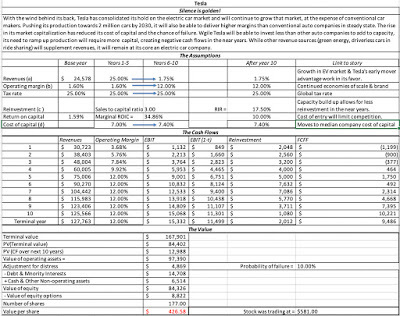

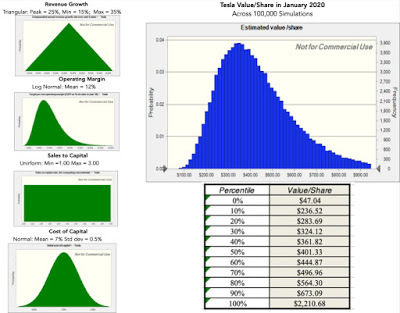

Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 14

March 9, 2020

A Viral Market Meltdown Part II: Clues in the Debris!

Update on 3.9/20: In a sign of how volatile times are, over the weekend, oil prices plummeted to close to $30, the treasury bond rate to less than 0.4% and the market looks set to drop substantially. A work in progress indeed....

I wrote a post on how the Corona Virus was playing out in markets on February 26, two days into the market going into convulsions, and while I tried to make an assessment of the value effect, I also said that this analysis was a work in progress, that I would revisit as we learned more about the virus and its economic consequences. Eleven days later, we still don't have clarity on the health or economic effects of the virus, but we do have substantially more data on what the market reaction has been. In this post, I will begin by doing a quick update on the viral spread across the world, but spend more time on the market damage, looking at where it has been greatest, seeking clues for the future.

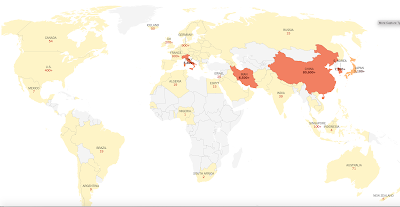

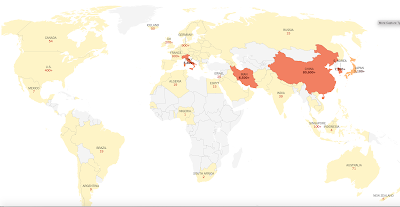

A Virus UpdateIn the last week and a half, the virus has clearly expanded its global footprint, with Italy and South Korea now in the front lines, in terms of exposure, but with the numbers climbing rapidly across the rest of the world, it is clearly now on its way to becoming a global pandemic. NY Times, as of March 6, 2020

NY Times, as of March 6, 2020

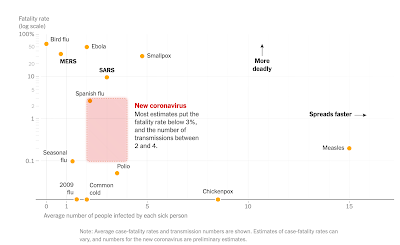

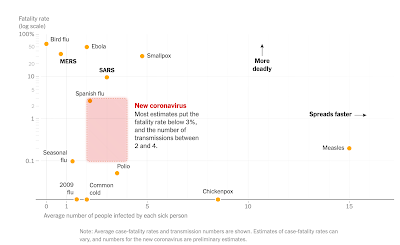

While the word "pandemic" alone is often enough to drive us to panic, it is not the first, nor will it be the last, and it helps to gain perspective to compare it to pandemics in the past, both in terms of contagion and health consequences. This chart from the New York Times reflects what we know about the virus as of February 28, 2020: Note that the large band of uncertainty around the fatality rate related to the virus, reflecting how little we know about its potential consequences and how it measures up against other viruses in terms of contagion. Put simply, this is not just the common flu with side effects, as some have argued, but it is perhaps not the deadly killer that others at the other extreme has painted it as. The X factor that makes this virus potentially more difficult to contain and more likely to have global consequences is globalization, one more argument that populists will undoubtedly use to argue against it. The reality is that travel, especially across borders and continents, is not only easier than ever before but also more affordable, as income levels rise in the developing world. Over the next few weeks, it is likely that we will see the case numbers rise dramatically in countries which have been hitherto exposed only lightly to the virus, the fatality numbers will rise among those affected, and health systems around the world will come under pressure.

Note that the large band of uncertainty around the fatality rate related to the virus, reflecting how little we know about its potential consequences and how it measures up against other viruses in terms of contagion. Put simply, this is not just the common flu with side effects, as some have argued, but it is perhaps not the deadly killer that others at the other extreme has painted it as. The X factor that makes this virus potentially more difficult to contain and more likely to have global consequences is globalization, one more argument that populists will undoubtedly use to argue against it. The reality is that travel, especially across borders and continents, is not only easier than ever before but also more affordable, as income levels rise in the developing world. Over the next few weeks, it is likely that we will see the case numbers rise dramatically in countries which have been hitherto exposed only lightly to the virus, the fatality numbers will rise among those affected, and health systems around the world will come under pressure.

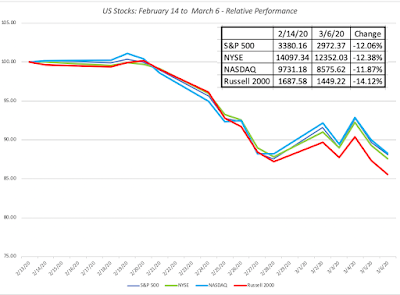

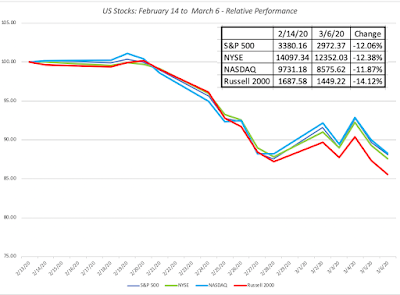

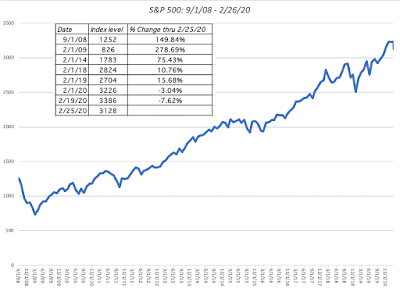

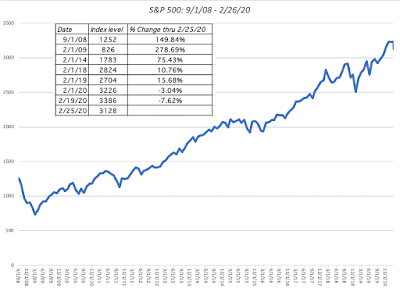

A Market UpdateOver the last three weeks, we have had a glimpse of how quickly market moods can shift. Looking at the major US equity indices, you can see the euphoria that resulted in the market peaking on February 12, 2020, not only faded quickly but has been replaced with panic and desperation: If there is one thing that can be said about markets during this tumultuous period, they were not playing favorites, since all of the indices registered double git drops, with the NASDAQ showing the smallest drop.

If there is one thing that can be said about markets during this tumultuous period, they were not playing favorites, since all of the indices registered double git drops, with the NASDAQ showing the smallest drop.

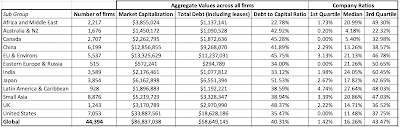

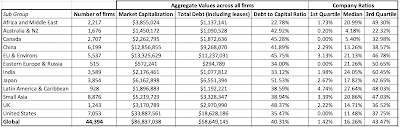

a. Melting Away - Dollar Value LostThe focus on the indices can obscure the staggering decline in market values that occurred in a three-week period and in the table below, I chronicle the loss in market value globally, broken down by region. Download spreadsheetThe first four columns look at total market capitalization and the change in both dollar and percentage terms between February 14, 2020 and March 6, 2020. Globally, equity markets lost $7.3 trillion in value over this three-week period, and it is ironic that China, the starting point for the Corona Virus, is the only part of the world where stocks have collectively seen an increase in market capitalization. That can be explained perhaps by the fact that Chinese stocks had already registered drops in the weeks leading into February 14, and that the rest of the world is playing catch up. The last five columns look at the percentage change in individual stocks to illustrate how widely the pain was felt. In ten of the twelve regions, with China and Africa being the exceptions, less than 25% of stocks went up during the three week period. In most of the markets, the percentage change in overall market capitalization is similar to the percentage change in the median stock, indicating that this is not a decline being caused by a subset of stocks being hit with extreme price movements.

Download spreadsheetThe first four columns look at total market capitalization and the change in both dollar and percentage terms between February 14, 2020 and March 6, 2020. Globally, equity markets lost $7.3 trillion in value over this three-week period, and it is ironic that China, the starting point for the Corona Virus, is the only part of the world where stocks have collectively seen an increase in market capitalization. That can be explained perhaps by the fact that Chinese stocks had already registered drops in the weeks leading into February 14, and that the rest of the world is playing catch up. The last five columns look at the percentage change in individual stocks to illustrate how widely the pain was felt. In ten of the twelve regions, with China and Africa being the exceptions, less than 25% of stocks went up during the three week period. In most of the markets, the percentage change in overall market capitalization is similar to the percentage change in the median stock, indicating that this is not a decline being caused by a subset of stocks being hit with extreme price movements.

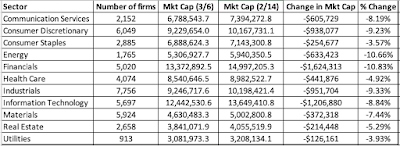

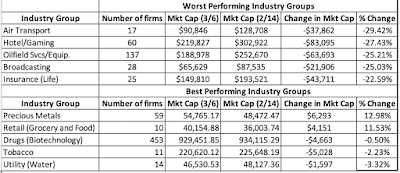

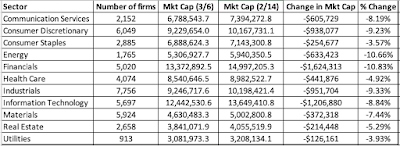

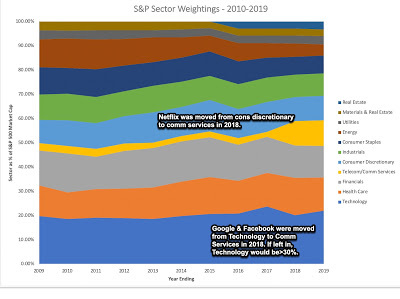

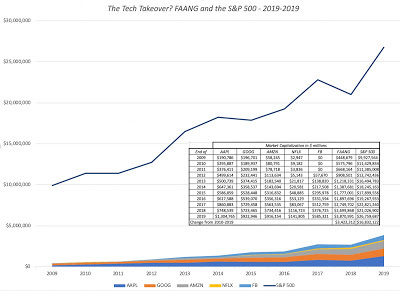

b. The Sector/Industry BreakdownThere is no question that the virus not only has the potential to hurt the global economy, but the hurt will be felt disproportionately by companies in different businesses. To assess how the market has repriced different sectors, I look at the market capitalization lost, in both dollar and percent terms, by sector, for global companies: Download spreadsheetThe biggest losers were energy and financial service companies, and the sectors that performed the best were utilities, health care, real estate and consumer staples. Breaking down the sectors into more detail, I looked at US stocks, by industry, and the following is the list of the five worst and five best performing industries between February 14 and March 6:

Download spreadsheetThe biggest losers were energy and financial service companies, and the sectors that performed the best were utilities, health care, real estate and consumer staples. Breaking down the sectors into more detail, I looked at US stocks, by industry, and the following is the list of the five worst and five best performing industries between February 14 and March 6:

Download spreadsheet

Download spreadsheet

The full list is available for download by clicking here. For anyone who has been following the news stories of airlines scrambling to cancel flights and mollify passengers and hotels dealing with cancellations, it should come as no surprise that aviation and hotel stocks were the worst performing industry groupings, followed by oil, broadcasting and life insurance. The best performing industry grouping also carries no surprises, with precious metal companies benefiting from the rise in gold prices, grocery retailers and tobacco drawing on their strengths as non-discretionary products and biotech companies benefiting from the focus on a solution for the virus.

