure sign of denial about the risk that is always under the surface, with stocks. That said, my worries shift from year to year and in this new year, I will continue to watch how the changing tax code will play out in both earnings and cash flows, since both are likely to be significantly affected, the former, because a lower tax rate should raise after-tax earnings, and the latter, because of the release of hundreds of billions of trapped cash. My macro crystal ball is always hazy but I expect T. Bond rates to rise, but if those higher rates go with a more robust economy, the market will take it in stride. There is the very real possibility that the economy stumbles, while rates rise, in which case US equities will be hard pressed to repeat their 2017 performance next year.

YouTube Video

Data Links

Historical Returns on Stocks, Bonds and Bills: 1928-2017T.Bond and Intrinsic Interest Rates: 1960-2017Implied Equity Risk Premium, S&P 500 (Jan 1, 2018)Historical Implied Equity Risk Premiums, 1960-2017Data Update PostsJanuary 2018 Data Update 1: Numbers don't lie, or do they?January 2018 Data Update 2: The Buoyancy of US Equities!January 2018 Data Update 3: Taxing Questions on ValueJanuary 2018 Data Update 4: The Currency ConundrumJanuary 2018 Data Update 5: Country Risk January 2018 Data Update 6: Cost of Capital - A Global UpdateJanuary 2018 Data Update 7: Growth and Value - Investment ReturnsJanuary 2018 Data Update 8: Debt and ValueJanuary 2018 Data Update 9: The Cash Harvest - Dividend PolicyJanuary 2018 Data Update 10: The Pricing Prerogative

The Year that WasThe best way that I can think of mapping out the year is to look at how stocks and bonds performed on a month by month basis through the entire year. In the table below, I look at returns on the S&P 500 and on bonds, through the year: table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Start of monthS&P 500Price Appreciation in MonthT.Bond RateMonthly return1-Jan-1722392.45%1-Feb-1722791.79%2.47%0.03%1-Mar-1723643.73%2.40%0.82%1-Apr-172363-0.04%2.39%0.29%1-May-1723840.89%2.30%1.00%1-Jun-1724121.17%2.21%0.99%1-Jul-1724230.46%2.30%-0.61%1-Aug-1724701.94%2.30%0.19%1-Sep-172418-2.11%2.12%1.80%1-Oct-1725194.18%2.33%-1.68%1-Nov-1725752.22%2.37%-0.16%1-Dec-1726482.83%2.42%-0.24%1-Jan-1826740.98%2.41%0.29%Dividend Yield2.22%-Total Return21.65%2.80%The return on the S&P 500 for the year was 21.65%, with price appreciation accounting for 19.43% in returns and dividend yield representing the remaining 2.22%. In fact, the S&P 500 increased in ten of twelve months, with August representing the only significant down month; stocks were barely down in April. The T.Bond rate stayed within a tight bound for much of the year, with rates dropping to 2.12% at the start of September, from 2.45% at the start of the year, before rebounding to end the year little changed at 2.41%. Given that rates changed so little over the course of the year, the return on a 10-year T.Bond, with coupon and price change included, was 2.80%.

Putting 2017 in perspective, adding the 2017 returns for stocks, T.Bonds and T.Bills to the historical data yields the following historical annual average returns for the three asset classes:

Download historical returns spreadsheetFor devotees of mean reversion (and I am not one), this table becomes the basis for estimating equity risk premiums, with the geometric average returns pointing to an equity risk premium of 4.77% over the 10-year T.Bond rate, i.e., the difference between the geometric average return on stocks (9.65%) and the geometric average return on bonds (4.88%).

Download historical returns spreadsheetFor devotees of mean reversion (and I am not one), this table becomes the basis for estimating equity risk premiums, with the geometric average returns pointing to an equity risk premium of 4.77% over the 10-year T.Bond rate, i.e., the difference between the geometric average return on stocks (9.65%) and the geometric average return on bonds (4.88%).When stocks have as good a year as they did in 2017, you would normally expect the fundamentals to weaken, at least relative to prices, but stocks ended the year in a healthier state than at the start. That can be seen by comparing the earnings, dividends and cash returned in 2017, by the S&P 500 companies, relative to 2016:

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

20162017% Change for year10-Year AverageEarnings106.26124.9417.58%93.00Dividends45.749.738.82%32.76Dividends + Buybacks108.02109.891.73%82.28Payout Ratio43.01%39.80%42.05%Cash Return Ratio101.66%87.95%89.35%Note that earnings almost kept track with stock prices for the year, but the change is in the cash returned, where you saw a leveling off in the buyback boom. While that would normally be a negative for stocks, the draw back in buybacks left stocks looking healthier by reducing the cash returned as a percent of earnings from an unsustainable 101.66% in 2016 to 87.95% in 2017.

To evaluate whether the T.Bond rate is at a level that can be justified by fundamentals, I fall back on an approach that I have used before, where I compare the T.Bond rate to an intrinsic risk free rate that I compute by adding the inflation rate for the year to real growth rate in the economy (GDP real growth rate). While those numbers are still not final for 2017, using the most recent values for both allows for an update of my intrinsic interest rate chart:

Download spreadsheet with data

The intrinsic risk free rate, using the estimated numbers as of January 1, 2018, is 4.50%, 2.09% higher than the US treasury bond rate of 2.41%, suggesting that there will be upward pressure on the US treasury bond rate over the next year.

Download spreadsheet with data

The intrinsic risk free rate, using the estimated numbers as of January 1, 2018, is 4.50%, 2.09% higher than the US treasury bond rate of 2.41%, suggesting that there will be upward pressure on the US treasury bond rate over the next year.Looking ForwardWhile it is tempting to continue to dissect last year's numbers, it is healthier to turn our attention to the future. It is why I have increasingly moved away from using historical risk premiums, like the 4.77% premium that I computed by looking at the 1928-2017 return table, and towards implied equity risk premiums, where I back out what investors are demanding as a premium for investing in stocks by looking at how much they pay for stocks and what they expect to generate as cash flows. (Think of it as an IRR for stocks, analogous to the yield to maturity on a bond). At the start of 2018, putting this approach into play, I estimated an equity risk premium of 5.08% for the S&P 500:

Download spreadsheetIt is instructive to look at how the inputs have changed since the start of 2017, when my estimate of the implied ERP was 5.69%. The S&P 500 has risen 19.43%, while cash returned has remained stable; the drop in buybacks has been offset by an increase in dividends. Analysts have become more optimistic about future earnings growth, partly because US companies had a healthy earnings year and partly because of the expected drop in corporate tax rates. It is true that there are judgment calls that I had to make in estimating the implied premium, including using the analyst estimates of earnings growth for the S&P 500 (7.05%), but the resulting error pales in comparison to the standard error in the historical risk premium estimate.

Download spreadsheetIt is instructive to look at how the inputs have changed since the start of 2017, when my estimate of the implied ERP was 5.69%. The S&P 500 has risen 19.43%, while cash returned has remained stable; the drop in buybacks has been offset by an increase in dividends. Analysts have become more optimistic about future earnings growth, partly because US companies had a healthy earnings year and partly because of the expected drop in corporate tax rates. It is true that there are judgment calls that I had to make in estimating the implied premium, including using the analyst estimates of earnings growth for the S&P 500 (7.05%), but the resulting error pales in comparison to the standard error in the historical risk premium estimate. While I take this implied equity risk premium as a market price for risk, and will use it in my individual company valuations in January 2018, there are some who like playing the market timing game. If you are so inclined, the question that you are asking is whether 5.08% is a high, low or reasonable number. If you believe that the current implied premium is too low (high), you also have to believe that stocks are over priced (under priced), and to help you make that judgment, I have graphed the implied equity risk premium for the S&P 500 from 1960 to 2017 in the graph below:

Historical Implied ERP spreadsheetThere is a reason why those who are intent on claiming that the market is in a bubble have a tough sell. Unlike the end of 1999, when implied equity risk premiums were at historical lows (close to 2%), the current implied ERP is well within the bounds of historic norms. It is only if you read this graph, in conjunction with the earlier one on risk free rates, that you should be concerned, since one reason that the premium is at 5.08% is because the US treasury bond rate is 2.41%. If the T.Bond rate moves towards 4.50%, and nothing else changes, the implied ERP will drop below comfort levels.

Historical Implied ERP spreadsheetThere is a reason why those who are intent on claiming that the market is in a bubble have a tough sell. Unlike the end of 1999, when implied equity risk premiums were at historical lows (close to 2%), the current implied ERP is well within the bounds of historic norms. It is only if you read this graph, in conjunction with the earlier one on risk free rates, that you should be concerned, since one reason that the premium is at 5.08% is because the US treasury bond rate is 2.41%. If the T.Bond rate moves towards 4.50%, and nothing else changes, the implied ERP will drop below comfort levels. Worried about Equities? There has never been a time in the last three decades where I have felt sanguine about equity markets and I am thankful for that, since that is a sure sign of denial about the risk that is always under the surface, with stocks. That said, my worries shift from year to year and in this new year, I will continue to watch how the changing tax code will play out in both earnings and cash flows, since both are likely to be significantly affected, the former, because a lower tax rate should raise after-tax earnings, and the latter, because of the release of hundreds of billions of trapped cash. My macro crystal ball is always hazy but I expect T. Bond rates to rise, but if those higher rates go with a more robust economy, the market will take it in stride. There is the very real possibility that the economy stumbles, while rates rise, in which case US equities will be hard pressed to repeat their 2017 performance next year.

