Dimitrios Konidaris's Blog

August 26, 2025

Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez and Greater Greece

Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez & ÎείζÏν ÎλλάÏεÏανίÏμαÏα

Before reaching the final line, however, he had alreadyunderstood that he would never leave that room,for it was foreseen that the city of mirrors (or mirages)would be wiped out by the windand exiled from the memory of men at the precise momentwhen Aureliano Babilonia would finish deciphering theparchments, and that everything written on them wasunrepeatable since time immemorial and forever more,because races condemned to one hundred years of solitudedid not have a second opportunity on earth(Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude, translation by G. Rabassa) [1]

Îια ενανÏιοδÏομία â η ελληνική Îννοια ÏÏν ÏÏαγμάÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÎµÏαÏÏÎÏονÏαι ÏÏο ανÏίθεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï â ÏÏÎÏει να λάβει ÏÏÏα, και Î±Ï Ïή δεν είναι μια εÏκολη διαδικαÏία εÏειδή Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¿Î·Î³Î¿Ï Î¼ÎνÏÏ Î¸ÎµÏÏοÏνÏαν ÏÏ Îνα ÏÏνολο αÏληÏÏίαÏ, λαγνείαÏ, ÏÎ¬Î»Î·Ï Î³Î¹Î± ÎµÎ¾Î¿Ï Ïία και αÏÏ Î½ÎµÎ¯Î´Î·ÏÏν αÏνηÏικÏν (δηλαδή, ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏμαÏοÏ) ÏÏÎÏει ÏÏÏα να ανακληθεί. Î Î±Î½Î¬Î´Ï Ïη Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ÎÎ¹Î¿Ï Î½Î³Îº ÏεÏιÎγÏαÏε ÏÏ Â«Îνα αÏÏ Î½ÎµÎ¯Î´Î·Ïο ανÏίθεÏο ÏÏην ÏοÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï Â» ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏάγεÏαι ή αÏαιÏεί Ïην ανÏιμεÏÏÏιÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ±Ï ÏοÏ, κάÏι ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î¼Î²Î±Î¯Î½ÎµÎ¹ αÏÏ ÎºÎ¬Î¸Îµ άÏοÏη ÏÏο ÎκαÏÏ Î§ÏÏνια ÏÏαν, μÏÎ½Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏ Î½Î±Î¹ÏθημαÏικά αÏοδιοÏγανÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον θάναÏο ÏÎ·Ï ÎμαÏάνÏα ÎÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î±, ο ÎÏ ÏηλιανÏÏ ÏÏÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏα ÏειÏÏγÏαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎελÏιάδη (ÎÎ¹Î¿Ï Î½Î³Îº, ÎÏανÏα: ÎÏο Îοκίμια, 72). ÎνακαλÏÏÏει, εÏιÏÎÎ»Î¿Ï Ï, ÏÏι Ïο ÏειÏÏγÏαÏο ÏεÏιÎÏει Ïην ιÏÏοÏία ÏÎ·Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¿Î³ÎÎ½ÎµÎ¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ¿Ï . Το εÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏν ÎÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ½Î´Î¯Î± ÏεÏιλαμβάνει, ÏÏ Ïικά, ÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î»ÎµÏÏομÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏÎ³Î®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏ ÏηλιανοÏ, λεÏÏομÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏÎμειναν Î¼Ï ÏÏήÏιο γι' Î±Ï ÏÏν μÎÏÏι εκείνο Ïο Ïημείο. ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î¬Î¸ÎµÎ¹ Ïην ÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÏηÏά ÏÎ¿Ï , ο ÎÏ ÏÎ·Î»Î¹Î±Î½Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏά ÏÏην ανάγνÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¶ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην αÏÏή. Îε άλλα λÏγια, ÎÏονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÏÏα εÏιÏÏÏει μια ÏÏ Î³ÏÏÎ½ÎµÏ Ïη με Ïην AMAR και ÏÏη ÏÏ Î½ÎÏεια Ïην αÏÏλεÏε, ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÎÏει να εÏιÏÏÏÎÏει ÏÏον ÎµÎ±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï , να θÎÏει μÏÏοÏÏά ÏÏα μάÏια ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î»ÏκληÏη Ïην ÏÏοηγοÏμενη ζÏή ÏÎ¿Ï .ÎεμελιÏÎ´Î·Ï ÏÏÏο για ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î£ÏÏικοÏÏ ÏÏο και για ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎÏικοÏÏÎµÎ¹Î¿Ï Ï, η γνÏÏη, ή, ακÏιβÎÏÏεÏα, η ÏÏονÏίδα, ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ εξίÏÎ¿Ï ÏημανÏική ÏÏο Îεγάλο ÎÏγο ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î»ÏημείαÏ. ΣÏην ÎλεξανδÏινή ÏÏαγμαÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏάÏη {ÏÎ¿Ï ÎαλλÏÏη}, η ÏÎλεια γνÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ®Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ Î±Ï Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÎÏει ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÎ¹Î´Î¹ÎºÎ¿ÏÏ Î½Î± καÏανοήÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïα διαÏοÏεÏικά ονÏμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¯Î½Î¿Ï Î½ οι ÏιλÏÏοÏοι ÏÏην αÏÏκÏÏ Ïη Î¿Ï Ïία (..). Î ÎÏ ÏηλιανÏÏ ÎÏαμÏιλÏνια είναι Ïο μÏνο μÎÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¿Î³ÎÎ½ÎµÎ¹Î±Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ½Î´Î¯Î± ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Ïθηκε η ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹Ïία να γνÏÏίÏει Ïον ÎµÎ±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï , μια Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ¬Î»Ï Ïη ÏÎ¿Ï , ÏÏÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î´Î±Î¼Îµ, Îγινε ÏÏη γλÏÏÏα ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î»ÏημείαÏ. ÎÏοÏÏÏνÏÎ±Ï Î³Î½ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î³Î¹Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏογÏÎ½Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸ÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ για Ïην καÏαγÏγή ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïα ÏειÏÏγÏαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Îελκιάδη, Ïα οÏοία μÏοÏεί ξαÏνικά να διαβάÏει «ÏÏÏÎ¯Ï Ïην ÏαÏαμικÏή Î´Ï Ïκολία, Ïαν να ήÏαν γÏαμμÎνα ÏÏα ιÏÏανικά», ο ÎÏ ÏηλιανÏÏ Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Î»ÏÏÏει Ïην ολÎθÏια ÏÏ Î¼ÏÏνία ÏÎ·Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¿Î³ÎÎ½ÎµÎ¹Î±Ï Î¼Îµ Ïη μοναξιά (..).58 Î ÏÏ Î½Î± Î±ÎºÏ ÏÏÏει Î±Ï Ïή Ïη ÏÏ Î¼ÏÏνία είναι Ïο εÏÏÏημα ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎÏει ÏιÏÏηÏά Ïο Î¼Ï Î¸Î¹ÏÏÏÏημα Ïε ÏÎ»Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±Î½Î±Î³Î½ÏÏÏεÏ. ÎÏοι θÎÎ»Î¿Ï Î½ να βÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην αÏάνÏηÏη ÏÏÎÏει να ξεκινήÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏίÏνονÏÎ±Ï Î¼Î¹Î± ÏκληÏή, ανÎκÏÏαÏÏη μαÏιά μÎÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Ï. Îν είναι ειλικÏινείÏ, λÎει ο ÎάÏκεÏ, θα Î´Î¿Ï Î½ ÏÏι η Ïίζα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοβλήμαÏÏÏ Î¼Î±Ï ÎγκειÏαι Ïε μια ÏÏεδÏν ÏλήÏη άγνοια Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏει μεγαλÏÏεÏη ÏημαÏία. Φαινομενικά, ανÏλÏνÏÎ±Ï Ïο εÏÎθιÏμά ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην ÏλαÏÏνική ÏκÎÏη ÏÏÏÏ ÎµÎºÏÏάζεÏαι ÏÏο ÏÎÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Îλκιβιάδη, ο ÎκαÏθία ÎάÏÎºÎµÏ Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζει ÏÏι Ïο ÏÏÏβλημα για Ïην αÏομική ÏÏ Ïή είναι να αναγνÏÏίÏει Ïον ÎµÎ±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï Ïε Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ (ÎκαÏÏ Î§ÏÏνια 588â95). Πηθική και ÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î¼Î±Ïική ανάÏÏÏ Î¾Î· είναι ÏÏ Î½ÎÏεια ÏÎ·Ï Î±Ï ÏογνÏÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏοÏÏÏθεÏη για Ïην καÏανÏηÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎµÎ¹Î¼ÎÎ½Î¿Ï : Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ÎÏ Î³Î¿Ï ÏÏÎ¯Î½Î¿Ï Î±Ïοκαλεί quis facit veritatem, «να ÎºÎ¬Î½ÎµÎ¹Ï Ïην αλήθεια μÎÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Â» (243).

One Hundred Years of Solitude and The Creation of Latin American Mythology "Arcadio" is a specific reference to the Greek region of Arcadia. From the wiki: "It is situated in the central and eastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. It takes its name from the mythological figure Arcas. In Greek mythology, it was the home of the god Pan. In European Renaissance arts, Arcadia was celebrated as an unspoiled, harmonious wilderness." https://www.reddit.com/r/literature/c...

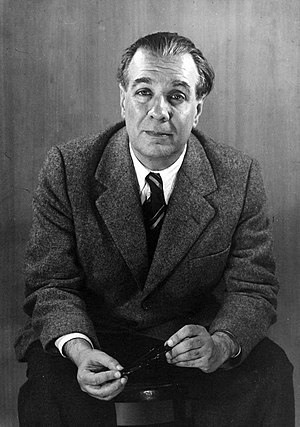

Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez and the Greek and Latin classics[5]...In his autobiography "Living to Tell the tale" makes clear references to the importance of knowledge of the classics. So in chapter 6, recalls, referring to his friend Gustavo Ibarra Merlano:

The thing that bothered him about me was my dangerous contempt for the Greek and Latin classics, which I found boring and useless, except for the Odyssey, that I had read and reread to pieces several times in high school. So before you say goodbye, he chose a bound leather book from his library and gave it to me with a certain solemnity. "You could become a good writer-he said- but you'll never be very good if you do not know well the Greek classics." The book was the complete works of Sophocles. Gustavo was from that moment one of the key persons in my life, because Oedipus is revealed to me in the first reading as the perfect work.

In One Hundred Years of Solitude he recreates the myth of Prometheus chained as punishment from the gods for having given fire to men for their progress. José Arcadio BuendÃa also tried to create a new society and so Macondo born.Also in One Hundred Years of Solitude he recreates the myth of Teuth by Plato about the value of writing, character that reminds us Melquiades of Hundred Years of Solitude; to the subject of the invention of writing is dedicated precisely the previous article in this blog

"Magic in Service of Truth"[10]"Magic in Service of Truth" refers to the literary technique of magical realism, where fantastic or supernatural elements are integrated into a realistic setting. This approach, particularly associated with Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez and his novel "One Hundred Years of Solitude," uses magic to enhance the emotional and dramatic impact of the narrative, making it more real rather than less. By blending the ordinary with the extraordinary, magical realism explores complex themes of history, politics, and human experience.Key aspects of "Magic in Service of Truth":Blending the Real and the Magical:Magical realism blurs the lines between the mundane and the supernatural, presenting fantastical events as commonplace within a realistic world.Enhancing Emotional Impact:The magic in these stories is not merely decorative; it serves to amplify the emotional resonance of the narrative, adding depth and meaning to the characters' experiences and the story's themes.Exploring Reality through Fantasy:Magical realism uses fantastical elements to examine and critique reality, often offering a unique perspective on history, politics, and social issues.Beyond Escapism:Unlike fantasy, which creates entirely separate worlds, magical realism roots itself in reality and uses magic to illuminate and reimagine the world as it is.Examples in Literature:One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez:The novel's depiction of events like a woman ascending to heaven, ghosts returning, and a priest levitating, presented alongside the historical and political realities of Latin America, exemplifies magical realism's power to enrich and deepen the narrative.Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel:This novel uses food as a metaphor for love and passion, and magical realism helps to portray the beauty of family life and bring political concerns to the forefront.In essence, "Magic in Service of Truth" describes how magical realism uses the fantastic to reveal deeper truths about the human condition and the world around us, making the familiar strange and the strange familiar.--

ξÏÏÏ

λλο ÏοÏ

μÏ

θιÏÏοÏήμαÏÎ¿Ï "ÎκαÏÏ Î§ÏÏνια ÎοναξιάÏ" (Cien años de soledad) ÏοÏ

ÎκαμÏÏιÎλ ÎκαÏÏία ÎάÏκεÏ.

ξÏÏÏ

λλο ÏοÏ

μÏ

θιÏÏοÏήμαÏÎ¿Ï "ÎκαÏÏ Î§ÏÏνια ÎοναξιάÏ" (Cien años de soledad) ÏοÏ

ÎκαμÏÏιÎλ ÎκαÏÏία ÎάÏκεÏ.

ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ[1]. Pallavidini 2025. Îλ. εÏίÏÎ·Ï Ïον ÏÏολιαÏμÏ: https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/solitu... ÎÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¯ η ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI:ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI

The final line of Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez's "One Hundred Years of Solitude" describes the ultimate fate of Macondo, the town, and Aureliano Babilonia, the decipherer of the parchments. The city is destined to be destroyed by wind and forgotten, and Aureliano's deciphering of the parchments, which foretold this fate, will coincide with the city's demise, signifying the end of their shared history. Here's a more detailed breakdown: Aureliano Babilonia's Understanding:Aureliano, before finishing the last line of the parchments, understands that his fate and the city's are intertwined and irreversible.The City's Foretold Destruction:The parchments reveal that Macondo, a city built on mirrors and illusions, is destined to be wiped out by the wind and erased from human memory.Deciphering the Parchments:The act of deciphering the parchments is not just a task but a catalyst. The city's destruction is linked to the completion of this act.Irreversible Fate:The parchments also reveal that the events foretold within them are unrepeatable, emphasizing the cyclical and ultimately tragic nature of the BuendÃa family and Macondo's history.One Hundred Years of Solitude:The phrase "races condemned to one hundred years of solitude" refers to the cyclical and ultimately doomed nature of the BuendÃa family's history, where they repeat the same patterns of love, betrayal, and isolation.[5]. MartÃnez 2014.[10]. ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI <https://www.google.com/search?q=%22Ma...». εÏίÏηÏ: Subhas Yadav 2016.ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎhttps://www.degruyterbrill.com/docume..., M. 2025. (A)synchronic (Re)actions. Crises and Their Perception in Hittite History (Chronoi 14), ed. E. Cancik-Kirschbaum, C. Markschies and H. Parzinger), Einstein Center Chronoi, De Gruyter.

https://dokumen.pub/qdownload/the-oxf...

René Prieto. 2021. "Repetition and Alchemy in One Hundred Years of Solitude," in The Oxford Handbook of Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez, ed. G. H. Bell-Villada and I. López-Calvo, pp. 391â412.

https://dn790002.ca.archive.org/0/ite... GARCIA MARQUES. 1970. ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, trans. GREGORY RABASSA, AVON BOOKS â NEW YORK.

https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/solitu...

https://www.antiquitatem.com/en/origi..., Î. Î. 2014. "Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez and the Greek and Latin classics," antiquitatem, s.v. History of Greece and Rome, <https://www.antiquitatem.com/en/garci... (8 Aug. 2025).

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR)Vol-2, Issue-5, 2016ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.inImperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Page 929

Subhas Yadav. 2016. "Magic Realism and Indian Aesthetics: An Attempt to Analyse âA Very Old Man with Enormous Wingsâ," Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) 2 (5), pp. 929-936.

https://jjalltheway.medium.com/the-la..., J. J. 2017. "The Last Reader of One Hundred Years of Solitude," Medium, <https://jjalltheway.medium.com/the-la... (11 August 2025).

http://www.antiquitatem.com/en/garcia... would almost say that Oedipus Rex was the first great intellectual shock of my life. I already knew I would be a writer and when I read that, I said, " This is the kind of things I want to write." I had published some stories and , while working as a journalist in Cartagena , was trying to see if I could finished a novel. I remember one night talking about literature with a friend, Gustavo Ibarra Merlano , who besides being a poet, is the man who knows more in Colombia on customs duties â and comes and tells me: " You'll never amount to anything until you read the Greek classics . " I was very impressed , so that night I walked his home and put me in the hands a volume of Greek tragedies. I went to my room , I slept , I started reading the book to the first page â Oedipus was just â and I could not believe . He read , and read , and read â started about two in the morning and it was already dawning â and the more I read the more I wanted to read . I think that since then I have not stopped reading this blessed work . I know it by heart .