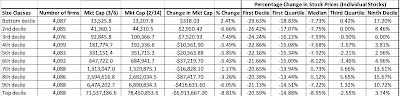

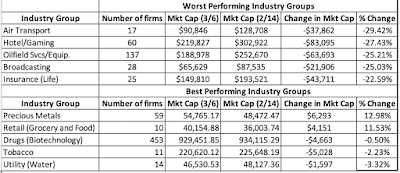

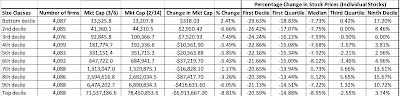

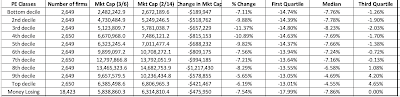

c. Size ClassesThe conventional wisdom, when there is a market crisis, is that investors move their money to safety. While that has clearly happened with money shifting into US treasuries, the question is whether investors are abandoning smaller companies for larger ones, presumably driven by the perception that smaller companies are riskier than larger ones. To answer this question, I looked at all global companies, broken down by market capitalization into ten classes: Download spreadsheetThe results don't line up with expectations, as small companies saw a small increase in overall market capitalization and large cap stocks registered the largest decline. It is worth noting that even among the smallest stocks, the median stock lost 7.73%, suggesting that the increase in value is coming from a small percentage of stocks in the group. (Looking at just US stocks, you get very similar results.)

Download spreadsheetThe results don't line up with expectations, as small companies saw a small increase in overall market capitalization and large cap stocks registered the largest decline. It is worth noting that even among the smallest stocks, the median stock lost 7.73%, suggesting that the increase in value is coming from a small percentage of stocks in the group. (Looking at just US stocks, you get very similar results.)

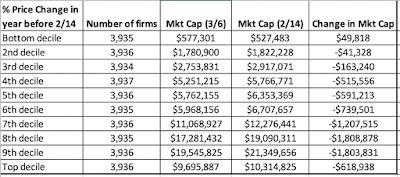

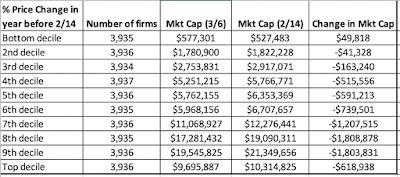

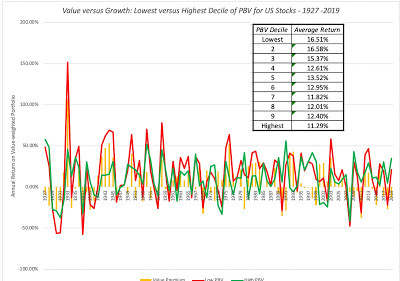

d. Value and Momentum ClassesThe drop in the market has provided some measure of vindication to those who have long been arguing that the market is over priced, but while the fact that the market was priced so richly set it up for a larger fall, breaking down the decline in market cap into classes can provide us some insight into whether the stocks that had gone up the most were the ones that saw the biggest drop off in value between February 14 and March 6. In the table, we break global stocks down into ten classes based upon the price change in the year prior to February 14 and look at the change in market capitalization, by class: Download spreadsheetIn keeping with the story that what goes up the most must come down the most, you find that stocks that had performed the worst in the year leading into February 14 had an increase in market capitalization, though the median stock was still down, within this group. Using another proxy for rich pricing, I also broke stocks down by PE ratio classes from lowest to highest, based upon market capitalization on February 14, 2020, and looked at the change in market value between February 14 and March 6:

Download spreadsheetIn keeping with the story that what goes up the most must come down the most, you find that stocks that had performed the worst in the year leading into February 14 had an increase in market capitalization, though the median stock was still down, within this group. Using another proxy for rich pricing, I also broke stocks down by PE ratio classes from lowest to highest, based upon market capitalization on February 14, 2020, and looked at the change in market value between February 14 and March 6:

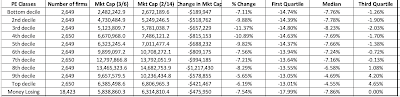

Download spreadsheetHere, the evidence contradicts the market correction hypothesis, since there is no discernible relationship between PE ratios and market value change. In fact, the best performing stocks are in the top two deciles of PE ratios.

Download spreadsheetHere, the evidence contradicts the market correction hypothesis, since there is no discernible relationship between PE ratios and market value change. In fact, the best performing stocks are in the top two deciles of PE ratios.

e. The Rest of the StoryOne of the perils of getting focused on equity markets is that you can miss all of the action in other markets, and the changes in those markets can not only help augment the story that equities are telling us, but they can yield insight into other facets.

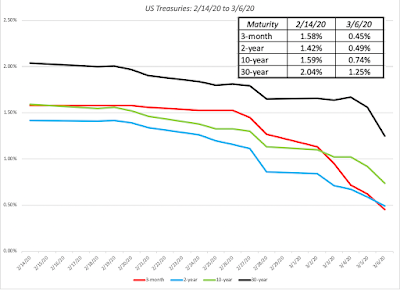

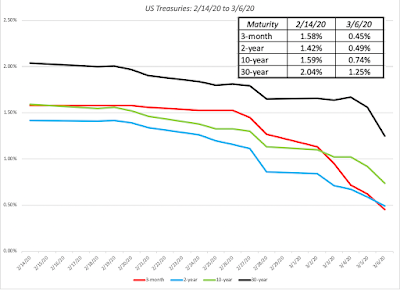

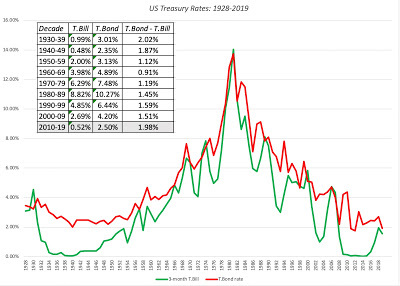

I. US Treasury ratesIf the drop in stock prices over the last three weeks took your breath away, the shifts in the treasury market were even larger and more unsettling:

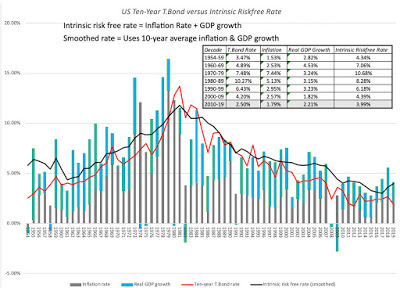

The 10-year US T.Bond dropped below 1% for the first time in history on March 3 and continued trending down to settle at 0.74% on March 6. In tandem, the other treasuries also dropped, bring the US dollar risk free rates closer to the Euro and Yen risk free rates. While some of the decline in rates can be attributed to a flight to safety, there is also a much depressing read of the same drop. To the extent that long term risk free rates are proxies for nominal economic growth, the treasury bond market seems to be signaling not just a shock to near-term economic growth from the Corona virus, but a long term decline. We will get a better sense of what the bond market is expecting, once equities settle in, but if the 10-year rate stays below 1%, it is not a good sign for the economy.

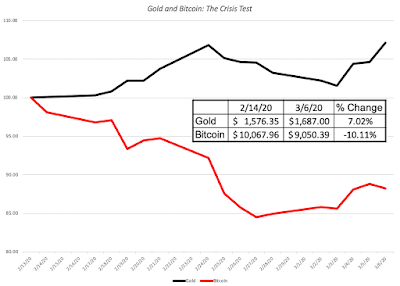

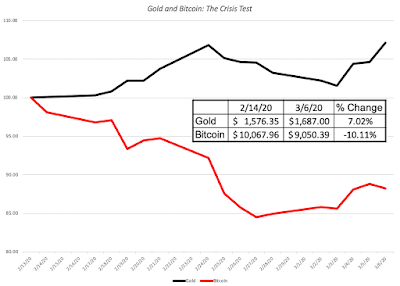

II. Gold and Bitcoin (Millennial Gold)The other asset class that always attracts attention and money during crisis is gold, and for good measure, I will also look at Bitcoin, which some have suggested is the millennial equivalent of gold:

It is perhaps a little unfair to draw a conclusion from just contest, but the fact that Bitcoin has behaved more like stocks than like gold suggests that millennials who have held on to it, as their asset of refuge, may want to rethink their positions.

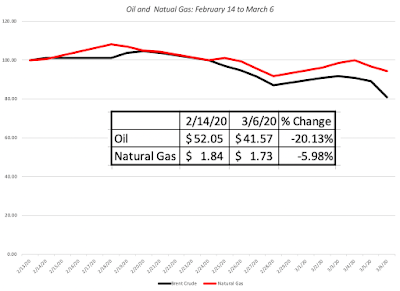

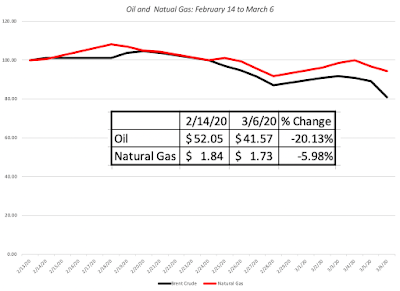

3. Oil and CommoditiesThe final piece of the market puzzle comes from the commodity markets, with oil as its front runner. In the three weeks which have taken equity markets on a ride and caused US treasuries to hit new lows, oil prices have been on a journey of their own:

Not only have oil prices dropped 20% during the three weeks, they are plumbing depths seldom seen in this century. The decline in oil prices not only reflect an expectation of global economic slowdown but also how dependent oil and other commodity prices have become on China's continued growth and prosperity. The smaller decline in natural gas prices, much less tied to the Chinese market, reinforces this argument.

