Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 18

October 29, 2018

An October Surprise? Making Sense of the Market Mayhem!

I don't know what it is about October that spooks markets, but it certainly feels like big market corrections happen in the month. As stocks have gone through contortions this month, more down than up, like many of you, I have been looking at my portfolio, wondering whether this is the crash that the market bears have been warning me about since 2012, just a pause in a continuing bull market or perhaps a prognosticator of economic troubles to come. If you are expecting me to give you the answer in this post, I would stop reading, since reading market tea leaves is not my strength. That said, I have been wrestling with what, if anything, I should be doing, as an investor, in response to the market movements. As in previous market crises, I find myself going back to a four-step process that I hope gets me through with my sanity intact.

Step 1: Hit the pause buttonThe first casualty of crisis is good sense, as I mistake my panic response for instinct, and almost every action that I feel the urge to take in the heat of the moment is driven by fear and greed, not reason. No amount of rational thinking or studying behavioral finance will cure me of this affliction, since it is part of my make up as a human being, but there are three things that I find help me manage my reactions:Take a breath: When faced with fast-moving markets, I have to force myself to consciously slow down. It helps that I don't work as a trader or a portfolio manager, since part of your job is to look like you are in control, even when you are not. Turn off the noise: Turn back the clock about four decades and assume that you were a doctor, a lawyer or a factory worker with much of your wealth invested in stocks. If markets were having a bad day, odds were that you would not even have heard about it until you got home and turned on the news, and even then, you would have been fed scraps of information about Dow, perhaps a 2-minute discussion with a market expert, and you would have then turned on your favorite sitcom. Today, not only can you monitor your stocks every moment of your working day, you can trade on your lunch break and stream CNBC on to your desktop. That may make you a more informed investor, or at least an investor with more information, but I am not sure that constant feedback is healthy for your portfolio, especially in periods like this one. I don't have a Bloomberg terminal on my desk, a ticker tape running on my computer or stock apps on my phone, and I am happy that I don't during periods like this month.Don't play the blame game: Every market correction has its villains, and investors like to tag them. Central banks and governments are always good targets, since they have few defenders and have a history of triggering market meltdowns. The problem that I find with assigning blame to others is that it then relieves me of any responsibility, even for own mistakes, and thus makes it impossible to learn from them and take corrective action. Step 2: Assess the damage In an age of instant analysis and expert opinion, it is easy to get a skewed view of not only what is causing the market damage, but also where that damage is greatest. In my (limited) reading of market analyses during the last four weeks, I have seen at least a half a dozen hypotheses about the stock swoon, from it being the Fed's fault (as usual) to a long overdue tech company correction to it being a response to global crises (in Italy and Saudi Arabia). In keeping with the old adage of "trust, but verify", I decided to take a look at the data to see if there are answers in it to these questions.

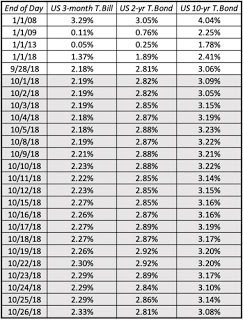

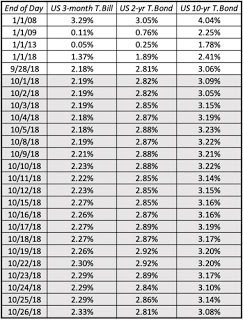

1.The Fed's fault? As those of you who read my blog know well, I believe that the Fed has far less power than we think it does to set interest rates, but it is a convenient bogeyman. One explanation for the stock drop that has been making the rounds is that it is fear that Fed will raise rates too quickly in the future, that is causing stocks to swoon. Is that a plausible story? Yes, but if it is the reason for the market decline, you would have a difficult time explaining the movement in interest rates during October 2018: Source: Federal Reserve (FRED)As stocks have gone through their pains since October 1, treasury bill and bond rates have remained steady, which would make little sense if the expectation is that they will rise in the near future. After all, if investors expect rates to rise soon, those rates will start going up now and not on cue, when the Fed acts.

Source: Federal Reserve (FRED)As stocks have gone through their pains since October 1, treasury bill and bond rates have remained steady, which would make little sense if the expectation is that they will rise in the near future. After all, if investors expect rates to rise soon, those rates will start going up now and not on cue, when the Fed acts.

There is the possibility that this could be a delayed reaction to rates having gone up over the year already, with the 10-year treasury bond rate moving from 2.41% at the start of the year to 3.06% at the start of October 2018 and to a flattening yield curve (which has historically been a precursor to slower economic growth). Note though, that much of this movement in interest rates happened in the first six months of the year and you would need a reason for why stock prices would be moving four months later.

2. A Tech Meltdown? My view, based upon what I had been hearing and reading, and before I looked at the data, was that the October 2018 stock drop was being caused by tech companies, in general, and the large tech companies, especially the FANG Apple combination, specifically. To see if this is true, I looked at the returns on all US stocks, classified by sectors (as defined by S&P), in October, in the year to date and for 1-year and 5-year time periods. US Sector Market Cap Change. Source: S&P Capital IQI know that the S&P sector classifications are imperfect, but my priors seem to be wrong. While information technology, as a group, lost 8.76% of aggregate market capitalization in October 2018, the three worst sectors in the US market were energy, industrials and materials, all of which lost much more, in percentage terms, than technology. In fact, the two sectors that did the best were consumer staples and utilities, with the latter's performance also providing evidence that it is not interest rate fears that are primarily driving this market correction.

US Sector Market Cap Change. Source: S&P Capital IQI know that the S&P sector classifications are imperfect, but my priors seem to be wrong. While information technology, as a group, lost 8.76% of aggregate market capitalization in October 2018, the three worst sectors in the US market were energy, industrials and materials, all of which lost much more, in percentage terms, than technology. In fact, the two sectors that did the best were consumer staples and utilities, with the latter's performance also providing evidence that it is not interest rate fears that are primarily driving this market correction.

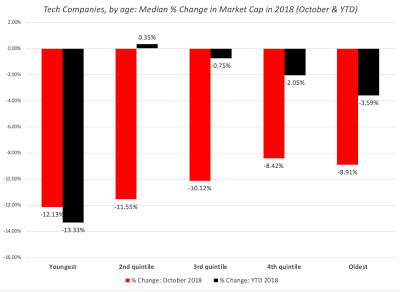

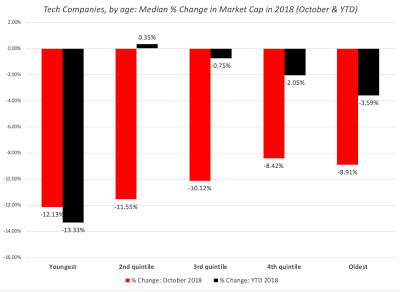

I have argued that, unlike two decades ago, technology companies now are now a diverse group, and many of them don't fit the "high growth, high risk" profile that people seem to still automatically give all tech companies. Using the terminology of corporate life cycles, tech companies run the gamut from old tech to middle-aged tech to young tech, and I have looked at how tech companies in each age grouping in the graph below (age is defined, relative to year of founding):

The median percentage change, in both October 2018 and YTD 2018, in market capitalization was greatest at the youngest tech companies. The median percentage change becomes smaller for older tech companies, in October 2018, but the effect for the four highest age classes is more mixed for the YTD numbers. That said, a much smaller median percentage change at the largest tech companies has a much biggest effect on the market, because of the market capitalization of these companies. That is the reason I look at the FANG stocks and Apple in the table below:

While the percentage change in stock prices at these companies is in line with the market drop, if Apple is included in the mix, the five companies collectively lost a staggering $276 billion in market capitalization between October 1 and October 26. accounting for almost 11.7% of the overall drop in market capitalization of US stocks. While investors in these stocks may feel merited in complaining about their losses, I would draw their attention to the third column, where I look at what these stocks have done since January 1, 2018, with the losses in October incorporated. Collectively, these five companies have added almost $521 billion in market capitalization since the start of the year, and without them, the overall market would have been down substantially.

While the percentage change in stock prices at these companies is in line with the market drop, if Apple is included in the mix, the five companies collectively lost a staggering $276 billion in market capitalization between October 1 and October 26. accounting for almost 11.7% of the overall drop in market capitalization of US stocks. While investors in these stocks may feel merited in complaining about their losses, I would draw their attention to the third column, where I look at what these stocks have done since January 1, 2018, with the losses in October incorporated. Collectively, these five companies have added almost $521 billion in market capitalization since the start of the year, and without them, the overall market would have been down substantially.

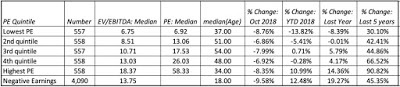

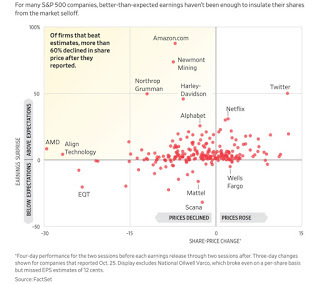

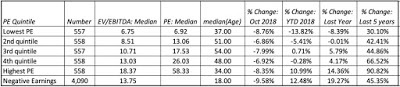

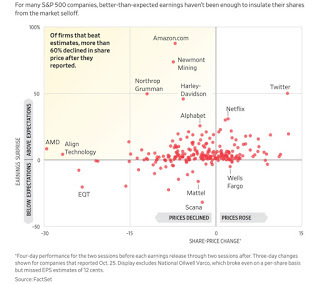

3. A Correction in Overvalued Stocks? For some value investors who have argued that investors were pushing up some stocks to unsustainable levels, the market correction has been vindication, a sign that the market is correcting its pricing mistakes and marking down the stocks that it had over priced the most. That may be plausible, and to see if it holds, I broke all US stocks, at the start of October, based upon PE ratios into six groupings (low to high PE and a separate one for negative earnings companies): PE Ratio at start of October 2018, using trailing 12 month earningsIf the selective correction argument is correct, you should expect to see the highest PE ratio and negative earnings companies drop the most in value and the companies with the lowest PE ratios be less affected. While negative earnings stocks have seen the market correction, during October 2018, there is no pattern across the other PE classes. In fact, the lowest PE ratio companies had the second worst record, in terms of price performance, among the groupings.