Before reaching the final line, however, he had alreadyunderstood that he would never leave that room,for it was foreseen that the city of mirrors (or mirages)would be wiped out by the windand exiled from the memory of men at the precise momentwhen Aureliano Babilonia would finish deciphering theparchments, and that everything written on them wasunrepeatable since time immemorial and forever more,because races condemned to one hundred years of solitudedid not have a second opportunity on earth(Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude, translation by G. Rabassa) [1]

Îια ενανÏιοδÏομία â η ελληνική Îννοια ÏÏν ÏÏαγμάÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÎµÏαÏÏÎÏονÏαι ÏÏο ανÏίθεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï â ÏÏÎÏει να λάβει ÏÏÏα, και Î±Ï Ïή δεν είναι μια εÏκολη διαδικαÏία εÏειδή Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¿Î·Î³Î¿Ï Î¼ÎνÏÏ Î¸ÎµÏÏοÏνÏαν ÏÏ Îνα ÏÏνολο αÏληÏÏίαÏ, λαγνείαÏ, ÏÎ¬Î»Î·Ï Î³Î¹Î± ÎµÎ¾Î¿Ï Ïία και αÏÏ Î½ÎµÎ¯Î´Î·ÏÏν αÏνηÏικÏν (δηλαδή, ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏμαÏοÏ) ÏÏÎÏει ÏÏÏα να ανακληθεί. Î Î±Î½Î¬Î´Ï Ïη Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ÎÎ¹Î¿Ï Î½Î³Îº ÏεÏιÎγÏαÏε ÏÏ Â«Îνα αÏÏ Î½ÎµÎ¯Î´Î·Ïο ανÏίθεÏο ÏÏην ÏοÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï Â» ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏάγεÏαι ή αÏαιÏεί Ïην ανÏιμεÏÏÏιÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ±Ï ÏοÏ, κάÏι ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î¼Î²Î±Î¯Î½ÎµÎ¹ αÏÏ ÎºÎ¬Î¸Îµ άÏοÏη ÏÏο ÎκαÏÏ Î§ÏÏνια ÏÏαν, μÏÎ½Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏ Î½Î±Î¹ÏθημαÏικά αÏοδιοÏγανÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον θάναÏο ÏÎ·Ï ÎμαÏάνÏα ÎÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î±, ο ÎÏ ÏηλιανÏÏ ÏÏÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏα ÏειÏÏγÏαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎελÏιάδη (ÎÎ¹Î¿Ï Î½Î³Îº, ÎÏανÏα: ÎÏο Îοκίμια, 72). ÎνακαλÏÏÏει, εÏιÏÎÎ»Î¿Ï Ï, ÏÏι Ïο ÏειÏÏγÏαÏο ÏεÏιÎÏει Ïην ιÏÏοÏία ÏÎ·Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¿Î³ÎÎ½ÎµÎ¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ¿Ï . Το εÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏν ÎÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ½Î´Î¯Î± ÏεÏιλαμβάνει, ÏÏ Ïικά, ÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î»ÎµÏÏομÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏÎ³Î®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏ ÏηλιανοÏ, λεÏÏομÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏÎμειναν Î¼Ï ÏÏήÏιο γι' Î±Ï ÏÏν μÎÏÏι εκείνο Ïο Ïημείο. ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î¬Î¸ÎµÎ¹ Ïην ÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÏηÏά ÏÎ¿Ï , ο ÎÏ ÏÎ·Î»Î¹Î±Î½Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏά ÏÏην ανάγνÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¶ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην αÏÏή. Îε άλλα λÏγια, ÎÏονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÏÏα εÏιÏÏÏει μια ÏÏ Î³ÏÏÎ½ÎµÏ Ïη με Ïην AMAR και ÏÏη ÏÏ Î½ÎÏεια Ïην αÏÏλεÏε, ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÎÏει να εÏιÏÏÏÎÏει ÏÏον ÎµÎ±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï , να θÎÏει μÏÏοÏÏά ÏÏα μάÏια ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î»ÏκληÏη Ïην ÏÏοηγοÏμενη ζÏή ÏÎ¿Ï .ÎεμελιÏÎ´Î·Ï ÏÏÏο για ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î£ÏÏικοÏÏ ÏÏο και για ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎÏικοÏÏÎµÎ¹Î¿Ï Ï, η γνÏÏη, ή, ακÏιβÎÏÏεÏα, η ÏÏονÏίδα, ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ εξίÏÎ¿Ï ÏημανÏική ÏÏο Îεγάλο ÎÏγο ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î»ÏημείαÏ. ΣÏην ÎλεξανδÏινή ÏÏαγμαÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏάÏη {ÏÎ¿Ï ÎαλλÏÏη}, η ÏÎλεια γνÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ®Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ Î±Ï Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÎÏει ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÎ¹Î´Î¹ÎºÎ¿ÏÏ Î½Î± καÏανοήÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïα διαÏοÏεÏικά ονÏμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¯Î½Î¿Ï Î½ οι ÏιλÏÏοÏοι ÏÏην αÏÏκÏÏ Ïη Î¿Ï Ïία (..). Î ÎÏ ÏηλιανÏÏ ÎÏαμÏιλÏνια είναι Ïο μÏνο μÎÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¿Î³ÎÎ½ÎµÎ¹Î±Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ½Î´Î¯Î± ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Ïθηκε η ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹Ïία να γνÏÏίÏει Ïον ÎµÎ±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï , μια Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ¬Î»Ï Ïη ÏÎ¿Ï , ÏÏÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î´Î±Î¼Îµ, Îγινε ÏÏη γλÏÏÏα ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î»ÏημείαÏ. ÎÏοÏÏÏνÏÎ±Ï Î³Î½ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î³Î¹Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏογÏÎ½Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸ÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ για Ïην καÏαγÏγή ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïα ÏειÏÏγÏαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Îελκιάδη, Ïα οÏοία μÏοÏεί ξαÏνικά να διαβάÏει «ÏÏÏÎ¯Ï Ïην ÏαÏαμικÏή Î´Ï Ïκολία, Ïαν να ήÏαν γÏαμμÎνα ÏÏα ιÏÏανικά», ο ÎÏ ÏηλιανÏÏ Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Î»ÏÏÏει Ïην ολÎθÏια ÏÏ Î¼ÏÏνία ÏÎ·Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¿Î³ÎÎ½ÎµÎ¹Î±Ï Î¼Îµ Ïη μοναξιά (..).58 Î ÏÏ Î½Î± Î±ÎºÏ ÏÏÏει Î±Ï Ïή Ïη ÏÏ Î¼ÏÏνία είναι Ïο εÏÏÏημα ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎÏει ÏιÏÏηÏά Ïο Î¼Ï Î¸Î¹ÏÏÏÏημα Ïε ÏÎ»Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±Î½Î±Î³Î½ÏÏÏεÏ. ÎÏοι θÎÎ»Î¿Ï Î½ να βÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην αÏάνÏηÏη ÏÏÎÏει να ξεκινήÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏίÏνονÏÎ±Ï Î¼Î¹Î± ÏκληÏή, ανÎκÏÏαÏÏη μαÏιά μÎÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Ï. Îν είναι ειλικÏινείÏ, λÎει ο ÎάÏκεÏ, θα Î´Î¿Ï Î½ ÏÏι η Ïίζα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοβλήμαÏÏÏ Î¼Î±Ï ÎγκειÏαι Ïε μια ÏÏεδÏν ÏλήÏη άγνοια Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏει μεγαλÏÏεÏη ÏημαÏία. Φαινομενικά, ανÏλÏνÏÎ±Ï Ïο εÏÎθιÏμά ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην ÏλαÏÏνική ÏκÎÏη ÏÏÏÏ ÎµÎºÏÏάζεÏαι ÏÏο ÏÎÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Îλκιβιάδη, ο ÎκαÏθία ÎάÏÎºÎµÏ Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζει ÏÏι Ïο ÏÏÏβλημα για Ïην αÏομική ÏÏ Ïή είναι να αναγνÏÏίÏει Ïον ÎµÎ±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï Ïε Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ (ÎκαÏÏ Î§ÏÏνια 588â95). Πηθική και ÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î¼Î±Ïική ανάÏÏÏ Î¾Î· είναι ÏÏ Î½ÎÏεια ÏÎ·Ï Î±Ï ÏογνÏÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏοÏÏÏθεÏη για Ïην καÏανÏηÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎµÎ¹Î¼ÎÎ½Î¿Ï : Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ÎÏ Î³Î¿Ï ÏÏÎ¯Î½Î¿Ï Î±Ïοκαλεί quis facit veritatem, «να ÎºÎ¬Î½ÎµÎ¹Ï Ïην αλήθεια μÎÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Â» (243).

One Hundred Years of Solitude and The Creation of Latin American Mythology "Arcadio" is a specific reference to the Greek region of Arcadia. From the wiki: "It is situated in the central and eastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. It takes its name from the mythological figure Arcas. In Greek mythology, it was the home of the god Pan. In European Renaissance arts, Arcadia was celebrated as an unspoiled, harmonious wilderness." https://www.reddit.com/r/literature/c...

Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez and the Greek and Latin classics[5]...In his autobiography "Living to Tell the tale" makes clear references to the importance of knowledge of the classics. So in chapter 6, recalls, referring to his friend Gustavo Ibarra Merlano:

The thing that bothered him about me was my dangerous contempt for the Greek and Latin classics, which I found boring and useless, except for the Odyssey, that I had read and reread to pieces several times in high school. So before you say goodbye, he chose a bound leather book from his library and gave it to me with a certain solemnity. "You could become a good writer-he said- but you'll never be very good if you do not know well the Greek classics." The book was the complete works of Sophocles. Gustavo was from that moment one of the key persons in my life, because Oedipus is revealed to me in the first reading as the perfect work.

In One Hundred Years of Solitude he recreates the myth of Prometheus chained as punishment from the gods for having given fire to men for their progress. José Arcadio BuendÃa also tried to create a new society and so Macondo born.Also in One Hundred Years of Solitude he recreates the myth of Teuth by Plato about the value of writing, character that reminds us Melquiades of Hundred Years of Solitude; to the subject of the invention of writing is dedicated precisely the previous article in this blog

"Magic in Service of Truth"[10]"Magic in Service of Truth" refers to the literary technique of magical realism, where fantastic or supernatural elements are integrated into a realistic setting. This approach, particularly associated with Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez and his novel "One Hundred Years of Solitude," uses magic to enhance the emotional and dramatic impact of the narrative, making it more real rather than less. By blending the ordinary with the extraordinary, magical realism explores complex themes of history, politics, and human experience.Key aspects of "Magic in Service of Truth":Blending the Real and the Magical:Magical realism blurs the lines between the mundane and the supernatural, presenting fantastical events as commonplace within a realistic world.Enhancing Emotional Impact:The magic in these stories is not merely decorative; it serves to amplify the emotional resonance of the narrative, adding depth and meaning to the characters' experiences and the story's themes.Exploring Reality through Fantasy:Magical realism uses fantastical elements to examine and critique reality, often offering a unique perspective on history, politics, and social issues.Beyond Escapism:Unlike fantasy, which creates entirely separate worlds, magical realism roots itself in reality and uses magic to illuminate and reimagine the world as it is.Examples in Literature:One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez:The novel's depiction of events like a woman ascending to heaven, ghosts returning, and a priest levitating, presented alongside the historical and political realities of Latin America, exemplifies magical realism's power to enrich and deepen the narrative.Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel:This novel uses food as a metaphor for love and passion, and magical realism helps to portray the beauty of family life and bring political concerns to the forefront.In essence, "Magic in Service of Truth" describes how magical realism uses the fantastic to reveal deeper truths about the human condition and the world around us, making the familiar strange and the strange familiar.--

ξÏÏÏ

λλο ÏοÏ

μÏ

θιÏÏοÏήμαÏÎ¿Ï "ÎκαÏÏ Î§ÏÏνια ÎοναξιάÏ" (Cien años de soledad) ÏοÏ

ÎκαμÏÏιÎλ ÎκαÏÏία ÎάÏκεÏ.

ξÏÏÏ

λλο ÏοÏ

μÏ

θιÏÏοÏήμαÏÎ¿Ï "ÎκαÏÏ Î§ÏÏνια ÎοναξιάÏ" (Cien años de soledad) ÏοÏ

ÎκαμÏÏιÎλ ÎκαÏÏία ÎάÏκεÏ. ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ[1]. Pallavidini 2025. Îλ. εÏίÏÎ·Ï Ïον ÏÏολιαÏμÏ: https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/solitu... ÎÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¯ η ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI:ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI

The final line of Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez's "One Hundred Years of Solitude" describes the ultimate fate of Macondo, the town, and Aureliano Babilonia, the decipherer of the parchments. The city is destined to be destroyed by wind and forgotten, and Aureliano's deciphering of the parchments, which foretold this fate, will coincide with the city's demise, signifying the end of their shared history. Here's a more detailed breakdown: Aureliano Babilonia's Understanding:Aureliano, before finishing the last line of the parchments, understands that his fate and the city's are intertwined and irreversible.The City's Foretold Destruction:The parchments reveal that Macondo, a city built on mirrors and illusions, is destined to be wiped out by the wind and erased from human memory.Deciphering the Parchments:The act of deciphering the parchments is not just a task but a catalyst. The city's destruction is linked to the completion of this act.Irreversible Fate:The parchments also reveal that the events foretold within them are unrepeatable, emphasizing the cyclical and ultimately tragic nature of the BuendÃa family and Macondo's history.One Hundred Years of Solitude:The phrase "races condemned to one hundred years of solitude" refers to the cyclical and ultimately doomed nature of the BuendÃa family's history, where they repeat the same patterns of love, betrayal, and isolation.[5]. MartÃnez 2014.[10]. ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI <https://www.google.com/search?q=%22Ma...». εÏίÏηÏ: Subhas Yadav 2016.ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎhttps://www.degruyterbrill.com/docume..., M. 2025. (A)synchronic (Re)actions. Crises and Their Perception in Hittite History (Chronoi 14), ed. E. Cancik-Kirschbaum, C. Markschies and H. Parzinger), Einstein Center Chronoi, De Gruyter.

https://dokumen.pub/qdownload/the-oxf...

René Prieto. 2021. "Repetition and Alchemy in One Hundred Years of Solitude," in The Oxford Handbook of Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez, ed. G. H. Bell-Villada and I. López-Calvo, pp. 391â412.

https://dn790002.ca.archive.org/0/ite... GARCIA MARQUES. 1970. ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, trans. GREGORY RABASSA, AVON BOOKS â NEW YORK.

https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/solitu...

https://www.antiquitatem.com/en/origi..., Î. Î. 2014. "Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez and the Greek and Latin classics," antiquitatem, s.v. History of Greece and Rome, <https://www.antiquitatem.com/en/garci... (8 Aug. 2025).

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR)Vol-2, Issue-5, 2016ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.inImperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Page 929

Subhas Yadav. 2016. "Magic Realism and Indian Aesthetics: An Attempt to Analyse âA Very Old Man with Enormous Wingsâ," Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) 2 (5), pp. 929-936.

https://jjalltheway.medium.com/the-la..., J. J. 2017. "The Last Reader of One Hundred Years of Solitude," Medium, <https://jjalltheway.medium.com/the-la... (11 August 2025).

http://www.antiquitatem.com/en/garcia... would almost say that Oedipus Rex was the first great intellectual shock of my life. I already knew I would be a writer and when I read that, I said, " This is the kind of things I want to write." I had published some stories and , while working as a journalist in Cartagena , was trying to see if I could finished a novel. I remember one night talking about literature with a friend, Gustavo Ibarra Merlano , who besides being a poet, is the man who knows more in Colombia on customs duties â and comes and tells me: " You'll never amount to anything until you read the Greek classics . " I was very impressed , so that night I walked his home and put me in the hands a volume of Greek tragedies. I went to my room , I slept , I started reading the book to the first page â Oedipus was just â and I could not believe . He read , and read , and read â started about two in the morning and it was already dawning â and the more I read the more I wanted to read . I think that since then I have not stopped reading this blessed work . I know it by heart .

Published on August 26, 2025 20:53

August 19, 2025

ΠαÏÏαία μακεδονική ÏÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ® διάλεκÏοÏ: ÎÏιÏική εÏιÏκÏÏηÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏÏÏαÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎµÏ Î½Î±Ï

ΠαÏÏαία μακεδονική ÏÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ® διάλεκÏοÏ: ÎÏιÏική εÏιÏκÏÏηÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏÏÏαÏÎ·Ï ÎÏεÏ

Î½Î±Ï (Julián VÃctor Méndez Dosuna)

ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÏη διάθεÏή Î¼Î±Ï Ïολλά δεδομÎνα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ εÏιÏημανθεί ÏÏοκειμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î½Î± ÏÏηÏÎ¯Î¾Î¿Ï Î½ Ïην Îλληνική Î¥ÏÏθεÏη:

α ÎάÏÎ¿Î¹ÎµÏ Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¯ÎµÏ ÏηγÎÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏι οι ÎακεδÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î®Ïαν ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ μιλοÏÏαν μια διάλεκÏο ÏαÏÏμοια με Ïη διάλεκÏο ÏÎ·Ï ÎιÏÏÎ»Î¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏείÏÎ¿Ï .

β Îι ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏÎµÏ Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î¼Î±ÎºÎµÎ´Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎÏ Â«Î³Î»ÏÏÏεÏ» ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏαδίδονÏαι αÏÏ Ïον ÎÏÏÏιο μÏοÏοÏν να εÏÎ¼Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÏοÏν ÏÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎÏ Î»ÎÎ¾ÎµÎ¹Ï Î¼Îµ κάÏÎ¿Î¹ÎµÏ ÏÏνηÏικÎÏ Î¹Î´Î¹Î±Î¹ÏεÏÏÏηÏεÏ: Ï.Ï. á¼Î´á¿Â· οá½ÏανÏÏ. ÎακεδÏÎ½ÎµÏ (ÎΠαἰθήÏ), δÏÏαξ· ÏÏλὴν á½Ïὸ ÎακεδÏνÏν (ÎΠθÏÏαξ), δανῶν· κακοÏοιῶν. κÏείνÏν (ÏιθανÏν *θανÏÏ = ÎΠθαναÏÏÏ· ÏÏβ. μακεδ. Î´Î¬Î½Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïο ÎΠθάναÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏμÏÏνα με Ïον ΠλοÏÏαÏÏο, Îθικά 2.22c), γÏλα (γÏδα ÏγÏ.)Î á¼Î½ÏεÏα (ÏιθανÏν γολά = αÏÏ. Ïολή âÏολήâ, âÏοληδÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÏÏÏηâ, ομηÏ. ÏÎ¿Î»Î¬Î´ÎµÏ âÎνÏεÏαâ).²

γ Î ÏÏ Î½ÏÏιÏÏική ÏλειοÏηÏία ÏÏν ÎακεδÏνÏν ÎÏεÏε ελληνικά ονÏμαÏα: ΦίλιÏÏοÏ, á¼Î»ÎξανδÏοÏ, ΠεÏδίκκαÏ, á¼Î¼ÏνÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ»Ï.

δ ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î¼Î¹ÎºÏÏÏ Î±ÏιθμÏÏ ÏÏνÏομÏν, καÏά κανÏνα, εÏιγÏαÏÏν μαÏÏÏ Ïεί μια ελληνική γλÏÏÏική Ïοικιλία ÏÏ Î³Î³ÎµÎ½Î¹ÎºÎ® με Ïη δÏÏική. Τα εκÏενÎÏÏεÏα κείμενα είναι ο ÏεÏίÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏάδεÏÎ¼Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην Î Îλλα (ÏÏο ÎµÎ¾Î®Ï Î ÎÎÎÎ, βλ. ΠαÏάÏÏημα, Ïελ. 287), ÏεÏ. 380â350 Ï.Χ. (SEG 43.434· ÏÏβ. ÎÎ¿Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¬Ï 1993· Voutiras 1996, 1998· Dubois 1995) και Îνα αίÏημα ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïο μανÏείο ÏÎ¿Ï Îία ÏÏη ÎÏδÏνη (ÏÏο ÎµÎ¾Î®Ï ÎΩÎΩÎÎ), ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÏοÏεί να ÎÏει μακεδονική ÏÏοÎÎ»ÎµÏ Ïη (βλ. 5.2 ÏαÏακάÏÏ).

ε ΤÎλοÏ, η Îννα ΠαναγιÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ο ÎιλÏÎ¹Î¬Î´Î·Ï Î§Î±ÏζÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ μελεÏήÏει εÏιμελÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î¼Î±ÎºÎµÎ´Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎÏ ÎµÏιγÏαÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ γÏαμμÎÎ½ÎµÏ Ïε αÏÏική διάλεκÏο ή Ïε αÏÏικοÏÏνική κοινή και ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ενÏοÏίÏει Îναν αÏÎ¹Î¸Î¼Ï ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικÏν Ïα οÏοία αÏÎ¿Î´Î¯Î´Î¿Ï Î½ Ïε Î¼Î±ÎºÎµÎ´Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÏ Ï ÏÏÏÏÏÏμα.

ΠαÏÏαία μακεδονική ÏÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ® διάλεκÏοÏ:

ÎÏιÏική εÏιÏκÏÏηÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏÏÏαÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎµÏ Î½Î±Ï

1 ÎÏÎ³Ï ÏεÏιοÏιÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï , οι εÏιγÏαÏικÎÏ Î¼Î±ÏÏÏ ÏÎ¯ÎµÏ Î¸Î± είναι ÎµÎ´Ï ÎµÎ»Î¬ÏιÏÏεÏ. Îια ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏα ÏαÏαδείγμαÏα ÏαÏαÏÎμÏÏ ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î´Î·Î¼Î¿ÏιεÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î Î±Î½Î±Î³Î¹ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±ÏζÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï . ÎÏÎµÎ¯Î»Ï Î½Î± ÎµÏ ÏαÏιÏÏήÏÏ Ïον Alcorac Alonso Déniz για κάÏÎ¿Î¹ÎµÏ ÎµÎ½Î´Î¹Î±ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÏ ÏÏοÏάÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï .

2 Σε οÏιÏμÎÎ½ÎµÏ ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î¿Î¹ «γλÏÏÏεÏ» είναι ÏÏ ÏικÎÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎÏ Î»ÎÎ¾ÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ειδική ÏημαÏία ή, για κάÏοιο λÏγο, θεÏÏήθηκαν ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î¼Î±ÎºÎµÎ´Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï (Sowa 2006, 117â118): ÏÏβ. βημαÏίζειΠÏὸ Ïοá¿Ï ÏοÏὶ μεÏÏεá¿Î½, á¼ÏγιÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï (ÏιθανÏν ανÏί á¼ÏγίÏÎ¿Ï Ï)Î á¼ÎµÏÏÏ Î® θοÏÏιδεÏΠνÏμÏαι,

ÎοῦÏαι.

https://www.academia.edu/2342614/Anci... VÃctor Méndez Dosuna. 2012. "Ancient Macedonian as a Greek dialect: A critical survey on recent work (Greek, English, French, German text)," ÎÎνÏÏο ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎλÏÏÏαÏ: AÏÏαία Îακεδονία: ÎλÏÏÏα, ιÏÏοÏία, ÏολιÏιÏμÏÏ, εÏ. Î. K. ÎιαννάκηÏ, Ïελ. 65-132.

ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÏη διάθεÏή Î¼Î±Ï Ïολλά δεδομÎνα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ εÏιÏημανθεί ÏÏοκειμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î½Î± ÏÏηÏÎ¯Î¾Î¿Ï Î½ Ïην Îλληνική Î¥ÏÏθεÏη:

α ÎάÏÎ¿Î¹ÎµÏ Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¯ÎµÏ ÏηγÎÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏι οι ÎακεδÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î®Ïαν ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ μιλοÏÏαν μια διάλεκÏο ÏαÏÏμοια με Ïη διάλεκÏο ÏÎ·Ï ÎιÏÏÎ»Î¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏείÏÎ¿Ï .

β Îι ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏÎµÏ Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î¼Î±ÎºÎµÎ´Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎÏ Â«Î³Î»ÏÏÏεÏ» ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏαδίδονÏαι αÏÏ Ïον ÎÏÏÏιο μÏοÏοÏν να εÏÎ¼Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÏοÏν ÏÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎÏ Î»ÎÎ¾ÎµÎ¹Ï Î¼Îµ κάÏÎ¿Î¹ÎµÏ ÏÏνηÏικÎÏ Î¹Î´Î¹Î±Î¹ÏεÏÏÏηÏεÏ: Ï.Ï. á¼Î´á¿Â· οá½ÏανÏÏ. ÎακεδÏÎ½ÎµÏ (ÎΠαἰθήÏ), δÏÏαξ· ÏÏλὴν á½Ïὸ ÎακεδÏνÏν (ÎΠθÏÏαξ), δανῶν· κακοÏοιῶν. κÏείνÏν (ÏιθανÏν *θανÏÏ = ÎΠθαναÏÏÏ· ÏÏβ. μακεδ. Î´Î¬Î½Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïο ÎΠθάναÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏμÏÏνα με Ïον ΠλοÏÏαÏÏο, Îθικά 2.22c), γÏλα (γÏδα ÏγÏ.)Î á¼Î½ÏεÏα (ÏιθανÏν γολά = αÏÏ. Ïολή âÏολήâ, âÏοληδÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÏÏÏηâ, ομηÏ. ÏÎ¿Î»Î¬Î´ÎµÏ âÎνÏεÏαâ).²

γ Î ÏÏ Î½ÏÏιÏÏική ÏλειοÏηÏία ÏÏν ÎακεδÏνÏν ÎÏεÏε ελληνικά ονÏμαÏα: ΦίλιÏÏοÏ, á¼Î»ÎξανδÏοÏ, ΠεÏδίκκαÏ, á¼Î¼ÏνÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ»Ï.

δ ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î¼Î¹ÎºÏÏÏ Î±ÏιθμÏÏ ÏÏνÏομÏν, καÏά κανÏνα, εÏιγÏαÏÏν μαÏÏÏ Ïεί μια ελληνική γλÏÏÏική Ïοικιλία ÏÏ Î³Î³ÎµÎ½Î¹ÎºÎ® με Ïη δÏÏική. Τα εκÏενÎÏÏεÏα κείμενα είναι ο ÏεÏίÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏάδεÏÎ¼Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην Î Îλλα (ÏÏο ÎµÎ¾Î®Ï Î ÎÎÎÎ, βλ. ΠαÏάÏÏημα, Ïελ. 287), ÏεÏ. 380â350 Ï.Χ. (SEG 43.434· ÏÏβ. ÎÎ¿Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¬Ï 1993· Voutiras 1996, 1998· Dubois 1995) και Îνα αίÏημα ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïο μανÏείο ÏÎ¿Ï Îία ÏÏη ÎÏδÏνη (ÏÏο ÎµÎ¾Î®Ï ÎΩÎΩÎÎ), ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÏοÏεί να ÎÏει μακεδονική ÏÏοÎÎ»ÎµÏ Ïη (βλ. 5.2 ÏαÏακάÏÏ).

ε ΤÎλοÏ, η Îννα ΠαναγιÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ο ÎιλÏÎ¹Î¬Î´Î·Ï Î§Î±ÏζÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ μελεÏήÏει εÏιμελÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î¼Î±ÎºÎµÎ´Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎÏ ÎµÏιγÏαÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ γÏαμμÎÎ½ÎµÏ Ïε αÏÏική διάλεκÏο ή Ïε αÏÏικοÏÏνική κοινή και ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ενÏοÏίÏει Îναν αÏÎ¹Î¸Î¼Ï ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικÏν Ïα οÏοία αÏÎ¿Î´Î¯Î´Î¿Ï Î½ Ïε Î¼Î±ÎºÎµÎ´Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÏ Ï ÏÏÏÏÏÏμα.

ΠαÏÏαία μακεδονική ÏÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ® διάλεκÏοÏ:

ÎÏιÏική εÏιÏκÏÏηÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏÏÏαÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎµÏ Î½Î±Ï

1 ÎÏÎ³Ï ÏεÏιοÏιÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï , οι εÏιγÏαÏικÎÏ Î¼Î±ÏÏÏ ÏÎ¯ÎµÏ Î¸Î± είναι ÎµÎ´Ï ÎµÎ»Î¬ÏιÏÏεÏ. Îια ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏα ÏαÏαδείγμαÏα ÏαÏαÏÎμÏÏ ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î´Î·Î¼Î¿ÏιεÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î Î±Î½Î±Î³Î¹ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±ÏζÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï . ÎÏÎµÎ¯Î»Ï Î½Î± ÎµÏ ÏαÏιÏÏήÏÏ Ïον Alcorac Alonso Déniz για κάÏÎ¿Î¹ÎµÏ ÎµÎ½Î´Î¹Î±ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÏ ÏÏοÏάÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï .

2 Σε οÏιÏμÎÎ½ÎµÏ ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î¿Î¹ «γλÏÏÏεÏ» είναι ÏÏ ÏικÎÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎÏ Î»ÎÎ¾ÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ειδική ÏημαÏία ή, για κάÏοιο λÏγο, θεÏÏήθηκαν ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î¼Î±ÎºÎµÎ´Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï (Sowa 2006, 117â118): ÏÏβ. βημαÏίζειΠÏὸ Ïοá¿Ï ÏοÏὶ μεÏÏεá¿Î½, á¼ÏγιÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï (ÏιθανÏν ανÏί á¼ÏγίÏÎ¿Ï Ï)Î á¼ÎµÏÏÏ Î® θοÏÏιδεÏΠνÏμÏαι,

ÎοῦÏαι.

https://www.academia.edu/2342614/Anci... VÃctor Méndez Dosuna. 2012. "Ancient Macedonian as a Greek dialect: A critical survey on recent work (Greek, English, French, German text)," ÎÎνÏÏο ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎλÏÏÏαÏ: AÏÏαία Îακεδονία: ÎλÏÏÏα, ιÏÏοÏία, ÏολιÏιÏμÏÏ, εÏ. Î. K. ÎιαννάκηÏ, Ïελ. 65-132.

Published on August 19, 2025 07:52

June 22, 2025

The Greek-related state of Xiutu and the Xianbei aristocracy

5.2.3 Το ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏεÏÏ ÎºÏαÏίδιο ÏÎ¿Ï Xiutu και η αÏιÏÏοκÏαÏία ÏÏν XianbeiΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïο ιÏÏοÏιογÏαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Îιβλίο ÏÏν Han (Han Shu) οι βαÏÎ¹Î»ÎµÎ¯Ï ÏÏν κÏαÏιδίÏν Xiutu και Hunye, εÏι κεÏÎ±Î»Î®Ï 'βαÏβαÏικÏν' ÏÏλÏν Hu και δÏÏνÏÎµÏ ÏÏ ÏÏμμαÏοι ÏÏν Xiongnu,5_61 ήλεγÏαν εδάÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹Î±Î´ÏÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Gansu, Î´Ï ÏκολεÏονÏÎ±Ï Ïην εÏικοινÏνία μÎÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏμήμαÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ´Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎεÏαξιοÏ.5_62 ÎμÏÏ Ïο 121 Ï.Χ. ο Wudi (æ¼¢æ¦å¸ 157â87 Ï.Χ.), Î±Ï ÏοκÏάÏÏÏ ÏÏν Han, αÏÎÏÏειλε εκεί Ïον ÏÏÏαÏÎ·Î³Ï Huo Qubing ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î±ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÎÏαξε Ïα δÏο βαÏίλεια, άνοιξε Ïον κÏίÏιμο εμÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î´Î¹Î¬Î´Ïομο. Î©Ï Î±ÏοÏÎλεÏμα οι ηÏÏηθÎνÏÎµÏ Î²Î±ÏÎ¹Î»ÎµÎ¯Ï ÎµÏί κεÏÎ±Î»Î®Ï Î´ÎµÎºÎ¬Î´Ïν ÏιλιάδÏν Ï ÏοÏÏηÏικÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Ï, ÎºÎ¹Î½Î´Ï Î½ÎµÏονÏÎµÏ ÏÏÏα αÏÏ Ïην μήνιν ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÎ·Î³Î¿Ï ÏÏν Xiongnu, αναγκάÏÏηκαν να ÏαÏαδοθοÏν ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Han,5_63 με αÏοÏÎλεÏμα να ιδÏÏ Î¸Î¿Ïν ÏÎνÏε Ï ÏοÏελή ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Han κÏαÏίδια!5_64 Πνίκη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î½ÎÎ¶Î¿Ï ÏÏÏαÏÎ·Î³Î¿Ï Î®Ïαν ÏεÏιÏανήÏ, με αÏοÏÎλεÏμα να ÏÏ Î»Î»Î·ÏθοÏν αιÏμάλÏÏοι οκÏÏ ÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Î´ÎµÏ Hu και να ÏαÏθεί ÏÏ Î»Î¬ÏÏ Ïο Ïο ÏημιÏμÎνο ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ Xiutu ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιοÏÏε για να λαÏÏεÏει Ïον Î¿Ï ÏανÏ!5_65 ΣημειÏνεÏαι ÎµÎ´Ï ÏαÏενθεÏικά ÏÏι ο ÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏαÏÎ·Î³Î¿Ï ÎºÎ¿ÏμείÏαι αÏÏ Î»Î¯Î¸Î¹Î½Î¿ άγαλμα ίÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏιβαλλομÎÎ½Î¿Ï ÎµÏί Xiongnu, Î±Ï Ïή δε η καινοÏομία Î³Î»Ï ÏÏÎ®Ï Î±ÏεικονίÏεÏÏ ÏÏον ÏÏÏο θεÏÏείÏαι ÏÏ ÎÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î´Î¬Î½ÎµÎ¹Î¿ ÏÏην Îίνα!5_66 Το ÏεÏίÏημο ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Xiutu αÏεικονίζεÏαι Ïε ÏοιÏογÏαÏία ÏÎ¿Ï 8 αι. ÏÏν ÏÏηλαίÏν Mogao, ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏίÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¼ÏανίζεÏαι ο Î±Ï ÏοκÏάÏÏÏ Wu λαÏÏεÏÏν δÏο ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏÏικά αγάλμαÏα.ΣÏο δεÏÏεÏο μÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ®Ï ÎµÏγαÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï âÎÎ¹Î¿Î½Ï ÏιακÎÏ ÏελεÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ³Î¯ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ο ΧÏÏ ÏοÏÏ ÎεÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎίναÏâ ο ΧÏιÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï Î¼ÎµÎ»ÎµÏά Ïο διάÏημο ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏιλÎα Xiutu5_67 αÏÏ Ïο Gansu, με ÏÏÏÏο Ïην διεÏεÏνηÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏαγμαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏλαιÏÎ¯Î¿Ï .5_68 Î Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ¬Î»Ï Ïη ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏεικονίÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î³Î¬Î»Î¼Î±ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Xiutu ζÏγÏαÏιÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Ïε ÏοιÏογÏαÏία ÏÏν ÏÏηλαίÏν Mogao ÏÎ¿Ï Dunhuang ÏίÏνει ÏÏÏ Ïε Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο εÏÏÏημα και αÏοκαλÏÏÏει μιαν ανÏÏοÏÏη ÏαÏÎ¿Ï Ïία ÏÏο Gansu Ïην εÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Han Wudi, δηλαδή Î±Ï Ïήν ÏÏν ÎλληνοβακÏÏιανÏν και ÏÏν ÏÏ Î¼Î¼Î¬ÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î£Î±ÎºÏν και ΣογδιανÏν. Î£Ï Î½Î´ÎονÏÎ±Ï Î±Ï Ïά Ïα γεγονÏÏα με Ïα δÏδεκα ÏÏÏ ÏελεÏάνÏινα αγάλμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏάÏθηκαν ÏÏ Î»Î¬ÏÏ Ïα αÏÏ Ïον Qinshi Huangdi ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎºÎ±ÏÏ ÏÏÏνια νÏÏίÏεÏα ÏÏην ίδια ÏεÏιοÏή, ανακαλÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÏι Îνα βαÏίλειο ÏÏν Îλληνο - ΣακÏν (ή Îλληνο - ÎακÏÏιανÏν), ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏοÏελείÏο αÏÏ ÏεÏιÏειÏιÏμÎÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÏλειÏ, είÏε ÎδÏα ÏÏο κÎνÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Gansu και ήÏαν Ïο ÏÏÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Î¯Î´ÏÏ Ïε ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎακÏÏÎ¹Î±Î½Î®Ï ÎÏ Î¸ÏÎ´Î·Î¼Î¿Ï Î'. Îι ÏÏ Î½ÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Î»ÏÏεÏÏ Î´ÎµÎ½ ÏÏαμαÏοÏν εδÏ, γιαÏί Ï ÏονοείÏαι εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î¼Î¹Î± ÏÏ Î¼Î¼Î±Ïία μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοαναÏεÏθÎνÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï ÏοκÏάÏοÏα ÏÏν Qin και ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏÎ¹Î»ÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï ÏÏν Îλληνο - ΣακÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Gansu.ΣÏην Î±Î½Î¬Î»Ï Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ΧÏιÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζει Ïην ÏιθανÏÏηÏα Ïο Ïνομα Xiutu να αÏοÏελεί Ïο ÎºÎ¹Î½ÎµÎ¶Î¹ÎºÏ Î¹ÏοδÏναμο ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î½Î®Î¸Î¿Ï Ï ÎλληνιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏÎ¹Î»Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏίÏÎ»Î¿Ï Î£ÏÏήÏ,5_69 ÎµÎ½Ï ÎµÏιμÎνει να Ï ÏογÏαμμίζει Ïην ÏιθανÏÏηÏα ο βαÏιλεÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÏÏ Î½Î± μήν ήÏαν 'Îθνικά' Xiongnu.5_70 Î Jin Midi, Ï Î¹ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Xiutu, καÏÎληξε ομοίÏÏ ÏÏην Îίνα ÏÏν Han, ÏμÏÏ ÏάÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏην αÏοÏίÏÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏο καθήκον καÏÎληξε να αναδειÏθεί Ïε Îναν αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏενÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²Î¿Î·Î¸Î¿ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï ÏοκÏάÏοÏα Wu και ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Ïθηκε ο μεÏαθανάÏÎ¹Î¿Ï ÏίÏÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεβαÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î±ÏκηÏÎ¯Î¿Ï (Jinghou).5_71Î Jin Midi, Î¼Î±Î¶Ï Î¼Îµ Ïον νεÏÏεÏο αδελÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Lun, ίδÏÏ Ïαν μιά ÏολιÏική ÏαÏÏία η οÏοία διαÏήÏηÏε Ïον εξÎÏονÏα ÏÏλο ÏÎ·Ï Î³Î¹Î± ÏολλÎÏ Î³ÎµÎ½ÎµÎÏ!5_72 Î ÏοβεβλημÎνα μÎλη ÏÏν ÏαÏÏιÏν ÏÏν Jin & Ban γÎννηÏαν ÏημανÏικÎÏ ÏÏοÏÏÏικÏÏηÏÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏολιÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î¶ÏήÏ, αλλά και ÏημανÏικοÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏÎ½ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ιÏÏοÏιογÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï!5_73Îια ενδιαÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Ïα θεÏÏία ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸Î± εξηγοÏÏε οÏιÏμÎνα αÏÏ Ïα ελληνιÏÏικά Îθιμα και καλλιÏεÏνικÎÏ ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ διαÏιÏÏÏθεί με ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Murong Xianbei ÏÏοÎÏÏεÏαι αÏÏ Ïο ÎÏγο ÏÎ¿Ï Yao Weiyuan (å§èå 1905â1985),5_74 ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζεÏαι ÏÏι ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï Xiutu ήÏαν ο ÏÏÏÎ³Î¿Î½Î¿Ï Î¿ÏιÏμÎνÏν μελÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏαÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î±ÏιÏÏοκÏαÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏν Xianbei. ÎλλÏÏÏε και ο Sanping Chen ÎÏει ομοίÏÏ ÏημειÏÏει ÏÏι ο Chen Yuan, μελεÏηÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏÎ³Î®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Lu Fayan αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Xianbei, θεÏÏηÏε ÏεÏίεÏγη Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην 'βαÏβαÏική' ÏÏοÎÎ»ÎµÏ Ïη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏÎα ÏÎ¿Ï Qieyun, μνημειÏÎ´Î¿Ï Ï Î»ÎµÎ¾Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î¿Î¼Î¿Î¹Î¿ÎºÎ±ÏαληξιÏν Qieyun!5_75ΣÏεÏική με ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏοαναÏεÏθείÏÎµÏ ÎλληνιÏÏικÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏεÏνικÎÏ ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏν Xianbei θεÏÏείÏαι ÏÏÏ Ïή ζÏνη ÏηÏοÏμενη ÏÏο Î¼Î¿Ï Ïείο Qinghai. Το ÎÎ¿Ï Ïείο ÏÏονολογεί Ïην ζÏνη ÏÏην ÏεÏίοδο ÏÎ·Ï Î´Ï Î½Î±ÏÏÎµÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏν Tang. Îλλά ο ΧÏιÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï ÏημειÏνει ÏÏεÏικά:5_76 Î¥ÏάÏÏει εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î¼Î¹Î± αÏημÎνια εÏίÏÏÏ Ïη ελληνιÏÏική ζÏνη με ελληνικÎÏ Î¼Ï Î¸Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¹ÎºÎÏ Î¼Î¿ÏÏÎÏ, με ÎνθεÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏολÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î¿Ï Ï Î»Î¯Î¸Î¿Ï Ï, ÏÎ¿Ï Î²ÏÎθηκε ÏÏο Qinghai Dulan (é½è) και λÎγεÏαι ÏÏι είναι αÏÏ Ïην Kushano- ΣαÏÏανιδική ÏεÏίοδο (ÎικÏνα 30). ÎκÏίθεÏαι ÏÏο ÎÎ¿Ï Ïείο Qinghai, ÏμÏÏ Î· αÏεικÏνιÏη ÏÏν θεοÏήÏÏν ÏÏ ÏÏοÏηÏικÏν Î½Ï Î¼ÏÏν - μελιÏÏÏν (ÎÏιαί) και ο ÎιÏÎ½Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ïην ÏοÏοθεÏεί μάλλον ενÏÏίÏεÏα αÏÏ Ïον ÏÏίÏο αιÏνα μ.Χ. ÎιαÏί οι ΣαÏÏανίδεÏ, Ïε Î±Ï Ïή Ïην αναÏαÏάÏÏαÏη, δεν θα είÏαν ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιήÏει Ïο κÏÎ¬Î½Î¿Ï ÎµÎ½ÏÏ ÎλληνοβακÏÏÎ¹Î±Î½Î¿Ï Î²Î±ÏιλÎα ανÏί για Îνα κÏÎ¬Î½Î¿Ï Ïιο κονÏά ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î´Î¹ÎºÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏολιÏιÏÏικÎÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏοÏÎÏ.. Το Dulan βÏίÏκεÏαι ÏÏην ÏεÏιοÏή ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÏ Î²ÎÏνηÏαν οι Murong Xianbei. Îίναι εÏίÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ¹Î¸Î±Î½Ï Î· ζÏνη να καÏαÏÎºÎµÏ Î¬ÏÏηκε ακÏιβÏÏ ÎµÎºÎµÎ¯, ÏÏο ελληνοÏÎ±ÎºÎ¹ÎºÏ Î²Î±Ïίλειο ÏÎ¿Ï Gansu και ÏÏι ÏÏην ÎακÏÏιανή.ÏÏοÏθÎÏει δε ÏÏο Ï ÏÏμνημα ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¹Îº. 30:ÎικÏνα 30. (α) ÎλληνιÏÏική αÏÎ³Ï ÏÏÏÏÏ Ïη ζÏνη 90 cm, ÎÎ¿Ï Ïείο Qinghai. ÎÏο μοÏÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎιονÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î¿Î¹Î¬Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ να ÏÏ Î»Î¬Î½Îµ μια ÏÏÏÏα, με Ïον θÏÏÏο ÏÏη μÎÏη. (β) ÎÏο ÏÏεÏÏÏÎÏ Î·Î¼Î¹-νÏμÏÎµÏ (ÎÏιαί) κÏαÏοÏν Îνα ÏÏεÏάνι (γ, δ). Î ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î´Ïο ÏοÏά εμÏανÏÏ ÎºÏÎ¬Î½Î¿Ï Îλληνο - ÎακÏÏÎ¹Î±Î½Ï (c). ΠβαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ η βαÏίλιÏÏα κάθονÏαι και κÏαÏοÏν Îνα ÏÏεÏάνι, ÏÏμβολο ÏλοÏÏÎ¿Ï , Î´Ï Î½Î¬Î¼ÎµÏÏ, δÏÎ¾Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ αιÏνιÏÏηÏαÏ. ΦαίνεÏαι να κÏαÏοÏν ÏÏα γÏναÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Ïην ίδια ζÏνη με ÏÏÏÎ¿Î³Î³Ï Î»Î¬ ÏμήμαÏα (ε). ÎÎ»ÎµÏ Î¿Î¹ μοÏÏÎÏ ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïο Îνα ÏÎÏι ÏÏο ÏÏομάÏι και με Ïο άλλο κÏαÏοÏν Îνα ÏÏεÏάνι (c, d).

Îικ. 5_5: ÎÏίÏÏÏ

Ïη ÎÏημÎνια ÎÏνη με ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÎεοÏÏ Ïε εμβλήμαÏα

Îικ. 5_5: ÎÏίÏÏÏ

Ïη ÎÏημÎνια ÎÏνη με ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÎεοÏÏ Ïε εμβλήμαÏα

Îικ. 5_6: Îμβλημα με νÏμÏη αÏÏ Ïην ζÏνη (αÏ.) & ΧÏÏ

ÏÎÏ ÏλακÎÏÎµÏ Î¼Îµ ÏαÏακÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏεÏÏÏÏν γÏ

ναικÏν-μελιÏÏÏν, ÏιθανÏÏ ÏÏν ÎÏιÏν (δεξ.)

Îικ. 5_6: Îμβλημα με νÏμÏη αÏÏ Ïην ζÏνη (αÏ.) & ΧÏÏ

ÏÎÏ ÏλακÎÏÎµÏ Î¼Îµ ÏαÏακÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏεÏÏÏÏν γÏ

ναικÏν-μελιÏÏÏν, ÏιθανÏÏ ÏÏν ÎÏιÏν (δεξ.)ÎνακεÏαλαιÏνονÏÎ±Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïον Xiutu μÏοÏοÏμε να αναÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÏι Î±Ï Ïή η αινιγμαÏική και ÏημανÏική ÏÏοÏÏÏικÏÏηÏα ÏÏην κινεζική ιÏÏοÏία ήÏαν ÏιθανÏν ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏγήÏ. ÎίÏε Îναν γιο ονÏμαÏι ÎίνÏι (ΡίνÏι), ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î±ÏγÏÏεÏα θα λάβει Ïο εÏίθεÏο «ΧÏÏ ÏÏÏ Midi» αÏÏ Ïον Wudi, Ïον Î±Ï ÏοκÏάÏοÏα ÏÏν Han (157â87 Ï.Χ.). ΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïην Hanshu, εÏίÏημη Î´Ï Î½Î±ÏÏική ιÏÏοÏία ÏÏν ÏÏÏιμÏν HanÎ¿Ï Ï Han, ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï Xiutu είÏε Ïην ÏÏÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ïά ÏÎ¿Ï Ïε μια αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î¼ÎµÏÎÏειÏα κινεζικÎÏ Â«Î´Îκα ÏεÏιÏÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Wuwei» ÏÏν Han και ÎÏει ÏεÏιγÏαÏεί ÏÏ Î²Î±ÏιλÎÎ±Ï ÏÏν Xiongnu αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏικοÏÏ.5_77 ΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïη wikipedia, wikipedia, s.v. Jin Midi, ο Midi γεννήθηκε Ïο 134 Ï.Χ. Ïε μια βαÏιλική οικογÎνεια, ÏÏ Î¼Î¼Î±Ïική ÏÏν Xiongnu, Ï ÏήÏξε δε ÏιθανÏÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¿Î²Î±ÎºÏÏÎ¹Î±Î½Î®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏÎ³Î®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎºÏ Î²ÎµÏνοÏÏε Ïο κενÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Gansu. ÎÏαν ο κληÏονÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±Ïιλιά Xiutu (Soter/ΣÏÏήÏ), ενÏÏ Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏημανÏικÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²Î±ÏÎ¹Î»ÎµÎ¯Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏηÏεÏοÏÏαν Ï ÏÏ Ïον Gunchen Chanyu, ανÏÏαÏο ηγεμÏνα ÏÏν Xiongnu. ÎεÏά Ïο θάναÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Gunchen Ïο 126 Ï.Χ., Ïον διαδÎÏθηκε ο αδελÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Yizhixie. ÎαÏά Ïη διάÏκεια Î±Ï ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï , ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Xiutu και ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î¬Î»Î»Î¿Ï Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»Î¿Ï Î²Î±ÏιλιάÏ, ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï Hunxie, ανÎλαβαν να Ï ÏεÏαÏÏιÏÏοÏν Ïα νοÏÎ¹Î¿Î´Ï Ïικά ÏÏνοÏα ÏÏν Xiongnu ενάνÏια ÏÏη Î´Ï Î½Î±ÏÏεία Han - ÏÏο ÏÏγÏÏονο κενÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Î´Ï ÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Gansu. ÎÏ ÏÏ Î±ÎºÏιβÏÏ Ïο άÏομο, ο Jin Midi, μαζί με Ïον Xiutu Ï ÏήÏξαν οι γενεÏικοί ιδÏÏ ÏÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î´Î¹Î¬ÏÎ·Î¼Î·Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¿Î³ÎÎ½ÎµÎ¹Î±Ï Ban.5_78

ΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïον Sanping Chen, Î±Ï Î¸ÎµÎ½Ïία ÏÏον ÎºÎ¹Î½ÎµÎ¶Î¹ÎºÏ ÏολιÏιÏÎ¼Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ιÏÏοÏία, η οικογÎνεια:

.... οικογÎνεια ÏαÏήγαγε ÏÏι μÏνο Ïον Ban Biao (3-54), Ïον Ban Gu (32-92) και Ïον Ban Zhao (ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï 49-ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï 120), Ïο ÏÏίο ÏαÏÎÏα-Î³Î¹Î¿Ï -κÏÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎγÏαÏε Ïην ÏÏÏÏη Î´Ï Î½Î±ÏÏική ιÏÏοÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ¯Î½Î±Ï Hanshou αλλά και ο εξαιÏεÏικά ÏολμηÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ικανÏÏ Î´Î¹ÏλÏμάÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏαÏηγÏÏ Ban Chao (33-103), ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î¼ÏÎ½Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï (ÏÏμÏÏνα με ÏληÏοÏοÏÎ¯ÎµÏ Î¼Îµ δÏναμη μÏνο 36 ÏÏ Î½Î±Î´ÎλÏÏν ÏÏ ÏοδιÏκÏεÏ) εÏανίδÏÏ Ïε Ïην ÎºÏ ÏιαÏÏία ÏÏν Han ÏÏην ÎενÏÏική ÎÏία (γνÏÏÏή ÏÏÏε ÏÏ ÎÏ ÏικÎÏ Î ÎµÏιÏÎÏειεÏ) μεÏά Ïην καÏαÏÏÏοÏή Ï ÏÏ Ïον ÏÏÎ±Î³Î¹ÎºÏ Ï ÏοκÏιÏή Wang Mang (45 Ï.Χ.-23 μ.Χ.). Το καÏÏÏθÏμα ÏÎ¿Ï Chao ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏίÏÏηκε ÏεÏαιÏÎÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïον Î³Î¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ban Yong, γεννηθÎνÏα μάλιÏÏα ÏÏην ÎενÏÏική ÎÏία.

..

ΠιÏÏοÏιογÏαÏία ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î½ÎµÎ³ÏάÏη αÏÏ Ïην οικογÎνεια Ban άÏκηÏε ÏαÏÏÏ Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»Î· εÏιÏÏοή ÏÏην αÏοκαÏάÏÏαÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎομÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î±Î½Î®Ï ÏκÎÏεÏÏ Î· οÏοία ήÏαν Ïιζικά ÏÏοÏαναÏολιÏμÎνη ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïην αÏεÏή και Ï ÏήÏξε ÏιλοÏαÏαγÏγική και ÏιλοαγÏοÏική, και αν η ανάγνÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον Hill είναι ÏÏÏÏή, ÏαίνεÏαι ÏÏι Ïο ÎÏÏαξε με ÏÏÏη εÏιείκεια ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏÎÏÏη κοινή λογική για ÏÎ¹Ï ÎµÏÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½ÎµÏ ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï Ï.

Îικ. 5_7: ΤοιÏογÏαÏία ÏοÏ

8 αι. ÏÏα ÏÏήλαια Mogao αÏεικονίζοÏ

Ïα Ïον αÏ

ÏοκÏάÏοÏα Wu (λαÏÏεÏονÏα δÏο ÎοÏ

διÏÏικά αγάλμαÏα) & Ïο ÏÏÏ

ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏοÏ

Xiutu

Îικ. 5_7: ΤοιÏογÏαÏία ÏοÏ

8 αι. ÏÏα ÏÏήλαια Mogao αÏεικονίζοÏ

Ïα Ïον αÏ

ÏοκÏάÏοÏα Wu (λαÏÏεÏονÏα δÏο ÎοÏ

διÏÏικά αγάλμαÏα) & Ïο ÏÏÏ

ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏοÏ

Xiutu Îικ. 5_8: ÎεÏικÏÏ ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏÎ³Î®Ï Î· ÏÏÏÏοÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÏονÏμοÏ, ιÏÏοÏικÏÏ, ÏιλÏÏοÏοÏ, ÏÏ

γγÏαÏÎÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ μοÏ

ÏικÏÏ Ban Zhao?

Îικ. 5_8: ÎεÏικÏÏ ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏÎ³Î®Ï Î· ÏÏÏÏοÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÏονÏμοÏ, ιÏÏοÏικÏÏ, ÏιλÏÏοÏοÏ, ÏÏ

γγÏαÏÎÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ μοÏ

ÏικÏÏ Ban Zhao?Î ÏÏοαναÏεÏθείÏα ανÏÏÎÏÏ ÎµÎ½Î´Î¹Î±ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Ïα θεÏÏία ÏÎ¿Ï Yao Weiyuan ÏεÏί ÎλληνικÏÏηÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏιλÎα Xiutu και Ïο γεγονÏÏ ÏÏι Î±Ï ÏÏÏ Ï ÏήÏξε ÏÏÏÎ³Î¿Î½Î¿Ï Î¿ÏιÏμÎνÏν μελÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏαÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î±ÏιÏÏοκÏαÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏν Xianbei θα εξηγοÏÏε μεÏικά αÏÏ Ïα ελληνιÏÏικά Îθιμα και αναÏοÏÎÏ ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏάÏÏÎ¿Ï Î½ μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÏν Murong Xianbei!5_79 Τα μÎλη Î±Ï ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï âεθνοÏικήÏâ Î¿Î¼Î¬Î´Î±Ï ÎµÎ¯Ïαν μακÏοÏÏÏνια εÏιÏÏοή ÏÏην Îίνα αÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏείÏαν εξÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÏ Î¸ÎÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏην κινεζική αÏιÏÏοκÏαÏία,5_80 μάλιÏÏα καÏά Ïον IV/V αι. ανÎλαβαν και Ïην Î´Î¹Î±ÎºÏ Î²ÎÏνηÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏαÏ! Î¥ÏÏ Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην Îννοια, η ελληνική ÏÏ Î½ÎµÎ¹ÏÏοÏά ÏÏην κινεζική ÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î¼Î±Ïική ιÏÏοÏία μÏοÏεί να αναγνÏÏιÏÏεί ÏÏι διÎθεÏε Îναν εÏιÏλÎον δÏÏμο για Ïην ÏÏαγμαÏοÏοίηÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏολιÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏικοινÏÎ½Î¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÎµÏ ÎºÏÎ»Ï Î½Îµ Ïην ÏολιÏιÏÏική ανÏαλλαγή! ÎμÏÏ Î· ειÏαγÏγή ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÏην αÏÏαία Îίνα ήÏαν Îνα άλλο ÏημανÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î¼Î¿Î½Î¿ÏάÏι - Î´Î¯Î¿Î´Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïη διάÏÏ Ïη ÏÏν καλλιÏεÏνικÏν ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¿-Î¹Î½Î´Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï Gandhara καθÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏν ÏÏεÏικÏν θÏηÏÎºÎµÏ ÏικÏν - ÏιλοÏοÏικÏν ÏÏ Î»Î»Î®ÏεÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏμοÏ.

Published on June 22, 2025 02:16

5.2.3 Το ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏεÏÏ ÎºÏ...

5.2.3 Το ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏεÏÏ ÎºÏαÏίδιο ÏÎ¿Ï Xiutu και η αÏιÏÏοκÏαÏία ÏÏν XianbeiΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïο ιÏÏοÏιογÏαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Îιβλίο ÏÏν Han (Han Shu) οι βαÏÎ¹Î»ÎµÎ¯Ï ÏÏν κÏαÏιδίÏν Xiutu και Hunye, εÏι κεÏÎ±Î»Î®Ï 'βαÏβαÏικÏν' ÏÏλÏν Hu και δÏÏνÏÎµÏ ÏÏ ÏÏμμαÏοι ÏÏν Xiongnu,5_61 ήλεγÏαν εδάÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹Î±Î´ÏÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Gansu, Î´Ï ÏκολεÏονÏÎ±Ï Ïην εÏικοινÏνία μÎÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏμήμαÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ´Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎεÏαξιοÏ.5_62 ÎμÏÏ Ïο 121 Ï.Χ. ο Wudi (æ¼¢æ¦å¸ 157â87 Ï.Χ.), Î±Ï ÏοκÏάÏÏÏ ÏÏν Han, αÏÎÏÏειλε εκεί Ïον ÏÏÏαÏÎ·Î³Ï Huo Qubing ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î±ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÎÏαξε Ïα δÏο βαÏίλεια, άνοιξε Ïον κÏίÏιμο εμÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î´Î¹Î¬Î´Ïομο. Î©Ï Î±ÏοÏÎλεÏμα οι ηÏÏηθÎνÏÎµÏ Î²Î±ÏÎ¹Î»ÎµÎ¯Ï ÎµÏί κεÏÎ±Î»Î®Ï Î´ÎµÎºÎ¬Î´Ïν ÏιλιάδÏν Ï ÏοÏÏηÏικÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Ï, ÎºÎ¹Î½Î´Ï Î½ÎµÏονÏÎµÏ ÏÏÏα αÏÏ Ïην μήνιν ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÎ·Î³Î¿Ï ÏÏν Xiongnu, αναγκάÏÏηκαν να ÏαÏαδοθοÏν ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Han,5_63 με αÏοÏÎλεÏμα να ιδÏÏ Î¸Î¿Ïν ÏÎνÏε Ï ÏοÏελή ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Han κÏαÏίδια!5_64 Πνίκη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î½ÎÎ¶Î¿Ï ÏÏÏαÏÎ·Î³Î¿Ï Î®Ïαν ÏεÏιÏανήÏ, με αÏοÏÎλεÏμα να ÏÏ Î»Î»Î·ÏθοÏν αιÏμάλÏÏοι οκÏÏ ÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Î´ÎµÏ Hu και να ÏαÏθεί ÏÏ Î»Î¬ÏÏ Ïο Ïο ÏημιÏμÎνο ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ Xiutu ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιοÏÏε για να λαÏÏεÏει Ïον Î¿Ï ÏανÏ!5_65 ΣημειÏνεÏαι ÎµÎ´Ï ÏαÏενθεÏικά ÏÏι ο ÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏαÏÎ·Î³Î¿Ï ÎºÎ¿ÏμείÏαι αÏÏ Î»Î¯Î¸Î¹Î½Î¿ άγαλμα ίÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏιβαλλομÎÎ½Î¿Ï ÎµÏί Xiongnu, Î±Ï Ïή δε η καινοÏομία Î³Î»Ï ÏÏÎ®Ï Î±ÏεικονίÏεÏÏ ÏÏον ÏÏÏο θεÏÏείÏαι ÏÏ ÎÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î´Î¬Î½ÎµÎ¹Î¿ ÏÏην Îίνα!5_66 Το ÏεÏίÏημο ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Xiutu αÏεικονίζεÏαι Ïε ÏοιÏογÏαÏία ÏÎ¿Ï 8 αι. ÏÏν ÏÏηλαίÏν Mogao, ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏίÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¼ÏανίζεÏαι ο Î±Ï ÏοκÏάÏÏÏ Wu λαÏÏεÏÏν δÏο ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏÏικά αγάλμαÏα.ΣÏο δεÏÏεÏο μÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ®Ï ÎµÏγαÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï âÎÎ¹Î¿Î½Ï ÏιακÎÏ ÏελεÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ³Î¯ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ο ΧÏÏ ÏοÏÏ ÎεÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎίναÏâ ο ΧÏιÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï Î¼ÎµÎ»ÎµÏά Ïο διάÏημο ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏιλÎα Xiutu5_67 αÏÏ Ïο Gansu, με ÏÏÏÏο Ïην διεÏεÏνηÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏαγμαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏλαιÏÎ¯Î¿Ï .5_68 Î Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ¬Î»Ï Ïη ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏεικονίÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î³Î¬Î»Î¼Î±ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Xiutu ζÏγÏαÏιÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Ïε ÏοιÏογÏαÏία ÏÏν ÏÏηλαίÏν Mogao ÏÎ¿Ï Dunhuang ÏίÏνει ÏÏÏ Ïε Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο εÏÏÏημα και αÏοκαλÏÏÏει μιαν ανÏÏοÏÏη ÏαÏÎ¿Ï Ïία ÏÏο Gansu Ïην εÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Han Wudi, δηλαδή Î±Ï Ïήν ÏÏν ÎλληνοβακÏÏιανÏν και ÏÏν ÏÏ Î¼Î¼Î¬ÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î£Î±ÎºÏν και ΣογδιανÏν. Î£Ï Î½Î´ÎονÏÎ±Ï Î±Ï Ïά Ïα γεγονÏÏα με Ïα δÏδεκα ÏÏÏ ÏελεÏάνÏινα αγάλμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏάÏθηκαν ÏÏ Î»Î¬ÏÏ Ïα αÏÏ Ïον Qinshi Huangdi ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎºÎ±ÏÏ ÏÏÏνια νÏÏίÏεÏα ÏÏην ίδια ÏεÏιοÏή, ανακαλÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÏι Îνα βαÏίλειο ÏÏν Îλληνο - ΣακÏν (ή Îλληνο - ÎακÏÏιανÏν), ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏοÏελείÏο αÏÏ ÏεÏιÏειÏιÏμÎÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÏλειÏ, είÏε ÎδÏα ÏÏο κÎνÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Gansu και ήÏαν Ïο ÏÏÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Î¯Î´ÏÏ Ïε ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎακÏÏÎ¹Î±Î½Î®Ï ÎÏ Î¸ÏÎ´Î·Î¼Î¿Ï Î'. Îι ÏÏ Î½ÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Î»ÏÏεÏÏ Î´ÎµÎ½ ÏÏαμαÏοÏν εδÏ, γιαÏί Ï ÏονοείÏαι εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î¼Î¹Î± ÏÏ Î¼Î¼Î±Ïία μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοαναÏεÏθÎνÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï ÏοκÏάÏοÏα ÏÏν Qin και ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏÎ¹Î»ÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï ÏÏν Îλληνο - ΣακÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Gansu.ΣÏην Î±Î½Î¬Î»Ï Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ΧÏιÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζει Ïην ÏιθανÏÏηÏα Ïο Ïνομα Xiutu να αÏοÏελεί Ïο ÎºÎ¹Î½ÎµÎ¶Î¹ÎºÏ Î¹ÏοδÏναμο ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î½Î®Î¸Î¿Ï Ï ÎλληνιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏÎ¹Î»Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏίÏÎ»Î¿Ï Î£ÏÏήÏ,5_69 ÎµÎ½Ï ÎµÏιμÎνει να Ï ÏογÏαμμίζει Ïην ÏιθανÏÏηÏα ο βαÏιλεÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÏÏ Î½Î± μήν ήÏαν 'Îθνικά' Xiongnu.5_70 Î Jin Midi, Ï Î¹ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Xiutu, καÏÎληξε ομοίÏÏ ÏÏην Îίνα ÏÏν Han, ÏμÏÏ ÏάÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏην αÏοÏίÏÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏο καθήκον καÏÎληξε να αναδειÏθεί Ïε Îναν αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏενÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²Î¿Î·Î¸Î¿ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï ÏοκÏάÏοÏα Wu και ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Ïθηκε ο μεÏαθανάÏÎ¹Î¿Ï ÏίÏÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεβαÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î±ÏκηÏÎ¯Î¿Ï (Jinghou).5_71Î Jin Midi, Î¼Î±Î¶Ï Î¼Îµ Ïον νεÏÏεÏο αδελÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Lun, ίδÏÏ Ïαν μιά ÏολιÏική ÏαÏÏία η οÏοία διαÏήÏηÏε Ïον εξÎÏονÏα ÏÏλο ÏÎ·Ï Î³Î¹Î± ÏολλÎÏ Î³ÎµÎ½ÎµÎÏ!5_72 Î ÏοβεβλημÎνα μÎλη ÏÏν ÏαÏÏιÏν ÏÏν Jin & Ban γÎννηÏαν ÏημανÏικÎÏ ÏÏοÏÏÏικÏÏηÏÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏολιÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î¶ÏήÏ, αλλά και ÏημανÏικοÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏÎ½ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ιÏÏοÏιογÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï!5_73Îια ενδιαÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Ïα θεÏÏία ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸Î± εξηγοÏÏε οÏιÏμÎνα αÏÏ Ïα ελληνιÏÏικά Îθιμα και καλλιÏεÏνικÎÏ ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ διαÏιÏÏÏθεί με ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Murong Xianbei ÏÏοÎÏÏεÏαι αÏÏ Ïο ÎÏγο ÏÎ¿Ï Yao Weiyuan (å§èå 1905â1985),5_74 ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζεÏαι ÏÏι ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï Xiutu ήÏαν ο ÏÏÏÎ³Î¿Î½Î¿Ï Î¿ÏιÏμÎνÏν μελÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏαÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î±ÏιÏÏοκÏαÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏν Xianbei. ÎλλÏÏÏε και ο Sanping Chen ÎÏει ομοίÏÏ ÏημειÏÏει ÏÏι ο Chen Yuan, μελεÏηÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏÎ³Î®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Lu Fayan αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Xianbei, θεÏÏηÏε ÏεÏίεÏγη Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην 'βαÏβαÏική' ÏÏοÎÎ»ÎµÏ Ïη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏÎα ÏÎ¿Ï Qieyun, μνημειÏÎ´Î¿Ï Ï Î»ÎµÎ¾Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î¿Î¼Î¿Î¹Î¿ÎºÎ±ÏαληξιÏν Qieyun!5_75ΣÏεÏική με ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏοαναÏεÏθείÏÎµÏ ÎλληνιÏÏικÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏεÏνικÎÏ ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏν Xianbei θεÏÏείÏαι ÏÏÏ Ïή ζÏνη ÏηÏοÏμενη ÏÏο Î¼Î¿Ï Ïείο Qinghai. Το ÎÎ¿Ï Ïείο ÏÏονολογεί Ïην ζÏνη ÏÏην ÏεÏίοδο ÏÎ·Ï Î´Ï Î½Î±ÏÏÎµÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏν Tang. Îλλά ο ΧÏιÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï ÏημειÏνει ÏÏεÏικά:5_76 Î¥ÏάÏÏει εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î¼Î¹Î± αÏημÎνια εÏίÏÏÏ Ïη ελληνιÏÏική ζÏνη με ελληνικÎÏ Î¼Ï Î¸Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¹ÎºÎÏ Î¼Î¿ÏÏÎÏ, με ÎνθεÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏολÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î¿Ï Ï Î»Î¯Î¸Î¿Ï Ï, ÏÎ¿Ï Î²ÏÎθηκε ÏÏο Qinghai Dulan (é½è) και λÎγεÏαι ÏÏι είναι αÏÏ Ïην Kushano- ΣαÏÏανιδική ÏεÏίοδο (ÎικÏνα 30). ÎκÏίθεÏαι ÏÏο ÎÎ¿Ï Ïείο Qinghai, ÏμÏÏ Î· αÏεικÏνιÏη ÏÏν θεοÏήÏÏν ÏÏ ÏÏοÏηÏικÏν Î½Ï Î¼ÏÏν - μελιÏÏÏν (ÎÏιαί) και ο ÎιÏÎ½Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ïην ÏοÏοθεÏεί μάλλον ενÏÏίÏεÏα αÏÏ Ïον ÏÏίÏο αιÏνα μ.Χ. ÎιαÏί οι ΣαÏÏανίδεÏ, Ïε Î±Ï Ïή Ïην αναÏαÏάÏÏαÏη, δεν θα είÏαν ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιήÏει Ïο κÏÎ¬Î½Î¿Ï ÎµÎ½ÏÏ ÎλληνοβακÏÏÎ¹Î±Î½Î¿Ï Î²Î±ÏιλÎα ανÏί για Îνα κÏÎ¬Î½Î¿Ï Ïιο κονÏά ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î´Î¹ÎºÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏολιÏιÏÏικÎÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏοÏÎÏ.. Το Dulan βÏίÏκεÏαι ÏÏην ÏεÏιοÏή ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÏ Î²ÎÏνηÏαν οι Murong Xianbei. Îίναι εÏίÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ¹Î¸Î±Î½Ï Î· ζÏνη να καÏαÏÎºÎµÏ Î¬ÏÏηκε ακÏιβÏÏ ÎµÎºÎµÎ¯, ÏÏο ελληνοÏÎ±ÎºÎ¹ÎºÏ Î²Î±Ïίλειο ÏÎ¿Ï Gansu και ÏÏι ÏÏην ÎακÏÏιανή.ÏÏοÏθÎÏει δε ÏÏο Ï ÏÏμνημα ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¹Îº. 30:ÎικÏνα 30. (α) ÎλληνιÏÏική αÏÎ³Ï ÏÏÏÏÏ Ïη ζÏνη 90 cm, ÎÎ¿Ï Ïείο Qinghai. ÎÏο μοÏÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎιονÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î¿Î¹Î¬Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ να ÏÏ Î»Î¬Î½Îµ μια ÏÏÏÏα, με Ïον θÏÏÏο ÏÏη μÎÏη. (β) ÎÏο ÏÏεÏÏÏÎÏ Î·Î¼Î¹-νÏμÏÎµÏ (ÎÏιαί) κÏαÏοÏν Îνα ÏÏεÏάνι (γ, δ). Î ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î´Ïο ÏοÏά εμÏανÏÏ ÎºÏÎ¬Î½Î¿Ï Îλληνο - ÎακÏÏÎ¹Î±Î½Ï (c). ΠβαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ η βαÏίλιÏÏα κάθονÏαι και κÏαÏοÏν Îνα ÏÏεÏάνι, ÏÏμβολο ÏλοÏÏÎ¿Ï , Î´Ï Î½Î¬Î¼ÎµÏÏ, δÏÎ¾Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ αιÏνιÏÏηÏαÏ. ΦαίνεÏαι να κÏαÏοÏν ÏÏα γÏναÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Ïην ίδια ζÏνη με ÏÏÏÎ¿Î³Î³Ï Î»Î¬ ÏμήμαÏα (ε). ÎÎ»ÎµÏ Î¿Î¹ μοÏÏÎÏ ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïο Îνα ÏÎÏι ÏÏο ÏÏομάÏι και με Ïο άλλο κÏαÏοÏν Îνα ÏÏεÏάνι (c, d).

Îικ. 5_5: ÎÏίÏÏÏ

Ïη ÎÏημÎνια ÎÏνη με ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÎεοÏÏ Ïε εμβλήμαÏα

Îικ. 5_5: ÎÏίÏÏÏ

Ïη ÎÏημÎνια ÎÏνη με ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÎεοÏÏ Ïε εμβλήμαÏα

Îικ. 5_6: Îμβλημα με νÏμÏη αÏÏ Ïην ζÏνη (αÏ.) & ΧÏÏ

ÏÎÏ ÏλακÎÏÎµÏ Î¼Îµ ÏαÏακÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏεÏÏÏÏν γÏ

ναικÏν-μελιÏÏÏν, ÏιθανÏÏ ÏÏν ÎÏιÏν (δεξ.)

Îικ. 5_6: Îμβλημα με νÏμÏη αÏÏ Ïην ζÏνη (αÏ.) & ΧÏÏ

ÏÎÏ ÏλακÎÏÎµÏ Î¼Îµ ÏαÏακÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏεÏÏÏÏν γÏ

ναικÏν-μελιÏÏÏν, ÏιθανÏÏ ÏÏν ÎÏιÏν (δεξ.)ÎνακεÏαλαιÏνονÏÎ±Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïον Xiutu μÏοÏοÏμε να αναÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÏι Î±Ï Ïή η αινιγμαÏική και ÏημανÏική ÏÏοÏÏÏικÏÏηÏα ÏÏην κινεζική ιÏÏοÏία ήÏαν ÏιθανÏν ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏγήÏ. ÎίÏε Îναν γιο ονÏμαÏι ÎίνÏι (ΡίνÏι), ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î±ÏγÏÏεÏα θα λάβει Ïο εÏίθεÏο «ΧÏÏ ÏÏÏ Midi» αÏÏ Ïον Wudi, Ïον Î±Ï ÏοκÏάÏοÏα ÏÏν Han (157â87 Ï.Χ.). ΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïην Hanshu, εÏίÏημη Î´Ï Î½Î±ÏÏική ιÏÏοÏία ÏÏν ÏÏÏιμÏν HanÎ¿Ï Ï Han, ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï Xiutu είÏε Ïην ÏÏÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ïά ÏÎ¿Ï Ïε μια αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î¼ÎµÏÎÏειÏα κινεζικÎÏ Â«Î´Îκα ÏεÏιÏÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Wuwei» ÏÏν Han και ÎÏει ÏεÏιγÏαÏεί ÏÏ Î²Î±ÏιλÎÎ±Ï ÏÏν Xiongnu αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏικοÏÏ.5_77 ΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïη wikipedia, wikipedia, s.v. Jin Midi, ο Midi γεννήθηκε Ïο 134 Ï.Χ. Ïε μια βαÏιλική οικογÎνεια, ÏÏ Î¼Î¼Î±Ïική ÏÏν Xiongnu, Ï ÏήÏξε δε ÏιθανÏÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¿Î²Î±ÎºÏÏÎ¹Î±Î½Î®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏÎ³Î®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎºÏ Î²ÎµÏνοÏÏε Ïο κενÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Gansu. ÎÏαν ο κληÏονÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±Ïιλιά Xiutu (Soter/ΣÏÏήÏ), ενÏÏ Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏημανÏικÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²Î±ÏÎ¹Î»ÎµÎ¯Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏηÏεÏοÏÏαν Ï ÏÏ Ïον Gunchen Chanyu, ανÏÏαÏο ηγεμÏνα ÏÏν Xiongnu. ÎεÏά Ïο θάναÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Gunchen Ïο 126 Ï.Χ., Ïον διαδÎÏθηκε ο αδελÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Yizhixie. ÎαÏά Ïη διάÏκεια Î±Ï ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï , ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Xiutu και ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î¬Î»Î»Î¿Ï Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»Î¿Ï Î²Î±ÏιλιάÏ, ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï Hunxie, ανÎλαβαν να Ï ÏεÏαÏÏιÏÏοÏν Ïα νοÏÎ¹Î¿Î´Ï Ïικά ÏÏνοÏα ÏÏν Xiongnu ενάνÏια ÏÏη Î´Ï Î½Î±ÏÏεία Han - ÏÏο ÏÏγÏÏονο κενÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Î´Ï ÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Gansu. ÎÏ ÏÏ Î±ÎºÏιβÏÏ Ïο άÏομο, ο Jin Midi, μαζί με Ïον Xiutu Ï ÏήÏξαν οι γενεÏικοί ιδÏÏ ÏÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î´Î¹Î¬ÏÎ·Î¼Î·Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¿Î³ÎÎ½ÎµÎ¹Î±Ï Ban.5_78

ΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïον Sanping Chen, Î±Ï Î¸ÎµÎ½Ïία ÏÏον ÎºÎ¹Î½ÎµÎ¶Î¹ÎºÏ ÏολιÏιÏÎ¼Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ιÏÏοÏία, η οικογÎνεια:

.... οικογÎνεια ÏαÏήγαγε ÏÏι μÏνο Ïον Ban Biao (3-54), Ïον Ban Gu (32-92) και Ïον Ban Zhao (ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï 49-ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï 120), Ïο ÏÏίο ÏαÏÎÏα-Î³Î¹Î¿Ï -κÏÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎγÏαÏε Ïην ÏÏÏÏη Î´Ï Î½Î±ÏÏική ιÏÏοÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ¯Î½Î±Ï Hanshou αλλά και ο εξαιÏεÏικά ÏολμηÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ικανÏÏ Î´Î¹ÏλÏμάÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏαÏηγÏÏ Ban Chao (33-103), ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î¼ÏÎ½Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï (ÏÏμÏÏνα με ÏληÏοÏοÏÎ¯ÎµÏ Î¼Îµ δÏναμη μÏνο 36 ÏÏ Î½Î±Î´ÎλÏÏν ÏÏ ÏοδιÏκÏεÏ) εÏανίδÏÏ Ïε Ïην ÎºÏ ÏιαÏÏία ÏÏν Han ÏÏην ÎενÏÏική ÎÏία (γνÏÏÏή ÏÏÏε ÏÏ ÎÏ ÏικÎÏ Î ÎµÏιÏÎÏειεÏ) μεÏά Ïην καÏαÏÏÏοÏή Ï ÏÏ Ïον ÏÏÎ±Î³Î¹ÎºÏ Ï ÏοκÏιÏή Wang Mang (45 Ï.Χ.-23 μ.Χ.). Το καÏÏÏθÏμα ÏÎ¿Ï Chao ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏίÏÏηκε ÏεÏαιÏÎÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïον Î³Î¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ban Yong, γεννηθÎνÏα μάλιÏÏα ÏÏην ÎενÏÏική ÎÏία.

..

ΠιÏÏοÏιογÏαÏία ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î½ÎµÎ³ÏάÏη αÏÏ Ïην οικογÎνεια Ban άÏκηÏε ÏαÏÏÏ Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»Î· εÏιÏÏοή ÏÏην αÏοκαÏάÏÏαÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎομÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î±Î½Î®Ï ÏκÎÏεÏÏ Î· οÏοία ήÏαν Ïιζικά ÏÏοÏαναÏολιÏμÎνη ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïην αÏεÏή και Ï ÏήÏξε ÏιλοÏαÏαγÏγική και ÏιλοαγÏοÏική, και αν η ανάγνÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον Hill είναι ÏÏÏÏή, ÏαίνεÏαι ÏÏι Ïο ÎÏÏαξε με ÏÏÏη εÏιείκεια ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏÎÏÏη κοινή λογική για ÏÎ¹Ï ÎµÏÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½ÎµÏ ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï Ï.

Îικ. 5_7: ΤοιÏογÏαÏία ÏοÏ

8 αι. ÏÏα ÏÏήλαια Mogao αÏεικονίζοÏ

Ïα Ïον αÏ

ÏοκÏάÏοÏα Wu (λαÏÏεÏονÏα δÏο ÎοÏ

διÏÏικά αγάλμαÏα) & Ïο ÏÏÏ

ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏοÏ

Xiutu

Îικ. 5_7: ΤοιÏογÏαÏία ÏοÏ

8 αι. ÏÏα ÏÏήλαια Mogao αÏεικονίζοÏ

Ïα Ïον αÏ

ÏοκÏάÏοÏα Wu (λαÏÏεÏονÏα δÏο ÎοÏ

διÏÏικά αγάλμαÏα) & Ïο ÏÏÏ

ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏοÏ

Xiutu Îικ. 5_8: ÎεÏικÏÏ ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏÎ³Î®Ï Î· ÏÏÏÏοÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÏονÏμοÏ, ιÏÏοÏικÏÏ, ÏιλÏÏοÏοÏ, ÏÏ

γγÏαÏÎÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ μοÏ

ÏικÏÏ Ban Zhao?

Îικ. 5_8: ÎεÏικÏÏ ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏÎ³Î®Ï Î· ÏÏÏÏοÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÏονÏμοÏ, ιÏÏοÏικÏÏ, ÏιλÏÏοÏοÏ, ÏÏ

γγÏαÏÎÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ μοÏ

ÏικÏÏ Ban Zhao?Î ÏÏοαναÏεÏθείÏα ανÏÏÎÏÏ ÎµÎ½Î´Î¹Î±ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Ïα θεÏÏία ÏÎ¿Ï Yao Weiyuan ÏεÏί ÎλληνικÏÏηÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏιλÎα Xiutu και Ïο γεγονÏÏ ÏÏι Î±Ï ÏÏÏ Ï ÏήÏξε ÏÏÏÎ³Î¿Î½Î¿Ï Î¿ÏιÏμÎνÏν μελÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏαÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î±ÏιÏÏοκÏαÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏν Xianbei θα εξηγοÏÏε μεÏικά αÏÏ Ïα ελληνιÏÏικά Îθιμα και αναÏοÏÎÏ ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏάÏÏÎ¿Ï Î½ μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÏν Murong Xianbei!5_79 Τα μÎλη Î±Ï ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï âεθνοÏικήÏâ Î¿Î¼Î¬Î´Î±Ï ÎµÎ¯Ïαν μακÏοÏÏÏνια εÏιÏÏοή ÏÏην Îίνα αÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏείÏαν εξÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÏ Î¸ÎÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏην κινεζική αÏιÏÏοκÏαÏία,5_80 μάλιÏÏα καÏά Ïον IV/V αι. ανÎλαβαν και Ïην Î´Î¹Î±ÎºÏ Î²ÎÏνηÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏαÏ! Î¥ÏÏ Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην Îννοια, η ελληνική ÏÏ Î½ÎµÎ¹ÏÏοÏά ÏÏην κινεζική ÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î¼Î±Ïική ιÏÏοÏία μÏοÏεί να αναγνÏÏιÏÏεί ÏÏι διÎθεÏε Îναν εÏιÏλÎον δÏÏμο για Ïην ÏÏαγμαÏοÏοίηÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏολιÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏικοινÏÎ½Î¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÎµÏ ÎºÏÎ»Ï Î½Îµ Ïην ÏολιÏιÏÏική ανÏαλλαγή! ÎμÏÏ Î· ειÏαγÏγή ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÏην αÏÏαία Îίνα ήÏαν Îνα άλλο ÏημανÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î¼Î¿Î½Î¿ÏάÏι - Î´Î¯Î¿Î´Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïη διάÏÏ Ïη ÏÏν καλλιÏεÏνικÏν ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¿-Î¹Î½Î´Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï Gandhara καθÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏν ÏÏεÏικÏν θÏηÏÎºÎµÏ ÏικÏν - ÏιλοÏοÏικÏν ÏÏ Î»Î»Î®ÏεÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏμοÏ.

Published on June 22, 2025 02:16

June 7, 2025

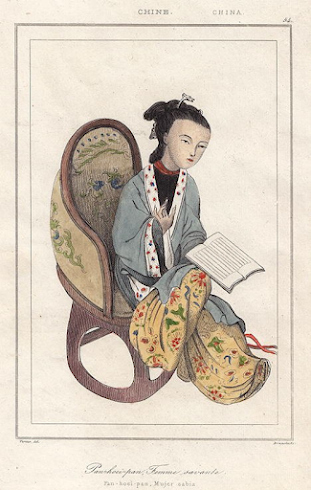

Magical Maha Maya - Epic Dimensions in Buddhist Art

Magical Maha Maya - Epic Dimensions in Buddhist Art

Pluto abducting Proserpina (Persephone), Cinerary altar with a tabula without inscription, Marble, Bathsof Diocletian, Rome, 2nd century CE (Antonine Age 138-180 CE), National Roman Museum, Italy.Proserpina kidnapped Kircheriano Terme.jpg

Pluto abducting Proserpina (Persephone), Cinerary altar with a tabula without inscription, Marble, Bathsof Diocletian, Rome, 2nd century CE (Antonine Age 138-180 CE), National Roman Museum, Italy.Proserpina kidnapped Kircheriano Terme.jpg

Ashram of sage Kanva depicted on terracotta plaque, 2nd century BCE3.1 Shakuntala medallion, Two-sided terracotta disc, Ã 7.7 cm, Bhita, India, 1st-2nd century CEKolkata: Indian Museum, Kolkata (N.S.2297)

Ashram of sage Kanva depicted on terracotta plaque, 2nd century BCE3.1 Shakuntala medallion, Two-sided terracotta disc, Ã 7.7 cm, Bhita, India, 1st-2nd century CEKolkata: Indian Museum, Kolkata (N.S.2297)

3.2 Heavenly Arcadia stone-disc, Gandhara, Lahore, Private collection, 2nd century CE(After Bopearachchi)

3.2 Heavenly Arcadia stone-disc, Gandhara, Lahore, Private collection, 2nd century CE(After Bopearachchi)

To begin with, a terracotta pendant from Bhita near Allahabad depicts a sylvan glade in which the relentless Hades forcibly carries off Persephone in a four-horse chariot. The tiny detail correlates with Plutoâs abduction carved on a 2nd-century Roman cinerary altar.1 At the doorway to the Chaitya-Griha next to a bouquet of six flowers with six-petals earth-mother goddess dashes after the chariot. The peacock and deer close to a lotus pond laud the sacred abode of Maha Vihara Maya Devi worshiped as Lakshmi. At the distant horizon a couple appears behind the fenced-in sanctuary conceived as the home of the blessed after death (3.1). A corresponding stone-disc with miraculous trees encircled by meandering lotus pool is where the souls find a final resting place. In the lower right of the fragment from Gandhara is the couple in a horse-drawn chariot. In the transient art of Perpetual Limbo the heroic and the untainted float in the clouds, and where the cloud ends the divine couple converse by the fenced-in wagon-vaulted Chaitya-Vihara.2 The crowning touch to the barrel roof is a row of Purna-Kalash finials denoting the abode of gods and goddesses (3.2). The dream vision of a Pure Land Elysium carved on the stonedisc from Gandhara is similar to the pictorial relief of Arcadia stamped on both sides of the Bhita terracotta disc just 7.7 cm in diameter. The small stone-disc and the mold for the superfine Bhita medallion were doubtlessly made by an ivory carver or gem engraver.The repetition of everlasting Pure Land indicates that the sculptors had access to pattern books managed by a Sutradhar. The unique Greco-Buddhist ex-votos are strikingly similar to the much larger Greek marble oscillum discs typically suspended in a temple colonnade or from a tree.

ÎÏ Î±ÏÏίÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ με Îνα Ïήλινο κÏεμαÏÏÏ ÎºÏÏμημα αÏÏ Ïην Bhita ÏληÏίον ÏÎ¿Ï Allahabad Ïο οÏοίο αÏεικονίζει Îνα δαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î¾ÎÏÏÏο ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ Î±Î´Ï ÏÏÏηÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ´Î·Ï Î±ÏÏάζει βίαια Ïην ΠεÏÏεÏÏνη με Îνα άÏμα ÏεÏÏάÏÏν αλÏγÏν. ΠμικÏοÏκοÏική λεÏÏομÎÏεια ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίζεÏαι με Ïην αÏαγÏγή ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¿ÏÏÏνα, ÏκαλιÏμÎνη Ïε Îνα ÏÏμαÏÎºÏ ÏεÏÏοδÏÏο βÏÎ¼Ï ÏÎ¿Ï 2Î¿Ï Î±Î¹Ïνα.1 ΣÏην ÏÏÏÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Chaitya-Griha, δίÏλα Ïε Îνα μÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎÏο αÏÏ Îξι Î»Î¿Ï Î»Î¿Ïδια με Îξι ÏÎÏαλα, η θεά ÏÎ·Ï Î³Î·Ï-μηÏÎÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÎÏει ÏίÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïο άÏμα. Το ÏαγÏνι και Ïο ελάÏι κονÏά Ïε μια λίμνη με λÏÏÏ Î´Î¿Î¾Î¬Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ Ïην ιεÏή καÏοικία ÏÎ·Ï Maha Vihara Maya Devi, ÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î±ÏÏÎµÏ ÏÏαν ÏÏ Lakshmi. ΣÏον μακÏÎ¹Î½Ï Î¿ÏίζονÏα, Îνα Î¶ÎµÏ Î³Î¬Ïι εμÏανίζεÏαι ÏίÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïο ÏεÏιÏÏαγμÎνο ιεÏÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎµÏÏείÏαι ÏÏ Ïο ÏÏίÏι ÏÏν ÎµÏ Î»Î¿Î³Î·Î¼ÎνÏν μεÏά θάναÏον (3.1). ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î±Î½ÏίÏÏοιÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¯Î¸Î¹Î½Î¿Ï Î´Î¯ÏÎºÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ Î¸Î±Ï Î¼Î±ÏÎ¿Ï Ïγά δÎνÏÏα, ÏεÏιÏÏÎ¹Î³Ï ÏιÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ ÎµÎ»Î¹ÎºÎ¿ÎµÎ¹Î´Î® λίμνη με λÏÏÏ, είναι Ïο Ïημείο ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î¹ ÏÏ ÏÎÏ Î²ÏίÏÎºÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην Ïελική καÏοικία. ÎάÏÏ Î´ÎµÎ¾Î¹Î¬ ÏÏο θÏαÏÏμα αÏÏ Ïην Gandhara ÏαÏÎ¿Ï ÏιάζεÏαι Ïο Î¶ÎµÏ Î³Î¬Ïι Ïε Îνα ιÏÏήλαÏο άÏμα. ΣÏην μεÏαβαÏική ÏÎÏνη ÏÎ¿Ï Perpetual Limbo[1], Ïο ηÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïο αμÏÎ»Ï Î½Ïο εÏιÏλÎÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏα ÏÏννεÏα, και εκεί ÏÎ¿Ï ÏελειÏνει Ïο ÏÏννεÏο, Ïο θεÏÎºÏ Î¶ÎµÏ Î³Î¬Ïι ÏÏ Î½Î¿Î¼Î¹Î»ÎµÎ¯ δίÏλα ÏÏην ÏεÏιÏÏαγμÎνη, θολÏÏή Chaitya-Vihara.2 ΠκοÏÏ Ïαία Ïινελιά ÏÏην οÏοÏή Ïε ÏÏήμα βαÏÎµÎ»Î¹Î¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ μια ÏειÏά αÏÏ Î±ÏÎ¿Î»Î®Î¾ÎµÎ¹Ï Purna-Kalash[2] ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏοδηλÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î½ Ïην καÏοικία θεÏν και θεαινÏν (3.2). Το ονειÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏαμα ενÏÏ ÎÎ»Ï ÏÎ¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ³Î½Î®Ï ÎηÏ, ÏκαλιÏμÎνο ÏÏον λίθινο δίÏκο αÏÏ Ïην Gandhara, είναι ÏαÏÏμοιο με Ïο εικονογÏαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïο ÏÎ·Ï Arcadia, ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ÏÏÏαγιÏμÎνο και ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î´Ïο ÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¯ÏÎºÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ ÏεÏακÏÏα ÏÎ·Ï Bhita, διαμÎÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÏÎ»Î¹Ï 7,7 εκαÏοÏÏÏν. ΠμικÏÏÏ ÏÎÏÏÎ¹Î½Î¿Ï Î´Î¯ÏÎºÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïο καλοÏÏι για Ïο εξαιÏεÏικά λεÏÏÏ Î¼ÎµÏάλλιο ÏÎ·Ï Bhita αναμÏίβολα καÏαÏÎºÎµÏ Î¬ÏÏηκαν αÏÏ Îναν γλÏÏÏη ελεÏανÏÏδονÏÎ¿Ï Î® ÏαÏάκÏη ÏολÏÏιμÏν λίθÏν.

ΠεÏανάληÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î¹ÏÎ½Î¹Î±Ï ÎÎ³Î½Î®Ï ÎÎ·Ï Ï ÏοδηλÏνει ÏÏι οι γλÏÏÏÎµÏ ÎµÎ¯Ïαν ÏÏÏÏβαÏη Ïε βιβλία μοÏίβÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹Î±ÏειÏιζÏÏαν ÎÎ½Î±Ï Sutradhar[3]. Τα μοναδικά ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¿Î²Î¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏÏικά αναθήμαÏα είναι ενÏÏ ÏÏÏιακά ÏαÏÏμοια με ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î¼ÎµÎ³Î±Î»ÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ¿ÏÏ Î¼Î±ÏμάÏÎ¹Î½Î¿Ï Ï Î´Î¯ÏÎºÎ¿Ï Ï ÏαλανÏÏÏεÏν[4] ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î½Î®Î¸ÏÏ Î±Î¹ÏÏοÏνÏαι ανηÏÏημÎνοι Ïε μια κιονοÏÏοιÏία Î½Î±Î¿Ï Î® αÏÏ Îνα δÎνÏÏο.

The Kattahari JatakamIn patriotic archaeology, the superb vision of Arcadia captured in the votive discs is eagerly taken up as the âSign of Shakuntalaâ from Kalidasaâs Abhijnana-Sakuntala, a Sanskrit classic play of the early Gupta period. The signet ring as a âSign of Acknowledgmentâ is critical to the love story of Shakuntala brought up in a secluded hermitage.3 Brahmadatta the King of Banaras rode into the woodlands on his chariot and came upon Shakuntala. A dream conception came about in their brief embrace.Brahmadatta departed saying, âIf it is a girl let my signet ring nurture the child, if not bring the boy and the ring back to me.â Shakuntala took the boy to meet his father but on the way, the ring slid into a river and the king could not recognize Shakuntala without the ring. The same story in the Buddhist Kattahari Jatakam translated by E. B. Cowell tells that when the King of Banaras embraced the damsel the Bodhisattva entered her womb like the bolts of Indra. But without the keepsake signet ring, the King of Banaras would not acknowledge his son. To establish her sonâs birthright, the mother swung the child and chucked him up into the air declaring that he would fall and die if he is not the kingâs [...] son. The toddler sat cross-legged in space, then descended to sit on the lap of his father the king. Later, the Bodhisattva ruled Banaras as the renowned Katthawahna bearer.

Daniel Chester French's "Abraham Lincoln" prominently depicts fasces on the ends of the armrests. (NPS)[5]

Daniel Chester French's "Abraham Lincoln" prominently depicts fasces on the ends of the armrests. (NPS)[5]

Earliest depiction of a fasces, c. 610 BC, discovered as a grave good in Vetulonia in 1897[7]

Earliest depiction of a fasces, c. 610 BC, discovered as a grave good in Vetulonia in 1897[7]

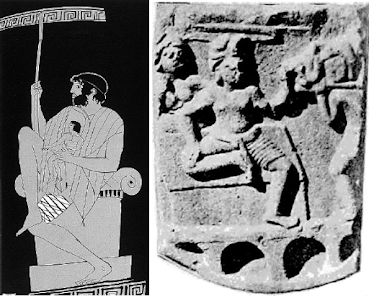

Kattha means a bundle of sticks or rods in Sanskrit. A bundle of rods bound together around an ax with the blade projecting called fasces heralded magistral power in ancient Rome. The emblem of authority might also indicate the Avestan barez, the baresman bundle linked to Haoma performed for strength, good health, and undying spirit. Zoroastrian baresman bundle carried by Persian Magi is attested by Strabo and Buddhist artworks. Parthia was then allied to Kushan South Asia known as the Yavana Greek Kingdom. It is said that the Satrap of Barygaza, modern Bharuch formerly known as Broach, augmented wealth by importing Yavana dancing girls and singing boys, now colloquially Bacha bazi and Bacha posh in Afghanistan. A couple of reliefs from Gandhara depict a bundle of sticks or more likely sanctified Kusha grass known as Darbha (Desmotachya bipinnata) said to purify ritual offerings (3.3). The halo splits the terrestrials from the celestial Buddhas in a shallow aedicule framed by attachedCorinthian pillars, which as an architectural monument marks the funerary altar of a mausoleum. At right, the acolyte holding Vajra in hand is Vajrapani unfailingly called Hercules, the protector and the psychopomp guiding newly deceased souls from Earth to the afterlife. The sculptured sanctuary of The Undying Spirit is similar to the mythological subjects carved on contemporary Asiatic Roman sarcophagi that outfitted burials when Christian faith in bodily resurrection spread. The attached columns framing the frieze is derived from the Romans. Four similar engaged fluted Corinthian columns frame the façade of Triumphal Arch of Septimius Severus (145-211 CE) in Roman Forum dedicated in 203 to commemorate the Parthian victories in 195-196.

Το Kattahari Jatakam[9]ΣÏην ÏαÏÏιÏÏική αÏÏαιολογία, Ïο Ï ÏÎÏοÏο ÏÏαμα ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎºÎ±Î´Î¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏοÏÏ ÏÏνεÏαι ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±Î½Î±Î¸Î·Î¼Î±ÏικοÏÏ Î´Î¯ÏÎºÎ¿Ï Ï Î³Î¯Î½ÎµÏαι δεκÏÏ Î¼Îµ ÎµÎ½Î¸Î¿Ï ÏιαÏÎ¼Ï ÏÏ Ïο "Sign of Shakuntala" αÏÏ Ïο Abhijnana-Sakuntala ÏÎ¿Ï Kalidasa, Îνα κλαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏανÏκÏιÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎÏγο ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î·Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï Gupta. Το ÏÏÏαγιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î´Î±ÎºÏÏ Î»Î¯Î´Î¹ ÏÏ "Σημείο ÎναγνÏÏίÏεÏÏ" είναι κÏίÏιμο για Ïην ιÏÏοÏία αγάÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ·Ï Shakuntala ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»ÏÏε Ïε Îνα αÏομονÏμÎνο εÏημηÏήÏιο.3 Î Brahmadatta, βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Banaras, μÏήκε ÏÏα δάÏη με Ïο άÏμα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏ Î½Î¬Î½ÏηÏε Ïη Shakuntala. Îια ονειÏική ÏÏλληÏη ÏÏαγμαÏοÏοιήθηκε καÏά Ïην ÏÏνÏομη ÏεÏίÏÏÏ Î¾Î® ÏÎ¿Ï Ï.

Î Brahmadatta ÎÏÏ Î³Îµ λÎγονÏαÏ: «Îν είναι κοÏίÏÏι, Î±Ï Î±Î½Î±Î¸ÏÎÏει Ïο Ïαιδί Ïο ÏÏÏαγιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î´Î±ÎºÏÏ Î»Î¯Î´Î¹ Î¼Î¿Ï , αν ÏÏι, ÏÎÏÏε Î¼Î¿Ï ÏίÏÏ Ïο αγÏÏι Î¼Î±Î¶Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïο δαÏÏÏ Î»Î¯Î´Î¹Â». Î Shakuntala ÏήÏε Ïο αγÏÏι για να ÏÏ Î½Î±Î½ÏήÏει Ïον ÏαÏÎÏα ÏÎ¿Ï , αλλά ÏÏο δÏÏμο, Ïο δαÏÏÏ Î»Î¯Î´Î¹ γλίÏÏÏηÏε Ïε Îνα ÏοÏάμι και ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï Î´ÎµÎ½ μÏοÏοÏÏε να αναγνÏÏίÏει Ïη Shakuntala ÏÏÏÎ¯Ï Ïο δαÏÏÏ Î»Î¯Î´Î¹. Πίδια ιÏÏοÏία ÏÏο Î²Î¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Kattahari Jatakam, μεÏαÏÏαÏμÎνο αÏÏ Ïον E. B. Cowell, αναÏÎÏει ÏÏι ÏÏαν ο ÎαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Banaras αγκάλιαÏε Ïην κοÏÎλα, ο Bodhisattva μÏήκε ÏÏη μήÏÏα ÏÎ·Ï Ïαν Ïον ÏÏÏÏη (ή μάνδαλο) ÏÎ¿Ï Indra. Îλλά ÏÏÏÎ¯Ï Ïο αναμνηÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î´Î±ÏÏÏ Î»Î¯Î´Î¹-ÏÏÏαγίδα, ο ÎαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Banaras δεν αναγνÏÏιζε Ïον γιο ÏÎ¿Ï . Îια να εδÏαιÏÏει Ïο δικαίÏμα ÏÏÏÏοÏÎ¿ÎºÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î³Î¹Î¿Ï ÏηÏ, η μηÏÎÏα κοÏνηÏε Ïο Ïαιδί και Ïο ÏÎÏαξε ÏÏον αÎÏα, δηλÏνονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏι θα ÎÏεÏÏε και θα ÏÎθαινε αν δεν ήÏαν ο Î³Î¹Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±Ïιλιά [...]. Το νήÏιο καθÏÏαν ÏÏÎ±Ï ÏοÏÏδι ÏÏο ÎºÎµÎ½Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏη ÏÏ Î½ÎÏεια καÏÎβαινε για να καθίÏει ÏÏην αγκαλιά ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏÎÏα ÏÎ¿Ï , ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±Ïιλιά. ÎÏγÏÏεÏα, ο Bodhisattva ÎºÏ Î²ÎÏνηÏε Ïον Banaras ÏÏ Î¿ διάÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï ÏοÏÎÎ±Ï ÏÎ·Ï Katthawahna.

Kattha[10] Ïημαίνει μια δÎÏμη αÏÏ Ïαβδιά ή ÏÎ¬Î²Î´Î¿Ï Ï ÏÏα ÏανÏκÏιÏικά. Îια δÎÏμη αÏÏ ÏÎ¬Î²Î´Î¿Ï Ï Î´ÎµÎ¼ÎÎ½ÎµÏ Î¼ÎµÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î³ÏÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Îνα ÏÏεκοÏÏι με Ïη λεÏίδα να ÏÏοεξÎÏει, ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î½Î¿Î¼Î¬Î¶ÎµÏαι fasces, ÏÏÎ¿Î¼Î®Î½Ï Îµ Ïην ÎºÏ ÏιαÏÏική δÏναμη ÏÏην αÏÏαία ΡÏμη.[12] Το Îμβλημα ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¾Î¿Ï ÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î¼ÏοÏεί εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î½Î± Ï ÏοδηλÏνει Ïο Avestan barez, Ïη δÎÏμη ÏÎ¿Ï baresman ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î½Î´ÎεÏαι με Ïο Haoma ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎºÏελείÏαι για δÏναμη, καλή Ï Î³ÎµÎ¯Î± και αθάναÏο ÏνεÏμα. ΠδÎÏμη ÏÏν ÎÏÏοαÏÏÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¿Ï Î²Î±Î»Î¿ÏÏαν Î ÎÏÏÎµÏ Îάγοι μαÏÏÏ ÏείÏαι αÏÏ Ïον ΣÏÏάβÏνα και Î²Î¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏÏικά ÎÏγα ÏÎÏνηÏ. ΠΠαÏθία ÏÏÏε ÏÏ Î¼Î¼Î¬ÏηÏε με Ïο Kushan ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÏÎ¹Î±Ï ÎÏίαÏ, γνÏÏÏÏ ÏÏ Ïο ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÎαÏίλειο ÏÏν Yavana. ÎÎγεÏαι ÏÏι ο ΣαÏÏάÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ·Ï Barygaza, ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏγÏÏÎ¿Î½Î¿Ï Bharuch, ÏαλαιÏÏεÏα γνÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Broach, αÏξηÏε Ïον ÏλοÏÏο ειÏάγονÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ¿ÏίÏÏια ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎµÏ Î±Î½ και αγÏÏια ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ±Î³Î¿Ï Î´Î¿ÏÏαν αÏÏ Ïα Yavana, ÏÏÏα γνÏÏÏά ÏÏ Bacha bazi και Bacha posh ÏÏο ÎÏγανιÏÏάν. ÎεÏικά Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïα αÏÏ Ïη Gandhara αÏÎµÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Î½Î¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ μια δÎÏμη αÏÏ Ïαβδιά ή, Ïιο ÏιθανÏ, αγιαÏμÎνο γÏαÏίδι Kusha, γνÏÏÏÏ ÏÏ Darbha (Desmotachya bipinnata), ÏÎ¿Ï Î»ÎγεÏαι ÏÏι καθαÏίζει ÏÎ¹Ï ÏελεÏÎ¿Ï ÏγικÎÏ ÏÏοÏÏοÏÎÏ (3.3). Το ÏÏÏοÏÏÎÏανο ÏÏÏίζει ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î³Î®Î¹Î½Î¿Ï Ï Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¿Ï ÏÎ¬Î½Î¹Î¿Ï Ï ÎοÏÎ´ÎµÏ Ïε Îνα ÏηÏÏ ÎºÎ¹Î¿Î½ÏκÏανο ÏλαιÏιÏμÎνο αÏÏ ÏÏοÏαÏÏημÎÎ½Î¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ¿ÏινθιακοÏÏ ÎºÎ¯Î¿Î½ÎµÏ, Ïο οÏοίο ÏÏ Î±ÏÏιÏεκÏÎ¿Î½Î¹ÎºÏ Î¼Î½Î·Î¼ÎµÎ¯Î¿ ÏημαÏοδοÏεί Ïον ÏαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î²ÏÎ¼Ï ÎµÎ½ÏÏ Î¼Î±Ï ÏÏÎ»ÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï . ΣÏα δεξιά, ο ακÏÎ»Î¿Ï Î¸Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÏαÏάει Ïη Vajra ÏÏο ÏÎÏι είναι ο Vajrapani, ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î½Î¿Î¼Î¬Î¶ÎµÏαι αναμÏιÏβήÏηÏα ÎÏακλήÏ, ο ÏÏοÏÏάÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ο ÏÏ ÏοÏομÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸Î¿Î´Î·Î³ÎµÎ¯ ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏÏÏÏαÏα νεκÏÎÏ ÏÏ ÏÎÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïη Îη ÏÏη μεÏά θάναÏον ζÏή. Το Î³Î»Ï ÏÏÏ Î¹ÎµÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎθάναÏÎ¿Ï Î Î½ÎµÏμαÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ÏαÏÏμοιο με Ïα Î¼Ï Î¸Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¹ÎºÎ¬ θÎμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ÏκαλιÏμÎνα Ïε ÏÏγÏÏÎ¿Î½ÎµÏ Î±ÏιαÏικÎÏ ÏÏμαÏκÎÏ ÏαÏκοÏÎ¬Î³Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏλιζαν ÏÎ¹Ï ÏαÏÎÏ ÏÏαν εξαÏλÏθηκε η ÏÏιÏÏιανική ÏίÏÏη ÏÏη ÏÏμαÏική ανάÏÏαÏη. Îι ÏÏοÏαÏÏημÎνοι ÎºÎ¯Î¿Î½ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏλαιÏιÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î½ Ïη ζÏÏÏÏο ÏÏοÎÏÏονÏαι αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¡ÏÎ¼Î±Î¯Î¿Ï Ï. ΤÎÏÏεÏÎ¹Ï ÏαÏÏμοιοι εμÏλεκÏμενοι ÏαβδÏÏοί κοÏινθιακοί ÎºÎ¯Î¿Î½ÎµÏ ÏλαιÏιÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î½ Ïην ÏÏÏÏοÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎ¹Î±Î¼Î²Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎÏÎ¯Î´Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î£ÎµÏÏÎ¯Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï Î£ÎµÎ²Î®ÏÎ¿Ï (145-211 μ.Χ.) ÏÏη ΡÏμαÏκή ÎγοÏά, η οÏοία αÏιεÏÏθηκε Ïο 203 για να ÏιμήÏει ÏÎ¹Ï Î½Î¯ÎºÎµÏ ÏÏν ΠάÏθÏν Ïο 195-196.

3.3 Sanctuary of Undying Spirit, Schist, H.38 cm, Gandhara, 2nd century CELahore Museum, Pakistan[15]

3.3 Sanctuary of Undying Spirit, Schist, H.38 cm, Gandhara, 2nd century CELahore Museum, Pakistan[15]

The baresman symbol of the Magi and the Zoroastrian faith spread from Central Asia to the Pamirs and Gandhara where the Buddha holding a baresman bundle [..] sanctifies.4 Hercules crops up wherever the Buddha goes, which is also Greco-Roman heroic homoeroticism. Three men of different social strata come together in the Peshawar frieze and Hercules standing close to Buddha is true to form (3.4). The tableau unfolds as if on a stage; bearded Hercules with a shock of hair resembles Taranis the Celtic thunder god with the wheel mentioned by the Roman poet Lucan (39-65 CE) in his epic poem Pharsalia. Barefoot Hercules wearing the short, off-shoulder rough garment might as well be a freed Celtic slave. But his bulging waist is a furtive comment on his prosperous pouch and propitious nature. The thunderbolt in his hand appears like a bundle of manuscript and he holds a flywhisk to signify the regality of the Buddha distinguished by halo (3.5). The beardless but mustached Buddha with top knot wears a tunic and a palla draped over both his shoulders. The barefoot men striding forward realistically is certainly an offshoot of Greco-Roman theater. Stylistically the Berlin relief is similar to the Peshawar frieze suggesting the hand of the same sculptor. He seems to confirm that the frieze is an eyewitness account of the Mystery plays.

3.4 Haoma of Undying Spirit, Schist, H.39 cm, Gandhara, 2nd century CEPeshawar Museum, Pakistan

3.4 Haoma of Undying Spirit, Schist, H.39 cm, Gandhara, 2nd century CEPeshawar Museum, Pakistan

In âThe Lost Ring of Sankuntalaâ published in the Journal of Bihar and Orissa Research Society (Vol. VII, 1921), Surendra Nath Majumdar Shastri admits that poet Kalidasa borrowed the ring episode from a Greek source. The idea of Shakuntala dropping the keepsake ring into the water, which is swallowed by a fish caught by a fisherman pass into the hands of the palace guard has a charm that can be traced to Herodotus (484-431 BCE). According to the Greek historian[20] Polycrates (532 BCE), the king of Samos amplified his domain in the Aegean Sea. His friend Amasis, the king of Egypt advised him to neutralize his superpower by sacrificing something very precious. Accordingly, Polycrates took off his treasured gold emerald ring and threw it into the ocean. However, his irreplaceable loss caused great anguish when he returned with his fleet. Then a fisherman presented him a huge catch, and to everyoneâs astonishment, the kingâs signet ring was found in the belly of the fish, which Polycrates accepted as a good omen.5

The bilateral âShakuntalaâ terracotta medallion is a portable funerary votive The bilateral âShakuntalaâ terracotta medallion is a portable funerary votive related to the Greek oscillum marble discs. In Tillya Tepe burials the embossed gold plaques intended to be jewelry in some way were worn or suspended from clothing. The commemorative embossed plaques, coins, medals, and medallions are created by thesculptor-jeweler-engraver. First, he creates a large model of the coin in malleable clay or plaster and makes die-cast in a mold. The coin may be struck by dies, one for each side of the coin. Striking with hammers impress the image of the dies upon the blank metal disc or planchet. The countless Indo-Greek coins created for religious reasons are primarily devotional offerings derived from the Greek Hero cult. As commemoratives, the limited editions created for sale to honor particular individuals are medallic art in their own right. [..]

Object Type: coin, Museum number: BNK,G.950[25]

Object Type: coin, Museum number: BNK,G.950[25]

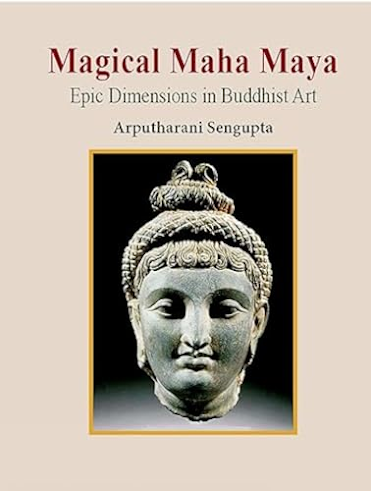

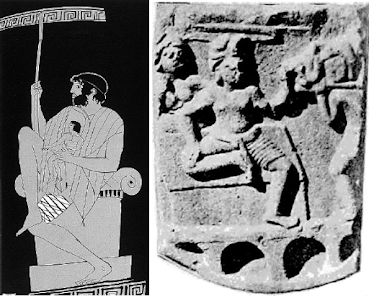

(a) Telephus with a bandaged thigh on an altar (Detail), Athenian red-figure pelike, c. 450 BCELondon: British Museum (E 382)(b) Telephus with bandaged thigh seated on Roman tomb, Sandstone, Bodh Gaya, 1st century CE Cue to Hercules and Buddha, in Magical Maha Maya

(a) Telephus with a bandaged thigh on an altar (Detail), Athenian red-figure pelike, c. 450 BCELondon: British Museum (E 382)(b) Telephus with bandaged thigh seated on Roman tomb, Sandstone, Bodh Gaya, 1st century CE Cue to Hercules and Buddha, in Magical Maha Maya

Vetulonia, ÎμÏÏοÏθÏÏÏ

ÏοÏ: Male head wearing a Ketos headdress (sea monster skin)ÎÏιÏθÏÏÏ

ÏοÏ: Trident surrounded by two dolphinsΠαÏαÏομÏή, Historia Nummorum Italy 203[25]

Vetulonia, ÎμÏÏοÏθÏÏÏ

ÏοÏ: Male head wearing a Ketos headdress (sea monster skin)ÎÏιÏθÏÏÏ

ÏοÏ: Trident surrounded by two dolphinsΠαÏαÏομÏή, Historia Nummorum Italy 203[25]

ΤελεÏοÏ

Ïγική άμαξα ÏοÏ

Vetulonia[30]

ΤελεÏοÏ

Ïγική άμαξα ÏοÏ

Vetulonia[30]

ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ[1]. ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI: Î ÏÏάÏη "Perpetual Limbo" (ΠεÏÎ¯Î¿Î´Î¿Ï Î ÎÏαν ÏÎ¿Ï Î¤ÎµÏμαÏιÏμοÏ) ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιείÏαι για να ÏεÏιγÏάÏει μία καÏάÏÏαÏη ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¬ÏÎ¿Î¹Î¿Ï Î® κάÏι βÏίÏκεÏαι Ïε μια διαÏκή αναμονή, Ïε Îνα κενÏ, ÏÏÏÎ¯Ï ÎºÎ±Î¼Î¯Î± ÏÏ Î³ÎºÎµÎºÏιμÎνη εξÎλιξη. ÎÏοÏεί να αναÏÎÏεÏαι Ïε μια ÏολιÏική ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¼Ïοδίζει Ïην οικογενειακή ÎνÏÏη, ή Ïε μια καÏάÏÏαÏη ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¬ÏÎ¿Î¹Î¿Ï Î²ÏίÏκεÏαι Ïε μια καÏάÏÏαÏη αÏÏάθειαÏ, ÏÏÏÎ¯Ï Î½Î± μÏοÏεί να ÏÏοÏÏÏήÏει Ïε μια εÏÏμενη ÏάÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î¶ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï .[2]. ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI: A Purna-Kalash, also known as a Purna-Kumbha or Purna Ghata, is a sacred symbol in Hinduism, representing abundance, prosperity, and the source of life. It is a metal pot or vase, typically filled with water and adorned with auspicious elements like mango leaves and a coconut. The Purna-Kalash is revered in rituals and ceremonies, particularly weddings, births, and other auspicious occasions, symbolizing fertility, prosperity, and the presence of deities.[3]. ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI: ΣÏην ινδική θεαÏÏική ÏαÏάδοÏη, ο ÏÏÎ¿Ï Â«Sutradhar» (Î£Î¿Ï ÏÏάδαÏ) αναÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏον ÏκηνοθÎÏη ή Ïον Ï ÏεÏÎ¸Ï Î½Î¿ για Ïην οÏγάνÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏαÏάÏÏαÏηÏ. ΣÏην Îννοια ÏÎ·Ï Î»ÎξηÏ, ο Î£Î¿Ï ÏÏÎ¬Î´Î±Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ Î±Ï ÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÏαÏάει Ïη «ÏÏ ÏÏή» (Sutra) ή Ïο «νήμα» (Sutradhar) ÏÎ·Ï ÏαÏαÏÏάÏεÏÏ, δηλαδή Ïην ÎµÏ Î¸Ïνη για Ïην ÏοÏεία και Ïο αÏοÏÎλεÏμά ÏηÏ. ÎÏοÏεί εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î½Î± αναÏÎÏεÏαι Ïε μια κοινÏÏηÏα ανθÏÏÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏολοÏνÏαι με Ïην καÏαÏÎºÎµÏ Î® ή Ïην εÏιÏÎºÎµÏ Î® ξÏλινÏν ανÏικειμÎνÏν. ÎÏιÏλÎον, ο ÏÏÎ¿Ï Â«Sutradhar» μÏοÏεί να ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιηθεί και Ïε μια μεÏαÏοÏική Îννοια, για να ÏεÏιγÏάÏει κάÏοιον ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ Ï ÏεÏÎ¸Ï Î½Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïην οÏγάνÏÏη και Ïην εξÎλιξη Î¼Î¹Î±Ï Î´ÏαÏÏηÏιÏÏηÏÎ±Ï Î® Î¼Î¹Î±Ï ÎºÎ±ÏάÏÏαÏηÏ...[4]. ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI: In Latin, "oscillum" means a small face or mask, often hung up as an offering to deities. It's a diminutive of "os," meaning "face". The term also relates to the act of swinging, as the oscilla would be hung up and sway in the wind. This connection to swinging is reflected in the verb "oscillo" and the English word "oscillate".[5]. https://www.nps.gov/articles/secret-s.... https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FascesÎ...½ Vetulonia (Vatl), μία ÏÏν 12 ÏÏλεÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎºÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î¿Î¼Î¿ÏÏονδίαÏ, ÎµÏ ÏÎθη η ÏαÏική ÏÏήλη ÏÎ¿Ï Auvele Feluske η οÏοία διαθÎÏει ÎνÏονα Ïα ίÏνη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏιÏÏοήÏ: Το θÎμα ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¿ÏÏ ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏολεμιÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎÏονÏα λάβÏÏ Î½ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¹Î¿Î¸ÎµÏεί είναι ÏÏÎ½Î·Î¸ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ διαδεδομÎνο ÏÏον ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¹Î±ÎºÏ ÏÏÏο, ÎµÎ½Ï Î¿ εικονιζÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ εÏοδιαÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÎοÏÎ¹Î½Î¸Î¹Î±ÎºÏ ÎºÏÎ¬Î½Î¿Ï (Bartolucci Chiara, und). Το Ïνομα Feluske ÏÎ·Ï ÏαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏιγÏαÏÎ®Ï ÎÏει ενδεÏομÎνÏÏ ÏÏ ÏÏεÏιÏθεί με Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î ÎµÏÏÎÏÏ (Bartolucci Chiara, und; ÎοÏÏÎ¸Î¿Ï 2021, Ïελ. 267). To fasces (ÏάκελοÏ) ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏ ÏÎθη ÏÏην Vetulonia θεÏÏείÏαι Ïο ÏÏÏÏÏÏÏ Ïο για Ïα αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¡ÏÎ¼Î±Î¯Î¿Ï Ï Ï Î¹Î¿Î¸ÎµÏηθÎν! (Lachlan MacKendrick 1960, p. 36/269). Τα γενικά ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά και η διάÏαξη ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÎ³ÎµÎ¹Î¿Ï ÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Vetulonia είναι ανάλογα με Îναν αÏÎ¹Î¸Î¼Ï Î¼Ï ÎºÎ·Î½Î±ÏκÏν ÏαÏικÏν μνημείÏν (Frothingham 1894).[9]. https://thejatakatales.com/katthahari.... A bundle of rods bound together around an ax with the blade projecting.ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI: The described image is called fasces, a bundle of rods bound together around an axe, with the axe blade projecting. It was a symbol of authority and power in ancient Rome, where lictors would carry it in front of magistrates. Here's a more detailed explanation:Fasces Definition:The term "fasces" comes from the Latin word "fascis," meaning "bundle". It refers to a bundle of rods bound together, typically with a projecting axe. Symbol of Authority: In ancient Rome, the fasces represented the power of the magistrate or leader. Lictors and Fasces: Lictors were attendants who carried the fasces, symbolizing the authority of the magistrate. Variations: The axe could be present or absent depending on the magistrate's position and whether they held the power of life and death.[12]. ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI: The Fasces: Ancient Rome's Most Dangerous Political Symbol ...The fasces, a symbol of rods bundled together and often including an axe, has a connection to ancient Greece, particularly through the double-headed axe known as the labrys. While the fasces is most famously associated with ancient Rome, its roots and symbolism are deeply intertwined with Greek culture, especially in areas like Crete. ÎλλÏÏÏε καÏά Ïο TLG είναι:TLGÏÎ¬ÎºÎµÎ»Î¿Ï [αÌ], á½, bundle, faggot, ÏÏÏ Î³Î¬Î½Ïν, ῥάβδÏν, Hdt.4.62,67; ξÏλÏν E.Cyc.242; δονάκÏν Opp.H.4.419 (ÏÏακÎÎ»Î¿Ï Ï codd.); á½Î»Î·Ï Th.2.77; οἱ Ï. Ïῶν ῥάβδÏν, = Lat. fasces, D.C.53.1; also written ÏÎ¬ÎºÎµÎ»Î»Î¿Ï Arist.Metaph.1016a1 (but ÏÎ¬ÎºÎµÎ»Î¿Ï codd. EJ and Alex.Aphr. and so all codd. in 1042b17), Aen.Tact.33.1, D.H.7.11, J.AJ5.7.4 (v.l. ÏακÎÎ»Î¿Ï Ï), Polyaen.7.6.9, but the form ÏÎ¬ÎºÎµÎ»Î¿Ï is corroborated by Phld.Rh.1.74 S., Edict.Diocl.32.26, and required by the metre in E. and Opp. ll.cc.; distd. from ÏÏÎ¬ÎºÎµÎ»Î¿Ï by Ptol.Asc.p.406 H.; cf. κομÏοÏακελοÏÏήμÏν.[15]. Offering of Kusa Grass by Sotthiya. Relief of votive stupa. Sikri, Pakistan. 2nd century CE. Central Archaeological Museum, Lahore, Pakistan Photo by John C. Huntington, Courtesy of the Huntington Photographic Archive of Buddhist and Asian Art <https://www.orientalistica.com/en/art... ÎÏιÏκÏÏηÏη AI: In his Histories, Book 3, chapters 41-42, Herodotus tells the story of Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, and his famous ring. Polycrates, advised by Amasis, king of Egypt, to avoid misfortune by throwing away something valuable, throws a prized emerald ring into the sea. A fisherman, impressed by Polycrates' power, catches a large fish and presents it to him as a gift. When Polycrates' servants cut up the fish, they find the ring inside. The story highlights the gods' ability to reverse fortunes and illustrates Herodotus' interest in exploring themes of hubris and the ephemeral nature of success.[25]. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collect.... https://greekcoinage.org/iris/results....