Revisiting the Viral ValueWith this long lead in, you might have lost interest already, but if you are still reading, it is time to turn to specifics and look at how what I have learned in the last 12 days has or has not changed my views on the market.

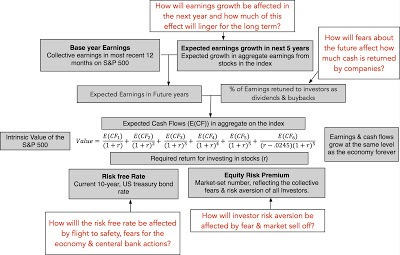

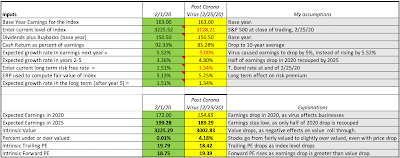

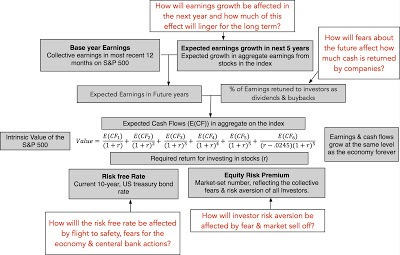

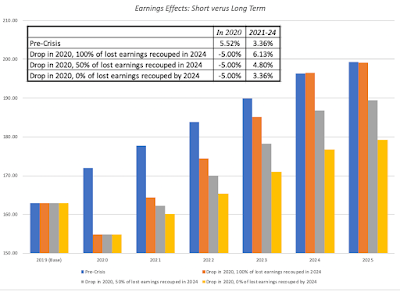

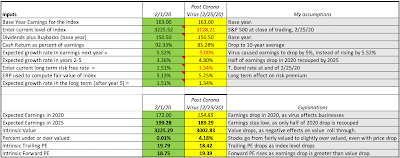

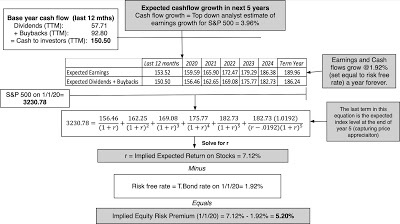

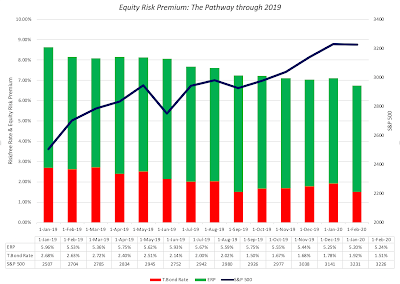

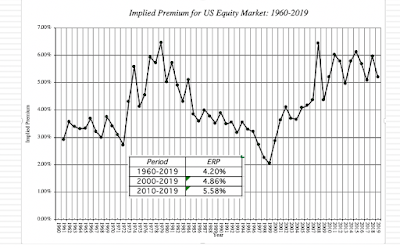

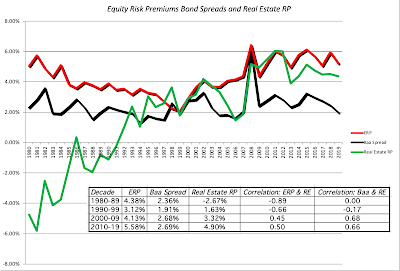

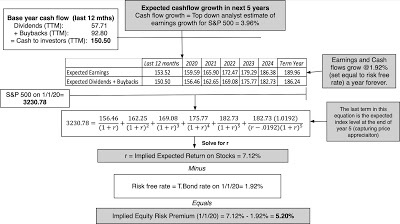

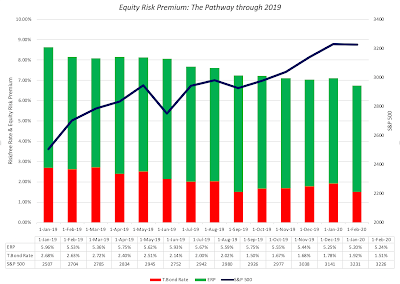

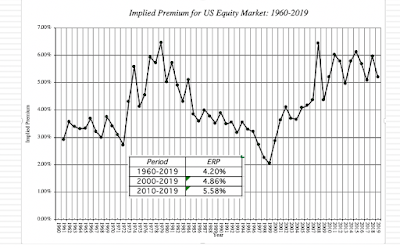

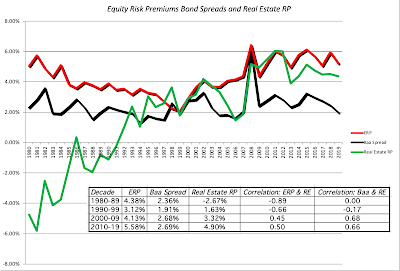

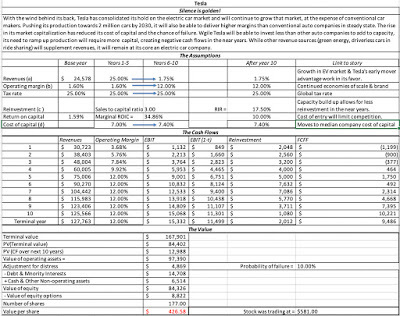

Recapping the DriversVery quickly recapping what I argued were the drivers of the value of stocks, I argued that there were three components to value:Earnings Growth: In my 2/26/20 valuation of the S&P 500 index, I argued that the corona virus is now almost certain to cause earnings effects for companies, and estimated the drop to be 5% (a significant revision down from the 5.52% growth that had been predicted in the index. In the last few days, analysts have started adjusting earnings expectations down for companies, and this snapshot from Zacks today captures some of the adjustment: Note that the expected earnings on the index for 2021 has dropped from 172 for next year, two weeks ago, to 163 this week, matching the earnings generated in 2019. That is still better than the 5% drop that I was projecting, but my guess is that I am still undershooting the actual earnings decline and I have increased the expected earnings drop in 2020 to 10%. To complete the assessment of growth, I also need to estimate how much of the earnings drop in 2020 will be recouped in future years. In my valuation on February 26, I had estimated that half of the earnings drop in 2020 would be recouped but that the rest would be lost for the long term. I will continue to hold on to that assumption In addition, since my long term growth rate converges on the US T.Bond rate, the precipitous drop in that rate has lowered my growth rate in perpetuity to 0.74% (to match the T. Bond rate).Cash flow Payout: The second component of value is the cash that companies can return, in dividends and buybacks. I assumed that companies, driven by uncertainty, would scale the percent of the earnings that they return to stockholders from the 92.33% that they were returning prior to the crisis to 85%, more in line with the ten-year average. In the days since, there have been no announcements of dividend cuts or scaling back of already announced buybacks, but I would not be surprised to see that change in the next few weeks. Discount Rate Dynamics: The discount rate dynamics are the trickiest. On the one hand, the lower T.Bond rate will create a lower base from which to build up, but the increase in volatility (actual and expected, as captured in the rise in the VIX over the last three weeks) has pushed equity risk premiums up. I will scale up my ERP to 5.69% to match my implied premium at the start of March 2020.With that combination of assumptions (10% drop in earnings, 50% recoupment between 2022-25, 85% cash return and a 5.69% premium), the value that I derive fo the index Is 2889, and much of the reason for the drop from the value that I estimated on February 26, 2020, can be attributed to the the lower growth rate that I am estimating in the near term and in the long term.

Note that the expected earnings on the index for 2021 has dropped from 172 for next year, two weeks ago, to 163 this week, matching the earnings generated in 2019. That is still better than the 5% drop that I was projecting, but my guess is that I am still undershooting the actual earnings decline and I have increased the expected earnings drop in 2020 to 10%. To complete the assessment of growth, I also need to estimate how much of the earnings drop in 2020 will be recouped in future years. In my valuation on February 26, I had estimated that half of the earnings drop in 2020 would be recouped but that the rest would be lost for the long term. I will continue to hold on to that assumption In addition, since my long term growth rate converges on the US T.Bond rate, the precipitous drop in that rate has lowered my growth rate in perpetuity to 0.74% (to match the T. Bond rate).Cash flow Payout: The second component of value is the cash that companies can return, in dividends and buybacks. I assumed that companies, driven by uncertainty, would scale the percent of the earnings that they return to stockholders from the 92.33% that they were returning prior to the crisis to 85%, more in line with the ten-year average. In the days since, there have been no announcements of dividend cuts or scaling back of already announced buybacks, but I would not be surprised to see that change in the next few weeks. Discount Rate Dynamics: The discount rate dynamics are the trickiest. On the one hand, the lower T.Bond rate will create a lower base from which to build up, but the increase in volatility (actual and expected, as captured in the rise in the VIX over the last three weeks) has pushed equity risk premiums up. I will scale up my ERP to 5.69% to match my implied premium at the start of March 2020.With that combination of assumptions (10% drop in earnings, 50% recoupment between 2022-25, 85% cash return and a 5.69% premium), the value that I derive fo the index Is 2889, and much of the reason for the drop from the value that I estimated on February 26, 2020, can be attributed to the the lower growth rate that I am estimating in the near term and in the long term.

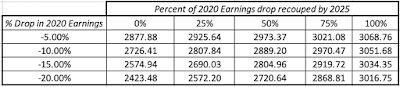

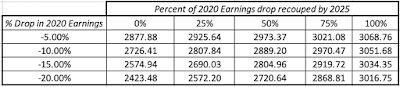

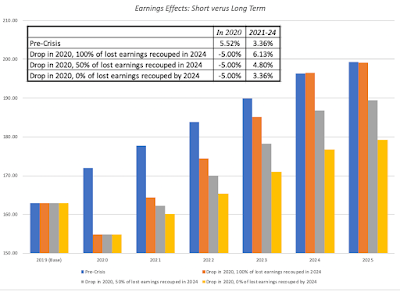

Value DynamicsIn the days to come, there will be more information that comes out about not only how the virus is spreading across the globe but also on its consequences for businesses and economies. To provide a measure of how this will affect stock values, I computed the value of the S&P 500 (which stood at 2972.37 on March 6, 2020) as a function of what I believe are the two big uncertainties; the effect that the virus will have on earnings in 2020 and how much it will affect long term earnings growth:

Download valuation spreadsheetNote that the big concern, if you are an investor focused on value, is not how much the Corona virus will affect earnings this year, but how much of that earnings drop is permanent. If you are in the camp that believes that there will be an earning drop, but that it will be fully recouped, stocks look cheap even if earnings drop by 20% in 2020. Conversely, if you believe that this earnings drop is likely to be permanent, with none of the drop being recouped, the value drop will be more closely linked to the earnings drop and suggests that there is more pain ahead for the market.

Download valuation spreadsheetNote that the big concern, if you are an investor focused on value, is not how much the Corona virus will affect earnings this year, but how much of that earnings drop is permanent. If you are in the camp that believes that there will be an earning drop, but that it will be fully recouped, stocks look cheap even if earnings drop by 20% in 2020. Conversely, if you believe that this earnings drop is likely to be permanent, with none of the drop being recouped, the value drop will be more closely linked to the earnings drop and suggests that there is more pain ahead for the market.