PE Ratio at start of October 2018, using trailing 12 month earningsIf the selective correction argument is correct, you should expect to see the highest PE ratio and negative earnings companies drop the most in value and the companies with the lowest PE ratios be less affected. While negative earnings stocks have seen the market correction, during October 2018, there is no pattern across the other PE classes. In fact, the lowest PE ratio companies had the second worst record, in terms of price performance, among the groupings.

4. A US Problem?

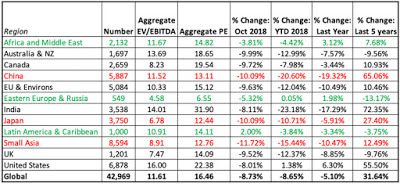

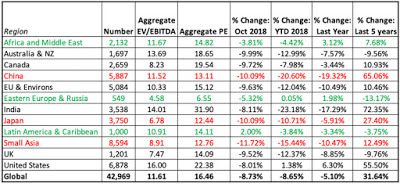

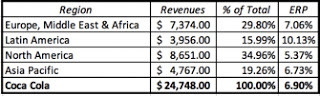

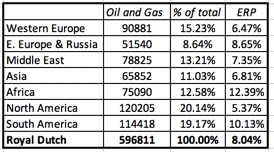

One of the lessons of the last decade is that much as countries would like to disconnect from the rest of the world and chart their own pathway to economic prosperity, they are joined at the hip by globalization, with crisis in one part of the world quickly affecting economies and markets in other parts. In October 2018, we had our share of global shocks, with the standoff between Italy and the EU and Saudi Arabia's Khashoggi problem taking top billing. To see how the market correction has played out in world markets, I broke global markets down into broad regional groupings and arrived at the following: Source: S&P Capital IQ, based upon headquarters geographyNote that these returns are all in US dollars, reflecting both the performance of the market and the currencies of each region. Asia seems to have been hit the worst this month, with China, Small Asia (South East Asia, Pakistan, Bangladesh) and Japan all seeing double digit declines in aggregate market capitalization. Latin America has had the best performance of the regional groupings, with the election surprise in Brazil driving its markets upwards during the month. The year-to-date numbers do tell a bigger story that has been glossed over in analysis. For much of 2018, the US market & economy has diverged from the rest of the globe, posting solid numbers (prior to October) whereas the rest of the world was struggling. It is possible that we are seeing an end to that divergence, suggesting that the US markets will move more closely with the other global markets going forward.

Source: S&P Capital IQ, based upon headquarters geographyNote that these returns are all in US dollars, reflecting both the performance of the market and the currencies of each region. Asia seems to have been hit the worst this month, with China, Small Asia (South East Asia, Pakistan, Bangladesh) and Japan all seeing double digit declines in aggregate market capitalization. Latin America has had the best performance of the regional groupings, with the election surprise in Brazil driving its markets upwards during the month. The year-to-date numbers do tell a bigger story that has been glossed over in analysis. For much of 2018, the US market & economy has diverged from the rest of the globe, posting solid numbers (prior to October) whereas the rest of the world was struggling. It is possible that we are seeing an end to that divergence, suggesting that the US markets will move more closely with the other global markets going forward.

5. Panic Attack?

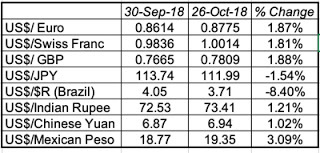

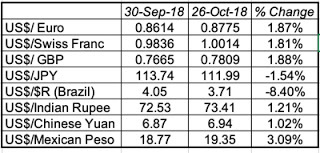

One of the more striking features of the markets during October 2018 has been that the stock market retreat, while substantial, has, for the most part, been orderly. In a panic-driven stock market sell off, you usually see a surge in government bond prices (and a drop in rates), a general flight to quality (US $ and safer companies) and a rise in the price of gold. As we noted in the earlier section, the market drop does not seem to be smaller at larger and more profitable companies, and government bond rates have not dropped. In addition, while the US dollar has had a strong year so far, especially against emerging market currencies, it generally did not see a flight to it in October 2018:

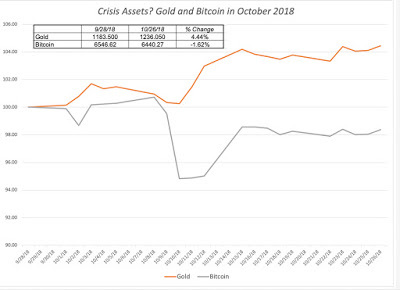

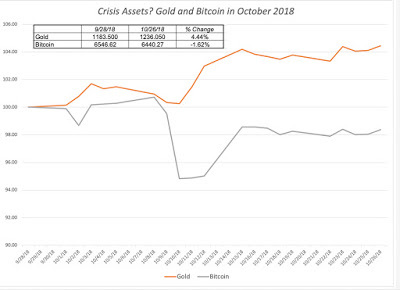

The dollar strengthened mildly against almost every currency during the month, and the only currency where there was a big move was against the Brazilian Reai, where it weakened, again on political news in Brazil. Note again that the market correction may be, at least partly, a delayed reaction to the strength of the US dollar leading into October, but the timing is still difficult to explain. Finally, I looked at gold prices in October 2018, in conjunction with bitcoin, since the latter has been promoted as millennial gold: It has been a good month for gold, with prices up 4.44%, though there is little sign of panic buying pushing up prices. It may be a little unfair to be passing judgment on Bitcoin, after one crisis, but if it is millennial gold, either millennials are unaware that there is a stock market sell off or they do not care.

It has been a good month for gold, with prices up 4.44%, though there is little sign of panic buying pushing up prices. It may be a little unfair to be passing judgment on Bitcoin, after one crisis, but if it is millennial gold, either millennials are unaware that there is a stock market sell off or they do not care.

Step 3: Review the fundamentals

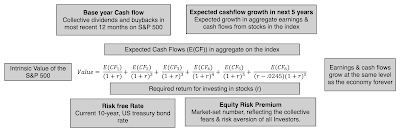

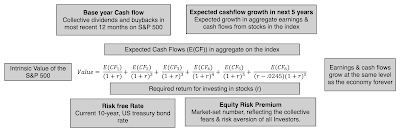

With the assessment of market pain behind us, we can turn to looking at the fundamentals, again looking for clues in why stocks have had such a tough month. While almost every factor affects stock prices, the effects have to show up in one of four places for fundamental value to change significantly: a shock to base year earnings or cash flows, a change in expected earnings/cash flow growth, a increase in the risk free rate or a change in the price of risk:

Since treasury bond rates have been stable through much of the month, I am going to look at one of the other three variables as the potential culprit.

Base Year Earnings/Cashflows: The earnings reports that have come out for companies in diverse sectors in the last two weeks seem to reinforce the strong earnings story. While there were a few like Caterpillar and 3M that reported headwinds from a stronger dollar, both companies also conveyed the message that they were able to pass the higher costs through to the customers. On the cash flow front, there were no high profile cessations of buybacks or dividends, and all signs point to the market delivering and perhaps beating the earnings and cash flows that we have estimated for 2018.Earnings Growth: This is a trickier component, since it is driven as much by actual data, as it is by perception. At the start of the year, the expectation that earnings growth would be strong for this year, helped both the tax law changes of last year and a strong economy. That growth has been delivered, but it is possible that investors are now doubtful about the sustainability of that earnings growth. That has not shown up yet in forecasted growth for next year, but it bears watching.Price of Equity Risk (Equity Risk Premium): If you have been reading my blog for a while, you are probably aware of my implied equity risk premium calculation, one that backs out a price of equity risk (equity risk premium) from the level of the index, expected cash flows and a growth rate. Holding cash flows and growth rate fixed for October, I have computed the implied equity risk premium by day. table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

On the cash flow front, there were no high profile cessations of buybacks or dividends, and all signs point to the market delivering and perhaps beating the earnings and cash flows that we have estimated for 2018.Earnings Growth: This is a trickier component, since it is driven as much by actual data, as it is by perception. At the start of the year, the expectation that earnings growth would be strong for this year, helped both the tax law changes of last year and a strong economy. That growth has been delivered, but it is possible that investors are now doubtful about the sustainability of that earnings growth. That has not shown up yet in forecasted growth for next year, but it bears watching.Price of Equity Risk (Equity Risk Premium): If you have been reading my blog for a while, you are probably aware of my implied equity risk premium calculation, one that backs out a price of equity risk (equity risk premium) from the level of the index, expected cash flows and a growth rate. Holding cash flows and growth rate fixed for October, I have computed the implied equity risk premium by day. table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

End of DayUS 10-yr T.BondS&P 500Implied ERPSpreadsheet9/28/183.06%2913.985.38%Download10/1/183.09%2924.595.36%Download10/2/183.05%2923.435.36%Download10/3/183.15%2925.515.35%Download10/4/183.19%2901.615.39%Download10/5/183.23%2885.575.41%Download10/8/183.22%2884.435.42%Download10/9/183.21%2880.345.43%Download10/10/183.22%2785.685.61%Download10/11/183.14%2728.375.73%Download10/12/183.15%2767.135.65%Download10/15/183.16%2750.795.68%Download10/16/183.16%2809.925.57%Download10/17/183.19%2809.215.56%Download10/18/183.17%2768.785.65%Download10/19/183.20%2767.785.64%Download10/22/183.20%2755.885.67%Download10/23/183.17%2740.695.70%Download10/24/183.10%2656.105.89%Download10/25/183.14%2705.575.78%Download10/26/183.08%2658.695.89%%DownloadIf cash flows and expected growth have not changed over the month, the price of equity risk has jumped from 5.38% at the start of the month to the 5.89% on October 26, putting it at the high end of equity risk premiums in the last decade.