YouTube Video

Data Links

Historical Returns on Stocks, Bonds and Bills: 1928-2017T.Bond and Intrinsic Interest Rates: 1960-2017Implied Equity Risk Premium, S&P 500 (Jan 1, 2018)Historical Implied Equity Risk Premiums, 1960-2017Data Update PostsJanuary 2018 Data Update 1: Numbers don't lie, or do they?January 2018 Data Update 2: The Buoyancy of US Equities!January 2018 Data Update 3: Taxing Questions on ValueJanuary 2018 Data Update 4: The Currency ConundrumJanuary 2018 Data Update 5: Country Risk January 2018 Data Update 6: Cost of Capital - A Global UpdateJanuary 2018 Data Update 7: Growth and Value - Investment ReturnsJanuary 2018 Data Update 8: Debt and ValueJanuary 2018 Data Update 9: The Cash Harvest - Dividend PolicyJanuary 2018 Data Update 10: The Pricing Prerogative

Published on January 09, 2018 10:39

January 5, 2018

January 2018 Data Update 1: Numbers don't lie, or do they?

Every year, since 1992, I have spent the first week of my year, paying homage to the numbers gods. I collect raw accounting and market data from a variety of raw data providers, and I am grateful to all of them for making my life easier, and I summarize the data on many dimensions, by geography, by industry and by market capitalization. That summarized data, for the start of 2018, can be found on my website, as can the archived data from prior years.

The What?My dataset includes every publicly traded firm that has a market price available for it, in my raw dataset, and at the start of 2018, it included 43,848 firms, up from the 42,678 firms at the start of 2017. To the question of why I don't restrict myself to just the biggest, the most liquid or the most heavily followed firms, my answer is a statistical one. Any decision that I make on screening the data or sampling will create biases that will color my results, and while I will not claim to be bias-free (no one is), I would prefer to not initiate it with my sampling.

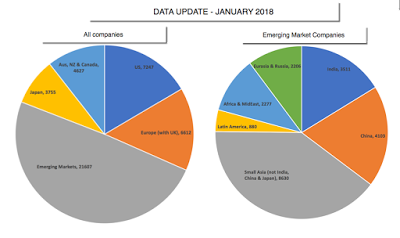

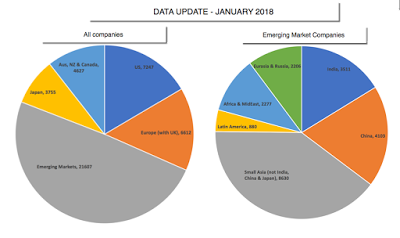

There are 135 countries that are represented in the data, though many have only a handful of firms that are incorporated there. That said, it is worth noting that while the companies are classified by country of incorporation, many have operations in multiple countries. I have classified my firms into five "big" groups: the United States, Europe (EU, UK), Emerging Markets, Japan and Australia/Canada/New Zealand. The pie chart below provides the breakdown: Download spreadsheetSince the emerging market grouping includes firms from Asia, Latin America, Africa and Eurasia, I also have the data for sub-groups including India, China, Small Asia (other than India, China and Japan), Latin America, Africa & MidEast and Russia/Eurasia. That is pictured in the second pie chart above.

Download spreadsheetSince the emerging market grouping includes firms from Asia, Latin America, Africa and Eurasia, I also have the data for sub-groups including India, China, Small Asia (other than India, China and Japan), Latin America, Africa & MidEast and Russia/Eurasia. That is pictured in the second pie chart above.

Within each geographic group, I break the companies down into 94 industry groupings and the numbers in each grouping are summarized at this link. While some would prefer a finer breakdown, I prefer this coarser grouping because it allows for larger sample sizes, especially as I go to sub-groups. Finally, I compute a range of numbers for each grouping, reflecting my corporate finance biases, and classify them into risk, profitability, leverage and cash return measures in the table below:

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Risk MeasuresCost of FundingPricing Multiples1. Beta1. Cost of Equity1. PE &PEG2. Standard deviation in stock price2. Cost of Debt2. Price to Book3. Standard deviation in operating income3. Cost of Capital3. EV/EBIT, EV/EBITDA and EV/EBITDA4. High-Low Price Risk Measure4. EV/Sales and Price/SalesProfitabilityFinancial LeverageCash Flow Add-ons1. Net Profit Margin1. D/E ratio & Debt/Capital (book & market) (with lease effect)1. Cap Ex & Net Cap Ex2. Operating Margin2. Debt/EBITDA2. Non-cash Working Capital as % of Revenue3. EBITDA, EBIT and EBITDAR&D Margins3. Interest Coverage Ratios3. Sales/Invested CapitalReturnsDividend PolicyRisk Premiums1. Return on Equity1. Dividend Payout & Yield1. Equity Risk Premiums (by country)2. Return on Capital2. Dividends/FCFE & (Dividends Buybacks)/ FCFE2. US equity returns (historical)3. ROE - Cost of Equity4. ROIC - Cost of CapitalThe links in the table will lead you to the html versions of the US data, but you can find the excel versions of this data and for the other groupings on my webpage. Since I report more than 150 data items, you may have to work to find what you are looking for but it (or a close variant) should be available somewhere on the site. Since there can be variations on how metrics are computed (like EV/EBITDA or even PE), I summarize my definitions at this link.

The Why?Much as I would like to claim that my data sharing is driven by altruism and making the world a better place, the reasons are more prosaic. I do this for myself. I enjoy analyzing the data for many reasons:Perspective: As our access to data increases, partly because of increased information disclosure on the part of firms, and partly because technology has made it easier to download data, it is ironic that we are more likely to develop tunnel vision now than before we had access to this data. When valuing individual companies, I find that knowing the industry and geographic averages gives me perspective on the numbers that I use for the company. Thus, when valuing Indofoods, an Indonesian food processing company, I can look at typical profit margins for food processing companies in South East Asia, in making my estimates for inputs, and compare my valuation to the pricing of other South East Asian food companies, when I am done.Rules of Thumb: Investing is full of rules of thumb that we devised in a different time for a different market, but still are used by investors, often without question. The notion that a stock that trades at a PEG ratio less than one or at a price less than its book value is cheap is deeply engrained in value investing books, but is it true? Looking at the cross sectional distributions of PEG and Price to Book ratios across all companies should give us the answer and allow us to eliminate the rules of thumb that no longer work.Curiosity: There are questions that all of us have about companies that the numbers can help answer. Do US companies pay less in taxes than their foreign counterparts? Does growth create or destroy value at companies? The answers to these questions are in the numbers and I find that they provide an antidote to experts who try to pass off opinions as facts.Trends and Shifts: Companies change over time, albeit slowly, and these changes have consequences not just for investors, but for governments, taxpayers and workers. One reason that I do not make jarring changes in the way that I classify and report my numbers is to see how these numbers change over time.In the next two weeks, I will try to summarize what I learn from the data about corporate investment, financing and dividend policy in a series of posts that I have tentatively listed at the end of this post, starting with an update on US equities (and risk premiums) and ending with the a look at market pricing multiples at the end of 2017. Along the way, I will grapple with the rise of crypto currencies and what they might or might not mean for valuation. The motivations for creating these datasets are selfish but I find it pointless to keep them to myself. After all, there is no secret sauce in this data that will lead me to riches, and nothing that someone else with access to the raw data could not generate themselves. If, in the process, a few people are able to use my data in their analyses, I consider them deposits in my "good karma" bank.

The QuirksEach year that I update the data, there are four challenges that await me. The first relates to data timing, where I try to put myself in the shoes of an investor making investment choices on January 2, 2018. The second is how best to deal with missing data, par for the course since my dataset includes some very small companies in under developed markets. The third is to clean up after the accountants, who are not always consistent in their rules across sectors and geographies. The fourth and final challenge is to find and correct mistakes in the data.Timing: All of the data that I have used in my analysis was collected after the close of trading on the last trading day of 2017 (December 29 for most markets) and reflects the most updated data, as of that day. That said, it is worth noting that not all data gets updated at the same rate, with market-set numbers (risk free rate, stock prices, risk premiums) being as of close of trading at the end of the year, but accounting numbers reflecting the most recent financial reports (from October, November and December of 2017). The accounting numbers that I use to compute my financial and pricing ratios are therefore trailing 12-month numbers, if they are updated every quarter, or even 2016 numbers, if they are not updated. Missing Data: Information disclosure requirements vary widely across markets and since my dataset spans all markets, there are some items that are available in some markets and not in others. Rather than eliminate companies with missing data, which will both decimate and bias my sample, I keep them in the sample and deal with them the best that I can. For instance, US companies report stock based compensation as an expense item but many non-US companies do not. I report stock based compensation as a percent of total revenues in every market but they are close to reality only in the US data.Accounting inconsistencies: I have argued in prior posts that accountants are inconsistent in their treatment of capital expenditures and debt across companies, treating the biggest capital expenditures (R&D) at technology and pharmaceutical companies as operating expenses and ignoring the primary debt (leases) at retail and restaurant companies. Rather than wait for accounting rules to come to their senses, which may take decades, I have capitalized both R&D and lease commitments for all companies and that has consequences for my earnings, invested capital and debt numbers.Data mistakes: Working with a spreadsheet with 43,848 companies and 150 data items, I am sure that there are mistakes that have found their way into my summaries, notwithstanding my attempts to catch them. Some of these mistakes are mine but some reflect errors in the raw data. The datasets that are least likely to be affected by mistakes are the US and Global dataset, where I have a combination of the law of large numbers and good disclosure backing me up. Needless to say, if you do find mistakes, please draw my attention to them.The CaveatsIf you find my data useful in your investing, valuation or corporate finance analysis, you are welcome to partake of it. That said, as a number cruncher who both loves numbers and views them with caution, here are a few things to keep in mind.Numbers ≠ Facts: While the numbers, once reported, look precise, they are not facts. Thus, when you look at the debt ratios that I report for a sector, it is worth emphasizing that I have capitalized lease commitments and added them to all interest bearing debt (short and long term) to arrive at total debt, yielding a different number than what you may see on a different service. I have tried to be as transparent as I can in making my estimates but they reflect my judgment calls. Past is not always prologue: There are some numbers where I report historical trend lines and averages. That is not because I am a die-hard believer in mean reversion, the driving force in many investment philosophies. I believe that knowing history is useful in investing, but trusting it to repeat itself is dangerous.Just because everyone does it does not make it right: As you look at the datasets, you will see patterns in investment, financing and dividend policy in sectors. Some sectors, such as telecommunications, are more debt funded than others, say pharmaceuticals, and other pay more dividends (utilities) than others (technology). While there are often good reasons for these differences, there are also bad ones, with inertial on top of that list. The reality is that there are established corporate finance policies in many sectors that no longer make sense, because the sectors have changed fundamentally over time.As you browse through the numbers, you will notice that I report almost no numbers at the company level. While I do have that data, I am constrained from sharing that data, because I risk stepping on the toes and the legal rights of my raw data providers.

ConclusionAt the end of my data week, I am both exhilarated and exhausted, exhilarated because I can now analyze the data and exhausted because even a number cruncher can get tired of working with numbers. There is information in this data but it will take more care than I have given it so far, but I have the rest of the year to spend looking for those nuggets.

YouTube Video

LinksData BreakdownMy current data pageMy archived data pageData Update PostsJanuary 2018 Data Update 1: Numbers don't lie, or do they?January 2018 Data Update 2: US Equities, Let the Good Times Roll!January 2018 Data Update 3: A New Tax Code - Value Consequences? January 2018 Data Update 4: The Currency QuestionJanuary 2018 Data Update 5: Country Risk January 2018 Data Update 6: Cost of Capital - A Global UpdateJanuary 2018 Data Update 7: Growth and Value - Investment ReturnsJanuary 2018 Data Update 8: Debt and ValueJanuary 2018 Data Update 9: The Cash Harvest - Dividend PolicyJanuary 2018 Data Update 10: The Pricing Prerogative

The What?My dataset includes every publicly traded firm that has a market price available for it, in my raw dataset, and at the start of 2018, it included 43,848 firms, up from the 42,678 firms at the start of 2017. To the question of why I don't restrict myself to just the biggest, the most liquid or the most heavily followed firms, my answer is a statistical one. Any decision that I make on screening the data or sampling will create biases that will color my results, and while I will not claim to be bias-free (no one is), I would prefer to not initiate it with my sampling.

There are 135 countries that are represented in the data, though many have only a handful of firms that are incorporated there. That said, it is worth noting that while the companies are classified by country of incorporation, many have operations in multiple countries. I have classified my firms into five "big" groups: the United States, Europe (EU, UK), Emerging Markets, Japan and Australia/Canada/New Zealand. The pie chart below provides the breakdown:

Download spreadsheetSince the emerging market grouping includes firms from Asia, Latin America, Africa and Eurasia, I also have the data for sub-groups including India, China, Small Asia (other than India, China and Japan), Latin America, Africa & MidEast and Russia/Eurasia. That is pictured in the second pie chart above.

Download spreadsheetSince the emerging market grouping includes firms from Asia, Latin America, Africa and Eurasia, I also have the data for sub-groups including India, China, Small Asia (other than India, China and Japan), Latin America, Africa & MidEast and Russia/Eurasia. That is pictured in the second pie chart above.Within each geographic group, I break the companies down into 94 industry groupings and the numbers in each grouping are summarized at this link. While some would prefer a finer breakdown, I prefer this coarser grouping because it allows for larger sample sizes, especially as I go to sub-groups. Finally, I compute a range of numbers for each grouping, reflecting my corporate finance biases, and classify them into risk, profitability, leverage and cash return measures in the table below:

table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

Risk MeasuresCost of FundingPricing Multiples1. Beta1. Cost of Equity1. PE &PEG2. Standard deviation in stock price2. Cost of Debt2. Price to Book3. Standard deviation in operating income3. Cost of Capital3. EV/EBIT, EV/EBITDA and EV/EBITDA4. High-Low Price Risk Measure4. EV/Sales and Price/SalesProfitabilityFinancial LeverageCash Flow Add-ons1. Net Profit Margin1. D/E ratio & Debt/Capital (book & market) (with lease effect)1. Cap Ex & Net Cap Ex2. Operating Margin2. Debt/EBITDA2. Non-cash Working Capital as % of Revenue3. EBITDA, EBIT and EBITDAR&D Margins3. Interest Coverage Ratios3. Sales/Invested CapitalReturnsDividend PolicyRisk Premiums1. Return on Equity1. Dividend Payout & Yield1. Equity Risk Premiums (by country)2. Return on Capital2. Dividends/FCFE & (Dividends Buybacks)/ FCFE2. US equity returns (historical)3. ROE - Cost of Equity4. ROIC - Cost of CapitalThe links in the table will lead you to the html versions of the US data, but you can find the excel versions of this data and for the other groupings on my webpage. Since I report more than 150 data items, you may have to work to find what you are looking for but it (or a close variant) should be available somewhere on the site. Since there can be variations on how metrics are computed (like EV/EBITDA or even PE), I summarize my definitions at this link.

The Why?Much as I would like to claim that my data sharing is driven by altruism and making the world a better place, the reasons are more prosaic. I do this for myself. I enjoy analyzing the data for many reasons:Perspective: As our access to data increases, partly because of increased information disclosure on the part of firms, and partly because technology has made it easier to download data, it is ironic that we are more likely to develop tunnel vision now than before we had access to this data. When valuing individual companies, I find that knowing the industry and geographic averages gives me perspective on the numbers that I use for the company. Thus, when valuing Indofoods, an Indonesian food processing company, I can look at typical profit margins for food processing companies in South East Asia, in making my estimates for inputs, and compare my valuation to the pricing of other South East Asian food companies, when I am done.Rules of Thumb: Investing is full of rules of thumb that we devised in a different time for a different market, but still are used by investors, often without question. The notion that a stock that trades at a PEG ratio less than one or at a price less than its book value is cheap is deeply engrained in value investing books, but is it true? Looking at the cross sectional distributions of PEG and Price to Book ratios across all companies should give us the answer and allow us to eliminate the rules of thumb that no longer work.Curiosity: There are questions that all of us have about companies that the numbers can help answer. Do US companies pay less in taxes than their foreign counterparts? Does growth create or destroy value at companies? The answers to these questions are in the numbers and I find that they provide an antidote to experts who try to pass off opinions as facts.Trends and Shifts: Companies change over time, albeit slowly, and these changes have consequences not just for investors, but for governments, taxpayers and workers. One reason that I do not make jarring changes in the way that I classify and report my numbers is to see how these numbers change over time.In the next two weeks, I will try to summarize what I learn from the data about corporate investment, financing and dividend policy in a series of posts that I have tentatively listed at the end of this post, starting with an update on US equities (and risk premiums) and ending with the a look at market pricing multiples at the end of 2017. Along the way, I will grapple with the rise of crypto currencies and what they might or might not mean for valuation. The motivations for creating these datasets are selfish but I find it pointless to keep them to myself. After all, there is no secret sauce in this data that will lead me to riches, and nothing that someone else with access to the raw data could not generate themselves. If, in the process, a few people are able to use my data in their analyses, I consider them deposits in my "good karma" bank.

The QuirksEach year that I update the data, there are four challenges that await me. The first relates to data timing, where I try to put myself in the shoes of an investor making investment choices on January 2, 2018. The second is how best to deal with missing data, par for the course since my dataset includes some very small companies in under developed markets. The third is to clean up after the accountants, who are not always consistent in their rules across sectors and geographies. The fourth and final challenge is to find and correct mistakes in the data.Timing: All of the data that I have used in my analysis was collected after the close of trading on the last trading day of 2017 (December 29 for most markets) and reflects the most updated data, as of that day. That said, it is worth noting that not all data gets updated at the same rate, with market-set numbers (risk free rate, stock prices, risk premiums) being as of close of trading at the end of the year, but accounting numbers reflecting the most recent financial reports (from October, November and December of 2017). The accounting numbers that I use to compute my financial and pricing ratios are therefore trailing 12-month numbers, if they are updated every quarter, or even 2016 numbers, if they are not updated. Missing Data: Information disclosure requirements vary widely across markets and since my dataset spans all markets, there are some items that are available in some markets and not in others. Rather than eliminate companies with missing data, which will both decimate and bias my sample, I keep them in the sample and deal with them the best that I can. For instance, US companies report stock based compensation as an expense item but many non-US companies do not. I report stock based compensation as a percent of total revenues in every market but they are close to reality only in the US data.Accounting inconsistencies: I have argued in prior posts that accountants are inconsistent in their treatment of capital expenditures and debt across companies, treating the biggest capital expenditures (R&D) at technology and pharmaceutical companies as operating expenses and ignoring the primary debt (leases) at retail and restaurant companies. Rather than wait for accounting rules to come to their senses, which may take decades, I have capitalized both R&D and lease commitments for all companies and that has consequences for my earnings, invested capital and debt numbers.Data mistakes: Working with a spreadsheet with 43,848 companies and 150 data items, I am sure that there are mistakes that have found their way into my summaries, notwithstanding my attempts to catch them. Some of these mistakes are mine but some reflect errors in the raw data. The datasets that are least likely to be affected by mistakes are the US and Global dataset, where I have a combination of the law of large numbers and good disclosure backing me up. Needless to say, if you do find mistakes, please draw my attention to them.The CaveatsIf you find my data useful in your investing, valuation or corporate finance analysis, you are welcome to partake of it. That said, as a number cruncher who both loves numbers and views them with caution, here are a few things to keep in mind.Numbers ≠ Facts: While the numbers, once reported, look precise, they are not facts. Thus, when you look at the debt ratios that I report for a sector, it is worth emphasizing that I have capitalized lease commitments and added them to all interest bearing debt (short and long term) to arrive at total debt, yielding a different number than what you may see on a different service. I have tried to be as transparent as I can in making my estimates but they reflect my judgment calls. Past is not always prologue: There are some numbers where I report historical trend lines and averages. That is not because I am a die-hard believer in mean reversion, the driving force in many investment philosophies. I believe that knowing history is useful in investing, but trusting it to repeat itself is dangerous.Just because everyone does it does not make it right: As you look at the datasets, you will see patterns in investment, financing and dividend policy in sectors. Some sectors, such as telecommunications, are more debt funded than others, say pharmaceuticals, and other pay more dividends (utilities) than others (technology). While there are often good reasons for these differences, there are also bad ones, with inertial on top of that list. The reality is that there are established corporate finance policies in many sectors that no longer make sense, because the sectors have changed fundamentally over time.As you browse through the numbers, you will notice that I report almost no numbers at the company level. While I do have that data, I am constrained from sharing that data, because I risk stepping on the toes and the legal rights of my raw data providers.

ConclusionAt the end of my data week, I am both exhilarated and exhausted, exhilarated because I can now analyze the data and exhausted because even a number cruncher can get tired of working with numbers. There is information in this data but it will take more care than I have given it so far, but I have the rest of the year to spend looking for those nuggets.

YouTube Video

LinksData BreakdownMy current data pageMy archived data pageData Update PostsJanuary 2018 Data Update 1: Numbers don't lie, or do they?January 2018 Data Update 2: US Equities, Let the Good Times Roll!January 2018 Data Update 3: A New Tax Code - Value Consequences? January 2018 Data Update 4: The Currency QuestionJanuary 2018 Data Update 5: Country Risk January 2018 Data Update 6: Cost of Capital - A Global UpdateJanuary 2018 Data Update 7: Growth and Value - Investment ReturnsJanuary 2018 Data Update 8: Debt and ValueJanuary 2018 Data Update 9: The Cash Harvest - Dividend PolicyJanuary 2018 Data Update 10: The Pricing Prerogative

Published on January 05, 2018 14:14

October 27, 2017

Bitcoin Backlash: Back to the Drawing Board?

My last post on Bitcoin got me some push back and I am glad that it did. I would rather be read, and disagreed with, than not read at all. I have been told that I know very little about crypto currencies and that I have much to learn, and I agree. The crux of the disagreements though lay in my classifying Bitcoin as a currency, not as an asset or as a commodity. Since this classification is central to how you should think about investing versus trading, and value versus price, and goes well beyond Bitcoin, I decided to dig deeper into the classification and provide even more ammunition for those who disagree with me to tell me how wrong I am.

Classifying Investment: The What and the Why

We are products of our own world views, and mine, for better or worse, are built around my interest in valuation. It is that perspective that led me to classifying investments into cash flow generating assets, commodities, currencies and collectibles. To value an investment, I need that investment to generate future cashflows (at least on an expected basis) and that was my basis for separating cash flow generating assets (which range the spectrum from a bond to a stock to a business) from the rest.

The pushback that I got did not surprised me, partly because my definition may be at odds with the definitions used by other entities. Accountants, for instance, classify items as assets that I think are pure fiction, such as goodwill. There are others who argue that any investment on which you can make money is an asset, broadening it to include just about everything from baseball cards to government bonds. In fact, crypto currencies have been at the center of many of these disagreements, with the SEC recently deciding to treat ICOs as securities (and thus assets) and the Korean central bank categorizing Bitcoin as a commodity. Since the judgment made by these entities have regulatory and tax consequences, I am sure that they will be debated, discussed and disagreed with.

Why Bitcoin is a currency and not an asset..One reason that people are uncomfortable drawing the line between currency, commodity and asset is that the line can sometimes shift quickly. Take the US dollar, for instance. Its primary purpose is to serve as a medium of exchange and as a store of value, and it is thus a currency. However, you can lend US dollars to a business or individual and generate interest income. That is true, but it is not the currency that is then the asset, but the loan that you make with it, or the bond that is denominated in it. Building further, if I create a bank that takes in deposits in dollars (and pays an interest rate on them) and lends out those dollars as loans, I have a business and that business is an asset. I can value the loan and the bond based upon the interest rate you earn and the default risk that you face, or the bank, based upon the interest rate spread it earns and the risk of default that it faces on its collective portfolio, but I cannot value the US dollar.

Can I construct investments denominated in Bitcoin or another crypto currency that earn me interest or a return? Of course, but I can do that in any currency, and it is in fact one of the functions of a currency. That does not make Bitcoin an asset! You can already see that the question of whether Initial Coin Offerings (ICO) are currencies or assets becomes trickier, because an ICO can be constructed to give you a share of the ownership in a business (and the cash flows from that business), making it more of an asset than a currency (thus giving credence to the SEC's view that it is a security). The lack of standardization in ICO structures, though, makes it difficult to generalize, since loosely put, an ICO can be constructed to be anything from a donation (at least, according to Kathleen Breitman at Tezos) to quasi common stock (without the voting rights).

A few of you have pointed to the networking benefits that might create value for Bitcoin, but I am afraid that I don't see that as a basis for assigning value to it. A network can become an asset, but only when you can make money off the network. The value of Facebook to me, as an investor, is not that I am part of the Facebook network (I am not, since I have not posted on Facebook in almost three years) but that I get a share of the money made from selling advertising to those on the network. Unless you can trace monetary benefits to being part of the Bitcoin network, there is no value to being part of the network. (Visa and MasterCard are assets, not because they have wide networks and are accepted globally, but because every time they are used, they make 1-2% of the transaction value.) To the argument that Bitcoin miners can make money as the network expands, that value is for providing a service, not for holding Bitcoin.

Why Bitcoin is more currency than commodity

The essence of a currency is that its primary uses are as a medium of exchange or as a store of value. The key to a commodity is that it is an input into a process that has a utilitarian function. Oil and coal are clearly commodities, since they derive their value from the fact that they can be used to produce energy. It is true, as with currencies, that you can create an asset based upon a commodity. A share of an oil well is an asset not because you like or even need oil, it is because you hope to sell the oil to generate cash flows. It is also true that gold is a commodity, but as I noted in the prior post, I think it is more currency than commodity, because the quantity of gold that we have on the face of the earth vastly exceeds whatever utilitarian needs it might serve. It is shiny, durable, makes beautiful jewelry and has some industrial uses, but if that is all we valued gold for, it would be worth a lot less than it is trading for, and there would be less of it around.

The question with Bitcoin then becomes whether it can become (or perhaps already is) like gold. Here is my test: If tomorrow, humanity collectively decided to abandon its attachment to gold as a value store, would its price go to zero? I don't think so, because it does have uses and while its price will drop, it will be priced like based on those uses. Applying the same test to Bitcoin, I am left nonplussed about what value to attach to a digital currency if at the end, no one uses it in transactions, it has no aesthetic value and it produces nothing utilitarian.