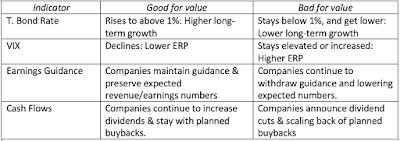

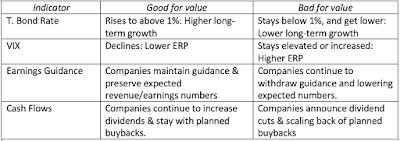

What to watch for..Needless to say, there will be plenty of distractions in the coming weeks, but my suggestion is that you stay honed in on the value determinants, screening news stories for consequences for these determinants. In particular, I plan to watch the following developments: I know that my view that T.Bond rates staying low and getting lower is not a positive but a negative for stocks puts me in the opposite camp from those who believe that the Fed will be the savior. When rates are as low as they are, central banks are more helpless bystanders than powerful trend setters, and the message about future growth that is imputed in low rates more than drowns any short term positive effects.

I know that my view that T.Bond rates staying low and getting lower is not a positive but a negative for stocks puts me in the opposite camp from those who believe that the Fed will be the savior. When rates are as low as they are, central banks are more helpless bystanders than powerful trend setters, and the message about future growth that is imputed in low rates more than drowns any short term positive effects.

The Big Things in LifeAs I write this analysis of how the virus can affect stock market values and portfolio returns, I am aware that there is a human toll that it is taking that makes any market effects seem trivial. If I were given the choice, I would trade a large market drop for a small loss of lives and a quick passing of the virus. At times like these, I am reminded again of the fragility of life and the importance of good health and family. Be well, Godspeed and please wash your hands!

YouTube Video

Datasets

Market Damage, by region, sector, industry, size and momentum

Spreadsheets

An Updated S&P Valuation Spreadsheet: March 6, 2020

I wrote a post on how the Corona Virus was playing out in markets on February 26, two days into the market going into convulsions, and while I tried to make an assessment of the value effect, I also said that this analysis was a work in progress, that I would revisit as we learned more about the virus and its economic consequences. Eleven days later, we still don't have clarity on the health or economic effects of the virus, but we do have substantially more data on what the market reaction has been. In this post, I will begin by doing a quick update on the viral spread across the world, but spend more time on the market damage, looking at where it has been greatest, seeking clues for the future.

A Virus UpdateIn the last week and a half, the virus has clearly expanded its global footprint, with Italy and South Korea now in the front lines, in terms of exposure, but with the numbers climbing rapidly across the rest of the world, it is clearly now on its way to becoming a global pandemic.

NY Times, as of March 6, 2020

NY Times, as of March 6, 2020While the word "pandemic" alone is often enough to drive us to panic, it is not the first, nor will it be the last, and it helps to gain perspective to compare it to pandemics in the past, both in terms of contagion and health consequences. This chart from the New York Times reflects what we know about the virus as of February 28, 2020:

Note that the large band of uncertainty around the fatality rate related to the virus, reflecting how little we know about its potential consequences and how it measures up against other viruses in terms of contagion. Put simply, this is not just the common flu with side effects, as some have argued, but it is perhaps not the deadly killer that others at the other extreme has painted it as. The X factor that makes this virus potentially more difficult to contain and more likely to have global consequences is globalization, one more argument that populists will undoubtedly use to argue against it. The reality is that travel, especially across borders and continents, is not only easier than ever before but also more affordable, as income levels rise in the developing world. Over the next few weeks, it is likely that we will see the case numbers rise dramatically in countries which have been hitherto exposed only lightly to the virus, the fatality numbers will rise among those affected, and health systems around the world will come under pressure.

Note that the large band of uncertainty around the fatality rate related to the virus, reflecting how little we know about its potential consequences and how it measures up against other viruses in terms of contagion. Put simply, this is not just the common flu with side effects, as some have argued, but it is perhaps not the deadly killer that others at the other extreme has painted it as. The X factor that makes this virus potentially more difficult to contain and more likely to have global consequences is globalization, one more argument that populists will undoubtedly use to argue against it. The reality is that travel, especially across borders and continents, is not only easier than ever before but also more affordable, as income levels rise in the developing world. Over the next few weeks, it is likely that we will see the case numbers rise dramatically in countries which have been hitherto exposed only lightly to the virus, the fatality numbers will rise among those affected, and health systems around the world will come under pressure. A Market UpdateOver the last three weeks, we have had a glimpse of how quickly market moods can shift. Looking at the major US equity indices, you can see the euphoria that resulted in the market peaking on February 12, 2020, not only faded quickly but has been replaced with panic and desperation:

If there is one thing that can be said about markets during this tumultuous period, they were not playing favorites, since all of the indices registered double git drops, with the NASDAQ showing the smallest drop.

If there is one thing that can be said about markets during this tumultuous period, they were not playing favorites, since all of the indices registered double git drops, with the NASDAQ showing the smallest drop.a. Melting Away - Dollar Value LostThe focus on the indices can obscure the staggering decline in market values that occurred in a three-week period and in the table below, I chronicle the loss in market value globally, broken down by region.

Download spreadsheetThe first four columns look at total market capitalization and the change in both dollar and percentage terms between February 14, 2020 and March 6, 2020. Globally, equity markets lost $7.3 trillion in value over this three-week period, and it is ironic that China, the starting point for the Corona Virus, is the only part of the world where stocks have collectively seen an increase in market capitalization. That can be explained perhaps by the fact that Chinese stocks had already registered drops in the weeks leading into February 14, and that the rest of the world is playing catch up. The last five columns look at the percentage change in individual stocks to illustrate how widely the pain was felt. In ten of the twelve regions, with China and Africa being the exceptions, less than 25% of stocks went up during the three week period. In most of the markets, the percentage change in overall market capitalization is similar to the percentage change in the median stock, indicating that this is not a decline being caused by a subset of stocks being hit with extreme price movements.

Download spreadsheetThe first four columns look at total market capitalization and the change in both dollar and percentage terms between February 14, 2020 and March 6, 2020. Globally, equity markets lost $7.3 trillion in value over this three-week period, and it is ironic that China, the starting point for the Corona Virus, is the only part of the world where stocks have collectively seen an increase in market capitalization. That can be explained perhaps by the fact that Chinese stocks had already registered drops in the weeks leading into February 14, and that the rest of the world is playing catch up. The last five columns look at the percentage change in individual stocks to illustrate how widely the pain was felt. In ten of the twelve regions, with China and Africa being the exceptions, less than 25% of stocks went up during the three week period. In most of the markets, the percentage change in overall market capitalization is similar to the percentage change in the median stock, indicating that this is not a decline being caused by a subset of stocks being hit with extreme price movements.b. The Sector/Industry BreakdownThere is no question that the virus not only has the potential to hurt the global economy, but the hurt will be felt disproportionately by companies in different businesses. To assess how the market has repriced different sectors, I look at the market capitalization lost, in both dollar and percent terms, by sector, for global companies:

Download spreadsheetThe biggest losers were energy and financial service companies, and the sectors that performed the best were utilities, health care, real estate and consumer staples. Breaking down the sectors into more detail, I looked at US stocks, by industry, and the following is the list of the five worst and five best performing industries between February 14 and March 6:

Download spreadsheetThe biggest losers were energy and financial service companies, and the sectors that performed the best were utilities, health care, real estate and consumer staples. Breaking down the sectors into more detail, I looked at US stocks, by industry, and the following is the list of the five worst and five best performing industries between February 14 and March 6:

Download spreadsheet

Download spreadsheetThe full list is available for download by clicking here. For anyone who has been following the news stories of airlines scrambling to cancel flights and mollify passengers and hotels dealing with cancellations, it should come as no surprise that aviation and hotel stocks were the worst performing industry groupings, followed by oil, broadcasting and life insurance. The best performing industry grouping also carries no surprises, with precious metal companies benefiting from the rise in gold prices, grocery retailers and tobacco drawing on their strengths as non-discretionary products and biotech companies benefiting from the focus on a solution for the virus.

c. Size ClassesThe conventional wisdom, when there is a market crisis, is that investors move their money to safety. While that has clearly happened with money shifting into US treasuries, the question is whether investors are abandoning smaller companies for larger ones, presumably driven by the perception that smaller companies are riskier than larger ones. To answer this question, I looked at all global companies, broken down by market capitalization into ten classes:

Download spreadsheetThe results don't line up with expectations, as small companies saw a small increase in overall market capitalization and large cap stocks registered the largest decline. It is worth noting that even among the smallest stocks, the median stock lost 7.73%, suggesting that the increase in value is coming from a small percentage of stocks in the group. (Looking at just US stocks, you get very similar results.)

Download spreadsheetThe results don't line up with expectations, as small companies saw a small increase in overall market capitalization and large cap stocks registered the largest decline. It is worth noting that even among the smallest stocks, the median stock lost 7.73%, suggesting that the increase in value is coming from a small percentage of stocks in the group. (Looking at just US stocks, you get very similar results.) d. Value and Momentum ClassesThe drop in the market has provided some measure of vindication to those who have long been arguing that the market is over priced, but while the fact that the market was priced so richly set it up for a larger fall, breaking down the decline in market cap into classes can provide us some insight into whether the stocks that had gone up the most were the ones that saw the biggest drop off in value between February 14 and March 6. In the table, we break global stocks down into ten classes based upon the price change in the year prior to February 14 and look at the change in market capitalization, by class:

Download spreadsheetIn keeping with the story that what goes up the most must come down the most, you find that stocks that had performed the worst in the year leading into February 14 had an increase in market capitalization, though the median stock was still down, within this group. Using another proxy for rich pricing, I also broke stocks down by PE ratio classes from lowest to highest, based upon market capitalization on February 14, 2020, and looked at the change in market value between February 14 and March 6:

Download spreadsheetIn keeping with the story that what goes up the most must come down the most, you find that stocks that had performed the worst in the year leading into February 14 had an increase in market capitalization, though the median stock was still down, within this group. Using another proxy for rich pricing, I also broke stocks down by PE ratio classes from lowest to highest, based upon market capitalization on February 14, 2020, and looked at the change in market value between February 14 and March 6:

Download spreadsheetHere, the evidence contradicts the market correction hypothesis, since there is no discernible relationship between PE ratios and market value change. In fact, the best performing stocks are in the top two deciles of PE ratios.

Download spreadsheetHere, the evidence contradicts the market correction hypothesis, since there is no discernible relationship between PE ratios and market value change. In fact, the best performing stocks are in the top two deciles of PE ratios.e. The Rest of the StoryOne of the perils of getting focused on equity markets is that you can miss all of the action in other markets, and the changes in those markets can not only help augment the story that equities are telling us, but they can yield insight into other facets.

I. US Treasury ratesIf the drop in stock prices over the last three weeks took your breath away, the shifts in the treasury market were even larger and more unsettling:

The 10-year US T.Bond dropped below 1% for the first time in history on March 3 and continued trending down to settle at 0.74% on March 6. In tandem, the other treasuries also dropped, bring the US dollar risk free rates closer to the Euro and Yen risk free rates. While some of the decline in rates can be attributed to a flight to safety, there is also a much depressing read of the same drop. To the extent that long term risk free rates are proxies for nominal economic growth, the treasury bond market seems to be signaling not just a shock to near-term economic growth from the Corona virus, but a long term decline. We will get a better sense of what the bond market is expecting, once equities settle in, but if the 10-year rate stays below 1%, it is not a good sign for the economy.

II. Gold and Bitcoin (Millennial Gold)The other asset class that always attracts attention and money during crisis is gold, and for good measure, I will also look at Bitcoin, which some have suggested is the millennial equivalent of gold:

It is perhaps a little unfair to draw a conclusion from just contest, but the fact that Bitcoin has behaved more like stocks than like gold suggests that millennials who have held on to it, as their asset of refuge, may want to rethink their positions.

3. Oil and CommoditiesThe final piece of the market puzzle comes from the commodity markets, with oil as its front runner. In the three weeks which have taken equity markets on a ride and caused US treasuries to hit new lows, oil prices have been on a journey of their own:

Not only have oil prices dropped 20% during the three weeks, they are plumbing depths seldom seen in this century. The decline in oil prices not only reflect an expectation of global economic slowdown but also how dependent oil and other commodity prices have become on China's continued growth and prosperity. The smaller decline in natural gas prices, much less tied to the Chinese market, reinforces this argument.

Revisiting the Viral ValueWith this long lead in, you might have lost interest already, but if you are still reading, it is time to turn to specifics and look at how what I have learned in the last 12 days has or has not changed my views on the market.

Recapping the DriversVery quickly recapping what I argued were the drivers of the value of stocks, I argued that there were three components to value:Earnings Growth: In my 2/26/20 valuation of the S&P 500 index, I argued that the corona virus is now almost certain to cause earnings effects for companies, and estimated the drop to be 5% (a significant revision down from the 5.52% growth that had been predicted in the index. In the last few days, analysts have started adjusting earnings expectations down for companies, and this snapshot from Zacks today captures some of the adjustment:

Note that the expected earnings on the index for 2021 has dropped from 172 for next year, two weeks ago, to 163 this week, matching the earnings generated in 2019. That is still better than the 5% drop that I was projecting, but my guess is that I am still undershooting the actual earnings decline and I have increased the expected earnings drop in 2020 to 10%. To complete the assessment of growth, I also need to estimate how much of the earnings drop in 2020 will be recouped in future years. In my valuation on February 26, I had estimated that half of the earnings drop in 2020 would be recouped but that the rest would be lost for the long term. I will continue to hold on to that assumption In addition, since my long term growth rate converges on the US T.Bond rate, the precipitous drop in that rate has lowered my growth rate in perpetuity to 0.74% (to match the T. Bond rate).Cash flow Payout: The second component of value is the cash that companies can return, in dividends and buybacks. I assumed that companies, driven by uncertainty, would scale the percent of the earnings that they return to stockholders from the 92.33% that they were returning prior to the crisis to 85%, more in line with the ten-year average. In the days since, there have been no announcements of dividend cuts or scaling back of already announced buybacks, but I would not be surprised to see that change in the next few weeks. Discount Rate Dynamics: The discount rate dynamics are the trickiest. On the one hand, the lower T.Bond rate will create a lower base from which to build up, but the increase in volatility (actual and expected, as captured in the rise in the VIX over the last three weeks) has pushed equity risk premiums up. I will scale up my ERP to 5.69% to match my implied premium at the start of March 2020.With that combination of assumptions (10% drop in earnings, 50% recoupment between 2022-25, 85% cash return and a 5.69% premium), the value that I derive fo the index Is 2889, and much of the reason for the drop from the value that I estimated on February 26, 2020, can be attributed to the the lower growth rate that I am estimating in the near term and in the long term.

Note that the expected earnings on the index for 2021 has dropped from 172 for next year, two weeks ago, to 163 this week, matching the earnings generated in 2019. That is still better than the 5% drop that I was projecting, but my guess is that I am still undershooting the actual earnings decline and I have increased the expected earnings drop in 2020 to 10%. To complete the assessment of growth, I also need to estimate how much of the earnings drop in 2020 will be recouped in future years. In my valuation on February 26, I had estimated that half of the earnings drop in 2020 would be recouped but that the rest would be lost for the long term. I will continue to hold on to that assumption In addition, since my long term growth rate converges on the US T.Bond rate, the precipitous drop in that rate has lowered my growth rate in perpetuity to 0.74% (to match the T. Bond rate).Cash flow Payout: The second component of value is the cash that companies can return, in dividends and buybacks. I assumed that companies, driven by uncertainty, would scale the percent of the earnings that they return to stockholders from the 92.33% that they were returning prior to the crisis to 85%, more in line with the ten-year average. In the days since, there have been no announcements of dividend cuts or scaling back of already announced buybacks, but I would not be surprised to see that change in the next few weeks. Discount Rate Dynamics: The discount rate dynamics are the trickiest. On the one hand, the lower T.Bond rate will create a lower base from which to build up, but the increase in volatility (actual and expected, as captured in the rise in the VIX over the last three weeks) has pushed equity risk premiums up. I will scale up my ERP to 5.69% to match my implied premium at the start of March 2020.With that combination of assumptions (10% drop in earnings, 50% recoupment between 2022-25, 85% cash return and a 5.69% premium), the value that I derive fo the index Is 2889, and much of the reason for the drop from the value that I estimated on February 26, 2020, can be attributed to the the lower growth rate that I am estimating in the near term and in the long term.

Value DynamicsIn the days to come, there will be more information that comes out about not only how the virus is spreading across the globe but also on its consequences for businesses and economies. To provide a measure of how this will affect stock values, I computed the value of the S&P 500 (which stood at 2972.37 on March 6, 2020) as a function of what I believe are the two big uncertainties; the effect that the virus will have on earnings in 2020 and how much it will affect long term earnings growth:

Download valuation spreadsheetNote that the big concern, if you are an investor focused on value, is not how much the Corona virus will affect earnings this year, but how much of that earnings drop is permanent. If you are in the camp that believes that there will be an earning drop, but that it will be fully recouped, stocks look cheap even if earnings drop by 20% in 2020. Conversely, if you believe that this earnings drop is likely to be permanent, with none of the drop being recouped, the value drop will be more closely linked to the earnings drop and suggests that there is more pain ahead for the market.

Download valuation spreadsheetNote that the big concern, if you are an investor focused on value, is not how much the Corona virus will affect earnings this year, but how much of that earnings drop is permanent. If you are in the camp that believes that there will be an earning drop, but that it will be fully recouped, stocks look cheap even if earnings drop by 20% in 2020. Conversely, if you believe that this earnings drop is likely to be permanent, with none of the drop being recouped, the value drop will be more closely linked to the earnings drop and suggests that there is more pain ahead for the market.

What to watch for..Needless to say, there will be plenty of distractions in the coming weeks, but my suggestion is that you stay honed in on the value determinants, screening news stories for consequences for these determinants. In particular, I plan to watch the following developments:

I know that my view that T.Bond rates staying low and getting lower is not a positive but a negative for stocks puts me in the opposite camp from those who believe that the Fed will be the savior. When rates are as low as they are, central banks are more helpless bystanders than powerful trend setters, and the message about future growth that is imputed in low rates more than drowns any short term positive effects.

I know that my view that T.Bond rates staying low and getting lower is not a positive but a negative for stocks puts me in the opposite camp from those who believe that the Fed will be the savior. When rates are as low as they are, central banks are more helpless bystanders than powerful trend setters, and the message about future growth that is imputed in low rates more than drowns any short term positive effects. The Big Things in LifeAs I write this analysis of how the virus can affect stock market values and portfolio returns, I am aware that there is a human toll that it is taking that makes any market effects seem trivial. If I were given the choice, I would trade a large market drop for a small loss of lives and a quick passing of the virus. At times like these, I am reminded again of the fragility of life and the importance of good health and family. Be well, Godspeed and please wash your hands!

YouTube Video

Datasets

Market Damage, by region, sector, industry, size and momentum

Spreadsheets

An Updated S&P Valuation Spreadsheet: March 6, 2020

Published on March 09, 2020 05:22

February 27, 2020

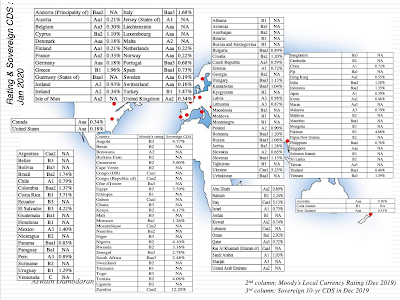

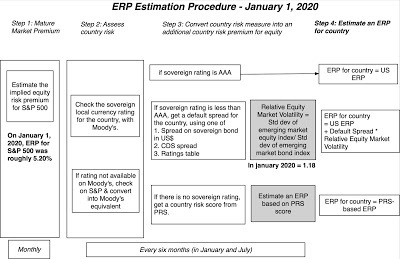

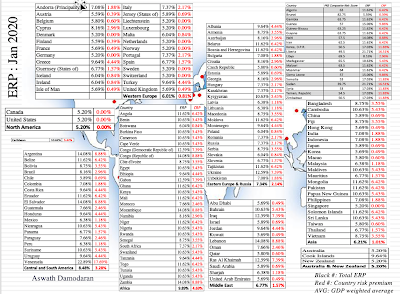

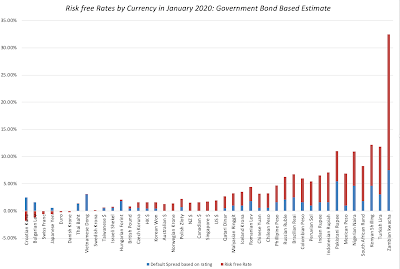

Data Update 5: Relative Risk and Hurdle Rates

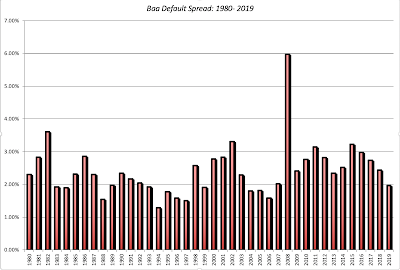

In my last four posts, I focused on the macro variables that we draw on, in both corporate finance and valuation, to estimate required returns or hurdle rates. In data post 3, I looked at how the prices of risk in both the bond market (default spreads) and the equity market (equity risk premiums) dropped in 2019, in the US. In data post 4, I extended the discussion to cover country and currency risk. In this one, I will bring in the micro variables that cause differences in risk across firms, and how to convert them into risk measure.