You could attribute the higher equity risk premiums to global crises (in Italy and Saudi Arabia) but that would be a reach since the increase in risk premiums predates both crises. If you do lower expected earnings growth going forward, perhaps reflecting a delayed response to the stronger dollar and higher rates, the equity risk premium will drop. In fact, halving the expected growth rate from 2019 on from the current estimate of 7.29% to 4.71% (the compounded average annual earnings growth rate over the last 10 years) reduces the equity risk premium to 5.28%, but even that number is a healthy one, relative to historic norms. The bottom line is that, at least by my calculations, I am estimating an equity risk premium that seems fair, given macro and micro fundamentals and my risk preferences.

Step 4: Investment Action

One of the biggest perils of being reactive in a crisis is that it can knock you off your investment game and cause you to abandon your core philosophy. I don't believe that there is one investment philosophy that is right for every one, but I do believe that there is one that is right for you, and shifting away from it is a recipe for bad results. I am a “value” investor, though my definition of value is different from old-time value investing in two ways:

Under valued stocks can be found across sectors and the life cycle: I believe that we should try to assess fair value, not a conservative estimate of value, and that the value should include expected value added from future growth. To the critique that this is speculative, my answer is that everything other than cash-in-hand requires making assumptions about the future, and I am willing to go the distance. That is why, at different points in time, you have seen Twitter and Facebook in my portfolio in the past and may well see Netflix and Tesla in the future (just not now).Intrinsic value can change over time: I believe that intrinsic value is a dynamic number that changes over time, not only because new information may come out about a company. but also because the price of equity risk can change over time. That said, intrinsic values generally change less than market prices do, as mood and momentum shift. This has been a month of significant price drops in many companies, but assuming that they are therefore more likely to be under valued is a mistake, since the intrinsic values of these companies have also changed, because the ERP that I will be using to value the stocks on October 26, 2018, will be 5.89%, much higher than the 5.38% at the start of the month.Given my philosophy and a reading of the data, here is what I plan to do.

No change in asset allocation: I am not changing my asset allocation mix in significant ways, since I don't see a fundamental reason to do so. Revisit existing holdings: I normally revalue every company in my portfolio at least once a year, but after a month like this one, I will have to accelerate the process. Put simply, I have to make sure that at the current price for equity risk, and given expected cash flows, that my buys still remain buys and the sells remain sells.Bonus from short sales: I do have a portion of my portfolio that benefits from a sell off, primarily in short sales and those have provided partial offsets to my losses. I did sell short on Amazon and Apple at the start of the month, and while I would like to claim prescience, it was pure luck on timing, and the market downdraft during the month has helped me. Check out the biggest market losers: I plan to take a closer look at the stocks that have been pummeled the most during the month, including 3M and Caterpillar, to see if they are cheap at October 26 prices, and using an October 26 ERP in my valuation. Please note that this is not meant to be investment advice and your path back to investment serenity may be very different from mine!

YouTube Video

Step 1: Hit the pause buttonThe first casualty of crisis is good sense, as I mistake my panic response for instinct, and almost every action that I feel the urge to take in the heat of the moment is driven by fear and greed, not reason. No amount of rational thinking or studying behavioral finance will cure me of this affliction, since it is part of my make up as a human being, but there are three things that I find help me manage my reactions:Take a breath: When faced with fast-moving markets, I have to force myself to consciously slow down. It helps that I don't work as a trader or a portfolio manager, since part of your job is to look like you are in control, even when you are not. Turn off the noise: Turn back the clock about four decades and assume that you were a doctor, a lawyer or a factory worker with much of your wealth invested in stocks. If markets were having a bad day, odds were that you would not even have heard about it until you got home and turned on the news, and even then, you would have been fed scraps of information about Dow, perhaps a 2-minute discussion with a market expert, and you would have then turned on your favorite sitcom. Today, not only can you monitor your stocks every moment of your working day, you can trade on your lunch break and stream CNBC on to your desktop. That may make you a more informed investor, or at least an investor with more information, but I am not sure that constant feedback is healthy for your portfolio, especially in periods like this one. I don't have a Bloomberg terminal on my desk, a ticker tape running on my computer or stock apps on my phone, and I am happy that I don't during periods like this month.Don't play the blame game: Every market correction has its villains, and investors like to tag them. Central banks and governments are always good targets, since they have few defenders and have a history of triggering market meltdowns. The problem that I find with assigning blame to others is that it then relieves me of any responsibility, even for own mistakes, and thus makes it impossible to learn from them and take corrective action. Step 2: Assess the damage In an age of instant analysis and expert opinion, it is easy to get a skewed view of not only what is causing the market damage, but also where that damage is greatest. In my (limited) reading of market analyses during the last four weeks, I have seen at least a half a dozen hypotheses about the stock swoon, from it being the Fed's fault (as usual) to a long overdue tech company correction to it being a response to global crises (in Italy and Saudi Arabia). In keeping with the old adage of "trust, but verify", I decided to take a look at the data to see if there are answers in it to these questions.

1.The Fed's fault? As those of you who read my blog know well, I believe that the Fed has far less power than we think it does to set interest rates, but it is a convenient bogeyman. One explanation for the stock drop that has been making the rounds is that it is fear that Fed will raise rates too quickly in the future, that is causing stocks to swoon. Is that a plausible story? Yes, but if it is the reason for the market decline, you would have a difficult time explaining the movement in interest rates during October 2018:

Source: Federal Reserve (FRED)As stocks have gone through their pains since October 1, treasury bill and bond rates have remained steady, which would make little sense if the expectation is that they will rise in the near future. After all, if investors expect rates to rise soon, those rates will start going up now and not on cue, when the Fed acts.

Source: Federal Reserve (FRED)As stocks have gone through their pains since October 1, treasury bill and bond rates have remained steady, which would make little sense if the expectation is that they will rise in the near future. After all, if investors expect rates to rise soon, those rates will start going up now and not on cue, when the Fed acts.There is the possibility that this could be a delayed reaction to rates having gone up over the year already, with the 10-year treasury bond rate moving from 2.41% at the start of the year to 3.06% at the start of October 2018 and to a flattening yield curve (which has historically been a precursor to slower economic growth). Note though, that much of this movement in interest rates happened in the first six months of the year and you would need a reason for why stock prices would be moving four months later.

2. A Tech Meltdown? My view, based upon what I had been hearing and reading, and before I looked at the data, was that the October 2018 stock drop was being caused by tech companies, in general, and the large tech companies, especially the FANG Apple combination, specifically. To see if this is true, I looked at the returns on all US stocks, classified by sectors (as defined by S&P), in October, in the year to date and for 1-year and 5-year time periods.

US Sector Market Cap Change. Source: S&P Capital IQI know that the S&P sector classifications are imperfect, but my priors seem to be wrong. While information technology, as a group, lost 8.76% of aggregate market capitalization in October 2018, the three worst sectors in the US market were energy, industrials and materials, all of which lost much more, in percentage terms, than technology. In fact, the two sectors that did the best were consumer staples and utilities, with the latter's performance also providing evidence that it is not interest rate fears that are primarily driving this market correction.

US Sector Market Cap Change. Source: S&P Capital IQI know that the S&P sector classifications are imperfect, but my priors seem to be wrong. While information technology, as a group, lost 8.76% of aggregate market capitalization in October 2018, the three worst sectors in the US market were energy, industrials and materials, all of which lost much more, in percentage terms, than technology. In fact, the two sectors that did the best were consumer staples and utilities, with the latter's performance also providing evidence that it is not interest rate fears that are primarily driving this market correction. I have argued that, unlike two decades ago, technology companies now are now a diverse group, and many of them don't fit the "high growth, high risk" profile that people seem to still automatically give all tech companies. Using the terminology of corporate life cycles, tech companies run the gamut from old tech to middle-aged tech to young tech, and I have looked at how tech companies in each age grouping in the graph below (age is defined, relative to year of founding):

The median percentage change, in both October 2018 and YTD 2018, in market capitalization was greatest at the youngest tech companies. The median percentage change becomes smaller for older tech companies, in October 2018, but the effect for the four highest age classes is more mixed for the YTD numbers. That said, a much smaller median percentage change at the largest tech companies has a much biggest effect on the market, because of the market capitalization of these companies. That is the reason I look at the FANG stocks and Apple in the table below:

While the percentage change in stock prices at these companies is in line with the market drop, if Apple is included in the mix, the five companies collectively lost a staggering $276 billion in market capitalization between October 1 and October 26. accounting for almost 11.7% of the overall drop in market capitalization of US stocks. While investors in these stocks may feel merited in complaining about their losses, I would draw their attention to the third column, where I look at what these stocks have done since January 1, 2018, with the losses in October incorporated. Collectively, these five companies have added almost $521 billion in market capitalization since the start of the year, and without them, the overall market would have been down substantially.

While the percentage change in stock prices at these companies is in line with the market drop, if Apple is included in the mix, the five companies collectively lost a staggering $276 billion in market capitalization between October 1 and October 26. accounting for almost 11.7% of the overall drop in market capitalization of US stocks. While investors in these stocks may feel merited in complaining about their losses, I would draw their attention to the third column, where I look at what these stocks have done since January 1, 2018, with the losses in October incorporated. Collectively, these five companies have added almost $521 billion in market capitalization since the start of the year, and without them, the overall market would have been down substantially.3. A Correction in Overvalued Stocks? For some value investors who have argued that investors were pushing up some stocks to unsustainable levels, the market correction has been vindication, a sign that the market is correcting its pricing mistakes and marking down the stocks that it had over priced the most. That may be plausible, and to see if it holds, I broke all US stocks, at the start of October, based upon PE ratios into six groupings (low to high PE and a separate one for negative earnings companies):

PE Ratio at start of October 2018, using trailing 12 month earningsIf the selective correction argument is correct, you should expect to see the highest PE ratio and negative earnings companies drop the most in value and the companies with the lowest PE ratios be less affected. While negative earnings stocks have seen the market correction, during October 2018, there is no pattern across the other PE classes. In fact, the lowest PE ratio companies had the second worst record, in terms of price performance, among the groupings.

PE Ratio at start of October 2018, using trailing 12 month earningsIf the selective correction argument is correct, you should expect to see the highest PE ratio and negative earnings companies drop the most in value and the companies with the lowest PE ratios be less affected. While negative earnings stocks have seen the market correction, during October 2018, there is no pattern across the other PE classes. In fact, the lowest PE ratio companies had the second worst record, in terms of price performance, among the groupings. 4. A US Problem?

One of the lessons of the last decade is that much as countries would like to disconnect from the rest of the world and chart their own pathway to economic prosperity, they are joined at the hip by globalization, with crisis in one part of the world quickly affecting economies and markets in other parts. In October 2018, we had our share of global shocks, with the standoff between Italy and the EU and Saudi Arabia's Khashoggi problem taking top billing. To see how the market correction has played out in world markets, I broke global markets down into broad regional groupings and arrived at the following:

Source: S&P Capital IQ, based upon headquarters geographyNote that these returns are all in US dollars, reflecting both the performance of the market and the currencies of each region. Asia seems to have been hit the worst this month, with China, Small Asia (South East Asia, Pakistan, Bangladesh) and Japan all seeing double digit declines in aggregate market capitalization. Latin America has had the best performance of the regional groupings, with the election surprise in Brazil driving its markets upwards during the month. The year-to-date numbers do tell a bigger story that has been glossed over in analysis. For much of 2018, the US market & economy has diverged from the rest of the globe, posting solid numbers (prior to October) whereas the rest of the world was struggling. It is possible that we are seeing an end to that divergence, suggesting that the US markets will move more closely with the other global markets going forward.

Source: S&P Capital IQ, based upon headquarters geographyNote that these returns are all in US dollars, reflecting both the performance of the market and the currencies of each region. Asia seems to have been hit the worst this month, with China, Small Asia (South East Asia, Pakistan, Bangladesh) and Japan all seeing double digit declines in aggregate market capitalization. Latin America has had the best performance of the regional groupings, with the election surprise in Brazil driving its markets upwards during the month. The year-to-date numbers do tell a bigger story that has been glossed over in analysis. For much of 2018, the US market & economy has diverged from the rest of the globe, posting solid numbers (prior to October) whereas the rest of the world was struggling. It is possible that we are seeing an end to that divergence, suggesting that the US markets will move more closely with the other global markets going forward.5. Panic Attack?

One of the more striking features of the markets during October 2018 has been that the stock market retreat, while substantial, has, for the most part, been orderly. In a panic-driven stock market sell off, you usually see a surge in government bond prices (and a drop in rates), a general flight to quality (US $ and safer companies) and a rise in the price of gold. As we noted in the earlier section, the market drop does not seem to be smaller at larger and more profitable companies, and government bond rates have not dropped. In addition, while the US dollar has had a strong year so far, especially against emerging market currencies, it generally did not see a flight to it in October 2018:

The dollar strengthened mildly against almost every currency during the month, and the only currency where there was a big move was against the Brazilian Reai, where it weakened, again on political news in Brazil. Note again that the market correction may be, at least partly, a delayed reaction to the strength of the US dollar leading into October, but the timing is still difficult to explain. Finally, I looked at gold prices in October 2018, in conjunction with bitcoin, since the latter has been promoted as millennial gold:

It has been a good month for gold, with prices up 4.44%, though there is little sign of panic buying pushing up prices. It may be a little unfair to be passing judgment on Bitcoin, after one crisis, but if it is millennial gold, either millennials are unaware that there is a stock market sell off or they do not care.

It has been a good month for gold, with prices up 4.44%, though there is little sign of panic buying pushing up prices. It may be a little unfair to be passing judgment on Bitcoin, after one crisis, but if it is millennial gold, either millennials are unaware that there is a stock market sell off or they do not care. Step 3: Review the fundamentals

With the assessment of market pain behind us, we can turn to looking at the fundamentals, again looking for clues in why stocks have had such a tough month. While almost every factor affects stock prices, the effects have to show up in one of four places for fundamental value to change significantly: a shock to base year earnings or cash flows, a change in expected earnings/cash flow growth, a increase in the risk free rate or a change in the price of risk:

Since treasury bond rates have been stable through much of the month, I am going to look at one of the other three variables as the potential culprit.

Base Year Earnings/Cashflows: The earnings reports that have come out for companies in diverse sectors in the last two weeks seem to reinforce the strong earnings story. While there were a few like Caterpillar and 3M that reported headwinds from a stronger dollar, both companies also conveyed the message that they were able to pass the higher costs through to the customers.

On the cash flow front, there were no high profile cessations of buybacks or dividends, and all signs point to the market delivering and perhaps beating the earnings and cash flows that we have estimated for 2018.Earnings Growth: This is a trickier component, since it is driven as much by actual data, as it is by perception. At the start of the year, the expectation that earnings growth would be strong for this year, helped both the tax law changes of last year and a strong economy. That growth has been delivered, but it is possible that investors are now doubtful about the sustainability of that earnings growth. That has not shown up yet in forecasted growth for next year, but it bears watching.Price of Equity Risk (Equity Risk Premium): If you have been reading my blog for a while, you are probably aware of my implied equity risk premium calculation, one that backs out a price of equity risk (equity risk premium) from the level of the index, expected cash flows and a growth rate. Holding cash flows and growth rate fixed for October, I have computed the implied equity risk premium by day. table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; }

On the cash flow front, there were no high profile cessations of buybacks or dividends, and all signs point to the market delivering and perhaps beating the earnings and cash flows that we have estimated for 2018.Earnings Growth: This is a trickier component, since it is driven as much by actual data, as it is by perception. At the start of the year, the expectation that earnings growth would be strong for this year, helped both the tax law changes of last year and a strong economy. That growth has been delivered, but it is possible that investors are now doubtful about the sustainability of that earnings growth. That has not shown up yet in forecasted growth for next year, but it bears watching.Price of Equity Risk (Equity Risk Premium): If you have been reading my blog for a while, you are probably aware of my implied equity risk premium calculation, one that backs out a price of equity risk (equity risk premium) from the level of the index, expected cash flows and a growth rate. Holding cash flows and growth rate fixed for October, I have computed the implied equity risk premium by day. table.tableizer-table { font-size: 12px; border: 1px solid #CCC; font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; } .tableizer-table td { padding: 4px; margin: 3px; border: 1px solid #CCC; } .tableizer-table th { background-color: #104E8B; color: #FFF; font-weight: bold; } End of DayUS 10-yr T.BondS&P 500Implied ERPSpreadsheet9/28/183.06%2913.985.38%Download10/1/183.09%2924.595.36%Download10/2/183.05%2923.435.36%Download10/3/183.15%2925.515.35%Download10/4/183.19%2901.615.39%Download10/5/183.23%2885.575.41%Download10/8/183.22%2884.435.42%Download10/9/183.21%2880.345.43%Download10/10/183.22%2785.685.61%Download10/11/183.14%2728.375.73%Download10/12/183.15%2767.135.65%Download10/15/183.16%2750.795.68%Download10/16/183.16%2809.925.57%Download10/17/183.19%2809.215.56%Download10/18/183.17%2768.785.65%Download10/19/183.20%2767.785.64%Download10/22/183.20%2755.885.67%Download10/23/183.17%2740.695.70%Download10/24/183.10%2656.105.89%Download10/25/183.14%2705.575.78%Download10/26/183.08%2658.695.89%%DownloadIf cash flows and expected growth have not changed over the month, the price of equity risk has jumped from 5.38% at the start of the month to the 5.89% on October 26, putting it at the high end of equity risk premiums in the last decade.

You could attribute the higher equity risk premiums to global crises (in Italy and Saudi Arabia) but that would be a reach since the increase in risk premiums predates both crises. If you do lower expected earnings growth going forward, perhaps reflecting a delayed response to the stronger dollar and higher rates, the equity risk premium will drop. In fact, halving the expected growth rate from 2019 on from the current estimate of 7.29% to 4.71% (the compounded average annual earnings growth rate over the last 10 years) reduces the equity risk premium to 5.28%, but even that number is a healthy one, relative to historic norms. The bottom line is that, at least by my calculations, I am estimating an equity risk premium that seems fair, given macro and micro fundamentals and my risk preferences.

Step 4: Investment Action

One of the biggest perils of being reactive in a crisis is that it can knock you off your investment game and cause you to abandon your core philosophy. I don't believe that there is one investment philosophy that is right for every one, but I do believe that there is one that is right for you, and shifting away from it is a recipe for bad results. I am a “value” investor, though my definition of value is different from old-time value investing in two ways:

Under valued stocks can be found across sectors and the life cycle: I believe that we should try to assess fair value, not a conservative estimate of value, and that the value should include expected value added from future growth. To the critique that this is speculative, my answer is that everything other than cash-in-hand requires making assumptions about the future, and I am willing to go the distance. That is why, at different points in time, you have seen Twitter and Facebook in my portfolio in the past and may well see Netflix and Tesla in the future (just not now).Intrinsic value can change over time: I believe that intrinsic value is a dynamic number that changes over time, not only because new information may come out about a company. but also because the price of equity risk can change over time. That said, intrinsic values generally change less than market prices do, as mood and momentum shift. This has been a month of significant price drops in many companies, but assuming that they are therefore more likely to be under valued is a mistake, since the intrinsic values of these companies have also changed, because the ERP that I will be using to value the stocks on October 26, 2018, will be 5.89%, much higher than the 5.38% at the start of the month.Given my philosophy and a reading of the data, here is what I plan to do.

No change in asset allocation: I am not changing my asset allocation mix in significant ways, since I don't see a fundamental reason to do so. Revisit existing holdings: I normally revalue every company in my portfolio at least once a year, but after a month like this one, I will have to accelerate the process. Put simply, I have to make sure that at the current price for equity risk, and given expected cash flows, that my buys still remain buys and the sells remain sells.Bonus from short sales: I do have a portion of my portfolio that benefits from a sell off, primarily in short sales and those have provided partial offsets to my losses. I did sell short on Amazon and Apple at the start of the month, and while I would like to claim prescience, it was pure luck on timing, and the market downdraft during the month has helped me. Check out the biggest market losers: I plan to take a closer look at the stocks that have been pummeled the most during the month, including 3M and Caterpillar, to see if they are cheap at October 26 prices, and using an October 26 ERP in my valuation. Please note that this is not meant to be investment advice and your path back to investment serenity may be very different from mine!

YouTube Video

Published on October 29, 2018 02:58

October 16, 2018

High and higher: The Money in Marijuana!

In 1992, when Bill Clinton was running for president of the United States, and was asked whether he had ever smoked marijuana, he responded that he had, but that he did not inhale, reflecting the fear that being viewed as a weed-smoker would lay low his presidential ambitions. How times have changed! Today, smoking marijuana recreationally is legal in nine states, and medical marijuana in twenty nine states, in the United States. Outside the United States, much of Europe has always taken a much more sanguine view of cannabis, and on October 17, 2018, Canada will become the second country (after Uruguay) in the world to legalize the recreational use of the product. In conjunction with this development, new companies are entering the market, hoping to take advantage of what they see as a “big” market, and excited investors are rewarding them with large market capitalizations. I have never smoked marijuana, but on my daily walks on the boardwalks of San Diego, I have been inhaling a lot of second-hand smoke, leaving me a little light headed as I write this post. So, read on at your own risk!

The Macro Big Picture

While there is much to debate about how this market will evolve over time, and whether investors and businesses can make money of that evolution, there is one fact that is not debatable. The cannabis market will be a big one, in terms of users and revenues, drawing in large numbers of the population. To get a sense of the growth in this business, consider some nascent statistics from the soon-to-be legalized Canadian recreational market:Lots of people smoke weed: According to the Canadian national census, 42.5% of Canadians have tried Marijuana and about 16% had used it in the recent past (last 3 months), with the percentages climbing among younger Canadians, where one in three being recent users.And spend money to do so: The total revenues from recreational marijuana sales in Canada alone is expected to be $7-8 billion in 2020 and grow at a healthy rate after that. Some of this will represent a shifting from the illegal market (estimated at close to $5 billion in 2017) and some of it will represent new users drawn in its legal status.There is also information that can be gleaned about the future of this business from the states in the United States that have legalized marijuana.In California, where legalization occurred at the start of 2018, revenues from cannabis are expected to be about $3.4 billion in 2018, but that is not a huge jump from the $3 billion in revenues in the illegal market in 2017. One reason, at least in California, is that legal marijuana, with testing, regulation and taxes, is much more expensive than that obtained in the illegal markets that existed pre-legalization. In Colorado, where recreational marijuana use has been legal since 2014, the revenues from selling marijuana have increased from $996 million in 2015 to $1,25 billion in 2016 to $1,47 billion in 2017, representing solid, but not spectacular, growth. Marijuana-related businesses in Colorado have benefited from the revenue growth but have, for the most part, been unable to convert that growth into solid profits, partly because of the regulatory and tax overlay that they have had to navigate. With the limited data that we have from both Canada and the US states that have legalized marijuana, here are some general conclusions that come to mind.The illegal marijuana market will persist after legalization: The illegal weed business will continue, even after legalization, for many reasons. One is that legalization brings costs, regulations and taxes, which make the cost of legal weed higher than its illegal counterpart. The other is cultural, where a segment of long-time weed smokers will be reluctant to give up their traditional ways of acquiring and using weed. From a business standpoint, this will mean that the legal weed businesses will have to share the market with unregulated and untaxed competitors, reducing both revenues and profitability.There will be growth in recreational marijuana sales, but it will not be exponential: For those who are expecting a sudden surge of new users, as a result of legalization, the results from the parts of the world that have legalized should be sobering. In most of these parts, to the extent that society and law enforcement had already turned a blind eye to enforcing marijuana laws before legalization, there was no sea change in legal consequences from weed smoking. The medical marijuana market growth will be driven more by research indicating its value in health care than by popularity contests. The bad news is that this will require navigating the time-consuming and cash-burning FDA regulatory approval process but the good news is that once approved, there is less likely to be pushback, cultural or legal, against its use. It is a safe prediction that medical marijuana will be legal in all of the United States far sooner than recreational marijuana.Federal laws matter: If you are a company in the weed business in one of the nine states that has legalized recreational marijuana, you still face a quandary. While your operations may be legal in the state that you operate in, you are at risk any time your operations require you to cross state lines and as we noted with Colorado businesses, when you pay federal taxes. Since most financial service firms operate across state borders and are regulated by Federal entities, it has also meant that even legal businesses in this space have had trouble raising funding or borrowing money from banks.In spite of all of these caveats, there is optimism about growth in this market, with the more conservative forecasters predicting that global revenues from marijuana sales will increase to $70 billion in 2024, triple the sales today, and the more daring ones predicting close to $150 billion in sales.

The Business Question If the marijuana market is likely to grow strongly, it should be a good market to operate a business in, right? Not all big businesses are profitable or value creating, since for a big business to be value creating, it has to come with competitive advantages or barriers to entry. If you are an investor in this space, you also have to start thinking about how companies will set themselves apart from each other, once the business matures. To see how companies in this business will evolve, it is important that you separate the recreational from the medical cannabis businesses, since each will face different challenges.

I. Recreational Cannabis

Like tobacco and alcohol, the recreational marijuana business will grow with a wink and a nod towards its side costs, and potential to be a gateway to more potent and addictive substances. Like tobacco and alcohol, marijuana will face both constraints on who it can be sold to, as well as lawsuits down the road. Before you take issue with me for taking a negative view of marijuana, note that this is not a bad path to follow, given that tobacco and alcohol have been solid money-makers for decades. The question then becomes whether, like alcohol and tobacco, cannabis will become a brand-name driven business, where having a stronger brand name allows the winners to charge higher prices and earn better margins, or whether it devolves into a commodity business, where there is little to differentiate between the offerings of different companies, leading to commoditization and low margins. If it is the former, the most successful businesses in the space will bring marketing and branding skills to the table and if it is the latter, it will be economies of scale, and low-cost production that will be the differentiator.

II. Medical Cannabis

The medical marijuana business will more closely resemble the pharmaceutical business, where you will have to work with health care regulations and economics. Success in this business will come from finding a blockbuster cannabis-based drug that can then be sold at premium prices. If our experience with young pharmaceutical and biotech companies is an indicator, this would suggest that to succeed in this business, a company will need continued access to capital from investors with patience, a strong research presence and an understanding of the regulatory approval process. The company will also generate more value in health care systems where drug companies have pricing power, making the US market a much more lucrative one than the Canadian one. The differences between the two businesses are stark enough that you can argue that it will be difficult for a company to operate in both businesses without running into problems, sooner or later.

Investment considerations So, should you invest in this business or stay away until it becomes more mature? While there is an argument for waiting, if you are risk averse, it will also mean that you will lose out on the biggest rewards. If you are exploring your options today, you have to start by assessing your investment choices and pick the one that you are most comfortable with.

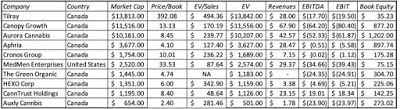

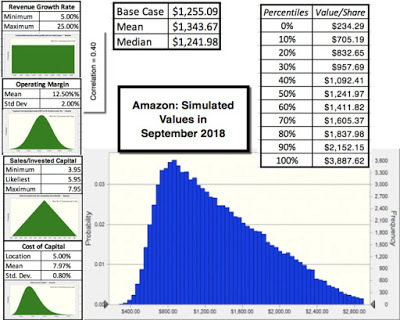

The Investment Landscape This is a young and evolving business, with the Canadian legalization drawing more firms into the market. Not only are the companies on the list of public companies in the sector recent listings, but almost all of them have small revenues and big losses. While that, by itself, is likely to drive away old time value investors, it is worth noting that at a this early stage in the business life cycle, these losses are a feature, not a bug. Looking at just the top 10 companies, in terms of market cap, on the cannabis business, here is what I see:

Largest Publicly Traded Cannabis Companies- October 2018 Note that the biggest company on the list is Tilray, a company that went publicly only a few months ago, with revenues that barely register ($28 million) and operating losses. Tilray made the news right after its IPO, with its stock price increasing ten-fold in the weeks after, before losing almost half of its value in the weeks after. Canopy Growth, the largest and most established company on this list, has the highest revenues at $68 million. More generally, Canadian companies dominate the list and all of them trade at astronomical multiples of book value.

Largest Publicly Traded Cannabis Companies- October 2018 Note that the biggest company on the list is Tilray, a company that went publicly only a few months ago, with revenues that barely register ($28 million) and operating losses. Tilray made the news right after its IPO, with its stock price increasing ten-fold in the weeks after, before losing almost half of its value in the weeks after. Canopy Growth, the largest and most established company on this list, has the highest revenues at $68 million. More generally, Canadian companies dominate the list and all of them trade at astronomical multiples of book value.

As new companies flock into the market, the list of publicly traded companies is only going to get longer, and at least for the foreseeable future, most of them will continue to lose money. Adding to the chaos, existing companies that have logical reasons to enter this business (tobacco & alcohol in the recreational and pharmaceuticals in the medical) but have held back will enter, as the stigma of being in the business fades, and with it, the federal handicaps imposed for being in the business. Put simply, this business, like many other young and potentially big markets, seems to be in the throes of what I called the big market delusion in a post that I had about online advertising companies a few years ago.

Trading and Investing Like all young businesses, this segment is currently dominated by trading and pricing, not investing and valuation. Put differently, companies are being priced based upon the size of the potential market and incremental information. Put simply, small and seemingly insignificant news stories will cause big swings in stock prices. Thus, there is no fundamental rationale you can give for why Tilray’s stock has behaved the way it has since it's IPO. It is driven by mood and momentum. If you are a good trader, this is a great time to play the game, since you can use your skills at detecting momentum shifts to make money as the stock goes up and again as it goes down. Since I am a terrible trader, I will leave it up to to you to decide whether you want to play the game.

If you are an investor, you want to invest on the expectation that there is more value in these companies than you are paying up front, for your equity stake. As I see it, here are your choices:The Concentrated Pick: Pick a stock or two that you believe is most suited to succeed in the business, as it matures. Thus, if you believe that the business is going to get commoditized and that the winner will be the one with the lowest costs, you should target a company like Canopy Growth, a company that seems to be pushing towards making itself the low-cost leader in the growth end of the business. If, in contrast, you believe that this is a business where branding and marketing will set you apart, you should focus on a company that is building itself up through marketing and celebrity endorsements. To succeed at this strategy, you have to be right on both your macro assessment and your company pick, but if you are, this approach has the potential to have the biggest payoff. Spread your bets: If your views about how the business will evolve are diffuse, but you do believe that there will be strong overall revenue growth and ultimate profitability, you can buy a portfolio of marijuana stocks. In fact, there is an ETF (MJ) composed primarily of cannabis-related stocks, with a modest expense ratio; its ten biggest holdings are all marijuana stocks, comprising 62% of the portfolio. The upside is that you just have to be right, on average, for this strategy to pay off, but the downside is that these companies are all richly priced, given the overall optimism about the market today. You also have to worry that the ultimate winner may not be on the list of stocks that are listed today, but a new entrant who has not shown up yet. If you are willing to wait for a correction, and there will be one, you may be able to get into the ETF at a much more reasonable price.The Indirect Play: Watch for established players to also jump in, with tobacco and alcohol stocks entering the recreational weed business, and pharmaceutical companies the medical weed business. You may get a better payoff investing in these established companies, many of which are priced for low growth and declining margins. One example is Scott’s Miracle-Gro, for instance, which has a growing weed subsidiary called Hawthorne Gardening. Another is GW Pharmaceuticals that has cannabis-based drugs in production for epilepsy and MS.It may be indication of my age, but I really don’t have a strong enough handle on this market and what makes it tick to make an early bet on competitive advantages. So, I will pass on picking the one or two winners in the market. Given how euphoric investors have been since the legalization of weed in Canada in pushing up cannabis stock prices, I think this is the wrong time to buy the ETF, especially since sector is going to draw in new players. That leaves me with the third and final choice, which is to invest in a company that is not viewed as being in the business but has a significant stake in it nevertheless. At current stock prices, neither Scott Miracle-Gro nor GW Pharmaceuticals looks like a good bet (I valued Scott Miracle-Gro at about $55, below its current stock price of $70.), but I think that my choices will get richer in the years to come. I can wait, and while I do, I think I will take another walk on the boardwalk!

YouTube Video

The Macro Big Picture

While there is much to debate about how this market will evolve over time, and whether investors and businesses can make money of that evolution, there is one fact that is not debatable. The cannabis market will be a big one, in terms of users and revenues, drawing in large numbers of the population. To get a sense of the growth in this business, consider some nascent statistics from the soon-to-be legalized Canadian recreational market:Lots of people smoke weed: According to the Canadian national census, 42.5% of Canadians have tried Marijuana and about 16% had used it in the recent past (last 3 months), with the percentages climbing among younger Canadians, where one in three being recent users.And spend money to do so: The total revenues from recreational marijuana sales in Canada alone is expected to be $7-8 billion in 2020 and grow at a healthy rate after that. Some of this will represent a shifting from the illegal market (estimated at close to $5 billion in 2017) and some of it will represent new users drawn in its legal status.There is also information that can be gleaned about the future of this business from the states in the United States that have legalized marijuana.In California, where legalization occurred at the start of 2018, revenues from cannabis are expected to be about $3.4 billion in 2018, but that is not a huge jump from the $3 billion in revenues in the illegal market in 2017. One reason, at least in California, is that legal marijuana, with testing, regulation and taxes, is much more expensive than that obtained in the illegal markets that existed pre-legalization. In Colorado, where recreational marijuana use has been legal since 2014, the revenues from selling marijuana have increased from $996 million in 2015 to $1,25 billion in 2016 to $1,47 billion in 2017, representing solid, but not spectacular, growth. Marijuana-related businesses in Colorado have benefited from the revenue growth but have, for the most part, been unable to convert that growth into solid profits, partly because of the regulatory and tax overlay that they have had to navigate. With the limited data that we have from both Canada and the US states that have legalized marijuana, here are some general conclusions that come to mind.The illegal marijuana market will persist after legalization: The illegal weed business will continue, even after legalization, for many reasons. One is that legalization brings costs, regulations and taxes, which make the cost of legal weed higher than its illegal counterpart. The other is cultural, where a segment of long-time weed smokers will be reluctant to give up their traditional ways of acquiring and using weed. From a business standpoint, this will mean that the legal weed businesses will have to share the market with unregulated and untaxed competitors, reducing both revenues and profitability.There will be growth in recreational marijuana sales, but it will not be exponential: For those who are expecting a sudden surge of new users, as a result of legalization, the results from the parts of the world that have legalized should be sobering. In most of these parts, to the extent that society and law enforcement had already turned a blind eye to enforcing marijuana laws before legalization, there was no sea change in legal consequences from weed smoking. The medical marijuana market growth will be driven more by research indicating its value in health care than by popularity contests. The bad news is that this will require navigating the time-consuming and cash-burning FDA regulatory approval process but the good news is that once approved, there is less likely to be pushback, cultural or legal, against its use. It is a safe prediction that medical marijuana will be legal in all of the United States far sooner than recreational marijuana.Federal laws matter: If you are a company in the weed business in one of the nine states that has legalized recreational marijuana, you still face a quandary. While your operations may be legal in the state that you operate in, you are at risk any time your operations require you to cross state lines and as we noted with Colorado businesses, when you pay federal taxes. Since most financial service firms operate across state borders and are regulated by Federal entities, it has also meant that even legal businesses in this space have had trouble raising funding or borrowing money from banks.In spite of all of these caveats, there is optimism about growth in this market, with the more conservative forecasters predicting that global revenues from marijuana sales will increase to $70 billion in 2024, triple the sales today, and the more daring ones predicting close to $150 billion in sales.

The Business Question If the marijuana market is likely to grow strongly, it should be a good market to operate a business in, right? Not all big businesses are profitable or value creating, since for a big business to be value creating, it has to come with competitive advantages or barriers to entry. If you are an investor in this space, you also have to start thinking about how companies will set themselves apart from each other, once the business matures. To see how companies in this business will evolve, it is important that you separate the recreational from the medical cannabis businesses, since each will face different challenges.

I. Recreational Cannabis

Like tobacco and alcohol, the recreational marijuana business will grow with a wink and a nod towards its side costs, and potential to be a gateway to more potent and addictive substances. Like tobacco and alcohol, marijuana will face both constraints on who it can be sold to, as well as lawsuits down the road. Before you take issue with me for taking a negative view of marijuana, note that this is not a bad path to follow, given that tobacco and alcohol have been solid money-makers for decades. The question then becomes whether, like alcohol and tobacco, cannabis will become a brand-name driven business, where having a stronger brand name allows the winners to charge higher prices and earn better margins, or whether it devolves into a commodity business, where there is little to differentiate between the offerings of different companies, leading to commoditization and low margins. If it is the former, the most successful businesses in the space will bring marketing and branding skills to the table and if it is the latter, it will be economies of scale, and low-cost production that will be the differentiator.

II. Medical Cannabis

The medical marijuana business will more closely resemble the pharmaceutical business, where you will have to work with health care regulations and economics. Success in this business will come from finding a blockbuster cannabis-based drug that can then be sold at premium prices. If our experience with young pharmaceutical and biotech companies is an indicator, this would suggest that to succeed in this business, a company will need continued access to capital from investors with patience, a strong research presence and an understanding of the regulatory approval process. The company will also generate more value in health care systems where drug companies have pricing power, making the US market a much more lucrative one than the Canadian one. The differences between the two businesses are stark enough that you can argue that it will be difficult for a company to operate in both businesses without running into problems, sooner or later.

Investment considerations So, should you invest in this business or stay away until it becomes more mature? While there is an argument for waiting, if you are risk averse, it will also mean that you will lose out on the biggest rewards. If you are exploring your options today, you have to start by assessing your investment choices and pick the one that you are most comfortable with.

The Investment Landscape This is a young and evolving business, with the Canadian legalization drawing more firms into the market. Not only are the companies on the list of public companies in the sector recent listings, but almost all of them have small revenues and big losses. While that, by itself, is likely to drive away old time value investors, it is worth noting that at a this early stage in the business life cycle, these losses are a feature, not a bug. Looking at just the top 10 companies, in terms of market cap, on the cannabis business, here is what I see:

Largest Publicly Traded Cannabis Companies- October 2018 Note that the biggest company on the list is Tilray, a company that went publicly only a few months ago, with revenues that barely register ($28 million) and operating losses. Tilray made the news right after its IPO, with its stock price increasing ten-fold in the weeks after, before losing almost half of its value in the weeks after. Canopy Growth, the largest and most established company on this list, has the highest revenues at $68 million. More generally, Canadian companies dominate the list and all of them trade at astronomical multiples of book value.

Largest Publicly Traded Cannabis Companies- October 2018 Note that the biggest company on the list is Tilray, a company that went publicly only a few months ago, with revenues that barely register ($28 million) and operating losses. Tilray made the news right after its IPO, with its stock price increasing ten-fold in the weeks after, before losing almost half of its value in the weeks after. Canopy Growth, the largest and most established company on this list, has the highest revenues at $68 million. More generally, Canadian companies dominate the list and all of them trade at astronomical multiples of book value.As new companies flock into the market, the list of publicly traded companies is only going to get longer, and at least for the foreseeable future, most of them will continue to lose money. Adding to the chaos, existing companies that have logical reasons to enter this business (tobacco & alcohol in the recreational and pharmaceuticals in the medical) but have held back will enter, as the stigma of being in the business fades, and with it, the federal handicaps imposed for being in the business. Put simply, this business, like many other young and potentially big markets, seems to be in the throes of what I called the big market delusion in a post that I had about online advertising companies a few years ago.

Trading and Investing Like all young businesses, this segment is currently dominated by trading and pricing, not investing and valuation. Put differently, companies are being priced based upon the size of the potential market and incremental information. Put simply, small and seemingly insignificant news stories will cause big swings in stock prices. Thus, there is no fundamental rationale you can give for why Tilray’s stock has behaved the way it has since it's IPO. It is driven by mood and momentum. If you are a good trader, this is a great time to play the game, since you can use your skills at detecting momentum shifts to make money as the stock goes up and again as it goes down. Since I am a terrible trader, I will leave it up to to you to decide whether you want to play the game.

If you are an investor, you want to invest on the expectation that there is more value in these companies than you are paying up front, for your equity stake. As I see it, here are your choices:The Concentrated Pick: Pick a stock or two that you believe is most suited to succeed in the business, as it matures. Thus, if you believe that the business is going to get commoditized and that the winner will be the one with the lowest costs, you should target a company like Canopy Growth, a company that seems to be pushing towards making itself the low-cost leader in the growth end of the business. If, in contrast, you believe that this is a business where branding and marketing will set you apart, you should focus on a company that is building itself up through marketing and celebrity endorsements. To succeed at this strategy, you have to be right on both your macro assessment and your company pick, but if you are, this approach has the potential to have the biggest payoff. Spread your bets: If your views about how the business will evolve are diffuse, but you do believe that there will be strong overall revenue growth and ultimate profitability, you can buy a portfolio of marijuana stocks. In fact, there is an ETF (MJ) composed primarily of cannabis-related stocks, with a modest expense ratio; its ten biggest holdings are all marijuana stocks, comprising 62% of the portfolio. The upside is that you just have to be right, on average, for this strategy to pay off, but the downside is that these companies are all richly priced, given the overall optimism about the market today. You also have to worry that the ultimate winner may not be on the list of stocks that are listed today, but a new entrant who has not shown up yet. If you are willing to wait for a correction, and there will be one, you may be able to get into the ETF at a much more reasonable price.The Indirect Play: Watch for established players to also jump in, with tobacco and alcohol stocks entering the recreational weed business, and pharmaceutical companies the medical weed business. You may get a better payoff investing in these established companies, many of which are priced for low growth and declining margins. One example is Scott’s Miracle-Gro, for instance, which has a growing weed subsidiary called Hawthorne Gardening. Another is GW Pharmaceuticals that has cannabis-based drugs in production for epilepsy and MS.It may be indication of my age, but I really don’t have a strong enough handle on this market and what makes it tick to make an early bet on competitive advantages. So, I will pass on picking the one or two winners in the market. Given how euphoric investors have been since the legalization of weed in Canada in pushing up cannabis stock prices, I think this is the wrong time to buy the ETF, especially since sector is going to draw in new players. That leaves me with the third and final choice, which is to invest in a company that is not viewed as being in the business but has a significant stake in it nevertheless. At current stock prices, neither Scott Miracle-Gro nor GW Pharmaceuticals looks like a good bet (I valued Scott Miracle-Gro at about $55, below its current stock price of $70.), but I think that my choices will get richer in the years to come. I can wait, and while I do, I think I will take another walk on the boardwalk!

YouTube Video

Published on October 16, 2018 11:32

September 21, 2018

Amazon and Apple at a Trillion $: A Follow-up on Uncertainty and Catalysts!

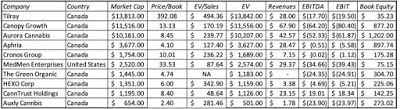

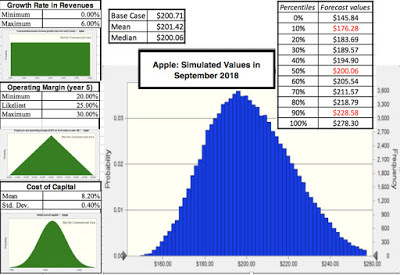

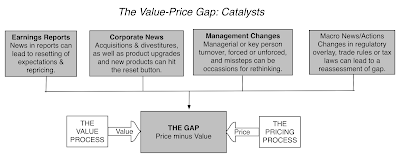

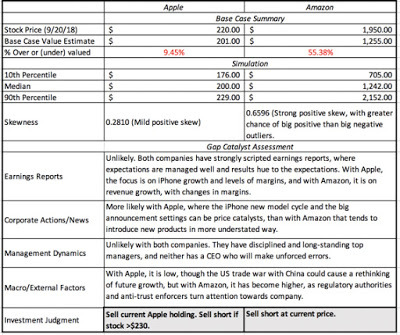

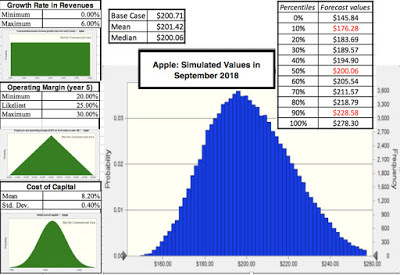

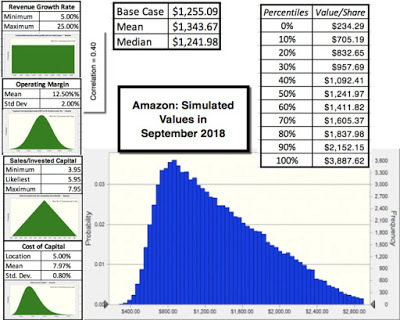

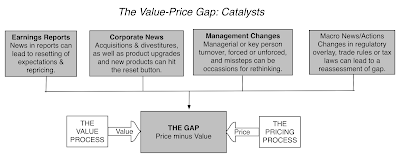

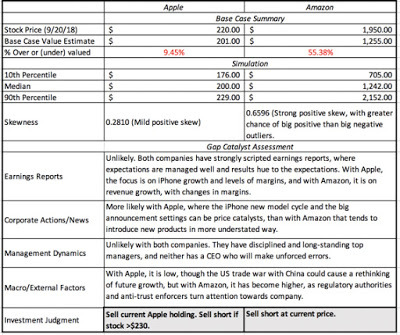

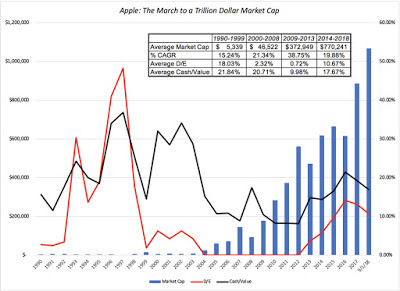

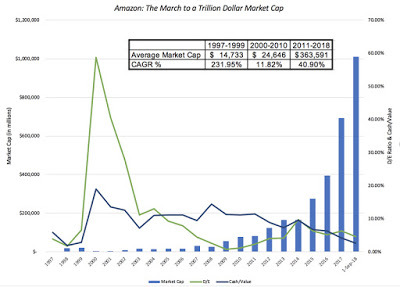

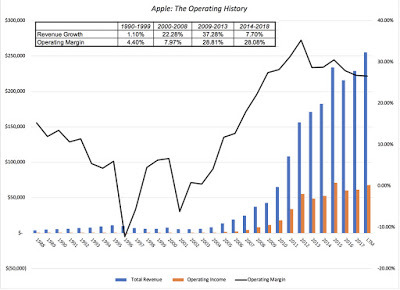

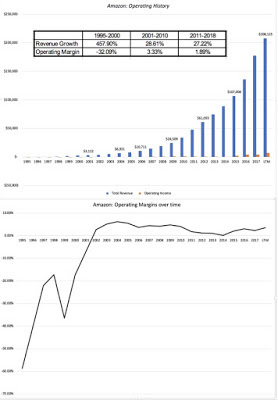

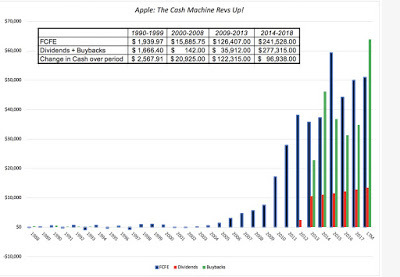

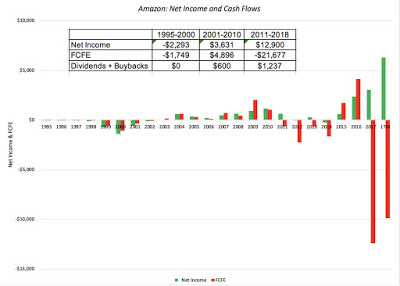

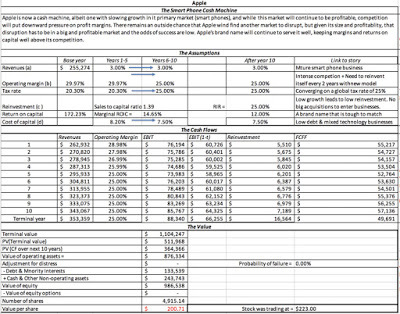

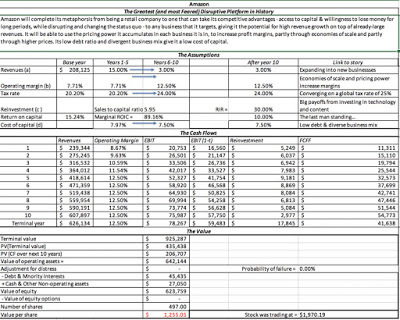

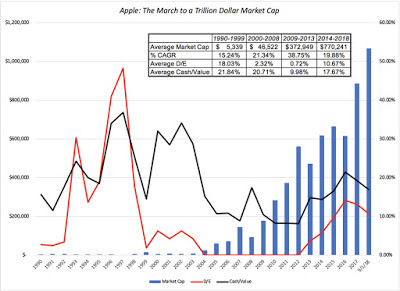

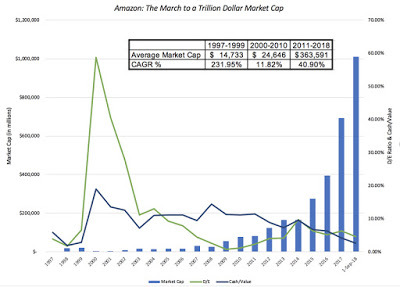

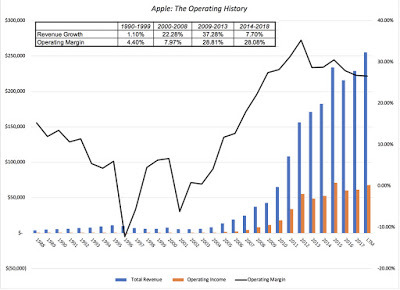

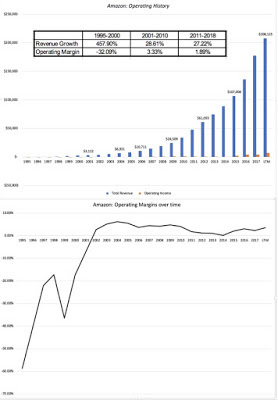

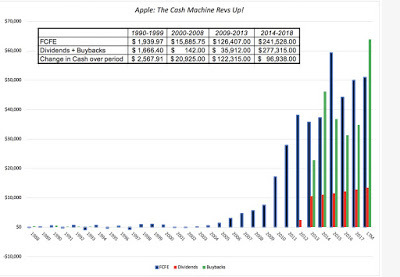

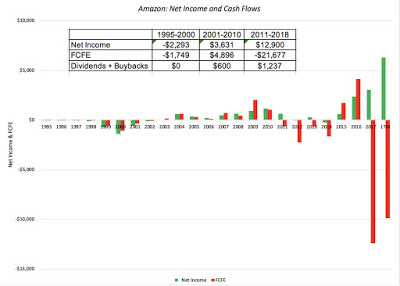

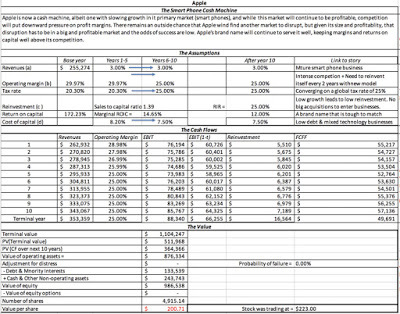

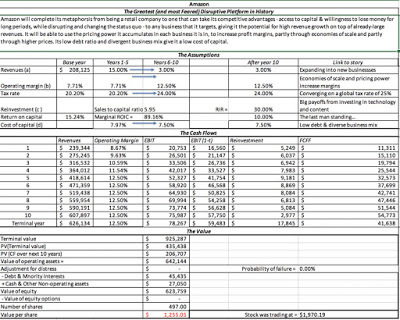

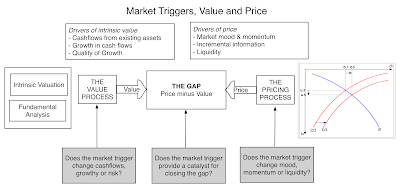

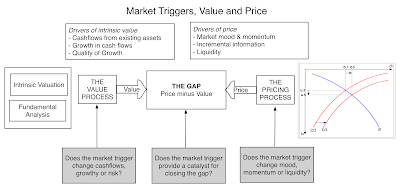

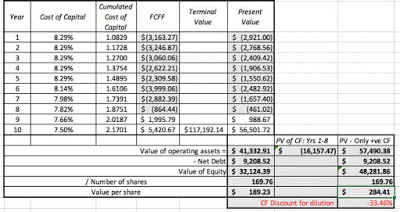

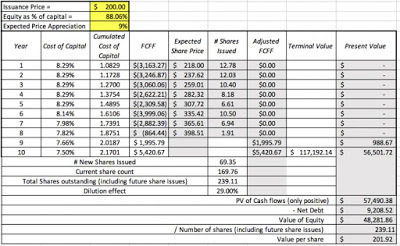

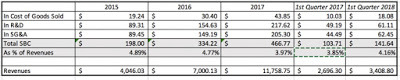

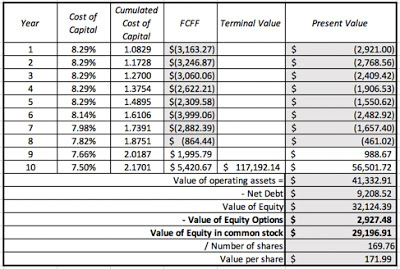

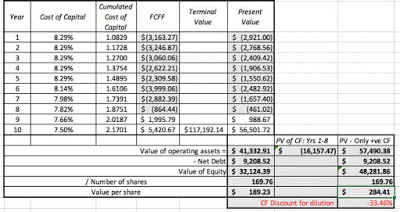

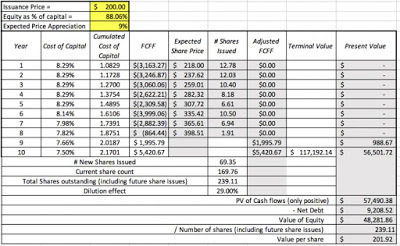

In my last post, I looked at Apple and Amazon, as their market caps exceeded a trillion dollars, tracing the journey that they took over the last two decades to get to that threshold and valuing them given their current standing. While you can check out the stories that I told and the details of my valuation in that post, I valued Apple at $200, about 9% less than the market price, and Amazon at abut $1255, about 35% lower than its market price. I concluded the post with a teaser, promising to come back with my decisions on whether I would sell my existing Apple shareholding and/or sell short on Amazon, after reviewing two loose ends. The first is to lay bare the uncertainties inherent in both valuations, to see if there is something in those uncertainties that I can use to make a better decision. The second is to evaluate whether there are catalysts that will convert the gap that I see between value and price into actual profits.

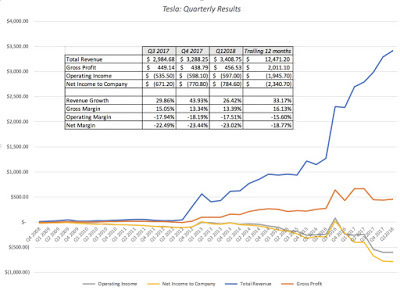

Facing up to Uncertainty