Aswath Damodaran's Blog, page 19

May 29, 2018

User and Subscriber Businesses: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly!

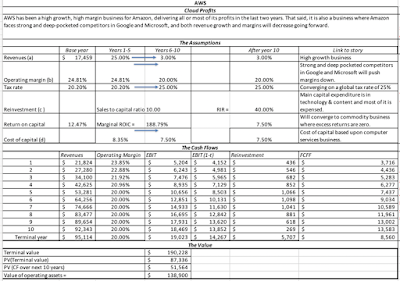

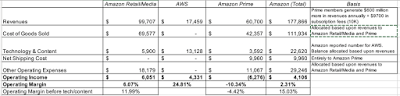

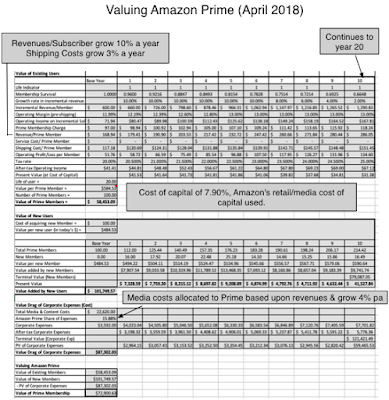

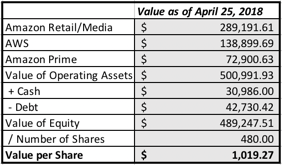

In a series of posts over the course of the last year, I argued that you can value users and subscribers at businesses, using first principles in valuation, and have used the approach to value Uber riders, Amazon Prime members and Spotify & Netflix subscribers. With each iteration, I have learned a few things about user value and ways of distinguishing between user bases that can create substantial value from user bases that not only are incapable of creating value but can actively destroy it. I was reminded of these principles this week, first as I wrote about Walmart's $16 billion bid for 77% of Flipkart, a deal at least partially motivated by shopper numbers, then again as I read a news story about MoviePass and the potential demise of its "too good to be true" model, and finally as I tripped over a LimeBike on my walk home.

User Based ValueMy attempt to build a user-based valuation model was triggered by a comment that I got on a valuation that I had done of Uber about a year ago on my blog. In that post, I approached Uber, as I would any other business, and valued it, based upon aggregated revenues, earnings and cash flows, discounted back at a company-wide cost of capital. I was taken to task for applying an old-economy valuation approach to a new-economy company and was told that that the companies of today derive their value from customers, users and subscribers. While my initial response was that you cannot pay dividends with users, I realized that there was a core truth to the critique and that companies are increasingly building their businesses around their members.

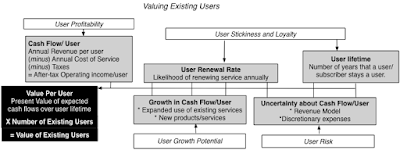

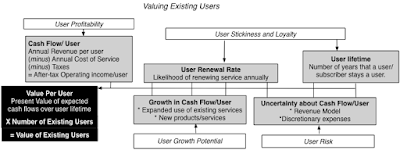

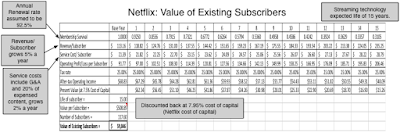

Consequently, I went back to valuation first principles, where the value of any asset is a function of its cashflows, growth and risks, and adapted that approach to valuing a user or subscriber:

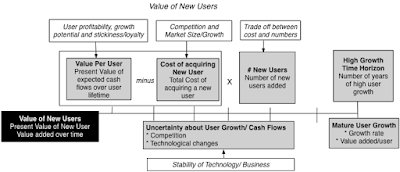

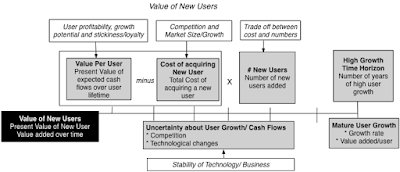

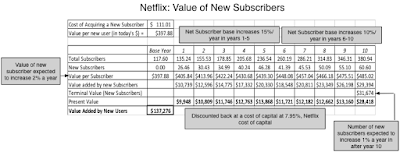

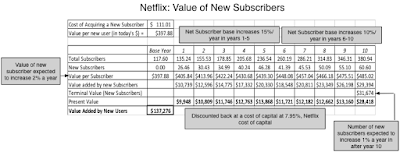

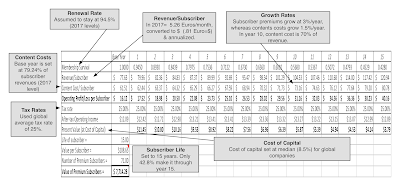

To get from the value of existing users to the value of an entire company, I incorporated the value effect of new users, bringing in the cost of acquiring a new user into the value:

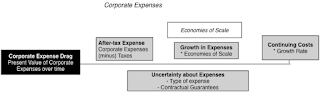

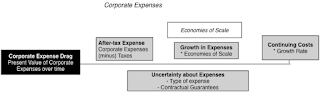

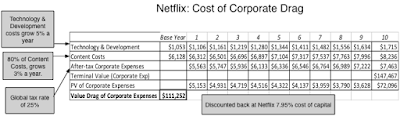

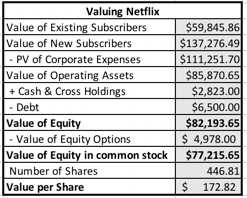

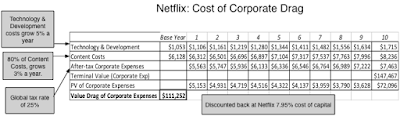

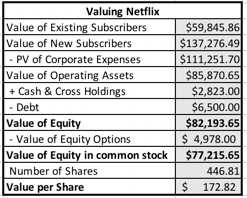

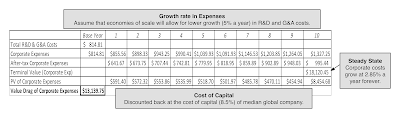

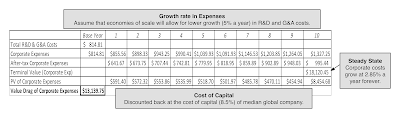

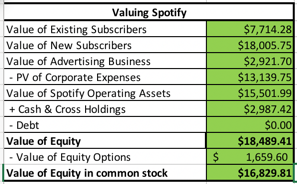

I applied closure by consider all corporate costs that are not directly related to users or subscribers in a corporate cost drag, a drag because it reduces the value of the business: Cumulating the value of existing and new users, and netting out the corporate cost drag yields the value of operating assets, i.e., the same value that you would derive by discounting the free cash flows to the entire business by its overall cost of capital. You would still need to clean up, by adding in cash, netting out debt and dealing with outstanding options, but that process is the same in both models.

Cumulating the value of existing and new users, and netting out the corporate cost drag yields the value of operating assets, i.e., the same value that you would derive by discounting the free cash flows to the entire business by its overall cost of capital. You would still need to clean up, by adding in cash, netting out debt and dealing with outstanding options, but that process is the same in both models.

I would hasten to add that a user-based value model is not a panacea to any of the valuation challenges that we face with young, user-based companies. In fact, the difficulties with obtaining the raw data needed on user renewal rates and acquisition costs can be so daunting that any potential advantages that you obtain by looking at user-level value can be drowned out by noise. It is also worth emphasizing that its user-focus notwithstanding, this model is grounded in fundamentals, with value coming, as it always does, from cash flows, growth and risk. I am still learning about this model, but I have put down what I have learned over the last year, when valuing Uber, Amazon Prime and Netflix, into a paper that you can download, read and critique.

Good, Bad and Indifferent User-based ModelsOne of the motivations for my user-focused valuation was based upon casual empiricism. In my view, many venture capitalists and public investors are pricing user-based companies on user count, with only a few seriously trying to distinguish between good, indifferent and bad user-based models. One of the bonuses of using a user-based model is that it provides a framework for differentiating between great and mediocre user-based companies.

Drivers of Value A standard critique that old-time value investors have of user-based companies is that they all lose money, but that is not true. There are user-based companies that make money, but it is also true that the user-based model is still in its infancy and that many user-based companies are young, and therefore lose money. That said, there are elements of the cost structure that you can look at, to make judgments on which user-based companies are most likely to grow out of their problems and which ones are just going to grow their problems.

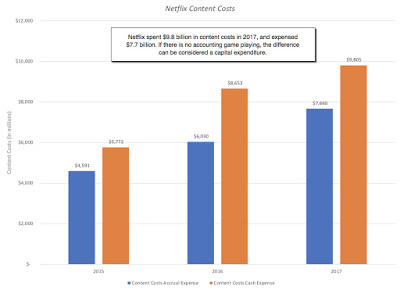

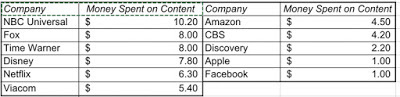

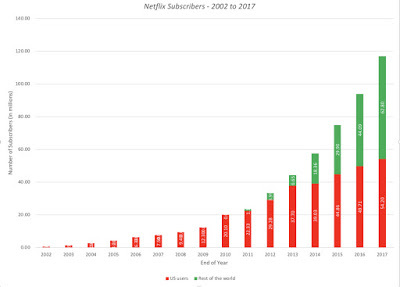

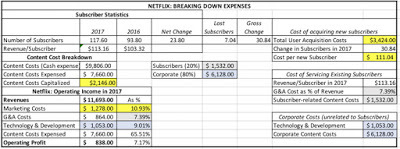

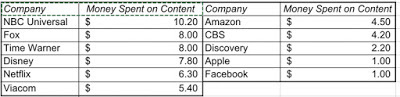

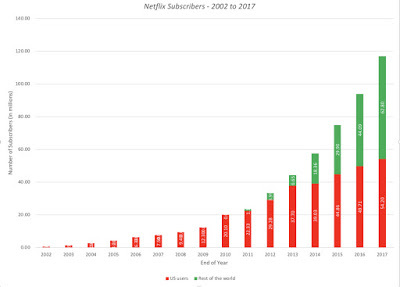

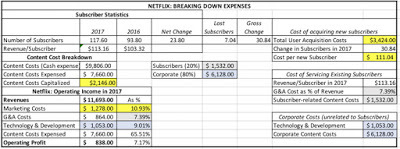

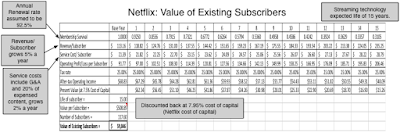

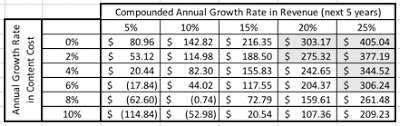

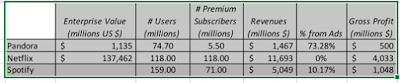

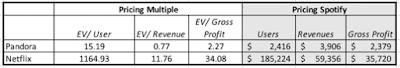

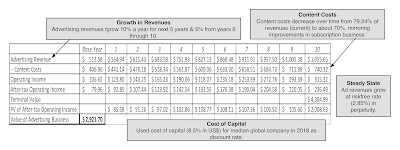

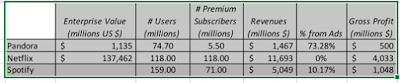

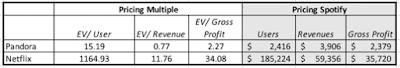

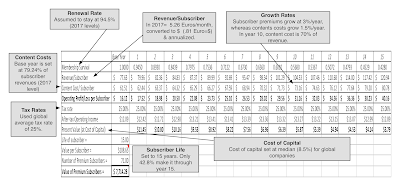

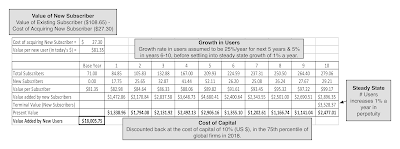

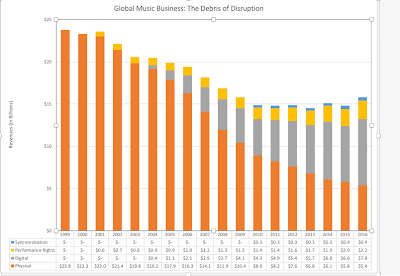

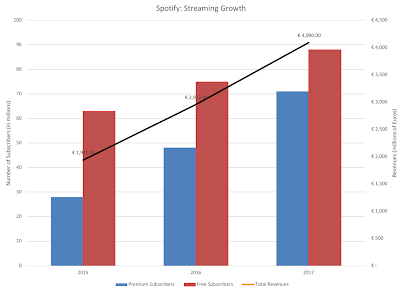

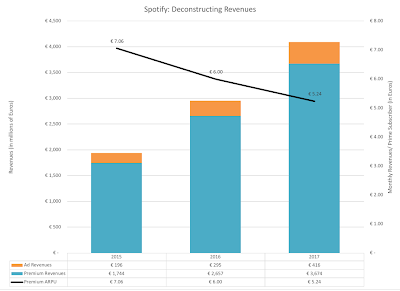

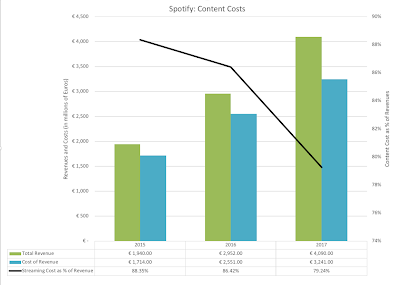

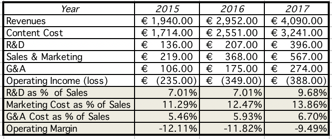

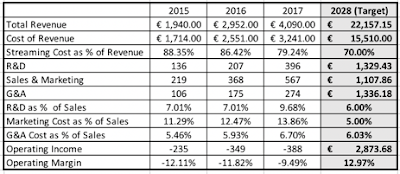

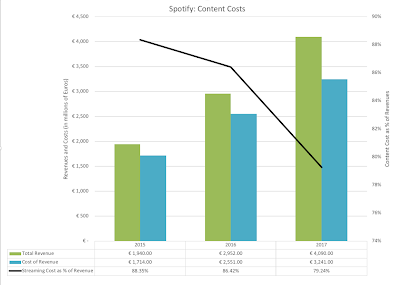

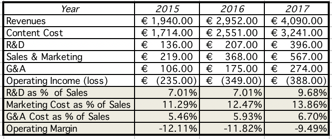

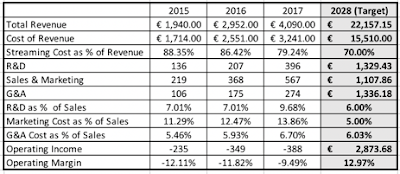

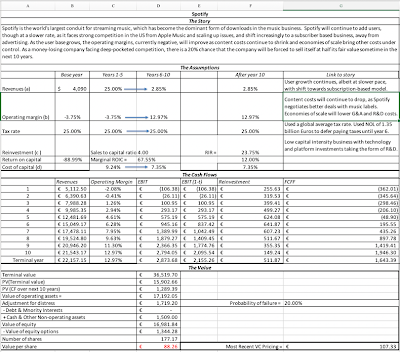

a. Cost Structure: Most young, user-based companies lose money but at the risk of sounding unbalanced, there are good ways to lose money and bad ones, from a value perspective. Servicing Existing Users versus New User Acquisition: From a value perspective, it is far better for a company to be losing money, because it is spending money trying to acquire new users, than it is to be losing money, because it costs so much to service existing users. The latter signals a bad business model, at least for the moment, whereas the former offers a semblance of hope.Fixed versus Variable Costs: For mature companies with established business models, it is better to have a more flexible cost structure (with more variable costs and less fixed costs). With money-losing, high-growth companies, the reverse is true, since it is the fixed cost portion that yields economies of scale, as the company grows.b. Growth: Repeating a value nostrum, growth is not always value-creating and not all growth is created equal.Existing versus New Users: A user-based model, where you can grow cash flows from existing users is more valuable, other things remaining equal, than a user-based model that is dependent on adding new users for growth. The reason is simple. Since a company already has expended resources to get existing users, any added revenue it derives from them is more likely to flow directly to the bottom line. Adding new users is more expensive, partly because it costs money to acquire them, but also because new users may not be as active or lucrative as existing ones.Cost of New User Acquisition: This is a corollary of the first proposition, since the value of a new user is net of user acquisition costs. Consequently, user-based companies that are more cost-efficient in adding new users will be worth more than user-based companies that spend considerable amounts on promotion on marketing, to the same end. This contrast is best illustrated by looking at Netflix and Spotify, both subscriber-based companies, but with very different models for paying for content. Netflix pays for content as a fixed cost, and derives economies of scale, when it adds fresh subscribers, whereas Spotify pays for content, based upon how much subscribers listen to songs, making it a variable and existing user based cost. As a result, Netflix derives much higher value from both existing and new subscribers:

NetflixSpotifyNumber of Subscribers117.671Annual Revenue/Subscriber $ 113.16 $ 77.63 Subscriber Service Expenses (as %)18.90%79.24%CAGR in subscriber count223.93%369.86%

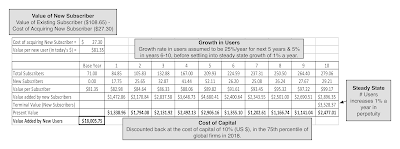

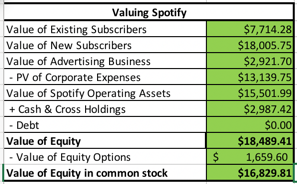

Value per Existing Subscriber $ 508.89 $ 108.65 Cost of acquiring New Subscriber $ 111.01 $ 27.30 Value per New Subscriber $ 397.88 $ 81.35 Value of all Existing Subscribers $ 59,845.86 $ 7,714.28 Value of all New Subscribers $ 137,276.49 $ 20,764.56 - Corporate Cost Drag $ 111,251.70 $ 13,139.75 =Value of Operating Assets $ 85,870.65 $ 15,339.10

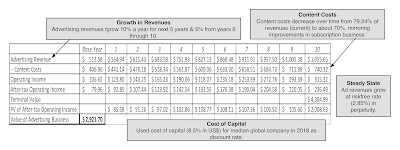

c. Revenue Models: There are three user-based models, the first is the subscription-based model (that Netflix uses), the second is the advertising-based model (that Yelp uses) and the third is a transaction-based model (that Uber uses). There are companies that use hybrid versions, with Amazon Prime (membership fees and incremental sales) and Spotify (Subscription plus Advertising) being good examples. Each model comes with its pluses and minuses. Subscription models tend to be stickier (making revenues more predictable) but they offer less upside potential (it is difficult to grow subscription fees at high rates).Advertising models scale up faster, since they require little in capital investment and adding new users is easier (since they free), but revenues are heavily driven by user intensity (how much time you can get users to stay in your ecosystem) and exclusive data (collected in the course of usage).Transaction models are the riskiest, since they require users to use your product or service, but they also offer the most upside, since your upside is less constrained. Amazon Prime's value, in my view, does not stem primarily from the subscription revenues of $99/year but from Amazon's capacity to sell Prime members more products and services.While no model dominates, picking the wrong revenue model can quickly handicap a business. For instance, using a subscription-based model for a transaction business, where usage varies widely across users, can result in self-selection, where the most intense users choose the subscription-based model to save money, and less intense users stay with a transaction-based model.

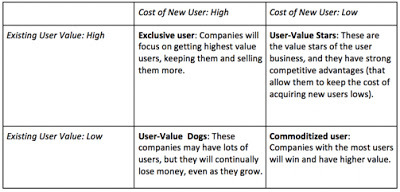

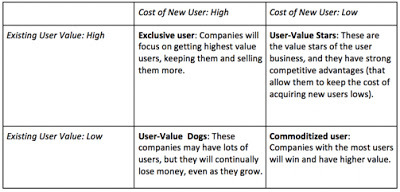

Differentiating across User-based ModelsWith the user-based framework in place, we can start distinguishing between user-based companies. Using existing user value and new customer acquisition costs as the dimensions, we can derive a matrix of companies that go from user-value stars to user-value dogs.

While the combination of high user value with low user acquisition costs may sound like a pipe dream, it is what network benefits and big data, if they exist, promise to deliver. Network benefits refer to the possibility that as you grow bigger, it becomes easier for you to get even bigger, making it less costly to acquire new users. That is the promise of ride sharing, for instance, where as a company gets a larger share of a ride sharing market, both drivers and customers are more likely to switch to it, the former, because they get more customers and the latter, because they find rides more quickly.Big data, in a value framework, offers user-based companies an advantage, since what you learn about your users can be used to either sell them more products or services (if you are a transaction-based company), charge them higher premiums (if you are subscription-based) or direct advertising more effectively (if advertising-based). Many user-based companies aspire to have network benefits and to use data well, but only a few succeed.

The Pricing Game

As I look at user-based companies, some of which are being priced at billions of dollars, I am struck by how few of them are built to be long term businesses and how many of them are being priced on user numbers and buzz words. Using the framework from the last section, I would like to develop some common features that bad user-businesses seems to share in common and use one high profile examples, MoviePass , to make my case.

Mediocre User-based Companies

Given that so many young companies market themselves, based upon user and subscriber numbers, and that some of them can become valuable companies, are there signs that you can look for that separate the good from the mediocre companies? I think so, and here are a few red flags:

All about users, all the time: If the entire sales pitch that a company makes to investors is about its user or subscriber numbers, rather than its operating results (revenues and operating profits/losses), it is a dangerous sign. While large user numbers are a positive, it requires a business model to convert these users into revenues and profits, and that business model will not develop spontaneously. Companies that do not work on developing viable business models go bankrupt with lots of users.Opacity about user data: It is ironic that companies that market themselves to investors, based upon user numbers, are often opaque about key dimensions on users, including renewal (churn) rates, user behavior and side costs related to users. The companies that are most opaque are often the ones that have user models that are not sustainable.Bad business models: If having no business model to convert users to operating results is a bad sign, it is an even worse sign when you have a business model that is designed to deliver losses, not only in its current form, but with no light at the end of the tunnel. That is usually the consequence of having losses that scale up as the company gets bigger, because there are economies of scale. Loose talk about data: The fall back for many user based companies that cannot defend their business models is that they will find a way to use the data that they will collect from their users to make money in the future (from targeted advertising or additional products and services), without any serious attempt to explain why the data will give them an edge.And externalities: Many user based companies argue that their "innovative" twists on an existing business will both expand and alter the business, leading to benefits for other players in that business, who, in turn, will share their benefits with the user based companies.The bottom line is simple. It is easy to build user numbers, if you sell a product or service at way below cost, but if your objective is build a long-standing user-based companies, you need a pathway to profitability that is defined early and worked on continuously.

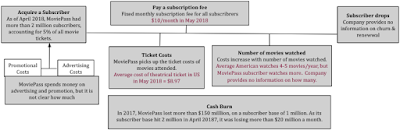

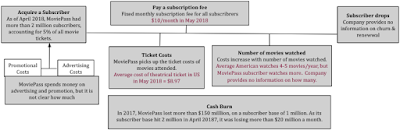

MoviePass: Too Good to be True? If you subscribe to MoviePass, for a monthly subscription of $10, you get to watch one theatrical movie, every day, for the entire month. Given that the average price of a theater ticket in the US is $9, this sounds like an insanely good deal, and for an avid movie goer, it is, and the service had two million subscribers in May 2018. MoviePass, though, pays the theaters for the tickets, creating a model that is more designed to drive it into bankruptcy than to deliver profits.

MoviePass EconomicsWhen confronted by the insanity of the business model, Mitch Lowe, the CEO of MoviePass, argued that after an initial burst, where subscribers would see four or five movies a month, they would settle into watching a movie a month, allowing the service to break even. Since Mr. Lowe is a co-founder of Netflix and a former CEO of Redbox, I will concede that he knows a lot more about the movie business than I do, but this is an absurd rationale. If the only way that your service can become viable is if people don't use it very much, it is not much of a service to begin with.

MoviePass EconomicsWhen confronted by the insanity of the business model, Mitch Lowe, the CEO of MoviePass, argued that after an initial burst, where subscribers would see four or five movies a month, they would settle into watching a movie a month, allowing the service to break even. Since Mr. Lowe is a co-founder of Netflix and a former CEO of Redbox, I will concede that he knows a lot more about the movie business than I do, but this is an absurd rationale. If the only way that your service can become viable is if people don't use it very much, it is not much of a service to begin with.

In its early days, MoviePass seemed to be trying to build a viable business model, and acquired some high profile venture capital investors, but it was eventually acquired by Helios and Matheson, a data analytics firm, in a transaction in August 2017. It is Helios and Matheson, intent on giving both data and analysis a bad name, that instituted the $10 a month for a movie-a-day subscription. The subscription worked in delivering users but it, not surprisingly, came with large losses. As MoviePass has continued to burn cash (more than $20 million a month by April 2018), the share price of Helios and Matheson has collapsed, in a belated recognition of its non-viable business model.

Adding to the sense that no one in this company has a grip on reality, Ted Farnsworth, the CEO of Helios and Matheson, argued that the service would continue and had acquired a $300 million line of credit. Since his backing for this line of credit was that he could issue the remaining authorized shares at the current market price, this indicates either extreme ignorance (potential equity issues don't comprise a line of credit) or unalloyed deception, neither of which is a quality that builds trust. Along the way, there have been other attempts to rationalize the model, including the possibility of using the data collected from subscribers to target advertising and the sharing of additional revenues generated by theaters and studios from more movie going. There is nothing exclusive about the data that will be collected from MoviePass subscribers and it is unlikely that theaters and small studios, already on the brink financially, will be willing to share their revenues. In short, this is a bad business model hurtling to a bad end, and the only question is why it took so long.

The Bottom LineTo build a good user-based business, you have to start with the common sense recognition that users are not the end game, but a means to an end. Unfortunately, as long as venture capitalists and investors reward companies with high pricing, based just upon user count, we will encourage the building of bad businesses with lots of users and no pathways to becoming successful businesses.

YouTube Video

Paper on User Based Value

Going to Pieces: Valuing Users, Subscribers and CustomersBlog Posts on User-based Value

Valuing Uber RidersValuing Amazon Prime MembersValuing Spotify SubscribersValuing Netflix Subscribers

User Based ValueMy attempt to build a user-based valuation model was triggered by a comment that I got on a valuation that I had done of Uber about a year ago on my blog. In that post, I approached Uber, as I would any other business, and valued it, based upon aggregated revenues, earnings and cash flows, discounted back at a company-wide cost of capital. I was taken to task for applying an old-economy valuation approach to a new-economy company and was told that that the companies of today derive their value from customers, users and subscribers. While my initial response was that you cannot pay dividends with users, I realized that there was a core truth to the critique and that companies are increasingly building their businesses around their members.

Consequently, I went back to valuation first principles, where the value of any asset is a function of its cashflows, growth and risks, and adapted that approach to valuing a user or subscriber:

To get from the value of existing users to the value of an entire company, I incorporated the value effect of new users, bringing in the cost of acquiring a new user into the value:

I applied closure by consider all corporate costs that are not directly related to users or subscribers in a corporate cost drag, a drag because it reduces the value of the business:

Cumulating the value of existing and new users, and netting out the corporate cost drag yields the value of operating assets, i.e., the same value that you would derive by discounting the free cash flows to the entire business by its overall cost of capital. You would still need to clean up, by adding in cash, netting out debt and dealing with outstanding options, but that process is the same in both models.

Cumulating the value of existing and new users, and netting out the corporate cost drag yields the value of operating assets, i.e., the same value that you would derive by discounting the free cash flows to the entire business by its overall cost of capital. You would still need to clean up, by adding in cash, netting out debt and dealing with outstanding options, but that process is the same in both models.I would hasten to add that a user-based value model is not a panacea to any of the valuation challenges that we face with young, user-based companies. In fact, the difficulties with obtaining the raw data needed on user renewal rates and acquisition costs can be so daunting that any potential advantages that you obtain by looking at user-level value can be drowned out by noise. It is also worth emphasizing that its user-focus notwithstanding, this model is grounded in fundamentals, with value coming, as it always does, from cash flows, growth and risk. I am still learning about this model, but I have put down what I have learned over the last year, when valuing Uber, Amazon Prime and Netflix, into a paper that you can download, read and critique.

Good, Bad and Indifferent User-based ModelsOne of the motivations for my user-focused valuation was based upon casual empiricism. In my view, many venture capitalists and public investors are pricing user-based companies on user count, with only a few seriously trying to distinguish between good, indifferent and bad user-based models. One of the bonuses of using a user-based model is that it provides a framework for differentiating between great and mediocre user-based companies.

Drivers of Value A standard critique that old-time value investors have of user-based companies is that they all lose money, but that is not true. There are user-based companies that make money, but it is also true that the user-based model is still in its infancy and that many user-based companies are young, and therefore lose money. That said, there are elements of the cost structure that you can look at, to make judgments on which user-based companies are most likely to grow out of their problems and which ones are just going to grow their problems.

a. Cost Structure: Most young, user-based companies lose money but at the risk of sounding unbalanced, there are good ways to lose money and bad ones, from a value perspective. Servicing Existing Users versus New User Acquisition: From a value perspective, it is far better for a company to be losing money, because it is spending money trying to acquire new users, than it is to be losing money, because it costs so much to service existing users. The latter signals a bad business model, at least for the moment, whereas the former offers a semblance of hope.Fixed versus Variable Costs: For mature companies with established business models, it is better to have a more flexible cost structure (with more variable costs and less fixed costs). With money-losing, high-growth companies, the reverse is true, since it is the fixed cost portion that yields economies of scale, as the company grows.b. Growth: Repeating a value nostrum, growth is not always value-creating and not all growth is created equal.Existing versus New Users: A user-based model, where you can grow cash flows from existing users is more valuable, other things remaining equal, than a user-based model that is dependent on adding new users for growth. The reason is simple. Since a company already has expended resources to get existing users, any added revenue it derives from them is more likely to flow directly to the bottom line. Adding new users is more expensive, partly because it costs money to acquire them, but also because new users may not be as active or lucrative as existing ones.Cost of New User Acquisition: This is a corollary of the first proposition, since the value of a new user is net of user acquisition costs. Consequently, user-based companies that are more cost-efficient in adding new users will be worth more than user-based companies that spend considerable amounts on promotion on marketing, to the same end. This contrast is best illustrated by looking at Netflix and Spotify, both subscriber-based companies, but with very different models for paying for content. Netflix pays for content as a fixed cost, and derives economies of scale, when it adds fresh subscribers, whereas Spotify pays for content, based upon how much subscribers listen to songs, making it a variable and existing user based cost. As a result, Netflix derives much higher value from both existing and new subscribers:

NetflixSpotifyNumber of Subscribers117.671Annual Revenue/Subscriber $ 113.16 $ 77.63 Subscriber Service Expenses (as %)18.90%79.24%CAGR in subscriber count223.93%369.86%

Value per Existing Subscriber $ 508.89 $ 108.65 Cost of acquiring New Subscriber $ 111.01 $ 27.30 Value per New Subscriber $ 397.88 $ 81.35 Value of all Existing Subscribers $ 59,845.86 $ 7,714.28 Value of all New Subscribers $ 137,276.49 $ 20,764.56 - Corporate Cost Drag $ 111,251.70 $ 13,139.75 =Value of Operating Assets $ 85,870.65 $ 15,339.10

c. Revenue Models: There are three user-based models, the first is the subscription-based model (that Netflix uses), the second is the advertising-based model (that Yelp uses) and the third is a transaction-based model (that Uber uses). There are companies that use hybrid versions, with Amazon Prime (membership fees and incremental sales) and Spotify (Subscription plus Advertising) being good examples. Each model comes with its pluses and minuses. Subscription models tend to be stickier (making revenues more predictable) but they offer less upside potential (it is difficult to grow subscription fees at high rates).Advertising models scale up faster, since they require little in capital investment and adding new users is easier (since they free), but revenues are heavily driven by user intensity (how much time you can get users to stay in your ecosystem) and exclusive data (collected in the course of usage).Transaction models are the riskiest, since they require users to use your product or service, but they also offer the most upside, since your upside is less constrained. Amazon Prime's value, in my view, does not stem primarily from the subscription revenues of $99/year but from Amazon's capacity to sell Prime members more products and services.While no model dominates, picking the wrong revenue model can quickly handicap a business. For instance, using a subscription-based model for a transaction business, where usage varies widely across users, can result in self-selection, where the most intense users choose the subscription-based model to save money, and less intense users stay with a transaction-based model.

Differentiating across User-based ModelsWith the user-based framework in place, we can start distinguishing between user-based companies. Using existing user value and new customer acquisition costs as the dimensions, we can derive a matrix of companies that go from user-value stars to user-value dogs.

While the combination of high user value with low user acquisition costs may sound like a pipe dream, it is what network benefits and big data, if they exist, promise to deliver. Network benefits refer to the possibility that as you grow bigger, it becomes easier for you to get even bigger, making it less costly to acquire new users. That is the promise of ride sharing, for instance, where as a company gets a larger share of a ride sharing market, both drivers and customers are more likely to switch to it, the former, because they get more customers and the latter, because they find rides more quickly.Big data, in a value framework, offers user-based companies an advantage, since what you learn about your users can be used to either sell them more products or services (if you are a transaction-based company), charge them higher premiums (if you are subscription-based) or direct advertising more effectively (if advertising-based). Many user-based companies aspire to have network benefits and to use data well, but only a few succeed.

The Pricing Game

As I look at user-based companies, some of which are being priced at billions of dollars, I am struck by how few of them are built to be long term businesses and how many of them are being priced on user numbers and buzz words. Using the framework from the last section, I would like to develop some common features that bad user-businesses seems to share in common and use one high profile examples, MoviePass , to make my case.

Mediocre User-based Companies

Given that so many young companies market themselves, based upon user and subscriber numbers, and that some of them can become valuable companies, are there signs that you can look for that separate the good from the mediocre companies? I think so, and here are a few red flags:

All about users, all the time: If the entire sales pitch that a company makes to investors is about its user or subscriber numbers, rather than its operating results (revenues and operating profits/losses), it is a dangerous sign. While large user numbers are a positive, it requires a business model to convert these users into revenues and profits, and that business model will not develop spontaneously. Companies that do not work on developing viable business models go bankrupt with lots of users.Opacity about user data: It is ironic that companies that market themselves to investors, based upon user numbers, are often opaque about key dimensions on users, including renewal (churn) rates, user behavior and side costs related to users. The companies that are most opaque are often the ones that have user models that are not sustainable.Bad business models: If having no business model to convert users to operating results is a bad sign, it is an even worse sign when you have a business model that is designed to deliver losses, not only in its current form, but with no light at the end of the tunnel. That is usually the consequence of having losses that scale up as the company gets bigger, because there are economies of scale. Loose talk about data: The fall back for many user based companies that cannot defend their business models is that they will find a way to use the data that they will collect from their users to make money in the future (from targeted advertising or additional products and services), without any serious attempt to explain why the data will give them an edge.And externalities: Many user based companies argue that their "innovative" twists on an existing business will both expand and alter the business, leading to benefits for other players in that business, who, in turn, will share their benefits with the user based companies.The bottom line is simple. It is easy to build user numbers, if you sell a product or service at way below cost, but if your objective is build a long-standing user-based companies, you need a pathway to profitability that is defined early and worked on continuously.

MoviePass: Too Good to be True? If you subscribe to MoviePass, for a monthly subscription of $10, you get to watch one theatrical movie, every day, for the entire month. Given that the average price of a theater ticket in the US is $9, this sounds like an insanely good deal, and for an avid movie goer, it is, and the service had two million subscribers in May 2018. MoviePass, though, pays the theaters for the tickets, creating a model that is more designed to drive it into bankruptcy than to deliver profits.

MoviePass EconomicsWhen confronted by the insanity of the business model, Mitch Lowe, the CEO of MoviePass, argued that after an initial burst, where subscribers would see four or five movies a month, they would settle into watching a movie a month, allowing the service to break even. Since Mr. Lowe is a co-founder of Netflix and a former CEO of Redbox, I will concede that he knows a lot more about the movie business than I do, but this is an absurd rationale. If the only way that your service can become viable is if people don't use it very much, it is not much of a service to begin with.

MoviePass EconomicsWhen confronted by the insanity of the business model, Mitch Lowe, the CEO of MoviePass, argued that after an initial burst, where subscribers would see four or five movies a month, they would settle into watching a movie a month, allowing the service to break even. Since Mr. Lowe is a co-founder of Netflix and a former CEO of Redbox, I will concede that he knows a lot more about the movie business than I do, but this is an absurd rationale. If the only way that your service can become viable is if people don't use it very much, it is not much of a service to begin with. In its early days, MoviePass seemed to be trying to build a viable business model, and acquired some high profile venture capital investors, but it was eventually acquired by Helios and Matheson, a data analytics firm, in a transaction in August 2017. It is Helios and Matheson, intent on giving both data and analysis a bad name, that instituted the $10 a month for a movie-a-day subscription. The subscription worked in delivering users but it, not surprisingly, came with large losses. As MoviePass has continued to burn cash (more than $20 million a month by April 2018), the share price of Helios and Matheson has collapsed, in a belated recognition of its non-viable business model.

Adding to the sense that no one in this company has a grip on reality, Ted Farnsworth, the CEO of Helios and Matheson, argued that the service would continue and had acquired a $300 million line of credit. Since his backing for this line of credit was that he could issue the remaining authorized shares at the current market price, this indicates either extreme ignorance (potential equity issues don't comprise a line of credit) or unalloyed deception, neither of which is a quality that builds trust. Along the way, there have been other attempts to rationalize the model, including the possibility of using the data collected from subscribers to target advertising and the sharing of additional revenues generated by theaters and studios from more movie going. There is nothing exclusive about the data that will be collected from MoviePass subscribers and it is unlikely that theaters and small studios, already on the brink financially, will be willing to share their revenues. In short, this is a bad business model hurtling to a bad end, and the only question is why it took so long.

The Bottom LineTo build a good user-based business, you have to start with the common sense recognition that users are not the end game, but a means to an end. Unfortunately, as long as venture capitalists and investors reward companies with high pricing, based just upon user count, we will encourage the building of bad businesses with lots of users and no pathways to becoming successful businesses.

YouTube Video

Paper on User Based Value

Going to Pieces: Valuing Users, Subscribers and CustomersBlog Posts on User-based Value

Valuing Uber RidersValuing Amazon Prime MembersValuing Spotify SubscribersValuing Netflix Subscribers

Published on May 29, 2018 11:56

May 22, 2018

Walmart's India (Flipkart) Gambit: Growth Rebirth or Costly Facelift?

On May 9, 2018, Walmart confirmed officially what had been rumored for weeks, and announced that it would pay $16 billion to acquire a 77% stake in Flipkart, an Indian online retail firm, translating into a valuation of more than $21 billion for a firm founded just over ten years ago, with about $10,000 in capital. Investors are debating the what, why and what next on this transaction, with their reactions showing up in a drop in Walmart’s market capitalization of approximately $8 billion. For Indian tech start-ups, the deal looks like the Nirvana that many of them aspire to reach, and this will undoubtedly affirm their hopes that if they build an India presence, there will be large players with deep pockets who will buy them out.

The Players

The place to start, when assessing a merger or an acquisition, is by looking at the companies involved, both acquiring and target, before the deal. It not only provides a baseline for any assessment of benefits, but may provide clues to motives.

a. Flipkart, an Amazon Wannabe?

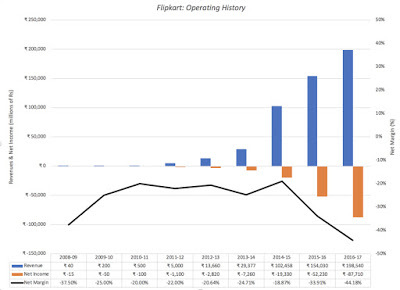

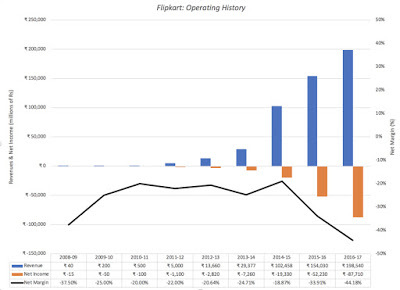

Of the two players in this deal, we know a lot less about Flipkart than we do about Walmart, because it is not publicly traded, and it provides only snippets of information about itself. That said, we can use that information to draw some conclusions about the company:It has grown quickly: Flipkart was founded in October 2007 by Sachin and Binny Bansal, both ex-Amazon employees and unrelated to each other, with about $6000 in seed capital. The revenues for the company increased from less than $1 million in 2008-09 to $75 million in 2011-12 and accelerated, with multiple acquisitions along the way, to reach $3 billion in 2016-2017. The revenue growth rate in 2016-17 was 29%, down from the 50% revenue growth recorded in the prior fiscal year. Flipkart’s revenues are shown, in Indian rupees, in the graph below: While losing lots of money and burning through cash: As the graph above, not surprisingly, show, Flipkart lost money in its early years, as growth was its priority. More troubling, though, is the fact that the company not only continues to lose money, but that its losses have scaled up with the revenues. In the 2016-17 fiscal year, for instance, the company reported an operating loss of $0.6 billion, giving it an operating margin of minus 40%. The continued losses have resulted in the company burning through much of the $7 billion it has raised in capital over its lifetime from investors. And borrowing money to plug cash flow deficits: Perhaps unwilling to dilute their ownership stake by further seeking equity capital, the founders have borrowed substantial amounts. The costs of financing this debt jumped to $671 million in the 2016-17 fiscal year, pushing overall losses to $1.3 billion. Not only are the finance costs adding to the losses and the cash burn each year, but they put the company’s survival, as a stand-alone company, at risk.It has had issues with governance and transparency along the way: Flipkart has a complex holding structure, with a parent company in Singapore and multiple off shoots, some designed to get around India’s byzantine restrictions on foreign investment and retailing and some reflecting their multiple forays raising venture capital.While the defense that will be offered for the company is that it is still young, the scale of the losses and the dependence on borrowed money would suggest that as a stand-alone business, you would be hard pressed to come up with a justification for a high value for the company and would have serious concerns about survival.

While losing lots of money and burning through cash: As the graph above, not surprisingly, show, Flipkart lost money in its early years, as growth was its priority. More troubling, though, is the fact that the company not only continues to lose money, but that its losses have scaled up with the revenues. In the 2016-17 fiscal year, for instance, the company reported an operating loss of $0.6 billion, giving it an operating margin of minus 40%. The continued losses have resulted in the company burning through much of the $7 billion it has raised in capital over its lifetime from investors. And borrowing money to plug cash flow deficits: Perhaps unwilling to dilute their ownership stake by further seeking equity capital, the founders have borrowed substantial amounts. The costs of financing this debt jumped to $671 million in the 2016-17 fiscal year, pushing overall losses to $1.3 billion. Not only are the finance costs adding to the losses and the cash burn each year, but they put the company’s survival, as a stand-alone company, at risk.It has had issues with governance and transparency along the way: Flipkart has a complex holding structure, with a parent company in Singapore and multiple off shoots, some designed to get around India’s byzantine restrictions on foreign investment and retailing and some reflecting their multiple forays raising venture capital.While the defense that will be offered for the company is that it is still young, the scale of the losses and the dependence on borrowed money would suggest that as a stand-alone business, you would be hard pressed to come up with a justification for a high value for the company and would have serious concerns about survival.

b. Walmart, Aging Giant?

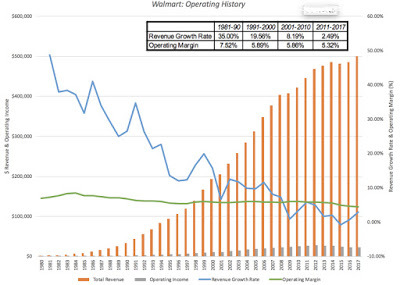

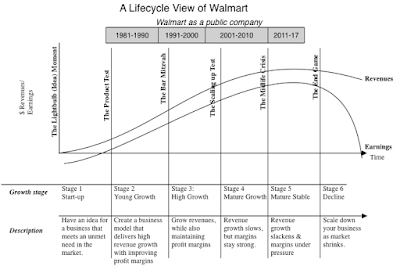

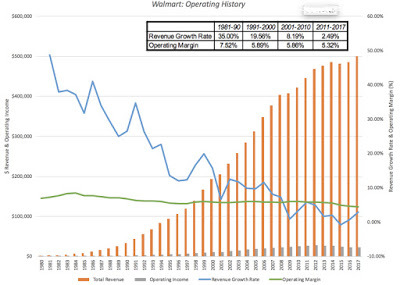

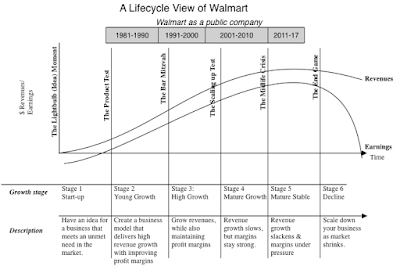

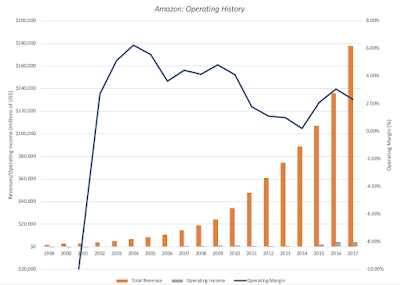

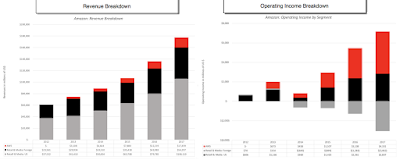

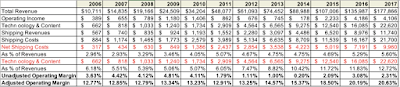

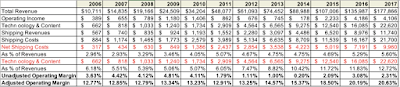

Walmart has been publicly traded for decades and its operating results can be seen in much more detail. Its growth in the 1980s and 1990s from an Arkansas big-box store to a dominant US retailer is captured below:

That operating history includes two decades of stellar growth towards the end of the twentieth century, where Walmart reshaped the retail business in the United States, and the years since, where growth has slowed down and margins have come under pressure. As Walmart stands now, here is what we see:

Growth has slowed to a trickle: Walmart’s growth engine started sputtering more than a decade ago, partly because its revenue base is so overwhelmingly large ($500 billion in 2017) and partly because of saturation in its primary market, which is the United States. And more of it is being acquired: As same store sales growth has leveled off, Walmart has been trying to acquire other companies, with Flipkart just being the most recent (and most expensive) example. But its base business remains big box retailing: While acquiring online retailers like Wayfair and upscale labels like Bonobos represent a change from its original mission, the company still is built around its original models of low price/ high volume and box stores. The margins in that business have been shrinking, albeit gradually, over time.And its global footprint is modest: For much of the last few years, Walmart has seen more than 20% of its revenues come from outside the United States, but that number has not increased over the last few years and a significant portion of the foreign sales come from Mexico and Canada. Looking at the data, it is difficult to see how you can come to any conclusion other than the one that Walmart is not just a mature company, but one that is perhaps on the verge of decline.

Very few companies age gracefully, with many fighting decline by trying desperately to reinvent themselves, entering new markets and businesses, and trying to acquire growth. A few do succeed and find a new lease on life. If you are a Walmart shareholder, your returns on the company over the next decade will be determined in large part by how it works through the aging process and the Flipkart acquisition is one of the strongest signals that the company does not plan to go into decline, without a fight. That may make for a good movie theme, but it can be very expensive for stockholders.

The Common Enemy

Looking at Flipkart and Walmart, it is clear that they are very different companies, at opposite ends of the life cycle. Flipkart is a young company, still struggling with its basic business model, that has proven successful at delivering revenue growth but not profits. Walmart is an aging giant, still profitable but with little growth and margins under pressure. There is one element that they share in common and that is that they are both facing off against perhaps the most feared company in the world, Amazon. a. Amazon versus Flipkart: Over the last few years, Amazon has aggressively pursued growth in India, conceding little to Flipkart, and shown a willingness to prioritize revenues (and market share) over profits: Source: Forrester (through Bloomberg Quint)While Flipkart remains the larger firm, Amazon India has continued to gain market share, almost catching up by April 2018, and more critically, it has contributed to Flipkart’s losses, by being willing to lose money itself. In a prior post, I called Amazon a Field of Dreams company, and argued that patience was built into its DNA and the end game, if Flipkart and Amazon India go head to head is foretold. Flipkart will fold, having run out of cash and capital.b. Amazon versus Walmart: If there is one company in the world that should know how Amazon operates, it has to be Walmart. Over the last twenty years, it has seen Amazon lay waste to the brick and mortar retail business in the United States and while the initial victims may have been department stores and specialty retailers, it is quite clear that Amazon is setting its sights on Walmart and Target, especially after its acquisition of Whole Foods.

Source: Forrester (through Bloomberg Quint)While Flipkart remains the larger firm, Amazon India has continued to gain market share, almost catching up by April 2018, and more critically, it has contributed to Flipkart’s losses, by being willing to lose money itself. In a prior post, I called Amazon a Field of Dreams company, and argued that patience was built into its DNA and the end game, if Flipkart and Amazon India go head to head is foretold. Flipkart will fold, having run out of cash and capital.b. Amazon versus Walmart: If there is one company in the world that should know how Amazon operates, it has to be Walmart. Over the last twenty years, it has seen Amazon lay waste to the brick and mortar retail business in the United States and while the initial victims may have been department stores and specialty retailers, it is quite clear that Amazon is setting its sights on Walmart and Target, especially after its acquisition of Whole Foods.

It may seem like hyperbole, but a strong argument can be made that while some of Flipkart and Walmart’s problems can be traced to management decision, scaling issues and customer tastes, it is the fear of Amazon that fills their waking moments and drives their decision making.

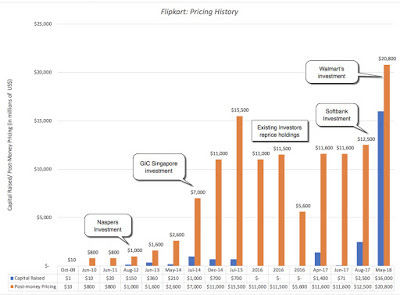

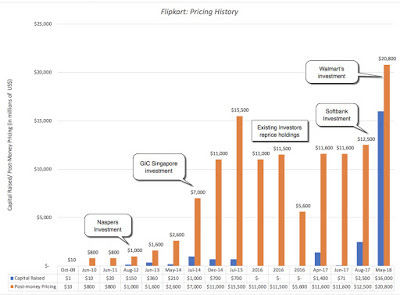

The Pricing of Flipkart

Walmart is just the latest in a series of high profile investors that Flipkart has attracted over the years. Tiger Global has made multiple investments in the company, starting in 2013, and other international investors have been part of subsequent rounds. The chart below captures the history: Barring a period between July 2015 and late 2016, where the company was priced down by existing investors, the pricing has risen, with each new capital raise. In April 2017, the company raised $1.4 billion from Microsoft, Tencent and EBay, in an investment round that priced the company at $11 billion, and in August 2017, Softbank invested $2.5 billion in the company, pricing it at closer to $12.5 billion. Walmart’s investment, though, represents a significant jump in the pricing over the last year.

Barring a period between July 2015 and late 2016, where the company was priced down by existing investors, the pricing has risen, with each new capital raise. In April 2017, the company raised $1.4 billion from Microsoft, Tencent and EBay, in an investment round that priced the company at $11 billion, and in August 2017, Softbank invested $2.5 billion in the company, pricing it at closer to $12.5 billion. Walmart’s investment, though, represents a significant jump in the pricing over the last year.

Note that, through this entire section, I have used the word “pricing” and not “valuation”, to describe these VC and private investments, and if you are wondering why, please read this post that I have on the difference between price and value, and why VCs play the pricing game. Why would these venture capitalists, many of whom are old hands at the game, push up the pricing for a company that has not only proved incapable of making money but where there is no light at the end of the tunnel? The answer is simple and cynical. The only justification needed in the pricing game is the expectation that someone will pay a higher price down the road, an expectation that is captured in the use of exit multiples in VC pricing models.

The Why?

So, why did Walmart pay $16 billion for a 70% stake in Flipkart? And will it pay off for the company? There are four possible explanations for the Walmart move and each comes with troubling after thoughts. 1. The Pricing Game: No matter what one thinks of Flipkart’s business model and its valuation, it is true, at least after the Walmart offer, that the game has paid off for earlier entrants. By paying what it did, Walmart has made every investor who entered the pricing chain at Flipkart before it a “success”, vindicating the pricing game, at least for them. If the essence of that game is that you buy at a low price and sell at a higher price, the payoff to playing the pricing game is easiest seen by looking at the Softbank investment made just nine months ago, which has almost doubled in pricing, largely as a consequence of the Walmart deal. In fact, many of the private equity and venture capital firms that became investors in earlier years will be selling their stakes to Walmart, ringing up huge capital gains and moving right along. Is it possible that Walmart is playing the pricing game as well, intending to sell Flipkart to someone else down the road at a higher price? My assessment: Since the company’s stake is overwhelming and it has operating motives, it is difficult to see how Walmart plays the pricing game, or at least plays it to win. There is some talk of investors forcing Walmart to take Flipkart public in a few years, and it is possible that if Walmart is able to bolster Flipkart and make it successful, this exit ramp could open up, but it seems like wishful thinking to me.

2. The Big Market Entrée (Real Options): The Indian retail market is a big one, but for decades it has also proved to be a frustrating one for companies that have tried to enter it for decades. One possible explanation for Walmart’s investment is that they are buying a (very expensive) option to enter a large and potentially lucrative market. The options argument would imply that Walmart can pay a premium over an assessed value for Flipkart, with that premium reflecting the uncertainty and size of the Indian retail market.

My assessment: The size of the Indian retail market, its potential growth and uncertainty about that growth create optionality, but given that Walmart remains a brick and mortar store primarily and that there is multiple paths that can be taken to be in that market, it is not clear that buying Flipkart is a valuable option.

3. Synergy: As with every merger, I am sure that the synergy word will be tossed around, often with wild abandon and generally with nothing to back it up. If the essence of synergy is that a merger will allow the combined entity to take actions (increase growth, lower costs etc.) that the individual entities could not have taken on their own, you would need to think of how acquiring Flipkart will allow Walmart to generate more revenues at its Indian retail stores and conversely, how allowing itself to be acquired by Walmart will make Flipkart grow faster and turn to profitability sooner.

My assessment: Walmart is not a large enough presence in India yet to benefit substantially from the Flipkart acquisition and while Walmart did announce that it would be opening 50 new stores in India, right after the Flipkart deal, I don’t see how owning Flipkart will increase traffic substantially at its brick and mortar stores. At the same time, Walmart has little to offer Flipkart to make it more competitive against Amazon, other than capital to keep it going. In summary, if there is synergy, you have to strain to see it, and it will not be substantial enough or come soon enough to justify the price paid for Flipkart.

4. Defensive Maneuver:Earlier, I noted that both Flipkart and Walmart share a common adversary, Amazon, a competitor masterful at playing the long game. I argued that there is little chance that Flipkart, standing alone, can survive this fight, as capital dries up and existing investors look for exits and that Walmart’s slide into decline in global retailing seems inexorable, as Amazon continues its rise. Given that the Chinese retail market will prove difficult to penetrate, the Indian retail market may be where Walmart makes its stand. Put differently, Walmart’s justification for investing in Flipkart is not they expect to generate a reasonable return on their $16 billion investment but that if they do not make this acquisition, Amazon will be unchecked and that their decline will be more precipitous.

My assessment: Of the four reasons, this, in my view, is the one that best explains the deal. Defensive mergers, though, are a sign of weakness, not strength, and point to a business model under stress. If you are a Walmart shareholder, this is a negative signal and it does not surprise me that Walmart shares have declined in the aftermath. Staying with the life cycle analogy, Walmart is an aging, once-beautiful actress that has paid $16 billion for a very expensive face lift, and like all face lifts, it is only a matter of time before gravity works its magic again.

In summary, I think that the odds are against Walmart on this deal, given what it paid for Flipkart. If the rumors are true that Amazon was interested in buying Flipkart for close to $22 billion, I think that Walmart would have been better served letting Amazon win this battle and fight the local anti-trust enforcers, while playing to its strengths in brick and mortar retailing. I have a sneaking suspicion that Amazon had no intent of ever buying Flipkart and that it has succeeded in goading Walmart into paying way more than it should have to enter the Indian online retail space, where it can expect to lose money for the foreseeable future. Sometimes, you win bidding wars by losing them!

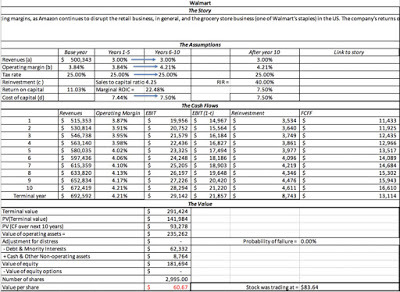

What next?

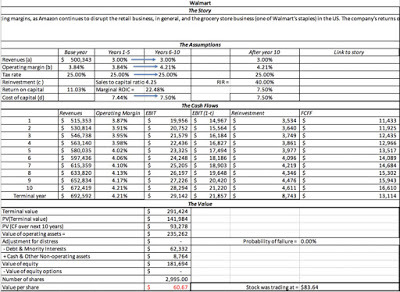

In the long term, this deal may slow the decline at Walmart, but at a price so high, that I don’t see how Walmart’s shareholders benefit from it. I have attached my valuation of Walmart and with my story of continued slow growth and stagnant margins for the company, the value that I obtain for the company is about $61, about 25% below its stock price of $83.64 on May 18, 2018.

Download spreadsheetIn the short term, I expect this acquisition to a accelerate the already frenetic competition in the Indian retail market, with Flipkart, now backed by Walmart cash, and Amazon India continuing to cut prices and offering supplementary services. That will mean even bigger losses at both firms, and smaller online retailers will fall to the wayside. The winners, though, will be Indian retail customers who, in the words of the Godfather, will be made offers that they cannot refuse!

Download spreadsheetIn the short term, I expect this acquisition to a accelerate the already frenetic competition in the Indian retail market, with Flipkart, now backed by Walmart cash, and Amazon India continuing to cut prices and offering supplementary services. That will mean even bigger losses at both firms, and smaller online retailers will fall to the wayside. The winners, though, will be Indian retail customers who, in the words of the Godfather, will be made offers that they cannot refuse!

For start-ups all over India, though, I am afraid that this deal, which rewards the founders of Flipkart and its VC investors for building a money-losing, cash-burning machine, will feed bad behavior. Young companies will go for growth, and still more growth, paying little attention to pathways to profitability or building viable businesses, hoping to be Flipkarted. Venture capitalists will play more pricing games, paying prices for these money losers that have no basis in fundamentals, but justifying them by arguing that they will be Walmarted. In the meantime, if you are an investor who cares about value, I would suggest that you buy some popcorn, and enjoy the entertainment. It will be fun, while it lasts!

YouTube Video

Data Links

Walmart Valuation - May 2018

The Players

The place to start, when assessing a merger or an acquisition, is by looking at the companies involved, both acquiring and target, before the deal. It not only provides a baseline for any assessment of benefits, but may provide clues to motives.

a. Flipkart, an Amazon Wannabe?

Of the two players in this deal, we know a lot less about Flipkart than we do about Walmart, because it is not publicly traded, and it provides only snippets of information about itself. That said, we can use that information to draw some conclusions about the company:It has grown quickly: Flipkart was founded in October 2007 by Sachin and Binny Bansal, both ex-Amazon employees and unrelated to each other, with about $6000 in seed capital. The revenues for the company increased from less than $1 million in 2008-09 to $75 million in 2011-12 and accelerated, with multiple acquisitions along the way, to reach $3 billion in 2016-2017. The revenue growth rate in 2016-17 was 29%, down from the 50% revenue growth recorded in the prior fiscal year. Flipkart’s revenues are shown, in Indian rupees, in the graph below:

While losing lots of money and burning through cash: As the graph above, not surprisingly, show, Flipkart lost money in its early years, as growth was its priority. More troubling, though, is the fact that the company not only continues to lose money, but that its losses have scaled up with the revenues. In the 2016-17 fiscal year, for instance, the company reported an operating loss of $0.6 billion, giving it an operating margin of minus 40%. The continued losses have resulted in the company burning through much of the $7 billion it has raised in capital over its lifetime from investors. And borrowing money to plug cash flow deficits: Perhaps unwilling to dilute their ownership stake by further seeking equity capital, the founders have borrowed substantial amounts. The costs of financing this debt jumped to $671 million in the 2016-17 fiscal year, pushing overall losses to $1.3 billion. Not only are the finance costs adding to the losses and the cash burn each year, but they put the company’s survival, as a stand-alone company, at risk.It has had issues with governance and transparency along the way: Flipkart has a complex holding structure, with a parent company in Singapore and multiple off shoots, some designed to get around India’s byzantine restrictions on foreign investment and retailing and some reflecting their multiple forays raising venture capital.While the defense that will be offered for the company is that it is still young, the scale of the losses and the dependence on borrowed money would suggest that as a stand-alone business, you would be hard pressed to come up with a justification for a high value for the company and would have serious concerns about survival.

While losing lots of money and burning through cash: As the graph above, not surprisingly, show, Flipkart lost money in its early years, as growth was its priority. More troubling, though, is the fact that the company not only continues to lose money, but that its losses have scaled up with the revenues. In the 2016-17 fiscal year, for instance, the company reported an operating loss of $0.6 billion, giving it an operating margin of minus 40%. The continued losses have resulted in the company burning through much of the $7 billion it has raised in capital over its lifetime from investors. And borrowing money to plug cash flow deficits: Perhaps unwilling to dilute their ownership stake by further seeking equity capital, the founders have borrowed substantial amounts. The costs of financing this debt jumped to $671 million in the 2016-17 fiscal year, pushing overall losses to $1.3 billion. Not only are the finance costs adding to the losses and the cash burn each year, but they put the company’s survival, as a stand-alone company, at risk.It has had issues with governance and transparency along the way: Flipkart has a complex holding structure, with a parent company in Singapore and multiple off shoots, some designed to get around India’s byzantine restrictions on foreign investment and retailing and some reflecting their multiple forays raising venture capital.While the defense that will be offered for the company is that it is still young, the scale of the losses and the dependence on borrowed money would suggest that as a stand-alone business, you would be hard pressed to come up with a justification for a high value for the company and would have serious concerns about survival. b. Walmart, Aging Giant?

Walmart has been publicly traded for decades and its operating results can be seen in much more detail. Its growth in the 1980s and 1990s from an Arkansas big-box store to a dominant US retailer is captured below:

That operating history includes two decades of stellar growth towards the end of the twentieth century, where Walmart reshaped the retail business in the United States, and the years since, where growth has slowed down and margins have come under pressure. As Walmart stands now, here is what we see:

Growth has slowed to a trickle: Walmart’s growth engine started sputtering more than a decade ago, partly because its revenue base is so overwhelmingly large ($500 billion in 2017) and partly because of saturation in its primary market, which is the United States. And more of it is being acquired: As same store sales growth has leveled off, Walmart has been trying to acquire other companies, with Flipkart just being the most recent (and most expensive) example. But its base business remains big box retailing: While acquiring online retailers like Wayfair and upscale labels like Bonobos represent a change from its original mission, the company still is built around its original models of low price/ high volume and box stores. The margins in that business have been shrinking, albeit gradually, over time.And its global footprint is modest: For much of the last few years, Walmart has seen more than 20% of its revenues come from outside the United States, but that number has not increased over the last few years and a significant portion of the foreign sales come from Mexico and Canada. Looking at the data, it is difficult to see how you can come to any conclusion other than the one that Walmart is not just a mature company, but one that is perhaps on the verge of decline.

Very few companies age gracefully, with many fighting decline by trying desperately to reinvent themselves, entering new markets and businesses, and trying to acquire growth. A few do succeed and find a new lease on life. If you are a Walmart shareholder, your returns on the company over the next decade will be determined in large part by how it works through the aging process and the Flipkart acquisition is one of the strongest signals that the company does not plan to go into decline, without a fight. That may make for a good movie theme, but it can be very expensive for stockholders.

The Common Enemy

Looking at Flipkart and Walmart, it is clear that they are very different companies, at opposite ends of the life cycle. Flipkart is a young company, still struggling with its basic business model, that has proven successful at delivering revenue growth but not profits. Walmart is an aging giant, still profitable but with little growth and margins under pressure. There is one element that they share in common and that is that they are both facing off against perhaps the most feared company in the world, Amazon. a. Amazon versus Flipkart: Over the last few years, Amazon has aggressively pursued growth in India, conceding little to Flipkart, and shown a willingness to prioritize revenues (and market share) over profits:

Source: Forrester (through Bloomberg Quint)While Flipkart remains the larger firm, Amazon India has continued to gain market share, almost catching up by April 2018, and more critically, it has contributed to Flipkart’s losses, by being willing to lose money itself. In a prior post, I called Amazon a Field of Dreams company, and argued that patience was built into its DNA and the end game, if Flipkart and Amazon India go head to head is foretold. Flipkart will fold, having run out of cash and capital.b. Amazon versus Walmart: If there is one company in the world that should know how Amazon operates, it has to be Walmart. Over the last twenty years, it has seen Amazon lay waste to the brick and mortar retail business in the United States and while the initial victims may have been department stores and specialty retailers, it is quite clear that Amazon is setting its sights on Walmart and Target, especially after its acquisition of Whole Foods.

Source: Forrester (through Bloomberg Quint)While Flipkart remains the larger firm, Amazon India has continued to gain market share, almost catching up by April 2018, and more critically, it has contributed to Flipkart’s losses, by being willing to lose money itself. In a prior post, I called Amazon a Field of Dreams company, and argued that patience was built into its DNA and the end game, if Flipkart and Amazon India go head to head is foretold. Flipkart will fold, having run out of cash and capital.b. Amazon versus Walmart: If there is one company in the world that should know how Amazon operates, it has to be Walmart. Over the last twenty years, it has seen Amazon lay waste to the brick and mortar retail business in the United States and while the initial victims may have been department stores and specialty retailers, it is quite clear that Amazon is setting its sights on Walmart and Target, especially after its acquisition of Whole Foods. It may seem like hyperbole, but a strong argument can be made that while some of Flipkart and Walmart’s problems can be traced to management decision, scaling issues and customer tastes, it is the fear of Amazon that fills their waking moments and drives their decision making.

The Pricing of Flipkart

Walmart is just the latest in a series of high profile investors that Flipkart has attracted over the years. Tiger Global has made multiple investments in the company, starting in 2013, and other international investors have been part of subsequent rounds. The chart below captures the history:

Barring a period between July 2015 and late 2016, where the company was priced down by existing investors, the pricing has risen, with each new capital raise. In April 2017, the company raised $1.4 billion from Microsoft, Tencent and EBay, in an investment round that priced the company at $11 billion, and in August 2017, Softbank invested $2.5 billion in the company, pricing it at closer to $12.5 billion. Walmart’s investment, though, represents a significant jump in the pricing over the last year.

Barring a period between July 2015 and late 2016, where the company was priced down by existing investors, the pricing has risen, with each new capital raise. In April 2017, the company raised $1.4 billion from Microsoft, Tencent and EBay, in an investment round that priced the company at $11 billion, and in August 2017, Softbank invested $2.5 billion in the company, pricing it at closer to $12.5 billion. Walmart’s investment, though, represents a significant jump in the pricing over the last year. Note that, through this entire section, I have used the word “pricing” and not “valuation”, to describe these VC and private investments, and if you are wondering why, please read this post that I have on the difference between price and value, and why VCs play the pricing game. Why would these venture capitalists, many of whom are old hands at the game, push up the pricing for a company that has not only proved incapable of making money but where there is no light at the end of the tunnel? The answer is simple and cynical. The only justification needed in the pricing game is the expectation that someone will pay a higher price down the road, an expectation that is captured in the use of exit multiples in VC pricing models.

The Why?

So, why did Walmart pay $16 billion for a 70% stake in Flipkart? And will it pay off for the company? There are four possible explanations for the Walmart move and each comes with troubling after thoughts. 1. The Pricing Game: No matter what one thinks of Flipkart’s business model and its valuation, it is true, at least after the Walmart offer, that the game has paid off for earlier entrants. By paying what it did, Walmart has made every investor who entered the pricing chain at Flipkart before it a “success”, vindicating the pricing game, at least for them. If the essence of that game is that you buy at a low price and sell at a higher price, the payoff to playing the pricing game is easiest seen by looking at the Softbank investment made just nine months ago, which has almost doubled in pricing, largely as a consequence of the Walmart deal. In fact, many of the private equity and venture capital firms that became investors in earlier years will be selling their stakes to Walmart, ringing up huge capital gains and moving right along. Is it possible that Walmart is playing the pricing game as well, intending to sell Flipkart to someone else down the road at a higher price? My assessment: Since the company’s stake is overwhelming and it has operating motives, it is difficult to see how Walmart plays the pricing game, or at least plays it to win. There is some talk of investors forcing Walmart to take Flipkart public in a few years, and it is possible that if Walmart is able to bolster Flipkart and make it successful, this exit ramp could open up, but it seems like wishful thinking to me.

2. The Big Market Entrée (Real Options): The Indian retail market is a big one, but for decades it has also proved to be a frustrating one for companies that have tried to enter it for decades. One possible explanation for Walmart’s investment is that they are buying a (very expensive) option to enter a large and potentially lucrative market. The options argument would imply that Walmart can pay a premium over an assessed value for Flipkart, with that premium reflecting the uncertainty and size of the Indian retail market.

My assessment: The size of the Indian retail market, its potential growth and uncertainty about that growth create optionality, but given that Walmart remains a brick and mortar store primarily and that there is multiple paths that can be taken to be in that market, it is not clear that buying Flipkart is a valuable option.

3. Synergy: As with every merger, I am sure that the synergy word will be tossed around, often with wild abandon and generally with nothing to back it up. If the essence of synergy is that a merger will allow the combined entity to take actions (increase growth, lower costs etc.) that the individual entities could not have taken on their own, you would need to think of how acquiring Flipkart will allow Walmart to generate more revenues at its Indian retail stores and conversely, how allowing itself to be acquired by Walmart will make Flipkart grow faster and turn to profitability sooner.

My assessment: Walmart is not a large enough presence in India yet to benefit substantially from the Flipkart acquisition and while Walmart did announce that it would be opening 50 new stores in India, right after the Flipkart deal, I don’t see how owning Flipkart will increase traffic substantially at its brick and mortar stores. At the same time, Walmart has little to offer Flipkart to make it more competitive against Amazon, other than capital to keep it going. In summary, if there is synergy, you have to strain to see it, and it will not be substantial enough or come soon enough to justify the price paid for Flipkart.

4. Defensive Maneuver:Earlier, I noted that both Flipkart and Walmart share a common adversary, Amazon, a competitor masterful at playing the long game. I argued that there is little chance that Flipkart, standing alone, can survive this fight, as capital dries up and existing investors look for exits and that Walmart’s slide into decline in global retailing seems inexorable, as Amazon continues its rise. Given that the Chinese retail market will prove difficult to penetrate, the Indian retail market may be where Walmart makes its stand. Put differently, Walmart’s justification for investing in Flipkart is not they expect to generate a reasonable return on their $16 billion investment but that if they do not make this acquisition, Amazon will be unchecked and that their decline will be more precipitous.

My assessment: Of the four reasons, this, in my view, is the one that best explains the deal. Defensive mergers, though, are a sign of weakness, not strength, and point to a business model under stress. If you are a Walmart shareholder, this is a negative signal and it does not surprise me that Walmart shares have declined in the aftermath. Staying with the life cycle analogy, Walmart is an aging, once-beautiful actress that has paid $16 billion for a very expensive face lift, and like all face lifts, it is only a matter of time before gravity works its magic again.

In summary, I think that the odds are against Walmart on this deal, given what it paid for Flipkart. If the rumors are true that Amazon was interested in buying Flipkart for close to $22 billion, I think that Walmart would have been better served letting Amazon win this battle and fight the local anti-trust enforcers, while playing to its strengths in brick and mortar retailing. I have a sneaking suspicion that Amazon had no intent of ever buying Flipkart and that it has succeeded in goading Walmart into paying way more than it should have to enter the Indian online retail space, where it can expect to lose money for the foreseeable future. Sometimes, you win bidding wars by losing them!

What next?

In the long term, this deal may slow the decline at Walmart, but at a price so high, that I don’t see how Walmart’s shareholders benefit from it. I have attached my valuation of Walmart and with my story of continued slow growth and stagnant margins for the company, the value that I obtain for the company is about $61, about 25% below its stock price of $83.64 on May 18, 2018.

Download spreadsheetIn the short term, I expect this acquisition to a accelerate the already frenetic competition in the Indian retail market, with Flipkart, now backed by Walmart cash, and Amazon India continuing to cut prices and offering supplementary services. That will mean even bigger losses at both firms, and smaller online retailers will fall to the wayside. The winners, though, will be Indian retail customers who, in the words of the Godfather, will be made offers that they cannot refuse!

Download spreadsheetIn the short term, I expect this acquisition to a accelerate the already frenetic competition in the Indian retail market, with Flipkart, now backed by Walmart cash, and Amazon India continuing to cut prices and offering supplementary services. That will mean even bigger losses at both firms, and smaller online retailers will fall to the wayside. The winners, though, will be Indian retail customers who, in the words of the Godfather, will be made offers that they cannot refuse! For start-ups all over India, though, I am afraid that this deal, which rewards the founders of Flipkart and its VC investors for building a money-losing, cash-burning machine, will feed bad behavior. Young companies will go for growth, and still more growth, paying little attention to pathways to profitability or building viable businesses, hoping to be Flipkarted. Venture capitalists will play more pricing games, paying prices for these money losers that have no basis in fundamentals, but justifying them by arguing that they will be Walmarted. In the meantime, if you are an investor who cares about value, I would suggest that you buy some popcorn, and enjoy the entertainment. It will be fun, while it lasts!

YouTube Video

Data Links

Walmart Valuation - May 2018

Published on May 22, 2018 11:21

April 26, 2018

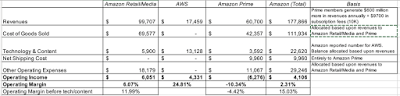

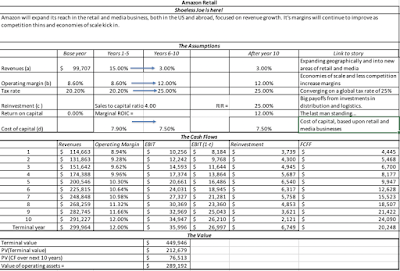

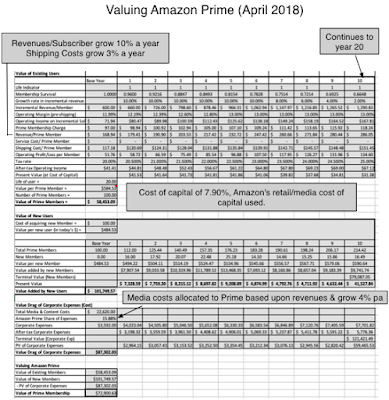

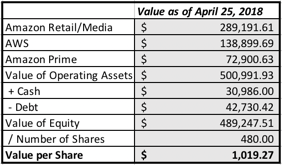

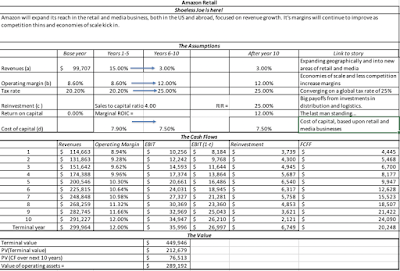

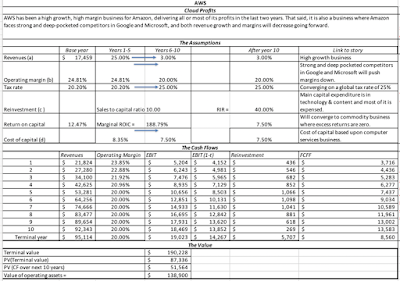

Amazon: Glimpses of Shoeless Joe?

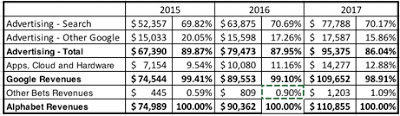

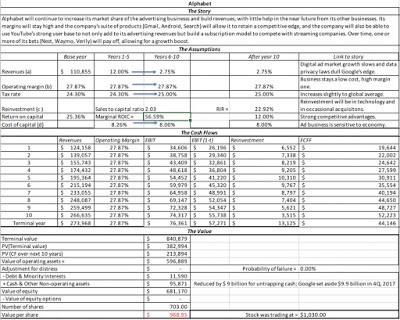

It was just over two weeks ago that I started my posts on the FANG stocks, starting with Facebook, which I decided to buy, because I felt that notwithstanding its current pariah status, its user base was too valuable to pass by, at the prevailing market price. I then looked at Netflix, a company that has shown a remarkable ability to adapt to the challenges thrown at it, while changing the entertainment business, but is, at least in my view, in a content cost/user cycle that will be difficult to break out of. With Alphabet, the cash cow that is its advertising business is allowing it to invest in the big new markets of tomorrow, and even with low odds and very little substance today, these bets can make or break the investment. That leaves me with the longest listed and perhaps the most intriguing of the four stocks, Amazon, a company whose reach seems to expand into new markets each year.

Revisiting my Amazon past

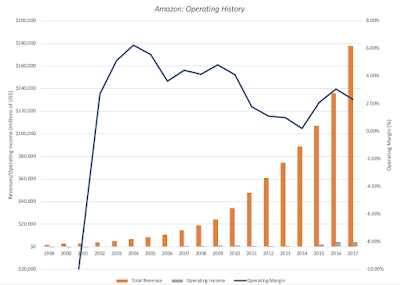

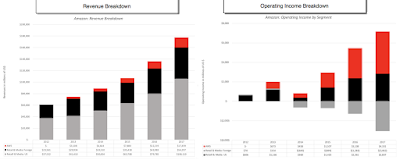

I valued Amazon for the first time in 1998, as an online book retailer, and much of what I know about valuing young companies today came from the struggles I went through, modifying what I knew in conventional valuation, for the special challenges of valuing a company with no history, no financials and no peer group. Out of that experience was born a paper on valuing young companies, which is still on my website and the first edition of the Dark Side of Valuation, and if you want to see some horrendously wrong forecasts, at least in hindsight, you can check out my valuation of Amazon in that edition.

While I had a tough time justifying Amazon’s valuation, in its dot-com days, I always admired the company and the way it was managed. When I was put off balance by an Amazon product, service or corporate announcement, I re-read Jeff Bezos’ letter to Amazon shareholders from 1997, because it helped me understand (though not always agree with) how Amazon views the business world. In that letter, Bezos laid out what I called the Field of Dreams story, telling his stockholders that if Amazon built it (revenues), they (the profits and cash flows) would come. In all my years looking at companies, I have never seen a CEO stay so true to a narrative and act as consistently as Amazon has, and it is, in my view, the biggest reason for its market success.

I have valued Amazon about once a year every year over its existence, and I have bought Amazon four times and sold it four times in that period. That said, there are two confessions that I have to make. The first is that I have not owned Amazon since 2012, and have thus missed out on its bull run since then. Second, through all of this time, I have consistently under estimated not only the innovative genius of this company, but also its (and its investors') patience. In fact, there have been occasions when I have wondered, staying true to my Field of Dreams theme, whether Shoeless Joe would ever make his appearance.

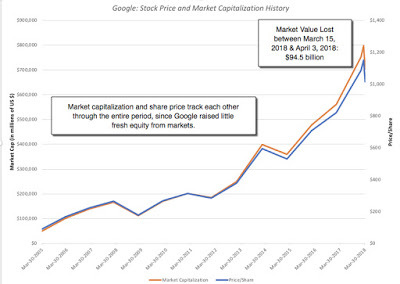

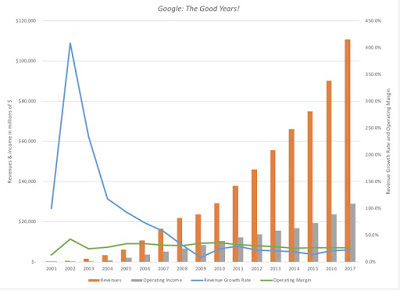

Amazon’s Market Cap Rise

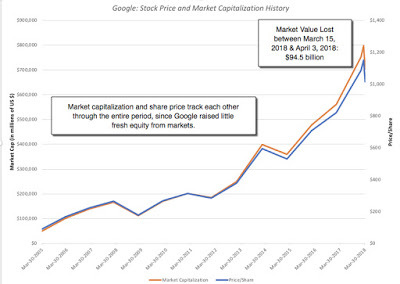

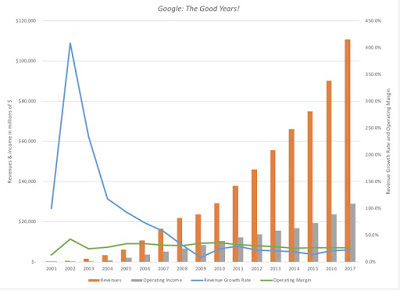

Amazon’s rise in market capitalization has had more ups and downs than either Google or Facebook, but it has been just as impressive, partly because the company came back from a near death experience after the dot-com bust in 2001.

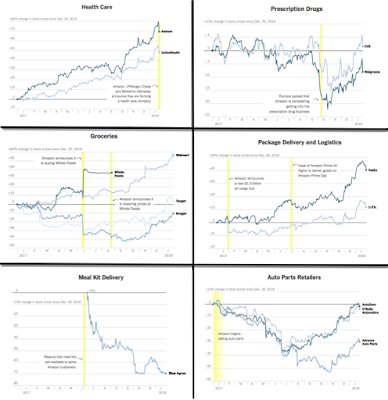

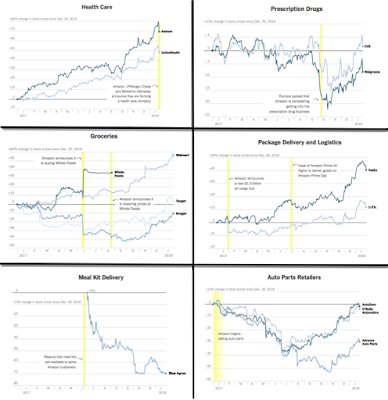

The more remarkable feature of Amazon’s rise has been the debris it has left in its wake, first with brick and mortar retail in the United States, but more recently in almost every business it has entered, from grocery retail to logistics. These graphs, excerpted from a New York Times article earlier this year, tells the story: