Dimitrios Konidaris's Blog, page 7

June 27, 2022

BRONZE AGE FRAGMENTAL PIECES OF EVIDENCE IN HOMER ..

War of Troy, from Vergilius Romanus

War of Troy, from Vergilius RomanusÎεÏÏείÏαι[0] ÏÎ¿Î»Ï ÏιθανÏν ÏÏι η Îλιάδα και η ÎδÏÏÏεια ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏÎθηÏαν ÏÏοÏοÏικά ÏÏοκειμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î½Î± άδονÏαι ενÏÏιον Ïοι ÎºÎ¿Î¹Î½Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹, με βάÏη Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην ÏαÏάÏÏαÏη, καÏαγÏάÏηκαν με Ï ÏαγÏÏÎµÏ Ïη καÏά Ïο δεÏÏεÏο ήμιÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï 8Î¿Ï Î±Î¹. Ï.Χ. ΣÏμÏÏνα με οÏιÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï Ï ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏείÏ, οι ΠειÏιÏÏÏαδίδεÏ, ÏÏÏαννοι ÏÎ·Ï ÎθήναÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÏ Î²ÎÏνηÏαν Ïην ÏÏλη αÏÏ Ïο 560 ÎÏÏ Ïο 510 Ï.Χ., ÎÏαιξαν ÏημανÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏλο ÏÏον καθοÏιÏÎ¼Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¿ÏγανÏÏεÏÏ ÏÏν βιβλίÏν Ïε κάθε ÎÏοÏ. ΣÏην ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα, Ïο ÏÏνολο ÏÏν ÎºÏ Î»Î¯Î½Î´ÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏήÏθηÏαν καÏά Ïη βαÏιλεία ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±ÏεÏÎλεÏε Ïην βάÏη γιά Ïην ÏαÏάδοÏη ÏειÏογÏάÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î®Ïαν γνÏÏÏή ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎλεξανδÏινοÏÏ Î¼ÎµÎ»ÎµÏηÏÎÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïον ÏÏίÏο αιÏνα Ï.Χ. και μεÏά. ÎÎ½Ï Î¿Î¹ ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏÎµÎ¯Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎμÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î¹Ïνα αναÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïα ÎμηÏικά ÏοιήμαÏα ÏÏ Î®Î´Î· καθιεÏÏμÎνα ÎÏγα, Ïα ÏαλαιÏÏεÏα ÏÏζÏμενα θÏαÏÏμαÏα ÏÏν ÏοιημάÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Î»ÏÏθηκαν ÏÏην ÎÎ¯Î³Ï ÏÏο ÏÏονολογοÏνÏαι αÏÏ Ïον ÏÏίÏο αιÏνα Ï.Χ. Îενικά, ο αÏιθμÏÏ ÏÏν ÎμηÏικÏν ÏαÏÏÏÏν είναι ενÏÏ ÏÏÏιακÏÏ, εÏιβεβαιÏνονÏÎ±Ï Ïην ÏÏ Î½ÏÏιÏÏική ÏαÏÎ¿Ï Ïία ÏÏν ÏοιημάÏÏν ÏÏην εκÏÎ±Î¯Î´ÎµÏ Ïη και Ïη λογοÏεÏνική ÎºÎ¿Ï Î»ÏοÏÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï ÎºÏÏÎ¼Î¿Ï . ÎÏιÏλÎον, ο ÎμηÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Ïνά ξεÏεÏνοÏÏε Ïα ÏÏια ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ Î¼Î²Î±ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÎºÏαιδεÏÏεÏÏ Î³Î¹Î± να ειÏÎλθει ÏÏο βαÏίλειο ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸Î·Î¼ÎµÏÎ¹Î½Î®Ï Î¶ÏήÏ, ÏÏÏÏ ÏÏο ÏαÏÎ¹Î´Î¹ÎºÏ ÎµÎ³ÏειÏίδιο ÏελεÏÎ¿Ï ÏγικÏν ξοÏκιÏν για ιαÏÏικά ÏÏοβλήμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεÏιγÏάÏονÏαι ÏαÏακάÏÏ, ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÎµÏικÎÏ Î³ÏαμμÎÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïην Îλιάδα Îμειναν αμεÏάÏÏαÏÏεÏ. ÎÏÏÏ Î¼Î¬Î»Î¹ÏÏα ο αναγνÏÏÏÎ·Ï Î½Î± γνÏÏιÏε μια ιδιαίÏεÏη θεÏαÏεία ÏÏοÏÎÏονÏÎ±Ï Ïα ελληνικά ÏÏο ÏÏÏÏÏÏÏ Ïο.ÎαÏÎ¬Î»Î¿Î³Î¿Ï ÏÏν νηÏν & αÏάλανÏοÏΣε άÏθÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ Calverts Watkins εÏιÏειÏεί να ÏÏÏίÏει γλÏÏÏολογικά και αÏÏαιολογικά οÏιÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Ï ÎμηÏικοÏÏ ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï.[1] ÎναÏεÏÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï Î»Î¿Î¹ÏÏν ÏÏο αÏÏÏÏαÏμα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎαÏαλÏÎ³Î¿Ï ÏÏν ÎηÏν Ïο ÏÏεÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î¼Îµ Ïην ÎÏήÏη, Il.2.654-651, διαÏιÏÏÏνει αÏÏικά ÏÏι η ÏÏάÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεÏιγÏάÏει Ïον ÎηÏιÏνη ÏÏÎÏει για γλÏÏÏικοÏÏ Î»ÏÎ³Î¿Ï Ï Î½Î± ÏÏονολογείÏαι Ïο αÏγÏÏεÏο μÎÏÏι Ïην ΥΠIIIa. Το αÏÏαÏÎºÏ ÎµÏίθεÏο á¼ÏάλανÏοÏ[2] αναÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏ ÏεÏαιÏÎÏÏ Î±ÏÏδειξη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î·Ï ÏÏÎ¿Î½Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏοÏÏάÏμαÏοÏ: ÏÏοÏανÏÏ Î¿Î¹ Î¶Ï Î³Î¿Î¯ ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιήθηκαν μÏνον ÏÏ ÏαÏικά ανÏικείμενα για μια ÏÏνÏομη ÏεÏίοδο ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î ÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î¿Ï Ï ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±ÏκοÏÏ ÏÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï Ï, ÏÏιν αÏÏ Ïο 1400 Ï.Χ. ÎεβαίÏÏ Î¿Î¹ Î¶Ï Î³Î¿Î¯ ÏεÏιλαμβάνονÏαι μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÏν ÏÏ Î»Î»Î±Î²Î¿Î³ÏαμμάÏÏν αμÏοÏÎÏÏν ÏÏν ÎÏαμμικÏν ÎÏαÏÏν. ΣÏο ίδιο αÏÏÏÏαÏμα αÏÏ Ïην Îλιάδα, ÏÏÏον η ÎνÏÏÏÏ ÏÏο και η ÎÏÏÏÏ Î½Î± αναÏÎÏονÏαι ÏÏ Î±Î½Î®ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÏ ÏÏην ηγεμονία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎδομενÎÏÏ. ÎεδομÎÎ½Î¿Ï ÏÏι ο αÏÏαιÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¹ÏμÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÏÏÏ Î½Î¿Ï ÏÏονολογείÏαι ÏÏην ΥΠIIIb2, οι δÏο ÏÏÎ»ÎµÎ¹Ï Î¸Î± μÏοÏοÏÏαν να Ï ÏάÏÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÏÏονα μÏνο εάν γίνει δεκÏή η ÏÏιμη ημεÏομηνία ÏÏονολογήÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Palmer για Ïην καÏαÏÏÏοÏή ÏÎ·Ï ÎνÏÏοÏ, ήÏοι η ΥΠIIIb, ÏεÏί Ïο 1225 Ï.Χ.

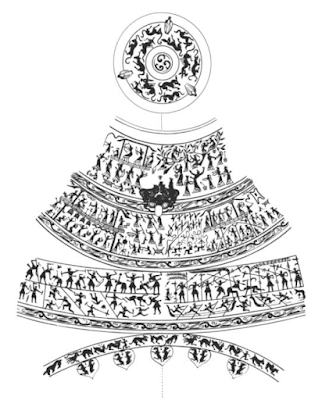

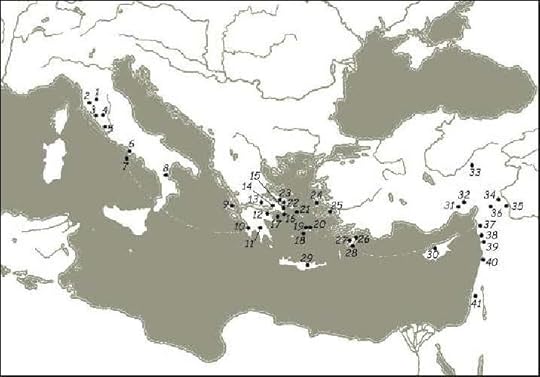

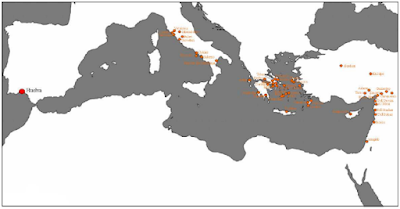

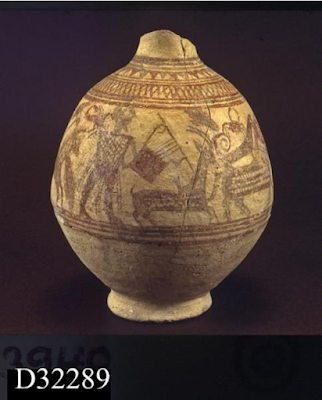

ΠμικÏογÏαÏική ζÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎήÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ η εÏική ÏοίηÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï[4]AÏÏ Ïην Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ¬Î»Ï Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Ïο 1972 οι μικÏογÏαÏικÎÏ ÏοιÏογÏαÏÎ¯ÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎÎ¹ÎºÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎκÏÏÏηÏÎ¯Î¿Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏαβήξει Ïο ενδιαÏÎÏον ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ¿Î¹Î½ÏÏηÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ½ÏÏÏ ÏÏν οÏίÏν ÏÏν ÏÏ Î³ÏÏονικÏν και ÏεÏνικÏν μελεÏÏν ÏÏν αÏÏαιολÏγÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎινÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏολιÏιÏμοÏ. Îι μελεÏηÏÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏοÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ αÏκήÏει Ïην ειδικÏÏηÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÏί ÏÏν ÏοιÏογÏαÏιÏν, ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίξει Ïην Îιγαιακή ÏεÏιοÏή ενδιαÏÎÏονÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Ïά ÏÏοβλÎÏιμο ÏÏÏÏο και ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ διεÏÎµÏ Î½Î®Ïει μοÏÏολογικÎÏ ÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎμαÏοÏ. ΠμελÎÏη αÏÏ Ïην εÏιÏÏημονική κοινÏÏηÏα ÎÏει ÏαÏαμείνει ÏιÏÏή ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÏαλαιÏÏεÏÎµÏ ÎµÏμηνείεÏ, ÏαÏά Ïα νÎα ÏÏοιÏεία εκÏÏÏ ÎήÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸ÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ¹Ï Î½ÎÎµÏ Î±ÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏεÏικÎÏ Î¼Îµ Ïην ÎÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï. ÎÏ ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏει Ïαθεί είναι η ενÏÏηÏα και η ÎµÏ ÏÏÏεÏη ÏημαÏία â ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î±Î¹ÏÏηÏα Î±Ï ÏÏν ÏÏν ÏοιÏογÏαÏιÏν. Î ÏÏÏÏαÏÏική Ïηγή ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ÎÎ½Î±Ï ÎµÏικÏÏ Î® ηÏÏικÏÏ Î¼ÎµÏαÏÏημαÏιÏμÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÎ¼ÏειÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î¿ οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏάγεÏαι / Ï ÏαινίÏÏεÏαι} Ïην ÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÏÏονη ÏÏαÏξη ÏοιήÏεÏÏ. Îία ÏÏγκÏιÏη ÏÏν οÏÏικÏν εικÏνÏν με ÏοιηÏικά θÎμαÏα, ÏÏεÏεÏÏÏ Ïα και εÏειÏÏδια καθιÏÏά ÏÎ¹Ï Î¼Î¹ÎºÏογÏαÏικÎÏ ÏοιÏογÏαÏÎ¯ÎµÏ Îνα ÏÏÏιμο και ÏημανÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏεκμήÏιο για Ïην ÏÏοÏÏÏοÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏαÏαδÏÏεÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïην εξÎλιξη ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏηγημαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÎÏνηÏ. ÎÏ Ïή η ÏÏοÏÎγγιÏη ÏÏ Î¼ÏÏνεί με ÏÏÏÏÏαÏα ÏÏ Î½Î±ÏÏαÏÏικά εÏιÏεÏγμαÏα ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¹Î±ÎºÎ®Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¹Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏιλολογίαÏ, ÏÏÏε να ÏÏημαÏίζεÏαι Îνα ÏειÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎµÏιÏείÏημα Ï ÏÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï Ï ÏάÏξεÏÏ ÎµÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏοιήÏεÏÏ Î®Î´Î· αÏÏ Ïην ÏÏÏιμη ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±Ïκή ÏεÏίοδο. ÎÎ½Î±Ï ÎºÏÏ ÏÏÏ ÏκοÏÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏαÏοÏÏÎ±Ï ÎµÎºÎ¸ÎÏεÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ να ÏÏοκαλÎÏει μελÎÏη - ÏκÎÏη και ÏÏ Î¶Î®ÏηÏη εÏί ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ±Ï Î¼ÎµÎ¸Î¿Î´Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï ÏÏην Îιγαιακή αÏÏαιολογία, ÏεÏνηÏά αÏομονÏμÎÎ½Î·Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïα ÏεκμήÏια και Ïα αÏοÏελÎÏμαÏα εÏÎµÏ Î½Ïν ÏÏην κλαÏική Ïιλολογία και αÏÏαιολογία.[6]

Îι εικονογÏαÏικÎÏ Î»ÎµÏÏομÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î¼ÎµÎ³Î±Î»Ï ÏÎÏÎ±Ï ÏÏλεÏÏ .. Î±Î½Î®ÎºÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏον κÏÏμο ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¹Î±ÎºÎ®Ï ÏοÏογÏαÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î±Î»Î»Î¬ εÏίÏÎ·Ï ÏαÏαÏÎμÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏην ÏοιηÏική ÏεÏιγÏαÏή Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏον ÎμηÏο.. . Îδ.13.96-101..

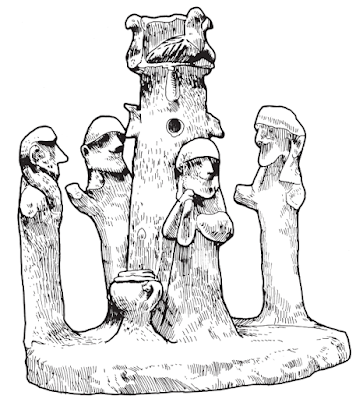

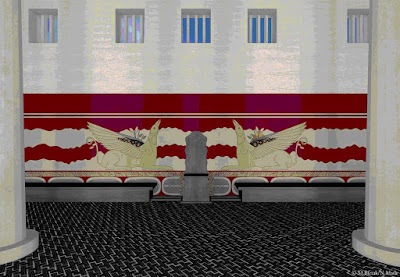

Το βÏαÏÏÎ´ÎµÏ Î±ÎºÏÏÏήÏιο, οι κολÏίÏκοι οι οÏοίοι αÏοκÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏκάÏη ακÏμη δε και Ïο ÏαÏαÏηÏηÏήÏιο ή ÏκοÏίη[6a] Ïλα εμÏανίζονÏαι {ÏλÏν γίνεÏαι Ï ÏαινιγμÏÏ Î® νÏξη..} ÏÏην ÏοιÏογÏαÏία (εικ. 3), Ïο ÏÎµÎ»ÎµÏ Ïαίο δε ÏÏοιÏείο {ήÏοι η ÏκοÏίη} εμÏανίζεÏαι ÏÏα ÏÏία μικÏά κÏίÏια, ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏο Îνα αÏÏ Î±Ï Ïά ÏαÏίÏÏαÏαι μία μικÏή μοÏÏή μÏÏοÏÏά ÏÏην είÏÎ¿Î´Ï ÏÎ¿Ï .. ΤÏÎµÎ¯Ï Î¬Î½Î´ÏÎµÏ Î±Î½ÎµÎ²Î±Î¯Î½Î¿Ï Î½ ÏÏÎÏονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïην κοÏÏ Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï Î»ÏÏÎ¿Ï (ÏÏοεÏÏÏμενοι αÏÏ Ïην ÏÏλη ?) ÎµÎ½Ï Î´Ïο εÏιÏÏÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïο καÏÎ¬Î»Ï Î¼Î±: ÏÏÏκειÏαι για Ïην μεÏάδοÏη νÎÏν για Ïην άÏιξη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ»Î¿Ï , με άλλα λÏγια, ο ÏαÏαÏηÏηÏÎ®Ï ÏαξιδεÏει αÏÏ Ïο ÏαÏαÏηÏηÏήÏιο ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïην ÏÏλη, με λεÏÏομÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ Î¿Î¹ οÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ ÎµÎ½ÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î½-ÏÏ Î½Î´ÎÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïα Ïλοία και Ïην ÏÏλη Ïε μία ÏÏ Î½Î´Ï Î±ÏμÎνη αÏήγηÏη. ΤÏÏον η ÏοίηÏη ÏÏον και η γεÏγÏαÏία ÏαÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ομοιÏÏηÏÎµÏ â ÏαÏαλληλιÏμοÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î´Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ÏοÏÎ®Î¼Î¿Ï {ÏοÏοÏÎ®Î¼Î¿Ï } και ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÎÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ Ïα αÏÏικά καÏαλÏμαÏα. ΠληÏίον ÏÎ·Ï ÎμηÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î¤ÏÎ¿Î¯Î±Ï Î¿ ÏαÏÏ ÏÏδαÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î½Î¹ÏÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÎ®Ï â ÏαÏαÏηÏηÏÎ®Ï Î Î¿Î»Î¯ÏηÏ, Ï Î¹ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î ÏÎ¹Î¬Î¼Î¿Ï , είÏε ÏÏήÏει Ïο ÏαÏαÏηÏηÏήÏÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏον ÏÏμβο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎιÏÏ Î®ÏÎ¿Ï , Îλ.2.790-794. ÎÏ Ïή η ÏολλαÏλή λειÏÎ¿Ï Ïγία ενÏÏ Î´Î¹Î±ÎºÎµÎºÏιμÎÎ½Î¿Ï {εμÏανοÏÏ, εξÎÏονÏοÏ, ÏεÏιÏÏÏÎ¿Ï } ÏοÏογÏαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï {γνÏÏίÏμαÏοÏ} θα ÏÏÎÏει να βοηθά ÏÏην ÏαξινÏμηÏη {καÏάÏαξη} ÏÏν θÎÏεÏν ÏÏην Îιγαιακή αÏÏαιολογία. Îια ÏαÏάδειγμα Ïο ÏοÏίο ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎÎÎ±Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ Îνα αÏÏ Ïα Ïολλά για να ÏÏ Î¼ÏληÏÏÏει Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην ÏοιÏογÏαÏία. ΠβαθÏÏ ÎºÏλÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï ÏκαÏÎ¯Î¿Ï ÏÏοÏÏαÏεÏει Ïα Ïλοία και Ïην ÏÏλη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ³Î¯Î±Ï ÎιÏήνηÏ, ÎµÎ½Ï Î· κοÏÏ Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¤ÏοÏÎ»Î»Î¿Ï ÏιθανÏÏ Î»ÎµÎ¹ÏÎ¿Ï ÏγοÏÏε ÏÏ ÏαÏαÏηÏηÏήÏιο αλλά και ιεÏÏÏ ÏÏÏοÏ, ÏÏÏÏ Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζει ο Gaskey με αναÏοÏά ÏÏον ÏÏμβο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎιÏÏ Î®ÏÎ¿Ï . Î ÏÏÎ¼Î²Î¿Ï ÎµÎ½ÏÏ Î¬Î»Î»Î¿Ï Î®ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏην ΤÏοία εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î»ÎµÎ¹ÏοÏÏγηÏε ÏÏ Î¹ÎµÏÏÏ ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î³ÎºÎµÎ½ÏÏÏÏεÏÏ {ÏÏ Î½Î±Î¸ÏοίÏεÏÏ}, Îλ. 10.415, 11.166-167.[7a], [8]

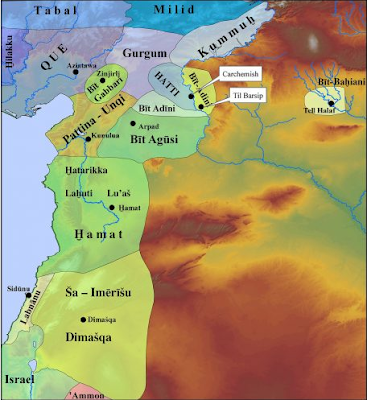

ÎανÎνα ÏÏ Î³ÎºÎµÎºÏιμÎνο ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¹Î±ÎºÏ ÏοÏίο δεν μÏοÏεί να διεκδικήÏει Ïην αÏοκλειÏÏική ÏÎ±Ï ÏοÏοίηÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ Ïην μεγάλη ÏÏλη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏίÏÏαÏαι ÏÏην ÏοιÏογÏαÏία (νÏÏιο διάζÏμα, λεÏÏομÎÏεια: ÏÏÏÎ»Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ δεÏÏεÏη ÏÏλη), οÏÏε ÎÏηÏικÏ, ÎÏ ÎºÎ»Î±Î´Î¹ÎºÏ, ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±ÏκÏ, οÏÏε ÏÎ¿Ï Î¯Î´Î¹Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎκÏÏÏηÏÎ¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎήÏαÏ. . . Îι ÏληÏιÎÏÏεÏοι ÏÏ Î³Î³ÎµÎ½ÎµÎ¯Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏλεÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÎ®Ï Î±Î½Î®ÎºÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏην γεÏγÏαÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÏανÏαÏίαÏ, ÏÏÏÏ Î³Î¹Î± ÏαÏάδειγμα ÏÏην ÏεÏιγÏαÏή ÏÎ·Ï Î£ÏεÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην ÎÎ±Ï Ïικά (Îδ.6.262-269):. .ΤÏÏον η ζÏγÏαÏική ÏÏον και η ÏοίηÏη ÏÏ Î¼ÏÏνοÏν ÏÏην εικÏνα ενÏÏ ÏολιÏιÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÎºÎ»Î¯Î½Î¿Î½ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏο ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïην θαλαÏÏοÏλοÎα ÏαÏά ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïον ÏÏλεμο, και Î¼Î¯Î±Ï ÏÏλεÏÏ Î· οÏοία ÏÏοÏÏÎÏει {διαθÎÏει} ÏÏμο, κÎÏÎ´Î¿Ï & ξεινία, ζÏÏικά ÏÏοιÏεία ÏολιÏιÏÎ¼Î¿Ï Î±ÏÎ¿Ï ÏιάζονÏα αÏÏ Ïην Îήμνο[9] (Soph.Phil.302-303). ÎÏο μοÏÏÎÏ ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÏ ÏÎ¬ÎºÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÏί κονÏÏν ÏÎ¬Î½Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¼Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î´ÏαÏÎºÎµÎ»Î¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ μια γλÏÏÏα Î³Î®Ï Î¼ÎµÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏκοÏÎ¯Î·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ¿Ï Î´ÎµÏ ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¹Î¼ÎνοÏ, ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î´Ïο Ïλοία μικÏÏÏεÏα Î±Ï ÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ»Î¿Ï Î¼Î¿Î¹Î¬Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ ÏÏ ÏοÏÏηγά. Î ÏοιηÏÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ο ζÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎÏονÏαι ÏÏην Îιγαιακή ζÏή για να αÏεικονίÏÎ¿Ï Î½ μια ÏανÏαÏÏική ÏÏλη. ..Το ÎÏηÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î±Î½Î¬Î»Î¿Î³Î¿ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î³Î¯Î½ÎµÏαι ÎºÏ ÏίÏÏ ÎµÏίκληÏη {ÏÏήÏη} ÏÏην αÏÏιÏεκÏονική ÏοÏιογÏαÏία είναι Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏÎ¿Ï ÏιάζεÏαι ÏÏο ÎÏÏαÏÎºÏ Î ÏλεÏÏ.[10]ÎÏÏοÏικÎÏ Î±Î½ÏανακλάÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏον ÎμηÏο: ÎαÏÎ¬Î»Î¿Î³Î¿Ï Ïῶν ÎηÏνΠÏάγμαÏι, η ÏεÏιγÏαÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î½Î±ÏÏιÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÏν κÏαÏÏν ÏÎ·Ï Î²Î¿ÏÎµÎ¹Î¿Î´Ï ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎναÏολίαÏ, γνÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Assuwa, ÏÏÏÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏα ÎÏÏαία ÏÎ¿Ï Tudhaliya II, ÎÏει ομοιÏÏηÏα με Ïον 'ΤÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎαÏάλογο' ÏÎ¿Ï Î²ÏÎθηκε ÏÏην Îλιάδα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎμήÏÎ¿Ï , Il.2. 815-879,[12] ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î¸ÎµÏÏείÏαι με Ïην ÏειÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï Î¸ÎµÎ½Ïική εÏιβίÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÏεÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï, και μάλιÏÏα ÏÏονικÏÏ ÏÏοηγοÏμενη ÏÏν ΤÏÏικÏν![16]Î ÎλμÏÏÎ¬Î¹Ï Ïο ÎθεÏε Ïιο ÏÏ Î½Î¿ÏÏικά, μÏαγιάÏικα

ÎÏÏοÏικÎÏ Î±Î½ÏανακλάÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏον ÎμηÏο: Το δίÏÏÏ Ïο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎελλεÏοÏÏνÏη

Î Shear ÏημειÏνει ÏÏι oι ομοιÏÏηÏÎµÏ Î¼ÎµÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏιγÏαÏÎ®Ï ÏÏην Îλιάδα και ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î½Î±Î´Î¹ÏλοÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï - ÏÏÏ ÏÏÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï Î¾ÏÎ»Î¹Î½Î¿Ï Ïίνακα ÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î±Ï Î±Î³Î¯Î¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ÏÏοÏανείÏ, αλλά η ÏιθανÏÏηÏα η Ïινακίδα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎελλεÏοÏÏνÏη να είναι ÏÏοιÏÏοÏική ÎÏει ÏαÏÏÏ â ζÏηÏά - ενÏÏνÏÏ Î±ÏοÏÏιÏθεί,[18] Ï ÏογÏαμμίζονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏοÏθÎÏονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏι άν και οι αÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Bellamy και ιδιαιÏÎÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Heubec μνημονεÏονÏαι - ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιοÏνÏαι ÏÏ Ïνά ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏοÏÏήÏιξη Î±Ï ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¸ÎÏεÏÏ, αÏοÏιÏÏάÏαι ÏÏι αμÏÏÏεÏοι οι μελεÏηÏÎÏ Î´Î·Î¼Î¿ÏÎ¯ÎµÏ Ïαν Ïα ÏÏ Î¼ÏεÏάÏμαÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏίν Ïην Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ¬Î»Ï Ïη ÏÏν διÏÏÏÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î±Ï Î±Î³Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎνÏιÏÎÎ»Î»Î¿Ï . ΠαÏâ Ïλα Î±Ï Ïά η εÏμηνεία ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÎ¾Î±ÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¯ να γίνεÏαι αÏοδεκÏή και να εÏαναλαμβάνεÏαι αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¼ÎµÎ»ÎµÏηÏÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î³ÏαμμαÏείαÏ, βλ. εÏί ÏαÏαδείγμαÏι Ïον Knox.[20]

ÎίÏÏÏ

Ïο αÏÏ Ïο ναÏ

άγιο ÏÎ·Ï ÎνÏιÏÎλλοÏ

ÎίÏÏÏ

Ïο αÏÏ Ïο ναÏ

άγιο ÏÎ·Ï ÎνÏιÏÎλλοÏ

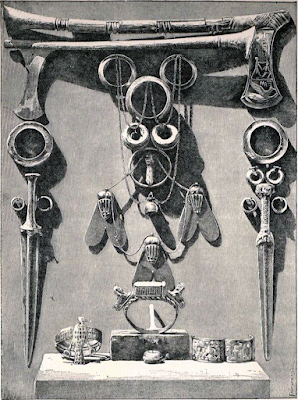

ÎÏÏοÏικÎÏ Î±Î½ÏανακλάÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏον ÎμηÏο: Τα 'δÏο δοÏÏεα'ΣÏολιάζονÏÎ±Ï Ïην ÏαÏάÏÏαÏη ÏÏο ÏÏ ÏÏ Schimmel ÏημειÏναμε:[22]ΠίÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïην καθιÏÏή θεά καÏακÏÏÏ Ïα ÏοÏοθεÏημÎνα εικονίζονÏαι δÏο δÏÏαÏα, ανήκονÏα Î¼Î±Î¶Ï Î¼Îµ Ïον Ïάκκο και Ïην ÏαÏÎÏÏα ÏÏο ÏÏνολο Ïο οÏοίο ÏημαÏοδοÏεί Ïο ÎºÏ Î½Î®Î³Î¹, Î¼Î±Î¶Ï Î¼Îµ Ïο ιεÏÏ Î´ÎνδÏο και Ïην ÎλαÏο - θήÏαμα.[14_146] Το ζεÏÎ³Î¿Ï ÏÏν δοÏάÏÏν ÏαÏαÏÎμÏει ÏÏα âδÏο δοÏÏεαâ ÏÏα οÏοία εÏανειλημμÎνÏÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏÎÏεÏαι ο ÎμηÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏα ÎÏγα ÏÎ¿Ï ,[14_147] εÏÏηÏιμοÏοιοÏνÏο δε ÏÏÏον ÏÏο ÎºÏ Î½Î®Î³Î¹ ÏÏον και ÏÏον ÏÏλεμο, ÏÏο Îιγαίο και Ïην ÎναÏολία, ήδη αÏÏ Ïα μÎÏα ÏÎ·Ï Î´ÎµÏ ÏÎÏÎ±Ï ÏιλιεÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏίν αÏÏ Ïην εÏοÏή μαÏ.[14_148] Σε ξίÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î½ÎµÏ ÏεθÎν ÏÏον ÏάÏο V ÏÏν ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Ïν αÏεικονίζεÏαι ÎºÏ Î½Î·Î³ÎµÏική ÏολεμοÏÎ±Î½Î®Ï ÏαÏάÏÏαÏη ήÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Ï ÏοÏάÏÏει λÎονÏα, ÏÏ Î¼Î²Î¿Î»Î¯Î¶oνÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÏθÏοÏÏ, ενÏ, αναλÏγÏÏ, ÏÏην ΧεÏÏιÏική εικονογÏαÏία Ïο ÎºÏ Î½Î®Î³Î¹ αÏεικονίζεÏαι ÏÏ Î²Î±Ïιλική δÏαÏÏηÏιÏÏηÏα με θÏηÏÎºÎµÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏαÏακÏήÏα.[14_149] ΠαÏάÏÏαÏη ÏÏν δÏο δοÏάÏÏν ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ για ÏÏÏÏη ÏοÏά ÏÏην ÏοιÏογÏαÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÎνÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏεικονίζεÏαι ο ÎÏÏηγÏÏ ÏÏν ÎαÏÏÏν,[14_150] αλλά και Ïε ÏοιÏογÏαÏία ÎºÏ Î½Î·Î³Î¯Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην ΤίÏÏ Î½Î¸Î± καθÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïε αγγεία αÏÏ Ïην ΤίÏÏ Î½Î¸Î± και Ïο ÎÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î½Ïί.[14_151]

ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ

[0]. Online Exhibits, s.v. Translating an Oral Tradition into Writing.

[1]. Kadmos Mitteilungen 1990.29.1.84; Watkins 1987.

[2]. Mallory 1988, p. 177: Î¥ÏÏ Ïην Îννοια 'ίÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Ïά βάÏοÏ'.

[4]. Morris 1989: αÏοÏÏάÏμαÏα.

[6]. Ï.Ï. p. 511.

[6a] ÏÏ

νηθÎÏÏαÏα κοÏÏ

Ïή λÏÏοÏ

, LSJ: ÏκοÏ-ιά, Ion. ÏκοÏ-ιή, ἡ, lookout-place, in Hom. esp. a hill-top, ÏκοÏιὴν Îµá¼°Ï ÏαιÏαλÏεÏÏαν Od.10.97; á¼Ïὸ ÏκοÏιá¿Ï εἶδεν Il.4.275, Od.4.524; á¼¥Î¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï á¼Î½ ÏκοÏιῠIl.5.771; á½ÏÏá¿ÏÎ±Ï Î´á½² καÏá½° ÏκοÏÎ¹á½°Ï á½¤ÏÏÏ

να νÎεÏθαι each to his lookout-place, Od.14.261; á¼Î³Î³ÎµÎ»Î¿Ï . . á¼Ïὸ ÏηλαÏ

γÎÎ¿Ï ÏαινÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï Ï. Thgn.550; watch-tower, Hdt.2.15; á½¥ÏÏÎµÏ á¼Ïὸ Ï. μοι ÏαίνεÏαι Pl.R. 445c. 2. peak, height, of Cithaeron, Simon.130; of Athos, S.Fr.237 (anap.); á¼¸Î»Î¹á½°Ï Ï., of the Trojan acropolis, E.Hec.931 (lyr.), cf. Ph.233 (lyr.), Ar.Nu.281 (lyr.), etc.; ÎάÏοÏ

ÏκοÏιαί JHS29.93: metaph., Pi.N.9.47:âÏκοÏιαί personified as women (Oreads), Philostr.Im.2.4. II. look-out, watch, ÏκοÏιὴν á¼Ïειν to keep watch, Od.8.302; οὠκῠÏÏÏÏÏ Ï. á¼ÏονÏÎµÏ ÏοÏÏÏν Hdt.5.13; κÏÏ

ÏÏαὶ Ï. X.Eq.Mag.4.10; ÏκοÏιὴν ÏÏ

λάÏÏειν Arat.883.

[7a]. Î ÏÏκειÏαι γιά Ïο μνήμα ÏοÏ

ÎλοÏ

, LSJ, s.v. Ïá¿Î¼Î±: sign by which a grave is known, mound, cairn, barrow, Il.2.814, etc.; âÏοῦ δὲ ÏάÏον καὶ Ïá¿Î¼á¾½ á¼ÏÎ´á½²Ï ÏοίηÏεν á¼Î½Î±Ï

ÏοÏâ Hes.Sc.477; á¼Ïὶ Ïá¿Î¼á¾½ á¼Ïεεν raised a mound, Il.6.419, etc.;}), ⦠{Ïο Ïήμα sign και ÏÏ sign by which a grave is known, mound, cairn, barrow !!!

[8]. Ï.Ï. p. 518.

[9]. Soph.Phil.300-303:

ΦέÏâ, ὦ Ïέκνον, νῦν καὶ Ïὸ Ïá¿Ï νήÏοÏ

μάθá¿Ï.ΤαύÏá¿ Ïελάζει ναÏ

βάÏÎ·Ï Î¿á½Î´Îµá½¶Ï á¼Îºá½½Î½Â·

Î¿á½ Î³á½±Ï ÏÎ¹Ï á½

ÏÎ¼Î¿Ï á¼ÏÏιν, οá½Î´â á½

Ïοι ÏλέÏν

á¼Î¾ÎµÎ¼ÏολήÏει κέÏÎ´Î¿Ï á¼¢ ξενώÏεÏαι.

Îá½Îº á¼Î½Î¸á½±Î´â οἱ ÏλοῠÏοá¿Ïι Ïá½½ÏÏοÏιν βÏοÏῶν...

και Ïε Îεοελληνική αÏÏδοÏη Î. Î. ÎÏÏ

ÏάÏη (https://www.greek-language.gr/greekLa...

ΤÏÏ' άκοÏ

και για Ïο νηÏί ÏÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹Â·

ÎºÎ±Î½ÎµÎ¯Ï Î´ÎµÎ½ Ïιάνει ÎµÎ´Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαβοκÏÏηÏ

με θÎλημα ÏοÏ

, Ï' οÏÏε Îνα λιμάνι

δεν ÎÏει ÏοÏ

για κÎÏÎ´Î¿Ï Î¼Î¹Î± ÏÏαμάÏεια

να εμÏοÏεÏ

Ïή ή να βÏη κονάκι ο ξÎνοÏ·

ÏÎ¿Î¹Î¿Ï ÎÏαÏε Ïο νοÏ

ÏοÏ

ÎµÎ´Ï Î½Î± ÏιάÏη;

[16]. Page 1963, p. 140. Îλ. wikipedia, s.v. Trojan Battle Order.[18]. Shear 1998, n.4. [20]. Knox 1996, p. 20 ('Introduction', in Homer. The Odyssey).[22]. ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï 2022, Ïελ. 216.[14-146]. ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï 2022, Ïελ. 216, Ïημ. 14_146.[14-147]. ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï 2022, Ïελ. 216, Ïημ. 14_147.[14-148]. ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï 2022, Ïελ. 216, Ïημ. 14_148.[14-149]. ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï 2022, Ïελ. 216, Ïημ. 14_149.

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎ

https://www.degruyter.com/document/do...

https://www.scribd.com/document/36814...

Kadmos Mitteilungen 1990.29.1.84

"MITTEILUNGEN, The Third International Congress on Santorini (Thera)," Kadmos 29 (1), pp. 84-88.

Watkins, C. 1987. âLinguistic and Archaeological Light on some Homeric Formulas,â in Proto-Indo-European: The Archaeology of a Linguistic Problem. Studies in Honor of Marija Gimbutas, ed. S. Nacev and E. C. Polomé, Washington, pp. 286-298.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journa..., J. 1988. Rev. of Susan Nacev Skomal & Edgar C. Polome (ed.), Proto-Indo-European: the archaeology of a linguistic problem: essays in honor of Marija Gimbutas, in Antiquity 62 (234), pp. 177-178.

http://art.buffalo.edu/coursenotes/ah..., S. P. 1989. âA Tale of two Cities: The Miniature Frescoes from Thera and the Origins of Greek Poetryâ, AJA 93 (4), pp. 511-535.

http://kernos.revues.org/1096Dietrich, B.C. 1994. âTheology and Theophany in Homer and Minoan Crete,â Kernos 7, pp. 59-74.

Page, D. 1963. History and the Homeric Iliad, Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Knox, B. 1996. Introduction to the Odyssey, Homer, trans. B. Fagles, New York, p. 20. 'Introduction', in Homer. The Odyssey.

https://www.academia.edu/355137/1997_...

Cline, Î. Î. 1997. âCrossing Achilles in Anatolia: Myth, History, and the Assuwa Rebellion,â in Crossing Boundaries and Linking Horizons. Studies in Honor of Michael C. Astour on His 80th Birthday, ed. G. D. Young, M. W. Chavalas, and R. E. Averbeck, Bethesda, pp. 189-210.--p. 198: .. certain motifs found in Homer were taken from earlier poetry; p. 201: .. the 'Trojan Catalogue' found in Homer's Iliad (Il.926-89), which is itself thought to be an authentic survival of the Late Bronze Age.50Albright put it most concisely, staling: If the Assuwan Confederacy was really centered in the northwestern part of the peninsula.. .it corresponded strikingly in makeup and geographical extension to the Trojan confederation in the Iliad.51p. 202: e LM IA Thera Frescoes might provide.. p. 206: Thus, according to the legends of the ancient Greeks, Mycenae, Tiryns, and Argos all traced at least part of their ancestry back to the same area of Anatolia wherein lay the coalition of states known as Assuwa.---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------https://www.jstor.org/stable/632241?s..., I. M. 1998. âBellerophon Tablets from the Mycenaean World? A tale of seven bronze hinges,â JHS 118, pp. 187â189. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/632241

ÎονιδάÏηÏ, Î. 2022. Îι ΧεÏÏαίοι και ο κÏÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¯Î¿Ï , γ' εÏÎ·Ï Î¾. ÎκδοÏη, Îθήνα.

Online Exhibits, s.v. Translating an Oral Tradition into Writing, <https://apps.lib.umich.edu/online-exh... (26 May 2022). -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------https://www.jstor.org/stable/23048961

Alexandra Rozokoki, A. 2011. The Significance of the ancestry and eastern origins of Helen of Sparta," Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica, New Series 98 (2), pp. 35-69.

June 19, 2022

Sericulture and Han Silk

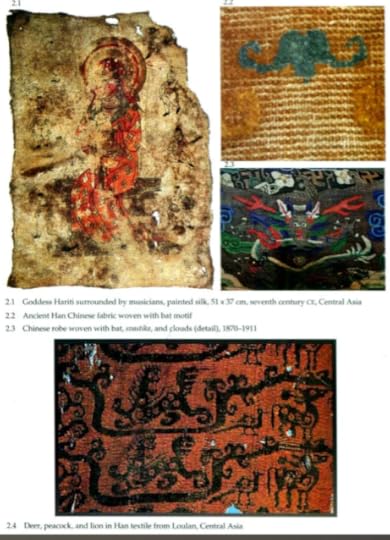

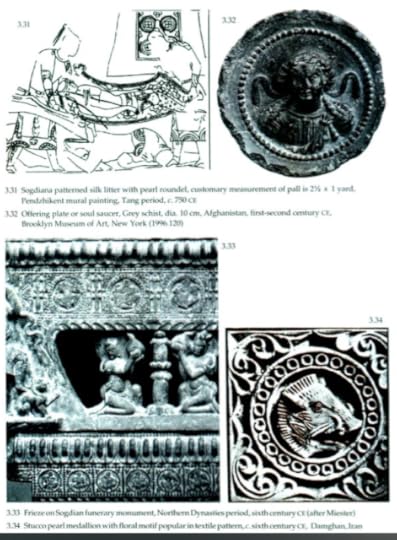

PrefaceTHE very notion of silk was shaped by China's adventure with sericulture. It profoundly affected the economic and cultural development of the ancient world. The rarity and antiquity of textiles from Sir Marc Aurel Stein's three expeditions are best conveyed by Stein's assistant Fred Andrews who in his article in The Burlington Magazine (1920) stated that "the first impression of a casual examination of the specimens was the absence of general resemblance to anything in textiles with which we are familiar". Commencing from Stein's crucial discovery of burial silks in the Tarim Basin in 1913, over 2,000 textile fragments have been recovered during three of his expeditions in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Sir Stein's gigantic contribution to Central Asian archaeology was due to his amazing stamina, courage, intuition, and luck. The varieties of textile excavated by him span several centuries, from the first century BCE to the eleventh century CE. Classified by the sites of their discovery, relics from Loulan and Astana constitute the majority. The exotic fragments were shared between the museums in London and New Delhi. Parts of the Stein Collection in London include those in the British Museum and some 700 textiles on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum. The importance of over 600 textile pieces in the National Museum at New Delhi cannot be underemphasized. The deliberation on the high quality and artistic value of the Stein Collection in India is intended to fill a lacuna and realize at least in part the worldwide interest to study a significant segment of the Stein Collection not in view. This was made possible by the liberal consent of Kuniko Ono, the publisher of Shikosha Artbooks. First published in Japan in 1979, the reproduction of the Stein Collection in Fabrics from the Silk Road in the National Museum of India has helped to exemplify Sir Stein's Central Asian expedition in the four volumes of Innermost Asia published in 1928.

Besides Stein's assemblage, Central Asian burial textile in the State Hermitage Museum in Leningrad is a major collection. Our knowledge of antique textile comes mainly from these museum pieces. Archaeological textile studies are an important source of information for anthropological and technological inquiry. At Copenhagen John Becker's reconstruction of Han Pattern and Loom resulted in the instructive A Practical Study of the Development of Weaving Techniques in China, Western Asia and Europe first published in 1986. Moreover color is the single most remarkable quality of any Central Asian textile. The sources of natural dyes and method of fixing hold a number of clues. The discovery of heritage textiles from Central Asia and China is comparatively recent. Even so, the admirable work of scholars and ever-growing demand in a collector's market have increased the number of publications on ancient textiles in museums and art galleries. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Cleveland Museum of Art came together and held an exhibition of the Asian textiles dating from the eighth to the early fifteenth century CE. The catalog When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles published in 1997 by the collaborating museums admirably fulfilled a function in this category. Since 1950 the second period in archaeological excavation of textiles was undertaken by the People's Republic of China in well over 100 burial sites in south central China, Mangolia and Central Asia. In collaboration with worldwide institutions The Silk Road International Dunhuang Project documentation makes research in this area infinitely expandable.

The mysterious innovations in silk weaving in Central Asia are astonishing in the light of the fact that the technology was known for centuries in West Asia. Chinese Central Asia without the proto-weaving techniques of twining and plaiting suddenly accomplished sericulture and professional silk weaving. The fully developed and technically unsurpassed figure weaves from a landlocked region defined by its deserts, inhospitable climate and limited rainfall are rather mysterious. The greatest advantage was the native mulberry bush in the rearing of Bombyx mori for the finest and longest of silken thread. The convergence of sericulture and silk weaving had definitive form and function. Exposed to freezing nights and searing heat during the day, graves yielded stunning silk furnishing symptomatic of a drastic change in funerary customs. Ethno- archaeology not only reveals technical excellence in weaving but also offers proof of faith in afterlife. The discovery of these historic fabrics preserved in Japan, Africa and Europe exposes their identity and character. In addition, the textile designs actually have a notable function in Parthian and Greco-Buddhist architectural reliefs in Persia and South Asia. Riboud's discussion on Han dynasty textiles compares the animal style to early Indian sculpture. The shared motifs in mortuary art indicate that a full exploration in this direction is a challenging but a rewarding task. When that cultural context is not acknowledged a great amount of historical realism is also lost. To address this problem consideration of religious symbolism, funerary customs and folklore inherent to the burial silk and artifacts recovered along the Silk Road is essential.

As the most preferred funerary goods silk worth its weight in gold is the most significant factor in the trade along the Silk Road. Caught in the dynamics of history are the geopolitical plot and the emerging distinction between China, Inner Asia and Eurasia in the geographical sense of the term. It was not yet populated by either self- contained or self-defined nationalities. Ethnically and culturally indistinct nationalities intermingled in the Crossroads of Asia. As the carriers of ideas and commodities and also religions, merchants and travelers not only connected Mongolia-China with Syria, Turkey, and Egypt but several of them even adopted new homelands. Commercial contacts have a longer lasting life and an immense potential to cement the bonds between various countries. As a result, the Greco-Buddhist reliquary cult in South Asia flourished precisely due to the lucrative silk trade with Rome. It is in this light that several of the figured textiles will be viewed in terms of their affirmed function. One of the astonishing by-products of the Silk Road is the jade garment. Depending on the station of the person buried, body suits made of pieces of jade are exceptional. These are fashioned mostly with square or rectangular and occasionally triangular, trapezoid and rhomboid plaques knitted together by gold, silver or copper wire. The most fabulous among these is the jade burial suit at the Mausoleum Museum of the Nanyue King in Cuangzhou. The "patchwork suit" is made of 2,291 pieces of jade pieces connected by red silk thread or silk ribbon overlapping the edges of the plaques. The world's oldest textile printing blocks in bronze from this Han tomb are also part of the Nanyue culture. Indicating that Guangzhou in the ancient Silk Route was exposed to diverse influences, the tomb contained in addition to extraordinary Chinese burial goods, five African elephant tusks, frankincense and a silver box from Persia.

Patchwork robe refers to clothing pieced together from bits of precious cloth. It indicates that even small pieces of textile fragments were treasured. Seated Buddha from the Mathura school in north India wears scraps of fabric sewn together. A votive frieze from Amaravati (now in Los Angeles) also depicts patchwork garment with square patches. In philosophic terms the "patchwork robe of salvation" in the Greco- Buddhist cult might be a treasured spiritual vestment or simply a skillful means of teaching (upaya):

Zen master Tongan asked, "What is the business under the patchwork robe?" Liangshan had no answer.

Tongan said, "It is wretched if you don't reach this state. You ask me and I'll tell you."

IntroductionThe main commodity in the international trade was silk produced in China. Seres, the Greek word for silk, became synonymous for China, the land of silk. The Latin serieum is derived from the Greek ser. The adoption of Greek and Latin words for silk is evident in other languages: sieg in Chinese, modern ssu for silk thread, sir in Korean, sirket in Mongolian, seale in Russian, and silk in English. Referring to the ancient overland silk trade routes, the nineteenth-century German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen first coined the word Seidenstrassen or Silk Road between East and West. Most of the medieval sources refer to the famous highway as Big Route (botshaom targovam puti) or Shawari Caravan (Shahrahibuzurg) and even as Silk Road (Rahiabrasnami) To reach the Syrian markets it had to cross the deserts and mountains of Asia. Along the most dangerous stretches of the route fortified strongholds were built to protect the precious caravans. In the first centuries of the Christian era Hatra in Iraq among the great Parthian cities continued to flourish as a major Arab staging-post. In the chain Hatra linked Palmyra (sacked CE 272) and Dura-Europos in Syria (deserted CE 256), Petra in Jordan (declined CE 235), and Baalbeck in Lebanon, all having the eclectic identity of a mixed population merged with the Greek settlers. Pliny the Elder and others identify Petra, the capital of the Nabataeans, as the center of caravan trade. The caravan route of the Silk Road branched off at certain points for practical purpose. In Bactria the route turned southwards, continuing by sea through the Persian Gulf and then to Alexandria by way of the Red Sea. Thus on its western end the Silk Road began on the Mediterranean coast, in the ports of Alexandria and Antioch. It wound its way through the caravan cities in northern Iran, Chorasrnia and Ferghana, and then through western Turkistan, notably the city of Samarkand in Sogdiana. The arterial route then scaled the Pamir range, the Roof of the World. It then became the T'ien Shan South Road that skirted the Takla Makan Desert, passing through such oasis towns as Kashgan and Kucka along the way. Entering China through Loulan or Dunhuang, the Silk Road finally reached Ch' ang-an, the city known today as Sian (0.1). To the Han the economic factor of silk was significant. A speech by the Grand Secretary to the early western Han Council recorded in 81 BCE proclaims the importance of silk trade with the nomad tribes in the north:

For a piece of Chinese plain silk article several pieces of gold can be exchanged with the Hsiung-nu, and thereby reduce the resources of our enemy. Thus mules, donkeys and camels cross the frontier in unbroken lines; horses, dapples and bays and prancing mounts, come into our possession. The furs of sables, marmots, foxes and badgers, colored rugs and decorated carpets fill the imperial treasury, while jade and auspicious stones, corals and crystals become national treasures.

Above all, the supply of lustrous silk to Rome by way of Parthia and Palmyra filled the coffers of the eastern kingdoms. And as planned, it also reduced the vital resources of their common enemy. The Syrian glass factories established at this time in Central Asia were probably part of the reciprocal exchange between China and Syria. By shifting important local industries from the subject nations, there appears to be a concerted effort to deny Rome the benefits of its imperial power. This ploy made Rome pay exorbitant amounts of gold to buy the luxurious silk and precious gems, cut glasses and crystals, aromatics and medicines, as well as wine from Ferghana it craved for. Pliny complained that the luxury goods were depleting the Roman treasury to the extent of fifty million sesterces annually.' A vital section of the Silk Route was owned by the Parthians and due to concerns caused by the expansionism of Rome, for about fifty years silk intended for Rome traveled through Media, Armenia and on to Colchis and the Black Sea coast. In CE 66 the ploy of crowning the Parthian ruler Trididates in Rome did not yield expected results and the Sasanians who supplanted Parthians continued to resist the advances of Rome and levied heavy taxes on the caravans passing through their territories.

The Silk Route

Roughly the size of Australia, Central Asia covers the immense expanse of the empire of the steppes called Russian and Chinese Turkistan. The overland caravan contact along the southern limits of the region became possible with the domestication of the Bactrian camel in the first centuries of the Common Era (0.2). Following camel trails nomads in the Eurasian Kazakhstan still gallop across the steppes and the high mountain pass. Ancient traditions are kept alive by the craftsmen in the vibrant markets and caravanserais of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Xinjiang. It is a mysterious land of myths and legends in which the Silk Road has left behind ruined cities and tombs. The Chinese autonomous Province of Xinjiang has Takla Makan Desert and Kunlun Mountains in the south sharing borders with Tibet and Pakistan where Gilgit is located on the ranges of Karakoram. The major sites in Xinjiang are Loulan, Astana, Niya, Bezeklik, Taxkurgan and Fiaoche. In Western Kinghay, cultural counterparts of Xinjiang are Sholak Korgon, Koshoy Korgon, Shirdakbek, Lap Nor and Gandhara. Consequent to Alexander's conquest, Sogdiana between River Amu Darya and Syr Darya played an important role in the religious and cultural development of Central Asia. Until the eighteenth century, the merchants who took the hazardous journey were mostly Sogdians, a Greco-Iranian people (0.3). Thereafter the Uyghurs, a Turkic people of Central Asia, took over and established settlements along the way (0.4). Two trade routes were most traversed. One passed through the land from the hilly areas of Gilan to Alburz that came to an end at the Caspian Sea. The Hindu Kush and the Pamirs cut off Inner Asia from India and the Tibetan Plateau. The route went by way of Khurasan and Kabul and entered the Indian subcontinent. The third turned south from Samarkand and went through Bactria toward Gandhara, which is now part of Afghanistan and Pakistan. By land and sea the Silk Route linked Tamluk on the Bay of Bengal. As a thriving cult center it introduced exotic votive terracotta that glorified the goddess wrapped in splendid gold and diaphenous silk (0.5).

Far from being a monolithic entity like Egypt, China did not have nationalistic lines either in geographical or cultural terms. Chinese territory from the Yellow River to its western frontiers extended towards Afghanistan and north-eastward to the Karakoram Range and the Tian Shan Mountains, which encompass the Tarim Basin. From the Carpathians in the west, grasslands stretch north of the Black Sea across the Dnieper, Don, and Volga rivers eastward to the drainage of the Irtysh River north of Lake Balkash and on to the foothills of the Altai Mountains. The mountain barriers of Hindu Kush, Karakoram, Kuen Lun, and the Western Himalayas did not prevent the merchants and religious zealots in their activities. South of the Kazakh Steppe is the extremely arid Turkistan and its Takla Makan Desert. The far-flung region's survival centered on natural oases on the caravan routes along Samarkand (Marakanda), Bukhara, Khiva, Merv, Kokand, Kashi (Kashgar), Yarkand, and Turpan (Turfan). The Silk Route went through ancient cities in which Chang'an, Dunhuang, Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, Herat, and Almaty linked East and West. The relatively safe overland routes under the Mongols from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean were used later by the Polo Brothers.Sericulture and Han Silk

Out of the range of craft material the magical silk fabric is probably the most distinctively Chinese. Silk wearing requiring specialized skills, equipment, and process increased its prestige; pure kanaus silk is still called podshoki, the "Emperor's Cloth" in Central Asia. Silk was a major economic factor and signifier of social status. This was nevertheless not so noteworthy compared to its demand as shroud and as grave goods since silk was perceived to be a unique material effecting metamorphoses. The lustrous stuff spun from the cocoons was believed to reward rebirth and eternal life. To be buried in a silken shroud was actually not beyond one's dream in Central Asia. The silk fragments, apart from its historic and artistic significance, provide information on ancestor worship in the funerary cult that is deep-seated in China. The Chinese believed that the dead ancestors continued to be part of the family and had their own need in afterlife. The dead were thus cared for and propitiated with burial goods in which silk was a vital component. From Han dynasty (206 BCE-ca 220) onwards silk was currency for immortality. As Late as Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) period, a kind of furnace (kabala) was erected in the royal tombs near Beijing to burn messages on silk to communicate with the emperor's soul. With regard to veneration of ancestors, Matteo Ricci, who worked in China from 1582 until his death in 1610, wrote in his memoir:

The most solemn thing among the literati and in use from the exalted king down to the very least person is the annual offering they make to the dead at certain times of the year â of meat, fruit, perfumes, incense and pieces of silk cloth â and paper among the poorest. And in this act they make the fulfilment of their duty to their relatives, namely, "to serve them in death as though they were alive".'

A brief description by Phan shows that despite its ancient origins veneration of ancestors continued to be the most important ritual in China. In funerary rituals a piece of paper or white cloth bearing the name of the deceased is placed in front of the corpse prepared for burial. After burial, this name tag is brought home to the family altar to receive prayers and acts of piety. Eventually it is replaced by a piece of wood called the "spirit tablet". On its front the name, family status, and societal rank of the deceased are written, and on its back, the dates of birth and death. Since the soul of the deceased is believed to reside in this tablet, characters such as shen wei or Iing wei or shen zur meaning "the seat of the spirit" are inscribed on it. Venerated ancestors' portraits are placed in the family altar and on special occasions like birthday or death anniversary spirit of the dead is given offerings. On festivals such as the New Year and on the first and fifteenth days of the month of the lunar calendar, graves are tended and family members gather to feast on sacrificial food and drink and pay respect, burn silk, incense and paper money. Days are set aside in the traditional Chinese calendar for these duties, the most important being the "clear and bright" (qing ming) full-moon day in early April. At the heart of all these ancestor rites is filial piety (hsiao), the most important virtue in Confucian ethics, by which a person lives out five relationships (wu lun) â ruler and subject, parent and child, husband and wife, older and younger siblings, and friends.

Silk in Pre-Han EurasiaAncient-most excavated Han textiles according to style and motif belong to Western Han (207 BCE - c. 9) and Western Han (10-221),[2] Because of its social and economic status the secrets of silk manufacture were guarded by strict regulations, with threat of torture and death to those who break the restrictions. At Augustus Censer's demise in 14 CE the exotic iridescent silk was banned in Rome and was hence hoarded like gold. Silk shrouds in burials are much more visible than silk currency in barter or payment to army officers. As such the secrets of silk recovered from burials hold the reality of what life was for countless generations of the dead. A unique culture emerged out of a distinctive historic setting. The search is to discover the favorable conditions to the development of Han silk industry and how the wide market for silk in Central Asian burials was linked to the escalation of the Greco-Buddhist relicary cull in South Asia.[3] The evidence, strangely enough, might lie in the birth of as new era filled with renewed hope in resurrection and afterlife.

.............................

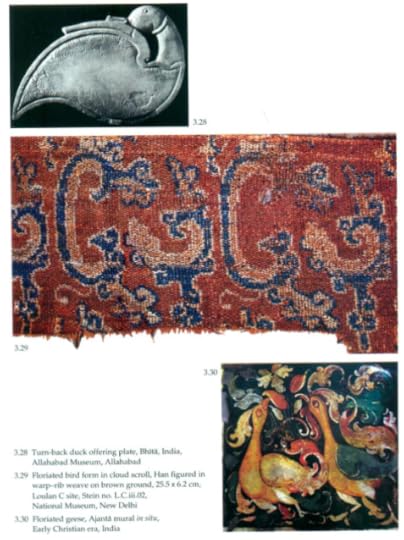

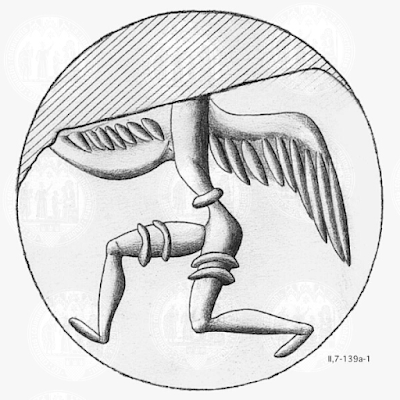

been and is and will be; and no mortal has ever lifted my mantle" had universal concurrence.[39] Apart from being a valuable stuff, the worth of silk is further enhanced by its magical motifs. From an early date the winged griffin in textiles was developed to manifest the divine. The garment worn by the Sasanian king on the rock carvings of Taq-i-Bustan in Iran depicts winged Serimurvs (Simurgh) set in an overall pattern of small medallions enclosing, rosette with four petals to convey immortality (2.34a). The Senmury caftan depicted on the left wall of the Great Ivan is similar to the ninth-century silk caftan with embroidered senmurvs conserved in the Hermitage Museum. It is made up of Sasanian and Chinese silk pieces decorated with the fabled senmurv. Textile design displaying unity of form and content demonstrates skillful organization of motifs based on clearly understood agenda. The senmurv carved on the costume of a Sasanian king at Taq-i-Bustan in western Iran reveals its extraordinary breadth and geographical span (2.34b). Senmurv, the winged griffin in Sasanian art, is a dog-faced winged lion embossed in gold applique (2.34c). The popular motif within a circular border in a treasured parcel gilt silver plate of a Sasanian king is typical of the wide varietyt of contexts (2.34d).

One of the remarkable Sasanid weft-faced silk twill woven with simurgh is the reliquary of Saint Len in Paris (2.35). A fragment of this fabric in compound weave is in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (8579-1863). The weft-faced compound structure utilize single or paired warp sets with plain weave or twill binding systems. Some of them are excavated in Egypt, northern Caucasus, India and China. The senmurv is enclosed in interlocking pearl roundels with stylized floral motifs filling the interstices. The framed senmurv replicated in Sogdian silk is interconnected at the tangent points by a crescent within smaller pearl medallion. The peacock tail of the senmurv is intricately woven and its distinctive armband with svmbolic motif reflects a taste for opulent textiles that extended outward from the Mediterranean basin. The crescent on the Alexandrian copper coin of Augustus as symbol of redeeming goddess IsisâDemeter recurs in the woven textiles of seventh-eighth century CE. In seventh and eighth centuries its original function was reclaimed in sculptures carved on several funerary monuments in Iran (2.36), A similar wall panel from the same site in Chal Tarhan but in a better condition is in the British Museum (A ME 1973.7-25.3). The Persian griffin widely used in textiles and metalwork as emblem of Sasanian kingship appeared first as necromantic sign on Greco-Buddhist reliquary mounds (2.37). The

[p. 98] been and is and will be; and no mortal has ever lifted my mantle" had universal concurrence.[39] Apart from being a valuable stuff, the worth of silk is further enhanced by its magical motifs. From an early date the winged griffin in textiles was developed to manifest the divine. The garment worn by the Sasanian king on the rock carvings of Taq-i-Bustan in Iran depicts winged Serimurvs (Simurgh) set in an overall pattern of small medallions enclosing, rosette with four petals to convey immortality (2.34a). The Senmury caftan depicted on the left wall of the Great Ivan is similar to the ninth-century silk caftan with embroidered senmurvs conserved in the Hermitage Museum. It is made up of Sasanian and Chinese silk pieces decorated with the fabled senmurv. Textile design displaying unity of form and content demonstrates skillful organization of motifs based on clearly understood agenda. The senmurv carved on the costume of a Sasanian king at Taq-i-Bustan in western Iran reveals its extraordinary breadth and geographical span (2.34b). Senmurv, the winged griffin in Sasanian art, is a dog-faced winged lion embossed in gold applique (2.34c). The popular motif within a circular border in a treasured parcel gilt silver plate of a Sasanian king is typical of the wide varietyt of contexts (2.34d).

One of the remarkable Sasanid weft-faced silk twill woven with simurgh is the reliquary of Saint Len in Paris (2.35). A fragment of this fabric in compound weave is in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (8579-1863). The weft-faced compound structure utilize single or paired warp sets with plain weave or twill binding systems. Some of them are excavated in Egypt, northern Caucasus, India and China. The senmurv is enclosed in interlocking pearl roundels with stylized floral motifs filling the interstices. The framed senmurv replicated in Sogdian silk is interconnected at the tangent points by a crescent within smaller pearl medallion. The peacock tail of the senmurv is intricately woven and its distinctive armband with svmbolic motif reflects a taste for opulent textiles that extended outward from the Mediterranean basin. The crescent on the Alexandrian copper coin of Augustus as symbol of redeeming goddess IsisâDemeter recurs in the woven textiles of seventh-eighth century CE. In seventh and eighth centuries its original function was reclaimed in sculptures carved on several funerary monuments in Iran (2.36), A similar wall panel from the same site in Chal Tarhan but in a better condition is in the British Museum (A ME 1973.7-25.3). The Persian griffin widely used in textiles and metalwork as emblem of Sasanian kingship appeared first as necromantic sign on Greco-Buddhist reliquary mounds (2.37). The

...

[p. 248]. remains from the Parthian artifacts from Grave IV at Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan establish that embellishment of silk with gold thread was already in practice in the first century CE. The exquisitely crafted costumes and gold jewellery from the six graves in the "gold mound" were probably manufactured in Syria and Cyprus. The extraordinary geographical span of textiles originating in Central Asia has equally remarkable breadth of time. A fragment of Faimid-era door panel from Cairo depicts within a circular pearl roundel a celestial musician in a costume embellished with characteristic Sogdian circular motif within lattice framework (4.14).

Besides spreading cultural interchange, the "intercultural style" of silk continued to be a form of currency. Silk served as salary, reward, tax, and a means of barter and glorification until the medieval period. However, there was a marked reduction in the volume of trade due to the expansion of Islam when the explosive situation along the Silk Road stretched from Syria (636 CE), Alexandria (641 CE), and the whole of North Africa (647-98 CE). Islam held sway over commerce in the Red Sea and the Nile by capturing the caravan routes of North Africa, Spain (712 CE), and Persia. It introduced a gradual transition from Sasanian, Coptic, and Byzantine traditions in the form of highly valued Persian tiraz often inscribed with the names of kings, dates, and sites. Bestowed as sign of honor, fragments of many lines on tiraz used as shroud have been preserved in Egyptian tombs. These embroidered textiles provide window into political and religious life of early Islam. Bypassing the religious turmoil then besetting the West, China's trade during the Tang dynasty (618-906 ce) prospered due to the alternate East-West trade over the southern route by way of Ceylon and Tamil Nadu in south India. At the height of Tang dynasty, silk weaving in Kancipuram in Tamil Nadu flourished under the Pallava dynasty (fourth-late ninth century ce). Simultaneously, woodblock printing and dyeing workshops in South Asia produced less expensive substitutes for South-East Asia, Egypt, and West Africa. A group of seafaring Persians, Ethiopians, and Syrians traded in Chinese and Indian goods while the Chinese traded in lndo-China, Korea, India, and Ceylon from where her products reached Egypt, Eurasia, Persia, and the Byzantine Empire. Chinese raw silk was the most important single item of trade since the inception of the Roman Empire. Strategic geographic position of Persia enhanced trade with Syria and Byzantium that bought Chinese raw silk at inflated price till the fifth century. To maximize profit., the Soghdians in 550, like the Syrians of the Roman province, managed

Epilogue 249

to bypass both the Sasanian and Byzantine courts, and achieved great success in silk trade.[14] Their commercial interest was limited to the reselling of silk yarn and readymade raw silk from the Chinese to the merchants who supplied the Persians, Syrians, Byzantines, and Indians. The Sogdian cycle of mural paintings at Afrasiab in the so-called "hall of the ambassadors" represents not only their gorgeous silks and wealth but also their expectations in afterlife (2.22). The local ruler of Samarkand and Soghdiana, represented in the cycle of mural paintings, is identified as the governor (650-55 CE) sent by the Chinese emperor Gaozong (649-83 ce).[15] Efficient relay stations for the mounted messengers helped management of export and inter-regional trade. China imported from Syria precious and semi-precious stones and artificial glass gems. woven silk, wrought garments, and gold. Persia monopolized pearl and coral trade to China since these were important ingredients in Chinese magic potions and used as elixir of life in religious rituals. Iran's export to China also included wasma (woad âindigo) obtained from Egypt. In addition, the Persians sold enormous quantities of Persian brocades woven with Chinese yarn to meet the artificial demand created in Byzantium due to court restrictions. However, from mid-fifth to mid-sixth century CE Sasanian Iran suffered blockade by the Hephtalites rulers in Central Asia. The war with Byzantium for a century from 527 ce onwards was also a bleak period for the Sasanids (226-651 ce), when Turks made most of the embargo placed on Persian commodity by strengthening their hold on transit trade in silk combined with the traffic of dancing girls from Samarkand and Khotan. By taking control of the Silk Road the Turks benefited from direct trade with Byzantium and the Caspian regions. But these two vexing problems may ultimately be connected. One is the development of technology for its religious application in burial textiles and the recognition of the commercial advantage of the distribution of patterned silks in weft-faced compound weaves. Roger II of Sicily (1095-1154 CE), the nephew of Norman chief Guiscard, succeeded â¦

[14] Through the envoy led by Maniah the Sogdiarts at fiat sought free trade with Persia but it failed when Shah Khosro torched their silk in front of their eyes to prove that they had no need of the silk from the Sogdians or the Turks. The Sogdians were then encouraged by their Turkish rulers to negotiate directly with the Byzantines, the fiercest enemies of the Persians.

[15] Chavannes, Documenf Sur les Tou-kiue (Tyres) Occidentaux, SI. Petersburg, Ma 135. Quoted by Matteo Cornpareti, in Further Evidence for the interpretation of the 'Indian Scene' in the Pre-Islamic Paintings at Afrasiab (Samarkand).

https://www.exoticindiaart.com/book/d...

Sengupta, Arpurathani. 2018. The Silk Road Fabrics (The Stein Collection in the National Museum of India),

June 7, 2022

WOMAN AT THE WINDOW

ÎιάÏÏηÏη Ïλάκα εÏιÏλÏÏεÏÏ Î¼Îµ ' γÏ

ναίκα ÏÏο ÏαÏάθÏ

Ïο'[NOTE0]

ÎιάÏÏηÏη Ïλάκα εÏιÏλÏÏεÏÏ Î¼Îµ ' γÏ

ναίκα ÏÏο ÏαÏάθÏ

Ïο'[NOTE0]ÎΠΠΤΠÎΣÎÎ ÎΣÎÎΤΩΠΤÎÎ¥ Yair Zakovitch[NOTE1]

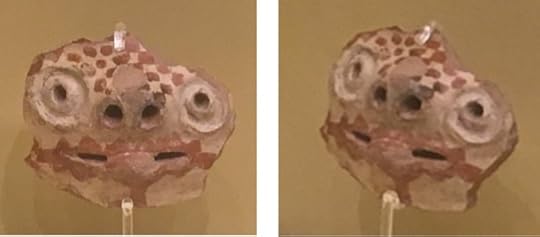

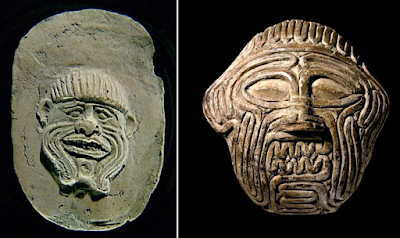

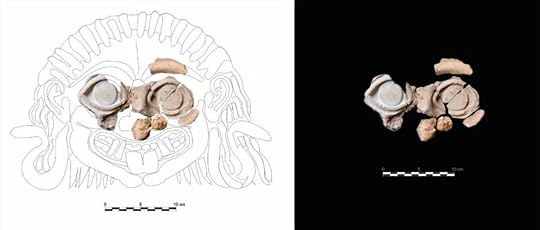

Îια άλλη Φοινικική ÏαÏάÏÏαÏη Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ±Ï ÏÏο ÏαÏÎ¬Î¸Ï Ïο, Î±Ï Ïή Ïη ÏοÏά Ïήλινο ομοίÏμα ιεÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ± ÏÏο ÏαÏÎ¬Î¸Ï Ïο, βÏÎθηκε ÏÏην νεκÏÏÏολη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ´Î±Î»Î¯Î¿Ï ÎÏÏÏÎ¿Ï .[10] Îίναι ενδιαÏÎÏον ÏÏι ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÎεÏαμοÏÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï (βιβλίο 14, γÏαμμÎÏ 696-7611, ο ÎÎ²Î¯Î´Î¹Î¿Ï Î±ÏηγείÏαι Ïην ιÏÏοÏίαâÏÎ¿Ï , ÏÏοÏθÎÏει, ήÏαν ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î³Î½ÏÏÏή Ïε Ïλη Ïην ÎÏÏÏο - ÏÎ·Ï ÎναξαÏÎÏηÏ, Î¼Î¹Î±Ï ÏÏιγκίÏιÏÏÎ±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î´Î¹Î±ÏοÏοÏÏε για Ïην αγάÏη ενÏÏ ÎµÏÏÏÎµÏ Î¼ÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î½ÎÎ¿Ï , ο δε αÏελÏιÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î½ÎµÎ±ÏÏÏ Î±Ï ÏοκÏÏνηÏε και, καθÏÏ Î· ÏÏιγκίÏιÏÏα ÎβλεÏε Ïην νεκÏική ÏομÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î± ÏεÏνά κάÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïο ÏαÏÎ¬Î¸Ï ÏÏ ÏηÏ, ολÏκληÏο Ïο ÏÏμα ÏÎ·Ï Îγινε ÏÎÏÏα,[11] Îνα άγαλμα ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏιγκίÏιÏÏαÏ, ÏÏοÏθÎÏει ο ÎβίδιοÏ, βÏίÏκεÏαι ÏÏην Σαλαμίνα. Î Anni Caubert[12] ενÏÏÏιÏε ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏÏÏÎµÏ ÎµÎ¼ÏανίÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎμαÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ±Ï ÏÏο ÏαÏÎ¬Î¸Ï Ïο Ïε ÎινÏικÎÏ ÏοιÏογÏαÏίεÏ[13] αÏÏ Ïην δεÏÏεÏη ÏιλιεÏία Ï.Χ., μαζί με ÏαÏαÏÏάÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î§Î¬Î¸Î¿Ï, ÏÎ·Ï ÎιγÏÏÏÎ¹Î±Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¬Ï ÏÏÏον ÏÎ¿Ï Î½Ï ÎºÏεÏÎ¹Î½Î¿Ï ÏÏον και ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Ï ÏÎ±Î½Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î·Î¼ÎÏÎ±Ï (ο δίÏÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ Î®Î»Î¹Î¿Ï Î¹ÏοÏÏοÏεί ανάμεÏα ÏÏα κÎÏαÏα ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î³ÎµÎ»Î¬Î´Î±Ï ÏÏο κεÏάλι ÏηÏ),[14] θεά ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏÏα και θεά ÏÏν νεκÏÏν.[15] ΠεικÏνα ÏÎ·Ï Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ±Ï ÏÏο ÏαÏÎ¬Î¸Ï Ïο ÏÏ Î½Î´Îθηκε ÏÏην Φοινικική ÏÎÏνη με Ïην ÏοÏνεία και Ïον κάÏÏ ÎºÏÏμο.[16] Τι είναι Î±Ï ÏÏ Î¼Îµ Ïη Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ± ÏÏο ÏαÏÎ¬Î¸Ï Ïο ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοκάλεÏε ÏÏÏο εÏίμονο ενδιαÏÎÏον; Î Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ± ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαÏκοÏεÏεÏαι αÏÏ Ïο ÏαÏÎ¬Î¸Ï Ïο βÏίÏκεÏαι μÎÏα ÏÏα ÏÏια ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î¯ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏηÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î¯ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ïαινομενικά ÏÏοÏÏαÏεÏει Ïην αγνÏÏηÏά ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïην ÏÏοÏÏαÏεÏει αÏÏ ÏεÏίεÏÎ³Î¿Ï Ï Î¬Î½Î´ÏεÏ. ΣημειÏÏÏε Ïη ÏÏ Î¼Î²Î¿Ï Î»Î® ÏÎ¿Ï Ben Sira ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏαÏÎÏÎµÏ ÏÏεÏικά με Ïη ÏÏλαξη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Ï ÏÏν κοÏιÏÏιÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Ï: «ΠÏοÏÎξÏε να μην Ï ÏάÏÏει δικÏÏ ÏÏÏ ÏλÎγμα ÏÏο δÏμάÏÎ¹Ï ÏηÏ, κανÎνα Ïημείο ÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î± βλÎÏει ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏοÏεγγίÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏιÏιοÏ» (42:11). {Î Ben Sira, εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î³Î½ÏÏÏÏÏ ÏÏ Shimon ben Yeshua ben Eliezer ben Sira ή Yeshua Ben Sirach, ήÏαν ελληνιÏÏικÏÏ ÎβÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï Î³ÏαμμαÏÎαÏ, ÏοÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏοÏήÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην ελεγÏÏμενη αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î£ÎµÎ»ÎµÏ ÎºÎ¯Î´ÎµÏ ÎεÏÎ¿Ï Ïαλήμ ÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î´ÎµÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î±Î¿Ï. Îίναι ο ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏÎÎ±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Sirach, εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î³Î½ÏÏÏÏÏ ÏÏ "Îιβλίο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎκκληÏιαÏÏικοÏ"} {Î ÎÏεν ΣίÏα γνÏÏÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏ Î£Î¹Î¼Ïν μÏεν ÎιεÏιοÏα μÏεν ÎλιÎÎ¶ÎµÏ Î¼Ïεν ΣίÏα (ש××¢×× ×× ×××שע ×× ××××¢×ר ×× ×¡×ר×) ή ο Yeshua Ben Sirach (ελεγÏÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον 2ο αιÏνα Ï.Χ. ÎλληνιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎεÏÏγιο, αÏÏ Ïον ΣελοκÏάÏο ÎεÏÏγιο και Ïον ΣελοκÏάÏοÏα), Ïην ÏεÏίοδο ÏÎ¿Ï Î´ÎµÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î±Î¿Ï. Îίναι ο ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏÎÎ±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Sirach, γνÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏ Â«Îιβλίο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎκκληÏιαÏÏικοÏ». ÎγÏαÏε Ïο ÎÏγο ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏα εβÏαÏκά, ÏιθανÏÏ ÏÏην ÎλεξάνδÏεια ÏÎ·Ï ÎιγÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏο Î ÏολεμαÏÎºÏ ÎαÏίλειο ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï . 180â175 Ï.Χ., ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎµÏÏείÏαι ÏÏι ίδÏÏ Ïε ÏÏολή} ÎÏÏ Ïην οÏÏική γÏνία ÏÎ·Ï Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ±Ï, ÏÏ Ïικά, ο Î¿Î¯ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏεÏιοÏίζει Ïην ÎµÎ»ÎµÏ Î¸ÎµÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ οι ÏοίÏοι ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ÏÎ¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ Ïον κÏÏμο ÏηÏ. Σε κάθε ÏεÏίÏÏÏÏη, Ïο ÏαÏÎ¬Î¸Ï Ïο καÏαλαμβάνει Îνα οÏÎ¹Î±ÎºÏ Ïημείο.

ÎμοίÏμα ιεÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ 'γÏ

ναίκα ÏÏο ÏαÏάθÏ

Ïο' (ÎÏ

ÏÏο - αÏÏÎ±Î¹ÎºÏ 600 - 475 Ï.Χ.) LOUVRE N III 3293 [NOTE5]

ÎμοίÏμα ιεÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ 'γÏ

ναίκα ÏÏο ÏαÏάθÏ

Ïο' (ÎÏ

ÏÏο - αÏÏÎ±Î¹ÎºÏ 600 - 475 Ï.Χ.) LOUVRE N III 3293 [NOTE5] ÎνάγλÏ

Ïο ÏÎ·Ï Butkara I με αÏεικÏνιÏη κÏ

ÏιÏν Ïε θεÏÏείο

ÎνάγλÏ

Ïο ÏÎ·Ï Butkara I με αÏεικÏνιÏη κÏ

ÏιÏν Ïε θεÏÏείοαÏÏÏÏαÏμα αÏÏ Ïο Î ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΣ Î ÎÎÎΤÎΣÎÎΣ ÎÎÎ ÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΣ ÎÎ ÎÎΡÎΣÎÎΣ[NOTE7]

ÎÏÏ ÏληθÏÏα ÏεκμηÏίÏν αÏοκαλÏÏÏεÏαι ÏÏι ο εÏιÏκÎÏÏÎ·Ï ÏÏν ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏÏικÏν ιεÏÏν ανÏιμεÏÏÏίζεÏο ÏÏι ÏÏ Î±ÏλÏÏ Î¸ÎµÎ±ÏÎ®Ï Î±Î»Î»Î¬ ÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÏÏÏÎ·Ï Î¼Î¬ÏÏÏ ÏÎ±Ï ÏÏ Î¼Î¼ÎµÏÎÏÏν Ïε μιάν αλληλεÏίδÏαÏη η οÏοία εÏεÏÏγÏανε Ïην ÎνÏαξή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏα ÏεκÏαινÏμενα και Ïην αÏοÏελεÏμαÏική καÏήÏηÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î½ÎÎµÏ Î¹Î´ÎεÏ.[7_225a1] ÎÏ ÏÏÏ Î¿ ÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏικοινÏÎ½Î¯Î±Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î®Î´Î· ÏιÏÏοÏÏ ÏÏον και ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÎ½ Î´Ï Î½Î¬Î¼ÎµÎ¹ είÏε ÏÏ ÏκοÏÏ Ïην αÏοÏελεÏμαÏική Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï Ïγία Î¼Î¹Î¬Ï ÎºÎ¿Î¹Î½ÏÏηÏÎ±Ï ÎµÎ½ÏεÏαγμÎÎ½Î·Ï ÏÏα νÎα ÏιÏÏεÏÏ, Ï ÏήÏξε δε αÏαÏαίÏηÏÎ¿Ï Î¹Î´Î¹Î±Î¯ÏεÏα λÏÎ³Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î³ÏαÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»ÏÎ³Î¿Ï .O ÏÏολιαζÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï ÎµÎ´Ï ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοÏλήÏεÏÏ Ï ÏοβάλλεÏαι ιδιαίÏεÏα ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î»ÎµÎ³ÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½ÎµÏ Î±ÏηγημαÏικÎÏ ÏκηνÎÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏεÏικÎÏ Î¼Îµ Ïην αναÏαÏάÏÏαÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î¶ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎοÏδα. Σε Î±Ï ÏÎÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ÏÏ Î½Î®Î¸Î·Ï Î· αÏεικÏνιÏη θεαÏÏν, ενÏÏÏ Î¸ÎµÏÏείÏν ή εÏί εξÏÏÏη, οι οÏοίοι ÏαÏÎ±ÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿Ï Î¸Î¿Ïν Ïα γεγονÏÏα ÏÏ ÎµÎ¬Î½ ÎµÏ ÏίÏκονÏο οι ίδιοι ÏÏο ÏÏοÏκήνιο και μάλιÏÏα δίÏλα ÏÏον ίδιο Ïον ÎοÏδα.[7_225a2] ΠενεÏγÏÏ ÏÏ Î¼Î¼ÎµÏοÏή ÏÏν θεαÏÏν Ïε κάÏοια ÎµÎ´Ï Ï ÏονοοÏμενη ÏαÏάÏÏαÏη Ï ÏογÏαμμίζεÏαι αÏÏ Ïα κομÏά ενδÏμαÏα και Ïα ÏεÏίÏεÏνα κοÏμήμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï Ïοί αÏεικονίζονÏαι να ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½, ÎµÎ½Ï Î· Ïκηνή ÏÏ Ïνά διακοÏμείÏαι αÏÏ Î±Î½Ïικείμενα Ï ÏÎ·Î»Î®Ï ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÏÏÏ Î±Î³Î³ÎµÎ¯Î±. Îε λίγα λÏγια η ÏαÏÎ¿Ï Ïία ÏÎ¿Ï âθεαÏή ενÏÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¹ÎºÏναÏâ ανÏαÏοκÏίνεÏαι Ïε μιαν οÏÏική ÏÏÏαÏηγική ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏιÏειÏεί να Ïον καÏαÏÏήÏει âÎ±Ï ÏÏÏÏη μάÏÏÏ Ïαâ εÏιÏÏ Î³ÏάνονÏÎ±Ï ÎÏÏι Ïην ÏÏνδεÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ Î±Ï ÏοÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎºÏÏοÏÏÏοÏνÏαι ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î±ÏηγημαÏικÎÏ ÏκηνÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï ÏγÏνÏÎ±Ï Î¼Î¹Î± νÎα κοινοÏική θÏηÏÎºÎµÏ Ïική κοινÏÏηÏα.

ΠαÏαÏηÏηÏÎÏ Î¸Î±Ï

μάζοÏ

ν ÏÏ

ÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏνεÏμα,[20]

ΠαÏαÏηÏηÏÎÏ Î¸Î±Ï

μάζοÏ

ν ÏÏ

ÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏνεÏμα,[20] ÎÎΥΠΤΠΤÎÎ¥ Î ÎÎÎ¥ÎÎΤÎΣ YAKSI ÏÏο ÎÎΥΣÎÎÎ LACMA[30]

Το ÏÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏνεÏμα (yaksi) εÏί ÎºÎ¯Î¿Î½Î¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î³ÎºÎ»Î¹Î´ÏμαÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î½Î®ÎºÎ¿Î½ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏην ÏÏ Î»Î»Î¿Î³Î® ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï Î¤ÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎομηÏÎµÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï ÎνÏζελεÏ, Ïο Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïο Î¼Î¹Î±Ï Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¹ÏÏεÏει Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïο γÏÏÏα (Îικ. 202) και Ïο αναθημαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î±Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î±Ïίδιο Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ±Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïο Faizabad (Îικ. 203) ανÏιÏÏοÏÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏαÏαδείγμαÏα Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¹ÎºÎµÎ¯Ïν μοÏÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏοδίδονÏαι με Ïην Ï ÏηλÏÏεÏη ÏοιÏÏηÏα, Ïιο ολοκληÏÏμÎνη καÏαÏÎºÎµÏ Î®, εÏάμιλλη με Î±Ï Ïή ÏÏν μοÏÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î»Ïνα Kathika. ÎÏοÏοÏν να ÏÏονολογηθοÏν ÏÏα μÎÏα ÎÏÏ Ïα ÏÎλη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î¹Ïνα Ï.Χ. λÏÎ³Ï ÏÏν Ï ÏολογικÏν ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏ Î³ÎºÎ±ÏαλÎγονÏαι μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï Î¼ÎµÏικÏν αÏÏ Ïα καλÏÏεÏα Î³Î»Ï ÏÏά ÏÏην ιÏÏοÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï Mathura.Το θÏαÏÏμα Î¼Î¹Î±Ï ÎºÎ¿Î»ÏÎ½Î±Ï Î±ÏÏ ÎºÎ¹Î³ÎºÎ»Î¯Î´Ïμα ή ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏαÏÏή, ανήκον ÏÏÏα ÏÏην ÏÏ Î»Î»Î¿Î³Î® ÏÎ¿Ï LACMA, αÏεικονίζει μια Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¹ÎºÎµÎ¯Î± μοÏÏή, θÏÎ±Ï ÏμÎνη κάÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïο εÏίÏεδο ÏÏν μαÏÏÏν. ΣÏο ÏÎÏι ÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏζεÏαι κÏαÏά Ïηλά Îνα κÏÏελλο Î¿Î¯Î½Î¿Ï , η μοÏÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î¼ÏοÏεί να ανιÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î¸ÎµÎ¯ ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÎÎÎÎÎÎΣΤÎÎÎΣ ÏηγÎÏ. O Pratapaditya Pal ÏÏÏÏθεÏε ÏÏι Ïο Î±Ï Î»Î±ÎºÏÏÏ ÎºÏÏελλο Î¿Î¯Î½Î¿Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏο ÏελεÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ³Î¹ÎºÏ bakula dohada, καÏά Ïο οÏοίο μια νεαÏή κοÏÎλα Ïεκάζει Ïο δÎνÏÏο bakula με οίνο αÏÏ Ïο ÏÏÏμα ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏοκειμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î½Î± Î±Ï Î¾Î®Ïει Ïην ικανÏÏηÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î± αÏοδίδει καÏÏοÏÏ.[39] ΣÏÎκεÏαι κάÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Îνα ανθιÏμÎνο δÎνÏÏο, κάÏι ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏοδηλÏνει ÏÏι είναι vrksadeata ή yaksi. ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î¬Î½Î´ÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ μια Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ± Ïην κοιÏÎ¬Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ με αÏοÏία και ÎκÏληξη ÏÎ¬Î½Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïο κιγκλίδÏμα (Îικ. 200).[40] ΠεικÏνα ÏÏο ÏÏÎ½Î¿Î»Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏην ομοÏÏιά ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÎ¸Î¿Î½Î¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï ÏαÏαγÏγικÏÏηÏÎ±Ï ÏÏμÏÏνα με ÏÎ¹Ï Î±ÏÏÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ¿ÏÎ¼Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏδαÏοÏ, ÏÎ·Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯Î±Ï Î¿Î¹ εικÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î³ÎμιÏαν ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÎ¾ÏÏεÏικοÏÏ ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏν ιεÏÏν μνημείÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÏαÏαδοÏÎ¹Î±ÎºÎ®Ï ÎνδίαÏ.Το ÏνεÏμα yaksi ÏÏÎκεÏαι Ï ÏÏ Î³Ïνία ÏÏ ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïον θεαÏή, με Ïο κεÏάλι ÏÎ·Ï Î½Î± γÎÏνει αÏαλά ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïην μία ÏÎ»ÎµÏ Ïά, ÏÏÏÏ Î· ανδÏική μοÏÏή ÏÏον ÏÏ Î»Ïνα κολÏνα Kathika (Îικ. 188), μια ÏÏάÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαίνεÏαι να ήÏαν δημοÏÎ¹Î»Î®Ï Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην ÏεÏίοδο. ΠμοÏÏή ÏÎ·Ï Î´Î¹Î±ÏοÏίζεÏαι αÏÏ Î¼Î¹Î± αίÏθηÏη ναÏÎ¿Ï ÏαλιÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÎµÎ¼ÏανοÏÏ ÏÏην αÏαλÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¼ÏÏλεÏ, ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ³ÎºÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏν Î¼Î¬Î³Î¿Ï Î»Ïν και ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ®Î¸Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïε λεÏÏομÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÏÏÏ Î· ελαÏÏιά αιÏÏηÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¿Î»Î¹Î´Î¹Î¿Ï Î¼Î±Î»Î»Î¹Ïν ÏÎ¬Î½Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïο μÎÏÏÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ Î±ÏάνÏηÏη ÏÏην κλίÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎµÏÎ±Î»Î¹Î¿Ï ÏηÏ. Τα ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ..

ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ[NOTE0]. Openwork furniture plaque with a "woman at the window", ca. 8th century B.C., MET 59.107.18.[NOTE1]. Yair Zakovitch 2019, p. 55.[NOTE5]. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:.... ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï Î. Ï ÏÏ Îκδ.[7_225a1]. ÎÎ´Ï Î³Î¯Î½ÎµÏαι αναÏοÏά ÏÏην θεÏÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏοÏλήÏεÏÏ - διανοηÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏ Î½Î±Î¹ÏθημαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï - ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏεÏÎ½Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ³Î¿Ï (Rezeptionsästhetik), βλ. Penzel 2020.[7_225a2]. Galli 2011, pp. 321-323, nn. 83, 84.[20] Onlookers admiring a Yakshi, Mathura, India, 20 BCE, <https://collections.lacma.org/node/24.... Sonya Rhie Quintanilla 2007, p. 160.

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎ

https://books.google.gr/books?id=Azhs...

Yair Zakovitch. 2019. The Song of Songs: Riddle of Riddles, London.

https://journals.openedition.org/cchy..., B. 2016. Maquettes antiques dâOrient. De lâimage au symbole, Picard, Paris, 2016, 296 pages, XIII pl., 176 figures, index, glossaire. ISBN 978-2-7084-1012-1Cahiers du Centre dâÃtudes Chypriotes, 47 | 2017, 344-346

https://www.academia.edu/44434211/MUL..., B. 2014. "'Architectural models' of the Near-East and Eastern Mediterranean: a Global Approach Introduction (Neolithic-Ist millenium BC) ," in Proceedings of the 8th ICAANE, ed. P. Bielinski, M. Gawlikowski, R. Kolinski, D. Lawecka, A. Soltysiak, Z. Wygnanska, pp. 123-149.

https://books.google.gr/books?id=rtqv... Rhie Quintanilla. 2007. History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE, Bosten / Leyden.

ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï Î. Ï ÏÏ Îκδ. Î ÎινεζικÏÏ ÏολιÏιÏμÏ; και οι ÎλλαδικÎÏ ÎµÏιδÏάÏειÏ, Îθήνα.

Î ÎÎÎΠΠΡÎÎΦÎΤÎΣ ÎÎÎ ÎÎΥΤÎΣÎÎΣ - ÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎ: 070622

May 29, 2022

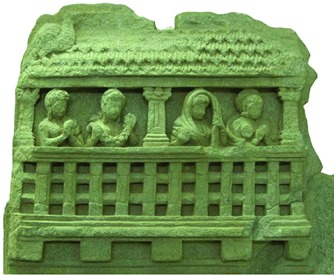

THE HITTITES AND THE AEGEAN WORLD, ed. 2022

ISBN 978-618-84901-6-1Î ÎÎÎÎÎΣ Î ÎΡÎÎΧÎÎÎÎΩΠΣÏνοÏη ..................................................................................................................................x ΠΡΩΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤΠ............................................................................................................ 1 1. Î âÎ±Î½Î±ÎºÎ¬Î»Ï Ïηâ ÏÏν ΧεÏÏαίÏν, οι ÏηγÎÏ.......................................................................1 ÎÎΥΤÎΡΠÎÎÎΤÎΤΠ.......................................................................................................3 2. Î âÏ ÏεÏÏονιÏμÏÏâ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î Î±ÏάγονÏα ÏÏην ÎÏμηνεία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î Î±ÏελθÏνÏÎ¿Ï ........................................................................................................................3 ΤΡÎΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ.............................................................................................................. 3. ÎÏηÏÏÏληÏαν οι ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±Î¯Î¿Î¹ Ïο ενδιαÏÎÏον ÏÏν ΧεÏÏαίÏν;......................................9 ΤÎΤÎΡΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ..................................................................................................... 4. Îξ ÎναÏολÏν Ïο ΦÏÏ; ................................................................................................... 13 Î ÎÎΠΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ...................................................................................................... 5. Îι ΧεÏÏαίοι: ÏÏνÏομη ÏÏνοÏη...................................................................................... 17 5.1 ÎλÏÏÏα - ΠολιÏική .................................................................................................17 5.2 ÎÏηÏκεία................................................................................................................ 20 5.3 ÎνÏιλήÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïον θάναÏο...................................................................................23 5.4 ÎεÏÎ±Î»Î»Î¿Ï Ïγία....................................................................................................... 28 ÎÎΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ............................................................................................................ 6. ÎνÏÏιζαν οι ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î§ÎµÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï Ï;....................................................................... 30 6.1 Îιγαίο και Î ÏνÏοÏ................................................................................................... 31 6.2 Îιλικική âÎÏαÎαâ - Que..........................................................................................33 6.3 ÎνομαÏικÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Î¬Î»Î»ÎµÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏοÏÎÏ.........................................................................37 6.4 ΣÏÏλια..................................................................................................................... 38 ÎÎÎÎÎÎ ÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ..................................................................................................... 40 7. Îι ÎλλαδίÏÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ η Î. ÎÏία ....................................................................................... 40 7.1 ÎÏ ÎºÎ»Î±Î´Î¯ÏÎµÏ â ÎινÏίÏÎµÏ - ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±Î¯Î¿Î¹ και η ÏαÏάλια Î. ÎÏία........................ 42 vii 7.1.1 ÎίληÏÎ¿Ï ........................................................................................................... 42 7.1.2 ÎολοÏÏν (Müsgebi)..................................................................................... 45 7.1.3 ÎενεμÎνη (Panaztepe)................................................................................ 45 7.1.4 ÎαÏÏÏ................................................................................................................ 46 7.1.5 ΤÏεÏμÎÏ........................................................................................................... 47 7.1.6 ÎνίδοÏ.............................................................................................................. 48 7.1.7 ΤÏοία................................................................................................................ 48 7.1.8 ÎÏεÏοÏ............................................................................................................ 50 7.1.9 ÎÎγαÏÏÎ¿Ï ........................................................................................................ 51 7.1.10 ÎλαζομενÎÏ .................................................................................................... 51 7.1.11 Îιλικία .............................................................................................................53 7.2 Îι Îιγαίοι και η ÎικÏαÏιαÏική ενδοÏÏÏα .........................................................55 7.2.1 ΧαÏοÏÏα ...........................................................................................................55 7.2.2 ÎÏ Ïική ÎναÏολία â ÎÏÎ¾ÎµÎ¹Î½Î¿Ï Î ÏνÏÎ¿Ï ..........................................................61 7.2.3 ÎναÏολική ÎναÏολία â AliÅar..................................................................... 65 7.3 Î£Ï Î¼ÏεÏαÏμαÏικά ÏÏÏλια......................................................................................66 ÎÎÎÎÎ ÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ......................................................................................................... 70 8. Î ÏαÏÎ¿Ï Ïία ÏÏν ÎλλαδιÏÏν ÏÏην Î£Ï Ïο -ΠαλαιÏÏίνη............................................. 70 8.1 Îι αÏαÏÏÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¹Î±ÎºÎ®Ï ÏαÏÎ¿Ï ÏίαÏ............................................................... 70 8.2 Ugarit...................................................................................................................... 76 8.3. Gezer ..................................................................................................................... 778.4 Tell Arad (Negev)................................................................................................80 8.5 Kumidi (Kamid el-Loz) .....................................................................................80 8.6 ÎινÏικÎÏ ÏοιÏογÏαÏίεÏ........................................................................................ 82 8.7 ΦιλιÏÏαÏκή μεÏανάÏÏÎµÏ Ïη................................................................................... 84 8.8 Îιγαιακά κÏαÏίδια ÏÏην Î£Ï Ïο â ΠαλαιÏÏίνη ................................................... 86 8.9 Îι ΦιλιÏÏαίοι καÏά Ïην Î¥ÎΧ............................................................................... 92 8.10 Îι Î¦Î¿Î¯Î½Î¹ÎºÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïο Îιγαίο.................................................................................. 95 8.10.2 Acco ή ÎκÏÏ ............................................................................................... 96 8.10.1 Arwad ή ÎÏÎ±Î´Î¿Ï (ÎÏάδην)........................................................................ 98 8.10.3 Tell Abu Hawam........................................................................................ 98 8.10.4 ΣιδÏν.................................................................................................................. 99 8.10.5 ÎÏβλοÏ.........................................................................................................102 8.10.6 ΣάÏεÏÏα (Sarepta)....................................................................................106 8.10.7 ÎαÏαληκÏικά ÏÏÏλια.................................................................................106 8.11 ΣÏνοÏη..................................................................................................................108 viii ÎÎÎÎΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ.......................................................................................................111 9. Îι Îιγαίοι και η ÎÏ ÏÏÏη καÏά Ïην ÎÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï: αÏÏ Ïον μÏθο ÏÏην (ÏÏο)ιÏÏοÏία.......................................................................................................................111 9.1 ÎβηÏική .................................................................................................................... 111 9.2 ÎαÏÏιÏεÏÎ¯Î´ÎµÏ ÎήÏοι..............................................................................................119 9.3 Σκανδιναβία ..........................................................................................................125 9.4 ÎενÏÏική ÎÏ ÏÏÏη ................................................................................................127 9.5 MαÏÏη ÎάλαÏÏα (ÏÏÏÏθεÏα ÏÏοιÏεία)............................................................132 9.6 Î ÎÏÏική ιδεολογία και η ÎÏ ÏÏÏαÏκή Îοινή ÎγοÏά ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï .........................................................................................................................135 9.7 Ex Oriente lux ενανÏίον Ex Occidente lux: κοινÏÏ ÏαÏονομαÏÏήÏ............138 ÎÎÎÎΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤΠ.....................................................................................................149 10. ÎÏαÏή ..........................................................................................................................149 10.1 ÎιγαιακÎÏ Î³ÏαÏÎÏ...............................................................................................149 10.2 ΧεÏÏιÏική γÏαÏή.................................................................................................157 10.3 ΧεÏÏιÏική ÏÏÏÎ±Î³Î¹Î´Î¿Î³Î»Ï Ïία ..............................................................................160 10.4 ΠΤαÏκÏνδημοÏ, ο αÏοδιοÏομÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÏÎ¬Î³Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ η Îλληνική ÏκÎÏη ..........164 10.4.1 Î ÏελεÏÎ¿Ï Ïγία ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏοδιοÏομÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÏÎ¬Î³Î¿Ï .........................................168 ÎÎÎÎÎÎΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ................................................................................................ 177 11. ÎÏ ÎºÎ¯Î± â Îιλικία: ÏεÏιÏÎÏεια ÏÏν ΧεÏÏαίÏν ή ενδιάμεÏη ÏεÏιοÏή;..................... 177 11.1 ÎÏ ÎºÎ¯Î±......................................................................................................................17711.2 Kizzuwatna .........................................................................................................179 11.3 TarhuntaÅ¡Å¡a .........................................................................................................181 ÎΩÎÎÎÎΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ...............................................................................................185 12. ÎÎ¾ÎµÎ¹Î´Î¹ÎºÎµÏ Î¼Îνοι εÏαγγελμαÏÎ¯ÎµÏ (η ÏεÏίÏÏÏÏη ÏÏν θεÏαÏÎµÏ ÏÏν)......................185 ÎÎÎÎΤΠΤΡÎΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ........................................................................................187 13. ÎμοιÏÏηÏÎµÏ Î¼ÎµÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î±Î´Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ΧεÏÏιÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¿Î´Î¿Î¼Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ αÏÏιÏεκÏÎ¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ............................................................................................................................................187 ÎÎÎÎΤΠΤÎΤÎΡΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤÎ.................................................................................193 14. ΣÏολιαÏμÏÏ ÏÏιÏμÎνÏν θεÏÏοÏμενÏν ÏÏ Î§ÎµÏÏιÏικÏν ÎÏγÏν ÏÎÏνηÏ.................193 14.1 Îενικά....................................................................................................................193 14.2 Î Î ÏÏÏÎ¼Î¿Ï âΧÏÏ ÏοÏÏ ÎιÏνâ ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏίÏÎ·Ï ÏιλιεÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ η ÎÎÏη ÎÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï .........................................................................................................................194 14.3 Alaca Hüyük......................................................................................................200 14.4 ÎεÏαμεικά Îγγεία.............................................................................................202 14.4.1 ÎάνθαÏοι......................................................................................................204 14.4.2 ÎÏÏÏαÏ........................................................................................................205 14.5 Î¡Ï ÏÏ ÏάÏÎ¿Ï IV ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Ïν..................................................................................208 14.6 ΠθεÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαιγίδαÏ.......................................................................................212 14.7 Î¡Ï ÏÏ Schimmel .................................................................................................. 213 14.8 ΣÏίγγεÏ................................................................................................................218 14.9 ÎÏÏληξη â λαβή ÏκήÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïα Îάλια .................................................. 222 14.10 ÎαÏαληκÏικά ΣÏÏλια ...................................................................................... 223 ÎÎÎÎΤΠΠÎÎΠΤΠÎÎÎΤÎΤΠ................................................................................ 229 15. Î£Ï Î¼ÏεÏάÏμαÏα.......................................................................................................... 229 ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ ................................................................................................................ 239 ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎ..............................................................................................................337 ÎÎÎÎÎÎΣ ........................................................................................................................460 ΣΥÎΤÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎΣ.................................................................................................... 472 ÎΥΡÎΤÎΡÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎΤΩÎ......................................................................................... 474

ΣÏνοÏη ΠκαθηγηÏÎ®Ï Muhly* δημοÏÎ¯ÎµÏ Ïε Ïo 1974 άÏθÏο με ÏίÏλο âThe Hittites and the Aegean Worldâ, ÏÏο ÏεÏÎ¹Î¿Î´Î¹ÎºÏ Expedition ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï ÎÏÏÎ±Î¹Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎνθÏÏÏÎ¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï ÏÎ·Ï Pennsylvania, ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏε ήÏαν εÏÎ¯ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸Î·Î³Î·ÏήÏ. Το άÏθÏο αναÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏην ΧεÏÏιÏική Î±Ï ÏοκÏαÏοÏία, μία ÏÏν μεγάλÏν Î´Ï Î½Î¬Î¼ÎµÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï 1700-1200 Ï.Χ., ÏμÏÏ Î±Î½ÏιμεÏÏÏίζει Ïην ιÏÏοÏική και ÏολιÏιÏÏική ÏαÏÎ¿Ï Ïία ÏÏν ÎιγαίÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ Ï ÏοÏιμηÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏÏÏο, ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î´ÎµÎ½ ÏÏ Î½Î¬Î´ÎµÎ¹ με Ïην αÏÏαιολογική και ιÏÏοÏική ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα. Îι Ï ÏοÏÏηÏιζÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÏο άÏθÏο αÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÎµÎ½ÏάÏÏονÏαι ÏÏο ÏεÏμα ÏÏν ÎναÏολιÏÏÏν, ήÏοι εκείνÏν οι οÏοίοι Ï ÏοÏÏηÏÎ¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ Ïο δÏγμα ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏολÏν ÏÏοελεÏÏεÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ διαδÏÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏολιÏιÏÎ¼Î¿Ï (ex oriente lux). Î ÏαÏοÏÏα εÏγαÏία ÏÏοÎÎºÏ Ïε αÏÏ Ïην ÏÏοÏÏάθεια αναÏÎºÎµÏ Î®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏαÏÎ¬Î½Ï Î¬ÏθÏÎ¿Ï , ÏμÏÏ Î±Î½ÎµÏÏÏÏθη ÏεÏαιÏÎÏÏ Î¼Îµ ÏκοÏÏ Î½Î± καλÏÏει ÏÏÏÏθεÏÎµÏ ÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¯Î´Î¹Î¿Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¼Î±ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Ïήνα. ÎÏÏι ÏεÏιλαμβάνει αναÏκÏÏηÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏεÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î²Î¹Î²Î»Î¹Î¿Î³ÏαÏίαÏ, ανάδειξη ÏÏοιÏείÏν και εÏÎ¼Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÏικÏν ÏÏημάÏÏν Ïα οÏοία δεν ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏοβληθεί εÏαÏκÏÏ Î® δεν είναι καλÏÏ Î³Î½ÏÏÏά, ενÏ, Ïε κάÏÎ¿Î¹ÎµÏ ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏειÏ, αÏοÏειÏάÏαι να ÏαÏάÏÏει μια νÎα εÏμηνεία â ÏÏοÏÎγγιÏη ÏÏν εγειÏÏμενÏν θεμάÏÏν. Îι ΧεÏÏαίοι, εμÏανιÏθÎνÏÎµÏ Î±Î¹ÏνιδίÏÏ ÏÏο ιÏÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏοÏκήνιο καÏά Ïην ÎÎÏη ÎÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï, δημιοÏÏγηÏαν μιά ιÏÏÏ Ïή Î±Ï ÏοκÏαÏοÏία με ÏÏ Ïήνα Ïην κενÏÏική ÎικÏά ÎÏία, η δε ÎºÏ ÏιαÏÏία και εÏιÏÏοή ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Ïά ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï Ï ÎµÏεκÏείνεÏο και άλλοÏε ÏÏ ÏÏικνοÏÏο ÏÏην κενÏÏική και αναÏολική ÎναÏολία. ÎνÎÏÏÏ Î¾Î±Î½ Îνα αξιÏλογο ÏÏÏÏημα διοικήÏεÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ γÏαÏειοκÏαÏίαÏ, καÏά ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï Ï Î´Îµ αÏκοÏÏαν Î±Ï Î¾Î·Î¼Îνη εÏιÏÏοή Ïε μια ÏειÏά Ï ÏοÏελÏν κÏαÏιδίÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏ ÏÏÏεÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏιοÏήÏ. Î Î±Ï ÏοκÏαÏοÏία ÏÏ Î½Î±ÏοÏελείÏο αÏÏ Îνα μÏÏαÏÎºÏ ÏÏ Î»ÎµÏικÏν και ÏοÏικιÏÏικÏν κοινοÏήÏÏν, οι οÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ Î¿Î¼Î¹Î»Î¿ÏÏαν διάÏοÏÎµÏ Î³Î»ÏÏÏÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ενεÏάνιζαν ÏημανÏική ÏολιÏιÏÏική διαÏοÏοÏοίηÏη. ΣÏα ÏλαίÏια ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏγαÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î³Î¯Î½ÎµÏαι καÏâ αÏÏήν αναÏοÏά ÏÏα ίÏνη ÏÏν ÎιγαίÏν ÏÏον Î ÏνÏο, Ïην ÏαÏάλια αλλά και Ïην ηÏειÏÏÏική ÎικÏά ÎÏία, ήδη ÏÏίν xi Ïην εμÏάνιÏη ÏÏν ΧεÏÏαίÏν. ÎδιαίÏεÏα αναÏÏÏÏÏονÏαι ÏÏοιÏεία ÏÏεÏικά με Ïην ÏαÏÎ¿Ï Ïία και δÏαÏÏηÏιοÏοίηÏη ÏÏν ÎλλαδιÏÏν ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î±ÎºÏÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎναÏÎ¿Î»Î¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïην Î£Ï Ïο â ΠαλαιÏÏίνη καÏά Ïην δεÏÏεÏη ÏιλιεÏία ÏÏίν αÏÏ Ïην εÏοÏή μαÏ, ÎµÎ½Ï Î³Î¯Î½ÎµÏαι εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏοÏά ÏÏην εÏίδÏαÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÏην Î±Î½Î¬Î´Ï Ïη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÏην ÎÏ ÏÏÏη. Î ÏολιÏική αλλά και άμεÏη ÏÏÏαÏιÏÏική εμÏλοκή ÏÏν ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±Î¯Ïν ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î±Î½ÏιÏαÏαθÎÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎικÏÎ¬Ï ÎÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î±Î½Î±Î´ÎµÎ¹ÎºÎ½ÏεÏαι με βάÏη ΧεÏÏιÏικÎÏ Î³ÏαÏÏÎÏ ÏηγÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ λοιÏά ÏεκμήÏια, ÎµÎ½Ï Î· ÏολιÏιÏÏική αλληλεÏίδÏαÏη μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¹Î±ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ®Î½Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎικÏÎ¬Ï ÎÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î±ÏοδεικνÏεÏαι ÏÏι ολίγον μÏνον Ï ÏολειÏÏÏαν Î±Ï ÏÎ®Ï Î¼Îµ Ïην ÏαÏάλια ÎναÏολία.. ÎδιαίÏεÏα ÏÏολιάζονÏαι καλλιÏεÏνικά ÎÏγα Ïα οÏοία ÏÏ Î½Î®Î¸ÏÏ Î±ÏοδίδονÏαι ή, ÎÏÏÏ, ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίζονÏαι με ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î§ÎµÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï Ï, ÏαÏÎÏονÏαι δε ÏÏοιÏεία Ïα οÏοία Ïε Î¬Î»Î»ÎµÏ ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην καθιεÏÏμÎνη άÏοÏη, Ïε Î¬Î»Î»ÎµÏ Î´Îµ ενÏοÏÎ¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ και Ï ÏογÏÎ±Î¼Î¼Î¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ Ïην ÏÏαÏξη Ïε Î±Ï Ïά ÎιγαιακÏν ÏÏοιÏείÏν Ïα οÏοία ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ αÏοÏιÏÏηθεί! ÎκÏιμάÏαι ÏÏι η ÏÏ Î½Î¿ÏÏική Î±Ï Ïή Î±Î½Î¬Î»Ï Ïη ÏαÏÎÏει μια ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏον ολοκληÏÏμÎνη και ανÏικειμενική εικÏνα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î±Î´Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏολιÏιÏμοÏ, ÏÎ·Ï Î¸ÎÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏον κÏÏμο ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏν εÏιÏÏοÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï ÏÏÏ Î¬ÏκηÏε εÏί ÏÎ¿Ï Î§ÎµÏÏιÏικοÏ, ÏÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏν εÏιδÏάÏεÏν ÏÎ¹Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ ÎµÎ´ÎÏθη αÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÏν. Σε ÏÏÏιÏÏÎÏ ÎµÏγαÏίεÏ, αλλά ÏÏα ÏλαίÏια ÏÎ·Ï Î¯Î´Î¹Î±Ï ÏειÏάÏ, αναλÏονÏαι οι άλλοι μεγάλοι ÏολιÏιÏμοί ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏοÏήÏ: ο ÏολιÏιÏμÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎακÏÏÎ¯Î±Ï â ÎαÏγιανήÏ, ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ¿Î¹Î»Î¬Î´Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎνδοÏ, ο ÎÎ¹Î³Ï ÏÏιακÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ο ÎινεζικÏÏ, ÏάνÏα εν ÏÏÎÏει με ÏÎ¹Ï ÎλλαδικÎÏ ÎµÏιδÏάÏειÏ. ÎλÏίζεÏαι ÏÏι ÏαÏÎÏεÏαι ÎÏÏι μια ÏληÏÎÏÏεÏη εικÏνα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏολιÏιÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¯Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏν ÏÏÎÏεÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¬Î»Î»Î¿Ï Ï Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»Î¿Ï Ï ÏÏγÏÏÎ¿Î½Î¿Ï Ï ÏολιÏιÏμοÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï, αÏηλλαγμÎνη - ÏÏο μÎÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Ï Î½Î±ÏÎ¿Ï - αÏÏ ÏÏοκαÏαλήÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ιδεοληÏίεÏ.

May 17, 2022

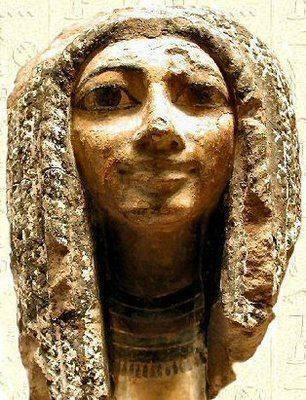

EARLY EGYPTIAN CIVILISATION AND ITS AEGEAN AFFINITIES

ΠΠΡΩÎÎÎΣ ÎÎÎΥΠΤÎÎÎÎΣ Î ÎÎÎΤÎΣÎÎΣ ÎÎÎ ÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎ ÎÎΡÎΣÎÎΣ ÎΠΤΠÎÎÎÎÎÎ

βâ εÏÎ·Ï Î¾Î·Î¼Îνη ÎκδοÏη

[image error]

https://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeumdok/5337/

May 11, 2022

Marsia, Platone, Dante, Giovanni di Paolo: alcune considerazioni in merito ad una miniatura dantesca, Giulio Coppola

ÎÏ Ïή είναι η ÏεÏίÏημη ανÏίθεÏη μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÏν Î±Ï Î»Î·ÏÏν (ανÏιÏÏοÏÏÏÎµÏ Î¿Î¼ÎνÏν αÏÏ Ïον ÎαÏÏÏα) και ÏÏν κιθαÏÏδÏν (Ï ÏÏ Ïην αιγίδα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏλλÏνοÏ), μια διαλεκÏική ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ½ÏάÏÏεÏαι ÏÏον ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÏοβλημαÏιÏÎ¼Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïα αÏοÏελÎÏμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοκαλεί η Î¼Î¿Ï Ïική ÏÏην ÏÏ Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÎºÏοαÏή. ΣÏο ÏκεÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏηÏίζει ο ΣÏκÏάÏÎ·Ï ÏÏην ΠολιÏεία,[35] αÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¾ÎÏαÏε ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î´Î¹Î¬ÏοÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï á¼ÏÎ¼Î¿Î½Î¯Î±Ï (Î¼ÎµÎ¹Î¾Î¿Î»Ï Î´Î¹ÎºÎ®, ÏÏ Î½ÏÎ¿Î½Î¿Î»Ï Î´Î¹ÎºÎ®, ιÏνική, Î»Ï Î´Î¹ÎºÎ® κ.λÏ.) με ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏεÏικÎÏ ÏÏ Î½ÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±ÎºÏοαÏÎÏ, αÏαγοÏεÏεÏαι η ÏÏÏÏβαÏη ÏÏην ιδανική ÏÏλη Ïε οικοδÏÎ¼Î¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏλογÎÏαÏ. ÏÏÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ Ïο ÏÏγανο εξαιÏεÏικά ÎµÏ ÎλικÏο και Î¹ÎºÎ±Î½Ï Î½Î± Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï Ïγεί ÏολλαÏλÎÏ Î±ÏÎ¼Î¿Î½Î¯ÎµÏ Î¹ÎºÎ±Î½ÎÏ Î½Î± αναÏÏαÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î½ ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏ ÏÎÏ.[36] Το κλείÏιμο ÏÎ·Ï ÏκÎÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î£ÏκÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï [37] είναι εξαιÏεÏικά ÏημανÏικÏ:

Îá½Î´Îν γε, ἦν δ᾽ á¼Î³Ï, καινὸν Ïοιοῦμεν, ὦ Ïίλε, κÏίνονÏÎµÏ Ïὸν á¼ÏÏÎ»Î»Ï ÎºÎ±á½¶ Ïá½° Ïοῦ á¼ÏÏλλÏÎ½Î¿Ï á½Ïγανα ÏÏὸ ÎαÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïε καὶ Ïῶν á¼ÎºÎµÎ¯Î½Î¿Ï á½ÏγάνÏν.ήÏοι:

Îαι δε Î¼Î¿Ï ÏαίνεÏαι να κάνομε και ÏίÏοÏα ÏεÏίεÏγο ÏÏάγμα, Ïίλε Î¼Î¿Ï , αν ÏÏοÏιμοÏμε Ïον ÎÏÏλλÏνα και Ïα ÏÏγανα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏλλÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον ÎαÏÏÏα και Ïα ÏÏγανά ÏÎ¿Ï .[37a]

ΣκαÏίÏημα ÏαÏαÏÏάÏεÏν αÏÏ ÎºÏαÏήÏÎ±Ï Î¿Î¯Î½Î¿Ï

hu με ÎνθεÏη διακÏÏμηÏη ÏεÏιλαμβάνοÏ

Ïα αÏ

ληÏή ÏÏο β' διάζÏμα[900]

ΣκαÏίÏημα ÏαÏαÏÏάÏεÏν αÏÏ ÎºÏαÏήÏÎ±Ï Î¿Î¯Î½Î¿Ï

hu με ÎνθεÏη διακÏÏμηÏη ÏεÏιλαμβάνοÏ

Ïα αÏ

ληÏή ÏÏο β' διάζÏμα[900]The traditional favor accorded to stringed instruments over wind instruments is therefore reaffirmed. In this perspective, Aristotle comes to 'interpret' in this way the particular present in the myth according to which Athena, after having invented the aulos, gets rid of it[38]: ..

Î ÏαÏαδοÏιακή Ï ÏεÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î½Î±Î³Î½ÏÏιζÏÏαν ÏÏα ÎγÏοÏδα ÏÏγανα ÎνανÏι ÏÏν ÏÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÏÏν εÏιβεβαιÏνεÏαι εκ νÎÎ¿Ï . Σε Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην ÏÏοοÏÏική, ο ÎÏιÏÏοÏÎÎ»Î·Ï ÎÏÏεÏαι να «εÏμηνεÏÏει» με Î±Ï ÏÏν Ïον ÏÏÏÏο Ïο ιδιαίÏεÏο ÏαÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÏÎ¸Î¿Ï ÏÏμÏÏνα με Ïο οÏοίο η Îθηνά, αÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏηÏÏε Ïον Î±Ï Î»Ï, Ïον αÏοÏÏίÏÏει, Arist. Pol. 8. 1341b:[38]

..εá½Î»ÏγÏÏ Î´á¾½ á¼Ïει καὶ Ïὸ ÏεÏὶ Ïῶν αá½Î»á¿¶Î½ á½Ïὸ Ïῶν á¼ÏÏαίÏν Î¼ÎµÎ¼Ï Î¸Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î·Î¼Îνον. ÏαÏὶ Î³á½°Ï Î´á½´ Ïὴν á¼Î¸Î·Î½á¾¶Î½ εá½ÏοῦÏαν á¼Ïοβαλεá¿Î½ ÏÎ¿á½ºÏ Î±á½Î»Î¿ÏÏ. Î¿á½ ÎºÎ±Îºá¿¶Ï Î¼á½²Î½ οá½Î½ á¼Ïει Ïάναι καὶ διὰ Ïὴν á¼ÏÏημοÏÏνην Ïοῦ ÏÏοÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏοῦÏο Ïοιá¿Ïαι Î´Ï ÏÏεÏάναÏαν Ïὴν θεÏν: οὠμὴν á¼Î»Î»á½° μᾶλλον Îµá¼°Îºá½¸Ï á½ Ïι ÏÏá½¸Ï Ïὴν διάνοιαν οá½Î¸Îν á¼ÏÏιν ἡ Ïαιδεία Ïá¿Ï αá½Î»Î®ÏεÏÏ, Ïῠδὲ á¼Î¸Î·Î½á¾· Ïὴν á¼ÏιÏÏήμην ÏεÏιÏίθεμεν καὶ Ïὴν ÏÎÏνην.ήÏοι

Îαι ÏÏάγμαÏι Ï ÏάÏÏει μια λογική βάÏη για Ïην ιÏÏοÏία ÏÎ¿Ï Îλεγαν οι αÏÏαίοι για Ïον Î±Ï Î»Ï. ΠμÏÎ¸Î¿Ï Î»Îει ÏÏι η Îθηνά βÏήκε Îναν Î±Ï Î»Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïον ÏÎÏαξε. ΤÏÏα δεν είναι ÎºÎ±ÎºÏ ÏÏην ιÏÏοÏία ÏÏι η θεά Ïο Îκανε Î±Ï ÏÏ Î±ÏÏ ÎµÎ½ÏÏληÏη λÏÎ³Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¬ÏÏÎ·Î¼Î·Ï ÏαÏαμοÏÏÏÏεÏÏ ÏÏν ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικÏν ÏηÏ. αλλά ÏÏην ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα είναι Ïιο ÏÎ¹Î¸Î±Î½Ï Î½Î± οÏείλεÏαι ÏÏο ÏÏι η εκÏÎ±Î¯Î´ÎµÏ Ïη ÏÏον Î±Ï Î»Ï Î´ÎµÎ½ εÏηÏεάζει Ïην νοημοÏÏνη, ÎµÎ½Ï ÏÏην Îθηνά αÏÎ¿Î´Î¯Î´Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ εÏιÏÏήμη και ÏÎÏνη.[38a]