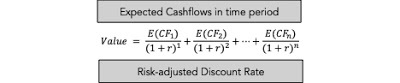

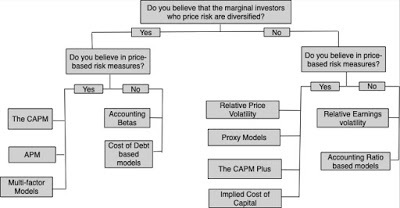

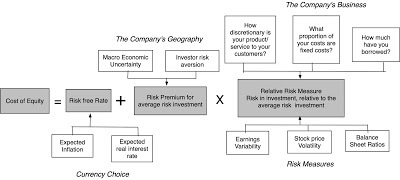

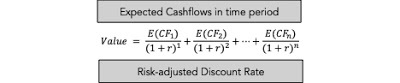

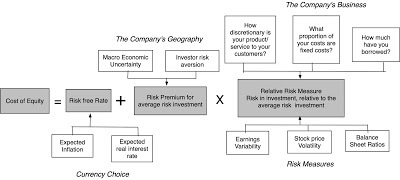

Relative Risk MeasuresTo get from the macro risk measures to company-level hurdle rates, you need to make judgments on relative risk. Put simply, if you buy into the proposition, like I do, that some companies/investments are riskier than others, you need a measure of relative risk that captures this variation. It is in this context that I think of betas, a loaded concept that carries with it the baggage of modern portfolio theory and efficient markets. If you add to this the standard approach to estimating betas, built on looking at past prices and running regressions against market indices, you have the makings of a perfect storm, designed to drive value investors to apoplexy. I have no desire to re-litigate these arguments, partly because those for and opposed to betas are set in their ways, but let me suggest some compromise propositions. Relative Risk Proposition 1 : You do not need to believe in betas to do financial analysis and valuation. While there are many who seem to tie discounted cash flow valuations to the use of beta or betas, there is nothing inherently in a DCF that requires that you make this leap:

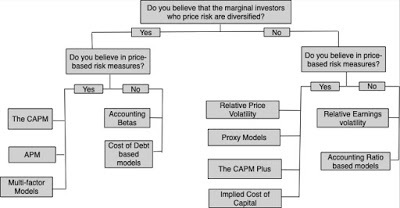

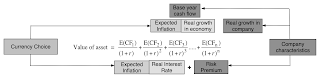

While the discount rate in a DCF is a risk-adjusted number, the approach is agnostic about how you measure risk and adjust discount rates for that risk.Relative Risk Proposition 2: If you don't like to or want to measure relative risk with betas, you can come up with alternate measures that better reflect your view of how risk should be measured. While I do use beta as my proxy for risk, I do so with open eyes, recognizing its many limitations as a risk measure, and I have been always willing to consider competing risk measures. In fact, I have presented alternate measures of risk, drawing on the two building blocks of betas that draw the most pushback. The first is the assumption that marginal investors are diversified, and that the only risk that needs to be measured is the risk that cannot be diversified away. The second is its use of prices (stock and market) to estimate risk, seemingly contradicting intrinsic value's basic precept that market prices are not trustworthy. Since a picture is worth a thousand words, here a few alternative risk measures to consider, if you don't trust betas; Put simply, if your primary problem with betas is the assumption that marginal investors are diversified, there are total risk measures that are built around measuring the total risk in a company or investment, by looking at either the standard deviation or adding premiums (small cap, company-specific risk) to the traditional risk and return model. If your concern is that past prices are being used to estimate betas, you can switch to using accounting earnings and computing risk measures either from the perspective of diversified investors (accounting beta) or undiversified ones (earnings variability).Relative Risk Proposition 3: The margin of safety is not a competitor to any of the risk measures above, since it is a post-value adjustment for risk.Rather than repeat what I said in a much longer post that I had on the topic, let me summarize the points that I made there. When value investors talk about protecting themselves from risk by using a margin of safety, they are talking about building a buffer between value and price, but to use the margin of safety, you need to value a stock first. To get that value, you need a risk measure, and that brings us back full circle to how you adjust for risk, when valuing companies.

Put simply, if your primary problem with betas is the assumption that marginal investors are diversified, there are total risk measures that are built around measuring the total risk in a company or investment, by looking at either the standard deviation or adding premiums (small cap, company-specific risk) to the traditional risk and return model. If your concern is that past prices are being used to estimate betas, you can switch to using accounting earnings and computing risk measures either from the perspective of diversified investors (accounting beta) or undiversified ones (earnings variability).Relative Risk Proposition 3: The margin of safety is not a competitor to any of the risk measures above, since it is a post-value adjustment for risk.Rather than repeat what I said in a much longer post that I had on the topic, let me summarize the points that I made there. When value investors talk about protecting themselves from risk by using a margin of safety, they are talking about building a buffer between value and price, but to use the margin of safety, you need to value a stock first. To get that value, you need a risk measure, and that brings us back full circle to how you adjust for risk, when valuing companies.

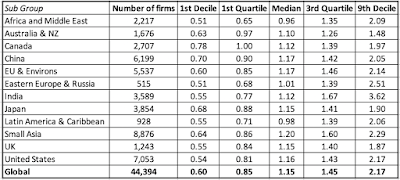

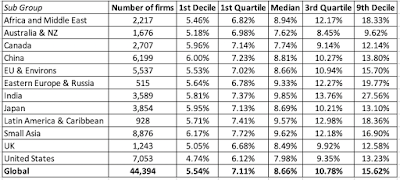

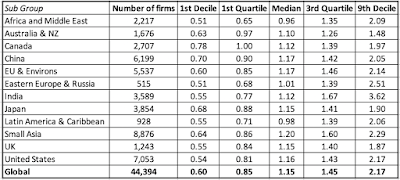

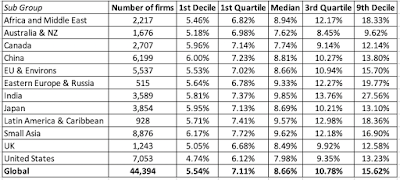

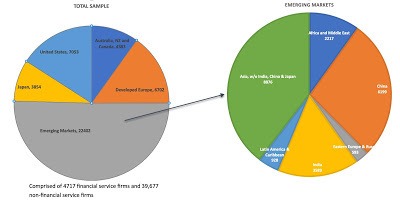

Relative Risk in 2020With that long lead-in, let's take a look at how companies measured up on relative risk measures, at the start of 2020. In keeping with my argument in the last section that you can use alternative risk measures, I will report on three alternative risk measures:Betas: I start with betas, estimated with conventional regressions of returns on the stock against a market index, for each of the companies in my sample. To get a measure of how these betas vary across companies, I have a distribution of betas, broken down globally and for regions of the world: It is worth noting that, at least for public companies, half of all companies have betas between 0.85 and 1.45, globally. If you are wondering why the betas are not higher for companies in riskier parts of the word, it is worth emphasizing that betas are scaled around one, no matter of the world you are in, and are not designed to convey country risk. (The equity risk premiums that I wrote about in my last post carry that weight.)Relative Standard Deviation: For those who do not buy into the notion that the marginal investors are diversified and that the only risk that matters is market risk, I report on the standard deviation in stock prices (using the last two years of data):

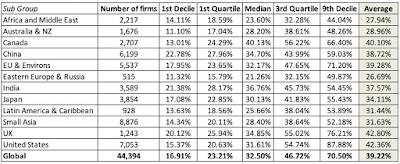

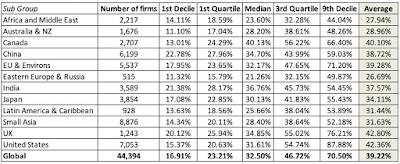

It is worth noting that, at least for public companies, half of all companies have betas between 0.85 and 1.45, globally. If you are wondering why the betas are not higher for companies in riskier parts of the word, it is worth emphasizing that betas are scaled around one, no matter of the world you are in, and are not designed to convey country risk. (The equity risk premiums that I wrote about in my last post carry that weight.)Relative Standard Deviation: For those who do not buy into the notion that the marginal investors are diversified and that the only risk that matters is market risk, I report on the standard deviation in stock prices (using the last two years of data):

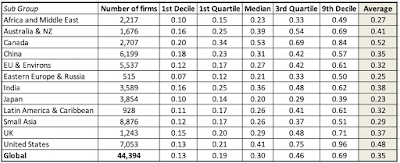

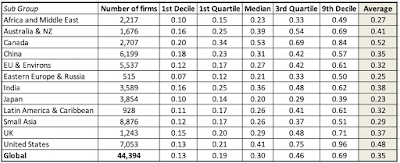

Note that you can convert these numbers into relative measures, resembling betas, by dividing by the average standard deviation of all stocks. Thus, if you have a US stock with an annualized standard deviation of 35.00% in stock returns, you would divide that number by the average for US equities of 42.36% to arrive a relative standard deviation of 0.826 (=35.00%/42.36%).High-Low Risk: For those who prefer a non-parametric and more intuitive measure of risk, I compute a risk measure by looking at the difference between high and low prices in the most recent year, and dividing by the sum of the two numbers. Thus, for a stock that has a high price of 20 and a low price of 12, during the course of a year, this measure would yield 0.25 ((20-12)/ (20+12)). Note that the bigger the range in prices, the more risky a stock looks on this measure, and this too is broken down globally and by region:

Note that you can convert these numbers into relative measures, resembling betas, by dividing by the average standard deviation of all stocks. Thus, if you have a US stock with an annualized standard deviation of 35.00% in stock returns, you would divide that number by the average for US equities of 42.36% to arrive a relative standard deviation of 0.826 (=35.00%/42.36%).High-Low Risk: For those who prefer a non-parametric and more intuitive measure of risk, I compute a risk measure by looking at the difference between high and low prices in the most recent year, and dividing by the sum of the two numbers. Thus, for a stock that has a high price of 20 and a low price of 12, during the course of a year, this measure would yield 0.25 ((20-12)/ (20+12)). Note that the bigger the range in prices, the more risky a stock looks on this measure, and this too is broken down globally and by region:

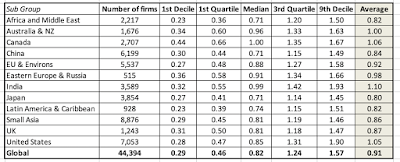

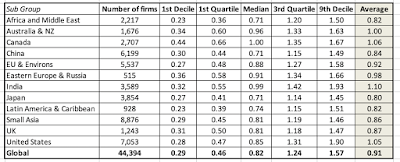

As with the other risk measures, this too can be converted into a relative risk measure, by dividing by the average.Earnings Variability: Finally, for those who trust accountants more than markets (even though I am not one of them), I have computed a risk measure that is built around earnings variability, computed by looking at the standard deviation in net income over the last 10 years for each firm, and converted into a standardized measure, by dividing by the average net income over the ten years (a coefficient of variation in net income), The global and regional breakdown is below:

As with the other risk measures, this too can be converted into a relative risk measure, by dividing by the average.Earnings Variability: Finally, for those who trust accountants more than markets (even though I am not one of them), I have computed a risk measure that is built around earnings variability, computed by looking at the standard deviation in net income over the last 10 years for each firm, and converted into a standardized measure, by dividing by the average net income over the ten years (a coefficient of variation in net income), The global and regional breakdown is below:

The earnings variability number has a bigger selection bias than the other measures, because it requires a longer history (10 years of data) and positive earnings, cutting the sample size down significantly. Here again, dividing a company's coefficient of variation in net income by the average value across all companies will give you a relative risk measure.I follow up by looking at median values for each of the risk measures by industry grouping. Since I have 94 industry groupings, I will not report them all here, but you can download the data on all of the industry groupings, by clicking here.

The earnings variability number has a bigger selection bias than the other measures, because it requires a longer history (10 years of data) and positive earnings, cutting the sample size down significantly. Here again, dividing a company's coefficient of variation in net income by the average value across all companies will give you a relative risk measure.I follow up by looking at median values for each of the risk measures by industry grouping. Since I have 94 industry groupings, I will not report them all here, but you can download the data on all of the industry groupings, by clicking here.

Hurdle Rates in 2020The relative risk measures are a means to an end, since the only reason for computing them is to use them to get to required returns. In this section, I begin by looking at the cost of equity, then bring in the cost of debt and close of by looking at the cost of capital.

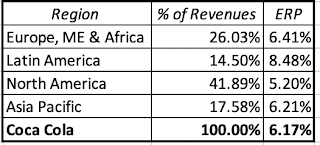

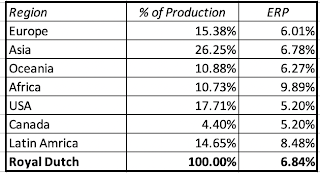

a. Cost of EquityThere are three ingredients that go into the cost of equity and the last few posts have laid the foundations for the three inputs:

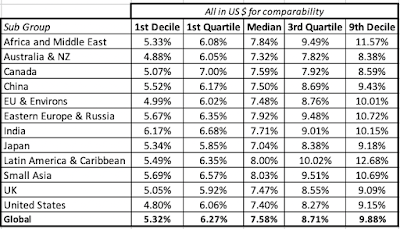

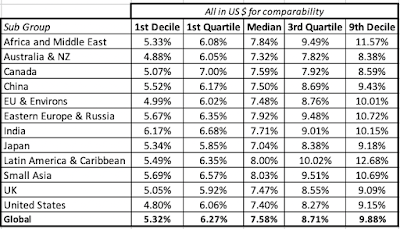

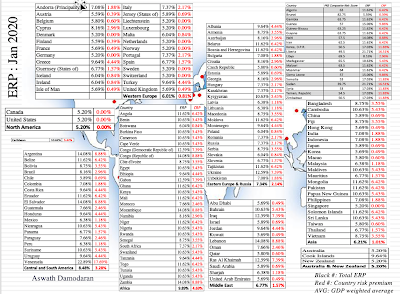

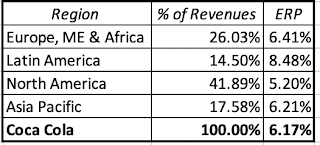

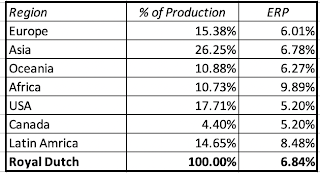

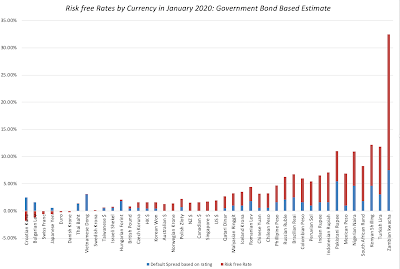

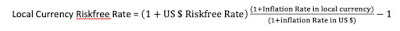

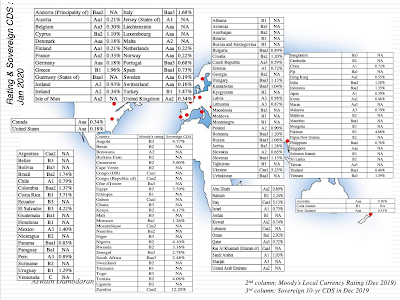

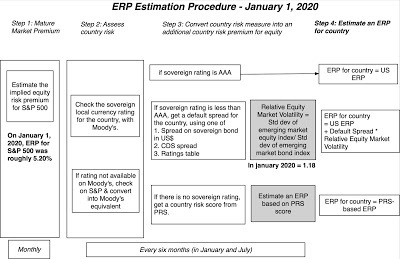

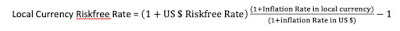

The risk free rate is a function of the currency you choose to compute your hurdle rates in, and will be higher for high-inflation currencies than low-inflations ones. Since I will be comparing and aggregating costs of equity across more than 40,000 firms spread across the world, I will compute their costs of equity in US dollars, using the US T.Bond rate as of January 1, 2020, as the risk free rate. You can convert these into any other currency, using the differential inflation approach that I described in my earlier post from a couple of weeks ago.The equity risk premium for a company is a function of where it does business, and in my last data update post, I described my approach to estimating equity risk premiums for individual countries, and the process of weighting these (using either revenues or production) to get equity risk premiums for companies.For the relative risk measure, I will use betas but as I argued in the last section, I am agnostic about what you prefer to use instead. Thus, if you prefer earnings variabliity as a measure, you can use relative earnings variability as your risk measure.With these inputs, I estimate the costs of equity for all of the companies in my database, and report the distribution in the table below:

Comparing this distribution to the one for betas, earlier in this post, you will notice a wider spread in the numbers across regions, as we bring in equity risk premium differences into the calculation.

Comparing this distribution to the one for betas, earlier in this post, you will notice a wider spread in the numbers across regions, as we bring in equity risk premium differences into the calculation.

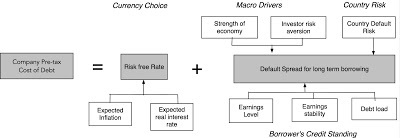

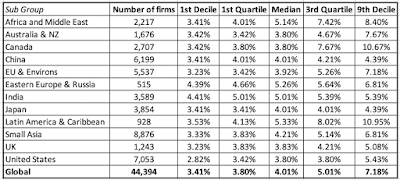

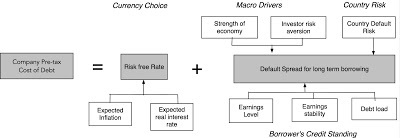

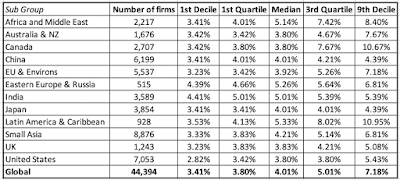

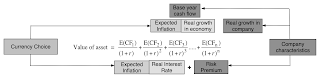

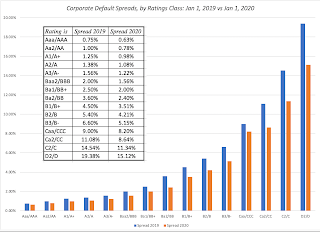

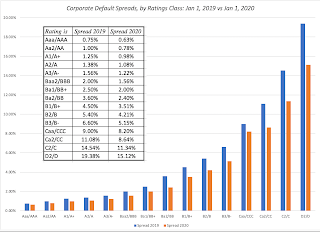

b. Cost of DebtThe cost of debt is a simpler exercise, since it is a measure of the rate at which companies can borrow money today, not a reflection of the rates at which they have borrowed in the past. It is a function of the risk free rate and the default spread: As with the cost of equity, the risk free rate is a function of the currency in which you estimate the cost of debt in, and I will estimate the costs of debt for all companies in US dollars, again to make comparisons across companies. For the default spread, I have little choice but to use bludgeon measures, since I cannot assess credit risk for 40,000 plus companies. For companies that have an S&P bond rating (about 15% of the sample), I use the rating to estimate a default spread. For the rest, I estimate synthetic bond ratings based on financial ratios (interest coverage and debt ratios). The US $ pre-tax cost of debt distribution is below:

As with the cost of equity, the risk free rate is a function of the currency in which you estimate the cost of debt in, and I will estimate the costs of debt for all companies in US dollars, again to make comparisons across companies. For the default spread, I have little choice but to use bludgeon measures, since I cannot assess credit risk for 40,000 plus companies. For companies that have an S&P bond rating (about 15% of the sample), I use the rating to estimate a default spread. For the rest, I estimate synthetic bond ratings based on financial ratios (interest coverage and debt ratios). The US $ pre-tax cost of debt distribution is below:

Since these costs are all in US dollars, the differences across regions reflect difference in country default risk and reflect wide divergences. It is worth noting that the tax law tilt towards debt, represented in the fact that interest expenses are tax deductible and cash flows to equity (dividends and buybacks) have to come from after-tax cash flows, is not just a phenomenon for the US, but true over much of the world, with the Middle East representing the holdout. This tax benefit shows up in the cost of capital, through the conversion of the pre-tax cost of debt into an after-tax cost, using the marginal tax rate to make the adjustment:After-tax cost of debt = Pre-tax cost of debt (1 - Marginal Tax Rate)In my sample, I use the marginal tax rate of the country in which a company is incorporated. You can find these marginal tax rates, which KPMG should be credited for collecting, also on my website for download.

c. Debt Ratios and Costs of CapitalThe final piece of the puzzle in computing the cost of capital is the mix of debt and equity that companies use in funding their operations. In keeping with the cost of capital being a measure of what companies have to pay for their debt and equity today, I use the market values of equity and debt, with leases converted into debt and included in the latter, to compute the cost of capital. While I will talk in more detail about debt loads and choices in a future post, you can sense of the debt load at companies, as a percent of capital (in market value terms) in the table below below:

With these debt ratios, and using the costs of equity and debt also shown above, I compute costs of capital, in US dollar terms, for all publicly traded companies and the resulting distribution is below:

This is a table that I will use, and have already put to use, in valuing companies since it provides a quick and effective way to estimate discount rates for companies, without losing yourself in the details. Thus, when valuing a young, money-losing public company in the US (like Casper, the only mattress-maker that went public last week), I will use a cost of capital of 9.15%, representing the 90th percentile of US firms, whereas to value a slow-growing European company in a stable business, like Heineken, my cost of capital will be 6.02%, the 25th percentile of European companies. For all companies, the median cost of capital of 7.58% is a good proxy for the number that all companies will converge towards, as they approach maturity. If all of these numbers look low to you, that is because they reflect a risk free rate, in US dollars, that is low, and if it does rise, it will carry these numbers upwards. As with the risk measures, I have estimated costs of equity, debt and capital, by industry group and you can download them for all companies globally, as well as regionally (US, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan and Australia/Canada) and for India and China, separately.

YouTube Video

Downloadable Data

Industry Average Risk Measures at start of 2020Betas, by industry (Global, US, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, Australia/Canada, India, China)Costs of Debt, Equity and Capital, by industry (Global, US, Emerging Markets, Europe, Japan, Australia/Canada, India, China)Marginal tax rates, by country, for 2020

Relative Risk MeasuresTo get from the macro risk measures to company-level hurdle rates, you need to make judgments on relative risk. Put simply, if you buy into the proposition, like I do, that some companies/investments are riskier than others, you need a measure of relative risk that captures this variation. It is in this context that I think of betas, a loaded concept that carries with it the baggage of modern portfolio theory and efficient markets. If you add to this the standard approach to estimating betas, built on looking at past prices and running regressions against market indices, you have the makings of a perfect storm, designed to drive value investors to apoplexy. I have no desire to re-litigate these arguments, partly because those for and opposed to betas are set in their ways, but let me suggest some compromise propositions. Relative Risk Proposition 1 : You do not need to believe in betas to do financial analysis and valuation. While there are many who seem to tie discounted cash flow valuations to the use of beta or betas, there is nothing inherently in a DCF that requires that you make this leap:

While the discount rate in a DCF is a risk-adjusted number, the approach is agnostic about how you measure risk and adjust discount rates for that risk.Relative Risk Proposition 2: If you don't like to or want to measure relative risk with betas, you can come up with alternate measures that better reflect your view of how risk should be measured. While I do use beta as my proxy for risk, I do so with open eyes, recognizing its many limitations as a risk measure, and I have been always willing to consider competing risk measures. In fact, I have presented alternate measures of risk, drawing on the two building blocks of betas that draw the most pushback. The first is the assumption that marginal investors are diversified, and that the only risk that needs to be measured is the risk that cannot be diversified away. The second is its use of prices (stock and market) to estimate risk, seemingly contradicting intrinsic value's basic precept that market prices are not trustworthy. Since a picture is worth a thousand words, here a few alternative risk measures to consider, if you don't trust betas;

Put simply, if your primary problem with betas is the assumption that marginal investors are diversified, there are total risk measures that are built around measuring the total risk in a company or investment, by looking at either the standard deviation or adding premiums (small cap, company-specific risk) to the traditional risk and return model. If your concern is that past prices are being used to estimate betas, you can switch to using accounting earnings and computing risk measures either from the perspective of diversified investors (accounting beta) or undiversified ones (earnings variability).Relative Risk Proposition 3: The margin of safety is not a competitor to any of the risk measures above, since it is a post-value adjustment for risk.Rather than repeat what I said in a much longer post that I had on the topic, let me summarize the points that I made there. When value investors talk about protecting themselves from risk by using a margin of safety, they are talking about building a buffer between value and price, but to use the margin of safety, you need to value a stock first. To get that value, you need a risk measure, and that brings us back full circle to how you adjust for risk, when valuing companies.

Put simply, if your primary problem with betas is the assumption that marginal investors are diversified, there are total risk measures that are built around measuring the total risk in a company or investment, by looking at either the standard deviation or adding premiums (small cap, company-specific risk) to the traditional risk and return model. If your concern is that past prices are being used to estimate betas, you can switch to using accounting earnings and computing risk measures either from the perspective of diversified investors (accounting beta) or undiversified ones (earnings variability).Relative Risk Proposition 3: The margin of safety is not a competitor to any of the risk measures above, since it is a post-value adjustment for risk.Rather than repeat what I said in a much longer post that I had on the topic, let me summarize the points that I made there. When value investors talk about protecting themselves from risk by using a margin of safety, they are talking about building a buffer between value and price, but to use the margin of safety, you need to value a stock first. To get that value, you need a risk measure, and that brings us back full circle to how you adjust for risk, when valuing companies.Relative Risk in 2020With that long lead-in, let's take a look at how companies measured up on relative risk measures, at the start of 2020. In keeping with my argument in the last section that you can use alternative risk measures, I will report on three alternative risk measures:Betas: I start with betas, estimated with conventional regressions of returns on the stock against a market index, for each of the companies in my sample. To get a measure of how these betas vary across companies, I have a distribution of betas, broken down globally and for regions of the world:

It is worth noting that, at least for public companies, half of all companies have betas between 0.85 and 1.45, globally. If you are wondering why the betas are not higher for companies in riskier parts of the word, it is worth emphasizing that betas are scaled around one, no matter of the world you are in, and are not designed to convey country risk. (The equity risk premiums that I wrote about in my last post carry that weight.)Relative Standard Deviation: For those who do not buy into the notion that the marginal investors are diversified and that the only risk that matters is market risk, I report on the standard deviation in stock prices (using the last two years of data):

It is worth noting that, at least for public companies, half of all companies have betas between 0.85 and 1.45, globally. If you are wondering why the betas are not higher for companies in riskier parts of the word, it is worth emphasizing that betas are scaled around one, no matter of the world you are in, and are not designed to convey country risk. (The equity risk premiums that I wrote about in my last post carry that weight.)Relative Standard Deviation: For those who do not buy into the notion that the marginal investors are diversified and that the only risk that matters is market risk, I report on the standard deviation in stock prices (using the last two years of data):

Note that you can convert these numbers into relative measures, resembling betas, by dividing by the average standard deviation of all stocks. Thus, if you have a US stock with an annualized standard deviation of 35.00% in stock returns, you would divide that number by the average for US equities of 42.36% to arrive a relative standard deviation of 0.826 (=35.00%/42.36%).High-Low Risk: For those who prefer a non-parametric and more intuitive measure of risk, I compute a risk measure by looking at the difference between high and low prices in the most recent year, and dividing by the sum of the two numbers. Thus, for a stock that has a high price of 20 and a low price of 12, during the course of a year, this measure would yield 0.25 ((20-12)/ (20+12)). Note that the bigger the range in prices, the more risky a stock looks on this measure, and this too is broken down globally and by region:

Note that you can convert these numbers into relative measures, resembling betas, by dividing by the average standard deviation of all stocks. Thus, if you have a US stock with an annualized standard deviation of 35.00% in stock returns, you would divide that number by the average for US equities of 42.36% to arrive a relative standard deviation of 0.826 (=35.00%/42.36%).High-Low Risk: For those who prefer a non-parametric and more intuitive measure of risk, I compute a risk measure by looking at the difference between high and low prices in the most recent year, and dividing by the sum of the two numbers. Thus, for a stock that has a high price of 20 and a low price of 12, during the course of a year, this measure would yield 0.25 ((20-12)/ (20+12)). Note that the bigger the range in prices, the more risky a stock looks on this measure, and this too is broken down globally and by region:

As with the other risk measures, this too can be converted into a relative risk measure, by dividing by the average.Earnings Variability: Finally, for those who trust accountants more than markets (even though I am not one of them), I have computed a risk measure that is built around earnings variability, computed by looking at the standard deviation in net income over the last 10 years for each firm, and converted into a standardized measure, by dividing by the average net income over the ten years (a coefficient of variation in net income), The global and regional breakdown is below:

As with the other risk measures, this too can be converted into a relative risk measure, by dividing by the average.Earnings Variability: Finally, for those who trust accountants more than markets (even though I am not one of them), I have computed a risk measure that is built around earnings variability, computed by looking at the standard deviation in net income over the last 10 years for each firm, and converted into a standardized measure, by dividing by the average net income over the ten years (a coefficient of variation in net income), The global and regional breakdown is below:

The earnings variability number has a bigger selection bias than the other measures, because it requires a longer history (10 years of data) and positive earnings, cutting the sample size down significantly. Here again, dividing a company's coefficient of variation in net income by the average value across all companies will give you a relative risk measure.I follow up by looking at median values for each of the risk measures by industry grouping. Since I have 94 industry groupings, I will not report them all here, but you can download the data on all of the industry groupings, by clicking here.

The earnings variability number has a bigger selection bias than the other measures, because it requires a longer history (10 years of data) and positive earnings, cutting the sample size down significantly. Here again, dividing a company's coefficient of variation in net income by the average value across all companies will give you a relative risk measure.I follow up by looking at median values for each of the risk measures by industry grouping. Since I have 94 industry groupings, I will not report them all here, but you can download the data on all of the industry groupings, by clicking here.Hurdle Rates in 2020The relative risk measures are a means to an end, since the only reason for computing them is to use them to get to required returns. In this section, I begin by looking at the cost of equity, then bring in the cost of debt and close of by looking at the cost of capital.

a. Cost of EquityThere are three ingredients that go into the cost of equity and the last few posts have laid the foundations for the three inputs:

The risk free rate is a function of the currency you choose to compute your hurdle rates in, and will be higher for high-inflation currencies than low-inflations ones. Since I will be comparing and aggregating costs of equity across more than 40,000 firms spread across the world, I will compute their costs of equity in US dollars, using the US T.Bond rate as of January 1, 2020, as the risk free rate. You can convert these into any other currency, using the differential inflation approach that I described in my earlier post from a couple of weeks ago.The equity risk premium for a company is a function of where it does business, and in my last data update post, I described my approach to estimating equity risk premiums for individual countries, and the process of weighting these (using either revenues or production) to get equity risk premiums for companies.For the relative risk measure, I will use betas but as I argued in the last section, I am agnostic about what you prefer to use instead. Thus, if you prefer earnings variabliity as a measure, you can use relative earnings variability as your risk measure.With these inputs, I estimate the costs of equity for all of the companies in my database, and report the distribution in the table below:

Comparing this distribution to the one for betas, earlier in this post, you will notice a wider spread in the numbers across regions, as we bring in equity risk premium differences into the calculation.

Comparing this distribution to the one for betas, earlier in this post, you will notice a wider spread in the numbers across regions, as we bring in equity risk premium differences into the calculation.b. Cost of DebtThe cost of debt is a simpler exercise, since it is a measure of the rate at which companies can borrow money today, not a reflection of the rates at which they have borrowed in the past. It is a function of the risk free rate and the default spread:

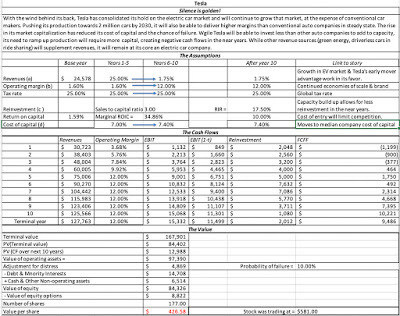

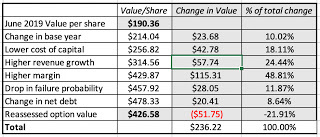

As with the cost of equity, the risk free rate is a function of the currency in which you estimate the cost of debt in, and I will estimate the costs of debt for all companies in US dollars, again to make comparisons across companies. For the default spread, I have little choice but to use bludgeon measures, since I cannot assess credit risk for 40,000 plus companies. For companies that have an S&P bond rating (about 15% of the sample), I use the rating to estimate a default spread. For the rest, I estimate synthetic bond ratings based on financial ratios (interest coverage and debt ratios). The US $ pre-tax cost of debt distribution is below: